9.4 Infection

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

An infection is the invasion and growth of a microorganism within the body. Infection can lead to disease that causes signs and symptoms, resulting in a deviation from the normal structure or functioning of the host. Infection occurs when nonspecific innate immunity and specific adaptive immunity defenses are inadequate to protect an individual against the invasion of a pathogen. The ability of a microorganism to cause disease is called pathogenicity, and the degree to which a microorganism is likely to become a disease is called virulence. Virulence is a continuum. On one end of the spectrum are organisms that are not harmful, but on the other end are organisms that are highly virulent. Highly virulent pathogens will almost always lead to a disease state when introduced to the body, and some may even cause multi-organ and body system failure in healthy individuals. Less virulent pathogens may cause an initial infection, but may not always cause severe illness. Pathogens with low virulence usually result in mild signs and symptoms of disease, such as a low-grade fever, headache, or muscle aches, and some individuals may even be asymptomatic.[1]

An example of a highly virulent microorganism is Bacillus anthracis, the pathogen responsible for anthrax. The most serious form of anthrax is inhalation anthrax. After Bacillus anthracis spores are inhaled, they germinate. An active infection develops, and the bacteria release potent toxins that cause edema (fluid buildup in tissues), hypoxia (a condition preventing oxygen from reaching tissues), and necrosis (cell death and inflammation). Signs and symptoms of inhalation anthrax include high fever, difficulty breathing, vomiting, coughing up blood, and severe chest pains suggestive of a heart attack. With inhalation anthrax, the toxins and bacteria enter the bloodstream, which can lead to multi-organ failure and death of the client.[2]

Primary Pathogens Versus Opportunistic Pathogens

Pathogens can be classified as either primary pathogens or opportunistic pathogens. A primary pathogen can cause disease in a host regardless of the host’s microbiome or immune system. An opportunistic pathogen, by contrast, can cause disease only in situations that compromise the host’s defenses, such as the body’s protective barriers, immune system, or normal microbiome. Individuals susceptible to opportunistic infections include the very young, the elderly, women who are pregnant, clients undergoing chemotherapy, people with immunodeficiencies (such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), clients who are recovering from surgery, and those who have nonintact skin (such as a severe wound or burn).[3]

An example of a primary pathogen is enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (E. coli) that produces a toxin that leads to severe and bloody diarrhea, inflammation, and renal failure, even in clients with healthy immune systems. Staphylococcus epidermidis, on the other hand, is an opportunistic pathogen that is a frequent cause of healthcare acquired infection.[4] Staphylococcus epidermidis, often referred to as “staph,” is a member of the normal flora of the skin. However, in hospitals, it can grow in biofilms that form on catheters, implants, or other devices that are inserted into the body during surgical procedures. Once inside the body, it can cause serious infections such as endocarditis.[5]

Other members of normal flora can cause opportunistic infections. Some microorganisms that reside harmlessly in one location of the body can cause disease if they are passed to a different body system. For example, E. coli is normally found in the large intestine, but can cause a urinary tract infection if it enters the bladder.[6]

Normal flora can also cause disease when a shift in the environment of the body leads to overgrowth of a particular microorganism. For example, the yeast Candida is part of the normal flora of the skin, mouth, intestine, and vagina, but its population is kept in check by other organisms of the microbiome. When an individual takes antibiotics, bacteria that would normally inhibit the growth of Candida can be killed off, leading to a sudden growth in the population of Candida. An overgrowth of Candida can manifest as oral thrush (growth of yeast on mouth, throat, and tongue) or a vaginal yeast infection. Other scenarios can also provide opportunities for Candida to cause infection. For example, untreated diabetes can result in a high concentration of glucose in a client’s saliva that provides an optimal environment for the growth of Candida, resulting in oral thrush. Immunodeficiencies, such as those seen in clients with HIV, AIDS, and cancer, can also lead to Candida infections because the body’s immune system is weakened in these conditions and unable to fight off the Candida.[7]

Stages of Pathogenesis

To cause disease, a pathogen must successfully achieve four stages of pathogenesis to become an infection: exposure, adhesion (also called colonization), invasion, and infection. The pathogen must be able to gain entry to the host, travel to the location where it can establish an infection, evade or overcome the host’s immune response, and cause damage (i.e., disease) to the host. In many cases, the cycle is completed when the pathogen exits the host and is transmitted to a new host.[8]

Exposure

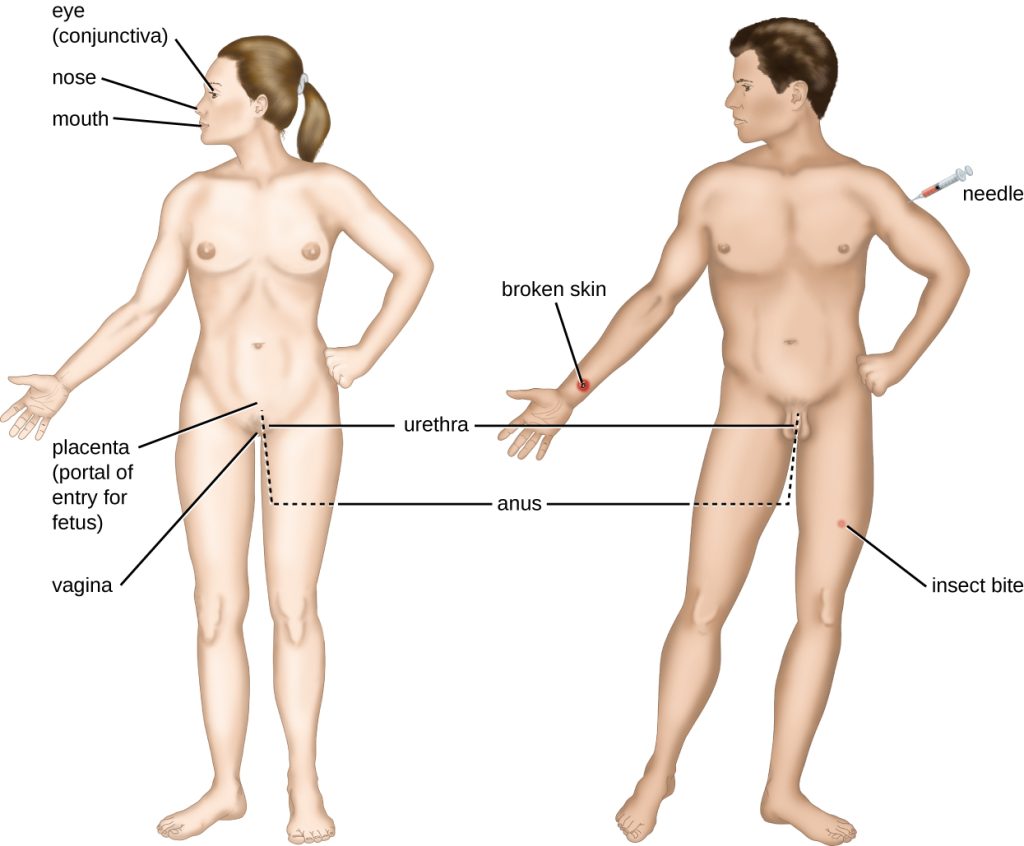

An encounter with a potential pathogen is known as exposure. The food we eat and the objects we touch are all ways that we can come into contact with potential pathogens. Yet, not all contacts result in infection and disease. For a pathogen to cause disease, it needs to be able to gain access into host tissue. An anatomic site through which pathogens can pass into host tissue is called a portal of entry. Portals of entry are locations where the host cells are in direct contact with the external environment, such as the skin, mucous membranes, respiratory, and digestive systems. Portals of entry are illustrated in Figure 9.11.[9],[10]

Adhesion

Following initial exposure, the pathogen adheres at the portal of entry. The term adhesion refers to the capability of pathogenic microbes to attach to the cells of the body, also referred to as colonization.[11]

Invasion

After successful adhesion, the invasion proceeds. Invasion means the spread of a pathogen throughout local tissues or the body. Pathogens may also produce virulence factors that protect them against immune system defenses and determine the degree of tissue damage that occurs. Intracellular pathogens like viruses achieve invasion by entering the host’s cells and reproducing.[12]

Infection

Following invasion, successful multiplication of the pathogen leads to infection. Infections can be described as local, secondary, or systemic, depending on the extent of the infection.[13]

A local infection is confined to a small area of the body, typically near the portal of entry. For example, a hair follicle infected by Staphylococcus aureus infection may result in a boil around the site of infection, but the bacterium is largely contained to this small location. Other examples of local infections that involve more extensive tissue involvement include urinary tract infections confined to the bladder or pneumonia confined to the lungs. Localized infections generally demonstrate signs of inflammation, such as redness, swelling, warmth, pain, and purulent drainage. However, extensive tissue involvement can also cause decreased functioning of the organ affected.[14]

A secondary infection is an infection that occurs during or after treatment for a different infection. It may be caused by the treatment for the first infection or a result of a diminished immune system or the elimination of normal flora. For example, a yeast infection that occurs after a client is treated with antibiotics is a secondary infection.[15]

When an infection becomes disseminated throughout the body, it is called a systemic infection. For example, infection by the varicella-zoster virus typically gains entry through a mucous membrane of the upper respiratory system. It then spreads throughout the body, resulting in a classic red rash associated with chicken pox. Because these lesions are not sites of initial infection, they are signs of a systemic infection. Systemic infections can cause fever, increased heart and respiratory rates, lethargy, malaise, anorexia, and tenderness and enlargement of the lymph nodes.[16]

Sometimes a primary infection can lead to a secondary infection by an opportunistic pathogen. For example, when a client experiences a primary infection from influenza, it can damage and decrease the defense mechanisms of the lungs, making the client more susceptible to a secondary pneumonia by a bacterial pathogen like Haemophilus influenzae. Additionally, treatment of the primary infection may lead to a secondary infection caused by an opportunistic pathogen. For example, antibiotic therapy targeting the primary infection alters the normal flora and creates an opening for opportunistic pathogens like Clostridium difficile or Candida Albicans to cause a secondary infection.[17]

Bacteremia, SIRS, Sepsis, and Septic Shock

When infection occurs, pathogens can enter the bloodstream. The presence of bacteria in blood is called bacteremia. If bacteria are both present and multiplying in the blood, it is called septicemia.[18]

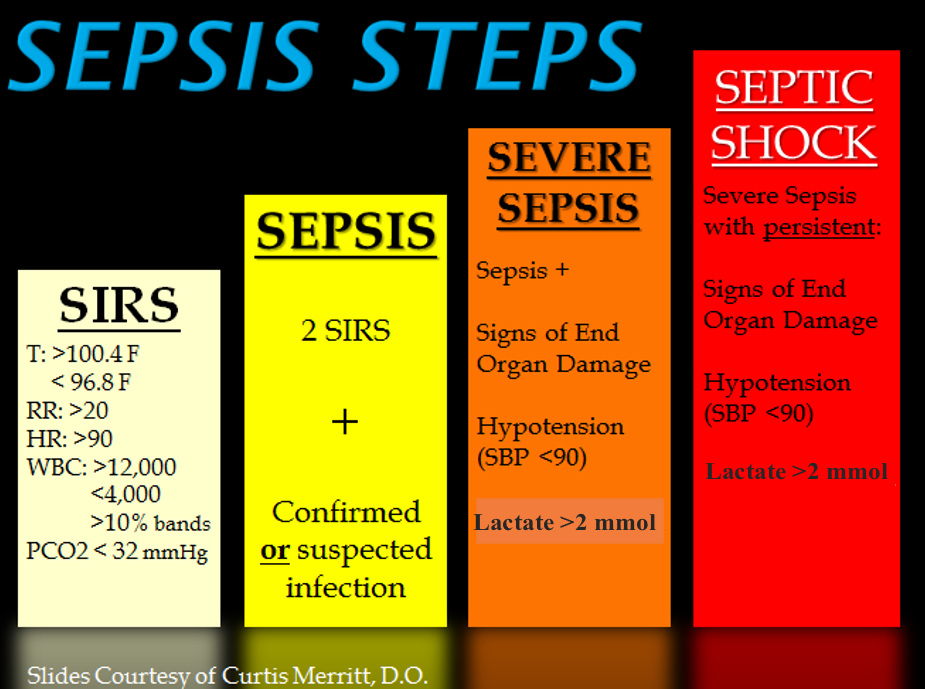

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is an exaggerated inflammatory response that affects the entire body. It is the body’s reaction to a noxious stressor, including causes such as infection and acute inflammation, but other conditions can trigger it as well. Signs of SIRS are as follows:

- Body temperature over 38 or under 36 degrees Celsius

- Heart rate greater than 90 beats/minute

- Respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths/minute or PaCO2 less than 32 mmHg

- White blood cell count greater than 12,000 or less than 4,000 /microliters or over 10% of immature forms (bands)[19]

Even though the purpose of SIRS is to defend against a noxious stressor, the uncontrolled release of massive amounts of cytokines, called cytokine storm, can lead to organ dysfunction and even death.[20]

Sepsis refers to SIRS that is caused by an infection. Sepsis occurs when an existing infection triggers an exaggerated inflammatory reaction throughout the body. If left untreated, sepsis causes tissue and organ damage. It can quickly spread to multiple organs and is a life-threatening medical emergency.

Sepsis causing damage to one or more organs (such as the kidneys) is called severe sepsis. Severe sepsis can lead to septic shock, a life-threatening decrease in blood pressure (systolic pressure <90 mm Hg) that prevents cells and other organs from receiving enough oxygen and nutrients, causing multi-organ failure and death. See Figure 9.12[21] for an illustration of the progression of sepsis from SIRS to septic shock.

Unfortunately, almost any type of infection in any individual can lead to sepsis. Infections that lead to sepsis most often start in the lungs, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, or skin. Some people are especially at risk for developing sepsis, such as adults over age 65; children younger than one year old; people who are immunocompromised or have chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, lung disease, cancer, and kidney disease; and survivors of a previous sepsis episode.[22]

In addition to exhibiting signs of SIRS, clients with sepsis may also have additional signs such as elevated fever and shivering, confusion, shortness of breath, pain or discomfort, and clammy or sweaty skin. Diligent nursing care is vital for recognizing early signs of SIRS and sepsis and promptly notifying the health care provider and/or following sepsis protocols in place at your health care facility.[23]

Use the following to read more information about sepsis:

- Read more information about sepsis at the CDC’s Sepsis web page.

- Read the CDC infographic on Protect Your Patients From Sepsis.

- Read an article about caring for clients with sepsis titled Something Isn’t Right: The Subtle Changes of Early Deterioration.

- Read more about the Surviving Sepsis Campaign with early recognition and treatment of sepsis using the Hour-1 Bundle.

Toxins

Some pathogens release toxins that are biological poisons that assist in their ability to invade and cause damage to tissues. For example, Botulinum toxin is a neurotoxin produced by the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum that is an acutely toxic substance because it blocks the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The toxin’s blockage of acetylcholine results in muscle paralysis with the potential to stop breathing due to its effect on the respiratory muscles. This condition is referred to as botulism, a type of food poisoning that can be caused by improper sterilization of canned foods. However, because of its paralytic action, low concentrations of Botox are also used for beneficial purposes such as cosmetic procedures to remove wrinkles and in the medical treatment of overactive bladder.[24]

Another type of neurotoxin is tetanus toxin, which is produced by the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium tetani. Tetanus toxin inhibits the release of GABA, resulting in permanent muscle contraction. The first symptom of tetanus is typically stiffness of the jaw. Violent muscle spasms in other parts of the body follow, typically culminating with respiratory failure and death. Because of the severity of tetanus, it is important for nurses to encourage individuals to regularly receive tetanus vaccination boosters throughout their lifetimes.[25]

Stages of Disease

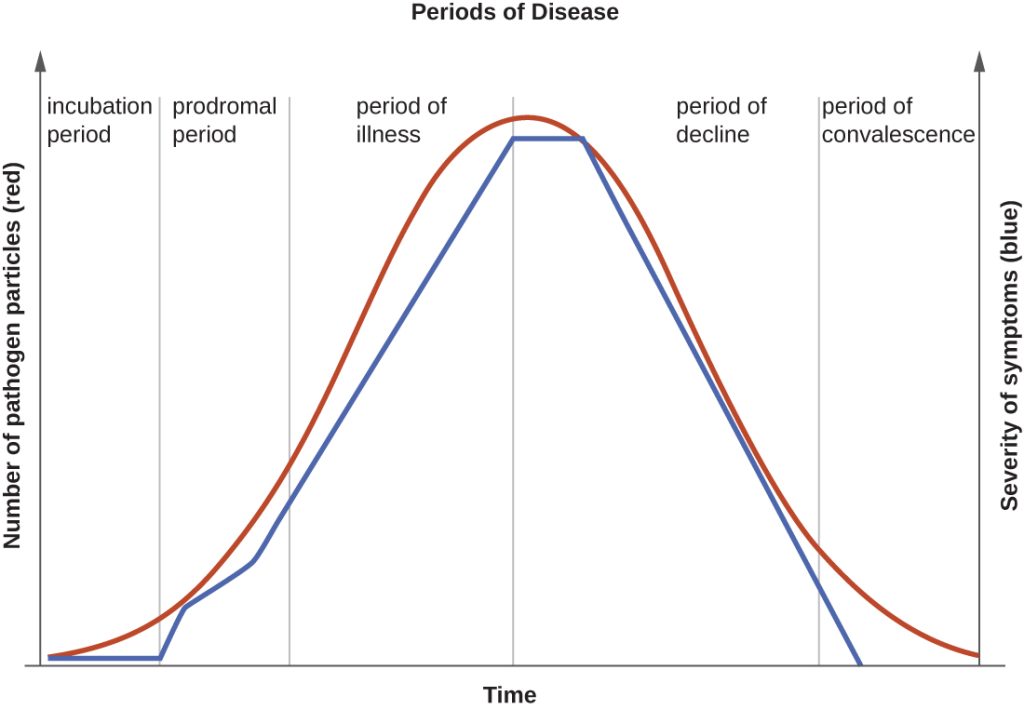

When a pathogen becomes an infection-causing disease, there are five stages of disease, including the incubation, prodromal, illness, decline, and convalescence periods. See Figure 9.13[26] for an illustration of the stages of disease.

Incubation Period

The incubation period occurs after the initial entry of the pathogen into the host when it begins to multiply, but there are insufficient numbers of the pathogen present to cause signs and symptoms of disease. Incubation periods can vary from a day or two in acute disease to months or years in chronic disease, depending upon the pathogen. Factors involved in determining the length of the incubation period are diverse and can include virulence of the pathogen, strength of the host immune defenses, site of infection, and the amount of the pathogen received during exposure. During this incubation period, the client is unaware that a disease is beginning to develop.[27]

Prodromal Period

The prodromal period occurs after the incubation period. During this phase, the pathogen continues to multiply, and the host begins to experience general signs and symptoms of illness caused from activation of the nonspecific innate immunity, such as not feeling well (malaise), low-grade fever, pain, swelling, or inflammation. These signs and symptoms are often too general to indicate a particular disease is occurring.[28]

Acute Phase

Following the prodromal period is the period of acute illness, during which the signs and symptoms of a specific disease become obvious and can become severe. This period of acute illness is followed by the period of decline as the immune system overcomes the pathogen. The number of pathogen particles begins to decline and thus the signs and symptoms of illness begin to decrease. However, during the decline period, clients may become susceptible to developing secondary infections because their immune systems have been weakened by the primary infection.[29]

Convalescent Period

The final period of disease is known as the convalescent period. During this stage, the client generally returns to normal daily functioning, although some diseases may inflict permanent damage that the body cannot fully repair.[30] For example, if a strep infection becomes systemic and causes a secondary infection of the client’s heart valves, the heart valves may never return to full function and heart failure may develop.

Infectious diseases can be contagious during all five of the periods of disease. The transmissibility of an infection during these periods depends upon the pathogen and the mechanisms by which the disease develops and progresses. For example, with many viral diseases associated with rashes (e.g., chicken pox, measles, rubella, roseola), clients are contagious during the incubation period up to a week before the rash develops. In contrast, with many respiratory infections (e.g., colds, influenza, diphtheria, strep throat, and pertussis) the client becomes contagious with the onset of the prodromal period. Depending upon the pathogen, the disease, and the individual infected, transmission can still occur during the periods of decline, convalescence, and even long after signs and symptoms of the disease disappear. For example, an individual recovering from a diarrheal disease may continue to carry and shed the pathogen in feces for a long time, posing a risk of transmission to others through direct or indirect contact.[31]

Types of Infection

Acute vs. Chronic

Acute, self-limiting infections develop rapidly and generally last only 10-14 days. Colds and ear infections are considered acute, self-limiting infections. See Figure 9.14[32] for an image of an individual with an acute, self-limiting infection. Conversely, chronic infections may persist for months. Hepatitis and mononucleosis are examples of chronic infections.[33]

Healthcare-Associated Infections

An infection that is contracted in a health care facility or under medical care is known as a healthcare-associated infection (HAI), formerly referred to as a nosocomial infection. On any given day, about 1 in 31 hospital clients has at least one healthcare-associated infection. HAIs increase the cost of care and delay recovery and are associated with permanent disability, loss of wages, and even death.[34],[35]

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has established these goals to reduce these common healthcare-associated infections in health care institutions:

- Reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI)

- Reduce catheter-associated urinary tracts infections (CAUTI)

- Reduce the incidence of invasive health care-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Reduce hospital-onset MRSA bloodstream infections

- Reduce hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infections

- Reduce the rate of Clostridium difficile hospitalizations

- Reduce surgical site infections (SSI)[36],[37]

Blood-borne Pathogens

Blood-borne pathogens are potentially present in a client’s blood and body fluids, placing other clients and health care providers at risk for infection if they are exposed. The most common blood-borne pathogens include hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

When a nurse or other health care worker experiences exposure due to a needlestick injury or the splashing of body fluids, it should be immediately washed or flushed and then reported so that careful monitoring can occur. When the source of the exposure is known, the health care worker and client are initially tested. Repeat testing and medical prophylaxis may be warranted for the health care worker, depending on the results.[38]

Needlesticks and sharps injuries are the most common causes of blood-borne pathogen exposure for nurses. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has developed a comprehensive Sharps Injury Prevention Program to decrease needle and sharps injury in health care workers.[39]

Needles are also used in the community, such as at home, work, airports, or public restrooms as individuals use needles to administer prescribed medications or to inject illegal drugs. Nurses can help prevent needlestick and sharps injuries in their community by implementing a community needle disposal program.

Read more about needlestick and sharps injury prevention in the “Aseptic Technique” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier. pp. 214, 226-227, 346. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “OSC_Microbio_15_02_Portal.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Medline Plus. (2024). Secondary infections. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002300.htm ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Mouton, C. P., Bazaldua, O., Pierce, B., & Espino, D. V. (2001). Common infections in older adults. American Family Physician, 63(2), 257-269. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/0115/p257.html ↵

- Mouton, C. P., Bazaldua, O., Pierce, B., & Espino, D. V. (2001). Common infections in older adults. American Family Physician, 63(2), 257-269. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/0115/p257.html ↵

- This work is derivative of “Sepsis_Steps.png” by Hadroncastle and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 18). Sepsis. https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 18). Sepsis. https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/index.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “unknown image” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/15-1-characteristics-of-infectious-disease ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “392131387-huge.jpg” by Alexandr Litovchenko is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, March 4). Healthcare-associated infections. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/index.html ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, January 15). Healthcare-associated infections. https://health.gov/our-work/health-care-quality/health-care-associated-infections ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, March 4). Healthcare-associated infections. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/index.html ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, January 15). Healthcare-associated infections. https://health.gov/our-work/health-care-quality/health-care-associated-infections ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Bloodborne pathogen exposure. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2007-157/default.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). How to prevent needlestick and sharps injuries. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2012-123/ ↵

The invasion and growth of a microorganism within the body.

Signs and symptoms resulting in a deviation from the normal structure or functioning of the host.

The ability of a microorganism to cause disease.

The degree to which a microorganism is likely to become a disease.

A pathogen that can cause disease in a host regardless of the host’s resident microbiota or immune system.

A pathogen that only causes disease in situations that compromise the host’s defenses, such as the body’s protective barriers, immune system, or normal microbiota.

An encounter with a potential pathogen.

An anatomic site through which pathogens can pass into a host, such as mucous membranes, skin, respiratory, or digestive systems.

Capability of pathogenic microbes to attach to the cells of the body.

Means the spread of a pathogen throughout local tissues or the body.

Infection confined to a small area of the body, typically near the portal of entry, and usually presents with signs of redness, warmth, swelling, warmth, and pain.

A localized pathogen that spreads to a secondary location.

An infection that becomes disseminated throughout the body.

The presence of bacteria in blood.

Bacteria that are both present and multiplying in the blood.

An exaggerated inflammatory response to a noxious stressor (including, but not limited to, infection and acute inflammation) that affects the entire body.

An existing infection that triggers an exaggerated inflammatory reaction called SIRS throughout the body.

Severe sepsis that leads to a life-threatening decrease in blood pressure (systolic pressure <90 mm Hg), preventing cells and other organs from receiving enough oxygen and nutrients. It can cause multi organ failure and death.

The period of a disease after the initial entry of the pathogen into the host but before symptoms develop.

The disease stage after the incubation period when the pathogen continues to multiply and the host begins to experience general signs and symptoms of illness that result from activation of the immune system, such as fever, pain, soreness, swelling, or inflammation.

As discussed in the previous section, hospitals and health care providers are paid for services provided to individuals by government insurance programs (such as Medicare and Medicaid), private insurance companies, or people using their out-of-pocket funds. Traditionally, health care institutions were paid based on a “fee-for-service” model. For example, if a patient was admitted to a hospital with pneumonia, the hospital billed that individual's insurance program for the cost of care.

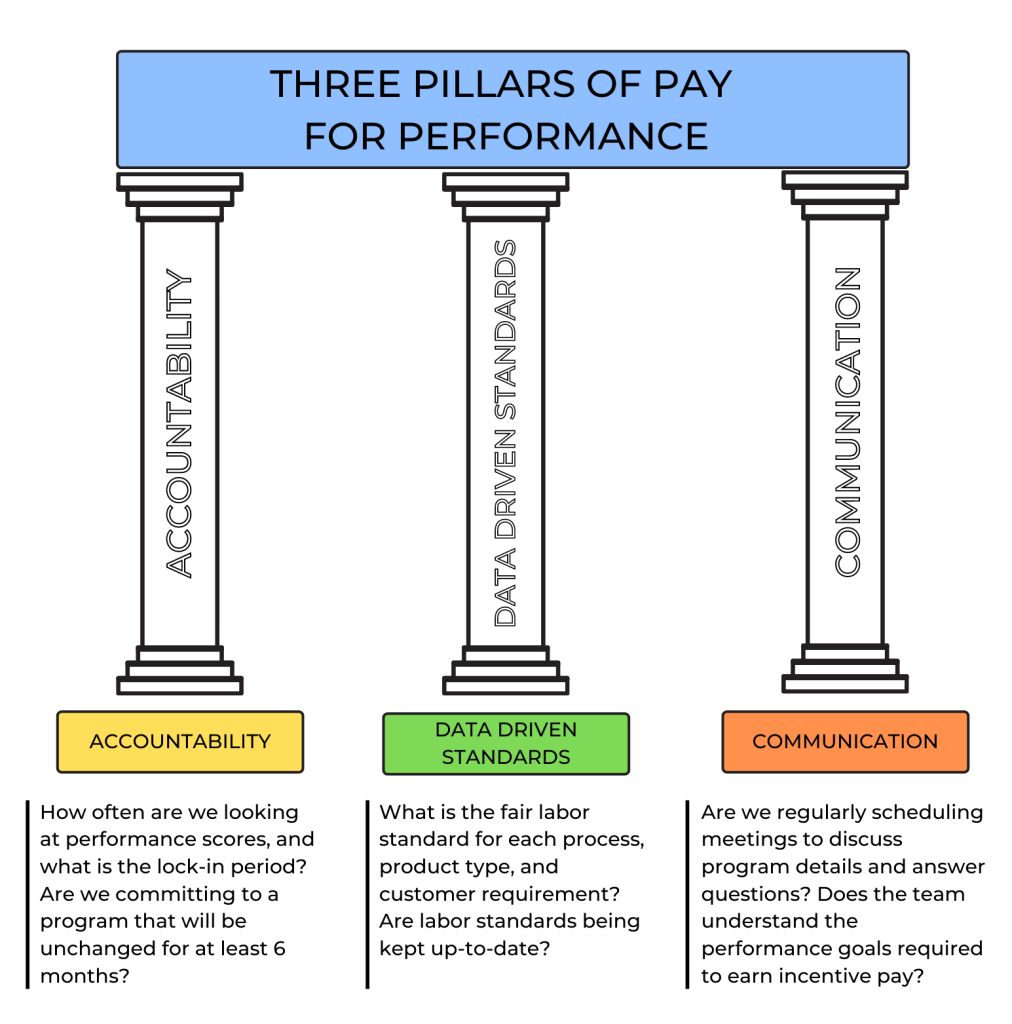

However, as part of a recent national strategy to reduce health care costs, insurance providers have transitioned to "Pay for Performance" reimbursement models that are based on overall agency performance and patient outcomes.

Pay for Performance

Pay for Performance, also known as value-based payment, refers to reimbursement models that attach financial incentives to the performance of health care agencies and providers. Pay for Performance models tie higher reimbursement payments to positive patient outcomes, best practices, and patient satisfaction, thus aligning payment with value and quality.[1] Nurses support higher reimbursement levels to their employers based on their documentation related to nursing care plans and achievement of expected patient outcomes.

There are two Pay for Performance models. The first model rewards hospitals and providers with higher reimbursement payments based on how well they perform on process, quality, and efficiency measures. The second model penalizes hospitals and providers for subpar performance by reducing reimbursement amounts.[2] For example, Medicare no longer reimburses hospitals to treat patients who acquire certain preventable conditions during their hospital stay, such as pressure injuries or urinary tract infections associated with use of catheters.[3]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), spurred by the Affordable Care Act, has led the way in value-based payment with a variety of payment models. CMS is the largest health care funder in the United States with almost 40% of overall health care spending for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS developed three Pay for Performance models that impact hospitals’ reimbursement by Medicare. These models are called the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. Private insurers are also committed to performance-based payment models. In 2017 Forbes reported that almost 50% of insurers’ reimbursements were in the form of value-based care models.[4]

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program

The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (VBP) was designed to improve health care quality and patient experience by using financial incentives that encourage hospitals to follow established best clinical practices and improve patient satisfaction scores via patient satisfaction surveys. Reimbursement is based on hospital performance on measures divided into four quality domains: safety, clinical care, efficiency and cost reduction, and patient and caregiver-centered experience.[5] The VBP program rewards hospitals based on the quality of care provided to Medicare patients and not just the quantity of services that are provided. Hospitals may have their Medicaid payments reduced by up to 2% if not meeting the quality metrics.

Read more about patient satisfaction surveys.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) penalizes hospitals with higher rates of patient readmissions compared to other hospitals. HRRP was established by the Affordable Care Act and applies to patients with specific conditions, such as heart attacks, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hip or knee replacements, and coronary bypass surgery. Hospitals with poor performance receive a 3% reduction of their Medicare payments. However, it was discovered that hospitals with higher proportions of low-income patients were penalized the most, so Congress passed legislation in 2019 that divided hospitals into groups for comparison based on the socioeconomic status of their patient populations.[6]

Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program

The Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP) was established by the Affordable Care Act. This Pay for Performance model reduces payments to hospitals based on poor performance regarding patient safety and hospital-acquired conditions, such as surgical site infections, hip fractures resulting from falls, and pressure injuries. This model has saved Medicare approximately $350 million per year.[7]

The HACRP model measures the incidence of hospital-acquired conditions, including central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), surgical site infections (SSI), Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA), and Clostridium Difficile (C. diff).[8] As a result, nurses have seen changes in daily practices based on evidence-based practices related to these conditions. For example, stringent documentation is now required for clients with Foley catheters that indicates continued need and associated infection control measures.

Other CMS Pay for Performance Models

CMS has created other value-based payment programs for agencies other than hospitals, including the End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Quality Initiative Program, the Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Program (SNFVBP), the Home Health Value-Based Program (HHVBP), and the Value Modifier (VM) Program. The VM program is aimed at Medicare Part B providers who receive high, average, or low ratings based on quality and cost measurements as compared to peer agencies.

Impacts of Value-Based Payment

Pay for Performance (i.e., value-based payment) stresses quality over quantity of care and allows health care payers to use reimbursement to encourage best clinical practices and promote positive health outcomes. It focuses on transparency by using metrics that are publicly reported, thus incentivizing organizations to protect and strengthen their reputations. In this manner, Pay for Performance models encourage accountability and consumer-informed choice.[9] See Figure 8.8[10] for an illustration of Pay for Performance.

Pay for Performance models have reduced health care costs and decreased the incidence of poor patient outcomes. For example, 30-day hospital readmission rates have been falling since 2012, indicating HRRP and HACRP are having an impact.[11]

However, there are also disadvantages to value-based payment. As previously discussed, initial research indicated hospitals with higher proportions of low-income patients were being penalized the most, resulting in additional legislation to compare hospital performance in groups based on their clients’ socioeconomic status. Nursing leaders continue to emphasize strategies that further address social determinants of health and promote health equity.[12] Read more about equity and social determinants of health in the following subsection.

Nursing Considerations

Nurses have a direct impact on activities related to quality care and reimbursement rates received by their employer. There are several categories of actions nurses can take to improve quality patient care, reduce costs, and improve reimbursement. By incorporating these actions into their daily care, nurses can help ensure the funding they need to provide quality patient care is received by their employer and resources are allocated appropriately to their patients.

The following categories of actions to improve quality of care are based on the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System and Crossing the Quality Chasm[13]:

- Effectiveness and Efficiency: Nurses support their institution's effectiveness and efficiency with individualized nursing care planning, good documentation, and care coordination. With accurate and timely documentation and care coordination, there is reduced care duplication and waste. Coordinating care also helps to reduce the risk of hospital readmissions.

- Timeliness: Nurses positively impact timeliness by prioritizing and delegating care. This helps reduce patient wait times and delays in care.

Read more about these concepts in the “Delegation and Supervision” and “Prioritization” chapters in this book.

- Safety: Nurses pay attention to their patients’ changing conditions and effectively communicate these changes with appropriate health care team members. They take any concerns about client care up the chain of command until their concerns are resolved.

- Patient-Centered Care: Nurses support this quality measure by ensuring nursing care plans are individualized for each patient. Effective care plans can improve patient compliance, resulting in improved patient outcomes.

- Evidence-Based Practice: Nurses provide care based on evidence-based practice. Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is defined by the American Nurses Association as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and patient, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[14] EBP is a component of Scholarly Inquiry, one of the ANA’s Standards of Professional Practice. Nurses’ implementation of EBP ensures proper resources are allocated to the appropriate clients. EBP promotes safe, efficient, and effective health care.[15],[16]

Read more information about EBP in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter of this book.

- Equity: Health care institutions care for all members of their community regardless of client demographics and their associated social determinants of health (SDOH). SDOH are conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes. Health disparities in communities with poor SDOH have been consistently documented in reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[17]

Nurses address negative determinants of health by advocating for interventions that reduce health disparities and promote the delivery of equitable health care resources. The term health disparities describes the differences in health outcomes that result from SDOH. Advocating for resources that enhance quality of life can significantly influence a community's health outcomes. Examples of resources that promote health include safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free of life-threatening toxins.

A related term is health care disparity that refers to differences in access to health care and insurance coverage. Health disparities and health care disparities can lead to decreased quality of life, increased personal costs, and lower life expectancy. More broadly, these disparities also translate to greater societal costs, such as the financial burden of uncontrolled chronic illnesses. An example of nurses addressing health care disparities are nurse practitioners providing health care according to their scope of practice to underserved populations in rural communities.

The ANA promotes nurse advocacy in workplaces and local communities. There are many ways nurses can promote health and wellness within their communities through a variety of advocacy programs at the federal, state, and community level.[18] Read more about advocacy and reducing health disparities in the following boxes.

Read more about ANA Policy and Advocacy.

Read more information in the “Advocacy” chapter of this book.

Read more about addressing health disparities in the “Diverse Patients” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Economics and health care reimbursement models impact health care institutional budgets that ultimately impact nurse staffing. A budget is an estimate of revenue and expenses over a specified period of time, usually over a year. There are two basic types of health care budgets that affect nursing: capital and operating budgets. Capital budgets are used to plan investments and upgrades to tangible assets that lose or gain value over time. Capital is something that can be touched, such as buildings or computers. Operating budgets include personnel costs and annual facility operating costs.[19] Typically 40% of the operating budgets of health care agencies are dedicated to nursing staffing. As a result, nursing is often targeted for reduced hours and other cutbacks.[20]

What is the value of a nurse? Nurses are priceless to the clients, families, and communities they serve, but health care organizations are tasked with calculating the cost of delivering safe, high-quality nursing care using affordable staffing models. All members of the health care team must understand the relationship between economics, resources, budgeting, and staffing, and how these issues affect their ability to provide safe, quality care to their patients.

As health care agencies continue to adapt to meet “Pay for Performance” reimbursement models and deliver cost-effective care to an aging population with complex health needs, many nurses are experiencing changes in staffing models.[21] Strategies implemented by agencies to facilitate cost-effective nurse staffing include acuity-based staffing, team nursing, mandatory overtime, floating, on call, and off with benefits. Agencies may also use agency nurses when nurse shortages occur.

Acuity-Based Staffing

Historically, inpatient staffing patterns focused on “nurse-to-patient ratios” where a specific number of patients were assigned to each registered nurse during a shift. Acuity-based staffing is a patient assignment model that takes into account the level of patient care required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. As a result of acuity-based staffing, the number of clients a nurse cares for often varies from shift to shift as the needs of the patients change. Acuity-based staffing promotes efficient use of resources by ensuring nurses have adequate time to care for complex patients.

Read more information about acuity-based staffing in the “Prioritization” chapter.

Team Nursing

Team nursing is a common staffing pattern that uses a combination of Registered Nurses (RNs), Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses (LPN/VNs), and Assistive Personnel (AP) to care for a group of patients. The RN is the leader of a nursing team, making assignments and delegating nursing care to other members of the team with appropriate supervision. Team nursing is an example of allocating human resources wisely to provide quality and cost-effective care. In order for team nursing to be successful, team members must use effective communication and organize their shift as a team.

Read more about team nursing in the “Delegation and Supervision” chapter of this book.

Mandatory Overtime

When client numbers and acuity levels exceed the number of staff scheduled for a shift, nurses may experience mandatory overtime as an agency staffing tool. Mandatory overtime requires a nurse to stay and care for patients beyond their scheduled shift when there is a lack of nursing staff (often referred to as short staffing). The American Nurses Association recognizes mandatory overtime as a dangerous staffing practice because of patient safety concerns related to overtired staff. Depending on state laws, nurses can be held liable for patient abandonment or neglect charges for refusing to stay when mandated. Nurses should be aware of state and organizational policies related to mandatory overtime.[22]

Read more about ANA’s advocacy for adequate nurse staffing.

Floating

Floating is a common agency staffing strategy that asks nurses to temporarily work on a different unit to help cover a short-staffed shift. Floating can reduce personnel costs by reducing overtime payments for staff. It can also reduce nurse burnout occurring from working in an environment without enough personnel.

Nurses must be aware of their rights and responsibilities when asked to float because they are still held accountable for providing safe patient care according to their state's Nurse Practice Act and professional standards of care. Before accepting a floating assignment, nurses should ensure the assignment is aligned with their skill set and they receive orientation to the new environment before caring for patients. If an error occurs and the nurse is held liable, the fact they received a floating assignment does not justify the error. As the ANA states, nurses don’t just have the right to refuse a floating patient assignment; they have the obligation to do so if it is unsafe.[23] The ANA has developed several questions to guide nurses through the decision process of accepting patient assignments. Review these questions in the following box.

ANA’s Suggested Questions When Deciding on Accepting a Patient Assignment[24]

- What is the assignment? Clarify what is expected; do not assume. Be certain about the details.

- What are the characteristics of the patients being assigned? Don’t just respond to the number of patients assigned. Make a critical assessment of the needs of each client and their complexity and stability. Be aware of the resources available to meet those needs.

- Do you have the expertise to care for the patients? Always ask yourself if you are familiar with caring for the types of patients assigned? If this is a “float assignment,” are you cross-trained to care for these patients? Is there a “buddy system” in place with staff who are familiar with the unit? If there is no cross-training or “buddy system,” has the patient load been modified accordingly?

- Do you have the experience and knowledge to manage the patients for whom you are being assigned care? If the answer to the question is “No,” you have an obligation to articulate your limitations. Limitations in experience and knowledge may not require refusal of the assignment, but rather an agreement regarding supervision or a modification of the assignment to ensure patient safety. If no accommodation for limitations is considered, the nurse has an obligation to refuse an assignment for which they lack education or experience.

- What is the geography of the assignment? Are you being asked to care for patients who are in close proximity for efficient management, or are the patients at opposite ends of the hall or in different units? If there are geographic difficulties, what resources are available to manage the situation? If the patients are in more than one unit and you must go to another unit to provide care, who will monitor patients out of your immediate attention?

- Is this a temporary assignment? When other staff are located for assistance, will you be relieved? If the assignment is temporary, it may be possible to accept a difficult assignment knowing that there will soon be reinforcements. Is there a pattern of short staffing at this agency, or is this truly an emergency?

- Is this a crisis or an ongoing staffing pattern? If the assignment is being made because of an immediate need or crisis in the unit, the decision to accept the assignment may be based on that immediate need. However, if the staffing pattern is an ongoing problem, you have the obligation to identify unmet standards of care that are occurring as a result of ongoing staffing inadequacies. This may result in a formal request for peer review using the appropriate channels.

- Can you take the assignment in good faith? If not, you will need to have the assignment modified or refuse the assignment. Consult your state’s Nurse Practice Act regarding clarification of accepting an assignment in good faith.

On Call and Off With Benefits

When staffing projected for a shift exceeds the number of clients admitted and their acuity, agencies often decrease staffing due to operating budget limitations. Two common approaches that agencies use to reduce staffing on a shift-to-shift basis are placing nurses “on call” or “off with benefits.”

On Call

On call is an agency staffing strategy when a nurse is not immediately needed for their scheduled shift. The nurse may have the options to report to work and do work-related education or stay home. When a nurse is on call, they typically receive a reduced hourly wage and have a required response time. A required response time means if a nurse who is on call is needed later in the shift, they need to be able to report and assume patient care in a designated amount of time.

Off With Benefits

A nurse may be placed “off with benefits” when not needed for their scheduled shift. When a nurse is placed off with benefits, they typically do not receive an hourly wage and are not expected to report to work or be on call, but still accrue benefits such as insurance and paid time off.

Agency Nursing

Agency nursing is an industry in health care that provides nurses to hospitals and health care facilities in need of staff. Nurse agencies employ nurses to work on an as-needed basis and place them in facilities that have staffing shortages.

Advocacy by the ANA for Appropriate Nurse Staffing

According to the ANA, there is significant evidence showing appropriate nurse staffing contributes to improved client outcomes and greater satisfaction for both clients and staff. Appropriate staffing levels have multiple client benefits, including the following[25]:

- Reduced mortality rates

- Reduced length of client stays

- Reduced number of preventable events, such as falls and infections

Nurses also benefit from appropriate staffing. Appropriate workload allows nurses to utilize their full expertise, without the pressure of fatigue. A recent report suggested that staff levels should depend on the following factors[26]:

- Patient complexity, acuity, or stability

- Number of admissions, discharges, and transfers

- Professional nurses’ and other staff members’ skill level and expertise

- Physical space and layout of the nursing unit

- Availability of technical support and other resources

Visit ANA's interactive Principles of Nurse Staffing infographic.

Read more information about patient acuity tools in the "Prioritization" chapter.

Cost-Effective Nursing Care

One of ANA's Standards of Professional Performance is Resource Stewardship. The Resource Stewardship standard states, “The registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan, provide, and sustain evidence-based nursing services that are safe, effective, financially responsible, and used judiciously.”[27] Nurses have a fiscal responsibility to demonstrate resource stewardship to the employing organization and payer of care. This responsibility extends beyond direct patient care and encompasses a broader role in health care sustainability. By effectively managing resources, nurses help reduce unnecessary expenditures and ensure that funds are allocated where they are most needed. This can include everything from minimizing waste in the use of medical supplies to optimizing staffing levels to avoid both overworking and underutilizing nursing staff.

Nurses can help contain health care costs by advocating for patients and ensuring their care is received on time, the plan of care is appropriate and individualized to them, and clear documentation has been completed. These steps reduce waste, avoid repeated tests, and ensure timely treatments that promote positive patient outcomes and reduce unnecessary spending. Nurses routinely incorporate these practices to provide cost-effective nursing care in their daily practice:

- Keeping supplies near the client's room

- Preventing waste by only bringing needed supplies into a client’s room

- Avoiding prepackaged kits with unnecessary supplies

- Avoiding “Admission Bags” with unnecessary supplies

- Using financially-sound thinking

- Understanding health care costs and reimbursement models

- Charging out supplies and equipment according to agency policy

- Being Productive

- Organizing and prioritizing

- Using effective time management

- Grouping tasks when entering client rooms (i.e., clustering cares)

- Assigning and delegating nursing care to the nursing team according to the state Nurse Practice Act and agency policy

- Using effective team communication to avoid duplication of tasks and request assistance when needed

- Updating and individualizing clients’ nursing care plans according to their current needs

- Documenting for continuity of client care that avoids duplication and focuses on effective interventions based on identified outcomes and goals