60 9.1 Explaining the Diversity of Life

Charles Darwin and Natural Selection

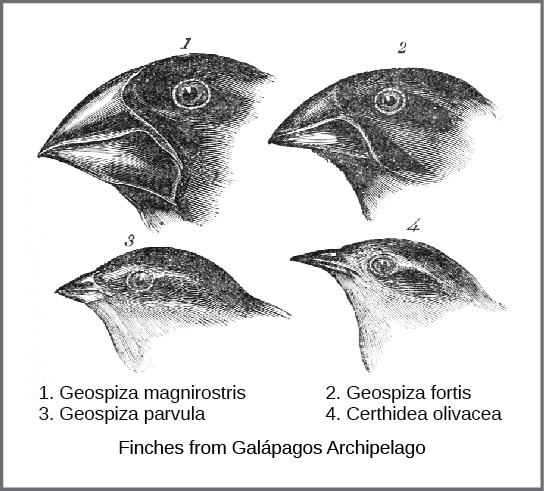

The actual mechanism for evolution was independently conceived of and described by two naturalists, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace, in the mid-nineteenth century. Importantly, each spent time exploring the natural world on expeditions to the tropics. From 1831 to 1836, Darwin traveled around the world on H.M.S. Beagle, visiting South America, Australia, and the southern tip of Africa. Wallace traveled to Brazil to collect insects in the Amazon rainforest from 1848 to 1852 and to the Malay Archipelago from 1854 to 1862. Darwin’s journey, like Wallace’s later journeys in the Malay Archipelago, included stops at several island chains, the last being the Galápagos Islands (west of Ecuador). On these islands, Darwin observed species of organisms on different islands that were clearly similar, yet had distinct differences. For example, the ground finches inhabiting the Galápagos Islands comprised several species that each had a unique beak shape (Figure 9.1.1)

). He observed both that these finches closely resembled another finch species on the mainland of South America and that the group of species in the Galápagos formed a graded series of beak sizes and shapes, with very small differences between the most similar. Darwin imagined that the island species might be all species modified from one original mainland species. In 1860, he wrote, “Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.”1

Wallace and Darwin both observed similar patterns in other organisms and independently conceived a mechanism to explain how and why such changes could take place. Darwin called this mechanism natural selection. Natural selection, Darwin argued, was an inevitable outcome of three principles that operated in nature. First, the characteristics of organisms are inherited, or passed from parent to offspring. Second, more offspring are produced than are able to survive; in other words, resources for survival and reproduction are limited. The capacity for reproduction in all organisms outstrips the availability of resources to support their numbers. Thus, there is a competition for those resources in each generation. Both Darwin and Wallace’s understanding of this principle came from reading an essay by the economist Thomas Malthus, who discussed this principle in relation to human populations. Third, offspring vary among each other in regard to their characteristics and those variations are inherited. Out of these three principles, Darwin and Wallace reasoned that offspring with inherited characteristics that allow them to best compete for limited resources will survive and have more offspring than those individuals with variations that are less able to compete. Because characteristics are inherited, these traits will be better represented in the next generation. This will lead to change in populations over generations in a process that Darwin called “descent with modification.”

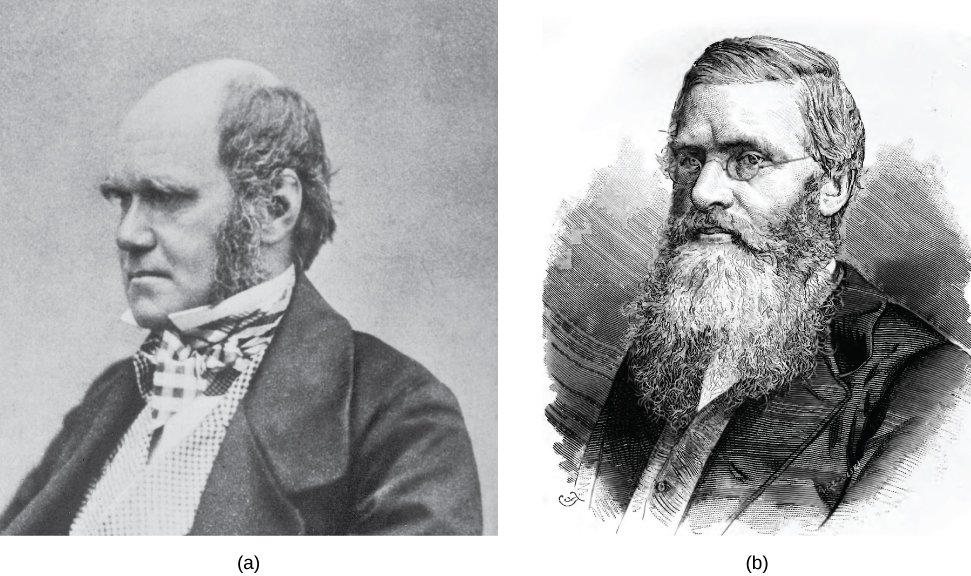

Papers by Darwin and Wallace (Figure 9.1.2) presenting the idea of natural selection were read together in 1858 before the Linnaean Society in London. The following year Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, was published, which outlined in considerable detail his arguments for evolution by natural selection.

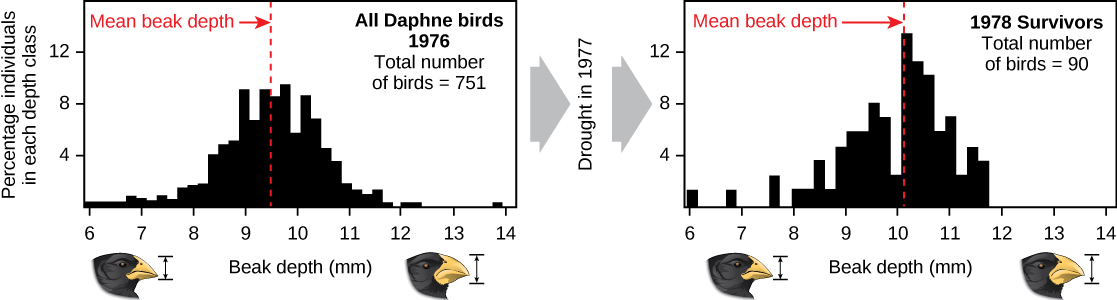

Demonstrations of evolution by natural selection can be time consuming. One of the best demonstrations has been in the very birds that helped to inspire the theory, the Galápagos finches. Peter and Rosemary Grant and their colleagues have studied Galápagos finch populations every year since 1976 and have provided important demonstrations of the operation of natural selection. The Grants found changes from one generation to the next in the beak shapes of the medium ground finches on the Galápagos island of Daphne Major. The medium ground finch feeds on seeds. The birds have inherited variation in the bill shape with some individuals having wide, deep bills and others having thinner bills. Large-billed birds feed more efficiently on large, hard seeds, whereas smaller billed birds feed more efficiently on small, soft seeds. During 1977, a drought period altered vegetation on the island. After this period, the number of seeds declined dramatically: the decline in small, soft seeds was greater than the decline in large, hard seeds. The large-billed birds were able to survive better than the small-billed birds the following year. The year following the drought when the Grants measured beak sizes in the much-reduced population, they found that the average bill size was larger (Figure 9.1.3). This was clear evidence for natural selection (differences in survival) of bill size caused by the availability of seeds. The Grants had studied the inheritance of bill sizes and knew that the surviving large-billed birds would tend to produce offspring with larger bills, so the selection would lead to evolution of bill size. Subsequent studies by the Grants have demonstrated selection on and evolution of bill size in this species in response to changing conditions on the island. The evolution has occurred both to larger bills, as in this case, and to smaller bills when large seeds became rare.

Variation and Adaptation

Natural selection can only take place if there is variation, or differences, among individuals in a population. Importantly, these differences must have some genetic basis; otherwise, selection will not lead to change in the next generation. This is critical because variation among individuals can be caused by non-genetic reasons, such as an individual being taller because of better nutrition rather than different genes.

Genetic diversity in a population comes from two main sources: mutation and sexual reproduction. Mutation, a change in DNA, is the ultimate source of new alleles or new genetic variation in any population. An individual that has a mutated gene might have a different trait than other individuals in the population. However, this is not always the case. A mutation can have one of three outcomes on the organisms’ appearance (or phenotype):

- A mutation may affect the phenotype of the organism in a way that gives it reduced fitness—lower likelihood of survival, resulting in fewer offspring.

- A mutation may produce a phenotype with a beneficial effect on fitness.

- Many mutations, called neutral mutations, will have no effect on fitness.

Mutations may also have a whole range of effect sizes on the fitness of the organism that expresses them in their phenotype, from a small effect to a great effect. Sexual reproduction and crossing over in meiosis also lead to genetic diversity: when two parents reproduce, unique combinations of alleles assemble to produce unique genotypes and, thus, phenotypes in each of the offspring.

A heritable trait that aids the survival and reproduction of an organism in its present environment is called an adaptation. An adaptation is a “match” of the organism to the environment. Adaptation to an environment comes about when a change in the range of genetic variation occurs over time that increases or maintains the match of the population with its environment. The variations in finch beaks shifted from generation to generation providing adaptation to food availability.

Whether or not a trait is favorable depends on the environment at the time. The same traits do not always have the same relative benefit or disadvantage because environmental conditions can change. For example, finches with large bills were benefited in one climate, while small bills were a disadvantage; in a different climate, the relationship reversed.

Patterns of Evolution

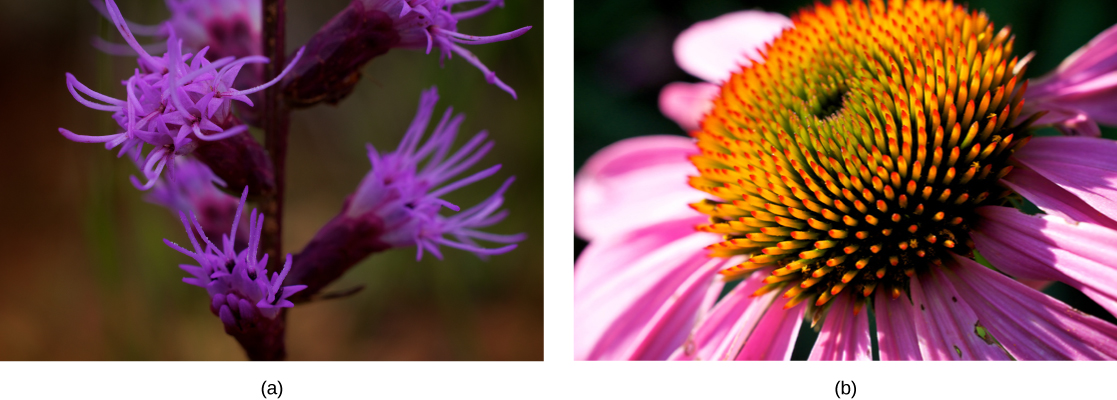

The evolution of species has resulted in enormous variation in form and function. When two species evolve in different directions from a common point, it is called divergent evolution. Such divergent evolution can be seen in the forms of the reproductive organs of flowering plants, which share the same basic anatomies; however, they can look very different as a result of selection in different physical environments, and adaptation to different kinds of pollinators (Figure 9.1.4).

In other cases, similar phenotypes evolve independently in distantly related species. For example, flight has evolved in both bats and insects, and they both have structures we refer to as wings, which are adaptations to flight. The wings of bats and insects, however, evolved from very different original structures. When similar structures arise through evolution independently in different species it is called convergent evolution. The wings of bats and insects are called analogous structures; they are similar in function and appearance, but do not share an origin in a common ancestor. Instead they evolved independently in the two lineages. The wings of a hummingbird and an ostrich are homologous structures, meaning they share similarities (despite their differences resulting from evolutionary divergence). The wings of hummingbirds and ostriches did not evolve independently in the hummingbird lineage and the ostrich lineage—they descended from a common ancestor with wings.

Footnotes

- 1 Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N, 2nd. ed. (London: John Murray, 1860), http://www.archive.org/details/journalofresea00darw.

- 2 Sahar S. Hanania, Dhia S. Hassawi, and Nidal M. Irshaid, “Allele Frequency and Molecular Genotypes of ABO Blood Group System in a Jordanian Population,” Journal of Medical Sciences 7 (2007): 51-58, doi:10.3923/jms.2007.51.58

By Keddy (University of California, Davis), is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts. Download this book for free at https://geo.libretexts.org/Courses/Diablo_Valley_College/OCEAN-101%3A_Fundamentals_of_Oceanography_(Keddy)