By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

10 2.4 Plates and Plate Motions

The idea of plate tectonics became widely accepted around 1965 as more and more geologists started thinking in these terms. By the end of 1967, Earth’s surface had been mapped into a series of plates (Figure 2.4.1). The major plates are Eurasia, Pacific, India, Australia, North America, South America, Africa, and Antarctic. There are also numerous small plates (e.g., Juan de Fuca, Nazca, Scotia, Philippine, Caribbean), and many very small plates or sub-plates. For example the Juan de Fuca Plate is actually three separate plates (Gorda, Juan de Fuca, and Explorer) that all move in the same general direction but at slightly different rates.

The fact that the plates include both crustal material and lithospheric mantle material makes it possible for a single plate to be made up of both oceanic and continental crust. For example, the North American Plate includes most of North America, plus half of the northern Atlantic Ocean. Similarly the South American Plate extends across the western part of the southern Atlantic Ocean, while the European and African plates each include part of the eastern Atlantic Ocean. The Pacific Plate is almost entirely oceanic, but it does include the part of California west of the San Andreas Fault.

Rates of motions of the major plates range from less than 1 cm/year to over 10 cm/year (for comparison, human fingernails grow at around 6 cm/year). The Pacific Plate is the fastest at over 10 cm/year in some areas, followed by the Australian and Nazca Plates. The North American Plate is one of the slowest, averaging around 1 cm/year in the south up to almost 4 cm/year in the north. Plates move as rigid bodies, so it may seem surprising that the North American Plate can be moving at different rates in different places. The explanation is that plates move in a rotational manner. The North American Plate, for example, rotates counter-clockwise; the Eurasian Plate rotates clockwise.

As originally described by Wegener in 1915, the present continents were once all part of the supercontinent Pangaea. More recent studies of continental match-ups and the magnetic ages of ocean-floor rocks have enabled us to reconstruct the history of the break-up of Pangaea.

Pangaea began to rift apart along a line between Africa and Asia and between North America and South America at around 200 Ma (Figure 2.4.2). During the same period, the Atlantic Ocean began to open up between northern Africa and North America, and India broke away from Antarctica. At this stage, Pangaea was divided into Laurasia (now Europe, Asia and North America) and Gondwanaland (the southern continents; South America, Africa, India, Australia, and Antarctica). Between 200 and 150 Ma, rifting started between South America and Africa and between North America and Europe, and India separated from Antarctica and moved north toward Asia. By 80 Ma, Africa had separated from South America, and most of Europe had separated from North America. By 50 Ma, Australia had separated from Antarctica, and shortly after that, India collided with Asia.

Over the next 50 million years, it is likely that there will be full development of the east African rift and creation of new ocean floor. Eventually Africa will split apart. There will also be continued northerly movement of Australia and Indonesia. The western part of California (including Los Angeles and part of San Francisco) will split away from the rest of North America, and eventually sail right by the west coast of Vancouver Island, en route to Alaska. Because the oceanic crust formed by spreading on the mid-Atlantic ridge is not currently being subducted (except in the Caribbean), the Atlantic Ocean is slowly getting bigger, and the Pacific Ocean is getting smaller. If this continues without changing for another couple hundred million years, we will be back to where we started, with one supercontinent.

Pangaea, which existed from about 350 to 200 Ma, was not the first supercontinent. In 1966, Tuzo Wilson proposed that there has been a continuous series of cycles of continental rifting and collision; that is, break-up of supercontinents, drifting, collision, and formation of other supercontinents. Pangaea was preceded by Pannotia (600 to 540 Ma), by Rodinia (1,100 to 750 Ma), and by other supercontinents before that.

With all of these plates constantly on the move, they inevitably end up interacting with each other at their plate boundaries. Plates can interact in three ways: they can move apart (divergent boundary), they can move towards each other (convergent boundary), or they can slide past each other (transform boundary). The following sections will examine each of these types of plate boundaries, and the geological features they create.

Additional links for more information:

- An interactive animation of plate motion over the past 550 million years: http://barabus.tru.ca/geol1031/plates.html

For most people, when they think of coastal areas they picture a beach, and the beach that they imagine is probably a typical sandy beach composed of quartz sand grains. But beaches are comprised of whatever types of sediments are dominant in the local area. For example, parts of Hawaii and Iceland are famous for their black sand beaches, made up of eroded basalt and other volcanic materials. The beautiful tropical white sand beaches we see in travel ads are largely composed of the crushed calcium carbonate remains of coral skeletons (much of which has been chewed up and excreted by a fish before we happily run our toes through it!) Other beaches may lack sand altogether and instead be dominated by small shells, or larger rocks or pebbles (Figure 4.1.1).

The shoreline is divided up into multiple zones (Figure 4.1.2). The backshore is the region of the beach above the high tide line, which is only submerged under unusually high wave conditions, such as during storms. The foreshore lies between the high tide and low tide lines; it is submerged during high tide and is exposed during low tide. The nearshore extends from the low tide line to the depth where wave action is no longer influenced by the bottom, i.e. to where the depth exceeds the wave base (section 3.1). Finally, the offshore zone represents the depths beyond the nearshore region.

Along the beach itself, the area above the high tide line is called the berm, which is usually dry and relatively flat. The berm often ends with a berm crest or berm scarp, which is a steeper wall carved out by wave action that leads down to the foreshore. The foreshore has a number of other names, including the beach face, the intertidal or littoral zone, and if the area is fairly flat, the low tide terrace. Just off shore from the beach there are often longshore bars and longshore troughs running parallel to the beach. The longshore bars are accumulations of sand that are deposited by wave action and longshore currents (section 4.2). The decrease in depth above longshore bars is what often causes waves to start to break well before reaching the beach (section 3.3).

The sand or other particles that make up the beach are distributed by wave action. The water that moves over a beach through incoming waves is called swash, and it also contains suspended sand grains that can get deposited on the beach. Some of the swash percolates into the sand while the rest of the water washes back out as backwash as the wave recedes. Backwash removes sand from the beach and returns it to the ocean. Sand will therefore be deposited or eroded depending on which process is dominant. If wave action is light, a lot of incoming water gets absorbed by the sand, so swash dominates. Under heavier waves the beach becomes saturated with water, so less can be absorbed, and backwash is dominant. This leads to seasonal cycles in beach structure; waves are heavier during the winter as a result of stormier conditions at sea, so backwash dominates and sand is removed from the beach and deposited offshore in longshore bars. In the summer the waves are gentler, swash dominates, and the sand is transported from the longshore bar and deposited on the shore to create a wider, sandy beach (Figure 4.1.3).

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

In addition to fish, the ocean is also home to a variety of birds. These birds are referred to as seabirds because they spend a considerable amount of time around the sea. Many seabirds spend their entire lives in the ocean, only coming to land to reproduce. Some seabirds dive and swim below the surface, such as penguins, whose wings are modified into flippers, or cormorants, whose webbed feet act as paddles. Others stay at the surface, only hunting in the uppermost meter of the water (Keddy). Please go to this website to read more about seabirds: https://ca.audubon.org/what-s-seabird

Birds evolved from reptilian ancestors

Birds split from the main reptile branch about 150 million years ago with an intermediate form known as Archaeopteryx, which was about the size of a crow. They have reptilian characteristics, such as their feet and lower legs are covered with scales and terminate in claws, their reproductive physiology is basically reptilian (laying eggs), their feathers are believed to have been derived from scales, and have many other developmental and structural similarities with reptiles. Yet, unlike reptiles, birds are warm-blooded (endothermic) and maintain a constant internal body temperature.

Marine birds

Marine birds tend to be larger and stronger than their land counterparts. They have a lightweight, low-density body structure with hollow bones. Their wings are long, pointed and cupped underneath to support a large and muscular organism aloft for long periods of time.

They do not drink freshwater. Instead, they have salt glands over their eyes that remove the salt, thus permitting them to drink seawater, freeing them from dependence on freshwater from the land. The salty fluid is expelled through their bills.

The albatross

- This is one of the largest of the oceanic birds, with a wingspan of up to 12 feet

- They are the best gliders in the world – may remain aloft for months at a time, taking advantage of the west wind drift (winds that blow completely around Antarctica)

Pelicans

- This prehistoric-looking bird feeds by diving on its prey and entrapping it in its large gular pouch

- It has air sacs in its shoulders that absorb the impact with the water

Arctic Terns

- This bird feeds on small fish swimming near the surface that it catches by diving. It may even swim below the surface after them

- It lives at high latitudes and breeds on all far north rocky coasts

- However, it dislikes cold weather, so makes the longest migration of any animal, 15,000 miles each way

Penguins

- Penguins are found only in the southern hemisphere

- They are flightless birds that "fly" through the water after fish, squid and krill

- They slow their heart rate

- Have subcutaneous fat layers for insulation

- Have heavy plumage for insulation

- Their bodies are streamlined

- They have heavy feet for paddling and kicking against the water

- Their blood is shunted to the heart and brain and the extremities are deprived of blood, in order to slow heat loss

- These apply to most diving birds

Emperor Penguin: These are the largest diving birds in the world, up to 4 ft in height

- They're the best bird divers in the world, can routinely dive for 5-10 minutes (most bird dives last 30 seconds to a minute) and at best can stay down for 15-18 minutes, diving to over 1000 feet

- They eat small fish and krill – penguin populations have increased as a result of the killing off of the great whales – more krill is available as food for penguins

Penguin Adaptations

- They fluff their feathers to create trapped air in a dead space

- They have long feathers

- They rock back and forth on their heels on the ice to limit the area in contact with the ice and slow heat loss

- They can reduce blood flow to and heat loss from their wings and feet

- They exhibit "huddle" behavior – gathering in large groups and constantly changing position so that each gets a turn in the center, where it's warmest

The first paragraph, by Keddy (University of California, Davis), is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts. Download this book for free at https://geo.libretexts.org/Courses/Diablo_Valley_College/OCEAN-101%3A_Fundamentals_of_Oceanography_(Keddy)

The rest was written by Dr. Cristina Cardona.

The Equilibrium Theory of tides predicts that each day there will be two high and two low tides, each one occurring at the same time day after day, with each pair producing tides of similar heights. While this view provides a basic explanation for the primary forces that generate the tides, it does not take into account such variables as the effects of the continents, the depth of the water, and many other factors. In all, there are almost 400 variables that must be incorporated into predicting the tides! The Dynamic Theory of tides takes these other factors into account, and shows that the tides are much more complicated and variable from place to place than the Equilibrium Theory would suggest. For example, some areas receive only one high and one low tide per day (see section 3.7). Furthermore, the tidal range varies greatly across the globe; in the Mediterranean Sea, there can be a difference of only 10 cm between high and low tides, while the Bay of Fundy in Canada experiences a tidal range of up to 17m (56 ft) every day (Figure 3.6.1).

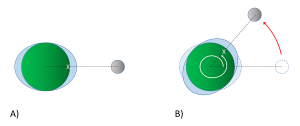

Examination of any tide chart will show that the tides don’t occur at same time each day; in fact, each tidal peak occurs about 50 minutes later than it did in the previous day. This is due to the orbit of the moon around the Earth. Imagine a high tide that occurs at a particular location (X) at 1:00 pm (Figure 3.6.2). The high tide occurs as location X moves through the bulge of water facing the moon. It will take the Earth 24 hours to complete one revolution, to bring location X back to site of the water bulge that caused that high tide. However, during those 24 hours, the moon has also moved as it orbits the Earth, so the high tide bulge has moved beyond its original location. The Earth thus has to rotate an additional distance for location X to reach the bulge and experience that same high tide. Because it takes the moon about 28 days to orbit the Earth, the moon gets "ahead" of the Earth's rotation by about 50 minutes per day. Therefore, it takes location X 24 hours and 50 minutes to rotate through the same tidal bulge, and as a result, the tidal peaks occur about 50 minutes later each day. In our example, an afternoon high tide at 1:00 pm on one day would be followed by a high tide at about 1:50 pm the following day. This 24 hour and 50 minute cycle is referred to as a tidal day.

The motion of the moon impacts the tidal cycles in other ways. As the moon orbits the Earth, its orbital plane is at an angle relative to the rotational plane of Earth. This angle, or declination, means than the moon fluctuates between an angle of 28.5o north of the equator, to 28.5o south of the equator roughly every two weeks (the cycle from maximum to minimum and back takes about 27 days). Figure 3.6.3 illustrates a case where the moon is at its maximum declination 28.5o north of the equator, creating its corresponding tidal maxima. A point on the Earth at the latitude indicated by the red line would experience two high tides as it rotated through 24 hours, at points A and B. But the two high tides would not be of equal heights; the high tide at A would be higher than the high tide at B. This helps create a mixed semi-diurnal tide; two high tides of different heights per day (see section 3.7).

Finally, the continents and the bottom topography of the oceans have an impact on the tides that are experienced in an area. Because the tides are essentially waves with extremely long wavelengths extending halfway across the Earth, they behave as shallow water waves, and they are influenced and refracted by the bottom contours, leading to regional tidal variations. When the tidal crests encounter land, they are are reflected, and the wave moves back out to sea, theoretically until it encounters another continent on the opposite side of the ocean basin. The crest is once again reflected, and the water oscillates back and forth as a standing wave across the ocean basin. However, because of the scale over which these tidal waves move, we must take into account the influence of the Coriolis Effect. As the tidal crest is reflected back across the ocean basin, its path is deflected by the Coriolis force; to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. Using the Northern Hemisphere as an example, imagine a tidal crest that has reached land on the western side of an ocean basin. It would have a tendency to be reflected and move across the basin towards the east. But the Coriolis force deflects the movement to the right, causing the crest to instead head south. When the crest hits land in the south, it would now tend to reflect towards the north, but once again the Coriolis deflection to the right kicks in, and the wave instead moves to the east. From the east the reflected wave is deflected to the north, and so on. The result of all of this is that instead of a simple standing wave moving back and forth across the ocean, the tidal crest follows a circular pattern around the ocean basin, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. This is analogous to shaking a pan full of water in a circular manner, and watching the water follow a similar circular path as it sloshes around inside. This large scale circular rotation pattern of tides is called amphidromic circulation (Figure 3.6.4). The rotation occurs around a central amphidromic point or node, that shows little tidal variation, while the largest tidal ranges occur on the edges of the circulation pattern. In Figure 3.6.4 the amphidromic points are indicated by the dark blue areas where the white lines converge, like spokes from a bicycle wheel, and the dark red and brown areas show the regions of maximum tidal heights. The tidal maxima will rotate around the amphidromic points, taking about 12 hours for a complete rotation, leading to two high and two low tides per day in many places. If a tidal maximum is occurring along one of the white lines in Figure 3.6.4 at a certain time in the Northern Hemisphere, one hour later that high tide will have moved to the white line to the left (counterclockwise), and so on until it completes a rotation. In the Southern Hemisphere, the tide will move to the line to the right for clockwise rotation.

The result of all of these variables is that the tides will not always occur twice each day, at the same time and with equal heights as the Equilibrium Theory of tides may suggest. Instead, each region of the oceans has a unique set of factors that contribute to the types of tides it will experience. The major types of tides are discussed in the next section.

By Paul Webb, used under a CC-BY 4.0 international license. Download this book for free at https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/front-matter/preface/

Marine Reptiles

Marine reptiles are cold blooded (ectothermic), meaning that their internal temperature is regulated by their surroundings and is not constant. They have scales that cover their bodies, they reproduce out of the water, and they evolved from amphibians. Today's marine reptiles include turtles, sea snakes, iguanas, and marine crocodiles.

Sea Turtles:

- 5 widely distributed tropical and subtropical species:

- Green, Hawksbill, Ridley, Leatherback and Loggerback

- All have large limbs and non-retractable heads

- All are excellent swimmers: the front limbs are flattened to act as oars, while the hind limbs work as rudders

- All grow to considerable size: the Atlantic Leatherback is the largest, growing to more than 1500 lbs and 11.5 ft long

- All are under threat of extinction

- The Green turtle is known for its long migrations, often of more than a thousand miles, between its feeding grounds and breeding areas

- Some use smell and vision, wave patterns, the angle of the sun and even celestial navigation to find a beach site close to where they were hatched

- if they survived there, then their offspring is more likely to survive

- https://www.seeturtles.org/sea-turtle-facts

Sea snakes:

- There are more than 50 species, which represent the most recently evolved group of marine reptiles

- They're found primarily in the warm oceans of the Indo-Pacific, but some can be found in the Atlantic (as seen in my photo)

- They grow to lengths of 4 to 10 feet

- Their bodies are flattened for swimming

- They breathe air, but have valves on their noses and can dive for crustaceans or shellfish

- They're truly marine except for one species that lays eggs on land – most give live birth at sea

- They also feed on small fish

- by catching and holding them in their jaws with their small teeth until their venom seeps into the wounds and kills the prey

- Their venom is among the most active of all known biological poisons

- the physiological effects are similar to those of cobra venom, only several times more toxic

- Fortunately for humans, they lack fangs to inject the venom and they are not terribly aggressive

- However, several people a year die from the bites of sea snakes, mostly fishermen who accidentally get bitten while removing them from their nets

Marine Iguanas:

- Found in the Galapagos Islands

- They're large, heavy and sluggish on land, but much more graceful in the sea

- They eat encrusting algae that they scrape from rocks with their spade-like teeth

Marine Crocodiles:

- These are occasional seafarers

- And are found mostly in the Indo-Pacific area from India to Australia

- They may grow to 30 ft in length

- They may be endangered because of predation by humans

Dr. Cristina Cardona