14.4 Integumentary Assessment

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Now that we have reviewed the anatomy of the integumentary system and common integumentary conditions, let’s review the components of an integumentary assessment. The standard for documentation of skin assessment is within 24 hours of admission to inpatient care. Skin assessment should also be ongoing in inpatient and long-term care.[1]

A routine integumentary assessment by a registered nurse in an inpatient care setting typically includes inspecting overall skin color, inspecting for skin lesions and wounds, and palpating extremities for edema, temperature, and capillary refill.[2]

Subjective Assessment

Begin the assessment by asking focused interview questions regarding the integumentary system. Itching is the most frequent complaint related to the integumentary system. See Table 14.4a for sample interview questions.

Table 14.4a Focused Interview Questions for the Integumentary System

| Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Are you currently experiencing any skin symptoms such as itching, rashes, or an unusual mole, lump, bump, or nodule?[3] | Use the PQRSTU method to gain additional information about current symptoms. Read more about the PQRSTU method in the “Health History” chapter. |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a condition such as acne, eczema, skin cancer, pressure injuries, jaundice, edema, or lymphedema? | Please describe. |

| Are you currently using any prescription or over-the-counter medications, creams, vitamins, or supplements to treat a skin, hair, or nail condition? | Please describe. |

Objective Assessment

There are five key areas to note during a focused integumentary assessment: color, skin temperature, moisture level, skin turgor, and any lesions or skin breakdown. Certain body areas require particular observation because they are more prone to pressure injuries, such as bony prominences, skin folds, perineum, between digits of the hands and feet, and under any medical device that can be removed during routine daily care.[4]

Inspection

Color

Inspect the color of the patient’s skin and compare findings to what is expected for their skin tone. Note a change in color such as pallor (paleness), cyanosis (blueness), jaundice (yellowness), or erythema (redness). Note if there is any bruising (ecchymosis) present.

Scalp

If the patient reports itching of the scalp, inspect the scalp for lice and/or nits.

Lesions and Skin Breakdown

Note any lesions, skin breakdown, or unusual findings, such as rashes, petechiae, unusual moles, or burns. Be aware that unusual patterns of bruising or burns can be signs of abuse that warrant further investigation and reporting according to agency policy and state regulations.

Auscultation

Auscultation does not occur during a focused integumentary exam.

Palpation

Palpation of the skin includes assessing temperature, moisture, texture, skin turgor, capillary refill, and edema. If erythema or rashes are present, it is helpful to apply pressure with a gloved finger to further assess for blanching (whitening with pressure).

Temperature, Moisture, and Texture

Fever, decreased perfusion of the extremities, and local inflammation in tissues can cause changes in skin temperature. For example, a fever can cause a patient’s skin to feel warm and sweaty (diaphoretic). Decreased perfusion of the extremities can cause the patient’s hands and feet to feel cool, whereas local tissue infection or inflammation can make the localized area feel warmer than the surrounding skin. Research has shown that experienced practitioners can palpate skin temperature accurately and detect differences as small as 1 to 2 degrees Celsius. For accurate palpation of skin temperature, do not hold anything warm or cold in your hands for several minutes prior to palpation. Use the palmar surface of your dominant hand to assess temperature.[5] While assessing skin temperature, also assess if the skin feels dry or moist and the texture of the skin. Skin that appears or feels sweaty is referred to as being diaphoretic.

Capillary Refill

The capillary refill test is a test done on the nail beds to monitor perfusion, the amount of blood flow to tissue. Pressure is applied to a fingernail or toenail until it turns white, indicating that the blood has been forced from the tissue under the nail. This whiteness is called blanching. Once the tissue has blanched, remove pressure. Capillary refill is defined as the time it takes for color to return to the tissue after pressure has been removed that caused blanching. If there is sufficient blood flow to the area, a pink color should return within 2 seconds after the pressure is removed.[6]

View the Cardiovascular Assessment Part Two | Capillary Refill Test YouTube video for a demonstration of capillary refill.[7]

Skin Turgor

Skin turgor may be included when assessing a patient’s hydration status, but research has shown it is not a good indicator. Skin turgor is the skin’s elasticity. Its ability to change shape and return to normal may be decreased when the patient is dehydrated. To check for skin turgor, gently grasp skin on the patient’s lower arm between two fingers so that it is tented upwards, and then release. Skin with normal turgor snaps rapidly back to its normal position, but skin with poor turgor takes additional time to return to its normal position.[8] Skin turgor is not a reliable method to assess for dehydration in older adults because they have decreased skin elasticity, so other assessments for dehydration should be included.[9]

Edema

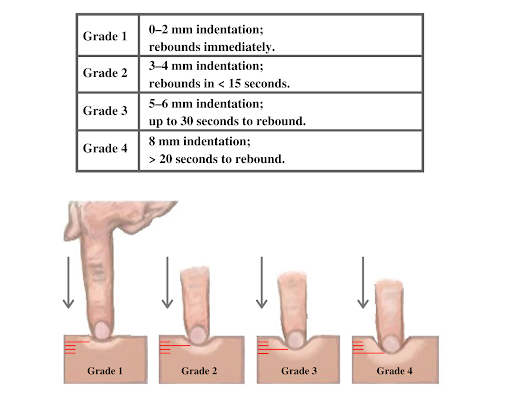

If edema is present on inspection, palpate the area to determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting. Press on the skin to assess for indentation, ideally over a bony structure, such as the tibia. If no indentation occurs, it is referred to as nonpitting edema. If indentation occurs, it is referred to as pitting edema. See Figure 14.22[10] for an image demonstrating pitting edema. If pitting edema is present, document the depth of the indention and how long it takes for the skin to rebound back to its original position. The indentation and time required to rebound to the original position are graded on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1+ indicates a barely detectable depression with immediate rebound, and 4+ indicates a deep depression with a time lapse of over 20 seconds required to rebound. See Figure 14.23[11] for an illustration of grading edema.

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults

Older adults have several changes associated with aging that are apparent during assessment of the integumentary system. They often have cardiac and circulatory system conditions that cause decreased perfusion, resulting in cool hands and feet. They have decreased elasticity and fragile skin that often tears more easily. The blood vessels of the dermis become more fragile, leading to bruising and bleeding under the skin. The subcutaneous fat layer thins, so it has less insulation and padding and reduced ability to maintain body temperature. Growths such as skin tags, rough patches (keratoses), skin cancers, and other lesions are more common. Older adults may also be less able to sense touch, pressure, vibration, heat, and cold.[12]

When completing an integumentary assessment, it is important to distinguish between expected and unexpected assessment findings. Please review Table 14.4b to review common expected and unexpected integumentary findings.

Table 14.4b Expected Versus Unexpected Findings on Integumentary Assessment

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify provider if it is a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Skin is expected color for ethnicity without lesions or rashes. | Jaundice

Erythema Cyanosis Irregular-looking mole Bruising (ecchymosis) Rashes Petechiae Skin breakdown Burns |

| Auscultation | Not applicable | |

| Palpation | Skin is warm and dry with no edema. Capillary refill is less than 3 seconds. Skin has normal turgor with no tenting. | Diaphoretic or clammy

Cool extremity Edema Lymphedema Capillary refill greater than 3 seconds Tenting |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Cool and clammy

Diaphoretic Petechiae Jaundice Cyanosis Redness, warmth, and tenderness indicating a possible infection |

- Medline Industries, Inc. (n.d.). Are you doing comprehensive skin assessments correctly? Get the whole picture. https://www.medline.com/skin-health/comprehensive-skin-assessments-correctly-get-whole-picture/#:~:text=A%20comprehensive%20skin%20assessment%20entails,actually%20more%20than%20skin%20deep ↵

- Giddens, J. F. (2007). A survey of physical examination techniques performed by RNs: Lessons for nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(2), 83-87. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20070201-09 ↵

- McKay, M. (1990). The dermatologic history. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207/ ↵

- Medline Industries, Inc. (n.d.). Are you doing comprehensive skin assessments correctly? Get the whole picture. https://www.medline.com/skin-health/comprehensive-skin-assessments-correctly-get-whole-picture/#:~:text=A%20comprehensive%20skin%20assessment%20entails,actually%20more%20than%20skin%20deep ↵

- Levine, D., Walker, J. R., Marcellin-Little, D. J., Goulet, R., & Ru, H. (2018). Detection of skin temperature differences using palpation by manual physical therapists and lay individuals. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 26(2), 97-101. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F10669817.2018.1427908 ↵

- Johannsen, L.L. (2005). Skin assessment. Dermatology Nursing, 17(2), 165-66. ↵

- Nurse Saria. (2018, September 18). Cardiovascular assessment part two | Capillary refill test [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/A6htMxo4Cks ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Skin turgor; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003281.htm#:~:text=To%20check%20for%20skin%20turgor,back%20to%20its%20normal%20position ↵

- Nursing Times. (2015, August 3). Detecting dehydration in older people. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/older-people-nurses-roles/detecting-dehydration-in-older-people-useful-tests-03-08-2015/ ↵

- “Combinpedal.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Grading of Edema” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Aging changes in skin; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004014.htm#:~:text=The%20remaining%20melanocytes%20increase%20in,the%20skin's%20strength%20and%20elasticity ↵

A process where the patient and nurse seek a mutually acceptable way to deal with competing interests of nursing care, prescribed medical care, and the patient’s cultural needs.

A safe space for patients to interact with health professionals, without judgment or discrimination, where the patient is free to express their cultural beliefs, values, and identity.

In addition to using established frameworks to resolve ethical dilemmas, nurses can also consult their organization’s ethics committee for ethical guidance in the workplace. Ethics committees are typically composed of interdisciplinary team members such as physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, administrators, social workers, and clergy to problem-solve ethical dilemmas. See Figure 6.8[1] for an illustration of an ethics committee. Hospital ethics committees were created in response to legal controversies regarding the refusal of life-sustaining treatment, such as the Karen Quinlan case.[2] Read more about the Karen Quinlan case and controversies surrounding life-sustaining treatment in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

After the passage of the Patient Self-Determination Act in 1991, all health care institutions receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding are required to form ethics committees. The Joint Commission (TJC) also requires organizations to have a formalized mechanism of dealing with ethical issues. Nurses should be aware of the process for requesting guidance and support from ethics committees at their workplace for ethical issues affecting patients or staff.[3]

Institutional Review Boards and Ethical Research

Other types of ethics committees have been formed to address the ethics of medical research on patients. Historically, there are examples of medical research causing harm to patients. For example, an infamous research study called the “Tuskegee Study” raised concern regarding ethical issues in research such as informed consent, paternalism, maleficence, truth-telling, and justice.

In 1932 the Tuskegee Study began a 40-year study looking at the long-term progression of syphilis. Over 600 Black men were told they were receiving free medical care, but researchers only treated men diagnosed with syphilis with aspirin, even after it was discovered that penicillin was a highly effective treatment for the disease. The institute allowed the study to go on, even when men developed long-stage neurological symptoms of the disease and some wives and children became infected with syphilis. In 1972 these consequences of the Tuskegee Study were leaked to the media and public outrage caused the study to shut down.[4]

Potential harm to patients participating in research studies like the Tuskegee Study was rationalized based on the utilitarian view that potential harm to individuals was outweighed by the benefit of new scientific knowledge resulting in greater good for society. As a result of public outrage over ethical concerns related to medical research, Congress recognized that an independent mechanism was needed to protect research subjects. In 1974 regulations were established requiring research with human subjects to undergo review by an institutional review board (IRB) to ensure it meets ethical criteria. An IRB is group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects.[5] The IRB review ensures the following criteria are met when research is performed:

- The benefits of the research study outweigh the potential risks.

- Individuals’ participation in the research is voluntary.

- Informed consent is obtained from research participants who have the ability to decline participation.

- Participants are aware of the potential risks of participating in the research.[6]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activities are provided as immediate feedback.)

Ethical Application & Reflection Activity

Case A

Filmmaker Lulu Wang first shared a story about her grandmother on This American Life podcast and later turned it into the 2019 movie The Farewell starring Awkwafina. Both share the challenges of a Chinese-born but U.S.-raised woman returning to China and a family who has chosen to not disclose that the grandmother has been given a Stage IV lung cancer diagnosis and three months to live. Listen to the podcast and then answer the following questions:

585: In Defense of Ignorance Act One: What You Don't Know

1. Reflect on the similarities and differences of your family culture with that of the Billi family. Consider things such as what family gatherings, formal and informal, look like and spoken and unspoken rules related to communication and behavior.

2. The idea of “good” lies and “bad” lies is introduced in the podcast. Nai Nai’s family supports the decision to not tell her about her Stage IV lung cancer, stage a wedding as the excuse to visit and say their goodbyes, and even alter a medical report as good lies necessary to support her mental health, well-being, and happiness. Is the family applying deontological or utilitarian ethics to the situation? Defend your response.

3. Define the following ethical principles and identify examples from this story:

- Autonomy

- Beneficence

- Nonmaleficence

- Paternalism

4. Imagine this story is happening in the United States rather than China and you are the nurse admitting Nai Nai to an inpatient oncology unit. Using the ethical problem-solving model of your choice, identify and support your solution to the ethical dilemma posed when her family requests that Nai Nai not be told that she has cancer.

Ethical Application & Reflection Activity

Case B

You are caring for a 32-year-old client who has been in a persistent vegetative state for many years. There is an outdated advanced directive that is confusing on the issue of food and fluids, though clear about not wanting to be on a ventilator if she were in a coma. Her husband wants the feeding tube removed but is unable to say that it would have been the client’s wish. He says that it is his decision for her. Her two adult siblings and parents reject this as a possibility because they say that “human life is sacred” and that the daughter believed this. They say their daughter is alive and should receive nursing care, including feeding. The health care team does not know what to do ethically and fear being sued by either the husband, siblings, or the parents. What do you need to know about this clinical situation? What are the values and obligations at stake in this case? What values or obligations should be affirmed and why? How might that be done?

1. Define the problem.

2. List what facts/information you have.

3. What are the stakeholders' positions?

- Patient:

- Spouse:

- Family:

- Health Care Team:

- Facility:

- Community:

4. How might the stakeholders' values differ?

5. What are your values in this situation?

6. Do your values conflict with those of the patient? Describe.

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[8]

Advocacy: The act or process of pleading for, supporting, or recommending a cause or course of action. Advocacy may be for persons (whether an individual, group, population, or society) or for an issue, such as potable water or global health.[9]

Autonomy: The capacity to determine one’s own actions through independent choice, including demonstration of competence.[10]

Beneficence: The bioethical principle of benefiting others by preventing harm, removing harmful conditions, or affirmatively acting to benefit another or others, often going beyond what is required by law.[11]

Code of ethics: A set of ethical principles established by a profession that is designed to govern decision-making and assist individuals to distinguish right from wrong.

Consequentialism: An ethical theory used to determine whether or not an action is right by the consequences of the action. For example, most people agree that lying is wrong, but if telling a lie would help save a person’s life, consequentialism says it’s the right thing to do.

Cultural humility: A humble and respectful attitude towards individuals of other cultures and an approach to learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.

Deontology: An ethical theory based on rules that distinguish right from wrong.

Ethical dilemma: Conflict resulting from competing values that requires a decision to be made from equally desirable or undesirable options.

Ethical principles: Principles used to define nurses’ moral duties and aid in ethical analysis and decision-making.[12] Foundational ethical principles include autonomy (self-determination), beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), justice (fairness), and veracity (tell the truth).

Ethics: The formal study of morality from a wide range of perspectives.[13]

Ethics committee: A formal committee established by a health care organization to problem-solve ethical dilemmas.

Fidelity: An ethical principle meaning keeping promises.

Institutional Review Board (IRB): A group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects.

Justice: A moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity and a standard linked to fairness for all in society.[14]

Moral conflict: Feelings occurring when an individual is uncertain about what values or principles should be applied to an ethical issue.[15]

Moral courage: The willingness of an individual to speak out and do what is right in the face of forces that would lead us to act in some other way.[16]

Moral distress: Feelings occurring when correct ethical action is identified but the individual feels constrained by competing values of an organization or other individuals.[17]

Moral injury: The distressing psychological, behavioral, social, and sometimes spiritual aftermath of exposure to events that contradict deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.

Morality: Personal values, character, or conduct of individuals or groups within communities and societies.[18]

Moral outrage: Feelings occurring when an individual witnesses immoral acts or practices they feel powerless to change.[19]

Morals: The prevailing standards of behavior of a society that enable people to live cooperatively in groups.[20]

Nonmaleficence: The bioethical principle that specifies a duty to do no harm and balances avoidable harm with benefits of good achieved.[21]

Paternalism: The interference by the state or an individual with another person, defended by the claim that the person interfered with will be better off or protected from harm.[22]

Utilitarianism: A type of consequentialism that determines whether or not actions are right based on their consequences, with the standard being achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Values: Individual beliefs that motivate people to act one way or another and serve as a guide for behavior.[23]

Veracity: An ethical principle meaning telling the truth.

Age-related hearing loss.

Advocacy: The act or process of pleading for, supporting, or recommending a cause or course of action. Advocacy may be for persons (whether an individual, group, population, or society) or for an issue, such as potable water or global health.[24]

Autonomy: The capacity to determine one’s own actions through independent choice, including demonstration of competence.[25]

Beneficence: The bioethical principle of benefiting others by preventing harm, removing harmful conditions, or affirmatively acting to benefit another or others, often going beyond what is required by law.[26]

Code of ethics: A set of ethical principles established by a profession that is designed to govern decision-making and assist individuals to distinguish right from wrong.

Consequentialism: An ethical theory used to determine whether or not an action is right by the consequences of the action. For example, most people agree that lying is wrong, but if telling a lie would help save a person’s life, consequentialism says it’s the right thing to do.

Cultural humility: A humble and respectful attitude towards individuals of other cultures and an approach to learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.

Deontology: An ethical theory based on rules that distinguish right from wrong.

Ethical dilemma: Conflict resulting from competing values that requires a decision to be made from equally desirable or undesirable options.

Ethical principles: Principles used to define nurses’ moral duties and aid in ethical analysis and decision-making.[27] Foundational ethical principles include autonomy (self-determination), beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), justice (fairness), and veracity (tell the truth).

Ethics: The formal study of morality from a wide range of perspectives.[28]

Ethics committee: A formal committee established by a health care organization to problem-solve ethical dilemmas.

Fidelity: An ethical principle meaning keeping promises.

Institutional Review Board (IRB): A group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects.

Justice: A moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity and a standard linked to fairness for all in society.[29]

Moral conflict: Feelings occurring when an individual is uncertain about what values or principles should be applied to an ethical issue.[30]

Moral courage: The willingness of an individual to speak out and do what is right in the face of forces that would lead us to act in some other way.[31]

Moral distress: Feelings occurring when correct ethical action is identified but the individual feels constrained by competing values of an organization or other individuals.[32]

Moral injury: The distressing psychological, behavioral, social, and sometimes spiritual aftermath of exposure to events that contradict deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.

Morality: Personal values, character, or conduct of individuals or groups within communities and societies.[33]

Moral outrage: Feelings occurring when an individual witnesses immoral acts or practices they feel powerless to change.[34]

Morals: The prevailing standards of behavior of a society that enable people to live cooperatively in groups.[35]

Nonmaleficence: The bioethical principle that specifies a duty to do no harm and balances avoidable harm with benefits of good achieved.[36]

Paternalism: The interference by the state or an individual with another person, defended by the claim that the person interfered with will be better off or protected from harm.[37]

Utilitarianism: A type of consequentialism that determines whether or not actions are right based on their consequences, with the standard being achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Values: Individual beliefs that motivate people to act one way or another and serve as a guide for behavior.[38]

Veracity: An ethical principle meaning telling the truth.