11.3 General Assessment of the Gastrointestinal System

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

When evaluating a client with a potential gastrointestinal disorder, the nurse must pay special attention to their particular risk factors, as well as the influence of their cultural beliefs and socioeconomic factors. All these factors may affect their overall gastrointestinal health, as well as their response to treatment.

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors that, when present, can contribute to the development of gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, including the following[1],[2],[3],[4],[5]:

- Diet can play a large role in the development of gastrointestinal disorders. For instance, a low-fiber diet puts the client at risk for constipation, as well as diverticulosis. The use of alcohol can contribute to gastroesophageal reflux disease and can lead to impaired nutrition absorption and increased incidence of diarrhea, as well as the risk of esophageal cancer. Diets high in fat have also been linked to inflammatory bowel disease, as well as the immune health of the gastrointestinal system.

- Inactivity puts the client at risk for constipation due to reduced GI motility. Inactivity also promotes obesity, which is a risk factor for a variety of gastrointestinal disorders.

- The use of certain medications such as iron supplements and opioids can contribute to constipation.

- A family history of GI disorders can put the client at elevated risk. For instance, colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease tend to run in families.

- Age is also a significant risk factor. The elderly undergo a number of physiologic changes that predispose them to gastrointestinal issues. For instance, elderly clients tend to experience alterations in taste, which may put them at risk for malnutrition. Elderly clients have a reduction in LES pressure, predisposing them to gastroesophageal disease. Additionally, they also have a reduction in blood flow to the stomach and decreased protective systems, putting them at greater risk for peptic ulcer disease.

- Stress resulting from acute illnesses and burns can contribute to the development of peptic ulcer disease.

Cultural Factors

A variety of cultural factors can also influence health and illness as it relates to the gastrointestinal tract. A client’s ethnic heritage can affect how a gastrointestinal disorder presents. For instance, African Americans with inflammatory bowel disease tend to have more complex GI disorders and suffer from more complications when compared to other ethnicities. Food also plays a significant role in cultural traditions and can, therefore, affect the gastrointestinal system. For example, clients who are vegan avoid the ingestion of animal products. Therefore, nurses must take cultural beliefs into account when counseling the client on dietary intake as it relates to a particular disorder.[6]

Client terminology and language can also be important when assessing the client’s gastrointestinal system. Bloating is a common symptom of many GI disorders; however, this term does not translate well in many languages. Therefore, clients whose primary language is other than English may use the word “distention” instead. Clients may also treat their gastrointestinal ailments with complementary or alternative medications, so nurses must assess for the use of these treatments, in addition to mainstream medications.[7]

Cultural beliefs regarding family structure can also impact gastrointestinal health. Some clients have a wide network of extended family members they can rely on as a support system, whereas other clients have a smaller nuclear family with less social support available. Studies have shown that clients who have more family support tend to rate their symptoms as less distressing than those who do not have the same level of family support.[8]

A client’s culture can have a significant impact on their health care outcomes. As health care professionals, we must demonstrate cultural humility and ask about and respect client’s cultural values, perspectives, and beliefs.

Socioeconomic Factors

Socioeconomic factors refer to things like education levels, employment, access to health care, and access to healthy food. All these factors can directly impact the health of individuals and must be taken into account when assessing the gastrointestinal system. For example, individuals with less education may have difficulty obtaining a well-paying job with health insurance. They may be unable to afford medications required to manage chronic gastrointestinal conditions. Limited access to health care can also prevent them from obtaining a recommended health care screening like a colonoscopy, causing a delay in diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Limited access to dental care can cause chronic issues with dental pain or difficulty chewing that impact oral intake and can result in poor nutrition.[9]

Food insecurity, a lack of food due to financial or other resources, is a risk factor for developing many chronic diseases and can make it difficult for clients to follow recommended dietary plans due to a lack of access to various food options. Nurses assess the impact of potential socioeconomic factors as a holistic approach to health care and address these factors in the nursing care plan to help the client achieve optimal health care outcomes.[10]

Assessment

Health History

A focused gastrointestinal subjective assessment collects data about the signs and symptoms of GI diseases, including any digestive or nutritional issues, relevant medical or family history of GI diseases, and any current treatment for related issues. Table 11.3 outlines interview questions used to explore medical and surgical history, symptoms related to the gastrointestinal system, and associated medications. Information gained from the interview process is used to tailor the subsequent physical assessment and create a plan for client care and education.[11]

Table 11.3. Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of GI System[12]

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a gastrointestinal (GI) condition? | Please describe the conditions and treatments. |

| Have you ever had abdominal surgery? | Please describe the surgery and if you experienced any complications. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements? | Please describe. |

| Do you have any abdominal pain? | Are there any associated symptoms with the pain such as fever, nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel pattern?

Are you having bloody stools (hematochezia); dark, tarry stools (melena); abdominal distention; or vomiting of blood (hematemesis)? When did the pain start to occur? (Onset) Where is the pain? (Location) When it occurs, how long does the pain last? (Duration) Can you describe what the pain feels like? (Characteristics) What brings on the pain? (Aggravating factors) What relieves the pain? (Alleviating factors) Does the pain radiate anywhere? (Radiation) What have you used to treat the pain? (Treatment) What effect has the pain had on you? (Effects) How severe is the pain from 0-10 when it occurs? (Severity) |

| Have you had any issues with nausea, vomiting, food intolerance, heartburn, ulcers, change in appetite, or weight? | Please describe.

What treatment did you use for these symptoms? What is your typical diet in a 24-hour period? |

| Do you have any difficulty swallowing food or liquids (dysphagia)? | Please describe.

Have you ever been diagnosed with a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA)? |

| When was your last bowel movement? | Describe your usual bowel pattern.

Have there been any changes in pattern or consistency of your stool? Are you passing any gas? |

| Have you had any issues with constipation or diarrhea? | Please describe.

How long have you had these issues? What treatment did you use for these symptoms? If constipation:

If diarrhea:

|

Pain is the most common complaint related to abdominal problems and can be attributed to multiple underlying etiologies. Because of the potential variability of contributing factors, a thorough assessment of this common chief complaint should occur. Additional questions include asking if the client has bloody stools (hematochezia); dark, tarry stools (melena); bloating (abdominal distention); or vomiting of blood (hematemesis).[13]

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation are common issues experienced by hospitalized clients due to side effects of medications or medical procedures. Nausea is the unpleasant sensation of having the urge to vomit, and vomiting (emesis) is the forceful oral expulsion of gastric contents.[14] There are many potential causes of nausea and vomiting, such as the following[15]:

- Morning sickness during pregnancy

- Gastroenteritis and other infections

- Migraines

- Motion sickness

- Food poisoning

- Side effects of medicines, including those for cancer chemotherapy

- GERD and ulcers

- Intestinal obstruction

- Poisoning or exposure to a toxic substance

- Diseases of other organs (cardiac, renal, or liver)

Nausea and vomiting are common and are usually not serious. However, the health care provider should be contacted immediately if the following conditions occur[16]:

- Vomiting for longer than 24 hours

- Blood in the vomit (hematemesis)

- Severe abdominal pain

- Severe headache and stiff neck

- Signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth, infrequent urination, or dark urine

If a client is experiencing vomiting or diarrhea, nurses should assess for signs of dehydration or electrolyte imbalances. Dehydration can be indicated by dry skin, dry mucous membranes, or sunken eyes. These symptoms may require prompt notification of the health care provider for further treatment.[17]

Read additional information about fluid and electrolyte imbalances in the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Additional specialized assessments of GI system function can include examination of the oropharynx and esophagus. For example, clients who have experienced a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), also called a stroke, may experience difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). The nurse is often the first to notice these difficulties in clients who are swallowing pills, liquid, or food and can advocate for treatment to prevent complications, such as aspiration pneumonia.[18]

Physical Assessment

In preparation for the physical assessment, the nurse should create an environment in which the client will be comfortable. Encourage the client to empty their bladder prior to the assessment. Warm the room and stethoscope to decrease tensing during assessment.[19]

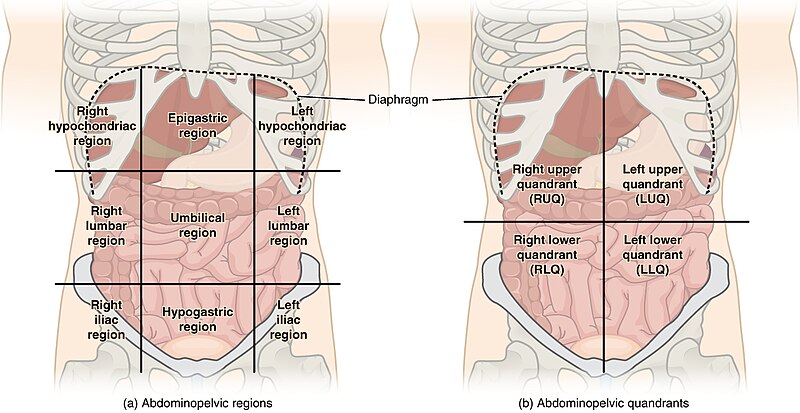

Physical examination of the abdomen includes inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion. Note that the order of physical assessment differs for the abdominal system compared to other systems. Palpation should occur after the auscultation of bowel sounds so that accurate, undisturbed bowel sounds can be assessed. The abdomen is divided into several abdominopelvic quadrants, as illustrated in Figure 11.18.[20] When assessing the abdomen, the nurse considers the organs located in the quadrant being examined.[21]

Inspection

The abdomen is inspected by positioning the client supine on an examining table or bed. The head and knees should be supported with small pillows or folded sheets for comfort and to relax the abdominal wall musculature. The client’s arms should be at their side and not folded behind their head because this position tenses the abdominal wall. Visually examine the abdomen for overall shape, masses, skin abnormalities, and any abnormal movements[22]:

- Observe the general contour and symmetry of the entire abdominal wall. The contour of the abdomen is often described as flat, rounded, scaphoid (sunken), or protuberant (convex or bulging).

- Assess for distention. Generalized distention of the abdomen can be caused by obesity, bowel distention from gas or liquid, or fluid buildup.

- Assess for masses or bulges, which may indicate structural deformities like hernias or be related to disorders in abdominal organs.

- Assess the skin for uniformity of color, integrity, scarring, or striae. Striae are white or silvery elongated marks that occur when the skin stretches, especially during pregnancy or excessive weight gain.

- Note the shape of the umbilicus; it should be inverted and midline.

- Carefully note any scars and correlate these scars with the client’s recollection of previous surgeries or injury.

- Document any abnormal movement or pulsations. Visible intestinal peristalsis can be caused by intestinal obstruction. Pulsations of the aorta may be seen in the epigastric area in clients who are especially thin, but otherwise should not be observed. The presence of a strong pulsating mass could indicate an aortic abdominal aneurysm.[23]

Auscultation

Auscultation follows inspection for accurate assessment of bowel sounds. Use a warmed stethoscope to assess the frequency and characteristics of the client’s bowel sounds, which are also referred to as peristaltic murmurs.[24]

Begin the assessment by gently placing the diaphragm of the stethoscope on the right lower quadrant (RLQ) because bowel sounds are consistently heard in that area. Bowel sounds are generally high-pitched, gurgling sounds that are heard irregularly. The stethoscope is moved to the next quadrant in a clockwise motion around the abdominal wall.[25]

It is not recommended to count abdominal sounds because the activity of normal bowel sounds may cycle with peak-to-peak periods as long as 50 to 60 minutes. The majority of peristaltic murmurs are produced by the stomach, with the remainder from the large intestine and a small contribution from the small intestine. Because the conduction of peristaltic murmur is heard throughout all parts of the abdomen, the source of peristaltic murmur is not always at the site where it is heard.[26]

Hyperactive bowel sounds may indicate bowel obstruction or gastroenteritis. Sometimes a client’s bowel sounds can be heard without a stethoscope (borborygmus), often described as “stomach growling.” This is a common example of hyperactive sounds. Hypoactive bowel sounds may be present with constipation, after abdominal surgery, peritonitis, or paralytic ileus. As the abdomen is auscultated, vascular sounds should not be heard, such as a bruit. Vascular sounds should be reported to the health care provider.[27]

Palpation

Palpation of the abdomen involves using the flat of the hand and fingers (not the fingertips) to detect palpable organs, abnormal masses, or tenderness. If a client is reporting abdominal pain, that area should be palpated last. Light palpation is primarily used by bedside nurses to assess for musculature, abnormal masses, and tenderness. During light palpation, the skin of the abdomen is pressed about one centimeter beginning in the right lower quadrant, and then palpation is moved around the abdomen in a clockwise manner. Deep palpation is a technique used by advanced practice clinicians to assess for enlarged organs.

When palpating the abdomen, note the client’s response, such as guarding, rigidity, or rebound tenderness. Voluntary guarding refers to voluntary contraction of the abdominal wall musculature, usually the result of fear, anxiety, or the touch of cold hands. Involuntary guarding is the reflexive contraction of overlying abdominal muscles as the result of peritoneal inflammation. Rigidity refers to involuntary contraction of the abdominal musculature in response to peritoneal inflammation, a reflex the client cannot control. Rebound tenderness is a sign of peritoneal inflammation. To elicit rebound tenderness, the clinician maintains pressure over an area of tenderness and then withdraws the hand abruptly. If the client winces with pain upon withdrawal of the hand, the test is positive.[28]

Percussion

Percussion is typically performed by advanced practice registered nurses or other health care providers to assess the size of the liver and spleen or to determine if costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness is present, a sign of inflammation of the kidney. Percussion can also indicate the presence of fluid or gas because the sound made during percussion changes based on density. For instance, tympanic sounds indicate the presence of gas or fluid, and dull sounds are heard over dense organs. The change in expected sounds heard during percussion can indicate abnormalities. For instance, the intestines normally elicit tympanic sounds. However, if dullness is heard while percussing the skin over the intestines, it can indicate that increased stool or a mass is present.[29]

Common Laboratory and/or Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory and/or diagnostic testing is often ordered by health care providers to help aid in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal alterations. Although each GI disorder described later in this chapter will specify typical labs and/or diagnostic tests used to diagnose that specific condition, this section will provide a general overview of common gastrointestinal diagnostic tests, including the categories of lab tests, imaging, and endoscopy.

Lab Tests

Common lab tests used to assess the gastrointestinal system are a complete blood count, a comprehensive metabolic panel, stool studies, serum lipase, and inflammatory markers[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37]:

- A complete blood count (CBC) measures the levels of red blood cells, white blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelets in the blood. In cases of GI dysfunction, any of these values could be abnormal. For instance, if a client has peptic ulcer disease and a bleeding ulcer, they may become anemic due to blood loss, reflected by decreased red blood cells, hemoglobin, and hematocrit. Additionally, poor nutritional intake due to a chronic gastrointestinal condition can cause anemia. If a client has an infectious or inflammatory condition, such as appendicitis, white blood cells are typically elevated. Abnormal platelet levels may be seen in clients with inflammatory bowel disease.

- A comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) can be helpful in assessing gastrointestinal conditions by analyzing bilirubin, liver enzymes, albumin, and electrolyte levels. Bilirubin levels and liver enzymes may be altered with pancreatic, gallbladder, or liver disorders. Albumin levels may be decreased in cases of malnutrition due to reduced intake or poor absorption of nutrients. Electrolyte levels, particularly potassium, may be decreased with diarrhea or vomiting.

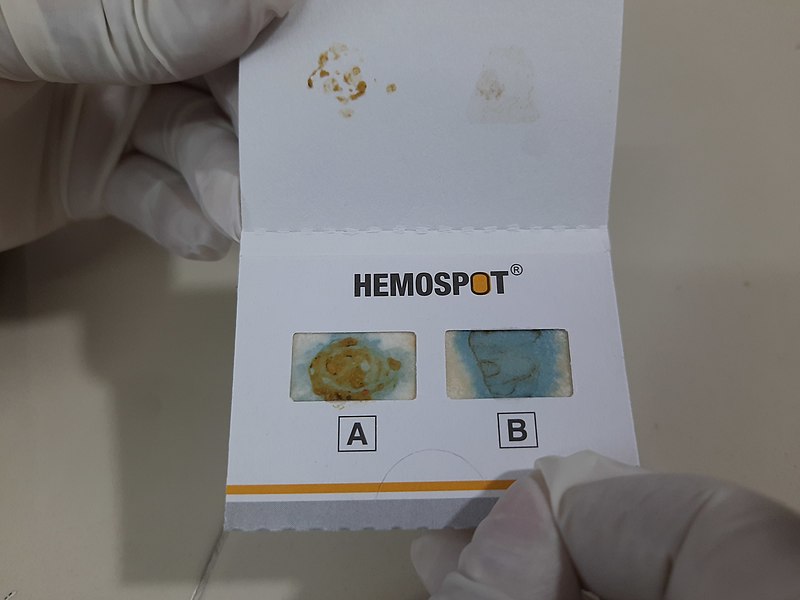

- A variety of stool studies can be used to evaluate for the presence of blood, bacteria, or parasites in the stool. A fecal occult blood test involves placing feces on a testing card and applying a chemical that detects blood not visible to the naked eye. See Figure 11.19[38] for an example of a stool testing card. The stool sample is compared to the control window to determine if blood is present. Stool can also be cultured to check for the presence of specific bacteria. An example of a common stool culture is testing for Clostridium difficile (C. diff). Stool can also be examined under a microscope to look for the presence of ova and/or parasites.

- Serum lipase evaluates levels of lipase, an enzyme that breaks down fats. Elevated levels can be seen with pancreatic disorders.

- Two common inflammatory markers are C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). CRP is released by the liver in response to inflammation. Although CRP is not specific, meaning the test does not show the source of the inflammation, it can be useful in assessing the extent of inflammation in the body. CRP levels are commonly elevated in inflammatory bowel disease. ESR is also a blood test that can measure levels of inflammation in the body. Like CRP, ESR does not show the source of the inflammation, but it may be helpful in monitoring inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.

Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Imaging

Common imaging techniques used to assess the gastrointestinal system are X-rays, CT scans, MRI, MRCP, ultrasound, and barium studies[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44]:

- Abdominal X-ray: An abdominal X-ray is an imaging exam that can be used to look for sources of abdominal pain. They can also be used to assess for blockages, masses, ingestion of foreign objects, or perforations in the intestine. They can be taken in a variety of positions (standing, lying, or side lying) and can provide basic information about abdominal organs.

- Nursing considerations for an abdominal X-ray include ensuring that the client removes anything that may interfere with the exam. The client may be asked to remove their jewelry and put on a gown. The nurse should educate the client to stay still during the X-ray and ensure that any parts of the body that are not being imaged are covered with a lead apron to protect against incidental X-ray exposure. X-rays should not be completed on those who are pregnant as the radiation can cause birth defects.

- Abdominal CT Scan: An abdominal CT scan is an imaging exam that combines the use of X-rays with computer equipment to provide detailed images of the body part that is being scanned. CT scans may be completed with or without the use of contrast, which is given orally or intravenously. When contrast is used, the body part that is being examined can be seen better than when contrast is not used. An abdominal CT scan can be done to look for causes of abdominal pain, bowel obstructions, tumors or masses, infections, or bleeding into the abdomen. A CT scan is often done when enough detail is not seen on a traditional X-ray, or the results are inconclusive.

- Nursing considerations for an abdominal CT scan consist of assessing the client for allergies to contrast media, as well as kidney issues, as contrast dye is known to be nephrotoxic. Those who receive contrast should be encouraged to drink adequate fluids after the exam to help rid the body of the contrast. Nurses must also educate clients who take metformin about the risks associated with combining this medication with contrast media. Clients may be told to temporarily stop this medication. Prior to the exam, clients will be asked to remove their jewelry and change into a gown. Lastly, the client may need to be NPO prior to the CT scan. During the exam, the client will be encouraged to stay still.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is an imaging technique that uses a combination of strong magnets and radio waves to produce in-depth views of the body. Contrast dye may or may not be used with an MRI. An MRI can provide even more detail than a CT scan and does not use radiation. An MRI of the abdomen can be performed to assess for masses, infections, or causes of abdominal pain. It can also assess the lymph nodes and blood vessels of the abdomen.

- Nursing considerations for an MRI include ensuring the client does not have any metal on or implanted within their body prior to entering the exam room due to the use of magnets. Although this list is not inclusive, clients with pacemakers, aneurysm clips, and certain implants may not be able to have an MRI performed. The client will need to change into a hospital gown that does not have any metal on it. Prior to the MRI, for better visualization of the GI tract, the client may need to be NPO. The client should also be encouraged to stay still during the exam. If contrast dye will be used, kidney function and allergies should be assessed first. Lastly, clients with claustrophobia may need to be sedated prior to receiving an MRI as it is an enclosed space. See Figure 11.20[45] for a photo of an MRI machine.

- Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): MRCP uses an MRI with contrast to examine the bile ducts. This can be helpful to assess disorders of the gallbladder, pancreas, or liver. Nursing considerations are similar to that for an MRI.

- Ultrasound: An ultrasound uses sound waves to create images of the body. During an ultrasound, ultrasound gel is placed on the area of the body to be visualized, and a transducer is then placed over it. The transducer emits sound waves that echo off organs to create an image on the computer screen. An abdominal ultrasound can be used to assess for causes of abdominal pain, masses, liver issues, and gallbladder or pancreatic disorders. An ultrasound can be a helpful assessment tool for those individuals who cannot undergo imaging procedures that use radiation, such as pregnant women. They are also helpful as a quick diagnostic tool. Please see Figure 11.21[46] for an image of a client undergoing an abdominal ultrasound.

- Nursing considerations for an abdominal ultrasound include ensuring that the client removes anything that may interfere with the exam. The client may be asked to remove their jewelry and put on a gown. The client may need to be NPO prior to the ultrasound.

![]“330-CFD-DF-SD-04-07421.jpeg” by SRA Stephen Schester, USAF for Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files is licensed in the Public Domain. US Air Force (USAF) Technical Sergeant (TSGT) Thomas Peterson, Ultrasound Technologist, 31st Medical Group (MG), performs an abdominal ultrasound on a patient inside the hospital at Aviano Air Base (AB), Italy.](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/32/2024/09/DF-SD-04-07421-scaled-1.jpeg)

- Barium Studies: Barium studies consist of a barium enema (also known as a lower GI series) and a barium swallow (also known as an upper GI series). The use of barium, which shows up as white on X-rays, allows for better visualization of the GI tract when compared to a regular X-ray. With a barium enema, barium is inserted into the rectum via an enema, and then a series of X-rays are taken. This test allows for visualization of strictures or obstructions in the rectum, large intestine, or the most distal part of the small intestine. With a barium swallow, barium is ingested via the mouth, and then a series of X-rays are taken. With this imaging modality, the esophagus, stomach, and the initial part of the small intestine can be assessed.[47]

- Nursing considerations for a barium enema consist of educating the client on any necessary dietary restrictions prior to the exam. Generally, the client will need to be on a clear liquid diet the day prior, as well as be nothing by mouth after midnight. To clear the intestine of feces to enhance imaging, the client will need to take medications to help clear the bowel prior to the exam. After the exam, the client should be encouraged to drink fluids and eat foods that are high in fiber to help eliminate the remaining barium from the body. Initial stools may appear light in color due to the presence of barium.

- Nursing considerations for a barium swallow also consist of educating the client on any necessary dietary restrictions prior to the exam. An NPO order (nothing by mouth) is often implemented at midnight prior to the exam. Similar to a barium enema, the client will also need to consume adequate fluids and fiber to help the barium be excreted from the body after the exam.

Endoscopy

Common endoscopy procedures used to assess the gastrointestinal system are colonoscopy, EGD, ERCP, and capsule endoscopy[48],[49], [50],[51],[52],[53]:

- Colonoscopy: A colonoscopy refers to the insertion of a scope into the rectum to visualize the entire colon. It is used to visualize abnormal tissue growths, inflamed areas, gastrointestinal bleeding, and ulcers. During a colonoscopy, the provider can also take tissue samples to send for biopsies. The client will receive sedation for the procedure to ensure their comfort.

- Nursing considerations for a colonoscopy consist of educating the client on the need for bowel preparation. To do this effectively, the client must be on a clear liquid diet for 24 or more hours prior to the exam and NPO (nothing by mouth) at midnight. The client must also complete the ordered laxative regimen per provider orders. The nurse will also ensure that the informed consent is completed prior to the procedure. During the colonoscopy, the nurse may assist with client positioning, monitoring of vital signs, and providing client support as needed. After the procedure, the nurse continues to monitor vital signs and for signs of colon perforation and any rectal bleeding.

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): An EGD, also referred to as an “upper GI endoscopy,” is a procedure where a small tube is placed into a client’s mouth and guided through the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. It is completed to further assess client complaints of abdominal pain, difficulty swallowing, gastroesophageal reflux disease, blood in vomit, or gastrointestinal bleeding. An EGD is also commonly done to monitor certain conditions such as Barrett’s esophagus, which is further discussed in the “Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease” section. During an EGD, the provider can also take tissue samples to send for biopsies, dilate strictures, remove foreign bodies, or treat areas that are bleeding. The client will receive sedation for the procedure to ensure their comfort.

- Nursing considerations for an EGD consist of educating the client on the need for dietary modification prior to the exam. The client will need to be on a clear liquid diet and then NPO prior to the exam. The timing of these modifications will differ based on provider. The nurse will also ensure that the informed consent is completed prior to the procedure. During the EGD, the nurse may assist with client positioning, monitoring of vital signs, and providing client support as needed. After the procedure, the nurse continues to monitor vital signs and for signs of complications such as bleeding or bowel perforation. Due to a numbing spray that is used in the procedure, it may take some time for the client’s gag reflex to return. The client should not eat or drink until this occurs.

View a supplementary YouTube video[54] on upper endoscopy: Upper endoscopy (EGD).

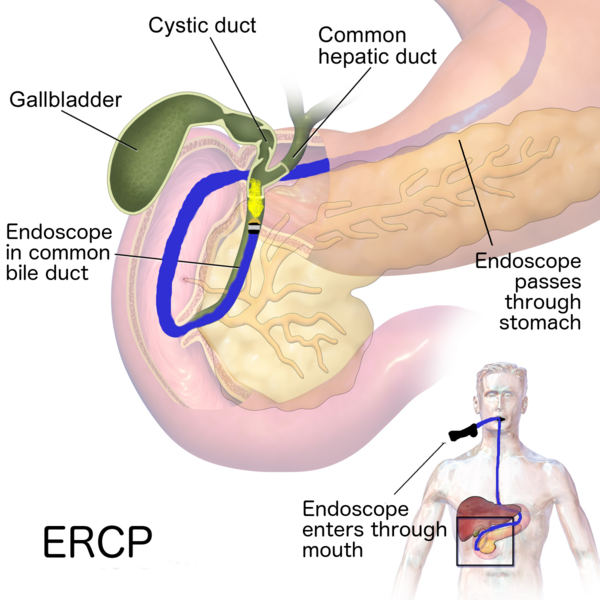

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): An ERCP is the process of inserting a scope into the client’s mouth and then into the esophagus, stomach, and the first part of the small intestine. From there, other tools can then be inserted into the ducts of the biliary/pancreatic system, and tissue samples may be taken. Contrast dye may also be injected to allow for visualization of these ducts. An ERCP may be performed for clients who have stones in the bile duct, pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, or strictures in the biliary system. The client will receive sedation for the procedure to ensure their comfort. See Figure 11.22[55] for an image of an ERCP.

- Nursing considerations for an ERCP consist of educating the client on the need for dietary modification prior to the exam. The client will need to be NPO per provider order. If the client is undergoing an ERCP due to an obstruction in the biliary system, antibiotics may be ordered. During the ERCP, the nurse may assist with client positioning, monitoring of vital signs, and providing client support as needed. After the procedure, the nurse continues to monitor vital signs and for signs of complications such as pancreatitis, cholangitis (infection of the bile ducts), or biliary duct perforation.

- Capsule Endoscopy: Capsule endoscopy is used to assess the small intestine as traditional scopes cannot assess the entire small intestine. With this procedure, the client will swallow a small pill containing a recording device. The pill will travel through the client’s small intestine, collecting images as it passes through. As the pill travels through the digestive system, it sends data to a recorder that is secured externally on the client. This data will then later be reviewed by the provider to look for bleeding, abnormal tissue growth, ulcers, or the presence of inflammatory bowel disease that require additional testing such as a colonoscopy. The pill is then excreted in the stool, normally within 24 hours. Retention of the capsule can occur in those with strictures, obstructions, or fistulas and should not be performed on these clients. No sedation is required with this procedure. See Figure 11.23[56] for an image of a pill with a camera that can be used in a capsule endoscopy.

- Nursing considerations for a capsule endoscopy are similar to that of a colonoscopy, as the client will also need to modify their diet preprocedure and complete colon preparation with the use of laxatives. The nurse may also assist with fitting the recorder onto the client, as well as with ingestion of the pill camera. Lastly, the nurse should educate the client on when meal resumption can occur. Two hours after ingesting the device, the client can start a clear liquid diet. Four hours after ingestion, the client can have a meal.

Life Span Considerations

When assessing infants, children, and older adults, the following life span considerations should be kept in mind[57],[58],[59]:

Infants and Children

- Eating and elimination patterns of infants require special consideration based on the stage of development. Ask parents about feeding habits. Is the baby being breastfed or formula fed? If formula fed, how does the child tolerate the formula?

- To assess for urine output in infants and toddlers, assess the frequency of wet diapers and the daily number of wet diapers. In hospitalized infants and toddlers, the diapers may be weighed for precise measurements of urine output. Urine output can be used to assess hydration status.

- Note that the expected abdominal contour of an infant is called protuberant, which means bulging. The expected abdominal contour of a child is protuberant until about the age of 4.

- Assess the umbilical cord of the neonate; it should dry and fall off on its own within two weeks of life.

- Observe respiratory movement in the abdomen of the infant.

- The exocrine functions of the pancreas are not mature until one year of age.

- Infants have quicker gastric emptying times than compared to adults.

- Children often cannot provide more information than “my stomach hurts”; they may have symptoms of decreased school attendance due to abdominal discomfort.

Older Adults

- Constipation may be more common in older adults due to decreased physical mobility and oral intake, as well as polypharmacy.

- Older adults commonly have reduced saliva, which can lead to dry mouth and alterations in their ability to taste.

- Older adults have decreased LES pressure, making them more prone to gastroesophageal reflux disease.

- Decreased blood flow to the stomach, as well as decreased mucus production, put the older adult at risk for peptic ulcer disease and gastritis.

- Overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine (leading to diarrhea, malabsorption of nutrients, and weight loss) is more common in older adults.

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Gastrointestinal diseases. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/7040-gastrointestinal-diseases ↵

- Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders in Older Age by Dumic, Nordin, Jecmenica, Lalosevic, Milosavljevic, & Milovanovic is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Peptic Ulcer Disease by Malik, Gnanapandithan, & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Alcohol’s Role in Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders by Bode & Bode is in the Public Domain ↵

- Negative Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Intestinal Permeability: A Review by Rohr, Narasimhulu, Rudeski-Rohr, & Parthasarathy is in the Public Domain ↵

- Francisconi, C. F., Sperber, A. D., Fang, X., Fukudo, S., Gerson, M-J., Kang, J-Y., & Schmulson, M. (2016). Multicultural aspects in functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1344-1354. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.013 ↵

- Francisconi, C. F., Sperber, A. D., Fang, X., Fukudo, S., Gerson, M-J., Kang, J-Y., & Schmulson, M. (2016). Multicultural aspects in functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1344-1354. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.013 ↵

- Francisconi, C. F., Sperber, A. D., Fang, X., Fukudo, S., Gerson, M-J., Kang, J-Y., & Schmulson, M. (2016). Multicultural aspects in functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1344-1354. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.013 ↵

- CDC - Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. (2023, September 1). Socioeconomic factors. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/health_equity/socioeconomic.htm ↵

- CDC - Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. (2023, September 1). Socioeconomic factors. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/health_equity/socioeconomic.htm ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Bashashati, M., & McCallum, R. (2014). Neurochemical mechanisms and pharmacologic strategies in managing nausea and vomiting related to cyclic vomiting syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders. European Journal of Pharmacology, 772, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.075 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Pharmacology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Pharmacology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Abdominal_Quadrant_Regions.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- de Boer, N. J., Knaap, S. F. C., & de Zoete, A. (2010). Clinical detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm in a 74-year-old man in chiropractic practice. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 9(1), 38-41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3081239/ ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physical Examination Techniques: A Nurse’s Guide by Lapum, Hughes, St-Amant, Garcia, Verkuyl, Petrie, Dimaranan, Pemasani, & Savicevic is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Digestive diagnostic procedures. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/digestive-diagnostic-procedures ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2023, January 14). Complete blood count (CBC). https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/complete-blood-count/about/pac-20384919 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/22058-comprehensive-metabolic-panel-cmp ↵

- MedlinePlus. (2023, October 30). Ova and parasite test. https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/ova-and-parasite-test/ ↵

- Biochemistry, Lipase by Pirahanchi & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). C-reactive protein (CRP) test. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/23056-c-reactive-protein-crp-test ↵

- MedlinePlus. (2022, November 8). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/erythrocyte-sedimentation-rate-esr/ ↵

- “Fecal_Occult_Blood_Test.jpg” by Ajay Kumar Chaurasiya is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Digestive diagnostic procedures. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/digestive-diagnostic-procedures ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Abdominal x-ray. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/abdominal-x-ray ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan of the abdomen. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/computed-tomography-ct-or-cat-scan-of-the-abdomen ↵

- MedlinePlus. (n.d.). Abdominal MRI scan. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003796.htm ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/24457-magnetic-resonance-cholangiopancreatography-mrcp ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, October 5). Abdominal ultrasound. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/abdominal-ultrasound/about/pac-20392738 ↵

- “23423505123_0228d6749c_o” by unknown author for National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “330-CFD-DF-SD-04-07421.jpeg” by SRA Stephen Schester, USAF for Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine (n.d.). Barium x-rays (upper and lower GI). https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/barium-xrays-upper-and-lower-gi ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Digestive diagnostic procedures. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/digestive-diagnostic-procedures ↵

- Martin, P. (2023, July 2). Colonoscopy. https://nurseslabs.com/colonoscopy/ ↵

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy by Ahlawat, Hoilat, & Ross is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography by Meseeha & Attia is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Capsule Endoscopy by Robertson & Singh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Upper GI endoscopy. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/upper-gi-endoscopy ↵

- Digestive Disease Specialists, Inc. (n.d.). Upper endoscopy (EGD) [Video]. Brightcove. All rights reserved. https://www.okddsi.net/upper-endoscopy ↵

- “640px-ERCP.png” by Drus1a is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “ファイル:GivenimagingKK.JPG” by TMKO is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Skills 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- National Academy of Sciences. (2010). Similarities and dissimilarities in physiology, metabolism, and disease states and responses to therapy in children and adults. In Yaffe, S. (Ed.), Rational Therapeutics for Infants and Children: Workshop Summary (pp. 14-33). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225509/ ↵

- Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders in Older Age by Dumic, Nordin, Jecmenica, Lalosevic, Milosavljevic, & Milovanovic is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

Atrial fibrillation: An irregular heartbeat that is often fast and increases the risk of heart attack or stroke.

Blanching: The whiteness that occurs when pressure is placed on tissue or a nail bed, causing blood to leave the area.

Bruit: A swishing sound when auscultating the carotid arteries. This indicates turbulence in the blood vessel due to atherosclerotic changes.

Capillary refill: The time it takes for color to return after pressure is applied to tissue causing blanching.

Click: Clicking sound heard on auscultation of the precordium; often heard in patients with heart valve abnormalities.

Cyanosis: A bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds. It is an indication of decreased perfusion and oxygenation.

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): A blood clot that forms in a vein deep in the body.

Ductus arteriosus: Shunt that connects the pulmonary artery and aorta in the developing fetus.

Dyspnea: A feeling of shortness of breath.

Edema: Swelling in tissues caused by fluid retention.

Heave or lift: Palpable lifting sensation under the sternum and anterior chest wall to the left of the sternum; it suggests severe right ventricular hypertrophy.

Jugular Vein Distension (JVD): Occurs when the increased pressure of the superior vena cava causes the jugular vein to bulge, making it most visible on the right side of a person's neck.

Murmur: A blowing or whooshing sound heard on auscultation of the precordium that signifies turbulent blood flow in the heart often caused by a valvular defect.

Orthopnea: A feeling of shortness of breath when lying flat.

Pallor: A reduced amount of oxyhemoglobin in the skin or mucous membranes. Skin and mucous membranes present with a pale skin color.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea: An attack of severe shortness of breath that generally occurs at night.

Perfusion: The amount of blood flow to tissue.

Pericardial friction rub: Uncommon heart sound caused by inflammation of the pericardium, with a creaky-scratchy noise generated as the parietal and visceral membranes rub together.

Peripheral edema: Swelling due to an accumulation of fluid in tissues perfused by the peripheral vascular system.

Pitting edema: An accumulation of fluid in tissue and causes an indentation when the area is pressed.

Precordium: The region of the thorax in front of the heart.

Pulmonary embolism: A blood clot that lodges in one of the arteries that go from the heart to the lung.

Sphygmomanometer: An instrument for measuring blood pressure typically consisting of an inflatable rubber cuff.

Syncope: A temporary loss of consciousness usually related to insufficient blood flow to the brain.

Thrill: A vibration felt with palpation of the precordium.

Atrial fibrillation: An irregular heartbeat that is often fast and increases the risk of heart attack or stroke.

Blanching: The whiteness that occurs when pressure is placed on tissue or a nail bed, causing blood to leave the area.

Bruit: A swishing sound when auscultating the carotid arteries. This indicates turbulence in the blood vessel due to atherosclerotic changes.

Capillary refill: The time it takes for color to return after pressure is applied to tissue causing blanching.

Click: Clicking sound heard on auscultation of the precordium; often heard in patients with heart valve abnormalities.

Cyanosis: A bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds. It is an indication of decreased perfusion and oxygenation.

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): A blood clot that forms in a vein deep in the body.

Ductus arteriosus: Shunt that connects the pulmonary artery and aorta in the developing fetus.

Dyspnea: A feeling of shortness of breath.

Edema: Swelling in tissues caused by fluid retention.

Heave or lift: Palpable lifting sensation under the sternum and anterior chest wall to the left of the sternum; it suggests severe right ventricular hypertrophy.

Jugular Vein Distension (JVD): Occurs when the increased pressure of the superior vena cava causes the jugular vein to bulge, making it most visible on the right side of a person's neck.

Murmur: A blowing or whooshing sound heard on auscultation of the precordium that signifies turbulent blood flow in the heart often caused by a valvular defect.

Orthopnea: A feeling of shortness of breath when lying flat.

Pallor: A reduced amount of oxyhemoglobin in the skin or mucous membranes. Skin and mucous membranes present with a pale skin color.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea: An attack of severe shortness of breath that generally occurs at night.

Perfusion: The amount of blood flow to tissue.

Pericardial friction rub: Uncommon heart sound caused by inflammation of the pericardium, with a creaky-scratchy noise generated as the parietal and visceral membranes rub together.

Peripheral edema: Swelling due to an accumulation of fluid in tissues perfused by the peripheral vascular system.

Pitting edema: An accumulation of fluid in tissue and causes an indentation when the area is pressed.

Precordium: The region of the thorax in front of the heart.

Pulmonary embolism: A blood clot that lodges in one of the arteries that go from the heart to the lung.

Sphygmomanometer: An instrument for measuring blood pressure typically consisting of an inflatable rubber cuff.

Syncope: A temporary loss of consciousness usually related to insufficient blood flow to the brain.

Thrill: A vibration felt with palpation of the precordium.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of a “Cardiovascular Assessment."[1]

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: stethoscope and watch with a second hand.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Conduct a focused interview related to cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease.

- Ask relevant focused questions based on patient status. See Tables 9.3a and 9.3b for example questions.

- Inspect:

- Face, lips, and extremities for pallor or cyanosis

- Neck for jugular vein distension (JVD) in upright position or with head of bed at 30- or 45-degree angle

- Chest for deformities and wounds/scars on chest

- Bilateral arms/hands, noting color, warmth, movement, sensation (CWMS), edema, and color of nail beds

- Bilateral legs, noting CWMS, edema to lower legs and feet, presence of superficial distended veins, and color of nail beds

- Auscultate with both the bell and the diaphragm of the stethoscope over five auscultation areas of the heart. Auscultate the apical pulse at the fifth intercostal space, midclavicular line for one minute. Note the rate and rhythm. Identify the S1 and S2 sounds and follow up on any unexpected findings (e.g., extra sounds or irregular rhythm).

- Palpate the radial, brachial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibialis pulses bilaterally. Palpate the carotid pulse one side at a time. Note presence/amplitude of pulse and any unexpected findings requiring follow-up.

- Palpate the nail beds on each extremity for capillary refill. Document the capillary refill time.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Learning Objectives

- Perform a respiratory assessment

- Differentiate between normal and abnormal lung sounds

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report deviations from norms

The evaluation of the respiratory system includes collecting subjective and objective data through a detailed interview and physical examination of the thorax and lungs. This examination can offer significant clues related to issues associated with the body's ability to obtain adequate oxygen to perform daily functions. Inadequacy in respiratory function can have significant implications for the overall health of the patient.

Admission: Refers to an initial visit or contact with a client.

Brief: A short session to share a plan, discuss team formation, assign roles and responsibilities, establish expectations and climate, and anticipate outcomes and contingencies.

Closed-loop communication: A communication strategy used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed.

Communication conflict: Occurs when there is a failure in the exchange of information.

Continuity of care: The use of information on past events and personal circumstances to make current care appropriate for each individual.[2]

Cultural diversity: A term used to describe cultural differences among clients, family members, and health care team members.

Cultural humility: A humble and respectful attitude toward individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases, realize they cannot possibly know everything about other cultures, and approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.[3]

CUS statements: Assertive statements that are well-recognized by all staff across a health care agency as implementation of the two-challenge rule. These assertive statements are “I am Concerned - I am Uncomfortable - This is a Safety issue!”[4]

Debrief: An informal information exchange session designed to improve team performance and effectiveness through reinforcement of positive behaviors and reflecting on lessons learned after a significant event occurs.

DESC: A tool used to help resolve conflict. DESC is a mnemonic that stands for Describe the specific situation or behavior and provide concrete data, Express how the situation makes you feel/what your concerns are using “I” messages, Suggest other alternatives and seek agreement, and Consequences are stated in terms of impact on established team goals while striving for consensus.

Discharge: The completion of care and services in a health care facility and the client is sent home (or to another health care facility).

Ethical conflict: Occurs when individuals or groups have fundamentally different beliefs and values.

Feedback: Information is provided to a team member for the purpose of improving team performance. Feedback should be timely, respectful, specific, directed towards improvement, and considerate.[5]

Goal conflict: Happens when the objectives of individuals or groups are incompatible.

Handoff reports: A transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care.[6]

Horizontal aggression: Hostile behavior among one’s peers.

Huddle: A brief meeting during a shift to reestablish situational awareness, reinforce plans already in place, and adjust the teamwork plan as needed.

I’M SAFE: A tool used to assess one’s own safety status, as well as that of other team members in their ability to provide safe patient care. It is a mnemonic standing for personal safety risks as a result of Illness, Medication, Stress, Alcohol and Drugs, Fatigue, and Eating and Elimination.

Interdisciplinary care conferences: Meetings where interprofessional team members professionally collaborate, share their expertise, and plan collaborative interventions to meet client needs.

Interprofessional collaborative practice: Multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds working together with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care.

I-PASS: A mnemonic used as a structured communication tool among interprofessional team members. I-PASS stands for Illness severity, Patient summary, Action list, Situation awareness, and Synthesis by the receiver.

ISBARR: A mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[7],[8]

Mutual support: The ability to anticipate and support team members' needs through accurate knowledge about their responsibilities and workload.

Personality conflict: Arises from differences in individual temperaments, attitudes, and behaviors.

Role conflict: Arises when individuals have multiple, often conflicting, expectations associated with their roles.

Shared mental model: The actions of a team leader that ensure all team members have situation awareness and are "on the same page" as situations evolve on the unit.[9]

Situation awareness: The awareness of a team member knowing what is going on around them.[10]

Situation monitoring: The process of continually scanning and assessing the situation to gain and maintain an understanding of what is going on around you.[11]

STEP tool: A situation monitoring tool used to know what is going on with you, your patients, your team, and your environment. STEP stands for Status of the patients, Team members, Environment, and Progress Toward Goal.[12]

TeamSTEPPS®: An evidence-based framework used to optimize team performance across the health care system. It is a mnemonic standing for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.[13]

Two-challenge rule: A strategy for advocating for patient safety that includes a team member assertively voicing their concern at least two times to ensure that it has been heard by the decision-maker.

Learning Objectives

- Perform a respiratory assessment

- Differentiate between normal and abnormal lung sounds

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report deviations from norms

The evaluation of the respiratory system includes collecting subjective and objective data through a detailed interview and physical examination of the thorax and lungs. This examination can offer significant clues related to issues associated with the body's ability to obtain adequate oxygen to perform daily functions. Inadequacy in respiratory function can have significant implications for the overall health of the patient.

External elements that impact healthcare costs.

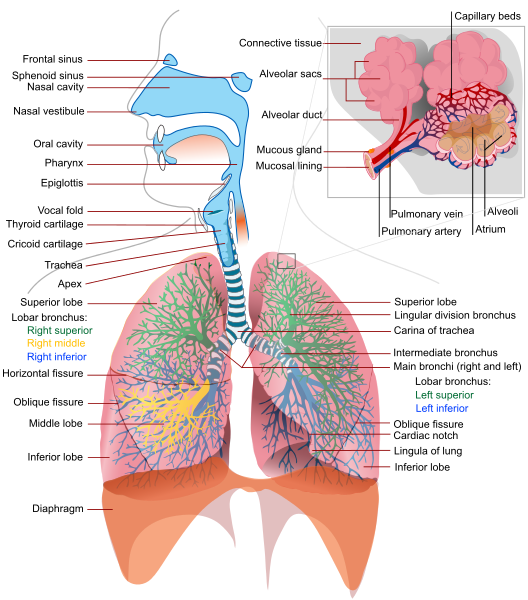

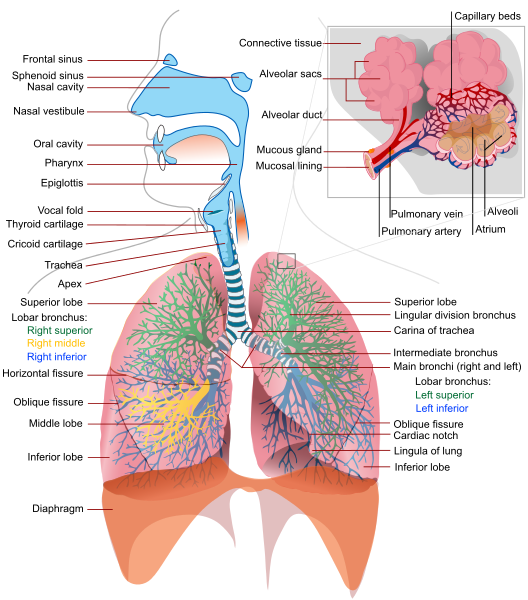

The main function of our respiratory system is to provide the body with a constant supply of oxygen and to remove carbon dioxide. To achieve these functions, muscles and structures of the thorax create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation. Respiration includes ventilation and gas exchange at the alveolar level where blood is oxygenated and carbon dioxide is removed. When completing a respiratory assessment, it is important for the nurse to understand the external and internal structures involved with respiration and ventilation. See Figure 10.1[14] for an illustration of the upper and lower respiratory system structures. Notice the lobular division of the lung structures and the bronchial tree.

For more information on basic oxygenation concepts, visit the "Oxygen Therapy" chapter of this book.

For more information about applying the nursing process to patients experiencing decreased oxygenation, visit the "Oxygenation" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

For a detailed review of the respiratory system, common respiratory disorders, and related medications, visit the "Respiratory" chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook. Specific sections of this chapter include the following:

The main function of our respiratory system is to provide the body with a constant supply of oxygen and to remove carbon dioxide. To achieve these functions, muscles and structures of the thorax create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation. Respiration includes ventilation and gas exchange at the alveolar level where blood is oxygenated and carbon dioxide is removed. When completing a respiratory assessment, it is important for the nurse to understand the external and internal structures involved with respiration and ventilation. See Figure 10.1[17] for an illustration of the upper and lower respiratory system structures. Notice the lobular division of the lung structures and the bronchial tree.

For more information on basic oxygenation concepts, visit the "Oxygen Therapy" chapter of this book.

For more information about applying the nursing process to patients experiencing decreased oxygenation, visit the "Oxygenation" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

For a detailed review of the respiratory system, common respiratory disorders, and related medications, visit the "Respiratory" chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook. Specific sections of this chapter include the following:

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Oral Medication Administration.”[20]

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

Special Considerations:

- Plan medication administration to avoid disruption.

- Dispense medication in a quiet area.

- Avoid conversation with others.

- Follow agency’s no-interruption zone policy.

- Perform hand hygiene prior to medication preparation.

- Prepare medications for ONE patient at a time.

- Gather supplies: MAR/eMAR.

- Know the actions, special nursing considerations, safe dose ranges, purpose of administration, and potential adverse effects of the medications to be administered. Consider the appropriateness of the medication for this patient at this time.

- Read the eMAR/MAR and select the proper medication from the medication supply system or the patient’s medication drawer. Perform the first of three checks of the six rights of medication administration plus two (allergies and expiration dates). Perform necessary calculations to verify correct dosage.

- The right patient: Check that you have the correct patient using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- The right medication (drug): Check that you have the correct medication and that it is appropriate for the patient in the current context.

- The right dose: Check that the dose is safe for the age, size, and condition of the patient. Different dosages may be indicated for different conditions.

- The right route: Check that the route is appropriate for the patient’s current condition.

- The right time: Adhere to the prescribed dose and schedule.

- The right documentation: Always verify any unclear or inaccurate documentation prior to administering medications.

- The medication label must be checked for name, dose, and route, and compared with the MAR at least three different times:

- When the medication is taken out of the drawer.

- When the medication is being prepared.

- At the bedside, prior to medication administration to the patient.

- Prepare the required medications:

- Unit dose packages: Do not open the wrapper until you are at the patient’s bedside. Keep opioids and medications that require special nursing assessments separate from other medication packages.

- Multi-dose containers: When removing tablets or capsules from a multi-dose bottle, pour the necessary number into the bottle cap and then place the tablets or capsules in a medication cup. Cut scored tablets, if necessary, to obtain the proper dosage. If it is necessary to touch the tablets, wear gloves.

- Liquid medication in a multi-dose bottle: When pouring liquid medications out of a multi-dose bottle, hold the bottle so the label is against the palm to avoid dripping on the label. Use an appropriate measuring device when pouring liquids and read the amount of medication at the bottom of the meniscus at eye level. Wipe the lip of the bottle with a paper towel.

- Depending on agency policy, the third check of the label may occur at this point. If so, after all medications for one patient have been prepared, recheck the medication labels against the eMAR/MAR before taking the medications to the patient. However, many agencies require the third check to be performed at the bedside after obtaining two patient identifiers and scanning the barcode of the patient.

- Replace any multi-dose containers in the patient’s drawer or medication supply system. Lock the medication supply system before leaving it.

- Transport the medications to the patient’s bedside carefully and keep the medications in sight at all times.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- When identifying the patient, compare the information with the eMAR/MAR. The patient should be identified using at least two of the following methods:

- Check the name on the patient’s identification band.

- Check the identification number on the patient’s identification band.

- Check the birth date on the patient’s identification band.

- Ask the patient to state their name and birth date, based on facility policy.

- If a patient is unable to verbalize their name and date of birth and patient identification bands are not used, use alternative methods of identification such as a second staff member and/or a patient picture in the MAR.

- Complete all necessary assessments before administering the medications. Check the patient’s allergy bracelet or ask the patient about allergies. Explain the purpose and action of each medication to the patient.

- Based on facility policy, the third check of the medication label typically occurs at this point. If so, recheck the label with the eMAR/MAR before administering the medications to the patient. Scan the patient’s barcode on the identification band, if bar scanning is used. If an error occurs during barcode scanning, obtain assistance before administering the medication. Most error messages are intended to warn the nurse of a potential medication error.

- Assist the patient to an upright (or a side-lying) position if they are unable to be positioned upright:

- Offer water or other permitted fluids with pills, capsules, tablets, and some liquid medications.

- Ask if the patient prefers to take the medications by hand or in a cup and if they prefer all medications at once or individually.

- Remain with the patient until each medication is swallowed. Never leave medication at the patient’s bedside.

- Note: If the patient is confused or has been known to hoard pills, have the patient open their mouth and check under the tongue.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document medication administration and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

- Evaluate the patient’s response to the medication within the appropriate time frame. Note: Most sublingual medications act in 15 minutes, and most oral medications act in 30 minutes. If patient presents with any adverse effects:

-

- Withhold further doses.

- Assess vital signs.

- Notify prescriber.

- Notify pharmacy.

- Document as per agency policy.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Oral Medication Administration.”[21]

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

Special Considerations:

- Plan medication administration to avoid disruption.

- Dispense medication in a quiet area.

- Avoid conversation with others.

- Follow agency’s no-interruption zone policy.

- Perform hand hygiene prior to medication preparation.

- Prepare medications for ONE patient at a time.

- Gather supplies: MAR/eMAR.

- Know the actions, special nursing considerations, safe dose ranges, purpose of administration, and potential adverse effects of the medications to be administered. Consider the appropriateness of the medication for this patient at this time.

- Read the eMAR/MAR and select the proper medication from the medication supply system or the patient’s medication drawer. Perform the first of three checks of the six rights of medication administration plus two (allergies and expiration dates). Perform necessary calculations to verify correct dosage.

- The right patient: Check that you have the correct patient using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- The right medication (drug): Check that you have the correct medication and that it is appropriate for the patient in the current context.

- The right dose: Check that the dose is safe for the age, size, and condition of the patient. Different dosages may be indicated for different conditions.

- The right route: Check that the route is appropriate for the patient’s current condition.

- The right time: Adhere to the prescribed dose and schedule.

- The right documentation: Always verify any unclear or inaccurate documentation prior to administering medications.

- The medication label must be checked for name, dose, and route, and compared with the MAR at least three different times:

- When the medication is taken out of the drawer.

- When the medication is being prepared.

- At the bedside, prior to medication administration to the patient.

- Prepare the required medications:

- Unit dose packages: Do not open the wrapper until you are at the patient’s bedside. Keep opioids and medications that require special nursing assessments separate from other medication packages.

- Multi-dose containers: When removing tablets or capsules from a multi-dose bottle, pour the necessary number into the bottle cap and then place the tablets or capsules in a medication cup. Cut scored tablets, if necessary, to obtain the proper dosage. If it is necessary to touch the tablets, wear gloves.

- Liquid medication in a multi-dose bottle: When pouring liquid medications out of a multi-dose bottle, hold the bottle so the label is against the palm to avoid dripping on the label. Use an appropriate measuring device when pouring liquids and read the amount of medication at the bottom of the meniscus at eye level. Wipe the lip of the bottle with a paper towel.

- Depending on agency policy, the third check of the label may occur at this point. If so, after all medications for one patient have been prepared, recheck the medication labels against the eMAR/MAR before taking the medications to the patient. However, many agencies require the third check to be performed at the bedside after obtaining two patient identifiers and scanning the barcode of the patient.

- Replace any multi-dose containers in the patient’s drawer or medication supply system. Lock the medication supply system before leaving it.

- Transport the medications to the patient’s bedside carefully and keep the medications in sight at all times.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- When identifying the patient, compare the information with the eMAR/MAR. The patient should be identified using at least two of the following methods:

- Check the name on the patient’s identification band.

- Check the identification number on the patient’s identification band.

- Check the birth date on the patient’s identification band.

- Ask the patient to state their name and birth date, based on facility policy.

- If a patient is unable to verbalize their name and date of birth and patient identification bands are not used, use alternative methods of identification such as a second staff member and/or a patient picture in the MAR.

- Complete all necessary assessments before administering the medications. Check the patient’s allergy bracelet or ask the patient about allergies. Explain the purpose and action of each medication to the patient.

- Based on facility policy, the third check of the medication label typically occurs at this point. If so, recheck the label with the eMAR/MAR before administering the medications to the patient. Scan the patient’s barcode on the identification band, if bar scanning is used. If an error occurs during barcode scanning, obtain assistance before administering the medication. Most error messages are intended to warn the nurse of a potential medication error.

- Assist the patient to an upright (or a side-lying) position if they are unable to be positioned upright:

- Offer water or other permitted fluids with pills, capsules, tablets, and some liquid medications.

- Ask if the patient prefers to take the medications by hand or in a cup and if they prefer all medications at once or individually.

- Remain with the patient until each medication is swallowed. Never leave medication at the patient’s bedside.

- Note: If the patient is confused or has been known to hoard pills, have the patient open their mouth and check under the tongue.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document medication administration and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

- Evaluate the patient’s response to the medication within the appropriate time frame. Note: Most sublingual medications act in 15 minutes, and most oral medications act in 30 minutes. If patient presents with any adverse effects:

-

- Withhold further doses.

- Assess vital signs.

- Notify prescriber.

- Notify pharmacy.

- Document as per agency policy.

With an understanding of the basic structures and primary functions of the respiratory system, the nurse collects subjective and objective data to perform a focused respiratory assessment.

Subjective Assessment

Collect data using interview questions, paying particular attention to what the patient is reporting. The interview should include questions regarding any current and past history of respiratory health conditions or illnesses, medications, and reported symptoms. Consider the patient’s age, gender, family history, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health practices when gathering subjective data. The information discovered during the interview process guides the physical exam and subsequent patient education. See Table 10.3a for sample interview questions to use during a focused respiratory assessment.[22]

Table 10.3a Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of the Respiratory System

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a respiratory condition, such as asthma, COPD, pneumonia, or allergies?

Do you use oxygen or peak flow meter? Do you use home respiratory equipment like CPAP, BiPAP, or nebulizer devices? |

Please describe the conditions and treatments. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements for respiratory concerns? | Please identify what you are taking and the purpose of each. |

| Have you had any feelings of breathlessness

(dyspnea)? |

Note: If the shortness of breath is severe or associated with chest pain, discontinue the interview and obtain emergency assistance.

Are you having any shortness of breath now? If yes, please rate the shortness of breath from 0-10 with "0" being none and "10" being severe? Does anything bring on the shortness of breath (such as activity, animals, food, or dust)? If activity causes the shortness of breath, how much exertion is required to bring on the shortness of breath? When did the shortness of breath start? Is the shortness of breath associated with chest pain or discomfort? How long does the shortness of breath last? What makes the shortness of breath go away? Is the shortness of breath related to a position, like lying down? Do you sleep in a recliner or upright in bed? Do you wake up at night feeling short of breath? How many pillows do you sleep on? How does the shortness of breath affect your daily activities? |

| Do you have a cough? | When you cough, do you bring up anything? What color is the phlegm?

Do you cough up any blood (hemoptysis)? Do you have any associated symptoms with the cough such as fever, chills, or night sweats? How long have you had the cough? Does anything bring on the cough (such as activity, dust, animals, or change in position)? What have you used to treat the cough? Has it been effective? |

| Do you smoke or vape? | What products do you smoke/vape? If cigarettes are smoked, how many packs a day do you smoke?