6.5 Assessing Cranial Nerves

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

When performing a comprehensive neurological exam, examiners may assess the functioning of the cranial nerves. When performing these tests, examiners compare responses of opposite sides of the face and neck. Instructions for assessing each cranial nerve are provided below.

Cranial Nerve I – Olfactory

Ask the patient to identify a common odor, such as coffee or peppermint, with their eyes closed. See Figure 6.11[1] for an image of a nurse performing an olfactory assessment.

Cranial Nerve II – Optic

Be sure to provide adequate lighting when performing a vision assessment.

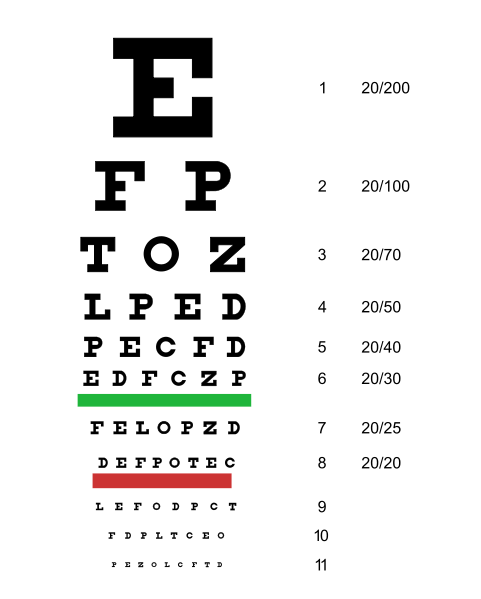

Far vision is tested using the Snellen chart. See Figure 6.12[2] for an image of a Snellen chart. The numerator of the fractions on the chart indicates what the individual can see at 20 feet, and the denominator indicates the distance at which someone with normal vision could see this line. For example, a result of 20/40 indicates this individual can see this line at 20 feet but someone with normal vision could see this line at 40 feet.

Test far vision by asking the patient to stand 20 feet away from a Snellen chart. Ask the patient to cover one eye and read the letters from the lowest line they can see.[3] Record the corresponding result in the furthermost right-hand column, such as 20/30. Repeat with the other eye. If the patient is wearing glasses or contact lens during this assessment, document the results as “corrected vision.” Repeat with each eye, having the patient cover the opposite eye. Alternative charts are available for children or adults who can’t read letters in English.

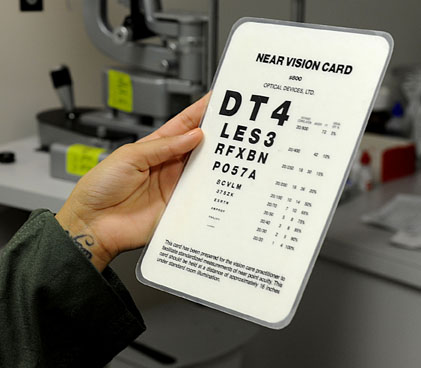

Near vision is assessed by having a patient read from a prepared card from 14 inches away. See Figure 6.13[4] for a card used to assess near vision.

Cranial Nerve III, IV, and VI – Oculomotor, Trochlear, Abducens

Cranial nerve III, IV, and VI (oculomotor, trochlear, abducens nerves) are tested together.

- Test eye movement by using a penlight. Stand 1 foot in front of the patient and ask them to follow the direction of the penlight with only their eyes. At eye level, move the penlight left to right, right to left, up and down, upper right to lower left, and upper left to lower right. Watch for smooth movement of the eyes in all fields. An unexpected finding is involuntary eye movement which may cause the eye to move rapidly from side to side, up and down, or in a circle, and may slightly blur vision referred to as nystagmus.

- Test bilateral pupils to ensure they are equally round and reactive to light and accommodation. Dim the lights of the room before performing this test.

- Pupils should be round and bilaterally equal in size. The diameter of the pupils usually ranges from two to five millimeters. Emergency clinicians often encounter patients with the triad of pinpoint pupils, respiratory depression, and coma related to opioid overuse.

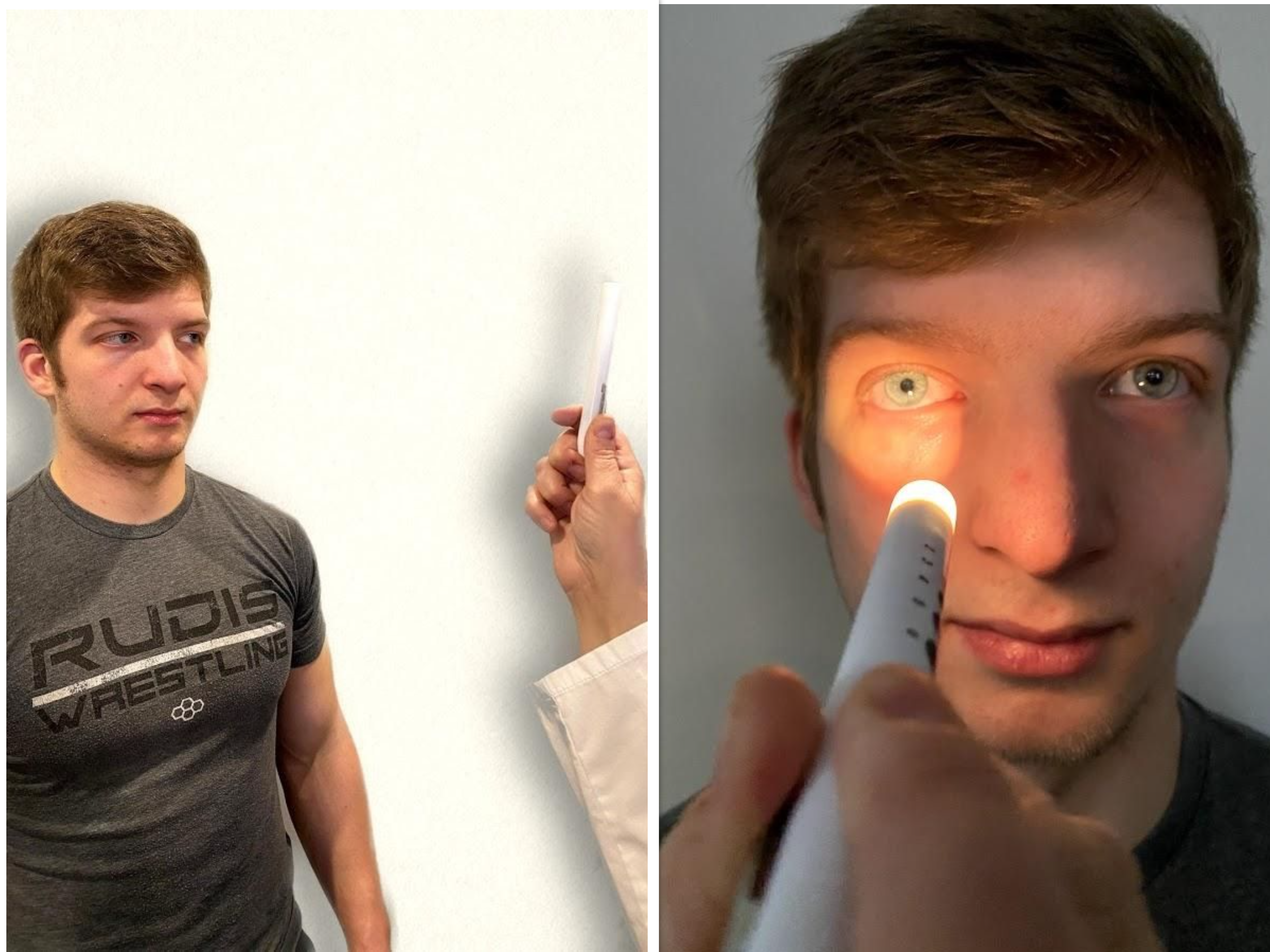

- Test pupillary reaction to light. Using a penlight, approach the patient from the side, and shine the penlight on one pupil. Observe the response of the lighted pupil, which is expected to quickly constrict. The pupil where you shine the light should constrict (direct reaction) and so should the other one (consensual reaction). Repeat by shining the light on the other pupil. Both pupils should react in the same manner to light. See Figure 6.14[5] for an image of a nurse assessing a patient’s pupillary reaction to light. An unexpected finding is when one pupil is larger than the other or one pupil responds more slowly than the other to light, which is often referred to as a “sluggish response.”

- Test eye convergence and accommodation. Recall that accommodation refers to the ability of the eye to adjust from near to far vision, with pupils constricting for near vision and dilating for far vision. Convergence refers to the action of both eyes moving inward as they focus on a close object using near vision. Ask the patient to look at a near object (4-6 inches away from the eyes), and then move the object out to a distance of 12 inches. Pupils should constrict while viewing a near object and then dilate while looking at a distant object, and both eyes should move together. See Figure 6.15[6] for an image of a nurse assessing convergence and accommodation.

- The acronym PERRLA is commonly used in medical documentation and refers to, “pupils are equal, round and reactive to light and accommodation.”

Review for Assessment of the Cardinal Fields of Gaze on YouTube[7]

Visit the National Library of Medicine’s webpage for more details about assessing the Pupillary Light Reflex.

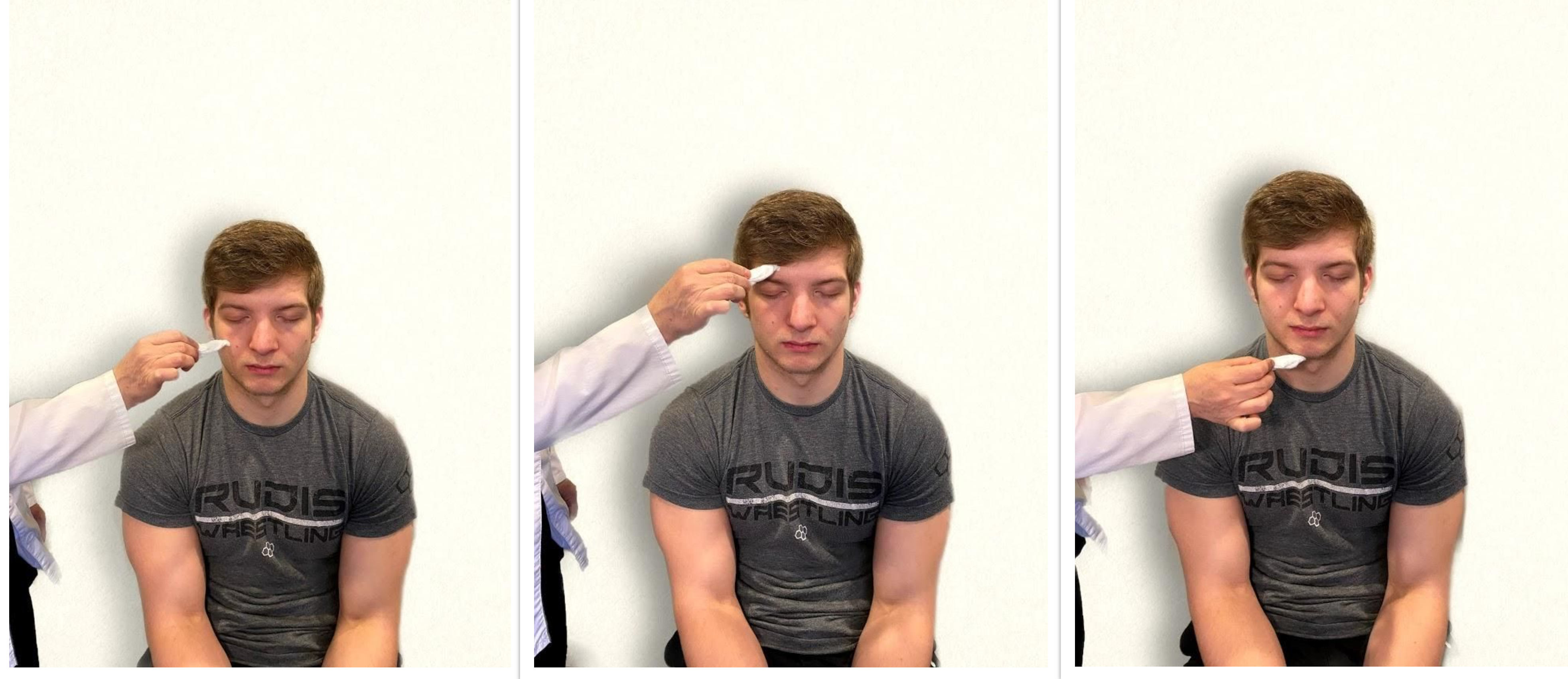

Cranial Nerve V – Trigeminal

- Test sensory function. Ask the patient to close their eyes, and then use a wisp from a cotton ball to lightly touch their face, forehead, and chin. Instruct the patient to say “Now” every time they feel the placement of the cotton wisp. See Figure 6.16[8] for an image of assessing trigeminal sensory function. The expected finding is that the patient will report every instance the cotton wisp is placed. An advanced technique is to assess the corneal reflex in comatose patients by touching the cotton wisp to the cornea of the eye to elicit a blinking response.

- Test motor function. Ask the patient to clench their teeth tightly while bilaterally palpating the temporalis and masseter muscles for strength. Ask the patient to open and close their mouth several times while observing muscle symmetry. See Figure 6.17[9] for an image of assessing trigeminal motor strength. The expected finding is the patient is able to clench their teeth and symmetrically open and close their mouth.

Cranial Nerve VII – Facial Nerve

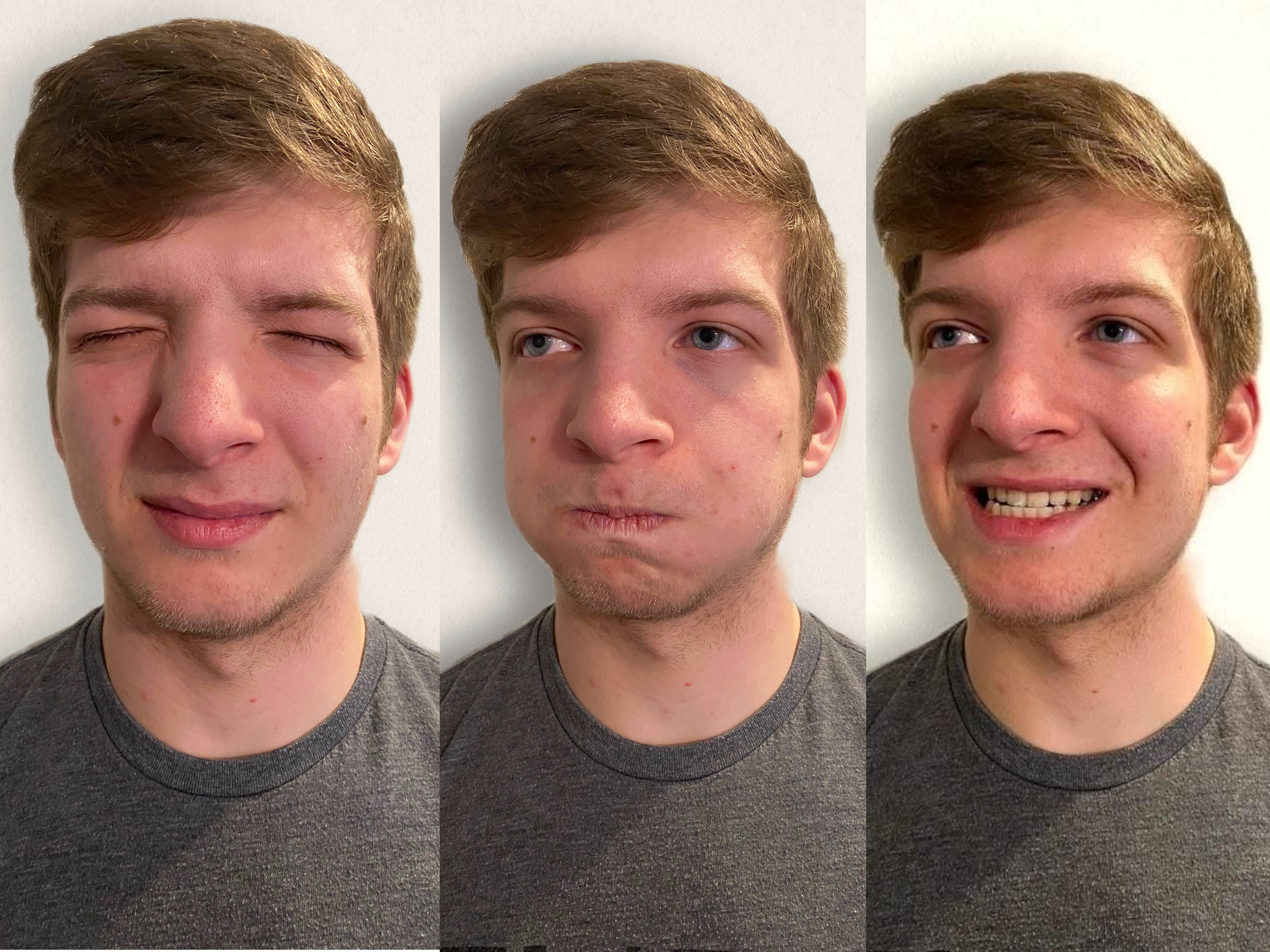

- Test motor function. Ask the patient to smile, show teeth, close both eyes, puff cheeks, frown, and raise eyebrows. Look for symmetry and strength of facial muscles. See Figure 6.18[10] for an image of assessing motor function of the facial nerve.

- Test sensory function. Test the sense of taste by moistening three different cotton applicators with salt, sugar, and lemon. Touch the patient’s anterior tongue with each swab separately, and ask the patient to identify the taste. See Figure 6.19[11] for an image of assessing taste.

Cranial Nerve VIII – Vestibulocochlear

- Test auditory function. Perform the whispered voice test. The whispered voice test is a simple test for detecting hearing impairment if done accurately. See Figure 6.20[12] for an image assessing hearing using the whispered voice test. Complete the following steps to accurately perform this test:

- Stand at arm’s length behind the seated patient to prevent lip reading.

- Each ear is tested individually. The patient should be instructed to occlude the non-test ear with their finger.

- Exhale before whispering and use as quiet a voice as possible.

- Whisper a combination of numbers and letters (for example, 4-K-2), and then ask the patient to repeat the sequence.

- If the patient responds correctly, hearing is considered normal; if the patient responds incorrectly, the test is repeated using a different number/letter combination.

- The patient is considered to have passed the screening test if they repeat at least three out of a possible six numbers or letters correctly.

- The other ear is assessed similarly with a different combination of numbers and letters.

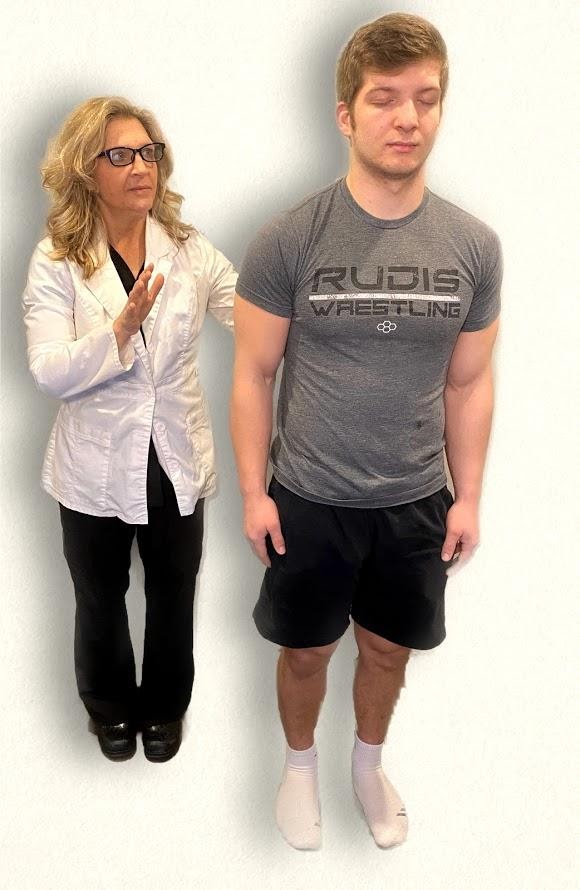

- Test balance. The Romberg test is used to test balance and is also used as a test for driving under the influence of an intoxicant. See Figure 6.21[13] for an image of the Romberg test. Ask the patient to stand with their feet together and eyes closed. Stand nearby and be prepared to assist if the patient begins to fall. It is expected that the patient will maintain balance and stand erect. A positive Romberg test occurs if the patient sways or is unable to maintain balance. The Romberg test is also a test of the body’s sense of positioning (proprioception), which requires healthy functioning of the spinal cord.

Cranial Nerve IX – Glossopharyngeal

Ask the patient to open their mouth and say “Ah” and note symmetry of the upper palate. The uvula and tongue should be in a midline position and the uvula should rise symmetrically when the patient says “Ah.” (See Figure 6.22.[14])

Cranial Nerve X – Vagus

Use a cotton swab or tongue blade to touch the patient’s posterior pharynx and observe for a gag reflex followed by a swallow. The glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves work together for integration of gag and swallowing. See Figure 6.23[15] for an image of assessing the gag reflex.

Cranial Nerve XI – Spinal Accessory

Test the right sternocleidomastoid muscle. Face the patient and place your right palm laterally on the patient’s left cheek. Ask the patient to turn their head to the left while resisting the pressure you are exerting in the opposite direction. At the same time, observe and palpate the right sternocleidomastoid with your left hand. Then reverse the procedure to test the left sternocleidomastoid.

Continue to test the sternocleidomastoid by placing your hand on the patient’s forehead and pushing backward as the patient pushes forward. Observe and palpate the sternocleidomastoid muscles.

Test the trapezius muscle. Ask the patient to face away from you and observe the shoulder contour for hollowing, displacement, or winging of the scapula and observe for drooping of the shoulder. Place your hands on the patient’s shoulders and press down as the patient elevates or shrugs the shoulders and then retracts the shoulders.[16] See Figure 6.24[17] for an image of assessing the trapezius muscle.

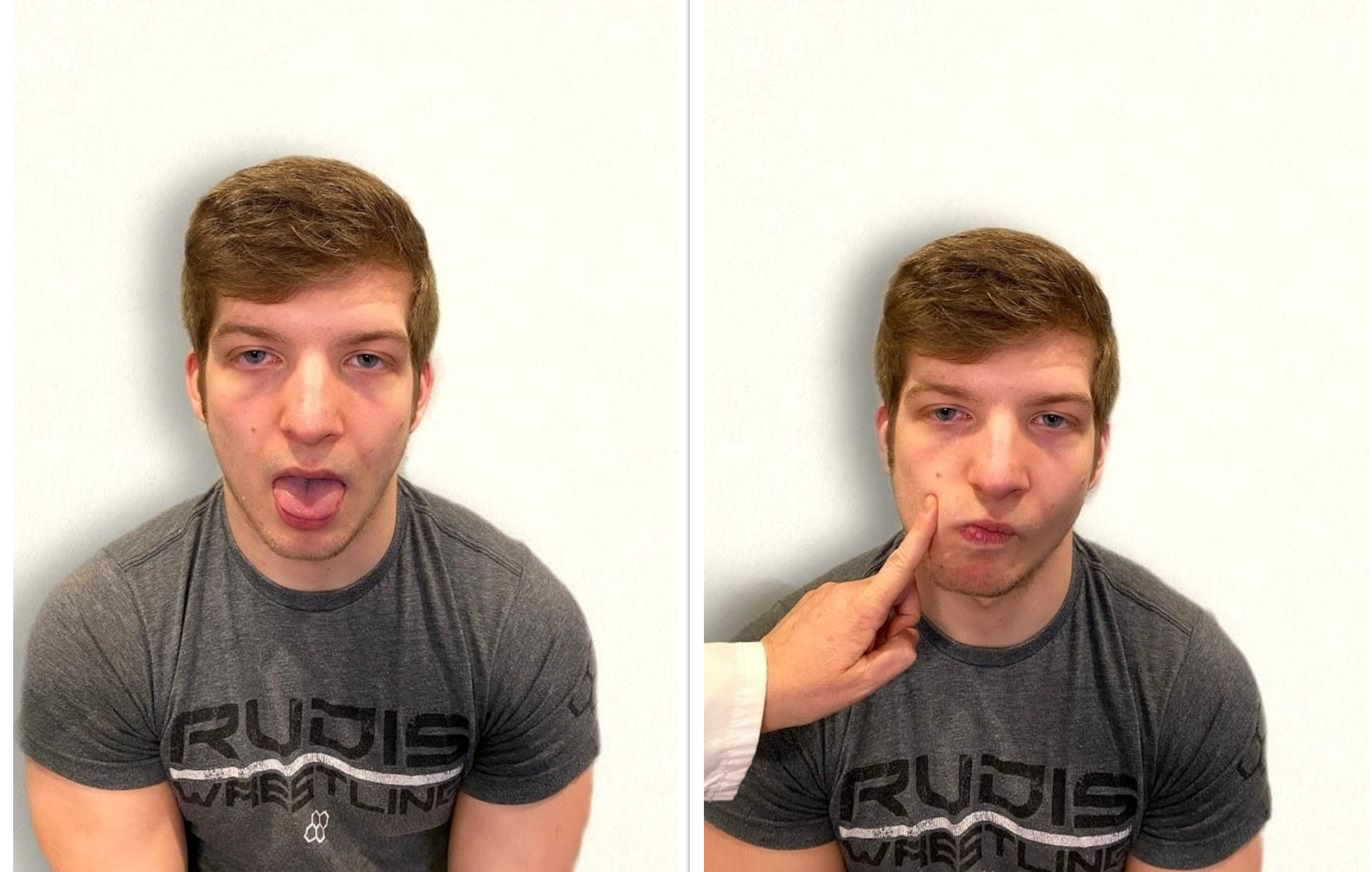

Cranial Nerve XII – Hypoglossal

Ask the patient to protrude the tongue. If there is unilateral weakness present, the tongue will point to the affected side due to unopposed action of the normal muscle. An alternative technique is to ask the patient to press their tongue against their cheek while providing resistance with a finger placed on the outside of the cheek. See Figure 6.25[18] for an image of assessing the hypoglossal nerve.

Review of Cranial Nerve Assessment on YouTube[19]

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

See Table 6.5 for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the cranial nerves.

Table 6.5 Expected Versus Unexpected Findings of an Adult Cranial Nerve Assessment

| Cranial Nerve | Expected Finding | Unexpected Finding (Dysfunction) |

|---|---|---|

| I. Olfactory | Patient is able to describe odor. | Patient has inability to identify odors (anosmia). |

| II. Optic | Patient has 20/20 near and far vision. | Patient has decreased visual acuity and visual fields. |

| III. Oculomotor | Pupils are equal, round, and reactive to light and accommodation. | Patient has different sized or reactive pupils bilaterally. |

| IV. Trochlear | Both eyes move in the direction indicated as they follow the examiner’s penlight. | Patient has inability to look up, down, inward, outward, or diagonally. Ptosis refers to drooping of the eyelid and may be a sign of dysfunction. |

| V. Trigeminal | Patient feels touch on forehead, maxillary, and mandibular areas of face and chews without difficulty. | Patient has weakened muscles responsible for chewing; absent corneal reflex; and decreased sensation of forehead, maxillary, or mandibular area. |

| VI. Abducens | Both eyes move in coordination. | Patient has inability to look side to side (lateral); patient reports diplopia (double vision). |

| VII. Facial | Patient smiles, raises eyebrows, puffs out cheeks, and closes eyes without difficulty; patient can distinguish different tastes. | Patient has decreased ability to taste. Patient has facial paralysis or asymmetry of face such as facial droop. |

| VIII. Vestibulocochlear (Acoustic) | Patient hears whispered words or finger snaps in both ears; patient can walk upright and maintain balance. | Patient has decreased hearing in one or both ears and decreased ability to walk upright or maintain balance. |

| IX. Glossopharyngeal | Gag reflex is present. | Gag reflex is not present; patient has dysphagia. |

| X. Vagus | Patient swallows and speaks without difficulty. | Slurred speech or difficulty swallowing is present. |

| XI. Spinal Accessory | Patient shrugs shoulders and turns head side to side against resistance. | Patient has inability to shrug shoulders or turn head against resistance. |

| XII. Hypoglossal | Tongue is midline and can be moved without difficulty. | Tongue is not midline or is weak. |

- “Cranial Exam Image 11” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Snellen chart.svg” by Jeff Dahl is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Koder-Anne, D., & Klahr, A. (2010). Training nurses in cognitive assessment: Uses and misuses of the mini-mental state examination. Educational Gerontology, 36(10/11), 827–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2010.485027 ↵

- “111012-F-ZT401-067.JPG” by Airman 1st Class Brooke P. Beers for U.S. Air Force is licensed under CC0. Access for free at https://www.pacaf.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/593609/keeping-sight-all-right/ ↵

- “Cranial Exam Image 1” and “Pupillary Exam Image 1” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cranial Nerve Exam 8” and “Cranial Nerve Exam Image 3” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Registered NurseRN.(2018, June 5). Six cardinal fields of gaze nursing | Nystagmus eyes, cranial nerve 3, 4, 6, test [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/lrO4pLB95p0 ↵

- “Neuro Exam Image 28,” “Cranial Exam Image 12,” and “Neuro Exam Image 36” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cranial Exam Image 11,” “Neuro Exam Image 35,” and “Neuro Exam Image 4” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cranial Exam image 15.png,” “Cranial Exam Image 7.png,” and “Cranial Exam Image 10.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Neuro Exam Image 17.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Whisper Test Image 1.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Neuro Exam Image 9.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Oral Exam Image 2.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Oral Exam.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Walker, H. K. Cranial nerve XI: The spinal accessory nerve. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK387/ ↵

- “Neuro Exam image 10” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cranial Nerve Exam Image 9.png” and “Cranial Nerve Exam Image 11.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2018, April 8). Cranial nerve examination nursing | Cranial nerve assessment I-XII (1-12). [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/oZGFrwogx14 ↵

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Scenario A

A nurse is caring for a client who has been hospitalized after undergoing hip-replacement surgery. The client complains of not sleeping well and feels very drowsy during the day.

- What factors are affecting the client’s sleep pattern?

- What assessments should the nurse perform?

- What SMART outcome can be established for this client?

- Outline interventions the nurse can implement to enhance sleep for this client.

- How will the nurse evaluate if the interventions are effective?

Scenario B

A nurse is assigned to work rotating shifts and develops difficulty sleeping.

- Why do rotating shifts affect a person’s sleep pattern?

- What are the symptoms of insomnia?

- Describe healthy sleep habits the nurse can adopt for more restful sleep.

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style bowtie question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[1]

This textbook discusses professional and management concepts related to the role of a registered nurse (RN) as defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA). The ANA publishes two resources that set standards and guide professional nursing practice in the United States: The Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements and Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. The Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements establishes an ethical framework for nursing practice across all roles, levels, and settings and is discussed in greater detail in the “Ethical Practice” chapter of this book. The Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice resource defines the “who, what, where, when, why, and how of nursing” and sets the standards for practice that all registered nurses are expected to perform competently.[2]

The ANA defines the “who” of nursing practice as the nurses who have been educated, titled, and maintain active licensure to practice nursing. The “what” of nursing is the recently revised ANA definition of nursing: “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.”[3] Simply put, nurses treat human responses to health problems and life processes and advocate for the care of others.

Nursing practice occurs “when'' there is a need for nursing knowledge, wisdom, caring, leadership, practice, or education, anytime, anywhere. Nursing practice occurs in any environment “where'' there is a health care consumer in need of care, information, or advocacy. The “why” of nursing practice is described as nursing’s response to the changing needs of society to achieve positive health care consumer outcomes in keeping with nursing’s social contract and obligation to society. The “how” of nursing practice is defined as the ways, means, methods, and manners that nurses use to practice professionally.[4] The “how” of nursing, also referred to as a nurse’s “scope and standards of practice,” is further defined by each state’s Nurse Practice Act; agency policies, procedures, and protocols; and federal regulations and ANA’s Standards of Practice.

State Boards of Nursing and Nurse Practice Acts

RNs must legally follow regulations set by the Nurse Practice Act by the state in which they are caring for patients with their nursing license. The Board of Nursing is the state-specific licensing and regulatory body that sets standards for safe nursing care and issues nursing licenses to qualified candidates based on the Nurse Practice Act. The Nurse Practice Act is enacted by that state’s legislature and defines the scope of nursing practice and establishes regulations for nursing practice within that state. If nurses do not follow the standards and scope of practice set forth by the Nurse Practice Act, they may be disciplined by the Board of Nursing in the form of reprimand, probation, suspension, or revocation of their nursing license. Investigations and discipline actions are reportable among states participating in the Nurse Licensure Compact (that allows nurses to practice across state lines) or when a nurse applies for licensure in a different state. The scope and standards of practice set forth in the Nurse Practice Act can also be used as evidence if a nurse is sued for malpractice.

Find your state's Nurse Practice Act on the National Council of State Board of Nursing (NCSBN) website.

Read more about malpractice and protecting your nursing license in the “Legal Implications” chapter of this book.

Read Wisconsin’s Nurse Practice Act, Standards of Practice for Registered Nurses and Licensed Practical Nurses (Chapter N6) PDF, and Rules of Conduct (Chapter N7) PDF.

Agency Policies, Procedures, and Protocols

In addition to practicing according to the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are employed, nurses must also practice according to agency policies, procedures, and protocols.

A policy is an expected course of action set by an agency. For example, hospitals set a policy requiring a thorough skin assessment to be completed when a patient is admitted and then reassessed and documented daily.

Agencies also establish their own set of procedures. A procedure is the method or defined steps for completing a task. For example, each agency has specific procedural steps for inserting a urinary catheter.

A protocol is a detailed, written plan for performing a regimen of therapy. For example, agencies typically establish a hypoglycemia protocol that nurses can independently and quickly implement when a patient’s blood sugar falls below a specific number without first calling a provider. A hypoglycemia protocol typically includes actions such as providing orange juice and rechecking the blood sugar and then reporting the incident to the provider.

Agency-specific policies, procedures, and protocols supersede the information taught in nursing school, and nurses can be held legally liable if they don’t follow them. It is vital for nurses to review and follow current agency-specific procedures, policies, and protocols while also practicing according to that state's nursing scope of practice. Malpractice cases have occurred when a nurse was asked by their employer to do something outside their legal scope of practice, impacting their nursing license. It is up to you to protect your nursing license and follow the Nurse Practice Act when providing patient care. If you have a concern about an agency’s policy, procedure, or protocol, follow the agency’s chain of command to report your concern.

Federal Regulations

Nursing practice is impacted by regulations enacted by federal agencies. Two examples of federal agencies setting standards of care are The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The Joint Commission accredits and certifies over 20,000 health care organizations in the United States. The Joint Commission’s standards help health care organizations measure, assess, and improve performance on functions that are essential to providing safe, high-quality care. The standards are updated regularly to reflect the rapid advances in health care and address topics such as patient rights and education, infection control, medication management, and prevention of medical errors. The annual National Patient Safety Goals are also set by The Joint Commission after reviewing emerging patient safety issues.[5]

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is an example of another federal agency that establishes regulations affecting nursing care. CMS is a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that administers the Medicare program and works in partnership with state governments to administer Medicaid. The CMS establishes and enforces regulations to protect patient safety in hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding. For example, one CMS regulation often referred to as “checking the rights of medication administration” requires nurses to confirm specific information several times before medication is administered to a patient.[6]

Standards of Practice

The ANA defines Standards of Professional Nursing Practice as “authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.”[7] These standards are classified into two categories: Standards of Practice and Standards of Professional Performance.

The ANA’s Standards of Practice describe a competent level of nursing practice as demonstrated by the critical thinking model known as the nursing process. The nursing process includes the components of assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation and forms the foundation of the nurse’s decision-making, practice, and provision of care.[8]

Read more information about the nursing process in the “Nursing Process” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[9]

The ANA’s Standards of Professional Performance “describe a competent level of behavior in the professional role, including activities related to ethics, advocacy, respectful and equitable practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, scholarly inquiry, quality of practice, professional practice evaluation, resource stewardship, and environmental health. All registered nurses are expected to engage in professional role activities, including leadership, reflective of their education, position, and role.”[10] This book discusses content related to these professional practice standards. Each professional practice standard is defined in the following sections with information provided to related content in this book and the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e textbook.[11]

Ethics

The ANA’s Ethics standard states, “The registered nurse integrates ethics in all aspects of practice.”[12]

Read about ethical nursing practice in the “Ethical Practice” chapter of this book.

Advocacy

The ANA’s Advocacy standard states, “The registered nurse demonstrates advocacy in all roles and settings.”[13]

Read about nurse advocacy in the “Advocacy” chapter of this book.

Respectful and Equitable Practice

The ANA’s Respectful and Equitable Practice standard states, “The registered nurse practices with cultural humility and inclusiveness.”

Read about cultural humility and culturally responsive care in the “Diverse Patients” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[14]

Communication

The ANA’s Communication standard states, “The registered nurse communicates effectively in all areas of professional practice.”[15]

Read about communicating with clients and team members in the “Communication” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[16]

Read about interprofessional communication strategies that promote patient safety in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Collaboration

The ANA’s Collaboration standard states, “The registered nurse collaborates with the health care consumer and other key stakeholders.”[17]

Read about strategies to enhance the performance of the interprofessional team and manage conflict in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Leadership

The ANA’s Leadership standard states, “The registered nurse leads within the profession and practice setting.”[18]

Read about leadership, management, and implementing change in the “Leadership and Management” chapter of this book.

Read about assigning, delegating, and supervising patient care in the “Delegation and Supervision” chapter of this book.

Read about tools for prioritizing patient care and managing resources for the nursing team in the “Prioritization” chapter of this book.

Education

The ANA’s Education standard states, “The registered nurse seeks knowledge and competence that reflects current nursing practice and promotes futuristic thinking.”[19]

Read about professional development and specialty certification in the “Preparation for the RN Role” chapter of this book.

Scholarly Inquiry

The ANA’s Scholarly Inquiry standard states, “The registered nurse integrates scholarship, evidence, and research findings into practice.”[20]

Read about integrating evidence-based practice into one’s nursing practice in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter of this book.

Quality of Practice

The ANA’s Quality of Practice standard states, “The nurse contributes to quality nursing practice.”[21]

Read about improving quality patient care and participating in quality improvement initiatives in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter of this book.

Professional Practice Evaluation

The ANA’s Professional Practice Evaluation standard states, “The registered nurse evaluates one’s own and others’ nursing practice.”[22]

Read about nursing practice within the legal framework of health care, negligence, malpractice, and protecting your nursing license in the “Legal Implications” chapter of this book.

Read about reviewing the interprofessional team’s performance, providing constructive feedback, and advocating for patient safety with assertive statements in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Resource Stewardship

The ANA’s Resource Stewardship standard states, “The registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan, provide, and sustain evidence-based nursing services that are safe, effective, financially responsible, and used judiciously.”[23]

Read more about health care funding, reimbursement models, budgets and staffing, and resource stewardship in the “Health Care Economics” chapter of this book.

Environmental Health

The ANA’s Environmental Health standard states, “The registered nurse practices in a manner that advances environmental safety and health.”[24]

Read about promoting workplace safety for nurses in the “Safety” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.[25]

Read about fostering a professional environment that does not tolerate abusive behaviors in the “Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team” chapter of this book.

Read about addressing the impacts of social determinants of health in the “Advocacy” chapter of this book.

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Scenario 1

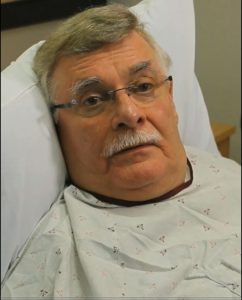

Mr. Jones is a 67-year-old client on the medical-surgical floor who recently underwent a colon resection. See Figure 14.14 for an image of Mr. Jones.[26] He is post-op Day 2 and has been NPO since surgery. He has been receiving IV fluids but has been asking about when he can resume eating.

Questions:

- What assessments should be performed to determine if the client's diet can be progressed?

- What are the first steps during dietary transition from NPO status?

Scenario 2

Mrs. Casey is a 78-year-old widow who recently had a stroke and continues to experience mild right-sided weakness. See Figure 14.15 for an image of Mrs. Casey.[27] She is currently receiving physical therapy in a long-term care facility and ambulates with the assistance of a walker. Mrs. Casey confides, "I am looking forward to going home, but I will miss the three meals a day here."

Her height is 5'2" and she weighs 84 pounds. Her recent lab work results include the following results: Hgb: 8.8 g/dL, WBC 3500, Magnesium 1.4 mg/dL, Albumin 1.0 g/dL

Questions:

- What is Mrs. Casey's BMI and what does this number indicate?

- Analyze Mrs. Casey's recent lab work and interpret the findings.

- Describe focused assessments the nurse should perform regarding Mrs. Casey's nutritional status.

- Create a PES nursing diagnosis statement for Mrs. Casey based on her nutritional status.

- Create a SMART outcome statement for Mrs. Casey.

- Outline planned nutritional interventions for Mrs. Casey while she is at the facility, as well as when she returns home.

- How will you evaluate if your nursing care plan is successful for Mrs. Casey?

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style bowtie question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[28]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style bowtie question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[29]

Test your knowledge using these NCLEX Next Generation-style questions. You may reset and resubmit your answers to the questions in this assignment an unlimited number of times.[30]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style bowtie question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[31]

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style assignment. You may reset and resubmit your answers to the questions in this assignment an unlimited number of times.[32]

Prioritization

As new nurses begin their career, they look forward to caring for others, promoting health, and saving lives. However, when entering the health care environment, they often discover there are numerous and competing demands for their time and attention. Patient care is often interrupted by call lights, rounding physicians, and phone calls from the laboratory department or other interprofessional team members. Even individuals who are strategic and energized in their planning can feel frustrated as their task lists and planned patient-care activities build into a long collection of “to dos.”

Without utilization of appropriate prioritization strategies, nurses can experience time scarcity, a feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against them. Functioning under the burden of time scarcity can cause feelings of frustration, inadequacy, and eventually burnout. Time scarcity can also impact patient safety, resulting in adverse events and increased mortality.[33] Additionally, missed or rushed nursing activities can negatively impact patient satisfaction scores that ultimately affect an institution's reimbursement levels.

It is vital for nurses to plan patient care and implement their task lists while ensuring that critical interventions are safely implemented first. Identifying priority patient problems and implementing priority interventions are skills that require ongoing cultivation as one gains experience in the practice environment.[34] To develop these skills, students must develop an understanding of organizing frameworks and prioritization processes for delineating care needs. These frameworks provide structure and guidance for meeting the multiple and ever-changing demands in the complex health care environment.

Let’s consider a clinical scenario in the following box to better understand the implications of prioritization and outcomes.

Scenario A

Imagine you are beginning your shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. You receive a handoff report on four medical-surgical patients from the night shift nurse:

- Patient A is a 34-year-old total knee replacement patient, post-op Day 1, who had an uneventful night. It is anticipated that she will be discharged today and needs patient education for self-care at home.

- Patient B is a 67-year-old male admitted with weakness, confusion, and a suspected urinary tract infection. He has been restless and attempting to get out of bed throughout the night. He has a bed alarm in place.

- Patient C is a 49-year-old male, post-op Day 1 for a total hip replacement. He has been frequently using his patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump and last rated his pain as a "6."

- Patient D is a 73-year-old male admitted for pneumonia. He has been hospitalized for three days and receiving intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His next dose is due in an hour. His oxygen requirements have decreased from 4 L/minute of oxygen by nasal cannula to 2 L/minute by nasal cannula.

Based on the handoff report you received, you ask the nursing assistant to check on Patient B while you do an initial assessment on Patient D. As you are assessing Patient D's oxygenation status, you receive a phone call from the laboratory department relating a critical lab value on Patient C, indicating his hemoglobin is low. The provider calls and orders a STAT blood transfusion for Patient C. Patient A rings the call light and states she and her husband have questions about her discharge and are ready to go home. The nursing assistant finds you and reports that Patient B got out of bed and experienced a fall during the handoff reports.

It is common for nurses to manage multiple and ever-changing tasks and activities like this scenario, illustrating the importance of self-organization and priority setting. This chapter will further discuss the tools nurses can use for prioritization.

Localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.