4.3 Aseptic Technique

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

In addition to using standard precautions and transmission-based precautions, aseptic technique (also called medical asepsis) is the purposeful reduction of pathogens to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another during a medical procedure. For example, a nurse administering parenteral medication or performing urinary catheterization uses aseptic technique. When performed properly, aseptic technique prevents contamination and transfer of pathogens to the patient from caregiver hands, surfaces, and equipment during routine care or procedures. The word “aseptic” literally means an absence of disease-causing microbes and pathogens. In the clinical setting, aseptic technique refers to the purposeful prevention of microbe contamination from one person or object to another. These potentially infectious, microscopic organisms can be present in the environment, on an instrument, in liquids, on skin surfaces, or within a wound.

There is often misunderstanding between the terms aseptic technique and sterile technique in the health care setting. Both asepsis and sterility are closely related, and the shared concept between the two terms is removal of harmful microorganisms that can cause infection. In the most simplistic terms, asepsis is creating a protective barrier from pathogens, whereas sterile technique is a purposeful attack on microorganisms. Sterile technique (also called surgical asepsis) seeks to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while also maintaining objects as free from microorganisms as possible. It is the standard of care for surgical procedures, invasive wound management, and central line care. Sterile technique requires a combination of meticulous hand washing, creation of a sterile field, using long-lasting antimicrobial cleansing agents such as betadine, donning sterile gloves, and using sterile devices and instruments.

Principles of Aseptic Non-Touch Technique

Aseptic non-touch technique (ANTT) is the most commonly used aseptic technique framework in the health care setting and is considered a global standard. There are two types of ANTT: surgical-ANTT (sterile technique) and standard-ANTT.

Aseptic non-touch technique starts with a few concepts that must be understood before it can be applied. For all invasive procedures, the “ANTT-approach” identifies key parts and key sites throughout the preparation and implementation of the procedure. A key part is any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs, syringe tips, needles, and dressings. A key site is any nonintact skin, potential insertion site, or access site used for medical devices connected to the patients. Examples of key sites include open wounds and insertion sites for intravenous (IV) devices and urinary catheters.

ANTT includes four underlying principles to keep in mind while performing invasive procedures:

- Always wash hands effectively.

- Never contaminate key parts.

- Touch non-key parts with confidence.

- Take appropriate infective precautions.

Preparing and Preventing Infections Using Aseptic Technique

When planning for any procedure, careful thought and preparation of many infection control factors must be considered beforehand. While keeping standard precautions in mind, identify anticipated key sites and key parts to the procedure. Consider the degree to which the environment must be managed to reduce the risk of infection, including the expected degree of contamination and hazardous exposure to the clinician. Finally, review the expected equipment needed to perform the procedure and the level of key part or key site handling. See Table 4.3 for an outline of infection control measures when performing a procedure.

Table 4.3 Infection Control Measures When Performing Procedures

| Infection Control Measure | Key Considerations | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental control |

|

|

| Hand hygiene |

|

|

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) |

|

|

| Aseptic field management | Determine level of aseptic field needed and how it will be managed before the procedure begins:

|

General aseptic field:

IV irrigation Dry dressing changes Critical aseptic field: Urinary catheter placement Central line dressing change Sterile dressing change |

| Non-touch technique |

|

|

| Sequencing |

|

|

Use of Gloves and Sterile Gloves

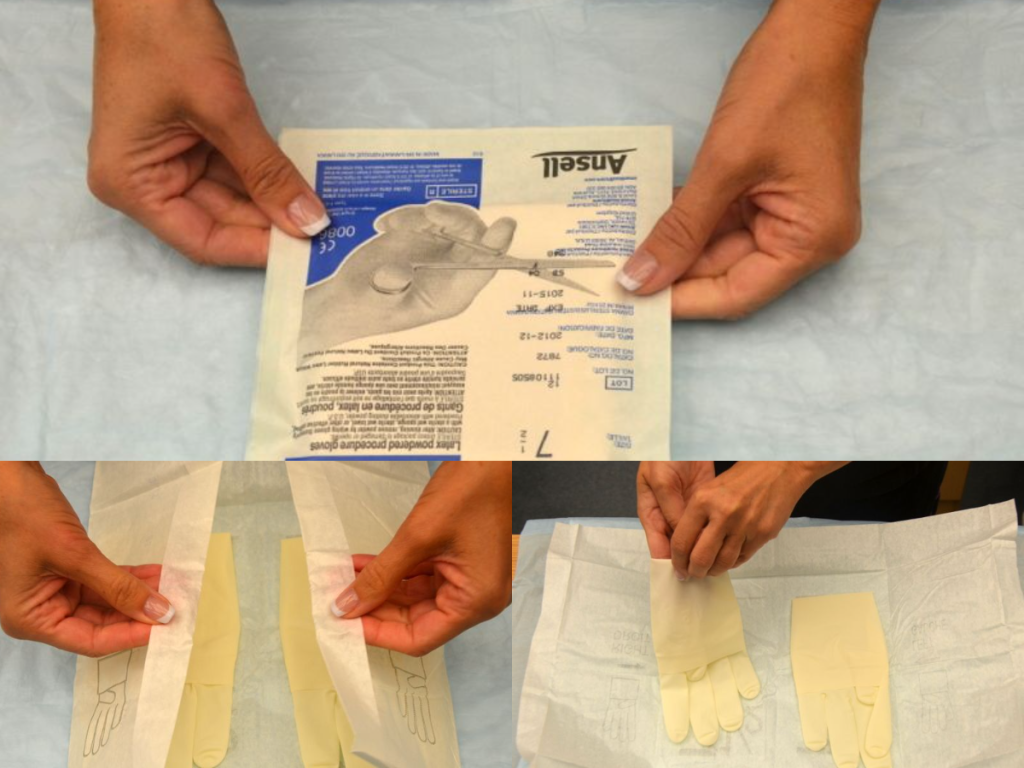

There are two different levels of medical-grade gloves available to health care providers: clean (exam) gloves and sterile (surgical) gloves. Generally speaking, clean gloves are used whenever there is a risk of contact with body fluids or contaminated surfaces or objects. Examples include starting an intravenous access device or emptying a urinary catheter collection bag. Alternatively, sterile gloves meet FDA requirements for sterilization and are used for invasive procedures or when contact with a sterile site, tissue, or body cavity is anticipated. Sterile gloves are used in these instances to prevent transient flora and reduce resident flora contamination during a procedure, thus preventing the introduction of pathogens. For example, sterile gloves are required when performing central line dressing changes, insertion of urinary catheters, and during invasive surgical procedures. See Figure 4.15[1] for images of a nurse opening and removing sterile gloves from packaging.

See the “Checklist for Applying and Removing Sterile Gloves” for details on how to apply sterile gloves.

Applying Sterile Gloves on YouTube[2]

- “Book-pictures-2015-199-001-300x241.jpg,” “Book-pictures-2015-215.jpg,” and “Book-pictures-2015-219.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology are licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/sterile-gloving/ ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2017, April 28). Sterile gloving nursing technique | Don/donning sterile gloves tips. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/lumZOF-METc ↵

Case Study

An 85-year-old woman was admitted with sudden onset of dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and right upper arm edema. She had a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placed three weeks previously for treatment of osteomyelitis of the left hand. A caretaker had been infusing her antibiotics and managing her PICC with the oversight of a home care nurse. A chest computerized tomography scan confirmed the presence of a pulmonary embolism. She was admitted to the inpatient floor at change of shift, and orders were received for a weight-based heparin bolus and infusion. The bolus was administered, and the infusion was initiated. During handoff report to the next shift, the pump alarm sounded. In responding to the alarm, the oncoming nurse discovered that the entire bag of heparin (25,000 units) had infused in less than 30 minutes. She discovered the rate on the pump was set by the previous nurse at 600 mL/hour rather than the weight-adjusted 600 units/hour.

The oncoming nurse who discovered the heparin error immediately disconnected the infusion, assessed the client for signs of bleeding, and notified the physician of the error. Appropriate precautions were initiated and an incident report was submitted. Subsequently, an investigation was conducted by the unit supervisor and the risk manager by interviewing involved staff. They found that the client's admitting nurse, who administered the heparin bolus and infusion, was a traveling nurse who had been in the organization for three weeks and had been floated to the telemetry unit for the first time. While the traveling nurse had been trained on an orthopedic unit, she had not initiated a heparin infusion at this facility. The facility used an infusion pump that included a drug library with medication-specific infusion limits for client safety. The nurse had been trained to use the infusion pump drug library in a brief orientation, but she had witnessed several nurses bypass this safety measure. In addition, although she had her heparin bolus and infusion calculations double-checked by another nurse, she was not aware that this double-check should include a review of pump settings. Finally, because the change of shift handoff report was hurried, it did not include a bedside report to review infusions and client status with the oncoming nurse. What appeared to be a serious individual error was, in fact, a complex series of failures in the facility's safety culture that placed a nurse in the very difficult position of making an error that placed a client at risk of harm. Fortunately, no significant bleeding events occurred as a result of the error.[1]

Reflective Questions

- Create a list of safety failures in this example and categorize them based on the QSEN competencies.

- Outline communication tools and best practices that could have prevented this error from occurring.

Nurses advocate for issues in their communities and their organizations.

Addressing Social Determinants of Health

Advocacy is commonly perceived as acting on behalf of a client, but it can be a much broader action than affecting a single client and their family members. Nurses advocate for building healthier communities by addressing social determinants of health (SDOH). SDOH are the conditions in the environments where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of outcomes. SDOH include health care access and quality, neighborhood and environment, social and community context, economic stability, and education access and quality. Social determinants of health (SDOH) have a major impact on people’s health, well-being, and quality of life. See Figure 10.2[2] for an illustration of SDOH.[3]

Specific examples of addressing SDOH include the following goals:

- Improving safe housing and public transportation

- Decreasing discrimination and violence

- Expanding quality education and job opportunities

- Increasing access to nutritious foods and physical activity opportunities

- Promoting clean air and clean water

- Enhancing language and literacy skills[4]

SDOH contribute to health disparities and inequities among different socioeconomic groups. For example, individuals who don't have access to grocery stores with healthy foods are less likely to have good nutrition, increasing their risk for health conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, and potentially lowering their life expectancy relative to people who do have access to healthy foods.[5]

One of Healthy People 2030’s goals specifically relates to advocacy regarding SDOH. The goal states, “Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and well-being for all.” Across the United States, people and organizations at the local, state, territorial, tribal, and national levels are working hard to improve health and reduce health disparities by addressing SDOH.[6] Read more information about these advocacy efforts in the following box.

Read more about efforts addressing SDOH at Healthy People 2030.