9.8 Meningitis

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Meningitis is an infectious inflammatory process that involves the meninges, the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. See Figure 9.21[1] for an illustration of the meninges.

![“Meninges-en.svg.png” by VG by Mysid, original by SEER Development Team [1], Jmarchn is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 Illustration showing layers of tissue from skin to brain, with text labels for major structures including Meninges](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/32/2024/03/Meninges-en.svg.png)

Pathophysiology

Inflammation is commonly caused by a bacterial or viral infection. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) are the most common infecting organisms, followed by Haemophilus influenzae and Group B streptococcus. In some cases, inflammation may be caused by a fungus or parasite. Because the infection is so close to the brain and spinal cord, it can be life-threatening because of nerve damage, swelling within the brain, and increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

Bacterial meningococcal meningitis is a medical emergency due to a high mortality rate that can occur within 24 hours. Approximately 1 in 6 people who have meningococcal meningitis die. It is a highly contagious disease that can occur in densely populated communities, such as college campuses and military barracks.[2] For this reason, the meningococcal vaccination is strongly recommended for populations at risk.

Viral meningitis is commonly caused by herpes simplex virus-2, varicella zoster, paramyxovirus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The severity of the symptoms is correlated to the type of virus. Although the virus alters brain cell function, neurological defects are usually temporary, and full recovery is gained after the inflammation resolves.[3]

Meningeal infections generally occur in two ways, through the bloodstream or by direct transmission. The infection can spread in the bloodstream from infections of other organs, such as the heart and lungs. It can also occur from direct transmission, such as traumatic injury to the facial bones, sinusitis, otitis, brain abscess, or from invasive procedures (such as lumbar puncture).[4]

Risk Factors

Risk factors for bacterial meningitis include respiratory infection, otitis media, tooth abscesses, and mastoiditis because the bacteria can cross the epithelial membrane of the brain and enter the subarachnoid space. Individuals who are immunosuppressed are also at increased risk, such as those on immunosuppressants, chemotherapy, chronic steroid therapy, or have HIV. Newborn babies are at risk from maternal infection with Group B streptococcus.[5]

Signs and Symptoms

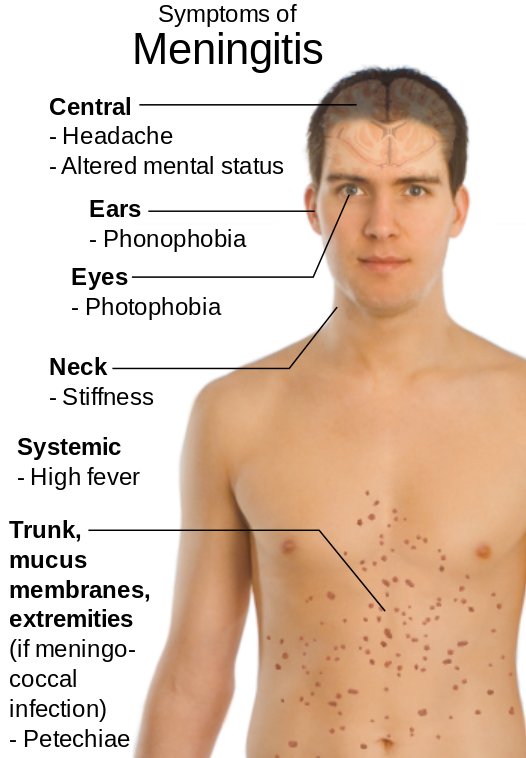

Signs and symptoms of meningitis are based on its cause. Classic symptoms of bacterial meningitis include a severe headache, rigidity of the neck, high fever, acute onset confusion, phonophobia, photophobia, nausea/vomiting, and petechiae on the trunk and extremities. Later stages include hemiparesis and hemiplegia.[6] See Figure 9.22[7] for an illustration of the signs and symptoms of meningitis.

Assessment

Clients presenting with signs and symptoms of meningitis may be assessed for Kernig and Brudzinski signs. The Brudzinski sign is when neck flexion causes the individual to automatically flex their hips and knees. The Kernig sign refers to pain that is elicited on passive extension of the client’s knees. However, these findings occur in a small percentage of clients. It is also important to consider that a high fever may not occur in older adults or those who are immunosuppressed or taking antibiotics.

View supplementary YouTube videos[8],[9] for symptoms of meningitis: Brudzinski’s Sign and Kernig’s Sign.

Other conditions can also occur due to meningitis. If inflammation spreads to the cerebral cortex, seizure activity may occur. Inflammation can also stimulate the hypothalamus to release antidiuretic hormone (ADH), resulting in hyponatremia due to increased water retention, further increasing the risk of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP).

Clients with meningitis are typically admitted to intensive care units for ICP monitoring. If left untreated, increased ICP can cause herniation of the brain, resulting in death.

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is the classic diagnostic test for meningitis. CSF testing commonly includes opening fluid pressure, white blood cell count, protein, and glucose.

Gram stains and cultures may be obtained from the throat, nose, and urine if associated infections are suspected. Blood cultures are often collected.

Blood tests include white blood cell count, liver enzymes, serum electrolytes, and HIV testing. X-rays may be performed of the chest, sinuses, and mastoids if associated infections are suspected. Clients older than 60 years, those with increased ICP, or those who are immunosuppressed may have a CT scan before a lumbar puncture is performed because of the risk of brain herniation.[10],[11]

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses focus on neurologic dysfunction and tissue perfusion caused by the infectious, inflammatory process and may include the following[12]:

- Ineffective Cerebral Tissue Perfusion related to cerebral edema

- Ineffective Airway Clearance related to neuromuscular damage

- Hyperthermia related to infection

- Acute Pain related to increased intracranial pressure

- Interrupted Family Processes related to the critical nature of the situation and uncertain prognosis

Outcome Identification

Clients who have early recognition and treatment of meningitis tend to have good prognosis. Those who present with an altered state of consciousness have high morbidity and mortality. Nurses are key in facilitating prompt medical evaluation and initiation of prescribed treatment. Therefore, outcome identification for clients with meningitis include attaining adequate cerebral tissue performance either through prevention or reduction in increased ICP, maintaining normal body temperature, protecting against injury, enhancing coping measures, restoring normal cognitive functions, and preventing complications.

Sample outcome criteria for clients with meningitis include the following:

- The client will maintain or restore motor, cognitive, and sensory function within 24 hours.

- The client will achieve a normal body temperature within 48 hours.

- The client will express relief from pain within two hours.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

One of the most important interventions aimed at avoiding life-threatening complications from bacterial meningitis is prompt administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics until results from culture and Gram’s stain testing are available. After results are reported, an appropriate anti-infective drug is prescribed to treat the specific type of meningitis. The treatment of bacterial meningitis typically requires two to three weeks of IV antibiotics.

Intravenous corticosteroids such as dexamethasone are also administered to clients with community-acquired bacterial meningitis to prevent hearing loss and other neurological complications. Other medications may be prescribed for associated conditions, such as mannitol to treat increased ICP and anticonvulsant medications to treat seizures.

Additionally, individuals who have been in close contact with a person infected with N. meningitidis should receive prophylactic antibiotic treatment such as rifampicin, ciprofloxacin, or ceftriaxone.[13]

Nursing Interventions

Priority nursing interventions when caring for clients with meningitis are administering medication therapy and monitoring and documenting the client’s neurologic status. Other nursing interventions include monitoring vitals, decreasing environmental stimuli, and raising the head of the bed to 30 degrees or more to decrease ICP. Increased ICP can cause increased blood pressure and decreased heart rate. Blood pressure may also change if syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion develops. Additionally, clients with bacterial meningitis should be placed on droplet transmission precautions.

Health Teaching

Nurses teach clients that vaccines are the most effective way to protect against certain types of bacterial meningitis. Vaccines for three types of bacteria that can cause meningitis include the following[14]:

- Meningococcal vaccines help protect against N. meningitidis

- Pneumococcal vaccines help protect against S. pneumoniae

- Haemophilus influenzae serotype b (Hib) vaccines help protect against Hib

Adults and parents of children are encouraged to remain current on their recommended vaccination schedules to prevent meningitis.

Read more about Immunization Schedules on the CDC website.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with a family member or other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Meningitis

RN Recap: Meningitis

View a brief YouTube video overview of meningitis[15]:

- “Meninges-en.svg.png” by VG by Mysid, original by SEER Development Team [1], Jmarchn is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023, April 17). Meningitis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningitis ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023, April 17). Meningitis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningitis ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023, April 17). Meningitis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningitis ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023, April 17). Meningitis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningitis ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023, April 17). Meningitis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningitis ↵

- “Symptoms_of_Meningitis.svg.png” by Mikael Häggström is in the Public Domain ↵

- Patient Examination Videos - Educor. (2022, April 14). Brudzinksi's sign [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ueX6ZL6TPc ↵

- Patient Examination Videos - Educor. (2022, April 14). Kernig's sign [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKu8FxO8i6I ↵

- Meningitis(Nursing) by Hersi, Gonzalez, Kondamudi, & Sapkota is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Meningitis(Nursing) by Hersi, Gonzalez, Kondamudi, & Sapkota is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- CDC - Meningococcal Disease. (n.d.). Outbreaks and public health response. https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/outbreaks/index.html ↵

- CDC - Meningococcal Disease. (n.d.). Outbreaks and public health response. https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/outbreaks/index.html ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 9 - Meningitis [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/nkI4vCUi0xI?si=4UV75koNifoVDq_B ↵

Wounds should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Wound assessment should include the following components:

- Anatomic location

- Type of wound (if known)

- Degree of tissue damage

- Wound bed

- Wound size

- Wound edges and periwound skin

- Signs of infection

- Pain[1]

These components are further discussed in the following sections.

Anatomic Location and Type of Wound

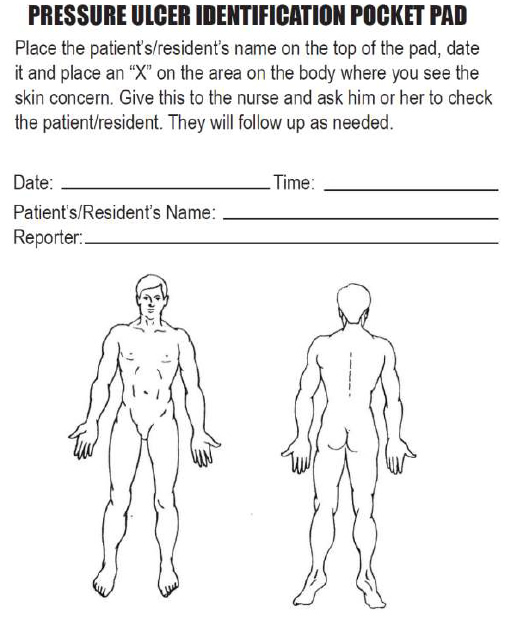

The location of the wound should be documented clearly using correct anatomical terms and numbering. This will ensure that if more than one wound is present, the correct one is being assessed and treated. Many agencies use images to facilitate communication regarding the location of wounds among the health care team. See Figure 20.16[2] for an example of facility documentation that includes images to indicate wound location.

The location of a wound also provides information about the cause and type of a wound. For example, a wound over the sacral area of an immobile patient is likely a pressure injury, and a wound near the ankle of a patient with venous insufficiency is likely a venous ulcer. For successful healing, different types of wounds require different treatments based on the cause of the wound.

Degree of Tissue Damage

It is important to continually assess the degree of tissue damage in pressure injuries because the level of damage can worsen if they are not treated appropriately. Refer to the “Staging” subsection of “Pressure Injuries” in the “Basic Concepts Related to Wounds” section for more information about tissue damage.

Wound Base

Assess the color of the wound base. Recall that healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered with biofilm. The appearance of slough (yellow) or eschar (black) in the wound base should be documented and communicated to the health care provider because it likely will need to be removed for healing. Tunneling and undermining should also be assessed, documented, and communicated.

Type and Amount of Exudate

The color, consistency, and amount of exudate (drainage) should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. The amount of drainage from wounds is categorized as scant, small/minimal, moderate, or large/copious. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms[3]:

- No exudate: The wound base is dry.

- Scant amount of exudate: The wound is moist, but no measurable amount of exudate appears on the dressing.

- Minimal amount of exudate: Exudate covers less than 25% of the size of the bandage.

- Moderate amount of drainage: Wound tissue is wet, and drainage covers 25% to 75% of the size of the bandage.

- Large or copious amount of drainage: Wound tissue is filled with fluid, and exudate covers more than 75% of the bandage.[4]

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent.

- Sanguineous: Sanguineous exudate is fresh bleeding.[5]

- Serous: Serous drainage is clear, thin, watery plasma. It’s normal during the inflammatory stage of wound healing, and small amounts are considered normal wound drainage.[6]

- Serosanguinous: Serosanguineous exudate contains serous drainage with small amounts of blood present.[7]

- Purulent: Purulent exudate is thick and opaque. It can be tan, yellow, green, or brown. It is never considered normal in a wound bed, and new purulent drainage should always be reported to the health care provider.[8] See Figure 20.17[9] for an image of purulent drainage.

Wound Size

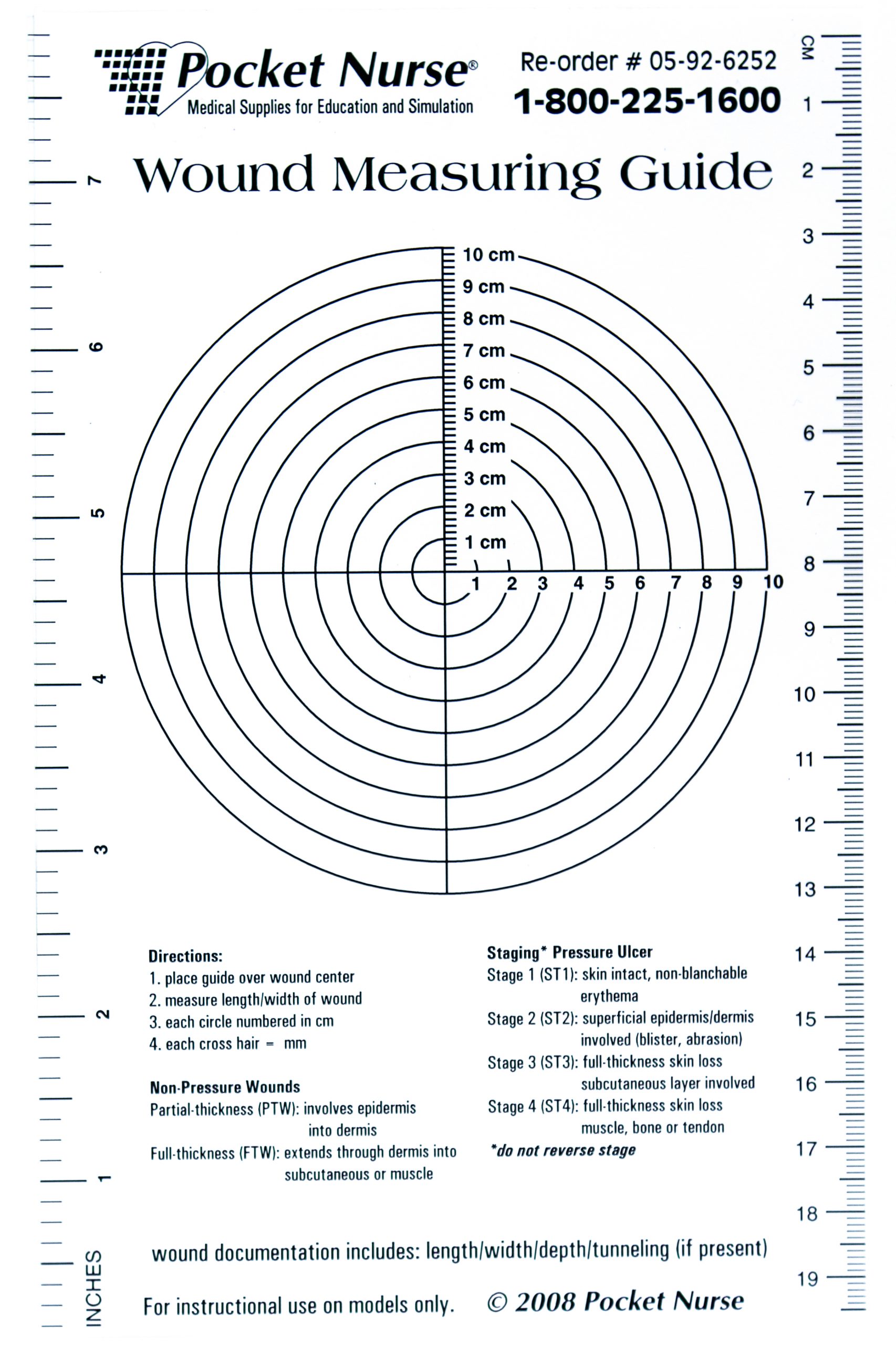

Wounds should be measured on admission and during every dressing change to evaluate for signs of healing. Accurate wound measurements are vital for monitoring wound healing. Measurements should be taken in the same manner by all clinicians to maintain consistent and accurate documentation of wound progress. This can be difficult to accomplish with oddly shaped wounds because there can be confusion about how consistently to measure them. Wounds should be described by length by width, with the length of the wound based on the head-to-toe axis. The width of a wound should be measured from side to side laterally. If a wound is deep, the deepest point of the wound should be measured to the wound surface using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator. Many facilities use disposable, clear plastic measurement tools to measure the area of a wound healing by secondary intention. Measurements are typically documented in centimeters. See Figure 20.18[10] for an image of a wound measurement tool.

Tunneling can occur in a full-thickness wound that can lead to abscess formation. The depth of a tunneling can be measured by gently probing the tunneled area with a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator from the wound base to the end of the tract. When probing a tunnel, it is imperative to not force the swab but only insert until resistance is felt to prevent further damage to the area. The location of the tunnel in the wound should be documented using the analogy of a clock face, with 12:00 pointing toward the patient’s head.[11]

Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound's edge. Undermining is measured by inserting a probe under the wound edge directed almost parallel to the wound surface until resistance is felt. The amount of undermining is the distance from the probe tip to the point at which the probe is level with the wound edge. Clock terms are also used to identify the area of undermining.[12]

Wound Edges and Periwound Skin

If the wound is healing by primary intention, it should be documented if the wound edges are well-approximated (closed together) or if there are any signs of dehiscence. The skin outside the outer edges of the wound, called the periwound skin, provides information related to wound development or healing. For example, a venous ulcer often has excess wound drainage that macerates the periwound skin, giving it a wet, waterlogged appearance that is soft and grayish white in color.[13] See Figure 20.19[14] for an image of erythematous periwound with partial dehiscence.

Signs of Infection

Wounds should be continually monitored for signs of infection. Signs of localized wound infection include erythema (redness), induration (area of hardened tissue), pain, edema, purulent exudate (yellow or green drainage), and wound odor.[15] New signs of infection should be reported to the health care provider with an anticipated order for a wound culture.

Pain

The intensity of pain that a patient is experiencing with a wound should be assessed and documented. If a patient experiences pain during dressing changes, it should be managed with administration of pain medication before scheduled dressing changes. Be aware that the degree of pain may not correlate to the extent of tissue damage. For example, skin tears are often painful because the nerve endings are exposed in the dermal layer, whereas patients with severe diabetic ulcers on their feet may experience little or no pain because of existing neuropathic damage.[16]

Wound therapy is often prescribed by a multidisciplinary team that can include the provider, a wound care nurse, a dietician, and the bedside nurse who performs dressing changes. Topical dressings should be selected that create an environment conducive to healing the specific type of wound and its causes. It is important to perform the following actions when providing wound care:

- Prevent and manage infection

- Cleanse the wound

- Debride the wound

- Maintain appropriate moisture in the wound

- Control odor

- Manage wound pain

- Consider the big picture[17]

Each of these objectives is further discussed in the following subsections.

Prevent and Manage Infection

One of the primary goals of wound dressings is to protect the wound base from bacteria and contaminants (i.e., urine and feces). If new signs of infection are present during a wound dressing change, wound swabs should be taken according to agency policy and the need for a wound culture and possible antibiotic therapy discussed with the primary provider.[18]

Silver sulfadiazine is an example of a common topical antibiotic prescribed for wounds. Topical antibiotics are covered with a secondary dressing.[19]

Cleanse the Wound

Routine cleansing should be performed at each dressing change with products that are physiologically compatible with wound tissue. Normal saline is the most gentle solution and is typically delivered using a syringe or commercial cleansers. See Figure 20.20[20] for an image of wound irrigation with a syringe. Commercial cleansers may be used, but hydrogen peroxide, betadine, and acetic acid should be avoided because these agents can be cytotoxic.[21]

Debride the Wound

Debridement is the removal of nonviable tissue in a wound. If necrotic (black) tissue is present in the wound bed, it must be removed in most circumstances for the wound to heal. However, one exception is stable, dry eschar on a patient’s heel that should be left in place until the patient’s vascular status is determined.[22]

Wound debridement can be accomplished using several methods, such as autolytic, enzymatic, or sharp wound debridement. Autolytic debridement occurs when moist topical dressings foster the breakdown of necrotic tissue. Enzymatic debridement occurs when prescribed topical agents are directly applied to the wound bed.[23] Collagenase ointment is an example of a topical enzymatic debridement ointment that is applied daily (or more frequently if the dressing becomes soiled) and covered with sterile gauze or a foam dressing.[24] Sharp wound debridement is performed by a trained health care provider and may be at the bedside or in the operating room. Sharp debridement is an invasive procedure using a scalpel or scissors to remove necrotic tissue so that only viable tissue remains. See Figure 20.21[25] for an image of a wound that has been surgically debrided of necrotic tissue.

Maintain Appropriate Moisture in the Wound

Wound dressings should maintain a moist wound environment to facilitate the development of granulation tissue. However, excessive exudate must be managed with dressings that absorb excess moisture to avoid maceration of the surrounding tissue.[26] For example, dressings such as alginate or hydrofiber are used in wounds with large amounts of exudate to maintain an appropriate moisture level but also prevent maceration of tissue. Frequent dressing changes may also be required in wounds with heavy drainage.

Eliminate Dead Space

Deep wounds and tunneling should be packed with dressings to keep the wound bed moist. Sterile gauze dressings moistened with normal saline or hydrogel-impregnated dressings are examples of packing agents used to keep the wound bed moist. Packing material should be easy to remove from the wound base during each dressing change to avoid injuring the fragile granulation tissue. Keep in mind that dressings made of alginate have a slight greenish tint when removed and should not be confused with purulent drainage.

Control Odor

If odor is present in a wound, the nurse should consult with the health care provider about the frequency of dressing changes, wound cleansing agents, and the possible need for topical antimicrobial therapy or debridement. Room deodorants can be obtained for use after dressing changes.[27]

Manage Wound Pain

Wounds that are becoming increasingly painful should be assessed for potential infection or dehiscence. The nurse should plan on administering medication to the patient before performing dressing changes on wounds that are painful. If pain medication is not ordered, then the nurse should contact the health care provider for a prescription before performing the dressing change.[28]

Protect Periwound Skin

Heavily draining wounds or the improper use of moist dressings can cause maceration of the periwound skin. The nurse should apply dressings carefully to maintain wound bed moisture yet also protect the periwound skin. Skin barrier creams, skin protective wipes, or skin barrier wafers can also be used to protect the periwound skin.[29]

Consider the Big Picture

Most wounds do not occur in isolation but also have other systemic or local factors that impact wound healing. Be sure to consider the following points when caring for patients with wounds with delayed wound healing:

- Minimize pressure and shear for patients with pressure injuries. For example, a patient with a pressure injury should be repositioned at least every two hours to minimize pressure.

- Educate patients with neuropathy and decreased sensation about preventing further injury. For example, a patient with diabetes should wear well-fitting shoes and never go barefoot to prevent injuries.

- Control edema in patients with venous ulcers through the use of compression dressings.

- Promote adequate perfusion to patients with arterial ulcers. For example, in most cases, the extremity of a patient with an arterial ulcer should not be elevated.

- Protect fragile skin in patients with skin tears to prevent further injury.

- Manage blood sugar levels in patients with diabetes mellitus for optimal healing.

- Promote good nutrition and hydration for all patients with wounds. Consult a registered dietician to assess the patient’s nutritional status and develop a nutrition plan if needed.[30]

- Document ongoing assessment findings and wound interventions for good communication and continuity of care across the multidisciplinary health care team.

- Concerns about the healing of a chronic wound or the dressings ordered should be communicated to the health care provider. Referral to a specialized wound care nurse is often helpful.