18.1 Administration of Parenteral Medications Introduction

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Learning Objectives

- Safely administer medication via the intradermal, subcutaneous, and intramuscular routes

- Maintain aseptic technique

- Select appropriate equipment

- Calculate correct amount of medication to administer

- Correctly select site using anatomical landmarks

- Modify procedure to reflect variations across the life span

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

Administering medication by the parenteral route is defined as medications placed into the tissues and the circulatory system by injection. There are several reasons why medications may be prescribed via the parenteral route. Medications administered parenterally are absorbed more quickly compared to oral ingestion, meaning they have a faster onset of action. Because they do not undergo digestive processes in the gastrointestinal tract, they are metabolized differently, resulting in a stronger effect than oral medications. The parenteral route may also be prescribed when patients are nauseated or unable to swallow.

Although an injectable medication has many benefits, there are additional safety precautions the nurse must take during administration because an injection is considered an invasive procedure. Injections cause a break in the protective barrier of the skin, and some are administered directly into the bloodstream so there is increased risk of infection and rapid development of life-threatening adverse reactions.

There are four potential routes of parenteral injections, including intradermal (ID), subcutaneous (Subcut), intramuscular (IM), and intravenous (IV). An intradermal injection is administered in the dermis just below the epidermis. A subcutaneous injection is administered into adipose tissue under the dermis. An intramuscular injection is administered into a muscle. Intravenous medications are injected directly into the bloodstream. Administering medication via the intravenous (IV) route is discussed in the “IV Therapy Management” chapter. This chapter will describe several evidence-based guidelines for safe administration of parenteral medications.

Evaluating the Effects

The nurse is responsible for assessing the client, monitoring lab values, and recognizing side effects and/or adverse effects of medications. Drug dosages should be verified to ensure all are within recommended safe ranges according to the client's current status, as well as for their potency.

Potency refers to the amount of the drug required to produce the desired effect. A drug that is highly potent may require only a minimal dose to produce a desired therapeutic effect, whereas a drug that has low potency may need to be given at much higher concentrations to produce the same effect. Consider the example of opioid versus nonopioid medications for pain control. Opioid medications often have a much higher potency in smaller doses to produce pain relief; therefore, the overall dose required to produce a therapeutic effect may be much less than that for other analgesics.

The nurse preparing to administer medications must also be cognizant of drug selectivity and monitor for potential side effects and adverse effects. Selectivity refers to the separation between the desired and undesired effects of a drug. Drugs that are selective will search out target sites to create a specific drug action, whereas nonselective drugs may impact many other types of cells and tissues, thus increasing the risk for unintended side effects and/or adverse effects. For example, in Chapter 4 selective and nonselective beta-blockers will be discussed. Selective beta-1 blockers search out specific receptors on the heart to create their effect, whereas nonselective beta-blockers may affect receptors in the lungs in addition to those in the heart, causing potential respiratory side effects like a cough.

A side effect occurs when the drug produces effects other than the intended effect. A side effect, although often unintended, is generally anticipated by the provider and is a known potential consequence of the medication therapy. Examples of common side effects are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and drowsiness. In some situations, however, side effects may have a beneficial impact. For example, a side effect of hydrocodone is drowsiness. A client who is having difficulty sleeping due to pain and takes hydrocodone at bedtime may find the drowsiness beneficial in helping them fall asleep.

Conversely, unanticipated effects can occur from medications that are harmful to the client. These harmful occurrences are known as adverse effects. Adverse effects are relatively unpredictable, severe, and are reason to discontinue the medication.[1] For example, an adverse effect of ciprofloxacin is tendon rupture. Adverse effects should be reported to the pharmacy and tracked as a client safety concern according to agency policy.

Now that the concepts of dose-response, onset, peak, and duration have been discussed, it is important to understand the therapeutic window and therapeutic index.

Therapeutic Window

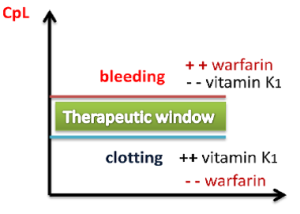

For every drug, there exists a dose that is minimally effective (the Effective Concentration) and another dose that is toxic (the Toxic Concentration). Between these doses is the therapeutic window, where the safest and most effective treatment will occur. For example, see Figure 1.9[2] for an illustration of the therapeutic window for warfarin, a medication used to prevent blood clotting. Too much warfarin administered causes bleeding and vitamin K is required as an antidote. Conversely, not enough warfarin administered for a client's condition can cause clotting. Think of the therapeutic window (the green area on the graph) as the "perfect dose," where clotting is prevented and yet bleeding does not occur.

The effect of warfarin is monitored using a blood test called international normalized ration (INR). For clients receiving warfarin, nurses vigilantly monitor their INR levels to ensure the dosage appropriately reaches their therapeutic window and does not place them at risk for bleeding or clotting.

Peak and Trough Levels

Now let's apply the idea of therapeutic window to the administration of medications requiring the monitoring of peak and trough levels, which is commonly required in the administration of specific IV antibiotics. The dosage of these medications is titrated, meaning adjusted for safety, to achieve a desired therapeutic effect for the client. Titration is accomplished by closely monitoring the peak and trough levels of the medication. A drug is said to be within the "therapeutic window" when the serum blood levels of an active drug remain consistently above the level of effective concentration (so that the medication is achieving its desired therapeutic effect) and consistently below the toxic level (so that no toxic effects are occurring).

A peak drug level is drawn after the medication is administered and is known to be at the highest level in the bloodstream. A trough level is drawn when the drug is at its lowest in the bloodstream, right before the next scheduled dose is given. Medications have a predicted reference range of normal values for peak and trough levels. These numbers assist the pharmacist and provider in gauging how the body is metabolizing, protein-binding, and excreting the drug and are used to adjust the prescribed dose to keep the medication within the therapeutic window. When administering IV medications that require peak or trough levels, it is vital for the nurse to plan the administration of the medication according to the timing of these blood draws.[3]

Therapeutic Index

The therapeutic index is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug. It is a comparison of the amount of drug that produces a therapeutic effect versus the amount of drug that produces a toxic effect.

- A large (or high) therapeutic index number means there is a wide therapeutic window between the effective concentration and the toxic concentration of a medication, so the drug is relatively safe.

- A small (or low) therapeutic index number means there is a narrow therapeutic window between the effective concentration and the toxic concentration. A drug with a narrow therapeutic range (i.e., having little difference between toxic and therapeutic doses) often has the dosage titrated according to measurements of the actual blood levels achieved in the person taking it.

For example, phenytoin has a narrow therapeutic index between the effective and toxic concentrations. Clients who start taking phenytoin to control seizures have frequent peak and trough drug levels to ensure they achieve steady state with a therapeutic dose to prevent seizures without reaching toxic levels.

Critical Thinking Activity 1.10

Mr. Parker has been receiving gentamicin 80 mg IV three times daily to treat his infective endocarditis. He has his gentamicin level checked one hour after the end of his previous gentamicin infusion was completed. The result is 30 mcg/mL. Access the information below to determine the nurse's course of action.

View information on therapeutic drug levels.

(After accessing the information, be sure to select “click to keep reading” in order to view drugs that are commonly checked, their target levels, and what abnormal results mean.)

Based on the results in the above client scenario, what action will the nurse take based on the result of the gentamicin level of 30 mcg/mL?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the "Answer Key" section at the end of the book.

Evaluating the Effects

The nurse is responsible for assessing the client, monitoring lab values, and recognizing side effects and/or adverse effects of medications. Drug dosages should be verified to ensure all are within recommended safe ranges according to the client's current status, as well as for their potency.

Potency refers to the amount of the drug required to produce the desired effect. A drug that is highly potent may require only a minimal dose to produce a desired therapeutic effect, whereas a drug that has low potency may need to be given at much higher concentrations to produce the same effect. Consider the example of opioid versus nonopioid medications for pain control. Opioid medications often have a much higher potency in smaller doses to produce pain relief; therefore, the overall dose required to produce a therapeutic effect may be much less than that for other analgesics.

The nurse preparing to administer medications must also be cognizant of drug selectivity and monitor for potential side effects and adverse effects. Selectivity refers to the separation between the desired and undesired effects of a drug. Drugs that are selective will search out target sites to create a specific drug action, whereas nonselective drugs may impact many other types of cells and tissues, thus increasing the risk for unintended side effects and/or adverse effects. For example, in Chapter 4 selective and nonselective beta-blockers will be discussed. Selective beta-1 blockers search out specific receptors on the heart to create their effect, whereas nonselective beta-blockers may affect receptors in the lungs in addition to those in the heart, causing potential respiratory side effects like a cough.

A side effect occurs when the drug produces effects other than the intended effect. A side effect, although often unintended, is generally anticipated by the provider and is a known potential consequence of the medication therapy. Examples of common side effects are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and drowsiness. In some situations, however, side effects may have a beneficial impact. For example, a side effect of hydrocodone is drowsiness. A client who is having difficulty sleeping due to pain and takes hydrocodone at bedtime may find the drowsiness beneficial in helping them fall asleep.

Conversely, unanticipated effects can occur from medications that are harmful to the client. These harmful occurrences are known as adverse effects. Adverse effects are relatively unpredictable, severe, and are reason to discontinue the medication.[4] For example, an adverse effect of ciprofloxacin is tendon rupture. Adverse effects should be reported to the pharmacy and tracked as a client safety concern according to agency policy.