11.9 Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

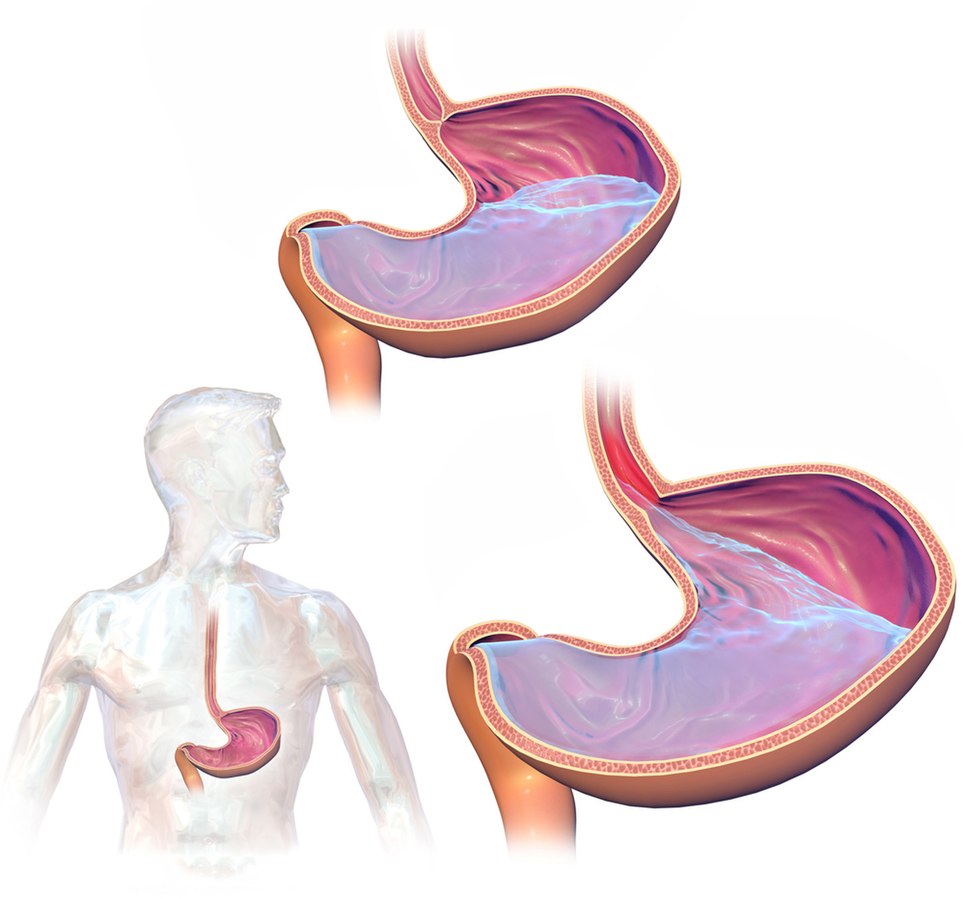

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when stomach contents flow backwards into the esophagus. GERD is a common, chronic disorder that develops in about 20% of adults in the United States.[1] Please see Figure 11.30[2] for an image of what occurs with GERD.

GERD can be classified into three different types, based on whether or not damage is occurring to the esophagus: nonerosive reflux disease (no damage to the esophagus), erosive esophagitis (formation of ulcers or erosions in the esophagus), and Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus is further described in the “Pathophysiology” subsection.[3]

Common risk factors for the development of GERD include the following[4]:

- Poor muscle tone in the lower esophageal sphincter

- Hiatal hernia

- Slow gastric contents emptying

- Obesity

- Hiatal hernia

- Age over 50 years old

- Tobacco usage

- Excessive alcohol use

- Pregnancy

- Low socioeconomic status

- Medications such as calcium channel blockers, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, NSAIDs/aspirin, some antidepressants, albuterol, and nitroglycerin

Pathophysiology

There are several abnormalities that can cause GERD, such as impaired lower esophageal sphincter (LES) tone, the presence of a hiatal hernia, impaired esophageal mucosa, and altered esophageal peristalsis.[5]

The LES is a ring of smooth muscle located between the esophagus and stomach to prevent backward flow of stomach contents. In clients who do not have GERD, the LES is a high-pressure area that only opens when food is present, allowing food to flow to enter the lower pressure area of the stomach. However, in clients with GERD, the LES may inappropriately relax, allowing stomach contents to flow backwards into the esophagus.[6]

A hiatal hernia is a condition in which the upper part of the stomach abnormally bulges through the hiatus of the diaphragm. When there is laxity in this hiatus, gastric content can back up into the esophagus.[7] Read more about hiatal hernias in the “Hernia” section of this chapter.

Esophageal mucosa normally functions as a protective defensive barrier against acid gastric contents, but with repeated exposure to stomach contents (which are highly acidic), the mucosa can become damaged. Clients with chronic GERD can develop Barrett’s esophagus. Chronic exposure to acidic stomach contents causes squamous epithelial cells that line the esophagus to transition into columnar epithelium, also known as Barrett’s epithelium. Barrett’s epithelium is more resistant to acid exposure but can become cancerous. Therefore, Barrett’s esophagus is considered a precancerous condition that is closely monitored.[8],[9]

Normally, the acidic gastric contents that enter the esophagus are cleared by frequent esophageal peristalsis and neutralized by salivary bicarbonate. Clients with GERD may have impaired esophageal peristalsis, leading to decreased clearance of gastric contents, resulting in reflux symptoms and mucosal damage.[10]

Assessment

Physical Exam

The most common symptoms of GERD are heartburn and regurgitation of gastric contents. Heartburn is defined as a retrosternal burning sensation or discomfort that may radiate into the neck and typically occurs after the ingestion of meals or when in a reclined position. Regurgitation refers to backwards flow of acidic gastric contents into the esophagus or mouth. Clients may also have difficult or painful swallowing, nausea, epigastric area pain, and increased belching. Some clients have atypical symptoms of GERD such as chest pain, persistent coughing, new-onset asthma, laryngitis, dental cavities, or a hoarse voice.[11]

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

GERD is typically diagnosed based on clinical signs and symptoms or by trialing a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) medication to determine if symptoms improve with treatment. In clients with significant symptoms, such as difficult or painful swallowing, reduced red blood counts, hematemesis, or unintended weight loss, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) may be performed to rule out complications of GERD such as erosions, Barrett’s esophagus, narrowing of the esophagus (caused by scar tissue formation), and esophageal cancer.[12] To review information on an EGD, please visit the “Common Laboratory and/or Diagnostic Tests” subsection of the “General Assessment of the Gastrointestinal System.”

In clients with GERD whose symptoms do not respond to medications, health care providers may order ambulatory esophageal reflux monitoring. This test entails inserting a catheter into the client’s nose with the distal tip near the LES. The catheter is used to monitor acid levels at the LES and help link the occurrence of symptoms with the presence of high acid levels.[13]

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing priorities for those suffering from GERD include symptom management, lifestyle changes, dietary education, and preventing complications.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with GERD are created based on the specific needs of the client, their signs and symptoms, and the etiology of the disorder. These nursing diagnoses guide the creation of client specific care plans that encompass client outcomes and nursing interventions, as well the evaluation of those outcomes. These individualized care plans then serve as a guide for client treatment.

Common nursing diagnoses for clients diagnosed with GERD are as follows[14],[15],[16]:

- Acute Pain

- Deficient Knowledge

- Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements

- Impaired Tissue Integrity

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification encompasses the creation of short- and long-term goals for the client. These goals are used to create expected outcome statements that are based on the specific needs of the client. Expected outcomes should be specific, measurable, and realistic. These outcomes should be achievable within a set time frame based on the application of appropriate nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes include the following:

- The client will rate their pain at 3 or less on a scale of 0 to 10 within 24 hours.

- The client will verbalize three lifestyle modifications that will help reduce the prevalence of GERD symptoms after the teaching session.

- The client will achieve a weight within a healthy range appropriate for their height within six months.

- The client will verbalize the importance of medication adherence to prevent complications by the end of the teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical treatment for GERD can be categorized as lifestyle changes, medication therapy, and surgical management.[17]

Lifestyle Changes

Lifestyle changes are typically the first step for treating GERD. The client is taught to stop consuming food three hours before bed and to elevate the head of the bed if possible. Clients are also taught to modify their diet to reduce GERD symptoms. Although there is some disagreement on the necessities of eliminating certain foods, clients are typically taught to avoid chocolate, caffeine, coffee, heavily spiced foods, foods with high citrus content, and carbonated beverages. If the client is obese, weight loss is encouraged.[18]

Medications

If lifestyle changes do not effectively manage GERD symptoms, medications are prescribed. Commonly prescribed classes of medications are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), and prokinetics. PPIs are considered the gold standard of medical treatment for GERD due to their effectiveness in treating both nonerosive and erosive GERD. Some PPIs and H2RAs are available as over-the-counter medications, and some require a prescription. Prokinetic medications help promote esophageal peristalsis. Although some clients may benefit from prokinetic medications like metoclopramide, their use is controversial due to the side effects that can occur with long-term use.[19]

For more information about medications used to treat GERD, visit the “Antiulcer Medications” and “Antiemetics” sections in the “Gastrointestinal System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Surgical Management

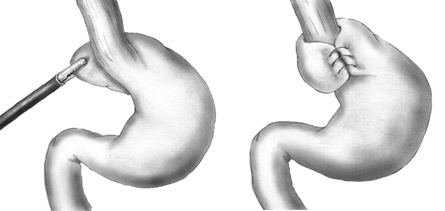

If GERD does not respond to typical medication therapy or unacceptable side effects occur, surgery may be an option, especially if a large hiatal hernia is present. The most common surgical procedure for GERD is a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. In this procedure, the upper portion of the stomach is wrapped around the lower portion of the esophagus to prevent the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. See Figure 11.31[20] for an illustration of the laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication procedure. Common postoperative complications are abdominal bloating, difficulty swallowing, and increased burping, although most clients experience an improvement in GERD symptoms.[21],[22]

View a supplementary YouTube video[23] on surgery used to treat GERD: Anti-reflux surgery, fundoplication-Mayo Clinic.

Nursing Interventions

When providing nursing care to clients with GERD, the following nursing interventions can be categorized as nursing assessments, nursing actions, and client teaching[24],[25]:

Nursing Assessments

- Assess the client’s nutritional status because it can be impacted by GERD symptoms and avoidance of triggering foods.

- Perform a comprehensive assessment of chest pain symptoms because the pain caused by GERD can be similar to symptoms of a myocardial infarction, especially in female clients.

- Assess for signs and symptoms of aspiration caused by GERD (i.e., wheezing, new onset asthma, chronic cough, and hoarseness).

- Assess complete blood count results for signs of anemia as a result of erosive GERD. Cardiac labs may be ordered by the health care provider to rule out a myocardial infarction when atypical chest pain is present.

Nursing Actions

- Obesity can increase GERD symptoms, so weight loss is encouraged. A typical goal is to lose one pound per week until a desired weight is achieved. The client can also be referred to a dietician to help develop a healthy eating plan. Gastric bypass surgery is an option for severely obese clients with GERD.

- Small, frequent meals are encouraged instead of large meals because they are easier to digest and may reduce GERD symptoms.

- Administer prescribed GERD medications.

- Elevate the head of bed of clients in inpatient care to prevent GERD symptoms and decrease the risk of aspiration.

Client Teaching

The following topics are typically included when providing health teaching about GERD:

- Understand the GERD disease process and medications prescribed to manage the condition.

- Sit upright during and after meals.

- Avoid eating three hours before bedtime and elevate the head of the bed using boards or other devices.

- Follow dietary restrictions to help manage symptoms.

- Monitor the stool and vomit for the presence of blood because this can indicate erosive GERD.

- Encourage smoking cessation and avoidance of alcohol because these symptoms can cause increased production of acid, as well as relaxation of the LES, leading to increased GERD symptoms.

- Avoid bending over, coughing, and straining with bowel movements, as these actions can raise intra-abdominal pressure and increase reflux.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with another member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

View a supplementary YouTube video[26] on GERD: Treatments for Heartburn | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) | Gastrointestinal Society.

View a supplementary video[27] on GERD and hiatal hernias: Heartburn and hiatal hernia.

![]() RN Recap: GERD

RN Recap: GERD

View a brief YouTube video overview of GERD[28]:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “GastroEsophageal_Reflux_Disease_(GERD).jpg” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Barrett Esophagus by Khieu & Mukherjee is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Curran, A. (2023, January 18). GERD nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/gerd-nursing-diagnosis/ ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 8 gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-gerd-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “Nissen_fundoplication.png” by Xopusmagnumx at English Wikipedia is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease by Antunes, Allem, & Curtis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Nissen fundoplication. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/4200-nissen-fundoplication ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2010, April 22). Anti-reflux surgery, fundoplication-Mayo Clinic [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X840-6PyO4c ↵

- Curran, A. (2023, January 18). GERD nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/gerd-nursing-diagnosis/ ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 8 gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-gerd-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Gastrointestinal Society. (2017, October 24). Treatments for heartburn | Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) | Gastrointestinal Society [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wzdb4x0rAE4 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Heartburn and hiatal hernia [Video]. Unknown platform. All rights reserved. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heartburn/multimedia/heartburn-gerd/vid-20084644 ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 11 - GERD [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/DEq57OCB0L4?si=6g2xwVjRO-s_zXsP ↵

When administering oxygen therapy, it is important for the nurse to assess the patient before, during, and after the procedure and document the findings.

Subjective Assessment

Prior to initiating oxygen therapy, if conditions warrant, the nurse should briefly obtain a history of respiratory conditions and collect data regarding current symptoms associated with the patient’s feeling of shortness of breath. The duration of this focused assessment should be modified based on the severity of the patient’s dyspnea. See Table 11.4 for focused interview questions related to oxygen therapy. This information is used to customize the oxygen delivery device and flow rate for the patient. For example, supplemental oxygen is typically initiated in nonemergency situations with a nasal cannula at 1-2 liters per minute (L/min), but a patient with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may require a different device such as a Venturi mask.

Table 11.4 Focused Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of Dyspnea

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Please rate your current feeling of shortness of breath from 0-10, "0" being no shortness of breath and "10" being the worst shortness of breath you have ever experienced. | Note: If the shortness of breath is severe, associated with chest pain, or if there are imminent signs of respiratory failure, discontinue the subjective assessment and obtain emergency assistance. |

| Are you experiencing any additional symptoms such as chest pain, cough, or a feeling of swelling in your throat or tongue? | Please describe.

Note: If the patient describes severe symptoms that could indicate imminent blockage of the airway, obtain emergency assistance. When did it start? Is the cough productive of phlegm? If yes, what color and what is the amount? Does the chest pain radiate elsewhere? |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with respiratory conditions such as asthma or COPD? | Please describe. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements to help you breathe? | Please identify what you are taking and the dosage.

If you are using inhalers on an as-needed basis, how often are you using them and has the frequency increased lately? |

| Have you received oxygen therapy previously?

|

Please describe.

Do you use oxygen therapy at home? What is your normal flow rate? Do you use CPAP or BiPAP devices at home? |

| Do you smoke? | Have you considered quitting? |

Objective Assessment

Prior to applying supplemental oxygen, objective data regarding patient status should quickly be obtained such as airway clearance, respiratory rate, pulse oximetry, and lung sounds. Signs of cyanosis in the skin or nail bed assessment should also be noted. Within a few minutes after initiating oxygen administration, the nurse should evaluate for improvement of these indicators, and if no improvement is noted, then additional actions should be taken. At any point, if the nurse feels that the patient’s condition is deteriorating, emergency action should be taken such as calling the rapid response team or 911.

Depending upon the severity of patient condition, serial ABG results may also be monitored to determine effectiveness of oxygenation interventions.

After oxygen therapy is initiated, it is important to closely monitor for skin breakdown at pressure points. For example, nasal cannula tubing often causes skin breakdown in the nares or over the ears, so protective foam dressings may need to be applied.

Life Span Considerations

Children

Different sized oxygen equipment is used for infants and children. Additionally, oxygen tubing may need to be secured to a child’s face with tape to prevent them from pulling it off. For infants, the pulse oximeter probe is usually attached to the palm or foot.

Older Adults

If a patient is oxygen-dependent, ensure that extension tubing is applied so the patient is able to reach the bathroom with the oxygen device in place. However, be aware of the increased risk for falls due to the excess tubing. Keeping the oxygen tubing coiled up at the head of the bed or on the bedside table closest to the bathroom will decrease the patient’s risk of falling. Advise the patient to ask for assistance when getting up to use the restroom.

- Safety Tip: When oxygen is in use, teach the patient about safety considerations with oxygen use. Oxygen itself is not flammable but can cause other materials that burn to ignite more easily and burn more rapidly. See the “Safety with Oxygen Therapy” subsection in "Oxygenation Equipment" for more details.

- After administering oxygen, instruct the patient to inhale through their nose with slow, deep breaths and to breathe out through their mouth.

- If a patient is experiencing worsening dyspnea with decreased oxygen saturation levels compared to their baseline levels, apply oxygen and stay with the patient until their oxygen saturation level increases and they report feeling less short of breath. Providing a physical presence is an important intervention for the associated anxiety that accompanies dyspnea. Consider asking a team member for assistance.

- Based on the patient’s condition, it may be helpful to institute additional interventions to improve oxygenation. See Table 11.2c in the “Basic Concepts of Oxygenation” section for interventions to improve hypoxia.

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

Patient has history of COPD and reported feeling short of breath after getting up to use the bathroom this morning. Respirations 24/minute, pulse oximetry 88% room air. Lung sounds diminished throughout lung fields. Oxygen applied via nasal cannula at 2 lpm and patient encouraged to take slow deep breaths in through their nose and out of their mouth. After five minutes, pulse oximetry 94% 2 liters nasal cannula, respirations 16/minute with patient reporting shortness of breath resolved.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

Patient has history of COPD and heart failure. Reported feeling short of breath after getting up to use the bathroom this morning. Respirations 30/minute, pulse oximetry 88% room air. Crackles to auscultation in lower posterior lobes. Oxygen applied via nasal cannula at 2 lpm and patient encourage to cough and deep breath. After five minutes, no improvement in respiratory rate or SpO2. Dr. Smith notified at 0715. Order for STAT chest X-ray received and furosemide 40 mg IV STAT. Furosemide administered. 30 minutes later, SpO2 92% with O2 at 2 liters per nasal cannula. Respiratory rate 18/minute. Urine output of 500 mL with decreased crackles in the lower posterior lobes. Patient reported feeling less short of breath.