11.7 Gastroenteritis

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the stomach and small intestine. It is classified as an increase in bowel movements that may also be associated with fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Although most cases of gastroenteritis are acute and last fewer than 14 days, it is also possible to have a chronic case lasting over 30 days.[1]

Gastroenteritis can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, but most cases are caused by viruses. Transmission generally occurs via the fecal-oral route, via contaminated food or water, or even airborne routes. Common bacterial causes of gastroenteritis in the United States are Salmonella and Campylobacter. Leading viral causes of gastroenteritis are rotavirus and norovirus. Antibiotics can also cause gastroenteritis as a side effect. This section will focus on viral and bacterial forms of gastroenteritis.[2]

Risk factors for contracting gastroenteritis include traveling to developing countries and consuming improperly prepared food. Viral outbreaks are also common in close quarters, putting clients who attend daycare, live in nursing facilities, or vacation on cruise ships at risk. Clients who are immunocompromised, very young, older adults, or suffer from chronic diseases are at the highest risk for complications related to dehydration.[3]

Pathophysiology

Fluids are normally absorbed in the small intestine, but during gastroenteritis this absorption does not occur normally due to inflammation. Additionally, toxins associated with various bacteria and viruses can cause the lining of the intestine to also excrete fluid. These factors cause frequent, watery diarrhea that is associated with gastroenteritis.[4]

Assessment

Physical Exam

Signs and symptoms of gastroenteritis usually occur suddenly and improve within one to three days. Common signs and symptoms include the following[5]:

- Diarrhea (Diarrhea may or may not contain blood depending on the causative organism.)

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Fever

- Abdominal pain

Dehydration can occur quickly in cases of gastroenteritis, so nurses must assess for signs and symptoms of fluid volume deficit that include the following:

- Dry mucous membranes

- Change in mental status

- Elevated heart rate

- Decreased blood pressure

- Poor skin turgor

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Lab Tests

Lab tests performed to diagnose gastroenteritis are a complete blood count, a metabolic panel, and stool testing[6],[7]:

- A complete blood count (CBC) may show mildly elevated white blood cells with viral causes of gastroenteritis. Bacterial causes of gastroenteritis often cause a significantly elevated white blood cell count. Due to dehydration and the subsequent hemoconcentration, levels of red blood cells, hemoglobin, and hematocrit may appear falsely elevated.

- A complete metabolic panel (CMP) may show an elevated BUN and creatinine if dehydration is severe enough to cause injury to the kidneys. Additionally, vomiting and diarrhea may cause decreased electrolyte levels, particularly potassium.

- Various stool studies may be performed to establish a diagnosis. Specific stool studies can detect certain viral or bacterial causes of gastroenteritis. Stool may also be checked for ova and parasites, as well as the presence of white blood cells.

Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Imaging

In the majority of cases of gastroenteritis, imaging will be normal. However, a CT scan of the abdomen may show inflammation in the bowel that is nonspecific.[8],[9]

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing priorities for those suffering from gastroenteritis include preventing/treating dehydration, promoting good skin care, consuming optimal nutrition, and managing diarrhea.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with gastroenteritis are created based on the specific needs of the client, their signs and symptoms, and the etiology of the disorder. These nursing diagnoses guide the creation of client specific care plans that encompass client outcomes and nursing interventions, as well the evaluation of those outcomes. These individualized care plans then serve as a guide for client treatment.

Possible nursing diagnoses for those with gastroenteritis are as follows[10]:

- Fluid Volume Deficit

- Impaired Skin Integrity

- Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements

- Diarrhea

- Risk for Electrolyte Imbalance

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification encompasses the creation of short- and long-term goals for the client. These goals are used to create expected outcome statements that are based on the specific needs of the client. Expected outcomes should be specific, measurable, and realistic. These outcomes should be achievable within a set time frame based on the application of appropriate nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes for some of the above nursing diagnoses are listed below:

- The client will exhibit blood pressure and heart rate within normal limits for age, moist mucous membranes, and urine output appropriate for age during the course of the illness.

- The client will exhibit skin in the peri-area that is an appropriate color for race and free from skin breakdown during the course of the illness.

- The client will tolerate a bland diet without nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea within 24 hours.

- The client will exhibit a formed stool that occurs at the client’s normal frequency within one week.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Specific medical interventions depend on the causative factor of gastroenteritis. Generally, viral gastroenteritis is treated with supportive care such as the following[11],[12]:

- Prevent/treat dehydration by providing adequate fluids. IV fluids may be administered for clients who are dehydrated or cannot tolerate fluids by mouth due to nausea/vomiting.

- Supplement electrolytes as needed via oral or IV routes, depending on the status of the client.

- Antiemetic medications may be prescribed to control nausea and vomiting. Commonly prescribed medications are ondansetron or metoclopramide. Clients are encouraged to adhere to a bland diet while symptomatic.

- Although antidiarrheal medications such as loperamide or diphenoxylate/atropine exist, their use in gastroenteritis (both viral and bacterial) is controversial.

For clients diagnosed with bacterial gastroenteritis, medical interventions include supportive care described above, as well as possible antibiotics to treat the infection. Generally, antibiotics are prescribed for clients with severe cases of bacterial gastroenteritis (defined as over six stools per day, febrile, and hospitalized), have blood in their stool, have Clostridium difficile (C. diff), are over 70 years in age, are immunocompromised, or have other comorbidities.[13]

Generally, clients with gastroenteritis can be managed at home, but hospital admission may be required for clients who are severely dehydrated, cannot stop vomiting, have significant electrolyte abnormalities or abdominal pain, or those who are pregnant.[14],[15]

Nursing Interventions

When providing nursing care for clients with gastroenteritis, the following nursing interventions can be divided into nursing assessments, nursing actions, and client teaching[16][17],[18]:

Nursing Assessments

- Assess client vital signs. Vital signs may be altered due to fever or dehydration.

- Assess intake and output.

- Assess for signs of dehydration (dry mucous membranes, decreased urine output, sunken fontanels in infants, poor skin turgor, elevated heart rate, or decreased blood pressure).

- For clients with diarrhea, assess skin in perineal area for breakdown.

Nursing Actions

- Administer IV fluids as prescribed. Encourage oral intake if appropriate.

- Administer antiemetics as prescribed.

- Administer electrolyte supplements as prescribed.

- Ensure a hospitalized client is placed in a room according to transmission-based precautions (typically contact precautions). In cases of norovirus, contact and droplet precautions are also required.

Client Teaching

- Teach proper handwashing before eating, before preparing food, and after using the restroom to prevent the spread of gastroenteritis.

- Teach about consuming a bland diet while symptomatic, such as bananas, rice, and toast. Dairy and spicy/heavily seasoned food should be avoided until symptoms have resolved.

- Teach guidelines for using over-the-counter medications.

- Teach parents with children about the rotavirus vaccine and teach proper food preparation and storage methods as prevention interventions.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with another member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Gastroenteritis

RN Recap: Gastroenteritis

View a brief YouTube video overview of gastroenteritis[19]:

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Bacterial Gastroenteritis by Sattar & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Bacterial Gastroenteritis by Sattar & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis (Nursing) by Stuempfig, Seroy, & Labat-Butler is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Bacterial Gastroenteritis by Sattar & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Bacterial Gastroenteritis by Sattar & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Bacterial Gastroenteritis by Sattar & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis by Stuempfig & Seroy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Bacterial Gastroenteritis by Sattar & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Viral Gastroenteritis (Nursing) by Stuempfig, Seroy, & Labat-Butler is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 11 - Gastroenteritis [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/IbJKcxLRpFQ?si=UhaAb7yjK5XZXyNH ↵

When assessing a patient’s oxygenation status, it is important for the nurse to have an understanding of the underlying structures of the respiratory system to best understand their assessment findings.

Visit the “Respiratory Assessment" chapter for more information about the structures of the respiratory system.

For more information about common respiratory conditions and medications used to treat them, visit the "Respiratory" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

View supplementary YouTube videos on oxygenation basics:

TED-Ed video on Oxygen's Journey[1]

Breathing Mechanics[2]

Gas Exchange[3]

Carbon Dioxide Transport[4]

Assessing Oxygenation Status

A patient’s oxygenation status is routinely assessed using pulse oximetry, referred to as SpO2. SpO2 is an estimated oxygenation level based on the saturation of hemoglobin measured by a pulse oximeter. Because the majority of oxygen carried in the blood is attached to hemoglobin within the red blood cell, SpO2 estimates how much hemoglobin is “saturated” with oxygen. The target range of SpO2 for an adult is 95-100%.[5] For patients with chronic respiratory conditions, such as COPD, the target range for SpO2 is often lower at 88% to 92%.

Although SpO2 is an efficient, noninvasive method to assess a patient’s oxygenation status, it is an estimate and not always accurate. For example, decreased peripheral circulation can also cause a misleading low SpO2 level due to lack of blood flow to the area in which the pulse oximeter is attached. Another example of an inaccurate reading is if the patient is severely anemic with a decreased hemoglobin level. They may have a normal SpO2 reading because their existing hemoglobin is saturated with oxygen, even though the available oxygen is not enough to meet the metabolic demands of their body.

A more specific measurement of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is obtained through an arterial blood gas (ABG). ABG results are often obtained for patients who have deteriorating or unstable respiratory status requiring urgent and emergency treatment. An ABG is a blood sample that is typically drawn from the radial artery by a respiratory therapist, emergency or critical care nurse, or health care provider. ABG results evaluate oxygen, carbon dioxide, pH, and bicarbonate levels. The partial pressure of oxygen in the blood is referred to as PaO2. The normal PaO2 level of a healthy adult is 80 to 100 mmHg. The PaO2 reading is more accurate than a SpO2 reading because it is not affected by hemoglobin levels. The PaCO2 level is the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the blood. The normal PaCO2 level of a healthy adult is 35-45 mmHg. The normal range of pH level for arterial blood is 7.35-7.45, and the normal range for the bicarbonate (HCO3) level is 22-26. The SaO2 level is also obtained, which is the calculated arterial oxygen saturation level. See Table 11.2a for a summary of normal ranges of ABG values.[6]

Table 11.2a Normal Ranges of ABG Values

| Value | Description | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Acid-base balance of blood | 7.35-7.45 |

| PaO2 | Partial pressure of oxygen | 80-100 mmHg |

| PaCO2 | Partial pressure of carbon dioxide | 35-45 mmHg |

| HCO3 | Bicarbonate level | 22-26 mEq/L |

| SaO2 | Calculated oxygen saturation | 95-100% |

Read more information about interpreting ABG results in the "Acid Base" section of the "Fluids and Electrolytes" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia is defined as a reduced level of tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia has many causes, ranging from respiratory and cardiac conditions to anemia. Hypoxemia is a specific type of hypoxia that is defined as decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2), measured by an arterial blood gas (ABG).

Early signs of hypoxia are anxiety, confusion, and restlessness. As hypoxia worsens, the patient’s level of consciousness and vital signs will worsen, with increased respiratory rate and heart rate and decreased pulse oximetry readings. Late signs of hypoxia include bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes called cyanosis. Cyanosis is most easily seen around the lips and in the oral mucosa. A sign of chronic hypoxia is clubbing, a gradual enlargement of the fingertips (see Figure 11.1[7]). See Table 11.2b for symptoms and signs of hypoxia.[8]

Hypercapnia is an elevated level of carbon dioxide in the blood. This level is measured by the PaCO2 level in an ABG test and is indicated when the PaCO2 level is higher than 45. Hypercapnia is typically caused by hypoventilation or areas of the alveoli that are ventilated but not perfused. In a state of hypercapnia or hypoventilation, there is an accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood. The increased carbon dioxide causes the pH of the blood to drop, leading to a state of respiratory acidosis.

You can read more about respiratory acidosis in the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals book.

Patients with hypercapnia can present with tachycardia, dyspnea, flushed skin, confusion, headaches, and dizziness. If the hypercapnia develops gradually over time, such as in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), symptoms may be mild or may not be present at all. Hypercapnia is managed by addressing its underlying cause. A noninvasive positive pressure device such as a BiPAP may provide support to patients who are having trouble breathing normally, but if this is not sufficient, intubation may be required.[9]

Table 11.2b Symptoms and Signs of Hypoxia

| Signs & Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Restlessness | Patient may become increasingly fidgety, move about the bed, demonstrate signs of anxiety and agitation. Restlessness is an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachycardia | An elevated heart rate (above 100 beats per minute in adults) can be an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachypnea | An increased respiration rate (above 20 breaths per minute in adults) is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Shortness of breath (Dyspnea) | Shortness of breath is a subjective symptom of not getting enough air. Depending on severity, dyspnea causes increased levels of anxiety. |

| Oxygen saturation level (SpO2) | Oxygen saturation levels should be above 94% for an adult without an underlying respiratory condition. |

| Use of accessory muscles | Use of neck or intercostal muscles when breathing is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Noisy breathing | Audible noises with breathing are an indication of respiratory conditions. Assess lung sounds with a stethoscope for adventitious sounds such as wheezing, rales, or crackles. Secretions can plug the airway, thereby decreasing the amount of oxygen available for gas exchange in the lungs. |

| Flaring of nostrils or pursed-lip breathing | Flaring is a sign of hypoxia, especially in infants. Pursed-lip breathing is a technique often used in patients with COPD. This breathing technique increases the amount of carbon dioxide exhaled so that more oxygen can be inhaled. |

| Position of patient | Patients in respiratory distress may sit up or lean over by resting arms on their legs to enhance lung expansion. Patients who are hypoxic may not be able to lie flat in bed. |

| Ability of patient to speak in full sentences | Patients in respiratory distress may be unable to speak in full sentences or may need to catch their breath between sentences. |

| Skin color (Cyanosis) | Changes in skin color to bluish or gray are a late sign of hypoxia. |

| Confusion or loss of consciousness (LOC) | This is a worsening sign of hypoxia. |

| Clubbing | Clubbing, a gradual enlargement of the fingertips, is a sign of chronic hypoxia. |

Treating Hypoxia

Acute hypoxia is a medical emergency and should be treated promptly with oxygen therapy. Failure to initiate oxygen therapy when needed can result in serious harm or death of the patient. Although oxygen is considered a medication that requires a prescription, oxygen therapy may be initiated without a physician’s order in emergency situations as part of the nurse’s response to the “ABCs,” a common abbreviation for airway, breathing, and circulation. Most agencies have a protocol in place that allows nurses to apply oxygen in emergency situations. After applying oxygen as needed, the nurse then contacts the provider, respiratory therapist, or rapid response team, depending on the severity of hypoxia. Devices such high-flow oxymasks, CPAP, BiPAP, or mechanical ventilation may be initiated by the respiratory therapist or provider to deliver higher amounts of inspired oxygen. Various types of oxygenation devices are further explained in the “Oxygenation Equipment” section.

Prescription orders for oxygen therapy will include two measurements of oxygen to be delivered - the oxygen flow rate and the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2). The oxygen flow rate is the number dialed up on the oxygen flow meter between 1 L/minute and 15 L/minute. Fio2 is the concentration of oxygen the patient inhales. Room air contains 21% oxygen concentration, so the FiO2 for supplementary oxygen therapy will range from 21% to 100% concentration.

In addition to administering oxygen therapy, there are several other interventions the nurse should consider implementing to a hypoxic patient. Additional interventions used to treat hypoxia in conjunction with oxygen therapy are outlined in Table 11.2c.[10]

Table 11.2c Interventions to Manage Hypoxia

| Interventions | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Raise the Head of the Bed | Raising the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position promotes effective chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, maximizes inhalation, and decreases the work of breathing. Patients with COPD who are short of breath may gain relief by sitting upright or leaning over a bedside table while in bed. |

| Encourage Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques | Enhanced breathing and coughing techniques such as using pursed-lip breathing, coughing and deep breathing, huffing technique, incentive spirometry, and flutter valves may assist patients to clear their airway while maintaining their oxygen levels. See the following “Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques” subsection for additional information regarding these techniques. |

| Manage Oxygen Therapy and Equipment | If the patient is already on supplemental oxygen, ensure the equipment is turned on, set at the required flow rate, correctly positioned on the patient, and properly connected to an oxygen supply source. If a portable tank is being used, check the oxygen level in the tank. Ensure the connecting oxygen tubing is not kinked, which could obstruct the flow of oxygen. Feel for the flow of oxygen from the exit ports on the oxygen equipment. In hospitals where medical air and oxygen are used, ensure the patient is connected to the oxygen flow port. Hospitals in America follow the national standard that oxygen flow ports are green and air outlets are yellow. |

| Assess the Need for Respiratory Medications | Pharmacological management is essential for patients with respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, or severe allergic response. Bronchodilators effectively relax smooth muscles and open airways. Glucocorticoids relieve inflammation and also assist in opening air passages. Mucolytics decrease the thickness of pulmonary secretions so that they can be expectorated more easily. |

| Provide Oral Suctioning if Needed | Some patients may have a weakened cough that inhibits their ability to clear secretions from the mouth and throat. Patients with muscle disorders or those who have experienced a cerebral vascular accident (CVA) are at risk for aspiration pneumonia, which is caused by the accidental inhalation of material from the mouth or stomach. Provide oral suction if the patient is unable to clear secretions from the mouth and pharynx. See the chapter on “Tracheostomy Care and Suctioning” for additional details on suctioning. |

| Provide Pain Relief If Needed | Provide adequate pain relief if the patient is reporting pain. Pain increases anxiety and may inhibit the patient’s ability to take in full breaths. |

| Consider the Side Effects of Pain Medications | A common side effect of pain medication is sedation and respiratory depression.

For more information about interventions to manage respiratory depression, see the “Oxygenation” chapter in the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook. |

| Consider Other Devices to Enhance Clearance of Secretions | Chest physiotherapy and specialized devices assist with secretion clearance, such as handheld flutter valves or vests that inflate and vibrate the chest wall. Consider requesting a consultation with a respiratory therapist based on the patient’s situation. |

| Plan Frequent Rest Periods Between Activities | Patients experiencing hypoxia often feel short of breath and fatigue easily. Allow the patient to rest frequently, and space out interventions to decrease oxygen demand in patients whose reserves are likely limited. |

| Consider Other Potential Causes of Dyspnea | If a patient’s level of dyspnea is worsening, assess for other underlying causes in addition to the primary diagnosis. Are there other respiratory, cardiovascular, or hematological conditions such as anemia occurring? Start by reviewing the patient’s most recent hemoglobin and hematocrit lab results. Completing a thorough assessment may reveal abnormalities in these systems to report to the health care provider. |

| Consider Obstructive Sleep Apnea | Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are often not previously diagnosed prior to hospitalization. The nurse may notice the patient snores, has pauses in breathing while snoring, or awakens not feeling rested. These signs may indicate the patient is unable to maintain an open airway while sleeping, resulting in periods of apnea and hypoxia. If these apneic periods are noticed but have not been previously documented, the nurse should report these findings to the health care provider for further testing and follow-up. Testing consists of using continuous pulse oximetry while the patient is sleeping to determine if the patient is hypoxic during these episodes and if a CPAP device should be prescribed. See the box below for additional information regarding OSA. |

| Anxiety | Anxiety often accompanies the feeling of dyspnea and can worsen it. Anxiety in patients with COPD is chronically undertreated. It is important for the nurse to address the feelings of anxiety and dyspnea. Anxiety can be relieved by teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques, encouraging relaxation techniques, or administering antianxiety medications. |

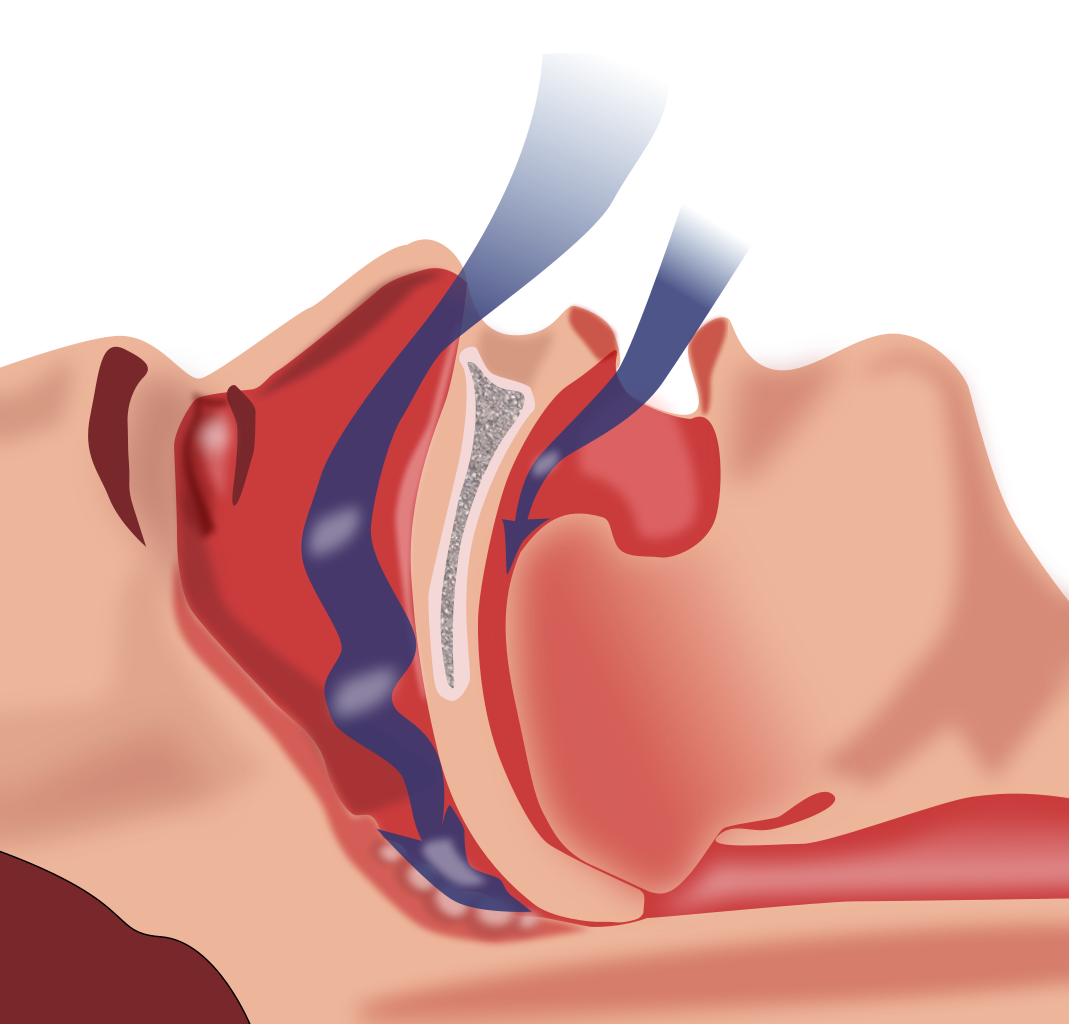

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is the most common type of sleep apnea. See Figure 11.2[11] for an illustration of OSA. As soft tissue falls to the back of the throat, it impedes the passage of air (blue arrows) through the trachea and is characterized by repeated episodes of complete or partial obstructions of the upper airway during sleep. The episodes of breathing cessations are called “apneas,” meaning “without breath.” Despite the effort to breathe, apneas are associated with a reduction in blood oxygen saturation due to the obstruction of the airway. Treatment for OSA often includes the use of a CPAP device.

Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques

In addition to oxygen therapy and the interventions listed in Table 11.2c to implement for a patient experiencing dyspnea and hypoxia, there are several techniques a nurse can teach a patient to use to enhance their breathing and coughing. These techniques include pursed-lip breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing and deep breathing, and the huffing technique.

Pursed-Lip Breathing

Pursed-lip breathing is a technique that allows people to control their oxygenation and ventilation. The technique requires a person to inspire through the nose and exhale through the mouth at a slow controlled flow. See Figure 11.3[12] for an illustration of pursed-lip breathing. This type of exhalation gives the person a puckered or pursed appearance. By prolonging the expiratory phase of respiration, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled, thus reducing air trapping that occurs in some conditions such as COPD. Pursed-lip breathing often relieves the feeling of shortness of breath, decreases the work of breathing, and improves gas exchange. People also regain a sense of control over their breathing while simultaneously increasing their relaxation.[13]

View a supplementary YouTube video on pursed-lip breathing from the COPD Foundation called Breathing Techniques.[14]

Incentive Spirometry

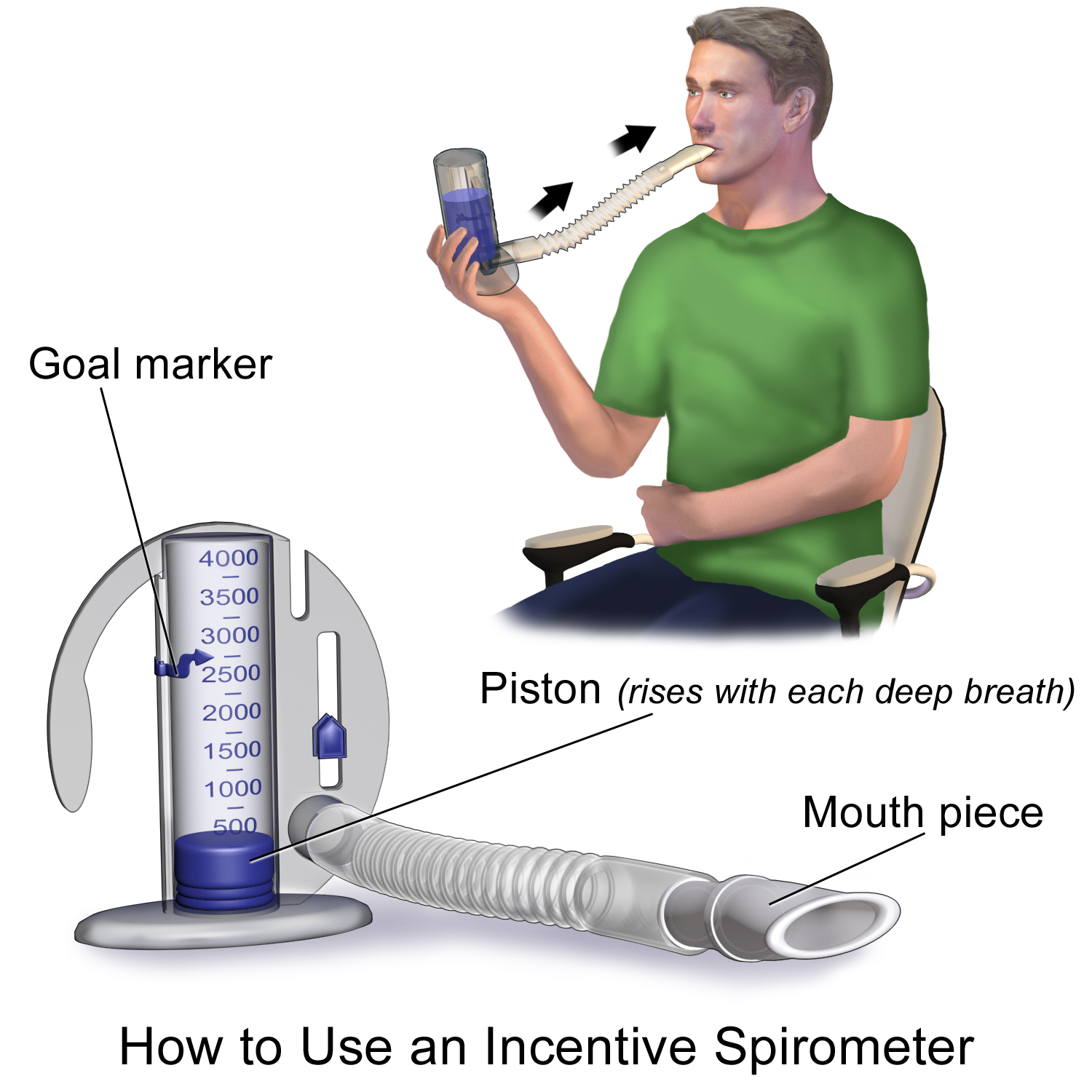

An incentive spirometer is a medical device often prescribed after surgery to prevent and treat atelectasis. Atelectasis occurs when alveoli become deflated or filled with fluid and can lead to pneumonia. See Figure 11.4[15] for an image of a patient using an incentive spirometer. While sitting upright, the patient should breathe in slowly and deeply through the tubing with the goal of raising the piston to a specified level. The patient should attempt to hold their breath for 5 seconds, or as long as tolerated, and then rest for a few seconds. This technique should be repeated by the patient 10 times every hour while awake.[16] The nurse may delegate this intervention to unlicensed assistive personnel, but the frequency in which it is completed and the volume achieved should be documented and monitored by the nurse.

Coughing and Deep Breathing

Teaching the coughing and deep breathing technique is similar to incentive spirometry but no device is required. The patient is encouraged to take deep, slow breaths and then exhale slowly. After each set of breaths, the patient should cough. This technique is repeated 3 to 5 times every hour.

Huffing Technique

The huffing technique is helpful for patients who have difficulty coughing. Teach the patient to inhale with a medium-sized breath and then make a sound like “Ha” to push the air out quickly with the mouth slightly open.

Vibratory PEP Therapy

Vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy uses handheld devices such as “flutter valves” or “Acapella” devices for patients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. These devices (see Figure 11.5[17]) require a prescription and are used in collaboration with a respiratory therapist or advanced health care provider. To use vibratory PEP therapy, the patient should sit up, take a deep breath, and blow into the device. A flutter valve within the device creates vibrations that help break up the mucus so the patient can cough it up and spit it out. Additionally, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled.