6.3 General Respiratory System Assessment and Interventions

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

When assessing a client with respiratory system alterations, the nurse must consider risk factors, cultural, and socioeconomic factors that may impact health. Health history, physical examination findings, and diagnostic test results will also play an important role in respiratory system assessment. This section will discuss common assessments, diagnostic tests, and interventions that apply to a variety of respiratory alterations.

Risk Factors

A comprehensive assessment of risk factors allows nurses to identify individuals at risk for respiratory disease and implement prevention interventions. Nurses also consider modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors that may influence a client’s health.[1]

Respiratory risk factors include the following:

- Tobacco Use: One of the most significant modifiable risk factors for respiratory health is tobacco use. Smoking tobacco and exposure to secondhand smoke are linked to a myriad of respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancer. An individual’s smoking history, including duration and number of packs smoked daily, is used to assess their risk for developing respiratory disease. To calculate an individual’s pack years of smoking, multiply the number of packs smoked per day by the number of years the individual has smoked. The pack years of smoking measurement assists providers in understanding cumulative exposure and potential for lung damage and implementing effective preventive interventions.[2],[3]

- Environmental Exposures: Individuals may be exposed to a range of environmental factors that can impact their respiratory health. Occupational hazards (such as exposure to smoke or dust), indoor air pollution, and outdoor air quality can all contribute to the development or exacerbation of respiratory conditions.[4],[5]

- Allergies and Sensitivities: Allergies and sensitivities to airborne allergens, such as pollen, dust mites, pet dander, and mold, can trigger respiratory alterations like asthma.[6],[7],[8]

- Chronic Medical Conditions: Chronic medical conditions, such as obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), can have a direct impact on respiratory health. Obesity can lead to reduced lung function and increased risk of sleep apnea, while GERD can contribute to conditions like chronic cough, asthma, and aspiration pneumonia.[9],[10],[11]

- Family History: A family history of respiratory conditions, such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, or lung cancer, can provide valuable insights into an individual’s genetic predisposition to respiratory issues. Family history is used to assess genetic risk factors and plan appropriate screenings and interventions.[12],[13],[14]

- Lifestyle Factors: Lifestyle factors, including diet, physical activity, stress management, and sleep patterns, can also impact respiratory health. Unhealthy dietary choices, sedentary behavior, and chronic stress can contribute to inflammation and compromise immune function, increasing susceptibility to respiratory infections.[15],[16],[17]

Cultural Factors

Cultural factors encompass a wide range of social, behavioral, and environmental elements that are shaped by cultural norms, beliefs, and practices. These factors can impact an individual’s risk of developing respiratory health alterations. For example, in some cultures, smoking is deeply ingrained as a social or ceremonial practice, while in other cultures, it may be discouraged or even considered taboo. Understanding these cultural attitudes is crucial when assessing an individual’s risk of smoking-related conditions and planning interventions to promote smoking cessation.

Cultural dietary practices can also influence respiratory health, especially in relation to allergies and asthma. Some cultural dietary preferences include foods that may exacerbate allergies or contribute to inflammation, whereas other cultures emphasize dietary patterns that promote lung health. Cultural practices related to cooking methods, fuel sources, and housing construction can also contribute to indoor air pollution, which can increase the risk of respiratory conditions.[18],[19],[20]

Socioeconomic Factors

Socioeconomic factors encompass a range of economic and social determinants that influence living conditions, access to health care, and lifestyle choices. Lower income levels are associated with an increased risk of developing respiratory health alterations. Individuals with limited financial resources may face challenges in accessing health care services, have decreased ability to purchase prescribed medications, or may live in environments with increased pollution that triggers health conditions like asthma or COPD. Individuals with limited financial resources may also delay seeking medical attention due to its cost, leading to advanced disease before it is diagnosed. Lower educational achievement can also impact an individual’s ability to navigate the complex health care system or understand potential treatment options without assistance.[21],[22]

Environmental work hazards can also impact respiratory health. Some occupations, such as construction, agriculture, or manufacturing, may expose workers to environmental hazards like dust, chemicals, or airborne pollutants, increasing their risk of respiratory alterations.[23],[24]

Case Study on Risk Factor Identification

John Spector, a 55-year-old man, visits his primary care physician for a routine check-up. He has a family history of respiratory conditions, with his mother diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in her 60s. John is a lifelong smoker, having started smoking in his late teens and continuing to smoke a pack of cigarettes daily. He works in a dusty, industrial environment and is frequently exposed to airborne pollutants. He states that he is so tired after work, so he usually gets dinner at a fast-food restaurant on the way home and rarely has energy to exercise.

Based on the information provided, assess John for any respiratory health risk factors.

Smoking History: John’s long-term smoking habit is a significant modifiable risk factor for respiratory health alterations. Smoking is a leading cause of conditions like COPD, lung cancer, and exacerbations of asthma. Encouraging smoking cessation should be a primary focus in addressing this risk factor.

Occupational Exposure: John’s workplace exposure to dust and airborne pollutants represents another modifiable risk factor. Long-term exposure to occupational hazards can lead to respiratory conditions, such as occupational asthma or pneumoconiosis. Implementing respiratory protection like masks may help mitigate this risk.

Family History of COPD: John’s family history of COPD is a nonmodifiable risk factor, indicating a genetic predisposition to respiratory issues. While nonmodifiable, it should be considered when assessing his overall respiratory risk.

Age: John’s age of 55 is a nonmodifiable risk factor. Age is a critical consideration in assessing respiratory health risk, as the risk of certain conditions, such as COPD, tends to increase with age.

Lifestyle Factors: In addition to smoking, poor dietary habits and physical inactivity can contribute to obesity, which is associated with respiratory conditions like sleep apnea. Assessing for modifiable risk factors and encouraging lifestyle modifications are also important.

Assessment

A comprehensive assessment of an individual’s overall health is essential because the respiratory system plays a critical role in maintaining the body’s overall functioning. Respiratory alterations can have significant consequences that not only impact respiratory health but also can affect other body systems.

Health History

Nurses gather a detailed health history, paying close attention to personal or family history of respiratory disorders. Questions should include inquiries about asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, bronchitis, or other respiratory conditions.[25]

Family history plays a pivotal role in the emergence of respiratory health alterations. A family history of respiratory diseases in first-degree relatives, such as parents, siblings, or children, can indicate an increased genetic risk for respiratory issues. A close family or significant other’s history of smoking should also be considered because secondhand smoke can impact an individual’s respiratory health.[26]

Nurses assess risk factors known to impact respiratory health. These may include a history of smoking or exposure to environmental pollutants. Detailed information about smoking habits, including pack years, is essential to assess the level of risk. The presence of allergies can also influence respiratory health and should be documented during the assessment.[27]

Travel history and geographical area of residence can also play a role in risk of respiratory health alterations. For example, international travel history can reveal exposure to endemic respiratory infections (e.g., tuberculosis or respiratory viruses). Geographic areas of residence can also pose respiratory risks. Urban areas often have higher levels of air pollution and industrial emissions, increasing the risk of respiratory conditions like asthma and COPD. In contrast, rural areas may pose risks related to agricultural exposures or limited access to health care resources.[28],[29]

Physical Exam

Conducting a thorough examination of body systems provides the nurse with cues regarding potential respiratory disorders. Early identification of abnormal findings and notification of the health care provider can lead to prompt intervention and management and improve client outcomes. Table 6.3a summarizes assessments for each body system.

Table 6.3a. Manifestations of Respiratory Alterations by Body System[30],[31],[32]

| Body System | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Respiratory | Dyspnea, tachypnea, bradypnea, decreased pulse oximetry reading, use of accessory muscles, nasal flaring, adventitious or decreased lung sounds, coughing, sputum production, pleuritic chest pain (worse on deep breathing or coughing), barrel chest (increased anterior-posterior diameter), intercostal retractions, or cyanosis. See Figure 6.9[33] for an image of increased anterior-posterior diameter of the chest. |

| Cardiovascular | Tachycardia (in response to hypoxia) or signs of right-sided heart failure (i.e., jugular vein distention, peripheral edema). |

| Neurological | Altered mental status, confusion, disorientation, dizziness, syncope (fainting), or headaches (due to hypoxia). |

| Musculoskeletal | Decreased activity tolerance, fatigue, and weakness (related to hypoxia). Decreased muscle mass or poor growth in children (due to chronic illness). |

| Integumentary | Clubbing of the nailbeds due to chronic hypoxia. See Figure 6.10[34] for an image of clubbing. |

Focused Respiratory Physical Exam

Respiratory assessment involves a systematic examination of various components, including the nose and sinuses, pharynx, trachea, larynx, lungs, thorax, skin, mucous membranes, general appearance, and activity tolerance.[35]

Nose & Sinuses

- Visually examine the external nose for any deformities, asymmetry, or lesions. Ask the client about nasal congestion, discharge, or frequent nosebleeds, which can indicate sinus or nasal issues.

Pharynx, Trachea, and Larynx

- Use a tongue depressor and a light source to examine the pharynx, looking for any redness, swelling, tonsillar enlargement, or lesions. Ask the client to say “Ah” to assess the movement of the soft palate and uvula and assess the presence of a gag reflex. Assess the trachea for midline positioning. Inspect and palpate the neck for any enlarged lymph nodes or masses. Listen for a husky voice or other voice changes.

Lungs & Thorax

- Observe the client’s chest for shape, symmetry, and any visible abnormalities such as deformities or masses. Use your hands to assess chest expansion, tenderness, crepitus (crackling), or masses. Listen to breath sounds with a stethoscope and note any areas of decreased breath sounds or adventitious sounds such as wheezing, rhonchi (coarse crackles), or rales (fine crackles).

Skin and Mucous Membranes

- Examine the skin for pallor, cyanosis (bluish or grayish discoloration), or clubbing of the fingernails. Check mucous membranes (e.g., lips and gums) for color, moisture, and any signs of dehydration.

General Appearance

- Observe the client’s general appearance for signs of distress, such as increased work of breathing, use of accessory muscles, or restlessness. Assess the respiratory rate and pattern of breathing. Check for increased anterior-posterior ratio of the chest. If the client is experiencing shortness of breath, assess their ability to speak in sentences or their limitation to speaking in phrases or words.

Endurance

- Evaluate the client’s ability to engage in activity without experiencing shortness of breath. Inquire about any limitations in physical activity or recent changes in endurance.

Review comprehensive respiratory assessment in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Life Span Considerations

Infants and Children

There are differences in the pediatric respiratory system compared to an adult. Key differences in the pediatric respiratory system include the following[36],[37]:

- Newborns may have insufficient surfactant, especially if preterm, that can severely impact gas exchange due to alveoli collapse.

- Periods of apnea are common in newborns.

- Infants have significantly fewer alveoli and higher metabolic needs than adults, resulting in faster respiratory rates. For example, the normal respiratory rate for a newborn is 30-60 breaths per minute.

- Infants are obligatory nose breathers. If their nose or nasal passage becomes occluded, they can develop respiratory distress.

- Infants produce little respiratory mucus, so their coughs are nonproductive, thus increasing their risk for respiratory infection.

- Infants and young children have smaller airways, making it easier for them to become occluded with mucus or foreign objects.

- Young children have enlarged tonsillar tissue that can occlude the pharynx, especially when suffering from an upper respiratory infection.

- Infants and young children have a more flexible larynx, making it susceptible to spasm.

- Signs of respiratory distress in infants include respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths per minute, expiratory grunting, nasal flaring on inspiration, or sternal and intercostal retractions.

Older Adults

As individuals age, these changes occur that affect the lungs and breathing[38]:

- Changes to the bones and muscles of the chest and spine: Bones become thinner, and the shape of the rib cage may change. As a result, the rib cage may not expand and contract as well during breathing. The diaphragm also becomes weakened and can decrease the ability to inhale.

- Changes to lung tissue: Muscles and other tissues near the airways may lose their ability to keep the airways completely open, causing them to close easily. The air sacs in the alveoli lose their shape and become baggy. These changes in lung tissue can allow air to become trapped in the lungs, decreasing the amount of gas exchange at the alveolar level.

- Changes to the nervous system: The part of the brain that controls breathing may lose some of its function. Nerves in the airways that trigger coughing also become less sensitive. Large amounts of particles like smoke or germs may collect in the lungs and may be hard to cough up.

- Changes to the immune system: The immune system can get weaker, making it more difficult for the body to fight lung infections and other diseases. The lungs are also less able to recover after exposure to smoke or other harmful particles.

As a result of these changes, older adults are at increased risk for the following[39]:

- Lung infections, such as pneumonia and bronchitis

- Shortness of breath

- Lower oxygen saturation levels

- Abnormal breathing patterns, resulting in problems such as sleep apnea (episodes of stopped breathing during sleep)

Read additional information about performing a focused subjective and objective respiratory assessment in the “Respiratory Assessment” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Signs of Hypoxia and Respiratory Distress

Nurses must recognize and report early signs of hypoxia to prevent the client from progressing to respiratory arrest, the cessation of breathing. Hypoxia can have many causes, ranging from respiratory and cardiac conditions to anemia. Signs and symptoms of hypoxia and respiratory distress are as follows[40]:

- New onset or worsening dyspnea: Dyspnea is a subjective symptom of not getting enough air. Depending on severity, dyspnea causes increased levels of anxiety.

- Restlessness

- New onset confusion or worsening level of consciousness

- Tachycardia: An elevated heart rate (greater than 100 beats per minute in adults) can be an early sign of hypoxia as the heart compensates for decreased oxygenation.

- Tachypnea: A sustained increased respiration rate (above 20 breaths per minute in an adult) is a sign of respiratory distress.

- Worsening oxygen saturation level (SpO2): Oxygen saturation levels should be above 92% for an adult in room air. If oxygen therapy is already in place and SpO2 continues to decrease, this is also a sign of respiratory distress.

- Use of accessory muscles

- Noisy breathing: Audible noises with breathing are an indication of respiratory conditions.

- Positioning: Clients with dyspnea tend to sit up and lean over by resting their arms on their legs, referred to as the tripod position, to enhance lung expansion. They typically feel worse shortness of breath when lying flat in bed and avoid the supine position.

- Ability of client to speak in full sentences: Clients in respiratory distress may be unable to speak in full sentences or may need to catch their breath between sentences.

- Cyanosis: Bluish changes in skin color and mucus membranes is a late sign of hypoxia.

Psychosocial Assessment

Psychosocial factors can play a significant role in the experience of individuals dealing with respiratory problems. Stress and psychological well-being can impact the symptoms and management of respiratory conditions, and chronic respiratory conditions can also significantly affect an individual’s sense of well-being.

Stress and anxiety can worsen respiratory symptoms by triggering the sympathetic nervous system’s “flight or fight” response, thereby increasing respiratory rate and causing shallow respirations. Rapid, shallow breathing can worsen the clinical status of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. Prolonged stress can also weaken an individual’s immune system, making individuals more susceptible to respiratory infections.

Individuals who have chronic respiratory disease may experience stress and anxiety as a result of their feelings of dyspnea. This anxiety may result in social isolation as the individual attempts to avoid environmental triggers (like smoke) or the fear of appearing symptomatic in public. Additionally, chronic disease can also lead to financial stress due to the cost of medications and respiratory equipment.

To help individuals cope with psychosocial challenges associated with respiratory problems, nurses can provide support in numerous ways. Clients may benefit from stress reduction techniques such as relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and yoga. Individuals may also benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation or peer support programs.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing is ordered by health care providers to identify and diagnose respiratory conditions. There are various laboratory and diagnostic results that nurses review related to a comprehensive respiratory assessment and development of an effective nursing care plan.

Laboratory Tests

Common laboratory tests related to respiratory assessment include red blood cells (RBCs), hemoglobin (HGB), hematocrit (HCT), white blood cells (WBCs), and arterial blood gas (ABG)[41],[42]:

- Red Blood Cells (RBCs): This test measures the number of red blood cells in a given volume of blood. Low RBC counts (i.e., anemia) can lead to reduced oxygen-carrying capacity in the blood, which can impact respiratory function.

- Hemoglobin (Hgb) and Hematocrit (HCT): Hemoglobin (hGB) is a protein in red blood cells that binds to oxygen. Low hemoglobin levels can indicate anemia, which can cause respiratory symptoms like fatigue, shortness of breath, and reduced activity tolerance. Hematocrit (HCT) measures the percentage of blood volume occupied by red blood cells. Low hematocrit levels are also associated with anemia and can affect oxygen transport in the bloodstream, although they can also be affected by an individual’s fluid balance.

- White Blood Cells (WBCs): White blood cell levels indicate the immune system’s response to fight infections. Elevated WBC counts can be a sign of an infection or inflammation in the respiratory system, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

- Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs): ABG analysis involves measuring the levels of dissolved oxygen (PaO2), dissolved carbon dioxide (PaCO2), pH, bicarbonate (HCO3-), and oxygen saturation (SaO2) in arterial blood. ABGs provide valuable information about a client’s respiratory and metabolic status. When assessing a client in respiratory distress, one of the most definitive signs requiring medical intervention is abnormal ABG results.

- PaO2: PaO2 is the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood. Low PaO2 levels indicate hypoxemia.

- PaCO2: PaCO2 is the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood. High PaCO2 levels, referred to as hypercapnia, may be seen in acute conditions like acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- pH: pH refers to the blood’s acidity or alkalinity. Abnormally low pH levels can indicate respiratory acidosis (resulting from elevated PaCO2 levels) or metabolic acidosis. Abnormally high pH levels can indicate respiratory alkalosis (caused by reduced PaCO2 levels) or metabolic alkalosis.

- HCO3-: Bicarbonate levels reflect the body’s metabolic compensation for respiratory acid-base imbalances. Elevated HCO3- may indicate compensation by the kidneys for respiratory acidosis.

- SaO2: Oxygen saturation measures the percentage of hemoglobin that is carrying oxygen. A low SaO2 indicates poor oxygenation of the blood.

Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Read more information about ABG tests in the “Acid-Base Balance” section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Sputum Tests

Sputum refers to the mucus and other material that is coughed up by a client from the lower airways (bronchi and lungs) and can be examined for diagnostic purposes. Sputum tests can help identify the presence of pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, or fungi in the respiratory tract. It can also contain inflammatory markers like white blood cells that can indicate inflammation in the airways.

Sputum culture and sensitivity tests help determine the specific type of bacteria that is causing a respiratory infection and its susceptibility and responsiveness to different antibiotics. Sputum samples may also undergo cytology testing that detects the presence of abnormal cells, such as lung cancer.[43]

Diagnostic Tests

Common diagnostic tests for respiratory alterations include radiographic examinations, pulmonary functions tests, bronchoscopy, and thoracentesis.

Radiographic Examinations

Radiographic examinations refer to imaging that provides information about the structure and function of the respiratory system. These tests allow providers to diagnose and monitor the progression of different respiratory conditions, as well as evaluate the client’s response to treatment. Common radiographic examinations are as follows:

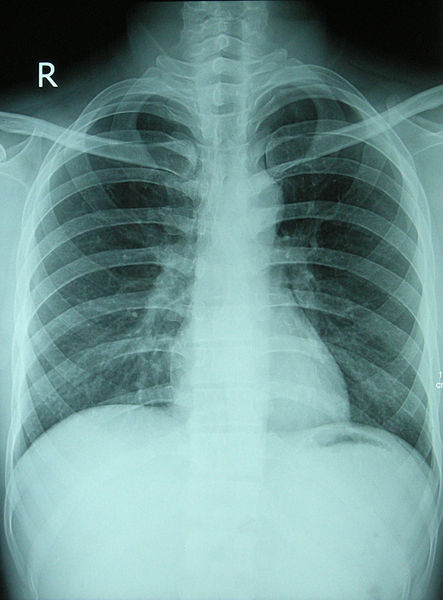

- Standard Chest X-Rays: A standard chest X-ray provides a quick and relatively low-radiation way to visualize the chest area, including the lungs, heart, ribs, and diaphragm. It is useful for identifying lung abnormalities like pneumonia, tuberculosis, cancerous masses, and pleural effusions. Chest X-rays also allow for the visualization of the heart and can help identify rib and chest wall injuries. See Figure 6.11[44] for an image of a chest X-ray on a healthy individual.

- Digital Chest Radiography: Digital chest radiography provides an advanced form of chest-ray imaging, allowing for improved image quality, digital retrieval, and comparison to previous X-rays, as well as remote consultation with other health care providers. Digital radiography also causes less radiation exposure.

- Computed Tomography (CT): CT scans provide cross-sectional, three-dimensional images of the chest and lungs. They allow for a detailed examination of the size and shape of organs, as well as lesions and nodules. CT scans are helpful for staging lung cancer, evaluating trauma, and detecting blood clots in the lungs. CTs are also helpful for guiding more invasive procedures such as lung biopsies and drain tube insertion.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan: A PET scan is a medical imaging technique that provides information about the metabolic and functional activity of tissues within the body. PET scans utilize a small amount of radioactive substance injected into the client’s bloodstream that is metabolized more rapidly by tumors or regions of inflammation.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): An MRI can provide detailed images of the chest that are useful for evaluating vascular conditions, detecting lung tumors, and assessing congenital anomalies.

- Fluoroscopy: Fluoroscopy is an imaging technique that can assess the movement of the diaphragm and chest structures during respiration. It is useful for examining obstruction and guiding invasive procedures like bronchoscopy.

- Lung Biopsy: A medical procedure where a small piece of lung tissue is removed and analyzed under a microscope. The test may be performed using a needle, an open procedure or through a bronchoscope. The approach depends on the client’s underlying health and the location of the tissue to be examined.

- Capnography: A sensor that measures the concentration of carbon dioxide exhaled, translated into a waveform and numerical value.

- V/Q Scan: A ventilation-perfusion (VQ) scan is a diagnostic test used to assess lung function and rule out pulmonary embolism. In this test, a radioactive substance is inhaled (ventilation) and injected into the bloodstream (perfusion). Areas with normal ventilation but reduced perfusion may indicate a pulmonary embolism. The VQ scan helps aid in the diagnosis or exclusion of pulmonary embolism without exposing the patient to ionizing radiation from traditional imaging methods.[45],[46]

Pulmonary Function Tests

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are a group of noninvasive diagnostic tests that assess the function of the respiratory system. These tests provide valuable information about lung capacity, airflow, and gas exchange. Common pulmonary function tests include spirometry, diffusion capacity testing, and bronchial responsiveness tests.

- Spirometry is useful for diagnosing conditions like asthma and COPD by providing information about lung volume and airflow resistance. See Figure 6.12[47] for an image of an individual performing a spirometry test by breathing into a machine with the nostrils occluded. Spirometry involves the examination of these lung function parameters:

- Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1): The volume of air exhaled in the first second of forced expiration.

- Forced vital capacity (FVC): The maximum amount of air that can be exhaled after a deep inhalation.

- FEV1/FVC ratio: This ratio of FEV1 and FVC is used to assess airflow obstruction.

- Diffusion capacity testing measures the lung’s ability to transfer gases from alveoli into the bloodstream. Diffusion capacity testing is useful for detecting gas exchange disorders such as emphysema and pulmonary embolism.

- Bronchial responsiveness testing measures the responsiveness of the airway after it has been exposed to an allergen or bronchoconstrictive substance. This test is useful for diagnosing asthma.[48]

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy is a medical procedure used to directly view airway structures and obtain tissue samples for biopsy or culture. During a bronchoscopy procedure, a provider will insert a thin, flexible tube with a camera and light through the nostril or oropharynx to visualize the airway structures and obtain samples. Because this is an invasive procedure, clients must provide written informed consent acknowledging their understanding of the procedure and its risks after they are explained by the health care provider.

To prevent complications such as aspiration, clients should be instructed to adhere to NPO restrictions for four to eight hours prior to the procedure. Many clients receive medications such as benzodiazepines to help them relax and decrease their anxiety before the procedure.

During the procedure, clients are carefully monitored with continuous vital signs monitoring and provided supplemental oxygen. Peripheral IV access is also maintained to provide medications as needed to support client comfort and promote hemodynamic stability. Following bronchoscopy, clients should be carefully observed to ensure their gag reflex has returned prior to consuming fluids or food.[49],[50]

See Figure 6.13[51] for an image of a bronchoscopy procedure.

Thoracentesis

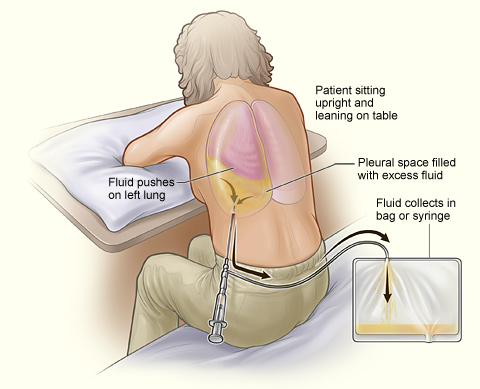

Thoracentesis is a medical procedure performed to remove fluid or air from the pleural space, which is the space between the lung and the chest wall. It is done to diagnose and treat various conditions, including pleural effusion (accumulation of fluid), pneumothorax (accumulation of air), or to obtain a sample for diagnostic purposes. Thoracentesis can help diagnose the underlying cause of pleural effusion, such as infection, cancer, or heart failure. It can also assist in identifying the type of fluid present. In cases of large pleural effusions or tension pneumothorax, thoracentesis can help relieve symptoms and improve respiratory function.[52] See Figure 6.14[53] for an illustration of a thoracentesis.

During a thoracentesis, the client is positioned sitting on the edge of the bed or lying on the unaffected side. The skin over the puncture site is cleaned and sterilized. A local anesthetic is injected into the skin and deeper tissues to numb the area where the needle will be inserted. A needle is inserted through the back and into the pleural space under ultrasound guidance or using physical landmarks. Using a syringe or vacuum bottle, the health care provider withdraws the fluid or air from the pleural space. The collected fluid or air is sent to the laboratory for analysis, including cell counts, chemistry, and microbiology to determine the cause.[54]

After the procedure, the client is closely monitored for any signs of complications, such as bleeding, infection, or pneumothorax. A chest X-ray is often performed to ensure that the lung has re-expanded properly and there are no complications, such as a pneumothorax. In some cases, if large volumes of fluid need to be drained or there is a risk of recurrence, a chest tube may be placed to allow continuous drainage.[55]

Complications of thoracentesis can include bleeding, infection, pneumothorax, and damage to surrounding structures. These risks are minimized by using ultrasound guidance and taking appropriate precautions during the procedure.[56]

See the following box for client preparation and additional information about the thoracentesis procedure.

Nursing Considerations Regarding Thoracentesis[57],[58]

Before the Procedure

Prior to the procedure, the health care provider must explain the purpose, potential risks, and benefits of the procedure. The nurse ensures the client has provided written informed consent signifying their understanding.

During the Procedure

Proper client positioning is crucial. The client may need to sit on the edge of the bed or lie on their side in a specific posture to allow for safe access to the pleural space. Health care providers will guide clients into the correct position. Clients are advised to remain as motionless as possible during the procedure to minimize the risk of injury. Clients should be informed that they may experience a stinging sensation and pressure during the procedure.

During the procedure, a short, thin needle is carefully inserted by the health care provider through the skin and into the pleural space under sterile conditions, typically done under local anesthesia. After the needle is in position, pleural fluid or air is slowly aspirated into a syringe, relieving pressure in the pleural space.

After the Procedure

Immediately after the procedure, a chest X-ray is typically performed to assess lung re-expansion and monitor for complications such as a pneumothorax. Vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation, are closely monitored. Breath sounds are auscultated to check for signs of complications. Clients are encouraged to take deep breaths and use incentive spirometers to prevent atelectasis and expand the lungs.

Thoracentesis procedures are considered relatively safe, but there are potential complications. Complications may include a reaccumulation of fluid, subcutaneous emphysema, infection, or tension pneumothorax. If pleural fluid reaccumulates in the pleural space, a drain might be required. Subcutaneous emphysema occurs when air leaks from the pleural space into subcutaneous tissue, resulting in crepitus and swelling. Subcutaneous emphysema typically resolves on its own. Tension pneumothorax occurs when pressure builds within the pleural space and compresses the lung. If a tension pneumothorax occurs, the heart and mediastinal structures are shifted toward the opposite of the chest, resulting in respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Tension pneumothorax can often develop rapidly and result in severe difficulty breathing, chest pain, cyanosis, and decreased breath sounds. Immediate intervention is required and involves the insertion of a large bore needle or chest tube on the affected side of the chest to release the trapped air and decompress the pleural space.[59],[60]

General Nursing Interventions Related to Respiratory Alterations

This section will provide an overview of common nursing interventions that may be implemented for a variety of respiratory alterations.

Dyspnea and Hypoxia

No matter the cause, respiratory alterations can cause dyspnea, hypoxia, or hypercapnia. Hypoxia and/or hypercapnia are medical emergencies and should be treated promptly by calling for assistance as indicated by agency policy.

Failure to initiate oxygen therapy for hypoxia can result in serious harm or death of the client. Although oxygen is considered a medication that requires a prescription, oxygen therapy may be initiated without a physician’s order in emergency situations as part of the nurse’s response to the “ABCs,” a common abbreviation for airway, breathing, and circulation. Most agencies have a protocol in place that allows nurses to apply oxygen in emergency situations and obtain the necessary order at a later time.

In addition to administering oxygen therapy, there are several general interventions a nurse can implement to immediately assist a client with dyspnea and possible hypoxia as outlined in Table 6.3b.

Table 6.3b. General Nursing Interventions to Manage Dyspnea and Hypoxia

| Interventions | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Raise the head of the bed or use tripod positioning. | Raising the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position promotes effective chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, maximizes inhalation, and decreases the work of breathing. Clients with dyspnea may also gain relief by sitting upright and leaning over a bedside table while in bed, which is called a three-point or tripod position. |

| Encourage enhanced breathing and coughing techniques. | Enhanced breathing and coughing techniques such as using pursed-lip breathing, coughing and deep breathing, huffing technique, incentive spirometry, and flutter valves may assist clients to clear their airway while maintaining their oxygen levels. See the “Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques” section below for additional information regarding these techniques. |

| Manage oxygen therapy and equipment. | If the client is already receiving supplemental oxygen, ensure the equipment is turned on, set at the required flow rate, and is properly connected to an oxygen supply source. If a portable tank is being used, check the oxygen level in the tank. Ensure the connecting oxygen tubing is not kinked, which could obstruct the flow of oxygen. Feel for the flow of oxygen from the exit ports on the oxygen equipment. In hospitals where medical air and oxygen are used, ensure the client is connected to the oxygen flow port.

Various types of oxygenation equipment are prescribed for clients requiring oxygen therapy. Oxygenation equipment is typically managed in collaboration with a respiratory therapist in hospital settings. Equipment includes devices such as nasal cannula, masks, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), and mechanical ventilators. For more information, see the “Oxygenation Equipment” section of the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e. |

| Assess the need for respiratory medications. | Pharmacological management is essential for clients with respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, or severe allergic response. Bronchodilators effectively relax smooth muscles and open airways. Glucocorticoids relieve inflammation and also assist in opening air passages. Mucolytics decrease the thickness of pulmonary secretions so that they can be expectorated. |

| Provide suctioning, if needed. | Some clients may have a weakened cough that inhibits their ability to clear secretions from the mouth and throat. Clients with muscle disorders or those who have experienced a stroke (i.e., cerebral vascular accident) are at risk for aspiration, which could lead to pneumonia and hypoxia. Provide oral suction if the client is unable to clear secretions from the mouth and pharynx. |

| Provide pain relief, if needed. | Provide adequate pain relief if the client is reporting pain because it can cause shallow breathing. Pain may be exacerbated with lung expansion, especially after thoracic or abdominal surgeries. Pain increases anxiety and metabolic demands, which, in turn, increase the need for oxygen and feelings of dyspnea. |

| Consider other devices to enhance clearance of secretions. | Chest physiotherapy and specialized devices assist with secretion clearance, such as handheld flutter valves or vests that inflate and vibrate the chest wall. Consult with a respiratory therapist as needed based on the client’s situation. |

| Plan frequent rest periods between activities. | Plan interventions for clients with dyspnea so they can rest frequently and decrease oxygen demand. |

| Consider other potential causes of dyspnea. | If a client’s level of dyspnea is worsening, assess for other underlying causes in addition to the primary diagnosis. For example, are there other respiratory, cardiovascular, or hematological conditions occurring? Start by reviewing the client’s most recent hemoglobin and hematocrit lab results, as well as any other diagnostic tests such as chest X-rays and ABG results. Completing a thorough assessment may reveal abnormalities in these systems to report to the health care provider. |

| Consider obstructive sleep apnea. | Clients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are often not previously diagnosed prior to hospitalization. The nurse may notice the client snores, has pauses in breathing while snoring, has decreased oxygen saturation levels while sleeping, or awakens feeling not rested. These signs may indicate the client is unable to maintain an open airway while sleeping, resulting in periods of apnea and hypoxia. If these apneic periods are noticed but have not been previously documented, the nurse should report these findings to the health care provider for further testing and follow-up. A prescription for a CPAP or BiPAP device while sleeping may be needed to prevent adverse outcomes. |

| Monitor client’s anxiety. | Assess and address anxiety. Anxiety often accompanies the feeling of dyspnea and can worsen it. Nurses use nonpharmacological approaches such as teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques and encouraging relaxation techniques. If these approaches are not effective, then antianxiety medications may be prescribed by the health care provider. |

Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques

In addition to oxygen therapy and general interventions listed in Table 6.3b to address dyspnea, there are several techniques a nurse can teach a client to enhance their breathing and coughing. These techniques include pursed-lip breathing, diaphragmatic breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing and deep breathing, and the huffing technique. Additionally, vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy can be incorporated in collaboration with a respiratory therapist.

Pursed-lip Breathing

Pursed-lip breathing is a technique that decreases dyspnea by teaching people to control their oxygenation and ventilation. See Figure 6.15[61] for an illustration of pursed-lip breathing. The technique teaches a person to inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth at a slow, controlled flow. This type of exhalation gives the person a puckered or pursed-lip appearance. By prolonging the expiratory phase of respiration, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. This subsequently reduces air trapping that commonly occurs in conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Pursed-lip breathing relieves the feeling of shortness of breath, decreases the work of breathing, and improves gas exchange. People also regain a sense of control over their breathing while simultaneously increasing their relaxation.[62]

Diaphragmatic Breathing

When breathing normally, individuals typically don’t use their full lung capacity. Diaphragmatic breathing, also called abdominal breathing, encourages them to consciously use their diaphragm to take deep breaths. This promotes lung efficiency by using the lungs at 100% capacity.[63]

When teaching the diaphragmatic breathing technique, it may be easier for the client to follow your instructions lying down[64]:

- Lie on your back on a flat surface or in bed, with your knees bent and your head supported. You can use a pillow under your knees to support your legs.

- Place one hand on your upper chest and the other just below your rib cage. This will allow you to feel your diaphragm move as you breathe.

- Breathe in slowly through your nose so that your stomach moves out, causing your hand to rise. The hand on your chest should remain as still as possible.

- Tighten your stomach muscles, so that your stomach moves in, causing your hand to lower as you exhale through pursed lips (see “Pursed-lip Breathing” section above). The hand on your upper chest should remain as still as possible.

When first learning diaphragmatic breathing, clients should be encouraged to complete this exercise for five to ten minutes about three to four times per day and then gradually increase the amount of time spent doing this exercise.[65]

Incentive Spirometry

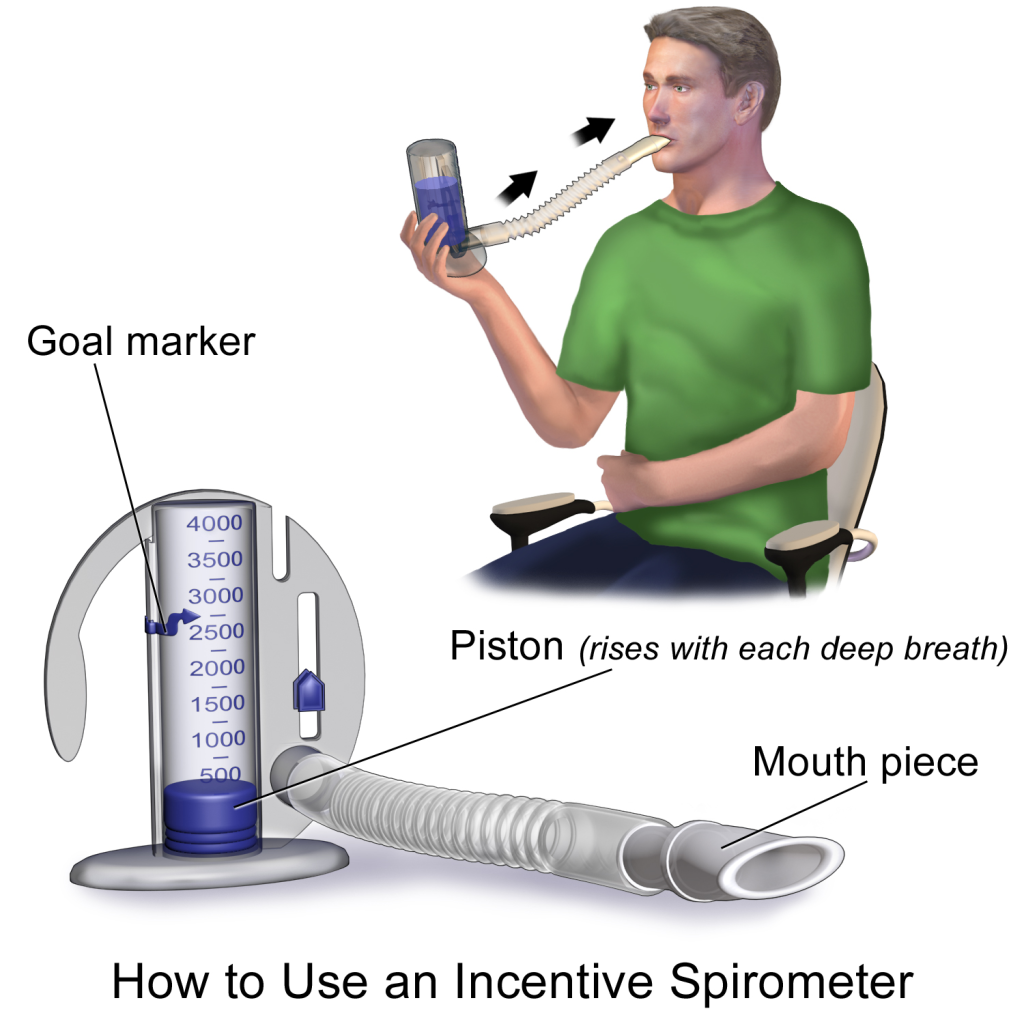

An incentive spirometer is a medical device commonly prescribed after surgery to expand the lungs, reduce the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and prevent pneumonia. See Figure 6.16[66] for an image of a client using an incentive spirometer. While sitting upright, if possible, the client should place the mouthpiece in their mouth and create a tight seal with their lips around it. They should breathe in slowly and as deeply as possible through the tubing with the goal of raising the piston to their prescribed level. The resistance indicator on the right side should be monitored to ensure they are not breathing in too quickly. The client should attempt to hold their breath for as long as possible (at least five seconds) and then exhale and rest for a few seconds. Coughing is expected. Encourage the client to expel the mucus and not swallow it. This technique should be repeated by the client ten times every hour while awake.[67] The nurse may delegate this intervention to unlicensed assistive personnel, but the frequency in which it is completed and the volume achieved should be documented and monitored by the nurse.

Coughing and Deep Breathing

Coughing and deep breathing is a breathing technique similar to incentive spirometry but no device is required. The client is encouraged to take deep, slow breaths and then exhale slowly. After each set of breaths (typically three to five), the client should cough. This technique is repeated three to five times every hour. The client may be encouraged to splint the chest with a pillow or folded blanket to help facilitate deep breathing and coughing.

Huffing Technique

The huffing technique is helpful to teach clients who have difficulty coughing. Teach the client to inhale with a medium-sized breath and then make a sound like “Ha” to push the air out quickly with the mouth slightly open.

Vibratory PEP Therapy

Vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy uses handheld devices such as flutter valves or Acapella devices for clients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. These devices require a prescription and are used in collaboration with a respiratory therapist or advanced health care provider. To use vibratory PEP therapy, the client should sit up, take a deep breath, and blow into the device. A flutter valve within the device creates vibrations that help break up the mucus so the client can cough and spit it out. Additionally, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. See Figure 6.17[68] for an image of PEP therapy.

Routine Nursing Interventions Related to Respiratory Management

The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) is a standardized classification of nurse-initiated and physician-initiated nursing treatments. There are several NIC classifications of nursing interventions that apply across multiple respiratory disorders such as “Respiratory Monitoring” and “Oxygen Therapy.” Read more about these categories of interventions in the following boxes.

Selected NIC Nursing Interventions for Respiratory Monitoring[69]

NIC definition of respiratory monitoring: Collecting and analyzing pertinent data to ensure airway patency and adequate air exchange, including, but not limited to, the following:

- Monitor rate, rhythm, depth, and effort of respirations.

- Note chest movement, watching for symmetry, use of accessory muscles, and supraclavicular and intercostal muscle retractions.

- Auscultate breath sounds, noting areas of decreased or absent ventilation and presence of adventitious sounds.

- Monitor oxygen saturation levels. Provide for noninvasive continuous oxygen sensors with appropriate alarm systems in clients with risk factors for hypoxia per agency policy and as indicated.

- Determine the need for suctioning by auscultating for rhonchi (coarse crackles) over major airways.

- Monitor for signs of hypoxia, such as increased restlessness, anxiety, and air hunger.

- Monitor the client’s ability to cough effectively.

- Note onset, duration, and characteristics of cough.

- Monitor the client’s respiratory secretions.

- Monitor for dyspnea and events that improve and worsen it.

- Monitor chest X-ray reports.

Selected NIC Nursing Interventions for Oxygen Therapy[70]

NIC definition of oxygen therapy: Safely administering oxygen and monitoring its effectiveness, including, but not limited to, the following:

- Verify order for oxygen therapy (unless it is an emergency situation).

- Document baseline observations, including respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and blood pressure.

- Position for optimal breathing efficiency (e.g., high Fowler’s or semi-Fowler’s positions).

- Clear oral, nasal, and tracheal secretions to optimize airway patency.

- Ensure flow meter is set to prescribed dose.

- Attach a humidifying unit to the flow meter to avoid mucosal drying, as indicated.

- Instruct the client and family members about safety precautions associated with oxygen use, including the need to avoid smoking, candles, and other sources of open flame.

- Monitor for skin breakdown related to the oxygen delivery device.

- Provide for oxygen during transport.

- Change oxygen delivery device from mask to nasal cannula during meals, as tolerated.

- Evaluate and document effectiveness of oxygen therapy (e.g., pulse oximetry, respiratory rate, heart rate).

Review additional information in the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Chronic respiratory diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1 ↵

- American Lung Association. (2023, April 28). COPD causes and risk factors. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd/what-causes-copd ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, July 31). What is lung cancer? https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/what-is-lung-cancer.htm ↵

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2023, June 26). Particle pollution and respiratory effects. https://www.epa.gov/pmcourse/particle-pollution-and-respiratory-effects ↵

- American Lung Association. (2023, April 17). Disparities in the impact of air pollution. https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/who-is-at-risk/disparities ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Chronic respiratory diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1 ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). Respiratory failure: Causes and risk factors. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/respiratory-failure/causes ↵

- Gaffney, A. W., Himmelstein, D. U., Christiani, D. C., & Woolhandler, S. (2021). Socioeconomic inequality in respiratory health in the US from 1959 to 2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(7), 968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2441 ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Chronic respiratory diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1 ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). Respiratory failure: Causes and risk factors. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/respiratory-failure/causes ↵

- Gaffney, A. W., Himmelstein, D. U., Christiani, D. C., & Woolhandler, S. (2021). Socioeconomic inequality in respiratory health in the US from 1959 to 2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(7), 968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2441 ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Chronic respiratory diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1 ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). Respiratory failure: Causes and risk factors. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/respiratory-failure/causes ↵

- Gaffney, A. W., Himmelstein, D. U., Christiani, D. C., & Woolhandler, S. (2021). Socioeconomic inequality in respiratory health in the US from 1959 to 2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(7), 968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2441 ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Chronic respiratory diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1 ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). Respiratory failure: Causes and risk factors. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/respiratory-failure/causes ↵

- Gaffney, A. W., Himmelstein, D. U., Christiani, D. C., & Woolhandler, S. (2021). Socioeconomic inequality in respiratory health in the US from 1959 to 2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(7), 968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2441 ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Chronic respiratory diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1 ↵

- Gaffney, A. W., Himmelstein, D. U., Christiani, D. C., & Woolhandler, S. (2021). Socioeconomic inequality in respiratory health in the US from 1959 to 2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(7), 968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2441 ↵

- Li, X., Cao, X., Guo, M., Xie, M., & Liu, X. (2020). Trends and risk factors of mortality and disability adjusted life years for chronic respiratory diseases from 1990 to 2017: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The British Medical Journal, 368, m234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m234 ↵

- Gaffney, A. W., Himmelstein, D. U., Christiani, D. C., & Woolhandler, S. (2021). Socioeconomic inequality in respiratory health in the US from 1959 to 2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(7), 968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2441 ↵

- Li, X., Cao, X., Guo, M., Xie, M., & Liu, X. (2020). Trends and risk factors of mortality and disability adjusted life years for chronic respiratory diseases from 1990 to 2017: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The British Medical Journal, 368, m234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m234 ↵

- Gaffney, A. W., Himmelstein, D. U., Christiani, D. C., & Woolhandler, S. (2021). Socioeconomic inequality in respiratory health in the US from 1959 to 2018. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(7), 968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2441 ↵

- Cheatham, D., & Marechal, I. (2018, July 12). Respiratory health disparities in the United States and their economic repercussions. Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/respiratory-health-disparities-in-the-united-states-and-their-economic-repercussions/ ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Medical history and physical examination for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/medical-history-and-physical-examination-for-lung-disorders ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Medical history and physical examination for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/medical-history-and-physical-examination-for-lung-disorders ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Medical history and physical examination for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/medical-history-and-physical-examination-for-lung-disorders ↵

- Teall, A. M., Pittman, O. A., & Pandian, V. (2020). Evidence-based assessment of the lungs and respiratory system. In Gawlik, K. S., Melnyk, B. M., & Teall, A. M. (Eds.). Evidence-based physical examination: Best practices for health & well-being assessment. Springer Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826164544.0007 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Reyes, Modi, & Le and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Teall, A. M., Pittman, O. A., & Pandian, V. (2020). Evidence-based assessment of the lungs and respiratory system. In Gawlik, K. S., Melnyk, B. M., & Teall, A. M. (Eds.). Evidence-based physical examination: Best practices for health & well-being assessment. Springer Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826164544.0007 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Reyes, Modi, & Le and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Medical history and physical examination for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/medical-history-and-physical-examination-for-lung-disorders ↵

- “Normal A-P Chest Image.jpg” and “Barrel Chest.jpg” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Clubbing of fingers in IPF.jpg” by IPFeditor is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Reyes, Modi, & Le and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Connelly, S., Meissbach, S., Schmidt, M., & Ascano, F. (2022). Respiratory system in pediatrics. Stanford Medicine Children's Health. https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/content-public/pdf/respiratory-system-in-pediatrics.pdf ↵

- Saikia, D., & Mahanta, B. (2019). Cardiovascular and respiratory physiology in children. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 63(9), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.IJA_490_19 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2023. Aging changes in the lungs; [reviewed 2022, Jul 21; cited 2023, Oct 30]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004011.htm ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2023. Aging changes in the lungs; [reviewed 2022, Jul 21; cited 2023, Oct 30]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004011.htm ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals,2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Overview of tests for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/arterial-blood-gas-abg-analysis-and-pulse-oximetry ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- “Chest_X-ray_2346.jpg” by Doctoroftcm is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Overview of tests for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/arterial-blood-gas-abg-analysis-and-pulse-oximetry ↵

- “DoingSpirometry.JPG” by Jmarchn is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2023, Oct 24]. Lung function tests; [cited 2023, Oct. 30]. https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/lung-function-tests/ ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Overview of tests for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/arterial-blood-gas-abg-analysis-and-pulse-oximetry ↵

- “Bronchoskopie_Bronchoalveoläre_Lavage.jpg” by User:MrArifnajafov is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- “Thoracentesis.jpg” by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Overview of tests for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/arterial-blood-gas-abg-analysis-and-pulse-oximetry ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Lung procedures, tests, and treatments. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests ↵

- Dezube, R. (2022, September). Overview of tests for lung disorders. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/lung-and-airway-disorders/diagnosis-of-lung-disorders/arterial-blood-gas-abg-analysis-and-pulse-oximetry ↵

- “v4-460px-Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease-Step-8.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Access for free at https://www.wikihow.com/Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Nguyen and Duong and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Diaphragmatic breathing. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9445-diaphragmatic-breathing ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Diaphragmatic breathing. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9445-diaphragmatic-breathing ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Diaphragmatic breathing. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9445-diaphragmatic-breathing ↵

- “Incentive Spirometer.png” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2018, May 2). Incentive spirometer. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/4302-incentive-spirometer ↵

- “Flutter Valve Breathing Device 3I3A0982.jpg” by Deanna Hoyord, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Wagner, C. M., Butcher, H. K., & Clarke, M. F. (2024). Nursing interventions classifications (NIC) (8th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- Wagner, C. M., Butcher, H. K., & Clarke, M. F. (2024). Nursing interventions classifications (NIC) (8th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

Understanding the Legal System

There are several types of laws and regulations that affect nursing practice. Laws are rules and regulations created by a society and enforced by courts and professional licensure boards. Nurses are responsible for being aware of public and private laws that affect client care, as well as legal actions that can result when these laws are broken.

Laws are generally classified as public or private law. Public law regulates relations of individuals with the government or institutions, whereas private law governs the relationships between private parties.

Public Law

There are several types of public law, including constitutional, statutory, administrative, and criminal law.

- Constitutional law refers to the rights, privileges, and responsibilities established by the U.S. Constitution.[1] The right to privacy is an example of a patient right based on constitutional law.

- Statutory law refers to written laws enacted by the federal or state legislature. For example, the Nurse Practice Act in each state is an example of statutory law enacted by that state’s legislature. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is an example of a federal statutory law. HIPAA required the creation of national standards to protect sensitive client health information from being disclosed without the client's consent or knowledge.

- Administrative law is law created by government agencies that have been granted the authority to establish rules and regulations to protect the public.[2] An example of federal administrative law is the regulations set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). OSHA was established by Congress to ensure safe and healthy working conditions for employees by setting and enforcing federal standards. An example of administrative law at the state level is the State Board of Nursing (SBON). The SBON is a group of individuals in each state, established by that state’s legislature, to develop, review, and enforce the Nurse Practice Act. The SBON also issues nursing licenses to qualified candidates, investigates reports of nursing misconduct, and implements consequences for nurses who have violated the Nurse Practice Act.

- Criminal law is a system of laws concerned with punishment of individuals who commit crimes.[3] A crime is a behavior defined by Congress or state legislature as deserving of punishment. Crimes are classified as felonies, misdemeanors, and infractions. Conviction for a crime requires evidence to show the defendant is guilty beyond a shadow of doubt. This means the prosecution must convince a jury there is no reasonable explanation other than guilty that can come from the evidence presented at trial. In the United States, an individual is considered innocent until proven guilty. See Figure 5.1[4] for an illustration of a trial with a jury.

Serious crimes that can result in imprisonment for longer than one year are called felonies. Felony convictions can also result in the loss of voting rights, the ability to own or use guns, and the loss of one’s nursing license. An example of a felony committed by some nurses is drug diversion of controlled substances.

Misdemeanors are less serious crimes resulting in penalties of fines and/or imprisonment for less than one year. For example, in Wisconsin, misdemeanors are categorized as Class A, B, or C based on their sentencing. Class A misdemeanors are sentenced to a fine not to exceed $10,000 or imprisonment not to exceed nine months, or both. Class B misdemeanors are sentenced to a fine not to exceed $1,000 or imprisonment not to exceed 90 days, or both. Class C misdemeanors are sentenced to a fine not to exceed $500 or imprisonment not to exceed 30 days, or both.[5] Examples of misdemeanors include battery, possession of controlled substances, petty theft, disorderly conduct, and driving under the influence (DUI) charges. Although considered less serious crimes, misdemeanors can impact an individual’s ability to obtain or maintain a nursing license.

Nurses who are found guilty of misdemeanors or felonies, regardless if the violation is related to the practice of nursing, must typically report these violations to their state’s Board of Nursing.

Infractions are minor offenses, such as speeding tickets, that result in fines but not jail time. Infractions do not generally impact nursing licensure unless there is a significant quantity of them over a short period of time.

Sample Case

An LPN working for a hospice agency was accused of stealing a patient’s pain medications and substituting them with anti-seizure medication. The family asserted the actions of the LPN prolonged the patient’s suffering. The LPN served time in prison for diverting the patient’s medications.[6]

Private Law

Private law, also referred to as civil law, focuses on the rights, responsibilities, and legal relationships between private citizens. Civil law typically involves compensation to the injured party. Unlike criminal law that requires a jury to determine a defendant is guilty beyond reasonable doubt, civil law only requires a certainty of guilt of greater than 50 percent.[7] See Figure 5.2[8] illustrating balancing the evidence to determine the certainty of guilt. Any nurse can be impacted by civil law based on actions occurring in daily nursing practice.

Civil law includes contract law and tort law. Contracts are binding written, verbal, or implied agreements. A tort is an act of commission or omission that gives rise to injury or harm to another and amounts to a civil wrong for which courts impose liability. In the context of torts, "injury" describes the invasion of any legal right, whereas "harm" describes a loss or detriment that an individual suffers.[9]

Two categories of torts affect nursing practice: intentional torts, such as intentionally hitting a person, and unintentional torts (also referred to as negligent torts), such as making an error by failing to follow agency policy.

Intentional Torts

Intentional torts are wrongs that the defendant knew (or should have known) would be caused by their actions. Examples of intentional torts include assault, battery, false imprisonment, slander, libel, and breach of privacy or client confidentiality.

Unintentional Torts

Unintentional torts occur when the defendant's actions or inactions were unreasonably unsafe. Unintentional torts can result from acts of commission (i.e., doing something a reasonable nurse would not have done) or omission (i.e., failing to do something a reasonable nurse would do).[10]

Negligence and malpractice are examples of unintentional torts. Tort law exists to compensate clients injured by negligent practice, provide corrective judgement, and deter negligence with visible consequences of action or inaction.[11],[12] Examples of common torts affecting nursing practice are discussed in further detail in the following subsections. See Table 5.2 for a comparison of public and private law.

Table 5.2 Comparison of Public and Private Law

| Type of Law | Subtypes of Law and Examples |

|---|---|

| Public Law |

|

| Private Law (Civil Law) |

|

Examples of Intentional and Unintentional Torts

Assault and Battery

Assault and battery are intentional torts. Assault is defined as intentionally putting another person in reasonable apprehension of an imminent harmful or offensive contact.[13] Battery is defined as intentional causation of harmful or offensive contact with another person without that person's consent.[14] Physical harm does not need to occur to be charged with assault or battery. Battery convictions are often misdemeanors but can be felonies if serious bodily harm occurs. To avoid the risk of being charged with assault or battery, nurses must obtain consent from clients to provide hands-on care.

False Imprisonment

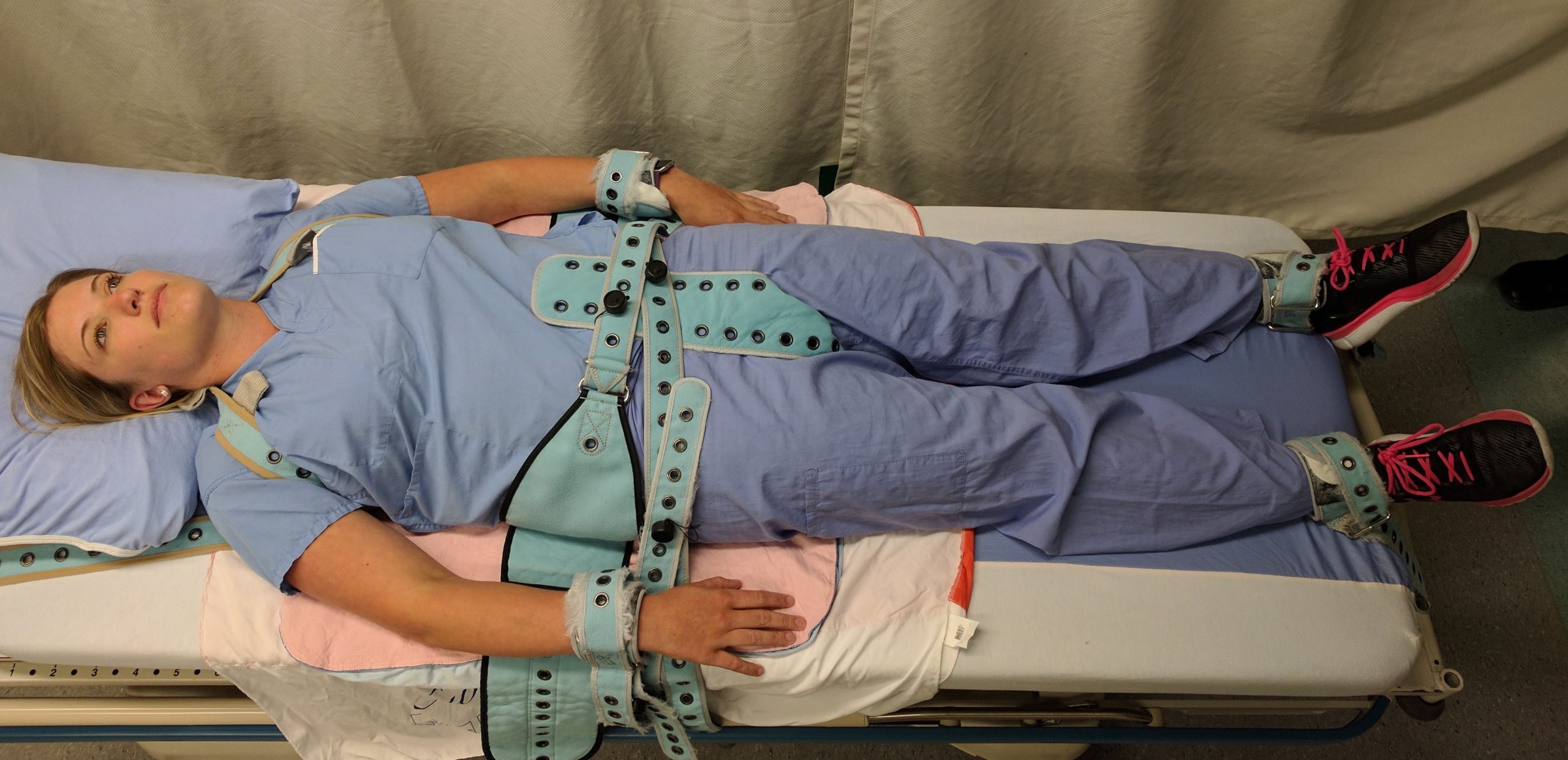

False imprisonment is an intentional tort. False imprisonment is defined as an act of restraining another person and causing that person to be confined in a bounded area.[15] In nursing practice, restraints can be physical, chemical, or verbal. Nurses must strictly follow agency policies related to the use of restraints. Physical restraints typically require a provider order and documentation according to strict guidelines within specific time frames. See Figure 5.3[16] for an image of a simulated client in full physical medical restraints.

Chemical restraints include administering medications such as benzodiazepines and require clear documentation supporting their use. Verbal threats to keep an individual in an inpatient environment can also qualify as false imprisonment and should be avoided.

Breach of Privacy and Confidentiality

Breaching privacy and confidentiality are intentional torts. Confidentiality is the right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information, referred to as protected health information (PHI), kept private. Protected Health Information (PHI) is defined as individually identifiable health information, including demographic data, that relates to the individual’s past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition[17]; the provision of health care to the individual; and the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual.

This right is protected by federal regulations called the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA was enacted in 1996 and was prompted by the need to ensure privacy and protection of personal health records and data in an environment of electronic medical records and third-party insurance payers. There are two main sections of HIPAA law: the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule. The Privacy Rule addresses the use and disclosure of individuals’ health information. The Security Rule sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information. HIPAA regulations extend beyond medical records and apply to client information shared with others. Therefore, all types of client information should be shared only with health care team members who are actively providing care to them.[18],[19]

HIPAA violations may result in fines from $100 for an individual violation to $1.5 million for organizational violations. Criminal penalties, including jail time of up to ten years, may be imposed for violations involving the use of PHI for personal gain or malicious intent. Nursing students are also required to adhere to HIPAA guidelines from the moment they enter the clinical setting or risk being disciplined or expelled by their nursing program.

Sample Case

An RN accessed a patient’s medical records, as well as the records of the newborn son, although she was not assigned to their care because she believed the newborn was her biological grandchild. Although the chart was accessed for less than five seconds, it was unauthorized. The nurse was publicly reprimanded by the state’s Board of Nursing, and her multistate licensure privileges were revoked. Expenses to defend the nurse exceeded $2,800.[20]

Read more about the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Slander and Libel

Slander and libel are intentional torts. Defamation of character occurs when an individual makes negative, malicious, and false remarks about another person to damage their reputation. Slander is spoken defamation and libel is written defamation. Nurses must take care to communicate and document facts regarding patient care without defamation in their oral and written communications with clients and coworkers.

Fraud

Fraud is an intentional tort occurring when an individual is deceived for personal gain. An example of fraud is financial exploitation perpetrated by individuals who are in positions of trust.[21],[22] A nurse may be charged with fraud for documenting interventions not performed or altering documentation to cover up an error. Fraud can result in civil and criminal charges and also suspension or revocation of a nurse’s license.

Negligence and Malpractice

Negligence and malpractice are types of unintentional torts. Negligence is the failure to exercise the ordinary care a reasonable person would use in similar circumstances. Wisconsin civil jury instruction states, “A person is not using ordinary care and is negligent, if the person, without intending to do harm, does something (or fails to do something) that a reasonable person would recognize as creating an unreasonable risk of injury or damage to a person or property.”[23] Malpractice is a specific term used for negligence committed by a professional with a license. See Figure 5.4[24] for an illustration related to malpractice.

Elements of Nursing Malpractice

Nurses and nursing students don’t often get sued for malpractice, but when they do, it is important to understand the elements required to prove malpractice. All the following elements must be established in a court of law to prove malpractice[25]:

- Duty: A nurse-client relationship exists.

- Breach: The standard of care was not met and harm was a foreseeable consequence of the action or inaction.

- Cause: Injury was caused by the nurse’s breach.

- Harm: Injury resulted in damages.

Parties bringing a lawsuit must be able to demonstrate their interests were harmed, providing a reason to stand before the court. The person bringing the lawsuit is called the plaintiff. The parties named in the lawsuit are called defendants. Most malpractice lawsuits name physicians or hospitals, although nurses can be individually named. Employers can be held liable for the actions of their employees.[26]

Malpractice lawsuits are concerned with the legal obligations nurses have to their patients to adhere to current standards of practice. These legal obligations are referred to as the duty of reasonable care. Nurses are required to adhere to standards of practice when providing care to patients they have been assigned. This includes following organizational policies and procedures, maintaining clinical competency, and confining their activities to the authorized scope of practice as defined by their state’s Nurse Practice Act. Nurses also have a legal duty to be physically, mentally, and morally fit for practice. When nurses do not meet these professional obligations, they are said to have breached their duties to patients.[27]

Duty

In the work environment, a duty is created when the nurse accepts responsibility for a patient and establishes a nurse-patient relationship. This generally occurs during inpatient care upon acceptance of a handoff report from another nurse. Outside the work environment, a nurse-patient relationship is created when the nurse volunteers services. Some states have statutes requiring notification of authorities (also referred to as mandatory reporting) or summoning assistance.[28]

Good Samaritan Law

The Good Samaritan Law provides protections against negligence claims to individuals who render aid to people experiencing medical emergencies outside of clinical environments. All 50 states in the United States have a version of a Good Samaritan Law. See Figure 5.5[29] for historical artwork depicting a Good Samaritan. Differences exist in state laws regarding protection of bystanders who provide aid. For example, in Wisconsin, the law states, "Any person who renders emergency care at the scene of any emergency or accident in good faith is immune from civil liability for the person’s acts or omissions in rendering such emergency care."[30] There are a few states that require some emergency bystander action, so nurses should review the law in states they are visiting. It is also important to keep in mind that although anyone can file a lawsuit against someone who provides bystander aid, the Good Samaritan laws typically negate any penalty to the person rendering aid.