7.2 Head and Neck Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

To perform and document an accurate assessment of the head and neck, it is important to understand their basic anatomy and physiology.

Anatomy

Skull

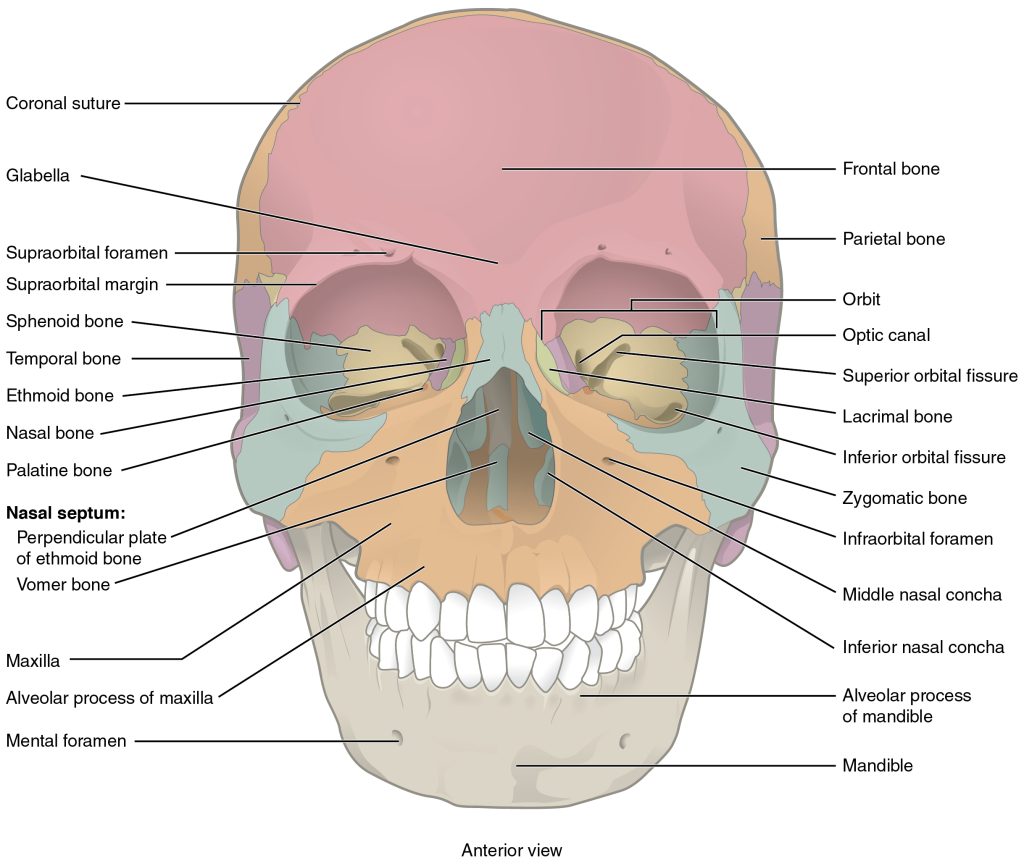

The anterior skull consists of facial bones that provide the bony support for the eyes and structures of the face. This anterior view of the skull is dominated by the openings of the orbits, the nasal cavity, and the upper and lower jaws. See Figure 7.1[1] for an illustration of the skull. The orbit is the bony socket that houses the eyeball and the muscles that move the eyeball. Inside the nasal area of the skull, the nasal cavity is divided into halves by the nasal septum that consists of both bone and cartilage components. The mandible forms the lower jaw and is the only movable bone in the skull. The maxilla forms the upper jaw and supports the upper teeth.[2]

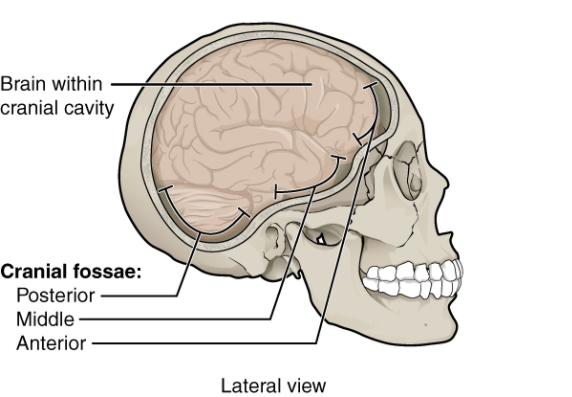

The cranium, or “brain case,” surrounds and protects the brain that occupies the cranial cavity. See Figure 7.2[3] for an image of the brain within the cranial cavity. The brain case consists of eight bones, including the paired parietal and temporal bones, plus the unpaired frontal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones.[4]

A suture is an interlocking joint between adjacent bones of the skull and is filled with dense, fibrous connective tissue that unites the bones. In a newborn infant, the pressure from vaginal delivery compresses the head and causes the bony plates to overlap at the sutures, creating a small ridge. Over the next few days, the head expands, the overlapping disappears, and the edges of the bony plates meet edge to edge. This is the normal position for the remainder of the life span and the sutures become immobile.

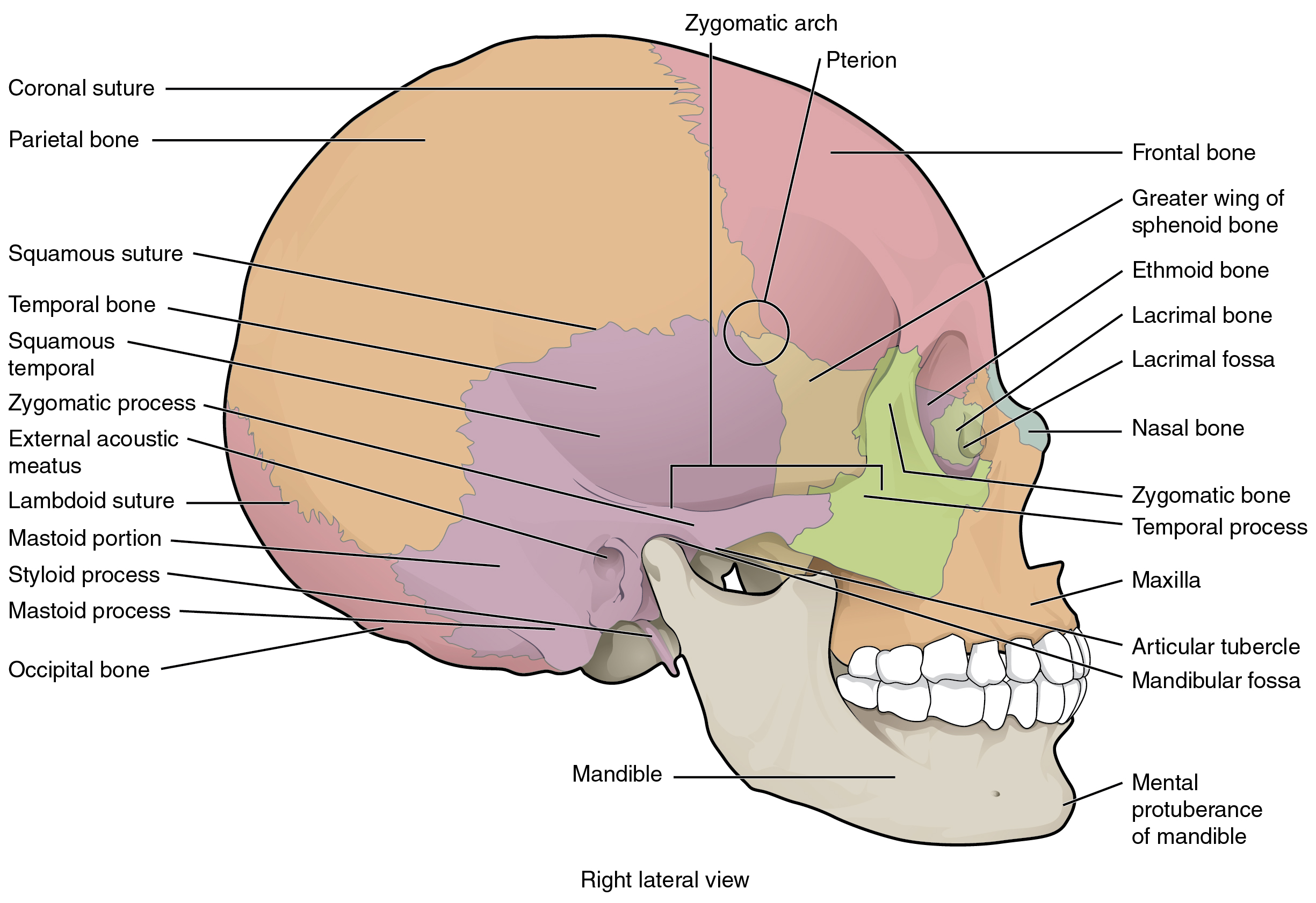

See Figure 7.3[5] for an illustration of two of the sutures, the coronal and squamous sutures, on the lateral view of the head. The coronal suture is seen on the top of the skull. It runs from side to side across the skull and joins the frontal bone to the right and left parietal bones. The squamous suture is located on the lateral side of the skull. It unites the squamous portion of the temporal bone with the parietal bone. At the intersection of the coronal and squamous sutures is the pterion, a small, capital H-shaped suture line region that unites the frontal bone, parietal bone, temporal bone, and greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The pterion is an important clinical landmark because located immediately under it, inside the skull, is a major branch of an artery that supplies the brain. A strong blow to this region can fracture the bones around the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a collection of blood, called a hematoma, between the brain and interior of the skull, which can be life-threatening.[6]

Paranasal Sinuses

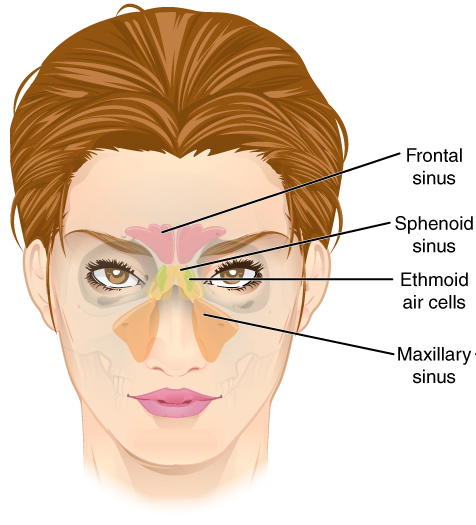

The paranasal sinuses are hollow, air-filled spaces located within the skull. See Figure 7.4[7] for an illustration of the sinuses. The sinuses connect with the nasal cavity and are lined with nasal mucosa. They reduce bone mass, lightening the skull, and also add resonance to the voice. When a person has a cold or sinus congestion, the mucosa swells and produces excess mucus that often obstructs the narrow passageways between the sinuses and the nasal cavity. The resulting pressure produces pain and discomfort.[8]

Each of the paranasal sinuses is named for the skull bone that it occupies. The frontal sinus is located just above the eyebrows within the frontal bone. The largest sinus, the maxillary sinus, is paired and located within the right and left maxillary bones just below the orbits. The maxillary sinuses are most commonly involved during sinus infections. The sphenoid sinus is a single, midline sinus located within the body of the sphenoid bone. The lateral aspects of the ethmoid bone contain multiple small spaces separated by very thin, bony walls. Each of these spaces is called an ethmoid air cell.

Anatomy of Nose, Pharynx, and Mouth

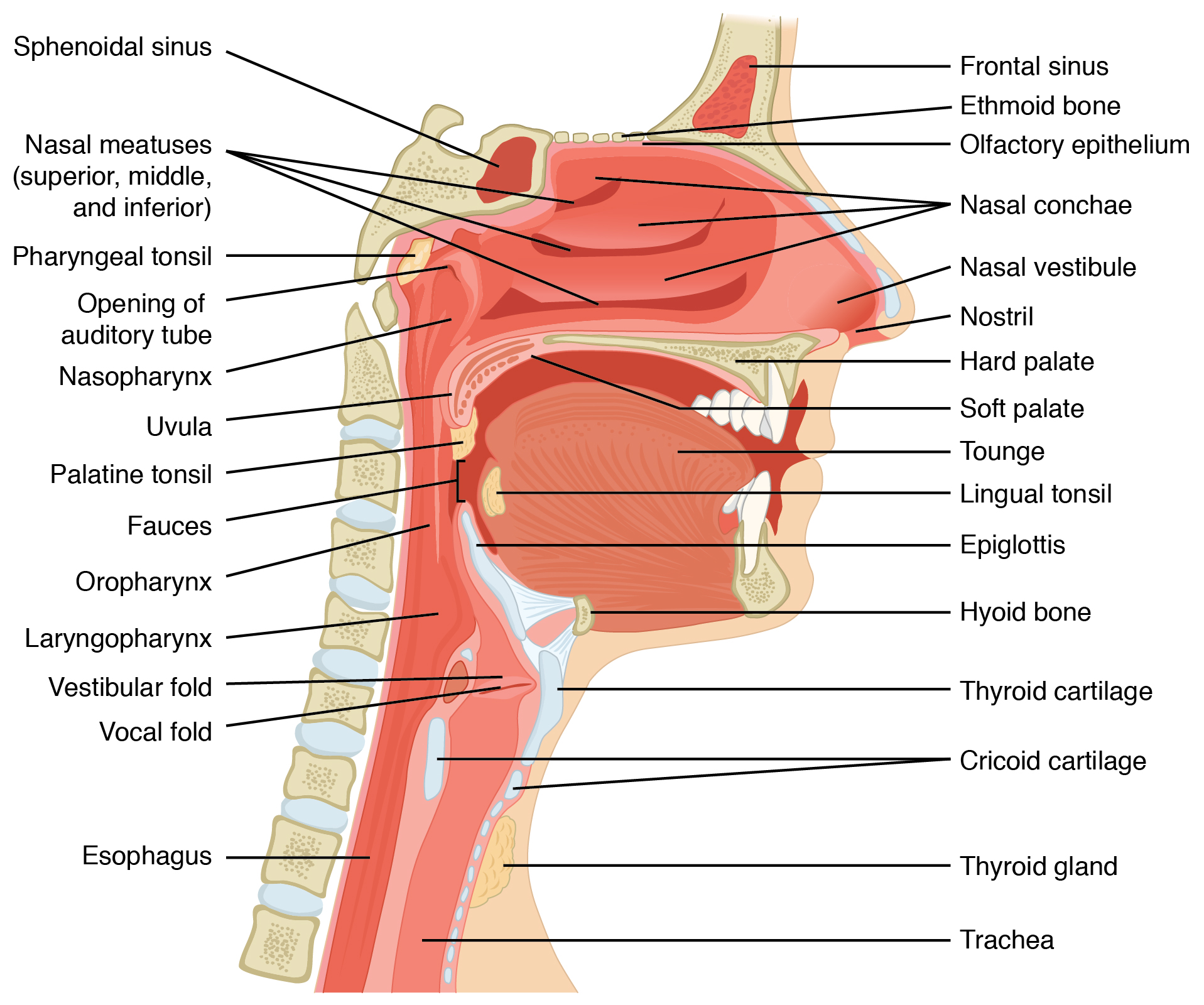

See Figure 7.5[9] to review the anatomy of the head and neck. The major entrance and exit for the respiratory system is through the nose. The bridge of the nose consists of bone, but the protruding portion of the nose is composed of cartilage. The nares are the nostril openings that open into the nasal cavity and are separated into left and right sections by the nasal septum. The floor of the nasal cavity is composed of the palate. The hard palate is located at the anterior region of the nasal cavity and is composed of bone. The soft palate is located at the posterior portion of the nasal cavity and consists of muscle tissue. The uvula is a small, teardrop-shaped structure located at the apex of the soft palate. Both the uvula and soft palate move like a pendulum during swallowing, swinging upward to close off the nasopharynx and prevent ingested materials from entering the nasal cavity.[10]

As air is inhaled through the nose, the paranasal sinuses warm and humidify the incoming air as it moves into the pharynx. The pharynx is a tube-lined mucous membrane that begins at the nasal cavity and is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.[11]

The nasopharynx serves only as an airway. At the top of the nasopharynx is the pharyngeal tonsil, commonly referred to as the adenoids. Adenoids are lymphoid tissue that trap and destroy invading pathogens that enter during inhalation. They are large in children but tend to regress with age and may even disappear.[12]

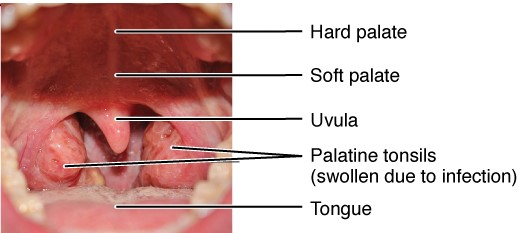

The oropharynx is a passageway for both air and food. The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity. The oropharynx contains two sets of tonsils, the palatine and lingual tonsils. The palatine tonsil is located laterally in the oropharynx, and the lingual tonsil is located at the base of the tongue. Similar to the pharyngeal tonsil, the palatine and lingual tonsils are composed of lymphoid tissue and trap and destroy pathogens entering the body through the oral or nasal cavities. See Figure 7.6[13] for an image of the oral cavity and oropharynx with enlarged palatine tonsils.

The laryngopharynx is inferior to the oropharynx and posterior to the larynx. It continues the route for ingested material and air until its inferior end where the digestive and respiratory systems diverge. Anteriorly, the laryngopharynx opens into the larynx, and posteriorly, it enters the esophagus that leads to the stomach. The larynx connects the pharynx to the trachea and helps regulate the volume of air that enters and leaves the lungs. It also contains the vocal cords that vibrate as air passes over them to produce the sound of a person’s voice. The trachea extends from the larynx to the lungs. The epiglottis is a flexible piece of cartilage that covers the opening of the trachea during swallowing to prevent ingested material from entering the trachea.[14]

Muscles and Nerves of the Head and Neck

Facial Muscles

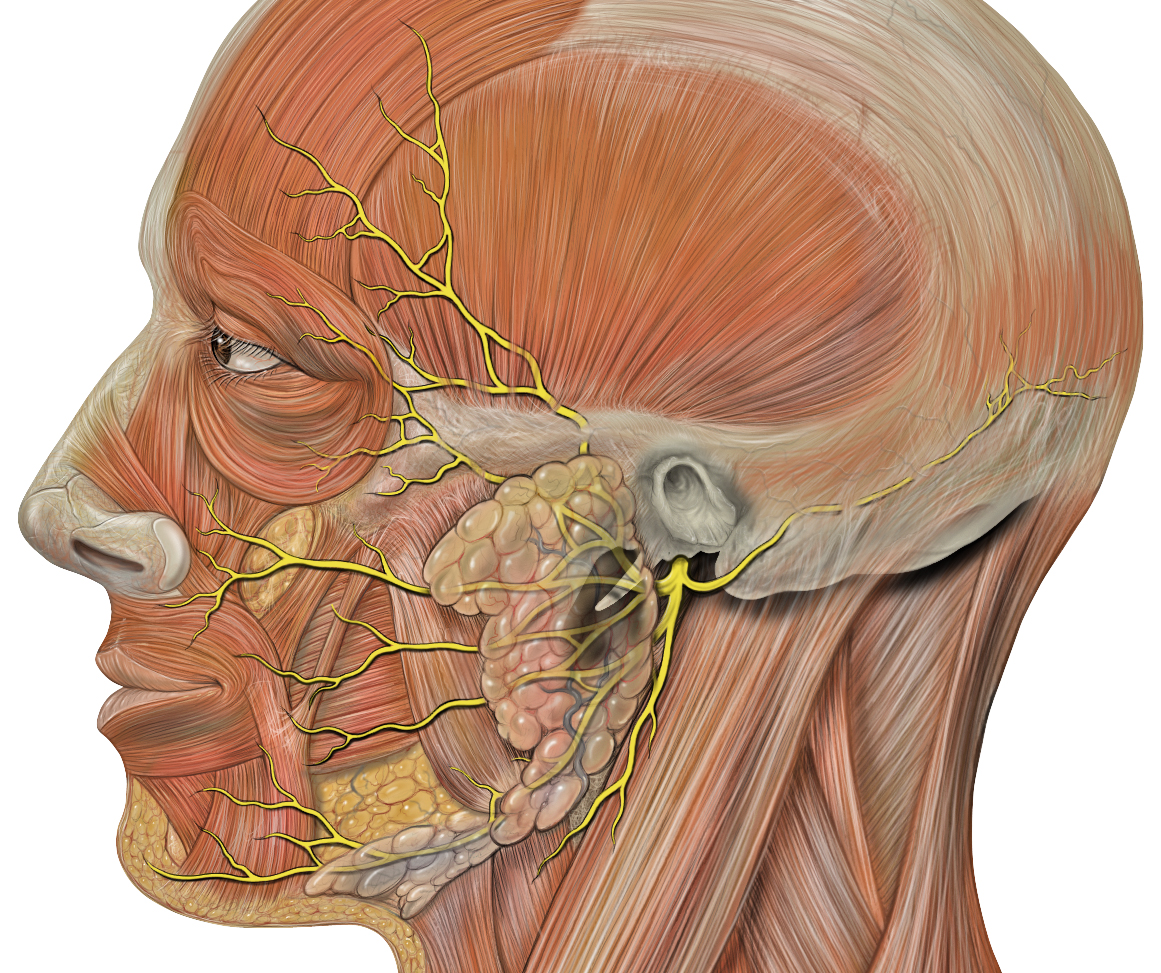

Several nerves innervate the facial muscles to create facial expressions. See Figure 7.7[15] for an illustration of nerves innervating facial muscles. These nerves and muscles are tested during a cranial nerve exam. See more information about performing a cranial nerve exam in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

When a patient is experiencing a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke), it is common for facial drooping to occur. Facial drooping is an asymmetrical facial expression that occurs due to damage of the nerve innervating a specific part of the face. See Figure 7.8[16] for an image of facial drooping occurring on the patient’s right side of their face.

Neck Muscles

The muscles of the anterior neck assist in swallowing and speech by controlling the positions of the larynx and the hyoid bone, a horseshoe-shaped bone that functions as a solid foundation on which the tongue can move. The head, attached to the top of the vertebral column, is balanced, moved, and rotated by the neck muscles. When these muscles act unilaterally, the head rotates. When they contract bilaterally, the head flexes or extends. The major muscle that laterally flexes and rotates the head is the sternocleidomastoid. The trapezius muscle elevates the shoulders (shrugging), pulls the shoulder blades together, and tilts the head backwards. See Figure 7.9[17] for an illustration of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.[18] Both of these muscles are tested during a cranial nerve assessment. See more information about cranial nerve assessment in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

Jaw Muscles

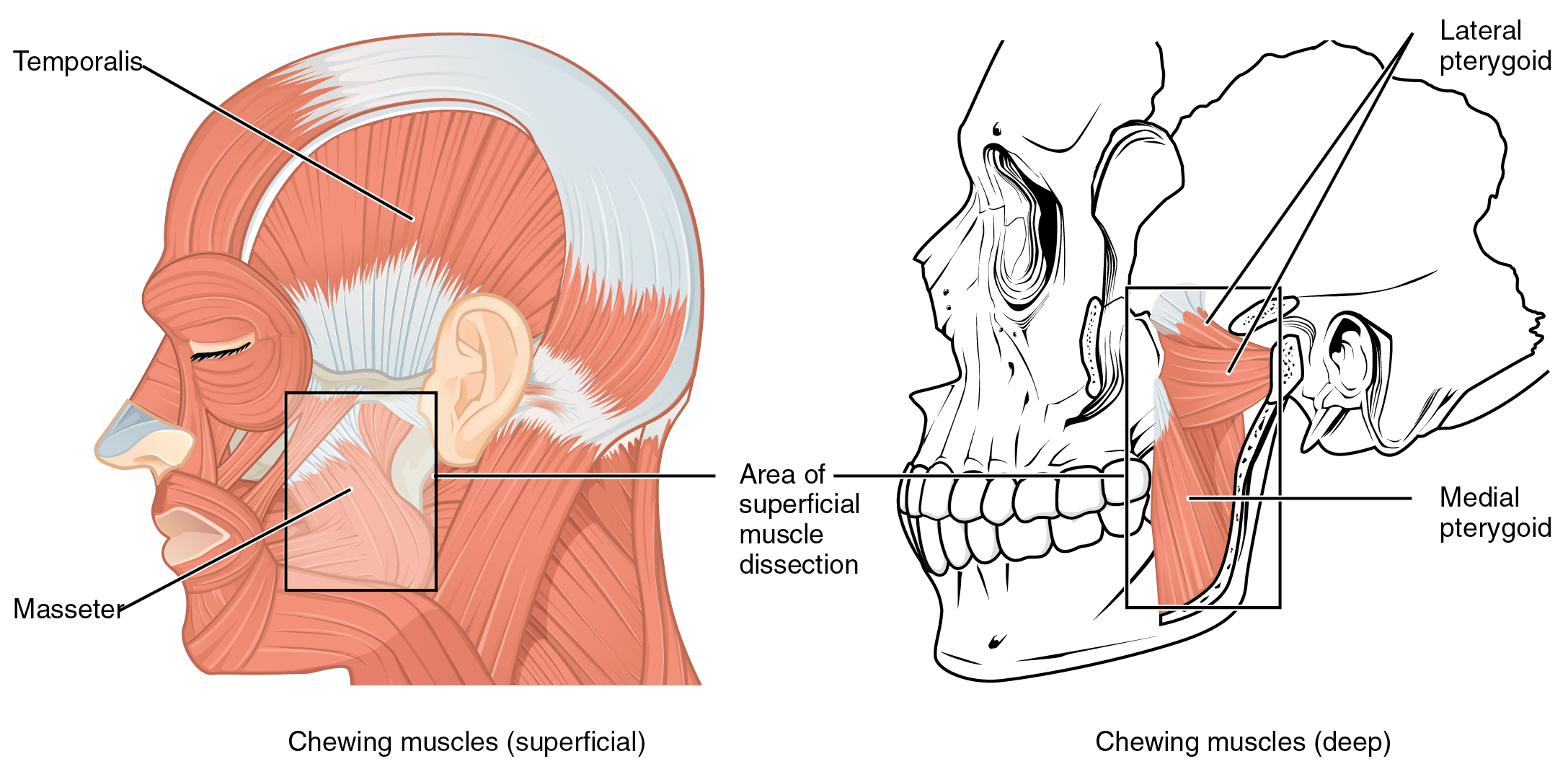

The masseter muscle is the main muscle used for chewing because it elevates the mandible (lower jaw) to close the mouth. It is assisted by the temporalis muscle that retracts the mandible. The temporalis muscle can be felt moving by placing fingers on the patient’s temple as they chew. See Figure 7.10[19] for an illustration of the masseter and temporalis muscles.[20]

Tongue Muscles

Muscles of the tongue are necessary for chewing, swallowing, and speech. Because it is so moveable, the tongue facilitates complex speech patterns and sounds.[21]

Airway and Unconsciousness

When a patient becomes unconscious and is lying supine, the tongue often moves backwards and blocks the airway. This is why it is important to open the airway when performing CPR by using a chin-thrust maneuver. See Figure 7.11[22] for an image of the tongue blocking the airway. In a similar manner, when a patient is administered general anesthesia during surgery, the tongue relaxes and can block the airway. For this reason, endotracheal intubation is performed during surgery with general anesthesia by placing a tube into the trachea to maintain an open airway to the lungs. After surgery, patients often report a sore or scratchy throat for a few days due to the endotracheal intubation.[23]

Swallowing

Swallowing is a complex process that uses 50 pairs of muscles and many nerves to receive food in the mouth, prepare it, and move it from the mouth to the stomach. Swallowing occurs in three stages. During the first stage, called the oral phase, the tongue collects the food or liquid and makes it ready for swallowing. The tongue and jaw move solid food around in the mouth so it can be chewed and made the right size and texture to swallow by mixing food with saliva. The second stage begins when the tongue pushes the food or liquid to the back of the mouth. This triggers a swallowing response that passes the food through the pharynx. During this phase, called the pharyngeal phase, the epiglottis closes off the larynx and breathing stops to prevent food or liquid from entering the airway and lungs. The third stage begins when food or liquid enters the esophagus, and it is carried to the stomach. The passage through the esophagus, called the esophageal phase, usually occurs in about three seconds.[24]

View the following video from Medline Plus on the swallowing process:

Dysphagia is the medical term for swallowing difficulties that occur when there is a problem with the nerves or structures involved in the swallowing process.[26] Nurses are often the first to notice signs of dysphagia in their patients that can occur due to a multitude of medical conditions such as a stroke, head injury, or dementia. For more information about the symptoms, screening, and treatment for dysphagia, go to the “Common Conditions of the Head and Neck” section.

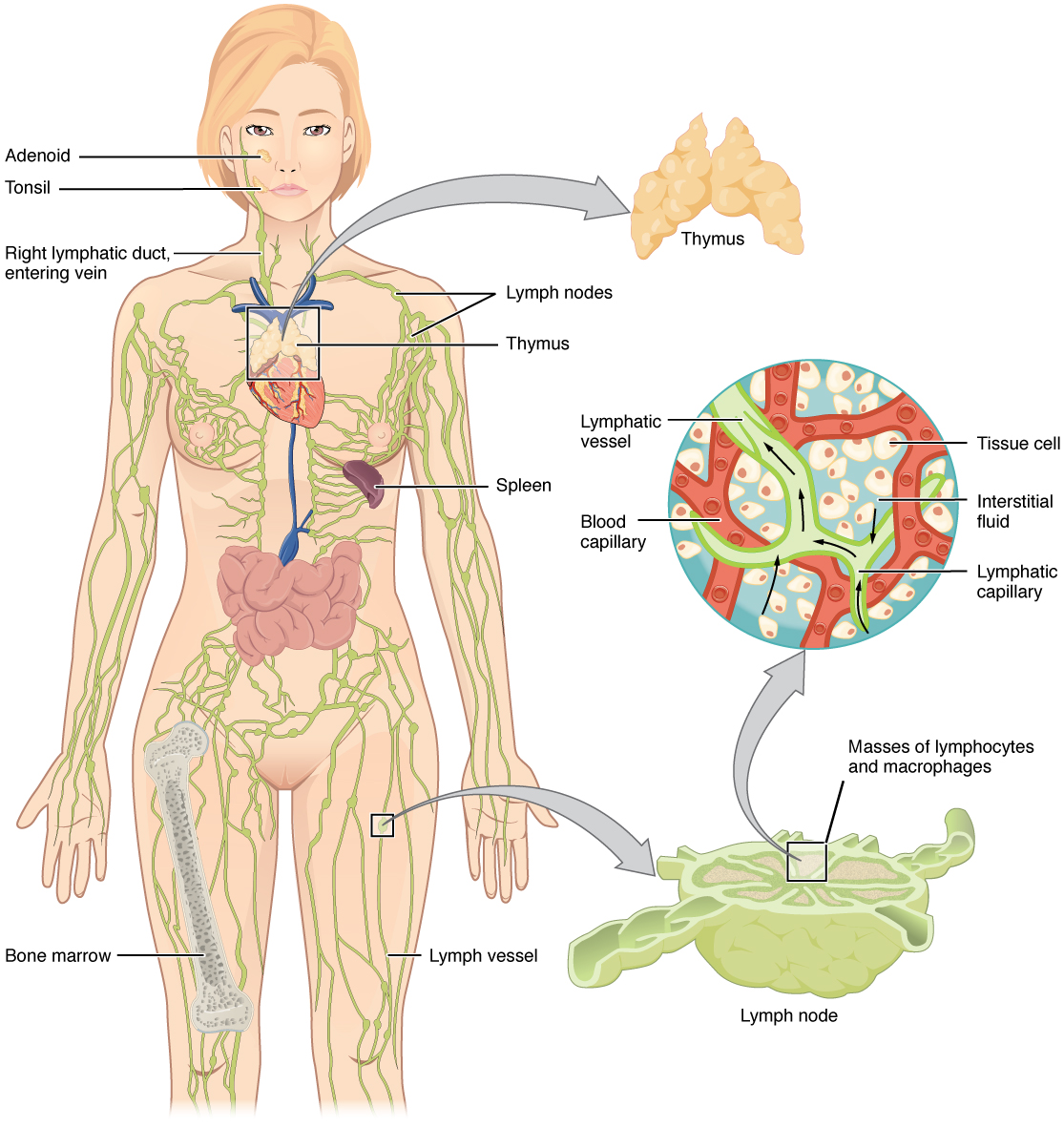

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is the system of vessels, cells, and organs that carries excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream and filters pathogens from the blood through lymph nodes found near the neck, armpits, chest, abdomen, and groin. See Figure 7.12[27] and Figure 7.13[28] for an illustration of the lymph nodes found in the head and neck regions. When a person is fighting off an infection, the lymph nodes in that region become enlarged, indicating an active immune response to infection.[29]

![]“Cervical lymph nodes and level.png” by Mikael Häggström, M.D. is licensed under CC0 1.0 Illustration of lymph nodes in head and neck, with labels](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/32/2024/08/Cervical_lymph_nodes_and_levels-3.png)

- “704 Skull -01.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/7-2-the-skull ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of “727_Cranial_Fossae.jpg” by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/7-2-the-skull ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “705 Lateral View of Skull-01.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/7-2-the-skull ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Paranasal Sinuses ant.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/7-2-the-skull ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- "2303 Anatomy of Nose-Pharynx-Mouth-Larynx.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of “2209 Location and Histology of Tonsils.jpg” by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/21-1-anatomy-of-the-lymphatic-and-immune-systems ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Head facial nerve branches.jpg” by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator is licensed under CC BY 2.5 ↵

- “Stroke-facial-droop.jpg” by Another-anon-artist-234 is licensed under CC0 1.0 ↵

- “1111 Posterior and Side Views of the Next.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/11-3-axial-muscles-of-the-head-neck-and-back. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1108 Muscle that Move the Lower Jaw.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/11-3-axial-muscles-of-the-head-neck-and-back ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Airway closed in an unconscious patient because the head inflexed forward.jpg” by Dr. Lorimer is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2017, March 6). Dysphagia. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/dysphagia ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M. Inc.; c1997-2021. Swallowing [Video]. [updated 2019, July 11]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000126.htm ↵

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2017, March 6). Dysphagia. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/dysphagia ↵

- “2201 Anatomy of the Lymphatic System.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/21-1-anatomy-of-the-lymphatic-and-immune-systems ↵

- “Cervical lymph nodes and level.png” by Mikael Häggström, M.D. is licensed under CC0 1.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

Prioritization of care for multiple patients while also performing daily nursing tasks can feel overwhelming in today’s fast-paced health care system. Because of the rapid and ever-changing conditions of patients and the structure of one’s workday, nurses must use organizational frameworks to prioritize actions and interventions. These frameworks can help ease anxiety, enhance personal organization and confidence, and ensure patient safety.

Acuity

Acuity and intensity are foundational concepts for prioritizing nursing care and interventions. Acuity refers to the level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. For example, acuity may include characteristics such as unstable vital signs, oxygenation therapy, high-risk IV medications, multiple drainage devices, or uncontrolled pain. A "high-acuity" patient requires several nursing interventions and frequent nursing assessments.

Intensity addresses the time needed to complete nursing care and interventions such as providing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), performing wound care, or administering several medication passes. For example, a "high-intensity" patient generally requires frequent or long periods of psychosocial, educational, or hygiene care from nursing staff members. High-intensity patients may also have increased needs for safety monitoring, familial support, or other needs.[1]

Many health care organizations structure their staffing assignments based on acuity and intensity ratings to help provide equity in staff assignments. Acuity helps to ensure that nursing care is strategically divided among nursing staff. An equitable assignment of patients benefits both the nurse and patient by helping to ensure that patient care needs do not overwhelm individual staff and safe care is provided.

Organizations use a variety of systems when determining patient acuity with rating scales based on nursing care delivery, patient stability, and care needs. See an example of a patient acuity tool published in the American Nurse in Table 2.3.[2] In this example, ratings range from 1 to 4, with a rating of 1 indicating a relatively stable patient requiring minimal individualized nursing care and intervention. A rating of 2 reflects a patient with a moderate risk who may require more frequent intervention or assessment. A rating of 3 is attributed to a complex patient who requires frequent intervention and assessment. This patient might also be a new admission or someone who is confused and requires more direct observation. A rating of 4 reflects a high-risk patient. For example, this individual may be experiencing frequent changes in vital signs, may require complex interventions such as the administration of blood transfusions, or may be experiencing significant uncontrolled pain. An individual with a rating of 4 requires more direct nursing care and intervention than a patient with a rating of 1 or 2.[3]

Table 2.3. Example of a Patient Acuity Tool[4]

| 1: Stable Patient | 2: Moderate-Risk Patient | 3: Complex Patient | 4: High-Risk Patient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

|

|

| Cardiac |

|

|

|

|

| Medications |

|

|

|

|

| Drainage Devices |

|

|

|

|

| Pain Management |

|

|

|

|

| Admit/Transfer/Discharge |

|

|

|

|

| ADLs and Isolation |

|

|

|

|

| Patient Score | Most = 1 | Two or > = 2 | Any = 3 | Any = 4 |

Read more about using a patient acuity tool on a medical-surgical unit.

Rating scales may vary among institutions, but the principles of the rating system remain the same. Organizations include various patient care elements when constructing their staffing plans for each unit. Read more information about staffing models and acuity in the following box.

Staffing Models and Acuity

Organizations that base staffing on acuity systems attempt to evenly staff patient assignments according to their acuity ratings. This means that when comparing patient assignments across nurses on a unit, similar acuity team scores should be seen with the goal of achieving equitable and safe division of workload across the nursing team. For example, one nurse should not have a total acuity score of 6 for their patient assignments while another nurse has a score of 15. If this situation occurred, the variation in scoring reflects a discrepancy in workload balance and would likely be perceived by nursing peers as unfair. Using acuity-rating staffing models is helpful to reflect the individualized nursing care required by different patients.

Alternatively, nurse staffing models may be determined by staffing ratio. Ratio-based staffing models are more straightforward in nature, where each nurse is assigned care for a set number of patients during their shift. Ratio-based staffing models may be useful for administrators creating budget requests based on the number of staff required for patient care, but can lead to an inequitable division of work across the nursing team when patient acuity is not considered. Increasingly complex patients require more time and interventions than others, so a blend of both ratio and acuity-based staffing is helpful when determining staffing assignments.[5]

As a practicing nurse, you will be oriented to the elements of acuity ratings within your health care organization, but it is also important to understand how you can use these acuity ratings for your own prioritization and task delineation. Let’s consider the Scenario B in the following box to better understand how acuity ratings can be useful for prioritizing nursing care.

Scenario B

You report to work at 6 a.m. for your nursing shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. Prior to receiving the handoff report from your night shift nursing colleagues, you review the unit staffing grid and see that you have been assigned to four patients to start your day. The patients have the following acuity ratings:

Patient A: 45-year-old patient with paraplegia admitted for an infected sacral wound, with an acuity rating of 4.

Patient B: 87-year-old patient with pneumonia with a low-grade fever of 99.7 F and receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute via nasal cannula, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient C: 63-year-old patient who is postoperative Day 1 from a right total hip replacement and is receiving pain management via a PCA pump, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient D: 83-year-old patient admitted with a UTI who is finishing an IV antibiotic cycle and will be discharged home today, with an acuity rating of 1.

Based on the acuity rating system, your patient assignment load receives an overall acuity score of 9. Consider how you might use their acuity ratings to help you prioritize your care. Based on what is known about the patients related to their acuity rating, whom might you identify as your care priority? Although this can feel like a challenging question to answer because of the many unknown elements in the situation using acuity numbers alone, Patient A with an acuity rating of 4 would be identified as the care priority requiring assessment early in your shift.

Although acuity can a useful tool for determining care priorities, it is important to recognize the limitations of this tool and consider how other patient needs impact prioritization.

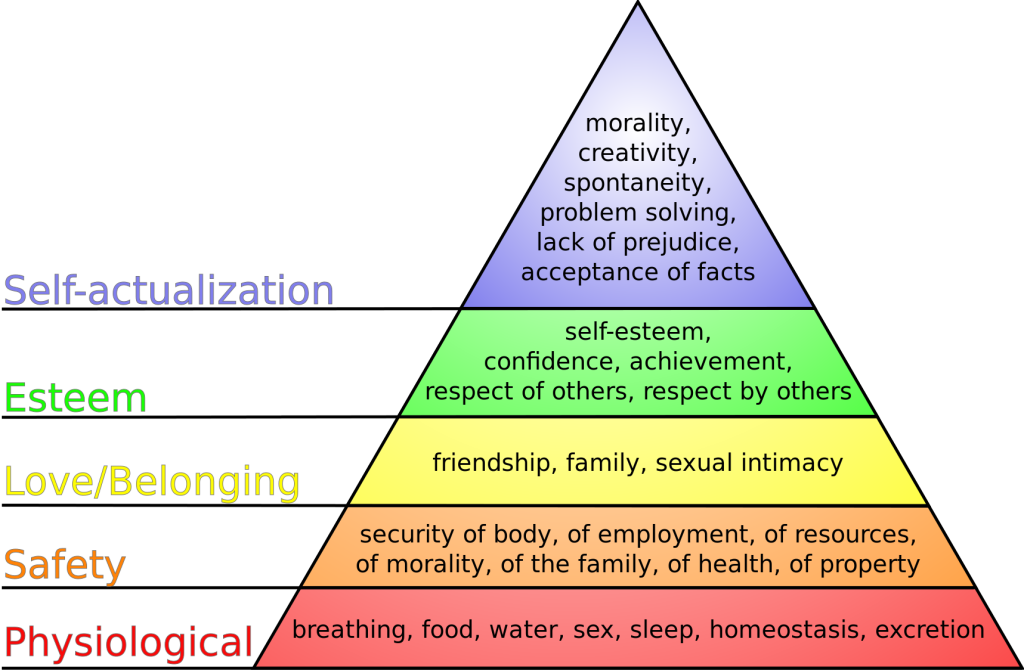

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

When thinking back to your first nursing or psychology course, you may recall a historical theory of human motivation based on various levels of human needs called Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs reflects foundational human needs with progressive steps moving towards higher levels of achievement. This hierarchy of needs is traditionally represented as a pyramid with the base of the pyramid serving as essential needs that must be addressed before one can progress to another area of need.[6] See Figure 2.1[7] for an illustration of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs places physiological needs as the foundational base of the pyramid.[8] Physiological needs include oxygen, food, water, sex, sleep, homeostasis, and excretion. The second level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects safety needs. Safety needs include elements that keep individuals safe from harm. Examples of safety needs in health care include fall precautions. The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects emotional needs such as love and a sense of belonging. These needs are often reflected in an individual’s relationships with family members and friends. The top two levels of Maslow’s hierarchy include esteem and self-actualization. An example of addressing these needs in a health care setting is helping an individual build self-confidence in performing blood glucose checks that leads to improved self-management of their diabetes.

So how does Maslow’s theory impact prioritization? To better understand the application of Maslow’s theory to prioritization, consider Scenario C in the following box.

Scenario C

You are an emergency response nurse working at a local shelter in a community that has suffered a devastating hurricane. Many individuals have relocated to the shelter for safety in the aftermath of the hurricane. Much of the community is still without electricity and clean water, and many homes have been destroyed. You approach a young woman who has a laceration on her scalp that is bleeding through her gauze dressing. The woman is weeping as she describes the loss of her home stating, “I have lost everything! I just don’t know what I am going to do now. It has been a day since I have had water or anything to drink. I don’t know where my sister is, and I can’t reach any of my family to find out if they are okay!”

Despite this relatively brief interaction, this woman has shared with you a variety of needs. She has demonstrated a need for food, water, shelter, homeostasis, and family. As the nurse caring for her, it might be challenging to think about where to begin her care. These thoughts could be racing through your mind:

Should I begin to make phone calls to try and find her family? Maybe then she would be able to calm down.

Should I get her on the list for the homeless shelter so she wouldn’t have to worry about where she will sleep tonight?

She hasn’t eaten in a while; I should probably find her something to eat.

All these needs are important and should be addressed at some point, but Maslow’s hierarchy provides guidance on what needs must be addressed first. Use the foundational level of Maslow’s pyramid of physiological needs as the top priority for care. The woman is bleeding heavily from a head wound and has had limited fluid intake. As the nurse caring for this patient, it is important to immediately intervene to stop the bleeding and restore fluid volume. Stabilizing the patient by addressing her physiological needs is required before undertaking additional measures such as contacting her family. Imagine if instead you made phone calls to find the patient’s family and didn't address the bleeding or dehydration - you might return to a severely hypovolemic patient who has deteriorated and may be near death. In this example, prioritizing emotional needs above physiological needs can lead to significant harm to the patient.

Although this is a relatively straightforward example, the principles behind the application of Maslow’s hierarchy are essential. Addressing physiological needs before progressing toward additional need categories concentrates efforts on the most vital elements to enhance patient well-being. Maslow’s hierarchy provides the nurse with a helpful framework for identifying and prioritizing critical patient care needs.

ABCs

Airway, breathing, and circulation, otherwise known by the mnemonic “ABCs,” are another foundational element to assist the nurse in prioritization. Like Maslow’s hierarchy, using the ABCs to guide decision-making concentrates on the most critical needs for preserving human life. If a patient does not have a patent airway, is unable to breathe, or has inadequate circulation, very little of what else we do matters. The patient’s ABCs are reflected in Maslow’s foundational level of physiological needs and direct critical nursing actions and timely interventions. Let’s consider Scenario D in the following box regarding prioritization using the ABCs and the physiological base of Maslow’s hierarchy.

Scenario D

You are a nurse on a busy cardiac floor charting your morning assessments on a computer at the nurses’ station. Down the hall from where you are charting, two of your assigned patients are resting comfortably in Room 504 and Room 506. Suddenly, both call lights ring from the rooms, and you answer them via the intercom at the nurses’ station.

Room 504 has an 87-year-old male who has been admitted with heart failure, weakness, and confusion. He has a bed alarm for safety and has been ringing his call bell for assistance appropriately throughout the shift. He requires assistance to get out of bed to use the bathroom. He received his morning medications, which included a diuretic about 30 minutes previously, and now reports significant urge to void and needs assistance to the bathroom.

Room 506 has a 47-year-old woman who was hospitalized with new onset atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. The patient underwent a cardioversion procedure yesterday that resulted in successful conversion of her heart back into normal sinus rhythm. She is reporting via the intercom that her "heart feels like it is doing that fluttering thing again” and she is having chest pain with breathlessness.

Based upon these two patient scenarios, it might be difficult to determine whom you should see first. Both patients are demonstrating needs in the foundational physiological level of Maslow’s hierarchy and require assistance. To prioritize between these patients' physiological needs, the nurse can apply the principles of the ABCs to determine intervention. The patient in Room 506 reports both breathing and circulation issues, warning indicators that action is needed immediately. Although the patient in Room 504 also has an urgent physiological elimination need, it does not overtake the critical one experienced by the patient in Room 506. The nurse should immediately assess the patient in Room 506 while also calling for assistance from a team member to assist the patient in Room 504.

CURE

Prioritizing what should be done and when it can be done can be a challenging task when several patients all have physiological needs. Recently, there has been professional acknowledgement of the cognitive challenge for novice nurses in differentiating physiological needs. To expand on the principles of prioritizing using the ABCs, the CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras.[9]

“Critical” patient needs require immediate action. Examples of critical needs align with the ABCs and Maslow’s physiological needs, such as symptoms of respiratory distress, chest pain, and airway compromise. No matter the complexity of their shift, nurses can be assured that addressing patients' critical needs is the correct prioritization of their time and energies.

After critical patient care needs have been addressed, nurses can then address “urgent” needs. Urgent needs are characterized as needs that cause patient discomfort or place the patient at a significant safety risk.[10]

The third part of the CURE hierarchy reflects “routine” patient needs. Routine patient needs can also be characterized as "typical daily nursing care" because the majority of a standard nursing shift is spent addressing routine patient needs. Examples of routine daily nursing care include actions such as administering medication and performing physical assessments.[11] Although a nurse’s typical shift in a hospital setting includes these routine patient needs, they do not supersede critical or urgent patient needs.

The final component of the CURE hierarchy is known as “extras.” Extras refer to activities performed in the care setting to facilitate patient comfort but are not essential.[12] Examples of extra activities include providing a massage for comfort or washing a patient’s hair. If a nurse has sufficient time to perform extra activities, they contribute to a patient’s feeling of satisfaction regarding their care, but these activities are not essential to achieve patient outcomes.

Let's apply the CURE mnemonic to patient care in the following box.

If we return to Scenario D regarding patients in Room 504 and 506, we can see the patient in Room 504 is having urgent needs. He is experiencing a physiological need to urgently use the restroom and may also have safety concerns if he does not receive assistance and attempts to get up on his own because of weakness. He is on a bed alarm, which reflects safety considerations related to his potential to get out of bed without assistance. Despite these urgent indicators, the patient in Room 506 is experiencing a critical need and takes priority. Recall that critical needs require immediate nursing action to prevent patient deterioration. The patient in Room 506 with a rapid, fluttering heartbeat and shortness of breath has a critical need because without prompt assessment and intervention, their condition could rapidly decline and become fatal.

Data Cues

In addition to using the identified frameworks and tools to assist with priority setting, nurses must also look at their patients’ data cues to help them identify care priorities. Data cues are pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition. For example, have the patient’s vital signs worsened over the last few hours? Is there a new laboratory result that is concerning? Data cues are used in conjunction with prioritization frameworks to help the nurse holistically understand the patient's current status and where nursing interventions should be directed. Common categories of data clues include acute versus chronic conditions, actual versus potential problems, unexpected versus expected conditions, information obtained from the review of a patient’s chart, and diagnostic information.

Acute Versus Chronic Conditions

A common data cue that nurses use to prioritize care is considering if a condition or symptom is acute or chronic. Acute conditions have a sudden and severe onset. These conditions occur due to a sudden illness or injury, and the body often has a significant response as it attempts to adapt. Chronic conditions have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time. The difference between an acute versus a chronic condition relates to the body’s adaptation response. Individuals with chronic conditions often experience less symptom exacerbation because their body has had time to adjust to the illness or injury. Let’s consider an example of two patients admitted to the medical-surgical unit complaining of pain in Scenario E in the following box.

Scenario E

As part of your patient assignment on a medical-surgical unit, you are caring for two patients who both ring the call light and report pain at the start of the shift. Patient A was recently admitted with acute appendicitis, and Patient B was admitted for observation due to weakness. Not knowing any additional details about the patients' conditions or current symptoms, which patient would receive priority in your assessment? Based on using the data cue of acute versus chronic conditions, Patient A with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis would receive top priority for assessment over a patient with chronic pain due to osteoarthritis. Patients experiencing acute pain require immediate nursing assessment and intervention because it can indicate a change in condition. Acute pain also elicits physiological effects related to the stress response, such as elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate, and should be addressed quickly.

Actual Versus Potential Problems

Nursing diagnoses and the nursing care plan have significant roles in directing prioritization when interpreting assessment data cues. Actual problems refer to a clinical problem that is actively occurring with the patient. A risk problem indicates the patient may potentially experience a problem but they do not have current signs or symptoms of the problem actively occurring.

Consider an example of prioritizing actual and potential problems in Scenario F in the following box.

Scenario F

A 74-year-old woman with a previous history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is admitted to the hospital for pneumonia. She has generalized weakness, a weak cough, and crackles in the bases of her lungs. She is receiving IV antibiotics, fluids, and oxygen therapy. The patient can sit at the side of the bed and ambulate with the assistance of staff, although she requires significant encouragement to ambulate.

Nursing diagnoses are established for this patient as part of the care planning process. One nursing diagnosis for this patient is Ineffective Airway Clearance. This nursing diagnosis is an actual problem because the patient is currently exhibiting signs of poor airway clearance with an ineffective cough and crackles in the lungs. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include coughing and deep breathing, administering nebulizer treatment, and evaluating the effectiveness of oxygen therapy. The patient also has the nursing diagnosis Risk for Skin Breakdown based on her weakness and lack of motivation to ambulate. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include repositioning every two hours and assisting with ambulation twice daily.

The established nursing diagnoses provide cues for prioritizing care. For example, if the nurse enters the patient’s room and discovers the patient is experiencing increased shortness of breath, nursing interventions to improve the patient’s respiratory status receive top priority before attempting to get the patient to ambulate.

Although there may be times when risk problems may supersede actual problems, looking to the “actual” nursing problems can provide clues to assist with prioritization.

Unexpected Versus Expected Conditions

In a similar manner to using acute versus chronic conditions as a cue for prioritization, it is also important to consider if a client's signs and symptoms are "expected" or "unexpected" based on their overall condition. Unexpected conditions are findings that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury. Expected conditions are findings that are likely to occur or are anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury. Unexpected findings often require immediate action by the nurse.

Let’s apply this tool to the two patients previously discussed in Scenario E. As you recall, both Patient A (with acute appendicitis) and Patient B (with weakness and diagnosed with osteoarthritis) are reporting pain. Acute pain typically receives priority over chronic pain. But what if both patients are also reporting nausea and have an elevated temperature? Although these symptoms must be addressed in both patients, they are "expected" symptoms with acute appendicitis (and typically addressed in the treatment plan) but are "unexpected" for the patient with osteoarthritis. Critical thinking alerts you to the unexpected nature of these symptoms in Patient B, so they receive priority for assessment and nursing interventions.

Handoff Report/Chart Review

Additional data cues that are helpful in guiding prioritization come from information obtained during a handoff nursing report and review of the patient chart. These data cues can be used to establish a patient's baseline status and prioritize new clinical concerns based on abnormal assessment findings. Let’s consider Scenario G in the following box based on cues from a handoff report and how it might be used to help prioritize nursing care.

Scenario G

Imagine you are receiving the following handoff report from the night shift nurse for a patient admitted to the medical-surgical unit with pneumonia:

At the beginning of my shift, the patient was on room air with an oxygen saturation of 93%. She had slight crackles in both bases of her posterior lungs. At 0530, the patient rang the call light to go to the bathroom. As I escorted her to the bathroom, she appeared slightly short of breath. Upon returning the patient to bed, I rechecked her vital signs and found her oxygen saturation at 88% on room air and respiratory rate of 20. I listened to her lung sounds and noticed more persistent crackles and coarseness than at bedtime. I placed the patient on 2 L/minute of oxygen via nasal cannula. Within five minutes, her oxygen saturation increased to 92%, and she reported increased ease in respiration.

Based on the handoff report, the night shift nurse provided substantial clinical evidence that the patient may be experiencing a change in condition. Although these changes could be attributed to lack of lung expansion that occurred while the patient was sleeping, there is enough information to indicate to the oncoming nurse that follow-up assessment and interventions should be prioritized for this patient because of potentially worsening respiratory status. In this manner, identifying data cues from a handoff report can assist with prioritization.

Now imagine the night shift nurse had not reported this information during the handoff report. Is there another method for identifying potential changes in patient condition? Many nurses develop a habit of reviewing their patients’ charts at the start of every shift to identify trends and “baselines” in patient condition. For example, a chart review reveals a patient’s heart rate on admission was 105 beats per minute. If the patient continues to have a heart rate in the low 100s, the nurse is not likely to be concerned if today’s vital signs reveal a heart rate in the low 100s. Conversely, if a patient’s heart rate on admission was in the 60s and has remained in the 60s throughout their hospitalization, but it is now in the 100s, this finding is an important cue requiring prioritized assessment and intervention.

Diagnostic Information

Diagnostic results are also important when prioritizing care. In fact, the National Patient Safety Goals from The Joint Commission include prompt reporting of important test results. New abnormal laboratory results are typically flagged in a patient’s chart or are reported directly by phone to the nurse by the laboratory as they become available. Newly reported abnormal results, such as elevated blood levels or changes on a chest X-ray, may indicate a patient’s change in condition and require additional interventions. For example, consider Scenario H in which you are the nurse providing care for five medical-surgical patients.

Scenario H

You completed morning assessments on your assigned five patients. Patient A previously underwent a total right knee replacement and will be discharged home today. You are about to enter Patient A’s room to begin discharge teaching when you receive a phone call from the laboratory department, reporting a critical hemoglobin of 6.9 gm/dL on Patient B. Rather than enter Patient A’s room to perform discharge teaching, you immediately reprioritize your care. You call the primary provider to report Patient B’s critical hemoglobin level and determine if additional intervention, such as a blood transfusion, is required.

Prioritization Principles & Staffing Considerations[13]

With the complexity of different staffing variables in health care settings, it can be challenging to identify a method and solution that will offer a resolution to every challenge. The American Nurses Association has identified five critical principles that should be considered for nurse staffing. These principles are as follows:

- Health Care Consumer: Nurse staffing decisions are influenced by the specific number and needs of the health care consumer. The health care consumer includes not only the client, but also families, groups, and populations served. Staffing guidelines must always consider the patient safety indicators, clinical, and operational outcomes that are specific to a practice setting. What is appropriate for the consumer in one setting, may be quite different in another. Additionally, it is important to ensure that there is resource allocation for care coordination and health education in each setting.

- Interprofessional Teams: As organizations identify what constitutes appropriate staffing in various settings, they must also consider the appropriate credentials and qualifications of the nursing staff within a specific setting. This involves utilizing an interprofessional care team that allows each individual to practice to the full extent of their educational, training, scope of practice as defined by their state Nurse Practice Act, and licensure. Staffing plans must include an appropriate skill mix and acknowledge the impact of more experienced nurses to help serve in mentoring and precepting roles.

- Workplace culture: Staffing considerations must also account for the importance of balance between costs associated with best practice and the optimization of care outcomes. Health care leaders and organizations must strive to ensure a balance between quality, safety, and health care cost. Organizations are responsible for creating work environments, which develop policies allowing for nurses to practice to the full extent of their licensure in accordance with their documented competence. Leaders must foster a culture of trust, collaboration, and respect among all members of the health care team, which will create environments that engage and retain health care staff.

- Practice environment: Staffing structures must be founded in a culture of safety where appropriate staffing is integral to achieve patient safety and quality goals. An optimal practice environment encourages nurses to report unsafe conditions or poor staffing that may impact safe care. Organizations should ensure that nurses have autonomy in reporting and concerns and may do so without threat of retaliation. The ANA has also taken the position to state that mandatory overtime is an unacceptable solution to achieve appropriate staffing. Organizations must ensure that they have clear policies delineating length of shifts, meal breaks, and rest period to help ensure safety in patient care.

- Evaluation: Staffing plans should be consistently evaluated and changed based upon evidence and client outcomes. Environmental factors and issues such as work-related illness, injury, and turnover are important elements of determining the success of need for modification within a staffing plan.[14]

Prioritization of patient care should be grounded in critical thinking rather than just a checklist of items to be done. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow."[15] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs. It can be challenging for a novice nurse to change their mindset regarding their established “plan” for the day, but the sooner a nurse recognizes prioritization is dictated by their patients’ needs, the less frustration the nurse might experience. Prioritization strategies include collection of information and utilization of clinical reasoning to determine the best course of action. Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[16] Clinical reasoning is fostered within nurses when they are challenged to integrate data in various contexts. The clinical reasoning cycle begins when nurses first consider a client situation and progress to collecting cues and information. As nurses process the information, they begin to identify problems and establish realistic goals. They then take appropriate actions and evaluate outcomes. Finally, they reflect upon the process and the learning that has occurred. The reflection piece is critical for solidifying or changing future actions and developing knowledge.

When nurses use critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills, they set forth on a purposeful course of intervention to best meet patient-care needs. Rather than focusing on one’s own priorities, nurses utilizing critical thinking and reasoning skills recognize their actions must be responsive to their patients. For example, a nurse using critical thinking skills understands that scheduled morning medications for their patients may be late if one of the patients on their care team suddenly develops chest pain. Many actions may be added or removed from planned activities throughout the shift based on what is occurring holistically on the patient-care team.

Additionally, in today’s complex health care environment, it is important for the novice nurse to recognize the realities of the current health care environment. Patients have become increasingly complex in their health care needs, and organizations are often challenged to meet these care needs with limited staffing resources. It can become easy to slip into the mindset of disenchantment with the nursing profession when first assuming the reality of patient-care assignments as a novice nurse. The workload of a nurse in practice often looks and feels quite different than that experienced as a nursing student. As a nursing student, there may have been time for lengthy conversations with patients and their family members, ample time to chart, and opportunities to offer personal cares, such as a massage or hair wash. Unfortunately, in the time-constrained realities of today's health care environment, novice nurses should recognize that even though these “extra” tasks are not always possible, they can still provide quality, safe patient care using the “CURE” prioritization framework. Rather than feeling frustrated about “extras” that cannot be accomplished in time-constrained environments, it is vital to use prioritization strategies to ensure appropriate actions are taken to complete what must be done. With increased clinical experience, a novice nurse typically becomes more comfortable with prioritizing and reprioritizing care.

Time management is not an unfamiliar concept to nursing students because many students are balancing time demands related to work, family, and school obligations. To determine where time should be allocated, prioritization processes emerge. Although the prioritization frameworks of nursing may be different than those used as a student, the concept of prioritization remains the same. Despite the context, prioritization is essentially using a structure to organize tasks to ensure the most critical tasks are completed first and then identify what to move onto next. To truly maximize time management, in addition to prioritization, individuals should be organized, strive for accuracy, minimize waste, mobilize resources, and delegate when appropriate.

Time management is one of the greatest challenges that nurses face in their busy workday. As novice nurses develop their practice, it is important to identify organizational strategies to ensure priority tasks are completed and time is optimized. Each nurse develops a personal process for organizing information and structuring the timing of their assessments, documentation, medication administration, interventions, and patient education. However, one must always remember that this process and structure must be flexible because in a moment’s time, a patient’s condition can change, requiring a reprioritization of care. An organizational tool is important to guide a nurse’s daily task progression. Organizational tools may be developed individually by the nurse or may be recommended by the organization. Tools can be rudimentary in nature, such as a simple time column format outlining care activities planned throughout the shift, or more complex and integrated within an organization’s electronic medical record. No matter the format, an organizational tool is helpful to provide structure and guide progression toward task achievement.

In addition to using an organizational tool, novice nurses should utilize other time management strategies to optimize their time. For example, assessments can start during bedside handoff report, such as what fluids and medications are running and what will need to be replaced soon. Take a moment after handoff reports to prioritize which patients you will see first during your shift. Other strategies such as grouping tasks, gathering appropriate equipment prior to initiating nursing procedures, and gathering assessment information while performing tasks are helpful in minimizing redundancy and increasing efficiency. For example, observe an experienced nurse providing care and note the efficient processes they use. They may conduct an assessment, bring in morning medications, flush an IV line, collect a morning blood glucose level, and provide patient education about medications all during one patient encounter. Efficiency becomes especially important if the patient has transmission-based precautions and the time spent donning and doffing PPE are considered. The realities of the time-constrained health care environments often necessitate clustering tasks to ensure that all patient-care tasks are completed. Furthermore, nurses who do not manage their time effectively may inadvertently place their patients at risk as a result of delayed care.[17] Effective time management benefits both the patient and the nursing staff.

Time estimation is an additional helpful strategy to facilitate time management. Time estimation involves the review of planned tasks for the day and allocating time estimated to complete the task. Time estimation is especially helpful for novice nurses as they begin to structure and prioritize their shift based on the list of tasks that are required.[18] For example, estimating the time it will take to perform an assessment and administer morning medications to one patient allows the nurse to better plan when to complete the dressing change on another patient. Without using time estimation, the nurse may attempt to group all care tasks with the morning assessments and not leave themselves enough time to administer morning medications within the desired administration time window. Additionally, working in a time-constrained environment without using time estimation strategies increases the likelihood of performing tasks “in a rush” and subsequently increasing the potential for error.

Who’s On My Team?

One of the most critical strategies to enhance time management is to mobilize the resources of the nursing team. The nursing care team includes advanced practice registered nurses (APRN), registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VN), and assistive personnel (AP). AP (formerly referred to as unlicensed assistive personnel [UAP]) include, but are not limited to, certified nursing assistants or aides (CNA), patient-care technicians (PCT), certified medical assistants (CMA), certified medication aides, and home health aides.[19] Each care environment may have a blend of staff, and it is important to understand the legalities associated with the scope and role of each member and what can be safely and appropriately delegated to other members of the team. For example, assistive personnel may be able to assist with ambulating a patient in the hallway, but they would not be able to help administer morning medications. Dividing tasks appropriately among nursing team members can help ensure that the required tasks are completed and individual energies are best allocated to meet patient needs. The nursing care team and requirements around the process of delegation are explored in detail in the "Delegation and Supervision" chapter.

Sam is a novice nurse who is reporting to work for his 0600 shift on the medical telemetry/progressive care floor. He is waiting to receive handoff report from the night shift nurse for his assigned patients. The information that he has received thus far regarding his patient assignment includes the following:

- Room 501: 64-year-old patient admitted last night with heart failure exacerbation. Patient received furosemide 80mg IV push at 2000 with 1600 mL urine output. He is receiving oxygen via nasal cannula at 2L/minute. According to the night shift aide, he has been resting comfortably overnight.

- Room 507: 74-year-old patient admitted yesterday for possible cardioversion due to new onset of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and is scheduled for transesophageal echocardiogram and possible cardioversion at 1000.

- Room 512: 82-year-old patient who is scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery today at 0700 and is receiving an insulin infusion.

- Room 536: 72-year-old patient who had a negative heart catheterization yesterday but experienced a groin bleed; plans for discharge this morning.

Based on the limited information Sam has thus far, he begins to prioritize his activities for the morning. With what is known thus far regarding his patient assignment, whom might Sam plan to see first and why? What principles of prioritization might be applied?

Although Sam would benefit from hearing a full report on his patients and reviewing the patient charts, he can already begin to engage in strategies for prioritization. Based on the information that has been shared thus far, Sam determines that none of the patients assigned to him are experiencing critical or urgent needs. All the patients' basic physiological needs are being met, but many have actual clinical concerns. Based on the time constraint with scheduled surgery and the insulin infusion for the patient in Room 512, this patient should take priority in Sam's assessments. It is important for Sam to ensure that this patient's pre-op checklist is complete, and he is stable with the infusion prior to transferring him for surgery. Although Sam may later receive information that alters this priority setting, based on the information he has thus far, he has utilized prioritization principles to make an informed decision.

You are an RN and are reporting to work on a 16-bed medical/renal unit in a county hospital for the 0700 - 1500 shift today. The client population is primarily socioeconomically disadvantaged. Staff for the shift includes four RNs, one LPN/VN, and two AP.

You are a new RN graduate on the unit, and your orientation was completed two weeks ago. The LPN/VN has been working on the unit for ten years. Both AP have been on the unit for six months and are certified nursing assistants after completing basic nurse aide training. You, as one of four RNs on the unit, have been assigned four clients. You share the LPN with the other RNs, and there is one AP for every two RNs.

The charge nurse has assigned you the following four clients. Scheduled morning medications are due at 0800 and all four require some assistance with their ADLs.

- Client A: An obese 52-year-old male with hypertension and diabetes requiring insulin therapy. He has been depressed since recently being diagnosed with end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis. He needs his morning medications and assistance getting dressed for transport to hemodialysis in 30 minutes.

- Client B: A 83-year-old female client with acute pyelonephritis admitted two days ago. She has a PICC line in place and is receiving IV vancomycin every 12 hours. The next dose is due at 0830 after a trough level is drawn.

- Client C: A 78-year-old male recently diagnosed with bladder cancer. He has bright red urine today but reports it is painless. He has surgery scheduled at 0900 and the pre-op checklist has not yet been completed.

- Client D: A malnourished 80-year-old male client admitted with dehydration and imbalanced electrolyte levels. He is being discharged home today and requires patient education.

Reflective Questions

- At the start of the shift, you determine which tasks, cares, activities, and/or procedures you will delegate to the LPN and AP. What factors must you consider prior to delegation?

- What tasks will you delegate to the LPN/VN?

- What tasks will you delegate to the AP?

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activities are provided as immediate feedback.)

- The nurse is conducting an assessment on a 70-year-old male client who was admitted with atrial fibrillation. The client has a history of hypertension and Stage 2 chronic kidney disease. The nurse begins the head-to-toe assessment and notes the patient is having difficulty breathing and is complaining about chest discomfort. The client states, “It feels as if my heart is going to pound out of my chest and I feel dizzy.” The nurse begins the head-to-toe assessment and documents the findings. Client assessment findings are presented in the table below. Select the assessment findings requiring immediate follow-up by the nurse.

Vital Signs

| Temperature | 98.9 °F (37.2°C) |

|---|---|

| Heart Rate | 182 beats/min |

| Respirations | 36 breaths/min |

| Blood Pressure | 152/90 mm Hg |

| Oxygen Saturation | 88% on room air |

| Capillary Refill Time | >3 |

| Pain | 9/10 chest discomfort |

| Physical Assessment Findings | |

|---|---|

| Glasgow Coma Scale Score | 14 |

| Level of Consciousness | Alert |

| Heart Sounds | Irregularly regular |

| Lung Sounds | Clear bilaterally anterior/posterior |

| Pulses-Radial | Rapid/bounding |

| Pulses-Pedal | Weak |

| Bowel Sounds | Present and active x 4 |

| Edema | Trace bilateral lower extremities |

| Skin | Cool, clammy |

2. The following nursing actions may or may not be required at this time based on the assessment findings. Indicate whether the actions are "Indicated" (i.e., appropriate or necessary), "Contraindicated" (i.e., could be harmful), or "Nonessential" (i.e., makes no difference or are not necessary).

| Nursing Action | Indicated | Contraindicated | Nonessential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apply oxygen at 2 liters per nasal cannula. | |||

| Call imaging for a STAT lung CT. | |||

| Perform the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale Neurologic Exam. | |||

| Obtain a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP). | |||

| Obtain a STAT EKG. | |||

| Raise the head-of-bed to less than 10 degrees. | |||

| Establish patent IV access. | |||

| Administer potassium 20 mEq IV push STAT. |

3. The CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to help guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras.

You are the nurse caring for the patients in the following table. For each patient, indicate if this is a "critical," "urgent," "routine," or "extra" need.

<td">

| Critical | Urgent | Routine | Extra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient exhibits new left-sided facial droop | ||||

| Patient reports 9/10 acute pain and requests PRN pain medication | ||||

| Patient with BP 120/80 and regular heart rate of 68 has scheduled dose of oral amlodipine | ||||

| Patient with insomnia requests a back rub before bedtime | ||||

| Patient has a scheduled dressing change for a pressure ulcer on their coccyx |

||||

| Patient is exhibiting new shortness of breath and altered mental status | ||||

| Patient with fall risk precautions ringing call light for assistance to the restroom for a bowel movement |

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[20]

ABCs: Airway, breathing, and circulation.

Actual problems: Nursing problems currently occurring with the patient.

Acuity: The level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition.

Acuity-rating staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments that reflects the individualized nursing care required for different types of patients.

Acute conditions: Conditions having a sudden onset.

Chronic conditions: Conditions that have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time.

Clinical reasoning: “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[21]

Critical thinking: A broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”[22]

CURE hierarchy: A strategy for prioritization based on identifying “critical” needs, “urgent” needs, “routine” needs, and “extras.”

Data cues: Pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition.

Expected conditions: Conditions that are likely to occur or anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Prioritization strategies often reflect the foundational elements of physiological needs and safety and progress toward higher levels.

Ratio-based staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments in terms of one nurse caring for a set number of patients.

Risk problem: A nursing problem that reflects that a patient may experience a problem but does not currently have signs reflecting the problem is actively occurring.

Time estimation: A prioritization strategy including the review of planned tasks and allocation of time believed to be required to complete each task.

Time scarcity: A feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against you.

Unexpected conditions: Conditions that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury.

Learning Objectives

- Explain principles of delegation

- Evaluate the criteria used for delegation

- Apply effective communication techniques when delegating care

- Determine specific barriers to delegation

- Evaluate team members' performance based on delegation and supervision principles

- Incorporate principles of supervision and evaluation in the delegation process

- Identify scope of practice of the RN, LPN/VN, and unlicensed assistive personnel roles

- Identify tasks that can and cannot be delegated to members of the nursing team

As health care technology continues to advance, clients require increasingly complex nursing care, and as staffing becomes more challenging, health care agencies respond with an evolving variety of nursing and assistive personnel roles and responsibilities to meet these demands. As an RN, you are on the front lines caring for ill or injured clients and their families, advocating for clients’ rights, creating nursing care plans, educating clients on how to self-manage their health, and providing leadership throughout the complex health care system. Delivering safe, effective, quality client care requires the RN to coordinate care by the nursing team as tasks are assigned, delegated, and supervised. Nursing team members include advanced practice registered nurses (APRN), registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VN), and assistive personnel (AP).[23]

Assistive personnel (AP) (formerly referred to as ‘‘unlicensed” assistive personnel [UAP]) are any assistive personnel trained to function in a supportive role, regardless of title, to whom a nursing responsibility may be delegated. This includes, but is not limited to, certified nursing assistants or aides (CNAs), patient-care technicians (PCTs), certified medical assistants (CMAs), certified medication aides, and home health aides.[24] Making assignments, delegating tasks, and supervising delegatees are essential components of the RN role and can also provide the RN more time to focus on the complex needs of clients. For example, an RN may delegate to AP the attainment of vital signs for clients who are stable, thus providing the nurse more time to closely monitor the effectiveness of interventions in maintaining complex clients' hemodynamics, thermoregulation, and oxygenation. Collaboration among the nursing care team members allows for the delivery of optimal care as various skill sets are implemented to care for the patient.

Properly assigning and delegating tasks to nursing team members can promote efficient client care. However, inappropriate assignments or delegation can compromise client safety and produce unsatisfactory client outcomes that may result in legal issues. How does the RN know what tasks can be assigned or delegated to nursing team members and assistive personnel? What steps should the RN follow when determining if care can be delegated? After assignments and delegations are established, what is the role and responsibility of the RN in supervising client care? This chapter will explore and define the fundamental concepts involved in assigning, delegating, and supervising client care according to the most recent joint national delegation guidelines published by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) and the American Nurses Association (ANA).[25]

Effective communication is a vital component of proper assignment, delegation, and supervision. It is also one of the Standards of Professional Performance established by the American Nurses Association (ANA).[26] Research has identified that new graduate nurses are more susceptible to stress and isolation within their job roles due to poor communication and teamwork within the interdisciplinary team.[27] Strong communication skills foster a supportive work environment and colleagial relationships that benefit both patients and nursing staff.

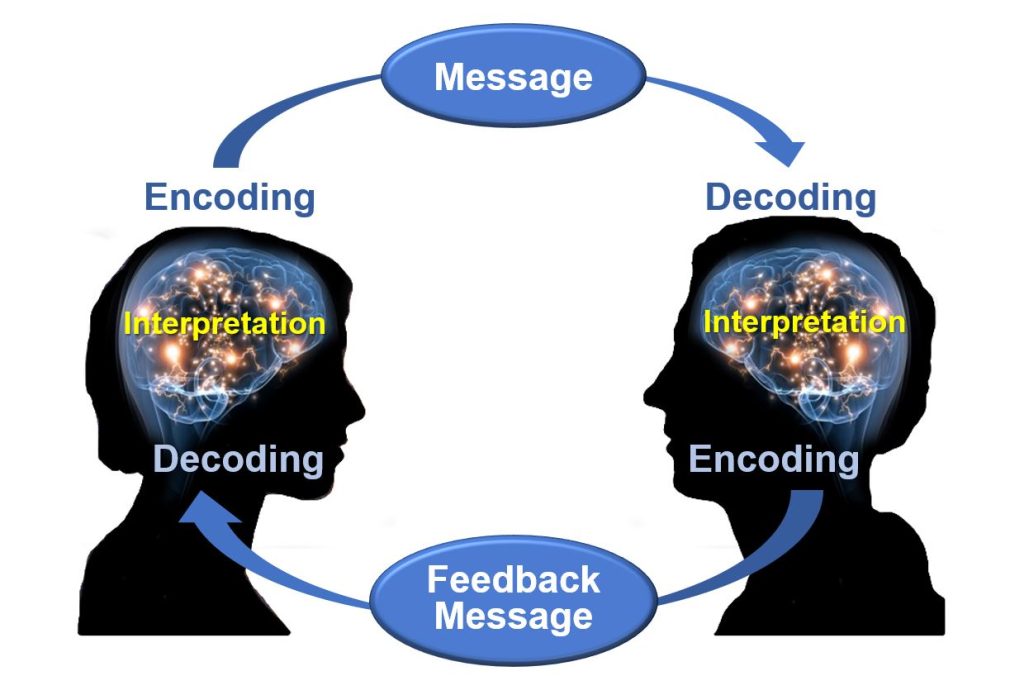

Consider the fundamentals of good communication practices. Effective communication requires each interaction to include a sender of the message, a clear and concise message, and a receiver who can decode and interpret that message. The receiver also provides a feedback message back to the sender in response to the received message. See Figure 3.1[28] for an image of effective communication between a sender and receiver. This feedback message is referred to as closed-loop communication in health care settings. Closed-loop communication enables the person giving the instructions to hear what they said reflected back and to confirm that their message was received correctly. It also allows the person receiving the instructions to verify and confirm the actions to be taken. If closed-loop communication is not used, the receiver may nod or say “OK,” and the sender may assume the message has been effectively transmitted, but this may not be the case and can lead to errors and client harm.

An example of closed-loop communication can be found in the following exchange:

- RN: “Jane, can you get a set of vitals on Mr. Smith and let me know if the results are outside of normal range?”

- Jane, CNA: “OK, I’ll get a set of vitals on Mr. Smith and let you know if they are out of range.”

Closed-loop communication is vital for communication among health care team members to avoid misunderstandings that can cause unsafe client care. According to the HIPAA Journal, poor communication leads to a “reduction in the quality of care, poor client outcomes, wastage of resources, and high health care costs.”[29] Parameters for reporting results and the results that should be expected are often left unsaid rather than spelled out in sufficient detail. It is imperative for the RN to provide clear, complete, concise instructions when delegating. A lack of clarity can lead to misunderstanding, unfinished tasks, incomplete care, and/or medical errors.[30]

Effective communication is at the core of proper assignment, delegation, and supervision. With effective communication at the beginning of every shift, each nursing team member should have a clear plan for their shift, what to do and why, and what and when to report to the RN or team leader. Communication should continue throughout the shift as tasks are accomplished and patients’ needs change. Effective communication improves client outcomes and satisfaction scores, as well as improving team morale by enhancing the collaborative relationships of the health care team.

The RN is accountable for clear, concise, correct, and complete communication when making assignments and delegating, both initially and throughout the shift. These communication characteristics can be remembered by using the mnemonic the "4 Cs":

- Clear: Information is understood by the listener. Asking the listener to restate the instructions and the plan can be helpful to determine whether the communication is clear.

- Concise: Sufficient information should be provided to accurately perform the task, but excessive or irrelevant information should be avoided because it can confuse the listener and waste precious time.

- Correct: Correct communication is not vague or confusing. Accurate information is also aligned with agency policy and the team member’s scope of practice as defined by their state’s Nurse Practice Act and other state regulations.

- Complete: Complete instructions leave no room for doubt. Always ask if further information or clarification is needed, especially regarding tasks that are infrequently performed or include unique instructions.[31]

The use of closed-loop communication is the best method to achieve clear, concise, correct, and complete information exchanged among team members. Closed-loop communication allows team members the opportunity to verify and validate the exchange of information. By repeating back information, members confirm the exchange has occurred, understanding is clear, and expectations are heard.

Closed-loop communication should also be used when the RN is receiving a verbal order from a provider. For example, when the resuscitation team leader gives a verbal order of “Epinephrine 1 mg/mL IV push now,” the RN confirms correct understanding of the order by repeating back, “I will prepare Epinephrine 1 mg/mL to be given IV push now.” After the provider confirms the verbal order and the task is completed, the nurse confirms completion of the task by stating, “Epinephrine 1 mg/mL IV push was administered.”

In addition to using closed-loop communication, a common format used by health care team members to exchange client information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat Back. ISBARR and other communication strategies are discussed in more detail in the "Interprofessional Communication" section of the "Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team" chapter.

Nursing team members working in inpatient or long-term care settings receive patient assignments at the start of their shift. Assignment refers to routine care, activities, and procedures that are within the legal scope of practice of registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VN), or assistive personnel (AP).[32] Scope of practice for RNs and LPNs is described in each state's Nurse Practice Act. Care tasks for AP vary by state; regulations are typically listed on sites for the state's Board of Nursing, Department of Health, Department of Aging, Department of Health Professions, Department of Commerce, or Office of Long-Term Care.[33]

See Table 3.3a for common tasks performed by members of the nursing team based on their scope of practice. These tasks are within the traditional role and training the team member has acquired through a basic educational program. They are also within the expectations of the health care agency during a shift of work. Agency policy can be more restrictive than federal or state regulations, but it cannot be less restrictive.

Patient assignments are typically made by the charge nurse (or nurse supervisor) from the previous shift. A charge nurse is an RN who provides leadership on a patient-care unit within a health care facility during their shift. Charge nurses perform many of the tasks that general nurses do, but also have some supervisory duties such as making assignments, delegating tasks, preparing schedules, monitoring admissions and discharges, and serving as a staff member resource.[34]

Table 3.3a. Nursing Team Members’ Scope of Practice and Common Tasks[35]

| Nursing Team Member | Scope of Practice | Common Tasks

|

|---|---|---|

| RN |

|

|

| LPN/VN |

|