14.3 Common Integumentary Conditions

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Now that we have reviewed the anatomy of the integumentary system, let’s review common conditions that you may find during a routine integumentary assessment.

Acne

Acne is a skin disturbance that typically occurs on areas of the skin that are rich in sebaceous glands, such as the face and back. It is most common during puberty due to associated hormonal changes that stimulate the release of sebum. An overproduction and accumulation of sebum, along with keratin, can block hair follicles. Acne results from infection by acne-causing bacteria and can lead to potential scarring.[1] See Figure 14.8[2] for an image of acne.

Lice and Nits

Head lice are tiny insects that live on a person’s head. Adult lice are about the size of a sesame seed, but the eggs, called nits, are smaller and can appear like a dandruff flake. See Figure 14.9[3] for an image of very small white nits in a person’s hair. Children ages 3-11 often get head lice at school and day care because they have head-to-head contact while playing together. Lice move by crawling and spread by close person-to-person contact. Rarely, they can spread by sharing personal belongings such as hats or hair brushes. Contrary to popular belief, personal hygiene and cleanliness have nothing to do with getting head lice. Symptoms of head lice include the following:

- Tickling feeling in the hair

- Frequent itching, which is caused by an allergic reaction to the bites

- Sores from scratching, which can become infected with bacteria

- Trouble sleeping due to head lice being most active in the dark

A diagnosis of head lice usually comes from observing a louse or nit on a person’s head. Because they are very small and move quickly, a magnifying lens and a fine-toothed comb may be needed to find lice or nits. Treatments for head lice include over-the-counter and prescription shampoos, creams, and lotions such as permethrin lotion.[4]

Burns

A burn results when the skin is damaged by intense heat, radiation, electricity, or chemicals. The damage results in the death of skin cells, which can lead to a massive loss of fluid due to loss of the skin’s protection. Burned skin is also extremely susceptible to infection due to the loss of protection by intact layers of skin.

Burns are classified by the degree of their severity. A first-degree burn, also referred to as a superficial burn, only affects the epidermis. Although the skin may be painful and swollen, these burns typically heal on their own within a few days. Mild sunburn fits into the category of a first-degree burn. A second-degree burn, also referred to as a partial thickness burn, affects both the epidermis and a portion of the dermis. These burns result in swelling and a painful blistering of the skin. It is important to keep the burn site clean to prevent infection. With good care, a second-degree burn will heal within several weeks. A third-degree burn, also referred to as a full-thickness burn, extends fully into the epidermis and dermis, destroying the tissue and affecting the nerve endings and sensory function. These are serious burns that require immediate medical attention. A fourth-degree burn, also referred to as a deep full-thickness burn, is even more severe, affecting the underlying muscle and bone. Third- and fourth-degree burns are usually not as painful as second-degree burns because the nerve endings are damaged. Full-thickness burns require debridement (removal of dead skin) followed by grafting of the skin from an unaffected part of the body or from skin grown in tissue culture.[5] See Figure 14.10[6] for an image of a patient recovering from a second-degree burn on the hand.

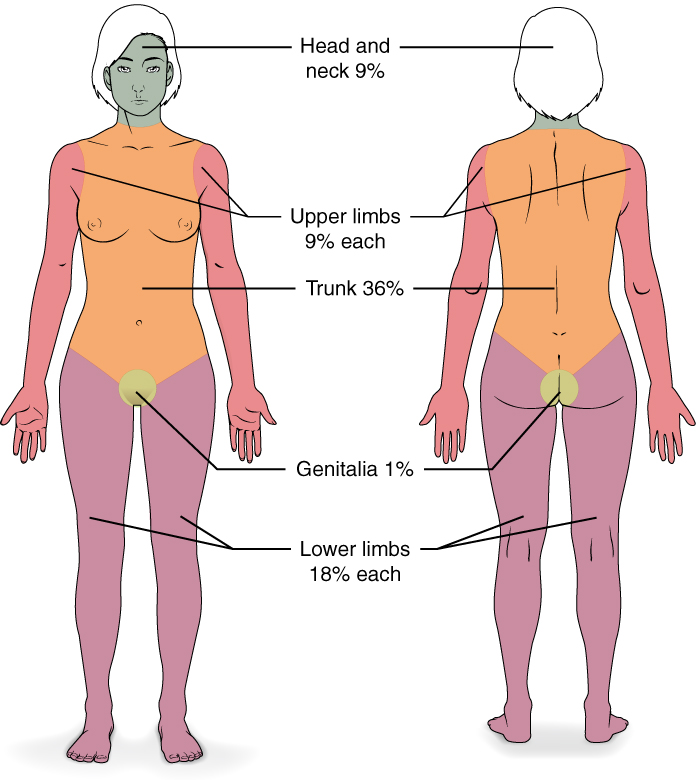

Severe burns are quickly measured in emergency departments using a tool called the “Rule of Nines,” which associates specific anatomical locations with a percentage that is a factor of nine. Rapid estimate of the burned surface area is used to estimate intravenous fluid replacement because patients will have massive fluid losses due to the removal of the skin barrier.[7] See Figure 14.11[8] for an illustration of the rule of nines. The head is 9% (4.5% on each side), the upper limbs are 9% each (4.5% on each side), the lower limbs are 18% each (9% on each side), and the trunk is 36% (18% on each side).

Scars

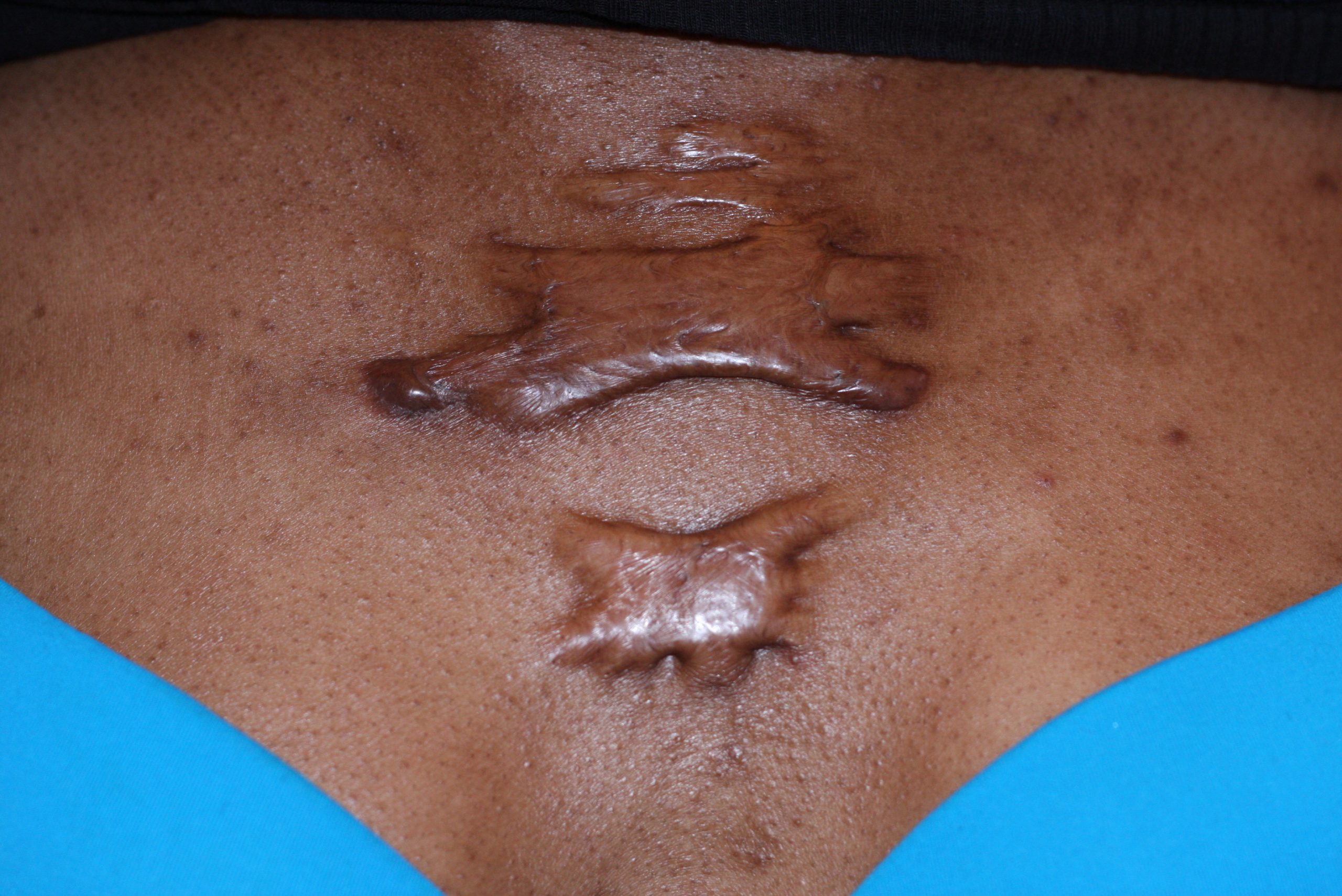

Most cuts and wounds cause scar formation. A scar is collagen-rich skin formed after the process of wound healing. Sometimes there is an overproduction of scar tissue because the process of collagen formation does not stop when the wound is healed, resulting in the formation of a raised scar called a keloid.[9] Keloids are more common in patients with darker skin color. See Figure 14.12[10] for an image of a keloid that has developed from a scar on a patient’s chest wall.

Skin Cancer

Skin cancer is common, with one in five Americans experiencing some type of skin cancer in their lifetime. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common of all cancers that occur in the United States and is frequently found on areas most susceptible to long-term sun exposure such as the head, neck, arms, and back. Basal cell carcinomas start in the epidermis and become an uneven patch, bump, growth, or scar on the skin surface. Treatment options include surgery, freezing (cryosurgery), and topical ointments.[11]

Squamous cell carcinoma presents as lesions commonly found on the scalp, ears, and hands. If not removed, squamous cell carcinomas can metastasize to other parts of the body. Surgery and radiation are used to cure squamous cell carcinoma. See Figure 14.13[12] for an image of squamous cell carcinoma.[13]

Melanoma is a cancer characterized by the uncontrolled growth of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the epidermis. A melanoma commonly develops from an existing mole. See Figure 14.14[14] for an image of a melanoma. Melanoma is the most fatal of all skin cancers because it is highly metastatic and can be difficult to detect before it has spread to other organs. Melanomas usually appear as asymmetrical brown and black patches with uneven borders and a raised surface. Treatment includes surgical excision and immunotherapy.[15]

Fungal (Tinea) Infections

Tinea is the name of a group of skin diseases caused by a fungus. Types of tinea include ringworm, athlete’s foot, and jock itch. These infections are usually not serious, but they can be uncomfortable because of the symptoms of itching and burning. They can be transmitted by touching infected people, damp surfaces such as shower floors, or even from pets.[16] Ringworm (tinea corporis) is a type of rash that forms on the body that typically looks like a red ring with a clear center, although a worm doesn’t cause it. Scalp ringworm (tinea capitals) causes itchy, red patches on the head that can leave bald spots. Athlete’s foot (tinea pedis) causes itching, burning, and cracked skin between the toes. Jock itch (tinea cruris) causes an itchy, burning rash in the groin area. Fungal infections are often treated successfully with over-the-counter creams and powders, but some require prescription medicine such as nystatin. See Figure 14.15[17] for an image of a tinea in a patient’s groin.[18]

Impetigo

Impetigo is a common skin infection caused by bacteria in children between the ages two and six. It is commonly caused by Staphylococcus (staph) or Streptococcus (strep) bacteria. See Figure 14.16[19] for an image of impetigo. Impetigo often starts when bacteria enter a break in the skin, such as a cut, scratch, or insect bite. Symptoms start with red or pimple-like sores surrounded by red skin. The sores fill with pus and then break open after a few days and form a thick crust. They are often itchy but scratching them can spread the sores. Impetigo can spread by contact with sores or nasal discharge from an infected person and is treated with antibiotics.

Edema

Edema is caused by fluid accumulation within the tissues often caused by underlying cardiovascular or renal disease. Read more about edema in the “Cardiovascular Basic Concepts” section of the “Cardiovascular Assessment” chapter.

Lymphedema

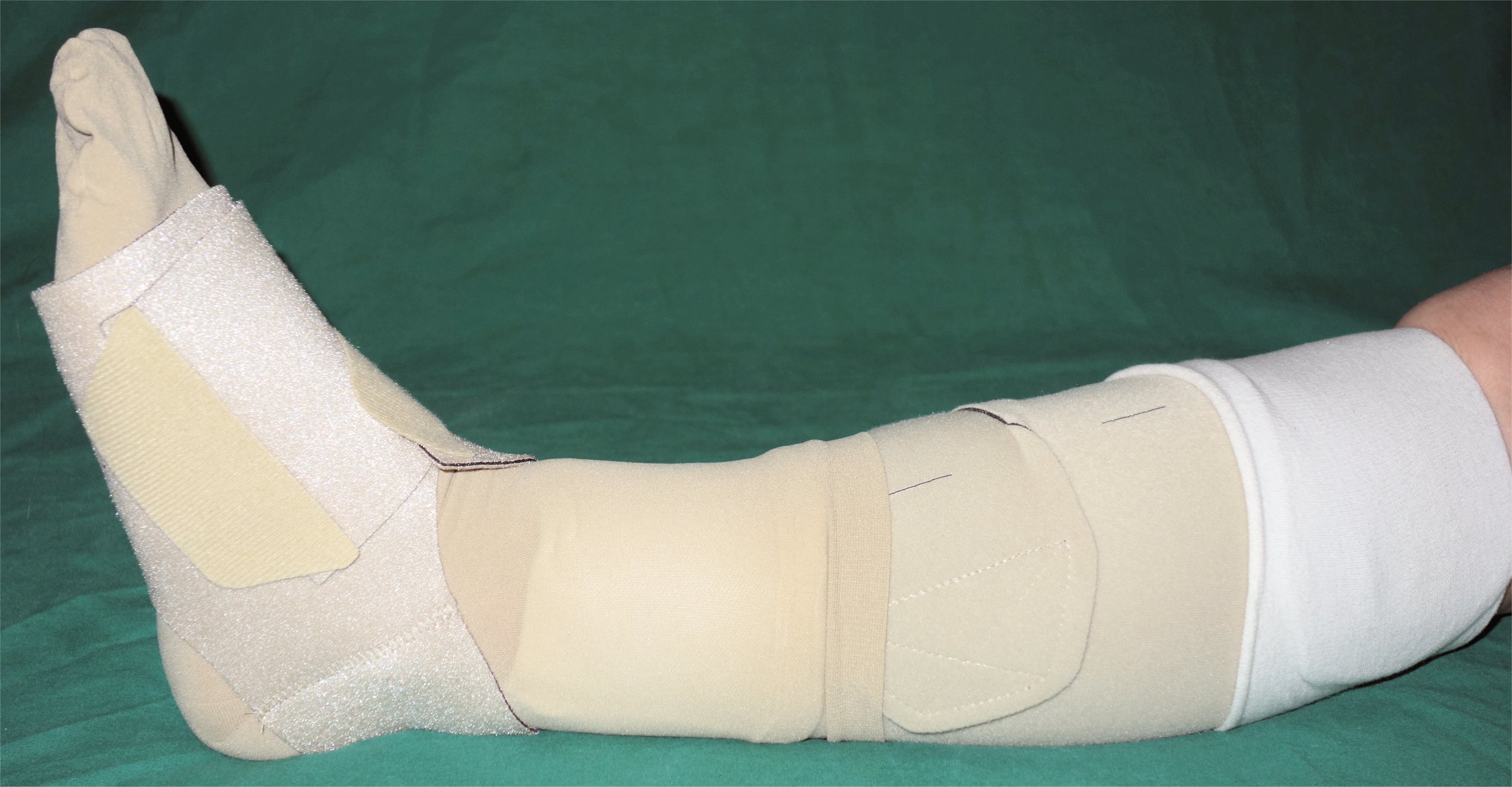

Lymphedema is the medical term for a type of swelling that occurs when lymph fluid builds up in the body’s soft tissues due to damage to the lymph system. It often occurs unilaterally in the arms or legs after surgery has been performed that injured the regional lymph nodes. See Figure 14.17[20] for an image of lower extremity edema. Causes of lymphedema include infection, cancer, scar tissue from radiation therapy, surgical removal of lymph nodes, or inherited conditions. There is no cure for lymphedema, but elevation of the affected extremity is vital. Compression devices and massage can help to manage the symptoms. See Figure 14.18[21] for an image of a specialized compression dressing used for lymphedema. It is also important to remember to avoid taking blood pressure on a patient’s extremity with lymphedema.[22]

Jaundice

Jaundice causes skin and sclera (whites of the eyes) to turn yellow. Due to variation in skin color, assessing for the presence jaundice is most accurately noted in the sclera of the eyes and/or the roof of mouth (hard palate). See Figure 14.19[23] for an image of a patient with jaundice visible in the sclera and the skin. Jaundice is caused by too much bilirubin in the body. Bilirubin is a yellow chemical in hemoglobin, the substance that carries oxygen in red blood cells. As red blood cells break down, the old ones are processed by the liver. If the liver can’t keep up due to large amounts of red blood cell breakdown or liver damage, bilirubin builds up and causes the skin and sclera to appear yellow. New onset of jaundice should always be reported to the health care provider.

Many healthy babies experience mild jaundice during the first week of life that usually resolves on its own, but some babies require additional treatment such as light therapy. Jaundice can happen at any age for many reasons, such as liver disease, blood disease, infections, or side effects of some medications.[24]

Pressure Injuries

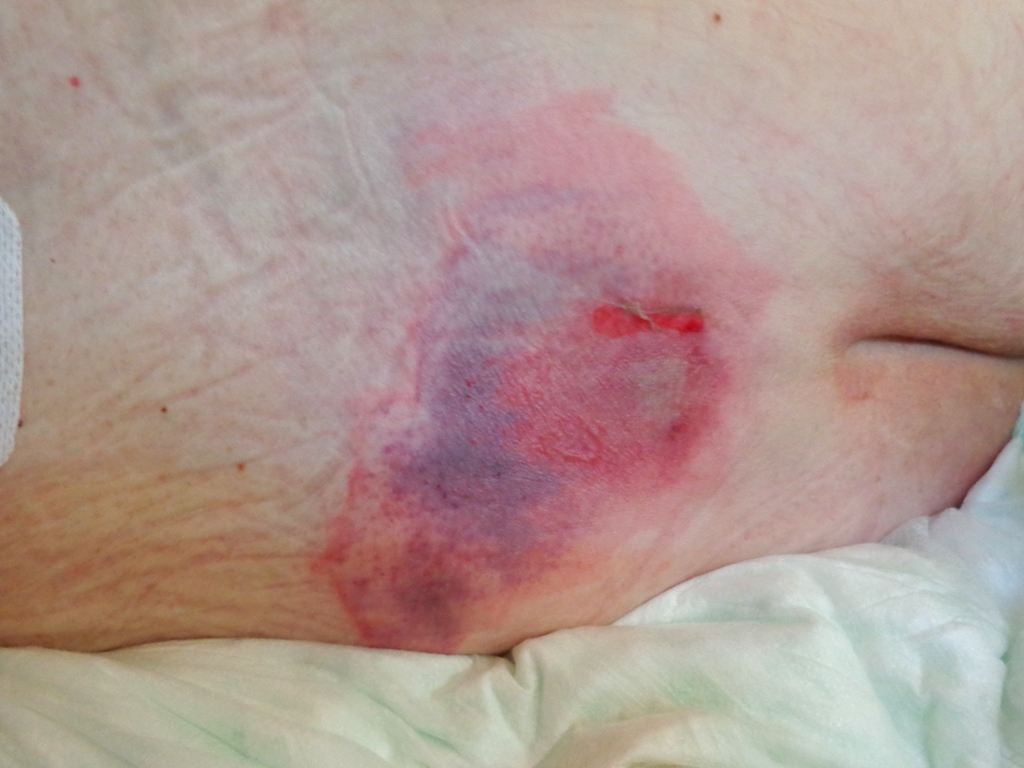

Pressure injuries , also called bedsores, form when a patient’s skin and soft tissue press against a hard surface, such as a chair or bed, for a prolonged period of time. The pressure against a hard surface reduces blood supply to that area, causing the skin tissue to become damaged and become an ulcer. Patients are at high risk of developing a pressure injury if they spend a lot of time in one position, have decreased sensation, or have bladder or bowel leakage.[25] See Figure 14.20[26] for an image of a pressure ulcer injury on a bed-bound patient’s back. Read more information about assessing and caring for a pressure injury in the “Wound Care” chapter.

Petechiae

Petechiae are tiny red dots caused by bleeding under the skin that may appear like a rash. Large petechiae are called purpura. An easy method used to assess for petechiae is to apply pressure to the rash with a gloved finger. A rash will blanch (i.e., whiten with pressure) but petechiae and purpura do not blanch. See Figure 14.21[27] for an image of petechiae and purpura. New onset of petechiae should be immediately reported to the health care provider because it can indicate a serious underlying medical condition.[28]

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Acne vulgaris on a very oily skin.jpg” by Roshu Bangal is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Fig.5. Louse nites.jpg” by KostaMumcuoglu at English Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Head lice; [reviewed 2016, Sep 9; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/headlice.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1Veertje hand-burn-do8.jpg” by 1Veertje is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Moore, Waheed, and Burns and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “513 Degree of burns.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Keloid-Butterfly, Chest Wall.JPG” by Htirgan is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Squamous cell carcinoma (3).jpg” by unknown photographer, provided by National Cancer Institute is licensed under CC0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-4-diseases-disorders-and-injuries-of-the-integumentary-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Melanoma (2).jpg” by unknown photographer, provided by National Cancer Institute is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-4-diseases-disorders-and-injuries-of-the-integumentary-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Tinea infections; [reviewed 2016, Apr 4; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/tineainfections.html#:~:text=Tinea%20is%20the%20name%20of,or%20even%20from%20a%20pet ↵

- “Tinea cruris.jpg” by Robertgascoin is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Tinea infections; [reviewed 2016, Apr 4; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/tineainfections.html#:~:text=Tinea%20is%20the%20name%20of,or%20even%20from%20a%20pet ↵

- “Impetigo2020.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- "Lymphedema_limbs.JPG" by medical doctors is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- "Adaptive_Kompressionsbandage_mit_Fußteil.jpg" by Enter is in the Public Domain. ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 27]. Lymphedema; [reviewed 2019, Jan 22; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/lymphedema.html ↵

- “Cholangitis Jaundice.jpg” by Bobjgalindo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2019, Oct 22]. Jaundice; [reviewed 2016, Aug 31; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/jaundice.html ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Preventing pressure ulcers; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000147.htm ↵

- “Decubitus 01.jpg” by AfroBrazilian is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Purpura.jpg” by User:Hektor is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Bleeding into the skin; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003235.htm ↵

Learning Objectives

- Compare theories of ethical decision making

- Examine resources to resolve ethical dilemmas

- Examine competent practice within the ethical framework of health care

- Apply the ANA Code of Ethics to diverse situations in health care

- Analyze the impact of cultural diversity in ethical decision making

- Explain advocacy as part of the nursing role when responding to ethical dilemmas

The nursing profession is guided by a code of ethics. As you practice nursing, how will you determine “right” from “wrong” actions? What is the difference between morality, values, and ethical principles? What additional considerations impact your ethical decision-making? What are ethical dilemmas and how should nurses participate in resolving them? This chapter answers these questions by reviewing concepts related to ethical nursing practice and describing how nurses can resolve ethical dilemmas. By the end of this chapter, you will be able to describe how to make ethical decisions using the Code of Ethics established by the American Nurses Association.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines morality as “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals or groups within communities and societies,” whereas ethics is the formal study of morality from a wide range of perspectives.[1] Ethical behavior is considered to be such an important aspect of nursing the ANA has designated Ethics as the first Standard of Professional Performance. The ANA Standards of Professional Performance are "authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently." See the following box for the competencies associated with the ANA Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[2]:

Competencies of ANA's Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[3]

- Uses the Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements as a moral foundation to guide nursing practice and decision-making.

- Demonstrates that every person is worthy of nursing care through the provision of respectful, person-centered, compassionate care, regardless of personal history or characteristics (Beneficence).

- Advocates for health care consumer perspectives, preferences, and rights to informed decision-making and self-determination (Respect for autonomy).

- Demonstrates a primary commitment to the recipients of nursing and health care services in all settings and situations (Fidelity).

- Maintains therapeutic relationships and professional boundaries.

- Safeguards sensitive information within ethical, legal, and regulatory parameters (Nonmaleficence).

- Identifies ethics resources within the practice setting to assist and collaborate in addressing ethical issues.

- Integrates principles of social justice in all aspects of nursing practice (Justice).

- Refines ethical competence through continued professional education and personal self-development activities.

- Depicts one's professional nursing identity through demonstrated values and ethics, knowledge, leadership, and professional comportment.

- Engages in self-care and self-reflection practices to support and preserve personal health, well-being, and integrity.

- Contributes to the establishment and maintenance of an ethical environment that is conducive to safe, quality health care.

- Collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, enhance cultural sensitivity and congruence, and reduce health disparities.

- Represents the nursing perspective in clinic, institutional, community, or professional association ethics discussions.

Reflective Questions

- What Ethics competencies have you already demonstrated during your nursing education?

- What Ethics competencies are you most interested in mastering?

- What questions do you have about the ANA’s Ethics competencies?

The ANA's Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements is an ethical standard that guides nursing practice and ethical decision-making.[4] This section will review several basic ethical concepts related to the ANA's Ethics Standard of Professional Performance, such as values, morals, ethical theories, ethical principles, and the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses.

Values

Values are individual beliefs that motivate people to act one way or another and serve as guides for behavior considered “right” and “wrong.” People tend to adopt the values with which they were raised and believe those values are “right” because they are the values of their culture. Some personal values are considered sacred and moral imperatives based on an individual’s religious beliefs.[5] See Figure 6.1[6] for an image depicting choosing right from wrong actions.

In addition to personal values, organizations also establish values. The American Nurses Association (ANA) Professional Nursing Model states that nursing is based on values such as caring, compassion, presence, trustworthiness, diversity, acceptance, and accountability. These values emerge from nursing practice beliefs, such as the importance of relationships, service, respect, willingness to bear witness, self-determination, and the pursuit of health.[7] As a result of these traditional values and beliefs by nurses, Americans have ranked nursing as the most ethical and honest profession in Gallup polls since 1999, with the exception of 2001, when firefighters earned the honor after the attacks on September 11.[8]

The National League of Nursing (NLN) has also established four core values for nursing education: caring, integrity, diversity, and excellence[9]:

- Caring: Promoting health, healing, and hope in response to the human condition.

- Integrity: Respecting the dignity and moral wholeness of every person without conditions or limitations.

- Diversity: Affirming the uniqueness of and differences among persons, ideas, values, and ethnicities.

- Excellence: Cocreating and implementing transformative strategies with daring ingenuity.

Morals

Morals are the prevailing standards of behavior of a society that enable people to live cooperatively in groups. “Moral” refers to what societies sanction as right and acceptable. Most people tend to act morally and follow societal guidelines, and most laws are based on the morals of a society. Morality often requires that people sacrifice their own short-term interests for the benefit of society. People or entities that are indifferent to right and wrong are considered “amoral,” while those who do evil acts are considered “immoral.”[11]

Ethical Theories

There are two major types of ethical theories that guide values and moral behavior referred to as deontology and consequentialism.

Deontology is an ethical theory based on rules that distinguish right from wrong. See Figure 6.2[12] for a word cloud illustration of deontology. Deontology is based on the word deon that refers to “duty.” It is associated with philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant believed that ethical actions follow universal moral laws, such as, “Don’t lie. Don’t steal. Don’t cheat.”[13] Deontology is simple to apply because it just requires people to follow the rules and do their duty. It doesn’t require weighing the costs and benefits of a situation, thus avoiding subjectivity and uncertainty.[14],[15],[16]

The nurse-patient relationship is deontological in nature because it is based on the ethical principles of beneficence and maleficence that drive clinicians to “do good” and “avoid harm.”[17] Ethical principles will be discussed further in this chapter.

Consequentialism is an ethical theory used to determine whether or not an action is right by the consequences of the action. See Figure 6.3[19] for an illustration of weighing the consequences of an action in consequentialism. For example, most people agree that lying is wrong, but if telling a lie would help save a person’s life, consequentialism says it’s the right thing to do. One type of consequentialism is utilitarianism. Utilitarianism determines whether or not actions are right based on their consequences with the standard being achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people.[20],[21],[22] For this reason, utilitarianism tends to be society-centered. When applying utilitarian ethics to health care resources, money, time, and clinician energy are considered finite resources that should be appropriately allocated to achieve the best health care for society.[23]

Utilitarianism can be complicated when accounting for values such as justice and individual rights. For example, assume a hospital has four patients whose lives depend upon receiving four organ transplant surgeries for a heart, lung, kidney, and liver. If a healthy person without health insurance or family support experiences a life-threatening accident and is considered brain dead but is kept alive on life-sustaining equipment in the ICU, the utilitarian framework might suggest the organs be harvested to save four lives at the expense of one life.[24] This action could arguably produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people, but the deontological approach could argue this action would be unethical because it does not follow the rule of “do no harm.”

Read more about Decision making on organ donation: The dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors.

Interestingly, deontological and utilitarian approaches to ethical issues may result in the same outcome, but the rationale for the outcome or decision is different because it is focused on duty (deontologic) versus consequences (utilitarian).

Societies and cultures have unique ethical frameworks that may be based upon either deontological or consequentialist ethical theory. Culturally derived deontological rules may apply to ethical issues in health care. For example, a traditional Chinese philosophy based on Confucianism results in a culturally acceptable practice of family members (rather than the client) receiving information from health care providers about life-threatening medical conditions and making treatment decisions. As a result, cancer diagnoses and end-of-life treatment options may not be disclosed to the client in an effort to alleviate the suffering that may arise from knowledge of their diagnosis. In this manner, a client’s family and the health care provider may ethically prioritize a client’s psychological well-being over their autonomy and self-determination.[26] However, in the United States, this ethical decision may conflict with HIPAA Privacy Rules and the ethical principle of patient autonomy. As a result, a nurse providing patient care in this type of situation may experience an ethical dilemma. Ethical dilemmas are further discussed in the "Ethical Dilemmas" section of this chapter.

See Table 6.2 comparing common ethical issues in health care viewed through the lens of deontological and consequential ethical frameworks.

Table 6.2. Ethical Issues Through the Lens of Deontological or Consequential Ethical Frameworks

| Ethical Issue | Deontological View | Consequential View |

|---|---|---|

| Abortion | Abortion is unacceptable based on the rule of preserving life. | Abortion may be acceptable in cases of an unwanted pregnancy, rape, incest, or risk to the mother. |

| Bombing an area with known civilians | Killing civilians is not acceptable due to the loss of innocent lives. | The loss of innocent lives may be acceptable if the bombing stops a war that could result in significantly more deaths than the civilian casualties. |

| Stealing | Taking something that is not yours is wrong. | Taking something to redistribute resources to others in need may be acceptable. |

| Killing | It is never acceptable to take another human being’s life. | It may be acceptable to take another human life in self-defense or to prevent additional harm they could cause others. |

| Euthanasia/physician- assisted suicide | It is never acceptable to assist another human to end their life prematurely. | End-of-life care can be expensive and emotionally upsetting for family members. If a competent, capable adult wishes to end their life, medically supported options should be available. |

| Vaccines | Vaccination is a personal choice based on religious practices or other beliefs. | Recommended vaccines should be mandatory for everyone (without a medical contraindication) because of its greater good for all of society. |

Ethical Principles and Obligations

Ethical principles are used to define nurses’ moral duties and aid in ethical analysis and decision-making.[27] Although there are many ethical principles that guide nursing practice, foundational ethical principles include autonomy (self-determination), beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), justice (fairness), fidelity (keep promises), and veracity (tell the truth).

Autonomy

The ethical principle of autonomy recognizes each individual’s right to self-determination and decision-making based on their unique values, beliefs, and preferences. See Figure 6.4[28] for an illustration of autonomy. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines autonomy as the “capacity to determine one’s own actions through independent choice, including demonstration of competence.”[29] The nurse’s primary ethical obligation is client autonomy.[30] Based on autonomy, clients have the right to refuse nursing care and medical treatment. An example of autonomy in health care is advance directives. Advance directives allow clients to specify health care decisions if they become incapacitated and unable to do so.

Read more about advance directives and determining capacity and competency in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

Nurses as Advocates: Supporting Autonomy

Nurses have a responsibility to act in the interest of those under their care, referred to as advocacy. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines advocacy as “the act or process of pleading for, supporting, or recommending a cause or course of action. Advocacy may be for persons (whether an individual, group, population, or society) or for an issue, such as potable water or global health.”[31] See Figure 6.5[32] for an illustration of advocacy.

Advocacy includes providing education regarding client rights, supporting autonomy and self-determination, and advocating for client preferences to health care team members and family members. Nurses do not make decisions for clients, but instead support them in making their own informed choices. At the core of making informed decisions is knowledge. Nurses serve an integral role in patient education. Clarifying unclear information, translating medical terminology, and making referrals to other health care team members (within their scope of practice) ensures that clients have the information needed to make treatment decisions aligned with their personal values.

At times, nurses may find themselves in a position of supporting a client’s decision they do not agree with and would not make for themselves or for the people they love. However, self-determination is a human right that honors the dignity and well-being of individuals. The nursing profession, rooted in caring relationships, demands that nurses have nonjudgmental attitudes and reflect “unconditional positive regard” for every client. Nurses must suspend personal judgement and beliefs when advocating for their clients’ preferences and decision-making.[33]

Beneficence

Beneficence is defined by the ANA as “the bioethical principle of benefiting others by preventing harm, removing harmful conditions, or affirmatively acting to benefit another or others, often going beyond what is required by law.”[34] See Figure 6.6[35] for an illustration of beneficence. Put simply, beneficence is acting for the good and welfare of others, guided by compassion. An example of beneficence in daily nursing care is when a nurse sits with a dying patient and holds their hand to provide presence.

Nursing advocacy extends beyond direct patient care to advocating for beneficence in communities. Vulnerable populations such as children, older adults, cultural minorities, and the homeless often benefit from nurse advocacy in promoting health equity. Cultural humility is a humble and respectful attitude towards individuals of other cultures and an approach to learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.[36] Nurses, the largest segment of the health care community, have a powerful voice when addressing community beneficence issues, such as health disparities and social determinants of health, and can serve as the conduit for advocating for change.

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence is defined by the ANA as “the bioethical principle that specifies a duty to do no harm and balances avoidable harm with benefits of good achieved.”[37] An example of doing no harm in nursing practice is reflected by nurses checking medication rights three times before administering medications. In this manner, medication errors can be avoided, and the duty to do no harm is met. Another example of nonmaleficence is when a nurse assists a client with a serious, life-threatening condition to participate in decision-making regarding their treatment plan. By balancing the potential harm with potential benefits of various treatment options, while also considering quality of life and comfort, the client can effectively make decisions based on their values and preferences.

Justice

Justice is defined by the ANA as “a moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity and a standard linked to fairness for all in society.”[38] The principle of justice requires health care to be provided in a fair and equitable way. Nurses provide quality care for all individuals with the same level of fairness despite many characteristics, such as the individual's financial status, culture, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Nurses have a social contract to “provide compassionate care that addresses the individual’s needs for protection, advocacy, empowerment, optimization of health, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering, comfort, and well-being.”[39] An example of a nurse using the principle of justice in daily nursing practice is effective prioritization based on client needs.

Read more about prioritization models in the “Prioritization” chapter.

Other Ethical Principles

Additional ethical principles commonly applied to health care include fidelity (keeping promises) and veracity (telling the truth). An example of fidelity in daily nursing practice is when a nurse tells a client, “I will be back in an hour to check on your pain level.” This promise is kept. An example of veracity in nursing practice is when a nurse honestly explains potentially uncomfortable side effects of prescribed medications. Determining how truthfulness will benefit the client and support their autonomy is dependent on a nurse’s clinical judgment, self-reflection, knowledge of the patient and their cultural beliefs, and other factors.[40]

A principle historically associated with health care is paternalism. Paternalism is defined as the interference by the state or an individual with another person, defended by the claim that the person interfered with will be better off or protected from harm.[41] Paternalism is the basis for legislation related to drug enforcement and compulsory wearing of seatbelts.

In health care, paternalism has been used as rationale for performing treatment based on what the provider believes is in the client’s best interest. In some situations, paternalism may be appropriate for individuals who are unable to comprehend information in a way that supports their informed decision-making, but it must be used cautiously to ensure vulnerable individuals are not misused and their autonomy is not violated.

Nurses may find themselves acting paternalistically when performing nursing care to ensure client health and safety. For example, repositioning clients to prevent skin breakdown is a preventative intervention commonly declined by clients when they prefer a specific position for comfort. In this situation, the nurse should explain the benefits of the preventative intervention and the risks if the intervention is not completed. If the client continues to decline the intervention despite receiving this information, the nurse should document the education provided and the client’s decision to decline the intervention. The process of reeducating the client and reminding them of the importance of the preventative intervention should be continued at regular intervals and documented.

Care-Based Ethics

Nurses use a client-centered, care-based ethical approach to patient care that focuses on the specific circumstances of each situation. This approach aligns with nursing concepts such as caring, holism, and a nurse-client relationship rooted in dignity and respect through virtues such as kindness and compassion.[42],[43] This care-based approach to ethics uses a holistic, individualized analysis of situations rather than the prescriptive application of ethical principles to define ethical nursing practice. This care-based approach asserts that ethical issues cannot be handled deductively by applying concrete and prefabricated rules, but instead require social processes that respect the multidimensionality of problems.[44] Frameworks for resolving ethical situations are discussed in the “Ethical Dilemmas” section of this chapter.

Nursing Code of Ethics

Many professions and institutions have their own set of ethical principles, referred to as a code of ethics, designed to govern decision-making and assist individuals to distinguish right from wrong. The American Nurses Association (ANA) provides a framework for ethical nursing care and guides nurses during decision-making in its formal document titled Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements (Nursing Code of Ethics). The Nursing Code of Ethics serves the following purposes[45]:

- It is a succinct statement of the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively.

- It is the profession’s nonnegotiable ethical standard.

- It is an expression of nursing’s own understanding of its commitment to society.

The preface of the ANA’s Nursing Code of Ethics states, “Individuals who become nurses are expected to adhere to the ideals and moral norms of the profession and also to embrace them as a part of what it means to be a nurse. The ethical tradition of nursing is self-reflective, enduring, and distinctive. A code of ethics makes explicit the primary goals, values, and obligations of the profession.”[46]

The Nursing Code of Ethics contains nine provisions. Each provision contains several clarifying or “interpretive” statements. Read a summary of the nine provisions in the following box.

Nine Provisions of the ANA Nursing Code of Ethics

- Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

- Provision 2: The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

- Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

- Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.

- Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

- Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

- Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

- Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

- Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

Read the free, online full version of the ANA's Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements.

In addition to the Nursing Code of Ethics, the ANA established the Center for Ethics and Human Rights to help nurses navigate ethical conflicts and life-and-death decisions common to everyday nursing practice.

Read more about the ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights.

Specialty Organization Code of Ethics

Many specialty nursing organizations have additional codes of ethics to guide nurses practicing in settings such as the emergency department, home care, or hospice care. These documents are unique to the specialty discipline but mirror the statements from the ANA’s Nursing Code of Ethics. View ethical statements of various specialty nursing organizations using the information in the following box.

Ethical Statements of Selected Specialty Nursing Organizations

Learning Objectives

- Collaborate with interprofessional team members when providing client care

- Manage conflict among clients and health care staff

- Perform procedures necessary to safely admit, transfer, and/or discharge a client

- Assess the need for referrals and obtain necessary orders

- Describe how the health care team meets the needs of diverse patients in a variety of settings

- Identify strategies to ensure productive, effective team functioning

All health care students must prepare to deliberately work together in clinical practice with a common goal of building a safer, more effective, patient-centered health care system. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines interprofessional collaborative practice as multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds working together with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care.[47]

Effective teamwork and communication have been proven to reduce medical errors, promote a safety culture, and improve patient outcomes.[48] The importance of effective interprofessional collaboration has become even more important as nurses advocate to reduce health disparities related to social determinants of health (SDOH). In these efforts, nurses work with people from a variety of professions, such as physicians, social workers, educators, policy makers, attorneys, faith leaders, government employees, community advocates, and community members. Nursing students must be prepared to effectively collaborate interprofessionally after graduation.[49]

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) has identified four core competencies for effective interprofessional collaborative practice. This chapter will review content related to these four core competencies and provide examples of how they relate to nursing.

In addition to using established frameworks to resolve ethical dilemmas, nurses can also consult their organization’s ethics committee for ethical guidance in the workplace. Ethics committees are typically composed of interdisciplinary team members such as physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, administrators, social workers, and clergy to problem-solve ethical dilemmas. See Figure 6.8[50] for an illustration of an ethics committee. Hospital ethics committees were created in response to legal controversies regarding the refusal of life-sustaining treatment, such as the Karen Quinlan case.[51] Read more about the Karen Quinlan case and controversies surrounding life-sustaining treatment in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

After the passage of the Patient Self-Determination Act in 1991, all health care institutions receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding are required to form ethics committees. The Joint Commission (TJC) also requires organizations to have a formalized mechanism of dealing with ethical issues. Nurses should be aware of the process for requesting guidance and support from ethics committees at their workplace for ethical issues affecting patients or staff.[52]

Institutional Review Boards and Ethical Research

Other types of ethics committees have been formed to address the ethics of medical research on patients. Historically, there are examples of medical research causing harm to patients. For example, an infamous research study called the “Tuskegee Study” raised concern regarding ethical issues in research such as informed consent, paternalism, maleficence, truth-telling, and justice.

In 1932 the Tuskegee Study began a 40-year study looking at the long-term progression of syphilis. Over 600 Black men were told they were receiving free medical care, but researchers only treated men diagnosed with syphilis with aspirin, even after it was discovered that penicillin was a highly effective treatment for the disease. The institute allowed the study to go on, even when men developed long-stage neurological symptoms of the disease and some wives and children became infected with syphilis. In 1972 these consequences of the Tuskegee Study were leaked to the media and public outrage caused the study to shut down.[53]

Potential harm to patients participating in research studies like the Tuskegee Study was rationalized based on the utilitarian view that potential harm to individuals was outweighed by the benefit of new scientific knowledge resulting in greater good for society. As a result of public outrage over ethical concerns related to medical research, Congress recognized that an independent mechanism was needed to protect research subjects. In 1974 regulations were established requiring research with human subjects to undergo review by an institutional review board (IRB) to ensure it meets ethical criteria. An IRB is group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects.[54] The IRB review ensures the following criteria are met when research is performed:

- The benefits of the research study outweigh the potential risks.

- Individuals’ participation in the research is voluntary.

- Informed consent is obtained from research participants who have the ability to decline participation.

- Participants are aware of the potential risks of participating in the research.[55]

Nursing students may encounter ethical dilemmas when in clinical practice settings. Read more about research regarding ethical dilemmas experienced by students as described in the box.

Nursing Students and Ethical Dilemmas[57]

An integrative literature review performed by Albert, Younas, and Sana in 2020 identified ethical dilemmas encountered by nursing students in clinical practice settings. Three themes were identified:

1. Applying learned ethical values vs. accepting unethical practice

Students observed unethical practices of nurses and physicians, such as breach of patient privacy, confidentiality, respect, rights, duty to provide information, and physical and psychological mistreatment, that opposed the ethical values learned in nursing school. Students experienced ethical conflict due to their sense of powerlessness, low status as students, dependence on staff nurses for learning experiences, and fear of offending health care providers.

2. Desiring to provide ethical care but lacking autonomous decision-making

Students reported a lack of moral courage in questioning unethical practices. The hierarchy of health care environments left students feeling disregarded, humiliated, and intimidated by professional nurses and managers. Students also reported a sense of loss of identity in feeling forced to conform their personal identity to that of the clinical environment.

3. Whistleblowing vs. silence regarding patient care and neglect

Students observed nurses performing unethical nursing practices, such as ignoring client needs, disregarding pain, being verbally abusive, talking inappropriately about clients, and not providing a safe or competent level of care. Most students reported remaining silent regarding these observations due to a lack of confidence, feeling it was not their place to report, or the fear of negative consequences. Organizational power dynamics influenced student confidence in reporting unethical practices to faculty or nurse managers.

The researchers concluded that nursing students feel moral distress when experiencing these kinds of conflicts:

- Providing ethical care as learned in their program of study or accepting unethical practices

- Staying silent about patient care neglect or confronting it and reporting it

- Providing quality, ethical care or adapting to organizational culture due to lack of autonomous decision-making

These ethical conflicts can be detrimental to students' professional learning and mental health. Researchers recommended that nurse educators should develop educational programs to support students as they develop ethical competence and moral courage to confront ethical dilemmas.[58]

Read more about ethics education in nursing in the ANA’s Online Journal of Issues in Nursing article.

COVID-19 and the Nursing Profession

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of nurses’ foundational knowledge of ethical principles and the Nursing Code of Ethics. Scarce resources in an overwhelmed health care system resulted in ethical dilemmas and moral injury for nurses involved in balancing conflicting values, rights, and ethical principles. Many nurses were forced to weigh their duty to patients and society against their duty to themselves and their families. Challenging ethical issues occurred related to the ethical principle of justice, such as fair distribution of limited ICU beds and ventilators, and ethical dilemmas related to end-of-life issues such as withdrawing or withholding life-prolonging treatment became common.[59]

Regardless of their practice setting or personal contact with clients affected by COVID-19, nurses have been forced to reflect on the essence of ethical professional nursing practice through the lens of personal values and morals. Nursing students must be knowledgeable about ethical theories, ethical principles, and strategies for resolving ethical dilemmas as they enter the nursing profession that will continue to experience long-term consequences as a result of COVID-19.[60]