14.2 Basic Integumentary Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

The integumentary system includes the skin, hair, and nails. The skin is an organ that performs a variety of essential functions, such as protecting the body from invasion by microorganisms, chemicals, and other environmental factors; preventing dehydration; acting as a sensory organ; modulating body temperature and electrolyte balance; and synthesizing vitamin D.[1]

Skin

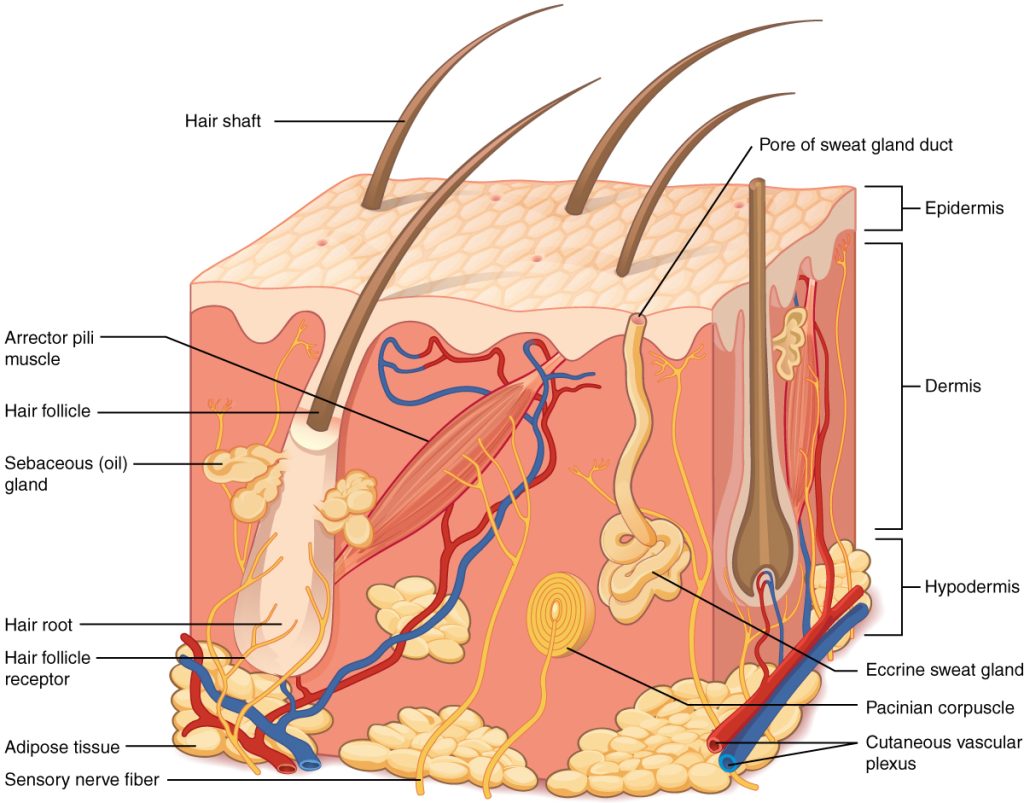

The skin is made of multiple layers of cells and tissues, which are held to underlying structures by connective tissue. See Figure 14.1[2] for an image of the layers of the skin. The skin is composed of two main layers: the uppermost thin layer called the epidermis made of closely packed epithelial cells, and the inner thick layer called the dermis that houses blood vessels, hair follicles, sweat glands, and nerve fibers. Beneath the dermis lies the hypodermis that contains connective tissue and adipose tissue (stored fat) to connect the skin to the underlying bones and muscles. The skin acts as a sense organ because the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis contain specialized sensory nerve structures that detect touch, surface temperature, and pain.[3]

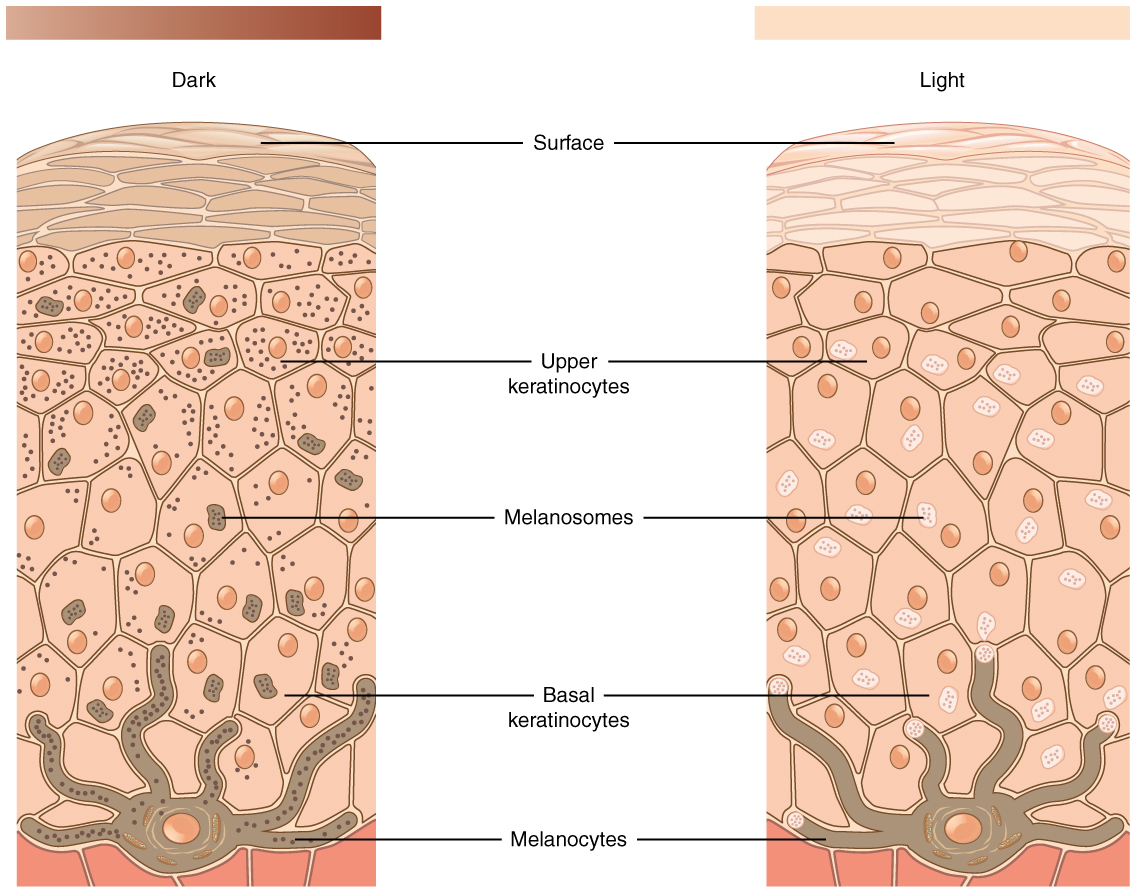

The color of skin is created by pigments, including melanin, carotene, and hemoglobin. Melanin is produced by cells called melanocytes that are scattered throughout the epidermis. See Figure 14.2[4] for an illustration of melanin and melanocytes. When there is an irregular accumulation of melanocytes in the skin, freckles appear. Dark-skinned individuals produce more melanin than those with pale skin. Exposure to the UV rays of the sun or a tanning bed causes additional melanin to be manufactured and built up, resulting in the darkening of the skin referred to as a tan. Increased melanin accumulation protects the DNA of epidermal cells from UV ray damage, but it requires about ten days after initial sun exposure for melanin synthesis to peak. This is why pale-skinned individuals often suffer sunburns during initial exposure to the sun. Darker-skinned individuals can also get sunburns, but they are more protected from their existing melanin than pale-skinned individuals.[5]

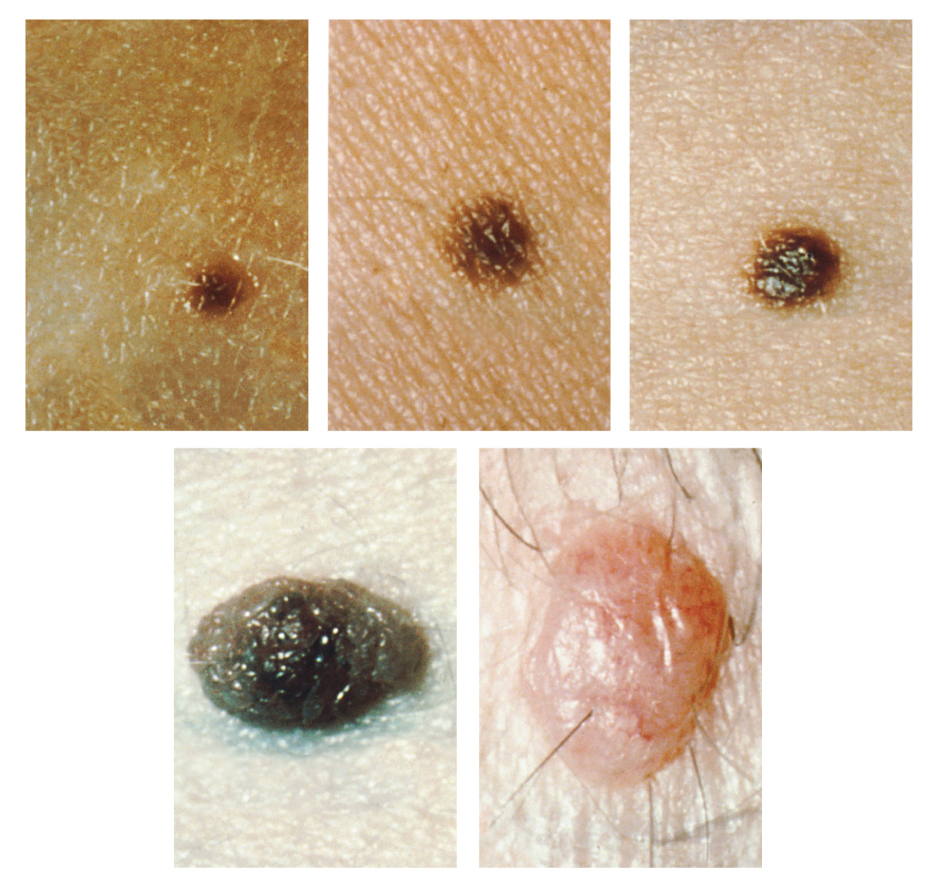

Too much sun exposure can eventually lead to wrinkling due to the destruction of the cellular structure of the skin, and in severe cases, can cause DNA damage resulting in skin cancer. Moles are larger masses of melanocytes, and although most are benign, they should be monitored for changes that indicate the presence of skin cancer. See Figure 14.3[6] for an image of moles.

Patients are encouraged to use the ABCDE mnemonic to watch for signs of early-stage melanoma developing in moles. Consult a health care provider if you find these signs of melanoma when assessing a patient’s skin:

- Asymmetrical: The sides of the moles are not symmetrical

- Borders: The edges of the mole are irregular in shape

- Color: The color of the mole has various shades of brown or black

- Diameter: The mole is larger than 6 mm (0.24 in)

- Evolving: The shape of the mole has changed

Hair

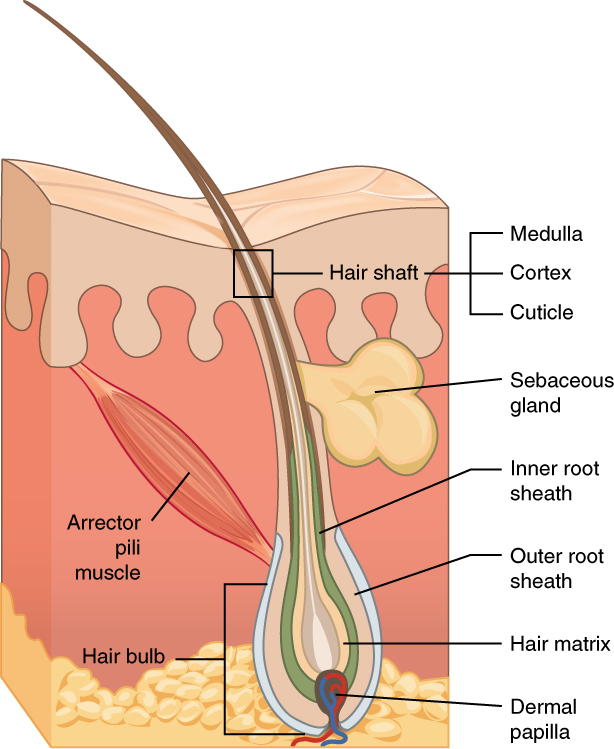

Hair is made of dead, keratinized cells that originate in the hair follicle in the dermis. For these reasons, there is no sensation in hair. See Figure 14.4[7] for an image of a hair follicle. Hair serves a variety of functions, including protection, sensory input, thermoregulation, and communication. For example, hair on the head protects the skull from the sun. Hair in the nose, ears, and around the eyes (eyelashes) defends the body by trapping any dust particles that may contain allergens and microbes. Hair of the eyebrows prevents sweat and other particles from dripping into the eyes.

Hair also has a sensory function due to sensory innervation by a hair root plexus surrounding the base of each hair follicle. Hair is extremely sensitive to air movement or other disturbances in the environment, even more so than the skin surface. This feature is also useful for the detection of the presence of insects or other potentially damaging substances on the skin surface. Each hair root is also connected to a smooth muscle called the arrector pili that contracts in response to nerve signals from the sympathetic nervous system, making the external hair shaft “stand up.” This movement is commonly referred to as goose bumps. The primary purpose for this movement is to trap a layer of air to add insulation.[8]

Nails

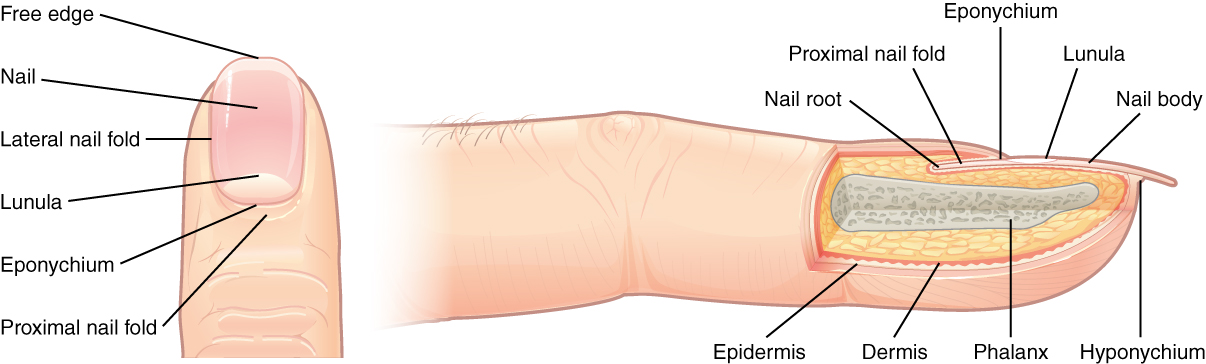

The nail bed is a specialized structure of the epidermis that is found at the tips of our fingers and toes. See Figure 14.5[9] for an illustration of a fingernail. The nail body is formed on the nail bed and protects the tips of our fingers and toes as they experience mechanical stress while being used. In addition, the nail body forms a back-support for picking up small objects with the fingers.[10]

Sweat Glands

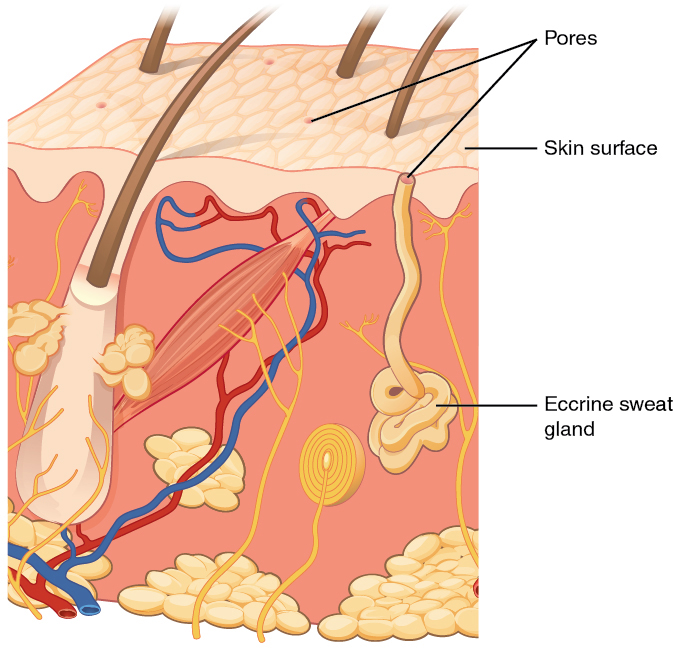

When the body becomes warm, sweat glands produce sweat to cool the body. There are two types of sweat glands that secrete slightly different products. An eccrine sweat gland produces hypotonic sweat for thermoregulation. See Figure 14.6[11] for an illustration of an eccrine sweat gland. These glands are found all over the skin’s surface but are especially abundant on the palms of the hand, the soles of the feet, and the forehead. They are coiled glands lying deep in the dermis, with the duct rising up to a pore on the skin surface where the sweat is released. This type of sweat is composed mostly of water and some salt, antibodies, traces of metabolic waste, and dermcidin, an antimicrobial peptide. Eccrine glands are a primary component of thermoregulation and help to maintain homeostasis.[12]

Apocrine sweat glands are mostly found in hair follicles in densely hairy areas, such as the armpits and genital regions. In addition to secreting water and salt, apocrine sweat includes organic compounds that make the sweat thicker and subject to bacterial decomposition and subsequent odor. The release of this sweat is controlled by the nervous system and hormones and plays a role in the human pheromone response. Most commercial antiperspirants use an aluminum-based compound as their primary active ingredient to stop sweat. When the antiperspirant enters the sweat gland duct, the aluminum-based compounds form a physical block in the duct, which prevents sweat from coming out of the pore.[13]

Skin Lesions

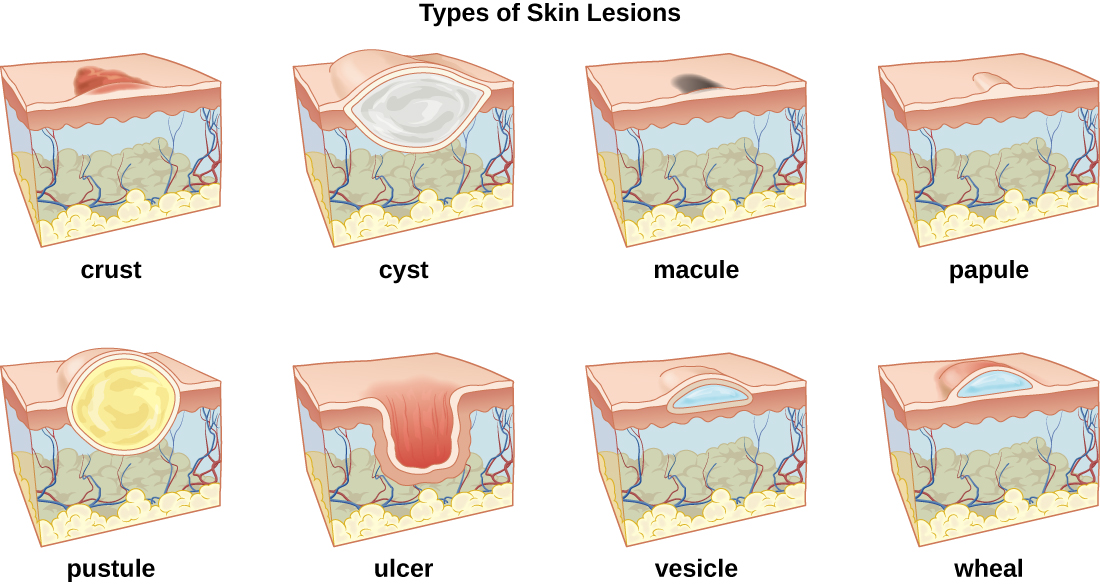

A lesion is an area of abnormal tissue. There are many terms for common skin lesions that may be described in a patient’s chart. These terms are defined in Table 14.2. See Figure 14.7[14] for illustrations of common skin lesions.

Table 14.2 Medical Terms Associated with Skin Lesions and Rashes[15]

| Medical Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| abscess | localized collection of pus |

| bulla (pl., bullae) | fluid-filled blister no more than 5 mm in diameter |

| carbuncle | deep, pus-filled abscess generally formed from multiple furuncles |

| crust | dried fluids from a lesion on the surface of the skin |

| cyst | encapsulated sac filled with fluid, semi-solid matter, or gas, typically located just below the upper layers of skin |

| folliculitis | a localized rash due to inflammation of hair follicles |

| furuncle (boil) | pus-filled abscess due to infection of a hair follicle |

| macules | smooth spots of discoloration on the skin |

| papules | small, raised bumps on the skin, such as a mosquito bite |

| pseudocyst | lesion that resembles a cyst but with a less-defined boundary |

| purulent | pus-producing; also called suppurative |

| pustules | fluid- or pus-filled bumps on the skin, such as acne |

| pyoderma | any suppurative (pus-producing) infection of the skin |

| suppurative | producing pus; purulent |

| ulcer | break in the skin or open sore such as a venous ulcer |

| vesicle | small, fluid-filled lesion, such as a herpes blister |

| wheal | swollen, inflamed skin that itches or burns, often from an allergic reaction |

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “501 Structure of the skin.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-1-layers-of-the-skin ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “504 Melanocytes.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-1-layers-of-the-skin ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Skin turgor; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003281.htm#:~:text=To%20check%20for%20skin%20turgor,back%20to%20its%20normal%20position ↵

- “508 Moles.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-1-layers-of-the-skin ↵

- “506 Hair.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-2-accessory-structures-of-the-skin ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “507 Nails.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-2-accessory-structures-of-the-skin ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “508 Eccrine gland.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-2-accessory-structures-of-the-skin ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “OSC Microbio 21 01 LesionLine.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:OSC_Microbio_21_01_LesionLine.jpg ↵

- This work is derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

You have worked hard to obtain a nursing license and it will be your livelihood. See Figure 5.7[1] for an illustration of a nursing license. Protecting your nursing license is vital.

Actions to Protect Your License

There are several actions that nurses can take to protect their nursing license, avoid liability, and promote patient safety. See Table 5.5 for a summary of recommendations.

Table 5.5 Risk Management Recommendations to Protect Your Nursing License

| Legal Issues | Recommendations to Protect Your License |

|---|---|

| Practicing outside one’s scope of practice |

|

| Failure to assess & monitor |

|

| Documentation |

|

| Medication errors |

|

| Substance abuse and drug diversion |

|

| Acts that may result in potential or actual client harm |

|

| Safe-guarding client possessions & valuables |

|

| Adherence to mandatory reporting responsibilities |

|

Culture of Safety

It can be frightening to think about entering the nursing profession after becoming aware of potential legal actions and risks to your nursing license, especially when realizing even an unintentional error could result in disciplinary or legal action. When seeking employment, it is helpful for nurses to ask questions during the interview process regarding organizational commitment to a culture of safety to reduce errors and enhance patient safety.

Many health care agencies have adopted a culture of safety that embraces error reporting by employees with the goal of identifying root causes of problems so they may be addressed to improve patient safety. One component of a culture of safety is "Just Culture." Just Culture is culture where people feel safe raising questions and concerns and report safety events in an environment that emphasizes a nonpunitive response to errors and near misses. Clear lines are drawn between human error, at-risk, and reckless behaviors. [8]

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture. They stated that while our traditional health care culture held individuals accountable for all errors and accidents that happened to patients under their care, the Just Culture model recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. The Just Culture model also recognizes that many errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, the Just Culture model does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to patients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).[9]

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three categories of errors: simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. Consequences of errors are based on these categories.[10] When seeking employment, it is helpful for nurses to determine how an agency implements a culture of safety because of its potential impact on one’s professional liability and licensure.

Read more about the Just Culture model in the "Basic Concepts" section of the "Leadership and Management" chapter.

You have worked hard to obtain a nursing license and it will be your livelihood. See Figure 5.7[11] for an illustration of a nursing license. Protecting your nursing license is vital.

Actions to Protect Your License

There are several actions that nurses can take to protect their nursing license, avoid liability, and promote patient safety. See Table 5.5 for a summary of recommendations.

Table 5.5 Risk Management Recommendations to Protect Your Nursing License

| Legal Issues | Recommendations to Protect Your License |

|---|---|

| Practicing outside one’s scope of practice |

|

| Failure to assess & monitor |

|

| Documentation |

|

| Medication errors |

|

| Substance abuse and drug diversion |

|

| Acts that may result in potential or actual client harm |

|

| Safe-guarding client possessions & valuables |

|

| Adherence to mandatory reporting responsibilities |

|

Culture of Safety

It can be frightening to think about entering the nursing profession after becoming aware of potential legal actions and risks to your nursing license, especially when realizing even an unintentional error could result in disciplinary or legal action. When seeking employment, it is helpful for nurses to ask questions during the interview process regarding organizational commitment to a culture of safety to reduce errors and enhance patient safety.

Many health care agencies have adopted a culture of safety that embraces error reporting by employees with the goal of identifying root causes of problems so they may be addressed to improve patient safety. One component of a culture of safety is "Just Culture." Just Culture is culture where people feel safe raising questions and concerns and report safety events in an environment that emphasizes a nonpunitive response to errors and near misses. Clear lines are drawn between human error, at-risk, and reckless behaviors. [18]

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture. They stated that while our traditional health care culture held individuals accountable for all errors and accidents that happened to patients under their care, the Just Culture model recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. The Just Culture model also recognizes that many errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, the Just Culture model does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to patients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).[19]

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three categories of errors: simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. Consequences of errors are based on these categories.[20] When seeking employment, it is helpful for nurses to determine how an agency implements a culture of safety because of its potential impact on one’s professional liability and licensure.

Read more about the Just Culture model in the "Basic Concepts" section of the "Leadership and Management" chapter.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activities are provided as immediate feedback.)

- In 2006 Nurse Julie Thao was charged with felony criminal negligence in the death of a 16-year-old laboring mother when she mistakenly hung a bag of epidural medication instead of intravenous penicillin. Although the baby was successfully delivered via cesarean section, the client died following aggressive resuscitation attempts as a result of circulatory collapse. Nurse Thao was fired from her job of 16 years. Her felony charge was amended to two misdemeanor counts, and her state’s Board of Nursing suspended her license, imposed practice limitations upon return, mandated completion of an education program, and imposed a $2,500 fine. Beyond these sanctions, she stated at her sentencing hearing, “The anguish and remorse are a life sentence that will serve for all time.”

View the Chasing Zero Documentary on YouTube[21]

Discuss factors that contributed to Nurse Julie Thao’s medication error. What reflections on your own nursing practice can be made after viewing this video clip? What actions might have been taken to avoid this error? Do you believe other members of the health care team were culpable in their actions?

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[22]

In addition to being aware of the legal and regulatory frameworks in which one practices nursing, it is also important for nurses to understand the legal concepts of informed consent and advance directives.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is the fundamental right of a client to accept or reject health care. Nurses have a legal responsibility to provide verbal and/or written information and obtain verbal or written consent for performing nursing care such as bathing, medication administration, and urinary or intravenous catheter insertion. While physicians have the responsibility to provide information and obtain informed consent related to medical procedures, nurses are typically required to verify the presence of a valid, signed informed consent before the procedure is performed. Additionally, if nurses do not believe the patient has adequate understanding of a procedure, its risks, benefits, or alternatives to treatment, they should request the provider return to clarify unclear information with the client. Nurses must remain within their scope of practice related to informed consent beyond nursing acts.

Two legal concepts related to informed consent are competence and capacity. Competence is a legal term defined as the ability of an individual to participate in legal proceedings. A judge decides if an individual is “competent” or “incompetent.” In contrast, capacity is “a functional determination that an individual is or is not capable of making a medical decision within a given situation.”[23] It is outside the scope of practice for nurses to formally assess capacity, but nurses may initiate the evaluation of client capacity and contribute assessment information. States typically require two health care providers to identify an individual as “incapacitated” and unable to make their own health care decisions. Capacity may be a temporary or permanent state.

The following box outlines situations where the nurse may question a client's decision-making capacity.

| Triggers for Questioning Capacity and Decision-Making[24] |

|---|

|

If an individual has an advance directive in place, their designated power of attorney for health care may step in and make medical decisions when the client is deemed incapacitated. In the absence of advance directives, the legal system may take over and appoint a guardian to make medical decisions for an individual. The guardian is often a family member or friend but may be completely unrelated to the incapacitated individual. Nurses are instrumental in encouraging a client to complete an advance directive while they have capacity to do so.

Advance Directives

The Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) is a federal law passed by Congress in 1990 following highly publicized cases involving the withdrawal of life-supporting care for incompetent individuals. (Read more about the Karen Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terri Shaivo cases in the boxes at the end of this section.) The PSDA requires health care institutions, such as hospitals and long-term care facilities, to offer adults written information that advises them "to make decisions concerning their medical care, including the right to accept or refuse medical or surgical treatment and the right to formulate, at the individual's option, advance directives.”[25] Advanced directives are defined as written instructions, such as a living will or durable power of attorney for health care, recognized under state law, relating to the provision of health care when the individual is incapacitated. The PSDA allows clients to record their preferences about do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment. In the absence of a client’s advance directives, the court may assert an “unqualified interest in the preservation of human life to be weighed against the constitutionally protected interests of the individual.”[26] For this reason, nurses must educate and support the communities they serve regarding the creation of advanced directives.

Advanced directives vary by state. For example, some states allow lay witness signatures whereas some require a notary signature. Some states place restrictions on family members, doctors, or nurses serving as witnesses. It is important for individuals creating advance directives to follow instructions for state-specific documents to ensure they are legally binding and honored.

Advance directives do not require an attorney to complete. In many organizations, social workers or chaplains assist individuals to complete advance directives following referral from physicians or nurses. Clients should review and update their documents every 10-15 years, as well as with changes in relationship status or if new medical conditions are diagnosed.

Although advanced directive documents vary by state, they generally fall into two categories, referred to as a living will or durable power of attorney for healthcare.

Living Will

A living will is a type of advance directive in which an individual identifies what treatments they would like to receive or refuse if they become incapacitated and unable to make decisions. In most states, a living will only goes into effect if an individual meets specific medical criteria.[27] The living will often includes instructions regarding life-sustaining measures, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), mechanical ventilation, and tube feeding.

Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare

It is impossible for an individual to document their preferences in a living will for every conceivable medical scenario that may occur. For this reason, it is essential for individuals to complete a durable power of attorney for healthcare. A durable power of attorney for healthcare (DPOAHC) is a person chosen to speak on one’s behalf if one becomes incapacitated. Typically, a primary health care power of attorney (POA) is identified with an alternative individual designated if the primary POA is unable or unwilling to do so. The health care POA is expected to make health care decisions for an individual they believe the person would make for themselves, based on wishes expressed in a living will or during previous conversations.[28]

It is essential for nurses to encourage clients to complete advance directives and have conversations with their designated POA about health care preferences, especially related to possible traumatic or end-of-life events that could require medical treatment decisions. Nurses can also dispel common misconceptions, such as these documents give the health care POA power to manage an individual’s finances. (A financial POA performs different functions than a health care POA and should be discussed with an attorney.)

After the advance directives are completed and included in the client’s medical record, the nurse has the responsibility to ensure they are appropriately incorporated into their care if they should become incapacitated.

View state-specific advance directives at the American Association of Retired Persons website.

Karen Ann Quinlan is an important figure in the United States’ history of defining life and death, a client’s privacy, and the state’s interest in preserving life and preventing murder. In April 1975, Karen Quinlan was 21 years old and became unresponsive after ingesting a combination of valium and alcohol while celebrating a friend’s birthday. She experienced respiratory failure, and although resuscitation efforts were successful, she suffered irreversible brain damage. She remained in a persistent vegetative state and became ventilator dependent. Her parents requested her physicians discontinue the ventilator because they believed it constituted extraordinary means to prolong her life. Her physicians denied their request out of concern of possible homicide charges based on New Jersey’s law. The Quinlans filed the first “right to die” lawsuit in September of 1975 but were denied by the New Jersey Superior Court in November. In March of 1976, the New Jersey Supreme Court determined the parent’s right to determine Karen’s medical treatment exceeded that of the state. Karen was discontinued from the ventilator six weeks later. When taken off the ventilator, Karen shocked many by continuing to breathe on her own. She lived in a coma for nine more years and succumbed to pneumonia on June 11, 1985.

-

- Sample Case: Nancy Beth Cruzan[30]

Nancy Cruzan is another important figure in the history of US “right to die” legal cases. At the age of 25, Nancy Cruzan was in a car accident on January 11, 1983. She never regained consciousness. After three years in a rehabilitation hospital, her parents began an eight-year battle in the courts to remove Nancy’s feeding tube. Nancy’s case was the first “right to die" case heard by the United States Supreme Court. Beyond allowing for the discontinuation of Nancy’s feeding tube, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all adults have the right to the following:1) Choose or refuse any medical or surgical intervention, including artificial nutrition and hydration.

2) Make advance directives and name a surrogate to make decisions on their behalf.

3) Surrogates can decide on treatment options even when all concerned are aware that such measures will hasten death, as long as causing death is not their intent.Nancy died nine days after removal of her feeding tube in December 1990. As a result of the Cruzan decision, the Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) was passed and took effect December 1, 1991. The act requires facilities to inform clients about their right to refuse treatment and to ask if they would like to prepare an advance directive.

- Sample Case: Nancy Beth Cruzan[30]

Sample Case: Terri Schaivo[31]

The Terri Schaivo case is a key case in history of advance directives in the United States because of its focus on the importance of having written advance directives to prevent family animosity, pain, and suffering. In 1990 Terri Schaivo was 26 years old. In her Florida home, she experienced a cardiac arrest thought to be a function of a low potassium level resulting from an eating disorder. She experienced severe anoxic brain injury and entered a persistent vegetative state. A PEG tube was inserted to provide medications, nutrition, and hydration. After three years, her husband refused further life-sustaining measures on her behalf, based on a statement Terri had once made, stating, “I don't want to be kept alive on a machine.” He expressed interest in obtaining a DNR order, withholding antibiotics for a urinary tract infection, and ultimately requested removal of the PEG tube. However, Terri’s parents never accepted the diagnosis of persistent vegetative state and vigorously opposed their son-in-law's decision and requests. Seven years of litigation generated 30 legal opinions, all supporting Michael Schiavo's right to make a decision on his wife's behalf. Terri died on March 31, 2005, following removal of her feeding tube.

Sara is a new graduate nurse orienting on the medical floor at a large teaching hospital. She has been working on the floor for two weeks and notices that many of the nurses provide shift handoff reports to one another outside of the patient rooms. Sara asks her preceptor why the nurses stand and report patient care information in the hallway. Her preceptor responds that this is the standard way staff can meet the agency guidelines for beside handoff reporting without "disturbing" patients while they are resting. Sara has concerns about this action on many levels. What legal repercussions might this "hallway reporting" have?

Sara is smart to identify that discussing patient care information in a hallway outside of patient rooms may jeopardize patient HIPAA protections and confidentiality. Sensitive patient information should never be discussed freely where others may overhear care information and details. Additionally, the act of bedside handoff reporting is meant to provide an inclusive environment for patients to participate with care staff in the report and information exchange. Discussing report details outside of the patient room does not actively include the patient in the bedside reporting procedure.

Sara is a new graduate nurse orienting on the medical floor at a large teaching hospital. She has been working on the floor for two weeks and notices that many of the nurses provide shift handoff reports to one another outside of the patient rooms. Sara asks her preceptor why the nurses stand and report patient care information in the hallway. Her preceptor responds that this is the standard way staff can meet the agency guidelines for beside handoff reporting without "disturbing" patients while they are resting. Sara has concerns about this action on many levels. What legal repercussions might this "hallway reporting" have?

Sara is smart to identify that discussing patient care information in a hallway outside of patient rooms may jeopardize patient HIPAA protections and confidentiality. Sensitive patient information should never be discussed freely where others may overhear care information and details. Additionally, the act of bedside handoff reporting is meant to provide an inclusive environment for patients to participate with care staff in the report and information exchange. Discussing report details outside of the patient room does not actively include the patient in the bedside reporting procedure.

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) established standard core competencies for effective interprofessional collaborative practice. The competencies guide the education of future health professionals with the necessary knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to collaboratively work together in providing client care. See Table 7.2 for a description of the four IPEC core competencies.[32] Each of these competencies will be further discussed in the following sections of this chapter.

Table 7.2. IPEC Core Competencies[33]

| Competency 1: Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice

Work with individuals of other professions to maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values. |

|---|

| Competency 2: Roles/Responsibilities

Use the knowledge of one’s own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of patients and to promote and advance the health of populations. |

| Competency 3: Interprofessional Communication

Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease. |

| Competency 4: Teams and Teamwork

Apply relationship-building values and the principles of team dynamics to perform effectively in different team roles to plan, deliver, and evaluate patient/population-centered care and population health programs and policies that are safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable. |