11.2 Review of Anatomy & Physiology of the Gastrointestinal System

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

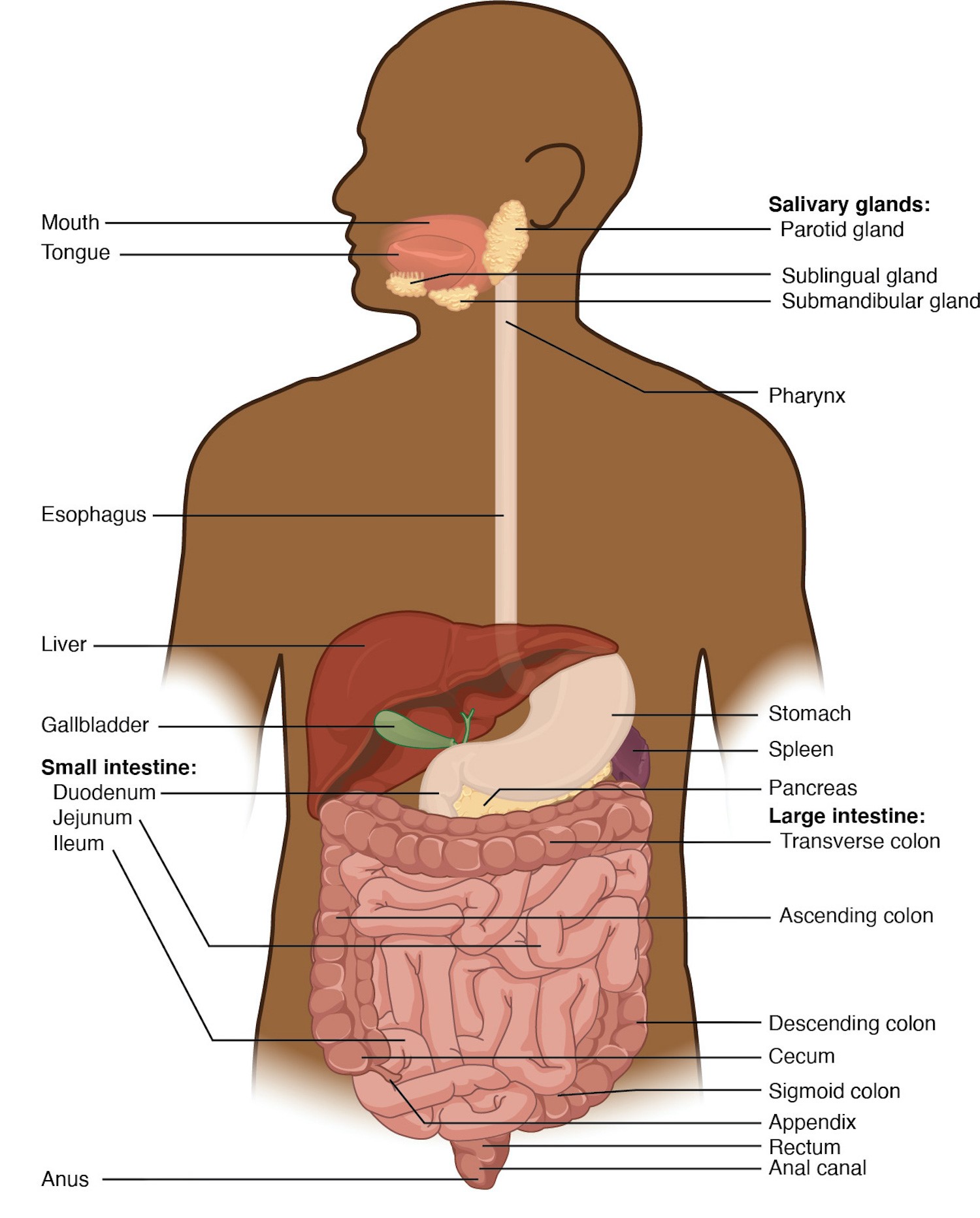

This section will review the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system, including the mouth, tongue, salivary glands, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, as well as the accessory organs of the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. See Figure 11.1[1] for an illustration of gastrointestinal system organs.

Anatomy

Mouth

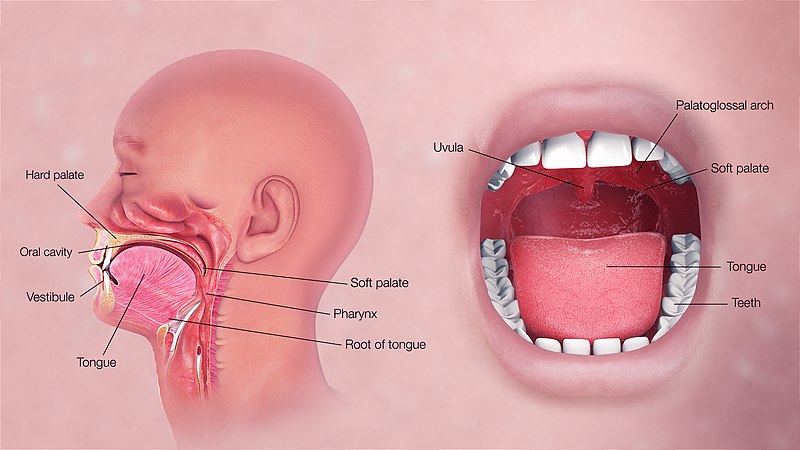

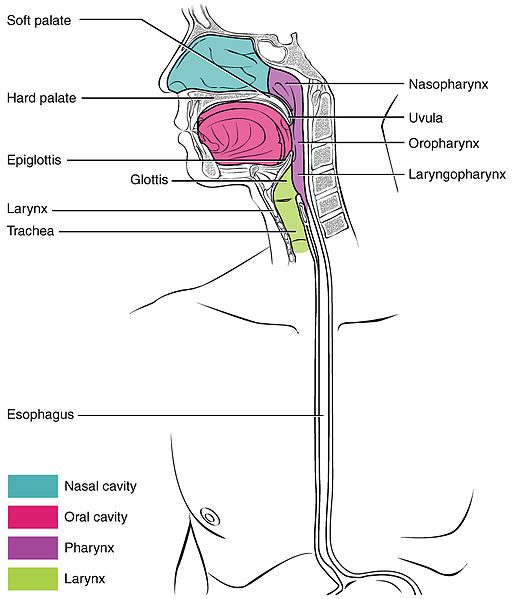

The mouth, cheeks, tongue, and palate form the oral cavity. See Figure 11.2[2] for an illustration of the oral cavity. If you run your tongue along the roof of your mouth, you’ll notice the roof of the mouth has an arch called a hard palate. The anterior region of the palate serves as a septum (i.e., wall) between the oral and nasal cavities, as well as a rigid shelf against which the tongue can push food when swallowing. The hard palate ends in the posterior oral cavity where the tissue becomes fleshier. This part of the palate, known as the soft palate, is composed mainly of skeletal muscle that can be manipulated for actions like swallowing or singing.[3]

A fleshy extension of tissue called the uvula drops down from the center of the soft palate. When swallowing, the soft palate and uvula move upward, helping to keep foods and liquid from entering the nasal cavity and respiratory tract.[4]

Two muscular folds extend downward from the soft palate on either side of the uvula. Between these two folds are the palatine tonsils, clusters of lymphoid tissue that protect the pharynx. The lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue.[5]

Tongue

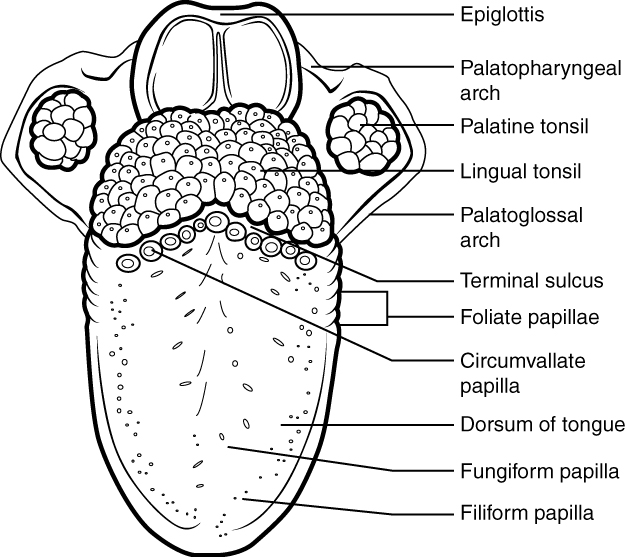

The tongue facilitates ingestion, digestion, sensation (of taste, texture, and temperature of food), swallowing, and vocalization. It has a mucous membrane covering and is composed of skeletal muscles that facilitate eating, swallowing, and speaking. The top and sides of the tongue are studded with papillae and taste buds to facilitate sensation. Lingual glands secrete mucus and a watery fluid that contains the enzyme lipase, which plays an initial role in breaking down food before it reaches the stomach.[6] See Figure 11.3[7] for an illustration of the papillae on the tongue.

Salivary Glands

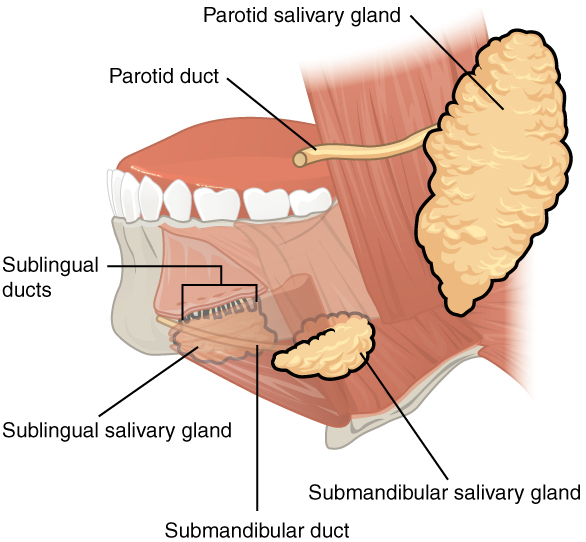

Many small salivary glands are housed within the mucous membranes of the mouth and tongue that are constantly secreting saliva into the oral cavity or indirectly through salivary ducts. Saliva moistens the mouth and teeth and increases when eating to moisten food and initiate the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates and fats.[8] See Figure 11.4[9] for an illustration of the salivary glands.

Pharynx

The pharynx, commonly called the throat, is a tube of muscle lined with a mucous membrane that runs from the posterior oral and nasal cavities to the opening of the esophagus and larynx.[10] See Figure 11.5[11] for an illustration of the pharynx.

The pharynx has three subdivisions. The superior section, the nasopharynx, is involved only in breathing and speech. The other two subdivisions, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx, are used for both breathing and digestion. The oropharynx begins inferior to the nasopharynx and continues to the laryngopharynx. The inferior border of the laryngopharynx connects to the esophagus, whereas the anterior portion connects to the larynx.[12]

The pharynx is involved in both digestion and breathing. It receives air from the mouth and nasal cavities and food from the mouth. When food enters the pharynx, involuntary muscle contractions close the epiglottis to prevent food from entering the larynx and trachea, and food enters the esophagus.[13]

Esophagus

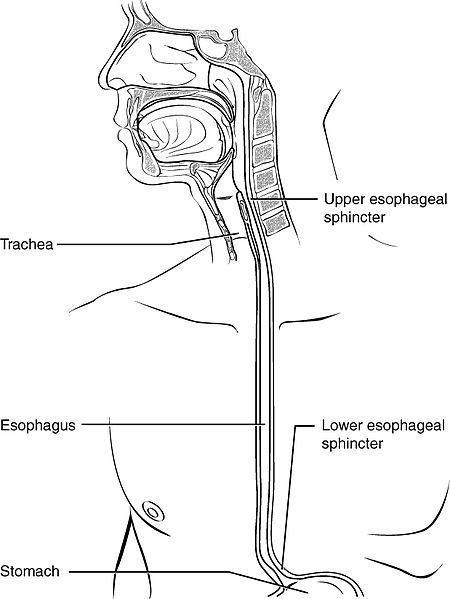

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. It is located posteriorly to the trachea and is approximately ten inches long. See Figure 11.6[14] for an illustration of the esophagus. The upper esophageal sphincter controls the movement of food from the pharynx to the esophagus. Recall that sphincters are muscles that surround tubes and serve as valves, closing the tube when the sphincters contract and opening it when they relax.[15]

The upper two thirds of the esophagus consist of muscles. A series of contractions called peristalsis push food through the esophagus and into the stomach. Just before the opening to the stomach is a ring-shaped muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This sphincter opens to let food pass into the stomach and closes to keep it there.[16]

Stomach

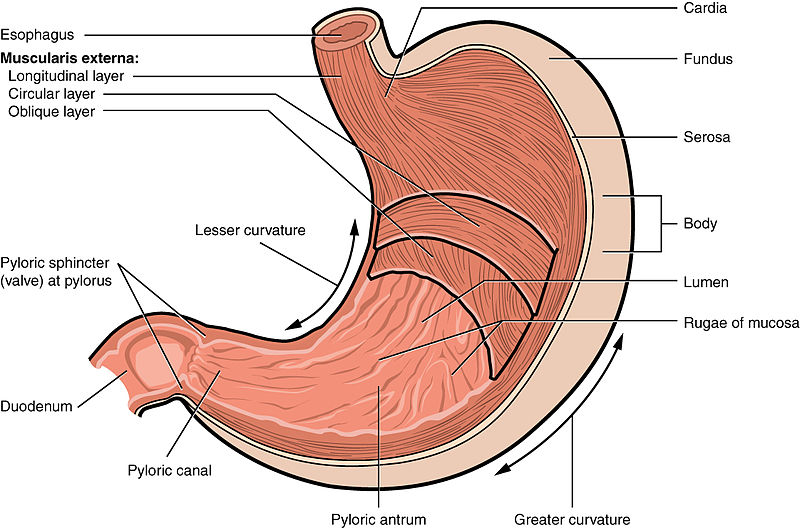

The stomach is a sac-like organ where food is mixed with gastric juice. There are four main regions in the stomach: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. The funnel-shaped pylorus connects the stomach to the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. The pyloric sphincter is located at this latter point of connection and controls stomach emptying into the small intestine.[17] See Figure 11.7[18] for an illustration of the stomach.

The inner lining of the stomach is covered by a mucous membrane that secretes a protective coat of alkaline mucus. The mucus protects the stomach from corrosive stomach acid. Gastric glands lie under the surface of this lining and secrete a complex digestive fluid referred to as gastric juice. Gastric juice consists of the following components: water, mucus, hydrochloric acid, pepsin, and intrinsic factor. The purpose of gastric juice is not only to help with the breakdown of food, but also to protect the client against infectious agents, which may be deterred by the acidic environment. Some of the components of gastric juice will be discussed in more detail below.[19]

Parietal cells and chief cells are found within the gastric glands. Parietal cells produce and secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) to maintain the acidity of the environment with a pH of 1 to 4. Parietal cells also secrete a substance called intrinsic factor, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine. Parietal cells are the primary site of action for many drugs that treat acid-related disorders. Chief cells secrete pepsinogen that becomes pepsin when exposed to acid. Pepsin is a digestive enzyme that breaks down protein.[20],[21],[22],[23],[24]

The stomach also contains enteroendocrine cells (ECL or enterochromaffin-like cells) located in the gastric glands that secrete substances, including serotonin, histamine, and somatostatin. Serotonin, also known as 5-HT, aids in intestinal motility and nutrient absorption and also plays a role in gastrointestinal inflammation. Histamine and somatostatin help regulate the secretion of gastric acid. Histamine leads to the secretion of gastric acid by acting on parietal cells, and somatostatin inhibits parietal cells or histamine release to decrease gastric acid levels. Additionally, G cells in the stomach secrete gastrin that promotes secretions of digestive substances. Although all these cells play an important role in the digestive system, acid-related diseases, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, can occur when there is an imbalance of secretions.[25],[26],[27],[28]

The muscular walls of the stomach move food through the stomach and vigorously churn it, mechanically breaking it down into smaller particles.

Small Intestine

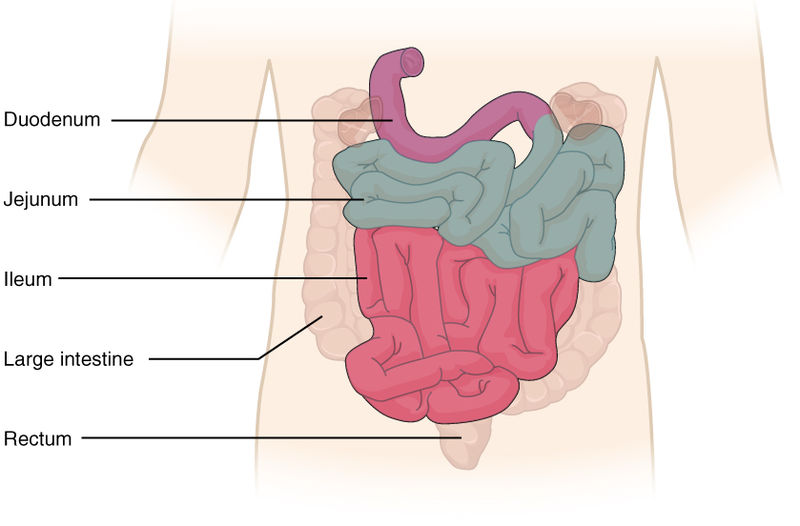

Partially digested food, called chyme, is released from the stomach via the pyloric sphincter and enters the small intestine, the part of the digestive tract where most of the digestion and absorption into the blood occurs. Approximately 90 percent of nutrients from food are absorbed through villi, small fingerlike extensions on the inner surface of the small intestine. The small intestine is about ten feet long. Its name derives from its small diameter of about one inch, compared to the large intestine’s diameter of about three inches.[29]

The coiled tube of the small intestine is subdivided into three regions called the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The ileum joins the cecum of the large intestine at the ileocecal sphincter. The ileocecal valve controls the flow of chyme from the small intestine to the large intestine.[30] See Figure 11.8[31] for an illustration of these regions.

Large Intestine

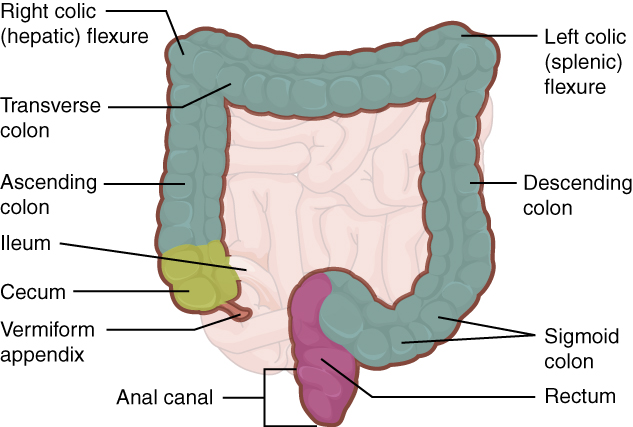

The large intestine runs from the cecum to the anus. The primary functions of the large intestine are to finish absorption of nutrients and water, synthesize certain vitamins, and form and eliminate feces, also called stool. The large intestine is about one half the length of the small intestine but is called large because its diameter is three inches, about three times the diameter of the small intestine. The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anal canal. The colon is further subdivided into the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon.[32] See Figure 11.9[33] for an illustration of the large intestine.

Cecum

The cecum is the initial part of the large intestine. It receives the contents of the small intestine and continues absorbing water and salts. The appendix is a small pouch attached to the end of the cecum. Its twisted anatomy provides a haven for the accumulation and multiplication of enteric bacteria that can lead to appendicitis.[34]

Colon

Food residue entering the colon travels up the ascending colon on the right side of the abdomen. At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to become the transverse colon, where it travels across to the left side of the abdomen. From there, chyme passes through the descending colon, which runs down the left side of the posterior abdominal wall and becomes the S-shaped sigmoid colon.[35]

Rectum

The rectum is the final eight inches of the large intestine. It has three folds, called the rectal valves, that help separate feces from flatus, commonly referred to as gas.[36]

Anal Canal

The anal canal is about three inches long and opens to the exterior of the body at the anus, the end of the digestive tract. The anal canal includes two sphincters. The internal anal sphincter is made of smooth muscle, and its contractions are involuntary. The external anal sphincter is made of skeletal muscle, which is under voluntary control. Except when defecating, both sphincters usually remain closed.[37]

Accessory Organs of Digestion

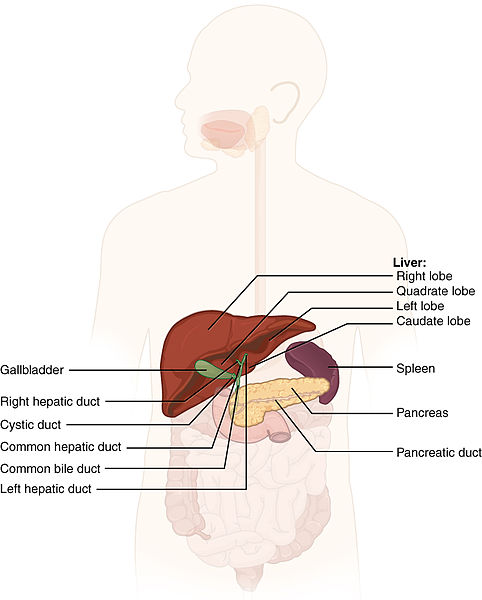

Chemical digestion in the small intestine relies on the activities of three accessory digestive organs: the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. See Figure 11.10[38] for an illustration of these accessory organs. The digestive role of the liver is to produce bile and export it to the duodenum. The gallbladder stores, concentrates, and releases bile. The pancreas produces pancreatic juice, which contains digestive enzymes and bicarbonate ions, and delivers it to the duodenum via the common bile duct.[39]

Liver

The liver weighs about three pounds in an adult. In addition to being an accessory digestive organ, it plays a number of roles in metabolism, blood clotting, protein creation, and cleansing the blood of toxins. The liver lies inferior to the diaphragm in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity. It is protected by the surrounding ribs. The liver is divided into two primary lobes, a large right lobe and a much smaller left lobe.[40]

Hepatic Portal Circulation

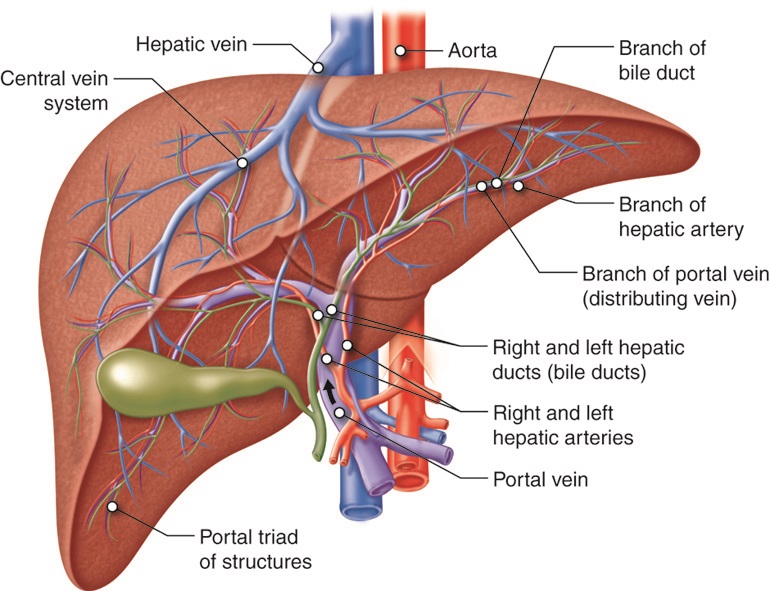

The portal vein delivers nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine to the liver. This blood contains nutrients, toxins, and medications that are absorbed and metabolized by the liver. The hepatic artery also delivers oxygenated blood from the heart to the liver. After the liver processes the blood and metabolizes nutrients and toxins, it releases blood through the hepatic vein into the inferior vena cava. This is referred to as hepatic portal circulation.[41] See Figure 11.11[42] for an illustration of hepatic portal circulation.

Bile

Proteins, iron, and bilirubin are transported in the blood to the liver. In the liver, proteins and iron are recycled, whereas bilirubin is excreted in the bile. Bilirubin, a yellowish pigment produced by the breakdown of red blood cells, gives bile its color. Bile is a digestive fluid produced and secreted by the liver that breaks down lipids in the small intestine. Bilirubin is eventually transformed by intestinal bacteria into a brown pigment that gives stool its characteristic color.

In some diseases, bile does not enter the intestine, resulting in white stool with a high fat content because virtually no fats are broken down by the bile. Steatorrhea refers to fatty stool.[43]

Pancreas

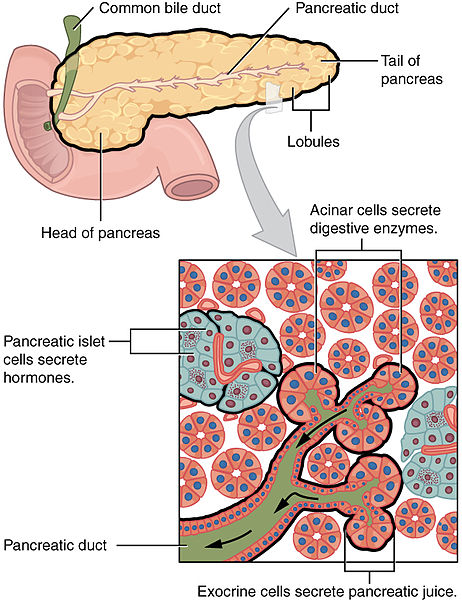

The soft, oblong, glandular pancreas lies transversely in the retroperitoneum behind the stomach. The pancreas has two functions referred to as exocrine, meaning secreting digestive enzymes, and endocrine, meaning releasing hormones into the blood.[44]

The pancreas produces protein-digesting enzymes in their inactive forms that are activated in the duodenum, so they don’t attack the pancreas. Enzymes that don’t attack the pancreas are secreted in their active forms, such as amylase that digests carbohydrates and lipase that digests fat. The pancreas delivers this pancreatic juice to the duodenum through the common bile duct (carrying bile from the liver and gallbladder) just before entering the duodenum. The pancreatic islet cells secrete hormones such as insulin and glucagon.[45] See Figure 11.12[46] for an illustration of the pancreas.

For more information on the hormone functions of the pancreas, view the “Endocrine Alterations” chapter.

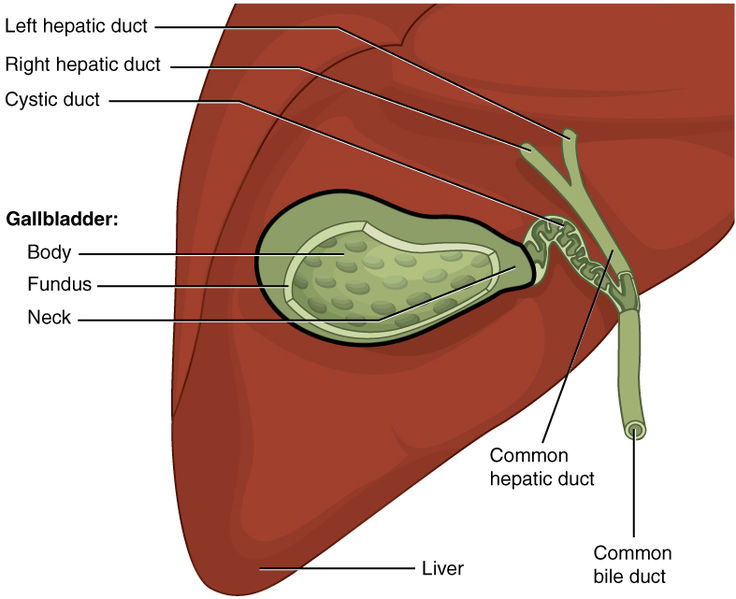

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is about three to four inches long and is nested in a shallow area on the posterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver. This muscular sac stores, concentrates, and propels bile into the duodenum via the common bile duct.[47] See Figure 11.13[48] for an illustration of the gallbladder.

Physiology of the Digestive System

The main functions of the digestive system are ingesting food, digesting food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating waste products.[49] See Table 11.2 for an overview of the functions of the organs of the digestive tract.

Table 11.2. Functions of the Digestive Organs[50]

| Organ | Major Functions | Other Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Mouth | Ingests food

Chews and mixes food Begins chemical breakdown of carbohydrates via salivary amylase Moves food into the pharynx Begins breakdown of lipids via lingual lipase |

Moistens and dissolves food, allowing taste

Cleans and lubricates the teeth and oral cavity Promotes some antimicrobial activity |

| Pharynx | Propels food from the oral cavity to the esophagus | Lubricates food and passageways |

| Esophagus | Propels food to the stomach | Lubricates food and passageways |

| Stomach | Mixes and churns food with gastric juices to form chyme

Begins chemical breakdown of proteins Releases food into the duodenum as chyme Absorbs some fat-soluble substances Possesses antimicrobial functions |

Stimulates protein-digesting enzymes

Secretes intrinsic factor required for vitamin B12 absorption in small intestine |

| Small Intestine | Mixes chyme with digestive juices

Propels food at a rate slow enough for digestion and absorption Absorbs breakdown products of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, along with vitamins, minerals, and water Performs physical digestion via segmentation, the mechanical mixing of food with digestive juices |

Provides optimal medium for enzymatic activity |

| Large Intestine | Further breaks down food residues

Absorbs most residual water, electrolytes, and vitamins produced by enteric bacteria Propels feces toward rectum Eliminates feces |

Food residue is concentrated and temporarily stored prior to defecation

Mucus eases passage of feces through colon |

| Accessory Organs | Liver produces bile salts, which emulsify lipids, aiding in their digestion and absorption

Gallbladder stores, concentrates, and releases bile Pancreas produces digestive enzymes and bicarbonate |

Bicarbonate-rich pancreatic juices help neutralize acidic chyme and provide optimal environment for enzymatic activity |

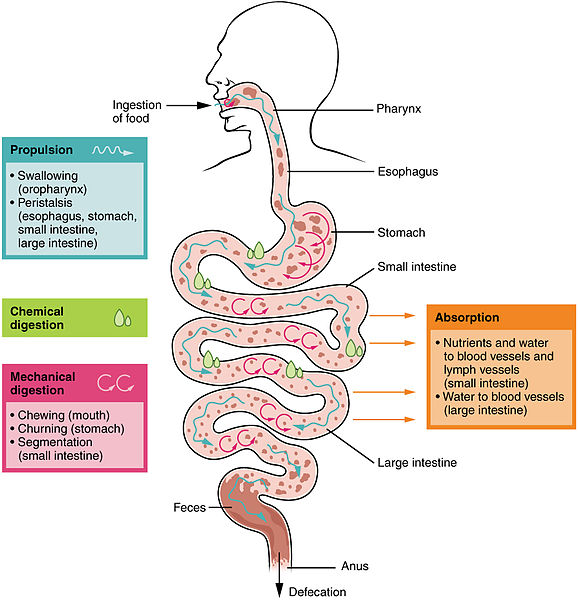

Digestive Processes

Digestive processes involve the interaction of several organs and occur gradually as food moves through the gastrointestinal tract. The processes of digestion include six activities: ingestion, propulsion, mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption, and defecation.[51],[52],[53] See Figure 11.14[54] for an illustration of digestive processes.

Ingestion

Ingestion refers to the entry of food through the mouth where it is chewed and mixed with saliva. Saliva contains enzymes that begin breaking down the carbohydrates and fats in the food. Chewing produces a soft mass of food called a bolus that is an appropriate size for swallowing.[55],[56],[57]

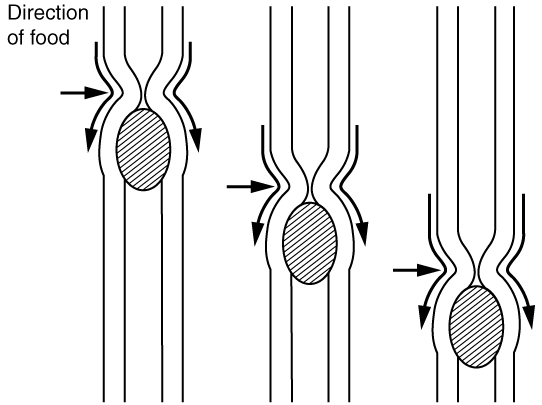

Propulsion

Food leaves the mouth when the tongue and pharyngeal muscles propel it into the esophagus. This act of swallowing is an example of propulsion, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis. Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of alimentary wall smooth muscles, which act to propel food. See Figure 11.15[58] for an illustration of peristalsis. Peristaltic waves also play a role in mixing food with digestive juices. Peristalsis is so powerful that swallowed foods and liquids enter the stomach even if you are standing on your head.[59],[60],[61]

Mechanical Digestion

Mechanical digestion is a physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food but makes it smaller to increase its surface area and mobility. Mechanical digestion starts with chewing and then progresses to mechanical churning of food in the stomach. In the stomach, the bolus of food further breaks apart, allowing for more surface area to be exposed to the digestive juices of chemical digestion. Mechanical digestion also occurs in the small intestine, but to a lesser extent than what occurs in the stomach.[62],[63],[64]

Chemical Digestion

Chemical digestion begins in the mouth and is completed in the small intestine. Digestive secretions contain water, enzymes, acids, and salts that create an acidic “soup” that breaks down food molecules into their chemical building blocks. For example, proteins are broken down into amino acids.[65],[66],[67]

Absorption

Nutrients are substances that provide nourishment to cells. After food molecules have been broken down during chemical digestion, nutrients enter the bloodstream through the process of absorption. Absorption takes place primarily in the small intestine.[68],[69],[70]

Defecation

During defecation, the final step in digestion, undigested materials are removed from the body as feces. The process of defecation begins when mass movements, strong contractions that quickly move undigested materials, force feces from the colon into the rectum, stretching the rectal wall and provoking the defecation reflex, which eliminates feces from the rectum. This parasympathetic reflex is mediated by the spinal cord. It contracts the sigmoid colon and rectum, relaxes the internal anal sphincter, and initially contracts the external anal sphincter. Figure 11.16[71] reviews the anatomy of the rectum and its external and internal sphincters. The presence of feces in the anal canal sends a signal to the brain, which gives the person the choice of voluntarily opening the external anal sphincter (defecating) or keeping it temporarily closed. If defecation is delayed until a more convenient time, it takes a few seconds for the reflex contractions to stop and the rectal walls to relax. The next mass movement will trigger additional defecation reflexes until defecation occurs.[72],[73],[74]

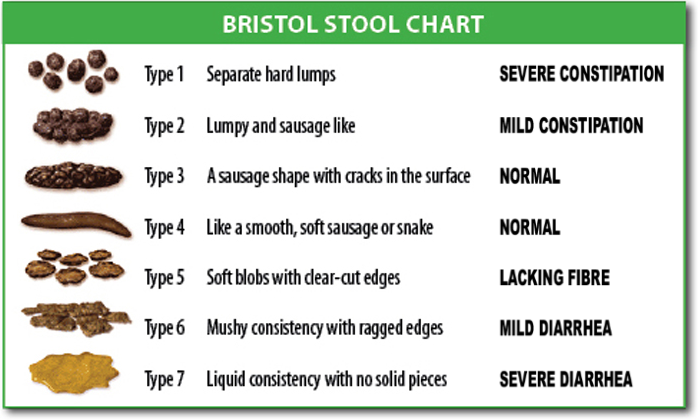

If defecation is delayed for an extended time, additional water is absorbed, making the feces firmer and potentially leading to constipation. Alternatively, if the waste matter moves too quickly through the intestines, not enough water is absorbed, and diarrhea can result. Figure 11.17[75] demonstrates the Bristol Stool Chart that is used to assess stool characteristics, ranging from very constipated to diarrhea.

- “abe85277d60c52f85be133e1b5ddc40aea009e1c.jpg” by J. Gordon Betts, et al. is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/23-1-overview-of-the-digestive-system ↵

- This image is a derivative of “3D_Medical_Animation_Oral_Cavity.jpg” by https://www.scientificanimations.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2407_Tongue.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2408_Salivary_Glands.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2411_Pharynx.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2412_The_Esophagus.jpg” by OpenStax College is CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2414_Stomach.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Pepsin by Heda, Toro, & Tombazzi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Stomach by Hsu, Safadi, & Lui is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Latorre, R., Sternini, C., De Giorgio, R., & Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B. (2015). Enteroendocrine cells: A review of their role in brain-gut communication. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 28(5), 620-630. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12754 ↵

- The Role of Serotonin Neurotransmission in Gastrointestinal Tract and Pharmacotherapy by Guzel & Mirowska-Guzel is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Pepsin by Heda, Toro, & Tombazzi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Stomach by Hsu, Safadi, & Lui is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Latorre, R., Sternini, C., De Giorgio, R., & Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B. (2015). Enteroendocrine cells: A review of their role in brain-gut communication. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 28(5), 620-630. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12754 ↵

- The Role of Serotonin Neurotransmission in Gastrointestinal Tract and Pharmacotherapy by Guzel & Mirowska-Guzel is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2417_Small_IntestineN.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2420_Large_Intestine.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2422_Accessory_Organs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cenveo - Drawing Liver anatomy and vascularisation - English labels” by Cenveo is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2424_Exocrine_and_Endocrine_Pancreas.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2425_Gallbladder.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “2405_Digestive_Process.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “2404_PeristalsisN.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “Anorectum.gif” by U.S. Government, National Institutes of Health is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Pharmacology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “BristolStoolChart.png” by Cabot Health, Bristol Stool Chart is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

Prioritization

As new nurses begin their career, they look forward to caring for others, promoting health, and saving lives. However, when entering the health care environment, they often discover there are numerous and competing demands for their time and attention. Patient care is often interrupted by call lights, rounding physicians, and phone calls from the laboratory department or other interprofessional team members. Even individuals who are strategic and energized in their planning can feel frustrated as their task lists and planned patient-care activities build into a long collection of “to dos.”

Without utilization of appropriate prioritization strategies, nurses can experience time scarcity, a feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against them. Functioning under the burden of time scarcity can cause feelings of frustration, inadequacy, and eventually burnout. Time scarcity can also impact patient safety, resulting in adverse events and increased mortality.[1] Additionally, missed or rushed nursing activities can negatively impact patient satisfaction scores that ultimately affect an institution's reimbursement levels.

It is vital for nurses to plan patient care and implement their task lists while ensuring that critical interventions are safely implemented first. Identifying priority patient problems and implementing priority interventions are skills that require ongoing cultivation as one gains experience in the practice environment.[2] To develop these skills, students must develop an understanding of organizing frameworks and prioritization processes for delineating care needs. These frameworks provide structure and guidance for meeting the multiple and ever-changing demands in the complex health care environment.

Let’s consider a clinical scenario in the following box to better understand the implications of prioritization and outcomes.

Scenario A

Imagine you are beginning your shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. You receive a handoff report on four medical-surgical patients from the night shift nurse:

- Patient A is a 34-year-old total knee replacement patient, post-op Day 1, who had an uneventful night. It is anticipated that she will be discharged today and needs patient education for self-care at home.

- Patient B is a 67-year-old male admitted with weakness, confusion, and a suspected urinary tract infection. He has been restless and attempting to get out of bed throughout the night. He has a bed alarm in place.

- Patient C is a 49-year-old male, post-op Day 1 for a total hip replacement. He has been frequently using his patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump and last rated his pain as a "6."

- Patient D is a 73-year-old male admitted for pneumonia. He has been hospitalized for three days and receiving intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His next dose is due in an hour. His oxygen requirements have decreased from 4 L/minute of oxygen by nasal cannula to 2 L/minute by nasal cannula.

Based on the handoff report you received, you ask the nursing assistant to check on Patient B while you do an initial assessment on Patient D. As you are assessing Patient D's oxygenation status, you receive a phone call from the laboratory department relating a critical lab value on Patient C, indicating his hemoglobin is low. The provider calls and orders a STAT blood transfusion for Patient C. Patient A rings the call light and states she and her husband have questions about her discharge and are ready to go home. The nursing assistant finds you and reports that Patient B got out of bed and experienced a fall during the handoff reports.

It is common for nurses to manage multiple and ever-changing tasks and activities like this scenario, illustrating the importance of self-organization and priority setting. This chapter will further discuss the tools nurses can use for prioritization.

In addition to using established frameworks to resolve ethical dilemmas, nurses can also consult their organization’s ethics committee for ethical guidance in the workplace. Ethics committees are typically composed of interdisciplinary team members such as physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, administrators, social workers, and clergy to problem-solve ethical dilemmas. See Figure 6.8[3] for an illustration of an ethics committee. Hospital ethics committees were created in response to legal controversies regarding the refusal of life-sustaining treatment, such as the Karen Quinlan case.[4] Read more about the Karen Quinlan case and controversies surrounding life-sustaining treatment in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

After the passage of the Patient Self-Determination Act in 1991, all health care institutions receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding are required to form ethics committees. The Joint Commission (TJC) also requires organizations to have a formalized mechanism of dealing with ethical issues. Nurses should be aware of the process for requesting guidance and support from ethics committees at their workplace for ethical issues affecting patients or staff.[5]

Institutional Review Boards and Ethical Research

Other types of ethics committees have been formed to address the ethics of medical research on patients. Historically, there are examples of medical research causing harm to patients. For example, an infamous research study called the “Tuskegee Study” raised concern regarding ethical issues in research such as informed consent, paternalism, maleficence, truth-telling, and justice.

In 1932 the Tuskegee Study began a 40-year study looking at the long-term progression of syphilis. Over 600 Black men were told they were receiving free medical care, but researchers only treated men diagnosed with syphilis with aspirin, even after it was discovered that penicillin was a highly effective treatment for the disease. The institute allowed the study to go on, even when men developed long-stage neurological symptoms of the disease and some wives and children became infected with syphilis. In 1972 these consequences of the Tuskegee Study were leaked to the media and public outrage caused the study to shut down.[6]

Potential harm to patients participating in research studies like the Tuskegee Study was rationalized based on the utilitarian view that potential harm to individuals was outweighed by the benefit of new scientific knowledge resulting in greater good for society. As a result of public outrage over ethical concerns related to medical research, Congress recognized that an independent mechanism was needed to protect research subjects. In 1974 regulations were established requiring research with human subjects to undergo review by an institutional review board (IRB) to ensure it meets ethical criteria. An IRB is group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects.[7] The IRB review ensures the following criteria are met when research is performed:

- The benefits of the research study outweigh the potential risks.

- Individuals’ participation in the research is voluntary.

- Informed consent is obtained from research participants who have the ability to decline participation.

- Participants are aware of the potential risks of participating in the research.[8]

The Open RN Nursing Skills OER textbook was developed based on several external standards and uses a conceptual approach across all chapters.

External Standards

American Nurses Association (ANA):

The ANA provides standards for professional nursing practice, including nursing standards and a code of ethics for nurses.

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/standards/

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses

The National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses: NCLEX-PN and NCLEX-RN Test Plans

The NCLEX-RN and NCLEX-PN test plans are updated every three years to reflect fair, comprehensive, current, and entry-level nursing competency measurement. Multiple resources are used to create the test plans, including recent practice analysis of nurses and expert opinions of the NEC, NCSBN staff, and boards of nursing/regulatory bodies, to ensure that the test plan is consistent with nurse practice acts.

The National League of Nursing (NLN): Competencies for Graduates of Nursing Programs

NLN competencies guide nursing curricula to position graduates in a dynamic health care arena with practice that is informed by a body of knowledge and ensures that all members of the public receive safe, quality care.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN): The Essentials: Competencies for Professional Nursing Education

The AACN provides a framework for preparing individuals as members of the discipline of nursing, reflecting expectations across

the trajectory of nursing education and applied experience.

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) Institute: Pre-licensure Competencies

Quality and safety competencies include knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be developed in nursing pre-licensure programs. QSEN competencies include patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, safety, and informatics.

Wisconsin State Legislature, Administrative Code Chapter N6

The Wisconsin Administrative Code governs the Registered Nursing and Practical Nursing professions in Wisconsin.

Healthy People 2030

Healthy People 2030 envisions a society in which all people can achieve their full potential for health and well-being across the life span. Healthy People provides objectives based on national data and includes social determinants of health.

Conceptual Approach

The Open RN Nursing Skills textbook incorporates the following concepts across all chapters.

- Holism. Florence Nightingale taught nurses to focus on the principles of holism, including wellness and the interrelationship of human beings and their environment. This textbook encourages the application of holism by assessing the impact of developmental, emotional, cultural, religious, and spiritual influences on a patient’s health status.

- Evidence Based Practice (EBP). Textbook content is based on current, evidence-based practices that are referenced by footnotes. To promote digital literacy, hyperlinks are provided to credible, free, online resources that supplement content. The Open RN textbooks will be updated as new EBP is established and with the release of updated NCLEX Test Plans every three years.

- Cultural Competency. Nurses have an ethical and moral obligation to provide culturally competent care to the patients they serve based on the ANA Code of Ethics.[10] Cultural considerations are included throughout this textbook.

- Care Across the Life Span. Developmental stages are addressed regarding patient assessments and procedures.

- Health Promotion. Focused interview questions and patient education topics are included to promote patient well-being and encourage self-care behaviors.

- Scope of Practice. Assessment techniques are included that have been identified as frequently performed by entry-level nurse generalists.[11],[12],[13],[14]

- Patient Safety. Expected and unexpected findings on assessment are highlighted in tables to promote patient safety by encouraging notification of health care providers when changes in condition occur.

- Clear and Inclusive Language. Content is written using clear language preferred by entry-level pre-licensure nursing students to enhance understanding of complex concepts.[15] "They" is used as a singular pronoun to refer to a person whose gender is unknown or irrelevant to the context of the usage, as endorsed by APA style. It is inclusive of all people and helps writers avoid making assumptions about gender.[16]

- Open-Source Images and Fair Use. Images are included to promote visual learning. Students and faculty can reuse open-source images by following the terms of their associated Creative Commons licensing. Some images are included based on Fair Use as described in the "Code of Best Practices for Fair Use and Fair Dealing in Open Education" presented at the OpenEd20 conference. Refer to the footnotes of images for source and licensing information throughout the text.

- Open Pedagogy. Students are encouraged to contribute to the Open RN textbooks in meaningful ways. In this textbook, students assisted in reviewing content for clarity for an entry-level learner and also assisted in creating open-source images.[17]

Supplementary Material Provided

Several supplementary resources are provided with this textbook.

- Supplementary, free videos to promote student understanding of concepts and procedures

- Sample documentation for assessments and procedures

- Online learning activities with formative feedback

- Critical thinking questions that encourage application of content to patient scenarios and the development of clinical judgment

- Free downloadable versions for offline use

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

The patient reports no previous history of ear or eye conditions. Eyes have white sclera and pink conjunctiva with no drainage present. Corrected vision with glasses using Snellen chart is 20/20 bilaterally. Ear canals are clear bilaterally. Whispered voice test indicates effective hearing with the patient reporting five out six numbers correctly for both ears. Patient demonstrates good balance and coordinated gait.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

The patient reports awakening with an irritated left eye and crusty drainage with no change in vision. Sclera in the left eye is pink, conjunctiva is read and yellow crusty drainage present. Patient able to read the newspaper without visual impairment. Dr. Smith notified and evaluated patient at 1400. Order for antibiotic eyes drops received and administered. Patient and family members educated to wash hands frequently to avoid spreading infection.

Review for Eye Assessment on YouTube[18]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the '"Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 8, Assignment 1.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 8, Assignment 2.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the '"Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 8, Assignment 1.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 8, Assignment 2.

Acute otitis media: The medical diagnosis for a middle ear infection.

Auricle: The large, fleshy structure of the ear on the lateral aspect of the head.

Cerumen impaction: A buildup of earwax causing occlusion of the ear canal.

Conductive hearing loss: Hearing loss that occurs when something in the external or middle ear is obstructing the transmission of sound.

Conjunctiva: Inner surface of the eyelid.

Conjunctivitis: A viral or bacterial infection in the eye causing swelling and redness in the conjunctiva and sclera.

Cornea: The transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber.

Eustachian tube: The tube connecting the middle ear to the pharynx that helps equilibrate air pressure across the tympanic membrane.

Extraocular muscles: Six muscles that control the movement of the eye within the orbit. Extraocular muscles are innervated by three cranial nerves, the abducens nerve, the trochlear nerve, and the oculomotor nerve.

Iris: Colored part of the eye.

Lacrimal duct: Tears produced by the lacrimal gland flow through this duct to the medial corner of the eye.

Lens: An inner part of the eye that helps the eye focus.

Myopia: Impaired vision, also known as nearsightedness, that makes far-away objects look blurry.

Optic nerve: Cranial nerve II that conducts visual information from the retina to the brain.

Otitis externa: The medical diagnosis for external ear inflammation and/or infection.

Ototoxic medications: Medications that cause the adverse effect of sensorineural hearing loss by affecting the hair cells in the cochlea.

Presbycusis: Sensorineural hearing loss that occurs with aging due to gradual nerve degeneration.

Presbyopia: Impaired near vision that commonly occurs in middle-aged and older adults.

Pupil: The hole at the center of the eye that allows light to enter.

Retina: The nervous tissue and photoreceptors in the eye that initially process visual stimuli.

Sclera: White area of the eye.

Sensorineural hearing loss: Hearing loss caused by pathology of the inner ear, cranial nerve VIII, or auditory areas of the cerebral cortex.

Snellen chart: A chart used to test far vision.

Tinnitus: Ringing, buzzing, roaring, hissing, or whistling sound in the ears.

Tympanic membrane: The membrane at the end of the external ear canal, commonly called the eardrum, that vibrates after it is struck by sound waves.

Vertigo: A type of dizziness often described by patients as “the room feels as if it is spinning.”

Vestibulocochlear nerve: Cranial nerve VIII that transports neural signals from the cochlea and the vestibule to the brain stem regarding hearing and balance.

Acute otitis media: The medical diagnosis for a middle ear infection.

Auricle: The large, fleshy structure of the ear on the lateral aspect of the head.

Cerumen impaction: A buildup of earwax causing occlusion of the ear canal.

Conductive hearing loss: Hearing loss that occurs when something in the external or middle ear is obstructing the transmission of sound.

Conjunctiva: Inner surface of the eyelid.

Conjunctivitis: A viral or bacterial infection in the eye causing swelling and redness in the conjunctiva and sclera.

Cornea: The transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber.

Eustachian tube: The tube connecting the middle ear to the pharynx that helps equilibrate air pressure across the tympanic membrane.

Extraocular muscles: Six muscles that control the movement of the eye within the orbit. Extraocular muscles are innervated by three cranial nerves, the abducens nerve, the trochlear nerve, and the oculomotor nerve.

Iris: Colored part of the eye.

Lacrimal duct: Tears produced by the lacrimal gland flow through this duct to the medial corner of the eye.

Lens: An inner part of the eye that helps the eye focus.

Myopia: Impaired vision, also known as nearsightedness, that makes far-away objects look blurry.

Optic nerve: Cranial nerve II that conducts visual information from the retina to the brain.

Otitis externa: The medical diagnosis for external ear inflammation and/or infection.

Ototoxic medications: Medications that cause the adverse effect of sensorineural hearing loss by affecting the hair cells in the cochlea.

Presbycusis: Sensorineural hearing loss that occurs with aging due to gradual nerve degeneration.

Presbyopia: Impaired near vision that commonly occurs in middle-aged and older adults.

Pupil: The hole at the center of the eye that allows light to enter.

Retina: The nervous tissue and photoreceptors in the eye that initially process visual stimuli.

Sclera: White area of the eye.

Sensorineural hearing loss: Hearing loss caused by pathology of the inner ear, cranial nerve VIII, or auditory areas of the cerebral cortex.

Snellen chart: A chart used to test far vision.

Tinnitus: Ringing, buzzing, roaring, hissing, or whistling sound in the ears.

Tympanic membrane: The membrane at the end of the external ear canal, commonly called the eardrum, that vibrates after it is struck by sound waves.

Vertigo: A type of dizziness often described by patients as “the room feels as if it is spinning.”

Vestibulocochlear nerve: Cranial nerve VIII that transports neural signals from the cochlea and the vestibule to the brain stem regarding hearing and balance.

Learning Objectives

- Perform a cardiovascular assessment, including heart sounds; apical and peripheral pulses for rate, rhythm, and amplitude; and skin perfusion (color, temperature, sensation, and capillary refill time)

- Identify S1 and S2 heart sounds

- Differentiate between normal and abnormal heart sounds

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

The evaluation of the cardiovascular system includes a thorough medical history and a detailed examination of the heart and peripheral vascular system.[19] Nurses must incorporate subjective statements and objective findings to elicit clues of potential signs of dysfunction. Symptoms like fatigue, indigestion, and leg swelling may be benign or may indicate something more ominous. As a result, nurses must be vigilant when collecting comprehensive information to utilize their best clinical judgment when providing care for the patient.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completing an “Eye and Ear Assessment.”

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: penlight, Ishihara plates, Snellen chart, Rosenbaum card, or a newspaper to read.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Use effective interview questions to collect subjective data about eye or ear problems.

- Inspect the external eye. Note any unexpected findings.

- Assess that pupils are equally round and reactive to light and accommodation (PERRLA).

- Assess extraocular movement.

- Inspect the external ear. Note any unexpected findings.

- Assess distance vision acuity using the Snellen eye chart and proper technique.

- Assess near vision acuity using a prepared card or newspaper.

- Asses for color blindness using the Ishihara plates.

- Assess hearing by accurately performing the whisper test.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

While the cardiovascular assessment most often focuses on the function of the heart, it is important for nurses to have an understanding of the underlying structures of the cardiovascular system to best understand the meaning of their assessment findings.

For more information on the cardiovascular system, visit the "Cardiovascular and Renal System" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Specific sections include the following topics:

- Review of Basic Concepts for more about the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system

- Common Cardiac Disorders for more about cardiovascular medical conditions

- Cardiovascular and Renal System Medications for more about medications used to treat common cardiovascular conditions

Review of Anatomy and Physiology of the Heart on YouTube[20]

While the cardiovascular assessment most often focuses on the function of the heart, it is important for nurses to have an understanding of the underlying structures of the cardiovascular system to best understand the meaning of their assessment findings.

For more information on the cardiovascular system, visit the "Cardiovascular and Renal System" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Specific sections include the following topics:

- Review of Basic Concepts for more about the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system

- Common Cardiac Disorders for more about cardiovascular medical conditions

- Cardiovascular and Renal System Medications for more about medications used to treat common cardiovascular conditions

Review of Anatomy and Physiology of the Heart on YouTube[21]

National standards of care and treatment processes for common conditions. These processes are proven to reduce complications and lead to better patient outcomes.

Guidelines specific to organizations accredited by The Joint Commission that focus on problems in health care safety and ways to solve them.

A thorough assessment of the heart provides valuable information about the function of a patient’s cardiovascular system. Understanding how to properly assess the cardiovascular system and identifying both normal and abnormal assessment findings will allow the nurse to provide quality, safe care to the patient.

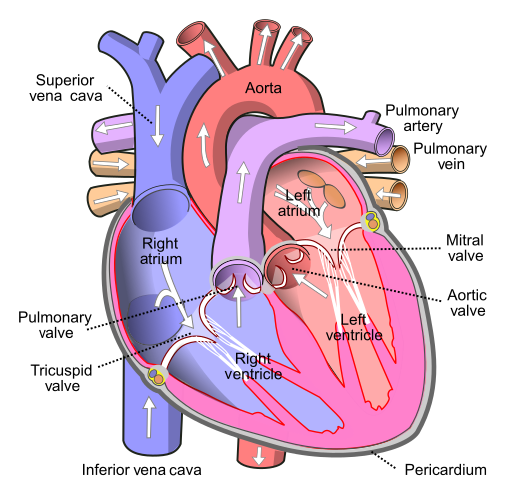

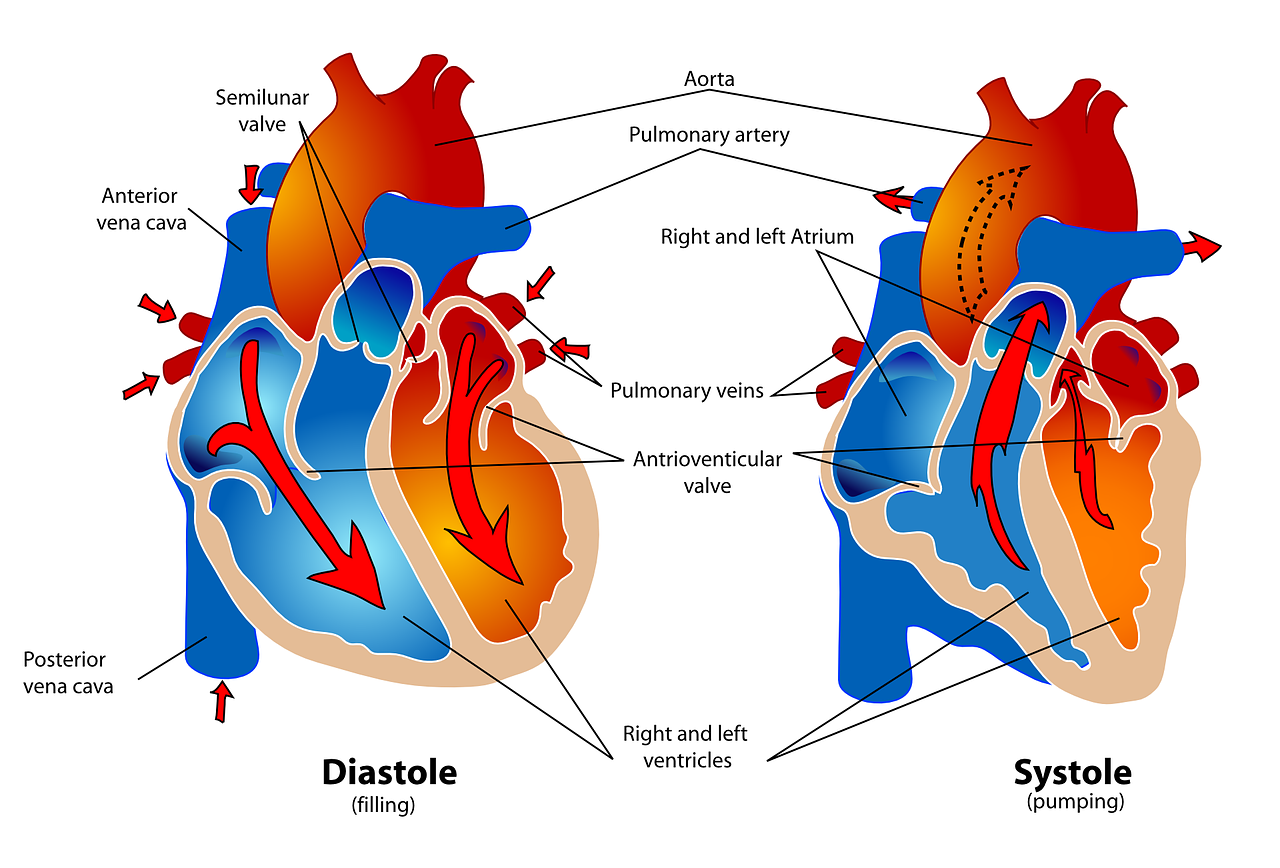

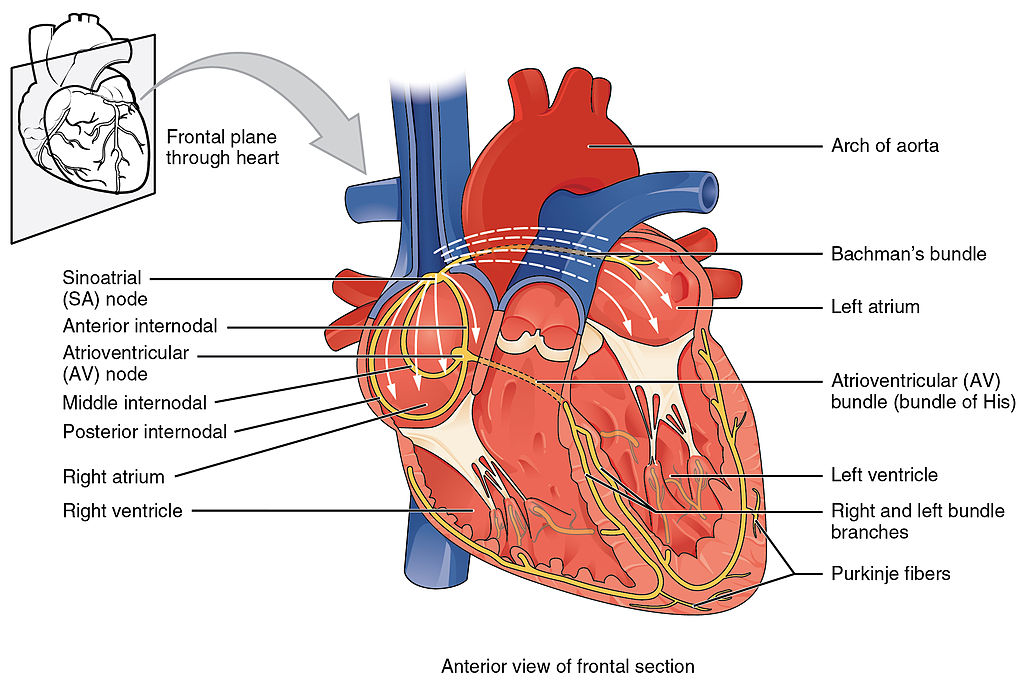

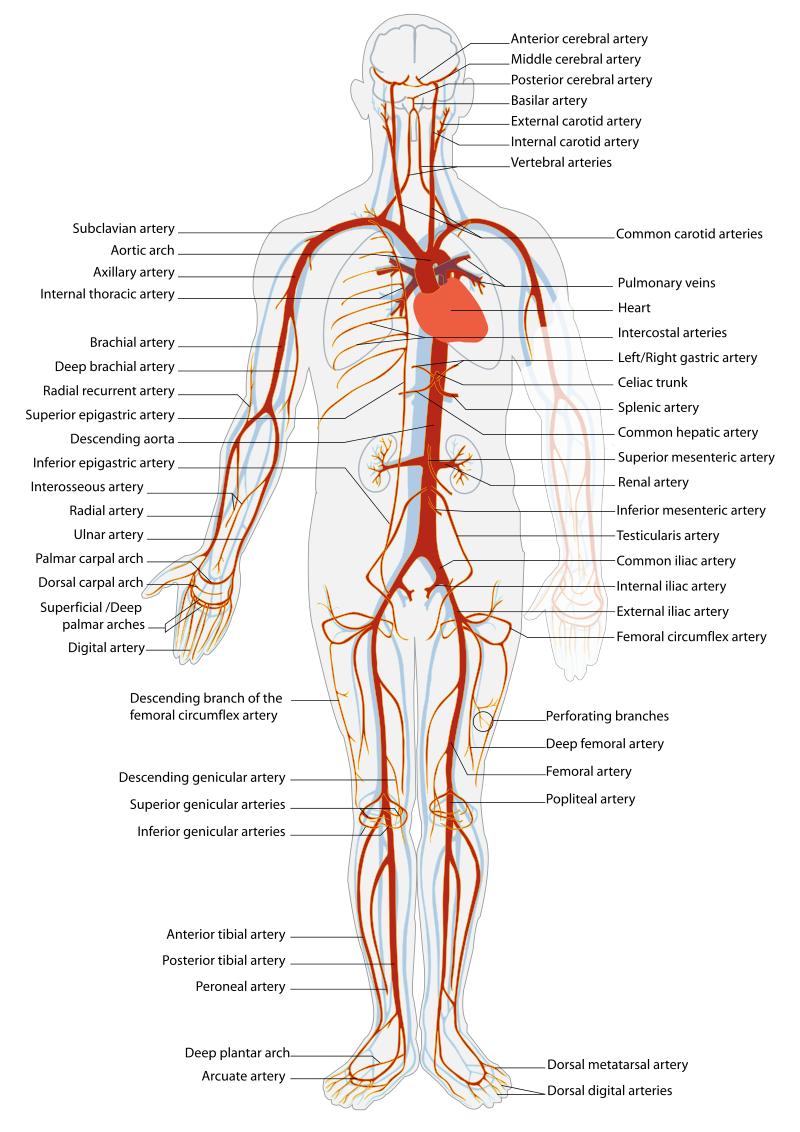

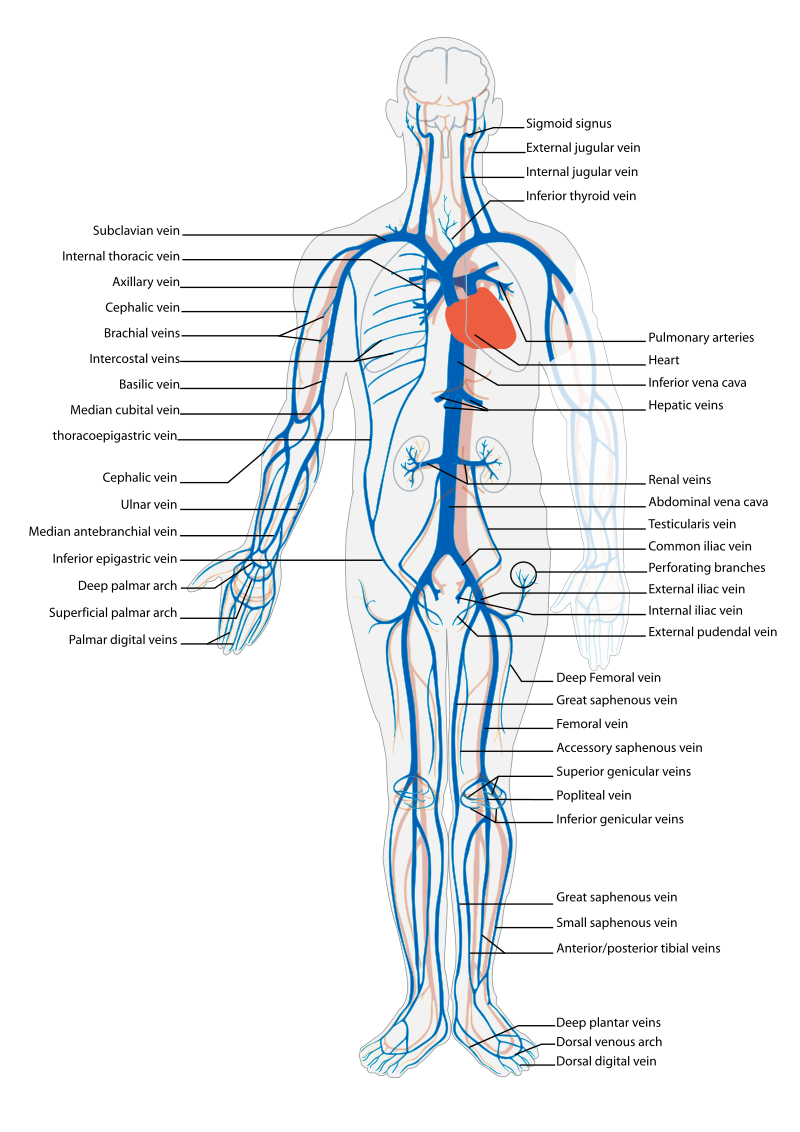

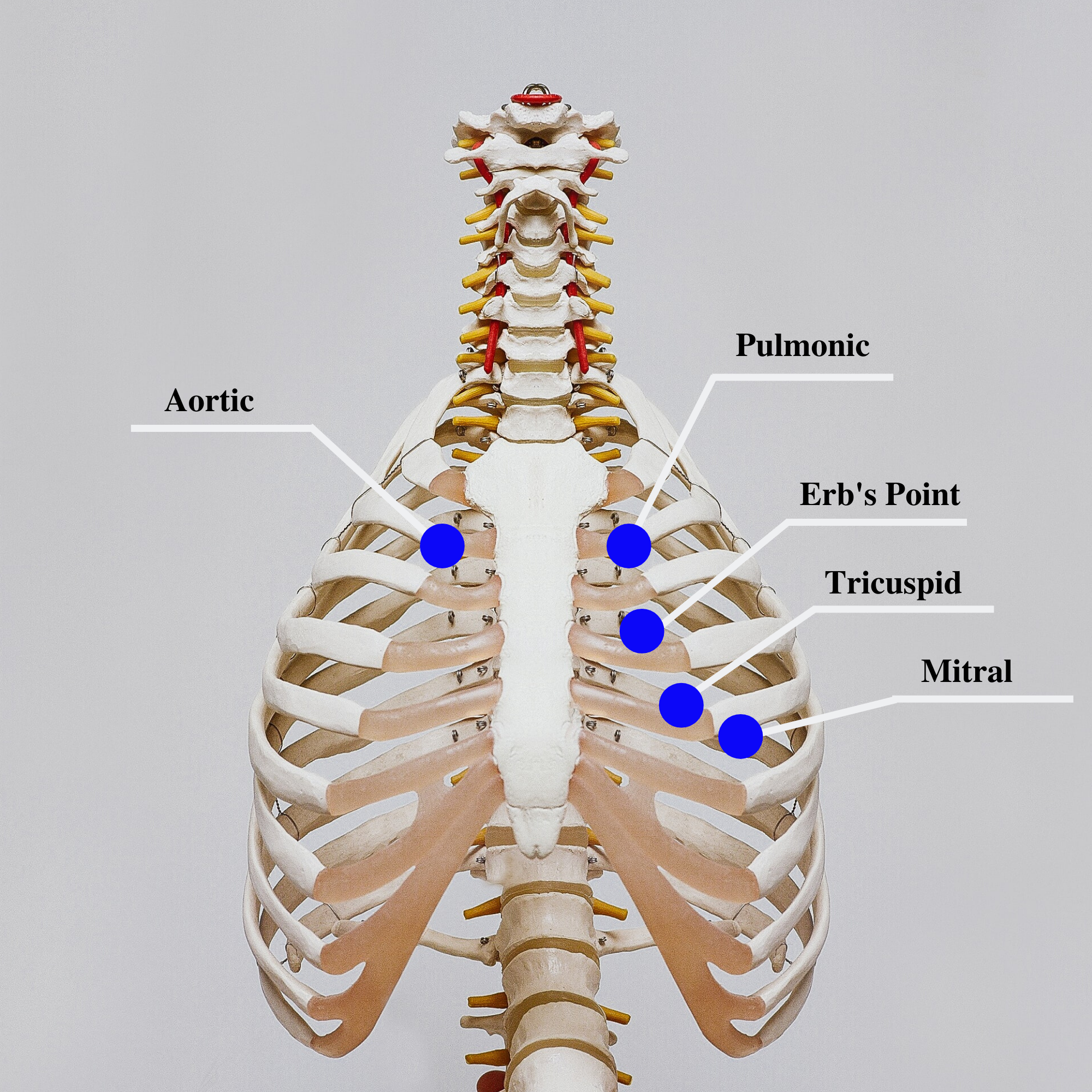

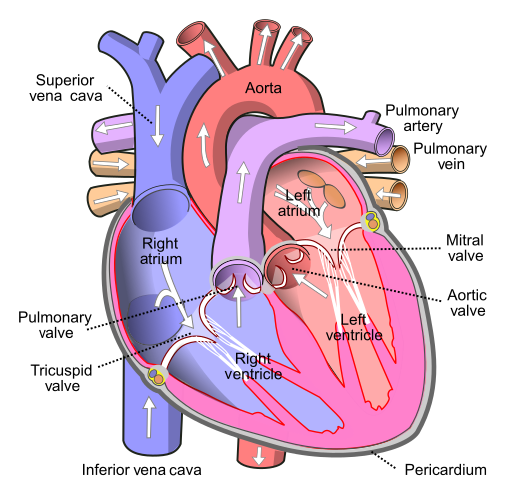

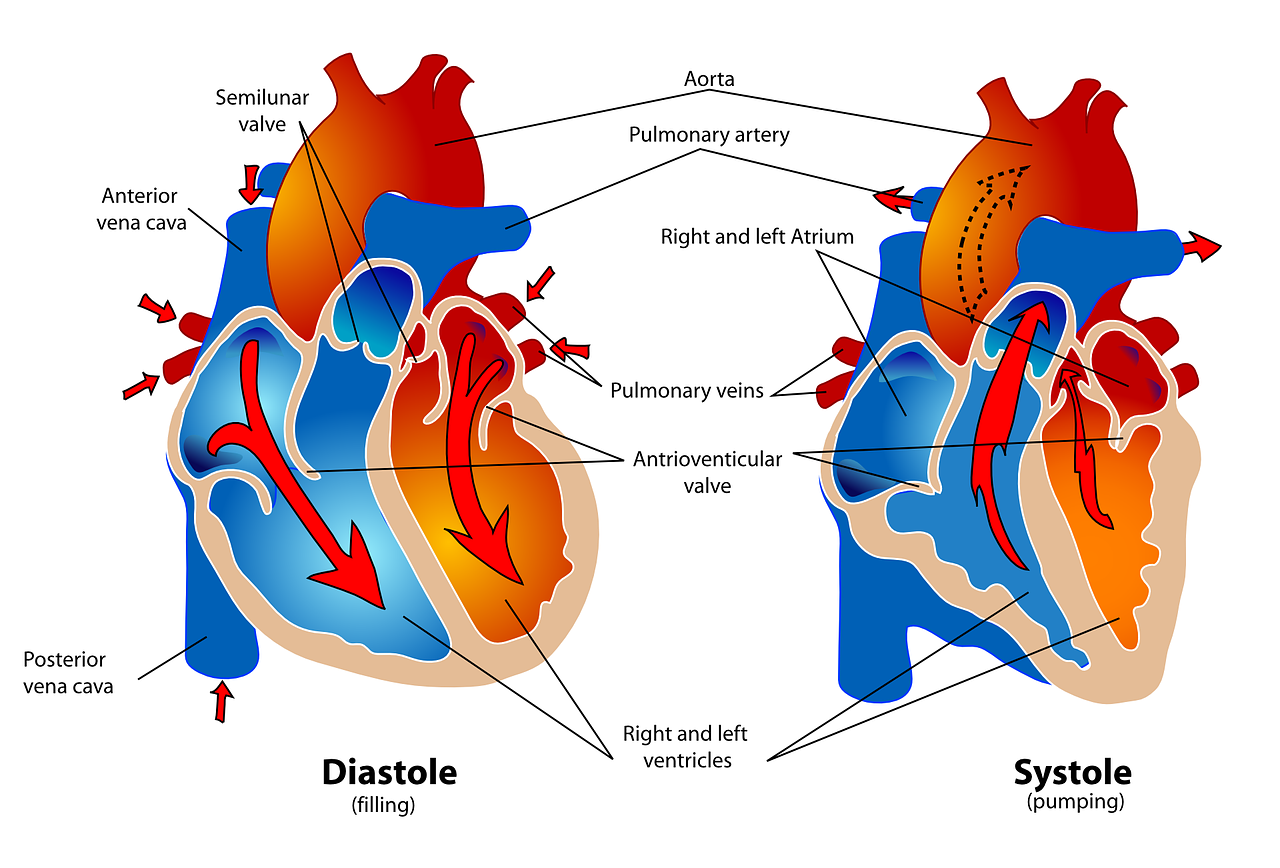

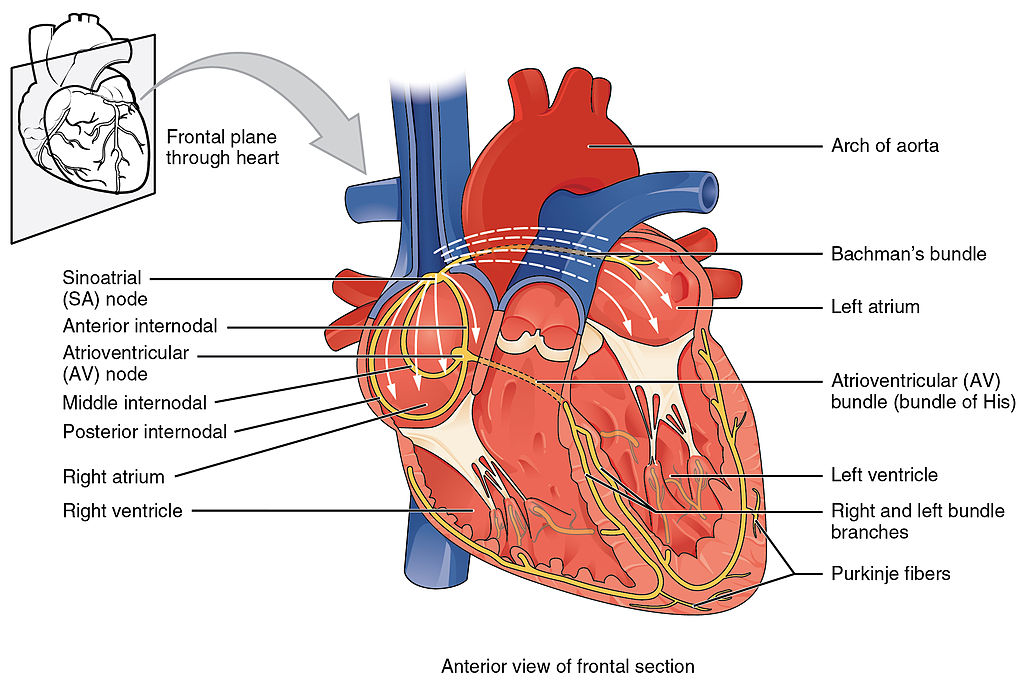

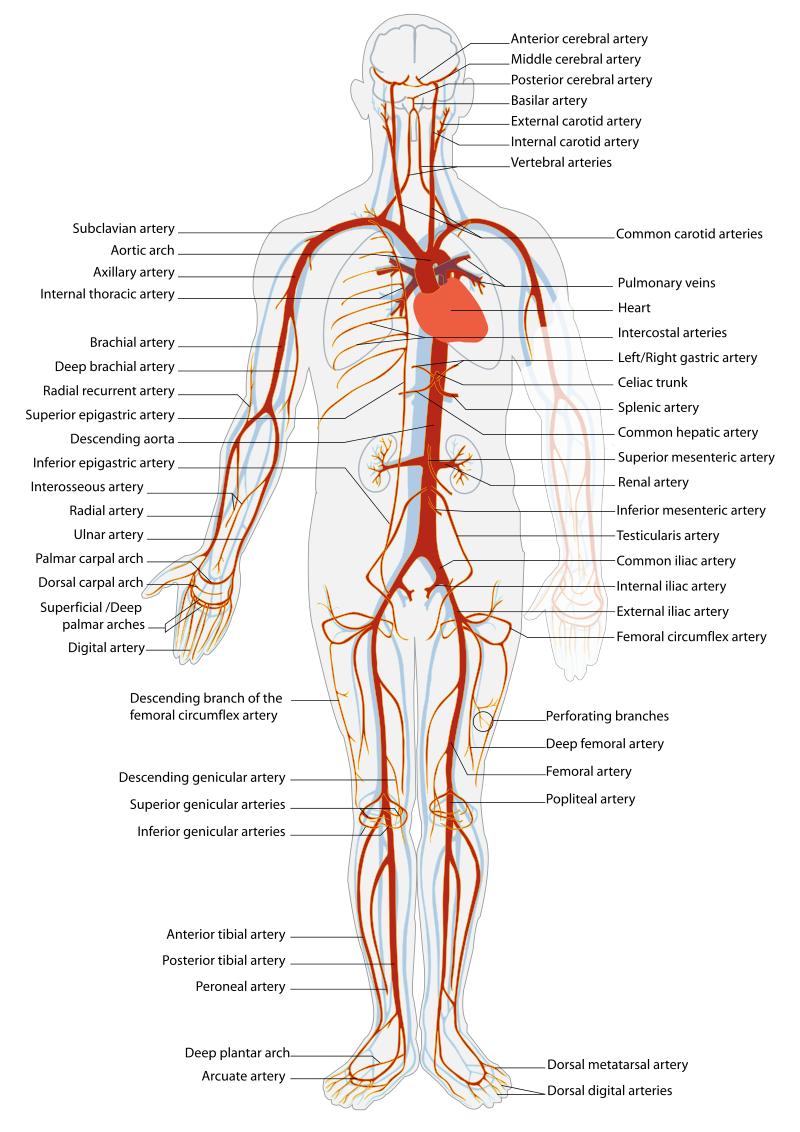

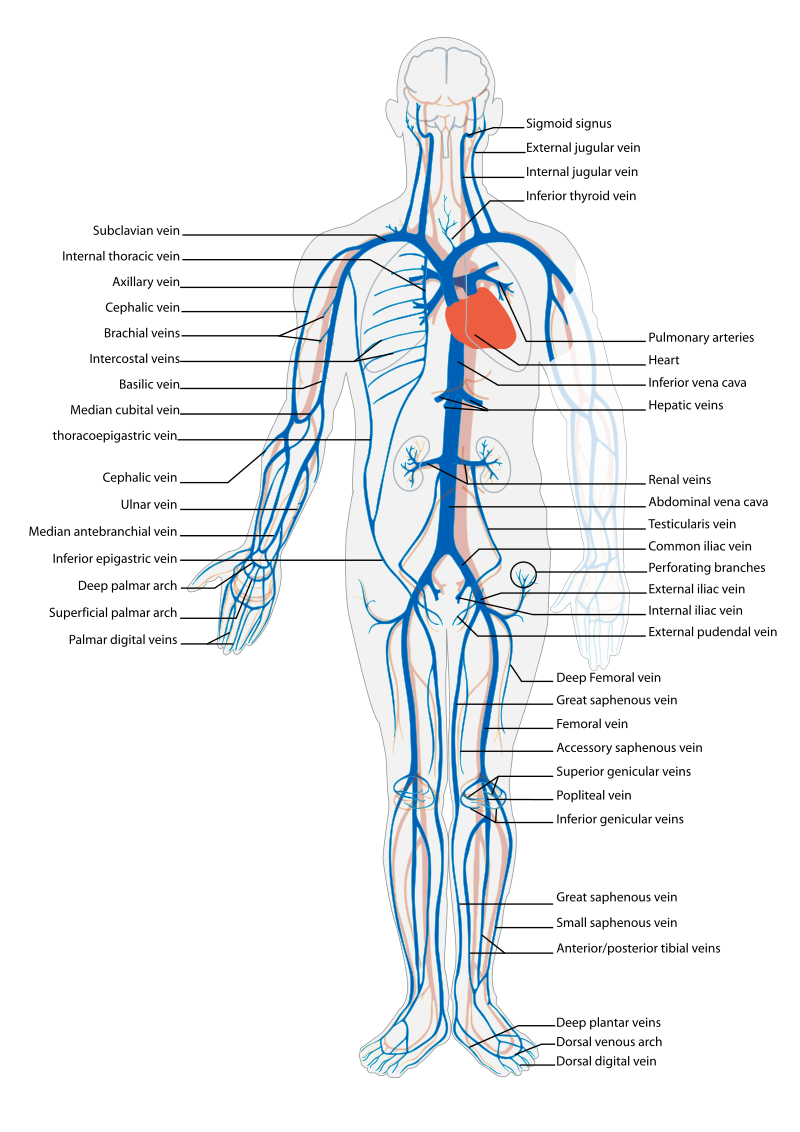

Before assessing a patient’s cardiovascular system, it is important to understand the various functions of the cardiovascular system. In addition to the information provided in the “Review of Cardiac Basics” section, the following images provide an overview of the cardiovascular system. Figure 9.1[22] provides an overview of the structure of the heart. Note the main cardiac structures are the atria, ventricles, and heart valves. Figure 9.2[23] demonstrates blood flow through the heart. Notice the flow of deoxygenated blood from the posterior and superior vena cava into the right atria and ventricle during diastole (indicated by blue coloring of these structures). The right ventricle then pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs via the pulmonary artery during systole. At the same time, oxygenated blood from the lungs returns to the left atria and ventricle via the pulmonary veins during diastole (indicated by red coloring of these structures) and then is pumped out to the body via the aorta during systole. Figure 9.3[24] demonstrates the conduction system of the heart. This image depicts the conduction pathway through the heart as the tissue responds to electrical stimulation. Figure 9.4[25] illustrates the arteries of the circulatory system, and Figure 9.5[26] depicts the veins of the circulatory system. The purpose of these figures is to facilitate understanding of the electrical and mechanical function of the heart within the cardiovascular system.

Assessing the cardiovascular system includes performing several subjective and objective assessments. At times, assessment findings are modified according to life span considerations.

Subjective Assessment

The subjective assessment of the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular system is vital for uncovering signs of potential dysfunction. To complete the subjective cardiovascular assessment, the nurse begins with a focused interview. The focused interview explores past medical and family history, medications, cardiac risk factors, and reported symptoms. Symptoms related to the cardiovascular system include chest pain, peripheral edema, unexplained sudden weight gain, shortness of breath (dyspnea), irregular pulse rate or rhythm, dizziness, or poor peripheral circulation. Any new or worsening symptoms should be documented and reported to the health care provider.

Table 9.3a outlines questions used to assess symptoms related to the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular systems. Table 9.3b outlines questions used to assess medical history, medications, and risk factors related to the cardiovascular system. Information obtained from the interview process is used to tailor future patient education by the nurse.[27],[28],[29]

Table 9.3a Interview Questions for Cardiovascular and Peripheral Vascular Systems[30]

| Symptom | Question |

Follow-Up Safety Note: If findings indicate current severe symptoms suggestive of myocardial infarction or another critical condition, suspend the remaining cardiovascular assessment and obtain immediate assistance according to agency policy or call 911. |

|---|---|---|

| Chest Pain | Have you had any pain or pressure in your chest, neck, or arm? | Review how to assess a patient's chief complaint using the PQRSTU method in the "Health History" chapter.

|

| Shortness of Breath

(Dyspnea) |

Do you ever feel short of breath with activity?

Do you ever feel short of breath at rest? Do you feel short of breath when lying flat? |

What level of activity elicits shortness of breath?

How long does it take you to recover? Have you ever woken up from sleeping feeling suddenly short of breath How many pillows do you need to sleep, or do you sleep in a chair (orthopnea)? Has this recently changed? |

| Edema | Have you noticed swelling of your feet or ankles?

Have you noticed your rings, shoes, or clothing feel tight at the end of the day? Have you noticed any unexplained, sudden weight gain? Have you noticed any new abdominal fullness? |

Has this feeling of swelling or restriction gotten worse?

Is there anything that makes the swelling better (e.g., sitting with your feet elevated)? How much weight have you gained? Over what time period have you gained this weight? |

| Palpitations | Have you ever noticed your heart feels as if it is racing or “fluttering” in your chest?

Have you ever felt as if your heart “skips” a beat? |

Are you currently experiencing palpitations?

When did palpitations start? Have you previously been treated for palpitations? If so, what treatment did you receive? |

| Dizziness (Syncope) |

Do you ever feel light-headed?

Do you ever feel dizzy? Have you ever fainted? |

Can you describe what happened?

Did you have any warning signs? Did this occur with position change? |

| Poor Peripheral Circulation | Do your hands or feet ever feel cold or look pale or bluish?

Do you have pain in your feet or lower legs when exercising? |

What, if anything, brings on these symptoms?

How much activity is needed to cause this pain? Is there anything, such as rest, that makes the pain better? |

| Calf Pain | Do you currently have any constant pain in your lower legs? | Can you point to the area of pain with one finger? |

Table 9.3b Interview Questions Exploring Cardiovascular Medical History, Medications, and Cardiac Risk Factors

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Medical History | Have you ever been diagnosed with any heart or circulation conditions, such as high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, high cholesterol, heart failure, or valve problems?

Have you had any procedures done to improve your heart function, such as ablation or stent placement? Have you ever had a heart attack or stroke? |

| Medications | Do you take any heart-related medications, herbs, or supplements to treat blood pressure, chest pain, high cholesterol, cardiac rhythm, fluid retention, or the prevention of clots? |

| Cardiac Risk Factors | Have your parents or siblings been diagnosed with any heart conditions?

Do you smoke or vape?

If you do not currently smoke, have you smoked in the past?

Are you physically active during the week?

What does a typical day look like in your diet?

Do you drink alcoholic drinks?

Would you say you experience stress in your life?

How many hours of sleep do you normally get each day?

|

Objective Assessment

The physical examination of the cardiovascular system involves the interpretation of vital signs, inspection, palpation, and auscultation of heart sounds as the nurse evaluates for sufficient perfusion and cardiac output.

For more information about assessing a patient's oxygenation status as it relates to their cardiac output, visit the "Oxygenation" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Equipment needed for a cardiovascular assessment includes a stethoscope, penlight, centimeter ruler or tape measure, and sphygmomanometer.[31]

Evaluate Vital Signs and Level of Consciousness

Interpret the blood pressure and pulse readings to verify the patient is stable before proceeding with the physical exam. Assess the level of consciousness; the patient should be alert and cooperative.

Inspection

- Skin color to assess perfusion. Inspect the face, lips, and fingertips for cyanosis or pallor. Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds and indicates decreased perfusion and oxygenation. Pallor is the loss of color, or paleness of the skin or mucous membranes, as a result of reduced blood flow, oxygenation, or decreased number of red blood cells. Patients with light skin tones should be pink in color. For those with darker skin tones, assess for pallor on the palms, conjunctiva, or inner aspect of the lower lip.

- Jugular Vein Distension (JVD). Inspect the neck for JVD that occurs when the increased pressure of the superior vena cava causes the jugular vein to bulge, making it most visible on the right side of a person's neck. JVD should not be present in the upright position or when the head of bed is at 30-45 degrees.

- Precordium for abnormalities. Inspect the chest area over the heart (also called precordium) for deformities, scars, or any abnormal pulsations the underlying cardiac chambers and great vessels may produce.

- Extremities:

- Upper Extremities: Inspect the fingers, arms, and hands bilaterally noting Color, Warmth, Movement, Sensation (CWMS). Alterations or bilateral inconsistency in CWMS may indicate underlying conditions or injury. Assess capillary refill by compressing the nail bed until it blanches and record the time taken for the color to return to the nail bed. Normal capillary refill is less than 3 seconds.[32]

- Lower Extremities: Inspect the toes, feet, and legs bilaterally, noting CWMS, capillary refill, and the presence of peripheral edema, superficial distended veins, and hair distribution. Document the location and size of any skin ulcers.

- Edema: Note any presence of edema. Peripheral edema is swelling that can be caused by infection, thrombosis, or venous insufficiency due to an accumulation of fluid in the tissues. (See Figure 9.6[33] for an image of pedal edema.)[34]

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): A deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot that forms in a vein deep in the body. DVT requires emergency notification of the health care provider and immediate follow-up because of the risk of developing a life-threatening pulmonary embolism.[35] Inspect the lower extremities bilaterally. Assess for size, color, temperature, and for presence of pain in the calves. Unilateral warmth, redness, tenderness, swelling in the calf, or sudden onset of intense, sharp muscle pain that increases with dorsiflexion of the foot is an indication of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT).[36] See Figure 9.7[37] for an image of a DVT in the patient's right leg, indicated by unilateral redness and edema.

Auscultation

Heart Sounds

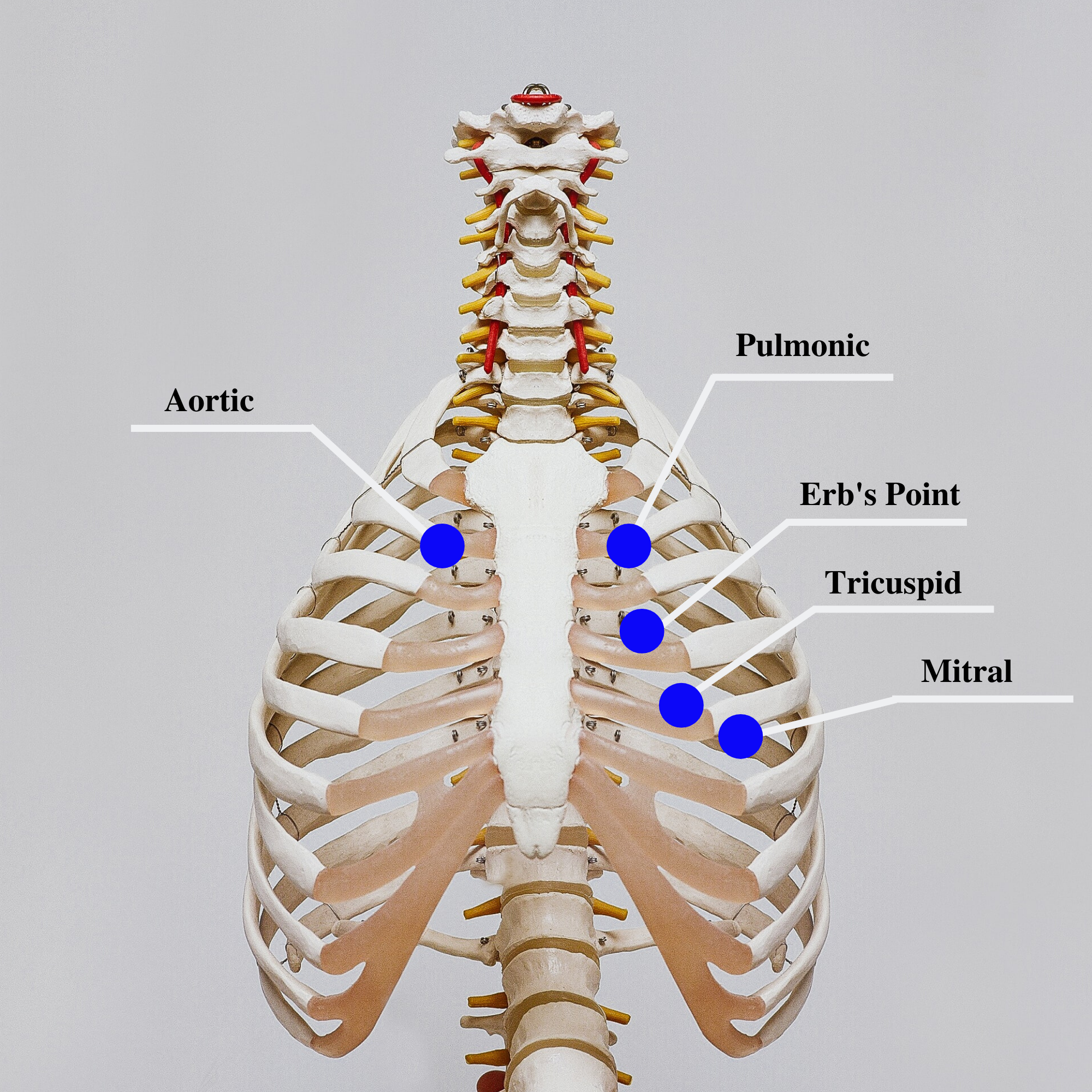

Auscultation is routinely performed over five specific areas of the heart to listen for corresponding valvular sounds. These auscultation sites are often referred to by the mnemonic “APE To Man,” referring to Aortic, Pulmonic, Erb’s point, Tricuspid, and Mitral areas (see Figure 9.8[38] for an illustration of cardiac auscultation areas). The aortic area is the second intercostal space to the right of the sternum. The pulmonic area is the second intercostal space to the left of the sternum. Erb's point is directly below the pulmonic area and located at the third intercostal space to the left of the sternum. The tricuspid (or parasternal) area is at the fourth intercostal space to the left of the sternum. The mitral (also called apical or left ventricular area) is the fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line.

Auscultation usually begins at the aortic area (upper right sternal edge). Use the diaphragm of the stethoscope to carefully identify the S1 and S2 sounds. They will make a “lub-dub” sound. Note that when listening over the area of the aortic and pulmonic valves, the "dub" (S2) will sound louder than the "lub" (S1). Move the stethoscope sequentially to the pulmonic area (upper left sternal edge), Erb’s point (left third intercostal space at the sternal border), and tricuspid area (fourth intercostal space. When assessing the mitral area for female patients, it is often helpful to ask them to lift up their breast tissue so the stethoscope can be placed directly on the chest wall. Repeat this process with the bell of the stethoscope. The apical pulse should be counted over a 60-second period. For an adult, the heart rate should be between 60 and 100 with a regular rhythm to be considered within normal range. The apical pulse is an important assessment to obtain before the administration of many cardiac medications.

The first heart sound (S1) identifies the onset of systole, when the atrioventricular (AV) valves (mitral and tricuspid) close and the ventricles contract and eject the blood out of the heart. The second heart sound (S2) identifies the end of systole and the onset of diastole when the semilunar valves close, the AV valves open, and the ventricles fill with blood. S1 corresponds to the palpable pulse. When auscultating, it is important to identify the S1 ("lub") and S2 ("dub") sounds, evaluate the rate and rhythm of the heart, and listen for any extra heart sounds.

![]() Auscultating Heart Sounds

Auscultating Heart Sounds

- To effectively auscultate heart sounds, patient repositioning may be required. If it difficult to hear the heart sounds, ask the patient to lean forward if they are able, or lie on their left side. These positions move the heart closer to their chest wall and can increase the volume of the heart sounds heard on auscultation. This repositioning may be helpful in patients with increased adipose tissue in their chest wall or larger breasts.

- It is common to hear lung sounds when auscultating the heart sounds. It may be helpful to ask the patient to briefly hold their breath if lung sounds impede adequate heart auscultation. Limit the holding of breath to 10 seconds or as tolerated by the patient.

- Environmental noise can cause difficulty in auscultating heart sounds. Removing environmental noise by turning down the television volume or shutting the door may be required for an accurate assessment.

- Patients may try to talk to you as you are assessing their heart sounds. It is often helpful to explain the procedure such as, “I am going to take a few minutes to listen carefully to the sounds of blood flow going through your heart. Please try not to speak while I am listening, so I can hear the sounds better.”

Extra Heart Sounds

Extra heart sounds include clicks, murmurs, S3 and S4 sounds, and pleural friction rubs. These extra sounds can be difficult for a novice to distinguish, so if you notice any new or different sounds, consult an advanced practitioner or notify the provider. A midsystolic click, associated with mitral valve prolapse, may be heard with the diaphragm at the apex or left lower sternal border.

A click may be followed by a murmur. A murmur is a blowing or whooshing sound that signifies turbulent blood flow often caused by a valvular defect. New murmurs not previously recorded should be immediately communicated to the health care provider. In the aortic area, listen for possible murmurs of aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation with the diaphragm of the stethoscope. In the pulmonic area, listen for potential murmurs of pulmonic stenosis and pulmonary and aortic regurgitation. In the tricuspid area, at the fourth and fifth intercostal spaces along the left sternal border, listen for the potential murmurs of tricuspid regurgitation, tricuspid stenosis, or ventricular septal defect.

S3 and S4 sounds, if present, are often heard best by asking the patient to lie on their left side and listening over the apex with the bell of the stethoscope. An S3 sound, also called a ventricular gallop, occurs after the S2 and sounds like “lub-dub-dah,” or a sound similar to a horse galloping. An S3 can occur when a patient is experiencing fluid overload, such as during an acute exacerbation of heart failure.[39] It can also be a normal finding in pregnancy due to increased blood flow through the ventricles.

The S4 sound, also called atrial gallop, occurs immediately before the S1 and sounds like “ta-lub-dub.” An S4 sound can occur with decreased ventricular compliance or coronary artery disease.[40]

A pericardial friction rub is caused by inflammation of the pericardium, with a creaky-scratchy noise generated as the parietal and visceral membranes rub together. It is best heard at the apex or left lower sternal border with the diaphragm as the patient sits up, leans forward, and holds their breath.

Carotid Sounds

The carotid artery may be auscultated for bruits. Bruits are a swishing sound due to turbulence in the blood vessel and may be heard due to atherosclerotic changes.

Palpation

Palpation is used to evaluate peripheral pulses, capillary refill, and for the presence of edema. When palpating these areas, also pay attention to the temperature and moisture of the skin.

Pulses

Compare the rate, rhythm, and quality of arterial pulses bilaterally, including the carotid, radial, brachial, posterior tibialis, and dorsalis pedis pulses. Review additional information about obtaining pulses in the "General Survey" chapter. Bilateral comparison for all pulses (except the carotid) is important for determining subtle variations in pulse strength. Carotid pulses should be palpated on one side at a time to avoid decreasing perfusion of the brain. The posterior tibial artery is located just behind the medial malleolus. It can be palpated by scooping the patient's heel in your hand and wrapping your fingers around so that the tips come to rest on the appropriate area just below the medial malleolus. The dorsalis pedis artery is located just lateral to the extensor tendon of the big toe and can be identified by asking the patient to flex their toe while you provide resistance to this movement. Gently place the tips of your second, third, and fourth fingers adjacent to the tendon, and try to feel the pulse.

The quality of the pulse is graded on a scale of 0 to 3, with 0 being absent pulses, 1 being decreased pulses, 2 is within normal range, and 3 being increased (also referred to as "bounding”). If unable to palpate a pulse, additional assessment is needed. First, determine if this is a new or chronic finding. Second, if available, use a Doppler ultrasound to determine the presence or absence of the pulse. Many agencies use Doppler ultrasound to document if a nonpalpable pulse is present. If the pulse is not found, this could be a sign of an emergent condition requiring immediate follow-up and provider notification. See Figures 9.9[41] and 9.10[42] for images of assessing pedal pulses.

Capillary Refill

The capillary refill test is performed on the nail beds to monitor perfusion, the amount of blood flow to tissue. Pressure is applied to a fingernail or toenail until it pales, indicating that the blood has been forced from the tissue under the nail. This paleness is called blanching. Once the tissue has blanched, pressure is removed. Capillary refill time is defined as the time it takes for the color to return after pressure is removed. If there is sufficient blood flow to the area, a pink color should return within 2 seconds after the pressure is removed.[43]

Review of Capillary Refill Test on YouTube[44].

Edema

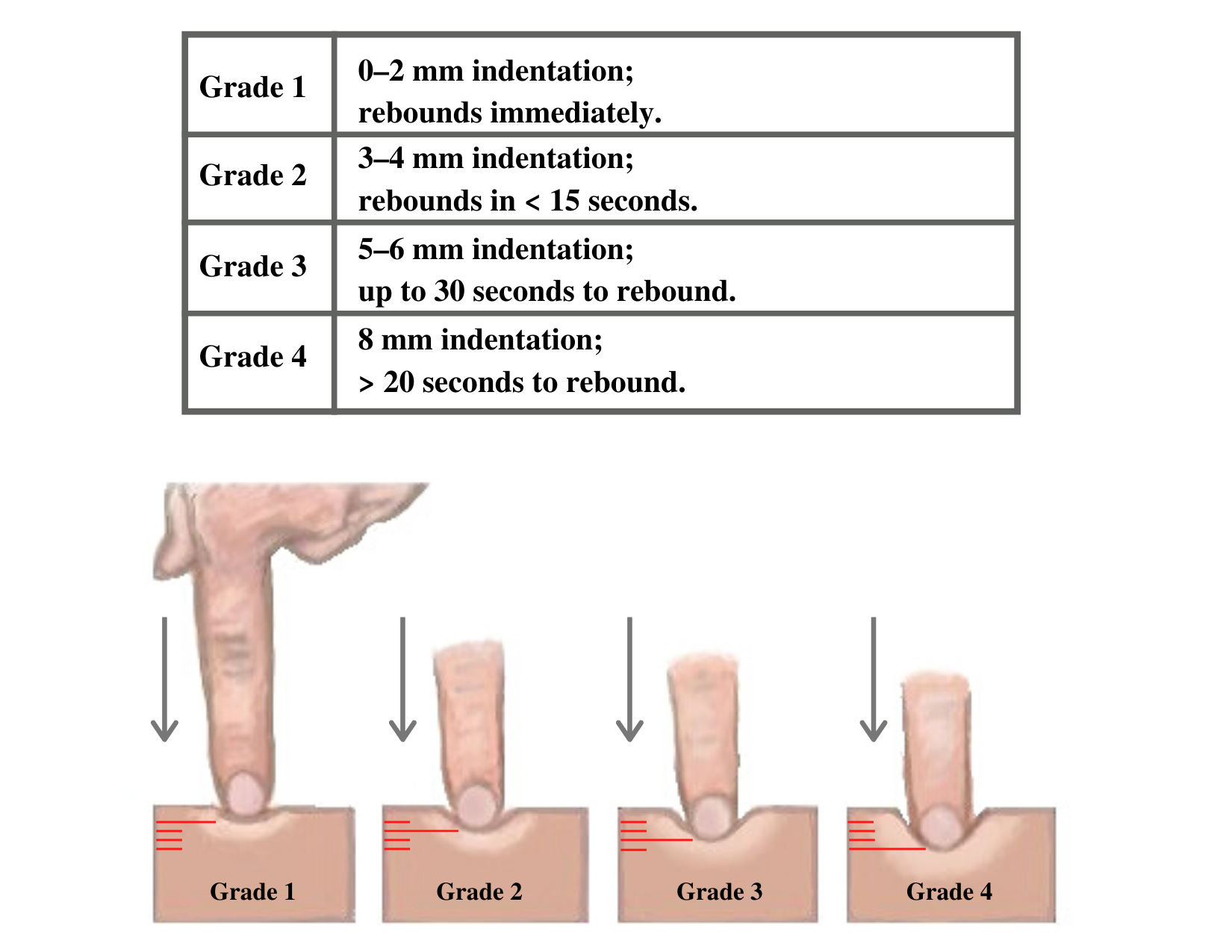

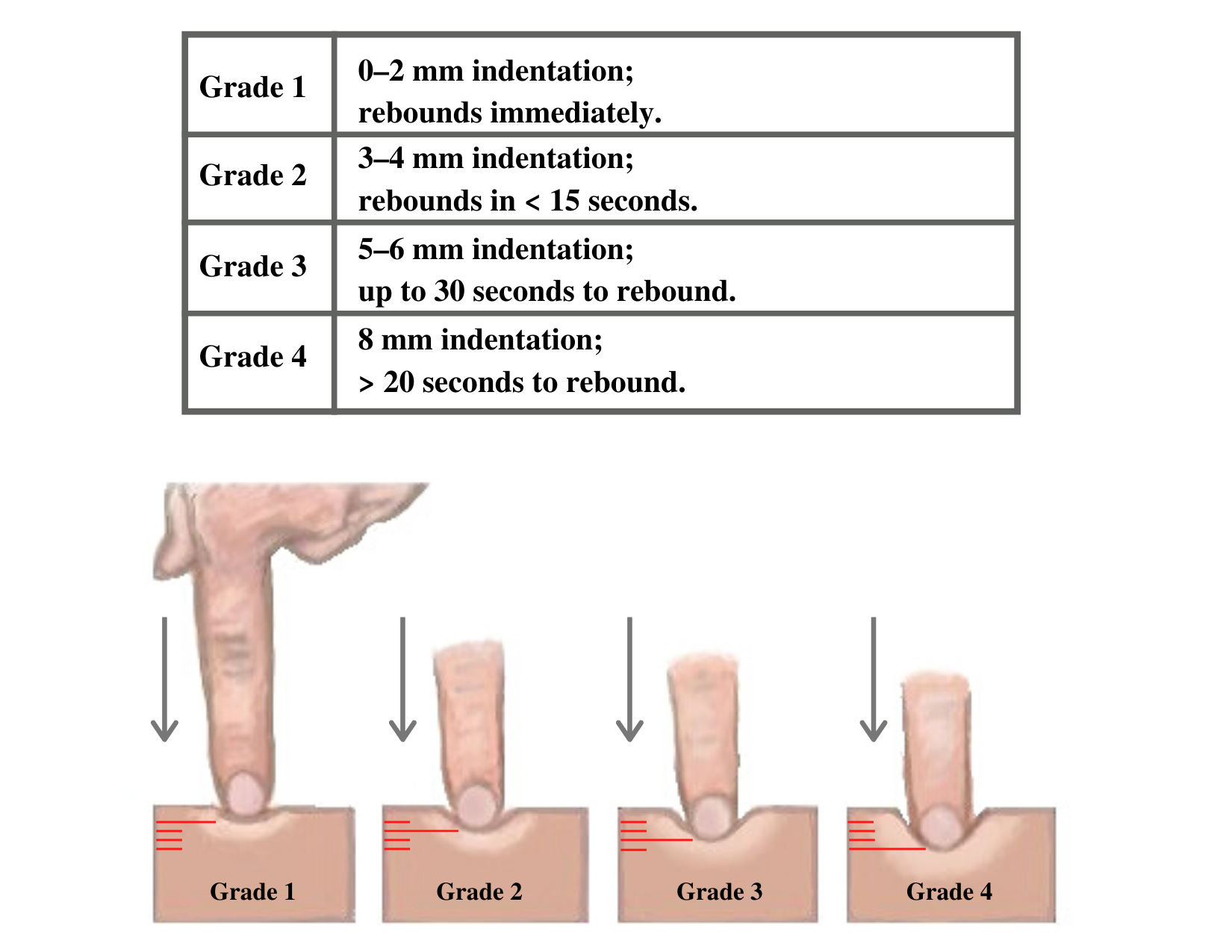

Edema occurs when one can visualize visible swelling caused by a buildup of fluid within the tissues. If edema is present on inspection, palpate the area to determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting. Press on the skin to assess for indentation, ideally over a bony structure, such as the tibia. If no indentation occurs, it is referred to as nonpitting edema. If indentation occurs, it is referred to as pitting edema. See Figure 9.11[45] for images demonstrating pitting edema.

Note the depth of the indention and how long it takes for the skin to rebound back to its original position. The indentation and time required to rebound to the original position are graded on a scale from 1 to 4. Edema rated at 1+ indicates a barely detectable depression with immediate rebound, and 4+ indicates a deep depression with a time lapse of over 20 seconds required to rebound. See Figure 9.12[46] for an illustration of grading edema. Additionally, it is helpful to note edema may be difficult to observe in larger patients. It is also important to monitor for sudden changes in weight, which is considered a probable sign of fluid volume overload.

Heaves or Thrills

You may observe advanced practice nurses and other health care providers palpating the anterior chest wall to detect any abnormal pulsations the underlying cardiac chambers and great vessels may produce. Precordial movements should be evaluated at the apex (mitral area). It is best to examine the precordium with the patient supine because if the patient is turned on the left side, the apical region of the heart is displaced against the lateral chest wall, distorting the chest movements.[47] A heave or lift is a palpable lifting sensation under the sternum and anterior chest wall to the left of the sternum that suggests severe right ventricular hypertrophy. A thrill is a vibration felt on the skin of the precordium or over an area of turbulence, such as an arteriovenous fistula or graft.

Life Span Considerations

The cardiovascular assessment and expected findings should be modified according to common variations across the life span.

Infants and Children

A murmur may be heard in a newborn in the first few days of life until the ductus arteriosus closes.

When assessing the cardiovascular system in children, it is important to assess the apical pulse. Parameters for expected findings vary according to age group. After a child reaches adolescence, a radial pulse may be assessed. Table 9.3c outlines the expected apical pulse rate by age.

Table 9.3c Expected Apical Pulse by Age

| Age Group | Heart Rate |

|---|---|

| Preterm | 120-180 |

| Newborn (0 to 1 month) | 100-160 |

| Infant (1 to 12 months) | 80-140 |

| Toddler (1 to 3 years) | 80-130 |

| Preschool (3 to 5 years) | 80-110 |

| School Age (6 to 12 years) | 70-100 |

| Adolescents (13 to 18 years) | 60-90 |

Older Adults

In adults over age 65, irregular heart rhythms and extra sounds are more likely. An "irregularly irregular" rhythm suggests atrial fibrillation, and further investigation is required if this is a new finding. See the box below for more information about atrial fibrillation.

For more information on atrial fibrillation, visit the CDC Atrial Fibrillation webpage.

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

After completing a cardiovascular assessment, it is important for the nurse to use critical thinking to determine if any findings require follow-up. Depending on the urgency of the findings, follow-up can range from calling the health care provider to calling the rapid response team. Table 9.3d compares examples of expected findings, meaning those considered within normal limits, to unexpected findings, which require follow-up. Critical conditions are those that should be reported immediately and may require notification of a rapid response team.

Table 9.3d Expected Versus Unexpected Findings on Cardiac Assessment

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify the provider if this is a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Apical impulse may or may not be visible | Scars not previously documented that could indicate prior cardiac surgeries

Heave or lift observed in the precordium Chest anatomy malformations |

| Palpation | Apical pulse felt over midclavicular fifth intercostal space | Apical pulse felt to the left of the midclavicular fifth intercostal space

Additional movements over precordium such as a heave, lift, or thrill |

| Auscultation | S1 and S2 heart sounds in a regular rhythm | New irregular heart rhythm

Extra heart sounds such as a murmur, S3, or S4 |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Symptomatic tachycardia at rest (HR>100 bpm)

Symptomatic bradycardia (HR<60 bpm) New systolic blood pressure (<100 mmHg) Orthostatic blood pressure changes (see “Blood Pressure” chapter for more information) New irregular heart rhythm New extra heart sounds such as a murmur, S3, or S4 New abnormal cardiac rhythm changes Reported chest pain, calf pain, or worsening shortness of breath |

See Table 9.3e for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the peripheral vascular system.

Table 9.3e Expected Versus Unexpected Peripheral Vascular Assessment Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document or notify provider if new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Skin color uniform and appropriate for race bilaterally

Equal hair distribution on upper and lower extremities Absence of jugular vein distention (JVD) Absence of edema Sensation and movement of fingers and toes intact |

Cyanosis or pallor, indicating decreased perfusion