9.10 Multiple Sclerosis

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease triggered by an immune-mediated response that leads to progressive demyelination in the CNS. MS is the most common disabling neurological disease among young adults between the ages of 20 to 50 years. MS tends to occur among whites of Northern European ancestry, but it can affect people of all ethnicities. MS affects women two to three times more than men. Although the exact reason for this gender difference is not known, hormonal influences are thought to play a part.

Pathophysiology

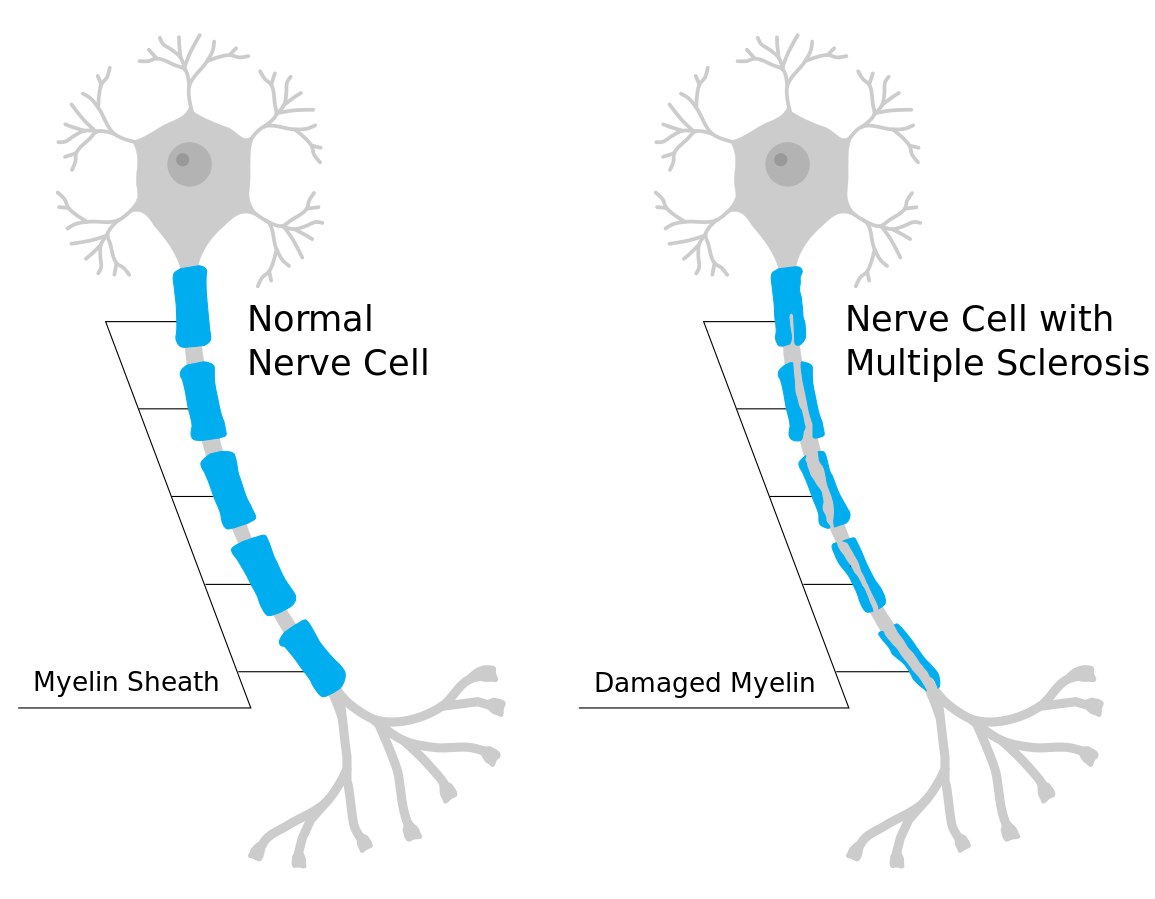

During MS, demyelination occurs. Demyelination refers to the loss or destruction of the myelin sheath. During demyelination, scar tissue forms and creates lesions. Myelin, commonly called the “white matter,” consists of fatty and protein substances that surround and protect nerve fibers of the brain and spinal cord. As this protective functional layer is lost, the transmission of nerve impulses between the brain, spinal cord, and the rest of the body becomes impaired. This impairment causes a delay or blockage of impulse transmission, resulting in impaired mobility and sensory functions. Initially, in the disease process, the body attempts remyelination, and the clinical symptoms may decrease to some degree. However, new lesions often develop, leading to neuronal injury and muscle atrophy. See Figure 9.27[1] for an illustration of damaged myelin that occurs in MS.

The cause of MS is complex and entails several immune, infectious, and genetic factors. However, MS is thought to primarily be an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the myelin in the brain and optic nerves, as well as the nerve cell bodies in the brain’s gray matter.[2] Ultimately, the outermost layer of the brain, the cerebral cortex, shrinks in size, known as cortical atrophy.[3]

Infectious factors such as measles, human herpesvirus-6, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may also be involved in the development of MS. Research indicates that a previous infection with EBV (the virus that causes mononucleosis) contributes to the risk of developing MS.[4]

Genetic factors can also contribute to the development of MS. The risk of developing MS increases if first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, and offspring) have been diagnosed with MS.[5]

MS occurs more frequently in populations that live farther from the equator. Low vitamin D levels in the blood have been identified as a risk factor for the development of MS. Sun exposure (the natural source of vitamin D) may help to explain the northern distribution of MS.

Smoking increases a person’s risk for developing MS and is associated with rapid, severe disease progression. Smoking cessation before or after the onset of MS is associated with a slower progression of disability.

Types of MS

There are four major types of MS[6]:

- Relapsing-remitting: This is the most common type of MS. Exacerbations are “attacks” that cause new or worsening neurological symptoms. These attacks are also called relapses or exacerbations. They are followed by periods of partial or complete recovery (remission). In remissions, all symptoms may disappear, or some symptoms may continue and become permanent. However, during those periods of remission, the disease does not seem to progress.

- Primary progressive: This type causes a steady and gradual neurologic deterioration without remission of symptoms. Typically, clients do not manifest “acute attacks.”

- Secondary progressive: Some people develop a secondary progressive type after initially following the relapsing-remitting course. In the secondary progressive type, neurologic function and disability worsen progressively over time.

- Progressive-relapsing: This type is different from the relapsing-remitting type in that clients may have frequent relapses with partial recovery, but they do not return to baseline. Deterioration tends to occur over several years.

Assessment

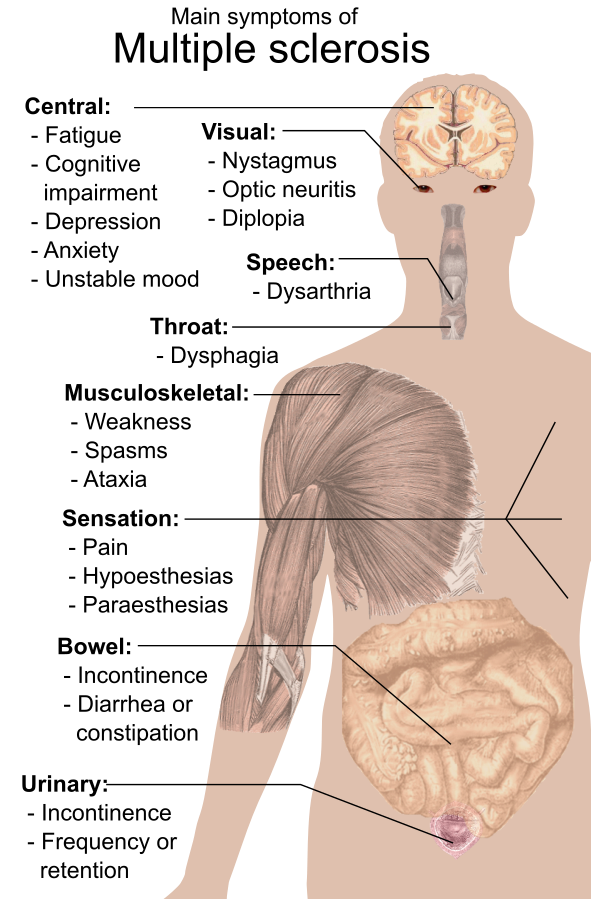

Multiple sclerosis can act like many other neurologic diseases. There are a variety of potential manifestations of MS based on the location of the lesions and any periods of remission. It is important to collect a thorough history regarding the progression of symptoms and if they are constant or intermittent or if they are becoming increasingly worse. Ask about any aggravating factors that may trigger symptoms, such as fatigue, stress, or temperature extremes. In most instances, symptoms of MS are vague and nonspecific particularly in the early stages. Common initial symptoms are unilateral visual loss and associated visual changes such as blurred vision, diplopia, nystagmus (uncontrolled, repetitive movements of the eyes), and sometimes patchy blindness. Other symptoms of MS are summarized in the following box. See Figure 9.28[7] for an illustration of common symptoms of MS.

Signs and Symptoms of MS

- Visual and eye disturbances

- Fatigue, often worse in afternoon hours

- Muscle weakness

- Hypoesthesias (numbness)

- Paresthesias (tingling, numbness, itching, or burning)

- Pain (if lesions are on sensory pathways)

- Muscle spasticity in the extremities

- Ataxia (lack of coordination)

- Dysmetria (inability to direct or limit movement)

- Intention tremors (tremors while performing an activity, compared to resting tremors that occur during Parkinson’s disease)

- Dysarthria (difficulty speaking due to weak muscles)

- Tinnitus

- Vertigo

- Bowel and bladder dysfunction

- Partial or complete paralysis

- Alterations in sexual function, such as impotence

- Cognitive changes such as impaired judgment, memory loss, and decreased ability to problem solve

- Psychosocial or behavioral changes (depression, anxiety, irritability, euphoria, apathy, social isolation)

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

A combination of these tests is performed to diagnose MS in association with the client’s clinical presentation:

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis: Abnormally elevated proteins, increased white blood cells, increased myelin basic proteins, and increased immunoglobulins (especially IgG).

- MRI of the brain and spinal cord: Lesion formation in at least two areas is diagnostic for MS.

- Visual evoked potential test: Noninvasively invoking a visual response identifies impaired transmission along the optic nerve pathway.

View an animated image[8] of monthly MRIs that demonstrate exacerbation and remission of lesions:

Nursing Diagnoses

Priority nursing diagnoses for clients with MS may include the following[9]:

- Impaired Physical Mobility

- Fatigue

- Activity Intolerance

- Impaired Communication

- Ineffective Coping

- Anxiety

Outcome Identification

Overall goals for clients with MS include optimal levels of physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning:

- Minimize the frequency and severity of symptoms and relapses associated with MS, including fatigue, muscle weakness, and sensory disturbances

- Improve or maintain the client’s mobility and independence

- Promote emotional well-being

- Prevent complications such as falls, infections, and ulcers

- Enhance the overall quality of life for individuals with MS, encouraging them to participate in meaningful activities and relationships

Sample outcome criteria for clients with MS include the following:

- The client will identify four strategies for managing fatigue after the teaching session.

- The client will participate in two recommended mobility treatment programs within the next month.

- The client will report an improved sense of energy scoring at least 5 on 1-10 energy rating scale (10 being the highest level of energy, 1 being the lowest level).

Interventions

Clients with MS require multidisciplinary care due to the complexity of care and the variation of the disease and treatment.

Symptomatic management focuses on muscle spasticity, fatigue, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and ataxia. Physical and occupational therapy for clients with MS include range-of-motion exercises, ambulation within their abilities, positioning, and transferring. Other interventions include cognitive-behavioral therapy and vocational rehabilitation.

Medical Interventions

Medication Therapy

There is no cure for MS; therefore, the goals of medical treatment are to prevent and treat acute exacerbations, delay the progression of the disease, and manage chronic symptoms. There are a variety of medications used to treat and control the disease progression in clients with MS. The majority of the medications are immunomodulators or anti-inflammatory drugs. Both types of medication can affect the immune system and increase their risk for secondary infection. Muscle relaxants may be prescribed to reduce muscle spasticity, which can contribute to pain. Paresthesias may be treated with anticonvulsants or tricyclic antidepressants. Constipation from bowel dysfunction may be treated with stool softeners and laxatives as part of a bowel management program. Bladder dysfunction may be treated with antispasmodics (such as baclofen) or bladder relaxing medications (such as oxybutynin and tolterodine). See Table 9.10 for a summary of common medications used to manage MS.

Table 9.10. Common Medications for Management of Multiple Sclerosis

| Medication | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

| Interferon-beta preparations (immunomodulator) | Reduces progression of disease and has antiviral effects. |

| Glatiramer acetate | A synthetic protein similar to myelin used to decrease the number of plaques and increase time between relapses. |

| IV antineoplastic (mitoxantrone) | An anti-inflammatory agent used to resolve relapses and reduce neurologic disability. |

| IV monoclonal antibody (natalizumab) | Binds to WBCs to prevent further damage to the myelin. |

| Fingolimod, teriflunomide, and dimethyl fumarate | Protect brain and spinal cord cells by inhibiting immune cells and providing antioxidants. |

| Baclofen or tizanidine | Muscle relaxant used to reduce muscle spasticity. |

| Anticonvulsant (carbamazepine) or tricyclic antidepressant (amitriptyline) | Reduce paresthesia. |

| Propranolol and clonazepam | Treat cerebellar ataxia. |

| Corticosteroids | Treat acute relapses. Shorten duration by exerting anti-inflammatory effects and acting on T cells and cytokines. |

Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, and Speech Therapy

Referral to physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy are part of the collaborative effort to provide therapies for optimal function. Occupational and physical therapists can develop exercise programs to assist the client with stretching and strengthening to manage spasticity and tremor. The occupational therapy can also assist the client with visual deficits with scanning techniques, modifications in environment, and use of an eye patch if diplopia is present. Speech therapists can help people who have difficulty speaking to communicate effectively and strengthen the muscles used in speech.

Surgical Interventions

In severe cases, neurosurgery or deep brain stimulation may be performed to provide relief from tremors.

Nursing Interventions

As with medical management, therapeutic interventions and nursing actions for clients with multiple sclerosis focus on promoting optimal mobility and function, prevention of exacerbations and complications, management of symptoms, and achieving optimal well-being. See the following box for an overview of nursing interventions.

Nursing Interventions for Clients with MS[10]

- Encourage independent activity independence to stay active as long as possible to maintain their strength.

- Implement energy conservation techniques to manage fatigue. Encourage clients to cluster their activities and provide frequent rest periods to conserve their energy for important tasks. Keep frequently used items in familiar places.

- Provide health teaching on bowel and bladder training. Include scheduled toileting to minimize and avoid incontinence.

- Ensure adequate fluid intake of 2,000-3,000 mL/day.

- Check the temperature of bath water and heating pads. Encourage clients to lower the maximum temperature on water heaters at home to prevent burns.

- Implement fall precautions in the home (remove rugs and clutter).

- Encourage daily exercises, including stretching and strengthening.

- Encourage independent activity to stay active for as long as possible and to maintain strength.

- Assess skin breakdown that may occur due to immobility and incontinence.

- Avoid vigorous activities that increase body temperature. Increased body temperature may lead to exacerbations (relapses), increased fatigue, diminished motor ability, and decreased visual acuity.

- Use eye patches for diplopia and alternate every few hours.

- Promote adequate rest and stress management techniques.

- Encourage participation in social activities to prevent social isolation.

- Refer to MS support groups to promote effective coping.

Health Promotion & Teaching

The effects of MS can be physically and mentally debilitating. Nurses provide support, education, and advocacy for clients and families affected by this disease. They each the client and their caregiver about the purpose of medications, side effects, and therapeutic response, and encourage calling the health care provider if questions or problems with medications occur.

Nurses also ensure the client understands techniques for self-care, daily life skills, and the use of any adaptive equipment. Information on bowel and bladder management, nutrition, and skin care is provided. MS affects the entire family mainly due to its unpredictability and uncertainty of the course, so nurses assist family members in identifying support systems and refer them to additional counseling as indicated.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with a family member or other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Multiple Sclerosis

RN Recap: Multiple Sclerosis

View a brief YouTube video overview of multiple sclerosis[11]:

- “Myelin_sheath_damage_in_multiple_sclerosis.svg" by Mjeltsch is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Multiple sclerosis. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/multiple-sclerosis ↵

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (n.d.). What causes MS? https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/What-Causes-MS ↵

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (n.d.). What causes MS? https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/What-Causes-MS ↵

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (n.d.). What causes MS? https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/What-Causes-MS ↵

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (n.d.). What causes MS? https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/What-Causes-MS ↵

- “Symptoms_of_multiple_sclerosis.svg” by Mikael Häggström is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “Monthly_multiple_sclerosis_anim_bg.gif” by Gabby8228 (talk) is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 7 multiple sclerosis nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/multiple-sclerosis-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 9 - Multiple sclerosis [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/39MQWk-h1B4?si=ZG9_2o0Kki1C1gYL ↵

Angiogenesis: The development of new capillaries in a wound base.

Arterial ulcers: Ulcers caused by lack of blood flow and oxygenation to tissues and typically occur in the distal areas of the body such as the feet, heels, and toes.

Debridement: The removal of nonviable tissue in a wound.

Dehiscence: The separation of the edges of a surgical wound.

Diabetic ulcers: Ulcers that typically develop on the plantar aspect of the feet and toes of patients with diabetes due to lack of sensation of pressure or injury.

Ecchymosis: Bruising that occurs when small veins and capillaries under the skin break.

Edema: Swelling.

Epithelialization: The development of new epidermis and granulation tissue.

Erythema: Redness.

Eschar: Dark brown/black, dry, thick, and leathery dead tissue in a wound base that must be removed for healing to occur.

Exudate: Fluid that oozes out of a wound; also commonly called pus.

Granulation tissue: New connective tissue in a wound base with fragile, thin-walled capillaries that must be protected.

Hematoma: An area of blood that collects outside of larger blood vessels.

Hemosiderin staining: Dark-colored discoloration of the lower legs due to blood pooling.

Hemostasis phase: The first phase of wound healing that occurs immediately after skin injury. Blood vessels constrict and clotting factors are activated.

Induration: Area of hardened tissue.

Inflammatory phase: The second phase of wound healing when vasodilation occurs so that white blood cells in the bloodstream can move into the wound to start cleaning the wound bed.

Maceration: The softening and wasting away of skin due to excess fluid.

Maturation phase: The final phase of wound healing as collagen continues to be created to strengthen the wound, causing scar tissue.

Necrotic: Black tissue color due to tissue death from lack of oxygenation to the area.

Nonblanchable erythema: Skin redness that does not turn white when pressure is applied.

Osteomyelitis: Bone infection.

Peripheral neuropathy: A condition that causes decreased sensation of pain and pressure, typically in the lower extremities.

Periwound: The skin around the outer edges of a wound.

Pressure injuries: Localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.[1]

Primary intention: Wound healing that occurs with surgical incisions or clean-edged lacerations that are closed with sutures, staples, or surgical glue.

Proliferative phase: The third phase of wound healing that includes epithelialization, angiogenesis, collagen formation, and contraction.

Purulent drainage: Wound exudate that is thick and opaque and can be tan, yellow, green, or brown in color. It is never considered normal in a wound, and new purulent drainage should always be reported to the health care provider.

Sanguineous drainage: Wound drainage that is fresh bleeding.

Secondary intention: Wound healing that occurs when the edges of a wound cannot be approximated (brought together), so the wound fills in from the bottom up by the production of granulation tissue. Examples of wounds that heal by secondary intention are pressure injuries and chainsaw injuries.

Serosanguinous drainage: Wound exudate contains serous drainage with small amounts of blood present.

Serous drainage: Wound drainage that is clear, thin, watery plasma. It is considered normal in minimal amounts during the inflammatory stage of wound healing.

Shear: A mechanical force that occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue.

Skin tears: Wounds caused by mechanical forces, typically in the nonelastic skin of older adults.

Slough: Inflammatory exudate that is light yellow, soft, and moist and must be removed for wound healing to occur.

Tertiary intention: Wound healing that occurs when a wound must remain open or has been reopened, often due to severe infection.

Tunneling: Passageways underneath the surface of the skin that extend from a wound and can take twists and turns.

Undermining: A condition that occurs in wounds when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound's edge.

Unstageable: Occurs when slough or eschar obscures the wound so that tissue loss cannot be assessed.

Venous insufficiency: A medical condition where the veins in the legs do not adequately send blood back to the heart, resulting in a pooling of fluids in the legs that can cause venous ulcers.

Venous ulcers: Ulcers caused by the pooling of fluid in the veins of the lower legs when the valves are not working properly, causing fluid to seep out, macerate the skin, and cause an ulcer.

Wound vac: A device used with special foam dressings and suctioning to remove fluid and decrease air pressure around a wound to assist in healing.

Learning Objectives

- Perform urinary catheterization, ostomy care, and urine specimen collection

- Manage urinary catheters to prevent complications

- Maintain aseptic or sterile technique

- Explain procedure to patient

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

Elimination is a basic human function of excreting waste through the bowel and urinary system. The process of elimination depends on many variables and intricate processes that occur within the body. Many medical conditions and surgeries can adversely affect the processes of elimination, so nurses must facilitate their patients’ bowel and urinary elimination as needed. Common nursing interventions related to facilitating elimination include inserting and managing urinary catheters, obtaining urine specimens, caring for ostomies, providing patient education to promote healthy elimination, and preventing complications. In this chapter, we will discuss the technical skills used to support bowel and bladder function, as well as the application of the nursing process while doing so.

Before discussing specific procedures related to facilitating bowel and bladder function, let’s review basic concepts related to urinary and bowel elimination. When facilitating alternative methods of elimination, it is important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems, as well as the adverse effects of various conditions and medications on elimination. Use the information below to review information about these topics.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system and medications used to treat diarrhea and constipation, visit the "Gastrointestinal" chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the kidneys and diuretic medications used to treat fluid overload, visit the "Cardiovascular and Renal System" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about applying the nursing process to facilitate elimination, visit the "Elimination" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Urinary Elimination Devices

This section will focus on the devices used to facilitate urinary elimination. Urinary catheterization is the insertion of a catheter tube into the urethral opening and placing it in the neck of the urinary bladder to drain urine. There are several types of urinary elimination devices, such as indwelling catheters, intermittent catheters, suprapubic catheters, and external devices. Each of these types of devices is described in the following subsections.

Indwelling Catheter

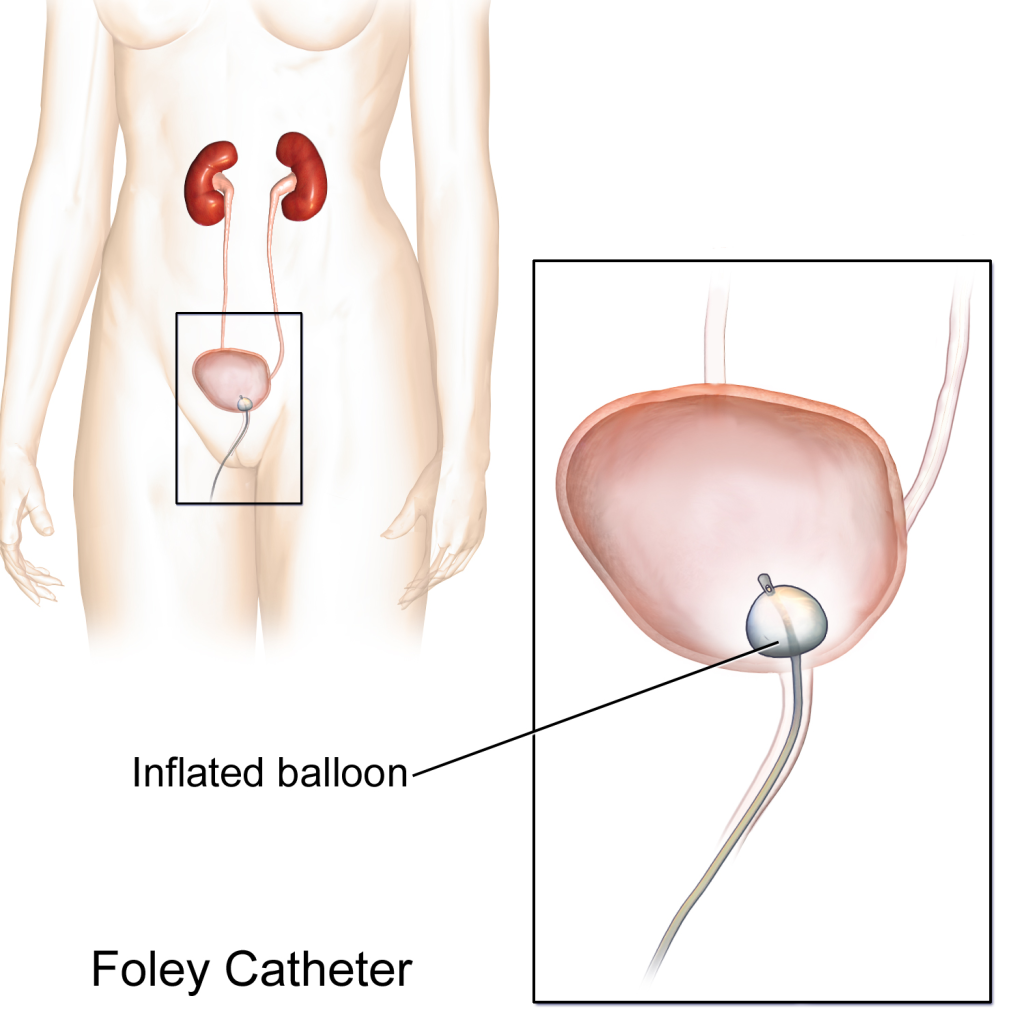

An indwelling catheter, often referred to as a “Foley catheter,” refers to a urinary catheter that remains in place after insertion into the bladder for the continual collection of urine. It has a balloon on the insertion tip to maintain placement in the neck of the bladder. The other end of the catheter is attached to a drainage bag for the collection of urine. See Figure 21.1[2] for an illustration of the anatomical placement of an indwelling catheter in the bladder neck.

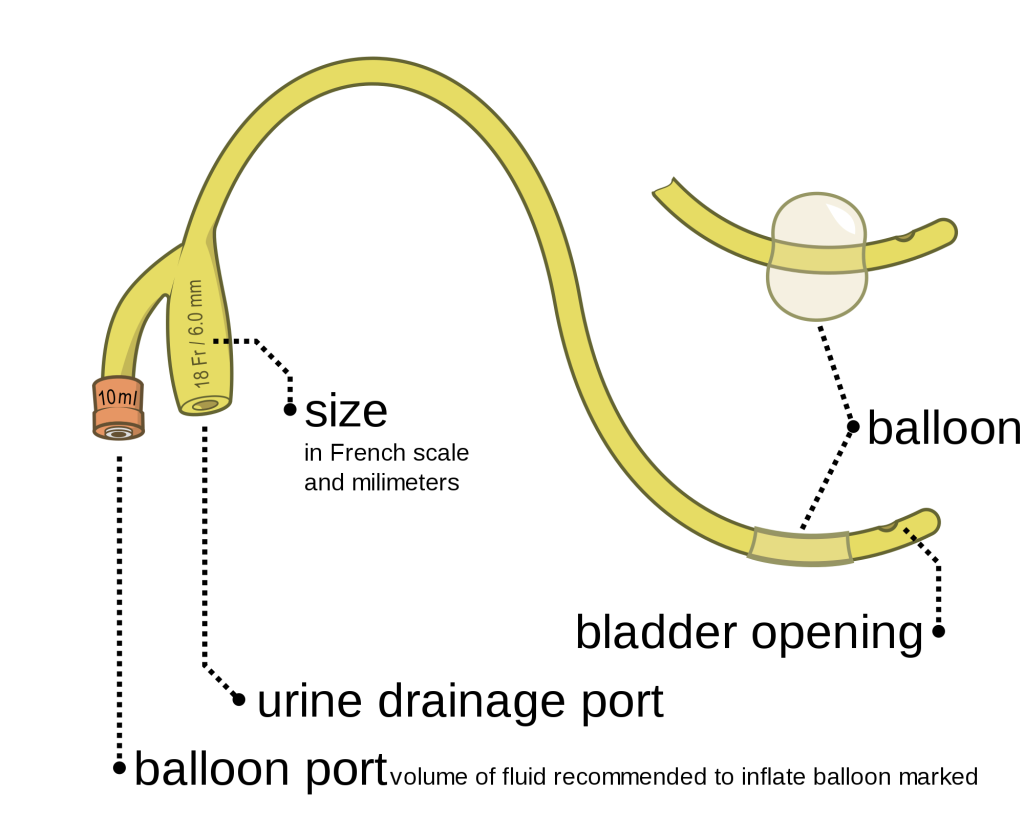

The distal end of an indwelling catheter has a urine drainage port that is connected to a drainage bag. The size of the catheter is marked at this end using the French catheter scale. A balloon port is also located at this end, where a syringe is inserted to inflate the balloon after it is inserted into the bladder. The balloon port is marked with the amount of fluid required to fill the balloon. See Figure 21.2[3] for an image of the parts of an indwelling catheter.

Catheters have different sizes, with the larger the number indicating a larger diameter of the catheter. See Figure 21.3[4] for an image of the French catheter scale.

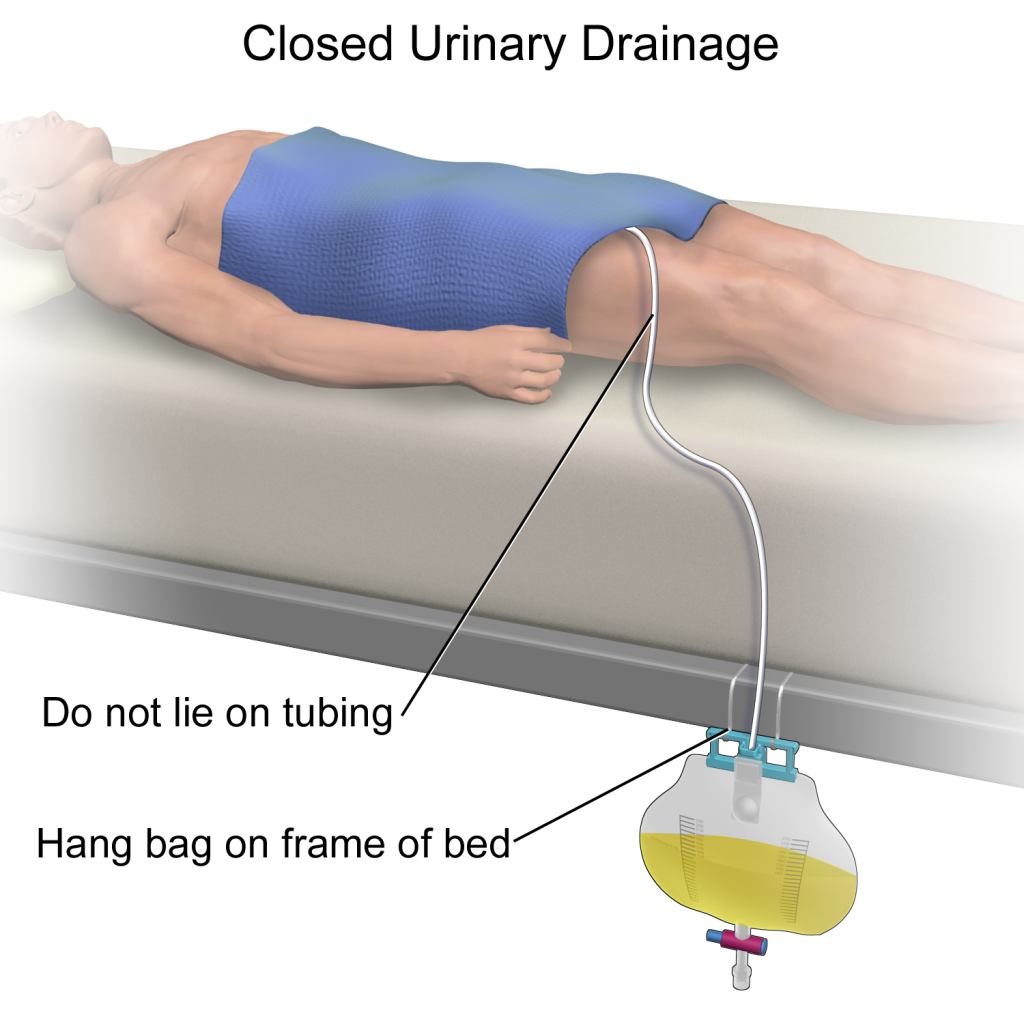

There are two common types of bags that may be attached to an indwelling catheter. During inpatient or long-term care, larger collection bags that can hold up to two liters of fluid are used. See Figure 21.4[5] for an image of a typical collection bag attached to an indwelling catheter. These bags should be emptied when they are half to two-thirds full to prevent traction on the urethra from the bag. Additionally, the collection bag should always be placed below the level of the patient’s bladder so that urine flows out of the bladder and urine does not inadvertently flow back into the bladder. Ensure the tubing is not coiled, kinked, or compressed so that urine can flow unobstructed into the bag. Slack should be maintained in the tubing to prevent injury to the patient's urethra. To prevent the development of a urinary tract infection, the bag should not be permitted to touch the floor.

See Figure 21.5[6] for an illustration of the placement of the urine collection bag when the patient is lying in bed.

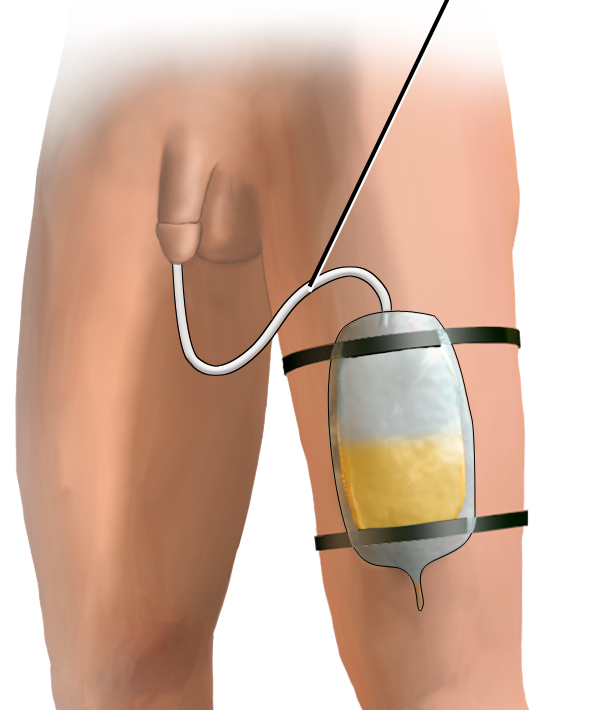

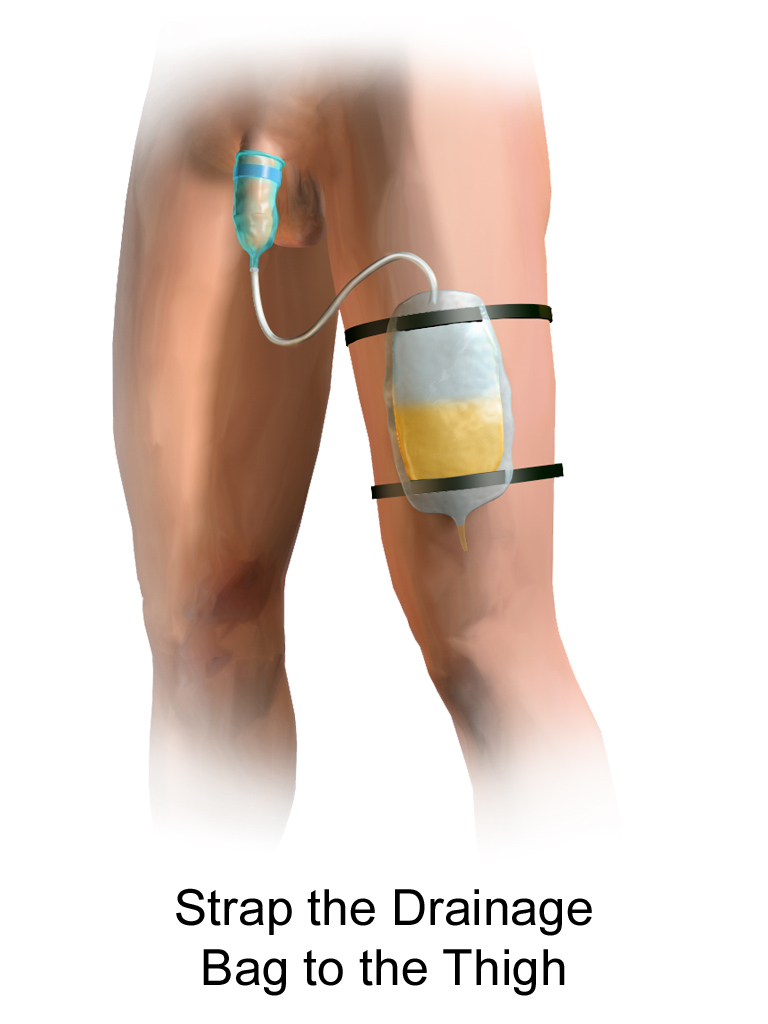

A second type of urine collection bag is a leg bag. Leg bags provide discretion when the patient is in public because they can be worn under clothing. However, leg bags are small and must be emptied more frequently than those used during inpatient care. Figure 21.6[7] for an image of leg bag and Figure 21.7[8] for an illustration of an indwelling catheter attached to a leg bag.

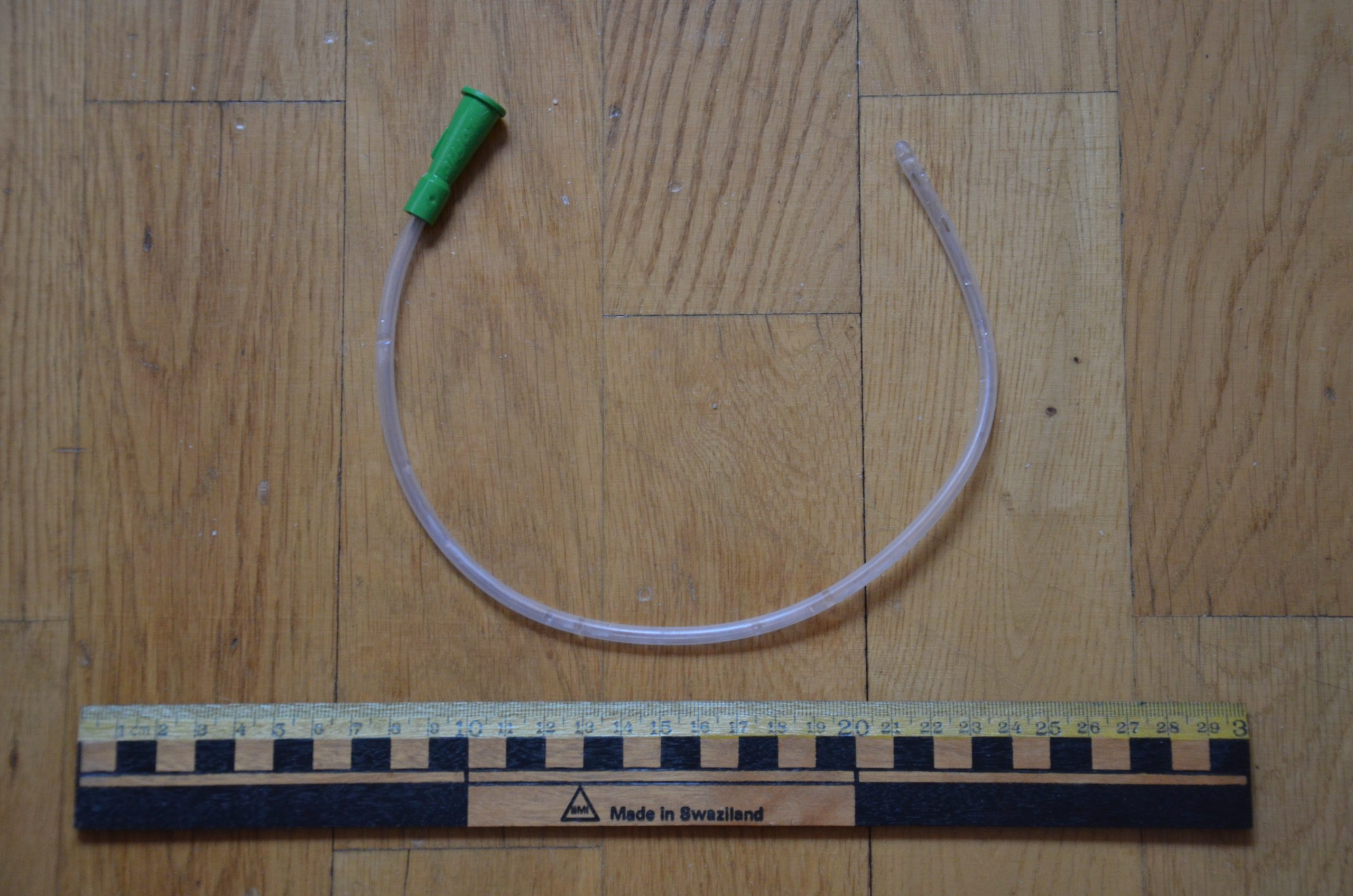

Straight Catheter

A straight catheter is used for intermittent urinary catheterization. The catheter is inserted to allow for the flow of urine and then immediately removed, so a balloon is not required at the insertion tip. See Figure 21.8[9] for an image of a straight catheter. Intermittent catheterization is used for the relief of urinary retention. It may be performed once, such as after surgery when a patient is experiencing urinary retention due to the effects of anesthesia, or performed several times a day to manage chronic urinary retention. Some patients may also independently perform self-catheterization at home to manage chronic urinary retention caused by various medical conditions. In some situations, a straight catheter is also used to obtain a sterile urine specimen for culture when a patient is unable to void into a sterile specimen cup. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), intermittent catheterization is preferred to indwelling urethral catheters whenever feasible because of decreased risk of developing a urinary tract infection.[10]

Other Types of Urinary Catheters

Coude Catheter Tip

Coude catheter tips are curved to follow the natural curve of the urethra during catheterization. They are often used when catheterizing male patients with enlarged prostate glands. See Figure 21.9[11] for an example of a urinary catheter with a coude tip. During insertion, the tip of the coude catheter must be pointed anteriorly or it can cause damage to the urethra. A thin line embedded in the catheter provides information regarding orientation during the procedure; maintain the line upwards to keep it pointed anteriorly.

Irrigation Catheter

Irrigation catheters are typically used after prostate surgery to flush the surgical area. These catheters are larger in size to allow for irrigation of the bladder to help prevent the formation of blood clots and to flush them out. See Figure 21.10[12] for an image comparing a larger 20 French catheter (typically used for irrigation) to a 14 French catheter (typically used for indwelling catheters).

Suprapubic Catheters

Suprapubic catheters are surgically inserted through the abdominal wall into the bladder. This type of catheter is typically inserted when there is a blockage within the urethra that does not allow the use of a straight or indwelling catheter. Suprapubic catheters may be used for a short period of time for acute medical conditions or may be used permanently for chronic conditions. See Figure 21.11[13] for an image of a suprapubic catheter. The insertion site of a suprapubic catheter must be cleaned regularly according to agency policy with appropriate steps to prevent skin breakdown.

Male Condom Catheter

A condom catheter is a noninvasive device used for males with incontinence. It is placed over the penis and connected to a drainage bag. This device protects and promotes healing of the skin around the perineal area and inner legs and is used as an alternative to an indwelling urinary catheter. See Figure 21.12[14] for an image of a condom catheter and Figure 21.13[15] for an illustration of a condom catheter attached to a leg bag.

Female External Urinary Catheter

Female external urinary catheters (FEUC) have been recently introduced into practice to reduce the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) in women.[16] The external female catheter device is made of a purewick material that is placed externally over the female’s urinary meatus. The wicking material is attached to a tube that is hooked to a low-suction device. When the wick becomes saturated with urine, it is suctioned into a drainage canister. Preliminary studies have found that utilizing the FEUC device reduced the risk for CAUTI.[17],[18]

View these supplementary YouTube videos on female external urinary catheters:

Students demonstrate use of PureWick female external catheter[19]

How to use the use the PureWick - a female external catheter[20]

Safely and accurately placing an indwelling urinary catheter poses several challenges that require the nurse to use clinical judgment. Challenges can include anatomical variations in a specific patient, medical conditions affecting patient positioning, and maintaining sterility of the procedure with confused or agitated patients. See the checklists on Foley Catheter Insertion (Male) and Foley Catheter Insertion (Female) for detailed instructions.

Nursing interventions to prevent the development of a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) on insertion include the following[21]:

- Determine if insertion of an indwelling catheter meets CDC guidelines.

- Select the smallest-sized catheter that is appropriate for the patient, typically a 14 French.

- Obtain assistance as needed to facilitate patient positioning, visualization, and insertion. Many agencies require two nurses for the insertion of indwelling catheters.

- Perform perineal care before inserting a urinary catheter and regularly thereafter.

- Perform hand hygiene before and after insertion, as well as during any manipulation of the device or site.

- Maintain strict aseptic technique during insertion and use sterile gloves and equipment.

- Inflate the balloon after insertion per manufacturer instructions. It is not recommended to preinflate the balloon prior to insertion.

- Properly secure the catheter after insertion to prevent tissue damage.

- Keep the drainage bag below the bladder but not resting on the floor.

- Check the system to ensure there are no kinks or obstructions to urine flow.

- Provide routine hygiene of the urinary meatus during daily bathing and cleanse the perineal area after every bowel movement. In uncircumcised males, gently retract the foreskin, cleanse the meatus, and then return the foreskin to the original position. Do not cleanse the periurethral area with antiseptics after the catheter is in place.[22] To avoid contaminating the urinary tract, always clean by wiping away from the urinary meatus.

- Empty the collection bag regularly using a separate, clean collecting container for each patient. Avoid splashing and prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the nonsterile collecting container or other surfaces. Never allow the bag to touch the floor.[23],[24]

Video Review of Thompson Rivers University's Urinary Catheterization:

If a small amount of a fresh urine is needed for specimen collection for urinalysis or culture, aspirate the urine from the needleless sampling port with a sterile syringe after cleansing the port with a disinfectant.[27] See the "Checklist for Obtaining a Urine Specimen from a Foley Catheter" for more detailed instructions. Do not collect the urine that is already in the collection bag because it is contaminated and will lead to an erroneous test result.

It is the nurse’s responsibility to assess for a patient’s continued need for an indwelling catheter daily and to advocate for removal when appropriate.[28] Prolonged use of indwelling catheters increases the risk of developing CAUTIs. For patients who require an indwelling catheter for operative purposes, the catheter is typically removed within 24 hours or less. Some agencies have a protocol for the removal of indwelling catheters, whereas others require a prescription from a provider. For additional instructions about how to remove an indwelling catheter, see the "Checklist for Foley Removal."

When removing an indwelling urinary catheter, it is considered a standard of practice to document the time and track the time of the first void. This information is also communicated during handoff reports. If the patient is unable to void within 4-6 hours and/or complains of bladder fullness, the nurse determines if incomplete bladder emptying is occurring according to agency policy. The ANA has made the following recommendations to assess for incomplete bladder emptying:

- The patient should be prompted to urinate.

- If urination volume is less than 180 mL, the nurse should perform a bladder scan to determine the post-void residual. A bladder scan is a bedside test performed by nurses that uses ultrasonic waves to determine the amount of fluid in the bladder.

- If a bladder scanner is not available, a straight urinary catheterization is performed.[29]

When a urinary catheter is removed, instruct the patient on the following guidelines:

- Increase or maintain fluid intake (unless contraindicated).

- Void when able with the goal to urinate within six hours after removal of the catheter. Inform the nurse of the void so that the amount can be measured and documented.

- Be aware that there may be a mild burning sensation during the first void.

- Report any burning, discomfort, frequency, or small amounts of urine when voiding.

- Report an inability to void, bladder tenderness, or distension.

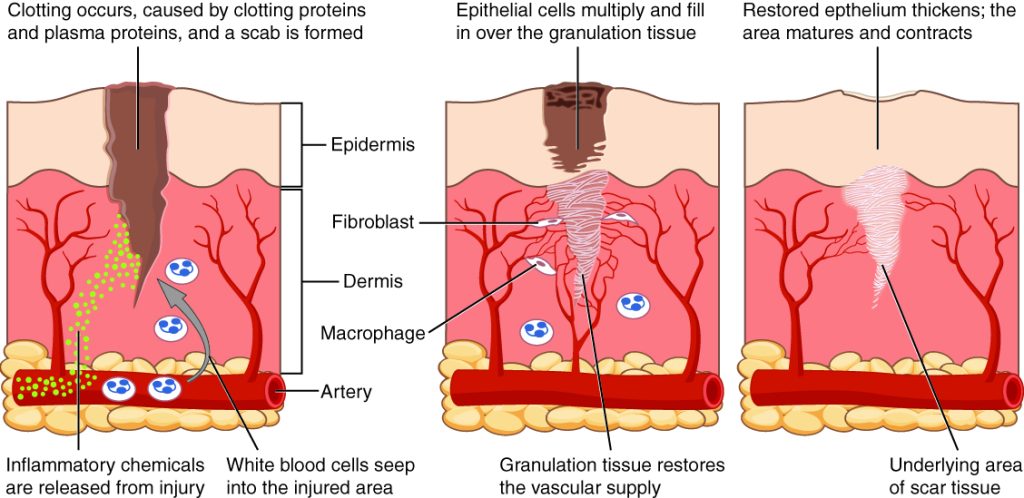

Phases of Wound Healing

When skin is injured, there are four phases of wound healing that take place: hemostasis, inflammatory, proliferative, and maturation.[30] See Figure 20.1[31] for an illustration of the phases of wound healing.

To illustrate the phases of wound healing, imagine that you accidentally cut your finger with a knife as you were slicing an apple. Immediately after the injury occurs, blood vessels constrict, and clotting factors are activated. This is referred to as the hemostasis phase. Clotting factors form clots that stop the bleeding and act as a barrier to prevent bacterial contamination. Platelets release growth factors that alert various cells to start the repair process at the wound location. The hemostasis phase lasts up to 60 minutes, depending on the severity of the injury.[32],[33]

After the hemostasis phase, the inflammatory phase begins. Vasodilation occurs so that white blood cells in the bloodstream can move into the wound to start cleaning the wound bed. The inflammatory process appears to the observer as edema (swelling), erythema (redness), and exudate. Exudate is fluid that oozes out of a wound, also commonly called pus.[34],[35]

The proliferative phase begins within a few days after the injury and includes four important processes: epithelialization, angiogenesis, collagen formation, and contraction. Epithelialization refers to the development of new epidermis and granulation tissue. Granulation tissue is new connective tissue with new, fragile, thin-walled capillaries. Collagen is formed to provide strength and integrity to the wound. At the end of the proliferation phase, the wound begins to contract in size.[36],[37]

Capillaries begin to develop within the wound 24 hours after injury during a process called angiogenesis. These capillaries bring more oxygen and nutrients to the wound for healing. When performing dressing changes, it is essential for the nurse to protect this granulation tissue and the associated new capillaries. Healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is also moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered by shiny white or yellow fibrous tissue referred to as biofilm that must be removed because it impedes healing. Unhealthy granulation tissue is often caused by an infection, so wound cultures should be obtained when infection is suspected. The provider can then prescribe appropriate antibiotic treatment based on the culture results.[38]

During the maturation phase, collagen continues to be created to strengthen the wound. Collagen contributes strength to the wound to prevent it from reopening. A wound typically heals within 4-5 weeks and often leaves behind a scar. The scar tissue is initially firm, red, and slightly raised from the excess collagen deposition. Over time, the scar begins to soften, flatten, and become pale in about nine months.[39]

Types of Wound Healing

There are three types of wound healing: primary intention, secondary intention, and tertiary intention. Healing by primary intention means that the wound is sutured, stapled, glued, or otherwise closed so the wound heals beneath the closure. This type of healing occurs with clean-edged lacerations or surgical incisions, and the closed edges are referred to as approximated. See Figure 20.2[40] for an image of a surgical wound healing by primary intention.

Secondary intention occurs when the edges of a wound cannot be approximated (brought together), so the wound fills in from the bottom up by the production of granulation tissue. Examples of wounds that heal by secondary intention are pressure injuries and chainsaw injuries. Wounds that heal by secondary intention are at higher risk for infection and must be protected from contamination. See Figure 20.3[41] for an image of a wound healing by secondary intention.

Tertiary intention refers to a wound that has had to remain open or has been reopened, often due to severe infection. The wound is typically closed at a later date when infection has resolved. Wounds that heal by secondary and tertiary intention have delayed healing times and increased scar tissue.

Wound Closures

Lacerations and surgical wounds are typically closed with sutures, staples, or dermabond to facilitate healing by primary intention. See Figure 20.4[42] for an image of sutures, Figure 20.5[43] for an image of staples, and Figure 20.6[44] for an image of a wound closed with dermabond, a type of sterile surgical glue. Based on agency policy, the nurse may remove sutures and staples based on a provider order. See Figure 20.7[45] for an image of a disposable staple remover. See the checklists in the subsections later in this chapter for procedures related to surgical and staple removal.

Common Types of Wounds

There are several different types of wounds. It is important to understand different types of wounds when providing wound care because each type of wound has different characteristics and treatments. Additionally, treatments that may be helpful for one type of wound can be harmful for another type. Common types of wounds include skin tears, venous ulcers, arterial ulcers, diabetic foot wounds, and pressure injuries.[46]

Skin Tears

Skin tears are wounds caused by mechanical forces such as shear, friction, or blunt force. They typically occur in the fragile, nonelastic skin of older adults or in patients undergoing long-term corticosteroid therapy. Skin tears can be caused by the simple mechanical force used to remove an adhesive bandage or from friction as the skin brushes against a surface. Skin tears occur in the epidermis and dermis but do not extend through the subcutaneous layer. The wound bases of skin tears are typically fragile and bleed easily.[47]

Venous Ulcers

Venous ulcers are caused by lack of blood return to the heart causing pooling of fluid in the veins of the lower legs. The resulting elevated hydrostatic pressure in the veins causes fluid to seep out, macerate the skin, and cause venous ulcerations. Maceration refers to the softening and wasting away of skin due to excess fluid. Venous ulcers typically occur on the medial lower leg and have irregular edges due to the maceration. There is often a dark-colored discoloration of the lower legs, due to blood pooling and leakage of iron into the skin called hemosiderin staining. For venous ulcers to heal, compression dressings must be used, along with multilayer bandage systems, to control edema and absorb large amounts of drainage.[48] See Figure 20.8[49] for an image of a venous ulcer.

Arterial Ulcers

Arterial ulcers are caused by lack of blood flow and oxygenation to tissues. They typically occur in the distal areas of the body such as the feet, heels, and toes. Arterial ulcers have well-defined borders with a “punched out” appearance where there is a localized lack of blood flow. They are typically painful due to the lack of oxygenation to the area. The wound base may become necrotic (black) due to tissue death from ischemia. Wound dressings must maintain a moist environment, and treatment must include the removal of necrotic tissue. In severe arterial ulcers, vascular surgery may be required to reestablish blood supply to the area.[50] See Figure 20.9[51] for an image of an arterial ulcer on a patient’s foot.

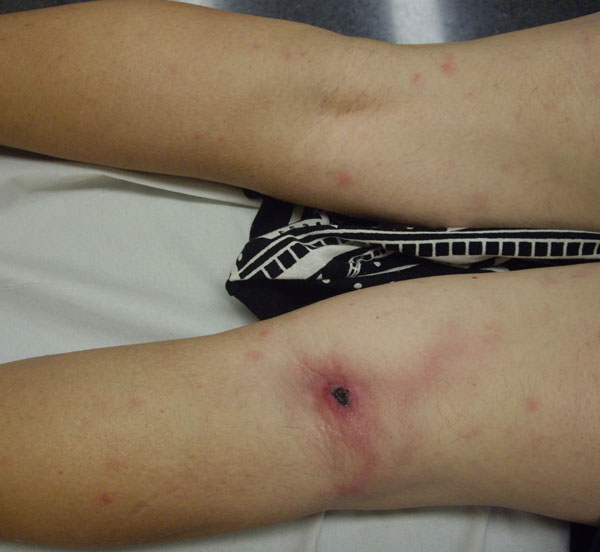

Diabetic Ulcers

Diabetic ulcers are also called neuropathic ulcers because peripheral neuropathy is commonly present in patients with diabetes. Peripheral neuropathy is a medical condition that causes decreased sensation of pain and pressure, especially in the lower extremities. Diabetic ulcers typically develop on the plantar aspect of the feet and toes of a patient with diabetes due to lack of sensation of pressure or injury. See Figure 20.10[52] for an image of a diabetic ulcer. Wound healing is compromised in patients with diabetes due to the disease process. In addition, there is a higher risk of developing an infection that can reach the bone requiring amputation of the area. To prevent diabetic ulcers from occurring, it is vital for nurses to teach meticulous foot care to patients with diabetes and encourage the use of well-fitting shoes.[53]

Pressure Injuries

Pressure injuries are defined as “localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.”[54] Shear occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue. For example, when a patient slides down in bed, the outer skin remains immobile because it remains attached to the sheets due to friction, but deeper tissue attached to the bone moves as the patient slides down. This opposing movement of the outer layer of skin and the underlying tissues causes the capillaries to stretch and tear, which then impacts the blood flow and oxygenation of the surrounding tissues.

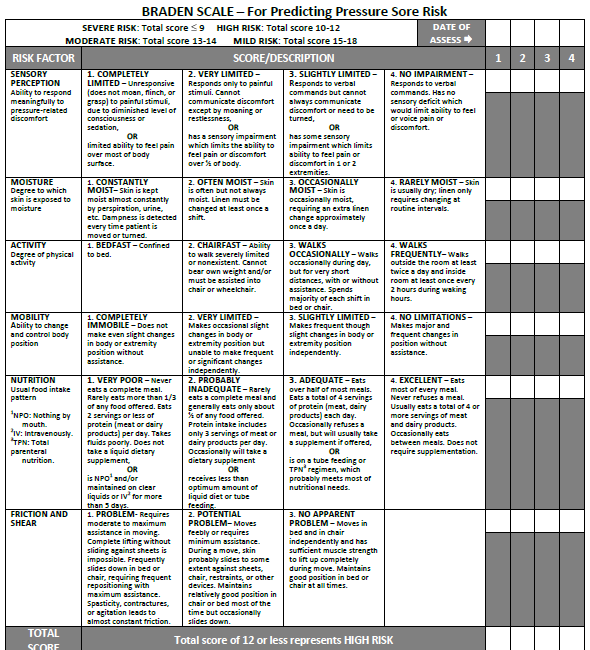

Braden Scale

Several factors place a patient at risk for developing pressure injuries, including nutrition, mobility, sensation, and moisture. The Braden Scale is a tool commonly used in health care to provide an objective assessment of a patient’s risk for developing pressure injuries. See Figure 20.11[55] for an image of a Braden Scale. The six risk factors included on the Braden Scale are sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear, and these factors are rated on a scale from 1-4 with 1 being “completely limited” to 4 being “no impairment.” The scores from the six categories are added, and the total score indicates a patient’s risk for developing a pressure injury. A total score of 15-19 indicates mild risk, 13-14 indicates moderate risk, 10-12 indicates high risk, and less than or equal to 9 indicates severe risk. Nurses create care plans using these scores to plan interventions that prevent or treat pressure injuries.

For more information about using the Braden Scale, go to the “Integumentary” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook.

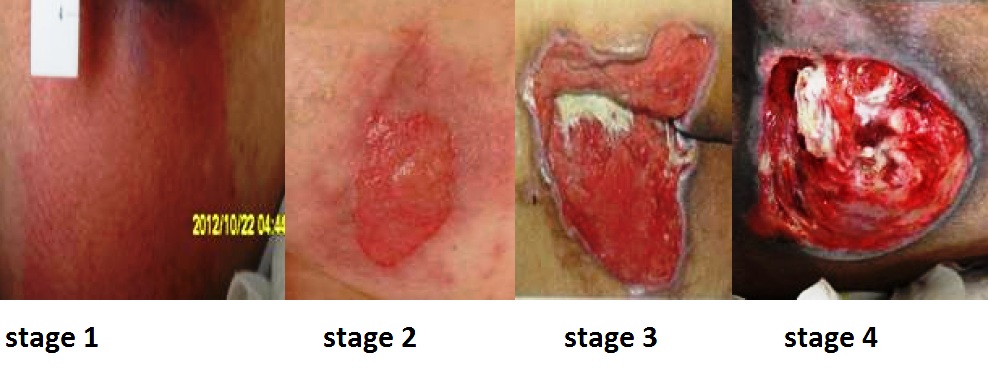

Staging

Pressure injuries commonly occur on the sacrum, heels, ischial tuberosity, and coccyx. The 2016 National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Pressure Injury Staging System now uses the term “pressure injury” instead of pressure ulcer because an injury can occur without an ulcer present. Pressure injuries are staged from 1 through 4 based on the extent of tissue damage. For example, Stage 1 pressure injuries have reddened but intact skin, and Stage 4 pressure injuries have deep, open ulcers affecting underlying tissue and structures such as muscles, ligaments, and tendons. See Figure 20.12[56] for an image of the four stages of pressure injuries.[57] The NPUAP’s definitions of the four stages of pressure injuries are described below:

- Stage 1 pressure injuries are intact skin with a localized area of nonblanchable erythema where prolonged pressure has occurred. Nonblanchable erythema is a medical term used to describe skin redness that does not turn white when pressed.

- Stage 2 pressure injuries are partial-thickness loss of skin with exposed dermis. The wound bed is viable and may appear like an intact or ruptured blister. Stage 2 pressure injuries heal by reepithelialization and not by granulation tissue formation.[58]

- Stage 3 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss in which fat is visible, but cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, and bone are not exposed. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location. Undermining and tunneling may occur in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound's edge. Tunneling refers to passageways underneath the surface of the skin that extend from a wound and can take twists and turns. Slough and eschar may also be present in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Slough is an inflammatory exudate that is usually light yellow, soft, and moist. Eschar is dark brown/black, dry, thick, and leathery dead tissue. See Figure 20.13 [59] for an image of eschar in the center of the wound. If slough or eschar obscures the wound so that tissue loss cannot be assessed, the pressure injury is referred to as unstageable.[60] In most wounds, slough and eschar must be removed by debridement for healing to occur.

- Stage 4 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss like Stage 3 pressure injuries, but also have exposed cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, or bone. Osteomyelitis (bone infection) may be present.[61]

View a supplementary YouTube video on Pressure Injuries[62]

Factors Affecting Wound Healing

Multiple factors affect a wound’s ability to heal and are referred to as local and systemic factors. Local factors refer to factors that directly affect the wound, whereas systemic factors refer to the overall health of the patient and their ability to heal. Local factors include localized blood flow and oxygenation of the tissue, the presence of infection or a foreign body, and venous sufficiency. Venous insufficiency is a medical condition where the veins in the legs do not adequately send blood back to the heart, resulting in a pooling of fluids in the legs.[63]

Systemic factors that affect a patient’s ability to heal include nutrition, mobility, stress, diabetes, age, obesity, medications, alcohol use, and smoking.[64] When a nurse is caring for a patient with a wound that is not healing as anticipated, it is important to further assess for the potential impact of these factors:

- Nutrition. Nutritional deficiencies can have a profound impact on healing and must be addressed for chronic wounds to heal. Protein is one of the most important nutritional factors affecting wound healing. For example, in patients with pressure injuries, 30 to 35 kcal/kg of calorie intake with 1.25 to 1.5g/kg of protein and micronutrients supplementation is recommended daily.[65] In addition, vitamin C and zinc deficiency have many roles in wound healing. It is important to collaborate with a dietician to identify and manage nutritional deficiencies when a patient is experiencing poor wound healing.[66]

- Stress. Stress causes an impaired immune response that results in delayed wound healing. Although a patient cannot necessarily control the amount of stress in their life, it is possible to control one’s reaction to stress with healthy coping mechanisms. The nurse can help educate the patient about healthy coping strategies.

- Diabetes. Diabetes causes delayed wound healing due to many factors such as neuropathy, atherosclerosis (a buildup of plaque that obstructs blood flow in the arteries resulting in decreased oxygenation of tissues), a decreased host immune resistance, and increased risk for infection.[67] Read more about neuropathy and diabetic ulcers under the “Common Types of Wounds” subsection. Nurses provide vital patient education to patients with diabetes to effectively manage the disease process for improved wound healing.

- Age. Older adults have an altered inflammatory response that can impair wound healing. Nurses can educate patients about the importance of exercise for improved wound healing in older adults.[68]

- Obesity. Obese individuals frequently have wound complications, including infection, dehiscence, hematoma formation, pressure injuries, and venous injuries. Nurses can educate patients about healthy lifestyle choices to reduce obesity in patients with chronic wounds.[69]

- Medications. Medications such as corticosteroids impair wound healing due to reduced formation of granulation tissue.[70] When assessing a chronic wound that is not healing as expected, it is important to consider the side effects of the patient’s medications.

- Alcohol consumption. Research shows that exposure to alcohol impairs wound healing and increases the incidence of infection.[71] Patients with impaired healing of chronic wounds should be educated to avoid alcohol consumption.

- Smoking. Smoking impacts the inflammatory phase of the wound healing process, resulting in poor wound healing and an increased risk of infection.[72] Patients who smoke should be encouraged to stop smoking.

Lab Values Affecting Wound Healing

When a chronic wound is not healing as expected, laboratory test results may provide additional clues regarding the causes of the delayed healing. See Table 20.2 for lab results that offer clues to systemic issues causing delayed wound healing.[73]

Table 20.2 Lab Values Associated with Delayed Wound Healing[74]

| Abnormal Lab Value | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Low hemoglobin | Low hemoglobin indicates less oxygen is transported to the wound site. |

| Elevated white blood cells (WBC) | Increased WBC indicates infection is occurring. |

| Low platelets | Platelets are important during the proliferative phase in the creation of granulation tissue and angiogenesis.[75] |

| Low albumin | Low albumin indicates decreased protein levels. Protein is required for effective wound healing. |

| Elevated blood glucose or hemoglobin A1C | Elevated blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C levels indicate poor management of diabetes mellitus, a disease that impacts wound healing. |

| Elevated serum BUN and creatinine | BUN and creatinine levels are indicators of kidney function, with elevated levels indicating worsening kidney function. Elevated BUN (blood urea nitrogen) levels impact wound healing. |

| Positive wound culture | Positive wound cultures indicate an infection is present and provide additional information, including the type and number of bacteria present, as well as identifying antibiotics to which the bacteria is susceptible. The nurse reviews this information when administering antibiotics to ensure the prescribed therapy is effective for the type of bacteria present. |

Wound Complications

In addition to delayed wound healing, several other complications can occur. Three common complications are the development of a hematoma, infection, or dehiscence. These complications should be immediately reported to the health care provider.

Hematoma

A hematoma is an area of blood that collects outside of the larger blood vessels. A hematoma is more severe than ecchymosis (bruising) that occurs when small veins and capillaries under the skin break. The development of a hematoma at a surgical site can lead to infection and incisional dehiscence.[76] See Figure 20.14[77] for an image of a hematoma.

Infection

A break in the skin allows bacteria to enter and begin to multiply. Microbial contamination of wounds can progress from localized infection to systemic infection, sepsis, and subsequent life- and limb-threatening infection. Signs of a localized wound infection include redness, warmth, and tenderness around the wound. Purulent or malodorous drainage may also be present. Signs that a systemic infection is developing and requires urgent medical management include the following[78]:

- Fever over 101 F (38 C)

- Overall malaise (lack of energy and not feeling well)

- Change in level of consciousness/increased confusion

- Increasing or continual pain in the wound

- Expanding redness or swelling around the wound

- Loss of movement or function of the wounded area

Dehiscence

Dehiscence refers to the separation of the edges of a surgical wound. A dehisced wound can appear fully open where the tissue underneath is visible, or it can be partial where just a portion of the wound has torn open. Wound dehiscence is always a risk in a surgical wound, but the risk increases if the patient is obese, smokes, or has other health conditions, such as diabetes, that impact wound healing. Additionally, the location of the wound and the amount of physical activity in that area also increase the chances of wound dehiscence.[79] See Figure 20.15[80] for an image of dehiscence in an abdominal surgical wound in a 50-year-old obese female with a history of smoking and malnutrition.

Wound dehiscence can occur suddenly, especially in abdominal wounds when the patient is coughing or straining. Evisceration is a rare but severe surgical complication when dehiscence occurs, and the abdominal organs protrude out of the incision. Signs of impending dehiscence include redness around the wound margins and increasing drainage from the incision. The wound will also likely become increasingly painful. Suture breakage can be a sign that the wound has minor dehiscence or is about to dehisce.[81]

To prevent wound dehiscence, surgical patients must follow all post-op instructions carefully. The patient must move carefully and protect the skin from being pulled around the wound site. They should also avoid tensing the muscles surrounding the wound and avoid heavy lifting as advised.[82]