9.11 Myasthenia Gravis

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a chronic, autoimmune neuromuscular disease that causes weakness in voluntary muscles, including those required for breathing and swallowing. Onset of symptoms can be rapid.[1]

Pathophysiology

A key concept to understand related to MG is cholinesterase. Cholinesterase is a family of enzymes that break down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) into choline and acetic acid. This reaction is necessary to allow a cholinergic neuron to return to its resting state after activation.[2]

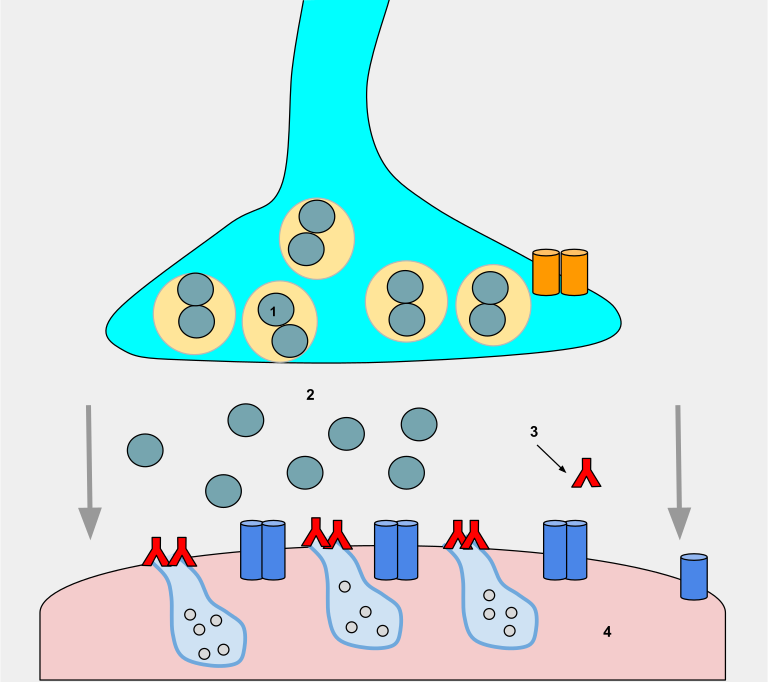

MG affects the neuromuscular junction. Within a normal working nervous system, a chemical impulse causes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Ach) to be released into the neuromuscular junction. Acetylcholine attaches to the receptor sites of a muscle and stimulates a muscle contraction. Acetylcholine continually binds to the receptor sites to sustain muscle contraction.

During MG, an autoimmune response causes antibodies to bind to muscle receptor sites. These antibodies block acetylcholine from binding to the muscle receptor sites, thus impairing the transmission of impulses across the neuromuscular junction and causing muscle weakness that worsens with physical activity. See Figure 9.29[3] for an illustration of antibodies (red Ys) binding to muscle receptor sites (light blue cavities on the pink muscle), thus preventing ACh (gray circles) from binding to the muscle receptors and triggering movement.

There is a relationship between the thymus gland and MG. Approximately 65% of people with MG have an abnormal thymus. The thymus is responsible for immunological self-tolerance, which is the capacity to recognize self versus nonself during immunological responses. It is suspected that this loss of the ability to recognize self versus nonself leads to the autoimmune attack on acetylcholine receptors that occurs during MG.[4]

Assessment

The clinical course of MG is variable. Individuals may experience periods of exacerbation and remission of symptoms. MG is a chronic disease, and remissions are rarely permanent. Comprehensive nursing assessment of a client with MG includes a detailed medical history, symptom description, and ability to complete daily activities. The physical exam assesses voluntary muscles for muscle strength and fatigability to identify severity of specific muscle weakness and the degree of functional impairment.

Hallmark characteristics of MG include muscle weakness affecting the eyes, face, neck, jaw, respiratory, and extremity muscles. Weakness increases with repetitive use and improves after periods of rest or sleep. The following box summarizes common manifestations of MG.

Common Manifestations of MG[5]

Early symptoms are as follows:

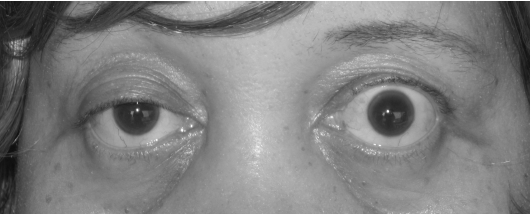

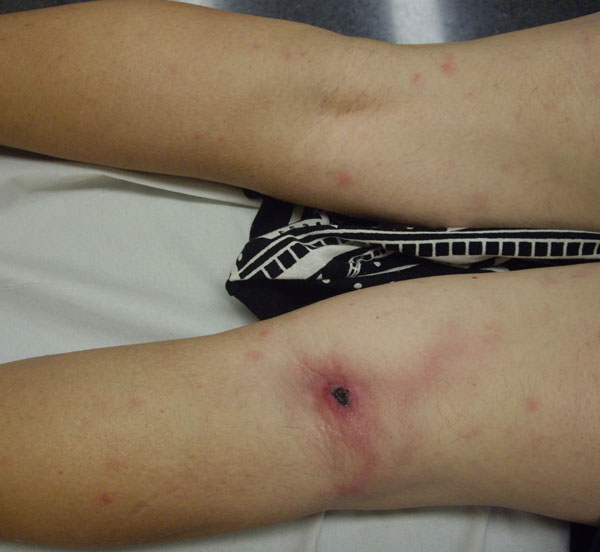

- Eye muscles with diplopia, double vision, and ptosis, drooping of the eyelids. (See Figure 9.30[6] for an image of ptosis.)

- Facial muscle weakness

- Generalized weakness

Ongoing symptoms include the following:

- Dysphonia (voice impairment) due to laryngeal muscle weakness

- Difficulty chewing foods

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), causing high risk for aspiration

- Facial muscle weakness causing a characteristic “myasthenia snarl”

- Dysarthria (difficulty speaking because of weak muscles)

- Neck and limb muscle weakness

- Respiratory muscle weakness leading to breathing difficulty and possible respiratory failure

- Loss of bowel and bladder control

Exacerbations (worsening of symptoms) may be caused by an illness (e.g., viral or respiratory infections), fever, surgery, emotional stress, pregnancy, and drugs that affect neuromuscular transmission.

Potential Complications: Myasthenic Crisis and Cholinergic Crisis

Myasthenic crisis is a medical emergency with respiratory failure due to respiratory muscle weakness. Other signs and symptoms of myasthenia crisis include increased generalized muscle weakness; hypertension; loss of cough and gag reflex; tachycardia; and pale, cool skin. Treatment includes maintaining adequate respiratory function and may require intubation. Neostigmine may be administered.

Cholinergic crisis is respiratory failure resulting from a high dose of cholinesterase inhibitors. Other signs and symptoms of cholinergic crisis include generalized and increased muscle weakness; constricted pupils; bradycardia; increased secretions; diarrhea; abdominal cramping; and red, warm skin. Atropine may be administered and repeated if indicated, resulting in rapid improvement.

See Table 9.11a. for a comparison of myasthenic crisis and cholinergic crisis.

Table 9.11a. Symptoms of MG

| Myasthenic Crisis | Cholinergic Crisis |

|---|---|

| Tachycardia | Bradycardia |

| Flaccid muscles (including respiratory muscles) | Same |

| Pale and cool skin | Red and warm skin |

| No GI changes | Diarrhea and abdominal cramps |

| No changes in secretions | Increased secretions |

| Improves on edrophonium diagnostic test | Worsens on edrophonium diagnostic test |

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Because MG affects acetylcholine, an acetylcholinesterase test, commonly referred to as a Tensilon test, is used to diagnose MG. The client is injected with an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChE) called edrophonium chloride. This injection stops the breakdown of acetylcholine, thereby increasing its availability at the neuromuscular junction. The medication acts quickly, within 30 seconds, and only lasts up to 5 minutes. If the client experiences immediate improvement in muscle strength with the injection, it is considered a positive test for MG. If the client does not show transient improvement in muscle strength or improvement of ptosis or respiratory symptoms, then the test results do not indicate MG. During this test, atropine should be available in the event that side effects occur. Side effects are rare but life-threatening and include bradycardia, asystole, and bronchoconstriction.[7]

An EMG may demonstrate a decrease in successive action potentials as the nerves are repetitively stimulated. Read more about the EMG test in the “General Assessment of the Nervous System” section. A CT scan or MRI may be performed to assess for thymus enlargement.

A blood test may be performed to determine if acetylcholine receptor antibodies are present.

Nursing Diagnosis

Myasthenia gravis is a chronic disease, so most clients are managed on an outpatient basis. However, they may be admitted to acute care if secondary conditions occur.

Common nursing diagnoses related to MG include the following[8]:

- Ineffective Airway Clearance related to weak oropharyngeal muscle contractions and decreased ability to cough and swallow

- Risk for Aspiration related to dysphagia and decreased gag reflex

- Fatigue related to disease process and muscular weakness

- Risk for Falls due to weakness and fatigue

Outcome Identification

Overall goals for clients with MG focus on functioning at an optimal level and reducing risk of complications. Sample outcome criteria include the following:

- The client will demonstrate effective coughing after the teaching session.

- The client will demonstrate safe swallowing techniques after the teaching session.

- The client will maintain normal breath sounds.

- The client will verbalize three strategies to manage fatigue after the teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical management is directed at improving muscle function through the administration of anticholinesterase medications and by reducing and removing circulating antibodies. Clients with MG are managed on an outpatient basis unless hospitalization is required for managing symptoms or complications such as a myasthenic crisis or cholinergic crisis.

Common medications used to manage MG are summarized in Table 9.11b.

Table 9.11b. Medications Used to Treat MG

| Medications | Mechanisms of Action and Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|

| Anticholinesterase Medications

Pyridostigmine bromide Neostigmine bromide Neostigmine methyl sulfate |

These drugs block the action of the enzyme anticholinesterase, producing improvement of symptoms.

Medications must be given on time to maintain stable blood levels. Delays in administration may exacerbate muscle weakness. May be administered intravenously if the client cannot take oral medication. |

| Immunosuppressants

Corticosteroids |

Prescribed if there is no improvement in symptoms from the anticholinesterase drugs to suppressing the client’s autoimmune response.

Goal of therapy is to reduce the number of abnormal antibodies and prevent them from attaching to ACh receptor sites. |

| Nonsteroidal Immunosuppressants

Azathioprine Cyclophosphamide |

Prescribed to suppress autoimmune activity when clients do not respond to corticosteroid therapy. Inhibits T lymphocytes and reduces acetylcholine receptor antibodies.

Can produce extreme immunosuppression and toxic side effects. Leukopenia and hepatotoxicity are serious adverse effects. Monitor white blood cell count and liver function tests. |

Nonpharmacologic management includes plasmapheresis (plasma exchange). During plasmapheresis, the client’s plasma and plasma components are removed, including the antibodies and then the cleansed plasma is returned to the client. This exchange produces a temporary reduction in the level of the acetylcholine circulating antibodies.

Surgical Management

Thymectomy (surgical removal of the thymus gland) may be performed to decrease the autoimmune response.

Physical, Occupational, Speech, and DietaryTherapy

Referral for physical, occupational, and speech therapy can provide a collaborative effort in meeting the complex needs of the client and ensure treatment directed at optimal functioning. Referrals to dieticians help improve nutritional intake for clients who have difficulty swallowing and eating.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for hospitalized clients with exacerbations of MG or myasthenia crisis are summarized in the following box.

Nursing Interventions for MG[9],[10]

- Monitor the ability to adequately cough and deep breathe.

- Monitor for respiratory failure.

- Maintain suctioning and emergency equipment at the bedside.

- Monitor vital signs.

- Monitor swallowing ability to prevent aspiration.

- Provide nutritional support with small, frequent meals; soft foods; and high-calorie snacks. Encourage the client to keep their chin down when swallowing and to sit up when eating.

- Assess muscle strength.

- Provide teaching on conserving strength and balancing activity/rest periods.

- Plan short activities that coincide with times of maximal muscle strength.

- Encourage rest to reduce fatigue that may trigger a crisis.

- Reposition frequently to prevent pressure injuries.

- Monitor for myasthenic and cholinergic crisis.

- Provide artificial tears during the day. May use eye patch to prevent corneal damage.

- Administer anticholinesterase medications as prescribed.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide health teaching on health promotion to achieve optimal functioning and prevent complications from occurring. Topics include the following:

- Emphasize the importance of rest and avoidance of fatigue to prevent exacerbations. Be alert to other factors that can cause exacerbations, such as infection, surgery, pregnancy, and exposure to extreme temperatures.

- Instruct the client and family about drug actions and side effects.

- Some medications should be avoided or used cautiously because they can worsen symptoms, such as calcium channel blockers, certain classes of antibiotics, hormonal contraceptives, statins, antacids and laxatives that contain magnesium, and transdermal nicotine.

- Take medication in a timely manner. It is advisable to time the dose one hour before meals for optimal chewing and swallowing. Instruct the client to inform the dentist, ophthalmologist, and pharmacist of their MG diagnosis.

- Instruct clients about the symptoms that require emergency treatment.

- Encourage clients to locate a neurologist familiar with MG management.

- Advise clients to wear a medical bracelet identifying the diagnosis of MG. Suggest an “emergency code” to alert family if they are too weak to speak (such as ringing the phone twice and hanging up).

- Instruct the family about cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques, performance of the Heimlich maneuver, and EMS activation.

- Refer the client to a vocational rehabilitation center for guidance for modifying the home or work environment, such as a raised seat and handrail for the toilet.

- Advise clients to schedule appropriate annual health screenings and maintain recommended vaccinations.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with a family member or other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

View a supplementary Wikimedia video[11] on MG: Myasthenia-gravis.

![]() RN Recap: Myasthenia Gravis

RN Recap: Myasthenia Gravis

View a brief YouTube video overview of myasthenia gravis[12]:

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2023, November). Myasthenia gravis. National Institutes of Health. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/myasthenia-gravis ↵

- Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Pharmacology and Toxicology by Čolović, Krstić, Lazarević-Pašti, Bondžić, & Vasić is licensed under CC BY 2.5 ↵

- “Wikipedia_Project_Myasthenia_gravis_(5).svg” by Libbyspek is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. (2013). Care of the patient with myasthenia gravis. https://aann.org/uploads/Publications/CPGs/AANN14_CPGMysGravis.pdf ↵

- American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. (2013). Care of the patient with myasthenia gravis. https://aann.org/uploads/Publications/CPGs/AANN14_CPGMysGravis.pdf ↵

- “Ptosis_myasthenia_gravis.jpg” by Mohankumar Kurukumbi, Roger L Weir, Janaki Kalyanam, Mansoor Nasim, Annapurni Jayam-Trouth is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Rousseff, R. T. (2021). Diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10(8), 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081736 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Howard, J. F., Jr. (Ed.). (2009). Myasthenia gravis: A manual for the health care provider. https://myasthenia.org/Portals/0/Provider%20Manual_ibook%20version.pdf ↵

- American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. (2013). Care of the patient with myasthenia gravis. https://aann.org/uploads/Publications/CPGs/AANN14_CPGMysGravis.pdf ↵

- Osmosis.org. (2016, December 12). Myasthenia-gravis.webm [Video]. Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Myasthenia-gravis.webm ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 9 - Myasthenia gravis [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/Wbnvm2xCJPY?si=XO91PBIAwYcSdxHD ↵

In addition to using standard precautions and transmission-based precautions, aseptic technique (also called medical asepsis) is the purposeful reduction of pathogens to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another during a medical procedure. For example, a nurse administering parenteral medication or performing urinary catheterization uses aseptic technique. When performed properly, aseptic technique prevents contamination and transfer of pathogens to the patient from caregiver hands, surfaces, and equipment during routine care or procedures. The word “aseptic” literally means an absence of disease-causing microbes and pathogens. In the clinical setting, aseptic technique refers to the purposeful prevention of microbe contamination from one person or object to another. These potentially infectious, microscopic organisms can be present in the environment, on an instrument, in liquids, on skin surfaces, or within a wound.

There is often misunderstanding between the terms aseptic technique and sterile technique in the health care setting. Both asepsis and sterility are closely related, and the shared concept between the two terms is removal of harmful microorganisms that can cause infection. In the most simplistic terms, asepsis is creating a protective barrier from pathogens, whereas sterile technique is a purposeful attack on microorganisms. Sterile technique (also called surgical asepsis) seeks to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while also maintaining objects as free from microorganisms as possible. It is the standard of care for surgical procedures, invasive wound management, and central line care. Sterile technique requires a combination of meticulous hand washing, creation of a sterile field, using long-lasting antimicrobial cleansing agents such as betadine, donning sterile gloves, and using sterile devices and instruments.

Principles of Aseptic Non-Touch Technique

Aseptic non-touch technique (ANTT) is the most commonly used aseptic technique framework in the health care setting and is considered a global standard. There are two types of ANTT: surgical-ANTT (sterile technique) and standard-ANTT.

Aseptic non-touch technique starts with a few concepts that must be understood before it can be applied. For all invasive procedures, the “ANTT-approach” identifies key parts and key sites throughout the preparation and implementation of the procedure. A key part is any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs, syringe tips, needles, and dressings. A key site is any nonintact skin, potential insertion site, or access site used for medical devices connected to the patients. Examples of key sites include open wounds and insertion sites for intravenous (IV) devices and urinary catheters.

ANTT includes four underlying principles to keep in mind while performing invasive procedures:

- Always wash hands effectively.

- Never contaminate key parts.

- Touch non-key parts with confidence.

- Take appropriate infective precautions.

Preparing and Preventing Infections Using Aseptic Technique

When planning for any procedure, careful thought and preparation of many infection control factors must be considered beforehand. While keeping standard precautions in mind, identify anticipated key sites and key parts to the procedure. Consider the degree to which the environment must be managed to reduce the risk of infection, including the expected degree of contamination and hazardous exposure to the clinician. Finally, review the expected equipment needed to perform the procedure and the level of key part or key site handling. See Table 4.3 for an outline of infection control measures when performing a procedure.

Table 4.3 Infection Control Measures When Performing Procedures

| Infection Control Measure | Key Considerations | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental control |

|

|

| Hand hygiene |

|

|

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) |

|

|

| Aseptic field management | Determine level of aseptic field needed and how it will be managed before the procedure begins:

|

General aseptic field:

IV irrigation Dry dressing changes Critical aseptic field: Urinary catheter placement Central line dressing change Sterile dressing change |

| Non-touch technique |

|

|

| Sequencing |

|

|

Use of Gloves and Sterile Gloves

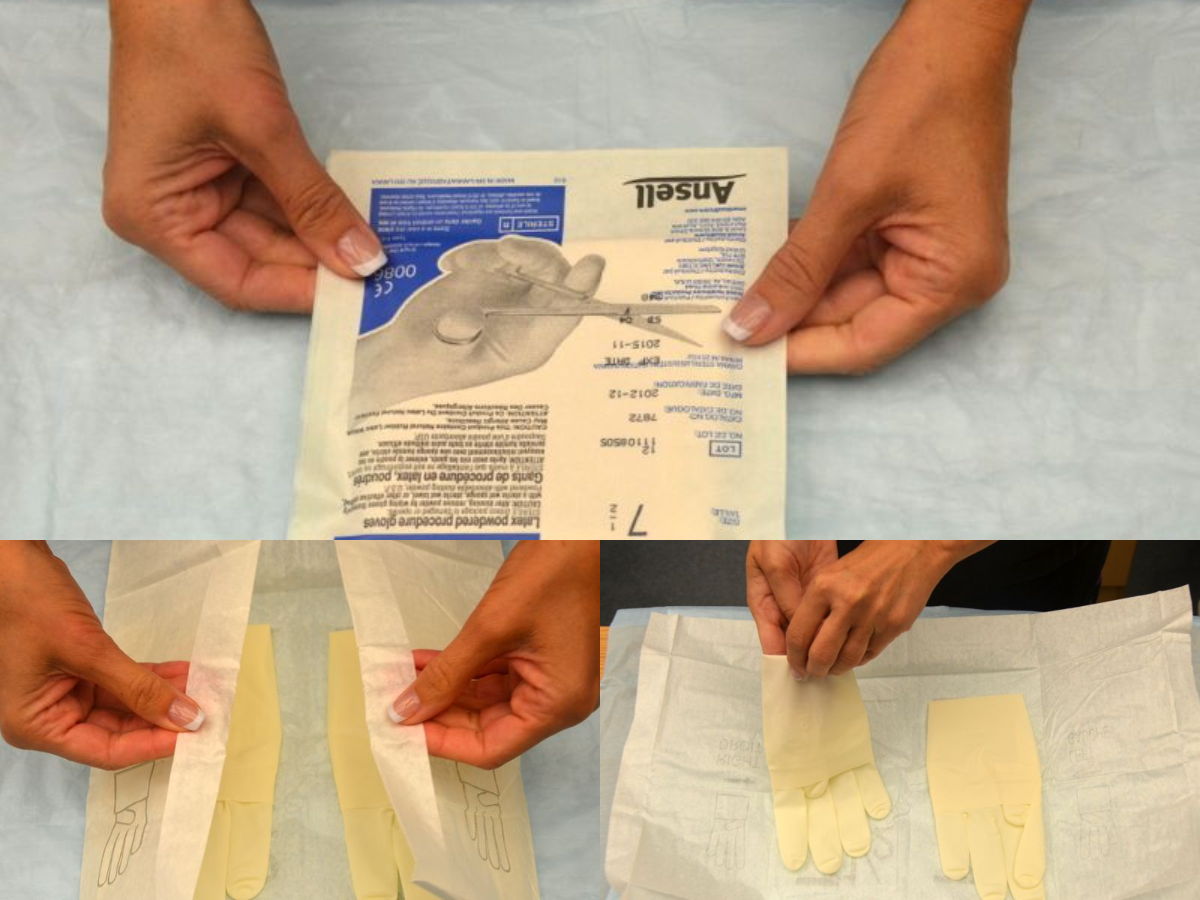

There are two different levels of medical-grade gloves available to health care providers: clean (exam) gloves and sterile (surgical) gloves. Generally speaking, clean gloves are used whenever there is a risk of contact with body fluids or contaminated surfaces or objects. Examples include starting an intravenous access device or emptying a urinary catheter collection bag. Alternatively, sterile gloves meet FDA requirements for sterilization and are used for invasive procedures or when contact with a sterile site, tissue, or body cavity is anticipated. Sterile gloves are used in these instances to prevent transient flora and reduce resident flora contamination during a procedure, thus preventing the introduction of pathogens. For example, sterile gloves are required when performing central line dressing changes, insertion of urinary catheters, and during invasive surgical procedures. See Figure 4.15[1] for images of a nurse opening and removing sterile gloves from packaging.

See the “Checklist for Applying and Removing Sterile Gloves” for details on how to apply sterile gloves.

Applying Sterile Gloves on YouTube[2]

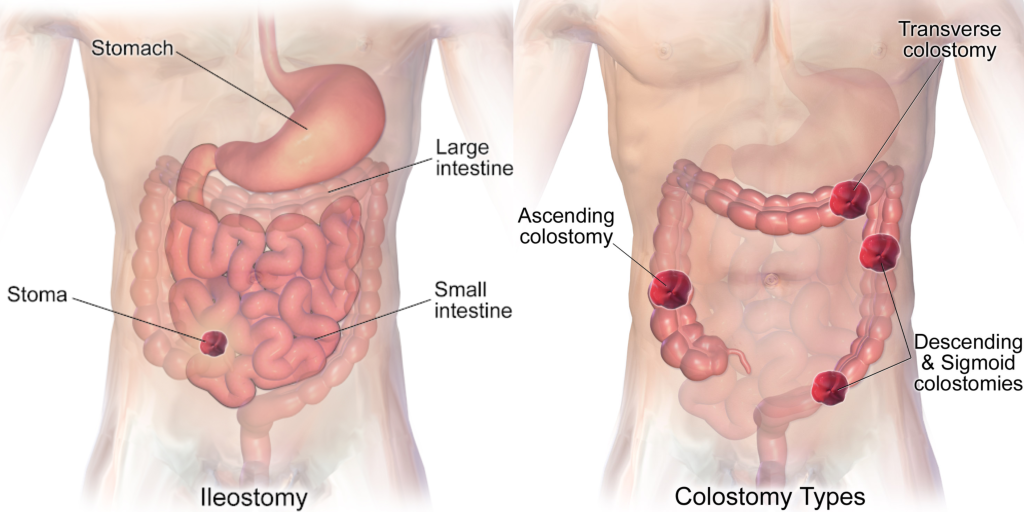

An ostomy is the surgical procedure that creates an opening (stoma) from an area inside the body to the outside of the body. In ostomies related to elimination, a stoma is an opening on the abdomen that is connected to the gastrointestinal or urinary system to allow waste (i.e., urine or feces) to be collected in a pouch. See Figure 21.14[3] for an image of a stoma. A stoma can be permanent, such as when an organ is removed, or temporary, such as when an organ requires time to heal. Ostomies are created for patients with conditions such as cancer of the bowel or bladder, inflammatory bowel diseases, or perforation of the colon.

There are several different kinds of ostomies related to elimination. Common types of ostomies include the following:

- Ileostomy: The lower end of the small intestine (ileum) is attached to a stoma to bypass the colon, rectum, and anus.

- Colostomy: The colon is attached to a stoma to bypass the rectum and the anus.

- Urostomy: The ureters (tubes that carry urine from the kidney to the bladder) are attached to a stoma to bypass the bladder.[4]

See Figure 21.15[5] comparing the anatomical locations of ileostomies and various sites of colostomies. It is important for the nurse to understand the site of a patient’s colostomy because the site impacts the characteristics of the waste. For example, due to the natural digestive process of the colon and absorption of water, waste from an ileostomy or a colostomy placed in the anterior ascending colon will be watery compared to waste from an ostomy placed in the descending colon.

The tissue of a stoma is very delicate. Immediately after surgery, a stoma is swollen, but it will shrink in size over several weeks. A healthy, healed stoma appears moist and dark red or pink in color. Stomas that are swollen; dry; have malodorous discharge; or are bluish, purple, black, or pale should be reported to the provider. The skin surrounding a stoma can easily become irritated from the pouch adhesive or leakage of fluid from the stoma, so the nurse must perform interventions to prevent skin breakdown. Any identified signs of skin breakdown should be reported to the provider.[6]

Stoma appliances are supplied as a one- or two-piece set. A two-piece set consists of an ostomy barrier (also called a wafer) and a pouch. The ostomy barrier is the part of the appliance that sticks to the skin with a hole that is fitted around the stoma. The pouch collects the waste and must be emptied regularly. It attaches to the ostomy barrier in a clicking motion to secure the two parts, similar to how a plastic storage container cover snaps to a container to create a seal. The pouching system must be completely sealed to prevent leaking of the waste and to protect the surrounding peristomal skin. The pouch has an end with an opening where the waste is drained and is closed using a plastic clip or VelcroTM strip.[7] In a one-piece stoma appliance set, the ostomy barrier and the pouch are one piece. See Figure 21.16[8] for an image of a stoma with an ostomy barrier in place. See Figure 21.17[9] for an image of a patient with an ileostomy appliance with a pouch attached.

Individuals with colostomies, ileostomies, and urostomies have no sensation and no control over the output of the stoma. Depending on the type of system, the ostomy appliance can last from four to seven days, but the pouch must be changed if there is leaking, odor, excessive skin exposure, or itching or burning under the skin barrier. Patients with pouches can swim and take showers with the pouching system on.[10]

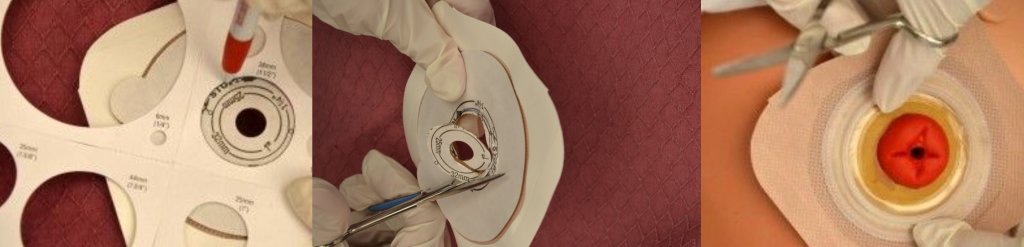

When changing an ostomy appliance, the ostomy barrier is cut to fit closely around the stoma without impinging on it. See the "Checklist for Ostomy Appliance Change" for detailed instructions. The nurse measures the stoma with a template and then cuts and fits the ostomy barrier to a size that is 2 mm larger than the stoma.[11] See Figure 21.18[12] for an image of a nurse measuring and cutting the ostomy barrier to fit around a stoma.

After the skin barrier is applied to the skin, the pouch is snapped to the barrier. See Figure 21.19[13] for an image of applying the pouch.

Physical and Emotional Assessment

Patients may have other medical conditions that affect their ability to manage their ostomy care. Conditions such as arthritis, vision changes, Parkinson’s disease, or post-stroke complications can hinder a patient’s coordination and ability to manage the ostomy. In addition, the emotional burden of coping with an ostomy may be devastating for some patients and may affect their self-esteem, body image, quality of life, and ability to be intimate. It is common for patients with ostomies to struggle with body image and their altered pattern of elimination. Nurses can promote healthy coping by ensuring the patient has appropriate referrals to a wound/ostomy nurse specialist, a social worker, and support groups. Nurses should also be aware of their nonverbal cues when assisting a patient with their appliance changes. It is vital not to show signs of disgust at the appearance of the ostomy or at the odor that may be present when changing an appliance or pouching system.[14]

View a supplementary YouTube video on Changing an Ostomy Pouch[15]

Urostomy Care

A urostomy is similar to a colostomy, but it is an artificial opening for passing urine. Urostomies are surgically created due to medical conditions such as bladder cancer, removal of the bladder, trauma, spinal cord injuries, or congenital abnormalities.

A urostomy patient has no voluntary control of urine, so the pouching system must be emptied regularly. Many patients empty their urostomy bag every two to four hours or when the pouch becomes one-third full. The pouch may also be attached to a drainage bag for overnight drainage. Patients with a urostomy are at risk for urinary tract infections (UTIs), so it is important to educate them regarding the signs and symptoms of an infection.

When preparing to insert an indwelling urinary catheter, it is important to use the nursing process to plan and provide care to the patient. Begin by assessing the appropriateness of inserting an indwelling catheter according to CDC criteria as discussed in the “Preventing CAUTI” section of this chapter. Determine if alternative measures can be used to facilitate elimination and address any concerns with the prescribing provider before proceeding with the provider order.

Subjective Assessment

In addition to verifying the appropriateness of the insertion of an indwelling catheter according to CDC recommendations, it is also important to assess for any conditions that may interfere with the insertion of a urinary catheter when feasible. See suggested interview questions prior to inserting an indwelling catheter and their rationale in Table 21.8a.

Table 21.8a Suggested Interview Questions Prior to Urinary Catheterization

| Interview Questions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Do you have any history of urinary problems such as frequent urinary tract infections, urinary tract surgeries, or bladder cancer?

For males: Do you have any history of prostate enlargement or prostate problems? For females: Have you had any gynecological surgeries? |

Previous medical conditions and surgeries may interfere with urinary catheter placement. Information about a male patient’s prostate will assist in determining the size and type of catheter used. (Recall that using a catheter with a coude tip is helpful when a male patient has an enlarged prostate.) If a patient has a history of previous urinary tract infections, they may be at higher risk of developing CAUTI. |

| Have you ever had a urinary catheter placed in the past? If so, were there any problems with placement or did you experience any problems while the catheter was in place? | Questioning the patient about placement and prior catheterizations assists the nurse in identifying any problems with catheterization or if the patient has had the procedure before, they may know what to expect. |

| Do you have any questions about this procedure? How do you feel about undergoing catheterization? | The nurse should encourage patient involvement with their care and identify any fears or anxiety. Nurses can decrease or eliminate these fears and anxieties with additional information or reassurance. |

| Do you take any medications that increase urination such as diuretics or any medications that decrease urgency or frequency? If so, please describe. | Identifying medications that increase or decrease urine output is important to consider when monitoring urine output after the catheter is in place. |

| Have you had any orthopedic surgeries that may affect your ability to bend your knees or hips? Are you able to tolerate lying flat for a short period of time? | The patient may not be able to tolerate the positioning required for catheter insertion. If so, additional assistance from other staff may be required for patient comfort and safety. |

Cultural Considerations

When inserting urinary catheters, be aware of and respect cultural beliefs related to privacy, family involvement, and the request for a same-gender nurse. Inserting a urinary catheter requires visualization and manipulation of anatomical areas that are considered private by most patients. These procedures can cause emotional distress, especially if the patient has experienced any history of abuse or trauma.

Objective Assessment

In addition to performing a subjective assessment, there are several objective assessments to complete prior to insertion. See Table 21.8b for a list of objective assessments and their rationale.

Table 21.8b Objective Assessment

| Objective Data Collection | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Review the patient’s medical record for any documented medical conditions the patient may not have reported, such as urethral strictures, structural problems with the bladder or urethra, or frequent urinary tract infections. | Any type of obstruction or scar tissue within these areas may prevent the catheter from advancing into the bladder. |

| Analyze the patient's weight and most recent electrolyte values. | Weight is used to determine a patient's fluid status, especially if they have fluid overload. Electrolyte levels are also affected by fluid balance and the use of diuretic medications. Establish a baseline to use to evaluate outcomes after placing the urinary catheter. |

| Determine the patient's level of consciousness, ability to cooperate, developmental level, and age. | Evaluate the patient’s ability to follow directions and cooperate during the procedure and seek additional assistance during the procedure if needed. This data will impact how to explain the procedure to the patient. |

| Perform physical assessment of the bladder and perineum. Palpate the bladder for signs of fullness and discomfort. (Bladder emptying may also be assessed using a bladder scanner per agency policy). Inspect the perineum for erythema, discharge, drainage, skin ulcerations, or odor. Note the position of anatomical landmarks. For example, in females identify the urethra versus the vaginal opening. | A full bladder produces discomfort and urgency to void, especially on palpation. These symptoms should be relieved with the placement of a urinary catheter.

Identify any abnormal physical signs in the perineal area that may interfere with comfort during insertion. Determining the urethral opening improves accuracy and ease of insertion. |

| When examining the perineal area, note the approximate diameter of the urinary meatus. Choose the smallest, appropriately sized diameter catheter. | An appropriately sized catheter is important to avoid unnecessary discomfort or trauma to the urinary tissue. Catheters that are 14 French diameter are typically used in adults. |

Life Span Considerations

Children

It is often helpful to explain the catheterization procedure using a doll or toy. According to agency policy, a parent, caregiver, or other adult should be present in the room during the procedure. Asking a younger child to blow into a straw can help relax the pelvic muscles during catheterization.

Older Adults

The urethral meatus of older women may be difficult to identify due to atrophy of the urogenital tissue. The risk of developing a urinary tract infection may also be increased due to chronic disease and incontinence.

Expected Outcomes/Planning

Expected patient outcomes following urinary catheterization should be planned and then evaluated and documented after the procedure is completed. See Table 21.8c for sample expected outcomes related to urinary catheterization.

Table 21.8c Expected Outcomes of Urinary Catheterization

| Expected Outcomes | Rationale |

|---|---|

| The patient’s bladder is nondistended and not palpable. | Verifies appropriate bladder emptying. |

| The patient reports no abdominal or bladder discomfort or pressure. | Verifies correct catheter placement by allowing urine flow and relieving discomfort or pressure. |

| Urine output is at least 30 mL/hr. | Verifies correct catheter placement and appropriate kidney functioning. If urine output is less than 30 mL/hour, check tubing for kinking and obstruction, and notify the provider if there is no improvement after manipulating the tubing. |

| Patient verbalizes understanding of the purpose of the catheter and signs of a urinary tract infection to report. | Verifies the patient's understanding of the procedure and signs of complications. |

Implementation

When inserting an indwelling urinary catheter, the expected finding is that the catheter is inserted accurately and without discomfort, and immediate flow of clear, yellow urine into the collection bag occurs. However, unexpected events and findings can occur. See Table 21.8d for examples of unexpected findings and suggested follow-up actions.

Table 21.8d Unexpected Findings and Follow-Up Actions

| Unexpected Findings | Follow-Up Action |

|---|---|

| Urine flow does not occur when catheterizing a female patient. | The catheter may have entered the vagina and not the urethral meatus. Leave the catheter in the vagina as a landmark to avoid incorrect reinsertion. Obtain a new catheter kit and cleanse the urinary meatus again before reinsertion. If reinsertion is successful into the bladder, remove the catheter that is in vagina after the second attempt. |

| Sterile field is broken during the procedure. | If supplies or the catheter become contaminated, obtain a new catheter kit and restart the procedure. |

| Patient reports continued bladder pain or discomfort although urinary flow indicates correct catheter placement. | Ensure there is no tension pulling at the catheter. It may be helpful to deflate the balloon and advance the catheter another 2-3 inches to ensure it is in the bladder and not the urethra. If these actions do not resolve the discomfort, notify the provider because it is possible the patient is experiencing bladder spasms. Continue to monitor urine output for clarity, color, and amount and for signs of urinary tract infection. |

| The nurse is unable to advance the catheter on a male patient with an enlarged prostate. | Do not force advancement because this may cause further damage. Ask the patient to take deep breaths and try again. If a second attempt is unsuccessful, obtain a coude catheter and attempt to reinsert. If unsuccessful with a coude catheter, notify the provider. |

| Urine is cloudy, concentrated, malodorous, dark amber in color, or contains sediment, blood, or pus. | Notify the health care provider of signs and symptoms of a possible urinary tract infection. Obtain a urine specimen as prescribed. |

Evaluation

Evaluate the success of the expected outcomes established prior to the procedure.

Sample Documentation for Expected Findings

A size 14F Foley catheter inserted per provider prescription. Indication: Prolonged urinary retention. Procedure and purpose of Foley catheter explained to patient. Patient denies allergies to iodine, orthopedic limitations, or previous genitourinary surgeries. Balloon inflated with 10 mL of sterile water. Patient verbalized no discomfort or pain with balloon inflation or during the procedure. Peri-care provided before and after procedure. Catheter tubing secured to right upper thigh with stat lock. Drainage bag attached, tubing coiled loosely with no kinks, bag is below bladder level on bed frame. Urine drained with procedure 375 mL. Urine is clear, amber in color, no sediment. Patient resting comfortably; instructed the patient to notify the nurse if develops any bladder pain, discomfort, or spasms. Patient verbalized understanding.

Sample Documentation for Unexpected Findings

A size 14F Foley catheter inserted per provider prescription. Indication is for oliguria with accurate output measurements required. Procedure and purpose of Foley catheter explained to patient. Patient denies allergies to iodine, orthopedic limitations, or previous genitourinary surgeries. As the balloon was being inflated with sterile water, patient began to report discomfort. Water removed, catheter advanced one inch and balloon reinflated with 10 mL of sterile water. Patient denied discomfort after the catheter advancement. Catheter tubing secured to right upper thigh with stat lock. Drainage bag attached, tubing coiled loosely with no kinks, bag is below bladder level. Urine drained with procedure 100 mL. Urine is dark amber, noticeable sediment in tubing, with foul odor. Patient resting comfortably, denies any bladder pain or discomfort. Instructed the patient to notify the nurse if develops any bladder pain, discomfort, or urinary spasms. Patient verbalized understanding. Notify the health care provider of urine assessment. Continue monitoring patient for any new or worsening symptoms such as change in mental status, fever, chills, or hematuria.

Learning Objectives

- Perform a respiratory assessment

- Differentiate between normal and abnormal lung sounds

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report deviations from norms

The evaluation of the respiratory system includes collecting subjective and objective data through a detailed interview and physical examination of the thorax and lungs. This examination can offer significant clues related to issues associated with the body's ability to obtain adequate oxygen to perform daily functions. Inadequacy in respiratory function can have significant implications for the overall health of the patient.

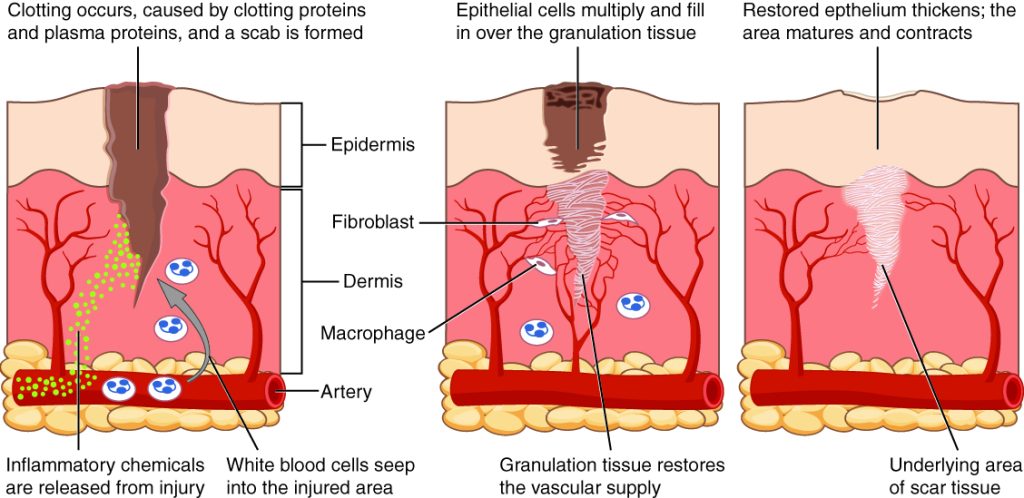

Phases of Wound Healing

When skin is injured, there are four phases of wound healing that take place: hemostasis, inflammatory, proliferative, and maturation.[16] See Figure 20.1[17] for an illustration of the phases of wound healing.

To illustrate the phases of wound healing, imagine that you accidentally cut your finger with a knife as you were slicing an apple. Immediately after the injury occurs, blood vessels constrict, and clotting factors are activated. This is referred to as the hemostasis phase. Clotting factors form clots that stop the bleeding and act as a barrier to prevent bacterial contamination. Platelets release growth factors that alert various cells to start the repair process at the wound location. The hemostasis phase lasts up to 60 minutes, depending on the severity of the injury.[18],[19]

After the hemostasis phase, the inflammatory phase begins. Vasodilation occurs so that white blood cells in the bloodstream can move into the wound to start cleaning the wound bed. The inflammatory process appears to the observer as edema (swelling), erythema (redness), and exudate. Exudate is fluid that oozes out of a wound, also commonly called pus.[20],[21]

The proliferative phase begins within a few days after the injury and includes four important processes: epithelialization, angiogenesis, collagen formation, and contraction. Epithelialization refers to the development of new epidermis and granulation tissue. Granulation tissue is new connective tissue with new, fragile, thin-walled capillaries. Collagen is formed to provide strength and integrity to the wound. At the end of the proliferation phase, the wound begins to contract in size.[22],[23]

Capillaries begin to develop within the wound 24 hours after injury during a process called angiogenesis. These capillaries bring more oxygen and nutrients to the wound for healing. When performing dressing changes, it is essential for the nurse to protect this granulation tissue and the associated new capillaries. Healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is also moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered by shiny white or yellow fibrous tissue referred to as biofilm that must be removed because it impedes healing. Unhealthy granulation tissue is often caused by an infection, so wound cultures should be obtained when infection is suspected. The provider can then prescribe appropriate antibiotic treatment based on the culture results.[24]

During the maturation phase, collagen continues to be created to strengthen the wound. Collagen contributes strength to the wound to prevent it from reopening. A wound typically heals within 4-5 weeks and often leaves behind a scar. The scar tissue is initially firm, red, and slightly raised from the excess collagen deposition. Over time, the scar begins to soften, flatten, and become pale in about nine months.[25]

Types of Wound Healing

There are three types of wound healing: primary intention, secondary intention, and tertiary intention. Healing by primary intention means that the wound is sutured, stapled, glued, or otherwise closed so the wound heals beneath the closure. This type of healing occurs with clean-edged lacerations or surgical incisions, and the closed edges are referred to as approximated. See Figure 20.2[26] for an image of a surgical wound healing by primary intention.

Secondary intention occurs when the edges of a wound cannot be approximated (brought together), so the wound fills in from the bottom up by the production of granulation tissue. Examples of wounds that heal by secondary intention are pressure injuries and chainsaw injuries. Wounds that heal by secondary intention are at higher risk for infection and must be protected from contamination. See Figure 20.3[27] for an image of a wound healing by secondary intention.

Tertiary intention refers to a wound that has had to remain open or has been reopened, often due to severe infection. The wound is typically closed at a later date when infection has resolved. Wounds that heal by secondary and tertiary intention have delayed healing times and increased scar tissue.

Wound Closures

Lacerations and surgical wounds are typically closed with sutures, staples, or dermabond to facilitate healing by primary intention. See Figure 20.4[28] for an image of sutures, Figure 20.5[29] for an image of staples, and Figure 20.6[30] for an image of a wound closed with dermabond, a type of sterile surgical glue. Based on agency policy, the nurse may remove sutures and staples based on a provider order. See Figure 20.7[31] for an image of a disposable staple remover. See the checklists in the subsections later in this chapter for procedures related to surgical and staple removal.

Common Types of Wounds

There are several different types of wounds. It is important to understand different types of wounds when providing wound care because each type of wound has different characteristics and treatments. Additionally, treatments that may be helpful for one type of wound can be harmful for another type. Common types of wounds include skin tears, venous ulcers, arterial ulcers, diabetic foot wounds, and pressure injuries.[32]

Skin Tears

Skin tears are wounds caused by mechanical forces such as shear, friction, or blunt force. They typically occur in the fragile, nonelastic skin of older adults or in patients undergoing long-term corticosteroid therapy. Skin tears can be caused by the simple mechanical force used to remove an adhesive bandage or from friction as the skin brushes against a surface. Skin tears occur in the epidermis and dermis but do not extend through the subcutaneous layer. The wound bases of skin tears are typically fragile and bleed easily.[33]

Venous Ulcers

Venous ulcers are caused by lack of blood return to the heart causing pooling of fluid in the veins of the lower legs. The resulting elevated hydrostatic pressure in the veins causes fluid to seep out, macerate the skin, and cause venous ulcerations. Maceration refers to the softening and wasting away of skin due to excess fluid. Venous ulcers typically occur on the medial lower leg and have irregular edges due to the maceration. There is often a dark-colored discoloration of the lower legs, due to blood pooling and leakage of iron into the skin called hemosiderin staining. For venous ulcers to heal, compression dressings must be used, along with multilayer bandage systems, to control edema and absorb large amounts of drainage.[34] See Figure 20.8[35] for an image of a venous ulcer.

Arterial Ulcers

Arterial ulcers are caused by lack of blood flow and oxygenation to tissues. They typically occur in the distal areas of the body such as the feet, heels, and toes. Arterial ulcers have well-defined borders with a “punched out” appearance where there is a localized lack of blood flow. They are typically painful due to the lack of oxygenation to the area. The wound base may become necrotic (black) due to tissue death from ischemia. Wound dressings must maintain a moist environment, and treatment must include the removal of necrotic tissue. In severe arterial ulcers, vascular surgery may be required to reestablish blood supply to the area.[36] See Figure 20.9[37] for an image of an arterial ulcer on a patient’s foot.

Diabetic Ulcers

Diabetic ulcers are also called neuropathic ulcers because peripheral neuropathy is commonly present in patients with diabetes. Peripheral neuropathy is a medical condition that causes decreased sensation of pain and pressure, especially in the lower extremities. Diabetic ulcers typically develop on the plantar aspect of the feet and toes of a patient with diabetes due to lack of sensation of pressure or injury. See Figure 20.10[38] for an image of a diabetic ulcer. Wound healing is compromised in patients with diabetes due to the disease process. In addition, there is a higher risk of developing an infection that can reach the bone requiring amputation of the area. To prevent diabetic ulcers from occurring, it is vital for nurses to teach meticulous foot care to patients with diabetes and encourage the use of well-fitting shoes.[39]

Pressure Injuries

Pressure injuries are defined as “localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.”[40] Shear occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue. For example, when a patient slides down in bed, the outer skin remains immobile because it remains attached to the sheets due to friction, but deeper tissue attached to the bone moves as the patient slides down. This opposing movement of the outer layer of skin and the underlying tissues causes the capillaries to stretch and tear, which then impacts the blood flow and oxygenation of the surrounding tissues.

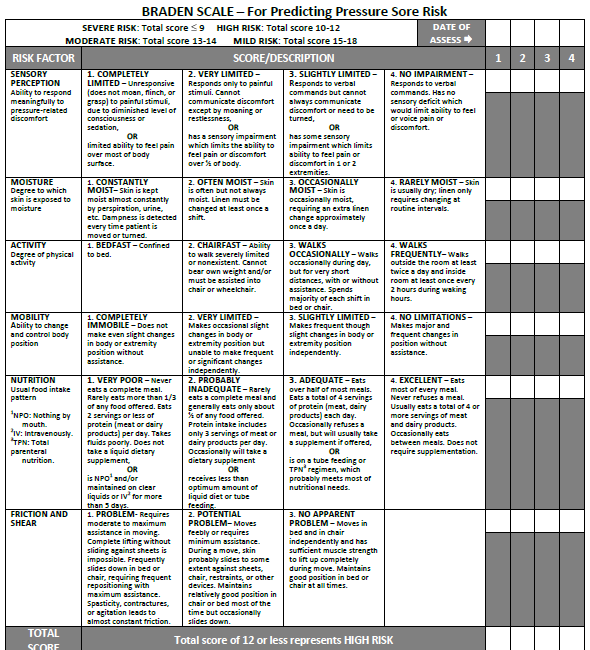

Braden Scale

Several factors place a patient at risk for developing pressure injuries, including nutrition, mobility, sensation, and moisture. The Braden Scale is a tool commonly used in health care to provide an objective assessment of a patient’s risk for developing pressure injuries. See Figure 20.11[41] for an image of a Braden Scale. The six risk factors included on the Braden Scale are sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear, and these factors are rated on a scale from 1-4 with 1 being “completely limited” to 4 being “no impairment.” The scores from the six categories are added, and the total score indicates a patient’s risk for developing a pressure injury. A total score of 15-19 indicates mild risk, 13-14 indicates moderate risk, 10-12 indicates high risk, and less than or equal to 9 indicates severe risk. Nurses create care plans using these scores to plan interventions that prevent or treat pressure injuries.

For more information about using the Braden Scale, go to the “Integumentary” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook.

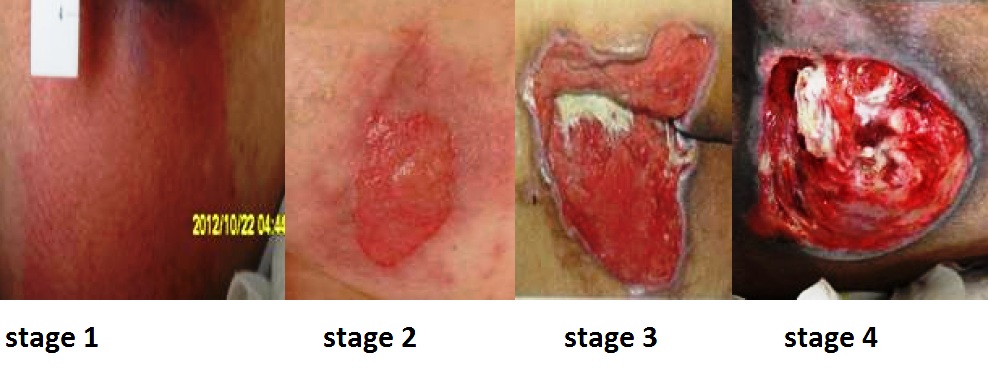

Staging

Pressure injuries commonly occur on the sacrum, heels, ischial tuberosity, and coccyx. The 2016 National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Pressure Injury Staging System now uses the term “pressure injury” instead of pressure ulcer because an injury can occur without an ulcer present. Pressure injuries are staged from 1 through 4 based on the extent of tissue damage. For example, Stage 1 pressure injuries have reddened but intact skin, and Stage 4 pressure injuries have deep, open ulcers affecting underlying tissue and structures such as muscles, ligaments, and tendons. See Figure 20.12[42] for an image of the four stages of pressure injuries.[43] The NPUAP’s definitions of the four stages of pressure injuries are described below:

- Stage 1 pressure injuries are intact skin with a localized area of nonblanchable erythema where prolonged pressure has occurred. Nonblanchable erythema is a medical term used to describe skin redness that does not turn white when pressed.

- Stage 2 pressure injuries are partial-thickness loss of skin with exposed dermis. The wound bed is viable and may appear like an intact or ruptured blister. Stage 2 pressure injuries heal by reepithelialization and not by granulation tissue formation.[44]

- Stage 3 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss in which fat is visible, but cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, and bone are not exposed. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location. Undermining and tunneling may occur in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound's edge. Tunneling refers to passageways underneath the surface of the skin that extend from a wound and can take twists and turns. Slough and eschar may also be present in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Slough is an inflammatory exudate that is usually light yellow, soft, and moist. Eschar is dark brown/black, dry, thick, and leathery dead tissue. See Figure 20.13 [45] for an image of eschar in the center of the wound. If slough or eschar obscures the wound so that tissue loss cannot be assessed, the pressure injury is referred to as unstageable.[46] In most wounds, slough and eschar must be removed by debridement for healing to occur.

- Stage 4 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss like Stage 3 pressure injuries, but also have exposed cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, or bone. Osteomyelitis (bone infection) may be present.[47]

View a supplementary YouTube video on Pressure Injuries[48]

Factors Affecting Wound Healing

Multiple factors affect a wound’s ability to heal and are referred to as local and systemic factors. Local factors refer to factors that directly affect the wound, whereas systemic factors refer to the overall health of the patient and their ability to heal. Local factors include localized blood flow and oxygenation of the tissue, the presence of infection or a foreign body, and venous sufficiency. Venous insufficiency is a medical condition where the veins in the legs do not adequately send blood back to the heart, resulting in a pooling of fluids in the legs.[49]

Systemic factors that affect a patient’s ability to heal include nutrition, mobility, stress, diabetes, age, obesity, medications, alcohol use, and smoking.[50] When a nurse is caring for a patient with a wound that is not healing as anticipated, it is important to further assess for the potential impact of these factors:

- Nutrition. Nutritional deficiencies can have a profound impact on healing and must be addressed for chronic wounds to heal. Protein is one of the most important nutritional factors affecting wound healing. For example, in patients with pressure injuries, 30 to 35 kcal/kg of calorie intake with 1.25 to 1.5g/kg of protein and micronutrients supplementation is recommended daily.[51] In addition, vitamin C and zinc deficiency have many roles in wound healing. It is important to collaborate with a dietician to identify and manage nutritional deficiencies when a patient is experiencing poor wound healing.[52]

- Stress. Stress causes an impaired immune response that results in delayed wound healing. Although a patient cannot necessarily control the amount of stress in their life, it is possible to control one’s reaction to stress with healthy coping mechanisms. The nurse can help educate the patient about healthy coping strategies.

- Diabetes. Diabetes causes delayed wound healing due to many factors such as neuropathy, atherosclerosis (a buildup of plaque that obstructs blood flow in the arteries resulting in decreased oxygenation of tissues), a decreased host immune resistance, and increased risk for infection.[53] Read more about neuropathy and diabetic ulcers under the “Common Types of Wounds” subsection. Nurses provide vital patient education to patients with diabetes to effectively manage the disease process for improved wound healing.

- Age. Older adults have an altered inflammatory response that can impair wound healing. Nurses can educate patients about the importance of exercise for improved wound healing in older adults.[54]

- Obesity. Obese individuals frequently have wound complications, including infection, dehiscence, hematoma formation, pressure injuries, and venous injuries. Nurses can educate patients about healthy lifestyle choices to reduce obesity in patients with chronic wounds.[55]

- Medications. Medications such as corticosteroids impair wound healing due to reduced formation of granulation tissue.[56] When assessing a chronic wound that is not healing as expected, it is important to consider the side effects of the patient’s medications.

- Alcohol consumption. Research shows that exposure to alcohol impairs wound healing and increases the incidence of infection.[57] Patients with impaired healing of chronic wounds should be educated to avoid alcohol consumption.

- Smoking. Smoking impacts the inflammatory phase of the wound healing process, resulting in poor wound healing and an increased risk of infection.[58] Patients who smoke should be encouraged to stop smoking.

Lab Values Affecting Wound Healing

When a chronic wound is not healing as expected, laboratory test results may provide additional clues regarding the causes of the delayed healing. See Table 20.2 for lab results that offer clues to systemic issues causing delayed wound healing.[59]

Table 20.2 Lab Values Associated with Delayed Wound Healing[60]

| Abnormal Lab Value | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Low hemoglobin | Low hemoglobin indicates less oxygen is transported to the wound site. |

| Elevated white blood cells (WBC) | Increased WBC indicates infection is occurring. |

| Low platelets | Platelets are important during the proliferative phase in the creation of granulation tissue and angiogenesis.[61] |

| Low albumin | Low albumin indicates decreased protein levels. Protein is required for effective wound healing. |

| Elevated blood glucose or hemoglobin A1C | Elevated blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C levels indicate poor management of diabetes mellitus, a disease that impacts wound healing. |

| Elevated serum BUN and creatinine | BUN and creatinine levels are indicators of kidney function, with elevated levels indicating worsening kidney function. Elevated BUN (blood urea nitrogen) levels impact wound healing. |

| Positive wound culture | Positive wound cultures indicate an infection is present and provide additional information, including the type and number of bacteria present, as well as identifying antibiotics to which the bacteria is susceptible. The nurse reviews this information when administering antibiotics to ensure the prescribed therapy is effective for the type of bacteria present. |

Wound Complications

In addition to delayed wound healing, several other complications can occur. Three common complications are the development of a hematoma, infection, or dehiscence. These complications should be immediately reported to the health care provider.

Hematoma

A hematoma is an area of blood that collects outside of the larger blood vessels. A hematoma is more severe than ecchymosis (bruising) that occurs when small veins and capillaries under the skin break. The development of a hematoma at a surgical site can lead to infection and incisional dehiscence.[62] See Figure 20.14[63] for an image of a hematoma.

Infection

A break in the skin allows bacteria to enter and begin to multiply. Microbial contamination of wounds can progress from localized infection to systemic infection, sepsis, and subsequent life- and limb-threatening infection. Signs of a localized wound infection include redness, warmth, and tenderness around the wound. Purulent or malodorous drainage may also be present. Signs that a systemic infection is developing and requires urgent medical management include the following[64]:

- Fever over 101 F (38 C)

- Overall malaise (lack of energy and not feeling well)

- Change in level of consciousness/increased confusion

- Increasing or continual pain in the wound

- Expanding redness or swelling around the wound

- Loss of movement or function of the wounded area

Dehiscence

Dehiscence refers to the separation of the edges of a surgical wound. A dehisced wound can appear fully open where the tissue underneath is visible, or it can be partial where just a portion of the wound has torn open. Wound dehiscence is always a risk in a surgical wound, but the risk increases if the patient is obese, smokes, or has other health conditions, such as diabetes, that impact wound healing. Additionally, the location of the wound and the amount of physical activity in that area also increase the chances of wound dehiscence.[65] See Figure 20.15[66] for an image of dehiscence in an abdominal surgical wound in a 50-year-old obese female with a history of smoking and malnutrition.

Wound dehiscence can occur suddenly, especially in abdominal wounds when the patient is coughing or straining. Evisceration is a rare but severe surgical complication when dehiscence occurs, and the abdominal organs protrude out of the incision. Signs of impending dehiscence include redness around the wound margins and increasing drainage from the incision. The wound will also likely become increasingly painful. Suture breakage can be a sign that the wound has minor dehiscence or is about to dehisce.[67]

To prevent wound dehiscence, surgical patients must follow all post-op instructions carefully. The patient must move carefully and protect the skin from being pulled around the wound site. They should also avoid tensing the muscles surrounding the wound and avoid heavy lifting as advised.[68]

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Foley Catheter Insertion (Male).”

See Figure 21.20[69] for an image of a Foley catheter kit.

View an instructor demonstration of Male Foley Catheter Insertion[70]:

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: peri-care supplies, clean nonsterile gloves, Foley catheter kit, extra pair of sterile gloves, VelcroTM catheter securement device to secure Foley catheter to leg, wastebasket, and light source (i.e., goose neck lamp or flashlight).

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Assess for latex/iodine allergies, enlarged prostate, joint limitations for positioning, and any history of previous issues with catheterization.

- Prepare the area for the procedure:

- Place hand sanitizer for use during/after procedure on the table near the bed.

- Place the catheter kit and peri-care supplies on the over-the-bed table.

- Secure the wastebasket near the bed for disposal.

- Ensure adequate lighting. Enlist assistance for positioning if needed.

- Raise the opposite side rail. Set the bed to a comfortable height.

- Position the male patient supine with legs extended. Uncover the patient, exposing the patient’s groin, legs, and feet for positioning and sterile field.

- Apply clean nonsterile gloves and perform peri-care.

- Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Open the outer package wrapping. Remove the sterile wrapped box with the paper label facing upward to avoid spilling contents and place it on the bedside table or, if possible, between the patient’s legs. Place the plastic package wrapping at the end of the bed or on the side of the bed near you, with the opening facing you or facing upwards for waste.

- Open the kit to create and position a sterile field (if on bedside table):

- Open first flap away from you.

- Open second flap toward you.

- Open side flaps.

- Only touch the outer 1” edge of the field to position the sterile field on the table.

- Carefully remove the sterile drape from the kit. Touching only the outermost edges of the drape, unfold and place the touched side of the drape closest to linen, under the patient. Vertically position the drape between the patient’s legs to allow space for the sterile box and sterile tray. Do not reach over the drape as it is placed.

- Wash your hands and apply sterile gloves.

- OPTIONAL: Place the fenestrated drape over the patient’s perineal area with gloves on inside of the drape, away from the patient's gown, with peri-area visible through the opening. Maintain sterility.

- Empty the syringe or package of lubricant into the plastic tray. Place the empty syringe/package on the sterile outer package.

- Simulate application (do not open) of the iodine cleanser to the cotton. Place package on sterile outer package.

- Remove the sterile urine specimen container and cap and set them aside.

- Remove the tray from the top of the box and place on sterile drape.

- Carefully remove the plastic catheter covering, while keeping the catheter in the container. Attach the syringe filled with sterile water to the balloon port of the catheter; keep the catheter sterile.

- Lubricate the tip of the catheter by dipping it in lubricant and replace it in the box. Maintain sterility.

- If preparing the kit on a bedside table, place the plastic tray on top of the sterile box and carry it as one unit to the sterile drape between the patient’s legs, taking care not to touch your gloves on the patient's legs or bed linens.

- Place the top plastic tray on the sterile drape nearest to the patient.

- Tell the patient that you are going to clean the catheterization area and they will feel a cold sensation.

- With your nondominant hand, grasp the penis and retract the foreskin if present; position at a 90-degree angle. Your nondominant hand will now be nonsterile. This hand must remain in place throughout the procedure.

- With your sterile dominant hand, use the forceps to pick up a cotton ball. Cleanse the glans penis with a saturated cotton ball in a circular motion from the center of the meatus outward. Discard the cotton ball after use into the plastic outer wrap, not crossing the sterile field. Repeat for a total of three times using a new cotton ball each time. Discard the forceps in the plastic bag without touching your sterile gloved hand to the bag.

- Pick up the catheter with your sterile dominant hand. Instruct the patient to take a deep breath and exhale or “bear down” as if to void, as you steadily insert the catheter, maintaining sterility of the catheter, until urine is noted in the tube.

- Once urine is noted, continue inserting to the catheter bifurcation.

- With your nondominant/nonsterile hand, continue to hold the penis, and use your thumb and index finger to stabilize the catheter. With the dominant hand, inflate the retention balloon with the water-filled syringe to the level indicated on the balloon port of the catheter. With the plunger still pressed, remove the syringe and set it aside. Pull back on the catheter slightly until resistance is met, confirming the balloon is in place. Replace the foreskin, if retracted, for the procedure.

If the patient experiences pain during balloon inflation, deflate the balloon and insert the catheter farther into the bladder. If pain continues with the balloon inflation, remove the catheter and notify the patient’s provider.

If the patient experiences pain during balloon inflation, deflate the balloon and insert the catheter farther into the bladder. If pain continues with the balloon inflation, remove the catheter and notify the patient’s provider. - Remove the sterile draping and supplies from the bed area and place them on the bedside table. Remove the bath blanket and reposition the patient.

- Remove your gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Apply new gloves. Secure the catheter with the securement device, allowing room to not pull on the catheter.

- Place the drainage bag below the level of the bladder and attach the bag to the bed frame.

- Perform peri-care as needed.

- Dispose of waste and used supplies.

- Remove your gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Obtaining a Urine Specimen from a Foley Catheter.”

View an instructor demonstration of Obtaining a Urine Specimen from a Foley Catheter[71]:

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: peri-care supplies, nonsterile gloves, Luer-lock syringe (or other syringe specified within collection kit) for sterile specimen, alcohol wipes/scrub hubs, two preprinted patient labels, clear biohazard bag for lab sample, and urinary graduated cylinder.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Verify the order and assemble the supplies on a protective drape on the table: gloves, Luer-lock syringe, alcohol swabs, sterile container, two preprinted patient labels, and clear lab specimen biohazard bag for transport to lab.

- Perform hand hygiene and put on nonsterile gloves.

- Check for urine in the tubing and position the tubing on the bed.

- If additional urine is needed, clamp the tubing below the port for 10-15 minutes or until urine appears.

- Clean the sample port of the catheter with an alcohol swab.

- Attach the Luer-lock syringe to the sample port of the catheter and withdraw 10-30 mL of urine; remove the syringe and unclamp the tubing.

- Open the lid of the sterile container, inverting the lid on the drape and maintaining sterility. Transfer the urine to the sterile container, preventing touching the syringe to the container. Place the syringe on the drape, close the lid tightly, and clean the outside of the container with germicidal wipes.

- Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Add information to the preprinted label: date, time collected, and your initials. Apply gloves. Place the label on the specimen container and put the container inside the biohazard bag. Remove gloves and wash your hands. Place the second label outside of the bag. Transport to the lab immediately.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Exchange of information using words understood by the receiver.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of an “Ostomy Appliance Change."

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: washcloth and warm water, stoma products/appliances per order/patient preference (wafer, bag, clip), gauze, pads, sizing measures, scissors, pen, nonsterile gloves, skin prep or other skin products per patient preference, and wastebasket.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Set the bed to a comfortable height; raise the opposite side rail.

- Ask the patient about preferences, usual practices, care, and maintenance at home.

- Apply nonsterile gloves.

- Position the patient according to patient status:

- Assist the patient to the bathroom and have them sit on the toilet to be near the sink for ease of process.

- If in bed, uncover the patient, exposing only the abdomen. Apply drape/chux under the patient or ostomy pouch. Place the wastebasket near the bed.

- Empty the pouch depending on the type of the appliance and the location type of procedure:

- Remove the pouch and empty it into the toilet.

- Set pouch aside in the basin or receptacle if at bedside.

- Assess ostomy bag contents and remove current ostomy appliance (keep clamp if present).

- Remove adhesive residue from the skin with adhesive remover wipes.

- Cleanse the stoma and surrounding skin with gauze and room temperature tap water; pat dry the skin.

- Assess the condition of the stoma and peristomal skin.

- Place new gauze pad over the stoma while you are preparing the new wafer and pouch.

- Trace the pattern onto the paper backing of the wafer and cut the wafer. (If a pattern is available, cut the new wafer prior to removing the pouch). No more than 1/8th inch (2 mm) of skin around the stoma should be exposed for correct fit.

- Apply skin prep and wait until tacky (optional).

- Remove the gauze pad from the orifice of the stoma.

- Remove the paper backing from the wafer and place it on the skin with the stoma centered in the cutout opening of the wafer; press gently on the wafer to remove air/seal to the skin.

- Apply pouch to wafer with clamp on pouch and opening in downward position.

- Attach and close the pouch clamp.

- Dispose of used supplies and wrappings.

- Remove your gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.