10.2 Review of Anatomy & Physiology of the Musculoskeletal System

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Skeletal System Review

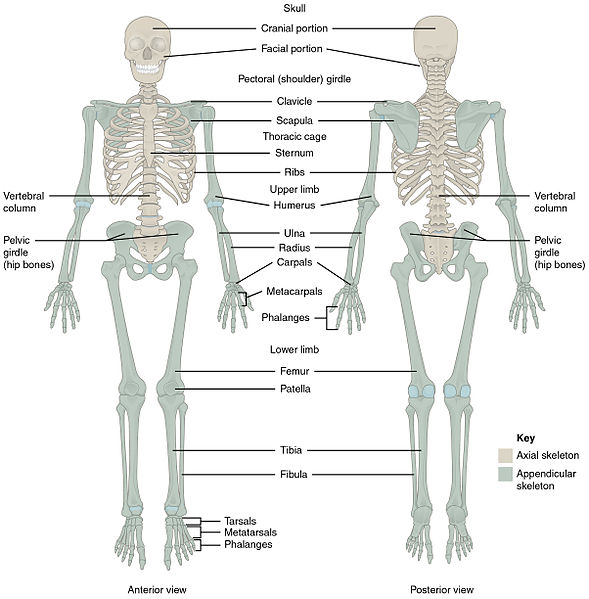

The skeletal system includes bones, joints, cartilages, and ligaments. It supports the body, facilitates movement with muscles, protects organs, produces blood cells, and stores and releases calcium to maintain homeostasis.[1] See Figure 10.1[2] for an illustration of the skeletal system. The skeletal system is subdivided into two major divisions called the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton. Each division is further discussed in the following sections, along with related medical terms.

The Axial Skeleton

The axial skeleton forms the central axis of the body and includes the bones of the head, neck, chest, and back. It serves to protect the brain, spinal cord, heart, and lungs. It also serves as the attachment site for muscles that move the head, neck, back, shoulders, and hip joints. The axial skeleton includes the cranium, hyoid, vertebral column, and thoracic cage.[3]

Cranium

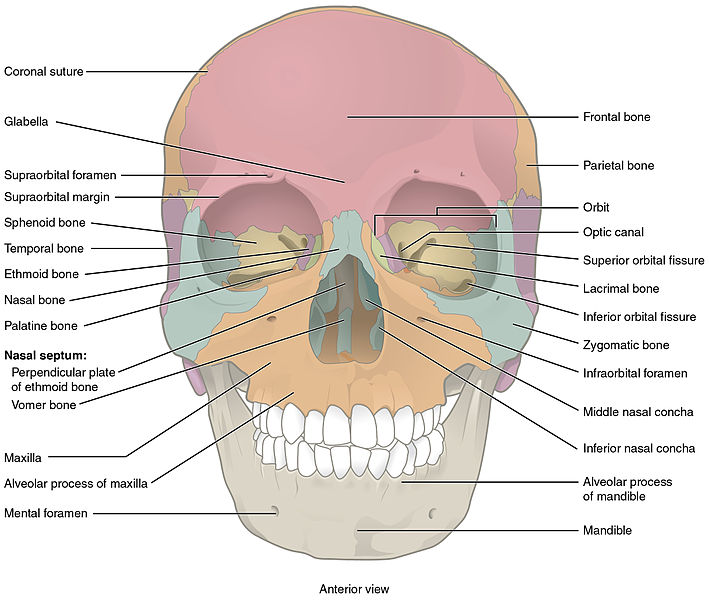

The cranium is the bones that form the head, including the skull and the facial bones. It supports the face and protects the brain. See Figure 10.2[4] for an illustration of the anterior bones of the skull and the face.

The major bones of the skull include the following:

- Frontal: Forehead

- Parietal: Upper lateral sides of the skull

- Temporal: Lower lateral sides of the skull

- Sphenoid: Posterior eye sockets and part of the base of the skull

- Ethmoid: Part of the nose and base of the skull

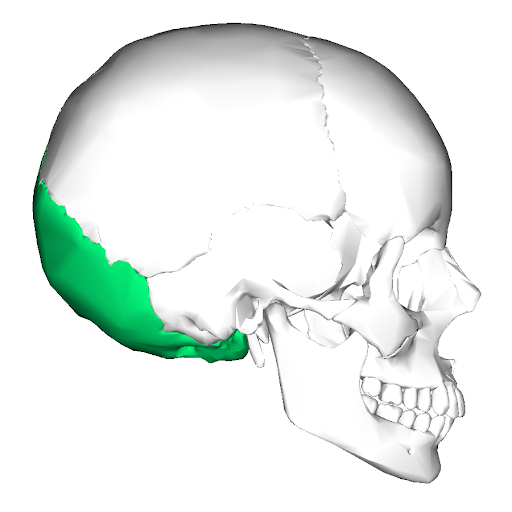

- Occipital: Posterior skull and base of the skull (See Figure 10.3[5] for an image of the occipital bone.)

The facial bones form the upper and lower jaws, the nose, nasal cavity and nasal septum, and the orbit. The facial bones include 14 bones, with six paired bones and two unpaired bones. The paired bones are the zygomatic, maxillary, palatine, nasal, lacrimal, and inferior conchae bones. The unpaired bones are the vomer and mandible bones.

- Zygomatic: Pair of cheekbones

- Maxillary: Upper jaw and hard palate

- Palatine: Pair of L-shaped bones between the maxilla and the sphenoid that form the hard palate, walls of the nasal cavity, and orbital floor of the eye

- Nasal: Pair of bones that form the bridge of the nose

- Lacrimal: Walls of the inner orbit (i.e., eye socket)

- Inferior conchae: Lower lateral walls of the nasal cavity

- Vomer: Bone that separates the left and right nasal cavity

- Mandible: Lower jawbone and only movable bone of the skull

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a hinge joint between the temporal bone and the mandible that allows for the opening, closing, protrusion, retraction, and lateral movement of the lower jaw.

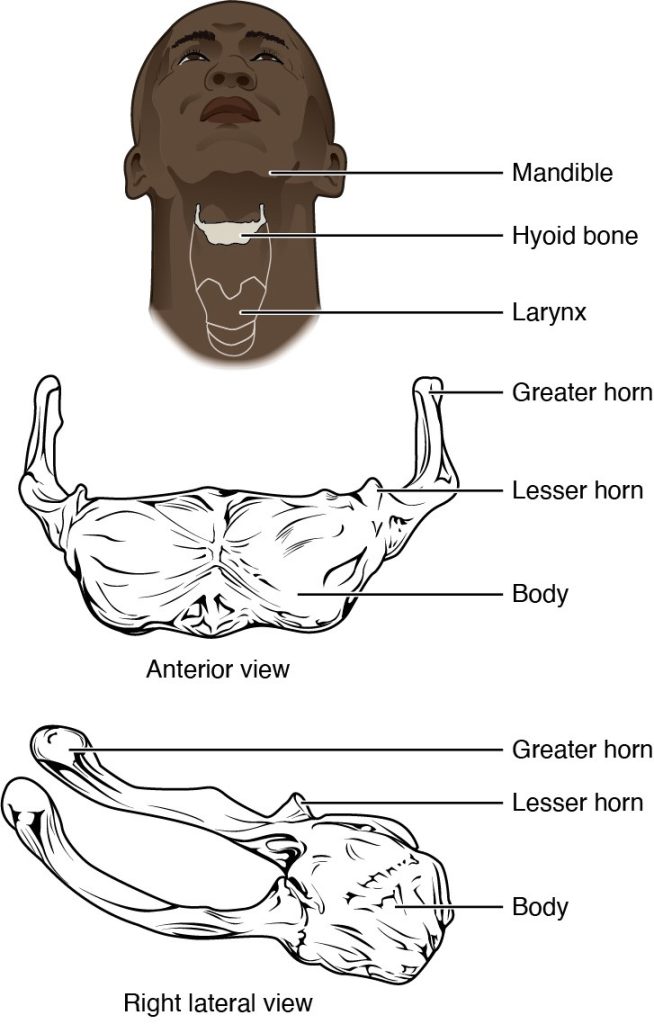

Hyoid

The hyoid bone is an independent bone that does not contact any other bone and, thus, is not part of the skull. It is a small U-shaped bone located in the upper neck near the level of the inferior mandible, with the tips of the “U” pointing posteriorly. The hyoid serves as the base for the tongue above and is attached to the larynx and the pharynx below. Movements of the hyoid are coordinated with movements of the tongue, larynx, and pharynx during swallowing and speaking. See Figure 10.4[6] for an illustration of the hyoid bone.

Vertebrae and Vertebral Column

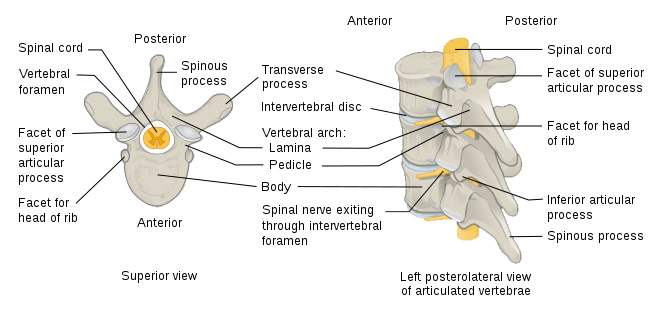

The vertebral column consists of vertebrae that are separated by intervertebral disks. Intervertebral disks are made up of cartilage that act as shock absorbers and allow for flexibility in the spine. The spinal cord runs through the center of the vertebrae. See Figure 10.5[7] for an illustration of the parts of a vertebra. A herniated disk refers to a condition in which a disk protrudes beyond the normal confines of the vertebrae.

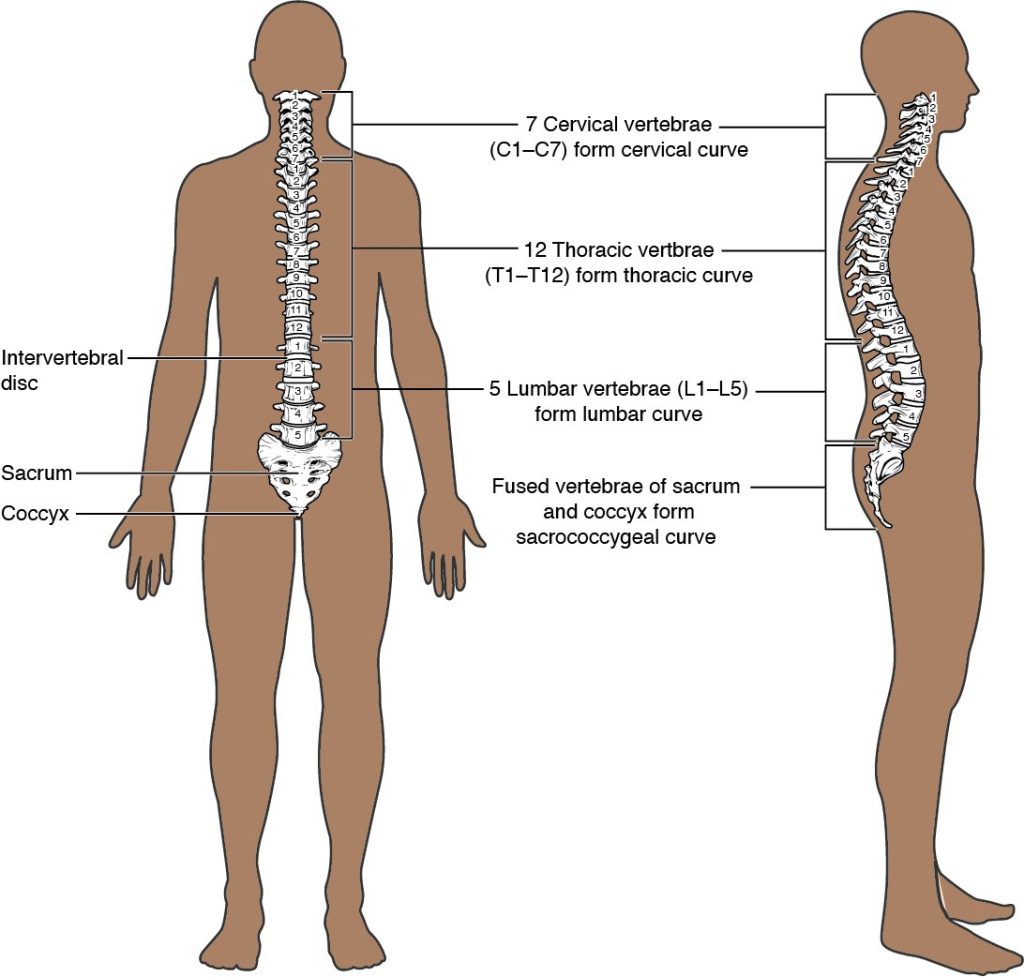

Together, the vertebrae and intervertebral disks form the vertebral column, also known as the spinal column. It is a flexible column that supports the head, neck, and body and allows for their movements. It also protects the spinal cord, which passes down the back through openings in the vertebrae. View an illustration of the vertebral column in Figure 10.6.[8]

The vertebral column is normally curved, with two primary curvatures (thoracic and sacrococcygeal curves) and two secondary curvatures (cervical and lumbar curves).

Vertebrae Regions

The vertebrae are divided into five regions called the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, and coccyx:

- Cervical: The first 7 vertebrae in the neck region, C1 to C7

- Thoracic: The next 12 vertebrae that form the outward curvature of the spine, T1 to T12

- Lumbar: The next 5 vertebrae that form the inner curvature of spine, L1 to L5

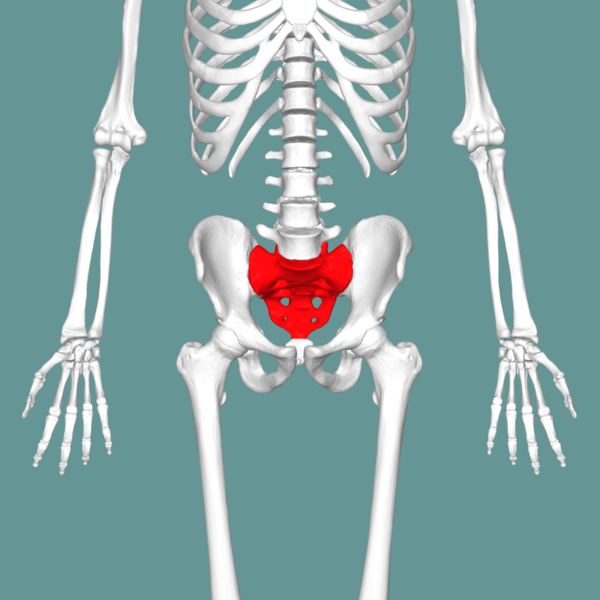

- Sacrum: The triangular-shaped bone at the base of the spine, formed by the fusion of five sacral vertebrae, a process that does not begin until after the age of 20 (See Figure 10.7[9] for an illustration of the sacrum.)

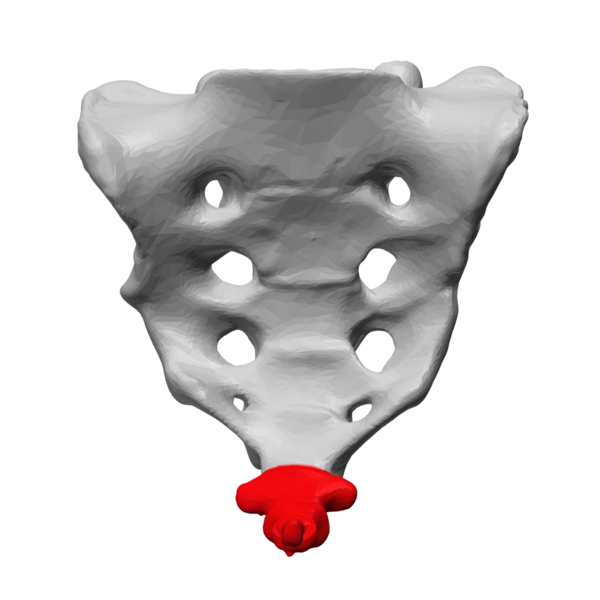

- Coccyx: The tailbone, formed by the fusion of four very small coccygeal vertebrae (See Figure 10.8[10] for an illustration of the coccyx.)

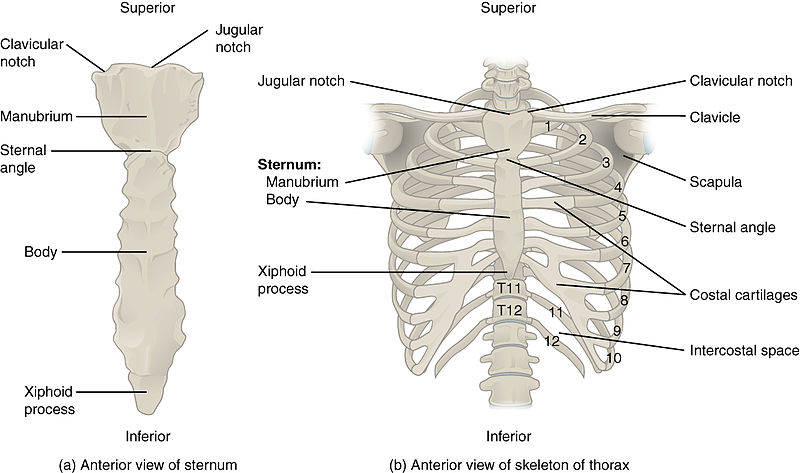

Thoracic Cage

The thoracic cage, commonly known as the rib cage, forms the chest (thorax). It consists of the sternum and 12 pairs of ribs, along with their costal cartilages. The ribs are anchored posteriorly to the 12 thoracic vertebrae (T1–T12). See Figure 10.9[11] for an illustration of the thoracic cage. The thoracic cage protects the heart and lungs.

The sternum, also known as the breastbone, is divided into three parts:

- Manubrium: The upper portion of the sternum

- Body: The middle portion of the sternum

- Xiphoid process: The lower portion of the sternum made of cartilage

The 12 sets of ribs can be classified as true ribs, false ribs, and floating ribs:

- True ribs: Ribs 1-7 that are attached to the front of the sternum

- False ribs: Ribs 8, 9, and 10 that are attached to the cartilage that joins the sternum

- Floating ribs: Ribs 11 and 12 that are not attached to the front of the sternum

Intercostal means between the ribs. For example, people with labored breathing may experience intercostal retractions, where the muscles pull in between the ribs.

The Appendicular Skeleton

The appendicular skeleton includes the upper and lower limbs, plus the bones that attach each limb to the axial skeleton.[12]

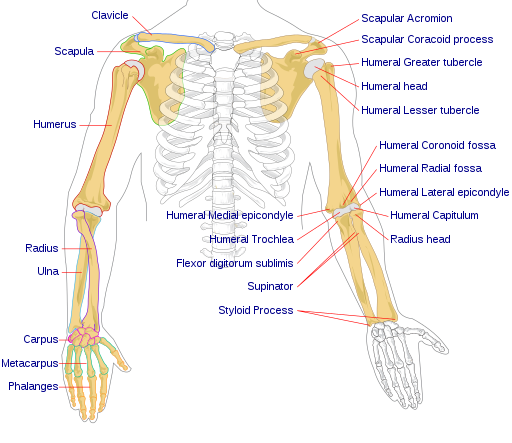

Upper Limbs

The bones of the upper limbs include the bones of the arms, wrists, and hands. The shoulder attaches the upper limbs to the axial skeleton. See Figure 10.10[13] for an illustration of the upper limbs, shoulder, clavicle, and scapula.

Arms

There are three bones in each arm:

- Humerus: Upper arm

- Radius: The thumb side of the forearm

- Ulna: The fifth finger side of the forearm

View a supplementary YouTube video[14] on the radius and the ulna from UCDenver Anatomy Lab: Radius & ulna.

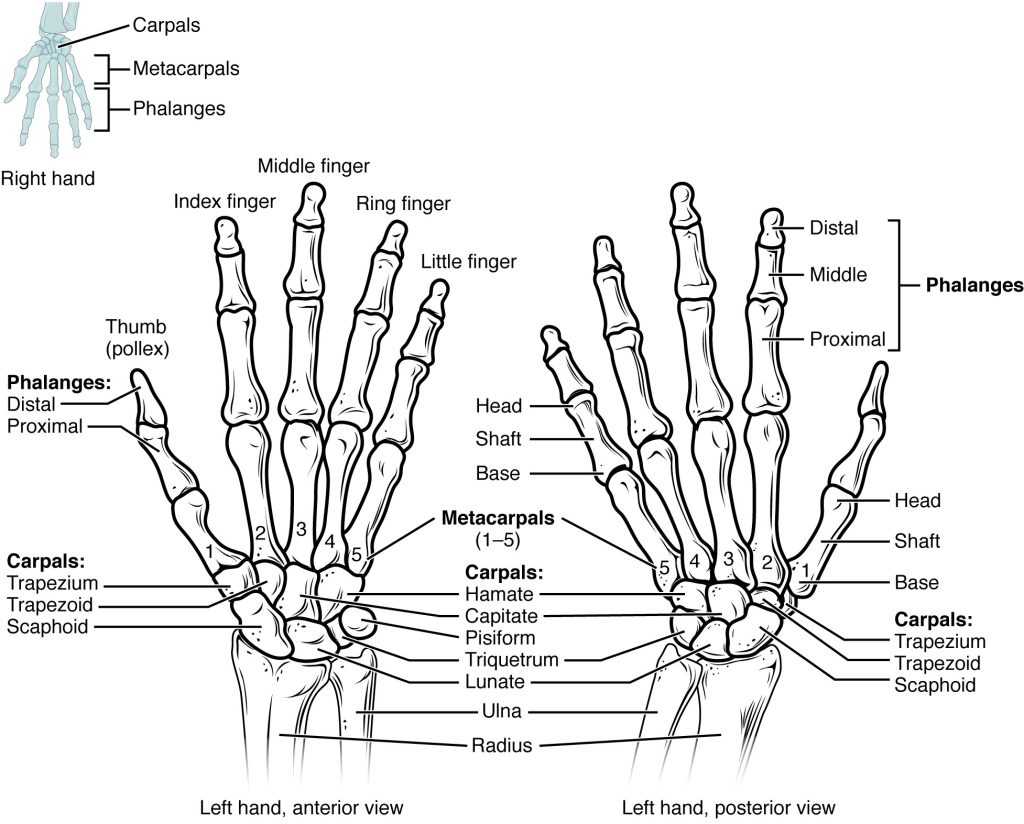

Wrists, Hands, and Fingers

See Figure 10.11[15] for an illustration of the bones of the wrist, hand, and fingers:

- Carpals: Wrist bones

- Metacarpals: Wrist bones

- Phalanges: Fingers (and toes)

A single finger is called a phalanx and is composed of three bones called the distal phalanx, medial phalanx, and proximal phalanx. The exception is the thumb, which only has two bones, the distal and proximal.

The Shoulder

Refer back to Figure 10.10 to view the bones of the shoulder that connect the arms to the axial skeleton and include the clavicle, scapula, and acromion:

- Clavicle: Connects the sternum to the scapula, also known as the collarbone

- Scapula: Shoulder blade

- Acromion: An extension from the scapula that forms the bony tip of the shoulder

Together, the clavicle, acromion, and spine of the scapula form a V-shaped bony line that provides for the attachment of neck and back muscles that act on the shoulder, as well as muscles that pass across the shoulder joint to act on the arm.

Lower Limbs

The bones of the lower limbs include bones of the leg and the feet. The hip attaches the lower limbs to the axial skeleton.

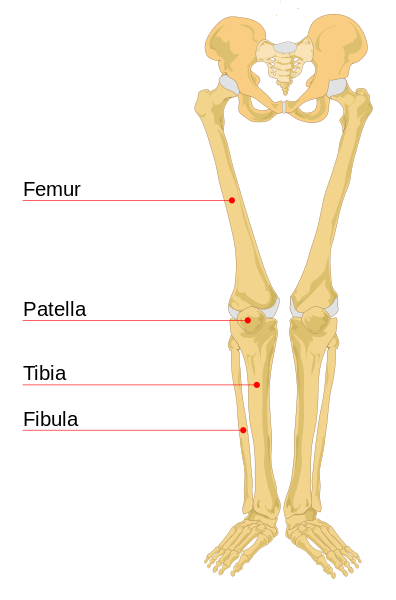

Leg

See Figure 10.12[16] for an illustration of the leg bones, including the femur, patella, tibia, and fibula:

- Femur: Thigh bone, the longest and strongest bone in the human body

- Patella: Kneecap

- Tibia: The medial bone and main weight-bearing bone of the lower leg, commonly called the shin. The distal end of the tibia forms the medial malleolus, the bony protrusion on the medial side of the ankle.

- Fibula: The smaller, lateral bone of the lower leg. The distal end of the fibula forms the lateral malleolus, the bony protrusion on the lateral side of the ankle.

Feet

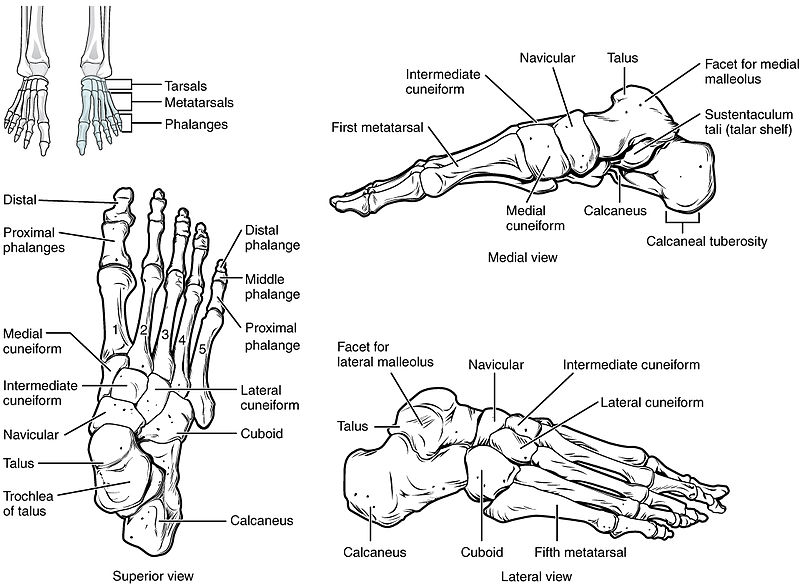

See Figure 10.13[17] for an illustration of the bones of the ankles and feet. There are several foot bones, but the major bones include the tarsals, metatarsals, phalanges, and calcaneus:

- Tarsals: Bones of the posterior half of the foot

- Metatarsals: Bones of the anterior half of the foot

- Phalanges: Toes (and fingers). The hallux is the great toe.

- Calcaneus: Heel bone

Like the fingers, the toes are composed of three bones called the distal phalanx, medial phalanx, and proximal phalanx, with the exception of the great toe, which only has two bones, the distal and proximal.

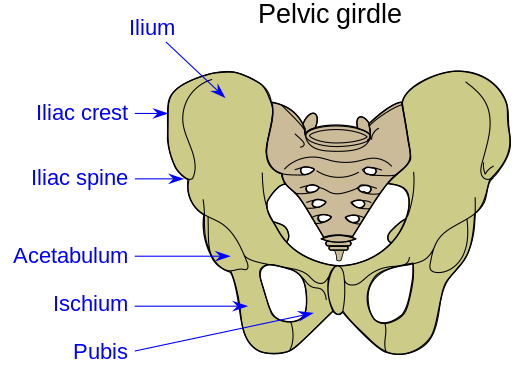

The Hip

The hip serves as the attachment point for each lower limb at the acetabulum, the large socket that holds the head of the femur. Each adult hip bone is formed by three separate pelvic bones, called the ilium, ischium, and pubis, that fuse together during the late teenage years.

The ilium is the superior region that forms the largest part of the hip bone. It is attached to the sacrum at the sacroiliac joint. The ischium forms the posteroinferior region of each hip bone and supports the body when sitting. The pubis forms the anterior portion of the hip bone. The pubis curves medially, where it joins to the pubis of the opposite hip bone at a specialized joint called the pubic symphysis. The pelvis, also referred to as the pelvic girdle, refers to this entire structure formed by the two hip bones: the sacrum and the coccyx. It surrounds the pelvic cavity and connects the vertebral column to the lower limbs.

See Figure 10.14[18] for an illustration of the hip and pelvis.

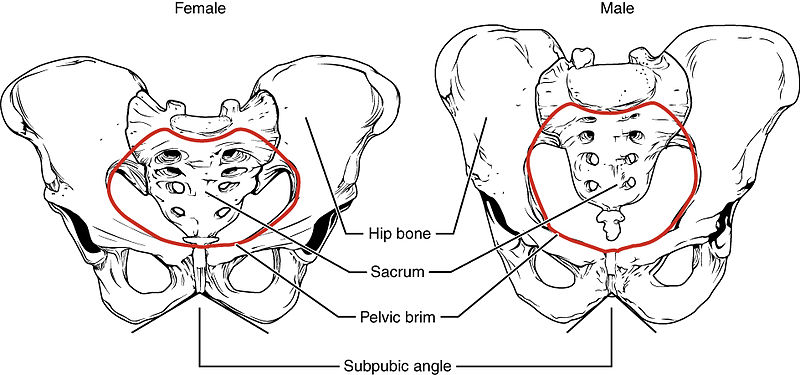

The shape of the pelvis is different for males and females. In general, the bones of the male pelvis are thicker and heavier because they have adapted to support a male’s typically heavier physical build. Because the female pelvis has adapted for childbirth, it is wider than the male pelvis. The shape and size of the pelvis can be used during forensic assessment to identify if skeletal remains are male or female. See Figure 10.15[19] for a comparison of the female and male pelvis.

Joints

Joints, also called articulations, are places where two bones or bone and cartilage come together and form a connection. Joints allow for movement and flexibility in the body. Dislocation refers to displacement of a bone from its normal position in a joint. Joints are categorized based on their structures and are referred to as fibrous joints, cartilaginous joints, or synovial joints.

Fibrous Joints

Fibrous joints are nonmoveable joints where two bones are attached by fibrous connective tissue. For example, a suture is the narrow fibrous joint found between the skull bones. During infancy, the space between skull bones is filled with flexible material that allows the skull to grow as the baby’s brain grows.

Cartilaginous Joints

Cartilaginous joints, also called amphiarthrosis or slightly movable joints, occur when two bones are connected by cartilage, a tough but flexible type of connective tissue. Examples of cartilaginous joints include the pubic symphysis and intervertebral disks.

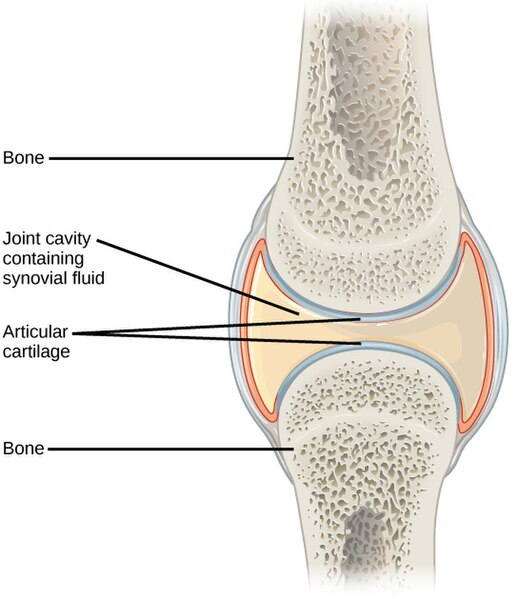

Synovial Joints

Synovial joints, also called diarthroses or fully movable joints, have a fluid-filled space where two bones come together, called a joint cavity. Because the bones in a synovial joint are not directly connected to each other with fibrous connective tissue or cartilage, they are able to move freely against each other, allowing for increased joint mobility. Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body. A synovial membrane is the lining or covering of synovial joints, and synovial fluid is the lubricating fluid found between synovial joints. See Figure 10.16[20] for an illustration of a synovial joint.

Types of Synovial Joints

Synovial joints are categorized based on the shapes of the articulating surfaces of the bones that form each joint. The six types of synovial joints are pivot, hinge, condyloid, saddle, plane, and ball-and-socket joints. See Figure 10.17[21] for an illustration of the various types of synovial joints.

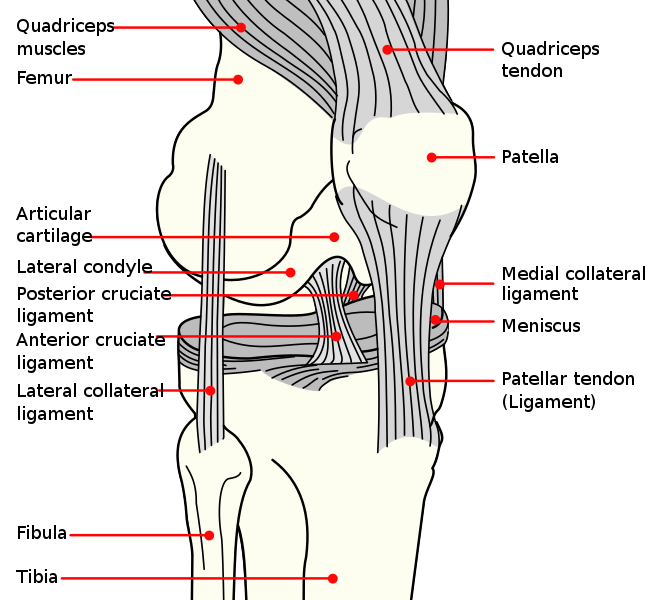

A few synovial joints have a fibrocartilage structure called an arterial disk or meniscus located between the articulating bones. Arterial disks are generally small and oval-shaped, whereas a meniscus is larger and C-shaped. For example, the knee connects the femur (upper leg bone) to the tibia (one of the lower leg bones) with a meniscus.

In addition to the meniscus, the knee also contains ligaments, tendons, and additional cartilage. Ligaments in the knee include the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). See Figure 10.18[22] for an illustration of these structures in the knee joint.

View a supplementary YouTube video[23] from Crash Course on joints: Joints: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #20.

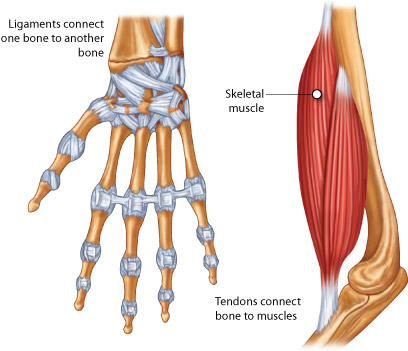

Ligaments and Tendons

Other fibrous connective tissues in the musculoskeletal system include ligaments and tendons. Ligaments are narrow bands of fibrous connective tissue that connect a bone to a bone. A tendon is narrow bands of fibrous connective tissue that connect a bone to a bone. Tendons are further discussed in the “Muscular System” subsection” below. See Figure 10.19[24] for an image that compares ligaments and tendons.

Bones

There are 206 bones in adults and 300 bones in children. As children grow, some bones fuse together to become 206 bones in adulthood.

There are three types of cells related to the growth and breakdown of bone. Osteoblasts are bone-forming cells, and osteocytes are mature bone cells. The dynamic nature of bone means that new bone tissue is constantly being formed; and old, injured, or unnecessary bone is dissolved for repair or for calcium release. The cells responsible for bone breakdown are osteoclasts. An equilibrium between osteoblasts and osteoclasts maintains healthy bone tissue. Two disorders caused by lack of equilibrium of these processes are osteopenia and osteoporosis. Osteopenia refers to abnormal reduction of bone mass, and during osteoporosis the bones become weak, brittle, and prone to fractures.

Bones contain more calcium (Ca+) than any other organ. When blood calcium levels decrease below normal levels, calcium is released from the bones by the osteoclasts, so there is an adequate supply for metabolic needs. In contrast, when blood calcium levels are increased, excess calcium is stored in bone by the osteoblasts. This dynamic process of releasing and storing calcium goes on continuously.

The bones of the skeletal system are composed of inner spongy tissue referred to as bone marrow. There are two types of bone marrow called red and yellow. Red bone marrow produces the red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Yellow bone marrow contains adipose tissue, which can serve as a source of energy.

Review additional information about bone marrow and the production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets in the “Hematological Alterations” chapter.

Muscular System

Types of Muscle

There are three major types of muscle tissue categorized as smooth, cardiac, and skeletal muscle. See Figure 10.20[25] for an illustration of these three types of muscle. Cardiac and skeletal muscles are striated, meaning they contain functional units called sarcomeres. Sarcomeres are composed of two protein filaments called actin and myosin that are responsible for muscular contraction.

Smooth Muscle

Smooth muscle is responsible for involuntary muscle movement. Smooth muscle is present in the following areas[26]:

- Walls of hollow organs, like the urinary bladder, uterus, stomach, and intestines, where muscle contractions cause the movement of fluids and other substances

- Walls of passageways, such as the arteries and veins of the circulatory system, where it causes vasodilation and vasoconstriction

- Tracts of the respiratory, urinary, and reproductive systems, where contraction and relaxation affect the movement of air, urine, and reproductive fluids

- Eyes, where it functions to change the size of the pupil

- Skin, where it causes hair to stand erect in response to cold temperature or fear, commonly called goose bumps

Cardiac Muscle

Cardiac muscle is only found in the heart. Highly coordinated contractions of cardiac muscle pump blood throughout the circulatory system. Cardiac muscle fiber cells are extensively branched and connected to one another at their ends to allow the heart to contract in a wavelike pattern and work as a pump.

Skeletal Muscle

Skeletal muscles are located throughout the body. They are under voluntary control and primarily produce movement of the arms, legs, back, and neck and maintain posture by resisting gravity. Small, constant adjustments of the skeletal muscles are needed for a person to hold their body upright or balanced in any position.

Skeletal muscles also have several additional functions. They are located throughout the body at the openings of internal tracts to control the movement of substances. These skeletal muscles allow voluntary control of functions such as swallowing, defecation, and urination in the digestive and urinary systems. Skeletal muscles also protect internal organs (particularly abdominal and pelvic organs) by acting as an external barrier against trauma and supporting the weight of the organs. They also contribute to maintaining homeostasis by generating heat. This heat generation is very noticeable during exercise, when sustained muscle movement causes a person’s body temperature to rise, or conversely during cold environmental temperatures when shivering produces random skeletal muscle contractions to generate heat. Skeletal muscles also play a role in blood flow. For example, the contraction of skeletal muscles during walking helps promote blood flow and reduces the risk of blood clot formation.

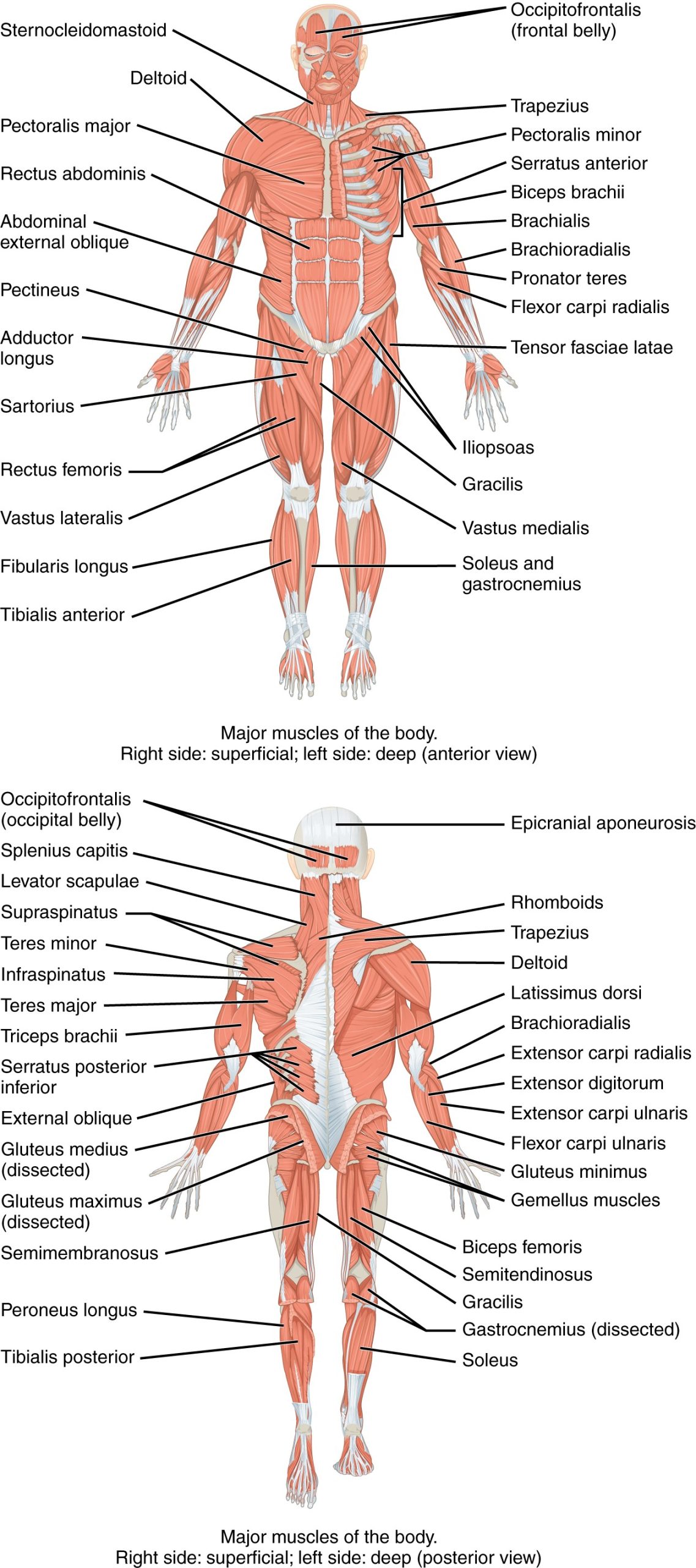

See Figure 10.21[27] for an illustration of the major skeletal muscles of the body. For the anterior and posterior views in this figure, superficial muscles are shown on the right side of the image, and deep muscles are shown on the left side of the image. For the legs, superficial muscles are shown in the anterior view while the posterior view shows both superficial and deep muscles.

Muscles are named based on various characteristics, such as the following:

- Body location: The area of the body, for example, biceps, triceps, and quadriceps

- Size: The size of the muscle, such as maximus (largest) and minimus (smallest)

- Shape: The shape of the muscle, such as deltoid (triangular) or trapezius (trapezoid)

- Action: The action of the muscle, such as flexor (i.e., to flex) or adductor (i.e., towards midline of body)

- Fiber direction: The direction of the muscle fibers, such as external oblique

Major Skeletal Muscles

Major skeletal muscles include the following:

- Biceps brachii: Muscle on the anterior upper arm

- Biceps brachialis: Muscle located in the arm that flexes the elbow joint and rotates the forearm

- Deltoid: A large triangular muscle covering the shoulder joint

- Gastrocnemius: The chief muscle of the calf of the leg

- Gluteus maximus: The largest and outermost of the three gluteal muscles in the buttocks

- Latissimus dorsi: A large muscle in the back

- Pectoralis major: A thick, fan-shaped muscle situated on the chest

- Quadriceps: A large muscle group on the front of the thigh

- Rectus abdominis: A paired muscle running vertically on each side of the anterior wall of the abdomen

- Triceps brachii: Muscle on the posterior of the upper arm

Tendons

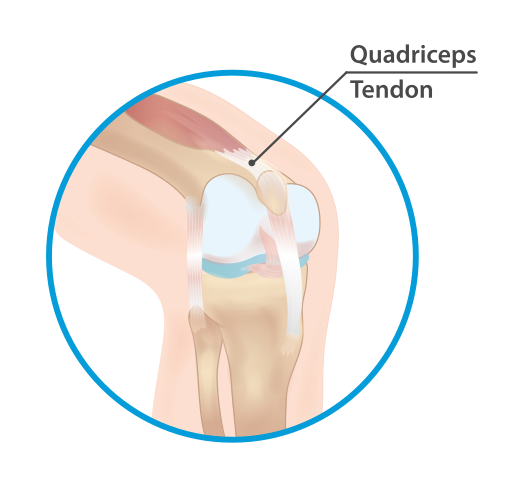

As previously mentioned in “The Appendicular Skeletal” subsection, tendons attach muscles to bones. For example, consider the Achilles tendon, hamstring, rotator cuff, and quadriceps tendons. The Achilles tendon attaches the calf muscles to the heel bone. The hamstring refers to five tendons at the back of a person’s knee that connect a group of three hamstring muscles to bones in the pelvis, knee, and lower leg. The rotator cuff is a group of muscles and tendons that stabilize the shoulder. The quadriceps tendon attaches the quadriceps muscle to the top of the kneecap. See Figure 10.22[28] for an illustration of the quadriceps tendon.

Function of Muscles

The main function of the muscular system is movement. Muscles work as antagonistic (opposing) pairs. As one muscle contracts, another muscle relaxes. This contraction pulls on the bones and assists with movement. Contraction is the shortening of muscle fibers whereas relaxation is the lengthening of fibers. This sequence of relaxation and contraction is stimulated by the nervous system.

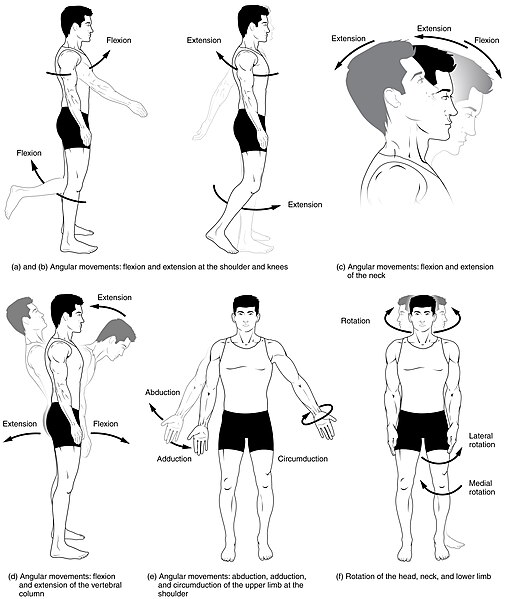

There are many types of actions that are caused by the contraction and relaxation of muscles, such as flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, rotation, dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, supination, and pronation. These muscle actions are summarized in Table 10.2. See Figures 10.23[29] and 10.24[30] for illustrations of these movements.

Table 10.2. Muscle Actions

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Flexion | Movement that decreases the angle between two bones, such as bending the arm at the elbow. |

| Extension | Movement that increases the angle between two bones, such as straightening the arm at the elbow. |

| Abduction | Movement of a limb away from the midline of the body. |

| Adduction | Movement of a limb toward the midline of the body. |

| Rotation | Circular movement around a central point. Internal rotation is toward the center of the body, and external rotation is away from the center of the body. |

| Dorsiflexion | Decreasing the angle of the foot and the leg (i.e., the foot moves upward toward the knee). This movement is the opposite of plantar flexion. |

| Plantar Flexion | Increasing the angle of the foot and leg (i.e., the moves foot downward toward the ground, such as when pressing down on a gas pedal in a car). |

| Supination | Movement of the hand or foot turning upward. When applied to the hand, it is the act of turning the palm upwards. When applied to the foot, it is the outward roll of the foot/ankle during normal movement. |

| Pronation | Movement of the hand or foot turning downward. When applied to the hand, it is the act of turning the palm downward. When applied to the foot, it is the inward roll of the foot/ankle during normal movement. |

| Eversion | Excessive movement when turning outward the sole of the foot away from the body’s midline, a common cause of an ankle sprain. |

| Inversion | Excessive movement when turning inward the sole of the foot towards the median plane, a common cause of an ankle sprain. |

- National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Introduction to the skeletal system. National Institutes of Health. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/anatomy/skeletal ↵

- “701 Axial Skeleton-01.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e ↵

- “704_Skull-01.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is derivative of “Occipital_bone_lateral4.png” by Anatomography is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.1 ↵

- “Hyoid Bone” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/7-2-the-skull ↵

- “718_Vertebra-en.svg” by Jmarchn is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Vertebral Column” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/7-3-the-vertebral-column ↵

- “Sacrum_-_anterior_view02.png” by BodyParts3D, made by DBCLS is licensed under CC BY 2.1 Japan ↵

- “Coccyx_-_anterior_view01.png” by BodyParts3D, made by DBCLS is licensed under CC BY 2.1 Japan ↵

- “721_Rib_Cage.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e ↵

- “Human_arm_bones_diagram.svg” by LadyofHats Mariana Ruiz Villarreal is licensed in the Public Domain ↵

- UCDenver Anatomy Lab 3244. (2014, August 31). Radius & ulna [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ThmvWFvHOmI ↵

- “541c7cf2586e9daaea40767bbc68011fdb8573b1.jpg" OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/8-2-bones-of-the-upper-limb ↵

- “Human_leg_bones_labeled.svg” by LadyofHats Mariana Ruiz Villarreal is licensed in the Public Domain ↵

- “812_Bones_of_the_Foot.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Pelvic_girdle_illustration.svg” by Fred the Oyster is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “809_Male_Female_Pelvic_Girdle.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Figure_38_03_03.jpg” by CNX OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “909_Types_of_Synovial_Joints.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Knee_diagram.svg” by Mysid is licensed in the Public Domain ↵

- CrashCourse. (2015, May 26). Joints: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #20 [Video]. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLxYDoN634c ↵

- “tendon-lig.jpg” by unknown author is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.ccconline.org/bio106 ↵

- “Types_Of_Muscle.jpg” by www.scientificanimations.com is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e ↵

- “1105_Anterior_and_Posterior_Views_of_Muscles.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Quadriceps_tendon.svg” by InjuryMap is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Body_Movements_I.jpg” by Tonye Ogele CNX is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Body_Movements_II.jpg” by Tonye Ogele CNX is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2021, March 3). Flexion and extension anatomy: Shoulder, hip, forearm, neck, leg, thumb, wrist, spine, finger [Video]. YouTube. Used with permission. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4xbehGmkmk ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2021, March 29). Abduction and adduction of wrist, thigh, fingers, thumb, arm | Anatomy body movement terms [Video]. YouTube. Used with permission. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcxE9uql8g4 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2021, January 11). Inversion and eversion of the foot, ankle | Anatomy body movement terms [Video]. YouTube. Used with permission. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/4HuxLWQykxk?feature=shared. ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, December 29). Dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of foot | Anatomy body movement terms [Video]. YouTube. Used with permission. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e6WugOzgFIM ↵

- Dr. Matt & Dr. Mike. (2021, February 7). Joint movements [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tAJjXvumL7E ↵

As discussed in the previous sections, professional liability occurs when a civil lawsuit compensates patients who allege they have suffered injury or damage as a result of professional negligence. Many nurses elect to purchase malpractice insurance to protect themselves from professional liability, especially if working in specialty areas that experience a high number of claims, such as in obstetrics or post-anesthesia care units (PACUs). The Nursing Service Organization (NSO) works in association with the American Nurses Association to provide malpractice insurance for nurses interested in purchasing it.

Read more about malpractice insurance available for nurses at https://www.nso.com/.

The civil justice system cannot make rulings regarding your nursing license. It is the responsibility of the State Board of Nursing to suspend or revoke an individual’s nursing license based on a disciplinary process.

The State Board of Nursing (SBON) governs nursing practice according to that state’s Nurse Practice Act. The purpose of the SBON is to protect the public through licensure, education, legislation, and discipline. A nursing license is a contract between the state and licensee in which the licensee agrees to provide nursing care according to that state's Nurse Practice Act. Deviation from the Nurse Practice Act is a breach of contract that can lead to limited or revoked licensure. The SBON can suspend or revoke an individual’s nursing license to protect the public from unsafe nursing practice. Nursing scope of practice and standards of nursing care are defined in the Nurse Practice Act that is enacted by the state legislature and enforced by the SBON. Nurses must practice according to the Nurse Practice Act of the state in which they are providing client care.

A nurse may be named in a board licensing complaint, also called an allegation. Allegations can be directly related to a nurse’s clinical responsibilities, or they can be nonclinical (such as substance abuse, unprofessional behavior, or billing fraud). A complaint can be filed against a nurse by anyone, such as a patient, a patient's family member, a colleague, or an employer. It can be filed anonymously. After a complaint is filed, the SBON follows a disciplinary process that includes investigation, proceedings, board actions, and enforcement. The process can take months or years to resolve, and it can be costly to hire legal representation.[1]

During the investigation process, investigators use various methods to determine the facts, such as interviewing parties who were present, reviewing documentation and records, performing drug screens (if impairment is alleged), and compiling pertinent facts related to the events and circumstances surrounding the complaint. Nurses being investigated may receive a letter, email, or phone call from the SBON, or they may be required to appear at a certain date and time for an interview with an investigator. It is recommended that nurses consult with an attorney before responding to the SBON within the deadline provided. Nurses should be cooperative but should be aware that whatever is shared will be provided to a prosecuting attorney and/or the SBON.[2]

After completion of the investigation, the prosecuting attorney will determine how to proceed. A conference may be scheduled where the nurse will be interviewed by a member of the SBON and possibly the prosecuting attorney. It is recommended for the nurse to have an attorney present during proceedings. The nurse has the opportunity to present evidence supporting their case. A resolution may be offered after the conference that ends the matter.[3]

However, if the SBON believes there is significant evidence, a formal hearing is held where a disciplinary action is proposed. This formal hearing is similar to a civil trial. The hearing panel may include some or all of the SBON members. A court reporter records the entire proceeding and a transcript is created. Witnesses may be called to testify and the nurse undergoes cross-examination. When both sides have presented their cases, the hearing is concluded. The outcome of the formal hearing is a ruling by the administrative law judge and the SBON. The nurse may face disciplinary action such as a reprimand, limitation, suspension, or revocation of their license. Nondisciplinary actions, such as a warning or a remedial education order, may be set. See a description of possible disciplinary actions enforced by the Wisconsin State Board of Nursing in Table 5.3a.

Table 5.3a. Potential Disciplinary and Nondisciplinary Actions of the Wisconsin State Board of Nursing[4]

| Disciplinary Options

|

Reprimand: The licensee receives a public warning for a violation.

Limitation of License: The licensee has conditions or requirements imposed upon their license, their scope of practice, or both. Suspension: The license is completely and absolutely withdrawn and withheld for a period of time, including all rights, privileges, and authority previously conferred by the credential. Revocation: The license is completely and absolutely terminated, as well as all rights, privileges, and authority previously conferred by the credential. |

|---|---|

| Nondisciplinary Options | Administrative Warning: A warning is issued if the violation is of a minor nature or a first occurrence, and the warning will adequately protect the public. The issuance of an administrative warning is public information; however, the reason for issuance is not.

Remedial Education Order: A remedial education order is issued when there is reason to believe that the deficiency can be corrected with remedial education, while sufficiently protecting the public. |

Find and review your state's Nurse Practice Act at https://www.ncsbn.org/policy/npa.page.

Read more about Wisconsin’s Board of Nursing and Administrative Code.

Liability considerations does not only apply when working in your professional nursing role, but also within your student nurse role. As you work as a student nurse, there are other role considerations which may impact the decision regarding professional liability. Please see Table 5.3b for a comparison of different types of liability.

5.3b. Types of Liability

| Type of Liability | Definition | Example |

| Supervisory Liability[5] | When a clinical supervisor or preceptor is held responsible for the actions of the student nurse or for failing to properly supervise them. | A clinical supervisor fails to provide proper guidance during a procedure, resulting in the student nurse administering the wrong medication to a patient. The supervisor could be held liable for inadequate supervision. |

| Institutional Liability[6] | When the health care institution (e.g., hospital, clinic) is held responsible for the actions of its employees or for failing to implement adequate policies and procedures to prevent harm. | A hospital does not provide proper orientation or training programs for student nurses, leading to a student nurse making a critical error. The hospital could be held liable for not ensuring adequate training. |

| Student Liability[7] | When the student nurse is held responsible for their own actions that cause harm to patients or violate protocols. | A student nurse neglects to follow infection control protocols, resulting in a patient's condition worsening. The student nurse could be held liable for their negligence. |

The Nurses Service Organization (NSO) reported the three most common allegations resulting in state board investigations in 2020 were related to the categories of professional conduct, scope of practice, and documentation errors or omissions.[8]

Professional Conduct

Common allegations related to professional conduct included drug diversion and substance abuse, professional misconduct, reciprocal actions, and wastage errors.

Drug Diversion and Substance Abuse

The most common allegations related to professional conduct for both RNs and LPN/VNs in 2020 were related to drug diversion and/or substance abuse. Examples include diverting medications for oneself or others and apparent intoxication from alcohol or drugs while on duty.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) created a brochure titled Substance Abuse Disorder in Nursing to address this common issue.[9] Many states have programs in place to assist nurses with substance abuse, such as Wisconsin Nursing Association's Nurses Caring for Nurses (Peer Assistance) program or New York State Nursing Association's Statewide Peer Assistance for Nurses (SPAN) program.[10],[11]

Professional Misconduct

Professional misconduct as defined by state regulations was the second most common allegation related to professional conduct. This category includes unprofessional conduct towards coworkers and patients, as well as allegations of falling asleep.

Sample Case

Sample CaseA home health RN was assigned to monitor an 11-month-old child from 1900 to 0700. The child was intubated and required constant monitoring to ensure the tubing remained secure while she was in her crib. However, the child’s father found the RN sleeping and the child’s tubing unsecured. The child did not suffer harm due to the incident, but the SBON publicly reprimanded the RN, and the costs to defend the nurse exceeded $2,400.[12]

Reciprocal Actions

The third most common professional conduct allegation was reciprocal actions. Many cases involved nurses who were trying to contend with patients who were violent or aggressive and either retaliated against the patient or responded to the patient ‘s aggression in an inappropriate or unprofessional manner.

Sample Case

Sample CaseA patient in an inpatient behavioral health unit became agitated, pulled a phone out of the wall, and threw it. The nurse entered the room and following a brief interaction, an altercation between the patient and the nurse ensued. The nurse received a public reprimand and disciplinary actions from the SBON.[13]

Wastage Errors

Wastage errors were the fourth most common allegation. Wastage errors occurred when nurses neglected to perform accurate medication counts or did not appropriately document proper disposal of opioids and other drugs with a high potential for abuse.

Sample Case

Sample CaseAn RN left two 15 milligram tablets of a benzodiazepine called Temazepam unattended in an area accessible to patients. The medication went missing and was apparently taken by a patient. The nurse falsely documented the Temazepam as wastage, knowing the medication was actually missing. The SBON issued a $200 fine, and expenses to defend the nurse exceeded $7,200.[14]

Scope of Practice

Common allegations related to scope of practice include failure to maintain a minimum standard of practice and providing services beyond one’s scope of practice.

Failure to Maintain Minimum Standard of Nursing Practice

The most common allegations related to scope of practice include failure to maintain a minimum standard of nursing practice. These cases include a breach of minimum professional standards, incompetence, and negligence.

Sample Case

Sample CaseA nurse working in home health failed to complete required patient assessments and omitted pertinent patient information in the health care record. This omission could have caused a disruption in the continuity of treatment resulting in patient harm. The SBON determined the nurse failed to exercise the degree of learning, skill, care, and experience ordinarily possessed and exercised by a competent RN. The SBON placed the nurse on probation for three years, and the expenses associated with defending the nurse exceeded $5,400.[15]

Sample Case

Sample CaseAn RN failed to follow agency policy and procedures by neglecting to properly verify identification of two patients and omitting the review of relevant laboratory results. As a result of bypassing standard safety procedures, the RN gave an extra unit of blood to one patient that was intended for the other patient, thereby depriving that patient the extra unit of blood required based on her lab results. The SBON placed the nurse on probation for three years. However, the nurse did not comply with the terms of her probation by failing to report to the SBON when she applied for licensure in two other states. The nurse also failed to obtain approval prior to commencing employment. The nurse was ultimately ordered to surrender her license.[16]

Sample Case

Sample CaseA student nurse was instructed to discontinue an intravenous (IV) antibiotic for a patient with a central venous catheter. When the student discontinued the IV, she unknowingly loosened the catheter connection from the lumen luer connector. The loosened line would likely have been discovered when the line was flushed per agency policy, but the student testified she did not know she was supposed to flush the catheter line or clamp it after the medication was discontinued. Shortly thereafter, the patient became unresponsive, and a code was called. The disconnection was not discovered until the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit three hours later. The patient experienced an air embolism and died. A malpractice claim was awarded.[17]

Provision of Services Beyond Scope of Practice

The second most common allegation related to scope of practice is provision of services beyond one’s scope of practice. This category typically involves nurses making changes to patients’ prescribed treatments or administering medication that had not been prescribed.

Sample Case

Sample CaseAn RN in the ICU was caring for a patient with extreme nausea. The nurse made several unsuccessful attempts to reach the provider for an order for Ondansetron. The nurse called the pharmacy and relayed her concern for the patient’s nausea and her inability to reach the provider. The nurse informed the pharmacist that she believed the situation was urgent, and she would contact the provider for an order. The pharmacy dispensed Ondansetron and the nurse administered the medication. Although the patient did not suffer adverse effects from the medication, no order was ever received for the medication. Upon finding the RN violated the Nurse Practice Act by practicing beyond the scope of practice for an RN, the SBON publicly reprimanded the nurse and ordered her to pay a fine of $600. Expenses associated with defending the nurse exceeded $6,100.[18]

Documentation

Over half of the allegations in 2020 regarding documentation were related to fraudulent or falsified patient care or billing records. The health care record is a legal document. It should never be altered, deleted, or falsified. Maintaining accurate and timely documentation is a primary professional responsibility of nurses.

Sample Case

Sample CaseIn a case involving a nursing student, the preceptor instructed the student to monitor the patient’s vital signs every 15 minutes for one hour and then every 30 minutes for two hours and then every hour for four hours. The student allegedly documented vital signs every 15 minutes for one hour but did not record any vital signs thereafter. When confronted by her preceptor about the incomplete record, the student stated that she “forgot to do them.” Approximately 30 minutes later, the preceptor discovered the missing vital signs were documented in the patient’s record. The preceptor asked the student about the entries, and the student replied that she “made them up.” The student later contended that she meant she charted the vital signs accurately but made up the times the vital signs were taken to match the preceptor’s instructions. The SBON considered the student was still learning but viewed documentation as a basic nursing skill. Because the student’s conduct involved dishonesty, they imposed a penalty of a one-year suspension followed by one year of probation. The expenses associated with defending the student nurse exceeded $6,900.[19]

Professional Misconduct Case Study Scenario

Sarah is a registered nurse working in a busy hospital emergency department. One evening, she is assigned to care for Mr. Thompson, a 68-year-old man who was admitted with severe chest pain. The emergency department is understaffed, and Sarah is handling multiple patients at once.

During her shift, Sarah receives a call from her supervisor asking her to assist in another critical case. In her hurry to attend to the other patient, Sarah administers Mr. Thompson's medication without double-checking the doctor's orders. Unfortunately, she administers the wrong dosage of a medication, causing Mr. Thompson's condition to worsen significantly.

Upon realizing her mistake, Sarah panics and decides not to report the error to avoid potential disciplinary action. She adjusts Mr. Thompson's medical record to conceal the mistake. Later, Mr. Thompson's condition deteriorates further, requiring intensive care. An investigation reveals the medication error and the altered medical records.

- Identify the ethical and legal issues present in this case.

- How does Sarah's behavior constitute professional misconduct?

- What are the potential consequences for Sarah, both professionally and legally?

- How might the lack of adequate staffing and supervision have contributed to this incident?

- What policies should the hospital have in place to prevent such errors and ensure proper reporting?

- How did Sarah's actions affect Mr. Thompson's safety and overall outcome?

- What impact might this incident have on the trust between health care professionals and patients?

You have worked hard to obtain a nursing license and it will be your livelihood. See Figure 5.7[20] for an illustration of a nursing license. Protecting your nursing license is vital.

Actions to Protect Your License

There are several actions that nurses can take to protect their nursing license, avoid liability, and promote patient safety. See Table 5.5 for a summary of recommendations.

Table 5.5 Risk Management Recommendations to Protect Your Nursing License

| Legal Issues | Recommendations to Protect Your License |

|---|---|

| Practicing outside one’s scope of practice |

|

| Failure to assess & monitor |

|

| Documentation |

|

| Medication errors |

|

| Substance abuse and drug diversion |

|

| Acts that may result in potential or actual client harm |

|

| Safe-guarding client possessions & valuables |

|

| Adherence to mandatory reporting responsibilities |

|

Culture of Safety

It can be frightening to think about entering the nursing profession after becoming aware of potential legal actions and risks to your nursing license, especially when realizing even an unintentional error could result in disciplinary or legal action. When seeking employment, it is helpful for nurses to ask questions during the interview process regarding organizational commitment to a culture of safety to reduce errors and enhance patient safety.

Many health care agencies have adopted a culture of safety that embraces error reporting by employees with the goal of identifying root causes of problems so they may be addressed to improve patient safety. One component of a culture of safety is "Just Culture." Just Culture is culture where people feel safe raising questions and concerns and report safety events in an environment that emphasizes a nonpunitive response to errors and near misses. Clear lines are drawn between human error, at-risk, and reckless behaviors. [27]

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture. They stated that while our traditional health care culture held individuals accountable for all errors and accidents that happened to patients under their care, the Just Culture model recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. The Just Culture model also recognizes that many errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, the Just Culture model does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to patients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).[28]

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three categories of errors: simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. Consequences of errors are based on these categories.[29] When seeking employment, it is helpful for nurses to determine how an agency implements a culture of safety because of its potential impact on one’s professional liability and licensure.

Read more about the Just Culture model in the "Basic Concepts" section of the "Leadership and Management" chapter.

In addition to being aware of the legal and regulatory frameworks in which one practices nursing, it is also important for nurses to understand the legal concepts of informed consent and advance directives.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is the fundamental right of a client to accept or reject health care. Nurses have a legal responsibility to provide verbal and/or written information and obtain verbal or written consent for performing nursing care such as bathing, medication administration, and urinary or intravenous catheter insertion. While physicians have the responsibility to provide information and obtain informed consent related to medical procedures, nurses are typically required to verify the presence of a valid, signed informed consent before the procedure is performed. Additionally, if nurses do not believe the patient has adequate understanding of a procedure, its risks, benefits, or alternatives to treatment, they should request the provider return to clarify unclear information with the client. Nurses must remain within their scope of practice related to informed consent beyond nursing acts.

Two legal concepts related to informed consent are competence and capacity. Competence is a legal term defined as the ability of an individual to participate in legal proceedings. A judge decides if an individual is “competent” or “incompetent.” In contrast, capacity is “a functional determination that an individual is or is not capable of making a medical decision within a given situation.”[30] It is outside the scope of practice for nurses to formally assess capacity, but nurses may initiate the evaluation of client capacity and contribute assessment information. States typically require two health care providers to identify an individual as “incapacitated” and unable to make their own health care decisions. Capacity may be a temporary or permanent state.

The following box outlines situations where the nurse may question a client's decision-making capacity.

| Triggers for Questioning Capacity and Decision-Making[31] |

|---|

|

If an individual has an advance directive in place, their designated power of attorney for health care may step in and make medical decisions when the client is deemed incapacitated. In the absence of advance directives, the legal system may take over and appoint a guardian to make medical decisions for an individual. The guardian is often a family member or friend but may be completely unrelated to the incapacitated individual. Nurses are instrumental in encouraging a client to complete an advance directive while they have capacity to do so.

Advance Directives

The Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) is a federal law passed by Congress in 1990 following highly publicized cases involving the withdrawal of life-supporting care for incompetent individuals. (Read more about the Karen Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terri Shaivo cases in the boxes at the end of this section.) The PSDA requires health care institutions, such as hospitals and long-term care facilities, to offer adults written information that advises them "to make decisions concerning their medical care, including the right to accept or refuse medical or surgical treatment and the right to formulate, at the individual's option, advance directives.”[32] Advanced directives are defined as written instructions, such as a living will or durable power of attorney for health care, recognized under state law, relating to the provision of health care when the individual is incapacitated. The PSDA allows clients to record their preferences about do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment. In the absence of a client’s advance directives, the court may assert an “unqualified interest in the preservation of human life to be weighed against the constitutionally protected interests of the individual.”[33] For this reason, nurses must educate and support the communities they serve regarding the creation of advanced directives.

Advanced directives vary by state. For example, some states allow lay witness signatures whereas some require a notary signature. Some states place restrictions on family members, doctors, or nurses serving as witnesses. It is important for individuals creating advance directives to follow instructions for state-specific documents to ensure they are legally binding and honored.

Advance directives do not require an attorney to complete. In many organizations, social workers or chaplains assist individuals to complete advance directives following referral from physicians or nurses. Clients should review and update their documents every 10-15 years, as well as with changes in relationship status or if new medical conditions are diagnosed.

Although advanced directive documents vary by state, they generally fall into two categories, referred to as a living will or durable power of attorney for healthcare.

Living Will

A living will is a type of advance directive in which an individual identifies what treatments they would like to receive or refuse if they become incapacitated and unable to make decisions. In most states, a living will only goes into effect if an individual meets specific medical criteria.[34] The living will often includes instructions regarding life-sustaining measures, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), mechanical ventilation, and tube feeding.

Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare

It is impossible for an individual to document their preferences in a living will for every conceivable medical scenario that may occur. For this reason, it is essential for individuals to complete a durable power of attorney for healthcare. A durable power of attorney for healthcare (DPOAHC) is a person chosen to speak on one’s behalf if one becomes incapacitated. Typically, a primary health care power of attorney (POA) is identified with an alternative individual designated if the primary POA is unable or unwilling to do so. The health care POA is expected to make health care decisions for an individual they believe the person would make for themselves, based on wishes expressed in a living will or during previous conversations.[35]

It is essential for nurses to encourage clients to complete advance directives and have conversations with their designated POA about health care preferences, especially related to possible traumatic or end-of-life events that could require medical treatment decisions. Nurses can also dispel common misconceptions, such as these documents give the health care POA power to manage an individual’s finances. (A financial POA performs different functions than a health care POA and should be discussed with an attorney.)

After the advance directives are completed and included in the client’s medical record, the nurse has the responsibility to ensure they are appropriately incorporated into their care if they should become incapacitated.

View state-specific advance directives at the American Association of Retired Persons website.

Karen Ann Quinlan is an important figure in the United States’ history of defining life and death, a client’s privacy, and the state’s interest in preserving life and preventing murder. In April 1975, Karen Quinlan was 21 years old and became unresponsive after ingesting a combination of valium and alcohol while celebrating a friend’s birthday. She experienced respiratory failure, and although resuscitation efforts were successful, she suffered irreversible brain damage. She remained in a persistent vegetative state and became ventilator dependent. Her parents requested her physicians discontinue the ventilator because they believed it constituted extraordinary means to prolong her life. Her physicians denied their request out of concern of possible homicide charges based on New Jersey’s law. The Quinlans filed the first “right to die” lawsuit in September of 1975 but were denied by the New Jersey Superior Court in November. In March of 1976, the New Jersey Supreme Court determined the parent’s right to determine Karen’s medical treatment exceeded that of the state. Karen was discontinued from the ventilator six weeks later. When taken off the ventilator, Karen shocked many by continuing to breathe on her own. She lived in a coma for nine more years and succumbed to pneumonia on June 11, 1985.

-

- Sample Case: Nancy Beth Cruzan[37]

Nancy Cruzan is another important figure in the history of US “right to die” legal cases. At the age of 25, Nancy Cruzan was in a car accident on January 11, 1983. She never regained consciousness. After three years in a rehabilitation hospital, her parents began an eight-year battle in the courts to remove Nancy’s feeding tube. Nancy’s case was the first “right to die" case heard by the United States Supreme Court. Beyond allowing for the discontinuation of Nancy’s feeding tube, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all adults have the right to the following:1) Choose or refuse any medical or surgical intervention, including artificial nutrition and hydration.

2) Make advance directives and name a surrogate to make decisions on their behalf.

3) Surrogates can decide on treatment options even when all concerned are aware that such measures will hasten death, as long as causing death is not their intent.Nancy died nine days after removal of her feeding tube in December 1990. As a result of the Cruzan decision, the Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) was passed and took effect December 1, 1991. The act requires facilities to inform clients about their right to refuse treatment and to ask if they would like to prepare an advance directive.

- Sample Case: Nancy Beth Cruzan[37]

Sample Case: Terri Schaivo[38]

The Terri Schaivo case is a key case in history of advance directives in the United States because of its focus on the importance of having written advance directives to prevent family animosity, pain, and suffering. In 1990 Terri Schaivo was 26 years old. In her Florida home, she experienced a cardiac arrest thought to be a function of a low potassium level resulting from an eating disorder. She experienced severe anoxic brain injury and entered a persistent vegetative state. A PEG tube was inserted to provide medications, nutrition, and hydration. After three years, her husband refused further life-sustaining measures on her behalf, based on a statement Terri had once made, stating, “I don't want to be kept alive on a machine.” He expressed interest in obtaining a DNR order, withholding antibiotics for a urinary tract infection, and ultimately requested removal of the PEG tube. However, Terri’s parents never accepted the diagnosis of persistent vegetative state and vigorously opposed their son-in-law's decision and requests. Seven years of litigation generated 30 legal opinions, all supporting Michael Schiavo's right to make a decision on his wife's behalf. Terri died on March 31, 2005, following removal of her feeding tube.

Sara is a new graduate nurse orienting on the medical floor at a large teaching hospital. She has been working on the floor for two weeks and notices that many of the nurses provide shift handoff reports to one another outside of the patient rooms. Sara asks her preceptor why the nurses stand and report patient care information in the hallway. Her preceptor responds that this is the standard way staff can meet the agency guidelines for beside handoff reporting without "disturbing" patients while they are resting. Sara has concerns about this action on many levels. What legal repercussions might this "hallway reporting" have?

Sara is smart to identify that discussing patient care information in a hallway outside of patient rooms may jeopardize patient HIPAA protections and confidentiality. Sensitive patient information should never be discussed freely where others may overhear care information and details. Additionally, the act of bedside handoff reporting is meant to provide an inclusive environment for patients to participate with care staff in the report and information exchange. Discussing report details outside of the patient room does not actively include the patient in the bedside reporting procedure.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activities are provided as immediate feedback.)

- In 2006 Nurse Julie Thao was charged with felony criminal negligence in the death of a 16-year-old laboring mother when she mistakenly hung a bag of epidural medication instead of intravenous penicillin. Although the baby was successfully delivered via cesarean section, the client died following aggressive resuscitation attempts as a result of circulatory collapse. Nurse Thao was fired from her job of 16 years. Her felony charge was amended to two misdemeanor counts, and her state’s Board of Nursing suspended her license, imposed practice limitations upon return, mandated completion of an education program, and imposed a $2,500 fine. Beyond these sanctions, she stated at her sentencing hearing, “The anguish and remorse are a life sentence that will serve for all time.”

View the Chasing Zero Documentary on YouTube[39]

Discuss factors that contributed to Nurse Julie Thao’s medication error. What reflections on your own nursing practice can be made after viewing this video clip? What actions might have been taken to avoid this error? Do you believe other members of the health care team were culpable in their actions?

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[40]

Administrative law: Law made by government agencies that have been granted the authority to pass rules and regulations. For example, each state’s Board of Nursing is an example of administrative law.

Advanced directives: Written instruction, such as a living will or durable power of attorney for health care, recognized under state law, relating to the provision of health care when the individual is incapacitated.

Assault: Intentionally putting another person in reasonable apprehension of an imminent harmful or offensive contact.[41]

Battery: Intentional causation of harmful or offensive contact with another's person without that person's consent.[42]

Capacity: A functional determination that an individual is or is not capable of making a medical decision within a given situation.

Civil law: Law focusing on the rights, responsibilities, and legal relationships between private citizens.

Commission: Doing something a reasonable nurse would not have done.[43]

Competence: In a legal sense, the ability of an individual to participate in legal proceedings. A judge decides if an individual is “competent” or “incompetent.”

Confidentiality: The right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information kept private.

Constitutional law: The rights, privileges, and responsibilities established by the U.S. Constitution. For example, the right to privacy is a right established by the constitution.

Contracts: Binding written, verbal, or implied agreements.

Crime: A type of behavior defined by Congress or state legislature as deserving of punishment.

Criminal law: A system of laws concerned with punishment of individuals who commit crimes.

Culture of safety: Culture that embraces error reporting by employees with the goal of identifying root causes of problems so they may be addressed to improve patient safety.

Defamation of character: An act of making negative, malicious, and false remarks about another person to damage their reputation. Slander is spoken defamation and libel is written defamation.

Defendants: The parties named in a lawsuit.

Durable power of attorney for healthcare (DPOAHC): Person chosen to speak on one’s behalf if one becomes incapacitated.

Duty of reasonable care: Legal obligations nurses have to their patients to adhere to current standards of practice.

Ethics: A system of moral principles that a society uses to identify right from wrong.

False imprisonment: An act of restraining another person causing that person to be confined in a bounded area. Restraints can be physical, verbal, or chemical.

Felonies: Serious crimes that cause the perpetrator to be imprisoned for greater than one year.

Fraud: An act of deceiving an individual for personal gain.

Good Samaritan Law: State law providing protections against negligence claims to individuals who render aid to people experiencing medical emergencies outside of clinical environments.

Informed consent: The fundamental right of a client to accept or reject health care.

Infractions: Minor offenses, such as speeding tickets, that result in fines but not jail time.

Institutional liability: When the healthcare institution (e.g., hospital, clinic) is held responsible for the actions of its employees or for failing to implement adequate policies and procedures to prevent harm.

Intentional tort: An act of commission with the intent of harming or causing damage to another person. Examples of intentional torts include assault, battery, false imprisonment, slander, libel, and breach of privacy or client confidentiality.

Laws: Rules and regulations created by society and enforced by courts, statutes, and/or professional licensure boards.

Libel: Written defamation.

Living will: A type of advance directive in which an individual identifies what treatments they would like to receive or refuse if they become incapacitated and unable to make decisions.

Malpractice: A specific term used for negligence committed by a professional with a license.

Misdemeanors: Less serious crimes resulting in fines and/or imprisonment for less than one year.

Negligence: The failure to exercise the ordinary care a reasonable person would use in similar circumstances. Wisconsin civil jury instruction states, “A person is not using ordinary care and is negligent, if the person, without intending to do harm, does something (or fails to do something) that a reasonable person would recognize as creating an unreasonable risk of injury or damage to a person or property.”[44]

Omission: Not doing something a reasonable nurse would have done.[45]

Plaintiff: The person bringing the lawsuit.

Private law: Laws that govern the relationships between private entities.

Protected Health Information (PHI): Individually identifiable health information and includes demographic data related to the individual’s past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition; the provision of health care to the individual; and the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual.

Public law: Law regulating relations of individuals with the government or institutions.

Slander: Spoken defamation.

Statutory law: Written laws enacted by the federal or state legislature. For example, the Nurse Practice Act in each state is an example of statutory law that is enacted by the state government.

Student liability: When the student nurse is held responsible for their own actions that cause harm to patients or violate protocols.

Supervisory liability: When a clinical supervisor or preceptor is held responsible for the actions of the student nurse or for failing to properly supervise them.

Tort: An act of commission or omission that causes injury or harm to another person for which the courts impose liability. In the context of torts, "injury" describes the invasion of any legal right, whereas "harm" describes a loss or detriment the individual suffers. Torts are classified as intentional or unintentional.

Unintentional tort: Acts of omission (not doing something a person has a responsibility to do) or inadvertently doing something causing unintended accidents leading to injury, property damage, or financial loss. Examples of unintentional torts impacting nurses include negligence and malpractice.

Learning Objectives

- Compare theories of ethical decision making

- Examine resources to resolve ethical dilemmas

- Examine competent practice within the ethical framework of health care

- Apply the ANA Code of Ethics to diverse situations in health care

- Analyze the impact of cultural diversity in ethical decision making

- Explain advocacy as part of the nursing role when responding to ethical dilemmas

The nursing profession is guided by a code of ethics. As you practice nursing, how will you determine “right” from “wrong” actions? What is the difference between morality, values, and ethical principles? What additional considerations impact your ethical decision-making? What are ethical dilemmas and how should nurses participate in resolving them? This chapter answers these questions by reviewing concepts related to ethical nursing practice and describing how nurses can resolve ethical dilemmas. By the end of this chapter, you will be able to describe how to make ethical decisions using the Code of Ethics established by the American Nurses Association.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines morality as “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals or groups within communities and societies,” whereas ethics is the formal study of morality from a wide range of perspectives.[46] Ethical behavior is considered to be such an important aspect of nursing the ANA has designated Ethics as the first Standard of Professional Performance. The ANA Standards of Professional Performance are "authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently." See the following box for the competencies associated with the ANA Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[47]:

Competencies of ANA's Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[48]

- Uses the Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements as a moral foundation to guide nursing practice and decision-making.

- Demonstrates that every person is worthy of nursing care through the provision of respectful, person-centered, compassionate care, regardless of personal history or characteristics (Beneficence).

- Advocates for health care consumer perspectives, preferences, and rights to informed decision-making and self-determination (Respect for autonomy).

- Demonstrates a primary commitment to the recipients of nursing and health care services in all settings and situations (Fidelity).

- Maintains therapeutic relationships and professional boundaries.

- Safeguards sensitive information within ethical, legal, and regulatory parameters (Nonmaleficence).

- Identifies ethics resources within the practice setting to assist and collaborate in addressing ethical issues.

- Integrates principles of social justice in all aspects of nursing practice (Justice).

- Refines ethical competence through continued professional education and personal self-development activities.

- Depicts one's professional nursing identity through demonstrated values and ethics, knowledge, leadership, and professional comportment.

- Engages in self-care and self-reflection practices to support and preserve personal health, well-being, and integrity.

- Contributes to the establishment and maintenance of an ethical environment that is conducive to safe, quality health care.

- Collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, enhance cultural sensitivity and congruence, and reduce health disparities.

- Represents the nursing perspective in clinic, institutional, community, or professional association ethics discussions.

Reflective Questions

- What Ethics competencies have you already demonstrated during your nursing education?

- What Ethics competencies are you most interested in mastering?

- What questions do you have about the ANA’s Ethics competencies?

The ANA's Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements is an ethical standard that guides nursing practice and ethical decision-making.[49] This section will review several basic ethical concepts related to the ANA's Ethics Standard of Professional Performance, such as values, morals, ethical theories, ethical principles, and the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses.

Values

Values are individual beliefs that motivate people to act one way or another and serve as guides for behavior considered “right” and “wrong.” People tend to adopt the values with which they were raised and believe those values are “right” because they are the values of their culture. Some personal values are considered sacred and moral imperatives based on an individual’s religious beliefs.[50] See Figure 6.1[51] for an image depicting choosing right from wrong actions.

In addition to personal values, organizations also establish values. The American Nurses Association (ANA) Professional Nursing Model states that nursing is based on values such as caring, compassion, presence, trustworthiness, diversity, acceptance, and accountability. These values emerge from nursing practice beliefs, such as the importance of relationships, service, respect, willingness to bear witness, self-determination, and the pursuit of health.[52] As a result of these traditional values and beliefs by nurses, Americans have ranked nursing as the most ethical and honest profession in Gallup polls since 1999, with the exception of 2001, when firefighters earned the honor after the attacks on September 11.[53]

The National League of Nursing (NLN) has also established four core values for nursing education: caring, integrity, diversity, and excellence[54]:

- Caring: Promoting health, healing, and hope in response to the human condition.

- Integrity: Respecting the dignity and moral wholeness of every person without conditions or limitations.

- Diversity: Affirming the uniqueness of and differences among persons, ideas, values, and ethnicities.

- Excellence: Cocreating and implementing transformative strategies with daring ingenuity.

Morals

Morals are the prevailing standards of behavior of a society that enable people to live cooperatively in groups. “Moral” refers to what societies sanction as right and acceptable. Most people tend to act morally and follow societal guidelines, and most laws are based on the morals of a society. Morality often requires that people sacrifice their own short-term interests for the benefit of society. People or entities that are indifferent to right and wrong are considered “amoral,” while those who do evil acts are considered “immoral.”[56]

Ethical Theories

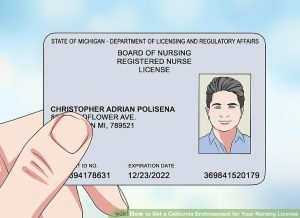

There are two major types of ethical theories that guide values and moral behavior referred to as deontology and consequentialism.

Deontology is an ethical theory based on rules that distinguish right from wrong. See Figure 6.2[57] for a word cloud illustration of deontology. Deontology is based on the word deon that refers to “duty.” It is associated with philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant believed that ethical actions follow universal moral laws, such as, “Don’t lie. Don’t steal. Don’t cheat.”[58] Deontology is simple to apply because it just requires people to follow the rules and do their duty. It doesn’t require weighing the costs and benefits of a situation, thus avoiding subjectivity and uncertainty.[59],[60],[61]

The nurse-patient relationship is deontological in nature because it is based on the ethical principles of beneficence and maleficence that drive clinicians to “do good” and “avoid harm.”[62] Ethical principles will be discussed further in this chapter.

Consequentialism is an ethical theory used to determine whether or not an action is right by the consequences of the action. See Figure 6.3[64] for an illustration of weighing the consequences of an action in consequentialism. For example, most people agree that lying is wrong, but if telling a lie would help save a person’s life, consequentialism says it’s the right thing to do. One type of consequentialism is utilitarianism. Utilitarianism determines whether or not actions are right based on their consequences with the standard being achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people.[65],[66],[67] For this reason, utilitarianism tends to be society-centered. When applying utilitarian ethics to health care resources, money, time, and clinician energy are considered finite resources that should be appropriately allocated to achieve the best health care for society.[68]

Utilitarianism can be complicated when accounting for values such as justice and individual rights. For example, assume a hospital has four patients whose lives depend upon receiving four organ transplant surgeries for a heart, lung, kidney, and liver. If a healthy person without health insurance or family support experiences a life-threatening accident and is considered brain dead but is kept alive on life-sustaining equipment in the ICU, the utilitarian framework might suggest the organs be harvested to save four lives at the expense of one life.[69] This action could arguably produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people, but the deontological approach could argue this action would be unethical because it does not follow the rule of “do no harm.”

Read more about Decision making on organ donation: The dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors.

Interestingly, deontological and utilitarian approaches to ethical issues may result in the same outcome, but the rationale for the outcome or decision is different because it is focused on duty (deontologic) versus consequences (utilitarian).