13.2 Musculoskeletal Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Skeleton

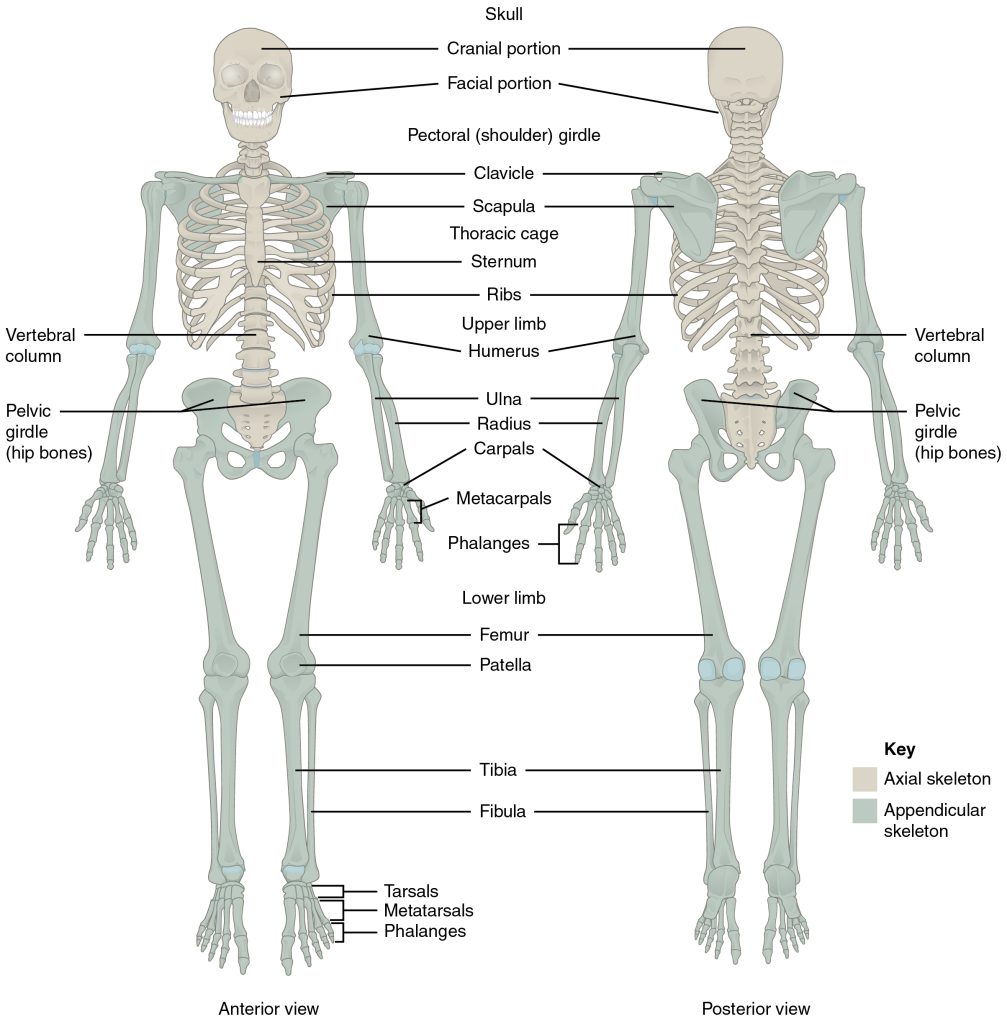

The skeleton is composed of 206 bones that provide the internal supporting structure of the body. See Figure 13.1[1] for an illustration of the major bones in the body. The bones of the lower limbs are adapted for weight-bearing support, stability, and walking. The upper limbs are highly mobile with large range of movements, along with the ability to easily manipulate objects with our hands and opposable thumbs.[2]

For additional information about the bones in the body, visit the OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology book.

Many different bones are connected together by ligaments. Most bones of the skill are held together by sutures, a narrow fibrous joint. Ligaments are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue that strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements of a joint while also limiting the range of these motions to prevent excessive or abnormal joint movements.[3]

Muscles

There are three types of muscle tissue: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Skeletal muscles are attached to the skeleton and produce movement, assist in maintaining posture, protect internal organs, and generate body heat. Skeletal muscles are voluntary, meaning a person is able to consciously control them, but they also depend on signals from the nervous system to work properly. Other types of muscles are involuntary and are controlled by the autonomic nervous system, such as the smooth muscle within our bronchioles.[4] Cardiac muscles are located only in the heart and are involuntary muscles that the autonomic nervous system controls. Smooth muscle makes up the organs, blood vessels, digestive tract, skin, and other areas and is controlled by the autonomic nervous system.

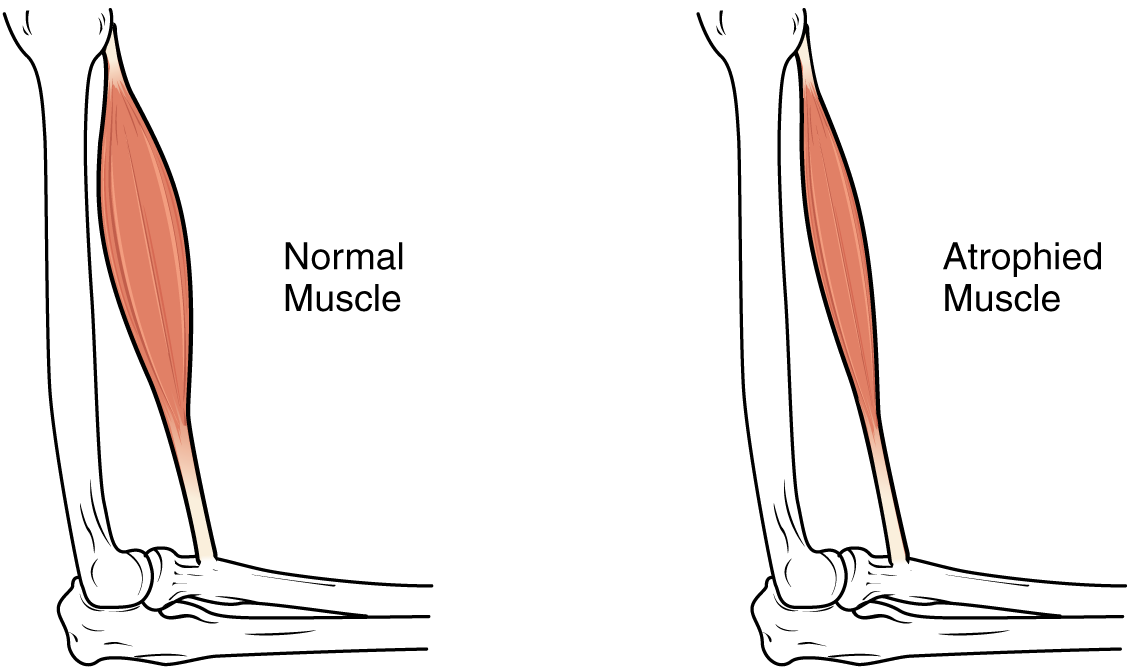

See Figure 13.2[5] for an illustration of skeletal muscle.

To move the skeleton, the tension created by the contraction of the skeletal muscles is transferred to the tendons, strong bands of dense, regular connective tissue that connect muscles to bones.[6]

For additional information about skeletal muscles, visit the OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology book.

Muscle Atrophy

Muscle atrophy is the thinning or loss of muscle tissue. See Figure 13.3[7] for an image of muscle atrophy. There are three types of muscle atrophy: physiologic, pathologic, and neurogenic.

Physiologic atrophy is caused by not using the muscles and can often be reversed with exercise and improved nutrition. People who are most affected by physiologic atrophy are those who:

- Have seated jobs, health problems that limit movement, or decreased activity levels

- Are bedridden

- Cannot move their limbs because of stroke or other brain disease

- Are in a place that lacks gravity, such as during space flights

Pathologic atrophy is seen with aging, starvation, and adverse effects of long-term use of corticosteroids. Neurogenic atrophy is the most severe type of muscle atrophy. It can be from an injured or diseased nerve that connects to the muscle. Examples of neurogenic atrophy are spinal cord injuries and polio.[8]

Although physiologic atrophy due to disuse can often be reversed with exercise, muscle atrophy caused by age is more complex. The effects of age-related atrophy are especially pronounced in people who are sedentary because the loss of muscle results in functional impairments such as trouble with walking, balance, and posture. These functional impairments can cause decreased quality of life and injuries due to falls.[9]

Joints

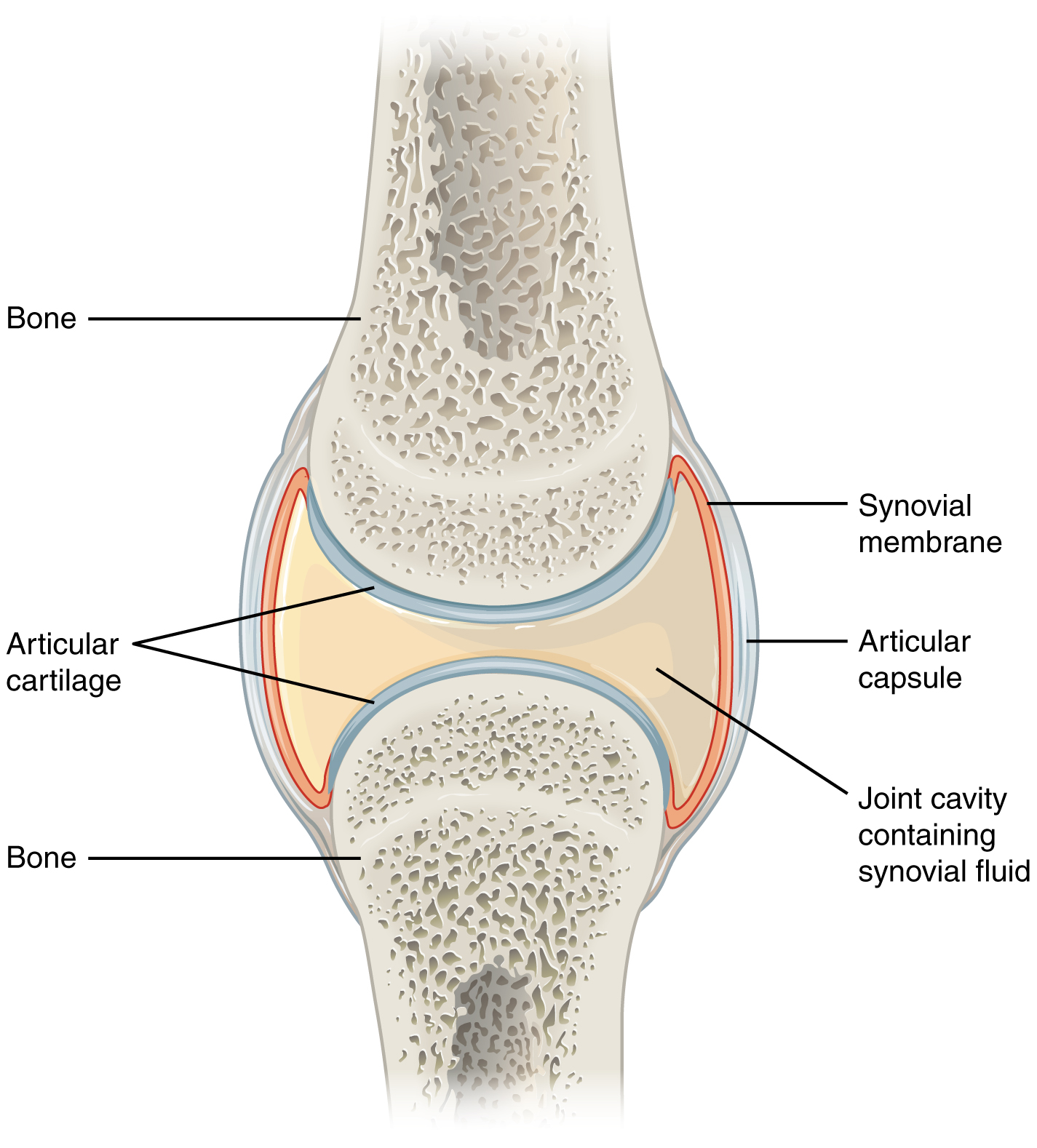

Joints are the location where bones come together. Many joints allow for movement between the bones. Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body. Synovial joints have a fluid-filled joint cavity where the articulating surfaces of the bones contact and move smoothly against each other. See Figure 13.4[10] for an illustration of a synovial joint. Articular cartilage is smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones where they come together and allows the bones to glide over each other with very little friction. Articular cartilage can be damaged by injury or normal wear and tear. Lining the inner surface of the articular capsule is a thin synovial membrane. The cells of this membrane secrete synovial fluid, a thick, slimy fluid that provides lubrication to further reduce friction between the bones of the joint.[11]

Types of Synovial Joints

There are six types of synovial joints. See Figure 13.5[12] for an illustration of the types of synovial joints. Some joints are relatively immobile but stable. Other joints have more freedom of movement but are at greater risk of injury. For example, the hinge joint of the knee allows flexion and extension, whereas the ball and socket joint of the hip and shoulder allows flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation. The knee, hip, and shoulder joints are commonly injured and are discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

Shoulder Joint

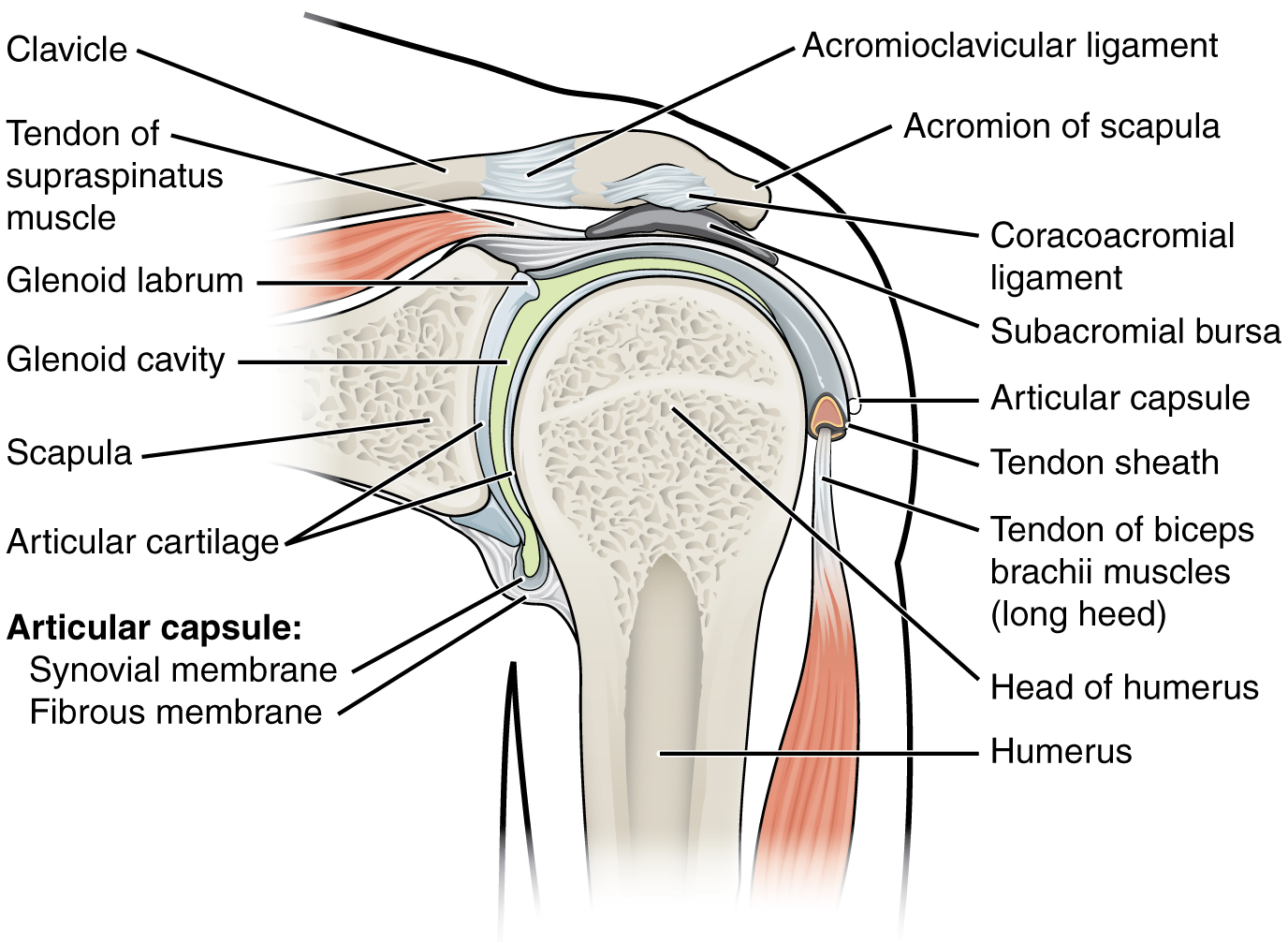

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the articulation between the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula. This joint has the largest range of motion of any joint in the body. See Figure 13.6[13] to review the anatomy of the shoulder joint. Injuries to the shoulder joint are common, especially during repetitive abductive use of the upper limb such as during throwing, swimming, or racquet sports.[14]

Hip Joint

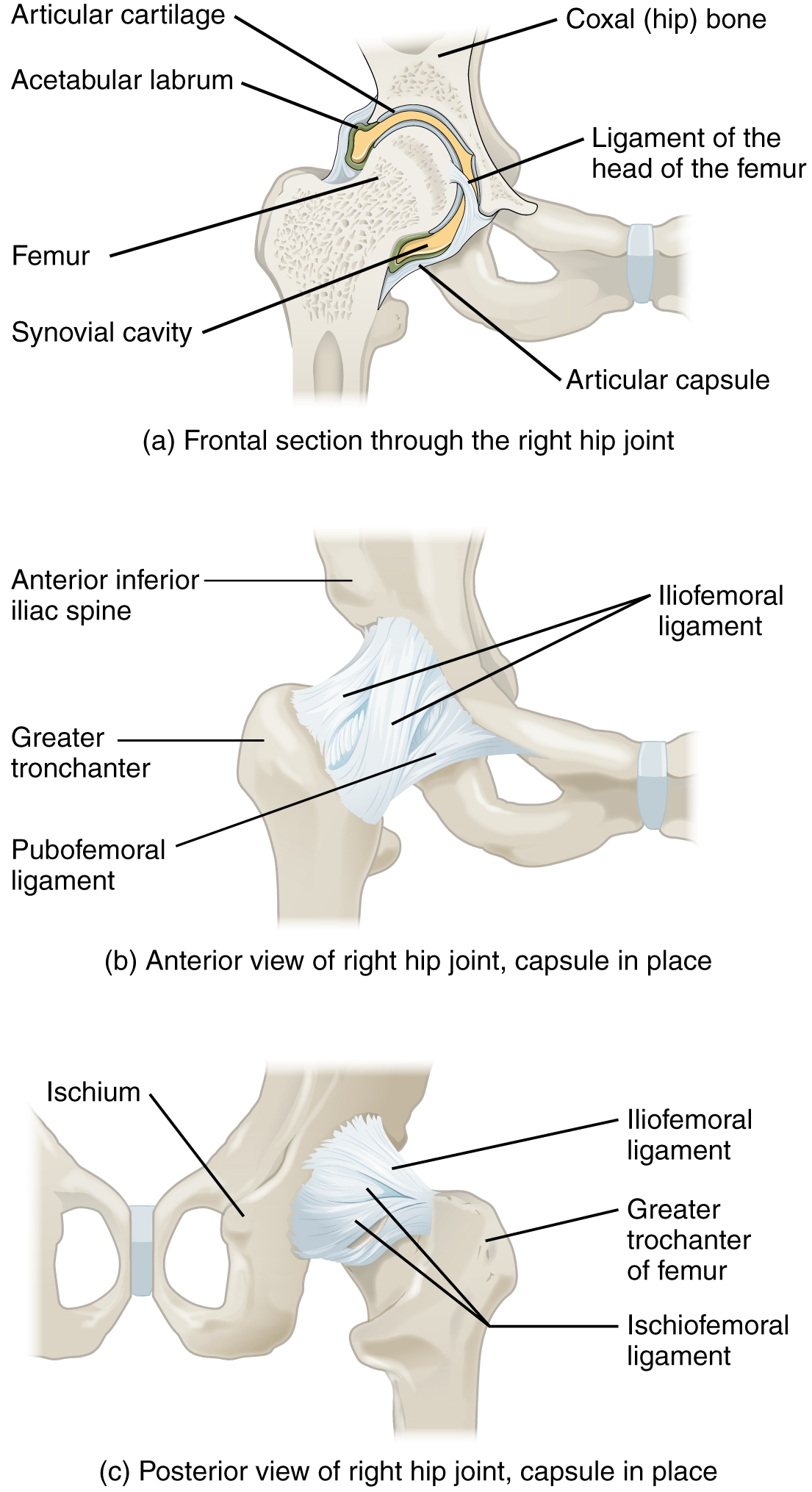

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the hip bone. The hip carries the weight of the body and thus requires strength and stability during standing and walking.[15]

See Figure 13.7[16] for an illustration of the hip joint.

A common hip injury in older adults, often referred to as a “broken hip,” is actually a fracture of the head of the femur. Hip fractures are commonly caused by falls.[17]

See more information about hip fractures under the “Common Musculoskeletal Conditions” section.

Knee Joint

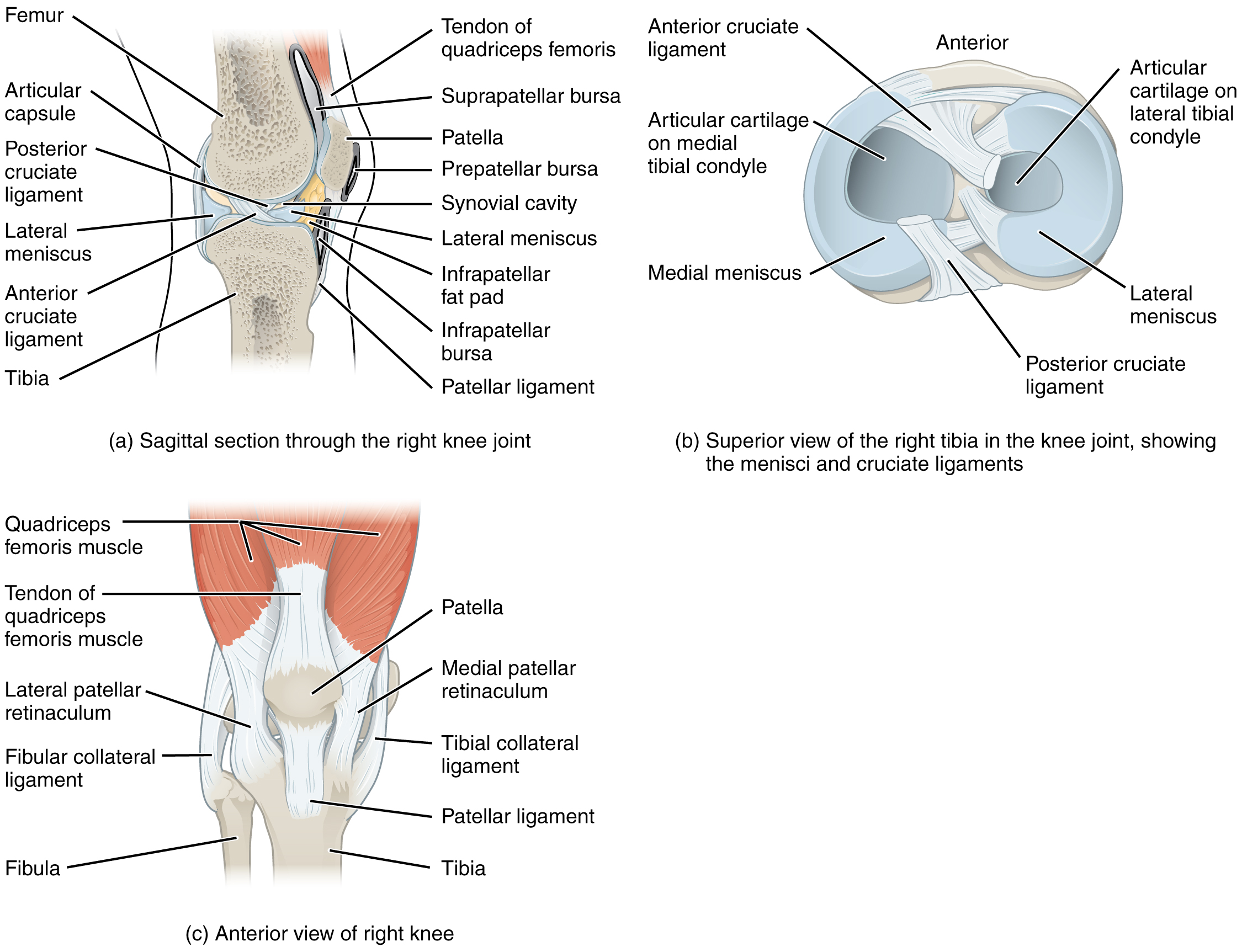

The knee functions as a hinge joint that allows flexion and extension of the leg. In addition, some rotation of the leg is available. See Figure 13.8[18] for an illustration of the knee joint. The knee is vulnerable to injuries associated with hyperextension, twisting, or blows to the medial or lateral side of the joint, particularly while weight-bearing.[19]

The knee joint has multiple ligaments that provide support, especially in the extended position. On the outside of the knee joint are the lateral collateral, medial collateral, and tibial collateral ligaments. The lateral collateral ligament is on the lateral side of the knee and spans from the lateral side of the femur to the head of the fibula. The medial collateral ligament runs from the medial side of the femur to the medial tibia. The tibial collateral ligament crosses the knee and is attached to the articular capsule and to the medial meniscus. In the fully extended knee position, both collateral ligaments are taut and stabilize the knee by preventing side-to-side or rotational motions between the femur and tibia.[20]

Inside the knee joint are the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament. These ligaments are anchored inferiorly to the tibia and run diagonally upward to attach to the inner aspect of a femoral condyle. The posterior cruciate ligament supports the knee when it is flexed and weight-bearing such as when walking downhill. The anterior cruciate ligament becomes tight when the knee is extended and resists hyperextension.[21]

The patella is a bone incorporated into the tendon of the quadriceps muscle, the large muscle of the anterior thigh. The patella protects the quadriceps tendon from friction against the distal femur. Continuing from the patella to the anterior tibia just below the knee is the patellar ligament. Acting via the patella and patellar ligament, the quadriceps is a powerful muscle that extends the leg at the knee and provides support and stabilization for the knee joint.

Located between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia are two articular discs, the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus. Each meniscus is a C-shaped fibrocartilage that provides padding between the bones.[22]

Joint Movements

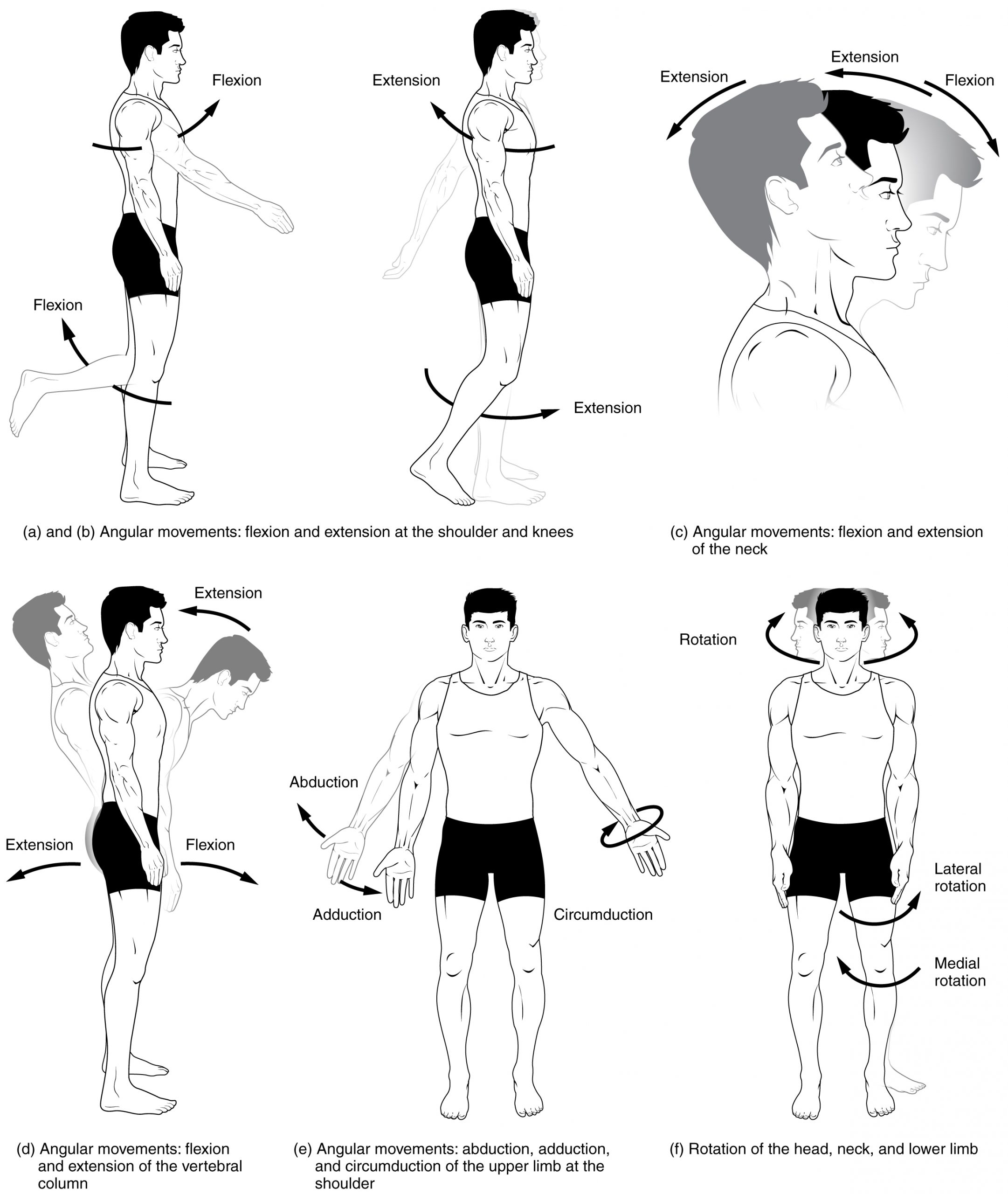

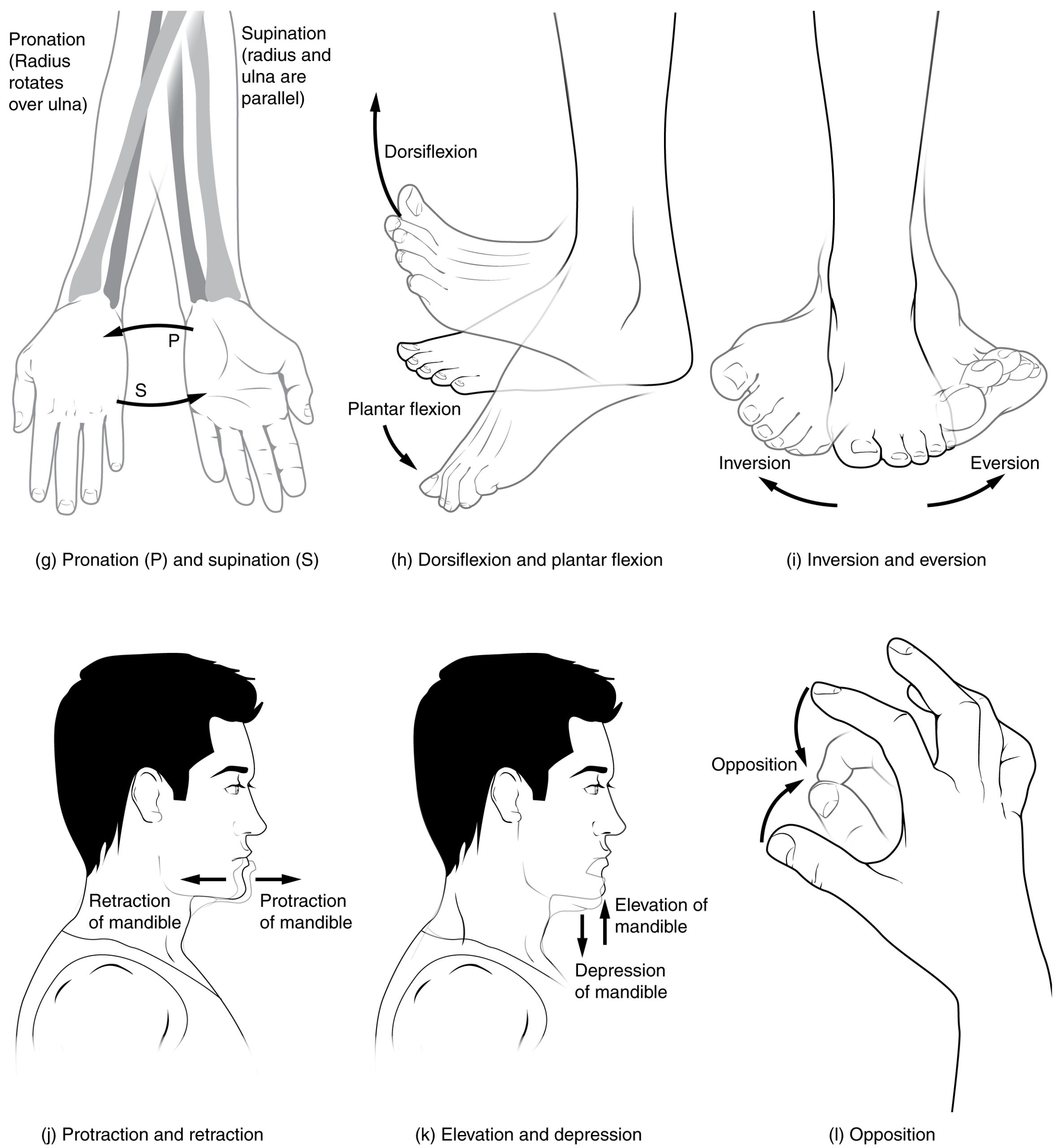

Several movements may be performed by synovial joints. Abduction is the movement away from the midline of the body. Adduction is the movement toward the middle line of the body. Extension is the straightening of limbs (increase in angle) at a joint. Flexion is bending the limbs (reduction of angle) at a joint. Rotation is a circular movement around a fixed point. See Figures 13.9[23] and 13.10[24] for images of the types of movements of different joints in the body.

Joint Sounds

Sounds that occur as joints are moving are often referred to as crepitus. There are many different types of sounds that can occur as a joint moves, and patients may describe these sounds as popping, snapping, catching, clicking, crunching, cracking, crackling, creaking, grinding, grating, and clunking. There are several potential causes of these noises such as bursting of tiny bubbles in the synovial fluid, snapping of ligaments, or a disease condition. While assessing joints, be aware that joint noises are common during activity and are usually painless and harmless, but if they are associated with an injury or are accompanied by pain or swelling, they should be reported to the health care provider for follow-up.[25]

View a supplementary video from Physitutors called Why Your Knees Crack | Joint Crepitations.[26]

- “701 Axial Skeleton-01.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/preface ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1105 Anterior and Posterior Views of Muscles.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1025 Atrophy.png” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-6-exercise-and-muscle-performance ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Muscle atrophy; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003188.htm ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “907_Synovial_Joints.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “909 Types of Synovial Joints.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “914 Shoulder Joint.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “916 Hip Joint.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “917 Knee Joint.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Body Movements I.jpg” by Tonye Ogele CNX is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Body Movements II.jpg” by Tonye Ogele CNX is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Song, S. J., Park, C. H., Liang, H., & Kim, S. J. (2018). Noise around the knee. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery, 10(1), 1-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.4055%2Fcios.2018.10.1.1 ↵

- Physitutors. (2017, March 25). Why your knees crack | Joint crepitations [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/NQOZZgh5z8I ↵

Prioritization of patient care should be grounded in critical thinking rather than just a checklist of items to be done. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow."[1] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs. It can be challenging for a novice nurse to change their mindset regarding their established “plan” for the day, but the sooner a nurse recognizes prioritization is dictated by their patients’ needs, the less frustration the nurse might experience. Prioritization strategies include collection of information and utilization of clinical reasoning to determine the best course of action. Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[2] Clinical reasoning is fostered within nurses when they are challenged to integrate data in various contexts. The clinical reasoning cycle begins when nurses first consider a client situation and progress to collecting cues and information. As nurses process the information, they begin to identify problems and establish realistic goals. They then take appropriate actions and evaluate outcomes. Finally, they reflect upon the process and the learning that has occurred. The reflection piece is critical for solidifying or changing future actions and developing knowledge.

When nurses use critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills, they set forth on a purposeful course of intervention to best meet patient-care needs. Rather than focusing on one’s own priorities, nurses utilizing critical thinking and reasoning skills recognize their actions must be responsive to their patients. For example, a nurse using critical thinking skills understands that scheduled morning medications for their patients may be late if one of the patients on their care team suddenly develops chest pain. Many actions may be added or removed from planned activities throughout the shift based on what is occurring holistically on the patient-care team.

Additionally, in today’s complex health care environment, it is important for the novice nurse to recognize the realities of the current health care environment. Patients have become increasingly complex in their health care needs, and organizations are often challenged to meet these care needs with limited staffing resources. It can become easy to slip into the mindset of disenchantment with the nursing profession when first assuming the reality of patient-care assignments as a novice nurse. The workload of a nurse in practice often looks and feels quite different than that experienced as a nursing student. As a nursing student, there may have been time for lengthy conversations with patients and their family members, ample time to chart, and opportunities to offer personal cares, such as a massage or hair wash. Unfortunately, in the time-constrained realities of today's health care environment, novice nurses should recognize that even though these “extra” tasks are not always possible, they can still provide quality, safe patient care using the “CURE” prioritization framework. Rather than feeling frustrated about “extras” that cannot be accomplished in time-constrained environments, it is vital to use prioritization strategies to ensure appropriate actions are taken to complete what must be done. With increased clinical experience, a novice nurse typically becomes more comfortable with prioritizing and reprioritizing care.

Prioritization of patient care should be grounded in critical thinking rather than just a checklist of items to be done. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow."[3] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs. It can be challenging for a novice nurse to change their mindset regarding their established “plan” for the day, but the sooner a nurse recognizes prioritization is dictated by their patients’ needs, the less frustration the nurse might experience. Prioritization strategies include collection of information and utilization of clinical reasoning to determine the best course of action. Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[4] Clinical reasoning is fostered within nurses when they are challenged to integrate data in various contexts. The clinical reasoning cycle begins when nurses first consider a client situation and progress to collecting cues and information. As nurses process the information, they begin to identify problems and establish realistic goals. They then take appropriate actions and evaluate outcomes. Finally, they reflect upon the process and the learning that has occurred. The reflection piece is critical for solidifying or changing future actions and developing knowledge.

When nurses use critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills, they set forth on a purposeful course of intervention to best meet patient-care needs. Rather than focusing on one’s own priorities, nurses utilizing critical thinking and reasoning skills recognize their actions must be responsive to their patients. For example, a nurse using critical thinking skills understands that scheduled morning medications for their patients may be late if one of the patients on their care team suddenly develops chest pain. Many actions may be added or removed from planned activities throughout the shift based on what is occurring holistically on the patient-care team.

Additionally, in today’s complex health care environment, it is important for the novice nurse to recognize the realities of the current health care environment. Patients have become increasingly complex in their health care needs, and organizations are often challenged to meet these care needs with limited staffing resources. It can become easy to slip into the mindset of disenchantment with the nursing profession when first assuming the reality of patient-care assignments as a novice nurse. The workload of a nurse in practice often looks and feels quite different than that experienced as a nursing student. As a nursing student, there may have been time for lengthy conversations with patients and their family members, ample time to chart, and opportunities to offer personal cares, such as a massage or hair wash. Unfortunately, in the time-constrained realities of today's health care environment, novice nurses should recognize that even though these “extra” tasks are not always possible, they can still provide quality, safe patient care using the “CURE” prioritization framework. Rather than feeling frustrated about “extras” that cannot be accomplished in time-constrained environments, it is vital to use prioritization strategies to ensure appropriate actions are taken to complete what must be done. With increased clinical experience, a novice nurse typically becomes more comfortable with prioritizing and reprioritizing care.

Time management is not an unfamiliar concept to nursing students because many students are balancing time demands related to work, family, and school obligations. To determine where time should be allocated, prioritization processes emerge. Although the prioritization frameworks of nursing may be different than those used as a student, the concept of prioritization remains the same. Despite the context, prioritization is essentially using a structure to organize tasks to ensure the most critical tasks are completed first and then identify what to move onto next. To truly maximize time management, in addition to prioritization, individuals should be organized, strive for accuracy, minimize waste, mobilize resources, and delegate when appropriate.

Time management is one of the greatest challenges that nurses face in their busy workday. As novice nurses develop their practice, it is important to identify organizational strategies to ensure priority tasks are completed and time is optimized. Each nurse develops a personal process for organizing information and structuring the timing of their assessments, documentation, medication administration, interventions, and patient education. However, one must always remember that this process and structure must be flexible because in a moment’s time, a patient’s condition can change, requiring a reprioritization of care. An organizational tool is important to guide a nurse’s daily task progression. Organizational tools may be developed individually by the nurse or may be recommended by the organization. Tools can be rudimentary in nature, such as a simple time column format outlining care activities planned throughout the shift, or more complex and integrated within an organization’s electronic medical record. No matter the format, an organizational tool is helpful to provide structure and guide progression toward task achievement.

In addition to using an organizational tool, novice nurses should utilize other time management strategies to optimize their time. For example, assessments can start during bedside handoff report, such as what fluids and medications are running and what will need to be replaced soon. Take a moment after handoff reports to prioritize which patients you will see first during your shift. Other strategies such as grouping tasks, gathering appropriate equipment prior to initiating nursing procedures, and gathering assessment information while performing tasks are helpful in minimizing redundancy and increasing efficiency. For example, observe an experienced nurse providing care and note the efficient processes they use. They may conduct an assessment, bring in morning medications, flush an IV line, collect a morning blood glucose level, and provide patient education about medications all during one patient encounter. Efficiency becomes especially important if the patient has transmission-based precautions and the time spent donning and doffing PPE are considered. The realities of the time-constrained health care environments often necessitate clustering tasks to ensure that all patient-care tasks are completed. Furthermore, nurses who do not manage their time effectively may inadvertently place their patients at risk as a result of delayed care.[5] Effective time management benefits both the patient and the nursing staff.

Time estimation is an additional helpful strategy to facilitate time management. Time estimation involves the review of planned tasks for the day and allocating time estimated to complete the task. Time estimation is especially helpful for novice nurses as they begin to structure and prioritize their shift based on the list of tasks that are required.[6] For example, estimating the time it will take to perform an assessment and administer morning medications to one patient allows the nurse to better plan when to complete the dressing change on another patient. Without using time estimation, the nurse may attempt to group all care tasks with the morning assessments and not leave themselves enough time to administer morning medications within the desired administration time window. Additionally, working in a time-constrained environment without using time estimation strategies increases the likelihood of performing tasks “in a rush” and subsequently increasing the potential for error.

Who’s On My Team?

One of the most critical strategies to enhance time management is to mobilize the resources of the nursing team. The nursing care team includes advanced practice registered nurses (APRN), registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VN), and assistive personnel (AP). AP (formerly referred to as unlicensed assistive personnel [UAP]) include, but are not limited to, certified nursing assistants or aides (CNA), patient-care technicians (PCT), certified medical assistants (CMA), certified medication aides, and home health aides.[7] Each care environment may have a blend of staff, and it is important to understand the legalities associated with the scope and role of each member and what can be safely and appropriately delegated to other members of the team. For example, assistive personnel may be able to assist with ambulating a patient in the hallway, but they would not be able to help administer morning medications. Dividing tasks appropriately among nursing team members can help ensure that the required tasks are completed and individual energies are best allocated to meet patient needs. The nursing care team and requirements around the process of delegation are explored in detail in the "Delegation and Supervision" chapter.

Time management is not an unfamiliar concept to nursing students because many students are balancing time demands related to work, family, and school obligations. To determine where time should be allocated, prioritization processes emerge. Although the prioritization frameworks of nursing may be different than those used as a student, the concept of prioritization remains the same. Despite the context, prioritization is essentially using a structure to organize tasks to ensure the most critical tasks are completed first and then identify what to move onto next. To truly maximize time management, in addition to prioritization, individuals should be organized, strive for accuracy, minimize waste, mobilize resources, and delegate when appropriate.

Time management is one of the greatest challenges that nurses face in their busy workday. As novice nurses develop their practice, it is important to identify organizational strategies to ensure priority tasks are completed and time is optimized. Each nurse develops a personal process for organizing information and structuring the timing of their assessments, documentation, medication administration, interventions, and patient education. However, one must always remember that this process and structure must be flexible because in a moment’s time, a patient’s condition can change, requiring a reprioritization of care. An organizational tool is important to guide a nurse’s daily task progression. Organizational tools may be developed individually by the nurse or may be recommended by the organization. Tools can be rudimentary in nature, such as a simple time column format outlining care activities planned throughout the shift, or more complex and integrated within an organization’s electronic medical record. No matter the format, an organizational tool is helpful to provide structure and guide progression toward task achievement.

In addition to using an organizational tool, novice nurses should utilize other time management strategies to optimize their time. For example, assessments can start during bedside handoff report, such as what fluids and medications are running and what will need to be replaced soon. Take a moment after handoff reports to prioritize which patients you will see first during your shift. Other strategies such as grouping tasks, gathering appropriate equipment prior to initiating nursing procedures, and gathering assessment information while performing tasks are helpful in minimizing redundancy and increasing efficiency. For example, observe an experienced nurse providing care and note the efficient processes they use. They may conduct an assessment, bring in morning medications, flush an IV line, collect a morning blood glucose level, and provide patient education about medications all during one patient encounter. Efficiency becomes especially important if the patient has transmission-based precautions and the time spent donning and doffing PPE are considered. The realities of the time-constrained health care environments often necessitate clustering tasks to ensure that all patient-care tasks are completed. Furthermore, nurses who do not manage their time effectively may inadvertently place their patients at risk as a result of delayed care.[8] Effective time management benefits both the patient and the nursing staff.

Time estimation is an additional helpful strategy to facilitate time management. Time estimation involves the review of planned tasks for the day and allocating time estimated to complete the task. Time estimation is especially helpful for novice nurses as they begin to structure and prioritize their shift based on the list of tasks that are required.[9] For example, estimating the time it will take to perform an assessment and administer morning medications to one patient allows the nurse to better plan when to complete the dressing change on another patient. Without using time estimation, the nurse may attempt to group all care tasks with the morning assessments and not leave themselves enough time to administer morning medications within the desired administration time window. Additionally, working in a time-constrained environment without using time estimation strategies increases the likelihood of performing tasks “in a rush” and subsequently increasing the potential for error.

Who’s On My Team?

One of the most critical strategies to enhance time management is to mobilize the resources of the nursing team. The nursing care team includes advanced practice registered nurses (APRN), registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VN), and assistive personnel (AP). AP (formerly referred to as unlicensed assistive personnel [UAP]) include, but are not limited to, certified nursing assistants or aides (CNA), patient-care technicians (PCT), certified medical assistants (CMA), certified medication aides, and home health aides.[10] Each care environment may have a blend of staff, and it is important to understand the legalities associated with the scope and role of each member and what can be safely and appropriately delegated to other members of the team. For example, assistive personnel may be able to assist with ambulating a patient in the hallway, but they would not be able to help administer morning medications. Dividing tasks appropriately among nursing team members can help ensure that the required tasks are completed and individual energies are best allocated to meet patient needs. The nursing care team and requirements around the process of delegation are explored in detail in the "Delegation and Supervision" chapter.

Sam is a novice nurse who is reporting to work for his 0600 shift on the medical telemetry/progressive care floor. He is waiting to receive handoff report from the night shift nurse for his assigned patients. The information that he has received thus far regarding his patient assignment includes the following:

- Room 501: 64-year-old patient admitted last night with heart failure exacerbation. Patient received furosemide 80mg IV push at 2000 with 1600 mL urine output. He is receiving oxygen via nasal cannula at 2L/minute. According to the night shift aide, he has been resting comfortably overnight.

- Room 507: 74-year-old patient admitted yesterday for possible cardioversion due to new onset of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and is scheduled for transesophageal echocardiogram and possible cardioversion at 1000.

- Room 512: 82-year-old patient who is scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery today at 0700 and is receiving an insulin infusion.

- Room 536: 72-year-old patient who had a negative heart catheterization yesterday but experienced a groin bleed; plans for discharge this morning.

Based on the limited information Sam has thus far, he begins to prioritize his activities for the morning. With what is known thus far regarding his patient assignment, whom might Sam plan to see first and why? What principles of prioritization might be applied?

Although Sam would benefit from hearing a full report on his patients and reviewing the patient charts, he can already begin to engage in strategies for prioritization. Based on the information that has been shared thus far, Sam determines that none of the patients assigned to him are experiencing critical or urgent needs. All the patients' basic physiological needs are being met, but many have actual clinical concerns. Based on the time constraint with scheduled surgery and the insulin infusion for the patient in Room 512, this patient should take priority in Sam's assessments. It is important for Sam to ensure that this patient's pre-op checklist is complete, and he is stable with the infusion prior to transferring him for surgery. Although Sam may later receive information that alters this priority setting, based on the information he has thus far, he has utilized prioritization principles to make an informed decision.

Sam is a novice nurse who is reporting to work for his 0600 shift on the medical telemetry/progressive care floor. He is waiting to receive handoff report from the night shift nurse for his assigned patients. The information that he has received thus far regarding his patient assignment includes the following:

- Room 501: 64-year-old patient admitted last night with heart failure exacerbation. Patient received furosemide 80mg IV push at 2000 with 1600 mL urine output. He is receiving oxygen via nasal cannula at 2L/minute. According to the night shift aide, he has been resting comfortably overnight.

- Room 507: 74-year-old patient admitted yesterday for possible cardioversion due to new onset of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and is scheduled for transesophageal echocardiogram and possible cardioversion at 1000.

- Room 512: 82-year-old patient who is scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery today at 0700 and is receiving an insulin infusion.

- Room 536: 72-year-old patient who had a negative heart catheterization yesterday but experienced a groin bleed; plans for discharge this morning.

Based on the limited information Sam has thus far, he begins to prioritize his activities for the morning. With what is known thus far regarding his patient assignment, whom might Sam plan to see first and why? What principles of prioritization might be applied?

Although Sam would benefit from hearing a full report on his patients and reviewing the patient charts, he can already begin to engage in strategies for prioritization. Based on the information that has been shared thus far, Sam determines that none of the patients assigned to him are experiencing critical or urgent needs. All the patients' basic physiological needs are being met, but many have actual clinical concerns. Based on the time constraint with scheduled surgery and the insulin infusion for the patient in Room 512, this patient should take priority in Sam's assessments. It is important for Sam to ensure that this patient's pre-op checklist is complete, and he is stable with the infusion prior to transferring him for surgery. Although Sam may later receive information that alters this priority setting, based on the information he has thus far, he has utilized prioritization principles to make an informed decision.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activities are provided as immediate feedback.)

- The nurse is conducting an assessment on a 70-year-old male client who was admitted with atrial fibrillation. The client has a history of hypertension and Stage 2 chronic kidney disease. The nurse begins the head-to-toe assessment and notes the patient is having difficulty breathing and is complaining about chest discomfort. The client states, “It feels as if my heart is going to pound out of my chest and I feel dizzy.” The nurse begins the head-to-toe assessment and documents the findings. Client assessment findings are presented in the table below. Select the assessment findings requiring immediate follow-up by the nurse.

Vital Signs

| Temperature | 98.9 °F (37.2°C) |

|---|---|

| Heart Rate | 182 beats/min |

| Respirations | 36 breaths/min |

| Blood Pressure | 152/90 mm Hg |

| Oxygen Saturation | 88% on room air |

| Capillary Refill Time | >3 |

| Pain | 9/10 chest discomfort |

| Physical Assessment Findings | |

|---|---|

| Glasgow Coma Scale Score | 14 |

| Level of Consciousness | Alert |

| Heart Sounds | Irregularly regular |

| Lung Sounds | Clear bilaterally anterior/posterior |

| Pulses-Radial | Rapid/bounding |

| Pulses-Pedal | Weak |

| Bowel Sounds | Present and active x 4 |

| Edema | Trace bilateral lower extremities |

| Skin | Cool, clammy |

2. The following nursing actions may or may not be required at this time based on the assessment findings. Indicate whether the actions are "Indicated" (i.e., appropriate or necessary), "Contraindicated" (i.e., could be harmful), or "Nonessential" (i.e., makes no difference or are not necessary).

| Nursing Action | Indicated | Contraindicated | Nonessential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apply oxygen at 2 liters per nasal cannula. | |||

| Call imaging for a STAT lung CT. | |||

| Perform the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale Neurologic Exam. | |||

| Obtain a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP). | |||

| Obtain a STAT EKG. | |||

| Raise the head-of-bed to less than 10 degrees. | |||

| Establish patent IV access. | |||

| Administer potassium 20 mEq IV push STAT. |

3. The CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to help guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras.

You are the nurse caring for the patients in the following table. For each patient, indicate if this is a "critical," "urgent," "routine," or "extra" need.

<td">

| Critical | Urgent | Routine | Extra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient exhibits new left-sided facial droop | ||||

| Patient reports 9/10 acute pain and requests PRN pain medication | ||||

| Patient with BP 120/80 and regular heart rate of 68 has scheduled dose of oral amlodipine | ||||

| Patient with insomnia requests a back rub before bedtime | ||||

| Patient has a scheduled dressing change for a pressure ulcer on their coccyx |

||||

| Patient is exhibiting new shortness of breath and altered mental status | ||||

| Patient with fall risk precautions ringing call light for assistance to the restroom for a bowel movement |

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[11]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activities are provided as immediate feedback.)

- The nurse is conducting an assessment on a 70-year-old male client who was admitted with atrial fibrillation. The client has a history of hypertension and Stage 2 chronic kidney disease. The nurse begins the head-to-toe assessment and notes the patient is having difficulty breathing and is complaining about chest discomfort. The client states, “It feels as if my heart is going to pound out of my chest and I feel dizzy.” The nurse begins the head-to-toe assessment and documents the findings. Client assessment findings are presented in the table below. Select the assessment findings requiring immediate follow-up by the nurse.

Vital Signs

| Temperature | 98.9 °F (37.2°C) |

|---|---|

| Heart Rate | 182 beats/min |

| Respirations | 36 breaths/min |

| Blood Pressure | 152/90 mm Hg |

| Oxygen Saturation | 88% on room air |

| Capillary Refill Time | >3 |

| Pain | 9/10 chest discomfort |

| Physical Assessment Findings | |

|---|---|

| Glasgow Coma Scale Score | 14 |

| Level of Consciousness | Alert |

| Heart Sounds | Irregularly regular |

| Lung Sounds | Clear bilaterally anterior/posterior |

| Pulses-Radial | Rapid/bounding |

| Pulses-Pedal | Weak |

| Bowel Sounds | Present and active x 4 |

| Edema | Trace bilateral lower extremities |

| Skin | Cool, clammy |

2. The following nursing actions may or may not be required at this time based on the assessment findings. Indicate whether the actions are "Indicated" (i.e., appropriate or necessary), "Contraindicated" (i.e., could be harmful), or "Nonessential" (i.e., makes no difference or are not necessary).

| Nursing Action | Indicated | Contraindicated | Nonessential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apply oxygen at 2 liters per nasal cannula. | |||

| Call imaging for a STAT lung CT. | |||

| Perform the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale Neurologic Exam. | |||

| Obtain a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP). | |||

| Obtain a STAT EKG. | |||

| Raise the head-of-bed to less than 10 degrees. | |||

| Establish patent IV access. | |||

| Administer potassium 20 mEq IV push STAT. |

3. The CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to help guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras.

You are the nurse caring for the patients in the following table. For each patient, indicate if this is a "critical," "urgent," "routine," or "extra" need.

<td">

| Critical | Urgent | Routine | Extra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient exhibits new left-sided facial droop | ||||

| Patient reports 9/10 acute pain and requests PRN pain medication | ||||

| Patient with BP 120/80 and regular heart rate of 68 has scheduled dose of oral amlodipine | ||||

| Patient with insomnia requests a back rub before bedtime | ||||

| Patient has a scheduled dressing change for a pressure ulcer on their coccyx |

||||

| Patient is exhibiting new shortness of breath and altered mental status | ||||

| Patient with fall risk precautions ringing call light for assistance to the restroom for a bowel movement |

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[12]

ABCs: Airway, breathing, and circulation.

Actual problems: Nursing problems currently occurring with the patient.

Acuity: The level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition.

Acuity-rating staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments that reflects the individualized nursing care required for different types of patients.

Acute conditions: Conditions having a sudden onset.

Chronic conditions: Conditions that have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time.

Clinical reasoning: “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[13]

Critical thinking: A broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”[14]

CURE hierarchy: A strategy for prioritization based on identifying “critical” needs, “urgent” needs, “routine” needs, and “extras.”

Data cues: Pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition.

Expected conditions: Conditions that are likely to occur or anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Prioritization strategies often reflect the foundational elements of physiological needs and safety and progress toward higher levels.

Ratio-based staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments in terms of one nurse caring for a set number of patients.

Risk problem: A nursing problem that reflects that a patient may experience a problem but does not currently have signs reflecting the problem is actively occurring.

Time estimation: A prioritization strategy including the review of planned tasks and allocation of time believed to be required to complete each task.

Time scarcity: A feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against you.

Unexpected conditions: Conditions that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury.

ABCs: Airway, breathing, and circulation.

Actual problems: Nursing problems currently occurring with the patient.

Acuity: The level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition.

Acuity-rating staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments that reflects the individualized nursing care required for different types of patients.

Acute conditions: Conditions having a sudden onset.

Chronic conditions: Conditions that have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time.

Clinical reasoning: “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[15]

Critical thinking: A broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”[16]

CURE hierarchy: A strategy for prioritization based on identifying “critical” needs, “urgent” needs, “routine” needs, and “extras.”

Data cues: Pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition.

Expected conditions: Conditions that are likely to occur or anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Prioritization strategies often reflect the foundational elements of physiological needs and safety and progress toward higher levels.

Ratio-based staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments in terms of one nurse caring for a set number of patients.

Risk problem: A nursing problem that reflects that a patient may experience a problem but does not currently have signs reflecting the problem is actively occurring.

Time estimation: A prioritization strategy including the review of planned tasks and allocation of time believed to be required to complete each task.

Time scarcity: A feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against you.

Unexpected conditions: Conditions that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury.

Blood-tinged mucus secretions from the lungs.

The first stage of wound healing when clotting factors are released to form clots to stop the bleeding.