9.9 Cerebrovascular Accident

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

A cerebrovascular accident (CVA), commonly referred to as a stroke, is a sudden interruption of blood flow to the brain that requires immediate emergency care. A spectrum of neurological deficits and potential complications can occur as a result of a CVA. Each year in the United States, there are more than 800,000 strokes. Stroke is a leading cause of death or serious long-term disability. Nearly three quarters of all strokes occur in people over the age of 65.

Diagnosing and treating a stroke is often referred to as “time is brain.” With timely treatment, it is possible to save brain cells and greatly reduce the damage or death that can occur due to a stroke. Brain cells die because they stop getting the oxygen and nutrients needed to function, or they are damaged by sudden bleeding in or around the brain. Knowing the signs of stroke and calling 911 immediately can help save someone’s life.[1]

Pathophysiology

There are two types of strokes called ischemic and hemorrhagic. An acute ischemic stroke is caused by a blockage or occlusion of a cerebral or carotid artery. This can be caused by plaque that has built up within the vessel, resulting in a thrombus or a blood clot that has traveled from another area of the body and lodged in the blood vessel, referred to as an embolism. An ischemic stroke is further categorized depending on the cause. CVAs caused by a thrombus are referred to as a thrombotic stroke, and CVAs caused by an embolism are called an embolic stroke. Thrombotic strokes account for more than half of all strokes and commonly occur because of atherosclerosis. An embolic stroke is caused by a thrombus or a group of thrombi that break away from one area of the body and travel through the arterial system via the carotid artery or through the arteries at the base of the skull. The most common source of the emboli is the heart. For example, emboli occur frequently in clients with atrial fibrillation, where tiny clots form within the atria of the heart and then break away and move into the brain’s circulation.

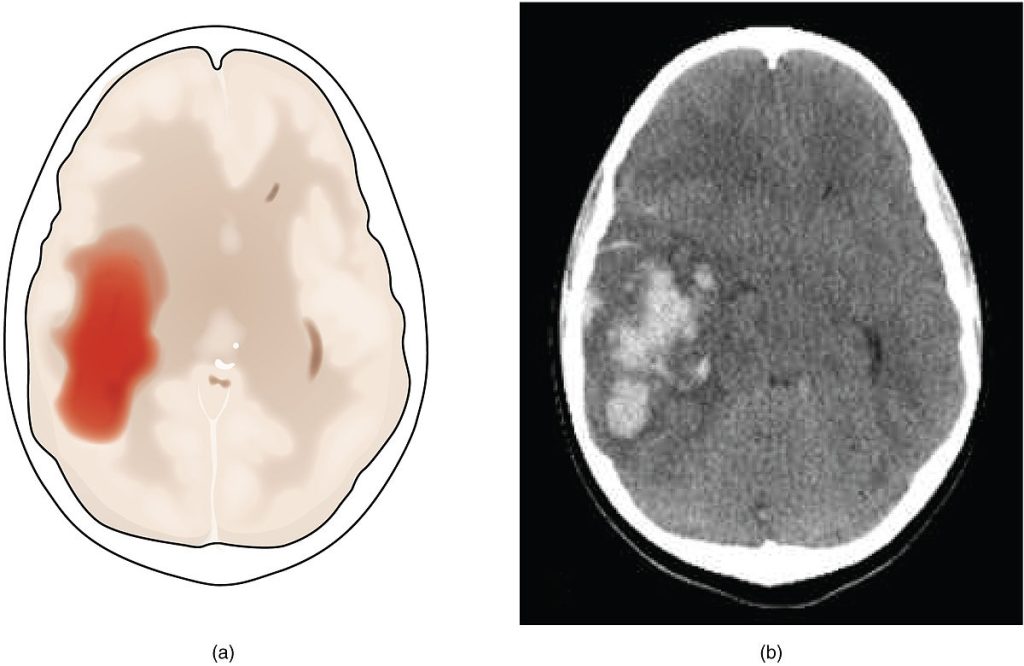

The second type of CVA is a hemorrhagic stroke. With this type of stroke, the stability of a blood vessel in the brain is compromised, leading to rupture and bleeding. The blood accumulates into the brain tissue or subarachnoid space. As the blood presses against the tissue in the brain, it can increase intracranial pressure.[2]

Several factors can lead to a hemorrhagic stroke. Sustained elevated blood pressure can cause changes within the arterial wall, making it susceptible to rupture. If this occurs it can cause an intracerebral hemorrhage, leading to bleeding, which causes edema irritation and displacement of the brain tissue. A subarachnoid hemorrhage is more common and refers to bleeding in the space between the brain and the surrounding membrane (subarachnoid space). This bleeding is usually triggered by a ruptured aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation. An aneurysm is an abnormal bulging or ballooning that develops in a weak spot of the arterial wall, which may become so thin that it ruptures. The primary symptom is a sudden, severe headache, often described by clients as the worst headache they have ever felt.[3]

An arteriovenous malformation is a tangle of blood vessels that irregularly connects arteries and veins that can rupture, causing bleeding in the brain and spinal cord. See Figure 9.23[4] for an illustration comparing ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes and Figure 9.24[5] for an image containing a radiographic image of a hemorrhagic stroke.

![]“Types_of_Stroke.jpg” by https://www.scientificanimations.com/ is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 Image showing a Comparison of Ischemia and Hemorrhagic Strokes on two simulated patient brains](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/32/2024/03/1200px-Types_of_Stroke-1024x576.jpg)

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are temporary periods of symptoms similar to a stroke, but irreversible damage to the brain cells do not occur. However, TIAs are considered warning signs of an impending stroke. With prompt diagnosis and treatment of TIAs, a CVA can be prevented.[6]

See Table 9.9 for a comparison of types of CVAs.

Table 9.9. Comparison of Types of CVAs

| Clinical Presentation | Ischemic – Thrombolic | Ischemic – Embolic | Hemorrhagic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progression | Symptoms follow a sequential manner or intermittently fluctuate between improvement and worsening | Abrupt development with steady progression | Abrupt development |

| Onset | Gradual within minutes to hours | Sudden | Typically sudden, but may be gradual if the cause is hypertension |

| Level of consciousness | Awake | Awake | Lethargic or comatose |

| Contributing or associated factors | Hypertension and atherosclerosis | Cardiac disease and atrial fibrillation | Hypertension, vessel disorders, or genetic factors |

| Preceding symptoms | TIA | TIA | Headache |

| Neurologic deficits | Deficits become apparent during the first few weeks, such as speech deficits, visual problems, and confusion | Most severe deficits are at onset, such as paralysis and expressive aphasia | Regional deficits may be severe |

| Duration | Improvements may occur over weeks to months, but permanent deficits are probable | Improvements may occur rapidly if the embolus is effectively treated | Duration is variable with possible permanent deficits |

Assessment

If an evolving CVA is suspected, a rapid assessment is performed with rapid transport to a stroke center designated by The Joint Commission or other accredited organization for rapid treatment. If a client is already hospitalized for another medical condition, many hospitals have designated stroke teams and protocols that are immediately implemented.

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a standardized tool that is commonly used to assess clients suspected of experiencing an acute cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke).[7] It is also used to quantify the severity of a stroke by assigning numbers to the symptoms, with higher numbers indicating more dysfunction. The three most predictive findings that occur during an acute stroke are facial drooping, arm drift/weakness, and abnormal speech. Use the box below to view the NIH stroke scale.

View the NIH Stroke Scale at the National Institutes of Health.

View a supplementary YouTube video[8] about how to use the NIH Stroke Scale: Dr Hartmut Gross Teaches the NIH Stroke Scale.

A commonly used mnemonic regarding assessment of individuals suspected of experiencing a stroke is “BEFAST.” BEFAST stands for Balance, Eyes, Face, Arm, Speech, and Time.

- B: Does the person have a sudden loss of balance?

- E: Has the person lost vision in one or both eyes?

- F: Does the person’s face look uneven?

- A: Is one arm weak or numb?

- S: Is the person’s speech slurred? Are they having trouble speaking or seem confused?

- T: Time to call for assistance immediately

Clients experiencing a hemorrhagic CVA often report “having the worst headache of my life” with sudden onset and no known cause. Other signs of hemorrhage may include nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and a stiff neck. Other common stroke symptoms are as follows:

- Sudden numbness or weakness of an arm or leg, especially on one side of the body

- Sudden confusion, trouble speaking, or understanding

- Sudden loss of vision or trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, or loss of balance or coordination

During the initial client presentation, nurses observe the client’s level of consciousness (LOC) and administer the Glasgow Coma Scale. Review information about the Glasgow Coma Scale in the “General Assessment of the Nervous System” section.

Depending on the extent and location of the CVA, specific chronic signs and symptoms may occur. For instance, if a CVA occurs in the right cerebral hemisphere, visual and spatial awareness are affected, as well as possible personality changes, impulsivity, and poor judgment. Clients with left hemisphere involvement may have problems with speech, language, and analytic thinking. See the following box for other complications that can occur as a result of a CVA.

Potential Complications of a CVA

- Hemiparesis (one-sided weakness)

- Hemiplegia (one-sided paralysis)

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Paresthesias (sensory perception deficits such as numbness, tingling, unusual sensations)

- Ptosis (eye drooping)

- Nystagmus (eyes make repetitive, uncontrolled movements)

- Dysarthria (difficulty speaking because the muscles used for speech are weak)

- Aphasia (loss of ability to understand or express speech)

- Homonymous hemianopsia (loss of half of one’s visual field)

- Apraxia (inability to perform tasks or movements when asked, even though the request or command is understood)

- Agnosis (loss of the ability to understand meaning of stimuli)

- Visual and spatial deficits

- Amnesia (memory loss)

- Bladder incontinence

- Personality and behavior changes

- Vertigo (dizziness described as a sensation of motion or spinning)

- Confusion

- Coma

In terms of psychosocial assessment findings, client reactions may vary based on the type and location of the stroke. Assess for emotional lability (uncontrollable emotions), especially if the right side or frontal lobe of the brain has been affected. Sometimes, the client may laugh or cry unexpectedly or inappropriately in a manner they are unable to control.

View a supplementary YouTube video[9] on stroke: Stroke: It happens in an instant.

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

A CT scan without contrast is typically the first diagnostic test performed for clients with a suspected CVA to determine if a hemorrhagic stroke is occurring.[10] If a hemorrhagic stroke is ruled out with a CT scan, tests are performed to identify potential causes of an ischemic stroke. For example, a carotid duplex/doppler ultrasound may be performed on the carotid arteries to assess for occlusion. A cardiac echocardiogram may be performed to assess for clots caused by atrial fibrillation. An MRI may be performed to assess for brain lesions. A cerebral angiogram may be performed to determine the blockage site.[11]

Blood tests such as prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) are performed to provide baseline information if fibrinolytic or anticoagulation therapy for an ischemic stroke is initiated. Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Nursing Diagnoses

Depending on the severity of the stroke and the reason for immediate treatment, airway, breathing, and circulation take priority. Common nursing diagnoses include the following[12]:

- Risk for Inadequate Cerebral Tissue Perfusion

- Decreased Physical Mobility

- Impaired Verbal Communication

- Impaired Swallowing

- Unilateral Neglect

- Ineffective Coping

- Feeding, Bathing, or Dressing Self-care Deficit

Outcome Identification

After a client experiences a CVA, rehabilitation continues throughout the convalescent period, relying on a collaborative effort of a multidisciplinary team including nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists, as well as case managers. Overall goals include the following:

- Improved mobility

- Achievement or improvement in self-care

- Relief of sensory and perceptual deprivation

- Prevention of aspiration

- Bowel and bladder continence

- Improved thought processes

- Optimization of communication

- Maintenance of skin integrity

- Absence of complications or injury

Sample outcome criteria include the following:

- The client will maintain intact skin integrity during hospitalization despite impaired mobility.

- The client will not aspirate food, fluids, or medications during hospitalization.

- The client will not fall during hospitalization.

- The client will demonstrate accurate use of assistive devices after the teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Hemorrhagic Stroke

The most common cause of hemorrhagic stroke is hypertension. Blood pressure is reduced gradually to 150/90 mmHg using a beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor, calcium channel blocker, or hydralazine. The role of surgery in hemorrhagic stroke is a controversial topic. Current research indicates emergency surgery for cerebellar hemorrhage greater than 3 cm in diameter, hydrocephalus (fluid accumulation in the brain), or brain stem compression. Minimally invasive procedures are also being investigated.[13]

Ischemic Stroke

Medical treatments for clients with acute ischemic stroke include IV fibrinolytic therapy and endovascular interventions.

Medication Therapy

IV fibrinolytic therapy, also known as “clot-buster medication,” is administered for specific clients experiencing an ischemic stroke who meet selective criteria. It is standard of practice to improve blood flow to the viable brain tissue around the infarction. IV alteplase is the only FDA-approved medication for acute ischemic stroke. Treatment is dependent on the timing of symptom onset and treatment initiation. The FDA recommends administration of IV alteplase within three hours of stroke onset and up to 4.5 hours in some cases. However, alteplase is not administered for clients with the following contraindications[14]:

- Age over 80 years

- Use of anticoagulants

- History of stroke and diabetes

Ongoing drug therapy depends on the type and severity of the stroke and the neurologic dysfunction. The general purpose of ongoing drug therapy is to prevent further thrombotic or embolic episodes by prescribing antithrombotics and anticoagulants and to protect the neurons from hypoxia. An initial low dose of aspirin is recommended 24 to 48 hours after the onset of stroke, but it should not be administered within 24 hours after alteplase. A calcium channel blocker such as nimodipine may be prescribed to treat vertebral vasospasm after a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stool softeners, antianxiety medications, and analgesics may also be prescribed for symptom management. Blood pressure medications may also be prescribed to treat underlying hypertension.

Surgical Management

Endovascular procedures may be performed for clients experiencing an ischemic stroke. The procedure improves perfusion by surgically removing the thrombus from the affected artery.

If a client is experiencing a hemorrhagic stroke caused by a cerebral aneurysm or an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), a procedure is performed by a neurosurgeon to stop the bleeding. Clients experiencing a hemorrhagic stroke are at risk for developing increased intracranial pressure (ICP) within the first 72 hours after onset due to edema within the brain.

See the following box for signs and symptoms of increased ICP.

Manifestations of Increased Intracranial Pressure[15]

- Earliest sign of increased ICP is decreased level of consciousness

- Restlessness, agitation, confusion

- Headache

- Aphasia

- Change in speech pattern

- Nausea and vomiting

- Seizures (most likely in the first 24 hours post-stroke)

- Severe hypertension

- Bradycardia

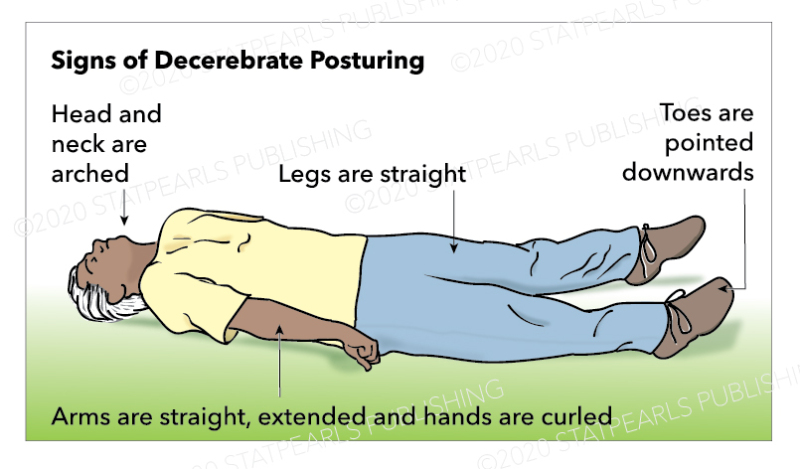

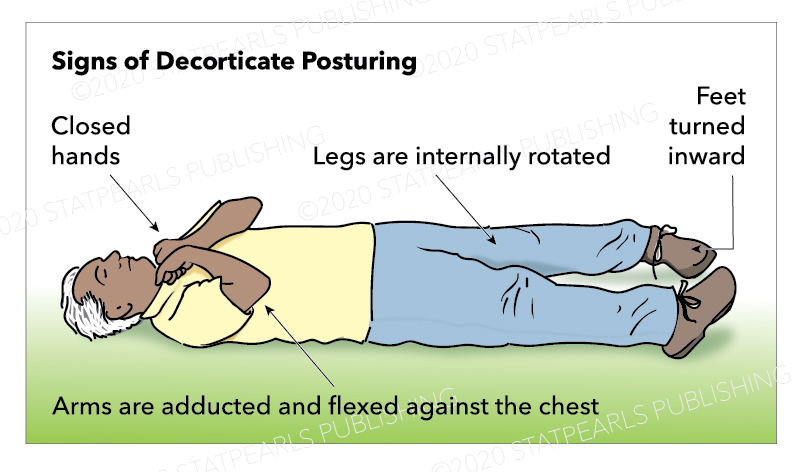

- Abnormal posturing (late signs of severe brain damage):

Nursing Interventions

During the acute treatment of a stroke, nursing interventions focus on maintaining physiological integrity and reducing the risk of complications. Nursing interventions during the acute phase of a stroke are provided in the following box.

Nursing Interventions During Acute Treatment of a Stroke[18]

- Assessments

- Assess mental status, level of consciousness, and focused neurological assessments, including the Glasgow Coma Scale and pupil evaluation. Assess higher cognitive functions like speech, memory, and cognition.

- Monitor airway patency, breathing pattern and respiratory status.

- Frequently monitor vital signs.

- Monitor for seizure activity.

- Monitor cardiac rhythm.

- Assess and monitor the ability to swallow.

- Monitor the ability to void and for urine retention.

- Assess and compare bilateral muscle strength and mobility.

- Monitor electrolytes (sodium) and intake/output for signs of SIADH.

- Interventions

- Provide a quiet environment with the head of the bed elevated 30 degrees.

- Elevate bed rails to prevent falls.

- Ensure call light is within reach or use a soft touch call assistive device.

- Prevent constipation and straining with administration of stool softeners.

- Follow deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis protocol.

- Implement aspiration precautions for dysphagia as indicated (HOB 45 degrees or higher, supervise eating, reduce distractions, and collaborate with speech therapy).

- Reposition frequently to maintain circulation and prevent skin breakdown.

- Prevent injury by not lifting the client using a flaccid or affected arm.

- Provide range-of-motion exercises.

- Elevate affected arm or extremity to prevent dependent edema.

- Administer analgesics as prescribed.

- Approach client with a decreased field of vision on their side where visual perception is intact; place all visual stimuli on this side. Teach client to turn and look in the direction of the defective visual field to compensate for the loss; make eye contact with the client and draw attention to the affected side.

- If client received TPA or is on anticoagulants to prevent additional CVA, implement bleeding precautions.

- Collaborate with PT/OT/ST to optimize functioning.

If a client is experiencing increased ICP following a hemorrhagic stroke, nurses implement interventions to manage ICP. See related nursing interventions in the following box.

Interventions Associated With Managing ICP[19]

- Elevate the head of the bed to greater than 30 degrees or as determined by the health care provider and agency policy.

- Provide oxygen therapy to prevent hypoxia.

- Avoid sudden neck or hip flexion during repositioning because this can increase intrathoracic pressure, causing increased ICP.

- Keep the neck midline to facilitate venous drainage from the head.

- Avoid clustering nursing activities such as bathing, suctioning, or treatments. Multiple clustered activities can drastically raise ICP.

- Maintain a quiet, low stimulus environment.

- Closely monitor blood pressure, heart rhythm, oxygenation, blood glucose, and body temperature.

- Hyperoxygenate before and after suctioning if appropriate. (Hypercarbia can increase cerebral blood flow, contributing to increased ICP.)

- If sedatives are administered, they should be done so cautiously because they can mask neurological symptoms.

Health Teaching and Promotion

Following care of an acute stroke, health teaching focuses on reducing modifiable risk factors for another stroke and improving long-term functioning. Prevention strategies include quitting smoking, controlling blood pressure, managing glucose levels within the healthy range, making healthy diet choices, reducing hyperlipidemia, increasing physical activity, and adhering to prescribed medication therapy.

In addition to teaching about modifiable risk factors, clients should also receive health teaching about the following topics:

- Teaching the causes of strokes

- Ensuring clients and caregivers understand the signs and symptoms of stroke to ensure timely evaluation in the event of a recurrent stroke

- Ensuring clients and caregivers understand potential complications of therapy, especially bleeding, if they are discharged on an anticoagulant

- Using assistive devices, as advised by the therapy teams, to prevent the risk of falls

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with a family member or other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Cerebrovascular Accident

RN Recap: Cerebrovascular Accident

View a brief YouTube video overview on cerebrovascular accident[20]:

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2023, November 28). Stroke. National Institutes of Health. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/stroke ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2023, November 28). Stroke. National Institutes of Health. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/stroke ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, August 31). Subarachnoid hemorrhage. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/subarachnoid-hemorrhage/symptoms-causes/syc-20361009 ↵

- “Types_of_Stroke.jpg” by https://www.scientificanimations.com/ is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “1602_The_Hemorrhagic_Stroke-02.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, March 26). Transient ischemic attack. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/transient-ischemic-attack/symptoms-causes/syc-20355679 ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). NIH stroke scale. https://www.stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm ↵

- Larry B. Mellick, MD. (2015, April 22). Dr Hartmut Gross teaches the NIH stroke scale [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jRRzjygCjBE ↵

- National Stroke Association. (2018, April 23). Stroke: It happens in an instant [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/5OF9qVxx9mo?t=13 ↵

- Stroke Imaging by Shafaat & Sotoudeh is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Acute Stroke (Nursing) by Tadi, Lui, & Budd is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Hemorrhagic Stroke by Unnithan, Das, & Mehta is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Acute Stroke (Nursing) by Tadi, Lui, & Budd is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Peters, R. (2006). Ageing and the brain. Postgraduate Medical Journal 82(964), 84-8. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/pgmj.2005.036665 ↵

- “Decerebrate Posturing” by Katherine Humphries is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559135/. ↵

- “Decorticate Posturing” by Katherine Humphries is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559135/. ↵

- Acute Stroke (Nursing) by Tadi, Lui, & Budd is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Increased Intracranial Pressure by Pinto, Tadi, & Adeyinka is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, April 24).Health Alterations - Chapter 9 Nervous System - Cerebrovascular accident / Stroke [Video]. YouTube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8WUnKbgQOU ↵

An exaggerated inflammatory response to a noxious stressor (including, but not limited to, infection and acute inflammation) that affects the entire body.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Wound Assessment.”

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: gloves, wound measuring tool, and sterile cotton-tipped swab.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Identify wound location. Document the anatomical position of the wound on the body using accurate anatomical terminology.

- Identify the type and cause of the wound (e.g., surgical incision, pressure injury, venous ulcer, arterial ulcer, diabetic ulcers, or traumatic wound).

- Note tissue damage:

- If the wound is a pressure injury, identify the stage and use the Braden Scale to assess risk factors.

- Observe wound base. Describe the type of tissue in the wound base (i.e., granulation, slough, eschar).

- Follow agency policy to measure wound dimensions, including width, depth, and length. Assess for tunneling, undermining, or induration.

- Describe the amount and color of wound exudate:

- Serous drainage (plasma): clear or light yellowish

- Sanguineous drainage (fresh bleeding): bright red

- Serosanguineous drainage (a mix of blood and serous fluid): pink

- Purulent drainage (infected): thick, opaque, and yellow, green, or other color

- Note the presence or absence of odor, noting the presence of odor may indicate infection.

- Assess the temperature, color, and integrity of the skin surrounding the wound. Assess for tenderness of periwound area.

- Assess wound pain using PQRSTU. Note the need to premedicate before dressing changes if the wound is painful. (Read more about PQRSTU assessment in the "Health History" chapter.)

- Assess for signs of infection, such as fever, change in level of consciousness, type of drainage, presence of odor, dark red granulation tissue, or redness, warmth, and tenderness of the periwound area.

- Assist the patient back to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the assessment findings and report any concerns according to agency policy.

View a supplementary YouTube video of a nurse performing a wound assessment in Wound Care: Assessing Wounds.[1]

Use this checklist to review the steps for completion of “Simple Dressing Change.”

View an instructor demonstration of Wound Care[2]:

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: nonsterile gloves, sterile gloves per agency policy, wound cleansing solution or sterile saline, sterile 2"x 2" gauze for wound cleansing, 4" x 4" sterile gauze for wound dressing, scissors, and tape (if needed).

- Use the smallest size of dressing for the wound.

- Take only the dressing supplies needed for the dressing change to the bedside.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Assess wound pain using PQRSTU.

- Prepare the environment, position the patient, adjust the height of the bed, and turn on the lights. Ensure proper lighting to allow for good visibility to assess the wound. Ensure proper body mechanics for yourself and create a comfortable position for the patient. Premedicate, if indicated, to ensure patient’s comfort prior to and during the procedure.

- Perform hand hygiene immediately prior to arranging the supplies at the bedside.

- Place a clean, dry, barrier on the bedside table. Create a sterile field if indicated by agency policy.

- Pour sterile normal saline into opened sterile gauze packaging to moisten the gauze.

- Normal saline containers must be used for only one patient and must be dated and discarded within at least 24 hours of being opened.

- Commercial wound cleanser may also be used.

- Expose the dressing.

- Perform hand hygiene and apply nonsterile gloves.

- Remove the outer dressing.

- Remove the inner dressing. Use transfer forceps, if necessary, to avoid contaminating the wound bed.

- Remove gloves, perform hand hygiene, and put on new gloves.

- Wrap the old inner dressing inside the glove as you remove it, if feasible, to prevent contaminating the environment.

- Assess the wound:

- See “Checklist for Wound Assessment” checklist for details.

- Drape the patient with a water-resistant underpad, if indicated, to protect the patient's clothing and linen.

- Apply gloves and other PPE as indicated. Goggles, face shield, and/or mask may be indicated.

- Cleanse the wound based on agency policy, using moistened gauze, commercial cleanser, or sterile irrigant. When using moistened gauze, use one moistened 2" x 2" sterile gauze per stroke. Work in straight lines, moving away from the wound with each stroke. Strokes should move from a clean area to a dirty area and from top to bottom.

- Note: A suture line is considered the “least contaminated” area and should be cleansed first.

- Cleanse around the drain (if present):

- Clean around the drain site using a circular stroke, starting with the area immediately next to the drain.

- Using a new swab with each stroke, cleanse immediately next to the drain in a circular motion. With the next stroke, move a little farther out from the drain. Continue this process with subsequent circular swabs until the skin surrounding the drain is cleaned.

- Remove gloves, perform hand hygiene, and apply new gloves.

- Apply sterile dressing (4" x 4" sterile gauze) using nontouch technique so that the dressing touching the wound remains sterile.

- Apply outer dressing if required. Secure the dressing with tape as needed.

- Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Compare the wound assessment to previous documentation and analyze healing progress. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Use this checklist to review the steps for completion of “Simple Dressing Change.”

View an instructor demonstration of Wound Care[3]:

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: nonsterile gloves, sterile gloves per agency policy, wound cleansing solution or sterile saline, sterile 2"x 2" gauze for wound cleansing, 4" x 4" sterile gauze for wound dressing, scissors, and tape (if needed).

- Use the smallest size of dressing for the wound.

- Take only the dressing supplies needed for the dressing change to the bedside.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Assess wound pain using PQRSTU.

- Prepare the environment, position the patient, adjust the height of the bed, and turn on the lights. Ensure proper lighting to allow for good visibility to assess the wound. Ensure proper body mechanics for yourself and create a comfortable position for the patient. Premedicate, if indicated, to ensure patient’s comfort prior to and during the procedure.

- Perform hand hygiene immediately prior to arranging the supplies at the bedside.

- Place a clean, dry, barrier on the bedside table. Create a sterile field if indicated by agency policy.

- Pour sterile normal saline into opened sterile gauze packaging to moisten the gauze.

- Normal saline containers must be used for only one patient and must be dated and discarded within at least 24 hours of being opened.

- Commercial wound cleanser may also be used.

- Expose the dressing.

- Perform hand hygiene and apply nonsterile gloves.

- Remove the outer dressing.

- Remove the inner dressing. Use transfer forceps, if necessary, to avoid contaminating the wound bed.

- Remove gloves, perform hand hygiene, and put on new gloves.

- Wrap the old inner dressing inside the glove as you remove it, if feasible, to prevent contaminating the environment.

- Assess the wound:

- See “Checklist for Wound Assessment” checklist for details.

- Drape the patient with a water-resistant underpad, if indicated, to protect the patient's clothing and linen.

- Apply gloves and other PPE as indicated. Goggles, face shield, and/or mask may be indicated.

- Cleanse the wound based on agency policy, using moistened gauze, commercial cleanser, or sterile irrigant. When using moistened gauze, use one moistened 2" x 2" sterile gauze per stroke. Work in straight lines, moving away from the wound with each stroke. Strokes should move from a clean area to a dirty area and from top to bottom.

- Note: A suture line is considered the “least contaminated” area and should be cleansed first.

- Cleanse around the drain (if present):

- Clean around the drain site using a circular stroke, starting with the area immediately next to the drain.

- Using a new swab with each stroke, cleanse immediately next to the drain in a circular motion. With the next stroke, move a little farther out from the drain. Continue this process with subsequent circular swabs until the skin surrounding the drain is cleaned.

- Remove gloves, perform hand hygiene, and apply new gloves.

- Apply sterile dressing (4" x 4" sterile gauze) using nontouch technique so that the dressing touching the wound remains sterile.

- Apply outer dressing if required. Secure the dressing with tape as needed.

- Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Compare the wound assessment to previous documentation and analyze healing progress. Report any concerns according to agency policy.