23.8 Functional Health and Activities of Daily Living

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Functional health assessment collects data related to the patient’s functioning and their physical and mental capacity to participate in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are daily basic tasks that are fundamental to everyday functioning (e.g., hygiene, elimination, dressing, eating, ambulating/moving). See Figure 2.2[1] for an illustration of ADLs.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) are more complex daily tasks that allow patients to function independently such as managing finances, paying bills, purchasing and preparing meals, managing one’s household, taking medications, and facilitating transportation. See Figure 2.3[2] for an illustration of IADLs. Assessment of IADLs is particularly important to inquire about with young adults who have just moved into their first place, as well as with older patients with multiple medical conditions and/or disabilities.

Information obtained when assessing functional health provides the nurse a holistic view of a patient’s human response to illness and life conditions. It is helpful to use an assessment framework, such as Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns,[3] to organize interview questions according to evidence-based patterns of human responses. Using this framework provides the patient and their family members an opportunity to identify health-related concerns to the nurse that may require further in-depth assessment. It also verifies patient understanding of conditions so that misperceptions can be clarified. This framework includes the following categories:

- Nutritional-Metabolic: Food and fluid consumption relative to metabolic need

- Elimination: Excretion including bowel and bladder

- Activity-Exercise: Activity and exercise

- Sleep-Rest: Sleep and rest

- Cognitive-Perceptual: Cognition and perception

- Role-Relationship: Roles and relationships

- Sexuality-Reproductive: Sexuality and reproduction

- Coping-Stress Tolerance: Coping and effectiveness of managing stress

- Value-Belief: Values, beliefs, and goals that guide choices and decisions

- Self-Perception and Self-Concept: Self-concept and mood state[4]

- Health Perception-Health Management: A patient’s perception of their health and well-being and how it is managed. This is an umbrella category of all the categories above and underlies performing a health history.

The functional health section can be started by saying, “I would like to ask you some questions about factors that affect your ability to function in your day-to-day life. Feel free to share any health concerns that come to mind during this discussion.” Focused interview questions for each category are included in Table 2.8. Each category is further described below.

Nutrition

The nutritional category includes, but is not limited to, food and fluid intake, usual diet, financial ability to purchase food, time and knowledge to prepare meals, and appetite. This is also an opportune time to engage in health promotion discussions about healthy eating. Be aware of signs for malnutrition and obesity, especially if rapid and excessive weight loss or weight gain have occurred.

Life Span Considerations

When assessing nutritional status, the types of questions asked and the level of detail depend on the developmental age and health of the patient. Family members may also provide important information.

- Infants: Ask parents about using breast milk or formula, amount, frequency, supplements, problems, and introductions of new foods.

- Pregnant women: Include questions about the presence of nausea and vomiting and intake of folic acid, iron, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, and calcium.

- Older adults or patients with disabling illnesses: Inquire about the ability to purchase and cook their food, decreased sense of taste, ability to chew or swallow foods, loss of appetite, and enough fiber and nutrients.[5]

Elimination

Elimination refers to the removal of waste products through the urine and stool. Health care professionals refer to urinating as voiding and stool elimination as having a bowel movement. Familiar terminology may need to be used with patients, such as “pee” and “poop.”

Constipation commonly occurs in hospitalized patients, so it is important to assess the date of their last bowel movement and monitor the frequency, color, and consistency of their stool.

Assess urine concentration, frequency, and odor, especially if concerned about urinary tract infection or incontinence. Findings that require further investigation include dysuria (pain or difficulty upon urination), blood in the stool, melena (black, tarry stool), constipation, diarrhea, or excessive laxative use.[6]

Life Span Considerations

When assessing elimination, the types of questions asked and the level of detail depends on the developmental age and health of the patient.

Toddlers: Ask parents or guardians about toilet training. Toilet training takes several months, occurs in several stages, and varies from child to child. It is influenced by culture and depends on physical and emotional readiness, but most children are toilet trained between 18 months and three years.

Older Adults: Constipation and incontinence are common symptoms associated with aging. Additional focused questions may be required to further assess these issues.[7]

Mobility, Activity, and Exercise

Mobility refers to a patient’s ability to move around (e.g., sit up, sit down, stand up, walk). Activity and exercise refer to informal and/or formal activity (e.g., walking, swimming, yoga, strength training). In addition to assessing the amount of exercise, it is also important to assess activity because some people may not engage in exercise but have an active lifestyle (e.g., walk to school or work in a physically demanding job).

Findings that require further investigation include insufficient aerobic exercise and identified risks for falls.[8]

Life Span Considerations

Mobility and activity depend on developmental age and a patient’s health and illness status. With infants, it is important to assess their ability to meet specific developmental milestones at each well-baby visit. Mobility can become problematic for patients who are ill or are aging and can result in self-care deficits. Thus, it is important to assess how a patient’s mobility is affecting their ability to perform ADLs and IADLs.[9]

Sleep and Rest

The sleep and rest category refers to a patient’s pattern of rest and sleep and any associated routines or sleeping medications used. Although it varies for different people and their life circumstances, obtaining eight hours of sleep every night is a general guideline. Findings that require further investigation include disruptive sleep patterns and reliance on sleeping pills or other sedative medications.[10]

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults: Disruption in sleep patterns can be especially troublesome for older adults. Assessing sleep patterns and routines will contribute to collaborative interventions for improved rest.[11]

Cognitive and Perceptual

The cognitive and perceptual category focuses on a person’s ability to collect information from the environment and use it in reasoning and other thought processes. This category includes the following:

- Adequacy of vision, hearing, taste, touch, feeling, and smell

- Any assistive devices used

- Pain level and pain management

- Cognitive functional abilities, such as orientation, memory, reasoning, judgment, and decision-making[12]

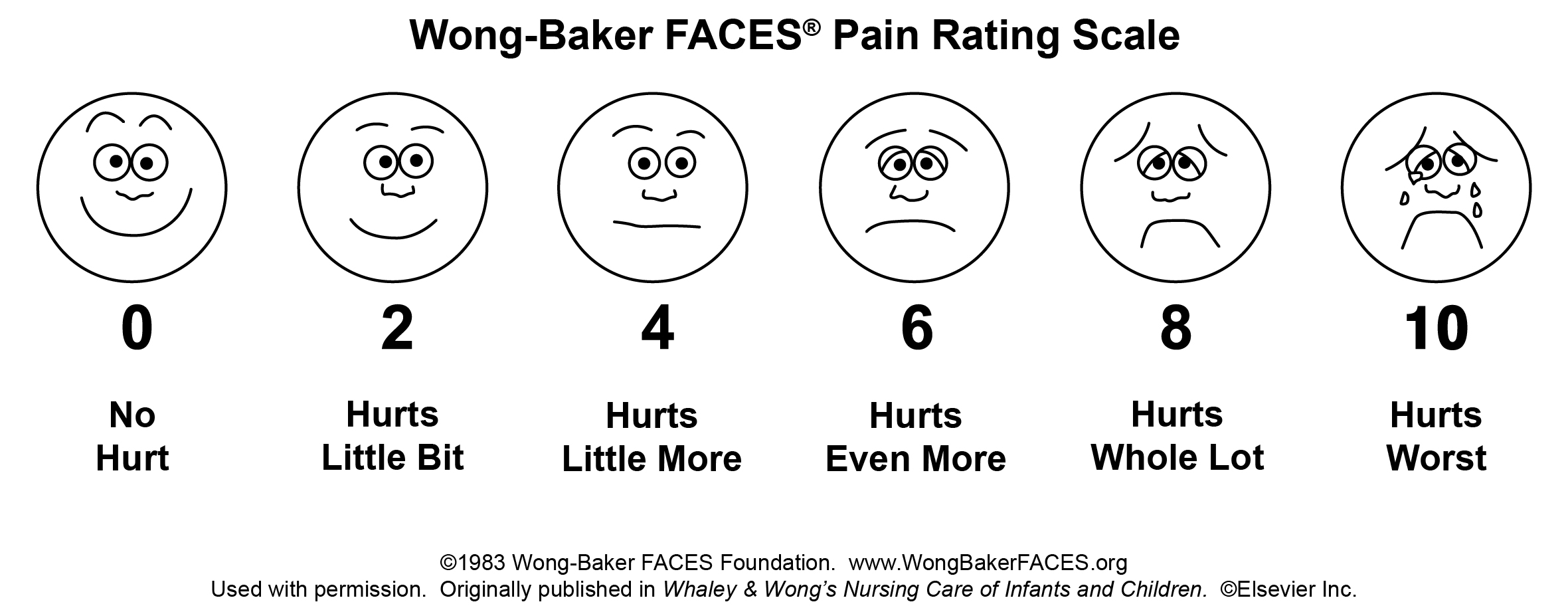

If a patient is experiencing pain, it is important to perform an in-depth assessment using the PQRSTU method described in the “Reason for Seeking Health Care” section of this chapter. It is also helpful to use evidence-based assessment tools when assessing pain, especially for patients who are unable to verbally describe the severity of their pain. See Figure 2.4[13] for an image of the Wong-Baker FACES tool that is commonly used in health care.

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults: Older adults are especially at risk for problems in the cognitive and perceptual category. Be alert for cues that suggest deficits are occurring that have not been previously diagnosed.

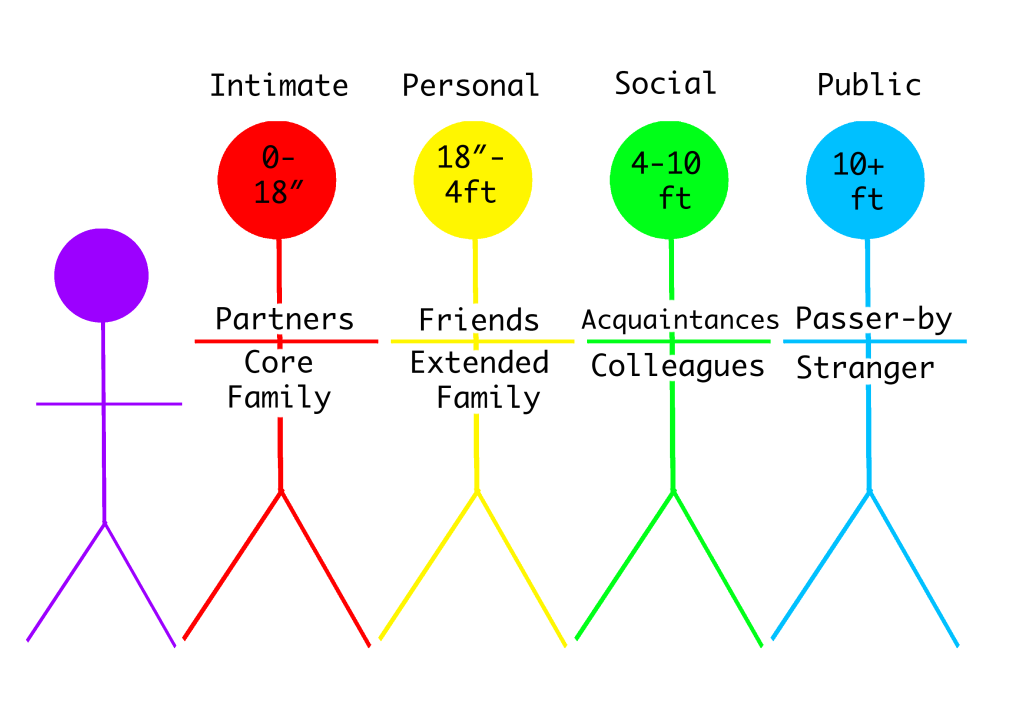

Roles – Relationships

Quality of life is greatly influenced by the roles and relationships established with family, friends, and the broader community. Roles often define our identity. For example, a patient may describe themselves as a “mother of an 8-year-old.” This category focuses on roles and relationships that may be influenced by health-related factors or may offer support during illness.[14] Findings that require further investigation include indications that a patient does not have any meaningful relationships or has “negative” or abusive relationships in their lives.

Life Span Considerations

Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with any of the following characteristics: isolation from family and friends during crisis, language barriers, loss of a significant person or pet, loss of job, significant home care needs, prolonged caregiving, history of abuse, history of substance abuse, or homelessness.[15]

Sexuality – Reproduction

Sexuality and sexual relations are an aspect of health that can be affected by illness, aging, and medication. This category includes a person’s gender identity and sexual orientation, as well as reproductive issues. It involves a combination of emotional connection, physical companionship (holding hands, hugging, kissing) and sexual activity that impact one’s feeling of health.[16]

The Joint Commission has defined terms to use when caring for diverse patients. Gender identity is a person’s basic sense of being male, female, or other gender.[17] Gender expression are characteristics in appearance, personality, and behavior that are culturally defined as masculine or feminine.[18] Sexual orientation is the preferred term used when referring to an individual’s physical and/or emotional attraction to the same and/or opposite gender.[19] LGBTQ is an acronym standing for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer population. It is an umbrella term that generally refers to a group of people who are diverse in gender identity and sexual orientation. It is important to provide a safe environment to discuss health issues because the LGBTQ population experiences higher rates of smoking, alcohol use, substance abuse, HIV and other STD infections, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, and eating disorders as a result of stigma and marginalization.[20]

Life Span Considerations

Although sexuality is frequently portrayed in the media, individuals often consider these topics as private subjects. Use sensitivity when discussing these topics with different age groups across cultural beliefs while maintaining professional boundaries.

Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community.

Coping-Stress Tolerance

Individuals experience stress that can lead to dysfunction if not managed in a healthy manner. Throughout life, healthy and unhealthy coping strategies are learned. Coping strategies are behaviors used to manage anxiety. Effective strategies control anxiety and lead to problem-solving but ineffective strategies can lead to abuse of food, tobacco, alcohol, or drugs.[21] Nurses teach and reinforce effective coping strategies.

Substance Use and Abuse

Alcohol, tobacco products, marijuana, and drugs are often used as ineffective coping strategies. It is important to use a nonjudgmental approach when assessing a patient’s use of substances, so they do not feel stigmatized. Substance abuse can affect people of all ages. Make a distinction between use and abuse as you assess frequency of use and patterns of behavior. Substance abuse often causes disruption in everyday function (e.g., loss of employment, deterioration of relationships, or precarious living circumstances) because of dependence on a substance. Action is needed if patients indicate that they have a problem with substance use or show signs of dependence, addiction, or binge drinking.[22]

Life Span Considerations

Some individuals are at increased risk for problems with coping strategies and stress management. Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with characteristics such as uncertainty in medical diagnosis or prognosis, financial problems, marital problems, poor job fit, or few close friends and family members.[23]

Value-Belief

This category includes values and beliefs that guide decisions about health care and can also provide strength and comfort to individuals. It is common for a person’s spirituality and values to be influenced by religious faith. A value is an accepted principle or standard of an individual or group. A belief is something accepted as true with a sense of certainty. Spirituality is a way of living that comes from a set of values and beliefs that are important to a person. The Joint Commission asks health care professionals to respect patients’ cultural and personal values, beliefs, and preferences and accommodate patients’ rights to religious and other spiritual services.[24] When performing an assessment, use open-ended questions to allow the patient to share values and beliefs they believe are important. For example, ask, “I am interested in your spiritual and religious beliefs and how they relate to your health. Can you share with me any spiritual beliefs or religious practices that are important to you during your stay?”

Self-Perception and Self-Concept

The focus of this category is on the subjective thoughts, feelings, and attitudes of a patient about themself. Self-concept refers to all the knowledge a person has about themself that makes up who they are (i.e., their identity). Self-esteem refers to a person’s self-evaluation of these items as being worthy or unworthy. Body image is a mental picture of one’s body related to appearance and function. It is best to assess these items toward the end of the interview because you will have already collected data that contributes to an understanding of the patient’s self-concept. Factors that influence a patient’s self-concept vary from person to person and include elements of life they value, such as talents, education, accomplishments, family, friends, career, financial status, spirituality, and religion.[25] The self-perception and self-concept category also focuses on feelings and mood states such as happiness, anxiety, hope, power, anger, fear, depression, and control.[26]

Life Span Considerations

Some individuals are at risk for problems with self-perception and self-concept. Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with characteristics such as uncertainty regarding a medical diagnosis or surgery, significant personal loss, history of abuse or neglect, loss of body part or function, or history of substance abuse.[27]

Violence and Trauma

There are many types of violence that a person may experience, including neglect or physical, emotional, mental, sexual, or financial abuse. You are legally mandated to report suspected cases of child abuse or neglect, as well as suspected cases of elder abuse. At any time, if you or the patient is in immediate danger, follow agency policy and procedure.

Trauma results from violence or other distressing events in a life. Collaborative intervention with the patient is required when violence and trauma are identified. People respond in different ways to trauma. It is important to use a trauma-informed approach when caring for patients who have experienced trauma. For example, a patient may respond to the traumatic situation in a way that seems unfitting (such as with laughter, ambivalence, or denial). This does not mean the patient is lying but can be a symptom of trauma. To reduce the effects of trauma, it is important to implement collaborative interventions to support patients who have experienced trauma.[28]

Loss of Body Part

A person can have negative feelings or perceptions about the characteristics, function, or limits of a body part as a result of a medical condition, surgery, trauma, or mental condition. Pay attention to cues, such as neglect of a body part or negative comments about a body part and use open-ended questions to obtain additional information.

Mental Health

Mental health is frequently underscreened and unaddressed in health care. The mental health of all patients should be assessed, even if they appear well or state they have no mental health concerns so that any changes in condition are quickly noticed and treatment implemented. Mental health includes emotional and psychological symptoms that can affect a patient’s day-to-day ability to function. The World Health Organization (2014) defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes their own potential, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to their community.”[29] Mental illness includes conditions diagnosed by a health care provider, such as depression, anxiety, addiction, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and others. Mental illness can disrupt everyday functioning and affect a person’s employment, education, and relationships.

It is helpful to begin this component of a mental health assessment with a statement such as, “Mental health is an important part of our lives, so I ask all patients about their mental health and any concerns or questions they may have.”[30] Be attentive of critical findings that require intervention. For example, if a patient talks about feeling hopeless or depressed, it is important to screen for suicidal thinking. Begin with an open-ended question, such as, “Have you ever felt like hurting yourself?” If the patient responds with a “Yes,” then progress with specific questions that assess the immediacy and the intensity of the feelings. For example, you may say, “Tell me more about that feeling. Have you been thinking about hurting yourself today? Have you put together a plan to hurt yourself?” When assessing for suicidal thinking, be aware that a patient most at risk is someone who has a specific plan about self-harm and can specify how and when they will do it. They are particularly at risk if planning self-harm within the next 48 hours. The age of the patient is not a factor in this determination of risk. If you believe the patient is at high risk, do not leave the patient alone. Collaborate with them regarding an immediate plan for emergency care.[31]

Health Perception-Health Management

Health perception-health management is an umbrella term encompassing all of the categories described above, as well as environmental health.

Environmental Health

Environmental health refers to the safety of a patient’s physical environment, also called a social determinant of health. Examples of environmental health include, but are not limited to, exposure to violence in the home or community; air pollution; and availability of grocery stores, health care providers, and public transportation. Findings that require further investigation include a patient living in unsafe environments.[32]

See Table 2.8 for sample focused questions for all categories related to functional health.[33]

Table 2.8 Focused Interview Questions for Functional Health Categories[34]

Begin this section by saying, “I would like to ask you some questions about factors that affect your ability to function in your day-to-day life. Feel free to share any health concerns that come to mind during this discussion.”

| Category | Focused Questions |

|---|---|

| Nutrition | Tell me about your diet.

What foods do you usually eat? What fluids do you usually drink every day? What have you eaten in the last 24 hours? Is this typical of your usual eating pattern? Tell me about your appetite. Have you had any changes in your appetite? Do you have any goals related to your nutrition? Do you have any financial concerns about purchasing food? Are you able to prepare the meals you want to eat? |

| Elimination | When was your last bowel movement?

Do you have any problems with constipation, diarrhea, or incontinence? Do you take laxatives or stool softeners? Do you have any problems urinating, such as frequent urination or burning on urination? Do you ever experience leaking or dribbling of urine? |

| Mobility, Activity, and Exercise | Tell me about your ability to move around.

Do you have any problems sitting up, standing up, or walking? Do you use any mobility aids (e.g., cane, walker, wheelchair)? Tell me about the activity and/or exercise in which you engage. What type? How frequent? For how long? |

| Sleep and Rest | Tell me about your sleep routine. How many hours of sleep do you usually get?

Do you feel rested when you awaken? Do you do anything to wind down before you go to bed (e.g., watch TV, read)? Do you take any sleeping medication? Do you take any naps during the day? |

| Cognitive and Perceptual | Are you having any pain?

Note: If present, use the PQRSTU method to further assess pain. Are you having any issues with seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, or feeling things? Have you noticed any changes in memory or problems concentrating? Have you noticed any changes in the ability to make decisions? What is the easiest way for you to learn (e.g., written materials, explanations, or learning-by-doing)? |

| Roles and Relationships | Tell me about the most influential relationships in your life with family and friends.

How do these relationships influence your day-to-day life, health, and illness? Who are the people with whom you talk to when you require support or are struggling in your life? Do you have family or others dependent on you? Have you had any recent losses of someone important to you, a pet, or a job? Do you feel safe in your current relationship? |

| Sexuality-Reproduction | The expression of love and caring in a sexual relationship and creation of family are often important aspects in a person’s life. Do you have any concerns about your sexual health?

Tell me about the ways that you ensure your safety when engaging in intimate and sexual practices. |

| Coping-Stress | Tell me about the stress in your life.

Have you experienced a recent loss in your life that has impacted you? How do you cope with stress? |

| Values-Belief | I am interested in your spiritual and religious beliefs and how they relate to your health. Can you share with me any spiritual beliefs or religious practices that are important to you? |

| Self-Perception and Self-Concept |

Tell me what makes you who you are. How would you describe yourself? Have you noticed any changes in how you view your body or the things you can do? Are these a problem for you? Have you found yourself feeling sad, angry, fearful, or anxious? What helps you to feel better when this happens? Have you ever used any tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes, pipes, vaporizers, hookah)? If so, how much? How much alcohol do you drink every week? Have you used cannabis products? If so, how often do you use them? Have you ever used drugs or prescription drugs that were not prescribed for you? If so, what type? Have you ever felt you had a problem with any of these substances because they affected your daily life? If so, tell me more. Do you want to quit any of these substances? Many patients have experienced violence or trauma in their lives. Have you experienced any violence or trauma in your life? How has it affected you? Would you like to talk with someone about it?

|

| Health Perception – Health Management |

Tell me about how you take care of yourself and manage your home. Have you had any falls in the past six months? Do you have enough finances to pay your bills and purchase food, medications, and other needed items? Do you have any current or future concerns about being able to function independently? Tell me about where you live. Do you have any concerns about safety in your home or neighborhood? Tell me about any factors in your environment that may affect your health. Do you have any concerns about how your environment is affecting your health? |

- “ADL-1024x534.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/healthassessment/chapter/functional-health/ ↵

- “iADL-1024x494.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/healthassessment/chapter/functional-health/ ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- Wong-Baker FACES Foundation. (2020). Wong-Baker FACES® Pain Rating Scale. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2018). The source, 16(1). https://store.jcrinc.com/assets/1/14/ts_16_2018_01.pdf ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

The period of a disease after the initial entry of the pathogen into the host but before symptoms develop.

The disease stage after the incubation period when the pathogen continues to multiply and the host begins to experience general signs and symptoms of illness that result from activation of the immune system, such as fever, pain, soreness, swelling, or inflammation.

Infections that develop rapidly and generally last only 10-14 days.

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish among the different levels of nursing education

- Specify the ethical and legal boundaries of the student nurse as presented in the Code of Ethics and the Nurse Practice Act

- Detail responsibility for maintaining client confidentiality

- Describe the contribution of all members of the health care team

- Identify the role of evidence-based practice in nursing

- Identify the concept of quality in client care

- Discuss nursing scope of practice and standards of care

- Compare various settings in which nurses work

- Outline professional nursing organizations

Scope of practice refers to services a trained health professional is deemed competent to perform and permitted to undertake according to the terms of their professional nursing license.[1] Nursing scope of practice provides a legal framework and structured guidance for activities that practical nurses and registered nurses can perform based on their nursing license. As a nursing student, and in the future as a nurse, it is always important to consider if you can perform a task you are requested to do based on your legal scope of practice - or are you putting your nursing education or nursing license at risk?

Nurses must also follow standards when providing nursing care. Standards are set by several organizations, including your state’s Nurse Practice Act, the American Nurses Association (ANA), agency policies and procedures, and federal regulators. These standards help guide nursing actions with the intent that safe, competent care is provided to the public.

This chapter will provide an overview of basic concepts related to nursing scope of practice and standards of care.

Health Care Settings

There are several levels of health care including primary, secondary, and tertiary care. Each of these levels focuses on different aspects of health care and is typically provided in different settings.

Primary Care

Primary care promotes wellness and prevents disease. This care includes health promotion, education, protection (such as immunizations), early disease screening, and environmental considerations. Settings providing this type of health care include physician offices, public health clinics, school nursing, and community health nursing.

Secondary care

Secondary care occurs when a person has contracted an illness or injury and requires medical care. Secondary care is often referred to as acute care. Secondary care can range from uncomplicated care to repair a small laceration or treat a strep throat infection to more complicated emergent care such as treating a head injury sustained in an automobile accident. Whatever the problem, the client needs medical and nursing attention to return to a state of health and wellness. Secondary care is provided in settings such as physician offices, clinics, urgent care facilities, or hospitals. Specialized units include areas such as critical care, burn units, neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, and transplant services.

Tertiary Care

Tertiary care addresses the long-term effects from chronic illnesses or conditions with the purpose to restore a client's maximum physical and mental function. The goal of tertiary care is to achieve the highest level of functioning possible while managing the chronic illness. For example, a client who falls and fractures their hip will need secondary care to set the broken bones, but may need tertiary care to regain their strength and ability to walk even after the bones have healed. Clients with incurable diseases, such as dementia, may need specialized tertiary care to provide support they need for daily functioning. Tertiary care settings include rehabilitation units, assisted living facilities, adult day care, skilled nursing units, home care, and hospice centers.

Health Care Team

No matter the setting, quality health care requires a team of health care professionals collaboratively working together to deliver holistic, individualized care. Nursing students must be aware of the roles and contributions of various health care team members. The health care team consists of health care providers, nurses (licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced practice registered nurses), unlicensed assistive personnel, and a variety of interprofessional team members.

Health Care Providers

The Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act defines a health care provider as, "A physician, podiatrist, dentist, optometrist, or advanced practice nurse.”[2] Providers are responsible for ordering diagnostic tests such as blood work and X-rays, diagnosing a client’s medical condition, developing a medical treatment plan, and prescribing medications. In a hospital setting, the medical treatment plan developed by a provider is communicated in the “History and Physical” component of the client's medical record with associated prescriptions (otherwise known as "orders"). Prescriptions or “orders” include diagnostic and laboratory tests, medications, and general parameters regarding the care that each client is to receive. Nurses should respectfully clarify prescriptions they have questions or concerns about to ensure safe client care. Providers typically visit hospitalized clients daily in what is referred to as "rounds." It is helpful for nurses and nursing students to attend provider rounds for their assigned clients to be aware of and provide input regarding the current medical treatment plan, seek clarification, or ask questions. This helps to ensure that the provider, nurse, and client have a clear understanding of the goals of care and minimizes the need for follow-up phone calls.

Nurses

There are three levels of nurses as defined by each state's Nurse Practice Act: Licensed Practical Nurse/Vocational Nurse (LPN/LVN), Registered Nurse (RN), and Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN).

Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) defines a licensed practical nurse (LPN) as, “An individual who has completed a state-approved practical or vocational nursing program, passed the NCLEX-PN examination, and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide client care.”[3] In some states, the term licensed vocational nurse (LVN) is used. LPNs/LVNs typically work under the supervision of a registered nurse, advanced practice registered nurse, or physician.[4] LPNs provide "basic nursing care" and work with stable and/or chronically ill populations. Basic nursing care is defined by the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act as “care that can be performed following a defined nursing procedure with minimal modification in which the responses of the client to the nursing care are predictable.”[5] LPNs/LVNs typically collect client assessment information, administer medications, and perform nursing procedures according to their scope of practice in that state. The Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e textbook discusses the skills and procedures that LPNs frequently perform in Wisconsin. See the following box for additional details about the scope of practice of the Licensed Practical Nurse in Wisconsin.

Scope of Practice for Licensed Practical Nurses in Wisconsin[6]

"The Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act defines the scope of practice for Licensed Practical Nurses as the following: “In the performance of acts in basic patient situations, the LPN shall, under the general supervision of an RN or the direction of a provider:

(a) Accept only patient care assignments which the LPN is competent to perform.

(b) Provide basic nursing care.

(c) Record nursing care given and report to the appropriate person changes in the condition of a patient.

(d) Consult with a provider in cases where an LPN knows or should know a delegated act may harm a patient.

(e) Perform the following other acts when applicable:

- Assist with the collection of data.

- Assist with the development and revision of a nursing care plan.

- Reinforce the teaching provided by an RN provider and provide basic health care instruction.

- Participate with other health team members in meeting basic patient needs.”

Registered Nurses

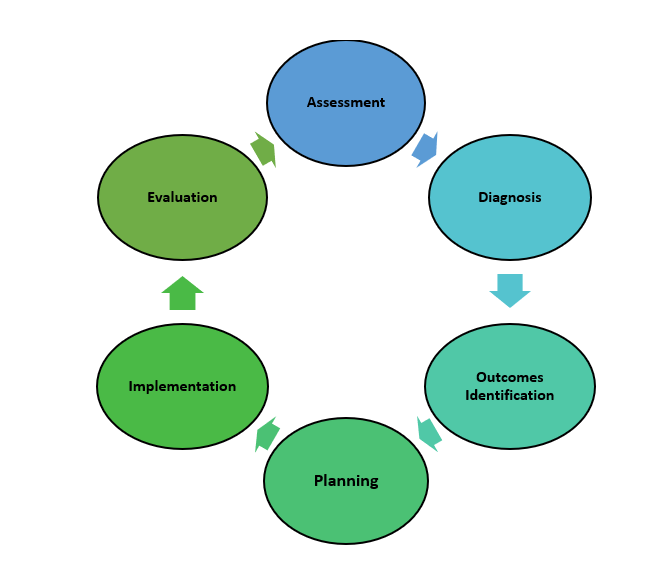

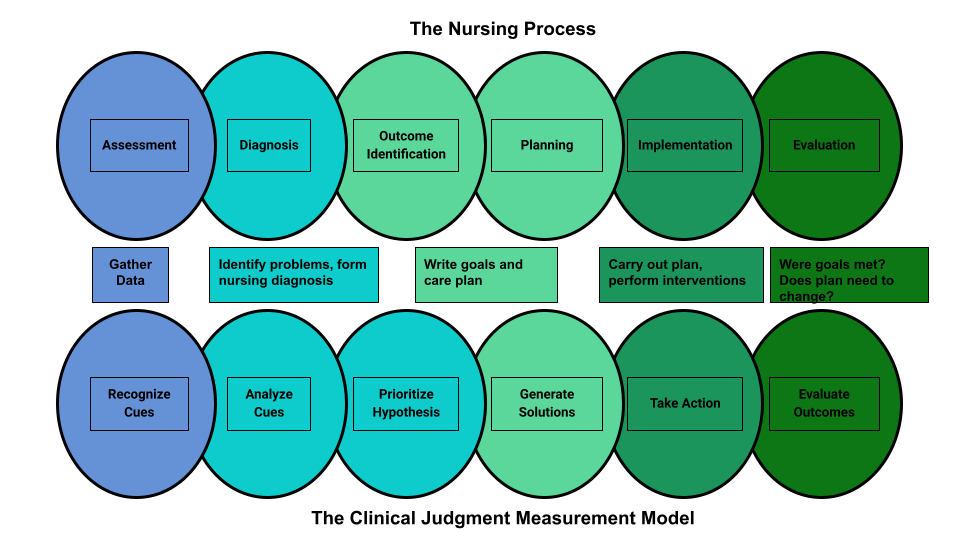

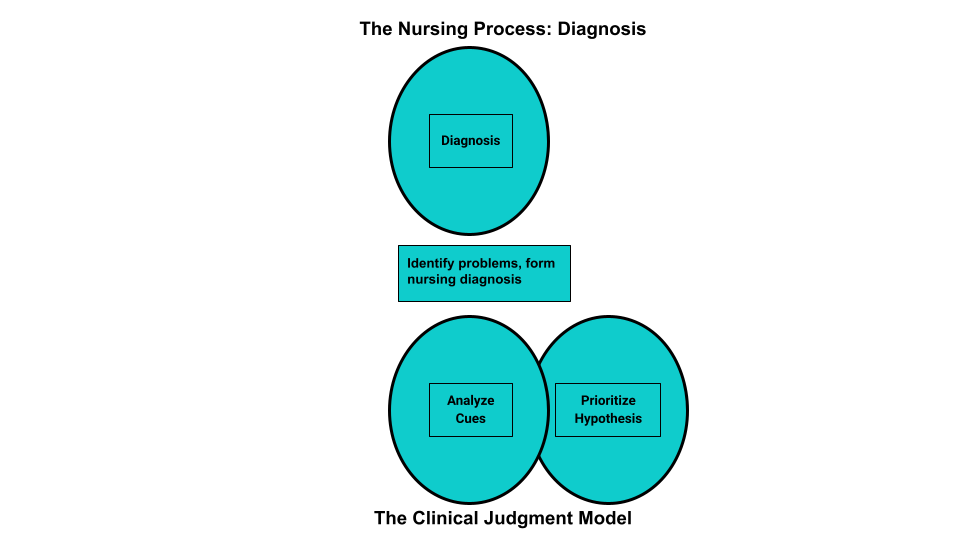

The NCSBN defines a Registered Nurse (RN) as “An individual who has graduated from a state-approved school of nursing, passed the NCLEX-RN examination and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide client care.”[7] Registered Nurses (RNs) use the nursing process as a critical thinking model as they make decisions and use clinical judgment regarding client care. The nursing process is discussed in more detail in the “Nursing Process” chapter of this book. RNs may be delegated tasks from providers or may delegate tasks to LPNs and UAPs with supervision. See the following box for additional details about the scope of practice for Registered Nurses in the state of Wisconsin.

Scope of Practice for Registered Nurses in Wisconsin[8]

(1) "GENERAL NURSING PROCEDURES. An RN shall utilize the nursing process in the execution of general nursing procedures in the maintenance of health, prevention of illness or care of the ill. The nursing process consists of the steps of assessment, planning, intervention, and evaluation. This standard is met through performance of each of the following steps of the nursing process:

(a) Assessment. Assessment is the systematic and continual collection and analysis of data about the health status of a patient culminating in the formulation of a nursing diagnosis.

(b) Planning. Planning is developing a nursing plan of care for a patient, which includes goals and priorities derived from the nursing diagnosis.

(c) Intervention. Intervention is the nursing action to implement the plan of care by directly administering care or by directing and supervising nursing acts delegated to LPNs or less skilled assistants.

(d) Evaluation. Evaluation is the determination of a patient’s progress or lack of progress toward goal achievement, which may lead to modification of the nursing diagnosis.

(2) PERFORMANCE OF DELEGATED ACTS. In the performance of delegated acts, an RN shall do all of the following:

(a) Accept only those delegated acts for which there are protocols or written or verbal orders.

(b) Accept only those delegated acts for which the RN is competent to perform based on his or her nursing education, training or experience.

(c) Consult with a provider in cases where the RN knows or should know a delegated act may harm a patient.

(d) Perform delegated acts under the general supervision or direction of provider.

(3) SUPERVISION AND DIRECTION OF DELEGATED ACTS. In the supervision and direction of delegated acts, an RN shall do all of the following:

(a) Delegate tasks commensurate with educational preparation and demonstrated abilities of the person supervised.

(b) Provide direction and assistance to those supervised.

(c) Observe and monitor the activities of those supervised.

(d) Evaluate the effectiveness of acts performed under supervision."

Advanced Practice Registered Nurses

Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRN) are defined by the NCSBN as an RN who has a graduate degree and advanced knowledge. There are four categories of Advanced Practice Registered Nurses: Certified Nurse-Midwife (CNM), Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS), Certified Nurse Practitioner (CNP), and Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA). APRNs can diagnose illnesses and prescribe treatments and medications. Additional information about advanced nursing degrees and roles is provided in the box below.

Advanced Practice Nursing Roles[9]

Nurse Practitioners: Nurse practitioners (NPs) work in a variety of settings and complete physical examinations, diagnose and treat common acute illness and manage chronic illness, order laboratory and diagnostic tests, prescribe medications and other therapies, provide health teaching and supportive counseling with an emphasis on prevention of illness and health maintenance, and refer clients to other health professionals and specialists as needed. In many states, NPs can function independently and manage their own clinics, whereas in other states physician supervision is required. NP certifications include, but are not limited to, Family Practice, Adult-Gerontology Primary Care and Acute Care, and Psychiatric/Mental Health.

To read more about NP certification, visit Nursing World's Our Certifications web page.

Clinical Nurse Specialists: Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNS) practice in a variety of health care environments and participate in mentoring other nurses, case management, research, designing and conducting quality improvement programs, and serving as educators and consultants. Specialty areas include, but are not limited to, Adult/Gerontology, Pediatrics, and Neonatal.

To read more about CNS certification, visit National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialist's What is a CNS? web page.

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists: Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) administer anesthesia and related care before, during, and after surgical, therapeutic, diagnostic, and obstetrical procedures, as well as provide airway management during medical emergencies. CRNAs deliver more than 65 percent of all anesthetics to clients in the United States. Practice settings include operating rooms, dental offices, and outpatient surgical centers.

To read more about CRNA certification, visit National Board of Certification & Recertification for Nurse Anesthetist's website.

Certified Nurse Midwives: Certified Nurse Midwives provide gynecological exams, family planning advice, prenatal care, management of low-risk labor and delivery, and neonatal care. Practice settings include hospitals, birthing centers, community clinics, and client homes.

To read more about CNM certification, visit the American Midwifery Certification Board website.

Unlicensed Assistive Personnel

Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP) are defined by the NCSBN as, “Any unlicensed person, regardless of title, who performs tasks delegated by a nurse. This includes certified nursing aides/assistants (CNAs), patient care assistants (PCAs), patient care technicians (PCTs), state tested nursing assistants (STNAs), nursing assistants-registered (NA/Rs), or certified medication aides/assistants (MA-Cs). Certification of UAPs varies between jurisdictions.”[10]

CNAs, PCAs, and PCTs in Wisconsin generally work in hospitals and long-term care facilities and assist clients with daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, feeding, and toileting. They may also collect client information such as vital signs, weight, and input/output as delegated by the nurse. The RN remains accountable that delegated tasks have been completed and documented by the UAP.

Interprofessional Team Members

Nurses, as the coordinator of a client’s care, continuously review the plan of care to ensure all contributions of the multidisciplinary team are moving the client toward expected outcomes and goals. The roles and contributions of interprofessional health care team members are further described in the following box.

Interprofessional Team Member Roles[11]

Dieticians: Dieticians assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions, including those relating to dietary needs of those clients who need regular or therapeutic diets. They also provide dietary education and work with other members of the health care team when a client has dietary needs secondary to physical disorders such as difficulty swallowing.

Occupational Therapists (OT): Occupational therapists assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions, including those that facilitate the client's ability to achieve their highest possible level of independence in their activities of daily living such as bathing, grooming, eating, and dressing. They also provide clients with adaptive devices such as long shoehorns so the client can put their shoes on, sock pulls so they can independently pull on socks, adaptive silverware to facilitate independent eating, grabbers so the client can pick items up from the floor, and special devices to manipulate buttoning so the person can dress and button their clothing independently. OTs assess the home for safety and the need for assistive devices when the client is discharged home. They may recommend modifications to the home environment such as ramps, grab rails, and handrails to ensure safety and independence. OTs practice in all health care environments, including the home, hospital, and rehabilitation centers.

Pharmacists: Pharmacists ensure the safe prescribing and dispensing of medication and are a vital resource for nurses with questions or concerns about medications they are administering to clients. Pharmacists ensure that clients not only get the correct medication and dosing, but also have the guidance they need to use the medication safely and effectively.

Physical Therapists (PT): Physical therapists are licensed health care professionals who assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions, including those related to the client's functional abilities in terms of their strength, mobility, balance, gait, coordination, and joint range of motion. They supervise prescribed exercise activities according to a client’s condition and also provide and teach clients how to use assistive aids like walkers and canes and how to perform exercise regimens. Physical therapists practice in all health care environments, including the home, hospital, and rehabilitation centers.

Podiatrists: Podiatrists provide care and services to clients who have foot problems. They often work with clients who have diabetes to clip toenails and provide foot care to prevent complications.

Prosthetists: Prosthetists design, fit, and supply the client with an artificial body part such as a leg or arm prosthesis. They adjust prosthesis to ensure proper fit, comfort, and functioning.

Psychologists and Psychiatrists: Psychologists and psychiatrists provide mental health and psychiatric services to clients with mental health disorders and provide psychological support to family members and significant others as indicated.

Respiratory Therapists: Respiratory therapists treat respiratory-related conditions in clients. Their specialized respiratory care includes managing oxygen therapy; drawing arterial blood gases; managing clients on specialized oxygenation devices such as mechanical ventilators, CPAP, and Bi-PAP machines; administering respiratory medications like inhalers and nebulizers; intubating clients; assisting with bronchoscopy and other respiratory-related diagnostic tests; performing pulmonary hygiene measures like chest physiotherapy; and serving an integral role in providing respiratory support.

Social Workers: Social workers counsel clients and provide psychological support, help set up community resources according to clients' financial needs, and serve as part of the team that ensures continuity of care after the person is discharged.

Speech Therapists: Speech therapists assess, diagnose, and treat communication and swallowing disorders. For example, speech therapists help clients with a disorder called expressive aphasia. They also assist clients with using word boards and other electronic devices to facilitate communication. They assess clients with swallowing disorders called dysphagia and treat them in collaboration with other members of the health care team including nurses, dieticians, and health care providers.

Ancillary Department Members: Nurses also work with ancillary departments such as laboratory and radiology departments.

- Clinical laboratory departments provide a wide range of laboratory procedures that aid health care providers to diagnose, treat, and manage clients. These laboratories are staffed by medical technologists who test biological specimens collected from clients. Examples of laboratory tests performed include blood tests, blood banking, cultures, urine tests, and histopathology (changes in tissues caused by disease).[12]

- Radiology departments use imaging to assist providers in diagnosing and treating diseases seen within the body. They perform diagnostic tests such as X-rays, CTs, MRIs, nuclear medicine, PET scans, and ultrasound scans.

Chain of Command

Nurses rarely make client decisions in isolation, but instead consult with other nurses and interprofessional team members. Concerns and questions about client care are typically communicated according to that agency's chain of command. In the military, chain of command refers to a hierarchy of reporting relationships – from the bottom to the top of an organization – regarding who must answer to whom. The chain of command not only establishes accountability, but also lays out lines of authority and decision-making power. The chain of command also applies to health care. For example, a registered nurse in a hospital may consult a “charge nurse,” who may consult the “nurse supervisor,” who may consult the “director of nursing,” who may consult the "vice president of nursing." In a long-term care facility, a licensed practical/vocational nurse typically consults the registered nurse/charge nurse, who may consult with the director of nursing. Nursing students should always consult with their nursing instructor regarding questions or concerns about client care before “going up the chain of command.”

Nurse Specialties

Registered nurses can obtain several types of certifications as a nurse specialist. Certification is the formal recognition of specialized knowledge, skills, and experience demonstrated by the achievement of standards identified by a nursing specialty. See the following box for descriptions of common nurse specialties.

Common Nurse Specialties

Critical Care Nurses provide care to clients with serious, complex, and acute illnesses or injuries that require very close monitoring and extensive medication protocols and therapies. Critical care nurses most often work in intensive care units of hospitals.

Public Health Nurses work to promote and protect the health of populations based on knowledge from nursing, social, and public health sciences. Public health nurses most often work in municipal and state health departments.

Home Health/Hospice Nurses provide a variety of nursing services for chronically ill clients and their caregivers in the home, including end-of-life care.

Occupational/Employee Health Nurses provide health screening, wellness programs and other health teaching, minor treatments, and disease/medication management services to people in the workplace. The focus is on promotion and restoration of health, prevention of illness and injury, and protection from work-related and environmental hazards.

Oncology Nurses care for clients with various types of cancer, administering chemotherapy and providing follow-up care, teaching, and monitoring. Oncology nurses work in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and clients’ homes.

Perioperative/Operating Room Nurses provide preoperative and postoperative care to clients undergoing anesthesia or assist with surgical procedures by selecting and handling instruments, controlling bleeding, and suturing incisions. These nurses work in hospitals and outpatient surgical centers.

Rehabilitation Nurses care for clients with temporary and permanent disabilities within inpatient and outpatient settings such as clinics and home health care.

Psychiatric/Mental Health Nurses specialize in mental and behavioral health problems and provide nursing care to individuals with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric nurses work in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and private offices.

School Nurses provide health assessment, intervention, and follow-up to maintain school compliance with health care policies and ensure the health and safety of staff and students. They administer medications and refer students for additional services when hearing, vision, and other issues become inhibitors to successful learning.

Telenursing refers to providing nursing care remotely using information and communication technology. Nursing care may include client education, support, health assessment and evaluation, and triage. While telenursing is not a specialty, it is provided in several specialty areas such as Critical Care and Emergency Departments. It is also provided in outpatient environments and encourages increased client interactions, especially in underserved rural areas.[13]

Other common specialty areas include a life span approach across health care settings and include maternal-child, neonatal, pediatric, and gerontological nursing.[14]

Damage that occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue.

The healing of a wound that has had to remain open or has been reopened, often due to severe infection.

Legal Considerations

As discussed earlier in this chapter, nurses can be reprimanded or have their licenses revoked for not appropriately following the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are practicing. Nurses can also be held legally liable for negligence, malpractice, or breach of client confidentiality when providing client care.

Negligence and Malpractice

Negligence is a general term that denotes conduct lacking in due care, carelessness, and a deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would use in a particular set of circumstances.[15] Malpractice is a more specific term that looks at a standard of care, as well as the professional status of the caregiver. [16]

To prove negligence or malpractice, the following elements must be established in a court of law[17]:

- Duty owed the client

- Breach of duty owed the client

- Foreseeability

- Causation

- Injury

- Damages

To avoid being sued for negligence or malpractice, it is essential for nurses and nursing students to follow the scope and standards of practice care set forth by their state’s Nurse Practice Act; the American Nurses Association; and employer policies, procedures, and protocols to avoid the risk of losing their nursing license. Examples of a nurse's breach of duty that can be viewed as negligence includes the following:[18]

- Failure to Assess: Nurses should assess for all potential nursing problems/diagnoses, not just those directly affected by the medical disease. For example, all clients should be assessed for fall risk and appropriate fall precautions implemented.

- Insufficient monitoring: Some conditions require frequent monitoring by the nurse, such as risk for falls, suicide risk, confusion, and self-injury.

- Failure to Communicate:

- Lack of documentation: A basic rule of thumb in a court of law is that if an assessment or action was not documented, it is considered not done. Nurses must document all assessments and interventions, in addition to the specific type of client documentation called a nursing care plan.

- Lack of provider notification: Changes in client condition should be urgently communicated to the health care provider based on client status. Documentation of provider notification should include the date, time, and person notified and follow-up actions taken by the nurse.

- Failure to Follow Protocols: Agencies and states have rules for reporting certain behaviors or concerns. For example, a nurse is considered a mandatory reporter by law and required to report suspicion of abuse or neglect of a child based on data gathered during an assessment.

Patient Self Determination Act

The Patient Self Determination Act (PSDA) of 1990 is an amendment made to the Social Security Act that requires health care facilities to inform clients of their right to be involved in their medical care decisions. This law specifically applies to facilities accepting Medicare or Medicaid funding but is considered a right of all clients regardless of their method of reimbursement.

Under the PSDA, clients must also be asked about their advance directives and care wishes. Clients must be provided with teaching about advance directives, appointment of an agent or surrogate in the event they become incapacitated, and their right to self-determination. Conversations about these topics and clients wishes must be documented in the medical record. It is considered an ethical duty of nurses and other health care professionals to ensure clients are aware and understand these healthcare-associated rights.[19]

Informed Consent

Informed consent is written consent voluntarily signed by a client who is competent and understands the terms of the consent without any form of coercion. In the event the client is a minor or deemed incompetent to make their own decisions, a parent or legal guardian signs the informed consent.[20]

Informed consent is crucial for upholding the client's right for self-determination. Informed consent provides documentation signed by the client of their understanding of health care being provided; its benefits, risks, potential complications; reasonable alternatives to treatment; and the right to withdraw consent. It is the health care provider's responsibility to fully discuss the treatment, procedure, or other health care action being proposed that requires consent. The nurse often signs as a witness to the client's signature on the form, affirming that person signed the form. However, it is not the nurse's responsibility or role to provide information. If the client (or their parent/legal guardian) expresses questions, concerns, or lack of understanding, the nurse has an ethical responsibility to notify the provider and advocate for further discussion before signing the form.[21]

In emergency situations where the delay to obtain consent would cause undue harm to the client, verbal or telephone consent may be temporarily obtained that is valid for no more than ten days. Verbal consent and the reason for verbal consent must be documented in the medical record by the provider.[22]

See the following box for examples of situations requiring informed consent in the state of Wisconsin according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Examples of Situations Requiring Informed Consent[23]

- Receipt of medications and/or treatment, including psychotropic medications (unless court-ordered)

- Undergoing customary treatment techniques and procedures

- Participation in experimental research

- Undergoing psychosurgery or other psychological treatment procedures

- Release of treatment records

- Videorecording

- Performance of labor beneficial to the facility

Confidentiality

In addition to negligence and malpractice, confidentiality is a major legal consideration for nurses and nursing students. Patient confidentiality is the right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information, referred to as their protected health information (PHI), protected and known only by those health care team members directly providing care to them. This right is protected by federal regulations called the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA was enacted in 1996 and was prompted by the need to ensure privacy and protection of personal health records and data in an environment of electronic medical records and third-party insurance payers. There are two main sections of HIPAA law, the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule. The Privacy Rule addresses the use and disclosure of individuals' health information. The Security Rule sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information. HIPAA regulations extend beyond medical records and apply to client information shared with others. Therefore, all types of client information should only be shared with health care team members who are actively providing care to them.

How do HIPAA regulations affect you as a student nurse? You are required to adhere to HIPAA guidelines from the moment you begin to provide client care. Nursing students may be disciplined or expelled by their nursing program for violating HIPAA. Nurses who violate HIPAA rules may be fired from their jobs or face lawsuits. See the following box for common types of HIPAA violations and ways to avoid them.

Common HIPAA Violations and Ways to Avoid Them[24]

- Gossiping in the hallways or otherwise talking about clients where other people can hear you. It is understandable that you will be excited about what is happening when you begin working with clients and your desire to discuss interesting things that occur. As a student, you will be able to discuss client care in a confidential manner behind closed doors with your instructor. However, as a health care professional, do not talk about clients in the hallways, elevator, breakroom, or with others who are not directly involved with that client’s care because it is too easy for others to overhear what you are saying.

- Mishandling medical records or leaving medical records unsecured. You can breach HIPAA rules by leaving your computer unlocked for anyone to access or by leaving written client charts in unsecured locations. You should never share your password with anyone else. Make sure that computers are always locked with a password when you step away from them and paper charts are closed and secured in an area where unauthorized people don’t have easy access to them. NEVER take records from a facility or include a client's name on paperwork that leaves the facility.

- Illegally or unauthorized accessing of client files. If someone you know, like a neighbor, coworker, or family member is admitted to the unit you are working on, do not access their medical record unless you are directly caring for them. Facilities have the capability of tracing everything you access within the electronic medical record and holding you accountable. This rule holds true for employees who previously cared for a client as a student; once your shift is over as a student, you should no longer access that client’s medical records.

- Sharing information with unauthorized people. Anytime you share medical information with anyone but the client themselves, you must have written permission to do so. For instance, if a husband comes to you and wants to know his spouse’s lab results, you must have permission from his spouse before you can share that information with him. Just confirming or denying that a client has been admitted to a unit or agency can be considered a breach of confidentiality. Furthermore, voicemails should not be left regarding protected client information.

- Information can generally be shared with the parents of children until they turn 18, although there are exceptions to this rule if the minor child seeks birth control, an abortion, or becomes pregnant. After a child turns 18, information can no longer be shared with the parent unless written permission is provided, even if the minor is living at home and/or the parents are paying for their insurance or health care. As a general rule, any time you are asked for client information, check first to see if the client has granted permission.

- Texting or e-mailing regarding client information on an unencrypted device. Only use properly encrypted devices that have been approved by your health care facility for e-mailing or faxing protected client information. Also, ensure that the information is being sent to the correct person, address, or phone number.

- Sharing information on social media. Never post anything on social media that has anything to do with your clients, the facility where you are working or have clinical, or even how your day went at the agency. Nurses and other professionals have been fired for violating HIPAA rules on social media.[25],[26],[27]

Social Media Guidelines

Nursing students, nurses, and other health care team members must use extreme caution when posting to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and other social media sites. Information related to clients, client care, and/or health care agencies should never be posted on social media; health care team members who violate this guideline can lose their jobs and may face legal action and students can be disciplined or expelled from their nursing program. Be aware that even if you think you are posting in a private group, the information can become public.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) has established the following principles for nurses using social media:[28]

- Nurses must not transmit or place online individually identifiable client information.

- Nurses must observe ethically prescribed professional client-nurse boundaries.

- Nurses should understand that clients, colleagues, organizations, and employers may view postings.

- Nurses should take advantage of privacy settings and seek to separate personal and professional information online.

- Nurses should bring content that could harm a client’s privacy, rights, or welfare to the attention of appropriate authorities.

- Nurses should participate in developing organizational policies governing online conduct.

In addition to these principles, the ANA has also provided these tips for nurses and nursing students using social media:[29]

- Remember that standards of professionalism are the same online as in any other circumstance.

- Do not share or post information or photos gained through the nurse-client relationship.

- Maintain professional boundaries in the use of electronic media. Online contact with clients blurs this boundary.

- Do not make disparaging remarks about clients, employers, or coworkers, even if they are not identified.

- Do not take photos or videos of clients on personal devices, including cell phones.

- Promptly report a breach of confidentiality or privacy.

Read more about the ANA's Social Media Principles.

Code of Ethics

In addition to legal considerations, there are also several ethical guidelines for nursing care.

There is a difference between morality, ethical principles, and a code of ethics. Morality refers to “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals within communities and societies.”[30] An ethical principle is a general guide, basic truth, or assumption that can be used with clinical judgment to determine a course of action. Four common ethical principles are beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), autonomy (control by the individual), and justice (fairness). A code of ethics is set for a profession and makes their primary obligations, values, and ideals explicit.

The American Nursing Association (ANA) guides nursing practice with the Code of Ethics for Nurses.[31] This code provides a framework for ethical nursing care and a guide for decision-making. The Code of Ethics for Nurses serves the following purposes:

- It is a succinct statement of the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively.

- It is the profession’s nonnegotiable ethical standard.

- It is an expression of nursing’s own understanding of its commitment to society.[32]

The ANA Code of Ethics contains nine provisions. See a brief description of each provision in the following box.

Provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics[33]

The nine provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics are briefly described below. The full code is available to read for free at Nursingworld.org.

Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

Provision 2: The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.

Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

The ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights

In addition to publishing the Code of Ethics, the ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights was established to help nurses navigate ethical and value conflicts and life-and-death decisions, many of which are common to everyday practice.

Check your knowledge with the following questions:

Safety: A Basic Need

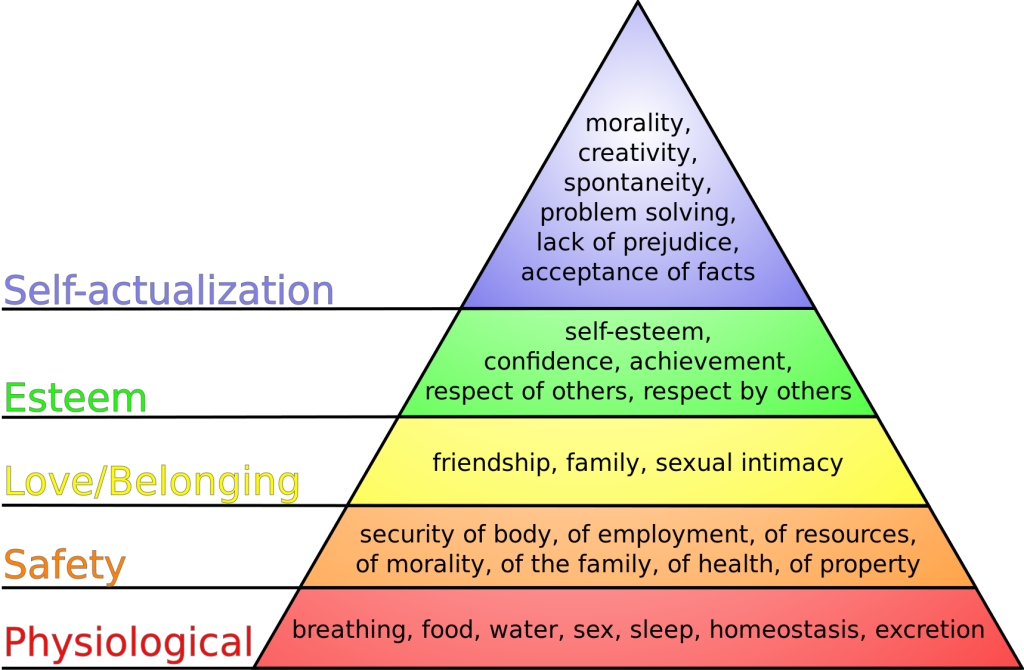

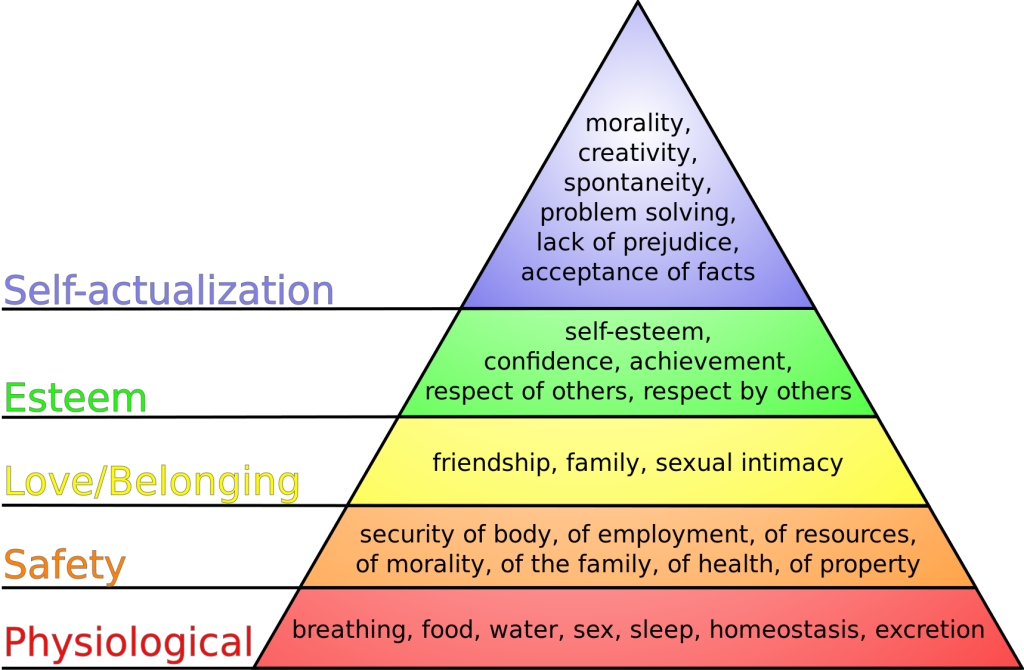

Safety is a basic foundational human need and always receives priority in client care. Nurses typically use Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to prioritize urgent client needs, with the bottom two rows of the pyramid receiving top priority. See Figure 5.1[34] for an image of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Safety is intertwined with basic physiological needs.

Consider the following scenario: You are driving back from a relaxing weekend at the lake and come upon a fiery car crash. You run over to the car to help anyone inside. When you get to the scene, you notice that the lone person in the car is not breathing. Your first priority is not to initiate rescue breathing inside the burning car, but to move the person to a safe place where you can safely provide CPR.

In nursing, the concept of client safety is central to everything we do in all health care settings. As a nurse, you play a critical role in promoting client safety while providing care. You also teach clients and their caregivers how to prevent injuries and remain safe in their homes and in the community. Safe client care also includes measures to keep you safe in the health care environment; if you become ill or injured, you will not be able to effectively care for others.

Safe client care is a commitment to providing the best possible care to every client and their caregivers in every moment of every day. Clients come to health care facilities expecting to be kept safe while they are treated for illnesses and injuries. Unfortunately, you may have heard stories about situations when that did not happen. Medical errors can be devastating to clients and their families. Consider the true story in the following box that illustrates factors affecting client safety.

The Josie King Story

In 2001, 18-month-old Josie King died as a result of medical errors in a well-known hospital from a hospital-acquired infection and an incorrectly administered pain medication. How did this preventable death happen? Watch this video of her mother, Sorrel King, telling Josie’s story and explaining how Josie’s death spurred her work on improving client safety in hospitals everywhere.[35]

Reflective Questions:

- What factors contributed to Josie’s death?

- How could these factors be resolved?

Never Events

The event described in the Josie King story is considered a “never event.” Never events are adverse events that are clearly identifiable, measurable, serious (resulting in death or significant disability), and preventable. In 2007 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) discontinued payment for costs associated with never events, and this policy has been adopted by most private insurance companies. Never events are publicly reported, with the goal of increasing accountability by health care agencies and improving the quality of client care. The current list of never events includes seven categories of events:

- Surgical or procedural event, such as surgery performed on the wrong body part

- Product or device, such as injury or death from a contaminated drug or device

- Client protection, such as client suicide in a health care setting

- Care management, such as death or injury from a medication error

- Environmental, such as death or injury as the result of using restraints

- Radiologic, such as a metallic object in an MRI area

- Criminal, such as death or injury of a client or staff member resulting from physical assault on the grounds of a health care setting

Sentinel Events

Sentinel events are very similar to never events although they may not be entirely preventable. They are defined by The Joint Commission as an “A client safety event that reaches a client and results in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm requiring interventions to sustain life." Such events are called "sentinel" because they signal the need for immediate investigation and response. Each accredited organization is strongly encouraged, but not required, to report sentinel events to The Joint Commission.[36] It is helpful to facilities to self-report sentinel events so that other facilities can learn from these events and future sentinel events can be prevented through knowledge sharing and risk reduction. Investigations into sentinel events are typically achieved through a process called root cause analysis.

Root cause analysis is a structured method used to analyze serious adverse events to identify underlying problems that increase the likelihood of errors, while avoiding the trap of focusing on mistakes by individuals. A multidisciplinary team analyzes the sequence of events leading up to the error with the goal of identifying how and why the event occurred. The ultimate goal of root cause analysis is to prevent future harm by eliminating hidden problems within a health care system that contribute to adverse events. For example, when a medication error occurs, a root cause analysis goes beyond focusing on the mistake by the nurse and looks at other system factors that contributed to the error, such as similar-looking drug labels, placement of similar-looking medications next to each other in a medication dispensing machine, or vague instructions in a provider order.

Root cause analysis uses human factors science as part of the investigation. Human factors focus on the interrelationships among humans, the tools and equipment they use in the workplace, and the environment in which they work. Safety in health care is ultimately dependent on humans - the doctors, nurses, and health care professionals - providing the care.

Near Misses