6.2 Basic Neurological Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

When completing a neurological assessment, it is important to understand the functions performed by different parts of the nervous system while analyzing findings. For example, damage to specific areas of the brain, such as that caused by a head injury or cerebrovascular accidents (i.e., strokes), can cause specific deficits in speech, facial movements, or use of the extremities. Damage to the spinal cord, such as that caused by a motor vehicle accident or diving accident, will cause specific motor and sensory deficits according to the level where the spinal cord was damaged.

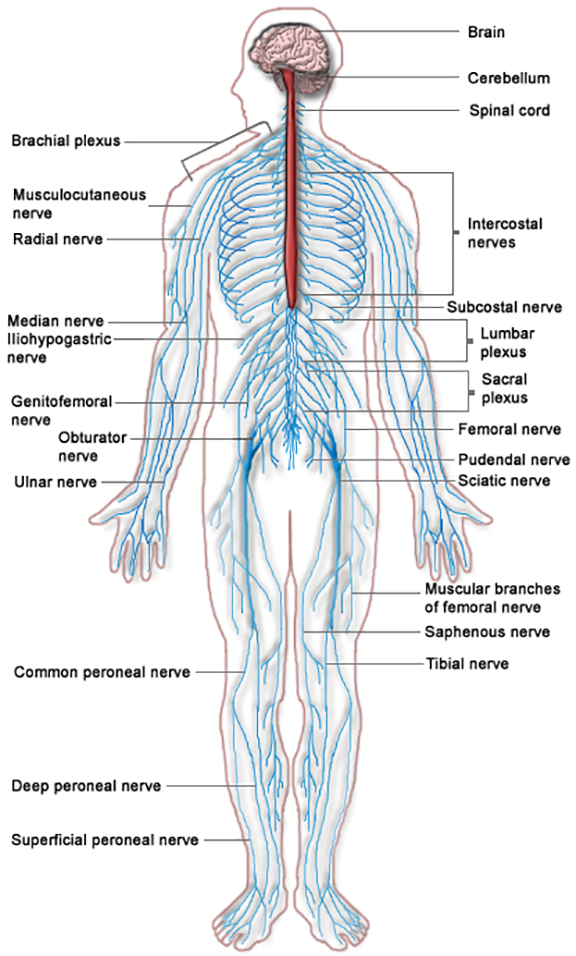

The nervous system is divided into two parts, the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. See Figure 6.1[1] for an image of the entire nervous system. The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and the spinal cord. The brain can be described as the interpretation center, and the spinal cord can be described as the transmission pathway. The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of the neurological system outside of the brain and spinal cord, including the cranial nerves that branch out from the brain and the spinal nerves that branch out from the spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system can be described as the communication network between the brain and the body parts. Both parts of the nervous system must work correctly for healthy body functioning.

Central Nervous System

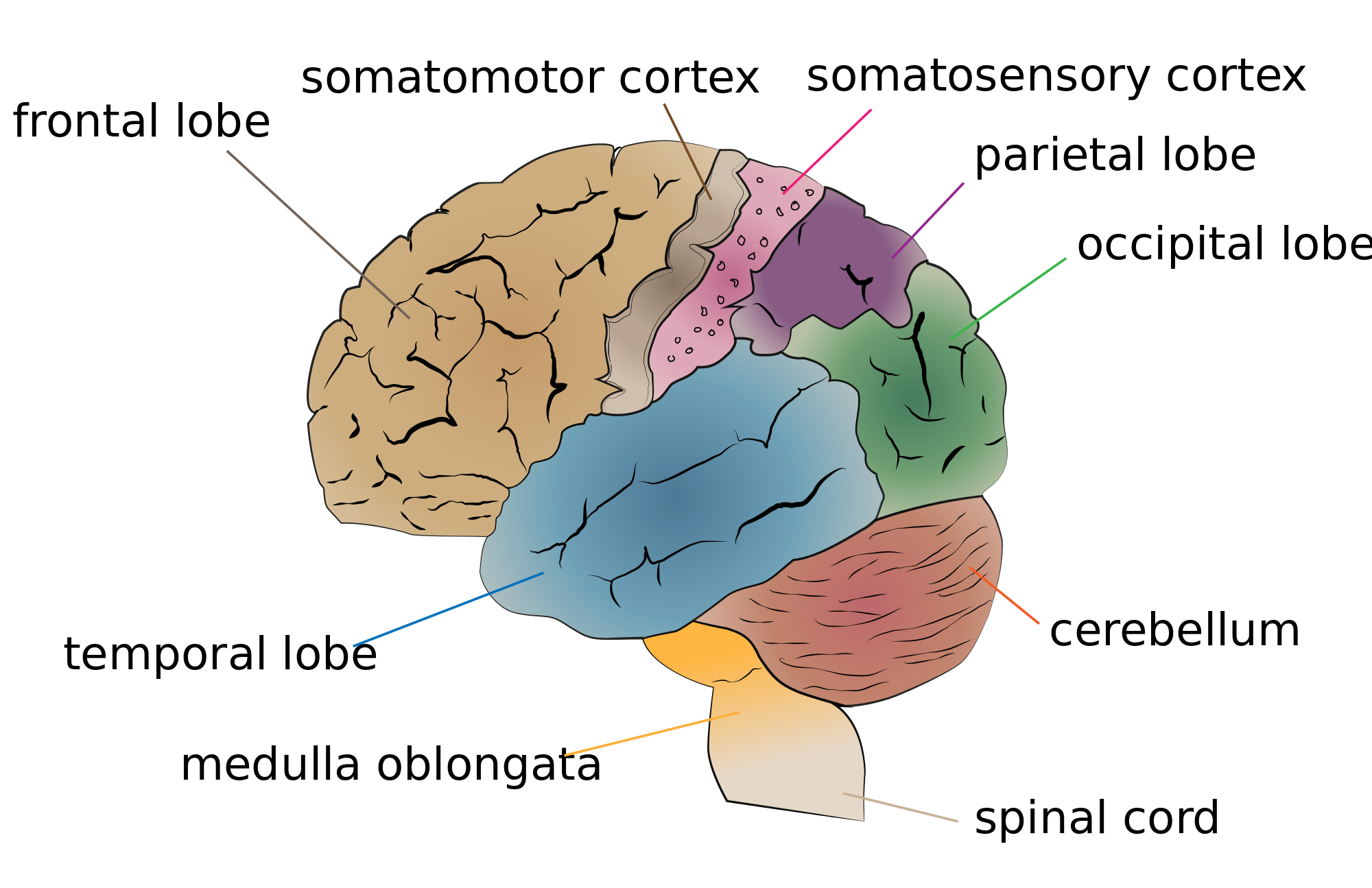

The major regions of the brain are the cerebrum and cerebral cortex, the diencephalon, the brain stem, and the cerebellum. See Figure 6.2[2] for an illustration of the cerebellum and the lobes of the cerebrum.

Cerebrum and Cerebral Cortex

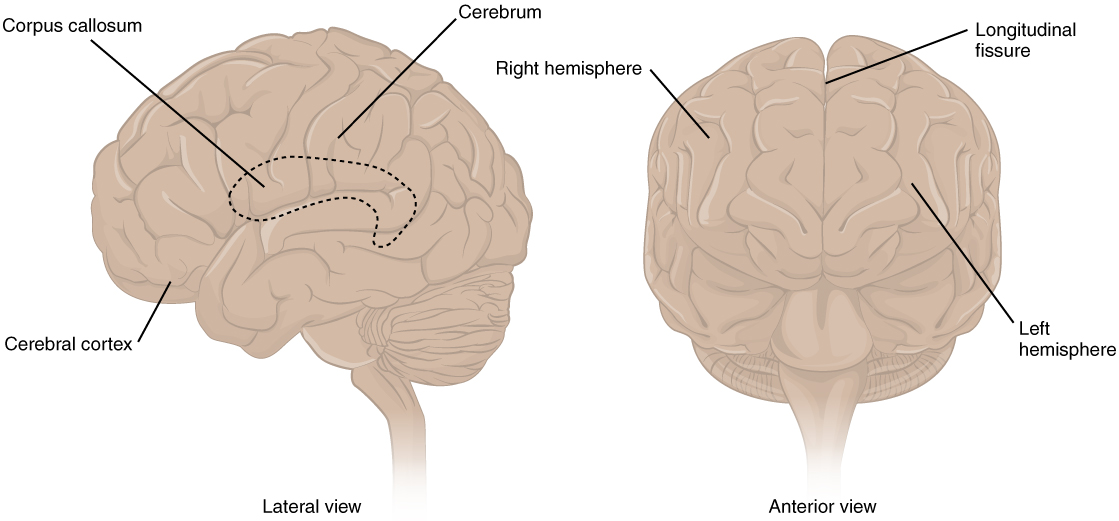

The largest portion of our brain is the cerebrum. The cerebrum is covered by a wrinkled outer layer of gray matter called the cerebral cortex. See Figure 6.3[3] for an image of the cerebral cortex. The cerebral cortex is responsible for the higher functions of the nervous system such as memory, emotion, and consciousness. The corpus callosum is the major pathway of communication between the right and left hemispheres of the cerebral cortex. The cerebral cortex is further divided into four lobes named the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes.[4] Each lobe has specific functions.

Frontal Lobe

The frontal lobe is associated with movement because it contains neurons that instruct cells in the spinal cord to move skeletal muscles. The anterior portion of the frontal lobe is called the prefrontal lobe, and it provides cognitive functions such as planning and problem-solving that are the basis of our personality, short-term memory, and consciousness. Broca’s area is also located in the frontal lobe and is responsible for the production of language and controlling movements responsible for speech.[5]

Parietal Lobe

The parietal lobe processes general sensations from the body. All of the tactile senses are processed in this area, including touch, pressure, tickle, pain, itch, and vibration, as well as general senses of the body, such as proprioception (the sense of body position) and kinesthesia (the sense of movement).[6]

Temporal Lobe

The temporal lobe processes auditory information and is involved with language comprehension and production. Wernicke’s area and Broca’s area are located in the temporal lobe. Wernicke’s area is involved in the comprehension of written and spoken language, and Broca’s area is involved in the production of language. Because regions of the temporal lobe are part of the limbic system, memory is also an important function associated with the temporal lobe.[7] The limbic system is involved with our behavioral and emotional responses needed for survival, such as feeding, reproduction, and the fight – or – flight responses.

Occipital Lobe

The occipital lobe primarily processes visual information.[8]

Diencephalon

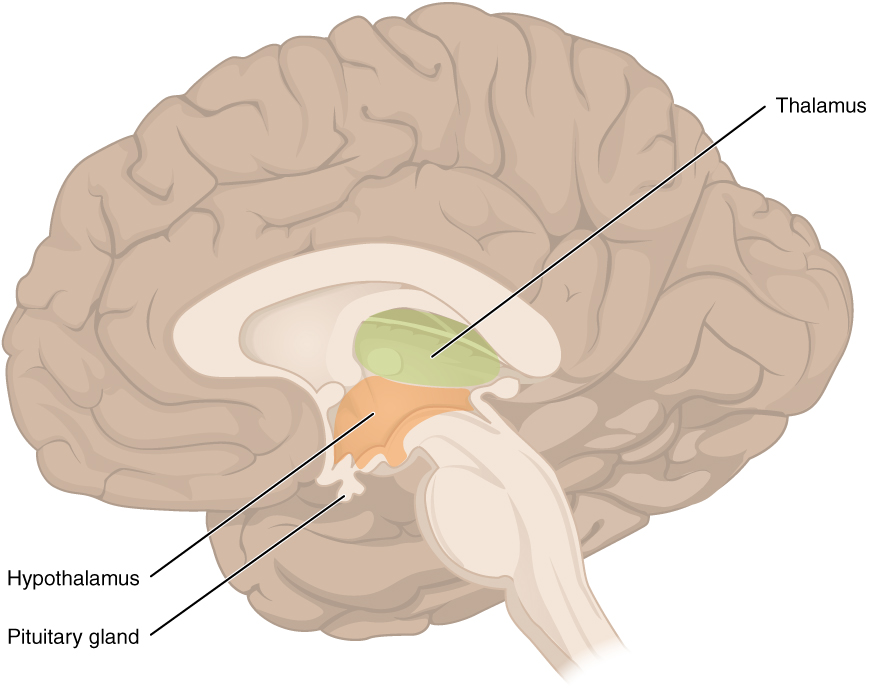

Information from the rest of the central and peripheral nervous system is sent to the cerebrum through the diencephalon, with the exception of the olfactory nerve that connects directly to the cerebrum.[9] See Figure 6.4[10] for an illustration of the diencephalon deep within the cerebrum. The diencephalon contains the hypothalamus and the thalamus.

The hypothalamus helps regulate homeostasis such as body temperature, thirst, hunger, and sleep. The hypothalamus is also the executive region in charge of the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system through its regulation of the anterior pituitary gland. Other parts of the hypothalamus are involved in memory and emotion as part of the limbic system.[11]

The thalamus relays sensory information and motor information in collaboration with the cerebellum. The thalamus does not just pass the information on, but it also processes and prioritizes that information. For example, the portion of the thalamus that receives visual information will influence what visual stimuli are considered important enough to receive further attention from the brain.[12]

Brain Stem

The brain stem is composed of the pons and the medulla. The pons and the medulla regulate several crucial autonomic functions in the body, including involuntary functions in the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, vasodilation, and reflexes like vomiting, coughing, sneezing, and swallowing. Cranial nerves also connect to the brain through the brain stem and provide sensory input and motor output.[13]

For more information about the functions of the autonomic nervous system, visit the “Autonomic Nervous System” chapter in the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is located in the posterior part of the brain behind the brain stem and is responsible for fine motor movements and coordination. For example, when the motor neurons in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex send a command down the spinal cord to initiate walking, a copy of that instruction is also sent to the cerebellum. Sensory feedback from the muscles and joints, proprioceptive information about the movements of walking, and sensations of balance are sent back to the cerebellum. If the person becomes unbalanced while walking because the ground is uneven, the cerebellum sends out a corrective command to compensate for the difference between the original cerebral cortex command and the sensory feedback.[14]

Spinal Cord

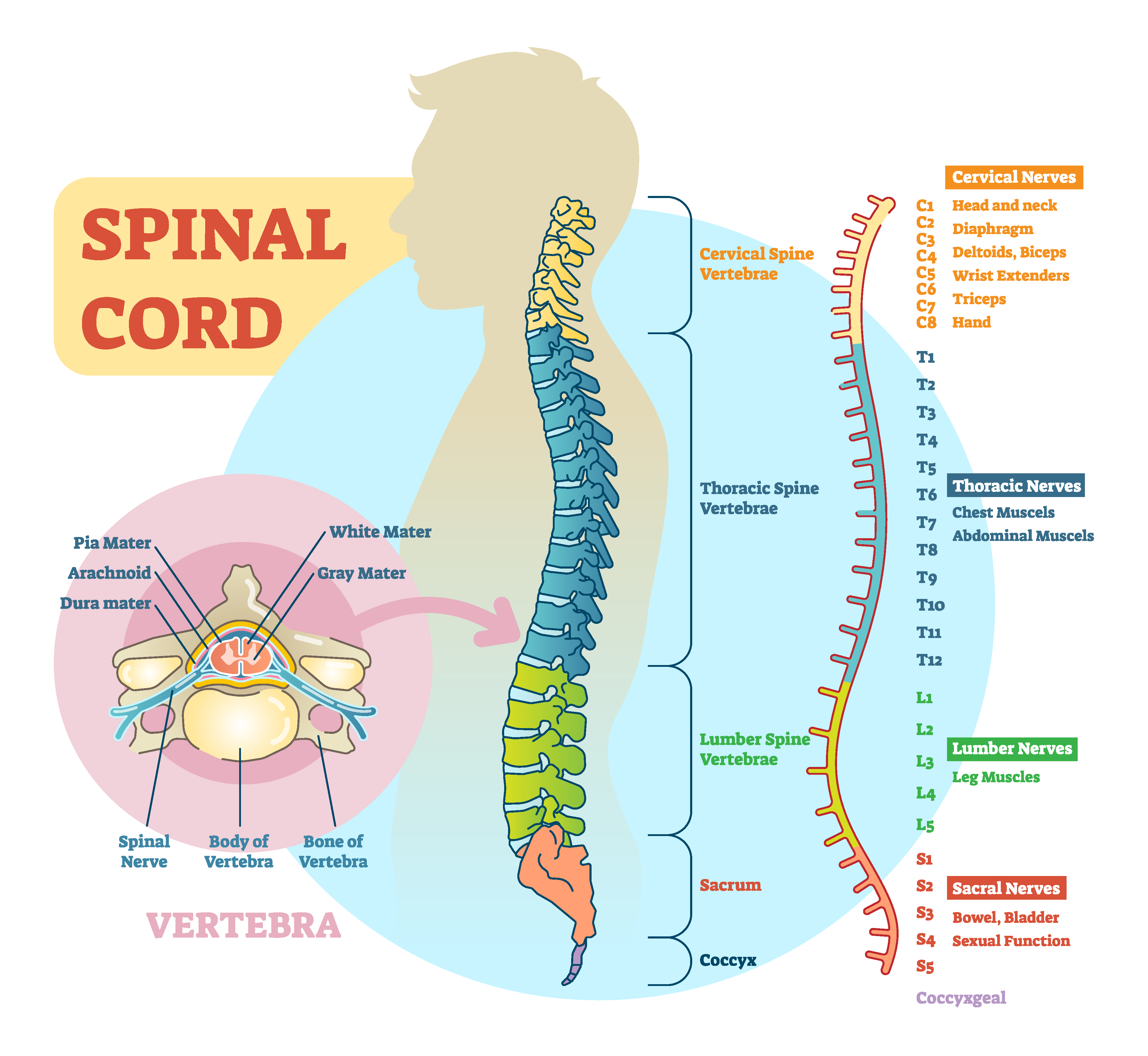

The spinal cord is a continuation of the brain stem that transmits sensory and motor impulses. The length of the spinal cord is divided into regions that correspond to the level at which spinal nerves pass through the vertebrae. Immediately adjacent to the brain stem is the cervical region, followed by the thoracic, the lumbar, and finally the sacral region.[15] The spinal nerves in each of these regions innervate specific parts of the body. See more information under the “Spinal Nerves” subsection.

Review the anatomy of the brain using following supplementary video.

Review for Anatomy of the Brain on YouTube[16]

Peripheral Nervous System

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of cranial nerves and spinal nerves that exist outside of the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. The main function of the PNS is to connect the limbs and organs to the central nervous system (CNS). Sensory information from the body enters the CNS through cranial and spinal nerves. Cranial nerves are connected directly to the brain, whereas spinal nerves are connected to the brain via the spinal cord.

Peripheral nerves are classified as sensory nerves, motor nerves, or a combination of both. Sensory nerves carry impulses from the body to the brain for processing. Motor nerves transmit motor signals from the brain to the muscles to cause movement.

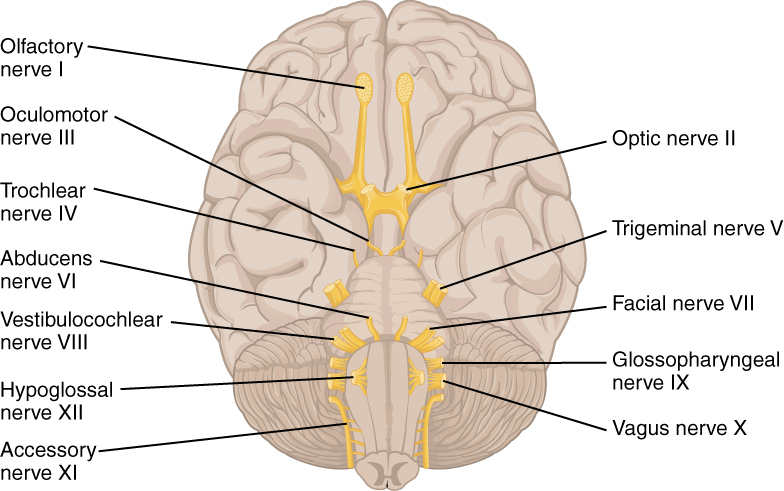

Cranial Nerves

Cranial nerves are directly connected from the periphery to the brain. They are primarily responsible for the sensory and motor functions of the head and neck. There are twelve cranial nerves that are designated by Roman numerals I through XII. See Figure 6.5[17] for an image of cranial nerves. Three cranial nerves are strictly sensory nerves; five are strictly motor nerves; and the remaining four are mixed nerves.[18] A traditional mnemonic for memorizing the names of the cranial nerves is “On Old Olympus Towering Tops A Finn And German Viewed Some Hops,” in which the initial letter of each word corresponds to the initial letter in the name of each nerve. A second popular mnemonic to assist with memorization is “Oh Once One Takes The Anatomy Final Very Good Vacations Are Heavenly”.

- The olfactory nerve is responsible for the sense of smell.

- The optic nerve is responsible for the sense of vision.

- The oculomotor nerve regulates eye movements by controlling four of the extraocular muscles, lifting the upper eyelid when the eyes point up and for constricting the pupils.

- The trochlear nerve and the abducens nerve are both responsible for eye movement but do so by controlling different extraocular muscles.

- The trigeminal nerve regulates skin sensations of the face and controls the muscles used for chewing.

- The facial nerve is responsible for the muscles involved in facial expressions, as well as part of the sense of taste and the production of saliva.

- The auditory/vestibulocochlear nerve manages hearing and balance.

- The glossopharyngeal nerve regulates the controlling muscles in the oral cavity and upper throat, as well as part of the sense of taste and the production of saliva.

- The vagus nerve is responsible for contributing to homeostatic control of the organs of the thoracic and upper abdominal cavities.

- The accessory nerve controls movements of the neck, along with cervical spinal nerves.

- The hypoglossal nerve manages the muscles of the lower throat and tongue.[19] Methods for assessing each of these nerves are described in the “Assessing Cranial Nerves” section.

Review of Cranial Nerves on YouTube[20]

Spinal Nerves

There are 31 spinal nerves that are named based on the level of the spinal cord where they emerge. See Figure 6.6[21] for an illustration of spinal nerves. There are eight pairs of cervical nerves designated C1 to C8, twelve thoracic nerves designated T1 to T12, five pairs of lumbar nerves designated L1 to L5, five pairs of sacral nerves designated S1 to S5, and one pair of coccygeal nerves. All spinal nerves are combined sensory and motor nerves. Spinal nerves extend outward from the vertebral column to innervate the periphery while also transmitting sensory information back to the CNS.[22]

Functions of Spinal Nerves

Each spinal nerve innervates a specific region of the body:

- C1 provides motor innervation to muscles at the base of the skull.[23]

- C2 and C3 provide both sensory and motor control to the back of the head and behind the ears.[24]

- The phrenic nerve arises from nerve roots C3, C4, and C5. This is a vital nerve because it innervates the diaphragm to enable breathing. If a patient’s spinal cord is transected above C3 from an injury, then spontaneous breathing is not possible.[25]

- C5 through C8 and T1 combine to form the brachial plexus, a tangled array of nerves that serve the upper limbs and upper back.[26]

- The lumbar plexus arises from L1-L5 and innervates the pelvic region and the anterior leg.[27]

- The sacral plexus comes from the lower lumbar nerves L4 and L5 and the sacral nerves S1 to S4. The most significant systemic nerve to come from this plexus is the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is associated with the painful medical condition sciatica, which is back and leg pain as a result of compression or irritation of the sciatic nerve.[28]

Functions of the Nervous System

The nervous system receives information about the environment around us (sensation) and generates responses to that information (motor responses). The process of integration combines sensory perceptions and higher cognitive functions such as memories, learning, and emotion while producing a response.

Sensation

Sensation is defined as receiving information about the environment. The major senses are taste, smell, touch, sight, and hearing. Additional sensory stimuli are also provided from inside the body, such as the stretch of an organ wall or the concentration of certain ions in the blood.[29]

Response

The nervous system produces a response based on the stimuli perceived by sensory nerves. For example, withdrawing a hand from a hot stove is an example of a response to a painfully hot stimulus. Responses can be classified by those that are voluntary (such as contraction of a skeletal muscle) and those that are involuntary (such as contraction of smooth muscle in the intestine). Voluntary responses are governed by the somatic nervous system, and involuntary responses are governed by the autonomic nervous system.[30]

Integration

Integration occurs when stimuli received by sensory nerves are communicated to the nervous system and the information is processed, leading to the generation of a conscious response. Consider this example of sensory integration. A batter in a baseball game does not automatically swing when they see the baseball thrown to them by the pitcher. First, the trajectory of the ball and its speed will need to be considered before creating the motor response of a swing. Then, integration will occur as the batter generates a conscious decision of whether to swing or not. Perhaps the count is three balls and one strike, and the batter decides to let this pitch go by in the hope of getting a walk to first base. Perhaps the batter is afraid to strike out and doesn’t swing, or maybe the batter learned the pitcher’s nonverbal cues the previous time at bat and is confident to take a swing at an anticipated fast ball. All of these considerations are included as part of the batter’s integration response and the higher-level functioning that occurs in the cerebral cortex.[31]

- “Nervous system diagram.png” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Access for free at https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nursing/Book%3A_Clinical_Procedures_for_Safer_Patient_Care_(Doyle_and_McCutcheon)/02%3A_Patient_Assessment/2.07%3A_Focused_Assessments ↵

- “Cerebrum lobes.svg” by Jkwchui is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “1305 CerebrumN.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/13-2-the-central-nervous-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1310 Diencephalon.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/13-2-the-central-nervous-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Forciea, B. (2015, May 12). Anatomy and physiology: Central nervous system: Brain anatomy v2.0 [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/DBRdInd2-Vg ↵

- “1320 The Cranial Nerves.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/13-4-the-peripheral-nervous-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Forciea, B. (2015, May 12). Anatomy and physiology: Nervous system: Cranial nerves (v2.0) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/JBEZh6CHogo ↵

- “1008694237-vector.png” by VectorMine on Shutterstock. All rights reserved. Imaged used with purchased permission. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by Boundless.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by Boundless.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by Boundless.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by Boundless.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

Now that we have discussed various concepts related to oxygenation and hypoxia, we will explain how a nurse uses the nursing process to care for clients with alterations in oxygenation.

Assessment

When assessing a client’s oxygenation status, there are several subjective and objective assessments to include.

Subjective Assessment

The primary symptom to assess when a client is experiencing decreased oxygenation is their level of dyspnea, the medical term for the subjective feeling of shortness of breath or difficulty breathing. Clients can be asked to rate their dyspnea on a scale of 0-10, similar to using a pain rating scale.[1] The feeling of dyspnea can be very disabling for clients. There are many interventions that a nurse can implement to help improve the feeling of dyspnea and, thus, improve a client’s overall quality of life.

It is also important to ask clients if they are experiencing a cough. If a cough is present, determine if sputum is present, and if so, the color and amount of sputum. Sputum is mucus and other secretions that are coughed up and expelled from the mouth. The body always produces mucus to keep the delicate tissues of the respiratory tract moist so small particles of foreign matter can be trapped and forced out, but when there is an infection in the lungs, an excess of mucus is produced. The body attempts to get rid of this excess by coughing it up as sputum. The color of a client’s sputum can provide cues for underlying medical conditions. For example, sputum caused by a respiratory infection is often yellow, green, or brown and often referred to as purulent sputum.[2] See Figure 8.7[3] for an image of purulent sputum.

Clients should be asked if they are experiencing chest pain. Chest pain can occur with several types of respiratory and cardiac conditions, some of which are emergent. If the client reports chest pain, first determine if it is an emergency by asking questions such as:

- “Does it feel like something is sitting on your chest?”

- “Is the pain radiating into your jaw or arm?”

- “Do you feel short of breath, dizzy, or nauseated?”

If any of these symptoms are occurring, seek emergency medical assistance according to agency policy. If it is not a medical emergency, perform a focused assessment on the chest pain, including onset, location, duration, characteristics, alleviating or aggravating factors, radiation, and if any treatment has been used for the pain.[4] Noncardiac chest pain tends to worsen with coughing and deep breathing.

Objective Assessment

Focused objective assessments for a client suspected of experiencing decreased oxygenation include assessing the airway; evaluating respiratory rate, effort, and quality; analyzing pulse oximetry readings; auscultating lung sounds for adventitious sounds; and evaluating the heart rate for tachycardia.

Signs of cyanosis or clubbing should be noted. Clubbing is the enlargement of the fingertips that occurs with chronic hypoxia such as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or congenital deficits in pediatric clients. See Figure 8.8[5] for an image of clubbing.

Another sign of chronic hypoxia that often occurs in clients with chronic respiratory diseases like COPD includes an increased anterior-posterior chest diameter, often referred to as a barrel chest. A barrel chest results from air trapping in the alveoli. See Figure 8.9[6] for an image of a barrel chest.

Diagnostic Tests and Lab Work

Diagnostic tests and lab work are based on the client’s medical condition that is causing the decreased oxygenation. For example, clients with a productive cough may have a chest X-ray or sputum culture ordered, and clients experiencing respiratory distress often have arterial blood gas (ABG) tests performed.

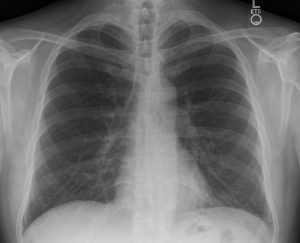

A chest X-ray is a fast and painless imaging test that uses certain electromagnetic waves to create pictures of the structures in and around the chest. This test can help diagnose and monitor conditions such as pneumonia, heart failure, lung cancer, and tuberculosis. Health care providers also use chest X-rays to see how well certain treatments are working and to check for complications after certain procedures or surgeries. Chest X-rays are contraindicated during pregnancy.[7],[8] See Figure 8.10[9] for an image of a chest X-ray.

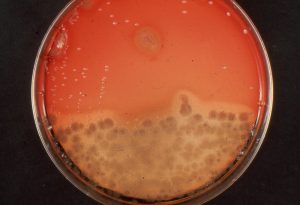

A sputum culture is a diagnostic test that evaluates the type and number of bacteria present in sputum. The client is asked to cough deeply and spit any mucus that comes up into a sterile specimen container. The sample is sent to a lab where it is placed in a special dish and is watched for two to three days or longer to see if bacteria or other disease-causing germs grow. The data is used to determine appropriate antimicrobial therapy.[10] See Figure 8.11[11] for an image of a sputum culture.

For clients experiencing respiratory distress, arterial blood gas (ABG) tests are often ordered. Additional details about ABG tests are discussed in the “Oxygenation Basic Concepts” section of this chapter, as well as in the “Acid-Base Balance” section of the “Fluid and Electrolytes” chapter. See Table 8.3a for a summary of normal ranges of ABG values in adults.

Table 8.3a Normal Ranges of ABG Values in Adults

| Value | Description | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Acid-base balance of blood | 7.35-7.45 |

| PaO2 | Partial pressure of oxygen | 80-100 mmHg |

| PaCO2 | Partial pressure of carbon dioxide | 35-45 mmHg |

| HCO3 | Bicarbonate level | 22-26 mEq/L |

| SaO2 | Calculated oxygen saturation | 95-100% |

Diagnoses

Commonly used NANDA-I nursing diagnoses for clients experiencing decreased oxygenation and dyspnea include Impaired Gas Exchange, Ineffective Breathing Pattern, Ineffective Airway Clearance, Decreased Cardiac Output, and Activity Intolerance. See Table 8.3b for definitions and selected defining characteristics for these commonly used nursing diagnoses.[12] Use a current, evidence-based nursing care plan resource when creating a care plan for a client.

Table 8.3b NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses Related to Decreased Oxygenation and Dyspnea

| NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses | Definition | Selected Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Impaired Gas Exchange | Excess or deficit in oxygenation and/or carbon dioxide elimination at the alveolar-capillary membrane. |

|

| Ineffective Breathing Pattern | Inspiration and/or expiration that does not provide adequate ventilation. | |

| Ineffective Airway Clearance | Inability to clear secretions or obstructions from the respiratory tract to maintain a clear airway. |

|

| Decreased Cardiac Output | Inadequate blood pumped by the heart to meet the metabolic demands of the body. |

|

| Activity Intolerance | Activity Intolerance: Insufficient physiological or psychological energy to endure or complete required or desired daily activities. |

|

For example, nurses commonly care for clients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). To select an accurate nursing diagnosis for a specific client with COPD, the nurse compares assessment findings with the defining characteristics of various nursing diagnoses. The nurse may select Ineffective Breathing Pattern after validating this client is demonstrating the associated signs and symptoms related to this nursing diagnosis:

- Dyspnea

- Increase in anterior-posterior chest diameter (e.g., barrel chest)

- Nasal flaring

- Orthopnea

- Prolonged expiration phase

- Pursed-lip breathing

- Tachypnea

- Use of accessory muscles to breathe

- Use of three-point position

Outcome Identification

A broad goal(s) for clients experiencing alterations in oxygenation is:

- The client will have adequate movement of air into and out of the lungs.[13]

A sample “SMART” outcome for a client experiencing dyspnea is:

- The client’s reported level of dyspnea will be within their stated desired range of 1-2 throughout their hospital stay.

Planning Interventions

According to NOC and NIC Linkages to NANDA-I and Clinical Conditions[14] and Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC),[15] Anxiety Reduction and Respiratory Monitoring are common categories of independent nursing interventions used to care for clients experiencing dyspnea and alterations in oxygenation. Anxiety Reduction is defined as, “Minimizing apprehension, dread, foreboding, or uneasiness related to an unidentified source of anticipated danger.”[16] Respiratory Monitoring is defined as, “Collection and analysis of client data to ensure airway patency and adequate gas exchange.”[17] Selected nursing interventions related to anxiety reduction and respiratory monitoring are listed in the following box.

Selected Nursing Interventions to Reduce Anxiety and Perform Respiratory Monitoring

Anxiety Reduction

- Use a calm, reassuring approach

- Explain all procedures, including sensations likely to be experienced during the procedure

- Provide factual information concerning diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis

- Stay with the client to promote safety and reduce fear

- Encourage the family to stay with the client, as appropriate

- Listen attentively

- Create an atmosphere of trust

- Encourage verbalization of feelings, perceptions, and fears

- Identify when level of anxiety changes

- Provide diversional activities geared toward the reduction of tension

- Instruct the client on the use of relaxation techniques

- Administer medications to reduce anxiety, as appropriate

Respiratory Monitoring

- Monitor rate, rhythm, depth, and effort of respirations

- Note chest movement, watching for symmetry and use of accessory muscles

- Monitor for noisy respirations such as snoring

- Monitor breathing patterns

- Monitor oxygen saturation levels in sedated clients

- Provide for noninvasive continuous oxygen sensors with appropriate alarm systems in clients with risk factors per agency policy and as indicated

- Auscultate lung sounds, noting areas of decreased or absent ventilation and presence of adventitious sounds

- Monitor client’s ability to cough effectively

- Note onset, characteristics, and duration of cough

- Monitor the client’s respiratory secretions

- Provide frequent intermittent monitoring of respiratory status in at-risk clients

- Monitor for dyspnea and events that improve and worsen it

- Monitor chest X-ray reports as appropriate

- Note changes in ABG values if ordered and notify provider as appropriate

- Institute resuscitation efforts as needed

- Institute respiratory therapy treatments as needed

In addition to the independent nursing interventions listed in the preceding box, several nursing interventions can be implemented to manage hypoxia, such as teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques, repositioning, managing oxygen therapy, administering medications, and providing suctioning. Refer to Table 8.2b in the “Oxygenation Basic Concepts” section earlier in this chapter for information about these interventions.

For additional details regarding managing oxygen therapy, see the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Read more information about respiratory medications in the "Respiratory" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Clients should also receive individualized health promotion teaching to enhance their respiratory status. Health promotion teaching includes encouraging activities such as the following:

- Receiving an annual influenza vaccine

- Receiving a pneumococcal vaccine every five years as indicated

- Stopping smoking

- Drinking adequate fluids to thin respiratory secretions

- Participating in physical activity as tolerated

Implementing Interventions

When implementing interventions that have been planned to enhance oxygenation, it is always important to assess the client’s current level of dyspnea and modify interventions based on the client’s current status. For example, if dyspnea has worsened, some interventions may no longer be appropriate (such as ambulating), and additional interventions may be needed (such as consulting with a respiratory therapist or administering additional medication).

Evaluation

After implementing interventions, the effectiveness of interventions should be documented, and the overall nursing care plan evaluated. Focused reassessments for evaluating improvement of oxygenation status include analyzing the client’s heart rate, respiratory rate, pulse oximetry reading, and lung sounds, in addition to asking the client to rate their level of dyspnea.

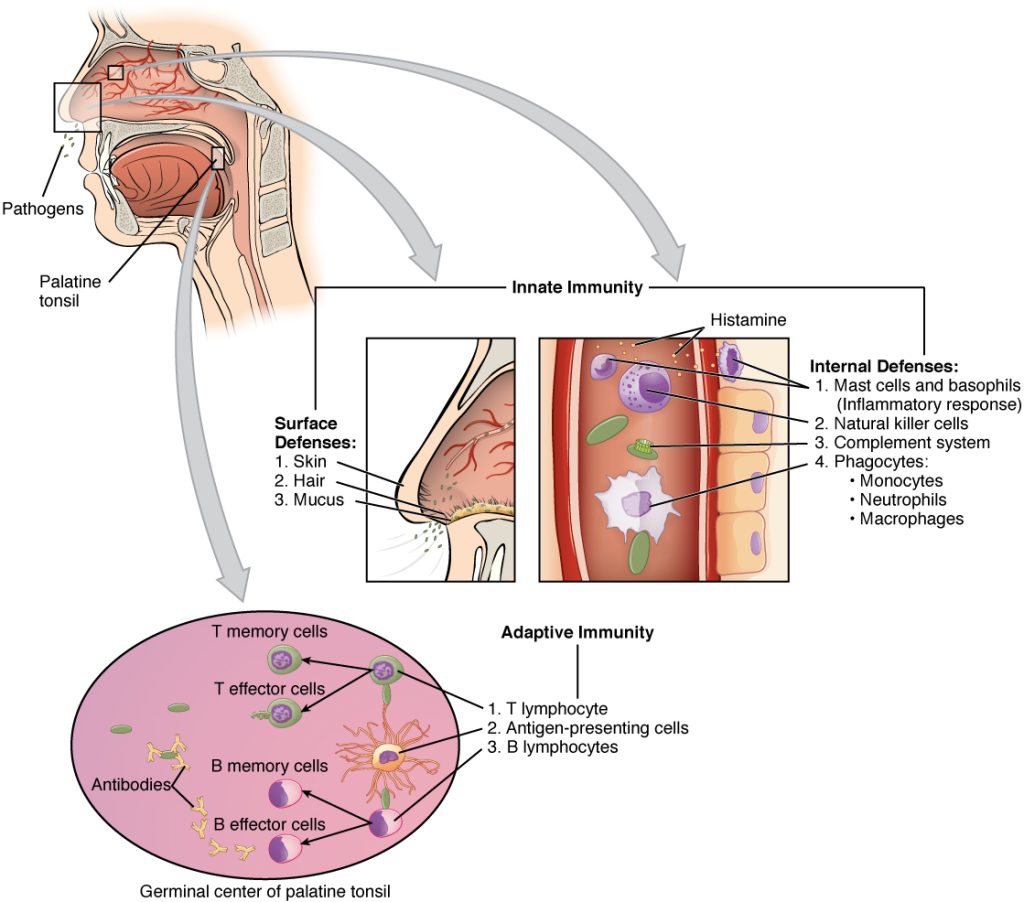

There are two basic ways the body defends against pathogens: nonspecific innate immunity and specific adaptive immunity.

Nonspecific Innate Immunity

Nonspecific innate immunity is a system of defenses in the body that targets invading pathogens in a nonspecific manner. It is called “innate” because it is present from the moment we are born. Nonspecific innate immunity includes physical defenses, chemical defenses, and cellular defenses.[18]

Physical Defenses

Physical defenses are the body’s most basic form of defense against infection. They include physical barriers to microbes, such as skin and mucous membranes, as well as mechanical defenses that physically remove microbes and debris from areas of the body where they might cause harm or infection. In addition, a person’s microbiome provides physical protection against disease as normal flora compete with pathogens for nutrients and cellular-binding sites.[19]

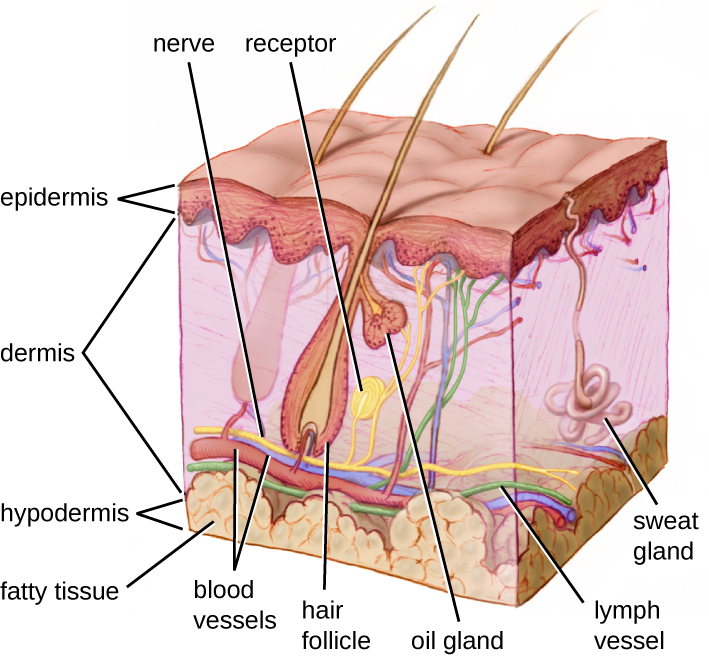

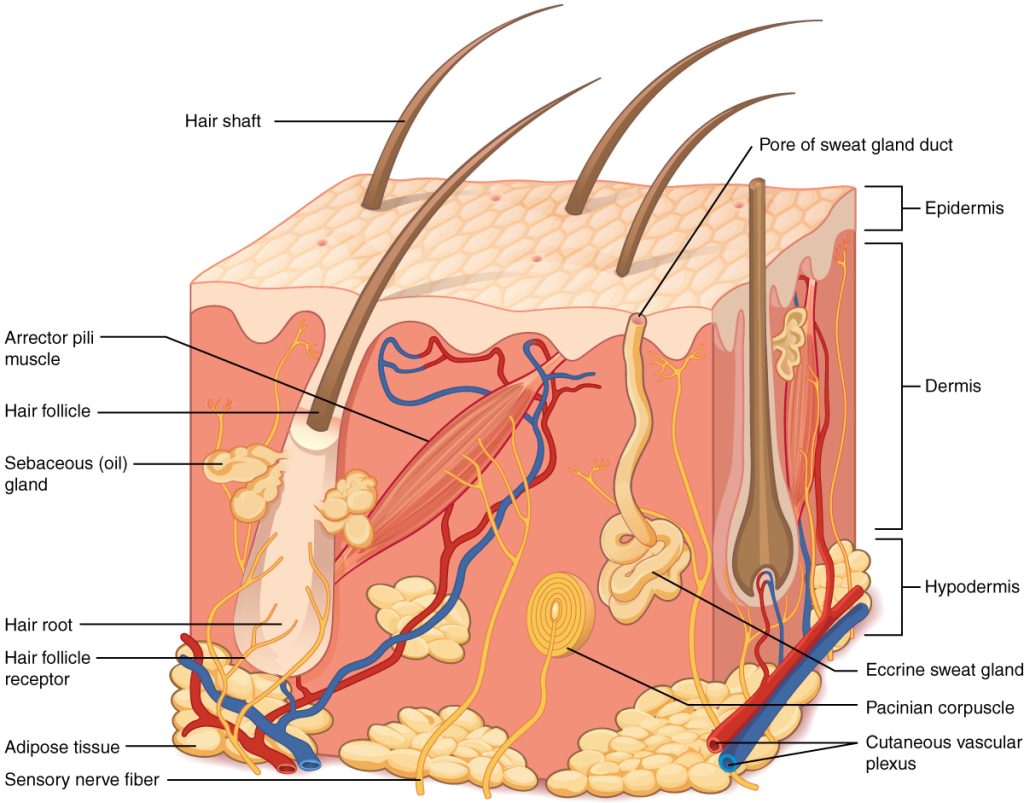

Skin

One of the body’s most important physical barriers is the skin barrier, which is composed of three layers of closely packed cells. See Figure 9.5[20] for an illustration of the layers of skin. The topmost layer of skin called the epidermis consists of cells that are packed with keratin. Keratin makes the skin’s surface mechanically tough and resistant to degradation by bacteria. Infections can occur when the skin barrier is broken, allowing the entry of opportunistic pathogens that infect the skin tissue surrounding the wound and possibly spread to deeper tissues.[21]

Mucus Membranes

The mucous membranes lining the nose, mouth, lungs, and urinary and digestive tracts provide another nonspecific barrier against potential pathogens. Mucous membranes consist of a layer of epithelial cells bound by tight junctions. The epithelial cells secrete a moist, sticky substance called mucous. Mucous covers and protects the fragile cell layers beneath it and also traps debris, including microbes. Mucus secretions also contain antimicrobial peptides.[22]

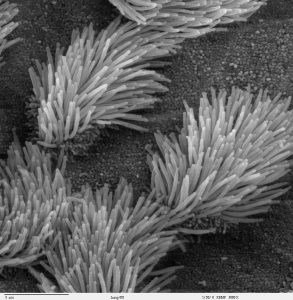

In many regions of the body, mechanical actions flush mucus (along with trapped or dead microbes) out of the body or away from potential sites of infection. For example, in the respiratory system, inhalation can bring microbes, dust, mold spores, and other small airborne debris into the body. This debris becomes trapped in the mucus lining the respiratory tract. The epithelial cells lining the upper parts of the respiratory tract have hair-like appendages known as cilia. Movement of the cilia propels debris-laden mucus out and away from the lungs. The expelled mucus is then swallowed and destroyed in the stomach, coughed up, or sneezed out. This system of removal is often called the mucociliary escalator. Disruption of the mucociliary escalator by the damaging effects of smoking can lead to increased colonization of bacteria in the lower respiratory tract and frequent infections, which highlights the importance of this physical barrier to host defenses.[23] See Figure 9.6[24] for an image of a magnified mucociliary escalator.

Like the respiratory tract, the digestive tract is a portal of entry through which microbes enter the body, and the mucous membranes lining the digestive tract provide a nonspecific physical barrier against ingested microbes. The intestinal tract is lined with epithelial cells, interspersed with mucus-secreting goblet cells. This mucus mixes with material received from the stomach, trapping foodborne microbes and debris, and is moved forward through the digestive tract via the mechanical action of peristalsis. Peristalsis refers to involuntary contraction and relaxation of the muscles of the intestine, creating wave-like movements that push digested content forward in the digestive tract.[25] For this reason, feces can contain microorganisms that can cause the spread of infection, making it essential to perform good hand hygiene to prevent transmission of disease through the fecal-oral route.

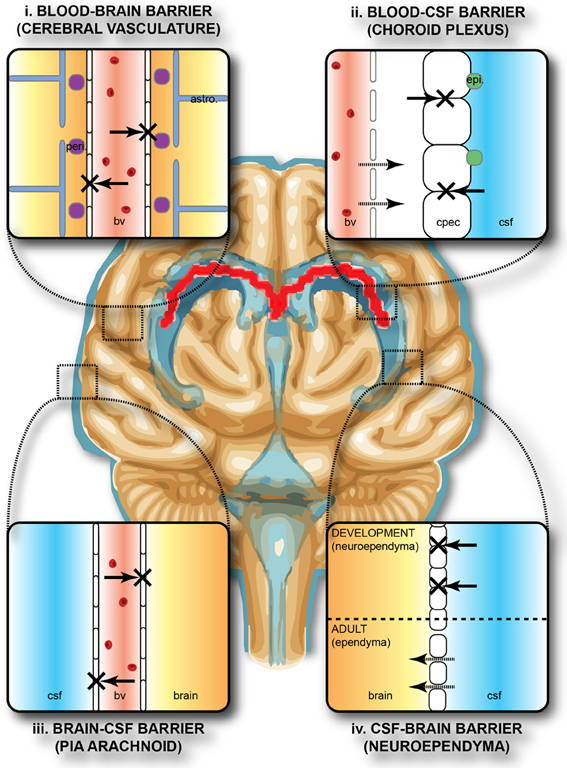

Endothelia

The epithelial cells lining the urogenital tract, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and other tissues are known as endothelia. These tightly packed cells provide an effective frontline barrier against invaders. The endothelia of the blood-brain barrier, for example, protects the central nervous system (CNS) from microorganisms. Infection of the CNS can quickly lead to serious and often fatal inflammation. The protection of the blood-brain barrier keeps the cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord sterile.[26] See Figure 9.7[27] for an illustration of the blood-brain barrier.

Mechanical Defenses

In addition to physical barriers that keep microbes out, the body has several mechanical defenses that physically remove pathogens from the body and prevent them from taking up residence. For example, the flushing action of urine and tears serves to carry microbes away from the body. The flushing action of urine is responsible for the normally sterile environment of the urinary tract. The eyes have additional physical barriers and mechanical mechanisms for preventing infections. The eyelashes and eyelids prevent dust and airborne microorganisms from reaching the surface of the eye. Any microbes or debris that make it past these physical barriers is flushed out by the mechanical action of blinking, which bathes the eye in tears, washing debris away.[28] See Figure 9.8[29] for an image of an infant’s eyelashes that prevent dust from reaching the surface of the eye.

Microbiome

Normal flora that contributes to an individual’s microbiome serve as an important first-line defense against invading pathogens. Through their occupation of cellular binding sites and competition for available nutrients, normal flora prevents the early steps of pathogen attachment and proliferation required for the establishment of an infection. For example, in the vagina, normal flora competes with opportunistic pathogens like Candida albicans. This competition prevents yeast infection by limiting the availability of nutrients and inhibiting the growth of Candida, keeping its population in check. Similar competitions occur between normal flora and potential pathogens on the skin, in the upper respiratory tract, and in the gastrointestinal tract.[30]

The importance of the normal flora in host defenses is highlighted by a person’s increased susceptibility to infectious diseases when their microbiome is disrupted or eliminated. For example, treatment with antibiotics can significantly deplete the normal flora of the gastrointestinal tract, providing an advantage for pathogenic bacteria such as Clostridium difficile (C-diff) to colonize and cause diarrheal infection. Diarrhea caused by C-diff can be severe and potentially lethal. In fact, a recent strategy for treating recurrent C-diff infections is fecal transplantation that involves the transfer of fecal material from a donor into the intestines of the client as a method of restoring their normal flora.[31]

Chemical Defenses

In addition to physical defenses, our nonspecific innate immune system uses several chemical mediators that inhibit microbial invaders. The term chemical mediators encompass a wide array of substances found in various fluids and tissues throughout the body. For example, sebaceous glands in the dermis secrete an oil called sebum that is released onto the skin surface through hair follicles. Sebum provides an additional layer of defense by helping seal off the pore of the hair follicle and preventing bacteria on the skin’s surface from invading sweat glands and surrounding tissue. Environmental factors can affect these chemical defenses of the skin. For example, low humidity in the winter makes the skin drier and more susceptible to pathogens normally inhibited by the skin’s low pH. Application of skin moisturizer restores moisture and essential oils to the skin and helps prevent dry skin from becoming infected.[32]

Examples of other chemical defenses are enzymes, pH level, and chemical mediators. Enzymes in saliva and the digestive tract eliminate most pathogens that manage to survive the acidic environment of the stomach. In the urinary tract, the slight acidity of urine inhibits the growth of potential pathogens in the urinary tract. The respiratory tract also uses various chemical mediators in the nasal passages, trachea, and lungs that have antibacterial properties.[33]

Plasma Protein Mediators

In addition to physical, mechanical, and chemical defenses, there are also nonspecific innate immune factors in plasma, the fluid portion of blood, such as acute-phase proteins, complement proteins, and cytokines. These plasma protein mediators contribute to the inflammatory response.[34]

An example of an acute-phase protein is C-reactive protein. High levels of C-reactive protein indicate inflammation caused by a serious infection or other medical condition.[35]

Complement proteins are always present in the blood and tissue fluids, allowing them to be activated quickly. They aid in the destruction of pathogens by piercing their outer membranes (cell lysis) or by making them more attractive to phagocytic cells such as macrophages.[36]

Cytokines are proteins that affect interaction and communication between cells. When a pathogen enters the body, the first immune cell to notice the pathogen is like the conductor of an orchestra. That cell directs all the other immune cells by creating and sending out messages (cytokines) to the rest of the organs or cells in the body to respond to and initiate inflammation. Too many cytokines can have a negative effect and result in what's known as a cytokine storm.[37],[38] A cytokine storm is a severe immune reaction in which the body releases too many cytokines into the blood too quickly. A cytokine storm can occur as a result of an infection, autoimmune condition, or other disease. Signs and symptoms include high fever, inflammation, severe fatigue, and nausea. A cytokine storm can be severe or life-threatening and lead to multiple organ failure. For example, many COVID-19 complications and deaths were caused by a cytokine storm.[39],[40]

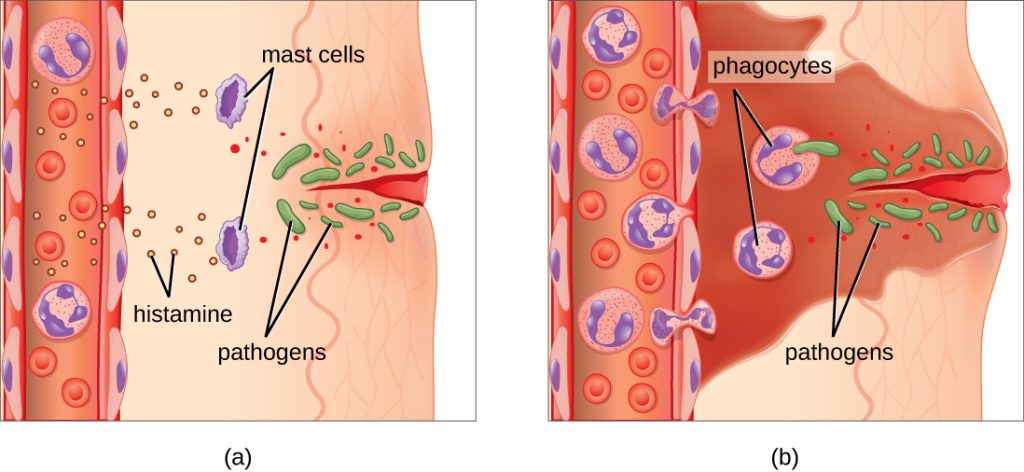

Inflammation

Inflammation is a response triggered by a cascade of chemical mediators and occurs when pathogens successfully breach the nonspecific innate immune system or when an injury occurs. Although inflammation is often perceived as a negative consequence of injury or disease, it is a necessary process that recruits cellular defenses needed to eliminate pathogens, remove damaged and dead cells, and initiate repair mechanisms. Excessive inflammation, however, can result in local tissue damage, and in severe cases, such as sepsis, it can become deadly.[41]

An immediate response to tissue injury is acute inflammation. Vasoconstriction occurs to minimize blood loss if injury has occurred. Vasoconstriction is followed by vasodilation with increased permeability of the blood vessels due to the release of histamine by mast cells. Histamine contributes to the five observable signs of the inflammatory response: erythema (redness), edema (swelling), heat, pain, and altered function. It is also associated with an influx of phagocytes at the site of injury and/or infection. See Figure 9.9[42] for an illustration of the inflammatory response, with (a) demonstrating when mast cells detect injury to nearby cells and release histamine, initiating an inflammatory response and (b) illustrating where histamine increases blood flow to the wound site and the associated increased vascular permeability allows fluid, proteins, phagocytes, and other immune cells to enter infected tissue. These events result in the swelling and reddening of the injured site. The increased blood flow to the injured site causes it to feel warm. Inflammation is also associated with pain due to these events stimulating nerve pain receptors in the tissue. Increasing numbers of neutrophils are then recruited to the area to fight pathogens. As the fight rages on, white blood cells are recruited to the area, and pus forms from the accumulation of neutrophils, dead cells, tissue fluids, and lymph. Typically, after a few days, macrophages clear out this pus.[43] During injury, if this nonspecific inflammatory process does not successfully kill the pathogens, infection occurs.

Fever

A fever is part of the inflammatory response that extends beyond the site of infection and affects the entire body, resulting in an overall increase in body temperature. Like other forms of inflammation, a fever enhances the nonspecific innate immune defenses by stimulating white blood cells to kill pathogens. The rise in body temperature also inhibits the growth of many pathogens. During fever, the client’s skin may appear pale due to vasoconstriction of the blood vessels in the skin to divert blood flow away from extremities, minimize the loss of heat, and raise the body’s core temperature. The hypothalamus also stimulates the shivering of muscles to generate heat and raise the core temperature.[44]

A low-level fever is thought to help an individual overcome an illness. However, in some instances, this immune response can be too strong, causing tissue and organ damage and, in severe cases, even death. For example, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are capable of producing superantigens that cause toxic shock syndrome and scarlet fever, respectively. Both of these conditions are associated with extremely high fevers in excess of 42 °C (108 °F) that must be managed to prevent tissue injury and death.[45]

When a fever breaks, the hypothalamus stimulates vasodilation, resulting in a return of blood flow to the skin and a subsequent release of heat from the body. The hypothalamus also stimulates sweating, which cools the skin as the sweat evaporates.[46]

Specific Adaptive Immunity

Now that we have discussed several nonspecific innate defenses against a pathogen, let’s discuss specific adaptive immunity. Specific adaptive immunity is the immune response that is activated when the nonspecific innate immune response is insufficient to control an infection. There are two types of adaptive responses: the cell-mediated immune response, which is carried out by T cells, and the humoral immune response, which is controlled by activated B cells and antibodies.[47]

B cells mature in the bone marrow. B cells make Y-shaped proteins called antibodies that are specific to each pathogen and lock onto its surface and mark it for destruction by other immune cells. The five classes of antibodies are IgG, IgM, IgA, IgD, and IgE. They also turn into memory B cells. Memory B cells are stored and released in the event a specific antigen reappears in the future. This allows the immune system to mount a quick defense because of the previously created memory B cells.[48]

T cells mature in the thymus. T cells are categorized into three classes: helper T cells, regulatory T cells, and cytotoxic T cells. Helper T cells stimulate B cells to make antibodies and help killer cells develop. Killer T cells directly kill cells that have already been infected by a pathogen. T cells also use cytokines as messenger molecules to send chemical instructions to the rest of the immune system to ramp up its response.[49]

Specific adaptive immunity also creates memory cells for each specific pathogen that provides the host with long-term protection from reinfection with that pathogen. On reexposure, these memory cells facilitate an efficient and quick immune response. For example, when an individual recovers from chicken pox, the body develops a memory of the varicella-zoster virus that will specifically protect it from reinfection if it is exposed to the virus again. Vaccines are administered with the purpose of enhancing a person's specific adaptive immunity.[50]

See Figure 9.10[51] for an illustration of innate immunity and specific adaptive immunity that occur in response to a pathogen entering the body through the nose.

Skin

Skin is made up of three layers: epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. See Figure 10.1[52] for an illustration of skin layers. The epidermis is the thin, topmost layer of the skin. It contains sweat gland duct openings and the visible part of hair known as the hair shaft. Underneath the epidermis lies the dermis where many essential components of skin function are located. The dermis contains hair follicles (the roots of hair shafts), sebaceous oil glands, blood vessels, endocrine sweat glands, and nerve endings. The bottommost layer of skin is the hypodermis (also referred to as the subcutaneous layer). It mostly consists of adipose tissue (fat), along with some blood vessels and nerve endings. Beneath the hypodermis layer lies bone, muscle, ligaments, and tendons.

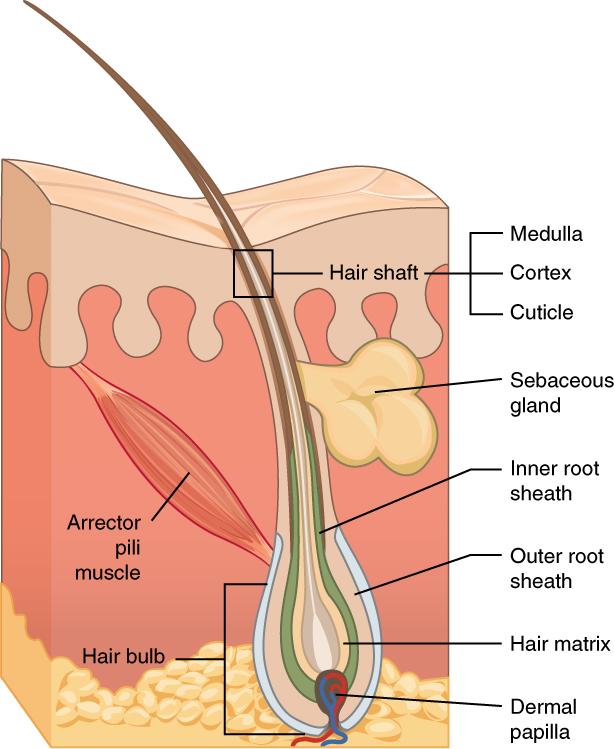

Hair

Hair is a filament that grows from a hair follicle in the dermis of the skin. See Figure 10.2[53] for an illustration of a hair follicle. It consists mainly of tightly packed, keratin-filled cells called keratinocytes. The human body is covered with hair follicles except for the mucous membranes, lips, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet. The part of the hair that is located within the follicle is called the hair root, the only living part of the hair. The part of the hair that is visible above the surface of the skin is the hair shaft. The shaft of the hair has no biochemical activity and is considered dead.

Functions of Hair

The functions of head hair are to provide insulation to retain heat and to protect the skin from damage by UV light. The function of hair in other locations on the body is debated. One idea is that body hair helps to keep us warm in cold weather. When the body is cold, the arrector pili muscles contract, causing hairs to stand up and trapping a layer of warm air above the epidermis. However, this action is more effective in mammals that have thick hair than it is in relatively hairless human beings.

Human hair has an important sensory function as well. Sensory receptors in the hair follicles can sense when the hair moves, whether it is because of a breeze or the touch of a physical object. Some hairs, such as the eyelashes, are especially sensitive to the presence of potentially harmful matter. The eyebrows protect the eyes from dirt, sweat, and rain. In addition, the eyebrows play a key role in nonverbal communication by expressing emotions such as sadness, anger, surprise, and excitement.[54]

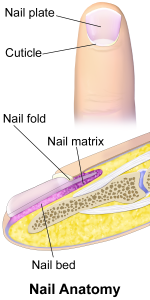

Nails

Nails are accessory organs of the skin. They are made of sheets of dead keratinocytes and are found on the distal ends of the fingers and toes. The keratin in nails makes them hard but flexible. Nails serve a number of purposes, including protecting the fingers, enhancing sensations, and acting like tools. A nail has three main parts: root, plate, and free margin. Other structures around or under the nail include the nail bed, cuticle, and nail fold. See Figure 10.3 for an illustration of the structure of a nail.[55],[56] The top diagram in this figure shows the external, visible part of the nail and the cuticle. The bottom diagram shows internal structures in a cross-section of the nail and nail bed.

Impaired Skin and Tissue Integrity

Skin integrity is a medical term that refers to skin health. Impaired skin integrity is a NANDA-I nursing diagnosis defined as, “Altered epidermis/or dermis.”[57] However, when deeper layers of the skin or integumentary structures are damaged, it is referred to as impaired tissue integrity. The NANDA-I definition of impaired tissue integrity is, “Damage to the mucous membrane, cornea, integumentary system, muscular fascia, muscle, tendon, bone, cartilage, joint capsule, and/or ligament.”[58]

Risk Factors Affecting Skin Health and Wound Healing

There are several risk factors that place a client at increased risk for altered skin health and delayed wound healing. Risk factors include impaired circulation and oxygenation, impaired immune function, diabetes, inadequate nutrition, obesity, exposure to moisture, smoking, and age. Each of these risk factors is discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

Impaired Circulation and Oxygenation

Skin, like every other organ in the body, depends on good blood perfusion to keep it healthy and functioning correctly. Cardiovascular circulation delivers important oxygen, nutrients, infection-fighting cells, and clotting factors to tissues. These elements are needed by skin, tissues, and nerves to properly grow, function, and repair damage. Without good cardiovascular circulation, skin becomes damaged. Damage can occur from poor blood perfusion from the arteries, as well as from poor return of blood through the veins to the heart. Common medical conditions that decrease cardiovascular circulation include cardiac disease, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD). PVD includes two medical conditions called arterial insufficiency and venous insufficiency.

Arterial Insufficiency

Arterial insufficiency refers to a lack of adequately oxygenated blood movement in arteries to specific tissues. Arterial insufficiency can be a sudden, acute lack of oxygenated blood, such as when a blood clot in an artery blocks blood flow to a specific area. Arterial insufficiency can also be a chronic condition caused by peripheral vascular disease (PVD). As a person’s arteries become blocked with plaque due to atherosclerosis, there is decreased blood flow to the tissues. Signs of arterial insufficiency are cool skin temperature, pale skin color, pain that increases with exercise, and possible arterial ulcers.

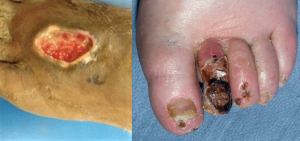

When oxygenated blood flow to tissues becomes inadequate, the tissue dies. This is called necrosis. Tissue death causes the skin and tissue to become necrotic (black). Necrotic tissue does not heal, so surgical debridement or amputation of the extremity becomes necessary for healing. See Figure 10.4[59] for images of an arterial insufficiency ulcer and necrotic toes.

Venous Insufficiency

Venous insufficiency occurs when the cardiovascular system cannot adequately return blood and fluid from the extremities to the heart. Venous insufficiency can cause stasis dermatitis when blood pools in the lower legs and leaks out into the skin and other tissues. Signs of venous insufficiency are edema, a brownish-leathery appearance to skin in the lower extremities, and venous ulcers that weep fluid.[60] See Figure 10.5[61] for an image of stasis dermatitis.

Impaired Immune Function

Skin contributes to the body’s immune function and is also affected by the immune system. Intact skin provides an excellent first line of defense against microorganisms entering the body. This is why it is essential to keep skin intact. If skin does break down, the next line of defense is a strong immune system that attacks harmful invading organisms. However, if the immune system is not working well, the body is much more susceptible to infections. This is why maintaining intact skin, especially in the presence of an impaired immune system, is imperative to decrease the risk of infections.

Stress can cause an impaired immune response that results in delayed wound healing.[62] Being hospitalized or undergoing surgery triggers the stress response in many clients. Medications, such as corticosteroids, also affect a client’s immune function and can impair wound healing.[63] When assessing a chronic wound that is not healing as expected, it is important to consider the potential effects of stress and medications.

Diabetes

Diabetes can cause wounds to develop, as well as delayed healing of wounds. This is due to elevated blood glucose causing stiffening of arterial walls, resulting in decreased circulation and tissue hypoxia. Elevated blood glucose also reduces leukocyte function, directly affecting wound healing and risk for infection. Additionally, if clients with diabetes also have diabetic neuropathy, they do not feel pain associated with skin injuries, resulting in delayed treatment and further risk of infection.[64] Nurses provide vital health teaching to clients with diabetes to help them effectively manage the disease and prevent complications.

Read more about diabetes in the “Antidiabetics” section of the “Endocrine” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Inadequate Nutrition

A healthy diet is essential for maintaining healthy skin, as well as maintaining an appropriate weight. Nutrients that are particularly important for skin health include protein; vitamins A, C, D, and E; and minerals such as selenium, copper, and zinc.[65]

Nutritional deficiencies can have a profound impact on wound healing and must be addressed for chronic wounds to heal. Protein is one of the most important nutritional factors affecting wound healing. For example, in clients with pressure injuries, 30 to 35 kcal/kg of calorie intake with 1.25 to 1.5g/kg of protein and micronutrients supplementation are recommended daily.[66] In addition, vitamin C and zinc have many roles in wound healing. It is important to collaborate with a dietician to identify and manage nutritional deficiencies when a client is experiencing poor wound healing.[67]

Obesity

In the same way a balanced diet is vital for healthy skin, a healthy weight is also imperative. Obese individuals are at increased risk for fungal and yeast infections in skin folds caused by increased moisture and friction. See Figure 10.6[68] for an image of a fungal infection in the groin.[69] Symptoms of yeast and fungal infection include redness and scaliness of the skin associated with itching.

Obese clients also are at higher risk for wound complications due to a decreased supply of oxygenated blood flow to adipose tissue. Potential complications include infection, dehiscence (separation of the edges of a surgical wound), hematoma formation, pressure injuries, and venous ulcers.[70] Evisceration is a rare but severe complication when an abdominal surgical incision separates and the abdominal organs protrude or come out of the incision. Nurses can educate clients about making healthy lifestyle choices to reduce obesity and the risk of dehiscence. See Figure 10.7[71] for an image of a dehiscence in an abdominal surgical wound of an obese client.

Exposure to Moisture

Healthy skin needs good moisture balance. If too much moisture (i.e., sweat, urine, or water) is left on the skin for extended periods of time, the skin will become soggy, wrinkly, and turn whiter than usual and is called maceration. A simple example of maceration is when you spend too much time in a bathtub and your fingers and toes turn white and get “pruny.” See Figure 10.8[72] for an image of maceration. If healthy skin is exposed to moisture for an extended period of time, such as when a moist wound dressing is incorrectly applied on healthy skin, the skin will break down. This type of skin breakdown is called excoriation. Excoriation refers to removal of the topmost surface of the skin, which results in redness and abrasions. See Figure 10.9[73] for an image of excoriation.

The opposite occurs when skin lacks proper moisture. Skin becomes flaky, itchy, and cracked when it becomes too dry. Conditions such as decreased moisture in the air during cold winter months or bathing in hot water can worsen skin dryness. Dry skin, especially when accompanied with cracking, breaks the protective barrier and increases the risk of infection. It is important for nurses to apply emollient cream to clients’ areas of dry skin to maintain the protective skin barrier.

Smoking

Smoking impacts the inflammatory phase of the wound healing process, which can result in poor wound healing and an increased risk of infection, wound dehiscence, and necrosis. This is likely due to tissue hypoxia caused by toxins in tobacco smoke such as carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, as well as vasoconstriction caused by nicotine.[74],[75] Clients who smoke should be encouraged to stop smoking.

Age

Older adults have thin, less elastic skin that puts them at increased risk for injury. They also have an altered inflammatory response that can impair wound healing. Additionally, the elderly are at risk for poor nutrition that contributes to poor wound healing. Nurses teach older clients about the importance of exercise for skin health and improved wound healing as appropriate.[76]

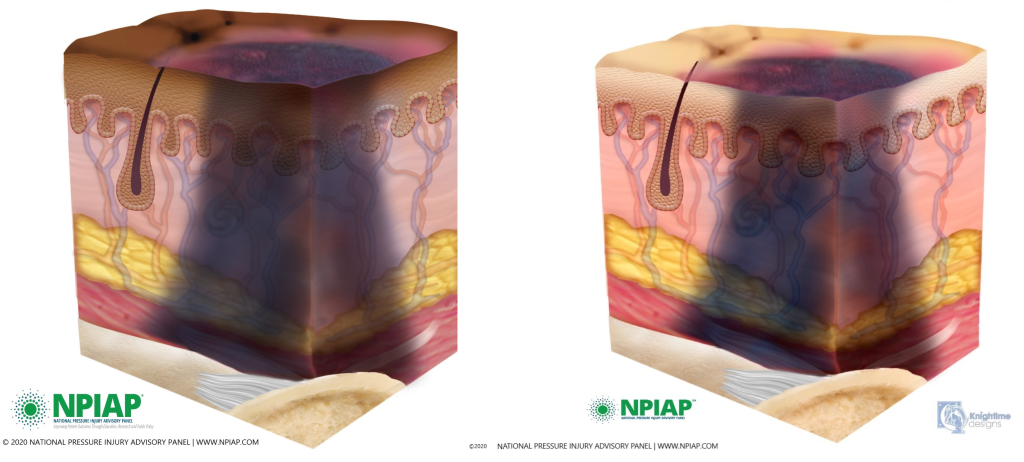

The remainder of this chapter will focus on applying the nursing process to a specific type of wound called a pressure injury. Pressure injuries are defined as, “Localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.” (Note that the 2016 NPUAP Pressure Injury Staging System now uses the term “pressure injury” instead of the historic term “pressure ulcer” because a pressure injury can occur without an ulcer present.) Pressure injuries commonly occur on the sacrum, heels, ischia, and coccyx and form when the skin layer of tissue gets caught between an external hard surface, such as a bed or chair, and the internal hard surface of a bone.

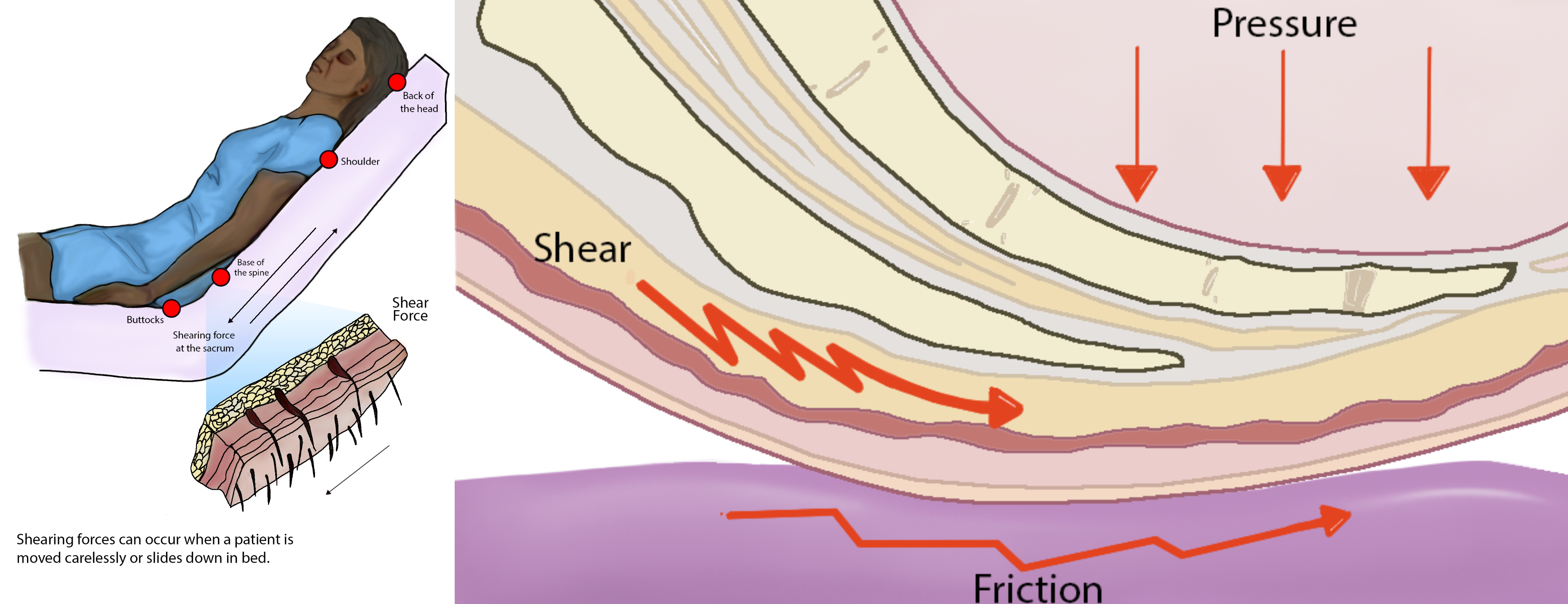

Shear occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue. For example, when a client slides down in bed, the outer layer of skin remains immobile because it remains attached to the sheets due to friction. However, the deeper layer of tissue (attached to bone) moves as the client slides down. This opposing movement of the outer layer of skin and the underlying tissues causes the capillaries to stretch and tear, which then causes decreased blood flow and oxygenation of the surrounding tissues resulting in a pressure injury.[77]

Friction refers to rubbing the skin against a hard object, such as the bed or the arm of a wheelchair. This rubbing causes heat, which can remove the top layer of skin and often results in skin damage. See Figure 10.13[78] for an illustration of shear and friction forces in the development of pressure injuries.

Hospital-acquired or worsening pressure injuries during hospitalization are considered "never events," meaning they are a serious, preventable medical errors that should never occur and require reporting to The Joint Commission. Additionally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and many private insurers will no longer pay for additional costs associated with "never events."[79],[80] Pressure injuries can be prevented with diligent assessment and nursing interventions such as frequent repositioning and providing good skin care.

Staging

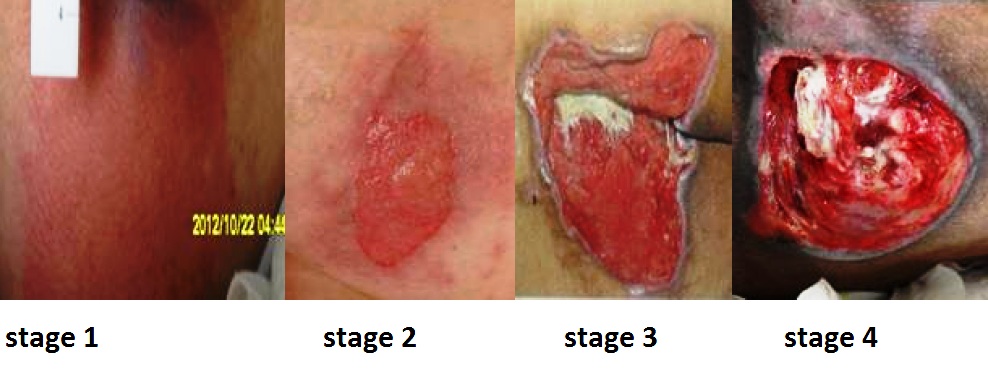

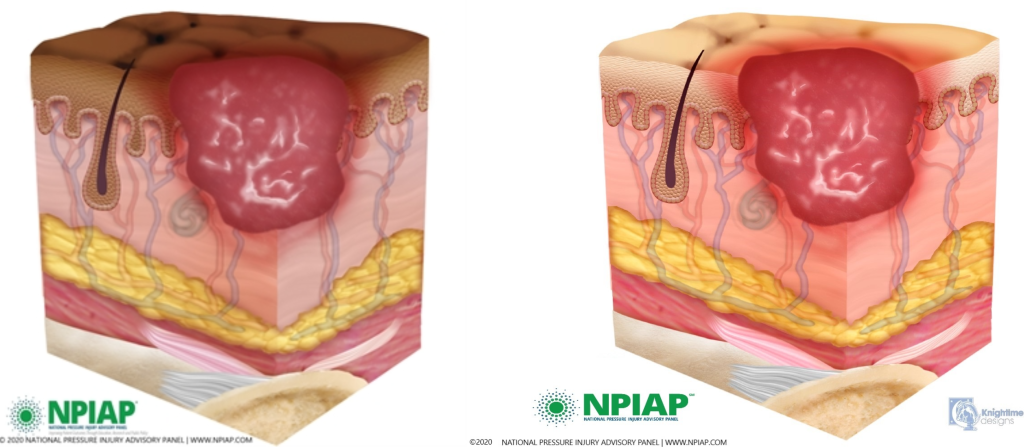

When assessed, pressure injuries are staged from 1 through 4 based on the extent of tissue damage. For example, Stage 1 pressure injuries have the least amount of tissue damage as evidenced by reddened, intact skin, whereas Stage 4 pressure injuries have the greatest amount of damage with deep, open ulcers affecting underlying tissue, muscle, ligaments, or tendons. See Figure 10.14[81] for images of four stages of pressure injuries.[82] Each stage is further described in the following subsections.

Stage 1 Pressure Injuries

Stage 1 pressure injuries are intact skin with a localized area of nonblanchable erythema where prolonged pressure has occurred. Nonblanchable erythema is a medical term used to describe an area of reddened skin that does not turn white when pressed. Nonblanchable erythema is an early sign of damage to underlying tissue caused by poor blood flow, ischemia, and damage to blood vessels in the area. Because damage is already present, there is a greater risk for Stage 1 pressure injuries to develop into worse pressure injuries if interventions to relieve pressure and not implemented. Skin with dark pigmentation may not demonstrate visible blanching, so it can be challenging to detect Stage 1 pressure injuries. For clients with dark pigmentation, nurses should assess for pain, firmness, softness, changes in temperature, or changes in color compared to surrounding areas.[83],[84]

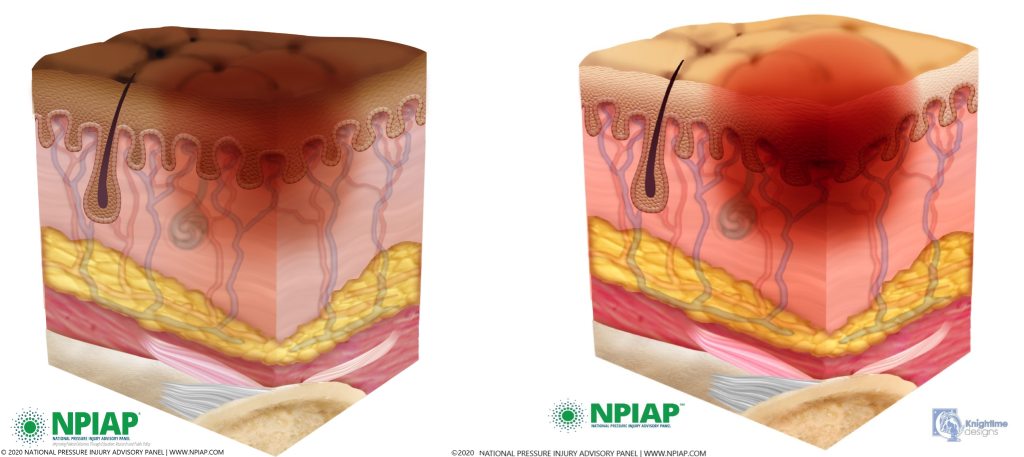

See Figure 10.15[85] for an illustration of a Stage 1 pressure injury.

Stage 2 Pressure Injuries

Stage 2 pressure injuries are partial-thickness loss of skin with exposed dermis. The wound has completely broken through the top layer of skin, and partly through the second layer, resulting in a shallow wound. The wound is shallow and generally open. The wound bed is viable and may appear like an intact or ruptured blister.[86] The wound area may be painful and the surrounding tissue may be swollen or discolored.[87] See Figure 10.16[88] for an illustration of a Stage 2 pressure injury.

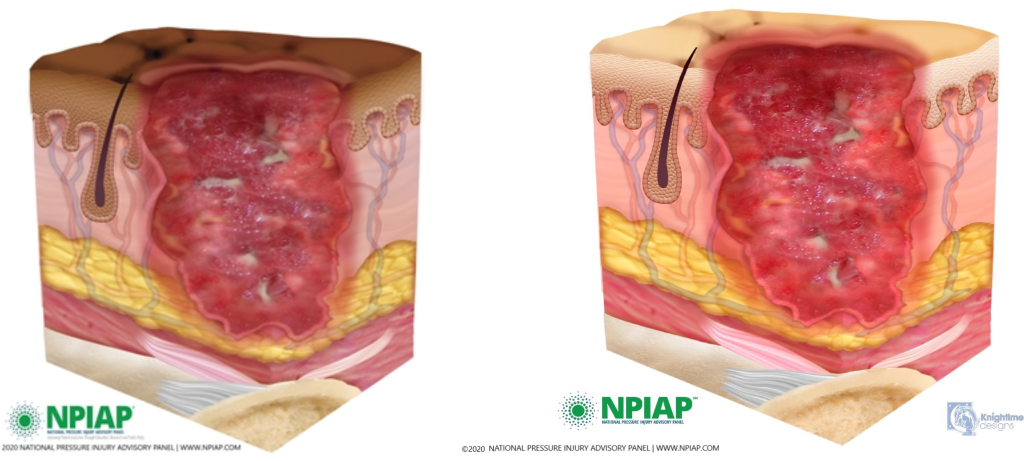

Stage 3 Pressure Injuries

Stage 3 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss in which fat is visible, but cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, and bone are not exposed. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location. Because the wound extends through all skin layers, there is increased risk of infection in Stage 3 pressure injuries. There may be pus draining from the wound, tissue necrosis, pain, or fever, especially in the presence of an infection.[89] See Figure 10.17[90] for an illustration of a Stage 3 pressure injury.

Undermining and tunneling may occur in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edge becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin. Tunneling refers to passageways underneath the skin surface that extend from a wound and can take twists and turns.

Slough and eschar may also be present in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Slough is inflammatory exudate that is usually light yellow, soft, and moist. Eschar is dark brown/black, dry, thick, and leathery dead tissue. If slough or eschar obscures the wound so that tissue loss cannot be assessed, the pressure injury is referred to as unstageable.[91] In most wounds, slough and eschar must be removed by debridement for accurate wound staging and for healing to occur. Removed of slough or eschar is surgically performed by specially trained health care providers. Nurses may apply prescribed chemical debridement agents or wet-to-dry dressings for mechanical debridement per provider orders.

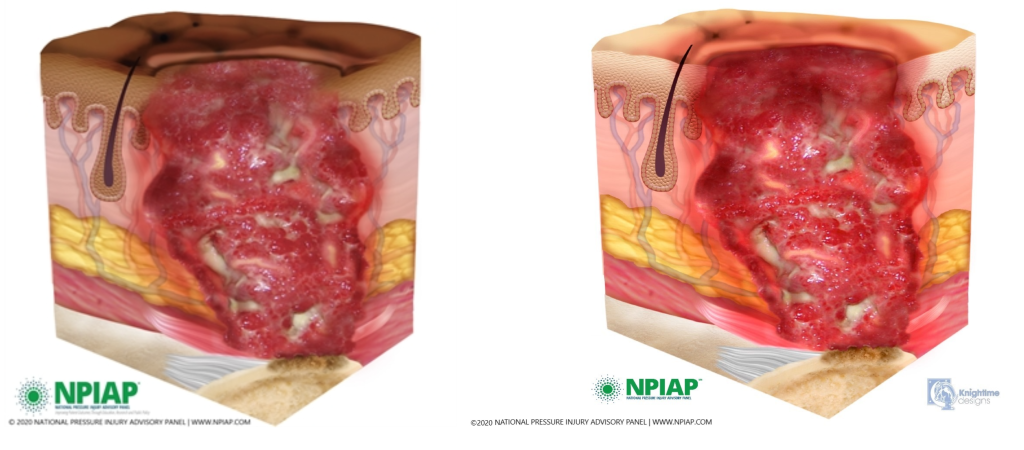

Stage 4 Pressure Injuries

Stage 4 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss, like in Stage 3 pressure injuries, but also have exposed cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, or bone. Stage 4 pressure injuries are at an increased risk of infection because their depth goes through all skin layers. There may be pain associated with Stage 4 pressure ulcers, although they are often less painful because the wound damages nerve endings. There also at be firm or mushy texture at the site, discoloration, or necrosis to the wound. Because the wound often extends to the bone, thus exposing the bone to infectious agents in the environment, osteomyelitis (bone infection) may also be present. Osteomyelitis is a serious bone infection that may require amputation or cause death if not promptly treated aggressively with antibiotics.[92],[93]

See Figure 10.18[94] for an illustration of a Stage 4 pressure injury.

View images of different stages of pressure injuries on people with dark skin tones on the PPPIA Pressure Ulcers in People With Dark Skin Tones poster.

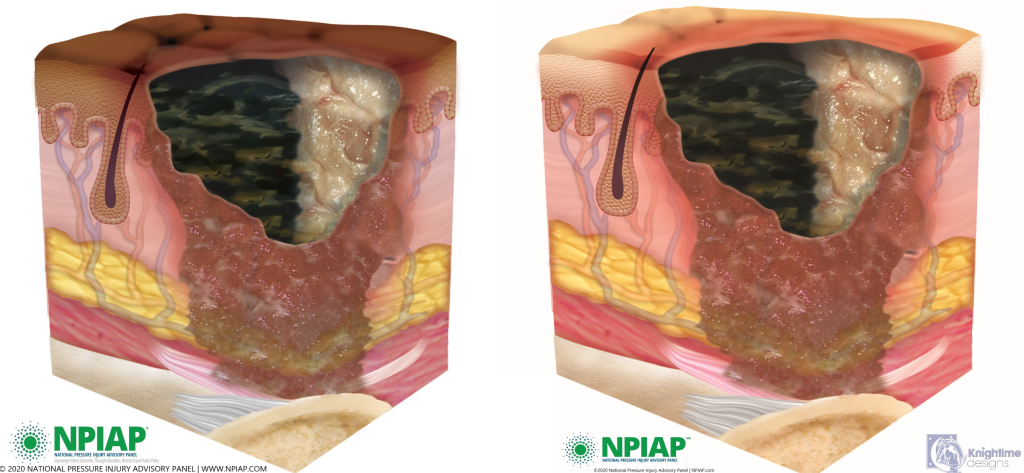

Unstageable Pressure Injuries

Unstageable pressure injuries are full-thickness skin and tissue loss in which the extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar. If slough or eschar were to be removed, a Stage 3 or Stage 4 pressure injury would likely be revealed. However, dry and adherent eschar on the heel or ischemic limb is not typically removed.[95] See Figure 10.19[96] for an illustration of an unstageable pressure ulcer due to the presence of eschar (on the left side of the wound) and slough (on the right side of the wound).

Deep Tissue Pressure Injuries

Deep tissue pressure injuries consist of persistent nonblanchable and deep red, maroon, or purple discoloration of an area. These discolorations typically reveal a dark wound bed or blood-filled blister. Be aware that the discoloration may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. Deep tissue injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure, as well as shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or it may resolve without tissue loss.[97],[98] See Figure 10.20 for an illustration of a deep tissue injury.

Video Review of Assessing Pressure Injuries[99]

Assessment

Subjective Assessment

During a subjective assessment of a client’s integumentary system, begin by asking about current symptoms such as itching, rashes, or wounds. If a client has a wound, it is important to determine if a client has pain associated with the wound so that pain management can be implemented. For clients with chronic wounds, it is also important to identify factors that delay wound healing, such as nutrition, decreased oxygenation, infection, stress, diabetes, obesity, medications, alcohol use, and smoking.[100] See Table 10.6a for a list of suggested interview questions to use when assessing a client with a wound.

If a client has a chronic wound or is experiencing delayed wound healing, it is important for the nurse to assess the impact of the wound on their quality of life. Reasons for this may include the frequency and regularity of dressing changes, which affect daily routine; a feeling of continued fatigue due to lack of sleep; restricted mobility; pain; odor; and the side effects of multiple medications. The loss of independence associated with functional decline can also lead to changes in overall health and well-being. These changes include altered eating habits, depression, social isolation, and a gradual reduction in activity levels.

Table 10.6a Interview Questions Related to Integumentary Disorders

| Symptoms | Questions | Follow-up Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Current Symptoms | Are you currently experiencing any skin symptoms such as itching, rashes, or an unusual mole? | Please describe. |

| Wounds | Do you have any current wounds such as a surgical incision, skin tear, arterial ulcer, venous ulcer, diabetic or neuropathic ulcer, or a pressure injury?

If a wound is present:

|

Please describe.

Use the PQRSTU method to comprehensively assess pain. Read more about the PQRSTU method in the "Pain Assessment Methods" section of the "Comfort" chapter. |

| Medical History | Have you ever been diagnosed with a wound related to diabetes, heart disease, or peripheral vascular disease? | Please describe. |

| If chronic wounds or wounds with delayed healing are present: | ||

| Medications | Are you taking any medications that can affect wound healing, such as oral steroids to treat inflammation or help you breathe? | Please describe. |

| Treatments | What have you used to try to treat this wound? | What was successful? Unsuccessful? |

| Symptoms of Infection (pain, purulent drainage, etc.) | Are you experiencing any symptoms of infection related to this wound such as increased pain or yellow/green drainage? | Please describe. |

| Stress | Have you experienced any recent stressors such as surgery, hospitalization, or a change in life circumstances? | How do you cope with stress in your life? |

| Smoking | Do you smoke? | How many cigarettes do you smoke a day? How long have you smoked? Have you considered quitting smoking? |

| Quality of Life | Has this wound impacted your quality of life? | Have you had any changes in eating habits, feelings of depression or social isolation, or a reduction in your usual activity levels? |

Objective Assessment

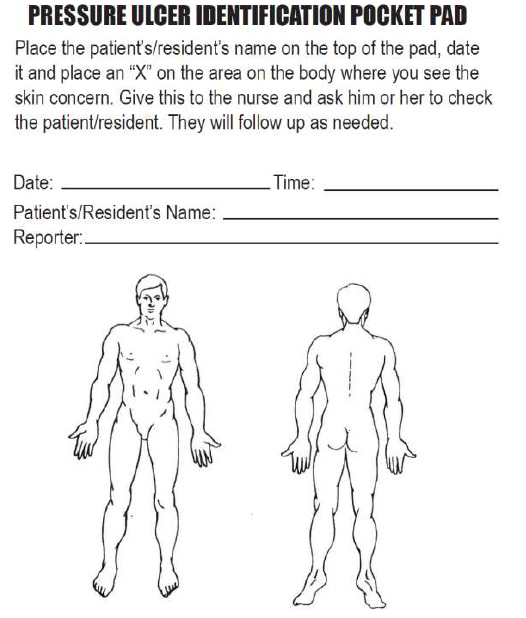

When performing an objective integumentary assessment on a client receiving inpatient care, it is important to perform a thorough exam on admission to check for existing wounds, as well as to evaluate their risk of skin breakdown using the Braden Scale. Agencies are not reimbursed for care of pressure injuries received during a client’s stay, so existing wounds on admission must be well-documented. Routine skin assessment should continue throughout a client’s stay, usually on a daily or shift-by-shift basis based on the client’s condition. If a wound is present, it is assessed during every dressing change for signs of healing. See Table 10.6b for components to include in a wound assessment. See Figure 10.22[101] for an image of a common tool used to document the location of a skin concern found during assessment.

Read more information about performing an overall integumentary assessment in the “Integumentary Assessment” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

For additional discussion regarding assessing wounds, go to the “Assessing Wounds” section of the “Wound Care” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

There are many common skin disorders that a nurse may find during assessment. Read more about common skin disorders in the “Common Integumentary Conditions” section of the “Integumentary Assessment” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Table 10.6b Wound Assessment

| Wound Assessment | |

|---|---|

| Type | Types of wounds may include abrasions, lacerations, burns, surgical incisions, pressure injuries, skin tears, arterial ulcers, or venous ulcers. It is important to understand the type of wound present to select appropriate interventions. |

| Location | The location of the wound should be documented precisely. A body diagram template is helpful to demonstrate exactly where the wound is located. |

| Size | Wound size should be measured regularly to determine if the wound is increasing or decreasing in size. Length is measured using the head-to-toe axis, and width is measured laterally. If tunneling or undermining is present, their depth should be assessed using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator and documented using the clock method. |

| Degree of Tissue Injury | Wounds are classified as partial-thickness (meaning the epidermis and dermis are affected) or full-thickness (meaning the subcutaneous and deeper layers are affected). See Figure 10.1 in the “Basic Concepts” section for an image of the layers of skin.

For pressure injuries, it is important to assess the stage of the injury (see information on staging in the “Pressure Injuries” section). |

| Color of Wound Base | Assess the base of the wound for the presence of healthy, pink/red granulation tissue. Note the unhealthy appearance of dark red granulation tissue, white or yellow slough, or brown or black necrotic tissue. |

| Drainage | The color, consistency, and amount of exudate (drainage) should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Drainage from wounds is often described as scant, small/minimal, moderate, and large/copious amounts. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms:[102]

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent:

|

| Tubes or Drains | Check for patency and if they are attached correctly. |

| Signs and Symptoms of Infection | Assess for signs and symptoms of infection, which include the following:

|

| Wound Edges and Periwound | Assess the surrounding skin for maceration or signs of infection. |

| Pain | Assess for pain in the wound or during dressing changes. If pain is present, use the PQRSTU or OLDCARTES method to obtain a comprehensive pain assessment. |

See Table 10.6c for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings on integumentary assessment.

Table 10.6c Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | Color: appropriate for ethnicity

Temperature: warm to touch Texture: smooth, soft, and supple Turgor: resilient Integrity: no wounds or lesions noted Sensory: no pain or itching noted |

Color: pale, white, red, yellow, purple, black and blue

Temperature: cool or hot to touch Texture: rough, scaly or thick; thin and easily torn; dry and cracked Turgor: tenting noted Integrity: rashes, lesions, abrasions, burns, lacerations, surgical wounds, pressure injuries noted Pain or pruritus (itching) present |

| Hair | Full distribution of hair on the head, axilla, and genitalia | Alopecia (hair loss), hirsutism (excessive hair growth over body), lice and/or nits, or lesions under hair |

| Nails | Smooth, well-shaped, and firm but flexible | Cracked, chipped, or splitting nail; excessively thick; presence of clubbing; ingrown nails |

| Skin Integrity | Skin intact with no wounds or pressure injuries. Braden Scale is 23 | A wound or pressure injury is present, or there is risk of developing a pressure injury with a Braden scale score of less than 23 |

Diagnostic and Lab Work

When a chronic wound is not healing as expected, laboratory test results can provide additional clues for the delayed healing. See Table 10.6d for a summary of lab results that offer clues to systemic issues causing delayed wound healing.

Table 10.6d Lab Values Associated with Delayed Wound Healing[108]

| Abnormal Lab Value | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Low hemoglobin | Low hemoglobin indicates less oxygen is transported to the wound site. |

| Elevated white blood cells (WBC) | Increased WBC indicates infection is occurring. |

| Low platelets | Platelets have an important role in the creation of granulation tissue. |

| Low albumin | Low albumin indicates decreased protein levels. Protein is required for effective wound healing. |

| Elevated blood glucose or hemoglobin A1C | Elevated blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C levels indicate poor management of diabetes mellitus, a disease that negatively impacts wound healing. |

| Elevated serum BUN and creatinine | BUN and creatinine levels are indicators of kidney function, with elevated levels indicating worsening kidney function. Elevated BUN (blood urea nitrogen) levels impact wound healing because it can indicate increased breakdown of the body's protein stores due to deficient protein in the diet. |

| Positive wound culture | Positive wound cultures indicate an infection is present and provide additional information including the type and number of bacteria present, as well as identifying antibiotics the bacteria is susceptible to. The nurse reviews this information when administering antibiotics to ensure the prescribed therapy is effective for the type of bacteria present. |

Life Span and Cultural Considerations

Newborns and Infants