42 6.2 Winds and the Coriolis Effect

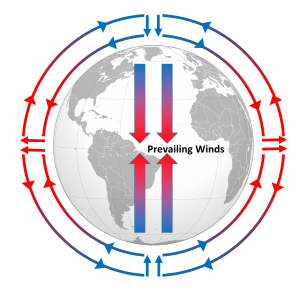

Differential heating of the Earth’s surface results in equatorial regions receiving more heat than the poles (section 6.1). As air is warmed at the equator it becomes less dense and rises, while at the poles the cold air is denser and sinks. If the Earth was non-rotating, the warm air rising at the equator would reach the upper atmosphere and begin moving horizontally towards the poles. As the air reached the poles it would cool and sink, and would move over the surface of Earth back towards the equator. This would result in one large atmospheric convection cell in each hemisphere (Figure 6.2.1), with air rising at the equator and sinking at the poles, and the movement of air over the Earth’s surface creating the winds. On this non-rotating Earth, the prevailing winds would thus blow from the poles towards the equator in both hemispheres (Figure 6.2.1).

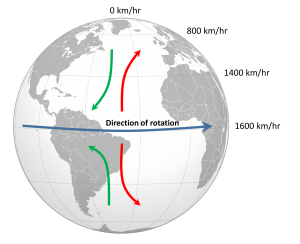

The non-rotating situation in Figure 6.2.1 is of course only hypothetical, and in reality the Earth’s rotation makes this atmospheric circulation a bit more complex. The paths of the winds on a rotating Earth are deflected by the Coriolis Effect. The Coriolis Effect is a result of the fact that different latitudes on Earth rotate at different speeds. This is because every point on Earth must make a complete rotation in 24 hours, but some points must travel farther, and therefore faster, to complete the rotation in the same amount of time. In 24 hours a point on the equator must complete a rotation distance equal to the circumference of the Earth, which is about 40,000 km. A point right on the poles covers no distance in that time; it just turns in a circle. So the speed of rotation at the equator is about 1600 km/hr, while at the poles the speed is 0 km/hr. Latitudes in between rotate at intermediate speeds; approximately 1400 km/hr at 30o and 800 km/hr at 60o. As objects move over the surface of the Earth they encounter regions of varying speed, which causes their path to be deflected by the Coriolis Effect.

To explain the Coriolis Effect, imagine a cannon positioned at the equator and facing north. Even though the cannon appears stationary to someone on Earth, it is in fact moving east at about 1600 km/hr due to Earth’s rotation. When the cannon fires the projectile travels north towards its target; but it also continues to move to the east at 1600 km/hr, the speed it had while it was still in the cannon. As the shell moves over higher latitudes, its momentum carries it eastward faster than the speed at which the ground beneath it is rotating. For example, by 30o latitude the shell is moving east at 1600 km/hr while the ground is moving east at only 1400 km/hr. Therefore, the shell gets “ahead” of its target, and will land to the east of its intended destination. From the point of view of the cannon, the path of the projectile appears to have been deflected to the right (red arrow, Figure 6.2.2). Similarly, a cannon located at 60o and facing the equator will be moving east at 800 km/hr. When its shell is fired towards the equator, the shell will be moving east at 800 km/hr, but as it approaches the equator it will be moving over land that is traveling east faster than the projectile. So the projectile gets “behind” its target, and will land to the west of its destination. But from the point of view of the cannon facing the equator, the path of the shell still appears to have been deflected to the right (green arrow, Figure 6.2.2). Therefore, in the Northern Hemisphere, the apparent Coriolis deflection will always be to the right.

In the Southern Hemisphere the situation is reversed (Figure 6.2.2). Objects moving towards the equator from the south pole are moving from low speed to high speed, so are left behind and their path is deflected to the left. Movement from the equator towards the south pole also leads to deflection to the left. In the Southern Hemisphere, the Coriolis deflection is always to the left from the point of origin.

The magnitude of the Coriolis deflection is related to the difference in rotation speed between the start and end points. Between the poles and 60o latitude, the difference in rotation speed is 800 km/hr. Between the equator and 30o latitude, the difference is only 200 km/hr (Figure 6.2.2). Therefore the strength of the Coriolis Effect is stronger near the poles, and weaker at the equator.

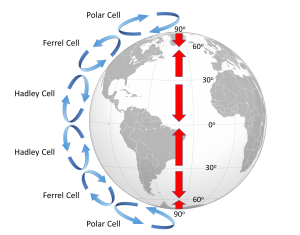

Because of the rotation of the Earth and the Coriolis Effect, rather than a single atmospheric convection cell in each hemisphere, there are three major cells per hemisphere. Warm air rising at the equator cools as it moves through the upper atmosphere, and it descends at around 30o latitude. The convection cells created by rising air at the equator and sinking air at 30o are referred to as Hadley Cells, of which there is one in each hemisphere. The cold air that descends at the poles moves over the Earth’s surface towards the equator, and by about 60o latitude it begins to rise, creating a Polar Cell between 60o and 90o. Between 30o and 60o lie the Ferrel Cells, composed of sinking air at 30o and rising air at 60o (Figure 6.2.3). With three convection cells in each hemisphere that rotate in alternate directions, the surface winds no longer always blow from the poles towards the equator as in the non-rotating Earth in Figure 6.2.1. Instead, surface winds in both hemispheres blow towards the equator between 90o and 60o latitude, and between 0o and 30o latitude. Between 30o and 60o latitude, the surface winds blow towards the poles (Figure 6.2.3).

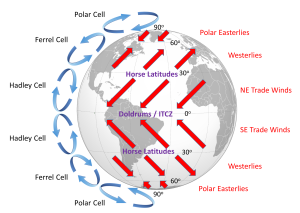

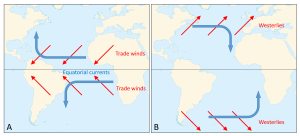

The surface winds created by the atmospheric convection cells are also influenced by the Coriolis Effect as they change latitudes. The Coriolis Effect deflects the path of the winds to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. Adding this deflection leads to the pattern of prevailing winds illustrated in Figure 6.2.4. Between the equator and 30o latitude are the trade winds; the northeast trade winds in the Northern Hemisphere and the southeast trade winds in the Southern Hemisphere (note that winds are named based on the direction from which they originate, not where they are going). The westerlies are the dominant winds between 30o and 60o in both hemispheres, and the polar easterlies are found between 60o and the poles.

In between these wind bands lie regions of high and low pressure. High pressure zones occur where air is descending, while low pressure zones indicate rising air. Along the equator the rising air creates a low pressure region called the doldrums, or the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)(convergence zone because this is where the trade winds converge). At 30o latitude there are high pressure zones of descending air known as the horse latitudes, or the subtropical highs. Finally, at 60o lies another low pressure region called the polar front. It should be noted that these high and low pressure zones are not fixed in place; their latitude fluctuates depending on the season, and these fluctuations have important implications for regional climates.

Doldrums? Horse latitudes? Trade winds?

These may seem like some odd names for these atmospheric phenomena, but many of them can be traced back to maritime traditions and lore.

The doldrums refer to regions of low pressure around the equator. In these areas, air is rising rather than moving horizontally, so these regions commonly encounter very light winds. The lack of wind could leave sailing ships becalmed for days or weeks at a time, which was not good for the morale of the ship’s crew.

Like the doldrums the horse latitudes are also areas with light winds, this time due to descending air, which could leave ships becalmed. One explanation for the term “horse latitudes” is that when these ships became stranded they ran the risk of running out of food or water. To conserve these resources, sailors would throw their dead or dying horses overboard, hence the “horse latitudes.” Another explanation is that many sailors received part of their pay before a voyage, and often spent it before departing. This meant that they would spend the first part of the voyage working without pay and in debt, a period called the “dead horse” time, which might last for a few months. When they started earning their pay once again, they had a “dead horse” ceremony and threw a pretend horse overboard. The timing of this ceremony often coincided with reaching the horse latitudes, leading to the association of the ceremony with the location. A third explanation is that a ship was referred to as “horsed” when winds were weak and the ship instead had to rely on ocean currents to move them. This could be a common occurrence in the high pressure zones around 30o latitude, so they were referred to as the horse latitudes.

The term trade winds may have originally derived from the terms for “track” or “path”, but the term may have become more common during European exploration and commercialization of the New World. Mariners sailing from Europe to the New World could sail south until they reached the trade winds, which would then propel their ships across the Atlantic to the Caribbean. To return to Europe, ships could sail to the northeast until they entered the westerlies, which would then steer them back to Europe.

If one thing has been constant about Earth’s climate over geological time, it is its constant change. In the geological record, we can see this in the evidence of glaciations in the distant past, and we can also detect periods of extreme warmth by looking at the isotope composition of seafloor sediments. Not only has the climate changed frequently, the temperature fluctuations have been very significant. Today’s mean global temperature is about 15°C. However, during its coldest periods, the global mean was as cold as -50°C, while at various times during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic and during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum, it was close to 30°C.

There are two parts to climate change, the first one is known as climate forcing, which is when conditions change to give the climate a little nudge in one direction or the other. The second part of climate change, and the one that typically does most of the work, is what we call a feedback. When a climate forcing changes the climate a little, a whole series of environmental changes take place, many of which either exaggerate the initial change (positive feedback), or suppress the change (negative feedback).

An example of a climate forcing mechanism is the increase in the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere that results from our use of fossil fuels. CO2 traps heat in the atmosphere and leads to climate warming. Warming changes vegetation patterns; contributes to the melting of snow, ice, and permafrost; causes sea level to rise; reduces the solubility of CO2 in sea water; and has a number of other minor effects. Most of these changes contribute to more warming. Melting of permafrost, for example, is a strong positive feedback because frozen soil contains trapped organic matter that is converted to CO2 and methane (CH4) when the soil thaws. Both these gases accumulate in the atmosphere and add to the warming effect. On the other hand, if warming causes more vegetation growth, that vegetation should absorb CO2, thus reducing the warming effect, which would be a negative feedback. Under our current conditions — a planet that still has lots of glacial ice and permafrost — most of the feedbacks that result from a warming climate are positive feedbacks and so the climate changes that we cause get naturally amplified by natural processes.

Natural Climate Forcing

Natural climate forcing has been going on throughout geological time. A wide range of processes has been operating at widely different time scales, from a few years to billions of years. The longest-term natural forcing variation is related to the evolution of the Sun. Like most other stars of a similar mass, our Sun is evolving. For the past 4.6 billion years, its rate of nuclear fusion has been increasing, and it is now emitting about 40% more energy (as light) than it did at the beginning of geological time. A difference of 40% is big, so it’s a little surprising that the temperature on Earth has remained at a reasonable and habitable temperature for all of this time. The mechanism for that relative climate stability has been the evolution of our atmosphere from one that was dominated by CO2, and also had significant levels of CH4 — both greenhouse gasses — to one with only a few hundred parts per million of CO2 and just under 1 part per million of CH4. Those changes to our atmosphere have been no accident; over geological time, life and its metabolic processes have evolved (such as the evolution of photosynthetic bacteria that consume CO2) and changed the atmosphere to conditions that remained cool enough to be habitable.

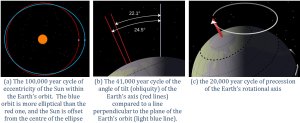

The position of the Earth relative to the Sun is another important component of natural climate forcing. Earth’s orbit around the Sun is nearly circular, but like all physical systems, it has natural oscillations. First, the shape of the orbit changes on a regular time scale (close to 100,000 years) from being close to circular to being very slightly elliptical. But the circularity of the orbit is not what matters; it is the fact that as the orbit becomes more elliptical, the position of the Sun within that ellipse becomes less central or more eccentric (Figure 6.5.1a). Eccentricity is important because when it is high, the Earth-Sun distance varies more from season to season than it does when eccentricity is low.

Second, Earth rotates around an axis through the North and South Poles, and that axis is at an angle to the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun (Figure 6.5.1b). The angle of tilt (also known as obliquity) varies on a time scale of 41,000 years. When the angle is at its maximum (24.5°), Earth’s seasonal differences are accentuated. When the angle is at its minimum (22.1°), seasonal differences are minimized. The current hypothesis is that glaciation is favored at low seasonal differences as summers would be cooler and snow would be less likely to melt and more likely to accumulate from year to year. Third, the direction in which Earth’s rotational axis points also varies, on a time scale of about 20,000 years (Figure 6.5.1c). This variation, known as precession, means that although the North Pole is presently pointing to the star Polaris (the pole star), in 10,000 years it will point to the star Vega. The importance of eccentricity, tilt, and precession to Earth’s climate cycles (now known as Milankovitch Cycles) was first pointed out by Yugoslavian engineer and mathematician Milutin Milankovitch in the early 1900s. Milankovitch recognized that although the variations in the orbital cycles did not affect the total amount of insolation (light energy from the Sun) that Earth received, it did affect where on Earth that energy was strongest.

Volcanic eruptions don’t just involve lava flows and exploding rock fragments; various particulates and gases are also released, the important ones being sulphur dioxide and CO2. Sulphur dioxide is an aerosol that reflects incoming solar radiation and has a net cooling effect that is short lived (a few years in most cases, as the particulates settle out of the atmosphere within a couple of years), and doesn’t typically contribute to longer-term climate change. Volcanic CO2 emissions can contribute to climate warming but only if a greater-than-average level of volcanism is sustained over a long time (at least tens of thousands of years). It is widely believed that the catastrophic end-Permian extinction (at 250 Ma) resulted from warming initiated by the eruption of the massive Siberian Traps over a period of at least a million years.

Ocean currents are important to climate, and currents also have a tendency to oscillate. Glacial ice cores show clear evidence of changes in the Gulf Stream that affected global climate on a time scale of about 1,500 years during the last glaciation. The east-west changes in sea-surface temperature and surface pressure in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO varies on a much shorter time scale of between two and seven years. These variations tend to garner the attention of the public because they have significant climate implications in many parts of the world. The strongest El Niños in recent decades were in 1983, 1998, and 2015 and those were very warm years from a global perspective. During a strong El Niño, the equatorial Pacific sea-surface temperatures are warmer than normal and heat the atmosphere above the ocean, which leads to warmer-than-average global temperatures.

Climate Feedbacks

As already stated, climate feedbacks are critically important in amplifying weak climate forcings into full-blown climate changes. Since Earth still has a very large volume of ice, mostly in the continental ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland, but also in alpine glaciers and permafrost, melting is one of the key feedback mechanisms. Melting of ice and snow leads to several different types of feedbacks, an important one being a change in albedo, or the reflectivity of a surface. Earth’s various surfaces have widely differing albedos, expressed as the percentage of light that reflects off a given material. This is important because most solar energy that hits a very reflective surface is not absorbed and therefore does little to warm Earth. Water in the oceans or on a lake is one of the darkest surfaces, reflecting less than 10% of the incident light, while clouds and snow or ice are among the brightest surfaces, reflecting 70% to 90% of the incident light. When sea ice melts, as it has done in the Arctic Ocean at a disturbing rate over the past decade, the albedo of the area affected changes dramatically, from around 80% down to less than 10%. Much more solar energy is absorbed by the water than by the pre-existing ice, and the temperature increase is amplified. The same applies to ice and snow on land, but the difference in albedo is not as great. When ice and snow on land melt, sea level rises. (Sea level is also rising because the oceans are warming and that increases their volume). A higher sea level means a larger proportion of the planet is covered with water, and since water has a lower albedo than land, more heat is absorbed and the temperature goes up a little more. Since the last glaciation, sea-level rise has been about 125 m; a huge area that used to be land is now flooded by heat-absorbent seawater. During the current period of anthropogenic climate change, sea level has risen only about 20 cm, and although that doesn’t make a big change to albedo, sea-level rise is accelerating.

Most of northern Canada, Alaska, Russia, and Scandinavia has a layer of permafrost that ranges from a few centimeters to hundreds of meters in thickness. Permafrost is a mixture of soil and ice and it also contains a significant amount of trapped organic carbon that is released as CO2 and CH4 when the permafrost breaks down. Because the amount of carbon stored in permafrost is in the same order of magnitude as the amount released by burning fossil fuels, this is a feedback mechanism that has the potential to equal or surpass the forcing that has unleashed it. In some polar regions, including northern Canada, permafrost includes methane hydrate, a highly concentrated form of CH4 trapped in solid form. Breakdown of permafrost releases this CH4. Even larger reserves of methane hydrate exist on the seafloor, and while it would take significant warming of ocean water down to a depth of hundreds of meters, this too is likely to happen in the future if we don’t limit our impact on the climate. There is strong isotopic evidence that the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum was caused, at least in part, by a massive release of sea-floor methane hydrate.

There is about 45 times as much carbon in the ocean (as dissolved bicarbonate ions, HCO3-) as there is in the atmosphere (as CO2), and there is a steady exchange of carbon between the two reservoirs (see section 5.5). But the solubility of CO2 in water decreases as the temperature goes up. In other words, the warmer it gets, the more oceanic bicarbonate that gets transferred to the atmosphere as CO2. That makes CO2 solubility another positive feedback mechanism. Vegetation growth responds positively to both increased temperatures and elevated CO2 levels, and so in general, it represents a negative feedback to climate change because the more the vegetation grows, the more CO2 is taken from the atmosphere. But it’s not quite that simple, because when trees grow bigger and more vigorously, forests become darker (they have lower albedo) so they absorb more heat. Furthermore, climate warming isn’t necessarily good for vegetation growth; some areas have become too hot, too dry, or even too wet to support the plant community that was growing there, and it might take centuries for something to replace it successfully. All of these positive (and negative) feedbacks work both ways. For example, during climate cooling, growth of glaciers leads to higher albedos, and formation of permafrost results in storage of carbon that would otherwise have returned quickly to the atmosphere.

Anthropogenic Climate Change

When we talk about anthropogenic climate change, we are generally thinking of the industrial era, which really got going when we started using fossil fuels (coal to begin with, and later oil and natural gas) to drive machinery and trains, and to generate electricity. That was around the middle of the 18th century. The issue with fossil fuels is that they involve burning carbon that was naturally stored in the crust over hundreds of millions of years as part of Earth’s process of counteracting the warming Sun.

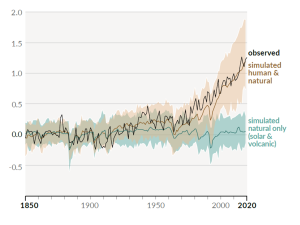

A rapidly rising population, the escalating level of industrialization and mechanization of our lives, and an increasing dependence on fossil fuels have driven the anthropogenic climate change of the past century. The trend of mean global temperatures since 1850 is shown in Figure 6.5.2. For approximately the past 55 years, the temperature has increased at a relatively steady and disturbingly rapid rate, especially compared to past changes. The average temperature now is approximately 1.1°C higher than before industrialization, and two-thirds of this warming has occurred since 1975.

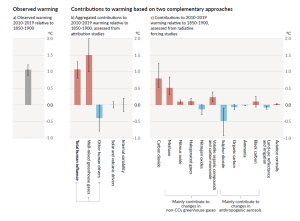

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established by the United Nations in 1988, is responsible for reviewing the scientific literature on climate change and issuing periodic reports on several topics, including the scientific basis for understanding climate change, our vulnerability to observed and predicted climate changes, and what we can do to limit climate change and minimize its impacts. Figure 6.5.3, from the sixth report of the IPCC, issued in preliminary form in 2021, shows the relative contributions of various greenhouse gases and other factors to current climate forcing, based on the changes from levels that existed in 1750.

The biggest anthropogenic contributor to warming is the emission of CO2, which accounts for 50% of positive forcing. CH4 and its atmospheric derivatives (CO2, H2O, and O3) account for 29%, and the halocarbon gases (mostly leaked from air-conditioning appliances) and nitrous oxide (N2O) (from burning fossils fuels) account for 5% each. Carbon monoxide (CO) (also produced by burning fossil fuels) accounts for 7%, and the volatile organic compounds other than methane (NMVOC) account for 3%. CO2 emissions come mostly from coal- and gas-fired power stations, motorized vehicles (cars, trucks, and aircraft), and industrial operations (e.g., smelting), and indirectly from forestry. CH4 emissions come from production of fossil fuels (escape from coal mining and from gas and oil production), livestock farming (mostly beef), landfills, and wetland rice farming. N2O and CO come mostly from the combustion of fossil fuels. In summary, close to 70% of our current greenhouse gas emissions come from fossil fuel production and use, while most of the rest comes from agriculture and landfills. Figure 6.5.4 shows the IPCC’s projections for temperature increases over the next 100 years as a result of these increasing greenhouse gases.

Impacts of Climate Change

We’ve all experienced the effects of climate change over the past decade. However, it’s not straightforward for climatologists to make the connection between a warming climate and specific weather events, and most are justifiably reluctant to ascribe any specific event to climate change. In this respect, the best measures of climate change are those that we can detect over several decades, such as the temperature changes shown in Figure 6.5.2, or the sea level rise shown in Figure 6.5.5. As already stated, sea level has risen approximately 20 cm since 1750, and that rise is attributed to both warming (and therefore expanding) seawater and melting glaciers and other land-based snow and ice (melting of sea ice does not contribute directly to sea level rise as it is already floating in the ocean).

Projections for sea level rise to the end of this century vary widely. This is in large part because we do not know which of the above climate change scenarios (Figure 6.5.4) we will most closely follow, but many are in the range from 0.5 m to 2.0 m. One of the problems in predicting sea level rise is that we do not have a strong understanding of how large ice sheets, such as Greenland and Antarctica, will respond to future warming. Another issue is that the oceans don’t respond immediately to warming. For example, with the current amount of warming, we are already committed to a future sea level rise of between 1.3 m and 1.9 m, even if we could stop climate change today. This is because it takes decades to centuries for the existing warming of the atmosphere to be transmitted to depth within the oceans and to exert its full impact on large glaciers. Most of that committed rise would take place over the next century, but some would be delayed longer. And for every decade that the current rates of climate change continue, that number increases by another 0.3 m. In other words, if we don’t make changes quickly, by the end of this century we’ll be locked into 3 m of future sea level rise. In a 2008 report, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated that by 2070 approximately 150 million people living in coastal areas could be at risk of flooding due to the combined effects of sea level rise, increased storm intensity, and land subsidence. The assets at risk (buildings, roads, bridges, ports, etc.) are in the order of $35 trillion ($35,000,000,000,000). Countries with the greatest exposure of population to flooding are China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, U.S.A., Japan, and Thailand. Some of the major cities at risk include Shanghai, Guangzhou, Mumbai, Kolkata, Dhaka, Ho Chi Minh City, Tokyo, Miami, and New York.

One of the other risks for coastal populations, besides sea level rise, is that climate warming is also associated with an increase in the intensity of tropical storms (e.g., hurricanes or typhoons; see section 6.4), which almost always bring serious flooding from intense rain and storm surges. Some recent examples are New Orleans in 2005 with Hurricane Katrina, and New Jersey and New York in 2012 with Hurricane Sandy. Tropical storms get their energy from the evaporation of warm seawater in tropical regions. In the Atlantic Ocean, this takes place between 8° and 20° N in the summer. Figure 6.5.6 shows the variations in the sea-surface temperature (SST) of the tropical Atlantic Ocean (in blue) versus the amount of power represented by Atlantic hurricanes between 1950 and 2008 (in red). Not only has the overall intensity of Atlantic hurricanes increased with the warming since 1975, but the correlation between hurricanes and sea-surface temperatures is very strong over that time period.

The geographical ranges of diseases and pests, especially those caused or transmitted by insects, have been shown to extend toward temperate regions because of climate change. West Nile virus and Lyme disease are two examples that already directly affect North Americans, while dengue fever could be an issue in the future (dengue became a "nationally notifiable condition" in the United States in 2010). For several weeks in July and August of 2010, a massive heat wave affected western Russia, especially the area southeast of Moscow, and scientists have stated that climate change was a contributing factor. Temperatures soared to over 40°C, as much as 12°C above normal over a wide area, and wildfires raged in many parts of the country. Over 55,000 deaths are attributed to the heat and to respiratory problems associated with the fires. A summary of the impacts of climate change on natural disasters is given in Figure 6.5.7. The major types of disasters related to climate are floods and storms, but the health implications of extreme temperatures are also becoming a great concern. In the decade 1971 to 1980, extreme temperatures were the fifth most common natural disasters; by 2001 to 2010, they were the third most common.

Convergent boundaries, where two plates are moving toward each other, are of three types, depending on the type of crust present on either side of the boundary — oceanic or continental. The types are ocean-ocean, ocean-continent, and continent-continent.

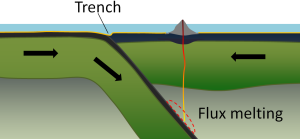

At an ocean-ocean convergent boundary, one of the plates (oceanic crust and lithospheric mantle) is pushed, or subducted, under the other (Figure 2.6.1). Often it is the older and colder plate that is denser and subducts beneath the younger and warmer plate. There is commonly an ocean trench along the boundary as the crust bends downwards. The subducted lithosphere descends into the hot mantle at a relatively shallow angle close to the subduction zone, but at steeper angles farther down (up to about 45°). The significant volume of water within the subducting material is released as the subducting crust is heated. It mixes with the overlying mantle, and the addition of water to the hot mantle lowers the crust’s melting point and leads to the formation of magma (flux melting). The magma, which is lighter than the surrounding mantle material, rises through the mantle and the overlying oceanic crust to the ocean floor where it creates a chain of volcanic islands known as an island arc. A mature island arc develops into a chain of relatively large islands (such as Japan or Indonesia) as more and more volcanic material is extruded and sedimentary rocks accumulate around the islands. Earthquakes occur relatively deep below the seafloor, where the subducting crust moves against the overriding crust.

Examples of ocean-ocean convergent zones are subduction of the Pacific Plate south of Alaska (creating the Aleutian Islands) and under the Philippine Plate, where it creates the Marianas Trench, the deepest part of the ocean.

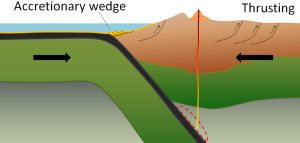

At an ocean-continent convergent boundary, the denser oceanic plate is pushed under the less dense continental plate in the same manner as at an ocean-ocean boundary. Sediment that has accumulated on the seafloor is thrust up into an accretionary wedge, and compression leads to thrusting within the continental plate (Figure 2.6.2). The magma produced adjacent to the subduction zone rises to the base of the continental crust and leads to partial melting of the crustal rock. The resulting magma ascends through the crust, producing a mountain chain with many volcanoes. As with an ocean-ocean boundary, the subducting crust can produce a deep trench running parallel to the coastline.

Examples of ocean-continent convergent boundaries are subduction of the Nazca Plate under South America (which has created the Andes Mountains and the Peru Trench) and subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate under North America (creating the Cascade Range).

A continent-continent collision occurs when a continent or large island that has been moved along with subducting oceanic crust collides with another continent (Figure 2.6.3). The colliding continental material will not be subducted because it is too light (i.e., because it is composed largely of light continental rocks), but the root of the oceanic plate will eventually break off and sink into the mantle. There is tremendous deformation of the pre-existing continental rocks, forcing the material upwards and creating mountains.

Examples of continent-continent convergent boundaries are the collision of the India Plate with the Eurasian Plate, creating the Himalaya Mountains, and the collision of the African Plate with the Eurasian Plate, creating the series of ranges extending from the Alps in Europe to the Zagros Mountains in Iran.

With so many variables playing a role in the production of tides, it is understandable that not every place on Earth will experience exactly the same tidal conditions. There are three primary classifications for tides, depending on the number and relative heights of tidal cycles per day.

A diurnal tide consists of only one high tide and one low tide per day (Figure 3.7.1). "Diurnal" refers to a daily occurrence, so a situation where there is only one complete tidal cycle per day is considered a diurnal tide. Diurnal tides are common in the Gulf of Mexico, along the west coast of Alaska, and in parts of Southeast Asia.

A semidiurnal tide exhibits two high and two low tides each day, with both highs and both lows of toughly equal height (Figure 3.7.2). "Semidiurnal" means "half of a day"; one tidal cycle takes half of a day, therefore there are two complete cycles per day. Semidiurnal tides are common along the east coasts of North America and Australia, the west coast of Africa, and most of Europe.

Mixed semidiurnal tides (or mixed tides), have two high tides and two low tides per day, but the heights of each tide differs; the two high tides are of different heights, as are the two low tides (Figure 3.7.3). The differences in height may be the result of amphidromic circulation, the angle of the moon, or any of the other variables discussed in section 3.6. Mixed semidiurnal tides are found along the Pacific coast of North America.

Figure 3.7.4 shows the distribution of the various tide types throughout the world.

Tidal Currents

The movement of water with the rising and falling tide creates tidal currents. As the tide rises, water flows into an area, creating a flood current. As the tide falls and water flows out an ebb current is created. Slack water, or slack tides occur during the transition between incoming high and outgoing low tides, when there is no net water movement.

The strength of a tidal current depends on the volume of water that enters and exits with each tidal cycle (the tidal volume or tidal prism), and the area through which the water flows. A large tidal volume moving through a large area may create only a weak tidal current, as the volume is spread over a wide area. On the other hand, a narrow area may produce a strong tidal current even if the tidal volume is small, as all of the water is forced through a small area. It follows that the strongest tidal currents will result from a large tidal range moving through a narrow area.

Tidal bores occur where rivers meet the ocean. If the incoming tidal current is stronger than the river outflow, the tidal bore appears as a wave, or moving wall of water that moves up the river as the tide comes in (Figure 3.7.5).

In many cases these tidal bores may move through a river or inlet for many kilometers, and if they are large enough they can form continually breaking waves that surfers can ride much farther and longer than a traditional ocean wave, such as the Severn Bore in England, shown in the video below.

https://youtu.be/IKA39LQOIck

Additional links for more information

- For an even more dramatic tidal bore, watch this video of the "Silver Dragon" on China's Qiantang River

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

In the previous chapter the major wind patterns on Earth were derived. It is these prevailing winds that blow across the water surface to create the major ocean surface currents. However, only about 2% of the wind energy is actually transferred to the water, so a 50 knot wind only creates a 1 knot current. Furthermore, wind-driven surface currents only affect the top 100-200m of water, meaning surface currents only involve about 10% of the world’s ocean water. In section 7.8 we will examine deep, thermohaline circulation, which impacts around 90% of the ocean water.

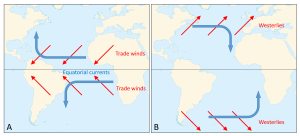

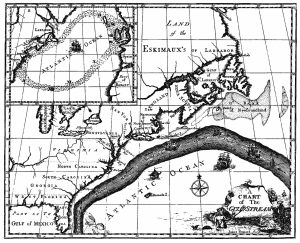

Surface currents generally move in the same direction as the winds that created them. However, because of Coriolis deflection, the surface currents are offset approximately 45o relative to the wind direction; 45o to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, and 45o to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. This creates a general circulation pattern where in both hemispheres, surface currents flow east to west between the equator and 30o latitude, west to east between 30o and 60o, and east to west between 60o and the poles (Figure 7.1.1).

The trade winds create the equatorial currents that flow east to west along the equator; the North Equatorial and South Equatorial currents. If there were no continents, these surface currents would travel all the way around the Earth, parallel to the equator. However, the presence of the continents prevents this unimpeded flow. When these equatorial currents reach the continents, they are diverted and deflected away from the equator by the Coriolis Effect; deflection to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. These currents then become western boundary currents; currents that run along the western side of the ocean basin (i.e. the east coasts of the continents). Since these currents come from the equator, they are warm water currents, bringing warm water to the higher latitudes and distributing heat throughout the ocean.

At the same time, between 30-60o latitude the westerlies move surface water towards the east. The Coriolis Effect and the presence of the continents deflect the currents towards the equator, creating eastern boundary currents (on the eastern side of the ocean basins). These currents come from high latitude areas, so they deliver cold water to the lower latitudes. Together, these currents combine to create large-scale circular patterns of surface circulation called gyres. In the Northern Hemisphere the gyres rotate to the right (clockwise), while in the Southern Hemisphere the gyres rotate to the left (counterclockwise).

There are five major gyres in the oceans; the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific, and Indian (Figure 7.1.2). The North Pacific gyre is composed of the North Equatorial Current on its southern boundary, which turns into the Kuroshio Current (a.k.a. the Japan Current) bringing warm water north towards Japan. The Kuroshio flows into the North Pacific Current which moves east towards North America, where it becomes the California Current to complete the gyre. The North Atlantic gyre is formed by the North Equatorial Current flowing into the Gulf Stream along the east coast of the United States. The Gulf Stream merges into the North Atlantic Current to move water towards Europe, which then becomes the Canary Current as it moves south to join the North Equatorial Current.

Near Antarctica the circulation is somewhat different. Because there is little in the way of continental land masses between 50-60o south, the surface current created by the westerly winds can make its way completely around the Earth, creating the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) or West Wind Drift (WWD) that flows from west to east (Figure 7.1.2). The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the only current that connects all of the major ocean basins, and in terms of the amount of water that it transports, it is the largest surface current on Earth. Above 60o latitude the prevailing winds are the polar easterlies, which create a current flowing from east to west along the edge of the Antarctic continent, the East Wind Drift or the Antarctic Coastal Current.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current creates the southern boundary for all of the Southern Hemisphere gyres. In the South Pacific gyre the ACC becomes the Peru Current (also known as the Humboldt Current) moving up the west coast of South America, before joining the South Equatorial Current. The South Equatorial Current flows southwards as the East Australia Current, before completing the gyre with the ACC. The South Atlantic gyre is composed of the South Equatorial Current, the Brazil Current, the ACC, and the Benguela Current. Finally, the currents making up the Indian gyre are the ACC, the West Australia Current, the South Equatorial Current, and the Agulhas Current.

Not all of the equatorial water that is moved westward by the trade winds and reaches the continents gets transported to higher latitudes in the gyres, because the Coriolis Effect is weakest along the equator. Instead, some of the water piles up along the western edge of the ocean, and then flows eastward due to gravity, creating narrow Equatorial Countercurrents between the North and South Equatorial Currents (Figure 7.1.2). Some of this water also moves east as equatorial undercurrents that flow at depths between 50-200 m, underneath the Equatorial Currents. These undercurrents are called the Lomonosov Current in the Atlantic, and the Cromwell Current in the Pacific.

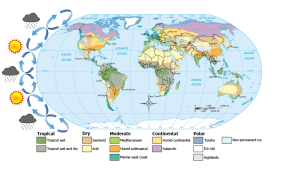

In the previous section we learned that rising air creates low pressure systems, and sinking air creates high pressure. In addition to their role in creating the surface winds, these high and low pressure systems also influence other climatic phenomena. Along the equator air is rising as it is warmed by solar radiation (section 6.2). Warm air contains more water vapor than cold air, which is why we experience humidity during the summer and not during the winter. The water content of air roughly doubles with every 10o C increase in temperature. So the air rising at the equator is warm and full of water vapor; as it rises into the upper atmosphere it cools, and the cool air can no longer hold as much water vapor, so the water condenses and forms rain. Therefore, low pressure systems are associated with precipitation, and we see wet habitats like tropical rainforests near the equator (Figure 6.3.1).

After rising and producing rain near the equator, the air masses move towards 30o latitude and sink back towards Earth as part of the Hadley convection cells. This air has lost most of its moisture after producing the equatorial rains, so the sinking air is dry, resulting in arid climates near 30o latitude in both hemispheres. Many of the major desert regions on Earth are located near 30o latitude, including much of Australia, the Middle East, and the Sahara Desert of Africa (Figure 6.3.1). The air also becomes compressed and heats up as it sinks, absorbing any moisture from the clouds and creating clear skies. Thus high pressure systems are associated with dry weather and clear skies. This cycle of high and low pressure regions continues with the Ferrel and Polar convection cells, leading to rain and the boreal forests at 60o latitude in the Northern Hemisphere (there are no corresponding large land masses at these latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere). At the poles, descending, dry air produces little precipitation, leading to the polar desert climate.

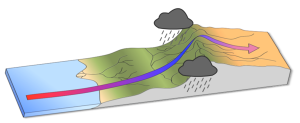

The elevation of the land also plays a role in precipitation and climactic characteristics. As moist air moves over land and encounters mountains it rises, expands, and cools because of the declining pressure and temperature. The cool air holds less water vapor, so condensation occurs and rain falls on the windward side of the mountains. As the air passes over the mountains to the leeward side, it is now dry air, and as it sinks the pressure increases, it heats back up, any moisture revaporizes, and it creates dry, deserts regions behind the mountains (Figure 6.3.2). This phenomenon is referred to as a rain shadow, and can be found in areas such as the Tibetan Plateau and Gobi Desert behind the Himalayas, Death Valley behind the Sierra Nevada mountains, and the dry San Joaquin Valley in California.

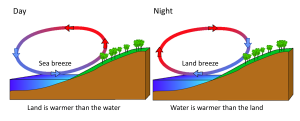

Rising and falling air are also responsible for more localized, short-term wind patterns in coastal areas. Due to the high heat capacity of water, land heats up and cools down about five times faster than water. During the day the sun heats up the land faster than it heats the water, setting up a convection cell of warmer rising air over the land and sinking cooler air over the water. This creates winds blowing from the water towards the land during the day and early evening; a sea breeze (Figure 6.3.3). The opposite occurs at night, when the land cools more quickly than the ocean. Now the ocean is warmer than the land, so air rises over the water and sinks over the land, creating a convection cell where winds blow from land towards the water. This is a land breeze, which blows at night and into the early morning (Figure 6.3.3).

The same phenomenon leads to seasonal climatic changes in many areas. During the winter the lower pressure is over the warmer ocean, and the high pressure is over the colder land, so winds blow from land to sea. In summer the land is warmer than the ocean, causing low pressure over the land and winds to blow from the ocean towards the land. The winds blowing from the ocean contain a lot of water vapor, and as the moist air passes over land and rises, it cools and condenses causing seasonal rains, such as the summer monsoons of southeast Asia (Figure 6.3.4).

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- identify the major ocean surface currents of the world (i.e. the gyres) and explain how they are formed

- identify the features of the Gulf Stream, including the formation of warm and cold core rings

- explain the development and consequences of the Ekman spiral

- explain geostrophic flow, and how it helps keep the gyres flowing even when wind dies down.

- explain why gyre currents are more intense on the western side of the oceans (western intensification)

- explain the causes behind upwelling and downwelling, and the impacts of these events on primary production

- identify the locations of some of the major upwelling regions on Earth

- explain the causes and effects of ENSO events

- explain Langmuir cells

- explain the processes that drive thermohaline circulation

- interpret a T-S diagram to identify water masses

- identify the major global sites of deep water formation

- identify the major global water masses

- explain how deep water circulates throughout the world ocean

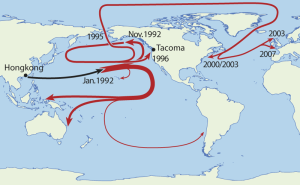

Ocean waters are constantly in motion, from ocean-scale surface currents, to density-driven vertical turnover, to small rotating eddies. Oceanographers have an array of sophisticated tools to measure ocean currents, but from time to time, fortuitous accidents can also aid our understanding of ocean circulation. A great example is the case of the container ship Ever Laurel, which was on its way from Hong Kong to Tacoma, Washington, in January 1992, when 12 containers were washed overboard in a storm in the middle of the Pacific. One of the containers contained over 28,000 plastic bath toys, which were released into the ocean as the container hit the water. Ten months later, the bath toys began washing ashore, first near Sitka, Alaska, then elsewhere along the Alaskan coast, and by 1996, in Washington. Over the next two decades, some toys traveled as far as the Pacific coasts of South America and Australia, while others were found in the Arctic ice, and some even made it through the Arctic into the North Atlantic, washing up in Newfoundland and Scotland (Figure 10.1). There are still a few thousand of the toys floating around in the central North Pacific, and the paths taken by all of these toys have allowed oceanographers to study the movements of large-scale ocean surface currents.

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- identify the major ocean surface currents of the world (i.e. the gyres) and explain how they are formed

- identify the features of the Gulf Stream, including the formation of warm and cold core rings

- explain the development and consequences of the Ekman spiral

- explain geostrophic flow, and how it helps keep the gyres flowing even when wind dies down.

- explain why gyre currents are more intense on the western side of the oceans (western intensification)

- explain the causes behind upwelling and downwelling, and the impacts of these events on primary production

- identify the locations of some of the major upwelling regions on Earth

- explain the causes and effects of ENSO events

- explain Langmuir cells

- explain the processes that drive thermohaline circulation

- interpret a T-S diagram to identify water masses

- identify the major global sites of deep water formation

- identify the major global water masses

- explain how deep water circulates throughout the world ocean

Ocean waters are constantly in motion, from ocean-scale surface currents, to density-driven vertical turnover, to small rotating eddies. Oceanographers have an array of sophisticated tools to measure ocean currents, but from time to time, fortuitous accidents can also aid our understanding of ocean circulation. A great example is the case of the container ship Ever Laurel, which was on its way from Hong Kong to Tacoma, Washington, in January 1992, when 12 containers were washed overboard in a storm in the middle of the Pacific. One of the containers contained over 28,000 plastic bath toys, which were released into the ocean as the container hit the water. Ten months later, the bath toys began washing ashore, first near Sitka, Alaska, then elsewhere along the Alaskan coast, and by 1996, in Washington. Over the next two decades, some toys traveled as far as the Pacific coasts of South America and Australia, while others were found in the Arctic ice, and some even made it through the Arctic into the North Atlantic, washing up in Newfoundland and Scotland (Figure 10.1). There are still a few thousand of the toys floating around in the central North Pacific, and the paths taken by all of these toys have allowed oceanographers to study the movements of large-scale ocean surface currents.

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

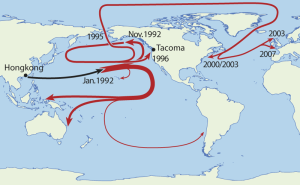

The primary surface current along the east coast of the United States is the Gulf Stream, which was first mapped by Benjamin Franklin in the 18th century (Figure 7.2.1). As a strong, fast current, it reduced the sailing time for ships traveling from the United States back to Europe, so sailors would use thermometers to locate its warm water and stay within the current.

The Gulf Stream is formed from the convergence of the North Atlantic Equatorial Current bringing tropical water from the east, and the Florida Current that brings warm water from the Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf Stream takes this warm water and transports it northwards along the U.S. east coast (Figure 7.2.2). As a western boundary current, the Gulf Stream experiences western intensification (section 7.4), making the current narrow (50-100 km wide), deep (to depths of 1.5 km) and fast. With an average speed of 6.4 km/hr, and a maximum speed of about 9 km/hr, it is the fastest current in the world ocean. It also transports huge amounts of water, more than 100 times greater than the combined flow of all of the rivers on Earth.

As the Gulf Stream approaches Canada, the current becomes wider and slower as the flow dissipates and it encounters the cold Labrador Current moving in from the north. At this point, the current begins to meander, or change from a fast, straight flow to a slower, looping current (Figure 7.2.2). Often these meanders loop so much that they pinch off and form large rotating water masses called rings or eddies, that separate from the Gulf Stream. If an eddy pinches off from the north side of the Gulf Stream, it entraps a mass of warm water and moves it north into the surrounding cold water of the North Atlantic. These warm core rings are shallow, bowl-shaped water masses about 1 km deep, and about 100 km across, that rotate clockwise as they carry warm water in to the North Atlantic (Figure 7.2.3). If the meanders pinch off at the southern boundary of the Gulf Stream, they form cold core rings that rotate counterclockwise and move to the south. Cold core rings are cone-shaped water masses extending down to over 3.5 km deep, and may be over 500 km wide at the surface.

After the Gulf Stream meets the cold Labrador Current, it joins the North Atlantic Current, which transports the warm water towards Europe, where it moderates the European climate. It is estimated that Northern Europe is up to 9o C warmer than expected because of the Gulf Stream, and the warm water helps to keep many northern European ports ice-free in the winter.

In the east, the Gulf Stream merges into the Sargasso Sea, which is the area of the ocean within the rotation center of the North Atlantic gyre. The Sargasso Sea gets its name from the large floating mats of the marine algae Sargassum that are abundant on the surface (Figure 7.2.4). These Sargassum mats may play an important role in the early life stages of sea turtles, who may live and feed within the algae for many years before reaching adulthood.

In the previous chapter the major wind patterns on Earth were derived. It is these prevailing winds that blow across the water surface to create the major ocean surface currents. However, only about 2% of the wind energy is actually transferred to the water, so a 50 knot wind only creates a 1 knot current. Furthermore, wind-driven surface currents only affect the top 100-200m of water, meaning surface currents only involve about 10% of the world’s ocean water. In section 7.8 we will examine deep, thermohaline circulation, which impacts around 90% of the ocean water.

Surface currents generally move in the same direction as the winds that created them. However, because of Coriolis deflection, the surface currents are offset approximately 45o relative to the wind direction; 45o to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, and 45o to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. This creates a general circulation pattern where in both hemispheres, surface currents flow east to west between the equator and 30o latitude, west to east between 30o and 60o, and east to west between 60o and the poles (Figure 7.1.1).

The trade winds create the equatorial currents that flow east to west along the equator; the North Equatorial and South Equatorial currents. If there were no continents, these surface currents would travel all the way around the Earth, parallel to the equator. However, the presence of the continents prevents this unimpeded flow. When these equatorial currents reach the continents, they are diverted and deflected away from the equator by the Coriolis Effect; deflection to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. These currents then become western boundary currents; currents that run along the western side of the ocean basin (i.e. the east coasts of the continents). Since these currents come from the equator, they are warm water currents, bringing warm water to the higher latitudes and distributing heat throughout the ocean.

At the same time, between 30-60o latitude the westerlies move surface water towards the east. The Coriolis Effect and the presence of the continents deflect the currents towards the equator, creating eastern boundary currents (on the eastern side of the ocean basins). These currents come from high latitude areas, so they deliver cold water to the lower latitudes. Together, these currents combine to create large-scale circular patterns of surface circulation called gyres. In the Northern Hemisphere the gyres rotate to the right (clockwise), while in the Southern Hemisphere the gyres rotate to the left (counterclockwise).

There are five major gyres in the oceans; the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific, and Indian (Figure 7.1.2). The North Pacific gyre is composed of the North Equatorial Current on its southern boundary, which turns into the Kuroshio Current (a.k.a. the Japan Current) bringing warm water north towards Japan. The Kuroshio flows into the North Pacific Current which moves east towards North America, where it becomes the California Current to complete the gyre. The North Atlantic gyre is formed by the North Equatorial Current flowing into the Gulf Stream along the east coast of the United States. The Gulf Stream merges into the North Atlantic Current to move water towards Europe, which then becomes the Canary Current as it moves south to join the North Equatorial Current.

Near Antarctica the circulation is somewhat different. Because there is little in the way of continental land masses between 50-60o south, the surface current created by the westerly winds can make its way completely around the Earth, creating the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) or West Wind Drift (WWD) that flows from west to east (Figure 7.1.2). The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the only current that connects all of the major ocean basins, and in terms of the amount of water that it transports, it is the largest surface current on Earth. Above 60o latitude the prevailing winds are the polar easterlies, which create a current flowing from east to west along the edge of the Antarctic continent, the East Wind Drift or the Antarctic Coastal Current.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current creates the southern boundary for all of the Southern Hemisphere gyres. In the South Pacific gyre the ACC becomes the Peru Current (also known as the Humboldt Current) moving up the west coast of South America, before joining the South Equatorial Current. The South Equatorial Current flows southwards as the East Australia Current, before completing the gyre with the ACC. The South Atlantic gyre is composed of the South Equatorial Current, the Brazil Current, the ACC, and the Benguela Current. Finally, the currents making up the Indian gyre are the ACC, the West Australia Current, the South Equatorial Current, and the Agulhas Current.

Not all of the equatorial water that is moved westward by the trade winds and reaches the continents gets transported to higher latitudes in the gyres, because the Coriolis Effect is weakest along the equator. Instead, some of the water piles up along the western edge of the ocean, and then flows eastward due to gravity, creating narrow Equatorial Countercurrents between the North and South Equatorial Currents (Figure 7.1.2). Some of this water also moves east as equatorial undercurrents that flow at depths between 50-200 m, underneath the Equatorial Currents. These undercurrents are called the Lomonosov Current in the Atlantic, and the Cromwell Current in the Pacific.

Tsunamis loom large in popular culture, but there are a number of misconceptions about these large waves. First, tsunamis have nothing to do with the tides, so it is a misnomer to refer to them as "tidal waves." There are actual tidal waves (see section 3.5), but they are not related to tsunamis. Second, the giant, curling wave that is taller than skyscrapers and destroys cities in science fiction movies is also a fabrication, as tsunamis do not behave that way, as described below.

Tsunamis are large waves that are usually the result of seismic activity, such as the rising or falling of the seafloor due to earthquakes, although volcanic activity and landslides can also cause tsunamis in the form of splash waves (see section 3.1). As the seafloor rises or falls, so does the water column above it, creating waves. Only vertical seismic disturbances cause tsunamis, not horizontal movements. These vertical seafloor movements are usually less than 10 m high, so the resulting wave will be of an equal or lesser height at sea. While the tsunamis have a relatively small height at the point of origin, they have very long wavelengths (100-200 km). Because of the long wavelength, they behave as shallow water waves throughout the entire ocean; the depth of the ocean is always shallower than half of their wavelength. As shallow water waves, their speed depends on water depth, but they can still travel at speeds over 750 km/hr (Figure 3.4.1)!

Figure 3.4.1 Animation of the spread of tsunamis created during the 2004 Indonesia earthquake (NOAA Center for Tsunami Research (NCTR) [Public domain]).

When tsunamis approach land, they behave just like any other wave; as the depth becomes shallower, the waves slow down and the wave height begins to increase. However, contrary to popular belief, tsunamis do not arrive on shore as giant, cresting waves. Since their wavelength is so long, it is impossible for their height to ever exceed 1/7 of their wavelength, so the waves don’t actually curl or break. Instead, they usually hit the shore as sudden surges of water causing a very rapid increase in sea level, like that of an enormous rise in tide. It may take several minutes for the wave to pass, during which time sea level can rise to 40 m higher than usual.

Large tsunamis occur every 2-3 years, with very large, damaging events happening every 15-20 years. The most devastating tsunami in terms of loss of life resulted from a magnitude 9 earthquake in Indonesia in 2004 (Figure 3.4.2), which created waves up to 33 m tall and left about 230,000 people dead in Indonesia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka. In 2011 a 9.0 magnitude earthquake in Japan triggered a tsunami up to 40.5 m high, which resulted in over 18,000 deaths. This earthquake also caused the Fukishima nuclear accident, and moved Japan about 8 inches closer to the U.S.

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/