10.3 Respiratory Assessment

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

With an understanding of the basic structures and primary functions of the respiratory system, the nurse collects subjective and objective data to perform a focused respiratory assessment.

Subjective Assessment

Collect data using interview questions, paying particular attention to what the patient is reporting. The interview should include questions regarding any current and past history of respiratory health conditions or illnesses, medications, and reported symptoms. Consider the patient’s age, gender, family history, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health practices when gathering subjective data. The information discovered during the interview process guides the physical exam and subsequent patient education. See Table 10.3a for sample interview questions to use during a focused respiratory assessment.[1]

Table 10.3a Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of the Respiratory System

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a respiratory condition, such as asthma, COPD, pneumonia, or allergies?

Do you use oxygen or peak flow meter? Do you use home respiratory equipment like CPAP, BiPAP, or nebulizer devices? |

Please describe the conditions and treatments. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements for respiratory concerns? | Please identify what you are taking and the purpose of each. |

| Have you had any feelings of breathlessness

(dyspnea)? |

Note: If the shortness of breath is severe or associated with chest pain, discontinue the interview and obtain emergency assistance.

Are you having any shortness of breath now? If yes, please rate the shortness of breath from 0-10 with “0” being none and “10” being severe? Does anything bring on the shortness of breath (such as activity, animals, food, or dust)? If activity causes the shortness of breath, how much exertion is required to bring on the shortness of breath? When did the shortness of breath start? Is the shortness of breath associated with chest pain or discomfort? How long does the shortness of breath last? What makes the shortness of breath go away? Is the shortness of breath related to a position, like lying down? Do you sleep in a recliner or upright in bed? Do you wake up at night feeling short of breath? How many pillows do you sleep on? How does the shortness of breath affect your daily activities? |

| Do you have a cough? | When you cough, do you bring up anything? What color is the phlegm?

Do you cough up any blood (hemoptysis)? Do you have any associated symptoms with the cough such as fever, chills, or night sweats? How long have you had the cough? Does anything bring on the cough (such as activity, dust, animals, or change in position)? What have you used to treat the cough? Has it been effective? |

| Do you smoke or vape? | What products do you smoke/vape? If cigarettes are smoked, how many packs a day do you smoke?

How long have you smoked/vaped? Have you ever tried to quit smoking/vaping? What strategies gave you the best success? Are you interested in quitting smoking/vaping? If the patient is ready to quit, the five successful interventions are the “5 A’s”: Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange. Ask – Identify and document smoking status for every patient at every visit. Advise – In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every user to quit. Assess – Is the user willing to make a quitting attempt at this time? Assist – For the patient willing to make a quitting attempt, use counseling and pharmacotherapy to help them quit. Arrange – Schedule follow-up contact, in person or by telephone, preferably within the first week after the quit date.[2] |

Life Span Considerations

Depending on the age and capability of the child, subjective data may also need to be retrieved from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Pediatric

- Is your child up-to-date with recommended immunizations?

- Is your child experiencing any cold symptoms (such as runny nose, cough, or nasal congestion)?

- How is your child’s appetite? Is there any decrease or change recently in appetite or wet diapers?

- Does your child have any hospitalization history related to respiratory illness?

- Did your child have any history of frequent ear infections as an infant?

Older Adult

- Have you noticed a change in your breathing?

- Do you get short of breath with activities that you did not before?

- Can you describe your energy level? Is there any change from previous?

Objective Assessment

A focused respiratory objective assessment includes interpretation of vital signs; inspection of the patient’s breathing pattern, skin color, and respiratory status; palpation to identify abnormalities; and auscultation of lung sounds using a stethoscope. For more information regarding interpreting vital signs, see the “General Survey” chapter. The nurse must have an understanding of what is expected for the patient’s age, gender, development, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health condition to determine the meaning of the data that is being collected.

Evaluate Vital Signs

The vital signs may be taken by the nurse or delegated to unlicensed assistive personnel such as a nursing assistant or medical assistant. Evaluate the respiratory rate and pulse oximetry readings to verify the patient is stable before proceeding with the physical exam. The normal range of a respiratory rate for an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute at rest, and the normal range for oxygen saturation of the blood is 94–98% (SpO₂).[3] Bradypnea is less than 12 breaths per minute, and tachypnea is greater than 20 breaths per minute.

Inspection

Inspection during a focused respiratory assessment includes observation of level of consciousness, breathing rate, pattern and effort, skin color, chest configuration, and symmetry of expansion.

- Assess the level of consciousness. The patient should be alert and cooperative. Hypoxemia (low blood levels of oxygen) or hypercapnia (high blood levels of carbon dioxide) can cause a decreased level of consciousness, irritability, anxiousness, restlessness, or confusion.

- Obtain the respiratory rate over a full minute. The normal range for the respiratory rate of an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute.

- Observe the breathing pattern, including the rhythm, effort, and use of accessory muscles. Breathing effort should be nonlabored and in a regular rhythm. Observe the depth of respiration and note if the respiration is shallow or deep. Pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring, audible breathing, intercostal retractions, anxiety, and use of accessory muscles are signs of respiratory difficulty. Inspiration should last half as long as expiration unless the patient is active, in which case the inspiration-expiration ratio increases to 1:1.

- Observe the pattern of expiration and patient position. Patients who experience difficulty expelling air, such as those with emphysema, may have prolonged expiration cycles. Some patients may experience difficulty with breathing specifically when lying down. This symptom is known as orthopnea. Additionally, patients who are experiencing significant breathing difficulty may experience most relief while in a “tripod” position. This can be achieved by having the patient sit at the side of the bed with legs dangling toward the floor. The patient can then rest their arms on an overbed table to allow for maximum lung expansion. This position mimics the same position you might take at the end of running a race when you lean over and place your hands on your knees to “catch your breath.”

- Observe the patient’s color in their lips, face, hands, and feet. Patients with light skin tones should be pink in color. For those with darker skin tones, assess for pallor on the palms, conjunctivae, or inner aspect of the lower lip. Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds, which may indicate decreased perfusion and oxygenation. Pallor is the loss of color, or paleness of the skin or mucous membranes and usually the result of reduced blood flow, oxygenation, or decreased number of red blood cells.

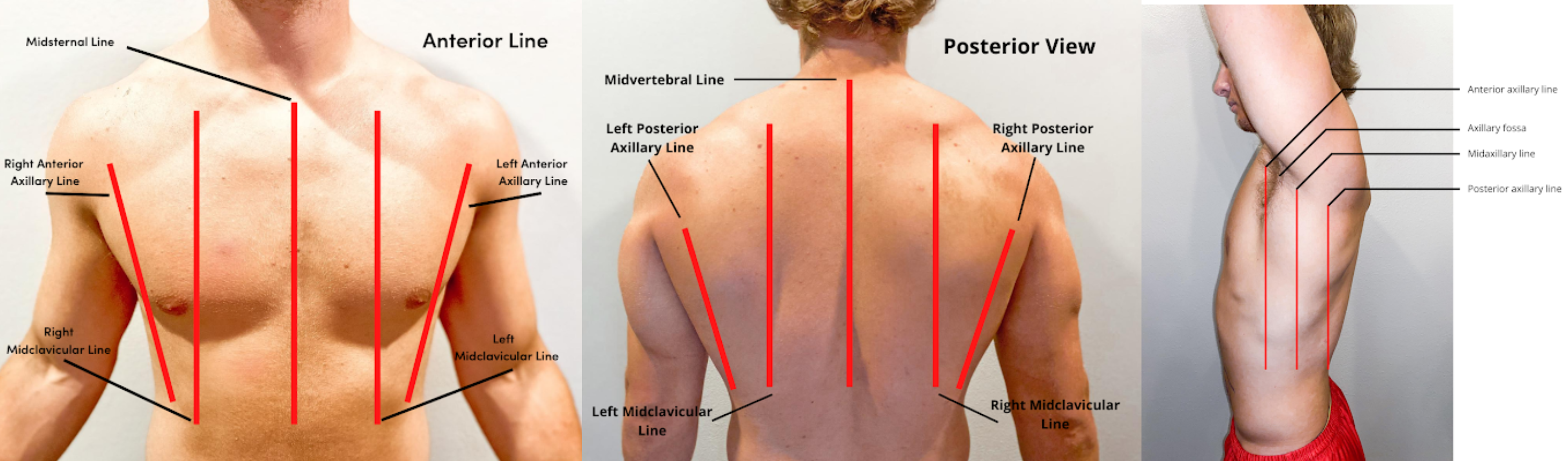

- Inspect the chest for symmetry and configuration. The trachea should be midline, and the clavicles should be symmetrical. See Figure 10.2[4] for visual landmarks when inspecting the thorax anteriorly, posteriorly, and laterally. Note the location of the ribs, sternum, clavicle, and scapula, as well as the underlying lobes of the lungs.

- Chest movement should be symmetrical on inspiration and expiration.

- Observe the anterior-posterior diameter of the patient’s chest and compare to the transverse diameter. The expected anteroposterior-transverse ratio should be 1:2. A patient with a 1:1 ratio is described as barrel-chested. This ratio is often seen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to hyperinflation of the lungs. See Figure 10.3[5] for an image of a patient with a barrel chest.

- Older patients may have changes in their anatomy, such as kyphosis, an outward curvature of the spine.

- Inspect the fingers for clubbing if the patient has a history of chronic respiratory disease. Clubbing is a bulbous enlargement of the tips of the fingers due to chronic hypoxia. See Figure 10.4[6] for an image of clubbing.

Palpation

- Palpation of the chest may be performed to investigate for areas of abnormality related to injury or procedural complications. For example, if a patient has a chest tube or has recently had one removed, the nurse may palpate near the tube insertion site to assess for areas of air leak or crepitus. Crepitus feels like a popping or crackling sensation when the skin is palpated and is a sign of air trapped under the subcutaneous tissues. If palpating the chest, use light pressure with the fingertips to examine the anterior and posterior chest wall. Chest palpation may be performed to assess specifically for growths, masses, crepitus, pain, or tenderness.

- Confirm symmetric chest expansion by placing your hands on the anterior or posterior chest at the same level, with thumbs over the sternum anteriorly or the spine posteriorly. As the patient inhales, your thumbs should move apart symmetrically. Unequal expansion can occur with pneumonia, thoracic trauma, such as fractured ribs, or pneumothorax.

Auscultation

Using the diaphragm of the stethoscope, listen to the movement of air through the airways during inspiration and expiration. Instruct the patient to take deep breaths through their mouth. Listen through the entire respiratory cycle because different sounds may be heard on inspiration and expiration. Allow the patient to rest between respiratory cycles, if needed, to avoid fatigue with deep breathing during auscultation. As you move across the different lung fields, the sounds produced by airflow vary depending on the area you are auscultating because the size of the airways change.

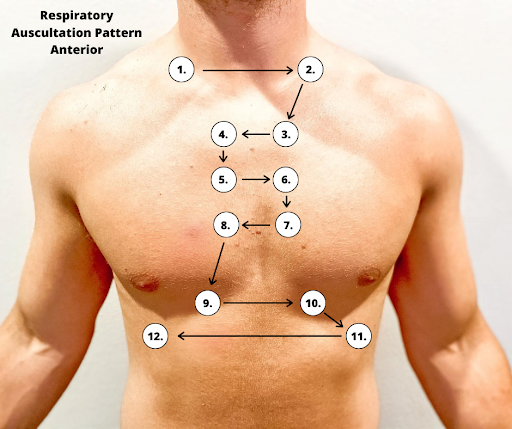

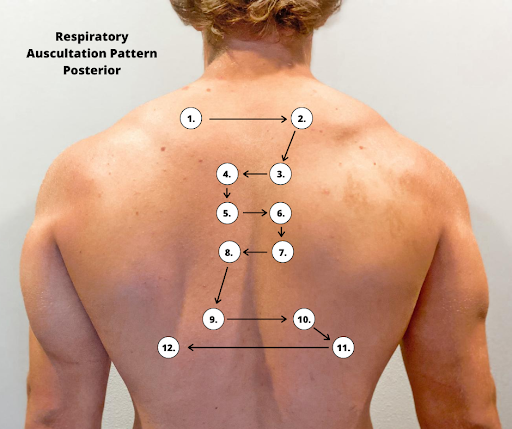

Correct placement of the stethoscope during auscultation of lung sounds is important to obtain a quality assessment. The stethoscope should not be placed over clothes or hair because these may create inaccurate sounds from friction. The best position to listen to lung sounds is with the patient sitting upright; however, if the patient is acutely ill or unable to sit upright, turn them side to side in a lying position. Avoid listening over bones, such as the scapulae or clavicles or over the female breasts to ensure you are hearing adequate sound transmission. Listen to sounds from side to side rather than down one side and then down the other side. This side-to-side pattern allows you to compare sounds in symmetrical lung fields. See Figures 10.5[7] and 10.6[8] for landmarks of stethoscope placement over the anterior and posterior chest wall.

Expected Breath Sounds

It is important upon auscultation to have awareness of expected breath sounds in various anatomical locations.

- Bronchial breath sounds are heard over the trachea and larynx and are high-pitched and loud.

- Bronchovesicular sounds are medium-pitched and heard over the major bronchi.

- Vesicular breath sounds are heard over the lung surfaces, are lower-pitched, and often described as soft, rustling sounds.

Adventitious Lung Sounds

Adventitious lung sounds are sounds heard in addition to normal breath sounds. They most often indicate an airway problem or disease, such as accumulation of mucus or fluids in the airways, obstruction, inflammation, or infection. These sounds include rales/crackles, rhonchi/wheezes, stridor, and pleural rub:

- Coarse crackles, also called rhonchi, are low-pitched, loud, continuous sounds frequently heard on expiration. They are a sign of turbulent airflow through secretions in the large airways.

Rhonchi Lung Sounds on YouTube [9]

- Fine crackles, also called rales, are popping or crackling sounds heard on inspiration. They occur in association with conditions that cause fluid to accumulate within the alveolar and interstitial spaces, such as heart failure or pneumonia. Fine crackles are soft, high-pitched, and very brief. For this reason, it is essential to listen to lung sounds with the stethoscope placed on the patient’s skin and not over their clothing or hospital gown. The sound is similar to that produced by rubbing strands of hair together close to your ear.

- Wheezes are whistling-type noises produced during expiration (and sometimes inspiration) when air is forced through airways narrowed by bronchoconstriction or associated mucosal edema. For example, patients with asthma commonly have wheezing.

- Stridor is heard only on inspiration. It is associated with mechanical obstruction at the level of the trachea/upper airway.

- Pleural rub may be heard on either inspiration or expiration and sounds like the rubbing together of leather. A pleural rub is heard when there is inflammation of the lung pleura, resulting in friction as the surfaces rub against each other.[10]

Life Span Considerations

Children

There are various respiratory assessment considerations that should be noted with assessment of children.

- The respiratory rate in children less than 12 months of age can range from 30-60 breaths per minute, depending on whether the infant is asleep or active.

- Infants have irregular or periodic newborn breathing in the first few weeks of life; therefore, it is important to count the respirations for a full minute. During this time, you may notice periods of apnea lasting up to 10 seconds. This is not abnormal unless the infant is showing other signs of distress. Signs of respiratory distress in infants and children include nasal flaring and sternal or intercostal retractions.

- Up to three months of age, infants are considered “obligate” nose-breathers, meaning their breathing is primarily through the nose.

- The anteroposterior-transverse ratio is typically 1:1 until the thoracic muscles are fully developed around six years of age.

Older Adults

As the adult person ages, the cartilage and muscle support of the thorax becomes weakened and less flexible, resulting in a decrease in chest expansion. Older adults may also have weakened respiratory muscles, and breathing may become shallower. The anteroposterior-transverse ratio may be 1:1 if there is significant curvature of the spine (kyphosis).

Percussion

Percussion is an advanced respiratory assessment technique that is used by advanced practice nurses and other health care providers to gather additional data in the underlying lung tissue. By striking the fingers of one hand over the fingers of the other hand, a sound is produced over the lung fields that helps determine if fluid is present. Dull sounds are heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis, whereas clear, low-pitched, hollow sounds are heard in normal lung tissue.

![]()

- Because infants breathe primarily through the nose, nasal congestion can limit the amount of air getting into the lungs.

- Attempt to assess an infant’s respiratory rate while the infant is at rest and content rather than when the infant is crying. Counting respirations by observing abdominal breathing movements may be easier for the novice nurse than counting breath sounds, as it can be difficult to differentiate lung and heart sounds when auscultating newborns.

- Auscultation of lungs during crying is not a problem. It will enhance breath sounds.

- The older patient may have a weakening of muscles that support respiration and breathing. Therefore, the patient may report tiring easily during the assessment when taking deep breaths. Break up the assessment by listening to the anterior lung sounds and then the heart sounds and allowing the patient to rest before listening to the posterior lung sounds.

- Patients with end-stage COPD may have diminished lung sounds due to decreased air movement. This abnormal assessment finding may be the patient’s baseline or normal and might also include wheezes and fine crackles as a result of chronic excess secretions and/or bronchoconstriction.[11],[12]

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

See Table 10.3b for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the respiratory system.[13]

Table 10.3b Expected Versus Unexpected Respiratory Assessment Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify provider if a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Work of breathing effortless

Regular breathing pattern Respiratory rate within normal range for age Chest expansion symmetrical Absence of cyanosis or pallor Absence of accessory muscle use, retractions, and/or nasal flaring Anteroposterior: transverse diameter ratio 1:2 |

Labored breathing

Irregular rhythm Increased or decreased respiratory rate Accessory muscle use, pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring (infants), and/or retractions Presence of cyanosis or pallor Asymmetrical chest expansion Clubbing of fingernails |

| Palpation | No pain or tenderness with palpation. Skin warm and dry; no crepitus or masses | Pain or tenderness with palpation, crepitus, palpable masses, or lumps |

| Percussion | Clear, low-pitched, hollow sound in normal lung tissue | Dull sounds heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis |

| Auscultation | Bronchovesicular and vesicular sounds heard over appropriate areas

Absence of adventitious lung sounds |

Diminished lung sounds

Adventitious lung sounds, such as fine crackles/rales, wheezing, stridor, or pleural rub |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Decreased oxygen saturation <92%[14]

Pain Worsening dyspnea Decreased level of consciousness, restlessness, anxiousness, and/or irritability |

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Massey, D., & Meredith, T. (2011). Respiratory assessment 1: Why do it and how to do it? British Journal of Cardiac Nursing, 5(11), 537–541. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2010.5.11.79634 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Pharmacology by Open RN licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Anterior_Chest_Lines.png,” “Posterior_Chest_Lines.png,” and “Lateral_Chest_Lines.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Normal A-P Chest Image.jpg” and “Barrel Chest.jpg” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Clubbing of fingers in IPF.jpg” by IPFeditor is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Anterior Respiratory Auscultation Pattern.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Posterior Respiratory Auscultation Pattern.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2023, April 10). Rhonchi Lung Sounds Nursing NCLEX | Adventitious Lung Sounds. [Video]. YouTube. Used with permission. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/7cIEXfqnYRQ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Honig, E. (1990). An overview of the pulmonary system. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK356/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Hill, B., & Annesley, S. H. (2020). Monitoring respiratory rate in adults. British Journal of Nursing, 29(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2020.29.1.12 ↵

The impairment of near vision and accommodation as the lens of the eye gradually becomes thicker and loses flexibility as a person ages.

Dead tissue that is black.

A condition that occurs when the cardiovascular system cannot adequately return blood and fluid from the extremities to the heart.

A type of wound that is sutured, stapled, glued, or otherwise closed so the wound heals beneath the closure.

A condition that occurs when skin has been exposed to moisture for too long causing it to appear soggy, wrinkled, or whiter than usual.

Altered epidermis and/or dermis.

The process of wound healing when new capillaries begin to develop within the wound 24 hours after injury to bring in more oxygen and nutrients for healing.

Differences in health outcomes resulting from entrenched economic, sociopolitical, or environmental disadvantages.

A safe space for patients to interact with health professionals, without judgment or discrimination, where the patient is free to express their cultural beliefs, values, and identity.

A process where the patient and nurse seek a mutually acceptable way to deal with competing interests of nursing care, prescribed medical care, and the patient’s cultural needs.

Damage to deeper layers of the skin or other integumentary structures. The NANDA-I definition of impaired tissue integrity is, “Damage to the mucous membrane, cornea, integumentary system, muscular fascia, muscle, tendon, bone, cartilage, joint capsule, and/or ligament.”

Separation of the edges of a surgical wound.

Redness and removal of the surface of the topmost layer of skin, often due to maceration or itching.

The first stage of wound healing when clotting factors are released to form clots to stop the bleeding.

Fluid that oozes from a wound.

New connective tissue in a healing wound with new, fragile, thin-walled capillaries.

The development of new epidermis and granulation tissue in a healing wound.

An unplanned event that did not result in a patient injury or illness but had the potential to.

The second stage of healing when vasodilation occurs to move white blood cells into the wound to start cleaning the wound bed.

The third stage of wound healing that begins a few days after injury and includes four processes: epithelialization, angiogenesis, collagen formation, and contraction.

The final stage of wound healing when collagen continues to be created to strengthen the wound and prevent it from reopening.

Swelling.

Redness.