15.2 Basic Concepts of Administering Medications

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

The scope of practice regarding a nurse’s ability to legally dispense and administer medication is based on each state’s Nurse Practice Act. Registered Nurses (RNs) and Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs/LVNs) may legally administer medications that are prescribed by a health care provider, such as a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician’s assistant. Prescriptions are “orders, interventions, remedies, or treatments ordered or directed by an authorized primary health care provider.”[1]

For more information about the state Nurse Practice Act, visit the “Legal/Ethical” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Types of Orders

Prescriptions are often referred to as orders in clinical practice. There are several types of orders, such as routine orders, PRN orders, standing orders, one-time orders, STAT orders, and titration orders.

- A routine order is a prescription that is followed until another order cancels it. An example of a routine order is “Lisinopril 10 mg PO daily.”

- A PRN order is a prescription for medication to be administered when it is requested by, or as needed, by the patient. PRN orders are typically administered based on patient symptoms, such as pain, nausea, or itching. An example of a PRN order for pain medication is “Acetaminophen 500 mg PO every 4-6 hours as needed for pain.”

- A standing order is also referred to in practice as an “order set” or a “protocol.” Standing orders are standardized prescriptions for nurses to implement to any patient in clearly defined circumstances without the need to initially notify a provider. An example of a standing order set/protocol for patients visiting an urgent care clinic reporting chest pain is to immediately administer four chewable aspirin, establish intravenous (IV) access, and obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG).

- A one-time order is a prescription for a medication to be administered only once. An example of a one-time order is a prescription for an IV dose of antibiotics to be administered immediately prior to surgery.

- A STAT order is a one-time order that is administered without delay due to the urgency of the circumstances. An example of a STAT order is “Benadryl 50 mg PO stat” for a patient having an allergic reaction.

- A titration order is an order in which the medication dose is either progressively increased or decreased by the nurse in response to the patient’s status. Titration orders are typically used for patients in critical care as defined by agency policy. The Joint Commission requires titration orders to include the medication name, medication route, initial rate of infusion (dose/unit of time), incremental units to which the rate or dose can be increased or decreased, how often the rate or dose can be changed, the maximum rate or dose of infusion, and the objective clinical measure to be used to guide changes. An example of a titration order is “Norepinephrine 2-12 micrograms/min, start at 2 mcg/min and titrate upward by 1 mcg/min every 5 minutes with continual blood pressure monitoring until systolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg.”

Components of a Medication Order

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, all orders for the administration of drugs and biologicals must contain the following information[2]:

- Name of the patient

- Age or date of birth

- Date and time of the order

- Drug name

- Dose, frequency, and route

- Name/Signature of the prescriber

- Weight of the patient to facilitate dose calculation when applicable. (Note that dose calculations are based on metric weight: kilograms for children/adults or grams for newborns)

- Dose calculation requirements, when applicable

- Exact strength or concentration, when applicable

- Quantity and/or duration of the prescription, when applicable

- Specific instructions for use, when applicable

When reviewing a medication order, the nurse must ensure these components are included in the prescription before administering the medication. If a pertinent piece of information is not included, the nurse must contact the prescribing provider to clarify and correct the order.

Drug Name

The name of the drug may be ordered by the generic name or brand name. The generic name is considered the safest method to use and allows for substitution of various brand medications by the pharmacist.

Dose

The dosage of a drug is prescribed using either the metric or the household system. The metric system is the most commonly accepted system internationally. Examples of standard dosage are 5 mL (milliliters) or 1 teaspoon. Standard abbreviations of metric measurement are frequently used regarding the dosage, such as mg (milligram), kg (kilogram), mL (milliliter), mcg (microgram), or L (liter). However, it is considered safe practice to avoid other abbreviations and include the full words in prescriptions to avoid errors. In fact, several abbreviations have been deemed unsafe by the Joint Commission and have been put on a “do not use” list. See the box below to view The Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use List” and the Institute of Safe Medication Practices’ (ISMP) list of abbreviations to avoid. If a dosage is unclear or written in a confusing manner in a prescription, it is always best to clarify the order with the prescribing provider before administering the medication.

Frequency

Frequency in prescriptions is indicated by how many times a day the medication is to be administered or how often it is to be administered in hours or minutes. Examples of frequency include verbiage such as once daily, twice daily, three times daily, four times daily, every 30 minutes, every hour, every four hours, or every eight hours. Medication times are typically indicated using military time (i.e., using a 24-hour clock). For example, 11 p.m. is indicated as “2300.” Read more about military time in the “Math Calculations” chapter.

Some types of medications may be ordered “around the clock (ATC).” An around-the-clock frequency order indicates they should be administered at regular time intervals, such as every six hours, to maintain consistent levels of the drug in the patient’s bloodstream. For example, pain medications administered at end of life are often prescribed ATC instead of PRN (as needed) to maintain optimal pain relief.

Route of Administration

Common routes of administration and standard abbreviations include the following:

- Oral (PO) – the patient swallows a tablet or capsule

- Sublingual (SL) – applied under the tongue

- Enteral (NG or PEG) – administered via a tube directly into the GI tract

- Rectal (PR) – administered via rectal suppository

- Inhalation (INH) – the patient breathes in medication from an inhaler

- Intramuscular (IM) – administered via an injection into a muscle

- Subcutaneous – administered via injection into the fat tissue beneath the skin (Note that “subcutaneous” is on ISMP’s recommended list of abbreviations to avoid due to common errors.)

- Transdermal (TD) – administered by applying a patch on the skin

For more information about routes of administration and considerations regarding absorption, visit the “Kinetics and Dynamics” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Provider Name/Signature

The signature of the prescribing provider is required on the order and can be electronic or handwritten. Verbal orders from a prescriber are not recommended but may be permitted in some agencies for urgent situations. Verbal orders require the nurse to “repeat back” the order to the prescriber for confirmation.

Rights of Medication Administration

Each year in the United States, 7,000 to 9,000 people die as a result of a medication error. Hundreds of thousands of other patients experience adverse reactions or other complications related to a medication. The total cost of caring for patients with medication-associated errors exceeds $40 billion each year. In addition to the monetary cost, patients experience psychological and physical pain and suffering as a result of medication errors.[3] Nurses play a vital role in reducing the number of medication errors that occur by verifying several rights of medication.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services requires nurses to verify specific information prior to the administration of medication to avoid errors, referred to as verifying the rights of medication administration.[4] These rights of medication administration are the vital last safety check by nurses to prevent errors in the chain of medication administration that includes the prescribing provider, the pharmacist, the nurse, and the patient.

It is important to remember that if a medication error occurs resulting in harm to a patient, a nurse can be held liable even if “just following orders.” It is absolutely vital for nurses to use critical thinking and clinical judgment to ensure each medication is safe for each specific patient before administering it. The consequences of liability resulting from a medication error can range from being charged with negligence in a court of law, to losing one’s job, to losing one’s nursing license.

The six rights of medication administration must be verified by the nurse at least three times before administering a medication to a patient. These six rights include the following:

- Right Patient

- Right Drug

- Right Dose

- Right Time

- Right Route[5]

- Right Documentation

Recent literature indicates that up to ten rights should be completed as part of a safe medication administration process. These additional rights include Right History and Assessment, Right Drug Interactions, Right to Refuse, and Right Education and Information. Information for each of these rights is further described below.[6],[7]

Right Patient

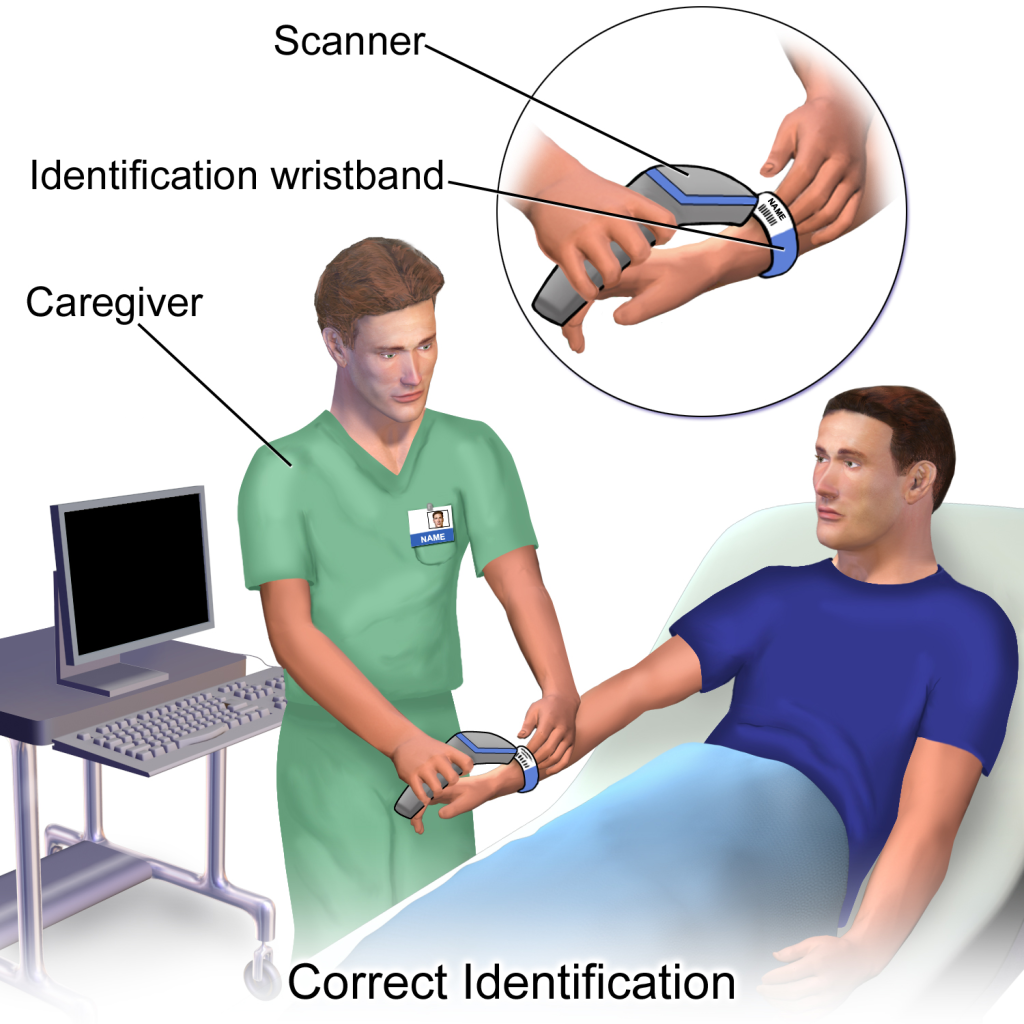

Acceptable patient identifiers include, but are not limited to, the patient’s full name, an identification number assigned by the hospital, or date of birth. A patient’s room number must never be used as an identifier because a patient may change rooms. Identifiers must be confirmed by the patient wristband, patient identification card, patient statement (when possible), or other means outlined in the agency policy such as a patient picture included on the MAR. The nurse must confirm the patient’s identification matches the medication administration record (MAR) and medication label prior to administration to ensure that the medication is being given to the correct patient.[8] See Figure 15.1[9] for an illustration of the nurse verifying the patient’s identify by scanning their identification band and asking for their date of birth. See Figure 15.2[10] for a close-up image of a patient identification wristband.

If barcode scanning is used in an agency, this scanning is not intended to take the place of confirming two patient identifiers but is intended to add another layer of safety to the medication administration process. The National Patient Safety Goals established by The Joint Commission state that whenever administering patient medications, at least two patient identifiers should be used.[11]

Right Drug

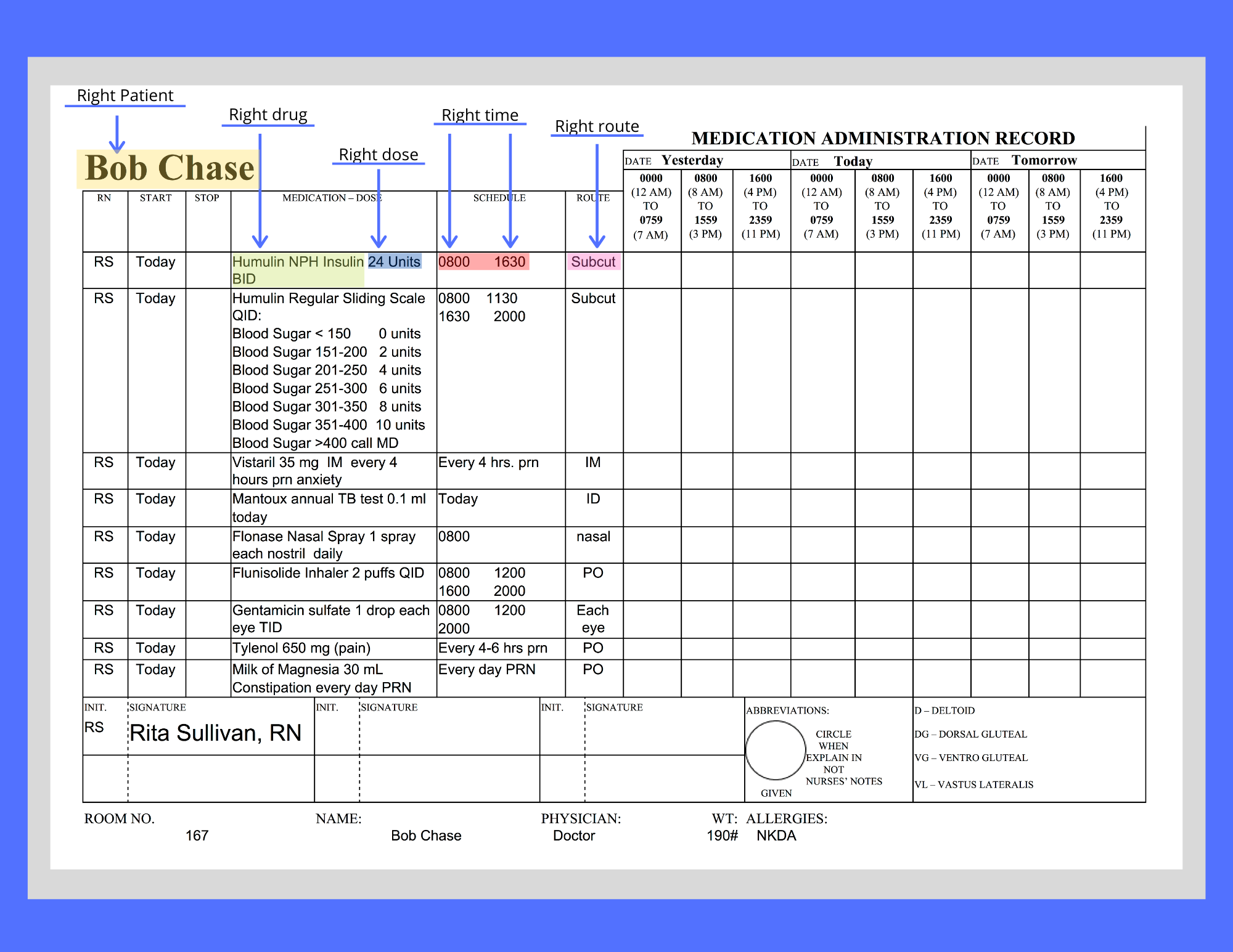

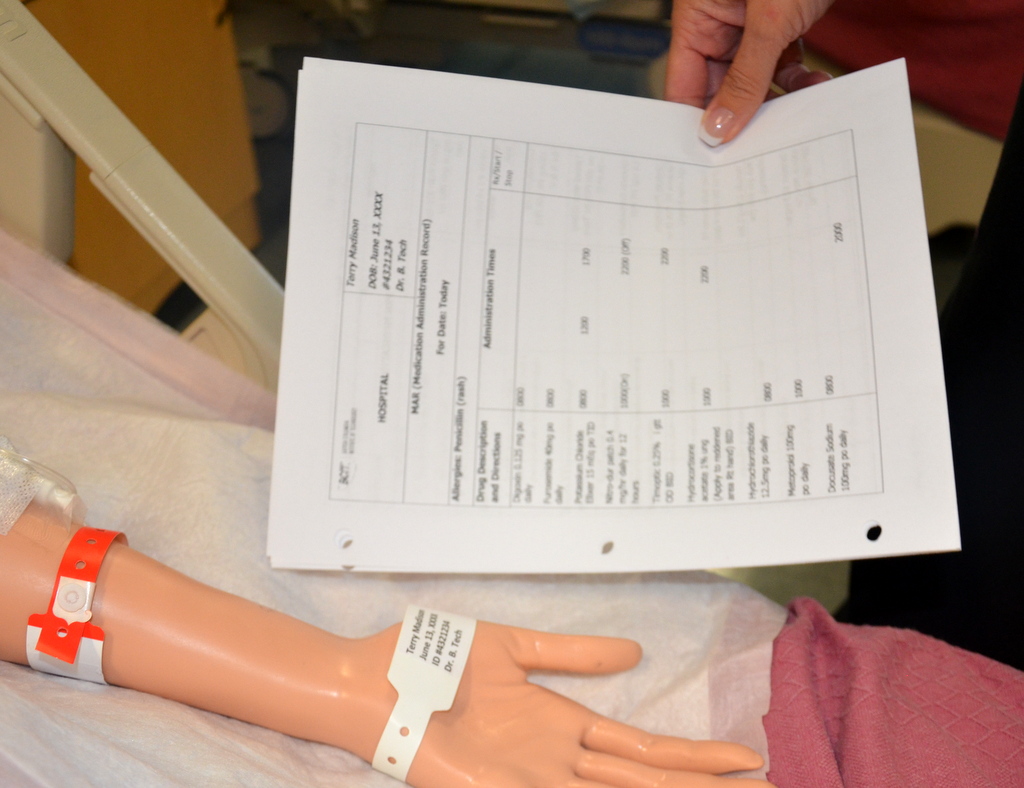

During this step, the nurse ensures the medication to be administered to the patient matches the order or Medication Administration Record (MAR) and that the patient does not have a documented allergy to it. Also, check the expiration date of the medication.[12] The Medication Administration Record (MAR), or eMAR, an electronic medical record, is a specific type of documentation found in a patient’s chart. See Figure 15.3[13] for an image of an MAR and its components. Beware of look-alike and sound-alike medication names, as well as high-alert medications that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm if they are used in error. The nurse should also be aware of what medication can be crushed and those that cannot be crushed. Read more information about these concerns using the box below.

View the ISMP Frequently Confused Medication List.

View a PDF of the ISMP High-Alert Medications List.

View the ISMP Do Not Crush List.

Right Dose

During this step, the nurse ensures the dosage of the medication matches the prescribed dose, verifies the correct dosage range for the age and medical status of the patient, and also confirms that the prescription itself does not reflect an unsafe dosage level (i.e., a dose that is too high or too low).[14] For example, medication errors commonly occur in children, who typically receive a lower dose of medication than an adult. Medication errors also commonly occur in older patients who have existing kidney or liver disease and are unable to metabolize or excrete typical doses of medications.

Right Time and Frequency

During this step, the nurse verifies adherence to the prescribed frequency and scheduled time of administration of the medication.[15] This step is especially important when PRN medications are administered because it is up to the nurse to verify the time of the previous dose and compare it to the ordered frequency.

Medications should be administered on time whenever possible. However, when multiple patients are scheduled to receive multiple medications at the same time, this goal of timeliness can be challenging. Most facilities have a policy that medications can be given within a range of 30 minutes before or 30 minutes after the medication is scheduled. For example, a medication ordered for 0800 could be administered anytime between 0730 and 0830. However, some medications must be given at their specific ordered time due to pharmacokinetics of the drug. For example, if an antibiotic is scheduled every eight hours, this time frame must be upheld to maintain effective bioavailability of the drug, but a medication scheduled daily has more flexibility with time of actual administration.

Right Route

During this step, the nurse ensures the route of administration is appropriate for the specific medication and also for the patient.[16] Many medications can potentially be administered via multiple routes, whereas other medications can only be given safely via one route. Nurses must administer medications via the route indicated in the order. If a nurse discovers an error in the order or believes the route is unsafe for a particular patient, the route must be clarified with the prescribing provider before administration. For example, a patient may have a PEG tube in place, but the nurse notices the medication order indicates the route of administration as PO. If the nurse believes this medication should be administered via the PEG tube and the route indicated in the order is an error, the prescribing provider must be notified, and the order must be revised indicating via PEG tube before the medication is administered.

Right Documentation

After administering medication, it is important to immediately document the administration to avoid potential errors from an unintended repeat dose.

In addition to checking the basic rights of medication administration and documenting the administration, it is also important for nurses to verify the following information to prevent medication errors.

Right History and Assessment

The nurse should be aware of the patient’s allergies, as well as any history of any drug interactions. Additionally, nurses collect appropriate assessment data regarding the patient’s history, current status, and recent lab results to identify any contraindications for the patients to receive the prescribed medication.[17]

Right Drug Interactions

The patient’s history should be reviewed for any potential interactions with medications previously given or with the patient’s diet. It is also important to verify the medication’s expiration date before administration.

Right Education and Information

Information should be provided to the patient about the medication, including the expected therapeutic effects, as well as the potential adverse effects. The patient should be encouraged to report suspected side effects to the nurse and/or prescribing provider. If the patient is a minor, the parent may also have a right to know about the medication in many states, depending upon the circumstances.

Right of Refusal

After providing education about the medication, the patient has the right to refuse to take medication in accordance with the nursing Code of Ethics and respect for individual patient autonomy. If a patient refuses to take the medication after proper education has been performed, the event should be documented in the patient chart and the prescribing provider notified.

Medication Dispensing

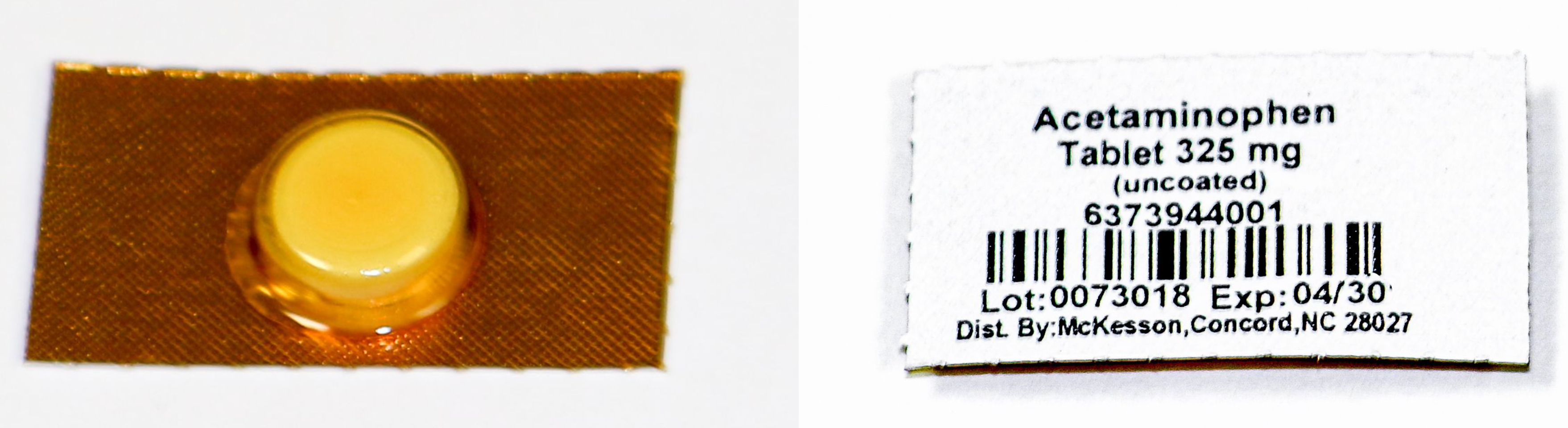

Medications are dispensed for patients in a variety of methods. During inpatient care, unit dose packaging is a common method for dispensing medications. See Figure 15.4[18] for an image of unit dose packaging.

Unit dose dispensing is typically used in association with a medication dispensing system, sometimes referred to in practice with brand names such as “Pyxis” or “Omnicell.” Medication dispensing systems help keep medications secure by requiring a user sign-in and password. They also reduce medication errors by only allowing medications prescribed for a specific patient to be removed unless additional actions are taken. However, it is important to remember that medication errors can still occur when using a medication dispensing system if the incorrect medication is erroneously stocked in a compartment. See Figure 15.5[19] for an image of a medication dispensing system.

Barcodes are often incorporated with unit dose medication dispensing as an additional layer of safety to prevent medication errors. Each patient and medication is identified with a unique bar code. The nurse scans the patient’s identification wristband with a bedside portable device and then scans each medication to be administered. The portable device will display error messages if an incorrect medication is scanned or if medication is scanned at an incorrect time. It is vital for nurses to stop and investigate the medication administration process when an error is received. The scanning device is typically linked to an electronic MAR and the medication administered is documented immediately in the patient’s chart.

In long-term care agencies, weekly blister cards may be used that contain a specific patient’s medications for each day of the week. See Figure 15.6[20] for an image of a blister pack.

Agencies using blister cards or pill bags typically store medications in a locked medication cart to keep them secure. Supplies used to administer medications are also stored on the cart. The MAR is available in printed format or electronically with a laptop computer. See Figure 15.7[21] for an image of a medication cart.

Process of Medication Administration

No matter what method of medication storage and dispensing is used in a facility, the nurse must continue to verify the rights of medication administration to perform an accurate and safe medication pass. Using a medication dispensing system or barcoding does not substitute for verifying the rights but is used to add an additional layer of safety to medication administration. Nurses can also avoid medication errors by creating a habitual process of performing medication checks when administering medication. The rights of medication administration should be done in the following order:

- Perform the first check as the unit dose package, blister pack, or pill bag is removed from the dispensing machine or medication cart. Also, check the expiration date of the medication.

- A second check should be performed after the medication is removed from the dispensing machine or medication cart. This step should be performed prior to pouring or removing from a multidose container. Note: Some high-alert medications, such as insulin, require a second nurse to perform a medication check at this step due to potentially life-threatening adverse effects that can occur if an error is made.

- The third check should be performed immediately before administering the medication to the patient at the bedside or when replacing the multidose container back into the drawer.

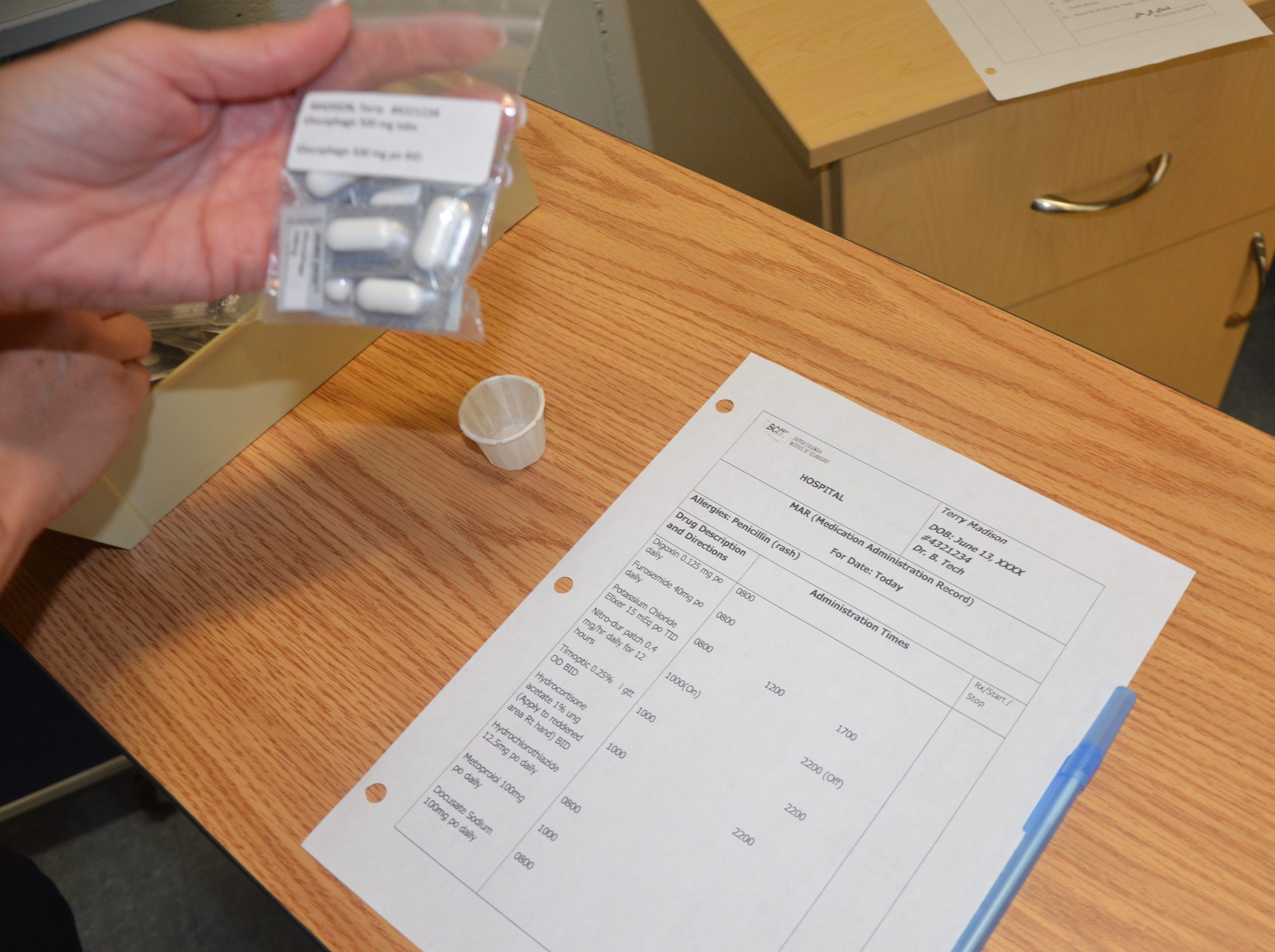

See Figure 15.8[22] for an image of a nurse comparing medication information on the medication packet to information on the patient’s MAR.

When performing these three checks, the nurse should ensure this is the right medication, right patient, right dosage, right route, and right time. See Figure 15.9[23] for an image of the nurse performing patient identification prior to administering the medication. The sixth right, correct documentation, should be done immediately after the medication is administered to the patient to avoid an error from another nurse inadvertently administering the dose a second time. These six rights completed three times have greatly reduced medication errors.

As discussed earlier, other rights to consider during this process are as follows:

- Is the patient receiving this medication for the right reason?

- Have the right assessments been performed prior to giving the medication?

- Has the patient also received the right education regarding the medications?

- Is the patient exhibiting the right response to the medication?

- Is the patient refusing to take the medication? Patients have the right to refuse medication. The patient’s refusal and any education or explanation provided related to the attempt to administer the medication should be documented by the nurse and the prescribing provider should be notified.

![]()

- Listen to the patient if they verbalize any concerns about medications. Explore their concerns, verify the order, and/or discuss their concerns with the prescribing provider before administering the medication to avoid a potential medication error.

- If a pill falls on the floor, it is contaminated and should not be administered. Dispose the medication according to agency policy.

- Be aware of absorption considerations of the medications you are administering. For example, certain medications such as levothyroxine should be administered on an empty stomach because food and other medications will affect its absorption.

- Nurses are often the first to notice when a patient has difficulty swallowing. If you notice a patient coughs immediately after swallowing water or has a “gurgling” sound to their voice, do not administer any medications, food, or fluid until you have reported your concerns to the heath care provider. A swallow evaluation may be needed, and the route of medication may need to be changed from oral to another route to avoid aspiration.

- If your patient has a nothing by mouth (NPO) order, verify if this includes all medications. This information may be included on the MAR or the orders, and if not, verify this information with the provider. Some medications, such as diabetes medication, may be given with a sip of water in some situations where the patient has NPO status.

- If the route of administration is not accurately listed on the MAR, contact the prescribing provider before administering the medication. For example, a patient may have a PEG tube, but the medication is erroneously listed as “PO” on the order.

For more information regarding classes of medications, administration considerations, and adverse effects to monitor, visit Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

For information about specific medications, visit DailyMed, a current, evidence-based medication reference.

Special Considerations for Administering Controlled Substances

Controlled substances, also called Scheduled Medications, are kept in a locked system and accounted for using a checks and balance system. Removal of a controlled substance from a medication dispensing system must be verified and documented by a second nurse witness. Removal of a controlled substance from a medication cart needs to be documented on an additional controlled substance record with the patient’s name, the actual amount of substance given, the time it was given, associated pre-assessment data, and the name of the nurse administering the controlled substance.

Controlled substances stored in locked areas of medication carts must also be counted at every shift change by two nurses and then compared to the controlled substance administration record. If the count does not match the documentation record, the discrepancy must be reported immediately according to agency policy.

Additionally, if a partial dose of a controlled substance is administered, the remainder of the substance must be discarded in front of another nurse witness to document the event. This process is called “wasting.” Follow agency policy regarding wasting of controlled substances.

These additional safety measures help to prevent drug diversion, the use of a prescription medication for other than its intended purpose.

For more information about scheduled medications, drug diversion, and substance abuse in health care personnel, visit the “Legal/Ethical” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Oral Medication Administration

Most medications are administered orally because it is the most convenient and least invasive route for the patient. Medication given orally has a slower onset, typically about 30-60 minutes. Prior to oral administration of medications, ensure the patient has no contraindications to receiving oral medication, is able to swallow, and is not on gastric suction. If the patient has difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), tablets are typically crushed and placed in a substance like applesauce or pudding for easier swallowing (based on the patient’s prescribed diet). However, it is important to verify that a tablet may be crushed by consulting a drug reference or a pharmacist. For example, medications such as enteric-coated tablets, capsules, and sustained-release or long-acting drugs should never be crushed because doing so will affect the intended action of the medication. In this event, the provider must be contacted for a change in route.[24]

View the ISMP Do Not Crush List.

Position the patient receiving oral medication in an upright position to decrease the risk of aspiration. Patients should remain in this position for 30 minutes after medication administration, if possible. If a patient is unable to sit, assist them into a side-lying position. See Figure 15.10[25] for an image of a nurse positioning the patient in an upright position prior to medication administration. Offer a glass of water or other oral fluid (that is not contraindicated with the medication) to ease swallowing and improve absorption and dissolution of the medication, taking any fluid restrictions into account.[26]

Remain with the patient until all medication has been swallowed before documenting to verify the medication has been administered.[27]

If any post-assessments are required, follow up in the appropriate time frame. For example, when administering oral pain medication, follow up approximately 30 minutes to an hour after medication is given to ensure effective pain relief.

If medication is given sublingual (under the tongue) or buccal (between the cheek and gum), the mouth should be moist. Offering the patient a drink of water prior to giving the medication can help with absorption. Instruct the patient to allow the medication to completely dissolve and reinforce the importance of not swallowing or chewing the medication.

Liquid medications are available in multidose vials or single-dose containers. It may be necessary to shake liquid medications if they are suspensions prior to pouring. Make sure the label is clearly written and easy to read. When pouring a liquid medication, it is ideal to place the label in the palm of your hand so if any liquid medication runs down the outside of the bottle it does not blur the writing and make the label unidentifiable. When pouring liquid medication, read the dose at eye level measuring at the meniscus of the poured fluid. Always follow specific agency policy and procedure when administering oral medications.

Rectal Medication Administration

Drugs administered rectally have a faster action than the oral route and a higher bioavailability, meaning a higher amount of effective drug in the bloodstream because it has not been influenced by upper gastrointestinal tract digestive processes. Rectal administration also reduces side effects of some drugs, such as gastric irritation, nausea, and vomiting. Rectal medications may also be prescribed for their local effects in the gastrointestinal system (e.g., laxatives) or their systemic effects (e.g., analgesics when oral route is contraindicated). Rectal medications are contraindicated after rectal or bowel surgery, with rectal bleeding or prolapse, and with low platelet counts.[28]

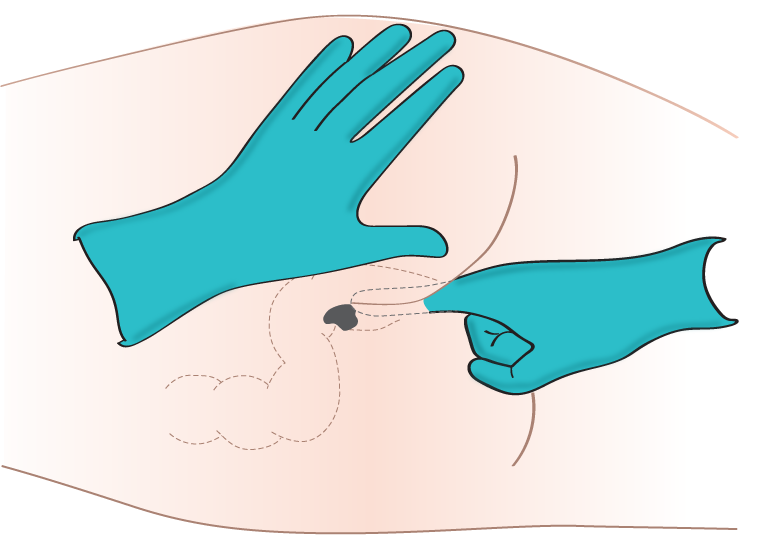

Rectal medications are often formulated as suppositories. Suppositories are small, cone-shaped objects that melt inside the body and release medication. When administering rectal suppositories, the patient should be placed on their left side in the Sims position. See Figure 15.11[29] for an image of patient positioning during rectal medication administration. The suppository and gloved index finger placing the suppository should be lubricated for ease of placement. Suppositories are conical and should be placed into the rectum rounded side first. The suppository should be inserted past the sphincter along the wall of the rectum. After placement, the patient should remain on their side while the medication takes effect. This time period is specific to each medication, but typically is at least 5 minutes. Make sure to avoid placing the suppository into stool. It is also important to monitor for a vasovagal response when placing medications rectally. A vasovagal response can occur when the vagus nerve is stimulated, causing the patient’s blood pressure and heart rate to drop, and creating symptoms of dizziness and perspiration. Sometimes the patient can faint or even have a seizure. Patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias should not be administered rectal suppositories due to the potential for a vasovagal response. Always follow agency policy and procedure when administering rectal medications.[30],[31]

Another type of rectal medication is an enema. An enema is the administration of a substance in liquid form into the rectum. Many enemas are formulated in disposable plastic containers. Warming the solution to body temperature prior to administration may be beneficial because cold solution can cause cramping. It is also helpful to encourage the patient to empty their bladder prior to administration to reduce feelings of discomfort. Place an incontinence pad under the patient and position them on their left side in the Sims position. Lubricate the nozzle of the container and expel air. Insert the lubricated nozzle into the rectum slowly and gently expel the contents into the rectum. Ask the patient to retain the enema based on manufacturer’s recommendations.

Enteral Tube Medication Administration

Medication is administered via an enteral tube when the patient is unable to orally swallow medication. Medications given through an enteral feeding tube (nasogastric, nasointestinal, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy {PEG}, or jejunostomy {J} tube) should be in liquid form whenever possible to avoid clogging the tube. If a liquid form is not available, medications that are safe to crush should be crushed finely and dissolved in water to keep the tube from becoming clogged. If a medication is not safe to crush, the prescribing provider should be notified and a prescription for alternative medication obtained. Capsules should be opened and emptied into liquid as indicated prior to administration, and liquids should be administered at room temperature. Keep in mind that some capsules are time-released and should not be opened. In this case, contact the provider for a change in order.[32],[33]

As always, follow agency policy for this medication administration procedure. Position the patient to at least 30 degrees and in high Fowler’s position when feasible. If gastric suctioning is in place, turn off the suctioning. See Figure 15.12[34] for an image of a nurse positioning the patient prior to administration of medications via a PEG tube. Follow the tube to the point of entry into the patient to ensure you are accessing the correct tube.[35],[36]

Prior to medication administration, verify tube placement. Placement is initially verified immediately after the tube is placed with an X-ray, and the nurse should verify these results. Additionally, bedside placement is verified by the nurse before every medication pass. There are multiple evidence-based methods used to check placement. One method includes aspirating tube contents with a 60-mL syringe and observing the fluid. Fasting gastric secretions appear grassy-green, brown, or clear and colorless, whereas secretions from a tube that has perforated the pleural space typically have a pale yellow serous appearance. A second method used to verify placement is to measure the pH of aspirate from the tube. Fasting gastric pH is usually 5 or less, even in patients receiving gastric acid inhibitors. Fluid aspirated from a tube in the pleural space typically has a pH of 7 or higher.[37],[38] Note that installation of air into the tube while listening over the stomach with a stethoscope is no longer considered a safe method to check tube placement according to evidence-based practices.[39]

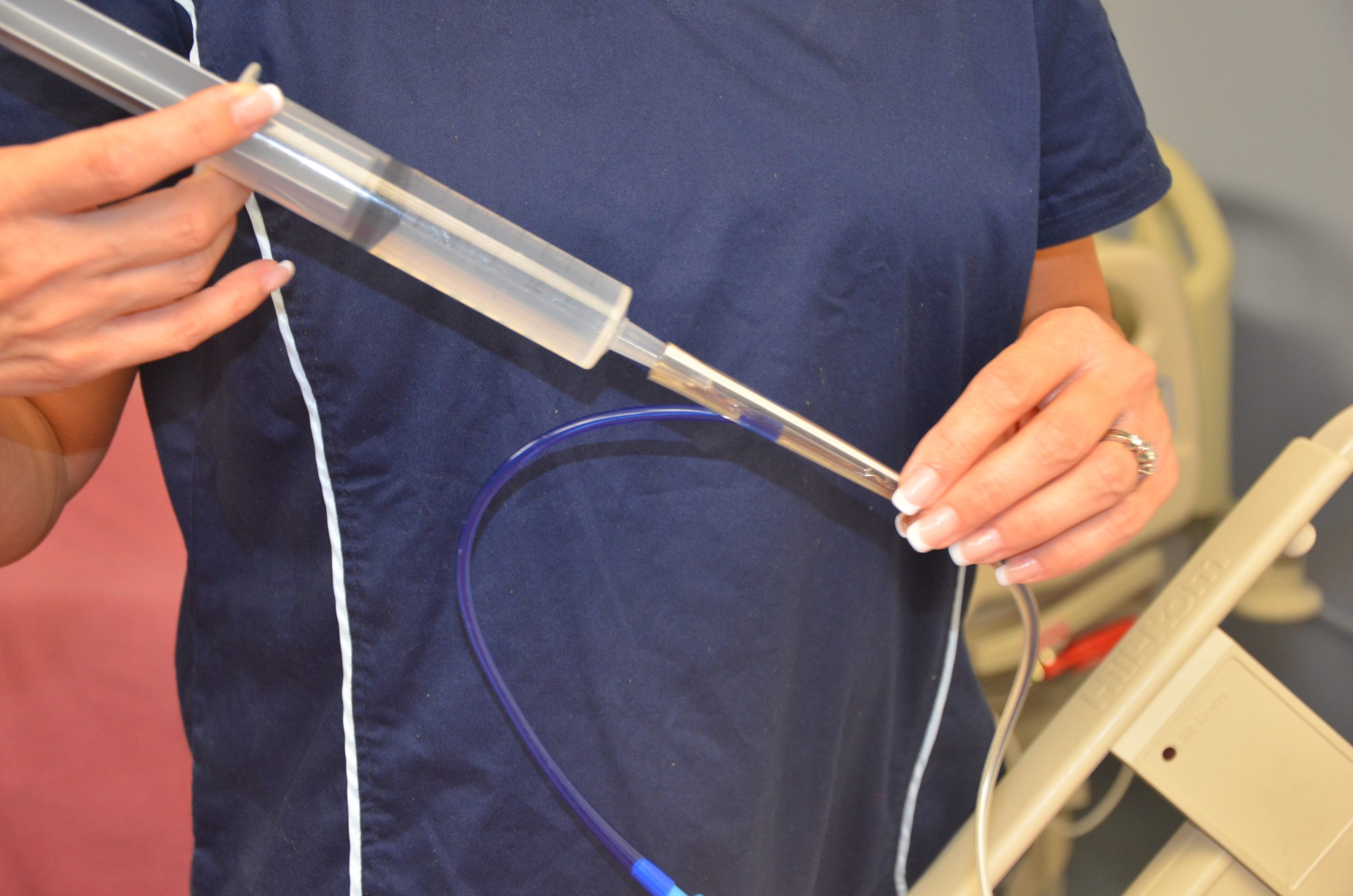

After tube placement is checked, a clean 60-mL syringe is used to flush the tube with a minimum of 15 mL of water (5-10 mL for children) before administering the medication. Follow agency policy regarding flushing amount. Liquid medication, or appropriately crushed medication dissolved in water, is administered one medication at a time. Medication should not be mixed because of the risks of physical and chemical incompatibilities, tube obstruction, and altered therapeutic drug responses. Between each medication, the tube is flushed with 15 mL of water, keeping in mind the patient’s fluid volume status. After the final medication is administered, the tube is flushed with 15 mL of water. The tube is then clamped, or if the patient is receiving tube feeding, it can be restarted. If the patient is receiving gastric suctioning, it can be restarted 30 minutes after medication administration.[40],[41],[42] See Figure 15.13[43] for an image of a nurse administering medication via an enteral tube.

Special considerations during this procedure include the following:

- If the patient has fluid restrictions, the amount of fluid used to flush the tube between each medication may need to be modified to avoid excess fluid intake.

- If the tube is attached to suctioning, the suctioning should be left off for 20 to 30 minutes after the medication is given to promote absorption of the medication.

- If the patient is receiving tube feedings, review information about the drugs that are being administered. If they cannot be taken with food or need to be taken on an empty stomach, the tube feeding running time will need to be adjusted.

- Be sure to document the amount of water used to flush the tube during the medication pass on the fluid intake record.

- If the patient has a chronic illness or is immunosuppressed, sterile water is suggested for use of mixing and flushing instead of tap water.

- Enteric-coated medications and other medications on the “Do Not Crush List” should not be crushed for this procedure. Instead, the prescribing provider must be notified and an order for a different form of the medication must be obtained.

- If the tube becomes clogged, attempt to flush it with water. If unsuccessful, notify the provider and a pancreatic enzyme solution or kit may be ordered before a new tube is placed.[44]

View a supplementary YouTube video on Crushing Medications[45]

Preventing Medication Errors

Medication errors can occur at various stages of the medication administration process, beginning with the prescribing provider, to the pharmacist preparing the medication, to the pharmacy technician stocking the medication, to the nurse administering the medication. Medication errors are most common at the ordering or prescribing stage. Typical errors include the prescribing provider writing the wrong medication, wrong route or dose, or the wrong frequency. These ordering errors account for almost 50% of medication errors. Data shows that nurses and pharmacists identify anywhere from 30% to 70% of medication-ordering errors.[46]

One of the major causes for medication errors is a distraction. Nearly 75% of medication errors have been attributed to this cause.[47] To minimize distractions, hospitals have introduced measures to reduce medication errors. For example, some hospitals set a “no-interruption zone policy” during medication dispensing and preparation and ask health care team members to only disrupt the medication administration process for emergencies. To reduce medication errors, agencies are also adopting many initiatives developed by the World Health Organization (WHO),[48] Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), Institute of Medicine (IOM),[49] and several other organizations. Initiatives include measures such as avoiding error-prone abbreviations, being aware of commonly confused medication names, and instituting additional safeguards for high-alert medications. Student nurses must also be aware of conditions that may contribute to making a medication error during their clinical courses. Read more about initiatives to prevent medication errors in the boxes and videos provided below.

For more information about preventing medication errors as a student nurse, visit IMSP’s Error-Prone Conditions that Lead to Student Nurse-Related Errors.

When you prepare to administer medications to your patients during clinical, your instructor will ask you questions to ensure safe medication administration. View a supplementary YouTube video of a nursing instructor asking a student typical medication questions.

View a supplementary YouTube video from the WHO on Administering Medications Without Harm[50]

Reporting Medication Errors

Despite multiple initiatives that have been instituted to prevent medication errors, including properly checking the rights of medication administration, medication errors happen. Examples of common errors include administering the wrong dose or an unsafe dose, giving medication to the wrong patient, administering medication by the wrong route or at the incorrect rate, and giving a drug that is expired. If a medication error occurs, the nurse must follow specific steps of reporting according to agency policy. In the past when medication errors occurred, the individual who caused it was usually blamed for the mishap and disciplinary action resulted. However, this culture of blame has shifted, and many medication errors by well-trained and careful nurses and other health care professions are viewed as potential symptoms of a system-wide problem. This philosophy is referred to as an institution’s safety culture. Thus, rather than focusing on disciplinary action, agencies are now trying to understand how the system failed causing the error to occur. This approach is designed to introduce safeguards at every level so that a mistake can be caught before the drug is given to the patient, which is often referred to as a “near miss.” For an agency to effectively institute a safety culture, all medication errors and near misses must be reported.

When a medication error occurs, the nurse’s first response should be to immediately monitor the patient’s condition and watch for any side effects from the medication. Secondly, the nurse must notify the nurse manager and prescribing provider of the error. The provider may provide additional orders to counteract the medication’s effects or to monitor for potential adverse reactions. In some situations, family members of the patient who are legal guardians or powers of attorney should also be notified. Lastly, a written report should be submitted documenting the incident, often referred to as an incident report. Incident reports are intended to identify if patterns of errors are occurring due to system-wide processes that can be modified to prevent future errors.

For more information about safety culture, visit the following section of the “Legal/Ethical” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Life Span Considerations

Children

It can be difficult to persuade children to take medications. It is often helpful for medications to be prescribed in liquid or chewable form. For example, droppers are used for infants or very young children; the medication should be placed between the gum and cheek to prevent aspiration. Mixing medication with soft foods can also be helpful to encourage the child to swallow medications, but it is best to avoid mixing the medication with a staple food in the child’s diet because of potential later refusal of the food associated with medication administration. It can be helpful to offer the child a cool item, such as a popsicle or frozen fruit bar, prior to medication administration to numb the child’s tongue and decrease the taste of the medication. Other clinical tips for medication administration include asking the caregiver how the child takes medications at home and mimicking this method or asking the caregiver to administer the medication if the child trusts them more than the nurse. Oral syringes (without needles attached) may be used to administer precise dosages of medication to children. See Figure 15.14[51] of a nurse administering oral medication to a child with an oral syringe. When administering medication with an oral syringe, remember to remove the cap prior to administration because this could be a choking hazard. It is also important to educate the caregiver of the child how to properly administer the medication at the correct dosage at home.

Older Adults

Many older adults have a “polypharmacy,” meaning many medications to keep track of and multiple times these medications need to be taken per day. Nurses should help patients set up a schedule to remember when to take the medications. Organizing medications in medication boxes by day and time is a very helpful strategy. See Figure 15.15[52] of a medication box. Nurses can suggest to patients to have all medications filled at the same pharmacy to avoid drug-drug interactions that can occur when multiple providers are prescribing medications.

Older adults often have difficulty swallowing, so obtaining a prescription for liquid medication or crushing the medication when applicable and placing it in applesauce or pudding is helpful. Allow extra time when administering medication to an older adult to give them time to ask questions and to swallow multiple pills. Monitor for adverse effects and drug interactions in older adults, who are often taking multiple medications and may have preexisting kidney or liver dysfunction.

Be sure to address the economic needs of an older adult as it relates to their medications. Medications can be expensive, and many older adults live on a strict budget. Nurses often advocate for less expensive alternatives for patients, such as using a generic brand instead of a name brand or a less expensive class of medication. Be aware that an older adult with financial concerns may try to save money by not taking medications as frequently as prescribed. Also, the older adult may “feel good” on their medications and think they don’t need to monitor or take medications because they are “cured.” Reinforce that “feeling good” usually means the medication is working as prescribed and should continue to be taken. Finally, empower patients to take control of managing their health by providing education and ongoing support.

- NCSBN.(2018). 2019 NCLEX-RN test plan. https://www.ncsbn.org/2019_RN_TestPlan-English.pdf ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Tariq, Vashisht, Sinha, and Scherbak and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- Vera, M. (2020, June 30). The 10 rights of drug administration. Nurselabs. https://nurseslabs.com/10-rs-rights-of-drug-administration/ ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp.250-251,257-258. ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- “Patient Identification.png” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Wrist Identification Band.jpg” by Whoisjohngalt is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). National patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/ ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- “MAR.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 14). Memo: Requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and post-operative care of patients receiving IV opioids. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf ↵

- NCSBN. (2018). 2019 NCLEX-RN test plan. https://www.ncsbn.org/2019_RN_TestPlan-English.pdf ↵

- “Unit Dose Packaging.jpg” and “Unit Dose Label.jpg” by Deanna Hoyord, Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Med Cart 1_313A0209.jpg” and “Med Cart Drawer._313A0224.jpg” by Deanna Hoyord, Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Medication_blister_pack_2.jpg” by Sprinno is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “MMI medication cart.JPG” by BrokenSphere is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “DSC_17601-150x150.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-1-safe-medication-adminstration/ ↵

- “Book-pictures-2015-430-150x150.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0.. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-1-safe-medication-adminstration/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “DSC_17631-150x150.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-1-safe-medication-adminstration/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Administering-med-rectally-2.png” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp.250-251, 257-258. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- “degreeLow.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/3-4-positioning-a-patient-in-bed/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- ABoullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T.J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 250-251, 257-258. ↵

- “Administering medication into a gastric tube.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2017, March 22). Crushing medications for tube feeding and oral administration [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/86RzAgHu75U ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Tariq, Vashisht, Sinha, and Scherbak and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Tariq, Vashisht, Sinha, and Scherbak and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- World Health Organization (n.d.). Patient safety. https://www.who.int/patientsafety/medication-safety/technical-reports/en/ ↵

- IOM. Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623 ↵

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017, October 6). WHO: Medication without harm [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/MWUM7LIXDeA ↵

- “USMC-080623-M-9467O-024.jpg” by Lance Cpl. Regina A. Ochoa for the United States Marine Corps is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “pills-4005382_960_720.jpg” by Nemo73 is licensed under CC0 ↵

Health care costs impact both macroeconomics (affecting the entire country and society as a whole) and microeconomics (affecting the financial decisions of businesses and individuals). Health care services are funded by several payment models, including federal government programs (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid), private health insurance (typically provided by employers), and self-pay. Payment models also impact services provided by health care agencies, as well as the services and medications available to consumers. Nurses must be aware of these payment models because of the impact on the allocation of resources they need to provide patient care.

Government Funding

Medicare and Medicaid were signed into law in 1965. These programs provide eligible Americans support for their health care needs with taxpayer funding.

Medicare

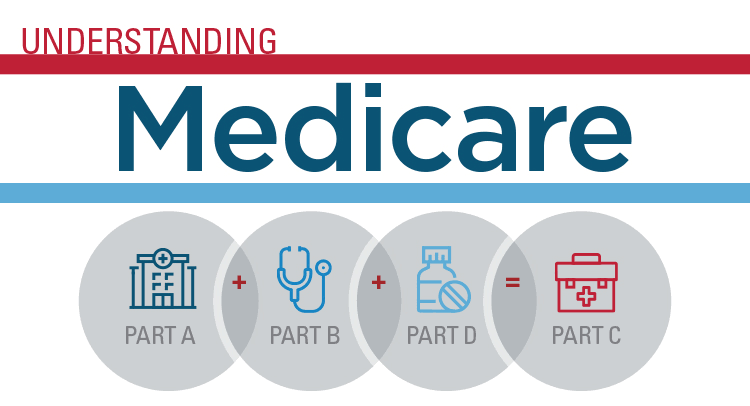

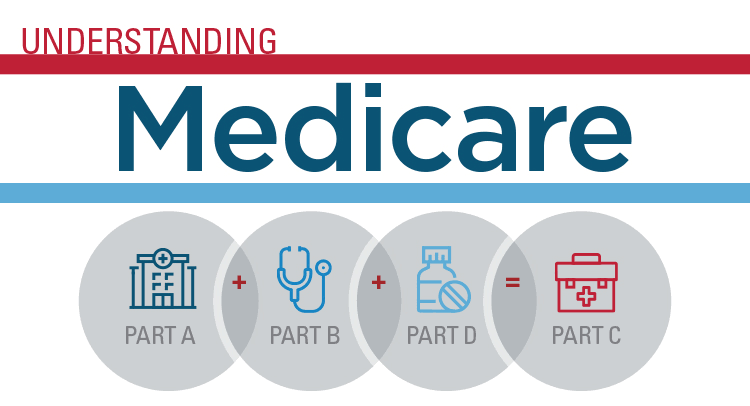

Medicare is a federal health insurance program used by people aged 65 and older, younger individuals with permanent disabilities, and people with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. Medicare coverage has four possible components: Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D.[1] See Figure 8.5[2] for an infographic illustrating Medicare Parts A, B, C, and D.

- Part A (Hospital Insurance): Part A covers patients’ hospital stays, skilled nursing facility care, hospice care, and some home health care. Part A is free for clients if they or their spouse paid Medicare taxes for a specific amount of time while working. If clients are not eligible for free coverage, they can buy it with premiums based on the number of months they paid Medicare taxes.

- Part B (Medical Insurance): Part B covers doctors’ services, outpatient care, medical supplies, and preventative care services. Most people pay a standard premium for Part B.

- Part C (Medicare Advantage Plan): A Medicare Advantage Plan is a health plan choice offered by private companies approved by Medicare, also referred to as "Part C." These plans provide Part A and Part B coverage, and most also include Part D coverage. Medicare Advantage Plans may offer extra coverage, such as vision, hearing, dental, and/or health and wellness programs.

- Part D (Prescription Drug Coverage): Part D helps cover the cost of prescription drugs and vaccinations. To get Medicare drug coverage, clients must enroll in a Medicare-approved plan that offers drug coverage. Different plans vary in cost and what prescription medications they cover, also referred to as a formulary.

Read more about Medicare at medicare.gov.

Medicaid

Medicaid is the largest source of health coverage in the United States. It is a joint federal and state program covering eligible individuals with taxpayer funding. To participate in Medicaid, federal law requires states to cover certain groups of individuals, such as low-income families, qualified pregnant women and children, and individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI). States may choose to cover additional groups, such as individuals receiving home and community-based services and children in foster care who are not otherwise eligible.[3]

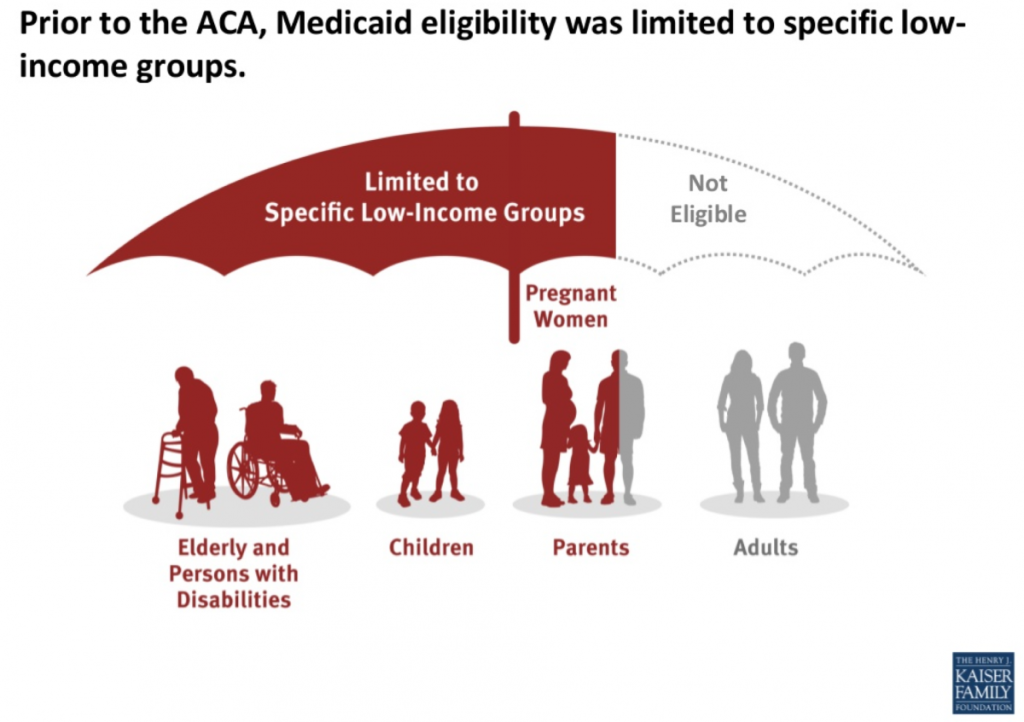

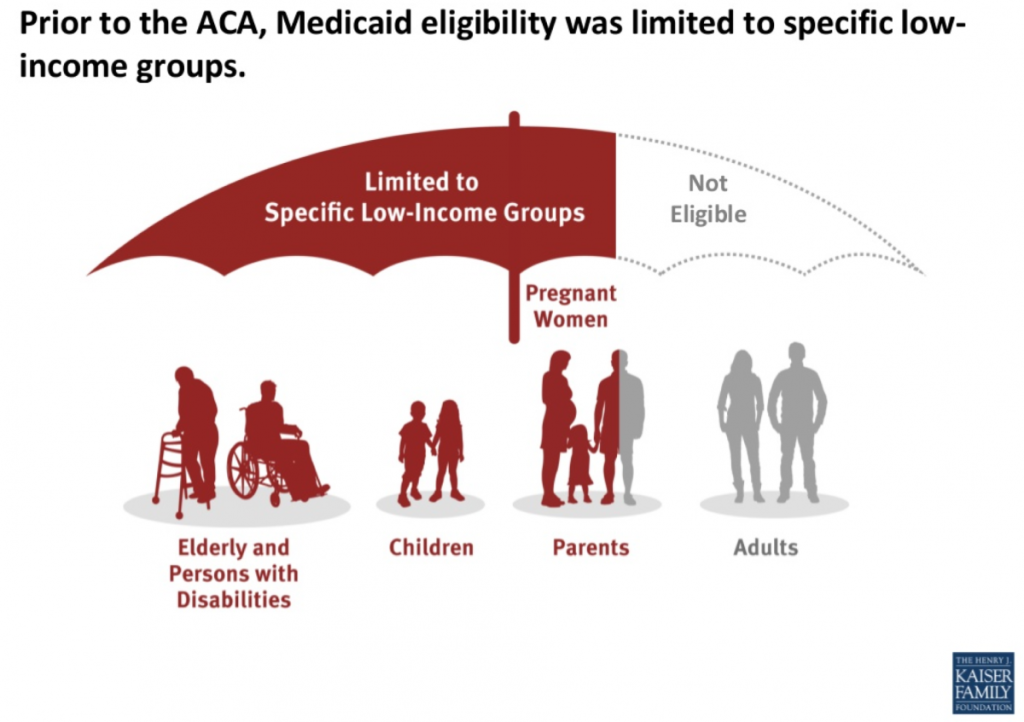

In 2014 the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid to cover all low-income Americans under the age of 65 years and also expanded coverage for children. Due to the individual states’ involvement in Medicaid, coverage of services varies from state to state.[4] See Figure 8.6[5] for an illustration of Medicaid-eligible populations.

Individuals with Medicaid plans have support in paying for a variety of health services, including hospital care, laboratory and diagnostic testing, skilled nursing care, home health services, preventative care, and regular outpatient provider visits.

Other Government Health Funding

There are several other types of health coverage provided by federal and state programs. Read more about these programs in the following box.

Other Federal and State Health Care Funding Programs[6]

- State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): A program designed to help provide coverage for uninsured children whose family income is below average but too high to qualify for Medicaid. The federal government provides matching funds to states for health insurance for these families.

Read more details at InsuredKidsNow.gov.

- Children and Youth With Special Health Care Needs: This program coordinates funding and resources to provide care to people with special health needs.

Read more details at Children With Special Health Care Needs.

- Tricare: This program covers about 9 million active duty and retired military personnel and their families.

Read more details at TRICARE.

- Veterans Health Administration (VHA): This government-operated health care system provides comprehensive health services to eligible military veterans. About 9 million veterans are enrolled.

Read more details at Veterans Health Administration.

- Indian Health Service: This system of government hospitals and clinics provides health services to about 2 million Native Americans living on or near a reservation.

Read more details at Indian Health Service.

- Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) Program: This program allows private insurers to offer insurance plans within guidelines set by the government for the benefit of active and retired federal employees and their survivors.

Read more details at The Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program.

- Refugee Health Promotion Program: This program provides short-term health insurance to newly arrived refugees.

Read more details at Refugee Health Promotion Program (RHP).

Private Insurance

Individuals who are not eligible for government-funded health programs like Medicare or Medicaid can purchase private health insurance. Many individuals with private insurance obtain coverage through their employers’ benefit packages, where the costs for coverage are shared between the employer and the employee. If an individual does not receive health insurance through their employer, they may purchase it from the Marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act.

Read more about obtaining health insurance through the ACA Marketplace at healthcare.gov.

Self-Pay

Some individuals do not have health care coverage provided by their employer, do not qualify for Medicare or Medicaid, and do not elect to purchase health insurance coverage. Instead, these individuals go without coverage and pay health care costs as they arise. See Figure 8.7[7] for a graph illustrating the decreasing numbers of uninsured consumers in the United States over the past several decades. Unfortunately, due to the skyrocketing cost of health care services, significant bills can accrue from a single serious illness or traumatic injury that can put consumers without health care coverage in jeopardy of bankruptcy. Nurses can assist uninsured individuals to better understand coverage options by referring them to a case manager or social worker.

Types of Insurance Coverage

Health insurance plans have different types of coverage. Common types of health insurance plans are HMO, PPO, POS, HDHP, or HSA.

- Health Maintenance Organization (HMO): HMO plans usually have the lowest monthly cost for coverage (i.e., premium) but also have a smaller network of providers and hospitals where the consumer may receive insured care. This means the consumer is restricted to receive care only from specific providers and health facilities. Many HMOs also require the consumer to see their primary care provider to request a referral to see a specialist, which may or may not be approved by the HMO. Additionally, many tests, procedures, surgeries, and medications require “preauthorization” by the HMO, which may or may not be approved. Due to these restrictions, consumers may find they sacrifice flexibility and choice for lower cost of coverage.[8]

- Preferred Provider Organization (PPO): PPO plans are typically less restrictive than HMOs. PPOs typically include “in-network” providers and hospitals where costs are lower if care is received in-network, but consumers also have a choice to receive “out-of-network” care at a higher cost. Referrals from a primary care provider are not generally required in a PPO. The monthly premium for a PPO plan is typically higher than an HMO plan, but PPOs allow more consumer flexibility in choosing their health care providers.[9]

- Point of Service (POS): POS plans are a combination of HMO and PPO plans, where the insured consumer has a preferred provider network to receive health care services at a lower cost, but also has the flexibility to receive care outside of their network. When consumers venture outside of the network, they often have to pay a significant share of the cost.[10]

- High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP): HDHP plans are often popular for younger individuals without chronic health care needs who spend little on health care but require coverage in the event a high-cost injury or illness occurs. HDHPs typically have lower monthly premiums but require the individual to pay more upfront for health care services before the coverage kicks in (referred to as a “deductible”). Individuals with an HDHP often have an associated Health Savings Account (HSA). HDHPs have grown in popularity as more employers offer these plans in an attempt to contain health care costs by shifting more cost-sharing to the consumer.

- Health Savings Account (HSA): An HSA is a special account reserved for eligible medical expenses with strict usage rules. Money placed in an HSA can often be deducted from a consumer’s pretaxed pay, resulting in tax savings. In addition to purchasing items like glasses, contacts, and over-the-counter medications, HSAs can often be used to pay for deductibles. Some employers deposit a specified amount of money into an employee’s HSA every year to help reimburse high deductibles.

Deductible and Copays

Costs paid by an insured individual are commonly referred to as “out-of-pocket expenses.” Out-of-pocket expenses include deductibles and co-pays. A deductible is the amount of money a consumer pays before the health care plan pays anything. Deductibles generally apply per person per calendar year. Typically, a PPO has higher premiums but lower deductibles than a HDHP.

A co-pay is a flat fee the consumer pays at the time of the health care service. For example, when visiting a primary provider, the consumer may pay $20 to the provider at each visit as a co-pay. Some health care plans require co-pays in addition to deductibles.

Nursing Considerations

Understanding a client’s health insurance coverage is important because it may impact their choice of health services and their ability to purchase medications and other supplies. Additionally, if a client is self-pay, it is helpful to refer them to resources such as case managers, social workers, or the financial department of the agency. These resources can assist them in obtaining affordable health care coverage through the ACA Marketplace or other government programs.

Health care costs impact both macroeconomics (affecting the entire country and society as a whole) and microeconomics (affecting the financial decisions of businesses and individuals). Health care services are funded by several payment models, including federal government programs (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid), private health insurance (typically provided by employers), and self-pay. Payment models also impact services provided by health care agencies, as well as the services and medications available to consumers. Nurses must be aware of these payment models because of the impact on the allocation of resources they need to provide patient care.

Government Funding

Medicare and Medicaid were signed into law in 1965. These programs provide eligible Americans support for their health care needs with taxpayer funding.

Medicare

Medicare is a federal health insurance program used by people aged 65 and older, younger individuals with permanent disabilities, and people with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. Medicare coverage has four possible components: Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D.[11] See Figure 8.5[12] for an infographic illustrating Medicare Parts A, B, C, and D.

- Part A (Hospital Insurance): Part A covers patients’ hospital stays, skilled nursing facility care, hospice care, and some home health care. Part A is free for clients if they or their spouse paid Medicare taxes for a specific amount of time while working. If clients are not eligible for free coverage, they can buy it with premiums based on the number of months they paid Medicare taxes.

- Part B (Medical Insurance): Part B covers doctors’ services, outpatient care, medical supplies, and preventative care services. Most people pay a standard premium for Part B.

- Part C (Medicare Advantage Plan): A Medicare Advantage Plan is a health plan choice offered by private companies approved by Medicare, also referred to as "Part C." These plans provide Part A and Part B coverage, and most also include Part D coverage. Medicare Advantage Plans may offer extra coverage, such as vision, hearing, dental, and/or health and wellness programs.

- Part D (Prescription Drug Coverage): Part D helps cover the cost of prescription drugs and vaccinations. To get Medicare drug coverage, clients must enroll in a Medicare-approved plan that offers drug coverage. Different plans vary in cost and what prescription medications they cover, also referred to as a formulary.

Read more about Medicare at medicare.gov.

Medicaid

Medicaid is the largest source of health coverage in the United States. It is a joint federal and state program covering eligible individuals with taxpayer funding. To participate in Medicaid, federal law requires states to cover certain groups of individuals, such as low-income families, qualified pregnant women and children, and individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI). States may choose to cover additional groups, such as individuals receiving home and community-based services and children in foster care who are not otherwise eligible.[13]

In 2014 the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid to cover all low-income Americans under the age of 65 years and also expanded coverage for children. Due to the individual states’ involvement in Medicaid, coverage of services varies from state to state.[14] See Figure 8.6[15] for an illustration of Medicaid-eligible populations.

Individuals with Medicaid plans have support in paying for a variety of health services, including hospital care, laboratory and diagnostic testing, skilled nursing care, home health services, preventative care, and regular outpatient provider visits.

Other Government Health Funding

There are several other types of health coverage provided by federal and state programs. Read more about these programs in the following box.

Other Federal and State Health Care Funding Programs[16]

- State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): A program designed to help provide coverage for uninsured children whose family income is below average but too high to qualify for Medicaid. The federal government provides matching funds to states for health insurance for these families.

Read more details at InsuredKidsNow.gov.

- Children and Youth With Special Health Care Needs: This program coordinates funding and resources to provide care to people with special health needs.

Read more details at Children With Special Health Care Needs.

- Tricare: This program covers about 9 million active duty and retired military personnel and their families.

Read more details at TRICARE.

- Veterans Health Administration (VHA): This government-operated health care system provides comprehensive health services to eligible military veterans. About 9 million veterans are enrolled.

Read more details at Veterans Health Administration.

- Indian Health Service: This system of government hospitals and clinics provides health services to about 2 million Native Americans living on or near a reservation.

Read more details at Indian Health Service.

- Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) Program: This program allows private insurers to offer insurance plans within guidelines set by the government for the benefit of active and retired federal employees and their survivors.

Read more details at The Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program.

- Refugee Health Promotion Program: This program provides short-term health insurance to newly arrived refugees.

Read more details at Refugee Health Promotion Program (RHP).

Private Insurance

Individuals who are not eligible for government-funded health programs like Medicare or Medicaid can purchase private health insurance. Many individuals with private insurance obtain coverage through their employers’ benefit packages, where the costs for coverage are shared between the employer and the employee. If an individual does not receive health insurance through their employer, they may purchase it from the Marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act.

Read more about obtaining health insurance through the ACA Marketplace at healthcare.gov.

Self-Pay

Some individuals do not have health care coverage provided by their employer, do not qualify for Medicare or Medicaid, and do not elect to purchase health insurance coverage. Instead, these individuals go without coverage and pay health care costs as they arise. See Figure 8.7[17] for a graph illustrating the decreasing numbers of uninsured consumers in the United States over the past several decades. Unfortunately, due to the skyrocketing cost of health care services, significant bills can accrue from a single serious illness or traumatic injury that can put consumers without health care coverage in jeopardy of bankruptcy. Nurses can assist uninsured individuals to better understand coverage options by referring them to a case manager or social worker.

Types of Insurance Coverage

Health insurance plans have different types of coverage. Common types of health insurance plans are HMO, PPO, POS, HDHP, or HSA.

- Health Maintenance Organization (HMO): HMO plans usually have the lowest monthly cost for coverage (i.e., premium) but also have a smaller network of providers and hospitals where the consumer may receive insured care. This means the consumer is restricted to receive care only from specific providers and health facilities. Many HMOs also require the consumer to see their primary care provider to request a referral to see a specialist, which may or may not be approved by the HMO. Additionally, many tests, procedures, surgeries, and medications require “preauthorization” by the HMO, which may or may not be approved. Due to these restrictions, consumers may find they sacrifice flexibility and choice for lower cost of coverage.[18]

- Preferred Provider Organization (PPO): PPO plans are typically less restrictive than HMOs. PPOs typically include “in-network” providers and hospitals where costs are lower if care is received in-network, but consumers also have a choice to receive “out-of-network” care at a higher cost. Referrals from a primary care provider are not generally required in a PPO. The monthly premium for a PPO plan is typically higher than an HMO plan, but PPOs allow more consumer flexibility in choosing their health care providers.[19]

- Point of Service (POS): POS plans are a combination of HMO and PPO plans, where the insured consumer has a preferred provider network to receive health care services at a lower cost, but also has the flexibility to receive care outside of their network. When consumers venture outside of the network, they often have to pay a significant share of the cost.[20]

- High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP): HDHP plans are often popular for younger individuals without chronic health care needs who spend little on health care but require coverage in the event a high-cost injury or illness occurs. HDHPs typically have lower monthly premiums but require the individual to pay more upfront for health care services before the coverage kicks in (referred to as a “deductible”). Individuals with an HDHP often have an associated Health Savings Account (HSA). HDHPs have grown in popularity as more employers offer these plans in an attempt to contain health care costs by shifting more cost-sharing to the consumer.

- Health Savings Account (HSA): An HSA is a special account reserved for eligible medical expenses with strict usage rules. Money placed in an HSA can often be deducted from a consumer’s pretaxed pay, resulting in tax savings. In addition to purchasing items like glasses, contacts, and over-the-counter medications, HSAs can often be used to pay for deductibles. Some employers deposit a specified amount of money into an employee’s HSA every year to help reimburse high deductibles.

Deductible and Copays

Costs paid by an insured individual are commonly referred to as “out-of-pocket expenses.” Out-of-pocket expenses include deductibles and co-pays. A deductible is the amount of money a consumer pays before the health care plan pays anything. Deductibles generally apply per person per calendar year. Typically, a PPO has higher premiums but lower deductibles than a HDHP.

A co-pay is a flat fee the consumer pays at the time of the health care service. For example, when visiting a primary provider, the consumer may pay $20 to the provider at each visit as a co-pay. Some health care plans require co-pays in addition to deductibles.

Nursing Considerations

Understanding a client’s health insurance coverage is important because it may impact their choice of health services and their ability to purchase medications and other supplies. Additionally, if a client is self-pay, it is helpful to refer them to resources such as case managers, social workers, or the financial department of the agency. These resources can assist them in obtaining affordable health care coverage through the ACA Marketplace or other government programs.

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

3 cm x 2 cm Stage 3 pressure injury on the patient’s sacrum. Dark pink wound base with no signs of infection. Cleansed with normal saline spray and hydrocolloid dressing applied.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

3 cm x 2 cm x 1 cm Stage 3 pressure injury on sacrum. Wound base dark red with yellow-green drainage present. Removed 4 x 4 dressing has 5 cm diameter ring of drainage present. Periwound skin red, warm, tender to palpation. Temperature 36.8⁰ C. Dr. Smith notified of all the above. Wound culture order received. Wound cleansed with normal saline spray, wound culture collected, hydrocolloid dressing applied.

Wound therapy is often prescribed by a multidisciplinary team that can include the provider, a wound care nurse, a dietician, and the bedside nurse who performs dressing changes. Topical dressings should be selected that create an environment conducive to healing the specific type of wound and its causes. It is important to perform the following actions when providing wound care:

- Prevent and manage infection

- Cleanse the wound

- Debride the wound

- Maintain appropriate moisture in the wound

- Control odor

- Manage wound pain

- Consider the big picture[21]

Each of these objectives is further discussed in the following subsections.

Prevent and Manage Infection

One of the primary goals of wound dressings is to protect the wound base from bacteria and contaminants (i.e., urine and feces). If new signs of infection are present during a wound dressing change, wound swabs should be taken according to agency policy and the need for a wound culture and possible antibiotic therapy discussed with the primary provider.[22]

Silver sulfadiazine is an example of a common topical antibiotic prescribed for wounds. Topical antibiotics are covered with a secondary dressing.[23]

Cleanse the Wound