6.2 Review of Anatomy and Physiology of the Respiratory System

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

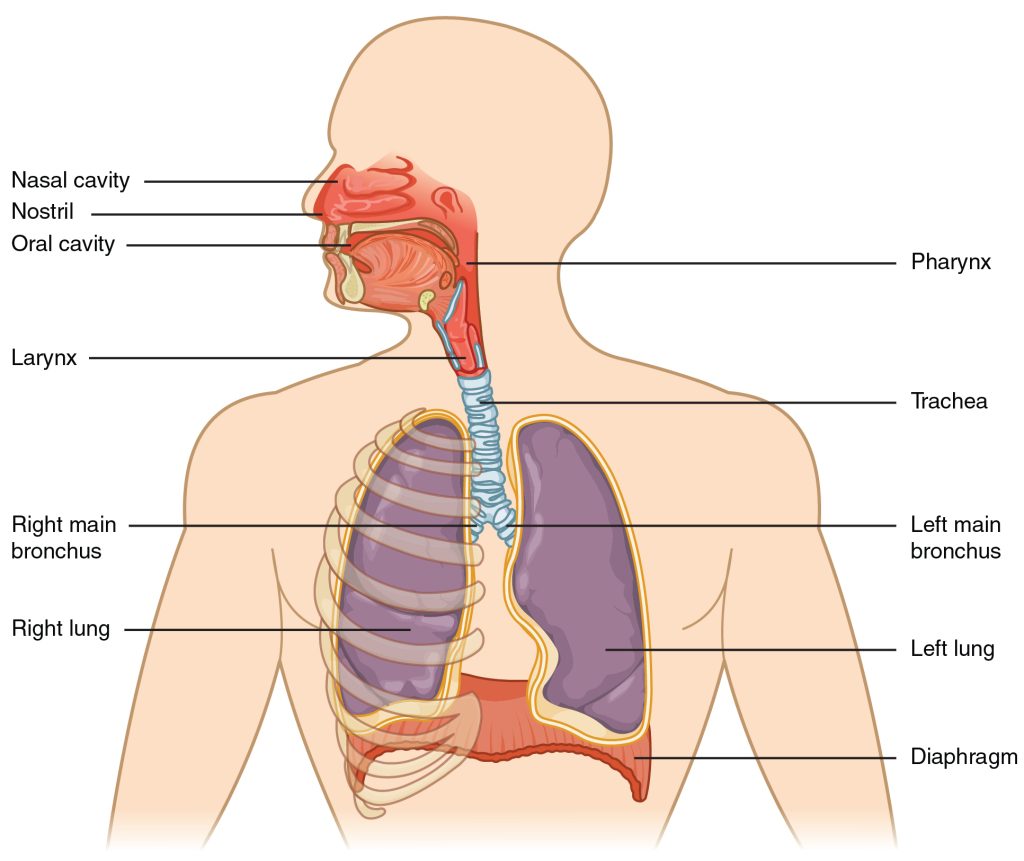

This section will review the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system. Common disorders affecting these anatomic structures are also introduced. See Figure 6.1[1] for an illustration of the major structures of the respiratory system.

Nose, Nasal Cavity, and Sinuses

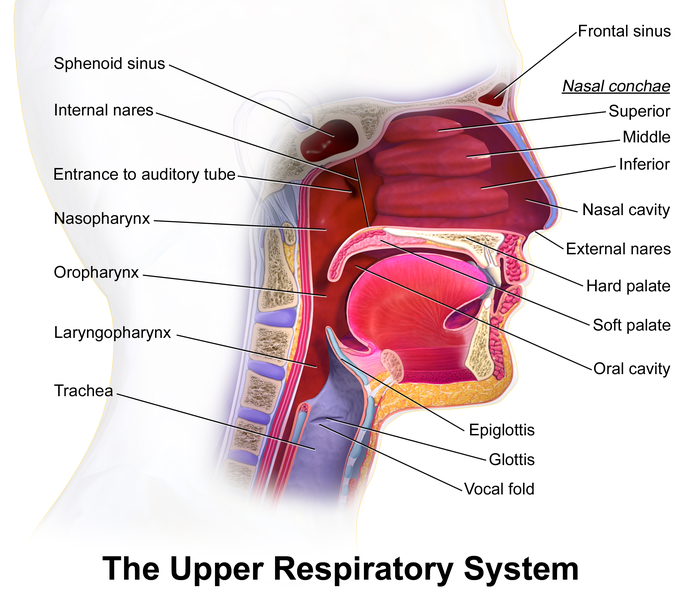

The upper respiratory system refers to the nose, nasal cavities, sinuses, pharynx, and larynx. See Figure 6.2[2] for an illustration of anatomic structures of the upper respiratory system. An upper respiratory infection (URI) refers to a viral infection of one or more of these structures.

The entrance and exit for the respiratory system are through the nose. The nostrils are the opening to the nose, also referred to as nares. The nares and nasal cavities are lined with mucous membranes, containing sebaceous glands and hair follicles that serve to prevent the passage of large debris, such as dirt, through the nasal cavity. Rhinorrhagia refers to bleeding from the nose, also called epistaxis. Rhinitis refers to inflammation of the nasal mucosa.

The nares open into the nasal cavity, which is separated into left and right sections by the nasal septum. The floor of the nasal cavity is composed of the hard palate and the soft palate. The nasal cavities are lined with mucous membranes that produce mucus, a substance created for lubrication and protection. Rhinorrhea, commonly referred to as a “runny nose,” is a medical term for excess mucus production by the nasal cavities.

Adjacent to the nasal cavity are the sinuses that serve to warm and humidify incoming air. There are four sinuses named for their adjacent bones: frontal sinus, maxillary sinus, sphenoidal sinus, and ethmoidal sinus. Air moves from the nasal cavities and sinuses into the pharynx. Sinusitis refers to inflammation of the sinus cavities.[3]

Pharynx

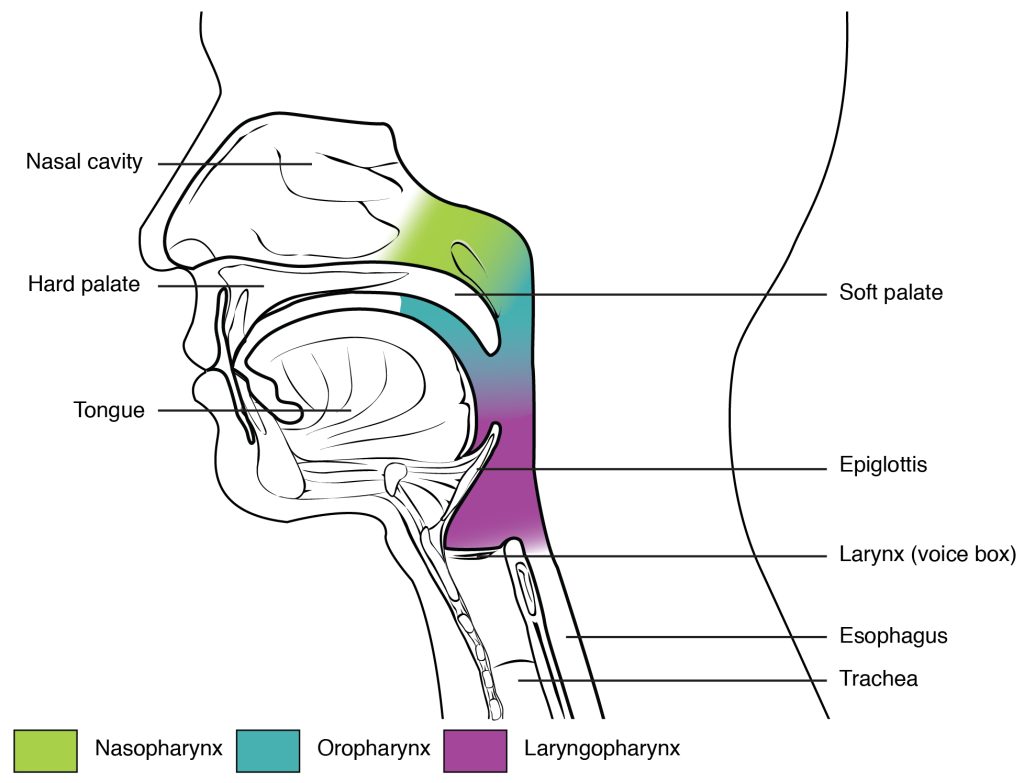

The pharynx, commonly known as the throat, is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx. See Figure 6.3[4] for an illustration of the regions of the pharynx.[5]

At the top of the nasopharynx is the pharyngeal tonsil, also called adenoid. The function of the pharyngeal tonsil is to trap and destroy invading pathogens that enter the airway during inhalation. Pharyngitis is inflammation of the pharynx, and tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils.[6]

The soft palate and a bulbous structure called the uvula swing upward during swallowing to close off the nasopharynx to prevent ingested materials from entering the nasal cavity. Eustachian tubes connect the middle ear cavities with the nasopharynx. This connection is why upper respiratory infections often lead to ear infections.[7]

The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity. The oropharynx contains two distinct sets of tonsils called the palatine tonsils and lingual tonsils that also trap and destroy pathogens entering the body through the oral or nasal cavities. Adenoids are lymphatic tissue between the back of the nasal cavity and the pharynx. Adenoiditis refers to inflammation of the adenoids, a common medical condition in young children that can hinder speaking and breathing.[8]

The laryngopharynx is just below the oropharynx. It is part of the pharynx (throat) located behind the larynx. The laryngopharynx separates into the trachea (the tube going into the larynx) and the esophagus (the tube going into the stomach). The epiglottis prevents food and fluid from entering the trachea while swallowing.[9]

Larynx

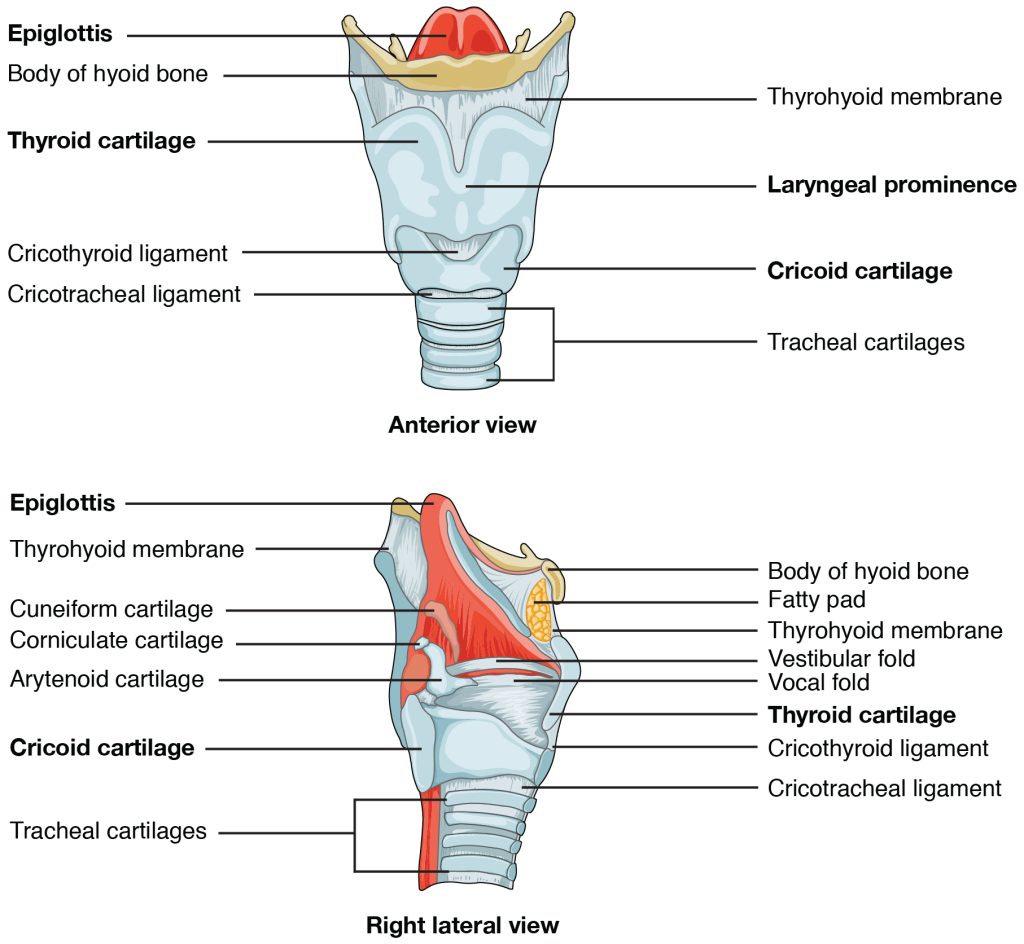

The structure of the larynx is formed by several pieces of cartilage, as shown in Figure 6.4.[10] Three large cartilage pieces form the major structure of the larynx called the thyroid cartilage (the larger piece of cartilage on the anterior side), epiglottis (at the top of the larynx), and cricoid cartilage (just inferior to the thyroid cartilage). Laryngitis refers to inflammation of the larynx, specifically the vocal cords, typically resulting in huskiness or loss of one’s voice and a cough.[11]

The epiglottis is a flap of tissue that covers the trachea during swallowing to prevent aspiration, the inhalation of food or fluids into the trachea and lower respiratory tract. The act of swallowing causes the pharynx and larynx to lift upward, allowing the pharynx to expand and the epiglottis of the larynx to swing downward, closing the opening to the trachea.[12]

Vocal cords are white, membranous folds attached by muscle to the cartilages of the larynx on their outer edges. The inner edges of the vocal cords are free, allowing oscillation as air passes through to produce sound for speaking.[13]

The lower respiratory tract consists of the trachea, bronchi, alveoli, and lungs.[14]

Trachea

The trachea is formed by stacked, C-shaped pieces of cartilage that are connected by dense connective tissue. See Figure 6.5[15] for an illustration of the trachea. The trachea stretches and expands slightly during inhalation and exhalation, whereas the rings of cartilage provide structural support and prevent the trachea from collapsing. The trachea is lined with cilia and mucus-secreting cells to trap debris and move it towards the pharynx to be swallowed or spit out.[16]

If the upper respiratory tract becomes blocked with mucus, inflammation, or a foreign object, no air can pass to the lungs, causing a life-threatening emergency requiring a tracheostomy. A tracheostomy is an incision created in the trachea to create an artificial opening to allow breathing when an obstruction is present.[17]

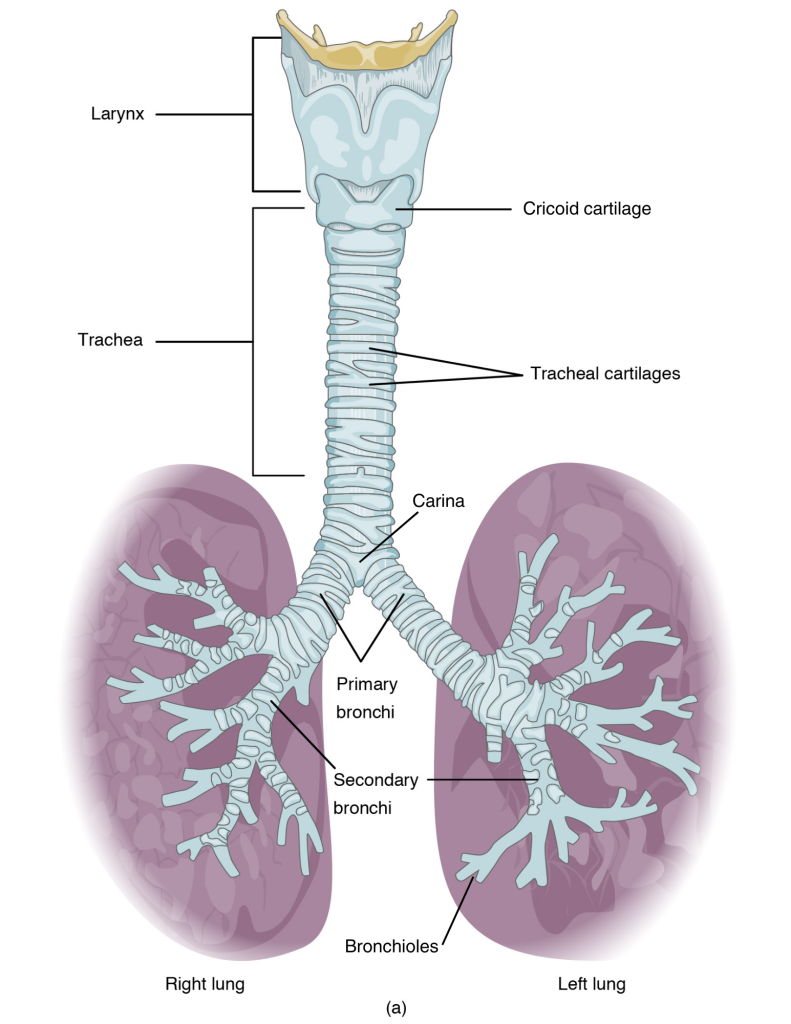

Bronchi and Bronchioles

Bronchi are the main air passageways of the lungs. The trachea branches into the right and left primary bronchi at the carina. The carina is a raised structure that contains specialized nervous system tissue that induces violent coughing if a foreign body, such as food, is present. Rings of cartilage, similar to those of the trachea, support the structure of the bronchi and prevent their collapse. The bronchi of each lung continue to branch up to 26 times creating the bronchial tree, which looks similar to the branching of an actual tree. The main function of the bronchi is to provide a passageway for air to move into and out of each lung.[18]

Bronchioles are the smallest branches of the bronchi that lead to the alveolar sacs. The muscular walls of these tiny bronchioles do not contain cartilage like those of the bronchi, so the muscular wall can change the size of the bronchioles to increase or decrease airflow to the alveoli. Bronchospasm is a symptom of many respiratory conditions that refers to a sudden constriction of the muscles in the walls of the bronchioles. Bronchitis refers to inflammation of the bronchi.[19]

The trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles are lined with mucous membranes that create mucus secretions that can be expelled through the mouth, also referred to as sputum.[20]

Alveoli

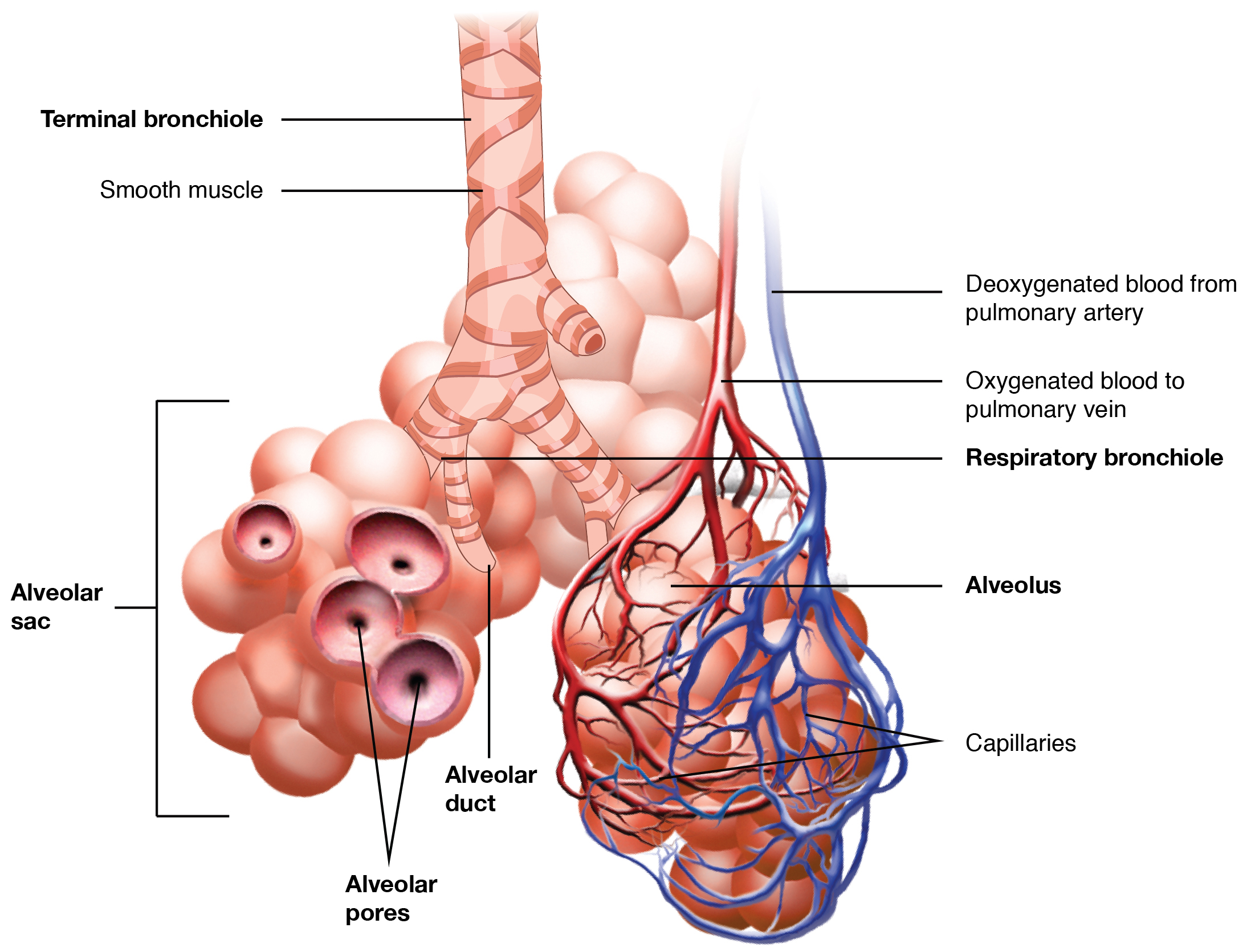

Alveoli are small, grape-like sacs where gas exchange occurs. See Figure 6.6[21] for an illustration of one alveolus surrounded by capillaries. The blue capillaries refer to deoxygenated blood transported to the lungs from the pulmonary artery, and the red capillaries refer to oxygenated blood that is being transported back to the heart via the pulmonary vein. Note in this case that a vein is carrying oxygenated blood. Veins always carry blood back to the heart, but most of the time, it is deoxygenated. However, in this case, the pulmonary vein is transporting blood that is oxygenated back to the heart because it is being transported from the lungs.[22]

Alveoli have elastic walls that allow the alveolus to stretch during air intake, which greatly increases the surface area available for gas exchange. Alveoli secrete surfactant, a slippery substance that keeps the lungs from collapsing. Atelectasis is a medical term that refers to the collapse of alveoli and/or small passageways of the lungs that can result in a partially or completely collapsed lung.[23]

Lungs

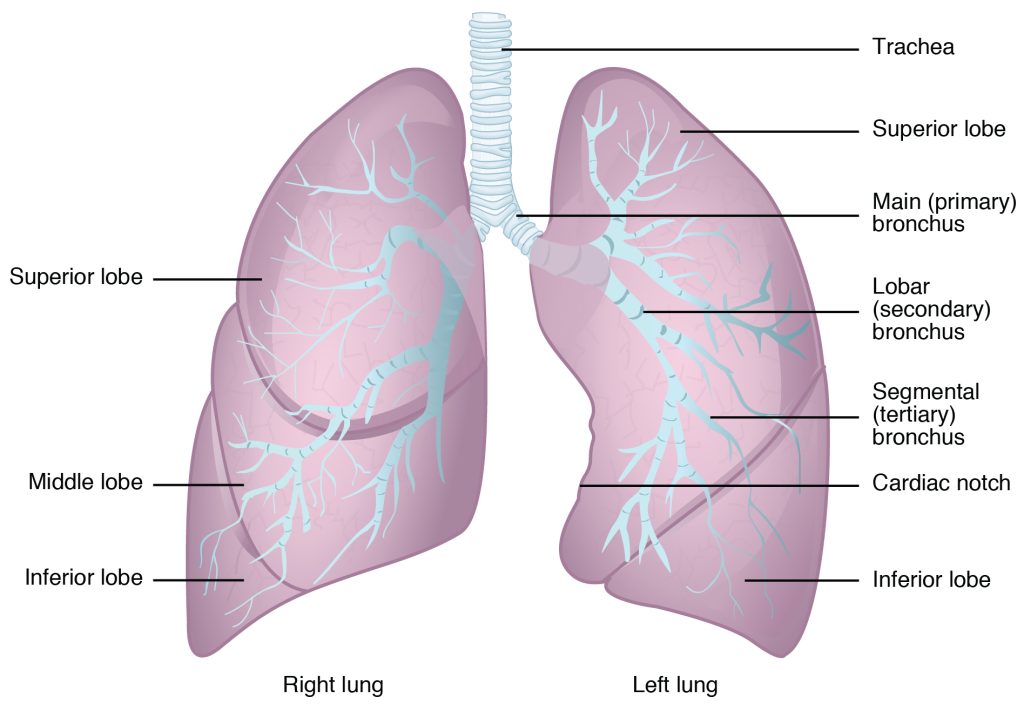

The lungs are connected to the trachea by the main (primary) bronchi that branches into the right and left bronchi. See Figure 6.7[24] for an illustration of the lungs. On the inferior surface, the lungs are bordered by the diaphragm. The cardiac notch, a medial indentation found only on the left lung, allows space for the heart. The apex of the lung is the superior region, whereas the base is the distal region near the diaphragm.[25]

Each lung is composed of smaller units called lobes. The right lung consists of three lobes: the superior, middle, and inferior lobes. The left lung is smaller and only contains two lobes, superior and inferior, as it shares space with the heart. Each lobe receives its own large bronchus that has multiple branches. A lobectomy refers to surgical removal of a lobe of the lung.[26]

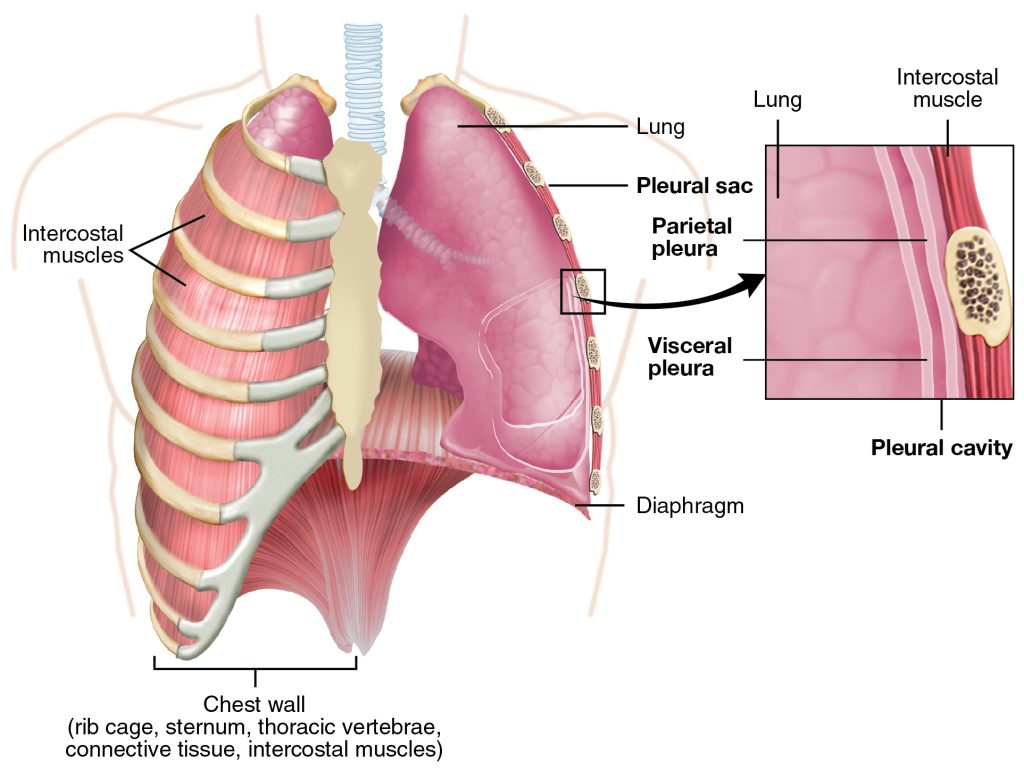

There are two pleural membranes in the lungs. The visceral pleura is a thin membrane on the outer surface of the lungs. The parietal pleura lines the inside of the thoracic cavity. Between these two membranes is the pleural cavity that contains pleural fluid to reduce friction and also sticks to the lungs to help keep them inflated. See Figure 6.8[27] for an illustration of the pleural membranes and the pleural cavity. Pleural effusion refers to excessive fluid between the pleural membranes that is commonly caused by disease or trauma.[28]

The main function of the respiratory system is gas exchange, meaning providing the body with a constant supply of oxygen to the body and removing carbon dioxide. To achieve gas exchange, the structures of the respiratory system create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation.[29]

Ventilation and the Mechanics of Breathing

The lungs bring oxygen to the cells of our body through inhalation and exhalation. Inhalation, also called inspiration, is the act of breathing air inward. During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts and flattens, creating a larger lung cavity, which decreases the pressure inside the lungs. At the same time, the intercostal muscles (the muscles between the ribs) pull downward, also causing the thoracic cavity to expand. The thoracic cavity is the space inside the chest that contains the heart, lungs, and other organs. As the thoracic cavity expands, a negative pressure (i.e., vacuum) is created inside the chest cavity, causing air to rush into the lungs (because air always moves from high pressure to low pressure).[30]

During exhalation, also called expiration or the act of breathing out, the diaphragm relaxes and the thoracic cavity springs back to its original position. This causes the volume of the thoracic cavity to decrease and pressure to increase, causing air to leave the lungs.

Lung sounds are caused by the movement of air from the trachea to the bronchioles to the alveoli and can be impacted by the presence of sputum, bronchoconstriction, or fluid in the alveoli. These sounds are referred to as rhonchi (coarse crackles), rales (fine crackles), wheezes, stridor, and pleural rub[31]:

- Rhonchi, also referred to as coarse crackles, are low-pitched, continuous sounds heard on expiration that are a sign of turbulent airflow through mucus in the large airways.

- Rales, also called fine crackles, are popping or crackling sounds heard on inspiration. They are associated with medical conditions that cause fluid accumulation within the alveolar and interstitial spaces, such as heart failure or pneumonia. The sound is similar to that produced by rubbing strands of hair together close to your ear.

- Wheezes are whistling noises produced when air is forced through airways narrowed by bronchoconstriction or mucosal edema. For example, clients with asthma commonly have wheezing.

- Stridor is heard only on inspiration. It is associated with obstruction of the trachea/upper airway.

- Pleural rub sounds like the rubbing together of leather and can be heard on inspiration and expiration. It is caused by inflammation of the pleura membranes that results in friction as the surfaces rub against each other.

Listen to lungs sounds in the “Respiratory Assessment” section of the “Respiratory Assessment” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Forced breathing is a type of breathing that can occur during exercise, singing, or playing a musical instrument. During forced breathing, inspiration and expiration both occur due to muscle contractions. In addition to the contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, other accessory muscles must also contract. Muscles of the neck contract and lift the thoracic wall, increasing lung volume, and accessory muscles of the abdomen contract, forcing abdominal organs upward against the diaphragm. This helps to push the diaphragm farther into the thorax, pushing out more air. In addition, accessory muscles help to compress the rib cage, which also reduces the volume of the thoracic cavity. These additional muscle contractions during inspiration also occur during labored breathing, a symptom of many respiratory disorders.[32]

Control of Breathing

Respiratory rate is the number of breaths taken per minute. The normal respiratory rate for adults is 12-20 breaths per minute. A child under 1 year of age has a normal respiratory rate between 30 and 60 breaths per minute. By the time a child is about eleven years old, the normal rate is closer to 14 to 22.

Respiratory rate may increase or decrease during illness or disease. Medical terms related to breathing include tachypnea (rapid breathing), bradypnea (slow breathing), and apnea (episodes of the absence of breathing). Dyspnea is a common symptom of respiratory disorders and refers to shortness of breath or a feeling of breathlessness.[33]

The respiratory rate is controlled by the respiratory center located within the medulla oblongata and pons in the brain stem, which responds primarily to changes in carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH levels in the blood. These changes are sensed by central chemoreceptors, which are located in the brain, and peripheral chemoreceptors, which are located in the aortic arch and carotid arteries.

The major factor that drives breathing is not hypoxemia (a decreased amount of dissolved oxygen in the blood), but rather the concentration of carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is a waste product of cellular respiration and is toxic at high levels in the blood. Elevated levels of carbon dioxide are called hypercapnia. As carbon dioxide levels increase, the central chemoreceptors stimulate the contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, increasing the rate and depth of respirations to help rid the body of carbon dioxide. Hyperventilation refers to rapid and deep breathing. It can occur for many reasons such as anxiety and pain, but it can also be a sign the body is trying to compensate for acidosis and increasing the pH level by eliminating excess carbon dioxide.

In contrast, low levels of carbon dioxide in the blood stimulate shallow, slow breathing to help the body retain carbon dioxide. Hypoventilation refers to slow and shallow breathing.[34] Hypoventilation can occur for several reasons, such as oversedation by opioids and exhaustion from hyperventilation. It can also be a sign the body is trying to compensate for alkalosis by retaining carbon dioxide and decreasing the pH level.

Gas Exchange

Ventilation (i.e., the mechanics of breathing) provides air to the alveoli for gas exchange. Respiration refers to the exchange of gases in the lungs between the alveoli and the pulmonary capillaries or in the tissues between the systemic capillaries and cells/tissues.

Gas exchange refers to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide through capillary walls of the alveoli and the pulmonary capillaries, called external respiration. During external respiration, oxygen from the air we breathe diffuses into the blood. Carbon dioxide (waste) diffuses out of the blood and into the alveoli where it can be exhaled. Throughout the rest of the body, gas exchange also occurs between the systemic capillaries and body cells/tissues, called internal respiration. During internal respiration, oxygen diffuses out of the systemic capillaries and body cells/tissues, and carbon dioxide diffuses from the cells/tissues into the systemic capillaries where it is carried to the lungs. It is through this process that cells in the body are oxygenated and carbon dioxide, the waste product of cellular respiration, is removed from the body.[35]

Perfusion

In addition to adequate ventilation, the second important aspect of gas exchange is perfusion. Perfusion refers to the flow of blood. In the lungs, perfusion occurs in the pulmonary circulation as it moves from the heart into the lungs and then back to the heart for distribution to the body. The pulmonary arteries carry deoxygenated blood from the heart into the lungs, where they branch and eventually become the capillary network composed of pulmonary capillaries. These pulmonary capillaries create the respiratory membrane with the alveoli. As the blood is pumped through this capillary network, gas exchange occurs.[36]

Although a small amount of the oxygen is able to dissolve directly into the blood from the alveoli, most of the oxygen binds to hemoglobin within the red blood cells. The more oxygen the hemoglobin in the red blood cells carry, the brighter red the color of the blood. Oxygenated blood returns to the heart through the pulmonary veins to the left atrium and ventricle, where it is pumped out to the body via the aorta. The hemoglobin on the red blood cells transports the oxygen to the tissues throughout the body.[37]

Hypoxia and Hypoxemia

Diseases and disorders affecting the respiratory system can cause hypoxia, defined as reduced tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia can occur due to inadequate ventilation or impaired perfusion, also referred to as V-Q mismatch, where the ratio of air ventilating the lungs’ alveoli (V) to blood perfusing through the surrounding capillaries (Q) is not properly matched.

Pulmonary edema is an example of hypoxia caused by inadequate ventilation due to fluid accumulation in alveoli, often caused by heart failure or kidney failure. As a result of the fluid accumulation, oxygen cannot move across the alveolar membrane into the blood, and carbon dioxide cannot be removed from the blood. As a result, hypoxia and hypercapnia (high levels of carbon dioxide) may occur, requiring urgent medical interventions to sustain life by decreasing carbon dioxide levels and increasing oxygen levels.[38]

Another example of hypoxia caused by impaired perfusion is a pulmonary embolism. Let’s take a closer look at pulmonary embolism in the box below.

Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism (PE) can occur when a clot from elsewhere in the body travels through venous circulation and gets lodged in the blood vessels of the lungs. This impedes blood flow, and impacted lung tissue dies. PEs are medical emergencies that require emergent treatment. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism involves various tests:

- CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA): Visualizes blood flow in the pulmonary arteries.

- D-dimer test: Detects the presence of a substance that may indicate the presence of a blood clot.

- Ultrasound: Checks for DVT in the legs.

- Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan: Detects blood flow and air movement in the lungs.

Signs and symptoms of PE include sudden shortness of breath, sudden anxiety or feeling of “impending doom,” chest pain, rapid heart rate, coughing up blood, sweating, feeling lightheaded or dizzy, or leg swelling or pain if a DVT is present. Read more about DVT in the “Cardiovascular Alterations” chapter. Complications of PE include death of lung tissue, increased pulmonary pressure in the arteries of the lungs, and cardiac arrest. Rapid intervention is required if PE is suspected. Treatment includes blood thinners to prevent additional clotting, thrombolytic therapy to dissolve clots, inferior vena cava (IVC) filter to prevent clots traveling to the lungs, oxygen therapy, and supportive measures such as pain management and breathing exercises.[39]

The term hypoxia and hypoxemia are not synonymous. Whereas hypoxia refers to reduced tissue oxygenation, hypoxemia is defined as a decrease in the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2). Hypoxemia can be caused by impaired delivery of oxygen to the tissues or defective utilization of oxygen by tissues. Additionally, hypoxemia and hypoxia do not always coexist. For example, clients can develop hypoxemia without hypoxia if there is a compensatory increase in their hemoglobin levels and/or cardiac output (CO).[40]

- “2301_Major_Respiratory_Organs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Blausen_0872_UpperRespiratorySystem.png” by Blausen.com staff (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014 is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "2305_Divisions_of_the_Pharynx.jpg" by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2306_The_Larynx.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Trachea” by Meredith Pomietlo is a derivative of "File:2308a_The Trachea" by OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2309_The_Respiratory_Zone” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2312_Gross_Anatomy_of_the_Lungs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "2313_The_Lung_Pleurea.jpg" by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Open RN Nursing Skills 2e by Chippewa Valley Technical College with CC BY 4.0 licensing. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, June 28). Venous thromboembolism. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/facts.html ↵

- Sarkar, M., Niranjan, N., & Banyal, P. K. (2017). Mechanisms of hypoxemia. Lung India, 34(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.197116 ↵

This textbook discusses professional and management concepts related to the role of a registered nurse (RN) as defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA). The ANA publishes two resources that set standards and guide professional nursing practice in the United States: The Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements and Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. The Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements establishes an ethical framework for nursing practice across all roles, levels, and settings and is discussed in greater detail in the “Ethical Practice” chapter of this book. The Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice resource defines the “who, what, where, when, why, and how of nursing” and sets the standards for practice that all registered nurses are expected to perform competently.[1]

The ANA defines the “who” of nursing practice as the nurses who have been educated, titled, and maintain active licensure to practice nursing. The “what” of nursing is the recently revised ANA definition of nursing: “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.”[2] Simply put, nurses treat human responses to health problems and life processes and advocate for the care of others.

Nursing practice occurs “when'' there is a need for nursing knowledge, wisdom, caring, leadership, practice, or education, anytime, anywhere. Nursing practice occurs in any environment “where'' there is a health care consumer in need of care, information, or advocacy. The “why” of nursing practice is described as nursing’s response to the changing needs of society to achieve positive health care consumer outcomes in keeping with nursing’s social contract and obligation to society. The “how” of nursing practice is defined as the ways, means, methods, and manners that nurses use to practice professionally.[3] The “how” of nursing, also referred to as a nurse’s “scope and standards of practice,” is further defined by each state’s Nurse Practice Act; agency policies, procedures, and protocols; and federal regulations and ANA’s Standards of Practice.

State Boards of Nursing and Nurse Practice Acts

RNs must legally follow regulations set by the Nurse Practice Act by the state in which they are caring for patients with their nursing license. The Board of Nursing is the state-specific licensing and regulatory body that sets standards for safe nursing care and issues nursing licenses to qualified candidates based on the Nurse Practice Act. The Nurse Practice Act is enacted by that state’s legislature and defines the scope of nursing practice and establishes regulations for nursing practice within that state. If nurses do not follow the standards and scope of practice set forth by the Nurse Practice Act, they may be disciplined by the Board of Nursing in the form of reprimand, probation, suspension, or revocation of their nursing license. Investigations and discipline actions are reportable among states participating in the Nurse Licensure Compact (that allows nurses to practice across state lines) or when a nurse applies for licensure in a different state. The scope and standards of practice set forth in the Nurse Practice Act can also be used as evidence if a nurse is sued for malpractice.

Find your state's Nurse Practice Act on the National Council of State Board of Nursing (NCSBN) website.

Agency Policies, Procedures, and Protocols

In addition to practicing according to the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are employed, nurses must also practice according to agency policies, procedures, and protocols.

A policy is an expected course of action set by an agency. For example, hospitals set a policy requiring a thorough skin assessment to be completed when a patient is admitted and then reassessed and documented daily.

Agencies also establish their own set of procedures. A procedure is the method or defined steps for completing a task. For example, each agency has specific procedural steps for inserting a urinary catheter.

A protocol is a detailed, written plan for performing a regimen of therapy. For example, agencies typically establish a hypoglycemia protocol that nurses can independently and quickly implement when a patient’s blood sugar falls below a specific number without first calling a provider. A hypoglycemia protocol typically includes actions such as providing orange juice and rechecking the blood sugar and then reporting the incident to the provider.

Agency-specific policies, procedures, and protocols supersede the information taught in nursing school, and nurses can be held legally liable if they don’t follow them. It is vital for nurses to review and follow current agency-specific procedures, policies, and protocols while also practicing according to that state's nursing scope of practice. Malpractice cases have occurred when a nurse was asked by their employer to do something outside their legal scope of practice, impacting their nursing license. It is up to you to protect your nursing license and follow the Nurse Practice Act when providing patient care. If you have a concern about an agency’s policy, procedure, or protocol, follow the agency’s chain of command to report your concern.

Federal Regulations

Nursing practice is impacted by regulations enacted by federal agencies. Two examples of federal agencies setting standards of care are The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The Joint Commission accredits and certifies over 20,000 health care organizations in the United States. The Joint Commission’s standards help health care organizations measure, assess, and improve performance on functions that are essential to providing safe, high-quality care. The standards are updated regularly to reflect the rapid advances in health care and address topics such as patient rights and education, infection control, medication management, and prevention of medical errors. The annual National Patient Safety Goals are also set by The Joint Commission after reviewing emerging patient safety issues.[4]

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is an example of another federal agency that establishes regulations affecting nursing care. CMS is a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that administers the Medicare program and works in partnership with state governments to administer Medicaid. The CMS establishes and enforces regulations to protect patient safety in hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding. For example, one CMS regulation often referred to as “checking the rights of medication administration” requires nurses to confirm specific information several times before medication is administered to a patient.[5]

Standards of Practice

The ANA defines Standards of Professional Nursing Practice as “authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.”[6] These standards are classified into two categories: Standards of Practice and Standards of Professional Performance.

The ANA’s Standards of Practice describe a competent level of nursing practice as demonstrated by the critical thinking model known as the nursing process. The nursing process includes the components of assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation and forms the foundation of the nurse’s decision-making, practice, and provision of care.[7]

The ANA’s Standards of Professional Performance “describe a competent level of behavior in the professional role, including activities related to ethics, advocacy, respectful and equitable practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, scholarly inquiry, quality of practice, professional practice evaluation, resource stewardship, and environmental health. All registered nurses are expected to engage in professional role activities, including leadership, reflective of their education, position, and role.”[8] This book discusses content related to these professional practice standards. Each professional practice standard is defined in the following sections with information provided to related content in this book and the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e textbook.[9]

Ethics

The ANA’s Ethics standard states, “The registered nurse integrates ethics in all aspects of practice.”[10]

Advocacy

The ANA’s Advocacy standard states, “The registered nurse demonstrates advocacy in all roles and settings.”[11]

Respectful and Equitable Practice

The ANA’s Respectful and Equitable Practice standard states, “The registered nurse practices with cultural humility and inclusiveness.”

Communication

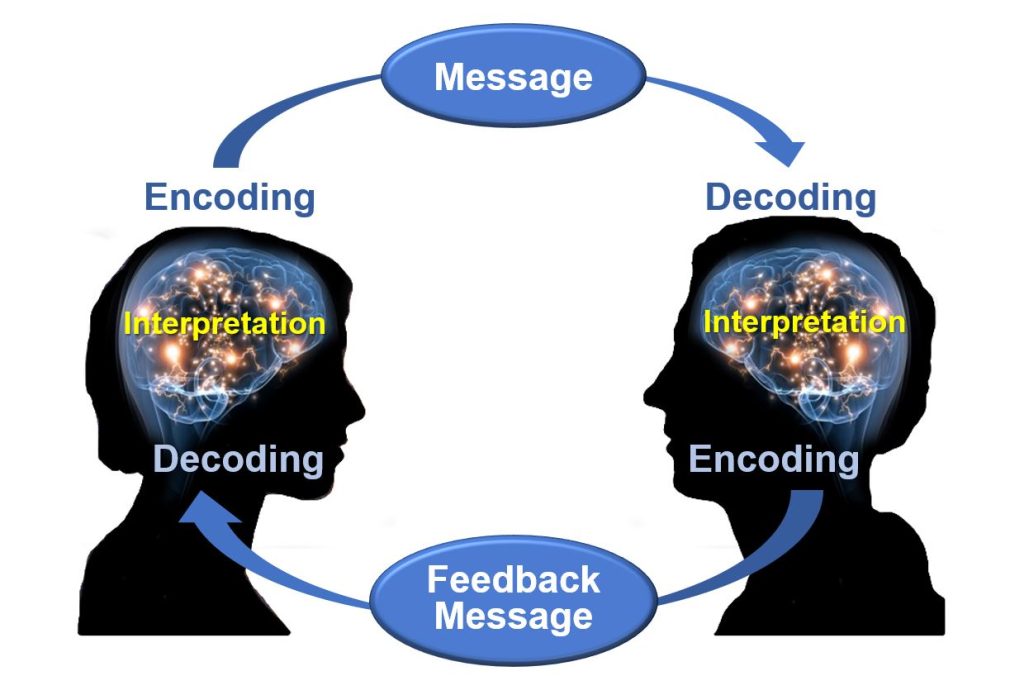

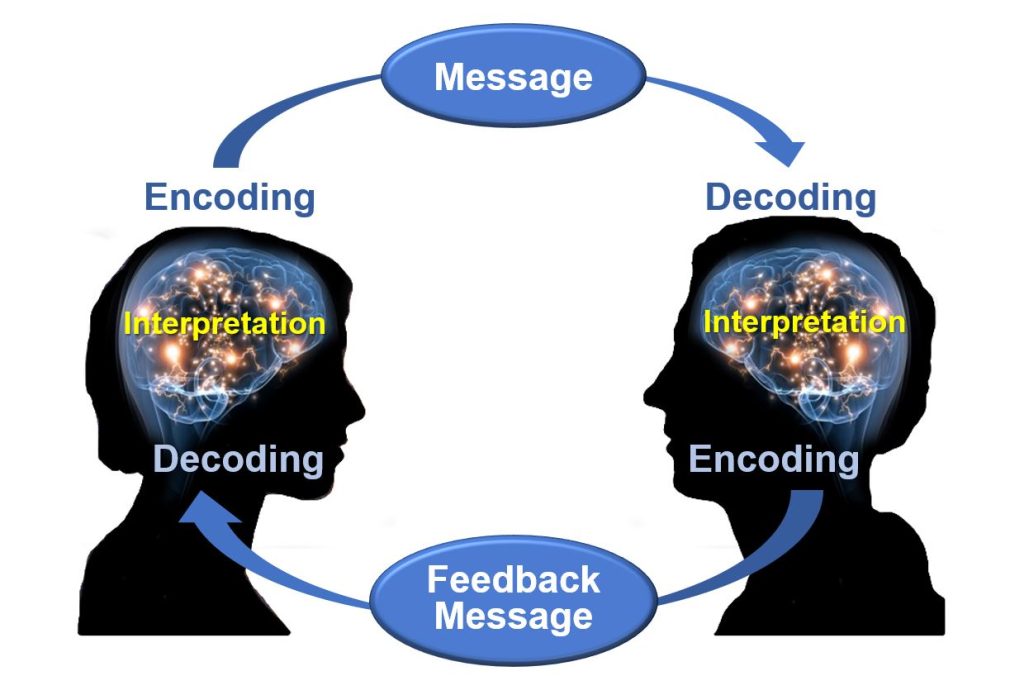

The ANA’s Communication standard states, “The registered nurse communicates effectively in all areas of professional practice.”[12]

Collaboration

The ANA’s Collaboration standard states, “The registered nurse collaborates with the health care consumer and other key stakeholders.”[13]

Leadership

The ANA’s Leadership standard states, “The registered nurse leads within the profession and practice setting.”[14]

Education

The ANA’s Education standard states, “The registered nurse seeks knowledge and competence that reflects current nursing practice and promotes futuristic thinking.”[15]

Scholarly Inquiry

The ANA’s Scholarly Inquiry standard states, “The registered nurse integrates scholarship, evidence, and research findings into practice.”[16]

Quality of Practice

The ANA’s Quality of Practice standard states, “The nurse contributes to quality nursing practice.”[17]

Professional Practice Evaluation

The ANA’s Professional Practice Evaluation standard states, “The registered nurse evaluates one’s own and others’ nursing practice.”[18]

Resource Stewardship

The ANA’s Resource Stewardship standard states, “The registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan, provide, and sustain evidence-based nursing services that are safe, effective, financially responsible, and used judiciously.”[19]

Environmental Health

The ANA’s Environmental Health standard states, “The registered nurse practices in a manner that advances environmental safety and health.”[20]

This textbook discusses professional and management concepts related to the role of a registered nurse (RN) as defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA). The ANA publishes two resources that set standards and guide professional nursing practice in the United States: The Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements and Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. The Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements establishes an ethical framework for nursing practice across all roles, levels, and settings and is discussed in greater detail in the “Ethical Practice” chapter of this book. The Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice resource defines the “who, what, where, when, why, and how of nursing” and sets the standards for practice that all registered nurses are expected to perform competently.[21]

The ANA defines the “who” of nursing practice as the nurses who have been educated, titled, and maintain active licensure to practice nursing. The “what” of nursing is the recently revised ANA definition of nursing: “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.”[22] Simply put, nurses treat human responses to health problems and life processes and advocate for the care of others.

Nursing practice occurs “when'' there is a need for nursing knowledge, wisdom, caring, leadership, practice, or education, anytime, anywhere. Nursing practice occurs in any environment “where'' there is a health care consumer in need of care, information, or advocacy. The “why” of nursing practice is described as nursing’s response to the changing needs of society to achieve positive health care consumer outcomes in keeping with nursing’s social contract and obligation to society. The “how” of nursing practice is defined as the ways, means, methods, and manners that nurses use to practice professionally.[23] The “how” of nursing, also referred to as a nurse’s “scope and standards of practice,” is further defined by each state’s Nurse Practice Act; agency policies, procedures, and protocols; and federal regulations and ANA’s Standards of Practice.

State Boards of Nursing and Nurse Practice Acts

RNs must legally follow regulations set by the Nurse Practice Act by the state in which they are caring for patients with their nursing license. The Board of Nursing is the state-specific licensing and regulatory body that sets standards for safe nursing care and issues nursing licenses to qualified candidates based on the Nurse Practice Act. The Nurse Practice Act is enacted by that state’s legislature and defines the scope of nursing practice and establishes regulations for nursing practice within that state. If nurses do not follow the standards and scope of practice set forth by the Nurse Practice Act, they may be disciplined by the Board of Nursing in the form of reprimand, probation, suspension, or revocation of their nursing license. Investigations and discipline actions are reportable among states participating in the Nurse Licensure Compact (that allows nurses to practice across state lines) or when a nurse applies for licensure in a different state. The scope and standards of practice set forth in the Nurse Practice Act can also be used as evidence if a nurse is sued for malpractice.

Find your state's Nurse Practice Act on the National Council of State Board of Nursing (NCSBN) website.

Read more about malpractice and protecting your nursing license in the “Legal Implications” chapter of this book.

Read Wisconsin’s Nurse Practice Act, Standards of Practice for Registered Nurses and Licensed Practical Nurses (Chapter N6) PDF, and Rules of Conduct (Chapter N7) PDF.

Agency Policies, Procedures, and Protocols

In addition to practicing according to the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are employed, nurses must also practice according to agency policies, procedures, and protocols.

A policy is an expected course of action set by an agency. For example, hospitals set a policy requiring a thorough skin assessment to be completed when a patient is admitted and then reassessed and documented daily.

Agencies also establish their own set of procedures. A procedure is the method or defined steps for completing a task. For example, each agency has specific procedural steps for inserting a urinary catheter.

A protocol is a detailed, written plan for performing a regimen of therapy. For example, agencies typically establish a hypoglycemia protocol that nurses can independently and quickly implement when a patient’s blood sugar falls below a specific number without first calling a provider. A hypoglycemia protocol typically includes actions such as providing orange juice and rechecking the blood sugar and then reporting the incident to the provider.

Agency-specific policies, procedures, and protocols supersede the information taught in nursing school, and nurses can be held legally liable if they don’t follow them. It is vital for nurses to review and follow current agency-specific procedures, policies, and protocols while also practicing according to that state's nursing scope of practice. Malpractice cases have occurred when a nurse was asked by their employer to do something outside their legal scope of practice, impacting their nursing license. It is up to you to protect your nursing license and follow the Nurse Practice Act when providing patient care. If you have a concern about an agency’s policy, procedure, or protocol, follow the agency’s chain of command to report your concern.

Federal Regulations

Nursing practice is impacted by regulations enacted by federal agencies. Two examples of federal agencies setting standards of care are The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The Joint Commission accredits and certifies over 20,000 health care organizations in the United States. The Joint Commission’s standards help health care organizations measure, assess, and improve performance on functions that are essential to providing safe, high-quality care. The standards are updated regularly to reflect the rapid advances in health care and address topics such as patient rights and education, infection control, medication management, and prevention of medical errors. The annual National Patient Safety Goals are also set by The Joint Commission after reviewing emerging patient safety issues.[24]

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is an example of another federal agency that establishes regulations affecting nursing care. CMS is a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that administers the Medicare program and works in partnership with state governments to administer Medicaid. The CMS establishes and enforces regulations to protect patient safety in hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding. For example, one CMS regulation often referred to as “checking the rights of medication administration” requires nurses to confirm specific information several times before medication is administered to a patient.[25]

Standards of Practice

The ANA defines Standards of Professional Nursing Practice as “authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.”[26] These standards are classified into two categories: Standards of Practice and Standards of Professional Performance.

The ANA’s Standards of Practice describe a competent level of nursing practice as demonstrated by the critical thinking model known as the nursing process. The nursing process includes the components of assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation and forms the foundation of the nurse’s decision-making, practice, and provision of care.[27]

Read more information about the nursing process in the “Nursing Process” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[28]

The ANA’s Standards of Professional Performance “describe a competent level of behavior in the professional role, including activities related to ethics, advocacy, respectful and equitable practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, scholarly inquiry, quality of practice, professional practice evaluation, resource stewardship, and environmental health. All registered nurses are expected to engage in professional role activities, including leadership, reflective of their education, position, and role.”[29] This book discusses content related to these professional practice standards. Each professional practice standard is defined in the following sections with information provided to related content in this book and the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e textbook.[30]

Ethics

The ANA’s Ethics standard states, “The registered nurse integrates ethics in all aspects of practice.”[31]

Read about ethical nursing practice in the “Ethical Practice” chapter of this book.

Advocacy

The ANA’s Advocacy standard states, “The registered nurse demonstrates advocacy in all roles and settings.”[32]

Read about nurse advocacy in the “Advocacy” chapter of this book.

Respectful and Equitable Practice

The ANA’s Respectful and Equitable Practice standard states, “The registered nurse practices with cultural humility and inclusiveness.”

Read about cultural humility and culturally responsive care in the “Diverse Patients” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[33]

Communication

The ANA’s Communication standard states, “The registered nurse communicates effectively in all areas of professional practice.”[34]

Read about communicating with clients and team members in the “Communication” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[35]

Read about interprofessional communication strategies that promote patient safety in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Collaboration

The ANA’s Collaboration standard states, “The registered nurse collaborates with the health care consumer and other key stakeholders.”[36]

Read about strategies to enhance the performance of the interprofessional team and manage conflict in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Leadership

The ANA’s Leadership standard states, “The registered nurse leads within the profession and practice setting.”[37]

Read about leadership, management, and implementing change in the “Leadership and Management” chapter of this book.

Read about assigning, delegating, and supervising patient care in the “Delegation and Supervision” chapter of this book.

Read about tools for prioritizing patient care and managing resources for the nursing team in the “Prioritization” chapter of this book.

Education

The ANA’s Education standard states, “The registered nurse seeks knowledge and competence that reflects current nursing practice and promotes futuristic thinking.”[38]

Read about professional development and specialty certification in the “Preparation for the RN Role” chapter of this book.

Scholarly Inquiry

The ANA’s Scholarly Inquiry standard states, “The registered nurse integrates scholarship, evidence, and research findings into practice.”[39]

Read about integrating evidence-based practice into one’s nursing practice in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter of this book.

Quality of Practice

The ANA’s Quality of Practice standard states, “The nurse contributes to quality nursing practice.”[40]

Read about improving quality patient care and participating in quality improvement initiatives in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter of this book.

Professional Practice Evaluation

The ANA’s Professional Practice Evaluation standard states, “The registered nurse evaluates one’s own and others’ nursing practice.”[41]

Read about nursing practice within the legal framework of health care, negligence, malpractice, and protecting your nursing license in the “Legal Implications” chapter of this book.

Read about reviewing the interprofessional team’s performance, providing constructive feedback, and advocating for patient safety with assertive statements in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Resource Stewardship

The ANA’s Resource Stewardship standard states, “The registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan, provide, and sustain evidence-based nursing services that are safe, effective, financially responsible, and used judiciously.”[42]

Read more about health care funding, reimbursement models, budgets and staffing, and resource stewardship in the “Health Care Economics” chapter of this book.

Environmental Health

The ANA’s Environmental Health standard states, “The registered nurse practices in a manner that advances environmental safety and health.”[43]

Read about promoting workplace safety for nurses in the “Safety” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[44]

Read about fostering a professional environment that does not tolerate abusive behaviors in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Read about addressing the impacts of social determinants of health in the “Advocacy” chapter of this book.

“So much to do, so little time.” This is a common mantra of today’s practicing nurse in various health care settings. Whether practicing in acute inpatient care, long-term care, clinics, home care, or other agencies, nurses may feel there is "not enough of them to go around.”

The health care system faces a significant challenge in balancing the ever-expanding task of meeting patient care needs with scarce nursing resources that has even worsened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many health care organizations have seen exacerbation in nurse turnover post-pandemic as nurses struggle with increasing stress, burnout, and feeling of uncertainty within the profession.[45] A recent nursing survey done by the American Nurses Foundation found that 60% of nurses reported extremely stressful, violent, and traumatic events as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[46] Additionally, a staggering 89% of nurses reported that their organizations experience significant staffing shortages.[47]

With a limited supply of registered nurses, nurse managers are often challenged to implement creative staffing practices such as sending staff to units where they do not normally work (i.e., floating), implementing mandatory staffing and/or overtime, utilizing travel nurses, or using other practices to meet patient care demands.[48] Staffing strategies can result in nurses experiencing increased patient assignments and workloads, extended shifts, or temporary suspension of paid time off. Nurses may receive a barrage of calls and text messages offering “extra shifts” and bonus pay, and although the extra pay may be welcomed, they often eventually feel burnt out trying to meet the ever-expanding demands of the patient-care environment.

A novice nurse who is still learning how to navigate the complex health care environment and provide optimal patient care may feel overwhelmed by these conditions. Novice nurses frequently report increased levels of stress and disillusionment as they transition to the reality of the nursing role.[49] How can we address this professional dilemma and enhance the novice nurse's successful role transition to practice? The novice nurse must enter the profession with purposeful tools and strategies to help prioritize tasks and manage time so they can confidently address patient care needs, balance role demands, and manage day-to-day nursing activities.

Let’s take a closer look at the foundational concepts related to prioritization and time management in the nursing profession.

Assessment of reflexes is not typically performed by registered nurses as part of a routine nursing neurological assessment of adult patients, but it is used in nursing specialty units and in advanced practice. Spinal cord injuries, neuromuscular diseases, or diseases of the lower motor neuron tract can cause weak or absent reflexes. To perform deep reflex tendon testing, place the patient in a seated position. Use a reflex hammer in a quick striking motion by the wrist on various tendons to produce an involuntary response. Before classifying a reflex as absent or weak, the test should be repeated after the patient is encouraged to relax because voluntary tensing of the muscles can prevent an involuntary reflexive action.

Reflexes are graded from 0 to 4+, with "2+" considered normal:

- 0: Absent

- 1+: Hypoactive

- 2+: Normal

- 3+: Hyperactive without clonus

- 4+: Hyperactive with clonus (involuntary muscle contraction)

To observe assessment of deep tendon reflexes, view the following video.

View Stanford Medicine's Assessment of Deep Tendon Reflexes video on YouTube.[50]

Brachioradialis Reflex

The brachioradialis reflex is used to assess the cervical spine nerves C5 and C6. Ask the patient to support their arm on their thigh or on your hand. Identify the insertion of the brachioradialis tendon on the radius and briskly tap it with the reflex hammer. The reflex consists of flexion and supination of the forearm. See Figure 6.37[51] for an image of obtaining the brachioradialis reflex.

Triceps Reflex

The triceps reflex assesses cervical spine nerves C6 and C7. Support the patient’s arm underneath their bicep to maintain a position midway between flexion and extension. Ask the patient to relax their arm and allow it to fully be supported by your hand. Identify the triceps tendon posteriorly just above its insertion on the olecranon. Tap briskly on the tendon with the reflex hammer. Note extension of the forearm. See Figure 6.38[52] for an image of the triceps reflex exam.

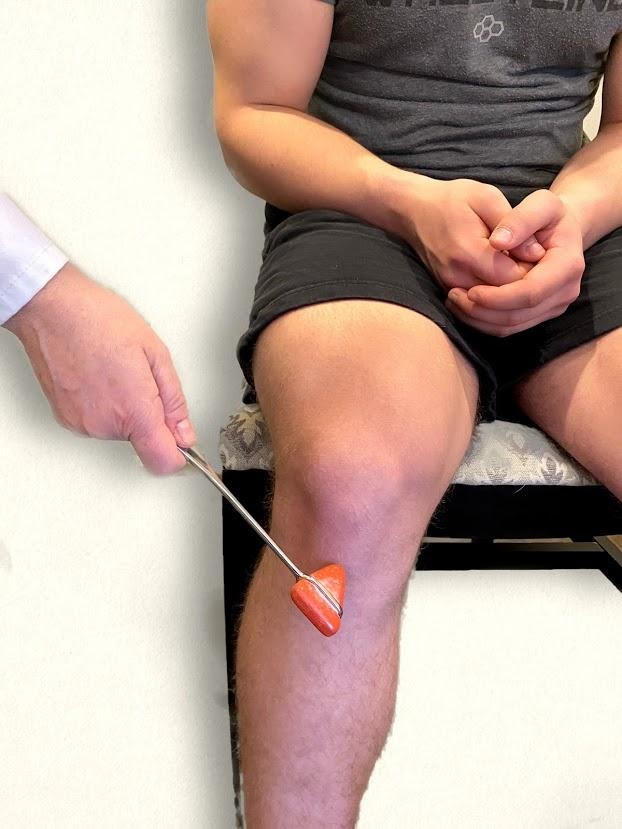

Patella (Knee Jerk) Reflex

The patellar reflex, commonly referred to as the knee jerk test, assesses lumbar spine nerves L2, L3, and L4. Ask the patient to relax the leg and allow it to swing freely at the knee. Tap the patella tendon briskly, looking for extension of the lower leg. See Figure 6.39[53] for an image of assessing a patellar reflex.

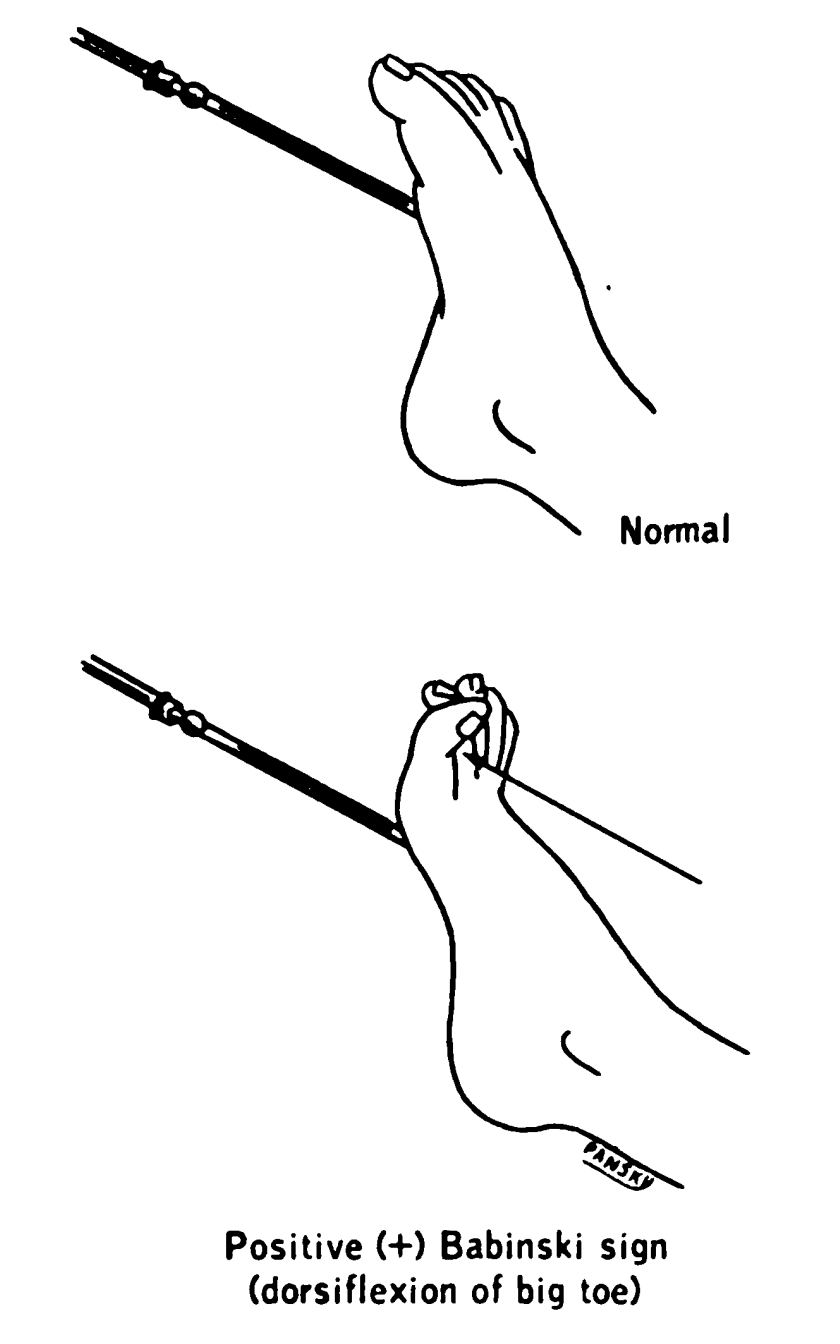

Plantar Reflex

The plantar reflex, or "Babinski reflex" assesses lumbar spine L5 and sacral spine S1. Ask the patient to extend their lower leg, and then stabilize their foot in the air with your hand. Slide the object along the lateral surface of the sole of the foot toward the toes. Many patients are ticklish and withdraw their foot, so it is sufficient to elicit the reflex by using your thumb to stroke lightly from the sole of the foot toward the toes. If there is no response, use a blunt object such as a key or pen. The expected reflex is flexion (i.e., bending) of the great toe. An abnormal response is toe extension (i.e., straightening), also known as the Babinski reflex. In a child younger than 2 years old, the big toe should bend up and backward toward the top of your foot while the other four toes fan out. This response is normal and doesn’t indicate any problems or abnormalities. In a child older than 2 years old or in a mature adult, the Babinski sign should be absent. All five toes should flex, or curl downward, as if they’re trying to grab something. If this test is conducted on a child older than 2 or an adult and the toes respond like those of a child under two years old, this can indicate an underlying neurological issue. See Figures 6.40 - 6.43[54],[55],[56],[57] for images of assessing the plantar reflex.

Newborn Reflexes

Newborn reflexes originate in the central nervous system and are exhibited by infants at birth but disappear as part of child development. Neurological disease or delayed development is indicated if these reflexes are not present at birth, do not spontaneously resolve, or reappear in adulthood. Common newborn reflexes include sucking, rooting, palmar grasp, plantar grasp, Babinski, Moro, and tonic neck reflexes.

Sucking Reflex

The sucking reflex is common to all mammals and is present at birth. It is linked with the rooting reflex and breastfeeding. It causes the child to instinctively suck anything that touches the roof of their mouth and simulates the way a child naturally eats. See Figure 6.44[60] for an image of the newborn sucking reflex.

Rooting Reflex

The rooting reflex assists in the act of breastfeeding. A newborn infant will turn its head toward anything that strokes its cheek or mouth, searching for the object by moving its head in steadily decreasing arcs until the object is found. See Figure 6.45[61] for an image of a newborn exhibiting the rooting reflex.

Palmar and Plantar Grasps

When an object is placed in an infant's hand and the palm of the child is stroked, the fingers will close reflexively, referred to as the palmar grasp reflex. A similar reflexive action occurs if an object is placed on the plantar surface of an infant’s foot, referred to as the plantar grasp reflex. See Figure 6.46[62] for an image of the palmar grasp reflex.

Moro Reflex

The Moro reflex is present at birth and is often stimulated by a loud noise. The Moro reflex occurs when the legs and head of the infant extend while the arms jerk up and out with the palms up. See Figure 6.47[63] for an image of an infant exhibiting the Moro reflex.

Tonic Neck Reflex

The asymmetrical tonic neck reflex, also known as the “fencing posture,” occurs when the child's head is turned to the side. The arm on the same side as the head is turned will straighten and the opposite arm will bend. See Figure 6.48[64] for an image of the tonic neck reflex.

Walking-Stepping Reflex

Although infants cannot support their own weight, when the soles of their feet touch a surface, it appears as if they are attempting to walk by placing one foot in front of the other foot.

Prioritization

As new nurses begin their career, they look forward to caring for others, promoting health, and saving lives. However, when entering the health care environment, they often discover there are numerous and competing demands for their time and attention. Patient care is often interrupted by call lights, rounding physicians, and phone calls from the laboratory department or other interprofessional team members. Even individuals who are strategic and energized in their planning can feel frustrated as their task lists and planned patient-care activities build into a long collection of “to dos.”

Without utilization of appropriate prioritization strategies, nurses can experience time scarcity, a feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against them. Functioning under the burden of time scarcity can cause feelings of frustration, inadequacy, and eventually burnout. Time scarcity can also impact patient safety, resulting in adverse events and increased mortality.[65] Additionally, missed or rushed nursing activities can negatively impact patient satisfaction scores that ultimately affect an institution's reimbursement levels.

It is vital for nurses to plan patient care and implement their task lists while ensuring that critical interventions are safely implemented first. Identifying priority patient problems and implementing priority interventions are skills that require ongoing cultivation as one gains experience in the practice environment.[66] To develop these skills, students must develop an understanding of organizing frameworks and prioritization processes for delineating care needs. These frameworks provide structure and guidance for meeting the multiple and ever-changing demands in the complex health care environment.

Let’s consider a clinical scenario in the following box to better understand the implications of prioritization and outcomes.

Scenario A

Imagine you are beginning your shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. You receive a handoff report on four medical-surgical patients from the night shift nurse:

- Patient A is a 34-year-old total knee replacement patient, post-op Day 1, who had an uneventful night. It is anticipated that she will be discharged today and needs patient education for self-care at home.

- Patient B is a 67-year-old male admitted with weakness, confusion, and a suspected urinary tract infection. He has been restless and attempting to get out of bed throughout the night. He has a bed alarm in place.

- Patient C is a 49-year-old male, post-op Day 1 for a total hip replacement. He has been frequently using his patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump and last rated his pain as a "6."

- Patient D is a 73-year-old male admitted for pneumonia. He has been hospitalized for three days and receiving intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His next dose is due in an hour. His oxygen requirements have decreased from 4 L/minute of oxygen by nasal cannula to 2 L/minute by nasal cannula.

Based on the handoff report you received, you ask the nursing assistant to check on Patient B while you do an initial assessment on Patient D. As you are assessing Patient D's oxygenation status, you receive a phone call from the laboratory department relating a critical lab value on Patient C, indicating his hemoglobin is low. The provider calls and orders a STAT blood transfusion for Patient C. Patient A rings the call light and states she and her husband have questions about her discharge and are ready to go home. The nursing assistant finds you and reports that Patient B got out of bed and experienced a fall during the handoff reports.

It is common for nurses to manage multiple and ever-changing tasks and activities like this scenario, illustrating the importance of self-organization and priority setting. This chapter will further discuss the tools nurses can use for prioritization.

Prioritization of care for multiple patients while also performing daily nursing tasks can feel overwhelming in today’s fast-paced health care system. Because of the rapid and ever-changing conditions of patients and the structure of one’s workday, nurses must use organizational frameworks to prioritize actions and interventions. These frameworks can help ease anxiety, enhance personal organization and confidence, and ensure patient safety.

Acuity

Acuity and intensity are foundational concepts for prioritizing nursing care and interventions. Acuity refers to the level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. For example, acuity may include characteristics such as unstable vital signs, oxygenation therapy, high-risk IV medications, multiple drainage devices, or uncontrolled pain. A "high-acuity" patient requires several nursing interventions and frequent nursing assessments.

Intensity addresses the time needed to complete nursing care and interventions such as providing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), performing wound care, or administering several medication passes. For example, a "high-intensity" patient generally requires frequent or long periods of psychosocial, educational, or hygiene care from nursing staff members. High-intensity patients may also have increased needs for safety monitoring, familial support, or other needs.[67]

Many health care organizations structure their staffing assignments based on acuity and intensity ratings to help provide equity in staff assignments. Acuity helps to ensure that nursing care is strategically divided among nursing staff. An equitable assignment of patients benefits both the nurse and patient by helping to ensure that patient care needs do not overwhelm individual staff and safe care is provided.

Organizations use a variety of systems when determining patient acuity with rating scales based on nursing care delivery, patient stability, and care needs. See an example of a patient acuity tool published in the American Nurse in Table 2.3.[68] In this example, ratings range from 1 to 4, with a rating of 1 indicating a relatively stable patient requiring minimal individualized nursing care and intervention. A rating of 2 reflects a patient with a moderate risk who may require more frequent intervention or assessment. A rating of 3 is attributed to a complex patient who requires frequent intervention and assessment. This patient might also be a new admission or someone who is confused and requires more direct observation. A rating of 4 reflects a high-risk patient. For example, this individual may be experiencing frequent changes in vital signs, may require complex interventions such as the administration of blood transfusions, or may be experiencing significant uncontrolled pain. An individual with a rating of 4 requires more direct nursing care and intervention than a patient with a rating of 1 or 2.[69]

Table 2.3. Example of a Patient Acuity Tool[70]

| 1: Stable Patient | 2: Moderate-Risk Patient | 3: Complex Patient | 4: High-Risk Patient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

|

|

| Cardiac |

|

|

|

|

| Medications |

|

|

|

|

| Drainage Devices |

|

|

|

|

| Pain Management |

|

|

|

|

| Admit/Transfer/Discharge |

|

|

|

|

| ADLs and Isolation |

|

|

|

|

| Patient Score | Most = 1 | Two or > = 2 | Any = 3 | Any = 4 |

Read more about using a patient acuity tool on a medical-surgical unit.

Rating scales may vary among institutions, but the principles of the rating system remain the same. Organizations include various patient care elements when constructing their staffing plans for each unit. Read more information about staffing models and acuity in the following box.

Staffing Models and Acuity

Organizations that base staffing on acuity systems attempt to evenly staff patient assignments according to their acuity ratings. This means that when comparing patient assignments across nurses on a unit, similar acuity team scores should be seen with the goal of achieving equitable and safe division of workload across the nursing team. For example, one nurse should not have a total acuity score of 6 for their patient assignments while another nurse has a score of 15. If this situation occurred, the variation in scoring reflects a discrepancy in workload balance and would likely be perceived by nursing peers as unfair. Using acuity-rating staffing models is helpful to reflect the individualized nursing care required by different patients.

Alternatively, nurse staffing models may be determined by staffing ratio. Ratio-based staffing models are more straightforward in nature, where each nurse is assigned care for a set number of patients during their shift. Ratio-based staffing models may be useful for administrators creating budget requests based on the number of staff required for patient care, but can lead to an inequitable division of work across the nursing team when patient acuity is not considered. Increasingly complex patients require more time and interventions than others, so a blend of both ratio and acuity-based staffing is helpful when determining staffing assignments.[71]

As a practicing nurse, you will be oriented to the elements of acuity ratings within your health care organization, but it is also important to understand how you can use these acuity ratings for your own prioritization and task delineation. Let’s consider the Scenario B in the following box to better understand how acuity ratings can be useful for prioritizing nursing care.

Scenario B

You report to work at 6 a.m. for your nursing shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. Prior to receiving the handoff report from your night shift nursing colleagues, you review the unit staffing grid and see that you have been assigned to four patients to start your day. The patients have the following acuity ratings:

Patient A: 45-year-old patient with paraplegia admitted for an infected sacral wound, with an acuity rating of 4.

Patient B: 87-year-old patient with pneumonia with a low-grade fever of 99.7 F and receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute via nasal cannula, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient C: 63-year-old patient who is postoperative Day 1 from a right total hip replacement and is receiving pain management via a PCA pump, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient D: 83-year-old patient admitted with a UTI who is finishing an IV antibiotic cycle and will be discharged home today, with an acuity rating of 1.

Based on the acuity rating system, your patient assignment load receives an overall acuity score of 9. Consider how you might use their acuity ratings to help you prioritize your care. Based on what is known about the patients related to their acuity rating, whom might you identify as your care priority? Although this can feel like a challenging question to answer because of the many unknown elements in the situation using acuity numbers alone, Patient A with an acuity rating of 4 would be identified as the care priority requiring assessment early in your shift.

Although acuity can a useful tool for determining care priorities, it is important to recognize the limitations of this tool and consider how other patient needs impact prioritization.

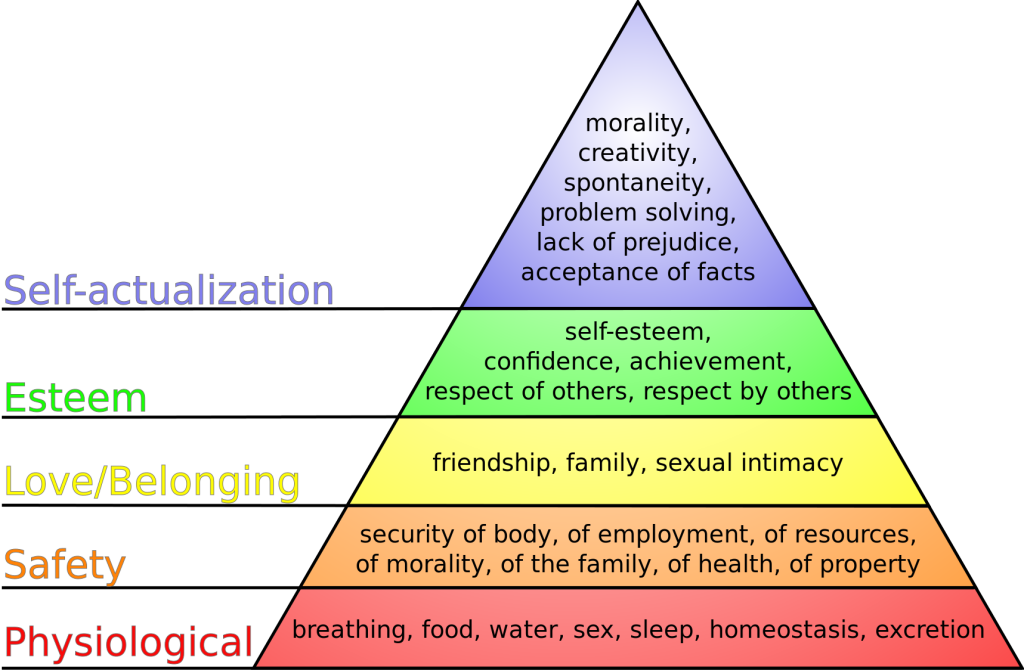

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

When thinking back to your first nursing or psychology course, you may recall a historical theory of human motivation based on various levels of human needs called Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs reflects foundational human needs with progressive steps moving towards higher levels of achievement. This hierarchy of needs is traditionally represented as a pyramid with the base of the pyramid serving as essential needs that must be addressed before one can progress to another area of need.[72] See Figure 2.1[73] for an illustration of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs places physiological needs as the foundational base of the pyramid.[74] Physiological needs include oxygen, food, water, sex, sleep, homeostasis, and excretion. The second level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects safety needs. Safety needs include elements that keep individuals safe from harm. Examples of safety needs in health care include fall precautions. The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects emotional needs such as love and a sense of belonging. These needs are often reflected in an individual’s relationships with family members and friends. The top two levels of Maslow’s hierarchy include esteem and self-actualization. An example of addressing these needs in a health care setting is helping an individual build self-confidence in performing blood glucose checks that leads to improved self-management of their diabetes.

So how does Maslow’s theory impact prioritization? To better understand the application of Maslow’s theory to prioritization, consider Scenario C in the following box.

Scenario C

You are an emergency response nurse working at a local shelter in a community that has suffered a devastating hurricane. Many individuals have relocated to the shelter for safety in the aftermath of the hurricane. Much of the community is still without electricity and clean water, and many homes have been destroyed. You approach a young woman who has a laceration on her scalp that is bleeding through her gauze dressing. The woman is weeping as she describes the loss of her home stating, “I have lost everything! I just don’t know what I am going to do now. It has been a day since I have had water or anything to drink. I don’t know where my sister is, and I can’t reach any of my family to find out if they are okay!”

Despite this relatively brief interaction, this woman has shared with you a variety of needs. She has demonstrated a need for food, water, shelter, homeostasis, and family. As the nurse caring for her, it might be challenging to think about where to begin her care. These thoughts could be racing through your mind:

Should I begin to make phone calls to try and find her family? Maybe then she would be able to calm down.

Should I get her on the list for the homeless shelter so she wouldn’t have to worry about where she will sleep tonight?

She hasn’t eaten in a while; I should probably find her something to eat.

All these needs are important and should be addressed at some point, but Maslow’s hierarchy provides guidance on what needs must be addressed first. Use the foundational level of Maslow’s pyramid of physiological needs as the top priority for care. The woman is bleeding heavily from a head wound and has had limited fluid intake. As the nurse caring for this patient, it is important to immediately intervene to stop the bleeding and restore fluid volume. Stabilizing the patient by addressing her physiological needs is required before undertaking additional measures such as contacting her family. Imagine if instead you made phone calls to find the patient’s family and didn't address the bleeding or dehydration - you might return to a severely hypovolemic patient who has deteriorated and may be near death. In this example, prioritizing emotional needs above physiological needs can lead to significant harm to the patient.

Although this is a relatively straightforward example, the principles behind the application of Maslow’s hierarchy are essential. Addressing physiological needs before progressing toward additional need categories concentrates efforts on the most vital elements to enhance patient well-being. Maslow’s hierarchy provides the nurse with a helpful framework for identifying and prioritizing critical patient care needs.

ABCs

Airway, breathing, and circulation, otherwise known by the mnemonic “ABCs,” are another foundational element to assist the nurse in prioritization. Like Maslow’s hierarchy, using the ABCs to guide decision-making concentrates on the most critical needs for preserving human life. If a patient does not have a patent airway, is unable to breathe, or has inadequate circulation, very little of what else we do matters. The patient’s ABCs are reflected in Maslow’s foundational level of physiological needs and direct critical nursing actions and timely interventions. Let’s consider Scenario D in the following box regarding prioritization using the ABCs and the physiological base of Maslow’s hierarchy.

Scenario D

You are a nurse on a busy cardiac floor charting your morning assessments on a computer at the nurses’ station. Down the hall from where you are charting, two of your assigned patients are resting comfortably in Room 504 and Room 506. Suddenly, both call lights ring from the rooms, and you answer them via the intercom at the nurses’ station.

Room 504 has an 87-year-old male who has been admitted with heart failure, weakness, and confusion. He has a bed alarm for safety and has been ringing his call bell for assistance appropriately throughout the shift. He requires assistance to get out of bed to use the bathroom. He received his morning medications, which included a diuretic about 30 minutes previously, and now reports significant urge to void and needs assistance to the bathroom.

Room 506 has a 47-year-old woman who was hospitalized with new onset atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. The patient underwent a cardioversion procedure yesterday that resulted in successful conversion of her heart back into normal sinus rhythm. She is reporting via the intercom that her "heart feels like it is doing that fluttering thing again” and she is having chest pain with breathlessness.

Based upon these two patient scenarios, it might be difficult to determine whom you should see first. Both patients are demonstrating needs in the foundational physiological level of Maslow’s hierarchy and require assistance. To prioritize between these patients' physiological needs, the nurse can apply the principles of the ABCs to determine intervention. The patient in Room 506 reports both breathing and circulation issues, warning indicators that action is needed immediately. Although the patient in Room 504 also has an urgent physiological elimination need, it does not overtake the critical one experienced by the patient in Room 506. The nurse should immediately assess the patient in Room 506 while also calling for assistance from a team member to assist the patient in Room 504.

CURE

Prioritizing what should be done and when it can be done can be a challenging task when several patients all have physiological needs. Recently, there has been professional acknowledgement of the cognitive challenge for novice nurses in differentiating physiological needs. To expand on the principles of prioritizing using the ABCs, the CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras.[75]

“Critical” patient needs require immediate action. Examples of critical needs align with the ABCs and Maslow’s physiological needs, such as symptoms of respiratory distress, chest pain, and airway compromise. No matter the complexity of their shift, nurses can be assured that addressing patients' critical needs is the correct prioritization of their time and energies.

After critical patient care needs have been addressed, nurses can then address “urgent” needs. Urgent needs are characterized as needs that cause patient discomfort or place the patient at a significant safety risk.[76]

The third part of the CURE hierarchy reflects “routine” patient needs. Routine patient needs can also be characterized as "typical daily nursing care" because the majority of a standard nursing shift is spent addressing routine patient needs. Examples of routine daily nursing care include actions such as administering medication and performing physical assessments.[77] Although a nurse’s typical shift in a hospital setting includes these routine patient needs, they do not supersede critical or urgent patient needs.

The final component of the CURE hierarchy is known as “extras.” Extras refer to activities performed in the care setting to facilitate patient comfort but are not essential.[78] Examples of extra activities include providing a massage for comfort or washing a patient’s hair. If a nurse has sufficient time to perform extra activities, they contribute to a patient’s feeling of satisfaction regarding their care, but these activities are not essential to achieve patient outcomes.

Let's apply the CURE mnemonic to patient care in the following box.