11.11 Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic disorder that is characterized by inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. IBD is an umbrella term used to describe two disorders called ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. In ulcerative colitis (UC), this inflammation is limited to the two layers of the colon, the mucosa and submucosa, most commonly in the rectum. In Crohn’s disease (CD), inflammation can occur anywhere in the GI tract, from the mouth to the anus, and the inflammation affects all three layers of the colon. With both disorders, signs and symptoms can also occur outside the GI tract, commonly referred to as extraintestinal manifestations. Neither ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease can be cured, and both disorders carry an increased risk for cancer of the GI tract.[1],[2],[3]

Both UC and CD are linked to an autoimmune response; however, the exact cause is unknown. It is thought that this autoimmune response could be triggered by normal intestinal bacteria, certain drugs/toxins, or infectious processes. There are also several risk factors for developing IBD[4],[5],[6]:

- Genetics/family history of IBD

- Clients aged 15-30 years and 60 or older

- Northern European/Jewish ancestry

IBD is also more common in developed countries and in cold climates.[7],[8],[9]

Pathophysiology

In IBD, extreme inflammation leads to breakdown of the mucosal layer of the GI tract. This breakdown allows exposure to intestinal viruses or bacteria that can also cause increased inflammation.[10],[11],[12]

In clients with UC, inflammation leads to edema and ulcerations that can bleed. This inflammation spreads in a uniform fashion, starting in the rectum and proceeding up the colon. Over time, the colon becomes inflexible and shortened, ultimately losing the folds (haustra) in the colon.[13],[14],[15]

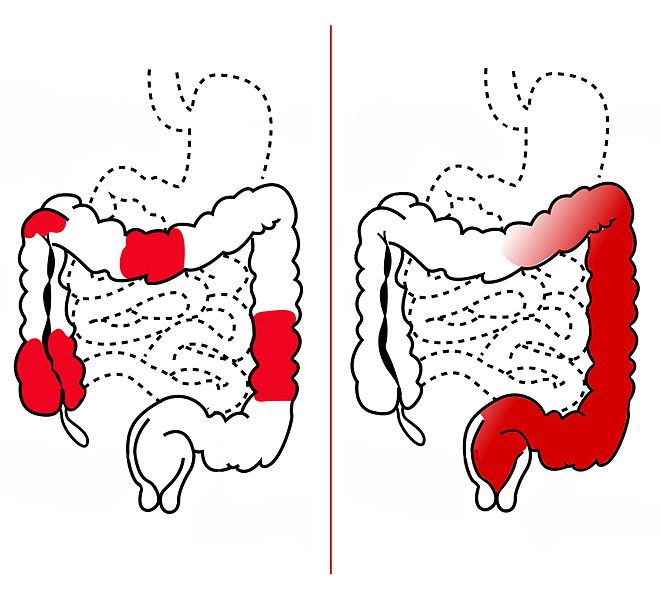

In clients with CD, the inflammation starts out with a singular lesion, which goes on to develop into a deeper ulceration. Unlike UC, which has a uniform spread, a hallmark sign of CD are skip lesions. These are lesions that “skip” around the GI tract, leaving areas of normal or unaffected bowel between them. Over time, the affected areas develop a “cobblestone” appearance. The continued inflammation and resulting scar tissue can lead to the formation of strictures (narrowing) or fistulas (an abnormal passageway between two organs), causing bowel obstruction.[16],[17],[18] See Figure 11.33[19] for an illustration of the differences between CD and UC.

The inflammation of IBD is not limited to the GI tract and can occur in joints/bones, bile ducts, mouth (e.g., canker sores), eyes, and skin.[20],[21],[22]

Assessment

Physical Exam

Although UC and CD share similar characteristics, there are some key differences between the two in signs and symptoms that may be found during assessment. See Table 11.11 for the similarities and differences between the signs and symptoms of UC and CD.[23],[24],[25]

Table 11.11. Comparison of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease |

|---|---|

| Affects only mucosa and submucosa layers of bowel | Affects all layers of bowel |

| Ulcerations confined to large intestine | Ulcerations anywhere in the GI tract, but most commonly appear in small and large intestine |

| Uniform spread of lesions | Skip lesions |

| Diarrhea, may contain blood and mucus | Non-bloody diarrhea |

| Abdominal pain, left upper or left lower quadrant | Abdominal pain, right lower quadrant |

| Tenesmus (Frequent urge to have a bowel movement/sensation that bowels are not empty) | Tenesmus rare |

| Fistulas, abscesses, strictures are rare | Fistulas, abscesses, strictures, fissures may be present |

| Weight loss is rare | Weight loss is common |

| Elevated heart rate, fever, dehydration | Elevated heart rate, fever, dehydration |

| Nausea/vomiting rare | Nausea/vomiting common |

| Symptoms can remit and relapse | Symptoms can remit and relapse |

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

A variety of laboratory and diagnostic tests may be used to diagnose IBD, as well as to rule out other disorders that can cause similar symptoms[26],[27]:

Laboratory Tests

- A complete blood count (CBC) may indicate anemia due to blood loss in stool and an elevated white count due to inflammation. Elevated platelet levels may be seen with Crohn’s disease, increasing the client’s risk for developing deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, and cerebrovascular accident (CVA).

- A comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) may show decreased albumin levels if malnutrition is occurring. Altered electrolyte levels may also occur with severe diarrhea.

- Elevated markers of inflammation such as a C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may occur.

- A variety of stool studies can be used to help diagnose IBD, as well as rule out other conditions. For example, fecal calprotectin levels may be elevated due to inflammation. Stool can also be examined for ova and parasites to rule out a parasitic infection.[28],[29]

Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Diagnostic Tests

- Endoscopy is the gold standard for confirming the presence of IBD by taking a biopsy of the affected tissue. This can be done via EGD but is more commonly done via a colonoscopy.

- Barium studies can also be useful in diagnosing IBD because they can show the characteristic “lead pipe appearance” that is common with UC and the skip lesions that are common in CD.

- Ultrasounds, abdominal X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs can also be ordered to assess for complications caused by IBD such as perforation, bowel obstructions, fistulas, and strictures.[30],[31]

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing priorities for those suffering from inflammatory bowel disease include symptom management, preventing complications, and ensuring adequate nutrition.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with inflammatory bowel disease are created based on the specific needs of the client, their signs and symptoms, and the etiology of the disorder. These nursing diagnoses guide the creation of client specific care plans that encompass client outcomes and nursing interventions, as well the evaluation of those outcomes. These individualized care plans then serve as a guide for client treatment.

Possible nursing diagnoses for those with inflammatory bowel disease are as follows[32],[33],[34]:

- Diarrhea

- Acute Pain

- Deficient Fluid Volume

- Impaired Skin Integrity

- Risk for Infection

- Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements

- Risk for Infective Coping

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification encompasses the creation of short- and long-term goals for the client. These goals are used to create expected outcome statements that are based on the specific needs of the client. Expected outcomes should be specific, measurable, and realistic. These outcomes should be achievable within a set time frame based on the application of appropriate nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes include the following:

- The client will exhibit formed stool that occurs at the client’s normal frequency until the next follow-up appointment.

- The client will rate their pain at 3 or less on a scale of 0 to 10 within two hours.

- The client will exhibit blood pressure and heart rate within normal limits for age, moist mucous membranes, and urine output appropriate for their age during hospitalization.

- The client will exhibit skin in the peri-area that is an appropriate color for race and free from skin breakdown during symptoms of diarrhea.

- The client will verbalize three methods to reduce their risk of contracting an infection after the teaching session.

- The client will maintain a weight within a healthy range that is appropriate for their height until their next follow-up appointment.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical treatment for IBD can be categorized as medication therapy and surgical management.

Specific interventions for IBD will depend on the severity of the disorder, but the ultimate goal is to achieve remission.[35],[36]

Medications

Medication therapy for IBD is often prescribed in a stepwise approach to achieve symptom management. The first step is the use of aminosalicylates, such as mesalamine. If the client does not achieve symptom control with aminosalicylates, the second step adds a steroid medication until inflammation is decreased. Step-three drugs, also known as immune-modifying agents (i.e., thiopurines) or biological drugs (i.e., anti-TNF-alpha medications), are used when steroids do not achieve the desired effect. Step-four medications are disease specific (i.e., for UC or CD) and tend to be experimental with multiple side effects. Many medications used to treat IBD suppress the immune system, increasing the client’s risk for infection.[37],[38].[39],[40]

An alternative approach to stepwise therapy is a step-down approach. This type of therapy refers to the prescription of potent medications first that are then scaled back after symptoms are under control. This approach is generally used for clients with severe cases of IBD or at high-risk for complications.[41],[42],[43],[44]

Lastly, probiotics and antidiarrheals may be used in some clients. Probiotics will help replenish natural flora, and antidiarrheals will help reduce the frequency of stools.[45],[46],[47],[48]

View a supplementary YouTube video[49] on medications used to IBD: Medications for IBD (Crohn’s and Colitis) Featuring Dr. Alan Low | GI Society.

Surgical Management

Surgical removal of the colon (total colectomy) may be required for clients with UC if the disease cannot be controlled with medications or if complications are present. After surgery, the client has a stoma and colostomy collection bag. Although this surgery will cure the gastrointestinal symptoms of UC, it will not cure any extraintestinal manifestations of the disorder.[50],[51],[52],[53]

Surgery may be required for clients with severe CD disease or when complications are present. The site of the surgery is determined by the affected portion of the GI tract and the purpose of the surgery.[54],[55],[56],[57]

Nursing Interventions

When providing nursing care to clients with IBD, nursing interventions can be divided into nursing assessments, nursing actions, and client teaching[58],[59],[60],[61],[62]:

Nursing Assessments

- Assess the client for signs and symptoms of malnutrition and anemia, as these can be caused by poor intake or poor absorption of nutrients.

- Assess the intake and output of the client, noting the number of calories consumed, as well as consistency, characteristics, and frequency of stools.

- Assess for elevated temperature, elevated heart rate, increased white blood cell count, and increased pain, as these could indicate a complication such as perforation and peritonitis. Low blood pressure, elevated heart rate, and low-grade fever may also occur with dehydration.

- Assess the client’s weight daily to monitor for malnutrition, as well as fluid loss due to diarrhea.

- Assess electrolyte levels (particularly potassium and magnesium), as levels can be decreased due to diarrhea.

- Complete frequent abdominal assessments, as altered bowel sounds, increased pain, or distention may mean that a complication such as bowel obstruction or perforation has occurred.

Nursing Actions

- Encourage frequent colonoscopies (every one to two years) due to the high risk of cancer development.

- Seek referrals to mental health services if needed as anxiety and depression are common.

- Encourage the client to receive appropriate vaccinations due to their increased risk for illness.

- Administer intravenous fluids or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) as ordered. TPN may be needed for clients with severe disease or during acute flare-ups.

- Ensure referrals to a stoma nurse if the client has a stoma present.

- Administer IBD medications per provider order.

- Encourage the client to drink two liters of fluid per day to prevent dehydration.

- Encourage the client to join a support group consisting of others with IBD to strengthen their support system.

- Provide peri-care after bowel movements and apply barrier cream as needed.

Review information about parenteral nutrition in the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of the “Nutrition” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Client Teaching

The following teaching topics are typically included in health teaching about IBD:

- Teach the client about the disease process, treatment, and self-managing the disorder. Many medications used to treat IBD have serious side effects that should be reported to the health care provider.

- Review symptoms of perforation and when to seek emergency care.

- Encourage bone mineral density testing as prescribed by their health care provider due to the increased risk of osteoporosis from steroid medications.

- Avoid NSAIDs because they may increase symptoms.

- Avoid foods that may increase symptoms such as dairy, caffeine, alcohol, and foods high in fat and fiber. Clients may benefit from a diet that is bland and high in protein, calories, and vitamins.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with another member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Inflammatory Bowel Disease

RN Recap: Inflammatory Bowel Disease

View a brief YouTube video overview of inflammatory bowel disease[63]:

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “Crohn%27s_Disease_vs._Ulcerative_Colitis.jpg” by RicHard-59 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 10 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Curran, A. (2022, May 16). Inflammatory bowel disease nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 10 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 10 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 10 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Gastrointestinal Society. (2020, November 5). Medications for IBD (Crohn's and Colitis) featuring Dr. Alan Low | GI Society [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFtqqGAvy0Y ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 10 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 10 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Crohn Disease by Ranasinghe & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ulcerative Colitis by Lynch & Hsu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease by McDowell, Farooq, & Haseeb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Vera, M. (2023, October 13). 10 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nursing care plans. https://nurseslabs.com/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Curran, A. (2022, May 16). Inflammatory bowel disease nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/inflammatory-bowel-disease-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 11 - Inflammatory bowel disease [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/FnIXCLwgbt8?si=-Jk5Su-tBFY4Bt3I ↵

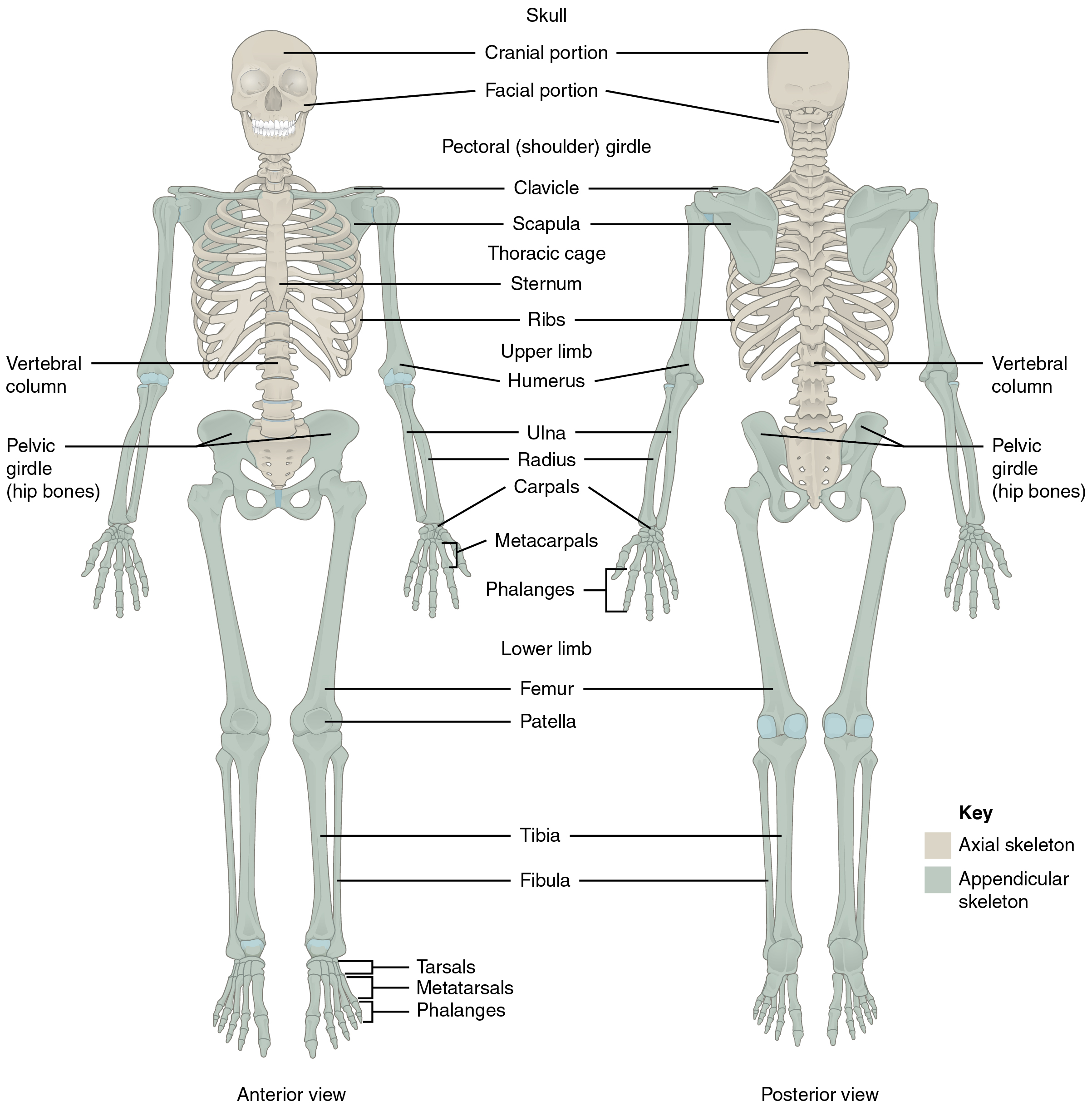

Skeleton

The skeleton is composed of 206 bones that provide the internal supporting structure of the body. See Figure 13.1[1] for an illustration of the major bones in the body. The bones of the lower limbs are adapted for weight-bearing support, stability, and walking. The upper limbs are highly mobile with large range of movements, along with the ability to easily manipulate objects with our hands and opposable thumbs.[2]

For additional information about the bones in the body, visit the OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology book.

Many different bones are connected together by ligaments. Most bones of the skill are held together by sutures, a narrow fibrous joint. Ligaments are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue that strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements of a joint while also limiting the range of these motions to prevent excessive or abnormal joint movements.[3]

Muscles

There are three types of muscle tissue: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Skeletal muscles are attached to the skeleton and produce movement, assist in maintaining posture, protect internal organs, and generate body heat. Skeletal muscles are voluntary, meaning a person is able to consciously control them, but they also depend on signals from the nervous system to work properly. Other types of muscles are involuntary and are controlled by the autonomic nervous system, such as the smooth muscle within our bronchioles.[4] Cardiac muscles are located only in the heart and are involuntary muscles that the autonomic nervous system controls. Smooth muscle makes up the organs, blood vessels, digestive tract, skin, and other areas and is controlled by the autonomic nervous system.

See Figure 13.2[5] for an illustration of skeletal muscle.

To move the skeleton, the tension created by the contraction of the skeletal muscles is transferred to the tendons, strong bands of dense, regular connective tissue that connect muscles to bones.[6]

For additional information about skeletal muscles, visit the OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology book.

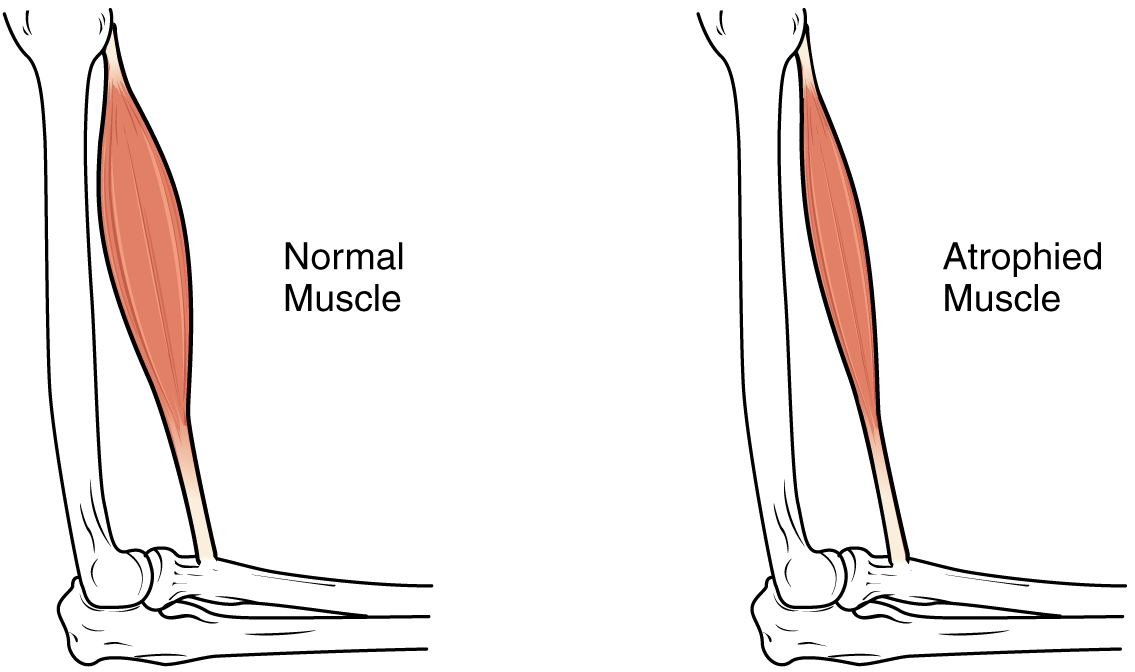

Muscle Atrophy

Muscle atrophy is the thinning or loss of muscle tissue. See Figure 13.3[7] for an image of muscle atrophy. There are three types of muscle atrophy: physiologic, pathologic, and neurogenic.

Physiologic atrophy is caused by not using the muscles and can often be reversed with exercise and improved nutrition. People who are most affected by physiologic atrophy are those who:

- Have seated jobs, health problems that limit movement, or decreased activity levels

- Are bedridden

- Cannot move their limbs because of stroke or other brain disease

- Are in a place that lacks gravity, such as during space flights

Pathologic atrophy is seen with aging, starvation, and adverse effects of long-term use of corticosteroids. Neurogenic atrophy is the most severe type of muscle atrophy. It can be from an injured or diseased nerve that connects to the muscle. Examples of neurogenic atrophy are spinal cord injuries and polio.[8]

Although physiologic atrophy due to disuse can often be reversed with exercise, muscle atrophy caused by age is more complex. The effects of age-related atrophy are especially pronounced in people who are sedentary because the loss of muscle results in functional impairments such as trouble with walking, balance, and posture. These functional impairments can cause decreased quality of life and injuries due to falls.[9]

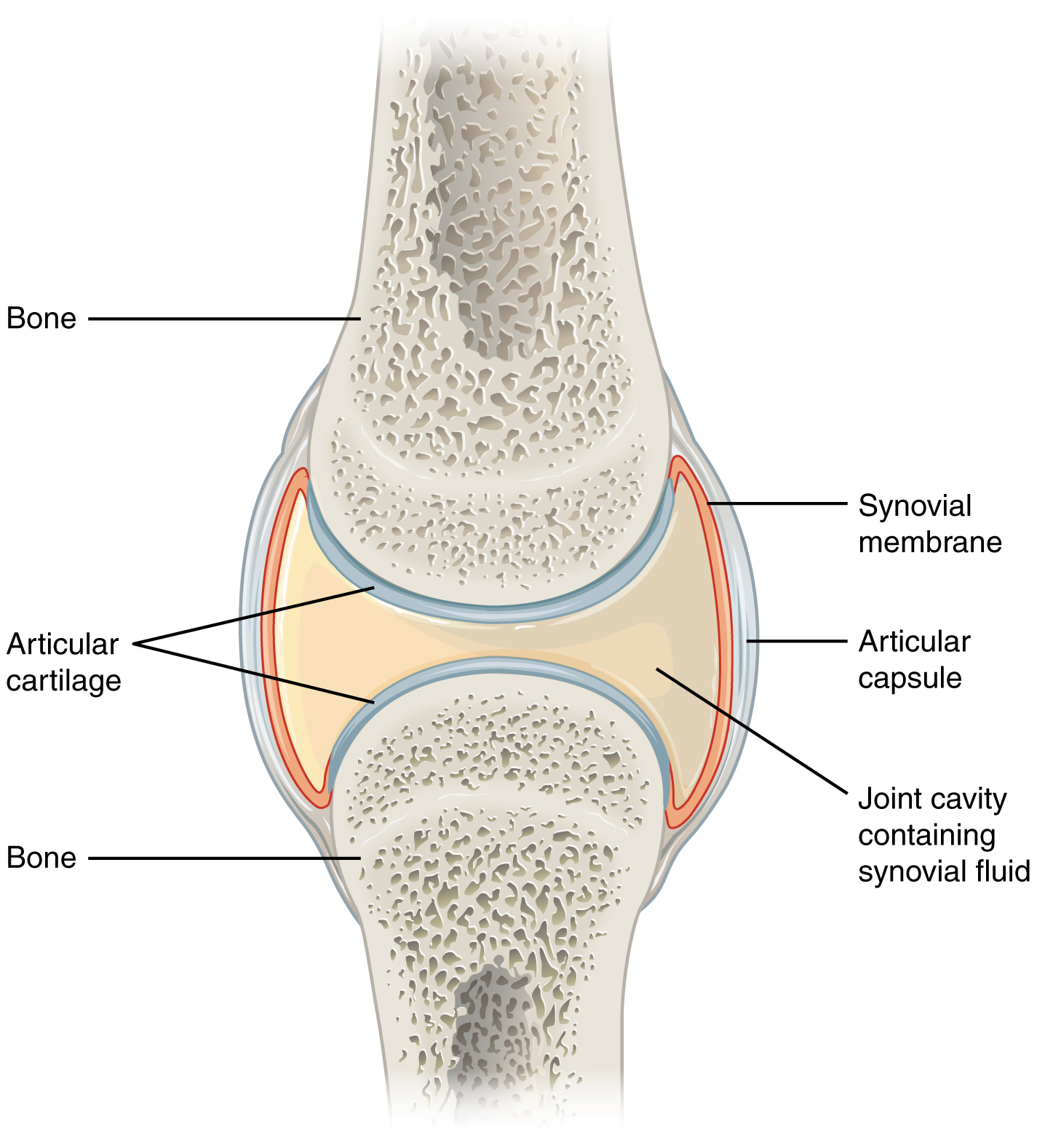

Joints

Joints are the location where bones come together. Many joints allow for movement between the bones. Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body. Synovial joints have a fluid-filled joint cavity where the articulating surfaces of the bones contact and move smoothly against each other. See Figure 13.4[10] for an illustration of a synovial joint. Articular cartilage is smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones where they come together and allows the bones to glide over each other with very little friction. Articular cartilage can be damaged by injury or normal wear and tear. Lining the inner surface of the articular capsule is a thin synovial membrane. The cells of this membrane secrete synovial fluid, a thick, slimy fluid that provides lubrication to further reduce friction between the bones of the joint.[11]

Types of Synovial Joints

There are six types of synovial joints. See Figure 13.5[12] for an illustration of the types of synovial joints. Some joints are relatively immobile but stable. Other joints have more freedom of movement but are at greater risk of injury. For example, the hinge joint of the knee allows flexion and extension, whereas the ball and socket joint of the hip and shoulder allows flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation. The knee, hip, and shoulder joints are commonly injured and are discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

Shoulder Joint

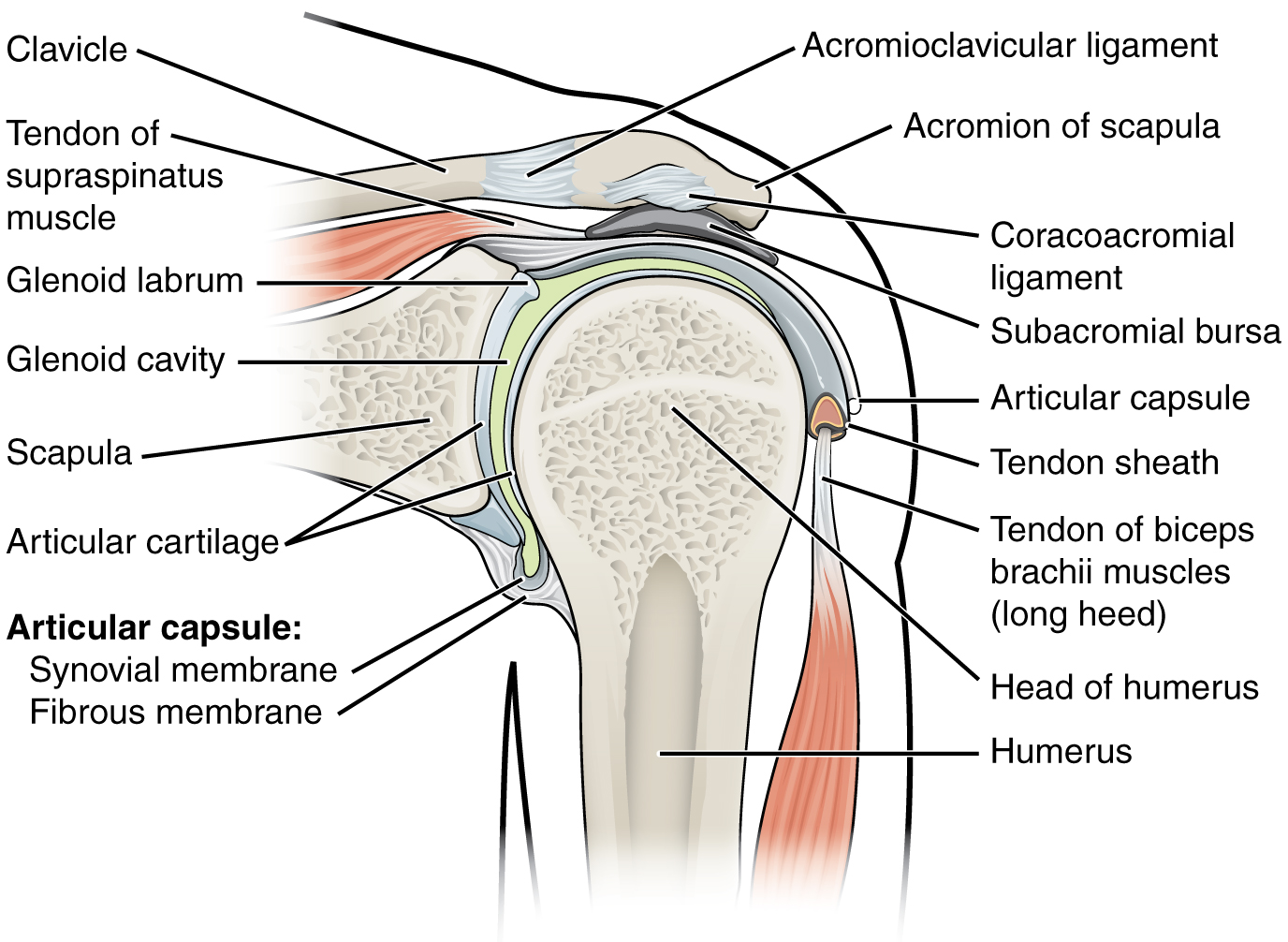

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the articulation between the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula. This joint has the largest range of motion of any joint in the body. See Figure 13.6[13] to review the anatomy of the shoulder joint. Injuries to the shoulder joint are common, especially during repetitive abductive use of the upper limb such as during throwing, swimming, or racquet sports.[14]

Hip Joint

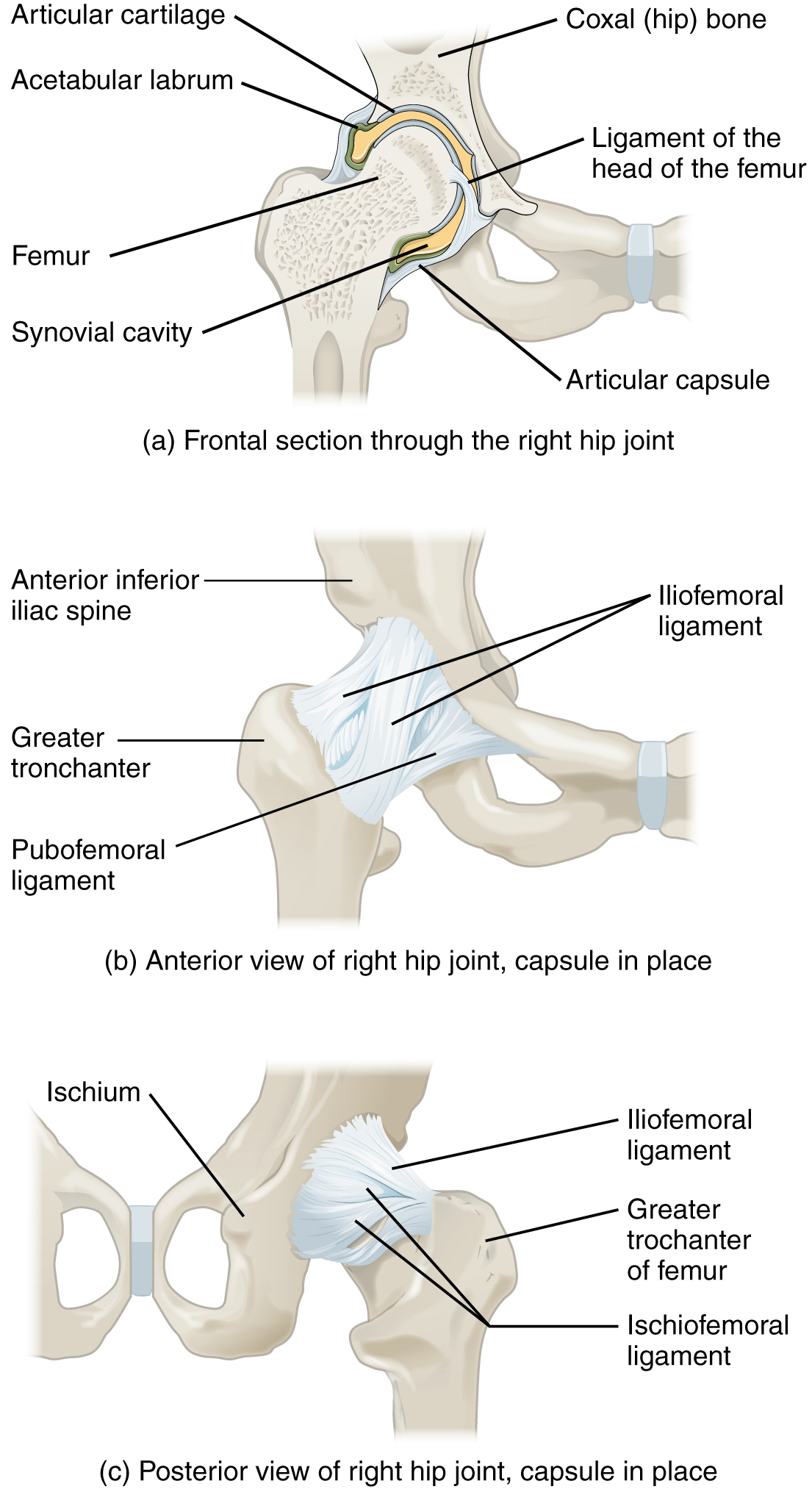

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the hip bone. The hip carries the weight of the body and thus requires strength and stability during standing and walking.[15]

See Figure 13.7[16] for an illustration of the hip joint.

A common hip injury in older adults, often referred to as a “broken hip,” is actually a fracture of the head of the femur. Hip fractures are commonly caused by falls.[17]

See more information about hip fractures under the “Common Musculoskeletal Conditions” section.

Knee Joint

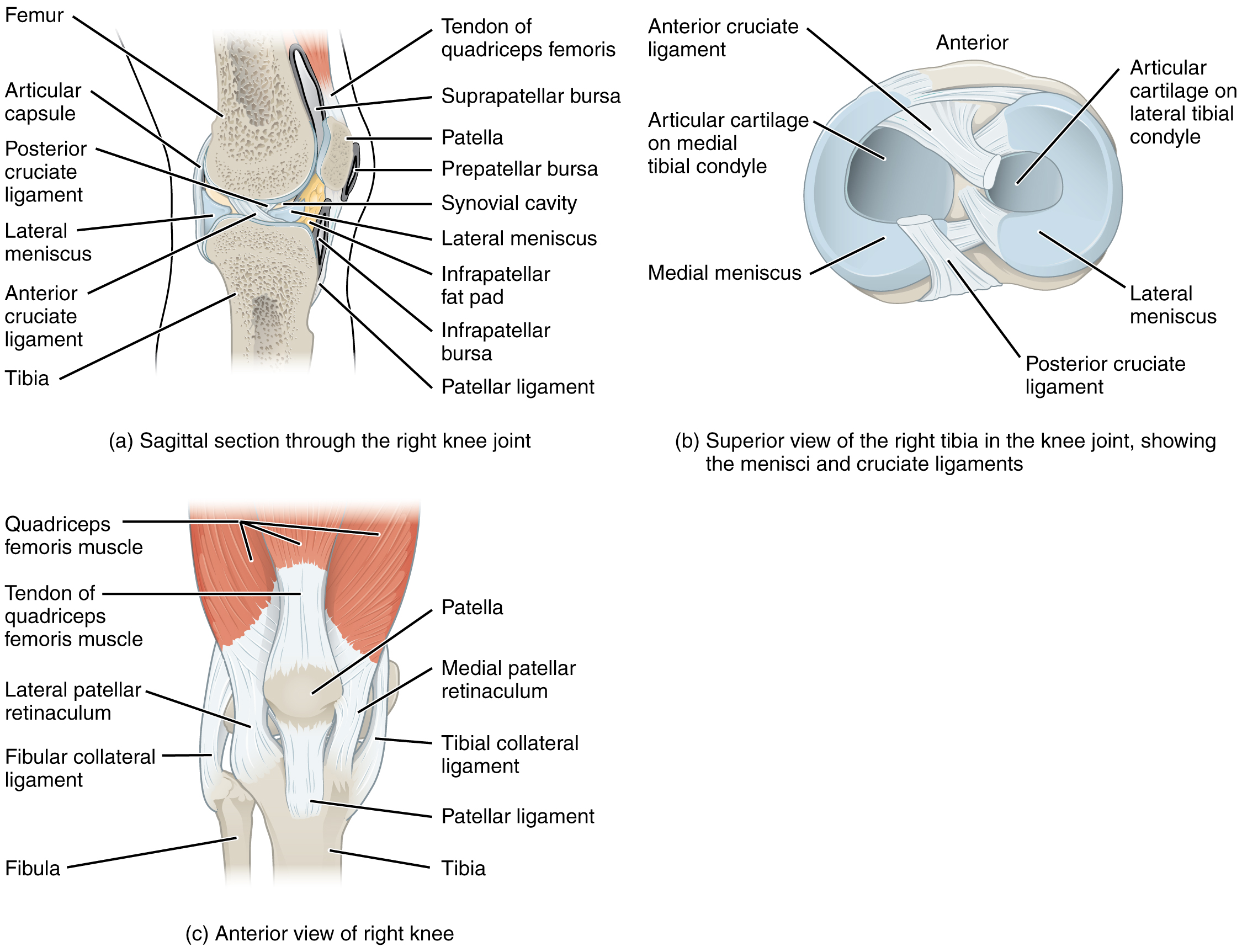

The knee functions as a hinge joint that allows flexion and extension of the leg. In addition, some rotation of the leg is available. See Figure 13.8[18] for an illustration of the knee joint. The knee is vulnerable to injuries associated with hyperextension, twisting, or blows to the medial or lateral side of the joint, particularly while weight-bearing.[19]

The knee joint has multiple ligaments that provide support, especially in the extended position. On the outside of the knee joint are the lateral collateral, medial collateral, and tibial collateral ligaments. The lateral collateral ligament is on the lateral side of the knee and spans from the lateral side of the femur to the head of the fibula. The medial collateral ligament runs from the medial side of the femur to the medial tibia. The tibial collateral ligament crosses the knee and is attached to the articular capsule and to the medial meniscus. In the fully extended knee position, both collateral ligaments are taut and stabilize the knee by preventing side-to-side or rotational motions between the femur and tibia.[20]

Inside the knee joint are the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament. These ligaments are anchored inferiorly to the tibia and run diagonally upward to attach to the inner aspect of a femoral condyle. The posterior cruciate ligament supports the knee when it is flexed and weight-bearing such as when walking downhill. The anterior cruciate ligament becomes tight when the knee is extended and resists hyperextension.[21]

The patella is a bone incorporated into the tendon of the quadriceps muscle, the large muscle of the anterior thigh. The patella protects the quadriceps tendon from friction against the distal femur. Continuing from the patella to the anterior tibia just below the knee is the patellar ligament. Acting via the patella and patellar ligament, the quadriceps is a powerful muscle that extends the leg at the knee and provides support and stabilization for the knee joint.

Located between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia are two articular discs, the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus. Each meniscus is a C-shaped fibrocartilage that provides padding between the bones.[22]

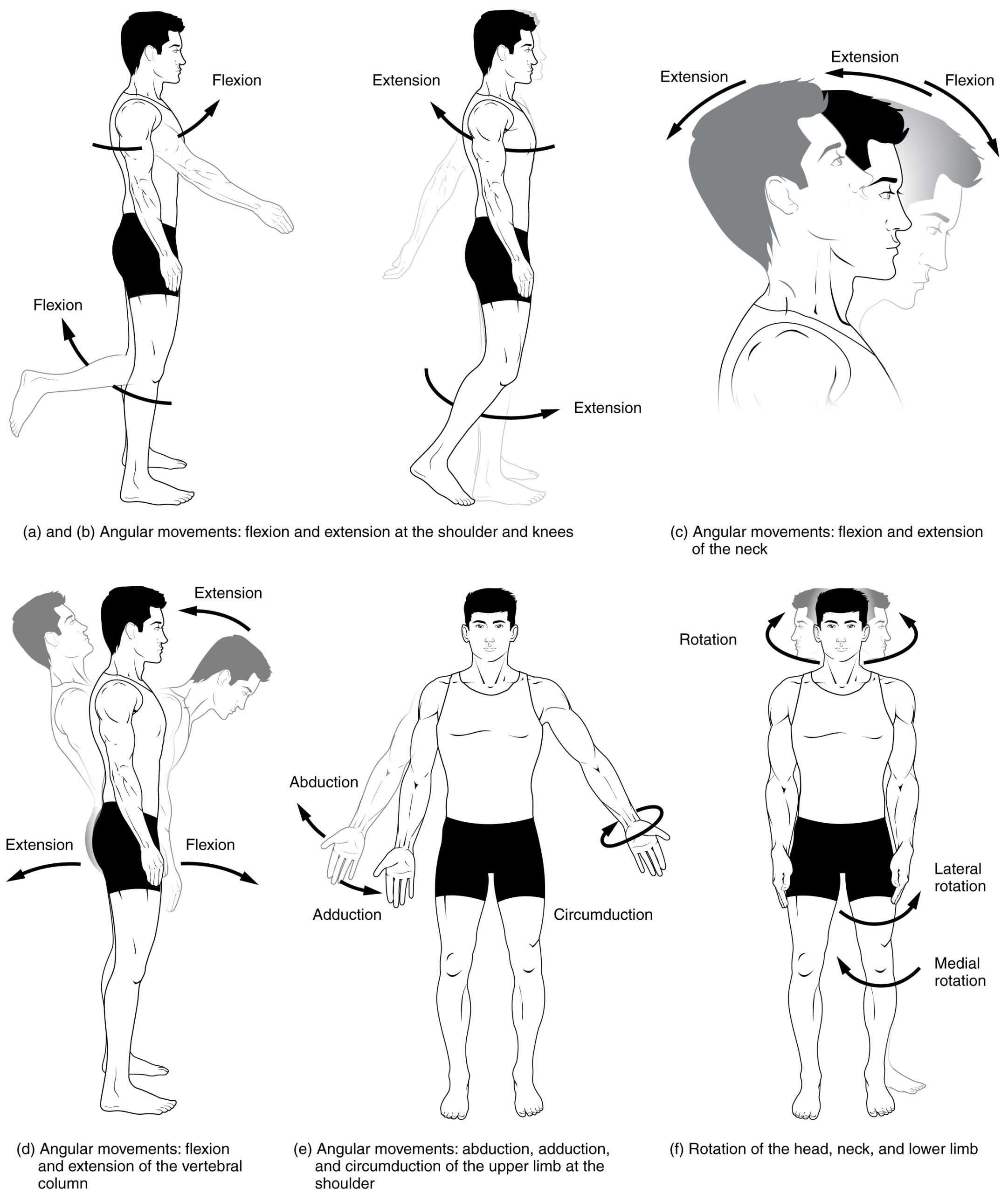

Joint Movements

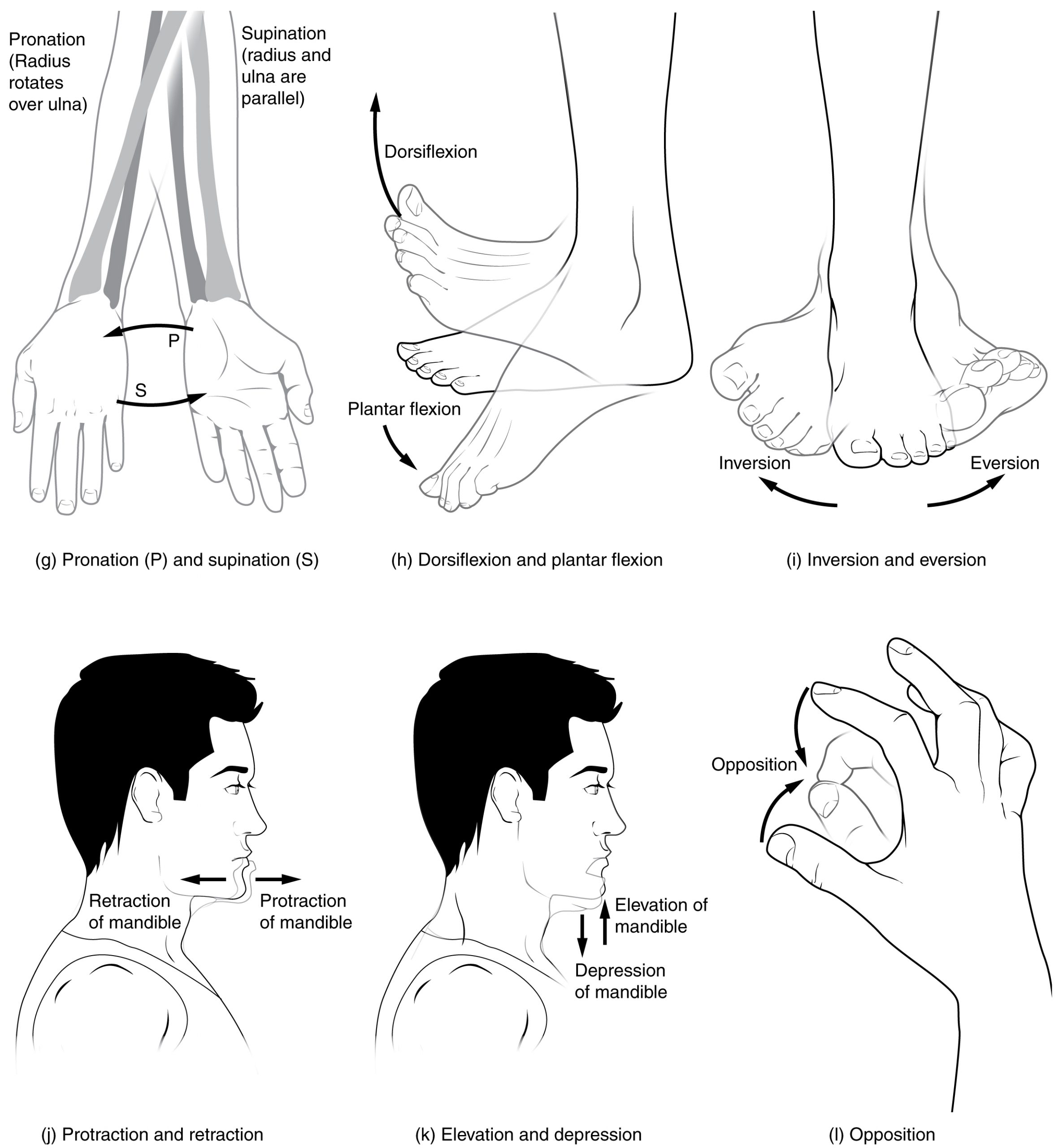

Several movements may be performed by synovial joints. Abduction is the movement away from the midline of the body. Adduction is the movement toward the middle line of the body. Extension is the straightening of limbs (increase in angle) at a joint. Flexion is bending the limbs (reduction of angle) at a joint. Rotation is a circular movement around a fixed point. See Figures 13.9[23] and 13.10[24] for images of the types of movements of different joints in the body.

Joint Sounds

Sounds that occur as joints are moving are often referred to as crepitus. There are many different types of sounds that can occur as a joint moves, and patients may describe these sounds as popping, snapping, catching, clicking, crunching, cracking, crackling, creaking, grinding, grating, and clunking. There are several potential causes of these noises such as bursting of tiny bubbles in the synovial fluid, snapping of ligaments, or a disease condition. While assessing joints, be aware that joint noises are common during activity and are usually painless and harmless, but if they are associated with an injury or are accompanied by pain or swelling, they should be reported to the health care provider for follow-up.[25]

View a supplementary video from Physitutors called Why Your Knees Crack | Joint Crepitations.[26]

Learning Objectives

- Perform an integumentary assessment including the skin, hair, and nails

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span and ethnic and cultural variations

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

Assessing the skin, hair, and nails is part of a routine head-to-toe assessment completed by registered nurses. During inpatient care, a comprehensive skin assessment on admission establishes a baseline for the condition of a patient’s skin and is essential for developing a care plan for the prevention and treatment of skin injuries.[27] Before discussing the components of a routine skin assessment, let’s review the anatomy of the skin and some common skin and hair conditions.