11.14 Hernia

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

A hernia is when internal organs or tissues bulge through an inappropriate opening. Common types of hernias are inguinal hernias, hiatal hernias, and ventral hernias[1],[2],[3],[4],[5]:

- Inguinal hernias occur in the inguinal canal. The inguinal canal is a passageway that contains the spermatic cord and blood vessels in men and the round ligaments in women. See Figure 11.36[6] for an image of the small bowel herniating through the inguinal canal of a male.

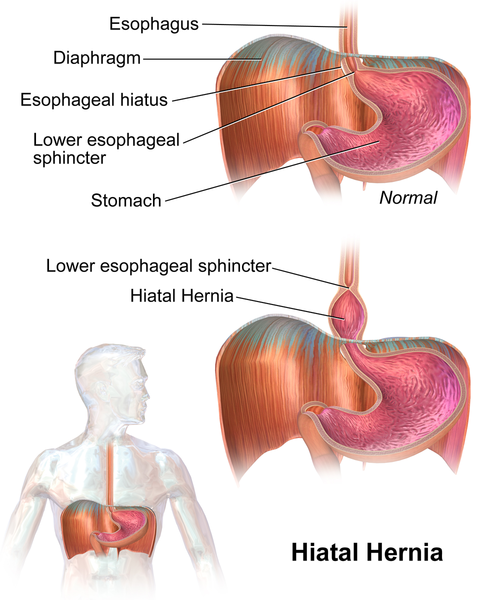

- Hiatal hernias are when part of the stomach bulges through the diaphragmatic opening. This opening of the diaphragm is also known as the esophageal hiatus as the esophagus passes through this opening on its way to the stomach. See Figure 11.37[7] for an illustration of a hiatal hernia.

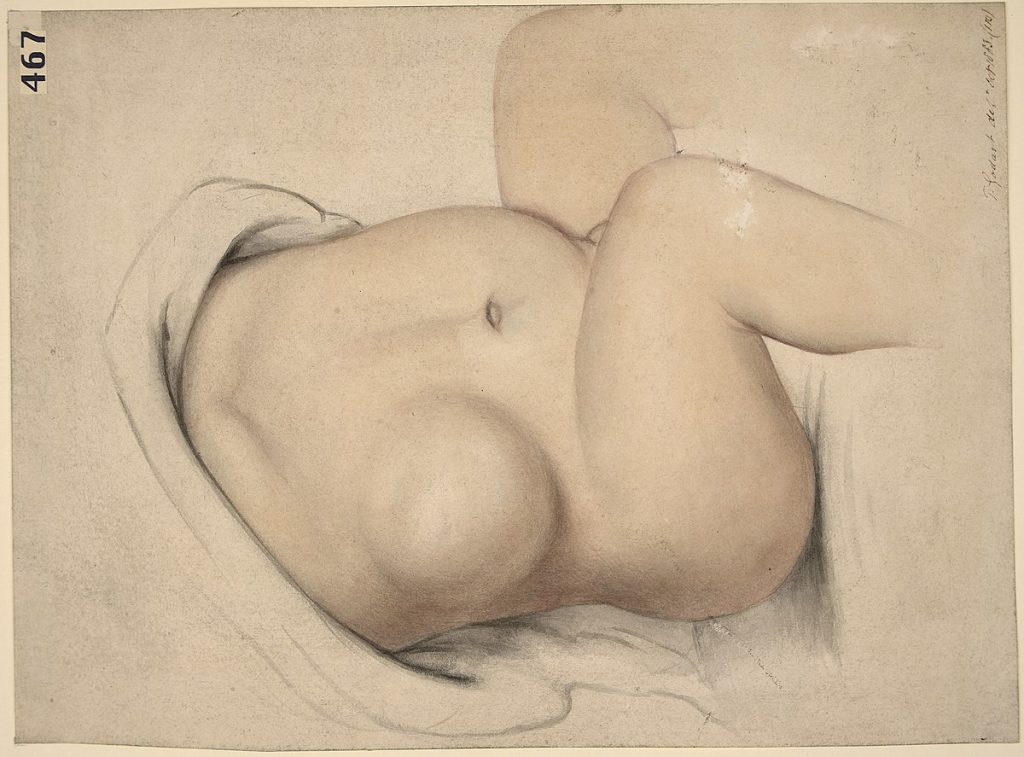

- Ventral hernias are hernias that occur in the wall of the abdomen and are neither inguinal nor hiatal in origin. See Figure 11.38[8] for an illustration of a ventral hernia in a child.

All types of hernias can be present at birth (i.e., congenital) or acquired over time, but they are most likely to be acquired. Risk factors for hernias depend on the specific type of hernia. See Table 11. 14 for a comparison of risk factors for inguinal, hiatal, and ventral hernias.[9],[10],[11],[12],[13]

Table 11.14. Hernia Risk Factors

| Inguinal Hernia | Ventral Hernia | Hiatal Hernia |

|---|---|---|

| Family history | Previous surgical procedures (leads to an incisional hernia or a hernia at the site of an incision) | Previous surgery |

| History of connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan syndrome | Trauma to abdominal wall | Trauma to abdominal wall |

| Increased intra-abdominal pressure (obesity, coughing, lifting of heavy objects, staining with bowel movements) | Stress to abdominal wall (obesity or frequent weight loss and gain) | Increased intra-abdominal pressure (obesity, pregnancy, straining with bowel movements, COPD) |

| Not linked to age, but much more common in males | Not linked to age | Older age |

| No genetic link | No genetic link | Genetic link |

Hernias can be further described as reducible or incarcerated. A reducible hernia means that the hernia and its contents can be pushed back into their normal anatomical space. An incarcerated hernia means that the hernia cannot be reduced. This can lead to a strangulated hernia, or when the hernia undergoes a reduction in oxygen supply due to reduced blood flow. This is considered a medical emergency that requires urgent surgical intervention.[14],[15],[16],[17],[18]

View a supplementary YouTube video[19] on hernias and hernia repair: Repairing a hernia with surgery.

Pathophysiology

Hernias usually occur when there is a combination of increased pressure, as well as an area of weakened tissue or musculature. The increase in pressure causes the organ or tissue to push through the weakened area.[20],[21],[22],[23],[24]

An inguinal hernia occurs when there is a weakened area in the oblique or transversalis muscles and abdominal organs protrude through the opening. These clients are also more likely to have increased levels of Type III collagen as opposed to Type I collagen, which is stronger. There is also a link between a patent processus vaginalis and the formation of an inguinal hernia. The processus vaginalis forms in fetal development. In males, it aids in the descent of the testicles through the inguinal canal. In females, it plays a role in the development of the round ligament. When this process does not occur in a normal fashion and the processus vaginalis does not close appropriately, the client is at greater risk for an inguinal hernia.[25],[26],[27],[28],[29]

In clients with a ventral hernia, recurrent stress to the abdominal wall leads to the development of small tears in the abdominal tissue. With time, the abdominal tissue has reduced strength and increased intra-abdominal pressure, which can lead to abdominal organs protruding through the weakened area.[30]

With a hiatal hernia, the stomach is pushed through the esophageal hiatus into the chest by one of the causative factors mentioned above. This compromises the integrity of the lower esophageal sphincter and is a leading cause of gastroesophageal reflux disease.[31]

Assessment

Physical Exam

Presenting signs and symptoms of a hernia will depend on the specific type and location of the hernia. Common signs and symptoms of inguinal and ventral hernias are as follows[32],[33]:

- Visible bulge in the area of the hernia

- Pain in the location of the hernia

- Increase in pain or size of bulge with activity, changes in position, or increases in intra-abdominal pressure

In addition to assessing for the aforementioned signs and symptoms, a physical exam can also aid in the diagnosis of inguinal and ventral hernias. With an inguinal hernia, the client is asked to stand so the health care provider can visualize the inguinal area for the presence of a bulge. The client will then be instructed to cough or bear down while the provider palpates the inguinal area. If there is a bulge that moves in and out with the increase in intra-abdominal pressure, an inguinal hernia is likely present. A ventral hernia can usually also be seen upon visualization of the abdomen. However, this should be done with the client in various positions as the appearance of the hernia can change based on the position of the client. Additionally, if the client is obese, a physical exam may have limited success in the diagnosis of a ventral hernia.[34],[35],[36],[37]

Common signs and symptoms of hiatal hernias are as follows[38]:

- Heartburn or other GERD symptoms

- Chronic coughing or asthma

- Regurgitation of stomach contents

- Difficulty or painful swallowing

If a hernia of any type becomes strangulated, the client may exhibit the following signs and symptoms[39]:

- Signs of a bowel obstruction such as nausea, vomiting, and absence of feces and flatus

- Severe pain

- Signs of sepsis (decreased blood pressure and elevated heart rate)

- Reddened or dusky skin over the hernia site (inguinal and ventral hernias only)

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Although the presence of an inguinal or ventral hernia can often be detected via physical exam, imaging is often used to help confirm a diagnosis. Common imaging modalities used are ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI. An ultrasound is the least invasive modality, but not as sensitive and specific as an MRI. However, MRIs are expensive to perform, so a CT scan may be a better option in cases of unclear ultrasound results.[40],[41]

In those with a suspected hiatal hernia, there are a number of potential diagnostic tests. A barium swallow can show the presence of a hiatal hernia, as well as its size and specific location. A barium swallow can also show areas of narrowing that may have occurred due to chronic GERD. An EGD may be performed to diagnose a hiatal hernia. Esophageal manometry, a test that measures esophageal motility, can also be used to diagnose hiatal hernia, as well as rule out other conditions with similar symptoms. Lastly, although a CT scan is not a first-line tool to diagnose a hiatal hernia, it may be used if additional information is needed regarding the location and type of hiatal hernia.[42]

Lab tests are not used in the diagnosis of hernias, but they will be used when strangulation of a hernia is suspected. In the case of strangulation, a complete blood count may show elevated white blood cells, and lactic acid levels may be elevated if the client is septic.[43]

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing priorities for those suffering from a hernia include managing symptoms, preventing complications, and client education.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with a hernia are created based on the specific needs of the client, their signs and symptoms, and the etiology of the disorder. These nursing diagnoses guide the creation of client specific care plans that encompass client outcomes and nursing interventions, as well the evaluation of those outcomes. These individualized care plans then serve as a guide for client treatment.

Common nursing diagnoses for those with a hernia are as follows[44],[45]:

- Acute Pain

- Risk for Injury

- Risk for Infection

- Readiness for Enhanced Knowledge

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification encompasses the creation of short- and long-term goals for the client. These goals are used to create expected outcome statements that are based on the specific needs of the client. Expected outcomes should be specific, measurable, and realistic. These outcomes should be achievable within a set time frame based on the application of appropriate nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes include the following:

- The client will rate their pain at 3 or less on a scale of 0 to 10.

- The client will remain free from signs and symptoms of a strangulated hernia (nausea, vomiting, absence of feces and flatus).

- The client will verbalize three methods to reduce their risk of contracting a surgical site infection after the teaching session.

- The client will describe common causes and treatment of hernias after the teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Specific medical interventions depend on the type and severity of the hernia present. The medical treatment approach for each hernia type covered in this textbook will be described below.

Hiatal Hernias

In those with hiatal hernias, symptoms of GERD may be managed with proton pump inhibitors and lifestyle modifications such as losing weight, elevating the head of the bed, and avoiding eating before bed. If PPIs are able to manage symptoms in those with a hiatal hernia, surgical management may not be needed.[46]

Surgical management should be considered when the client’s symptoms are not managed with PPIs, when severe damage to the esophagus has occurred due to GERD, or when the hernia is large in size. Although there are a variety of options for surgical repair, a common procedure is the Nissen fundoplication. See the “Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease” section for more information on this procedure. Surgical management may be required for complications such as a gastric volvulus. A gastric volvulus is a type of obstruction in which the stomach twists upon itself.[47],[48]

Inguinal Hernias

If the inguinal hernia is asymptomatic, the provider typically recommends watchful waiting. Watchful waiting consists of monitoring the hernia for worsening symptoms. Surgical management is advised for symptomatic cases. Open and laparoscopic surgical methods have similar percentages for hernia recurrence. Although some approaches only repair the damaged tissue that allowed the hernia to occur, other approaches place a surgical mesh at the hernia site to support healing and prevent hernia recurrence.[49]

Ventral Hernias

As with inguinal hernias, those with asymptomatic ventral hernias may also undergo watchful waiting. Ventral hernias that present with incarceration but without strangulation should have the hernia repaired surgically, but it is not emergent. Clients who have a strangulated ventral hernia require emergency surgery. Ventral hernias can be repaired in an open or laparoscopic manner or even with the assistance of robotic technology. Those who undergo laparoscopic repair tend to have fewer complications and a shorter hospital stay than those who undergo an open procedure. As with inguinal hernia repair, there are a variety of surgical techniques that can be used, and the approach varies from repairing the damaged tissue to implanting a surgical mesh.[50]

Nursing Interventions

When providing nursing care for a client with a hernia, nursing interventions can be divided into nursing assessments, nursing actions, and client teaching.[51],[52]

Nursing Assessments

- Assess for increased tenderness, decreased appetite, and altered bowel movements, as this could indicate intestinal blockage due to incarceration or strangulation.

- Assess the client’s pain on a scale of 0-10. Pain is common after surgical repair of hernias and should be treated adequately. Changes in pain preoperatively could also indicate a complication such as a strangulated hernia.

- Assess the client’s surgical site after hernia repair for edema, erythema, and bleeding.

Nursing Actions

- Administer pain medications per provider order to manage the client’s pain.

- Administer stool softeners to prevent straining during bowel movements per provider order.

- Apply ice to the surgical site to reduce swelling and help reduce pain.

- Offer a scrotal support for male clients undergoing surgical repair of an inguinal hernia, as this can reduce swelling and optimize comfort levels.

Client Teaching

- Reinforce education given by the provider on the methods of surgical repair of hernias and ensure the client’s questions are answered.

- Encourage hernia prevention/recurrence by teaching the importance of maintaining a healthy weight, preventing constipation by eating high-fiber foods, avoiding lifting heavy loads, following postoperative activity restrictions, and seeking treatment for persistent coughing.

- Educate the client about the need to increase fluids and protein in the diet to promote healing and good nutrition.

- Educate the client on any wound care needs they will have after discharge, as well as how to monitor the surgical site for signs of infection.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with another member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Hernia

RN Recap: Hernia

View a brief YouTube video overview of hernia[53]:

- Curran, A. (2022, May 18). Hernia nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/hernia-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Strangulated Hernia by Pastorino & Alshuqayfi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “Inguinalhernia.gif” by National Institutes of Health is in the Public Domain ↵

- “Hiatal_Hernia.png” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Ventral_hernia_Wellcome_L0061630.jpg” by unknown author for Welcomimages.org is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Curran, A. (2022, May 18). Hernia nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/hernia-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Strangulated Hernia by Pastorino & Alshuqayfi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Curran, A. (2022, May 18). Hernia nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/hernia-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Strangulated Hernia by Pastorino & Alshuqayfi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2015, March 10). Repairing a hernia with surgery [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLw3AjZx3NQ ↵

- Curran, A. (2022, May 18). Hernia nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/hernia-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Brainwood, M., Beirne, G., & Fenech, M. (2020). Persistence of the processus vaginalis and its related disorders. Australasian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine. 23(1), 22-29. https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fajum.12195 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Curran, A. (2022, May 18). Hernia nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/hernia-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Brainwood, M., Beirne, G., & Fenech, M. (2020). Persistence of the processus vaginalis and its related disorders. Australasian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine. 23(1), 22-29. https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fajum.12195 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Strangulated Hernia by Pastorino & Alshuqayfi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Strangulated Hernia by Pastorino & Alshuqayfi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- The management of hiatal hernia: an update on diagnosis and treatment by Sfara & Dumitrascu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Strangulated Hernia by Pastorino & Alshuqayfi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Hiatal Hernia by Smith & Shahjehan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- The management of hiatal hernia: an update on diagnosis and treatment by Sfara & Dumitrascu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Ventral Hernia by Smith & Parmely is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Curran, A. (2022, May 18). Hernia nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan. https://nursestudy.net/hernia-nursing-diagnosis/?expand_article=1 ↵

- Inguinal Hernia by Hammoud & Gerken is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 11 - Hernia [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/n8tV3p0vg8Y?si=0OgLM1pdF93gVTp5 ↵

Now that we have reviewed the anatomy of the integumentary system, let’s review common conditions that you may find during a routine integumentary assessment.

Acne

Acne is a skin disturbance that typically occurs on areas of the skin that are rich in sebaceous glands, such as the face and back. It is most common during puberty due to associated hormonal changes that stimulate the release of sebum. An overproduction and accumulation of sebum, along with keratin, can block hair follicles. Acne results from infection by acne-causing bacteria and can lead to potential scarring.[1] See Figure 14.8[2] for an image of acne.

Lice and Nits

Head lice are tiny insects that live on a person’s head. Adult lice are about the size of a sesame seed, but the eggs, called nits, are smaller and can appear like a dandruff flake. See Figure 14.9[3] for an image of very small white nits in a person’s hair. Children ages 3-11 often get head lice at school and day care because they have head-to-head contact while playing together. Lice move by crawling and spread by close person-to-person contact. Rarely, they can spread by sharing personal belongings such as hats or hair brushes. Contrary to popular belief, personal hygiene and cleanliness have nothing to do with getting head lice. Symptoms of head lice include the following:

- Tickling feeling in the hair

- Frequent itching, which is caused by an allergic reaction to the bites

- Sores from scratching, which can become infected with bacteria

- Trouble sleeping due to head lice being most active in the dark

A diagnosis of head lice usually comes from observing a louse or nit on a person’s head. Because they are very small and move quickly, a magnifying lens and a fine-toothed comb may be needed to find lice or nits. Treatments for head lice include over-the-counter and prescription shampoos, creams, and lotions such as permethrin lotion.[4]

Burns

A burn results when the skin is damaged by intense heat, radiation, electricity, or chemicals. The damage results in the death of skin cells, which can lead to a massive loss of fluid due to loss of the skin’s protection. Burned skin is also extremely susceptible to infection due to the loss of protection by intact layers of skin.

Burns are classified by the degree of their severity. A first-degree burn, also referred to as a superficial burn, only affects the epidermis. Although the skin may be painful and swollen, these burns typically heal on their own within a few days. Mild sunburn fits into the category of a first-degree burn. A second-degree burn, also referred to as a partial thickness burn, affects both the epidermis and a portion of the dermis. These burns result in swelling and a painful blistering of the skin. It is important to keep the burn site clean to prevent infection. With good care, a second-degree burn will heal within several weeks. A third-degree burn, also referred to as a full-thickness burn, extends fully into the epidermis and dermis, destroying the tissue and affecting the nerve endings and sensory function. These are serious burns that require immediate medical attention. A fourth-degree burn, also referred to as a deep full-thickness burn, is even more severe, affecting the underlying muscle and bone. Third- and fourth-degree burns are usually not as painful as second-degree burns because the nerve endings are damaged. Full-thickness burns require debridement (removal of dead skin) followed by grafting of the skin from an unaffected part of the body or from skin grown in tissue culture.[5] See Figure 14.10[6] for an image of a patient recovering from a second-degree burn on the hand.

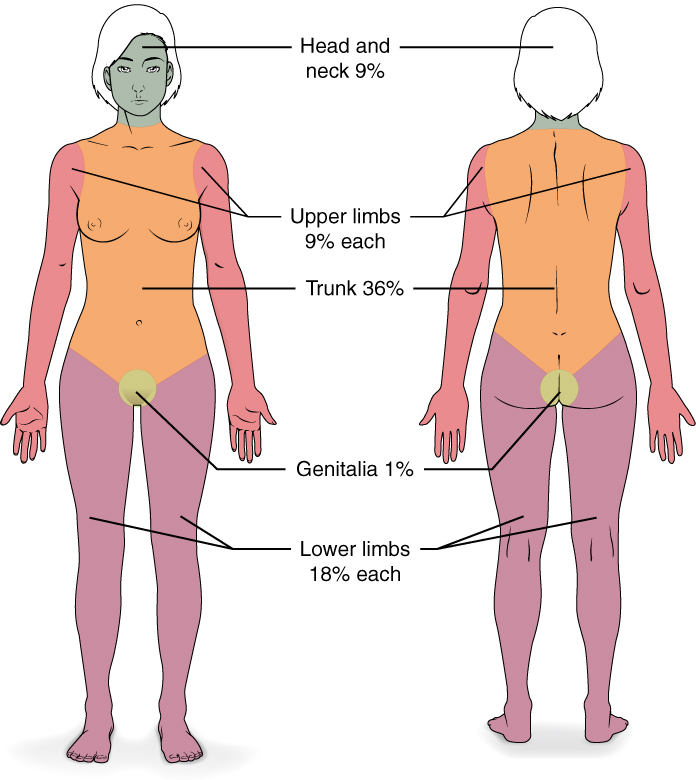

Severe burns are quickly measured in emergency departments using a tool called the “Rule of Nines,” which associates specific anatomical locations with a percentage that is a factor of nine. Rapid estimate of the burned surface area is used to estimate intravenous fluid replacement because patients will have massive fluid losses due to the removal of the skin barrier.[7] See Figure 14.11[8] for an illustration of the rule of nines. The head is 9% (4.5% on each side), the upper limbs are 9% each (4.5% on each side), the lower limbs are 18% each (9% on each side), and the trunk is 36% (18% on each side).

Scars

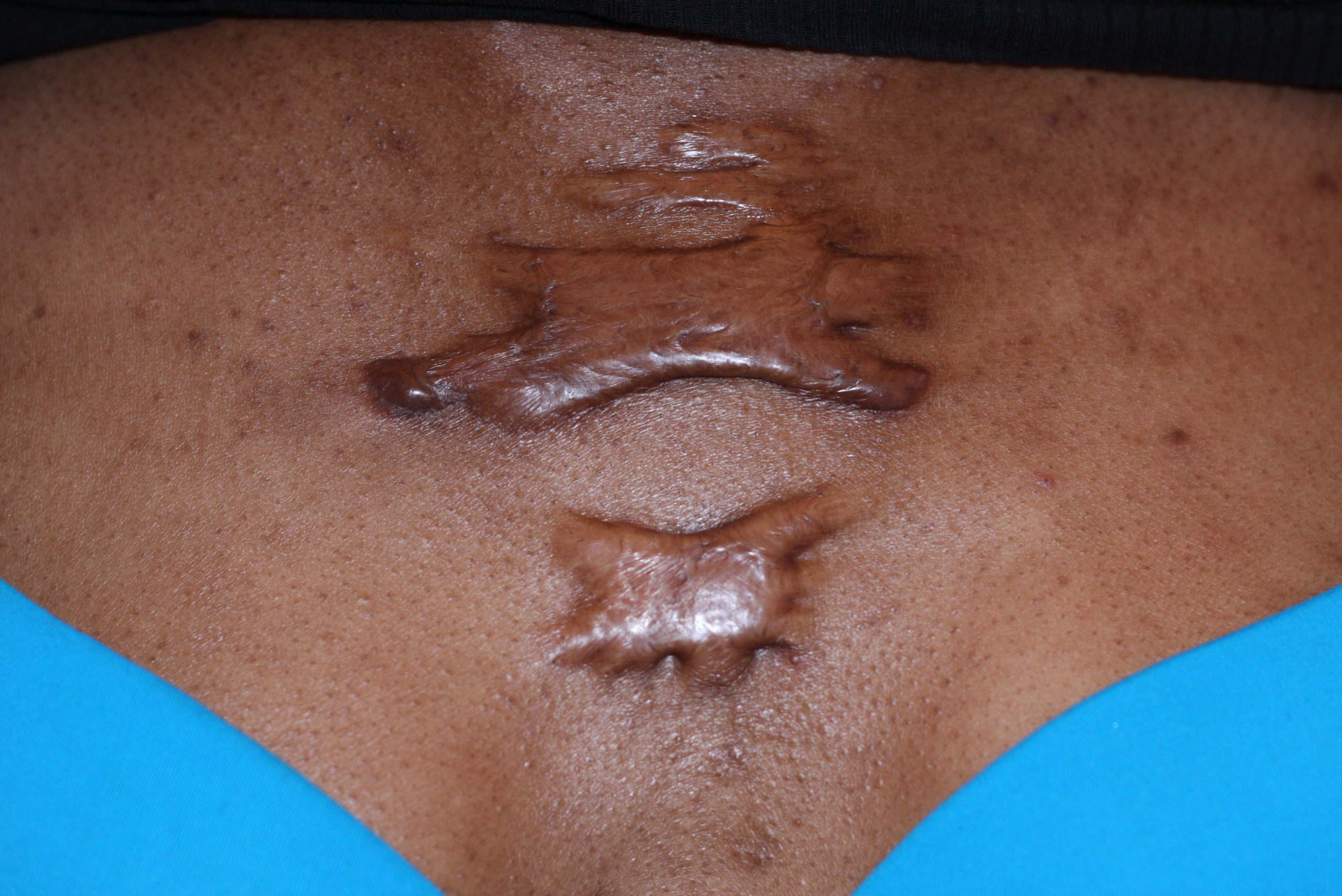

Most cuts and wounds cause scar formation. A scar is collagen-rich skin formed after the process of wound healing. Sometimes there is an overproduction of scar tissue because the process of collagen formation does not stop when the wound is healed, resulting in the formation of a raised scar called a keloid.[9] Keloids are more common in patients with darker skin color. See Figure 14.12[10] for an image of a keloid that has developed from a scar on a patient’s chest wall.

Skin Cancer

Skin cancer is common, with one in five Americans experiencing some type of skin cancer in their lifetime. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common of all cancers that occur in the United States and is frequently found on areas most susceptible to long-term sun exposure such as the head, neck, arms, and back. Basal cell carcinomas start in the epidermis and become an uneven patch, bump, growth, or scar on the skin surface. Treatment options include surgery, freezing (cryosurgery), and topical ointments.[11]

Squamous cell carcinoma presents as lesions commonly found on the scalp, ears, and hands. If not removed, squamous cell carcinomas can metastasize to other parts of the body. Surgery and radiation are used to cure squamous cell carcinoma. See Figure 14.13[12] for an image of squamous cell carcinoma.[13]

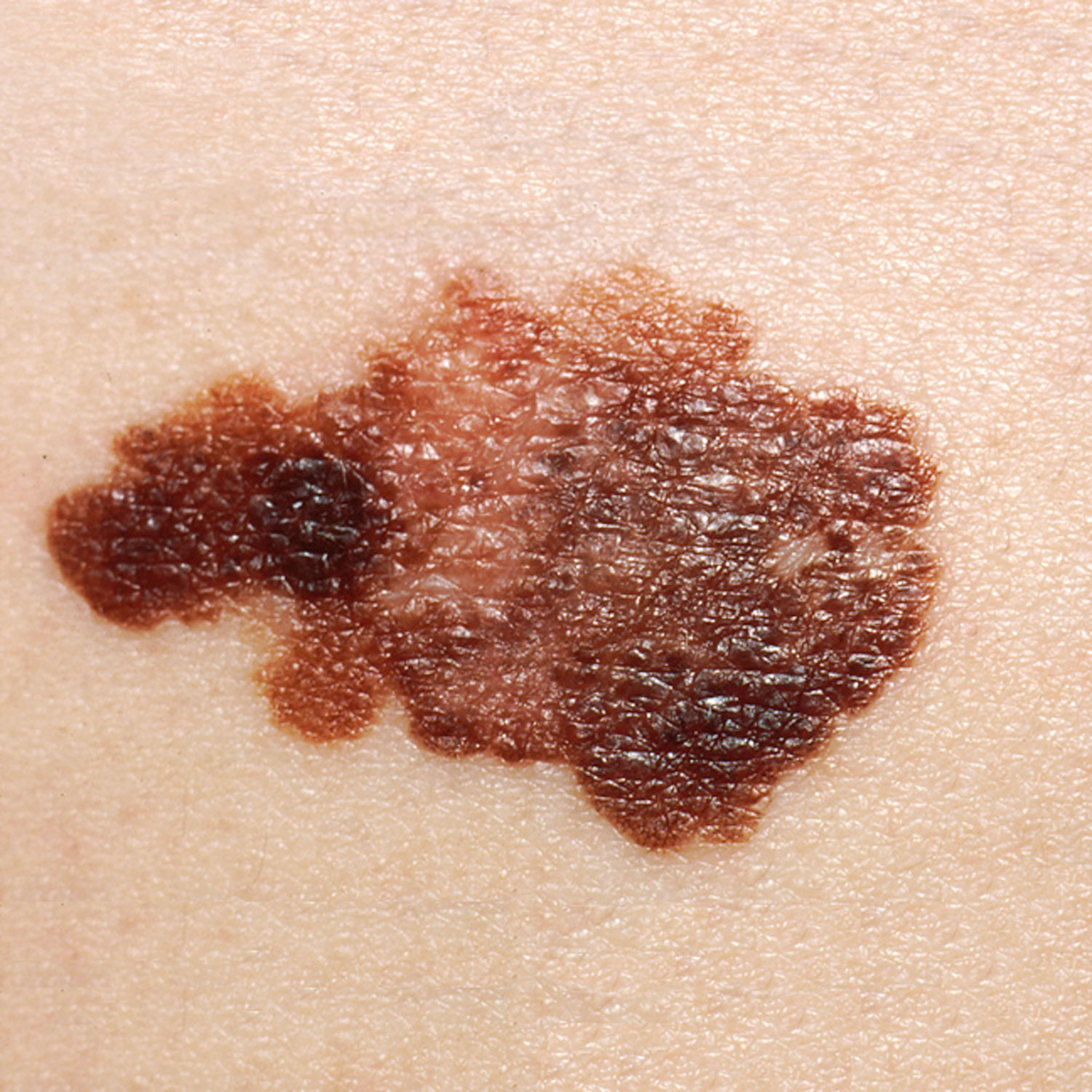

Melanoma is a cancer characterized by the uncontrolled growth of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the epidermis. A melanoma commonly develops from an existing mole. See Figure 14.14[14] for an image of a melanoma. Melanoma is the most fatal of all skin cancers because it is highly metastatic and can be difficult to detect before it has spread to other organs. Melanomas usually appear as asymmetrical brown and black patches with uneven borders and a raised surface. Treatment includes surgical excision and immunotherapy.[15]

Fungal (Tinea) Infections

Tinea is the name of a group of skin diseases caused by a fungus. Types of tinea include ringworm, athlete's foot, and jock itch. These infections are usually not serious, but they can be uncomfortable because of the symptoms of itching and burning. They can be transmitted by touching infected people, damp surfaces such as shower floors, or even from pets.[16] Ringworm (tinea corporis) is a type of rash that forms on the body that typically looks like a red ring with a clear center, although a worm doesn't cause it. Scalp ringworm (tinea capitals) causes itchy, red patches on the head that can leave bald spots. Athlete's foot (tinea pedis) causes itching, burning, and cracked skin between the toes. Jock itch (tinea cruris) causes an itchy, burning rash in the groin area. Fungal infections are often treated successfully with over-the-counter creams and powders, but some require prescription medicine such as nystatin. See Figure 14.15[17] for an image of a tinea in a patient’s groin.[18]

Impetigo

Impetigo is a common skin infection caused by bacteria in children between the ages two and six. It is commonly caused by Staphylococcus (staph) or Streptococcus (strep) bacteria. See Figure 14.16[19] for an image of impetigo. Impetigo often starts when bacteria enter a break in the skin, such as a cut, scratch, or insect bite. Symptoms start with red or pimple-like sores surrounded by red skin. The sores fill with pus and then break open after a few days and form a thick crust. They are often itchy but scratching them can spread the sores. Impetigo can spread by contact with sores or nasal discharge from an infected person and is treated with antibiotics.

Edema

Edema is caused by fluid accumulation within the tissues often caused by underlying cardiovascular or renal disease. Read more about edema in the “Cardiovascular Basic Concepts” section of the "Cardiovascular Assessment" chapter.

Lymphedema

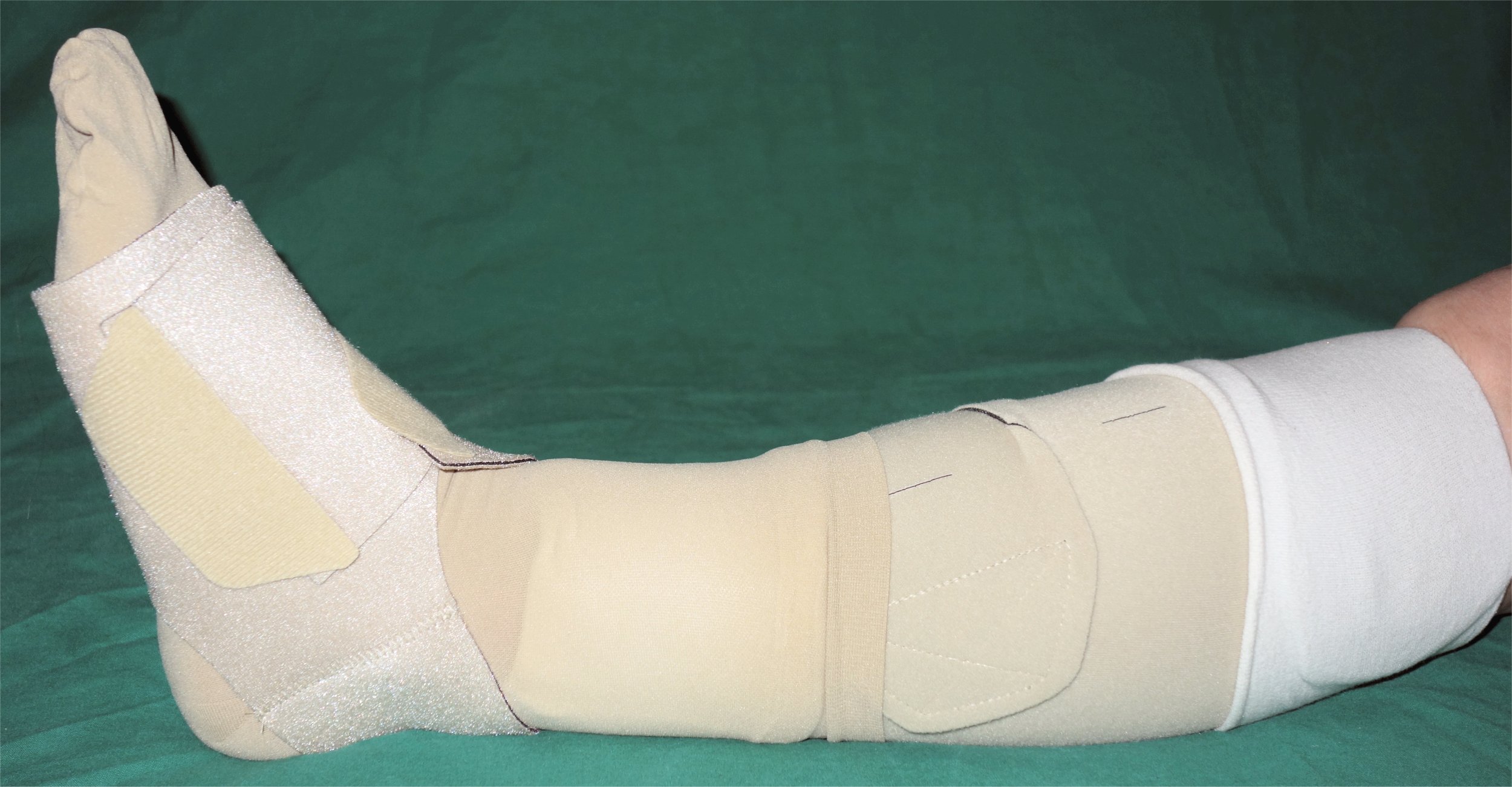

Lymphedema is the medical term for a type of swelling that occurs when lymph fluid builds up in the body's soft tissues due to damage to the lymph system. It often occurs unilaterally in the arms or legs after surgery has been performed that injured the regional lymph nodes. See Figure 14.17[20] for an image of lower extremity edema. Causes of lymphedema include infection, cancer, scar tissue from radiation therapy, surgical removal of lymph nodes, or inherited conditions. There is no cure for lymphedema, but elevation of the affected extremity is vital. Compression devices and massage can help to manage the symptoms. See Figure 14.18[21] for an image of a specialized compression dressing used for lymphedema. It is also important to remember to avoid taking blood pressure on a patient’s extremity with lymphedema.[22]

Jaundice

Jaundice causes skin and sclera (whites of the eyes) to turn yellow. Due to variation in skin color, assessing for the presence jaundice is most accurately noted in the sclera of the eyes and/or the roof of mouth (hard palate). See Figure 14.19[23] for an image of a patient with jaundice visible in the sclera and the skin. Jaundice is caused by too much bilirubin in the body. Bilirubin is a yellow chemical in hemoglobin, the substance that carries oxygen in red blood cells. As red blood cells break down, the old ones are processed by the liver. If the liver can’t keep up due to large amounts of red blood cell breakdown or liver damage, bilirubin builds up and causes the skin and sclera to appear yellow. New onset of jaundice should always be reported to the health care provider.

Many healthy babies experience mild jaundice during the first week of life that usually resolves on its own, but some babies require additional treatment such as light therapy. Jaundice can happen at any age for many reasons, such as liver disease, blood disease, infections, or side effects of some medications.[24]

Pressure Injuries

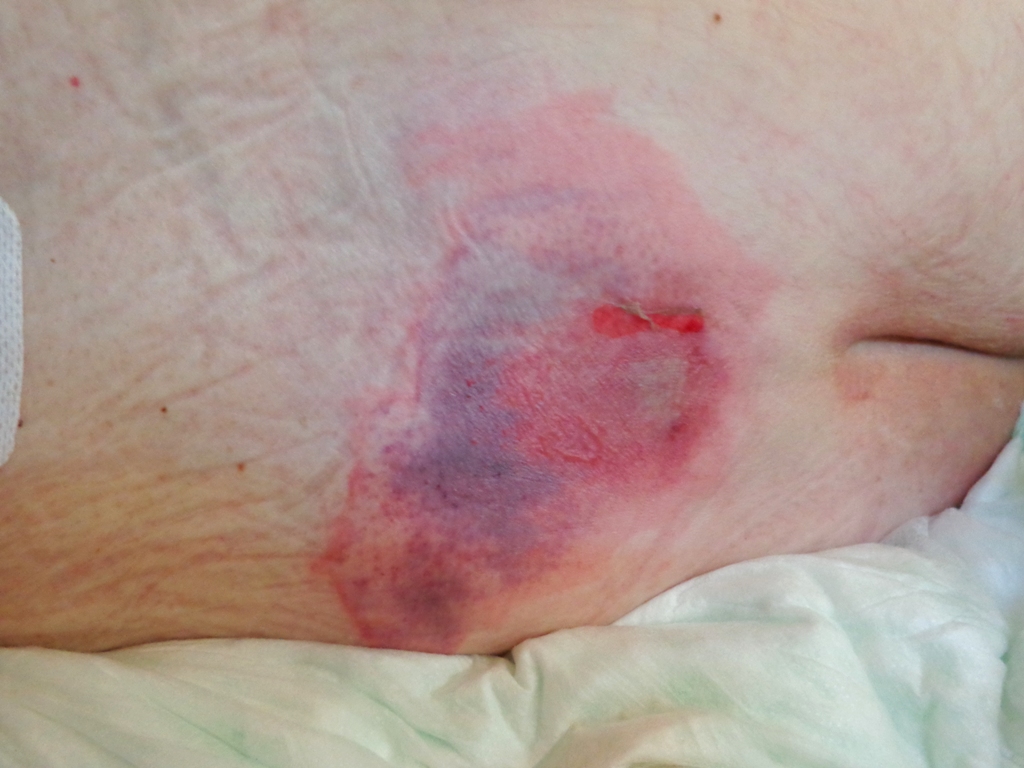

Pressure injuries , also called bedsores, form when a patient’s skin and soft tissue press against a hard surface, such as a chair or bed, for a prolonged period of time. The pressure against a hard surface reduces blood supply to that area, causing the skin tissue to become damaged and become an ulcer. Patients are at high risk of developing a pressure injury if they spend a lot of time in one position, have decreased sensation, or have bladder or bowel leakage.[25] See Figure 14.20[26] for an image of a pressure ulcer injury on a bed-bound patient’s back. Read more information about assessing and caring for a pressure injury in the “Wound Care" chapter.

Petechiae

Petechiae are tiny red dots caused by bleeding under the skin that may appear like a rash. Large petechiae are called purpura. An easy method used to assess for petechiae is to apply pressure to the rash with a gloved finger. A rash will blanch (i.e., whiten with pressure) but petechiae and purpura do not blanch. See Figure 14.21[27] for an image of petechiae and purpura. New onset of petechiae should be immediately reported to the health care provider because it can indicate a serious underlying medical condition.[28]

Now that we have reviewed the anatomy of the integumentary system and common integumentary conditions, let’s review the components of an integumentary assessment. The standard for documentation of skin assessment is within 24 hours of admission to inpatient care. Skin assessment should also be ongoing in inpatient and long-term care.[29]

A routine integumentary assessment by a registered nurse in an inpatient care setting typically includes inspecting overall skin color, inspecting for skin lesions and wounds, and palpating extremities for edema, temperature, and capillary refill.[30]

Subjective Assessment

Begin the assessment by asking focused interview questions regarding the integumentary system. Itching is the most frequent complaint related to the integumentary system. See Table 14.4a for sample interview questions.

Table 14.4a Focused Interview Questions for the Integumentary System

| Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Are you currently experiencing any skin symptoms such as itching, rashes, or an unusual mole, lump, bump, or nodule?[31] | Use the PQRSTU method to gain additional information about current symptoms. Read more about the PQRSTU method in the "Health History" chapter. |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a condition such as acne, eczema, skin cancer, pressure injuries, jaundice, edema, or lymphedema? | Please describe. |

| Are you currently using any prescription or over-the-counter medications, creams, vitamins, or supplements to treat a skin, hair, or nail condition? | Please describe. |

Objective Assessment

There are five key areas to note during a focused integumentary assessment: color, skin temperature, moisture level, skin turgor, and any lesions or skin breakdown. Certain body areas require particular observation because they are more prone to pressure injuries, such as bony prominences, skin folds, perineum, between digits of the hands and feet, and under any medical device that can be removed during routine daily care.[32]

Inspection

Color

Inspect the color of the patient’s skin and compare findings to what is expected for their skin tone. Note a change in color such as pallor (paleness), cyanosis (blueness), jaundice (yellowness), or erythema (redness). Note if there is any bruising (ecchymosis) present.

Scalp

If the patient reports itching of the scalp, inspect the scalp for lice and/or nits.

Lesions and Skin Breakdown

Note any lesions, skin breakdown, or unusual findings, such as rashes, petechiae, unusual moles, or burns. Be aware that unusual patterns of bruising or burns can be signs of abuse that warrant further investigation and reporting according to agency policy and state regulations.

Auscultation

Auscultation does not occur during a focused integumentary exam.

Palpation

Palpation of the skin includes assessing temperature, moisture, texture, skin turgor, capillary refill, and edema. If erythema or rashes are present, it is helpful to apply pressure with a gloved finger to further assess for blanching (whitening with pressure).

Temperature, Moisture, and Texture

Fever, decreased perfusion of the extremities, and local inflammation in tissues can cause changes in skin temperature. For example, a fever can cause a patient’s skin to feel warm and sweaty (diaphoretic). Decreased perfusion of the extremities can cause the patient’s hands and feet to feel cool, whereas local tissue infection or inflammation can make the localized area feel warmer than the surrounding skin. Research has shown that experienced practitioners can palpate skin temperature accurately and detect differences as small as 1 to 2 degrees Celsius. For accurate palpation of skin temperature, do not hold anything warm or cold in your hands for several minutes prior to palpation. Use the palmar surface of your dominant hand to assess temperature.[33] While assessing skin temperature, also assess if the skin feels dry or moist and the texture of the skin. Skin that appears or feels sweaty is referred to as being diaphoretic.

Capillary Refill

The capillary refill test is a test done on the nail beds to monitor perfusion, the amount of blood flow to tissue. Pressure is applied to a fingernail or toenail until it turns white, indicating that the blood has been forced from the tissue under the nail. This whiteness is called blanching. Once the tissue has blanched, remove pressure. Capillary refill is defined as the time it takes for color to return to the tissue after pressure has been removed that caused blanching. If there is sufficient blood flow to the area, a pink color should return within 2 seconds after the pressure is removed.[34]

View the Cardiovascular Assessment Part Two | Capillary Refill Test YouTube video for a demonstration of capillary refill.[35]

Skin Turgor

Skin turgor may be included when assessing a patient’s hydration status, but research has shown it is not a good indicator. Skin turgor is the skin's elasticity. Its ability to change shape and return to normal may be decreased when the patient is dehydrated. To check for skin turgor, gently grasp skin on the patient’s lower arm between two fingers so that it is tented upwards, and then release. Skin with normal turgor snaps rapidly back to its normal position, but skin with poor turgor takes additional time to return to its normal position.[36] Skin turgor is not a reliable method to assess for dehydration in older adults because they have decreased skin elasticity, so other assessments for dehydration should be included.[37]

Edema

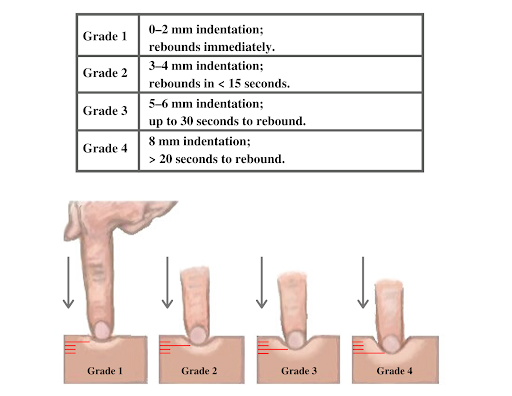

If edema is present on inspection, palpate the area to determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting. Press on the skin to assess for indentation, ideally over a bony structure, such as the tibia. If no indentation occurs, it is referred to as nonpitting edema. If indentation occurs, it is referred to as pitting edema. See Figure 14.22[38] for an image demonstrating pitting edema. If pitting edema is present, document the depth of the indention and how long it takes for the skin to rebound back to its original position. The indentation and time required to rebound to the original position are graded on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1+ indicates a barely detectable depression with immediate rebound, and 4+ indicates a deep depression with a time lapse of over 20 seconds required to rebound. See Figure 14.23[39] for an illustration of grading edema.

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults

Older adults have several changes associated with aging that are apparent during assessment of the integumentary system. They often have cardiac and circulatory system conditions that cause decreased perfusion, resulting in cool hands and feet. They have decreased elasticity and fragile skin that often tears more easily. The blood vessels of the dermis become more fragile, leading to bruising and bleeding under the skin. The subcutaneous fat layer thins, so it has less insulation and padding and reduced ability to maintain body temperature. Growths such as skin tags, rough patches (keratoses), skin cancers, and other lesions are more common. Older adults may also be less able to sense touch, pressure, vibration, heat, and cold.[40]

When completing an integumentary assessment, it is important to distinguish between expected and unexpected assessment findings. Please review Table 14.4b to review common expected and unexpected integumentary findings.

Table 14.4b Expected Versus Unexpected Findings on Integumentary Assessment

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify provider if it is a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Skin is expected color for ethnicity without lesions or rashes. | Jaundice

Erythema Cyanosis Irregular-looking mole Bruising (ecchymosis) Rashes Petechiae Skin breakdown Burns |

| Auscultation | Not applicable | |

| Palpation | Skin is warm and dry with no edema. Capillary refill is less than 3 seconds. Skin has normal turgor with no tenting. | Diaphoretic or clammy

Cool extremity Edema Lymphedema Capillary refill greater than 3 seconds Tenting |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Cool and clammy

Diaphoretic Petechiae Jaundice Cyanosis Redness, warmth, and tenderness indicating a possible infection |