17.3 Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Many federal and state laws, as well as national guidelines, have been established to protect public health and safety related to medication administration. This section will explain how federal and state laws, agencies, and guidelines protect clients from harm from medications.

Federal Agencies, Laws, and Guidelines

Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) protects public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices, as well as the safety of our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation.[1] The FDA protects public health by enforcing an official drug approval process based on evidence-based research and issuing Boxed Warnings for medications with serious adverse reactions. These actions are further discussed in the following subsections.

Developing New Drugs

American consumers benefit from having access to the safest and most advanced pharmaceutical system in the world. The main consumer watchdog in this system is the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). The center’s best-known job is to evaluate new drugs before they can be sold. CDER’s evaluation not only prevents misinformation from being provided to the public, but also provides doctors and clients the information they need to use medicines wisely. CDER ensures that drugs, both brand-name and generic, work correctly and their health benefits outweigh their known risks.

Drug companies conduct extensive research and work to develop and test a drug. The company then sends CDER the evidence from these tests to prove the drug is safe and effective for its intended use. Before the drug is approved as safe for use in the United States, a team of CDER physicians, statisticians, chemists, pharmacologists, and other scientists reviews the company’s data and proposed labeling. If this independent and unbiased review establishes a drug’s health benefits outweigh its known risks, the drug is approved for sale. Before a drug can be tested in people, the drug company or sponsor performs laboratory and animal tests to discover how the drug works and whether it’s likely to be safe and work well in humans. Next, a series of clinical trials involving volunteers is conducted to determine whether the drug is safe when used to treat a disease and whether it provides a real health benefit.

Visit the FDA’s “Development and Approval Process | Drugs” webpage.

FDA Approval of a Drug

FDA approval of a drug means that data on the drug’s effects have been reviewed by the CDER, and the drug is determined to provide benefits that outweigh its known and potential risks for the intended population. The drug approval process takes place within a structured framework that includes the following:

- Analysis of the target condition and available treatments: FDA reviewers analyze the condition or illness for which the drug is intended and evaluate the current treatment landscape, which provide the context for weighing the drug’s risks and benefits. For example, a drug intended to treat clients with a life-threatening disease for which no other therapy exists may be considered to have benefits that outweigh the risks even if those risks would be considered unacceptable for a condition that is not life-threatening.

- Assessment of benefits and risks from clinical data: FDA reviewers evaluate clinical benefit and risk information submitted by the drug maker, taking into account any uncertainties that may result from imperfect or incomplete data. Generally, the agency expects that the drug maker will submit results from two well-designed clinical trials to be sure the findings from the first trial are not the result of chance or bias. In certain cases, especially if the disease is rare and multiple trials may not be feasible, convincing evidence from one clinical trial may be enough. Evidence that the drug will benefit the target population should outweigh any risks and uncertainties.

- Strategies for managing risks: All drugs have risks. Risk management strategies include an FDA-approved drug label, which clearly describes the drug’s benefits and risks and information pertaining to the detection and management of any risks. Sometimes, more effort is needed to manage risks. In these cases, a drug maker may need to implement a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

Although many of the FDA’s risk-benefit assessments and decisions are straightforward, sometimes the benefits and risks are uncertain and may be difficult to interpret or predict. The agency and the drug maker may reach different conclusions after analyzing the same data, or there may be differences of opinion among members of the FDA’s review team. As a science-led organization, the FDA uses scientific and technological information to make decisions through a deliberative process.[2]

Boxed Warnings

As discussed in the previous subsection, the FDA approves a drug after determining that the drug’s benefits of use outweigh the risks for the condition that the drug will treat. However, even with the rigorous FDA evaluation process, safety problems can surface after a drug has been on the market and used in a broader population.

Boxed Warnings (formerly known as Black Box Warnings) are the highest safety-related warning that medications can have assigned by the FDA. These warnings are intended to bring the consumer’s attention to the major risks of the drug. Medications can have a boxed warning added, taken away, or updated throughout their tenure on the market. Boxed Warnings appear on a prescription drug’s label and in current, evidence-based drug references. For this reason, it is important for nurses to verify current drug information in drug references.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.3a

Critical Thinking Activity 2.3a

Levofloxacin is an antibiotic that received FDA approval. However, after the drug was on the market, it was discovered that some clients who took levofloxacin developed serious, irreversible adverse effects such as tendon rupture. The FDA issued a Boxed Warning with recommendations to reserve levofloxacin for use in clients who have no alternative treatment options for certain indications: uncomplicated UTI, acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, and acute bacterial sinusitis.[3]

A nurse is preparing to administer medications to a client and notices that levofloxacin has been prescribed for the indication of pneumonia. There is no other documentation in the provider’s notes related to the use of this medication.

What is the nurse’s best response?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA)

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) enforces the federal laws and regulations of controlled substances. This includes enforcement of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) that pertains to the manufacture, distribution, and dispensing of legally produced controlled substances that nurses administer to clients.[4]

Because controlled substances have a greater chance of being misused and abused, there are additional laws and procedures that must be followed when working with these medications. The DEA is responsible for enforcing these laws, and many federal laws are summarized in a document called the Pharmacist’s Manual. Most controlled substance laws, however, come from state governments. Health care professionals are responsible for following the most stringent of the two laws, whether it be state law or federal law.

View the DEA’s Pharmacist’s Manual PDF.

Examples of Federal and State Laws Regarding Controlled Substances

The following examples of federal laws are applicable to controlled substances administered by nurses:

- Prescriptions: A prescription for a controlled substance may be written only by a provider (physician or mid-level provider such as a nurse practitioner) who has a DEA registration number. The prescription for a Schedule II medication (i.e., opioids) must be written or electronically sent to the pharmacy through DEA approved software. Prescriptions over the phone or fax are not accepted. Refills for Schedule II medication are not allowed and require new prescriptions. Schedule III or IV medications may be refilled only five times. State law determines how long a written Schedule II prescription is valid and if there are any limits on the quantity of medication that can be dispensed. For example, in Wisconsin, a Schedule II prescription is only valid for 60 days after it is written.

- Records: There is a “closed system” for record keeping of controlled substances to prevent drug diversion. Hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies must maintain records on the whereabouts of controlled substances from the time the medication is received by the pharmacy, to when it is administered to the client, to disposal of wasted medication by the nurse. Inventory counts of controlled substances occur frequently and may require a physical count by two licensed staff at the start of each shift. Detailed documentation is required for administration of controlled substances. When a full dose of a controlled substance is not administered, this is referred to as waste. Waste is typically disposed of differently than other medications (i.e., flushed down the sink) and often requires the co-signature of a second licensed staff member.

View the Requirements for Controlled Substances PDF[5] with additional information about Wisconsin state laws regarding controlled substances.

Schedules of Drugs

The federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) categorizes drugs regulated under federal law into one of five schedules. This placement is based on the substance’s medical use, potential for abuse, and safety or dependence liability. Schedule I drugs have a high potential for abuse and the potential to create severe psychological and/or physical dependence, whereas Schedule V drugs represent the least potential for abuse. Sample medications for each schedule are summarized in Table 2.3.[6]

Table 2.3 Definitions and Sample Medications for Each Type of Scheduled Medication

Schedule |

Definition |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Schedule I | No currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. | Heroin, LSD, and marijuana |

| Schedule II | High potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous. | Vicodin, cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), meperidine (Demerol), oxycodone (OxyContin), fentanyl, Dexedrine, Adderall, and Ritalin |

| Schedule III | Moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Abuse potential is less than Schedule I and Schedule II drugs but more than Schedule IV. | Tylenol with codeine, ketamine, anabolic steroids, and testosterone |

| Schedule IV | Low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence. | Xanax, Soma, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien, and Tramadol |

| Schedule V | Lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. Generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes. | Robitussin AC with codeine, Lomotil, and Lyrica |

Read more information about Drug Scheduling on the DEA website and view an alphabetic listing of drugs and their schedule.[7],[8]

Drug overdose continues to be a public health crisis in the United States. The misuse of prescription opioids contributes to a large percentage of overdose deaths. Many problems associated with substance use are the result of legitimately made controlled substances being diverted from their lawful purpose into illicit drug traffic. The mission of DEA’s Diversion Control Division is to prevent, detect, and investigate the diversion of controlled medications from legitimate sources while ensuring an adequate and uninterrupted supply for legitimate medical, commercial, and scientific needs. The DEA provides education regarding related topics that apply to nurses such as drug diversion, state prescription drug monitoring systems, current drug trends, and proper drug disposal.[9]

Drug Diversion

Drug diversion involves the transfer of any legally prescribed controlled substance from the individual for whom it was prescribed to another person for any illicit use. The most commonly diverted substances in health care facilities are opioids. Diversion of controlled substances can result in substantial risk, not only to the individual who is diverting the drugs, but also to clients, coworkers, and employers. Impaired health professionals can harm clients by providing substandard care or exposing clients to tainted substances.

Tampering is the riskiest and most harmful type of diversion. Tampering occurs when the diverter removes medication from a syringe, vial, or other container and injects themselves with the medication. The diverter then replaces the stolen medication with saline, sterile water, or another clear liquid. The replaced liquid is then unknowingly administered to the client by an unaware nurse.[10],[11]

The DEA provides an online reporting form for individuals to report suspected drug diversion anonymously. [12]

View the RX Abuse Online Reporting form to report drug diversion to the DEA.[13]

Substance Use Disorder in Health Professionals

Substance use disorder (SUD) is an illness caused by repeated misuse of substances such as cannabis, opioids, sedatives, and stimulants. Substances taken in excess have a common effect of directly activating the brain reward system and producing such an intense activation of the reward system that normal life activities may be neglected.[14]

Health care professionals are not immune to developing SUD. It is important for nurses to be aware of the warning signs of SUD and to understand that SUD is a disease that can affect anyone regardless of age, occupation, economic circumstances, ethnic background, or gender. In most states, a nurse with SUD may voluntarily enter a professional assistance program for evaluation and treatment.[15] Read more about professional assistance programs under the “State Law, State Nurse Practice Acts, and State Boards of Nursing” subsection below.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) created A Nurse’s Guide to Substance Use Disorder in Nursing brochure that states many nurses with substance use disorder (SUD) are unidentified, unreported, untreated, and may continue to practice where their impairment may endanger the lives of their clients or themselves. It can be hard to differentiate between the subtle signs of impairment and stress-related behaviors, but three areas to watch for suspected SUD are behavior changes, physical signs, and drug diversion. Behavioral changes can include changes or shifts in job performance, absences from the unit for extended periods, frequent trips to the bathroom, arriving late or leaving early, and making an excessive number of mistakes, including medication errors. Physical signs include subtle changes in appearance that may escalate over time, increasing isolation from colleagues, inappropriate verbal or emotional responses, and diminished alertness, confusion, or memory lapses. When nurses with SUD commit drug diversion, there are often discrepancies that colleagues notice, such as incorrect opioid counts, a pattern of large amounts of opioid wastage, numerous corrections of medication records, frequent reports of ineffective pain relief from clients assigned to that nurse, increased agitation/combativeness of assigned clients with dementia, and patterns of increased administration of opioids to clients when that nurse is scheduled to work.[16]

As a student nurse and nurse, you have a professional and ethical responsibility to report a colleague’s suspected SUD to your supervisor and, in some states or jurisdictions, to the State Board of Nursing. The earlier that SUD is identified in a nurse and treatment is started, the sooner clients are protected, and the better the chances for the nurse with SUD to recover and safely return to work.[17]

Visit the NCSBN’s website to read “A Nurse’s Guide to Substance Use Disorder in Nursing” brochure.

Drug Disposal Act

The Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 allows users to dispose of controlled substances in a safe and effective manner. A Johns Hopkins study on sharing of medication found that 60% of people had leftover opioids they saved for future use; 20% shared their medications; 8% would likely share with a friend; 14% would likely share with a relative; and only 10% securely locked their medication.[18] This act has resulted in “National Take Back Days” in all 50 states, as well as new collection receptacles.[19]

To prevent risk of drug diversion, nurses should teach clients who are prescribed controlled substances how to dispose of them properly so that they don’t end up being misused or overdosed by another person. Figure 2.2[20] shows an example of a controlled substances collection receptacle.[21]

Critical Thinking Activity 2.3b

- A nurse is providing discharge education to a client who recently had surgery and has been prescribed hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets to take every four hours as needed at home. The nurse explains that when the medication is no longer needed when the post-op pain subsides, it should be dropped off at a local pharmacy for disposal in a collection receptacle. The client states, “I don’t like to throw anything away. I usually keep unused medication in case another family member needs it.”

What is the nurse’s best response? - A nurse begins a new job on a medical-surgical unit. One of the charge nurses on this unit is highly regarded by her colleagues and appears to provide excellent care to her clients. The new nurse cares for a client whom the charge nurse cared for on the previous shift. The new nurse asks the client about the effectiveness of the pain medication documented as provided by the charge nurse during the previous shift. The client states, “I didn’t receive any pain medication during the last shift.” The nurse mentions this incident to a preceptor who states, “I have noticed that the same types of incidents have occurred with previous clients but didn’t want to say anything.”

What is the new nurse’s best response?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

The Joint Commission

The Joint Commission is a national organization that accredits and certifies over 20,000 health care organizations in the United States. The mission of The Joint Commission is to continuously improve health care for the public by inspiring health care organizations to excel in providing safe and effective care of the highest quality and value.[22] Some of The Joint Commission’s national initiatives regarding medication safety include creating a “Safety Culture” in health care organizations with associated root cause analysis, the Speak Up Campaign, National Patient Safety Goals, and the Official Do not Use List. Each of these safety initiatives is further discussed in the following subsections.

Safety Culture

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare develops effective solutions for health care’s most critical safety and quality problems with a goal to ultimately achieve zero harm to clients. Some of the projects the Center has developed include improved hand hygiene,[23] effective handoff communications,[24] and safe and effective use of insulin.[25]

The Center has also been instrumental in building a focus on creating a “Safety Culture” in health care organizations. A Safety Culture empowers staff to speak up about risks to clients and to report errors and near misses. These actions reduce the risk of client harm. According to the Institute of Medicine, “The biggest challenge to moving toward a safer health system is changing the culture from one of blaming individuals for errors to one in which errors are treated not as personal failures, but as opportunities to improve the system and prevent harm.”[26]

Visit the Joint Commission’s Safety Culture Assessment webpage to learn more.

A component of Safety Culture is the submission of incident reports according to agency guidelines whenever a medication error or a “near miss” occurs. A near miss is a narrowly avoided error. The incident report triggers a root cause analysis by the organization to identify not only what and how an event occurred, but also why it happened. When investigators determine why an error occurred, they can create workable corrective measures to prevent future errors from occurring.[27]

An example of Safety Culture in action is a tragic event in 2006, when three infants died after incorrect heparin doses were used to flush their vascular access devices. A root cause analysis found that pharmacy technicians accidentally placed vials containing concentrated heparin (10,000 units/mL) in medication storage locations that were designated for less concentrated heparin vials (10 units/mL). Additionally, the heparin vials were similar in appearance, so the nurses did not notice the incorrect dosage until after it was administered. In response to a root cause analysis, the hospital no longer stores vials of heparin in pediatric units and uses saline to flush all peripheral lines. In the pharmacy, 10,000 units/mL heparin vials were separated from vials containing other strengths. In this manner, corrective measures were implemented to prevent future tragedies from occurring as a result of incorrect doses of heparin.[28]

Speak Up Campaign

The goal of The Joint Commission’s Speak Up™ campaign is to help clients become more informed and involved in their health care to prevent medication errors. Speak Up™ materials are intended for the public and have been put into a simplified, easy-to-read format to reach a wider audience.[29]

Request additional “SpeakUp” materials from The Joint Commission Speak Up Fact Sheet webpage.

National Patient Safety Goals

The National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) are established by The Joint Commission to help accredited organizations address current areas of concern related to patient safety. Annually, The Joint Commission determines the current highest priority patient safety issues with input from practitioners, provider organizations, purchasers, consumer groups, and other stakeholders and develops National Patient Safety Goals.

Two of the current National Patient Safety Goals relate specifically to medication administration: “Identify Patients Correctly” and “Use Medicines Safely.”

Review The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals for Hospitals PDF[30]

Identify Patients Correctly

Nurses and health care professionals must use at least two ways to identify clients. For example, use the client’s name and date of birth. This is done to make sure that each client gets the correct medicine and treatment.[31]

Use Medicines Safely

Before a procedure, label medications that are not labeled. For example, medications in syringes, cups, and basins should be labelled in the area where medications and supplies are set up. Labels should include medication name, dose, date drawn up, and initials of the person who prepared the medication.[32] Additionally, do not leave medications unattended.

Record and pass along correct information about a client’s medications. Find out what medications the client is taking. Compare those medications to new medications given to the client. Make sure the client knows which medications to take when they are at home. Tell the client it is important to bring their up-to-date list of medications every time they visit a doctor. Extra care must be taken with clients who take medications to thin their blood (anticoagulants).[33]

The Joint Commission’s Official Do Not Use List

The Joint Commission maintains an Official Do Not Use List of abbreviations. These abbreviations have been found to commonly cause errors in client care. Accredited agencies are expected to not use these abbreviations on any written or preprinted materials.[34]

Read The Joint Commission’s Official Do Not Use List Fact Sheet

CMS: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is a federal agency within the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The CMS administers the Medicare program and works in partnership with state governments to administer Medicaid and establishes and enforces regulations to protect client safety in hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding.[35]

CMS regulations related to the administration of medication by nurses include verifying information included in the prescription for a medication, checking the rights of medication administration, reporting concerns about a medication prescription, assessing and monitoring clients receiving medications, and documenting medication administration. Each of these regulations is further discussed below.

Verifying Prescriptions

Medications and biologicals are administered in response to a prescription from a health care provider or on the basis of a standing order that is subsequently authenticated by a provider. Biologicals are a diverse group of medications that include vaccines, growth factors, immune modulators, monoclonal antibodies, and products derived from blood and plasma. All provider orders for the administration of drugs and biologicals must include the following:

- Name of the client

- Age and weight of the client to facilitate dose calculation when applicable. Agency policies and procedures must address weight-based dosing for pediatric client. Dose calculations for newborns are typically based on the metric weight in grams.

- Date and time of the order

- Drug name

- Dose, frequency, and route

- Dose calculation requirements, when applicable

- Exact strength or concentration, when applicable

- Quantity and/or duration, when applicable

- Specific instructions for use, when applicable

- Name of the provider

Checking The Rights of Medication Administration

The CMS states that agency policies and procedures must reflect accepted standards of practice that require specific information is confirmed prior to administration of medication. This is commonly referred to as “checking the rights of medication administration.”

When administering medications, it is essential for nurses to vigilantly check the rights of medication administration at least three times to prevent medication errors. What historically began as checking five rights of mediation administration has been extended to eight rights according to the American Nurses Association. These eight rights include the following[36]:

- Right patient: Check that you have the correct client using two patient identifiers according to agency policy (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Right medication: Check that you have the correct medication and that it is appropriate for the patent in the current context. Understand the purpose of the medication and why the client is receiving it.

- Right dose: Check that the dose is safe for the age, size, and condition of the client. Different dosages may be indicated for different conditions, and pediatric dosages are typically much lower than adult dosages.

- Right route: Check that the route is appropriate for the client’s current condition.

- Right time: Adhere to the prescribed scheduling of the medication.

- Right documentation: Always verify any unclear or inaccurate documentation prior to administering medications.

- Right reason: Verify this medication is being administered to this client at this time for the right reason. If signs and symptoms no longer warrant administration of the prescribed medication, notify the prescribing provider.

- Right response: After administering medication, the nurse must evaluate for expected outcomes with the time frame of expected onset and peak. The onset of medication administration occurs when the action of the medication begins to take effect. The peak of the medication administration occurs when the medication is at the highest level in the client’s bloodstream. It is important for nurses to be aware of both the peak and onset of medications to know when the client’s response to medication may start to be observed. The nurse must also be aware of potential side effects and adverse effects and evaluate for these unexpected outcomes. The prescribing provider should be notified if expected outcomes are not achieved or if adverse effects occur.

Many agencies have implemented barcode medication scanning to improve safety during medication administration. Barcode scanning systems reduce medication errors by electronically verifying the “rights” of medication administration. For example, when a nurse scans a barcode on the client’s wristband and on the medication to be administered, the data is delivered to a computer software system where algorithms check databases and generate real-time warnings or approvals. Barcode scanning reduces errors resulting from administration of a wrong medication, incorrect dose, or wrong route. However, it is important for nurses to remember that barcode scanning should be used in addition to checking the rights of medication administration, not in place of this important safety process. Additionally, nurses should carefully consider their actions when errors occur during the barcode scanning process. Although it may be tempting to quickly dismiss the error and attribute it to a technology glitch, the error may have been triggered due to a patient safety concern that requires further follow-up before the medication is administered. Nurses must investigate errors that occur during the barcode scanning process just as they would do if an error were discovered while checking the rights of medication administration.

View a YouTube video[37] example of a student preparing to administer medication and checking the rights of medication administration: Medication Administration.

Communicating Concerns About Medication Orders

The CMS encourages hospitals to promote a culture in which it is not only acceptable, but also strongly encouraged, for staff to notify prescribing providers regarding concerns they have regarding medication orders.[38] It is essential for nurses to contact the prescribing provider if they have any concerns when checking the rights of medication administration before administering the medication to the client. Furthermore, nurses can be held liable in a court of law if they administer medication that results in client harm if a “prudent nurse” would have had concerns about the order and questioned it.

Monitoring Clients Receiving Medications

The CMS states that observing the effects medications have on the client is part of the multifaceted medication administration process. Clients must be carefully monitored to determine whether the medication results in the therapeutically intended benefit and to allow for early identification of adverse effects and timely initiation of appropriate corrective action. Depending on the medication and route/delivery mode, monitoring may include assessment of the following:

- Clinical and laboratory data to evaluate the efficacy of medication therapy, potential toxicity, and adverse effects. For some medications, such as opioids, this monitoring may include clinical data such as respiratory status, blood pressure, and oxygenation and carbon dioxide levels.

- Physical signs and clinical symptoms relevant to the client’s medication therapy, such as confusion, agitation, unsteady gait, pruritus, etc.

- Factors contributing to high risk for adverse drug events. The consequences of errors can be harmful and sometimes fatal to clients. In addition, certain factors place some clients at greater risk for adverse effects of medication. These factors include, but are not limited to, age, altered liver and kidney function, drug-to-drug interactions, and first-time medication use.

The nurse should consider client risk factors, as well as the risks inherent in a medication, when determining the type and frequency of monitoring. It is also essential to communicate information regarding client medication risk factors and monitoring requirements during hand-off reports to other staff.

Adverse client reactions, such as anaphylaxis or opioid-induced sedation and respiratory depression, require timely and appropriate intervention per agency protocols and should also be immediately reported to the prescribing provider. An example of vigilant post-medication administration monitoring is when a nurse closely monitors a post-surgical client who is receiving opioid pain medication via a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump. Opioid medications are used to control pain but also have a sedating effect. Clients can become overly sedated and suffer respiratory depression or arrest, which can be fatal. The nurse should closely monitor the client’s respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, carbon dioxide levels, level of sedation, blood pressure, and pulse to quickly observe and intervene in the event of an adverse event. In addition, the client and/or family members are educated to notify nursing staff promptly when there is difficulty breathing or other changes that might be a reaction to medication.[39]

Documenting

CMS regulations require the agency’s documentation regarding medication administration contains providers’ orders, nursing notes, reports of treatment, medication administration records, radiology and laboratory reports, vital signs, and other information necessary to monitor the client’s condition. Documentation of medication administration is expected to occur immediately after the medication is administered to the client; documenting prior to the administration of the medication is inappropriate and can result in medication errors. Proper documentation of medication administration and client outcomes is essential for planning and delivering future care of the client.[40],[41]

Critical Thinking Activity 2.3c

A nurse is preparing to administer morphine, an opioid, to a client who recently had surgery.

- Explain the rights of medication administration the nurse must check prior to administering this medication to the client.

- Outline three methods the nurse can use to confirm patient identification.

- What should the nurse assess prior to administering this medication to the client?

- What should be monitored after administering this medication?

- What should the nurse teach the client (and/or family member) about this medication?

- What information should be included in the shift handoff report about this medication?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

State Law, State Nurse Practice Acts, and State Boards of Nursing

Nurses are responsible for knowing the state laws that relate to nursing care in the state in which they work. Furthermore, nurses must follow the scope of practice outlined in the NPA in the state in which they are employed. Nurses are accountable for the quality of care they provide and are expected to practice at the level of education, knowledge, and skill of someone who has completed an approved nursing program.

Nurse Practice Act: Standards of Practice

The NPA outlines the standards of care provided by a registered nurse (RN), also known as the nursing process. As previously discussed in this chapter, the steps of the nursing process are also considered a standard of care by the ANA. A nurse utilizes the nursing process when executing nursing care and procedures in the maintenance of clients’ health, prevention of illness, or care of the ill. Review the steps of the nursing process in the “Ethical and Professional Foundations of Safe Medication Administration by Nurses” section of this chapter.

Nurse Practice Act: Rules of Conduct

The NPA also outlines rules of conduct expected of nurses. Nurses can receive disciplinary action from the SBON, ranging from a reprimand to revocation of their license, if they do not follow the enacted rules of conduct. A nurse must maintain current knowledge about expected rules of conduct in each state where they practice nursing to protect their nursing license.

A SBON may take disciplinary action against a nurse’s license for many reasons. Common reasons related to medication administration include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Noncompliance with federal, jurisdictional, or reporting requirements, including practicing beyond the scope of practice.

- Confidentiality, client privacy, consent, or disclosure violations.

- Fraud, deception or misrepresentation, including falsification of client documentation.

- Unsafe practice or substandard care, including:

- Failing to perform nursing care with reasonable skill and safety.

- Departing from or failing to conform to the minimal standards of acceptable nursing practice that may create unnecessary risk or danger to a client’s life, health, or safety. Actual injury to a client does not need to be established.

- Failing to report to or leaving a nursing assignment without properly notifying appropriate supervisory personnel and ensuring the safety and welfare of the client.

- Practicing nursing while under the influence of alcohol, illicit drugs, or while impaired by the use of legitimately prescribed pharmacological agents or medications.

- Inability to practice safely due to alcohol or other substance use, psychological or physical illness, or impairment.

- Executing an order which the licensee knew or should have known could harm a client.

- Improper supervision.

- Improper prescribing, dispensing, or administering medication or drug-related offenses.[42]

State Statutes Related to Controlled Substances

In addition to the NPA, there are other state statutes that guide nursing care and medication administration. State statutes are a compilation of the general laws of the state and often include chapters related to the state regulation of controlled substances (in addition to federal law previously discussed in this section).

Prescription Drug Monitoring Program

Examples of state law related to controlled substances are prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP). Many states have implemented PDMP to help combat the ongoing prescription substance abuse epidemic, as well as to help prevent drug diversion. Pharmacies and health care providers are often required by state law to participate in a PDMP when dispensing or prescribing controlled substances. A PDMP is a statewide electronic database that collects data on substances dispensed in the state. By providing valuable information about controlled substance prescriptions that are dispensed in the state, PDMPs help health care providers make prescribing and dispensing decisions. PDMPs also foster the ability of pharmacies, health care professionals, law enforcement agencies, and public health officials to work together to reduce the misuse, abuse, and diversion of prescribed controlled substances.

Professional Assistance Programs

In addition to state statutes related to controlled substances, many states offer professional assistance programs as voluntary, nondisciplinary programs to provide support for health professionals with substance abuse disorders (SUD) who are committed to their own recovery. The goal of professional assistance programs is to protect the public by promoting early identification of professionals with SUD and encouraging their rehabilitation and recovery. Professional assistance programs provide an opportunity for nurses with SUD to continue to be employed while being monitored by the SBON and supported in their recovery.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.3d

A nurse is disciplined by the Wisconsin Board of Nursing for an incident reported by her employer that she arrived at her shift intoxicated. The nurse shares with a nursing colleague, “I love taking care of patients. I worked so hard to obtain my nursing license – I don’t want to lose it. I know my drinking has gotten out of control, but I don’t know where to turn.”

What is the best advice by the nursing colleague for this nurse with a drinking problem?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d). https://www.fda.gov ↵

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Developing new drugs. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs ↵

- This work is a derivative of DailyMed by U.S. National Library of Medicine in the Public Domain. ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). Drug scheduling. https://www.dea.gov/drug-scheduling ↵

- Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2022). Uniform Controlled Substances Act. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/phar/8.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). Drug scheduling. https://www.dea.gov/drug-scheduling ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). Drug scheduling. https://www.dea.gov/drug-scheduling ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (2023). Controlled substances. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/orangebook/c_cs_alpha.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (2023). Controlled substances. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/orangebook/c_cs_alpha.pdf ↵

- New, K. (2014, June 3). Drug diversion defined: A patient safety threat. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://web.archive.org/web/20150716073835/http://blogs.cdc.gov/safehealthcare/2014/06/03/drug-diversion-defined-a-patient-safety-threat/ ↵

- Berge, K. H., Dillon, K. R., Sikkink, K. M., Taylor, T. K., & Lanier, W. L. (2012). Diversion of drugs within health care facilities, a multiple-victim crime: Patterns of diversion, scope, consequences, detection, and prevention. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 87(7), 674–682. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22766087 ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/prog_dscrpt/index.html ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). RX abuse online reporting: Report incident. https://apps2.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/rxaor/spring/main?execution=e1s1 ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). (2018). A nurse's guide to substance use disorder in nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). (2018). A nurse's guide to substance use disorder in nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). (2018). A nurse's guide to substance use disorder in nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (2017, December 13). Federal regulations and the disposal of controlled substances. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/mtgs/drug_chemical/2017/wingert.pdf#search=drug%20disposal ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (2017, December 13). Federal regulations and the disposal of controlled substances. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/mtgs/drug_chemical/2017/wingert.pdf#search=drug%20disposal ↵

- “MedRx box.JPG” by York Police is licensed under CC0 ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice - Drug Enforcement Administration. (2017, December 13). Federal regulations and the disposal of controlled substances. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/mtgs/drug_chemical/2017/wingert.pdf#search=drug%20disposal ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). https://www.jointcommission.org/ ↵

- Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. (2020). Hand hygiene. https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/improvement-topics/hand-hygiene ↵

- Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. (2020.) Effective hand-off communications. https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/improvement-topics/hand-off-communications ↵

- Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. (2020). Safe and effective use of insulin. https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/improvement-topics/safe-and-effective-use-of-insulin ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2014, November). Facts about the safety culture project. https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/-/media/cth/documents/improvement-topics/cth_sc_fact_sheet.pdf ↵

- Patient Safety Network. (2019). Root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/root-cause-analysis ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2007, November 29). Another heparin error: Learning from mistakes so we don't repeat them. https://www.ismp.org/resources/another-heparin-error-learning-mistakes-so-we-dont-repeat-them ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Speak up campaigns. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/for-consumers/speak-up-campaigns/#sort=%40z95xz95xcontentdate%20descending ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2023). 2023 hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2019_HAP_NPSGs_final2.pdf ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2023). 2023 hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2019_HAP_NPSGs_final2.pdf ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2023). 2023 hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2019_HAP_NPSGs_final2.pdf ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2023). 2023 hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2019_HAP_NPSGs_final2.pdf ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2023). Do not use list fact sheet. https://www.jointcommission.org/facts_about_do_not_use_list/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). ANA issue brief: Use of medication assistants/aides/technicians. https://www.nursingworld.org/~498e32/contentassets/a2ff1bd2d5ca467699c3bc764f7d9198/issue-brief-medication-aides-4-2021.docx ↵

- Kimberly Dunker. (2020, April 6). Mediation Administration. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/MUn4Ec2X93g ↵

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (Ed.). (2018). ASHP guidelines on preventing medication errors in hospitals. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 75, 1493–1517. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/guidelines/preventing-medication-errors-hospitals.ashx ↵

- Wisconsin Department of Safety and Professional Services. (n.d.). Wisconsin nurse practice act (NPA) course. https://dsps.wi.gov/Documents/BoardCouncils/NUR/20190110NURAdditionalMaterials.pdf ↵

Authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.

Spiritual Distress

When clients are initially diagnosed with an illness or experience a serious injury, they often grapple with the existential question, “Why is this happening to me?” This question is often a sign of spiritual distress. Spiritual distress is defined by NANDA-I as, “A state of suffering related to the inability to experience meaning in life through connections with self, others, the world, or a superior being.”[1] Nurses can help relieve this suffering by therapeutically responding to a client's signs of spiritual distress and advocating for their spiritual needs throughout their health care experience.

Spirituality

Provision 1 of the ANA Code of Ethics states, “The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person” and “optimal nursing care enables the client to live with as much physical, emotional, social, and religious or spiritual well-being as possible and reflects the client’s own values.”[2]

Spiritual well-being is a pattern of experiencing and integrating meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, and/or a power greater than oneself.[3] Spirituality is defined by the Interprofessional Spiritual Care Education Curriculum (ISPEC) as, “A dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred.”[4] Spiritual needs and spirituality are often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept. Elements of spirituality include faith, meaning, love, belonging, forgiveness, and connectedness.[5] Spirituality and spiritual values in the context of nursing are closely intertwined with the concept of caring.[6] See Figure 18.1[7] for an illustration of the concept of spirituality.

An integrative review of nursing research and resources was completed in 2014 to describe the impact of spirituality and spiritual support in nursing.[8] See the following box for discussion of findings from this integrative review.

Integrative Review of Spirituality in Nursing[9]

An integrative review of nursing literature selected 26 articles published between 1999 and 2013 to describe the experiences of spirituality and the positive impact of spiritual support in nursing literature.[10] Spirituality was described as the integration of body, mind, and spirit into a harmonious whole (often referred to as holistic care). Spirituality was associated with the development of inner strength, looking into one’s own soul, believing there is more to life than worldly affairs, and trying to understand who we are and why we are on this earth.

Transcendence was described as an understanding of being part of a greater picture or of something greater than oneself, such as the awe one can experience when walking in nature. It was also expressed as a search for the sacred through subjective feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Spirituality was found to have a positive effect on clients’ health and promoted recovery by viewing life from different perspectives and looking beyond one’s own anxiety to develop an understanding of illness and change.

Relationships and connectedness were also found to be powerful spiritual interventions that contributed to an individual’s spirituality. This included embracing, crying together, gift giving, having coffee together, and visiting each other. Laughter, happy thoughts, and the smiles of others were considered comforting. Being with others was described as a primary spiritual need, and conversation was unnecessary. Spirituality brought about the realization that the relationship with family and friends is important and involves finding a healthy balance in relationships among friends, family, society, and a higher power. Presence was the most influential element in positively influencing recovery. The presence of family and friends was a calming experience that brought forth comfort, peace, happiness, joy, acceptance, and hope.

Nurses facilitate their clients’ search for meaning by enabling them to express personal beliefs, as well as by supporting them in taking part in their religious and cultural practices. Furthermore, nurses assess and meet their clients’ spiritual needs by using active listening when talking, asking questions, and picking up client cues. Active listening requires nurses to be fully present, especially when clients appear depressed or upset.

Nurses were found to use their own spirituality when helping clients achieve spiritual well-being. A desire to help others in need is an important part of spirituality, which is also described as discovering meaning and purpose in life and offering the gift of self to others. Helping others also brings a sense of self-worth, personal fulfilment, and satisfaction.

Spiritual Assessment

The Joint Commission requires that health care organizations provide a spiritual assessment when clients are admitted to a hospital. Spiritual assessment can include questions such as the following:

- Who or what provides you with strength or hope?

- How do you express your spirituality?

- What spiritual needs can we advocate for you during this health care experience?

In addition to performing a routine spiritual assessment on admission, nurses often notice other cues related to a client’s spiritual distress or desire to enhance their spiritual well-being. When these cues are identified, spiritual care should be provided to relieve suffering and promote spiritual health. There are several nursing interventions that can be implemented, in addition to contacting the health care agency’s chaplain or the client’s clergy member. See the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of this chapter for a discussion of spiritual assessment tools and nursing interventions related to spiritual care.

Many hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and hospices employ professionally trained chaplains to assist with the spiritual, religious, and emotional needs of clients, family members, and staff. In these settings, chaplains support and encourage people of all religious faiths and cultures and customize their approach to each individual’s background, age, and medical condition. Chaplains can meet with any individual regardless of their belief, or lack of belief, in a higher power and can be very helpful in reducing anxiety and distress. A nurse can make a referral for a chaplain without a provider order. See Figure 18.2[11] for an image of a hospital chaplain offering support to a client.

A chaplain assists clients and their family members to develop a spiritual view of their serious illness, injury, or death, which promotes coping and healing. A spiritual view of life and death includes elements such as the following:

-

- Suffering occurs at physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual levels. Sociocultural factors, religious beliefs, family values and dynamics, and other environmental factors affect a person’s response to suffering.

- Hope is a desire or goal for a particular event or outcome. For example, some people may view dying as “hopeless” whereas a spiritual view can define hope as a “good death” when the client dies peacefully according to the end-of-life preferences they previously expressed. Read more about the concept of a “good death” in the "Grief and Loss" chapter.

- Mystery is knowing there is truth beyond understanding and explanation.

- Peacemaking is the creation of a space for nurturing and healing.

- Forgiveness is an internal process releasing intense emotions attached to past incidents. Self-forgiveness is essential to spiritual growth and healing.

- Prayer is an expression of one's spirituality through a personalized interaction or organized form of petitioning and worship.

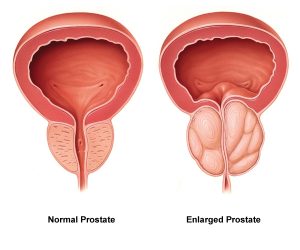

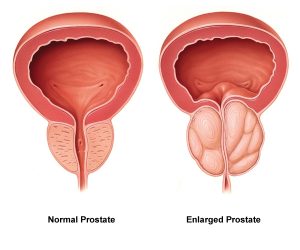

Urinary retention is a condition when the client cannot empty all of the urine from their bladder. Urinary retention can be acute (i.e., the sudden inability to urinate after receiving anesthesia during surgery) or chronic (i.e., a gradual inability to completely empty the bladder due to enlargement of the prostate gland in males). Urinary retention is caused by a blockage that partially or fully prevents the flow of urine or the bladder not being able to create a strong enough force to expel all the urine. In addition to causing discomfort, urinary retention increases the client's risk for developing a urinary tract infection (UTI) because bacteria from the urethra can move up toward the bladder and multiply in retained urine. See Figure 16.5[16] for an image of an enlarged prostate gland blocking the flow of urine from the bladder into the urethra.

Symptoms of urinary retention can range from none to severe abdominal pain.[17] Health care providers use a client’s medical history, physical exam finding, and diagnostic tests to find the cause of urinary retention. Nurses typically receive orders to measure post-void residual amounts when urinary retention is suspected. Post-void residual measurements are taken after a client has voided by using a bladder scanner or inserting a straight urinary catheter to determine how much urine is left in the bladder. See the following box regarding how to perform a bladder scan at the bedside. Read about other diagnostic tests related to urinary retention, such as urodynamic testing and cystoscopy, under the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of this chapter.[18]

Performing a Bladder Scan

A bladder scanner is a portable, noninvasive medical device that uses sound waves to calculate the amount of urine in a client’s bladder. Nurses use bladder scanners at the bedside to determine post-void residual urine amounts in clients to avoid the need to perform an invasive urinary catheterization. Typically, the use of a bladder scan does not require a physician order but be sure to check agency policy.

After the client voids and is lying in a supine position, turn on the device and indicate if the client is male or female. (If the female has had a hysterectomy, then “male” is selected.) Apply warmed gel to the transducer head, and then place it approximately one inch above the symphysis pubis with the probe directed towards the bladder. Press the "scan" button, making sure to hold the scanner steady until you hear a beep. The bladder scanner will display the volume measured using a display with crosshairs. If the crosshairs are not centered on the urine displayed, adjust the probe and rescan until it is properly centered. If the post-void residual is greater than 300 mL, the provider should be notified and typically an order will be received for a straight urinary catheterization. Whenever possible, indwelling urinary catheterization is avoided to reduce the client’s risk of developing a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).[19]

View this following YouTube video to see a bladder scanner in use[20]: How to Use BladderScan Prime Plus™ by Diane Newman

Interventions

Treatment for urinary retention depends on the cause. It may include urinary catheterization to drain the bladder, bladder training therapy, medications, or surgery.[21] Read more about bladder training therapy under the “Urinary Incontinence” section. Alpha blockers, such as tamsulosin (Flomax), are used to treat urinary retention caused by an enlarged prostate. A surgery called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) may be performed to treat urinary retention caused by an enlarged prostate that is not responsive to medication.

Read more about alpha-blocker medication (i.e., tamsulosin) in the “Autonomic Nervous System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Urinary retention is a condition when the client cannot empty all of the urine from their bladder. Urinary retention can be acute (i.e., the sudden inability to urinate after receiving anesthesia during surgery) or chronic (i.e., a gradual inability to completely empty the bladder due to enlargement of the prostate gland in males). Urinary retention is caused by a blockage that partially or fully prevents the flow of urine or the bladder not being able to create a strong enough force to expel all the urine. In addition to causing discomfort, urinary retention increases the client's risk for developing a urinary tract infection (UTI) because bacteria from the urethra can move up toward the bladder and multiply in retained urine. See Figure 16.5[22] for an image of an enlarged prostate gland blocking the flow of urine from the bladder into the urethra.

Symptoms of urinary retention can range from none to severe abdominal pain.[23] Health care providers use a client’s medical history, physical exam finding, and diagnostic tests to find the cause of urinary retention. Nurses typically receive orders to measure post-void residual amounts when urinary retention is suspected. Post-void residual measurements are taken after a client has voided by using a bladder scanner or inserting a straight urinary catheter to determine how much urine is left in the bladder. See the following box regarding how to perform a bladder scan at the bedside. Read about other diagnostic tests related to urinary retention, such as urodynamic testing and cystoscopy, under the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of this chapter.[24]

Performing a Bladder Scan

A bladder scanner is a portable, noninvasive medical device that uses sound waves to calculate the amount of urine in a client’s bladder. Nurses use bladder scanners at the bedside to determine post-void residual urine amounts in clients to avoid the need to perform an invasive urinary catheterization. Typically, the use of a bladder scan does not require a physician order but be sure to check agency policy.

After the client voids and is lying in a supine position, turn on the device and indicate if the client is male or female. (If the female has had a hysterectomy, then “male” is selected.) Apply warmed gel to the transducer head, and then place it approximately one inch above the symphysis pubis with the probe directed towards the bladder. Press the "scan" button, making sure to hold the scanner steady until you hear a beep. The bladder scanner will display the volume measured using a display with crosshairs. If the crosshairs are not centered on the urine displayed, adjust the probe and rescan until it is properly centered. If the post-void residual is greater than 300 mL, the provider should be notified and typically an order will be received for a straight urinary catheterization. Whenever possible, indwelling urinary catheterization is avoided to reduce the client’s risk of developing a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).[25]

View this following YouTube video to see a bladder scanner in use[26]: How to Use BladderScan Prime Plus™ by Diane Newman

Interventions

Treatment for urinary retention depends on the cause. It may include urinary catheterization to drain the bladder, bladder training therapy, medications, or surgery.[27] Read more about bladder training therapy under the “Urinary Incontinence” section. Alpha blockers, such as tamsulosin (Flomax), are used to treat urinary retention caused by an enlarged prostate. A surgery called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) may be performed to treat urinary retention caused by an enlarged prostate that is not responsive to medication.

Read more about alpha-blocker medication (i.e., tamsulosin) in the “Autonomic Nervous System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Spiritual Distress

When clients are initially diagnosed with an illness or experience a serious injury, they often grapple with the existential question, “Why is this happening to me?” This question is often a sign of spiritual distress. Spiritual distress is defined by NANDA-I as, “A state of suffering related to the inability to experience meaning in life through connections with self, others, the world, or a superior being.”[28] Nurses can help relieve this suffering by therapeutically responding to a client's signs of spiritual distress and advocating for their spiritual needs throughout their health care experience.

Spirituality

Provision 1 of the ANA Code of Ethics states, “The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person” and “optimal nursing care enables the client to live with as much physical, emotional, social, and religious or spiritual well-being as possible and reflects the client’s own values.”[29]

Spiritual well-being is a pattern of experiencing and integrating meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, and/or a power greater than oneself.[30] Spirituality is defined by the Interprofessional Spiritual Care Education Curriculum (ISPEC) as, “A dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred.”[31] Spiritual needs and spirituality are often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept. Elements of spirituality include faith, meaning, love, belonging, forgiveness, and connectedness.[32] Spirituality and spiritual values in the context of nursing are closely intertwined with the concept of caring.[33] See Figure 18.1[34] for an illustration of the concept of spirituality.

An integrative review of nursing research and resources was completed in 2014 to describe the impact of spirituality and spiritual support in nursing.[35] See the following box for discussion of findings from this integrative review.

Integrative Review of Spirituality in Nursing[36]

An integrative review of nursing literature selected 26 articles published between 1999 and 2013 to describe the experiences of spirituality and the positive impact of spiritual support in nursing literature.[37] Spirituality was described as the integration of body, mind, and spirit into a harmonious whole (often referred to as holistic care). Spirituality was associated with the development of inner strength, looking into one’s own soul, believing there is more to life than worldly affairs, and trying to understand who we are and why we are on this earth.

Transcendence was described as an understanding of being part of a greater picture or of something greater than oneself, such as the awe one can experience when walking in nature. It was also expressed as a search for the sacred through subjective feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Spirituality was found to have a positive effect on clients’ health and promoted recovery by viewing life from different perspectives and looking beyond one’s own anxiety to develop an understanding of illness and change.

Relationships and connectedness were also found to be powerful spiritual interventions that contributed to an individual’s spirituality. This included embracing, crying together, gift giving, having coffee together, and visiting each other. Laughter, happy thoughts, and the smiles of others were considered comforting. Being with others was described as a primary spiritual need, and conversation was unnecessary. Spirituality brought about the realization that the relationship with family and friends is important and involves finding a healthy balance in relationships among friends, family, society, and a higher power. Presence was the most influential element in positively influencing recovery. The presence of family and friends was a calming experience that brought forth comfort, peace, happiness, joy, acceptance, and hope.

Nurses facilitate their clients’ search for meaning by enabling them to express personal beliefs, as well as by supporting them in taking part in their religious and cultural practices. Furthermore, nurses assess and meet their clients’ spiritual needs by using active listening when talking, asking questions, and picking up client cues. Active listening requires nurses to be fully present, especially when clients appear depressed or upset.

Nurses were found to use their own spirituality when helping clients achieve spiritual well-being. A desire to help others in need is an important part of spirituality, which is also described as discovering meaning and purpose in life and offering the gift of self to others. Helping others also brings a sense of self-worth, personal fulfilment, and satisfaction.

Spiritual Assessment

The Joint Commission requires that health care organizations provide a spiritual assessment when clients are admitted to a hospital. Spiritual assessment can include questions such as the following:

- Who or what provides you with strength or hope?

- How do you express your spirituality?

- What spiritual needs can we advocate for you during this health care experience?

In addition to performing a routine spiritual assessment on admission, nurses often notice other cues related to a client’s spiritual distress or desire to enhance their spiritual well-being. When these cues are identified, spiritual care should be provided to relieve suffering and promote spiritual health. There are several nursing interventions that can be implemented, in addition to contacting the health care agency’s chaplain or the client’s clergy member. See the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of this chapter for a discussion of spiritual assessment tools and nursing interventions related to spiritual care.

Many hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and hospices employ professionally trained chaplains to assist with the spiritual, religious, and emotional needs of clients, family members, and staff. In these settings, chaplains support and encourage people of all religious faiths and cultures and customize their approach to each individual’s background, age, and medical condition. Chaplains can meet with any individual regardless of their belief, or lack of belief, in a higher power and can be very helpful in reducing anxiety and distress. A nurse can make a referral for a chaplain without a provider order. See Figure 18.2[38] for an image of a hospital chaplain offering support to a client.

A chaplain assists clients and their family members to develop a spiritual view of their serious illness, injury, or death, which promotes coping and healing. A spiritual view of life and death includes elements such as the following:

-

- Suffering occurs at physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual levels. Sociocultural factors, religious beliefs, family values and dynamics, and other environmental factors affect a person’s response to suffering.

- Hope is a desire or goal for a particular event or outcome. For example, some people may view dying as “hopeless” whereas a spiritual view can define hope as a “good death” when the client dies peacefully according to the end-of-life preferences they previously expressed. Read more about the concept of a “good death” in the "Grief and Loss" chapter.

- Mystery is knowing there is truth beyond understanding and explanation.

- Peacemaking is the creation of a space for nurturing and healing.

- Forgiveness is an internal process releasing intense emotions attached to past incidents. Self-forgiveness is essential to spiritual growth and healing.

- Prayer is an expression of one's spirituality through a personalized interaction or organized form of petitioning and worship.