17.2 Ethical and Professional Foundations of Safe Medication Administration by Nurses

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

The American Nurses Association (ANA) is a professional organization that represents the interests of the nation’s four million registered nurses and is at the forefront of improving the quality of health care for all.[1] The ANA establishes ethical and professional standards for nurses that also guide safe administration of medications. These code of ethics and professional standards are described in ANA publications titled Code of Ethics for Nurses and Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice.

Code of Ethics for Nurses

The ANA developed the Code of Ethics for Nurses as a guide for carrying out nursing responsibilities in a manner consistent with quality in nursing care and the ethical obligations of the profession.[2] Several provisions from the Code of Ethics impact how nurses should administer medication in an ethical manner. A summary of each provision from the Code of Ethics and how it pertains to medication administration is outlined below:

- Provision 1 focuses on respect for human dignity and the right for self-determination: “The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.”

- Provision 2 states, “The nurse’s primary commitment is to the client…”[3] In health care settings, nurses often experience several competing loyalties, such as to their employer, to the doctor(s), to their supervisor, or to others on the health care team. However, the client should always receive the primary commitment of the nurse. Additionally, the client has the right to accept, refuse, or terminate any treatment, including medications.

- Provision 3 states, “The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient…”[4] This provision includes a nurse’s responsibility to promote a culture of safety for clients. If errors occur, they must be reported, and nurses should ensure responsible disclosure of errors to clients. This also includes proper disclosure of questionable practices, such as drug diversion or impaired practice by any professional.

- Provision 4 involves authority, accountability, and responsibility by a nurse to follow legal requirements, such as state practice acts and professional standards of care.

- Provision 5 includes the responsibility of the nurse to promote health and safety.

- Provision 6 focuses on virtues that make a nurse a morally good person. For example, nurses are held accountable to use their clinical judgment to avoid causing harm to clients (maleficence) and to do good (beneficence). When administering medications, nurses should validate the medication is doing more “good” than “harm” (adverse or side effects).

- Provision 7 focuses on a nurse practicing within the professional standards set forth by their state nurse practice act, as well as standards established by professional nursing organizations.

- Provision 8 explains that a nurse must address the social determinants of health, such as poverty, education, safe medication, and health care disparities.[5]

Whenever a nurse provides client care, the ANA’s Code of Ethics should be used as a guide for professional ethical behavior.

View the ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.2a

A nurse is preparing to administer medications to a client. While reviewing the chart, the nurse notices two medications with similar mechanisms of action have been prescribed by two different providers.

What is the nurse’s best response?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

Standards and Scope of Practice

The ANA publishes Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. This resource establishes national standards for nurses and is updated regularly.[6]

The ANA defines the scope of nursing as “the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, facilitation of healing, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations.” A registered nurse (RN) is defined as an individual who is educationally prepared and licensed by a state to practice as a registered nurse. Nursing practice is characterized by the following tenets[7]:

- Caring and health are central to the practice of the registered nurse.

- Nursing practice is individualized to the unique needs of the health care consumer.

- Registered nurses use the nursing process to plan and provide individualized care for health care consumers.

- Nurses coordinate care by establishing partnerships to reach a shared goal of delivering safe, quality health care.

The ANA establishes Standards of Practice and Standards of Professional Performance in the Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice publication. State nurse practice acts further define the scope of practice of RNs and Licensed Practical Nurses/Vocational Nurses (LPNs/VNs) within each state. Nurse practice acts are further discussed in the “Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration” section of this chapter.

The ANA’s Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice publication can be purchased on the nursingworld.org website or borrowed from many libraries.

Standards of Practice

The ANA’s Standards of Practice are authoritative statements of duties that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, or specialty, are expected to perform competently. Standards of Practice include assessment, diagnosis, outcome identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation (ADOPIE) components of providing client care, also known as the “nursing process.” When nurses safely administer medication, all components of ADOPIE are addressed.

Assessment

The “Assessment” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.”[8] A registered nurse uses a systematic method to collect and analyze client data. Assessment includes physiological data, as well as psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, economic, and lifestyle data. For example, when a nurse assesses multiple pieces of data for a hospitalized client with pain, this is considered part of a comprehensive pain assessment.

Diagnosis

The “Diagnosis” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.”[9] A nursing diagnosis is the nurse’s clinical judgment about the client’s response to actual or potential health conditions or needs. Nursing diagnoses are used to create the nursing care plan and are different than medical diagnoses.[10]

Outcomes Identification

The “Outcomes Identification” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation.”[11] The nurse sets measurable and achievable short- and long-term goals and specific outcomes in collaboration with the client based on their assessment data and nursing diagnoses.

Planning

The “Planning” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse develops a collaborative plan encompassing strategies to achieve expected outcomes.”[12] Assessment data, diagnoses, and goals are used to select evidence-based nursing interventions customized to each client’s needs and concerns. Goals, expected outcomes, and nursing interventions are documented in the client’s nursing care plan so that nurses, as well as other health professionals, have access to it for continuity of care.[13]

Implementation

The “Implementation” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The nurse implements the identified plan.”[14] Nursing interventions are implemented or delegated to licensed practical nurses/vocational nurses (LPNs/VNs) or unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) with supervision. Interventions are also documented in the client’s electronic medical record as they are completed.[15]

The “Implementation” Standard of Professional Practice also includes the subcategories “Coordination of Care” and “Health Teaching and Health Promotion” to promote health and a safe environment.[16]

Coordination of Care

The ANA standard for coordination of care states, “The registered nurse coordinates care delivery.”[17] When ensuring medications are administered safely, the nurse collaborates with the client and the interprofessional health care team to meet mutually agreed upon outcomes. The nurse also engages the client in self-care to achieve their preferred goals for quality of life. For example, one client with chronic pain may have a pain management goal of “5” with their quality of life preference of having the ability to participate in social activities with friends but not experiencing burdensome side effect of medication. Another client with chronic pain may have a pain management goal of “0” with a quality of life preference of having no pain no matter what the side effects. The nurse advocates for these clients’ goals and preferences with the interprofessional team.

Nurses also serve vital roles in ensuring safe transitions and continuity of care regarding clients’ use of medications. Additional information about safe medication use and transitions of care is discussed in the “Preventing Medication Errors” section of this chapter.

Health Teaching and Health Promotion

When administering medications, nurses teach clients about the medications and potential side effects to promote optimal health. The ANA standard for health teaching and health promotion states, “The registered nurse employs strategies to teach and promote health and wellness.”[18] Specific behaviors related to teaching about medication are as follows[19]:

- Use health teaching and health promotion methods in collaboration with the client’s values, beliefs, health practices, developmental level, learning needs, readiness and ability to learn, language preference, spirituality, culture, and socioeconomic status.

- Provide clients with information and education about intended effects and potential adverse effects of the plan of care.

- Provide anticipatory guidance to clients to promote health and prevent or reduce risk.

In the book Preventing Medication Errors by the Institute of Medicine (2007), the following are additional key national guidelines when teaching clients about safe use of their medications:

- Clients should maintain an active list of all prescription drugs, over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, and dietary supplements they are taking, the reasons for taking them, and any known drug allergies. Every provider involved in the medication-use process for a client should have access to this list.

- Clients should be provided information about side effects, contraindications, methods for handling adverse reactions, and sources for obtaining additional objective, high-quality information.[20]

Evaluation

The “Evaluation” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of goals and outcomes.”[21] During evaluation, nurses assess the client and compare the findings against the initial assessment to determine the effectiveness of the interventions and overall nursing care plan. Both the client’s status and the effectiveness of the nursing care must be continuously evaluated and modified as needed.[22]

Read additional information about the nursing process in the “Nursing Process” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Standards of Professional Performance

ANA’s Standards of Professional Performance describe a competent level of behavior for nurses, including activities related to ethics, culturally congruent practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, evidence-based practice, and quality of practice.[23]

The ANA defines culturally congruent practice as the application of evidence-based nursing that is in agreement with the preferred cultural values, beliefs, worldview, and practices of the health care consumer and other stakeholders. Cultural competence represents the process by which nurses demonstrate culturally congruent practice. Nurses must assess the cultural beliefs and practices of their clients and implement culturally congruent interventions when administering medications and teaching about them. Additional information about cultural implications for medication administration is further discussed in the “Cultural and Social Determinants Related to Medication Administration” section later in this chapter.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.2b

A nurse is preparing to administer metoprolol, a cardiac medication, to a client and implements the nursing process:

ASSESSES the vital signs prior to administration and discovers the heart rate is 48.

DIAGNOSES that the heart rate is too low to safely administer the medication per the parameters provided. Establishes the OUTCOME to keep the client’s heart rate within normal range of 60-100.

PLANS to call the provider, as well as report this incident in the shift handoff report.

Implements INTERVENTIONS by withholding the metoprolol at this time, documenting the incident that the medication is withheld, and notifying the provider.

Continues to EVALUATE the client status throughout the shift after not receiving the metoprolol.

The nurse is providing health teaching to a client about the medication before discharge. The nurse provides a handout with instructions, as well as a list of the current medications.

What other information should be provided to the client?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

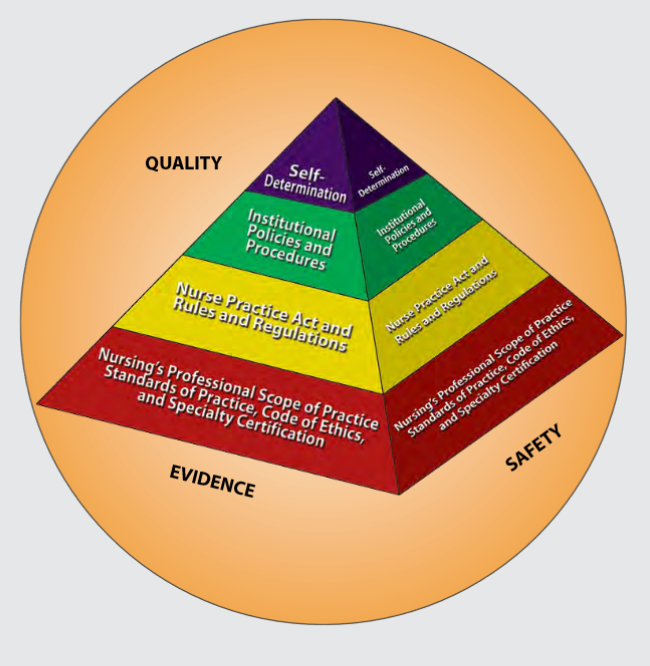

Figure 2.1 is an image from Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice by the ANA that illustrates how the scope of practice, standards of practice, and code of ethics form the “base” of nursing practice.[24] Nursing practice is further guided by the Nurse Practice Act in the state in which a nurse works, federal and state rules and regulations, institutional policies and procedures, and self-determination by the individual nurse. All these components are required to provide quality, safe client care that is evidence-based. These components will be further discussed in the remaining sections of this chapter.

NCLEX and the Clinical Judgment Model

The National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) is the national exam that graduates must pass successfully to obtain their nursing license after graduating from a nursing program of study. The NCLEX-PN is taken to become a licensed practical/vocational nurse (LPN/VN), and the NCLEX-RN is taken to become a licensed registered nurse (RN). The purpose of the NCLEX is to evaluate if a nursing graduate demonstrates the ability to provide safe, competent, entry-level nursing care. The NCLEX is developed by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), an independent, nonprofit organization composed of the 50 state boards of nursing and other regulatory agencies.[25]

A new edition of the NCLEX was launched in April 2023 that contains “Next Generation” questions. The Next Generation NCLEX (NGN) assesses how well the candidate can think critically and use clinical judgment. The NCSBN defines clinical judgment as “the observed outcome of critical thinking and decision-making. It is an iterative process with multiple steps that uses nursing knowledge to observe and assess presenting situations, identify a prioritized client concern and generate the best possible evidence-based solutions in order to deliver safe client care.”

The NCLEX uses the NCSBN’s Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) to assess the candidate’s ability to use safe clinical judgment when providing nursing care. Exam questions used to assess clinical judgment may be contained in a case study or as individual stand-alone items. A case study contains six questions that are associated with the same client scenario and addresses the following steps in clinical judgment[26]:

- Recognize cues: Identify relevant and important information from different sources (e.g., medical history, vital signs).

- Analyze cues: Organize and connect the recognized cues to the client’s clinical presentation.

- Prioritize hypotheses: Evaluate and prioritize hypotheses (based on urgency, likelihood, risk, difficulty, time constraints, etc.).

- Generate solutions: Identify expected outcomes and use hypotheses to define a set of interventions for the expected outcomes.

- Take action: Implement the solution(s) that address the highest priority.

- Evaluate outcomes: Compare observed outcomes to expected outcomes.

Throughout this book, learning activities are provided to assist students in learning how to apply the nursing process (i.e., ANA’s Standards of Care) to answer NGN-style questions that evaluate clinical judgment. Some of these activities are written, with answers in the Answer Key at the end of the book, and others are interactive and require use of the online book.

- American Nurses Association. (2019). About ANA. https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. https://www.nursingworld.org/coe-view-only ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. https://www.nursingworld.org/coe-view-only ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. https://www.nursingworld.org/coe-view-only ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. https://www.nursingworld.org/coe-view-only ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.) The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/nclex.htm ↵

- NCSBN. (n.d.). 2023 NCLEX-RN test plan. https://www.ncsbn.org/exams/testplans.page ↵

Let’s begin by reviewing the basic anatomy and physiology of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems.

Urinary System

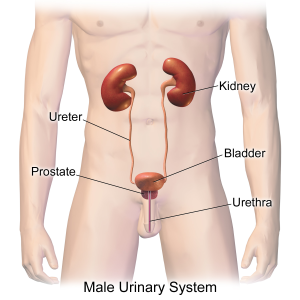

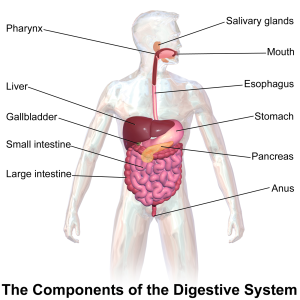

The urinary system, also referred to as the renal system or urinary tract, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH. The kidneys filter blood in the nephrons and remove waste in the form of urine. Urine exits the kidney via the ureters and enters the urinary bladder, where it is stored until it is expelled by urination (also referred to as voiding).[1] See Figure 16.1[2] for an image of the male urinary system. The female urinary system is similar except for a smaller urethra.

A healthy adult with normal kidney function produces 800-2,000 mL of urine per day, depending on fluid intake, as well as the amount of fluid lost through sweating and breathing. The bladder typically holds about 360-480 mL of urine. As the bladder fills, it sends signals to the brain that it is time to urinate. The urinary tract includes two sets of muscles that work together as a sphincter, closing off the urethra to keep urine in the bladder until the brain sends signals to urinate. Urination occurs when the brain sends signals to the wall of the bladder to contract and squeeze urine out of the bladder and through the urethra. Frequency of urination depends on how quickly the kidneys produce urine and how much urine a person’s bladder can comfortably hold.[3]

Normal urine should be clear, pale to light yellow in color, and not foul-smelling. However, some foods or medications may change the smell or color of urine. For instance, phenazopyridine (Pyridium), a common medication prescribed to treat the pain, frequency, and burning associated with urinary tract infections, can cause urine to appear orange.[4]

Nurses frequently monitor and document a client’s urine output as part of the overall plan of care. It can be collected by placing a collection hat in the client’s toilet and then measured in a graduated cylinder. If the client has an indwelling catheter, the urine is emptied every shift from the catheter bag and measured in a graduated cylinder. For infants and toddlers, the number of daily wet diapers provides a general measure of urine output. For more specific measurement of urine output during hospitalization, wet diapers are weighed.

Terms commonly used to document conditions related to the urinary tract are as follows:

- Anuria: Absence of urine output, typically found during kidney failure, defined as less than 50 mL of urine over a 24-hour period.

- Dysuria: Painful or difficult urination.

- Frequency: The need to urinate several times during the day or at night (nocturia) in normal or less-than-normal volumes. It may be accompanied by a feeling of urgency.[5]

- Hematuria: Blood in the urine, either visualized or found during microscopic analysis.

- Oliguria: Decreased urine output, defined as less than 500 mL of urine in adults in a 24-hour period. In hospitalized clients, oliguria is further defined as less than 0.5 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for adults and children or less than 1 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for infants.[6] New oliguria should be reported to the health care provider because it can indicate dehydration, fluid retention, or decreasing kidney function.

- Nocturia: The need to get up at night on a regular basis to urinate. Nocturia often causes sleep deprivation that affects a person’s quality of life.[7]

- Polyuria: Greater than 2.5 liters of urine output over 24 hours, also referred to as diuresis. Urine is typically clear with no color.[8] New polyuria should be reported to the health care provider because it can be a sign of many medical conditions.

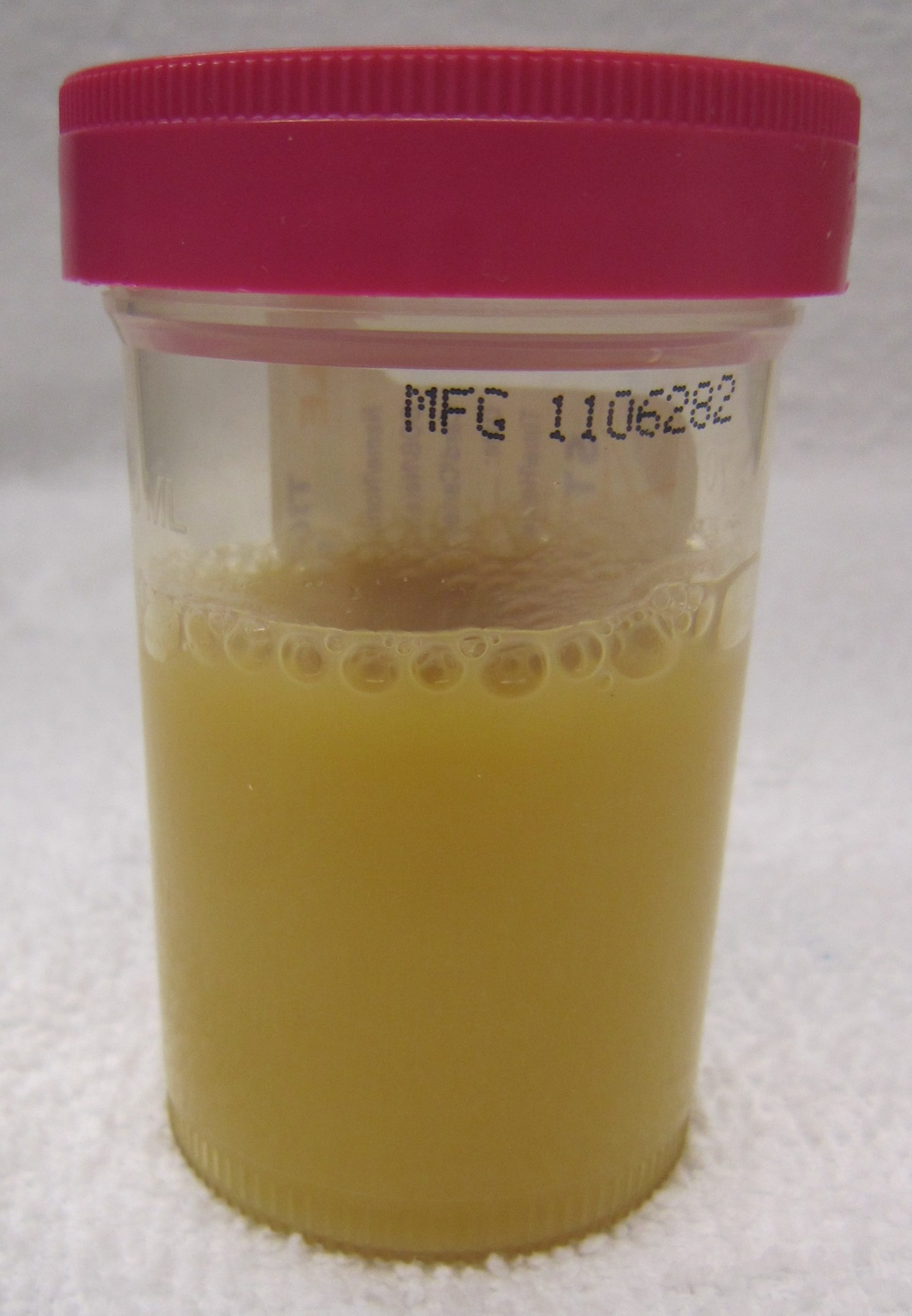

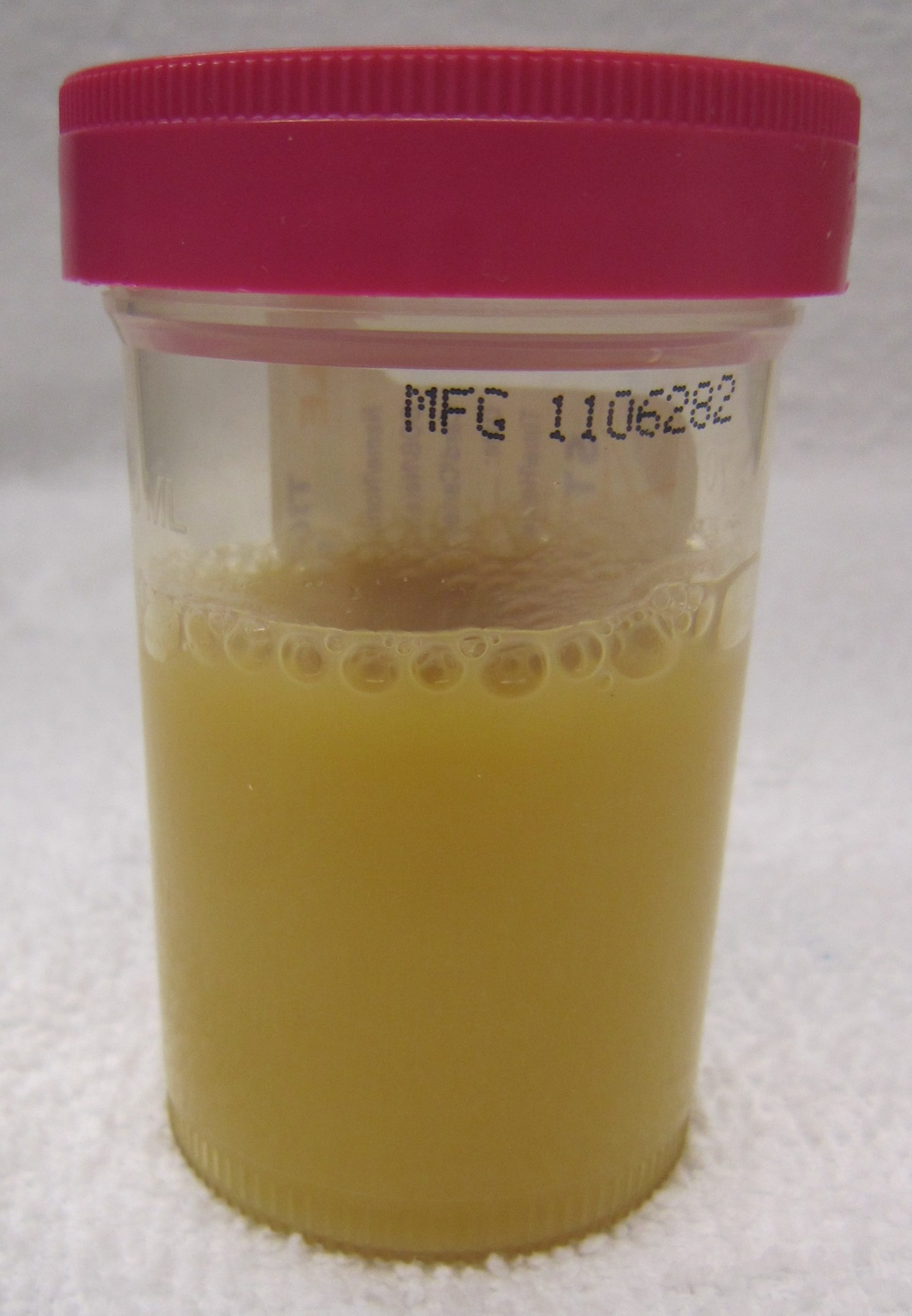

- Pyuria: At least ten white blood cells in each cubic millimeter of urine in a urine sample, typically indicating infection. In severe infections, pus may be visible in the urine.[9] See Figure 16.2[10] for an image of pyuria for a client with urosepsis.

- Urgency: A sensation of an urgent need to void.[11] Urgency can cause urge incontinence if the client is not able to reach the bathroom quickly.

View an activity reviewing the Vascular System of the Kidneys.

Gastrointestinal System

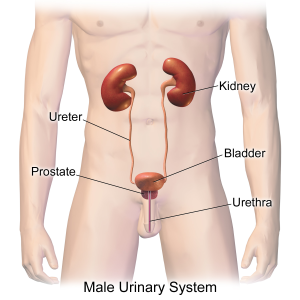

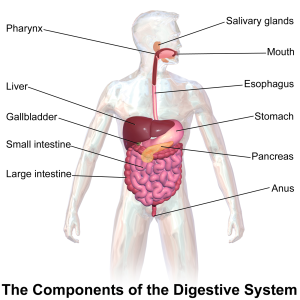

The gastrointestinal (GI) system includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. See Figure 16.3[12] for an image of the gastrointestinal system. Ingested food and liquid are pushed through the GI tract by peristalsis, the involuntary contraction and relaxation of muscle creating wave-like movements of the intestines. The stomach mixes food and liquid with digestive enzymes and then empties into the small intestine. The muscles of the small intestine mix food with enzymes and bile from the pancreas, liver, and intestine and push the mixture forward for further digestion. Bacteria in the GI tract, called normal flora or microbiome, also assist with digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients into the bloodstream. As peristalsis continues, the waste products of the digestive process move into the large intestine. The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste from liquid into stool. The rectum, at the lower end of the large intestine, stores stool until it is pushed out of the anus during a bowel movement.[13]

This section will focus on common alterations in bowel elimination, including constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence. These alterations are common symptoms of several diseases and conditions of the gastrointestinal system. Nurses provide care to help manage these alterations.

Terms related to alterations in bowel elimination include the following:

- Black stools: Black-colored stools can be side effects of iron supplements or bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol).

- Rectal bleeding: Rectal bleeding refers to bright red blood in the stools, also referred to as hematochezia. It is a sign of bleeding from the lower GI tract. Rectal bleeding can range in severity from minimal drops of blood on the toilet tissue caused by hemorrhoids to severe bleeding in large amounts that are life-threatening and require emergency care.[14] New bleeding should always be reported to the health care provider.

- Tarry stools: Stools that are black, sticky, and appear like tar are referred to as melena. Melena is typically caused by bleeding in the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus, stomach, or the first part of the small intestine, or due to the client swallowing blood. The blood appears darker and tarry-looking because it undergoes digestion on its way through the GI tract.[15] Bleeding from the upper part of the GI tract can also range from mild to life-threatening, depending upon the cause, and should always be reported to the health care provider.

Review information about digestion in the "Nutrition" chapter or read more information about the "Gastrointestinal" system in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Newborns and Infants

Meconium refers to the first bowel movement of a newborn that appears sticky and black to dark green in color. See Figure 16.4[16] for an image of meconium. The stool of a breastfed baby usually appears like a curdled yellow, while that of a formula-fed baby is pastier. Breastfed babies often have bowel movements after every feeding. Formula-fed babies tend to have fewer bowel movements.

Toddlers

Toddlers usually begin the process of toilet training between two and three years old. Enuresis is the term used to describe incontinence when sleeping (i.e., bed-wetting). Enuresis in children is considered normal unless it continues past seven or eight years of age, when it should be addressed with a pediatrician. Toddlers often have undigested food in their bowel movements due to the intestinal system not fully digesting some foods, such as corn or grapes.

Children

School-aged children may be at risk for developing constipation due to delaying bowel movements during school times until they are in the privacy of their homes. The longer the stool sits in the colon, the more water is absorbed by the intestines, and the harder stool becomes to pass.

Adults

Adult females often develop urinary incontinence related to pregnancy and delivery, menopause, or vaginal hysterectomy. Adult males may have urgency and urinary retention with possible overflow urinary incontinence as their prostate enlarges. Adults over the age of 30 may develop nocturia.

Older Adults

Peristalsis typically slows as aging occurs. Older adults should be encouraged to increase fluids, fiber, and activity, as appropriate, to prevent constipation. If a client is not able to meet the goal of a bowel movement with soft, formed stools every three days, then a bowel management program should be initiated.

Now that we have reviewed the basic structure and function of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems, let’s review the common alterations of urinary tract infection, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence in the following sections.

Let’s begin by reviewing the basic anatomy and physiology of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems.

Urinary System

The urinary system, also referred to as the renal system or urinary tract, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH. The kidneys filter blood in the nephrons and remove waste in the form of urine. Urine exits the kidney via the ureters and enters the urinary bladder, where it is stored until it is expelled by urination (also referred to as voiding).[17] See Figure 16.1[18] for an image of the male urinary system. The female urinary system is similar except for a smaller urethra.

A healthy adult with normal kidney function produces 800-2,000 mL of urine per day, depending on fluid intake, as well as the amount of fluid lost through sweating and breathing. The bladder typically holds about 360-480 mL of urine. As the bladder fills, it sends signals to the brain that it is time to urinate. The urinary tract includes two sets of muscles that work together as a sphincter, closing off the urethra to keep urine in the bladder until the brain sends signals to urinate. Urination occurs when the brain sends signals to the wall of the bladder to contract and squeeze urine out of the bladder and through the urethra. Frequency of urination depends on how quickly the kidneys produce urine and how much urine a person’s bladder can comfortably hold.[19]

Normal urine should be clear, pale to light yellow in color, and not foul-smelling. However, some foods or medications may change the smell or color of urine. For instance, phenazopyridine (Pyridium), a common medication prescribed to treat the pain, frequency, and burning associated with urinary tract infections, can cause urine to appear orange.[20]

Nurses frequently monitor and document a client’s urine output as part of the overall plan of care. It can be collected by placing a collection hat in the client’s toilet and then measured in a graduated cylinder. If the client has an indwelling catheter, the urine is emptied every shift from the catheter bag and measured in a graduated cylinder. For infants and toddlers, the number of daily wet diapers provides a general measure of urine output. For more specific measurement of urine output during hospitalization, wet diapers are weighed.

Terms commonly used to document conditions related to the urinary tract are as follows:

- Anuria: Absence of urine output, typically found during kidney failure, defined as less than 50 mL of urine over a 24-hour period.

- Dysuria: Painful or difficult urination.

- Frequency: The need to urinate several times during the day or at night (nocturia) in normal or less-than-normal volumes. It may be accompanied by a feeling of urgency.[21]

- Hematuria: Blood in the urine, either visualized or found during microscopic analysis.

- Oliguria: Decreased urine output, defined as less than 500 mL of urine in adults in a 24-hour period. In hospitalized clients, oliguria is further defined as less than 0.5 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for adults and children or less than 1 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for infants.[22] New oliguria should be reported to the health care provider because it can indicate dehydration, fluid retention, or decreasing kidney function.

- Nocturia: The need to get up at night on a regular basis to urinate. Nocturia often causes sleep deprivation that affects a person’s quality of life.[23]

- Polyuria: Greater than 2.5 liters of urine output over 24 hours, also referred to as diuresis. Urine is typically clear with no color.[24] New polyuria should be reported to the health care provider because it can be a sign of many medical conditions.

- Pyuria: At least ten white blood cells in each cubic millimeter of urine in a urine sample, typically indicating infection. In severe infections, pus may be visible in the urine.[25] See Figure 16.2[26] for an image of pyuria for a client with urosepsis.

- Urgency: A sensation of an urgent need to void.[27] Urgency can cause urge incontinence if the client is not able to reach the bathroom quickly.

View an activity reviewing the Vascular System of the Kidneys.

Gastrointestinal System

The gastrointestinal (GI) system includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. See Figure 16.3[28] for an image of the gastrointestinal system. Ingested food and liquid are pushed through the GI tract by peristalsis, the involuntary contraction and relaxation of muscle creating wave-like movements of the intestines. The stomach mixes food and liquid with digestive enzymes and then empties into the small intestine. The muscles of the small intestine mix food with enzymes and bile from the pancreas, liver, and intestine and push the mixture forward for further digestion. Bacteria in the GI tract, called normal flora or microbiome, also assist with digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients into the bloodstream. As peristalsis continues, the waste products of the digestive process move into the large intestine. The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste from liquid into stool. The rectum, at the lower end of the large intestine, stores stool until it is pushed out of the anus during a bowel movement.[29]

This section will focus on common alterations in bowel elimination, including constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence. These alterations are common symptoms of several diseases and conditions of the gastrointestinal system. Nurses provide care to help manage these alterations.

Terms related to alterations in bowel elimination include the following:

- Black stools: Black-colored stools can be side effects of iron supplements or bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol).

- Rectal bleeding: Rectal bleeding refers to bright red blood in the stools, also referred to as hematochezia. It is a sign of bleeding from the lower GI tract. Rectal bleeding can range in severity from minimal drops of blood on the toilet tissue caused by hemorrhoids to severe bleeding in large amounts that are life-threatening and require emergency care.[30] New bleeding should always be reported to the health care provider.

- Tarry stools: Stools that are black, sticky, and appear like tar are referred to as melena. Melena is typically caused by bleeding in the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus, stomach, or the first part of the small intestine, or due to the client swallowing blood. The blood appears darker and tarry-looking because it undergoes digestion on its way through the GI tract.[31] Bleeding from the upper part of the GI tract can also range from mild to life-threatening, depending upon the cause, and should always be reported to the health care provider.

Review information about digestion in the "Nutrition" chapter or read more information about the "Gastrointestinal" system in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Newborns and Infants

Meconium refers to the first bowel movement of a newborn that appears sticky and black to dark green in color. See Figure 16.4[32] for an image of meconium. The stool of a breastfed baby usually appears like a curdled yellow, while that of a formula-fed baby is pastier. Breastfed babies often have bowel movements after every feeding. Formula-fed babies tend to have fewer bowel movements.

Toddlers

Toddlers usually begin the process of toilet training between two and three years old. Enuresis is the term used to describe incontinence when sleeping (i.e., bed-wetting). Enuresis in children is considered normal unless it continues past seven or eight years of age, when it should be addressed with a pediatrician. Toddlers often have undigested food in their bowel movements due to the intestinal system not fully digesting some foods, such as corn or grapes.

Children

School-aged children may be at risk for developing constipation due to delaying bowel movements during school times until they are in the privacy of their homes. The longer the stool sits in the colon, the more water is absorbed by the intestines, and the harder stool becomes to pass.

Adults

Adult females often develop urinary incontinence related to pregnancy and delivery, menopause, or vaginal hysterectomy. Adult males may have urgency and urinary retention with possible overflow urinary incontinence as their prostate enlarges. Adults over the age of 30 may develop nocturia.

Older Adults

Peristalsis typically slows as aging occurs. Older adults should be encouraged to increase fluids, fiber, and activity, as appropriate, to prevent constipation. If a client is not able to meet the goal of a bowel movement with soft, formed stools every three days, then a bowel management program should be initiated.

Now that we have reviewed the basic structure and function of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems, let’s review the common alterations of urinary tract infection, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence in the following sections.

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common infection that occurs when bacteria, typically from the rectum, enter the urethra and infect the urinary tract. Infections can affect several parts of the urinary tract, but the most common type is a bladder infection (cystitis). Kidney infections (pyelonephritis) are more serious than a bladder infection because they can have long-lasting effects on the kidneys.[33]

Some people are at higher risk of getting a UTI. UTIs are more common in females because their urethras are shorter and closer to the rectum, which makes it easier for bacteria to enter the urinary tract. Other factors that can increase the risk of UTIs include the following:

- A previous UTI

- Sexual activity, especially with a new sexual partner

- Pregnancy

- Age (Older adults and young children are at higher risk. Refer to the "Care of the Older Adult" chapter for more details about older adults.)

- Structural problems in the urinary tract, such as prostate enlargement[34]

Symptoms of a UTI include the following:[35]

- Pain or burning while urinating (dysuria)

- Frequent urination (frequency)

- Urgency with small amounts of urine

- Bloody urine

- Pressure or cramping in the groin or lower abdomen

- Confusion or altered mental status in older adults

Symptoms of a more serious kidney infection (pyelonephritis) include fever above 101 degrees F (38.3 degrees C), shaking chills, lower back pain or flank pain (i.e., on the sides of the back), and nausea or vomiting.[36] It is important to remember that older adults with a UTI may not exhibit these symptoms but often demonstrate an increased level of confusion. Sometimes UTIs can spread to the blood (septicemia), leading to life-threatening infection called sepsis. Read more about sepsis in the “Infection” chapter.

When a client presents with symptoms of a UTI, the provider will order diagnostic tests, such as a urine dip, urinalysis, or urine culture. Read more about diagnostic tests in the “Assessment” section of the "Nursing Process" chapter.

Interventions

Antibiotics are prescribed for urinary tract infections. Nurses provide important health teaching to clients with a UTI, such as the importance of finishing their antibiotic therapy as prescribed, even if they begin to feel better after a few days, to minimize the risk of developing antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. Clients should also be encouraged to drink extra fluids to help flush bacteria from the urinary tract. Additional health teaching regarding preventing future UTIs includes the following[37]:

- Urinate after sexual activity to flush bacteria away from the urethra.

- Stay well-hydrated and urinate regularly.

- Take showers instead of baths to minimize irritation and bacterial contamination of the urethra.

- Minimize douching, sprays, or powders in the genital area to prevent altering the pH and normal flora of this area.

- Teach females to wipe front to back to minimize contamination of the urethra with bacteria from the anus.

Urinary incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine. Although abnormal, it is a common symptom that can seriously affect the physical, psychological, and social well-being of affected individuals of all ages. It has been estimated that 1 in 5 women develop urinary incontinence, but many are too embarrassed to discuss the condition with their health care providers. Some believe it’s a normal part of aging that they have to live with. The result can be isolation and depression when they limit their activities and social interactions because of embarrassment due to incontinence. Nurses can greatly improve the quality of life for these clients by assessing for incontinence in a sensitive manner and then providing health teaching about methods to prevent and/or manage incontinence.

Types of Urinary Incontinence

Continence is achieved through an interplay of the physiology of the bladder, urethra, sphincter, pelvic floor, and the nervous system coordinating these organs.[38] A disruption in any of these areas can cause several types of urinary incontinence.

- Stress urinary incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine with intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., laughing and coughing) or physical exertion (e.g., jumping). It is caused by weak pelvic floor muscles that is often the result of pregnancy and vaginal delivery, menopause, and vaginal hysterectomy.[39]

- Urge urinary incontinence (also referred to as “overactive bladder”) is urine leakage caused by the sensation of a strong desire to void (urgency). It can be caused by increased sensitivity to stimulation by the detrusor muscle in the bladder or decreased inhibitory control of the central nervous system.[40]

- Mixed urinary incontinence is a mix of urinary frequency, urgency, and stress incontinence.[41]

- Overflow incontinence occurs when small amounts of urine leak from a bladder that is always full. This condition tends to occur in males with enlarged prostates that prevent the complete emptying of the bladder.[42]

- Functional incontinence occurs in older adults who have normal bladder control but have a problem getting to the toilet because of arthritis or other disorders that make it hard to move quickly or manipulate zippers or buttons. Clients with dementia also have increased risk for functional incontinence.

It is important for nurses to understand the different types of incontinence so that appropriate interventions can be targeted to the cause.

Assessment of Incontinence

Assessment begins with screening questions during a health history, including questions such as, “Do you have any problems with the leakage or dribbling of urine? Do you ever have problems making it to the bathroom in time?” If a client responds “Yes” to either of these questions, it is helpful to encourage them to start a voiding diary to record their urination habits and activities. The voiding diary should include the following[43]:

- When and how much the client urinates

- Urinary leakage and what the client was doing when it happened (for example, running, biking, laughing)

- Sudden urges to urinate

- How often the client wakes at night to use the bathroom

- Type and volume of food and beverages and the time of intake

- Medication use, such as diuretics, and the timing of administration

- Any pain or problems experienced before, during, and after urinating (for example, sudden urges, difficulty urinating, dribbling urine, feeling as if the bladder is never empty, weak urine flow).

The provider will review information from the voiding diary, perform a physical assessment, and likely order diagnostic testing, such as a urine dip to check for a urinary tract infection, and urodynamic diagnostic testing that includes a variety of tests about bladder function, including filling, urine storage, and emptying.[44] Individualized treatment will be based on the assessment and tests to assess any structural abnormalities and bladder function.

Interventions

Nurses should use therapeutic communication with clients experiencing urinary incontinence to help them feel comfortable in expressing their fears, worries, and embarrassment about incontinence and work toward improving their quality of life. Let them know they’re not alone and that urinary incontinence is not something they have to live with. Provide education about pelvic floor muscle training exercises, timed voiding, lifestyle modification, and incontinence products. Encourage them to learn more about their condition so they can optimally manage it and improve their quality of life.[45]

Nurses play an important role in educating clients about bladder control training to prevent incontinence. Bladder control training includes several these techniques:

- Pelvic muscle exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) work the muscles used to stop urination, which can help prevent stress incontinence. Learn more about pelvic floor exercises in the box below.

- Timed voiding can be used to help a client regain control of the bladder. Timed voiding encourages the client to urinate on a set schedule, for example, every hour, whether they feel the urge to urinate or not. The time between bathroom trips is gradually extended with the general goal of achieving four hours between voiding. Timed voiding helps to control urge and overflow incontinence as the brain is trained to be less sensitive to the sensation of the bladder walls expanding as they fill.[46]

- Lifestyle changes can help with incontinence. Losing weight, drinking less caffeine (found in coffee, tea, and many sodas), preventing constipation, and avoiding lifting heavy objects may help with incontinence. Limiting fluid intake before bedtime and scheduling prescribed diuretic medication in the morning or early afternoon are also helpful.[47]

- Protective products may be needed to protect the skin from breakdown and prevent leakage onto clothing. Incontinence underwear has a waterproof liner and built-in cloth pad to absorb large amounts of urine to protect skin from moisture and control odor. It is available in daytime and nighttime styles (designed to hold more urine). A product resembling a tampon is another option for females. It is made of absorbent fibers that support the urethra and prevents accidental leaks but doesn’t inhibit urination and won’t move or fall out during bowel movements.[48]

Teaching Pelvic Floor Exercises

Kegel exercises are designed to make your pelvic floor muscles stronger. Your pelvic floor muscles hold up your bladder and prevent it from leaking urine.

- Start by finding the right muscles. There are two easy ways to do this: stop the stream of urine as you are urinating or imagine that you are trying to stop the passage of gas. Squeeze the muscles you would use to do both. If you sense a "pulling" feeling, you are squeezing the right muscles for pelvic exercises. Many people have trouble finding the right muscles. A doctor, nurse, or therapist can check to make sure you are doing the exercises correctly and targeting the correct muscles.

- Find a quiet spot to practice so you can concentrate. Lie on the floor. Pull in the pelvic muscles and hold for a count of 3. Then relax for a count of 3. Work up to 10 to 15 repeats each time you exercise.

- Complete pelvic exercises at least three times a day. Try to use three different positions while performing the exercises: lying down, sitting, and standing. For example, you can exercise while lying on the floor, sitting at a desk, or standing in the kitchen. Using all three positions while exercising makes these muscles their strongest.

- Be patient. Most people notice an improvement after a few weeks, but the maximum effect may take up to 3-6 weeks.

View a YouTube video about Kegel Exercises[49] from Michigan Medicine.

Health teaching regarding other treatment options may be provided:

- Biofeedback uses sensors to help a client become more aware of signals from the body to regain control over the muscles in their bladder and urethra.[50]

- Mechanical devices, such as pessaries, support the urethra and can support vaginal prolapse to prevent or reduce urinary leakage. They come in various sizes and are professionally fitted by trained health care providers. They should be removed, cleaned, and reinserted regularly to prevent infection. Some of the devices, such as ring pessaries, can be removed and reinserted by the client. They are similar to a diaphragm and can be removed or left in place for sexual intercourse.[51]

- Anticholinergic medications, such as oxybutynin, may be prescribed to treat urge urinary incontinence and mixed urinary incontinence. They block the action of acetylcholine and provide an antispasmodic effect on smooth muscle to relieve symptoms. However, side effects include dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, and drowsiness, which can increase fall risk in older adults.

- If bladder training and medications are not effective, surgery may be performed, such as a sling procedure or a bladder neck suspension.[52]