10.9 Rheumatoid Arthritis

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

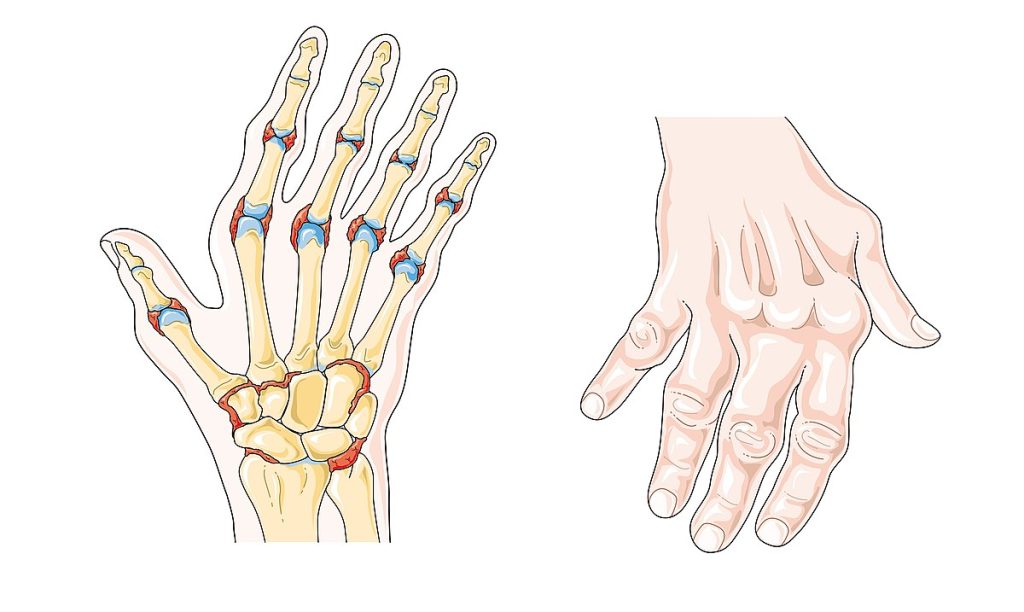

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) causes symptoms such as bilateral joint pain, stiffness, and swelling. It is known for its pattern of remission and exacerbations, where symptoms might improve and worsen intermittently. Deformities may occur like a swan-like deformity of the hands (see Figure 10.37[1]) or boutonniere deformities, which are firm, observable lumps underneath the skin on or near the base of the joint (see Figure 10.38[2]).[3]

Several risk factors contribute to the development of RA. Women are more likely than men to develop RA, and it commonly begins between the ages of 20 and 50. Genetic predisposition also plays a significant role, so family history of RA can increase the likelihood of occurrence. Chronic stress has also been associated with RA because of its effect on the immune system.

Early diagnosis and appropriate management, including medications, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications, aim to reduce inflammation, manage symptoms, and slow down joint damage progression in individuals with RA.[4]

Pathophysiology

RA is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder primarily affecting the synovial tissue (i.e., the lining of joints). The inflammatory process that occurs in RA is bilateral, meaning it affects both sides of the body, and often involves multiple joints simultaneously. The immune system’s attack on the synovial tissue causes chronic inflammation, which, if left untreated, can cause damage to the joint cartilage, bones, and other nearby structures.

Assessment

Physical assessment findings for rheumatoid arthritis vary based on early versus late stages of the disease. A summary of signs and symptoms of early and late stages of rheumatoid arthritis by body system is provided in Table 10.9.

Table 10.9. Manifestations of Early and Late Stages of Rheumatoid Arthritis[5],[6],[7]

| Body System | Early RA Physical Assessment Findings | Late RA Physical Assessment Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | Joint pain and tenderness; swelling, warmth, and erythema at affected joints; morning stiffness lasting greater than 30 minutes; symmetrical involvement of multiple joints (hands, wrists, etc.); muscle weakness; and fatigue | Severe joint deformities (e.g., swan-neck or boutonniere deformities), limited range of motion, joint contractures due to chronic inflammation, joint instability, and muscle wasting due to disuse |

| Cardiovascular | Pericardial friction rub may be heard in auscultation | Increased risk of cardiovascular diseases due to accelerated atherosclerosis |

| Respiratory | Mild pleuritic chest pain or dry cough | Pleurisy (inflammation of lung lining) or interstitial lung disease |

| Neurological | Numbness or tingling due to nerve compression or inflammation. Mild eye dryness or irritation | Peripheral neuropathy, scleritis (inflammation of the eye’s outer layers) |

Diagnostic Testing

Blood tests commonly ordered by health care providers to diagnosis RA include the following[8]:

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF) Antibody Assay: Detects atypical IgG and IgM antibodies commonly found in connective tissue disorders

- Antinuclear Antibody (ANA): Measures antibodies that target cell nuclei, contributing to tissue damage in autoimmune conditions

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): Confirms the presence of inflammation or infection throughout the body

- C-reactive Protein (CRP): Assists in gauging the level of inflammation present

Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.” Diagnostic testing may include X-rays, MRIs, and ultrasounds.

Nursing Diagnoses

For clients diagnosed with RA, nursing diagnoses often revolve around managing symptoms, promoting mobility, and providing support. Common nursing diagnoses for clients with RA include the following:

- Chronic Pain

- Impaired Mobility

- Fatigue

- Risk for Altered Skin Integrity

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions. Sample expected outcomes for a client diagnosed with RA include the following:

- The client will report a reduction in pain levels to 3/10 or less on the pain scale within two weeks.

- The client will accurately demonstrate prescribed exercises and mobility-enhancing techniques within two weeks.

- The client will verbalize a reduction in fatigue levels, reporting increased energy to perform daily activities within three weeks.

- The client will maintain intact skin over nodules utilizing moisturizing techniques.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions include medication therapy and physical/occupational therapy.

Medication Therapy

Medication therapy focuses on managing symptoms, reducing inflammation, and slowing disease progression and may include the following medications[9],[10]:

- Analgesics, Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), and Opioids: Acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, or opioids may be prescribed to manage chronic pain.

- Antimalarial Medications: Antimalarial medications like hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine may be prescribed for their anti-inflammatory properties to manage joint pain and fatigue and to prevent flare-ups.

- Steroids: Prednisone is a corticosteroid that can swiftly reduce inflammation and provide rapid relief. It is often prescribed for acute flare-ups of RA or as a short-term bridge therapy. Intra-articular injections of corticosteroids directly into affected joints can provide targeted relief from pain and inflammation, particularly when specific joints are severely affected.

- Immunosuppressants: Immunosuppressants help to slow down the immune system’s response that causes joint inflammation and damage. Cyclophosphamide is a potent immunosuppressant that may be considered in severe cases of RA.

- Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs): Medications like methotrexate and sulfasalazine aim to slow or alter the disease progression by modifying the immune response. Methotrexate is one of the most commonly used DMARDs due to its effectiveness in reducing inflammation and slowing joint damage. DMARDs have potentially distressing and life-threatening side effects such as drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, torsades de pointes, hepatotoxicity, or aplastic anemia.

- Biological Response Modifiers: Also known as biologics, these medications target specific components of the immune system to reduce inflammation.

- Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Inhibitors: Medications like infliximab and adalimumab are biologics that target TNF, a protein involved in the inflammatory response. They can effectively reduce symptoms and slow joint damage. However, caution is necessary as these medications can suppress the immune system, increasing susceptibility to infections. Therefore, they might not be suitable for clients with serious infections.

Physical/Occupational Therapy

Structured exercise programs and physical therapy are integral for maintaining joint flexibility, strength, and function. Customized exercises help manage pain, prevent muscle atrophy, and improve mobility. Occupational therapists assist clients in adapting their daily routines and environments to reduce strain on joints. They provide guidance on adaptive equipment and techniques for tasks like dressing, cooking, and using tools.[11]

Assistive devices such as splints, braces, or orthotics may be recommended to support and protect affected joints, reducing strain and improving function.[12]

Nursing Interventions

Pain Management

Nurses assess client’s pain levels using pain scales to effectively manage pain and evaluate the effectiveness of pain medications and nonpharmacological interventions such as heat or cold therapy, massage, or relaxation techniques.

Skin and Joint Care

Nurses assist in joint protection by reinforcing the effective use of splints or braces. If these devices are used, nurses perform skin assessments on areas at risk for skin breakdown and educate clients on proper skin care to prevent pressure injuries.

Health Teaching

Clients taking immune-suppression drugs must follow stringent infection control techniques to minimize the risk of infections. Nurses provide teaching on the following topics:

- Perform Good Hand and Personal Hygiene: Regular and thorough handwashing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers helps prevent the spread of infections. Maintaining good personal hygiene, including regular bathing and oral care, helps prevent the spread of bacteria and viruses.

- Avoid Individuals Who Are Ill: Clients should avoid close contact with individuals who are sick or showing possible signs of infection to reduce the risk of exposure.

- Stay Current on Vaccinations: Staying up-to-date on vaccinations, including flu shots and other recommended vaccines, can provide additional protection against preventable infections.

- Follow Safe Food Handling Practices: Ensuring that food is properly cooked and handling it with care help prevent foodborne illnesses.

- Avoid Crowded Places: Limiting exposure to crowded places, especially during flu seasons or outbreaks, can reduce the risk of coming into contact with infectious agents.

- Use Protective Equipment: Wear face masks, gloves, and other protective equipment in health care and crowded settings to provide an extra layer of protection.

- Maintain Environmental Hygiene: Keep living spaces clean. Regularly disinfect surfaces to help eliminate potential sources of infection.

- Monitor Symptoms: Monitor for signs of infection and seek prompt medical attention if symptoms arise.

- Communicate with Health Care Providers: Open communication with health care providers about symptoms, concerns, and any changes in health status is essential for proper management of RA.

Advocacy and Psychosocial Support

Nurses advocate for clients’ needs within the health care team, ensuring comprehensive care and addressing barriers to treatment. Nurses may collaborate with other health care professionals like physical therapists, occupational therapists, and rheumatologists to ensure a multidisciplinary approach to client care. Nurses promote optimal functioning and independence by providing health teaching on self-care and self-management of chronic illness, including joint protection, energy conservation, and the use of assistive devices to enhance independence.

Nurses also provide active listening and therapeutic communication while addressing the emotional impact of living with a chronic illness. Clients are encouraged to participate in support groups or other community resources to cope with chronic illness and maximize emotional well-being.

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

![]() RN Recap: Rheumatoid Arthritis

RN Recap: Rheumatoid Arthritis

View a brief YouTube video overview of rheumatoid arthritis[13]:

- “Rheumatoid_arthritis_--_Smart-Servier_(cropped).jpg” by Laboratoires Servier is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “RA_hand_deformity.JPG” by Prashanthns is licensed CC BY-SA 3.0. ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2022, November). Rheumatoid arthritis. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/rheumatoid-arthritis ↵

- Arthritis Foundation. (2021, October 15). Rheumatoid arthritis: Causes, symptoms, treatments and more. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/rheumatoid-arthritis ↵

- Arthritis Foundation. (2021, October 15). Rheumatoid arthritis: Causes, symptoms, treatments and more. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/rheumatoid-arthritis ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2022, November). Rheumatoid arthritis. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/rheumatoid-arthritis ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2024. Rheumatoid arthritis; [reviewed 2023, Jan. 25; cited 2023, Dec. 15). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000431.htm ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Diagnosing bone disorders. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/diagnosing-bone-disorders. ↵

- Arthritis Foundation. (2021, October 15). Rheumatoid arthritis: Causes, symptoms, treatments and more. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/rheumatoid-arthritis ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2024. Rheumatoid arthritis; [reviewed 2023, Jan. 25; cited 2023, Dec. 15). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000431.htm ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2022, November). Rheumatoid arthritis. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/rheumatoid-arthritis ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2022, November). Rheumatoid arthritis. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/rheumatoid-arthritis ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 10 - Rheumatoid arthritis [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/Jd4KWLSMy9M?si=VJX_ZKbuX7Lm9vd3 ↵

What is Blood Pressure?

A blood pressure reading is the measurement of the force of blood against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps blood through the body. It is reported in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). This pressure changes in the arteries when the heart is contracting compared to when it is resting and filling with blood. Blood pressure is typically expressed as the reflection of two numbers, systolic pressure and diastolic pressure. The systolic blood pressure is the maximum pressure on the arteries during systole, the phase of the heartbeat when the ventricles contract. This is the top number of a blood pressure reading. Systole causes the ejection of blood out of the ventricles and into the aorta and pulmonary arteries. The diastolic blood pressure is the resting pressure on the arteries during diastole, the phase between each contraction of the heart when the ventricles are filling with blood. This is the bottom number of the blood pressure reading.[1] Therefore, 120/80 indicates the systolic blood pressure is 120 mm Hg and the diastolic blood pressure is 80 mm Hg.

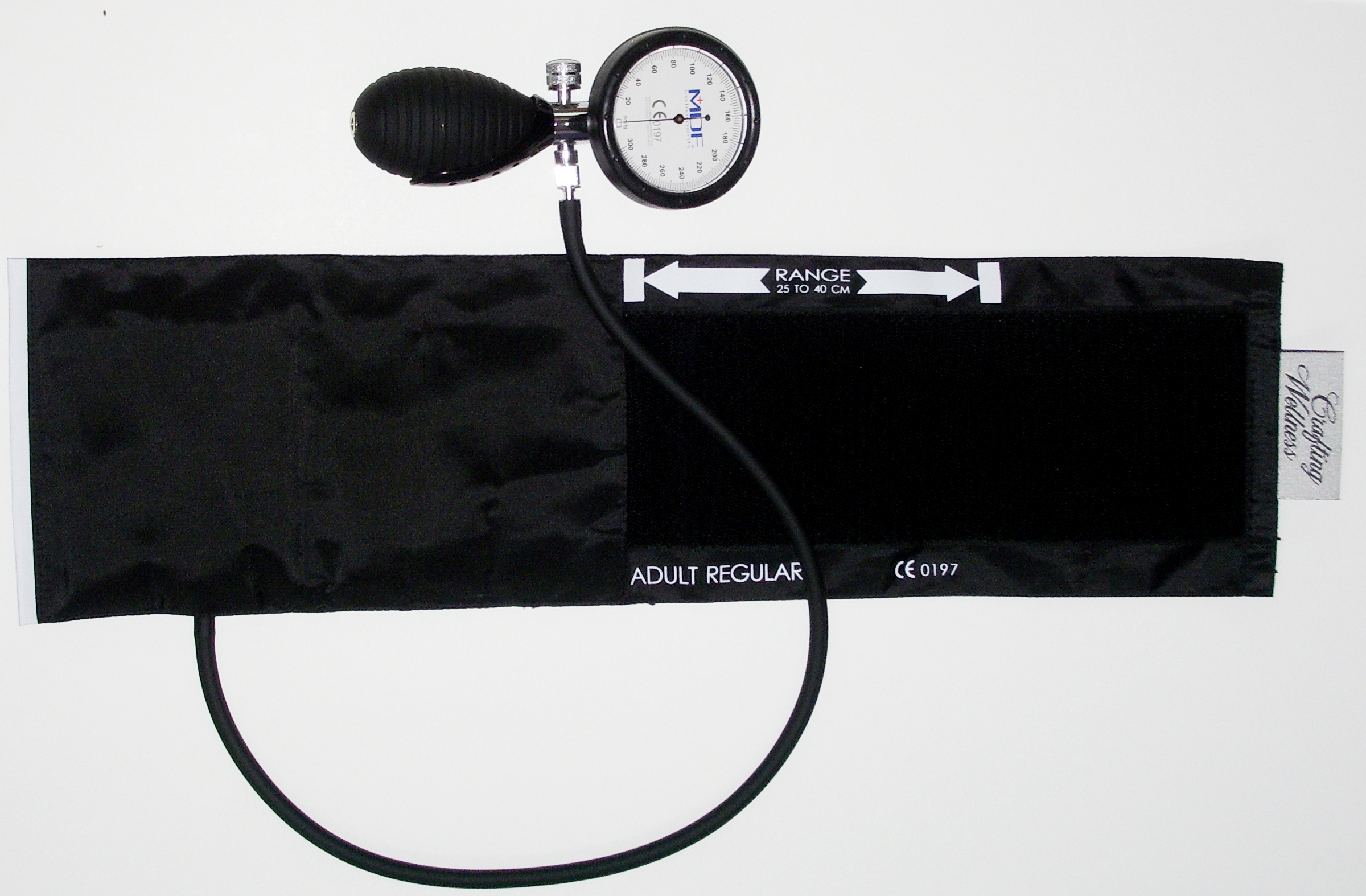

Blood pressure measurements are obtained using a stethoscope and a sphygmomanometer, also called a blood pressure cuff. To obtain a manual blood pressure reading, the blood pressure cuff is placed around a patient's extremity, and a stethoscope is placed over an artery. For most blood pressure readings, the cuff is usually placed around the upper arm, and the stethoscope is placed over the brachial artery. The cuff is inflated to constrict the artery until the pulse is no longer palpable, and then it is deflated slowly. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that the blood pressure cuff be inflated at least 30 mmHg above the point at which the radial pulse is no longer palpable. The first appearance of sounds, called Korotkoff sounds, are noted as the systolic blood pressure reading. Korotkoff sounds are named after Dr. Korotkoff, who first discovered the audible sounds of blood pressure when the arm is constricted.[2] The blood pressure cuff continues to be deflated until Korotkoff sounds disappear. The last Korotkoff sounds reflect the diastolic blood pressure reading.[3] It is important to deflate the cuff slowly at no more than 2-3 mmHg per second to ensure that the absence of pulse is noted promptly and that the reading is accurate. Blood pressure readings are documented as systolic blood pressure/diastolic pressure, for example, 120/80 mmHg.

Abnormal blood pressure readings can signify an area of concern and a need for intervention. Normal adult blood pressure is less than 120/80 mmHg. Hypertension is the medical term for elevated blood pressure readings of 130/80 mmHg or higher. See Table 3.2 for blood pressure categories according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Blood Pressure Guidelines.[4] Prior to diagnosing a person with hypertension, the health care provider will calculate an average blood pressure based on two or more blood pressure readings obtained on two or more occasions.

For more information about hypertension and blood pressure medications, visit the "Cardiovascular and Renal System" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Hypotension is the medical term for low blood pressure readings less than 90/60 mmHg.[5] Hypotension can be caused by dehydration, bleeding, cardiac conditions, and the side effects of many medications. Hypotension can be of significant concern because of the potential lack of perfusion to critical organs when blood pressures are low. Orthostatic hypotension is a drop in blood pressure that occurs when moving from a lying down (supine) or seated position to a standing (upright) position. When measuring blood pressure, orthostatic hypotension is defined as a decrease in blood pressure by at least 20 mmHg systolic or 10 mmHg diastolic within three minutes of standing. When a person stands, gravity moves blood from the upper body to the lower limbs. As a result, there is a temporary reduction in the amount of blood in the upper body for the heart to pump, which decreases blood pressure. Normally, the body quickly counteracts the force of gravity and maintains stable blood pressure and blood flow. In most people, this transient drop in blood pressure goes unnoticed. However, some patients with orthostatic hypotension can experience light-headedness, dizziness, or fainting. This is a significant safety concern because of the increased risk of falls and injury, particularly in older adults.[6] Orthostatic hypotension is also commonly referred to a postural hypotension. When obtaining orthostatic vital signs, the pulse rate may also be collected. If the pulse increases by 30 beats/minute or more while the patient stands (or sits if unable to stand), this indicates a significant change.

Perform the following actions when obtaining orthostatic vital signs:

- Have the patient stand upright for 1 minute if able.

- Obtain the blood pressure measurement while the patient stands using the same arm and the same equipment as the previous measurement that was taken with patient lying or sitting.

- Obtain the radial pulse again.

- Repeat the blood pressure and radial pulse measurements again at 3 minutes. Waiting several minutes before repeating the measurements allows time for the autonomic nervous system to compensate for blood volume shifts after position change in the patient without orthostatic hypotension.

- If the patient has symptoms that suggest orthostatic hypotension but doesn't have documented orthostatic hypotension, repeat blood pressure measurement.

Tip: Some patients may not demonstrate significant decreases in blood pressure until they stand for more than 3 minutes.

Table 3.2 Blood Pressure Categories[7]

| Blood Pressure Category | Systolic mm Hg | Diastolic mm Hg |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Less than 120 | Less than80 |

| Elevated | 120-129 | Less than 80 |

| Stage 1 | 130-139 | 80-89 |

| Stage 2 | 140 or higher | Greater or equal to 90 |

| Hypertensive Crisis | Greater than 180 | Greater than 120 |

View Ahmend Alzawi's Korotkoff sounds video on YouTube.[8]

Equipment to Measure Blood Pressure

Manual Blood Pressure

A sphygmomanometer, commonly called a blood pressure cuff, is used to measure blood pressure while Korotkoff sounds are auscultated using a stethoscope. See Figure 3.1[9] for an image of a sphygmomanometer.

There are various sizes of blood pressure cuffs. It is crucial to select the appropriate size for the patient to obtain an accurate reading. An undersized cuff will cause an artificially high blood pressure reading, and an oversized cuff will produce an artificially low reading. See Figure 3.2[10] for an image of various sizes of blood pressure cuffs ranging in size for a large adult to an infant.

The width of the cuff should be 40% of the person’s arm circumference, and the length of the cuff’s bladder should be 80–100% of the person’s arm circumference. Keep in mind that only about half of the blood pressure cuff is the bladder and the other half is cloth with a hook and loop fastener to secure it around the arm.

View Ryerson University's accurate blood pressure cuff sizing video on YouTube.[11]

Automatic Blood Pressure Equipment

Automatic blood pressure monitors are often used in health care settings to efficiently measure blood pressure for multiple patients or to repeatedly measure a single patient’s blood pressure at a specific frequency such as every 15 minutes. See Figure 3.3[12] for an image of an automatic blood pressure monitor. To use an automatic blood pressure monitor, appropriately position the patient and place the correctly sized blood pressure cuff on their bare arm or other extremity. Press the start button on the monitor. The cuff will automatically inflate and then deflate at a rate of 2 mmHg per second. The monitor digitally displays the blood pressure reading when done. If the blood pressure reading is unexpected, it is important to follow up by obtaining a reading using a manual blood pressure cuff. Additionally, automatic blood pressure monitors should not be used if the patient has a rapid or irregular heart rhythm, such as atrial fibrillation, or has tremors as it may lead to an inaccurate reading.