23 3.6 Dynamic Theory of Tides

The Equilibrium Theory of tides predicts that each day there will be two high and two low tides, each one occurring at the same time day after day, with each pair producing tides of similar heights. While this view provides a basic explanation for the primary forces that generate the tides, it does not take into account such variables as the effects of the continents, the depth of the water, and many other factors. In all, there are almost 400 variables that must be incorporated into predicting the tides! The Dynamic Theory of tides takes these other factors into account, and shows that the tides are much more complicated and variable from place to place than the Equilibrium Theory would suggest. For example, some areas receive only one high and one low tide per day (see section 3.7). Furthermore, the tidal range varies greatly across the globe; in the Mediterranean Sea, there can be a difference of only 10 cm between high and low tides, while the Bay of Fundy in Canada experiences a tidal range of up to 17m (56 ft) every day (Figure 3.6.1).

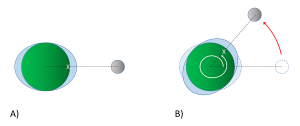

Examination of any tide chart will show that the tides don’t occur at same time each day; in fact, each tidal peak occurs about 50 minutes later than it did in the previous day. This is due to the orbit of the moon around the Earth. Imagine a high tide that occurs at a particular location (X) at 1:00 pm (Figure 3.6.2). The high tide occurs as location X moves through the bulge of water facing the moon. It will take the Earth 24 hours to complete one revolution, to bring location X back to site of the water bulge that caused that high tide. However, during those 24 hours, the moon has also moved as it orbits the Earth, so the high tide bulge has moved beyond its original location. The Earth thus has to rotate an additional distance for location X to reach the bulge and experience that same high tide. Because it takes the moon about 28 days to orbit the Earth, the moon gets “ahead” of the Earth’s rotation by about 50 minutes per day. Therefore, it takes location X 24 hours and 50 minutes to rotate through the same tidal bulge, and as a result, the tidal peaks occur about 50 minutes later each day. In our example, an afternoon high tide at 1:00 pm on one day would be followed by a high tide at about 1:50 pm the following day. This 24 hour and 50 minute cycle is referred to as a tidal day.

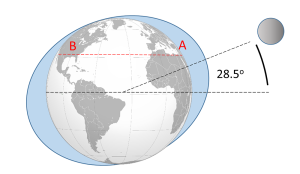

The motion of the moon impacts the tidal cycles in other ways. As the moon orbits the Earth, its orbital plane is at an angle relative to the rotational plane of Earth. This angle, or declination, means than the moon fluctuates between an angle of 28.5o north of the equator, to 28.5o south of the equator roughly every two weeks (the cycle from maximum to minimum and back takes about 27 days). Figure 3.6.3 illustrates a case where the moon is at its maximum declination 28.5o north of the equator, creating its corresponding tidal maxima. A point on the Earth at the latitude indicated by the red line would experience two high tides as it rotated through 24 hours, at points A and B. But the two high tides would not be of equal heights; the high tide at A would be higher than the high tide at B. This helps create a mixed semi-diurnal tide; two high tides of different heights per day (see section 3.7).

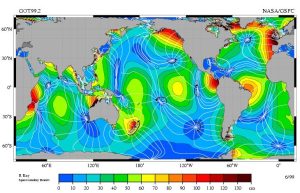

Finally, the continents and the bottom topography of the oceans have an impact on the tides that are experienced in an area. Because the tides are essentially waves with extremely long wavelengths extending halfway across the Earth, they behave as shallow water waves, and they are influenced and refracted by the bottom contours, leading to regional tidal variations. When the tidal crests encounter land, they are are reflected, and the wave moves back out to sea, theoretically until it encounters another continent on the opposite side of the ocean basin. The crest is once again reflected, and the water oscillates back and forth as a standing wave across the ocean basin. However, because of the scale over which these tidal waves move, we must take into account the influence of the Coriolis Effect. As the tidal crest is reflected back across the ocean basin, its path is deflected by the Coriolis force; to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. Using the Northern Hemisphere as an example, imagine a tidal crest that has reached land on the western side of an ocean basin. It would have a tendency to be reflected and move across the basin towards the east. But the Coriolis force deflects the movement to the right, causing the crest to instead head south. When the crest hits land in the south, it would now tend to reflect towards the north, but once again the Coriolis deflection to the right kicks in, and the wave instead moves to the east. From the east the reflected wave is deflected to the north, and so on. The result of all of this is that instead of a simple standing wave moving back and forth across the ocean, the tidal crest follows a circular pattern around the ocean basin, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. This is analogous to shaking a pan full of water in a circular manner, and watching the water follow a similar circular path as it sloshes around inside. This large scale circular rotation pattern of tides is called amphidromic circulation (Figure 3.6.4). The rotation occurs around a central amphidromic point or node, that shows little tidal variation, while the largest tidal ranges occur on the edges of the circulation pattern. In Figure 3.6.4 the amphidromic points are indicated by the dark blue areas where the white lines converge, like spokes from a bicycle wheel, and the dark red and brown areas show the regions of maximum tidal heights. The tidal maxima will rotate around the amphidromic points, taking about 12 hours for a complete rotation, leading to two high and two low tides per day in many places. If a tidal maximum is occurring along one of the white lines in Figure 3.6.4 at a certain time in the Northern Hemisphere, one hour later that high tide will have moved to the white line to the left (counterclockwise), and so on until it completes a rotation. In the Southern Hemisphere, the tide will move to the line to the right for clockwise rotation.

The result of all of these variables is that the tides will not always occur twice each day, at the same time and with equal heights as the Equilibrium Theory of tides may suggest. Instead, each region of the oceans has a unique set of factors that contribute to the types of tides it will experience. The major types of tides are discussed in the next section.

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

If one thing has been constant about Earth’s climate over geological time, it is its constant change. In the geological record, we can see this in the evidence of glaciations in the distant past, and we can also detect periods of extreme warmth by looking at the isotope composition of seafloor sediments. Not only has the climate changed frequently, the temperature fluctuations have been very significant. Today’s mean global temperature is about 15°C. However, during its coldest periods, the global mean was as cold as -50°C, while at various times during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic and during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum, it was close to 30°C.

There are two parts to climate change, the first one is known as climate forcing, which is when conditions change to give the climate a little nudge in one direction or the other. The second part of climate change, and the one that typically does most of the work, is what we call a feedback. When a climate forcing changes the climate a little, a whole series of environmental changes take place, many of which either exaggerate the initial change (positive feedback), or suppress the change (negative feedback).

An example of a climate forcing mechanism is the increase in the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere that results from our use of fossil fuels. CO2 traps heat in the atmosphere and leads to climate warming. Warming changes vegetation patterns; contributes to the melting of snow, ice, and permafrost; causes sea level to rise; reduces the solubility of CO2 in sea water; and has a number of other minor effects. Most of these changes contribute to more warming. Melting of permafrost, for example, is a strong positive feedback because frozen soil contains trapped organic matter that is converted to CO2 and methane (CH4) when the soil thaws. Both these gases accumulate in the atmosphere and add to the warming effect. On the other hand, if warming causes more vegetation growth, that vegetation should absorb CO2, thus reducing the warming effect, which would be a negative feedback. Under our current conditions — a planet that still has lots of glacial ice and permafrost — most of the feedbacks that result from a warming climate are positive feedbacks and so the climate changes that we cause get naturally amplified by natural processes.

Natural Climate Forcing

Natural climate forcing has been going on throughout geological time. A wide range of processes has been operating at widely different time scales, from a few years to billions of years. The longest-term natural forcing variation is related to the evolution of the Sun. Like most other stars of a similar mass, our Sun is evolving. For the past 4.6 billion years, its rate of nuclear fusion has been increasing, and it is now emitting about 40% more energy (as light) than it did at the beginning of geological time. A difference of 40% is big, so it’s a little surprising that the temperature on Earth has remained at a reasonable and habitable temperature for all of this time. The mechanism for that relative climate stability has been the evolution of our atmosphere from one that was dominated by CO2, and also had significant levels of CH4 — both greenhouse gasses — to one with only a few hundred parts per million of CO2 and just under 1 part per million of CH4. Those changes to our atmosphere have been no accident; over geological time, life and its metabolic processes have evolved (such as the evolution of photosynthetic bacteria that consume CO2) and changed the atmosphere to conditions that remained cool enough to be habitable.

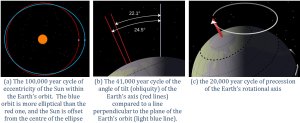

The position of the Earth relative to the Sun is another important component of natural climate forcing. Earth’s orbit around the Sun is nearly circular, but like all physical systems, it has natural oscillations. First, the shape of the orbit changes on a regular time scale (close to 100,000 years) from being close to circular to being very slightly elliptical. But the circularity of the orbit is not what matters; it is the fact that as the orbit becomes more elliptical, the position of the Sun within that ellipse becomes less central or more eccentric (Figure 6.5.1a). Eccentricity is important because when it is high, the Earth-Sun distance varies more from season to season than it does when eccentricity is low.

Second, Earth rotates around an axis through the North and South Poles, and that axis is at an angle to the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun (Figure 6.5.1b). The angle of tilt (also known as obliquity) varies on a time scale of 41,000 years. When the angle is at its maximum (24.5°), Earth’s seasonal differences are accentuated. When the angle is at its minimum (22.1°), seasonal differences are minimized. The current hypothesis is that glaciation is favored at low seasonal differences as summers would be cooler and snow would be less likely to melt and more likely to accumulate from year to year. Third, the direction in which Earth’s rotational axis points also varies, on a time scale of about 20,000 years (Figure 6.5.1c). This variation, known as precession, means that although the North Pole is presently pointing to the star Polaris (the pole star), in 10,000 years it will point to the star Vega. The importance of eccentricity, tilt, and precession to Earth’s climate cycles (now known as Milankovitch Cycles) was first pointed out by Yugoslavian engineer and mathematician Milutin Milankovitch in the early 1900s. Milankovitch recognized that although the variations in the orbital cycles did not affect the total amount of insolation (light energy from the Sun) that Earth received, it did affect where on Earth that energy was strongest.

Volcanic eruptions don’t just involve lava flows and exploding rock fragments; various particulates and gases are also released, the important ones being sulphur dioxide and CO2. Sulphur dioxide is an aerosol that reflects incoming solar radiation and has a net cooling effect that is short lived (a few years in most cases, as the particulates settle out of the atmosphere within a couple of years), and doesn’t typically contribute to longer-term climate change. Volcanic CO2 emissions can contribute to climate warming but only if a greater-than-average level of volcanism is sustained over a long time (at least tens of thousands of years). It is widely believed that the catastrophic end-Permian extinction (at 250 Ma) resulted from warming initiated by the eruption of the massive Siberian Traps over a period of at least a million years.

Ocean currents are important to climate, and currents also have a tendency to oscillate. Glacial ice cores show clear evidence of changes in the Gulf Stream that affected global climate on a time scale of about 1,500 years during the last glaciation. The east-west changes in sea-surface temperature and surface pressure in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO varies on a much shorter time scale of between two and seven years. These variations tend to garner the attention of the public because they have significant climate implications in many parts of the world. The strongest El Niños in recent decades were in 1983, 1998, and 2015 and those were very warm years from a global perspective. During a strong El Niño, the equatorial Pacific sea-surface temperatures are warmer than normal and heat the atmosphere above the ocean, which leads to warmer-than-average global temperatures.

Climate Feedbacks

As already stated, climate feedbacks are critically important in amplifying weak climate forcings into full-blown climate changes. Since Earth still has a very large volume of ice, mostly in the continental ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland, but also in alpine glaciers and permafrost, melting is one of the key feedback mechanisms. Melting of ice and snow leads to several different types of feedbacks, an important one being a change in albedo, or the reflectivity of a surface. Earth’s various surfaces have widely differing albedos, expressed as the percentage of light that reflects off a given material. This is important because most solar energy that hits a very reflective surface is not absorbed and therefore does little to warm Earth. Water in the oceans or on a lake is one of the darkest surfaces, reflecting less than 10% of the incident light, while clouds and snow or ice are among the brightest surfaces, reflecting 70% to 90% of the incident light. When sea ice melts, as it has done in the Arctic Ocean at a disturbing rate over the past decade, the albedo of the area affected changes dramatically, from around 80% down to less than 10%. Much more solar energy is absorbed by the water than by the pre-existing ice, and the temperature increase is amplified. The same applies to ice and snow on land, but the difference in albedo is not as great. When ice and snow on land melt, sea level rises. (Sea level is also rising because the oceans are warming and that increases their volume). A higher sea level means a larger proportion of the planet is covered with water, and since water has a lower albedo than land, more heat is absorbed and the temperature goes up a little more. Since the last glaciation, sea-level rise has been about 125 m; a huge area that used to be land is now flooded by heat-absorbent seawater. During the current period of anthropogenic climate change, sea level has risen only about 20 cm, and although that doesn’t make a big change to albedo, sea-level rise is accelerating.

Most of northern Canada, Alaska, Russia, and Scandinavia has a layer of permafrost that ranges from a few centimeters to hundreds of meters in thickness. Permafrost is a mixture of soil and ice and it also contains a significant amount of trapped organic carbon that is released as CO2 and CH4 when the permafrost breaks down. Because the amount of carbon stored in permafrost is in the same order of magnitude as the amount released by burning fossil fuels, this is a feedback mechanism that has the potential to equal or surpass the forcing that has unleashed it. In some polar regions, including northern Canada, permafrost includes methane hydrate, a highly concentrated form of CH4 trapped in solid form. Breakdown of permafrost releases this CH4. Even larger reserves of methane hydrate exist on the seafloor, and while it would take significant warming of ocean water down to a depth of hundreds of meters, this too is likely to happen in the future if we don’t limit our impact on the climate. There is strong isotopic evidence that the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum was caused, at least in part, by a massive release of sea-floor methane hydrate.

There is about 45 times as much carbon in the ocean (as dissolved bicarbonate ions, HCO3-) as there is in the atmosphere (as CO2), and there is a steady exchange of carbon between the two reservoirs (see section 5.5). But the solubility of CO2 in water decreases as the temperature goes up. In other words, the warmer it gets, the more oceanic bicarbonate that gets transferred to the atmosphere as CO2. That makes CO2 solubility another positive feedback mechanism. Vegetation growth responds positively to both increased temperatures and elevated CO2 levels, and so in general, it represents a negative feedback to climate change because the more the vegetation grows, the more CO2 is taken from the atmosphere. But it’s not quite that simple, because when trees grow bigger and more vigorously, forests become darker (they have lower albedo) so they absorb more heat. Furthermore, climate warming isn’t necessarily good for vegetation growth; some areas have become too hot, too dry, or even too wet to support the plant community that was growing there, and it might take centuries for something to replace it successfully. All of these positive (and negative) feedbacks work both ways. For example, during climate cooling, growth of glaciers leads to higher albedos, and formation of permafrost results in storage of carbon that would otherwise have returned quickly to the atmosphere.

Anthropogenic Climate Change

When we talk about anthropogenic climate change, we are generally thinking of the industrial era, which really got going when we started using fossil fuels (coal to begin with, and later oil and natural gas) to drive machinery and trains, and to generate electricity. That was around the middle of the 18th century. The issue with fossil fuels is that they involve burning carbon that was naturally stored in the crust over hundreds of millions of years as part of Earth’s process of counteracting the warming Sun.

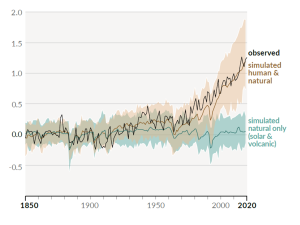

A rapidly rising population, the escalating level of industrialization and mechanization of our lives, and an increasing dependence on fossil fuels have driven the anthropogenic climate change of the past century. The trend of mean global temperatures since 1850 is shown in Figure 6.5.2. For approximately the past 55 years, the temperature has increased at a relatively steady and disturbingly rapid rate, especially compared to past changes. The average temperature now is approximately 1.1°C higher than before industrialization, and two-thirds of this warming has occurred since 1975.

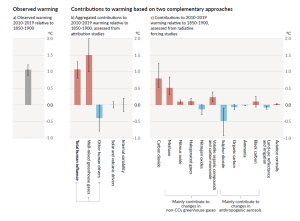

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established by the United Nations in 1988, is responsible for reviewing the scientific literature on climate change and issuing periodic reports on several topics, including the scientific basis for understanding climate change, our vulnerability to observed and predicted climate changes, and what we can do to limit climate change and minimize its impacts. Figure 6.5.3, from the sixth report of the IPCC, issued in preliminary form in 2021, shows the relative contributions of various greenhouse gases and other factors to current climate forcing, based on the changes from levels that existed in 1750.

The biggest anthropogenic contributor to warming is the emission of CO2, which accounts for 50% of positive forcing. CH4 and its atmospheric derivatives (CO2, H2O, and O3) account for 29%, and the halocarbon gases (mostly leaked from air-conditioning appliances) and nitrous oxide (N2O) (from burning fossils fuels) account for 5% each. Carbon monoxide (CO) (also produced by burning fossil fuels) accounts for 7%, and the volatile organic compounds other than methane (NMVOC) account for 3%. CO2 emissions come mostly from coal- and gas-fired power stations, motorized vehicles (cars, trucks, and aircraft), and industrial operations (e.g., smelting), and indirectly from forestry. CH4 emissions come from production of fossil fuels (escape from coal mining and from gas and oil production), livestock farming (mostly beef), landfills, and wetland rice farming. N2O and CO come mostly from the combustion of fossil fuels. In summary, close to 70% of our current greenhouse gas emissions come from fossil fuel production and use, while most of the rest comes from agriculture and landfills. Figure 6.5.4 shows the IPCC’s projections for temperature increases over the next 100 years as a result of these increasing greenhouse gases.

Impacts of Climate Change

We’ve all experienced the effects of climate change over the past decade. However, it’s not straightforward for climatologists to make the connection between a warming climate and specific weather events, and most are justifiably reluctant to ascribe any specific event to climate change. In this respect, the best measures of climate change are those that we can detect over several decades, such as the temperature changes shown in Figure 6.5.2, or the sea level rise shown in Figure 6.5.5. As already stated, sea level has risen approximately 20 cm since 1750, and that rise is attributed to both warming (and therefore expanding) seawater and melting glaciers and other land-based snow and ice (melting of sea ice does not contribute directly to sea level rise as it is already floating in the ocean).

Projections for sea level rise to the end of this century vary widely. This is in large part because we do not know which of the above climate change scenarios (Figure 6.5.4) we will most closely follow, but many are in the range from 0.5 m to 2.0 m. One of the problems in predicting sea level rise is that we do not have a strong understanding of how large ice sheets, such as Greenland and Antarctica, will respond to future warming. Another issue is that the oceans don’t respond immediately to warming. For example, with the current amount of warming, we are already committed to a future sea level rise of between 1.3 m and 1.9 m, even if we could stop climate change today. This is because it takes decades to centuries for the existing warming of the atmosphere to be transmitted to depth within the oceans and to exert its full impact on large glaciers. Most of that committed rise would take place over the next century, but some would be delayed longer. And for every decade that the current rates of climate change continue, that number increases by another 0.3 m. In other words, if we don’t make changes quickly, by the end of this century we’ll be locked into 3 m of future sea level rise. In a 2008 report, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated that by 2070 approximately 150 million people living in coastal areas could be at risk of flooding due to the combined effects of sea level rise, increased storm intensity, and land subsidence. The assets at risk (buildings, roads, bridges, ports, etc.) are in the order of $35 trillion ($35,000,000,000,000). Countries with the greatest exposure of population to flooding are China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, U.S.A., Japan, and Thailand. Some of the major cities at risk include Shanghai, Guangzhou, Mumbai, Kolkata, Dhaka, Ho Chi Minh City, Tokyo, Miami, and New York.

One of the other risks for coastal populations, besides sea level rise, is that climate warming is also associated with an increase in the intensity of tropical storms (e.g., hurricanes or typhoons; see section 6.4), which almost always bring serious flooding from intense rain and storm surges. Some recent examples are New Orleans in 2005 with Hurricane Katrina, and New Jersey and New York in 2012 with Hurricane Sandy. Tropical storms get their energy from the evaporation of warm seawater in tropical regions. In the Atlantic Ocean, this takes place between 8° and 20° N in the summer. Figure 6.5.6 shows the variations in the sea-surface temperature (SST) of the tropical Atlantic Ocean (in blue) versus the amount of power represented by Atlantic hurricanes between 1950 and 2008 (in red). Not only has the overall intensity of Atlantic hurricanes increased with the warming since 1975, but the correlation between hurricanes and sea-surface temperatures is very strong over that time period.

The geographical ranges of diseases and pests, especially those caused or transmitted by insects, have been shown to extend toward temperate regions because of climate change. West Nile virus and Lyme disease are two examples that already directly affect North Americans, while dengue fever could be an issue in the future (dengue became a "nationally notifiable condition" in the United States in 2010). For several weeks in July and August of 2010, a massive heat wave affected western Russia, especially the area southeast of Moscow, and scientists have stated that climate change was a contributing factor. Temperatures soared to over 40°C, as much as 12°C above normal over a wide area, and wildfires raged in many parts of the country. Over 55,000 deaths are attributed to the heat and to respiratory problems associated with the fires. A summary of the impacts of climate change on natural disasters is given in Figure 6.5.7. The major types of disasters related to climate are floods and storms, but the health implications of extreme temperatures are also becoming a great concern. In the decade 1971 to 1980, extreme temperatures were the fifth most common natural disasters; by 2001 to 2010, they were the third most common.

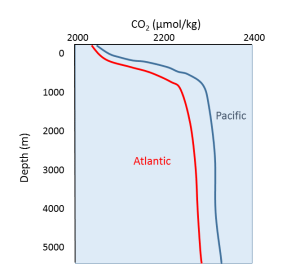

Oxygen and carbon dioxide are involved in the same biological processes in the ocean, but in opposite ways; photosynthesis consumes CO2 and produces O2, while respiration and decomposition consume O2 and produce CO2. Therefore it should not be surprising that oceanic CO2 profiles are essentially the opposite of dissolved oxygen profiles (Figure 5.5.1). At the surface, photosynthesis consumes CO2 so CO2 levels remain relatively low. In addition, organisms that utilize carbonate in their shells are common near the surface, further reducing the amount of dissolved CO2.

In deeper water, CO2 concentration increases as respiration exceeds photosynthesis, and decomposition of organic matter adds additional CO2 to the water. As with oxygen, there is often more CO2 at depth because cold bottom water holds more dissolved gases, and high pressures increase solubility. Deep water in the Pacific contains more CO2 than the Atlantic as the Pacific water is older and has accumulated more CO2 from the respiration of benthic organisms.

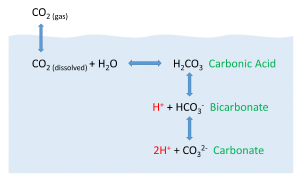

But the behavior of carbon dioxide in the ocean is more complex than the figure above would suggest. When CO2 gas dissolves in the ocean, it interacts with the water to produce a number of different compounds according to the reaction below:

CO2 + H2O ↔ H2CO3 ↔ H+ + HCO3- ↔ 2H+ + CO32-

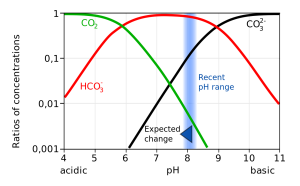

CO2 reacts with water to produce carbonic acid (H2CO3), which then dissociates into bicarbonate (HCO3-) and hydrogen ions (H+). The bicarbonate ions can further dissociate into carbonate (CO32-) and additional hydrogen ions (Figure 5.5.2).

Most of the CO2 dissolving or produced in the ocean is quickly converted to bicarbonate. Bicarbonate accounts for about 92% of the CO2 dissolved in the ocean, and carbonate represents around 7%, so only about 1% remains as CO2, and little gets absorbed back into the air. The rapid conversion of CO2 into other forms prevents it from reaching equilibrium with the atmosphere, and in this way, water can hold 50-60 times as much CO2 and its derivatives as the air.

CO2 and pH

The equation above also illustrates carbon dioxide's role as a buffer, regulating the pH of the ocean. Recall that pH reflects the acidity or basicity of a solution. The pH scale runs from 0-14, with 0 indicating a very strong acid, and 14 representing highly basic conditions. A solution with a pH of 7 is considered neutral, as is the case for pure water. The pH value is calculated as the negative logarithm of the hydrogen ion concentration according to the equation:

pH = -log10[H+]

Therefore, a high concentration of H+ ions leads to a low pH and acidic condition, while a low H+ concentration indicates a high pH and basic conditions. It should also be noted that pH is described on a logarithmic scale, so every one point change on the pH scale actually represents an order of magnitude (10 x) change in solution strength. So a pH of 6 is 10 times more acidic than a pH of 7, and a pH of 5 is 100 times (10 x 10) more acidic than a pH of 7.

Carbon dioxide and the other carbon compounds listed above play an important role in buffering the pH of the ocean. Currently, the average pH for the global ocean is about 8.1, meaning seawater is slightly basic. Because most of the inorganic carbon dissolved in the ocean exists in the form of bicarbonate, bicarbonate can respond to disturbances in pH by releasing or incorporating hydrogen ions into the various carbon compounds. If pH rises (low [H+]), bicarbonate may dissociate into carbonate, and release more H+ ions, thus lowering pH. Conversely, if pH gets too low (high [H+]), bicarbonate and carbonate may incorporate some of those H+ ions and produce bicarbonate, carbonic acid, or CO2 to remove H+ ions and raise the pH. By shuttling H+ ions back and forth between the various compounds in this equation, the pH of the ocean is regulated and conditions remain favorable for life.

CO2 and Ocean Acidification

In recent years there has been rising concern about the phenomenon of ocean acidification. As described in the processes above, the addition of CO2 to seawater lowers the pH of the water. As anthropogenic sources of atmospheric CO2 have increased since the Industrial Revolution, the oceans have been absorbing an increasing amount of CO2, and researchers have documented a decline in ocean pH from about 8.2 to 8.1 in the last century. This may not appear to be much of a change, but remember that since pH is on a logarithmic scale, this decline represents a 30% increase in acidity. It should be noted that even at a pH of 8.1 the ocean is not actually acidic; the term "acidification" refers to the fact that the pH is becoming lower, i.e. the water is moving towards more acidic conditions.

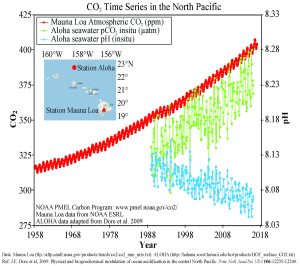

Figure 5.5.3 presents data from observation stations in and around the Hawaiian Islands. As atmospheric levels of CO2 have increased, the CO2 content of the ocean water has also increased, leading to a reduction in seawater pH. Some models suggest that at the current rate of CO2 addition to the atmosphere, by 2100 ocean pH may be further reduced to around 7.8, which would represent more than a 120% increase in ocean acidity since the Industrial Revolution.

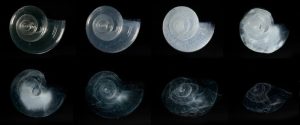

Why is this important? Declining pH can impact many biological systems. Of particular concern are organisms that secrete calcium carbonate shells or skeletons, such as corals, shellfish, and may planktonic organisms. At lower pH levels, calcium carbonate dissolves, eroding the shells and skeletons of these organisms (Figure 5.5.4).

Not only does a declining pH lead to increased rates of dissolution of calcium carbonate, it also diminishes the amount of free carbonate ions in the water. The relative proportions of the different carbon compounds in seawater is dependent on pH (Figure 5.5.6). As pH declines, the amount of carbonate declines, so there is less available for organisms to incorporate into their shells and skeletons. So ocean acidification both dissolves existing shells and makes it harder for shell formation to occur.

Additional links for more information:

- NOAA Ocean Acidification Program website http://oceanacidification.noaa.gov/

Most ocean waves are generated by wind. Wind blowing across the water's surface creates little disturbances called capillary waves, or ripples that start from gentle breezes (Figure 3.2.1). Capillary waves have a rounded crest with a V-shaped trough, and wavelengths less than 1.7 cm. These small ripples give the wind something to "grip" onto to generate larger waves when the wind energy increases, and once the wavelength exceeds 1.7 cm the wave transitions from a capillary wave to a wind wave. As waves are produced, they are opposed by a restoring force that attempts to return the water to its calm, equilibrium condition. The restoring force of the small capillary waves is surface tension, but for larger wind-generated waves gravity becomes the restoring force.

As the energy of the wind increases, so does the size, length and speed of the resulting waves. There are three important factors determining how much energy is transferred from wind to waves, and thus how large the waves will get:

- Wind speed.

- The duration of the wind, or how long the wind blows continuously over the water.

- The distance over which the wind blows across the water in the same direction, also known as the fetch.

Increasing any of these factors increases the energy of wind waves, and therefore their size and speed. But there is an upper limit to how large wind-generated waves can get. As wind energy increases, the waves receive more energy and they get both larger and steeper (recall from section 3.1 that wave steepness = height/wavelength). When the wave height exceeds 1/7 of the wavelength, the wave becomes unstable and collapses, forming whitecaps.

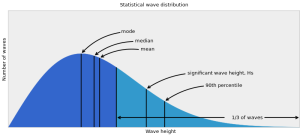

The ocean surface represents an irregular mixture of hundreds of waves of different speeds and sizes, all coming from different directions and interacting with each other. A histogram of wave heights within this mixture reveals a bell-shaped curve (Figure 3.2.2). In addition to basic statistics such as mode (most probable), median and mean wave height, wave heights are also reported in other ways. Marine weather forecasts and ship and buoy data often report significant wave height (Hs), which is the mean height of the largest one-third of the waves. Mean wave height is approximately equal to two-thirds of the significant wave height. Finally, there is the minimum height of the highest 10% of waves (the 90th percentile of wave heights), often expressed as H1/10.

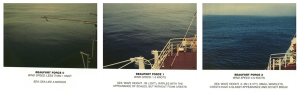

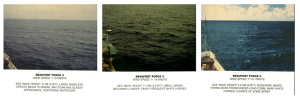

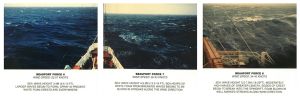

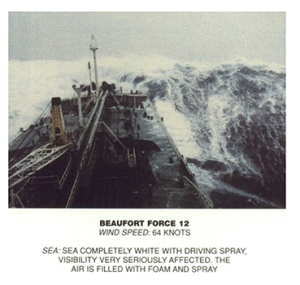

Under strong wind conditions, the ocean surface becomes a chaotic mixture of choppy, whitecapped wind-generated waves. The term sea state describes the size and extent of the wind-generated waves in a particular area. When the waves are at their maximum size for the existing wind speed, duration, and fetch, it is referred to as a fully developed sea. The sea state is often reported on the Beaufort scale, ranging from 0-12, where 0 means calm, windless and waveless conditions, while Beaufort 12 is a hurricane (see box below).

The Beaufort Scale

The Beaufort scale is used to describe the wind and sea state conditions on the ocean. It is an observational scale based on the judgement of the observer, rather than one dictated by accurate measurements of wave height. Beaufort 0 represents calm, flat conditions, while Beaufort 12 represents a hurricane.

(Images by United States National Weather Service (http://www.crh.noaa.gov/mkx/marinefcst.php) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons).

A fully developed sea often occurs under stormy conditions, where high winds create a chaotic, random pattern of waves and whitecaps of varying sizes. The waves will propagate outwards from the center of the storm, powered by the strong winds. However, as the storm subsides and the winds weaken, these irregular seas will sort themselves out into more ordered patterns. Recall that open ocean waves will usually be deep water waves, and their speed will depend on their wavelength (section 3.1). As the waves move away from the storm center, they sort themselves out based on speed, with longer wavelength waves traveling faster than shorter wavelength waves. This means that eventually all of the waves in a particular area will be traveling with the same wavelength, creating regular, long period waves called swell (Figure 3.2.3). We experience swell as the slow up and down or rocking motion we feel on a boat, or with the regular arrival of waves on shore. Swell can travel very long distances without losing much energy, so we can observe large swells arriving at the shore even where there is no local wind; the waves were produced by a storm far offshore, and were sorted into swell as they traveled towards the coast.

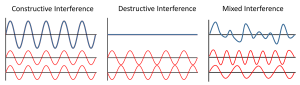

Because swell travels such long distances, eventually swells coming from different directions will run into each other, and when they do they create interference patterns. The interference pattern is created by adding the features of the waves together, and the type of interference that is created depends on how the waves interact with each other (Figure 3.2.4). Constructive interference occurs when the two waves are completely in phase; the crest of one wave lines up exactly with the crest of the other wave, as do the troughs of the two waves. Adding the two crest together creates a crest that is higher than in either of the source waves, and adding the troughs creates a deeper trough than in the original waves. The result of constructive interference is therefore to create waves that are larger than the original source waves. In destructive interference, the waves interact completely out of phase, where the crest of one wave aligns with the trough of the other wave. In this case, the crest and the trough work to cancel each other out, creating a wave that is smaller than either of the source waves. In reality, it is rare to find perfect constructive or destructive interference as displayed in Figure 3.2.4. Most interference by swells at sea is mixed interference, which contains a mix of both constructive and destructive interference. The interacting swells do not have the same wavelength, so some points show constructive interference, and some points show destructive interference, to varying degrees. This results in an irregular pattern of both small and large waves, called surf beat.

It is important to point out that these interference patterns are only temporary disturbances, and do not affect the properties of the source waves. Moving swells interact and create interference where they meet, but each wave continues on unaffected after the swells pass each other.

About half of the waves in the open sea are less than 2 m high, and only 10-15% exceed 6 m. But the ocean can produce some extremely large waves. The largest wind wave reliably measured at sea occurred in the Pacific Ocean in 1935, and was measured by the navy tanker the USS Ramapo. Its crew measured a wave of 34 m or about 112 ft high! Occasionally constructive interference will produce waves that are exceptionally large, even when all of the surrounding waves are of normal height. These random, large waves are called rogue waves (Figure 3.2.5). A rogue wave is usually defined as a wave that is at least twice the size of the significant wave height, which is the average height of the highest one-third of waves in the region. It is not uncommon for rogue waves to reach heights of 20 m or more.

Figure 3.2.5 A rogue wave in the Bay of Biscay, off of the French coast, ca. 1940 (NOAA, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons).

Rogue waves are particularly common off of the southeast coast of South Africa, a region referred to as the "wild coast." Here, Antarctic storm waves move north into the oncoming Agulhas Current, and the wave energy gets focused over a narrow area, leading to constructive interference. This area may be responsible for sinking more ships than anywhere else on Earth. On average about 100 ships are lost every year across the globe, and many of these losses are probably due to rogue waves.

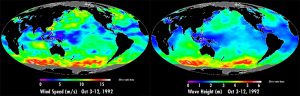

Waves in the Southern Ocean are generally fairly large (the red areas in Figure 3.2.6) because of the strong winds and the lack of landmasses, which provide the winds with a very long fetch, allowing them to blow unimpeded over the ocean for very long distances. These latitudes have been termed the “Roaring Forties”, “Furious Fifties”, and “Screaming Sixties” due to the high winds.

Tsunamis loom large in popular culture, but there are a number of misconceptions about these large waves. First, tsunamis have nothing to do with the tides, so it is a misnomer to refer to them as "tidal waves." There are actual tidal waves (see section 3.5), but they are not related to tsunamis. Second, the giant, curling wave that is taller than skyscrapers and destroys cities in science fiction movies is also a fabrication, as tsunamis do not behave that way, as described below.

Tsunamis are large waves that are usually the result of seismic activity, such as the rising or falling of the seafloor due to earthquakes, although volcanic activity and landslides can also cause tsunamis in the form of splash waves (see section 3.1). As the seafloor rises or falls, so does the water column above it, creating waves. Only vertical seismic disturbances cause tsunamis, not horizontal movements. These vertical seafloor movements are usually less than 10 m high, so the resulting wave will be of an equal or lesser height at sea. While the tsunamis have a relatively small height at the point of origin, they have very long wavelengths (100-200 km). Because of the long wavelength, they behave as shallow water waves throughout the entire ocean; the depth of the ocean is always shallower than half of their wavelength. As shallow water waves, their speed depends on water depth, but they can still travel at speeds over 750 km/hr (Figure 3.4.1)!

When tsunamis approach land, they behave just like any other wave; as the depth becomes shallower, the waves slow down and the wave height begins to increase. However, contrary to popular belief, tsunamis do not arrive on shore as giant, cresting waves. Since their wavelength is so long, it is impossible for their height to ever exceed 1/7 of their wavelength, so the waves don’t actually curl or break. Instead, they usually hit the shore as sudden surges of water causing a very rapid increase in sea level, like that of an enormous rise in tide. It may take several minutes for the wave to pass, during which time sea level can rise to 40 m higher than usual.

Large tsunamis occur every 2-3 years, with very large, damaging events happening every 15-20 years. The most devastating tsunami in terms of loss of life resulted from a magnitude 9 earthquake in Indonesia in 2004 (Figure 3.4.2), which created waves up to 33 m tall and left about 230,000 people dead in Indonesia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka. In 2011 a 9.0 magnitude earthquake in Japan triggered a tsunami up to 40.5 m high, which resulted in over 18,000 deaths. This earthquake also caused the Fukishima nuclear accident, and moved Japan about 8 inches closer to the U.S.

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

Radiant energy from the sun is important for several major oceanic processes:

- Climate, winds, and major ocean currents are ultimately dependent on solar radiation reaching the Earth and heating different areas to different degrees.

- Sunlight warms the surface water where much oceanic life lives.

- Solar radiation provides light for photosynthesis, which supports the entire ocean ecosystem.

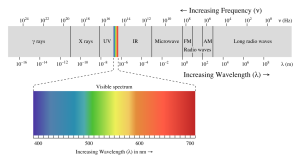

The energy reaching Earth from the sun is a form of electromagnetic radiation, which is represented by the electromagnetic spectrum (Figure 5.9.1). Electromagnetic waves vary in their frequency and wavelength. High frequency waves have very short wavelengths, and are very high energy forms of radiation, such as gamma rays and x-rays. These rays can easily penetrate the bodies of living organisms and interfere with individual atoms and molecules. At the other end of the spectrum are low energy, long wavelength waves such as radio waves, which do not pose a hazard to living organisms.

Most of the solar energy reaching the Earth is in the range of visible light, with wavelengths between about 400-700 nm. Each color of visible light has a unique wavelength, and together they make up white light. The shortest wavelengths are on the violet and ultraviolet end of the spectrum, while the longest wavelengths are at the red and infrared end. In between, the colors of the visible spectrum comprise the familiar "ROYGBIV"; red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet.

Water is very effective at absorbing incoming light, so the amount of light penetrating the ocean declines rapidly (is attenuated) with depth (Figure 5.9.2). At 1 m depth, only 45% of the solar energy that falls on the ocean surface remains. At 10 m depth only 16% of the light is still present, and only 1% of the original light is left at 100 m. No light penetrates beyond 1000 m.

In addition to overall attenuation, the oceans absorb the different wavelengths of light at different rates (Figure 5.9.2). The wavelengths at the extreme ends of the visible spectrum are attenuated faster than those wavelengths in the middle. Longer wavelengths are absorbed first; red is absorbed in the upper 10 m, orange by about 40 m, and yellow disappears before 100 m. Shorter wavelengths penetrate further, with blue and green light reaching the deepest depths.

This explains why everything appears blue under water. The colors we perceive depends on the wavelengths of light that are received by our eyes. If an object appears red to us, that is because the object reflects red light but absorbs all of the other colors. So the only color reaching our eyes is red. Under water, blue is the only color of light still available at depth, so that is the only color that can be reflected back to our eyes, and everything has a blue tinge under water. A red object at depth will not appear red to us because there is no red light available to reflect off of the object. Objects in water will only appear as their real colors near the surface where all wavelengths of light are still available, or if the other wavelengths of light are provided artificially, such as by illuminating the object with a dive light.

Water in the open ocean appears clear and blue because it contains much less particulate matter, such as phytoplankton or other suspended particles, and the clearer the water, the deeper the light penetration. Blue light penetrates deeply and is scattered by the water molecules, while all other colors are absorbed; thus the water appears blue. On the other hand, coastal water often appears greenish (Figure 5.9.2). Coastal water contains much more suspended silt and algae and microscopic organisms than the open ocean. Many of these organisms, such as phytoplankton, absorb light in the blue and red range through their photosynthetic pigments, leaving green as the dominant wavelength of reflected light. Therefore the higher the phytoplankton concentration in water, the greener it appears. Small silt particles may also absorb blue light, further shifting the color of water away from blue when there are high concentrations of suspended particles.

The ocean can be divided into depth layers depending on the amount of light penetration, as discussed in section 1.3 (Figure 5.9.3). The upper 200 m is referred to as the photic or euphotic zone. This represents the region where enough light can penetrate to support photosynthesis, and it corresponds to the epipelagic zone. From 200-1000 m lies the dysphotic zone, or the twilight zone (corresponding with the mesopelagic zone). There is still some light at these depths, but not enough to support photosynthesis. Below 1000 m is the aphotic (or midnight) zone, where no light penetrates. This region includes the majority of the ocean volume, which exists in complete darkness.

Written by Dr. Cristina Cardona.