16.5 Metabolism

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Metabolism

After a drug has been absorbed and distributed throughout the body, it is broken down by a process known as metabolism so that it can be excreted from the body. Drugs undergo chemical alteration by various body systems to create compounds that are more easily excreted.

As previously discussed in this chapter, medications that are swallowed or otherwise administered into the gastrointestinal tract are inactivated by the intestines and liver, known as the first-pass effect. Additionally, everything that enters the bloodstream, whether swallowed, injected, inhaled, absorbed through the skin, or produced by the body itself, is metabolized by the liver. See Figure 1.5[1] for an image of the liver. These chemical alterations are known as biotransformations. The biotransformations that take place in the liver are performed by liver enzymes.

Biotransformations occur by mechanisms categorized as either Phase I (modification), Phase II (conjugation), and in some instances, Phase III (additional modification and excretion.)[2]

Phase I biotransformations alter the chemical structure of the drug. Many of the products of enzymatic breakdown, called metabolites, are less chemically active than the original molecule. For this reason, the liver is referred to as a “detoxifying” organ. An example of a Phase I biotransformation is when diazepam, a medication prescribed for anxiety, is transformed into desmethyldiazepam and then to oxazepam. Both these metabolites produce similar physiological and psychological effects of diazepam.[3]

In some instances, Phase I biotransformations change an inactive drug into an active form called a “prodrug.” Prodrugs improve a medication’s effectiveness. They may also be designed to avoid certain side effects or toxicities. For example, sulfasalazine is a medication prescribed for rheumatoid arthritis. It is prodrug that is not active in its ingested form but becomes active after Phase I modification.

Phase II biotransformations involve reactions that couple the drug molecule with another molecule in a process called conjugation. Conjugation typically renders the compound pharmacologically inert and water-soluble so it can be easily excreted. These processes can occur in the liver, kidney, lungs, intestines, and other organ systems. An example of Phase II metabolism is when oxazepam, the active metabolite of diazepam, is conjugated with a molecule called glucuronide so that it becomes physiologically inactive and is excreted without further chemical modification.[4]

Following Phase II metabolism, Phase III biotransformations may also occur, where the conjugates and metabolites are excreted from cells.[5]

Factors Affecting Metabolism

Critical factors in drug metabolism are the type and concentration of liver enzymes. The most important enzymes for medical purposes are monoamine oxidase and cytochrome P450. These two enzymes are responsible for metabolizing dozens of chemicals.[6]

Drug metabolism can be influenced by a number of factors. One major disruptor of drug metabolism is depot binding. Depot binding is the coupling of drug molecules with inactive sites in the body, resulting in the drug not being accessible for metabolism. This action can also affect the duration of action of other medications susceptible to depot binding. For example, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive component of marijuana, is highly lipid-soluble and depot binds in the adipose tissue of users. This interaction drastically slows the metabolism of the drug, so metabolites of THC can be detected in urine weeks after the last use.[7]

Another factor in drug metabolism is enzyme induction. Enzymes are induced by repeated use of the same drug. The body becomes accustomed to the constant presence of the drug and compensates by increasing the production of the enzyme necessary for the drug’s metabolism. This contributes to a condition referred to as tolerance and causes clients to require ever-increasing doses of certain drugs to produce the same effect. For example, clients who take opioid analgesics over a long period of time will notice that their medication becomes less effective over time.[8]

In contrast, some drugs have an inhibitory effect on enzymes, making the client more sensitive to other medications metabolized through the action of those enzymes. For example, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are prescribed as antidepressants because they block monoamine oxidase, the enzyme that breaks down serotonin and dopamine, thus increasing the concentration of these chemicals in the central nervous system. However, this can cause problems when clients taking an MAOI also take other medications that increase the levels of these chemicals, such as dextromethorphan found in cough syrup.[9]

Additionally, drugs that share metabolic pathways can “compete” for the same binding sites on enzymes, thus decreasing the efficiency of their metabolism. For example, alcohol and some sedatives are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme and only a limited number of these enzymes exist to break these drugs down. Therefore, if a client takes a sedative after drinking alcohol, the sedative is not well-metabolized because most of cytochrome P450 enzymes are filled by alcohol molecules. This results in reduced excretion and high levels of both drugs in the body with enhanced effects. For this reason, the co-administration of alcohol and sedatives can be deadly.

Clinical Significance

When administering medication, nurses must know how and when the medication is metabolized and eliminated from the body. Most of the time, the rate of elimination of a drug depends on the concentration of the drug in the bloodstream. However, the elimination of some drugs occurs at a constant rate that is independent of plasma concentrations. For example, the ethanol contained in alcoholic beverages is eliminated at a constant rate of about 15 mL/hour regardless of the concentration in the bloodstream.[10]

Half Life

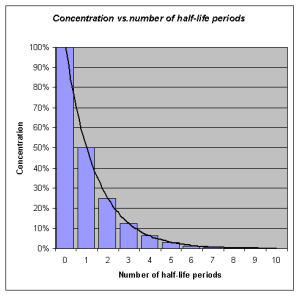

Half-life refers to the rate at which 50% of a drug is eliminated from the body. Half-life can vary significantly between drugs. Some drugs have a short half-life of only a few hours and must be given multiple times a day, whereas other drugs have half-lives exceeding 12 hours and can be given as a single dose every 24 hours. See Figure 1.6[11] for an illustration of half-life affecting the blood concentration of medication over time.

Half-life affects the duration of the therapeutic effect of a medication. Many factors can influence half-life. For example, liver disease can prolong half-life if it is no longer effectively metabolizing the medication. Information about half-life of a specific medication can be found in evidence-based medication references. For example, in the “Clinical Pharmacology” section of the DailyMed reference for furosemide, the half-life is approximately two hours.

Depending on whether a drug is metabolized and eliminated by the kidneys or liver, impairment in either of these systems can significantly alter medication dosing, frequency of doses, anticipated therapeutic effect, and even whether a particular medication can be used at all. Nurses must work with other members of the health care team to prevent drug interactions that could significantly affect a client’s health and well-being. Nurses must be alert for signs of a toxic buildup of metabolites or active drugs, particularly if the client has liver or kidney disease, so that they can alert the health care provider. In other cases, drugs such as warfarin and certain antibiotics are dosed and monitored by pharmacists, who monitor serum levels of the drugs, as well as kidney function.

Life Span Considerations

Neonate & Pediatric

The developing liver in infants and young children produces decreased levels of enzymes. This may result in a decreased ability of the young child or neonate to metabolize medications. In contrast, older children may experience increased metabolism and require higher doses of medications once the hepatic enzymes are fully produced.[12]

Older Adult

Metabolism by the liver may significantly decline in the older adult. As a result, dosages should be adjusted according to the client’s liver function and their anticipated metabolic rate. First-pass metabolism also decreases with aging, so older adults may have higher “free” circulating drug concentrations and thus be at higher risk for side effects and toxicities.[13]

Critical Thinking Activity 1.5

Metabolism can be influenced by many factors within the body. If a client has liver damage, they may not be able to breakdown (metabolize) medications as efficiently. Dosages are calculated according to the liver’s ability to metabolize and the kidney’s ability to excrete.

When caring for a client with cirrhosis, how can this condition impact the dosages prescribed?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Did You Know?

Did you know that, in some people, a single glass of grapefruit juice can alter levels of drugs used to treat allergies, heart diseases, and infections? Fifteen years ago, pharmacologists discovered this “grapefruit juice effect” by luck, after giving volunteers grapefruit juice to mask the taste of a medicine. Nearly a decade later, researchers figured out that grapefruit juice affects the metabolizing rates of some medicines by lowering levels of a drug-metabolizing enzyme called CYP3A4 (part of the CYP450 family of drug-binding enzymes) in the intestines.

Paul B. Watkins of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill discovered that other juices like Seville (sour) orange juice—but not regular orange juice—have the same effect on the liver’s ability to metabolize using enzymes. Each of ten people who volunteered for Watkins’ juice-medicine study took a standard dose of felodopine, a drug used to treat high blood pressure, diluted in grapefruit juice, sour orange juice, or plain orange juice. The researchers measured blood levels of felodopine at various times afterward. The team observed that both grapefruit juice and sour orange juice increased blood levels of felodopine, as if the people had received a higher dose. Regular orange juice had no effect. Watkins and his coworkers have found that a chemical common to grapefruit and sour oranges, dihydroxybergamottin, is likely the molecular culprit. Thus, when taking medications that use the CYP3A4 enzyme to metabolize, clients are advised to avoid grapefruit juice and sour orange juice.[14]

- “Liver Hepatic Organ Jaundice Bile Fatty Liver - Liver” by VSRao is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Susa, Hussain, and Preuss and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Concentration_vs_number_of_half-life_periodes.png” by OPPSD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Fernandez, E., Perez, R., Hernandez, A., Tejada, P., Arteta, M., & Ramos, J. T. (2011). Factors and mechanisms for pharmacokinetic differences between pediatric population and adults. Pharmaceutics, 3(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics3010053 ↵

- Fernandez, E., Perez, R., Hernandez, A., Tejada, P., Arteta, M., & Ramos, J. T. (2011). Factors and mechanisms for pharmacokinetic differences between pediatric population and adults. Pharmaceutics, 3(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics3010053 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medicines by Design by US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences and is available in the Public Domain. ↵

Before learning about how to care for clients with fluid and electrolyte imbalances, it is important to understand the physiological processes of the body’s regulatory mechanisms. The body is in a constant state of change as fluids and electrolytes are shifted in and out of cells within the body in an attempt to maintain a nearly perfect balance. A slight change in either direction can have significant consequences on various body systems.

Body Fluids

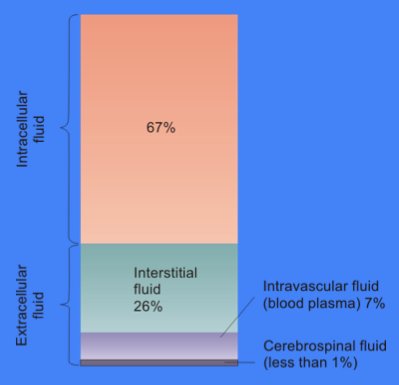

Body fluids consist of water, electrolytes, blood plasma and component cells, proteins, and other soluble particles called solutes. Body fluids are found in two main areas of the body called intracellular and extracellular compartments. See Figure 15.1[1] for an illustration of intracellular and extracellular compartments.

Intracellular fluids (ICF) are found inside cells and are made up of protein, water, electrolytes, and solutes. The most abundant electrolyte in intracellular fluid is potassium. Intracellular fluids are crucial to the body’s functioning. In fact, intracellular fluid accounts for 60% of the volume of body fluids and 40% of a person’s total body weight![2]

Extracellular fluids (ECF) are fluids found outside of cells. The most abundant electrolyte in extracellular fluid is sodium. The body regulates sodium levels to control the movement of water into and out of the extracellular space due to osmosis.

Extracellular fluids can be further broken down into various types. The first type is known as intravascular fluid found in the vascular system and consists of arteries, veins, and capillary networks. Intravascular fluid is whole blood volume and includes red blood cells, white blood cells, plasma, and platelets. Intravascular fluid is the most important component of the body’s overall fluid balance.

Loss of intravascular fluids causes the nursing diagnosis Deficient Fluid Volume, also referred to as hypovolemia. Intravascular fluid loss can be caused by several factors, such as excessive diuretic use, severe bleeding, vomiting, diarrhea, and inadequate oral fluid intake. If intravascular fluid loss is severe, the body cannot maintain adequate blood pressure and perfusion of vital organs. This can result in hypovolemic shock and cellular death when critical organs do not receive an oxygen-rich blood supply needed to perform cellular function.

A second type of extracellular fluid is interstitial fluid. Interstitial fluid refers to fluid outside of blood vessels and between the cells. For example, if you have ever cared for a client with heart failure and noticed increased swelling in the feet and ankles, you have seen an example of excess interstitial fluid referred to as edema.

The remaining extracellular fluid, also called transcellular fluid, refers to fluid in areas such as cerebrospinal, synovial, intrapleural, and the gastrointestinal system.[3]

Fluid Movement

Fluid movement occurs inside the body due to osmotic pressure, hydrostatic pressure, and osmosis. Proper fluid movement depends on intact and properly functioning vascular tissue lining, normal levels of protein content within the blood, and adequate hydrostatic pressures inside the blood vessels. Intact vascular tissue lining prevents fluid from leaking out of the blood vessels. Protein content of the blood (in the form of albumin) causes oncotic pressure that holds water inside the vascular compartment. For example, clients with decreased protein levels (i.e., low serum albumin) experience edema due to the leakage of intravascular fluid into interstitial areas because of decreased oncotic pressure.

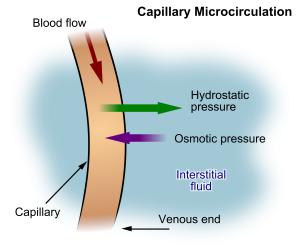

Hydrostatic pressure is defined as pressure that a contained fluid exerts on what is confining it. In the intravascular fluid compartment, hydrostatic pressure is the pressure exerted by blood against the capillaries. Hydrostatic pressure opposes oncotic pressure at the arterial end of capillaries, where it pushes fluid and solutes out into the interstitial compartment. On the venous end of the capillary, hydrostatic pressure is reduced, which allows oncotic pressure to pull fluids and solutes back into the capillary.[4],[5] See Figure 15.2[6] for an illustration of hydrostatic pressure and oncotic pressure in a capillary.

Filtration occurs when hydrostatic pressure pushes fluids and solutes through a permeable membrane so they can be excreted. An example of this process is fluid and waste filtration through the glomerular capillaries in the kidneys. This filtration process within the kidneys allows excess fluid and waste products to be excreted from the body in the form of urine.

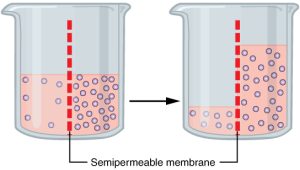

Fluid movement is also controlled through osmosis. Osmosis is water movement through a semipermeable membrane, from an area of lesser solute concentration to an area of greater solute concentration, in an attempt to equalize the solute concentrations on either side of the membrane. Only fluids and some particles dissolved in the fluid are able to pass through a semipermeable membrane; larger particles are blocked from getting through. Because osmosis causes fluid to travel due to a concentration gradient and no energy is expended during the process, it is referred to as passive transport.[7] See Figure 15.3[8] for an illustration of osmosis where water has moved to the right side of the membrane to equalize the concentration of solutes on that side with the left side.

Osmosis causes fluid movement between the intravascular, interstitial, and intracellular fluid compartments based on solute concentration. For example, recall a time when you have eaten a large amount of salty foods. The sodium concentration of the blood becomes elevated. Due to the elevated solute concentration within the bloodstream, osmosis causes fluid to be pulled into the intravascular compartment from the interstitial and intracellular compartments to try to equalize the solute concentration. As fluid leaves the cells, they shrink in size. The shrinkage of cells is what causes many symptoms of dehydration, such as dry, sticky mucous membranes. Because the brain cells are especially susceptible to fluid movement due to osmosis, a headache may occur if adequate fluid intake does not occur.

Solute Movement

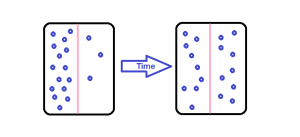

Solute movement is controlled by diffusion, active transport, and filtration. Diffusion is the movement of molecules from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration to equalize the concentration of solutes throughout an area. (Note that diffusion is different from osmosis because osmosis is the movement of fluid whereas diffusion is the movement of solutes.) See Figure 15.4[9] for an image of diffusion. Because diffusion travels down a concentration gradient, the solutes move freely without energy expenditure. An example of diffusion is the movement of inhaled oxygen molecules from alveoli to the capillaries in the lungs so that they can be distributed throughout the body.

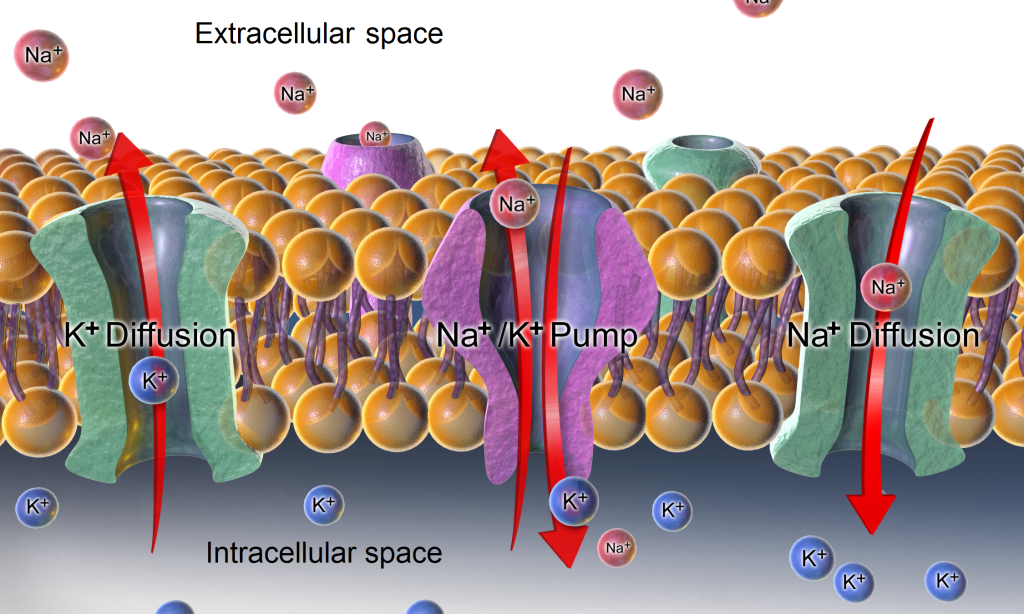

Active transport, unlike diffusion, involves moving solutes and ions across a cell membrane from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration. Because active transport moves solutes against a concentration gradient to prevent an overaccumulation of solutes in an area, energy is required for this process to take place.[10] An example of active transport is the sodium-potassium pump, which uses energy to maintain higher levels of sodium in the extracellular fluid and higher levels of potassium in the intracellular fluid. See Figure 15.5[11] for an image of diffusion and the sodium-potassium pump regulating sodium and potassium levels in the extracellular and intracellular compartments. Recall that sodium (Na+) is the primary electrolyte in the extracellular space and potassium (K+) is the primary electrolyte in the intracellular space.

Fluid and Electrolyte Regulation

The body must carefully regulate intravascular fluid accumulation and excretion to prevent fluid volume excesses or deficits and maintain adequate blood pressure. Water balance is regulated by several mechanisms including antidiuretic hormone (ADH), thirst, and the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS).

Fluid intake is regulated by thirst. As fluid is lost and the sodium level increases in the intravascular space, serum osmolality increases. Serum osmolality is a measure of the concentration of dissolved solutes in the blood. Osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus sense increased serum osmolarity levels and trigger the release of ADH (antidiuretic hormone) in the kidneys to retain fluid. The osmoreceptors also produce the feeling of thirst to stimulate increased fluid intake. However, individuals must be able to mentally and physically respond to thirst signals to increase their oral intake. They must be alert, fluids must be accessible, and the person must be strong enough to reach for fluids. When a person is unable to respond to thirst signals, dehydration occurs. Older individuals are at increased risk of dehydration due to age-related impairment in thirst perception. The average adult intake of fluids is about 2,500 mL per day from both food and drink. An increased amount of fluids is needed if the client has other medical conditions causing excessive fluid loss, such as sweating, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and bleeding.

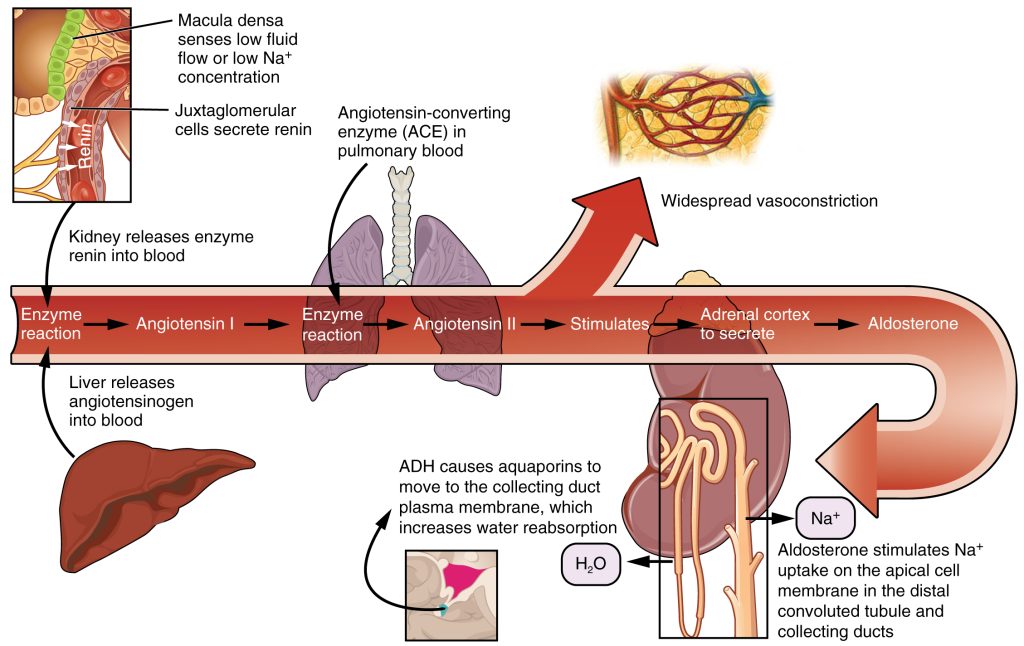

The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) plays an important role in regulating fluid output and blood pressure. See Figure 15.6[12] for an illustration of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS). When there is decreased blood pressure (which can be caused by fluid loss), specialized kidney cells make and secrete renin into the bloodstream. Renin acts on angiotensinogen released by the liver and converts it to angiotensin I, which is then converted to angiotensin II. Angiotensin II does a few important things. First, angiotensin II causes vasoconstriction to increase blood flow to vital organs. It also stimulates the adrenal cortex to release aldosterone. Aldosterone is a steroid hormone that triggers increased sodium reabsorption by the kidneys and subsequent increased serum osmolality in the bloodstream. As you recall, increased serum osmolality causes osmosis to move fluid into the intravascular compartment in an effort to equalize solute particles. The increased fluids in the intravascular compartment increase circulating blood volume and help raise the person’s blood pressure. An easy way to remember this physiological process is “aldosterone saves salt” and “water follows salt.”[13]

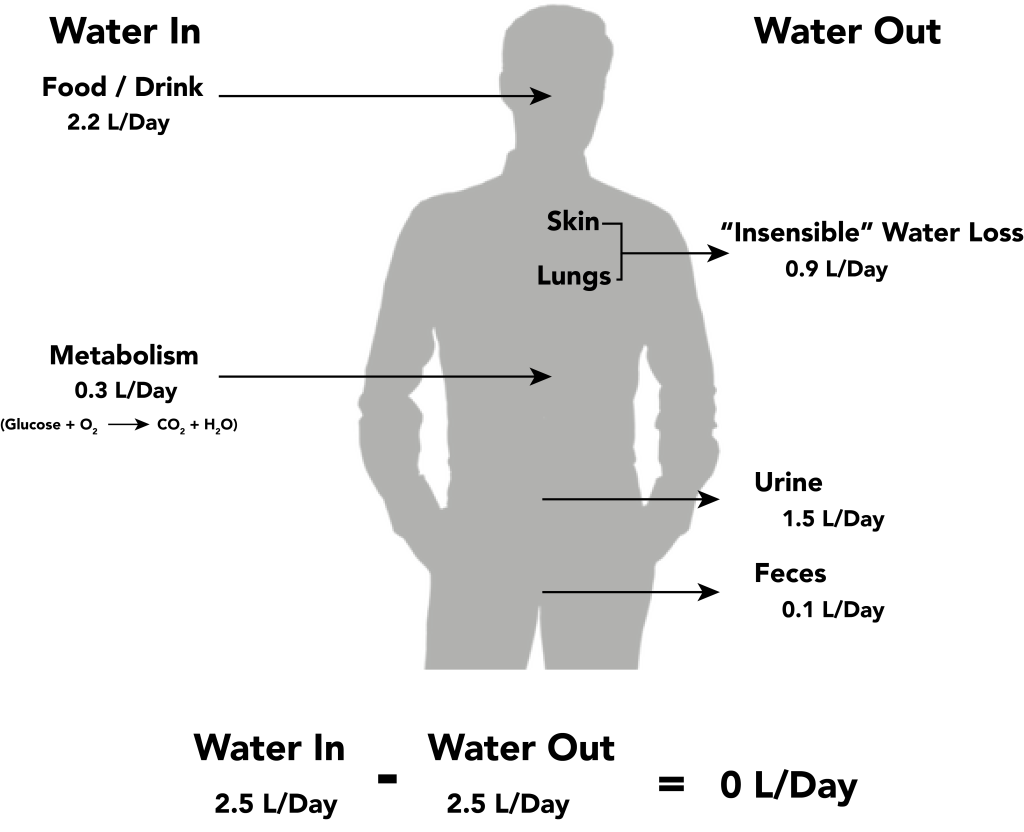

Fluid output occurs mostly through the kidneys in the form of urine. Fluid is also lost through the skin as perspiration, through the gastrointestinal tract in the form of stool, and through the lungs during respiration. Forty percent of daily fluid output occurs due to these “insensible losses” through the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs and cannot be measured. The remaining 60% of daily fluid output is in the form of urine. Normally, the kidneys produce about 1,500 mL of urine per day when fluid intake is adequate. Decreased urine production is an early sign of dehydration or kidney dysfunction. It is important for nurses to assess urine output in clients at risk. If a client demonstrates less than 30 mL/hour (or 0.5 mL/kg/hour) of urine output over eight hours, the provider should be notified for prompt intervention. See Figure 15.7[14] for an illustration of an average adult’s daily water balance of 2,500 mL fluid intake balanced with 2,500 mL fluid output.

Fluid Imbalance

Two types of fluid imbalances are excessive fluid volume (also referred to as hypervolemia) and deficient fluid volume (also referred to as hypovolemia). These imbalances primarily refer to imbalances in the extracellular compartment but can cause fluid movement in the intracellular compartments based on the sodium level of the blood.

Excessive Fluid Volume

Excessive fluid volume (also referred to as hypervolemia) occurs when there is increased fluid retained in the intravascular compartment. Clients at risk for developing excessive fluid volume are those with the following conditions:

- Heart Failure

- Kidney Failure

- Cirrhosis

- Pregnancy[15]

Symptoms of fluid overload include pitting edema, ascites, and dyspnea and crackles from fluid in the lungs. Edema is swelling in dependent tissues due to fluid accumulation in the interstitial spaces. Ascites is fluid retained in the abdomen.

Treatment depends on the cause of the fluid retention. Sodium and fluids are typically restricted, and diuretics are often prescribed to eliminate the excess fluid. For more information about the nursing care of clients with excessive fluid volume, see the “Applying the Nursing Process” section.

Deficient Fluid Volume

Deficient fluid volume (also referred to as hypovolemia or dehydration) occurs when loss of fluid is greater than fluid input. Common causes of deficient fluid volume are diarrhea, vomiting, excessive sweating, fever, and poor oral fluid intake. Individuals who have a higher risk of dehydration include the following:

- Older adults

- Infants and children

- Clients with chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and kidney disease

- Clients taking diuretics and other medications that cause increased urine output

- Individuals who exercise or work outdoors in hot weather[16]

In adults, symptoms of dehydration are as follows:

- Feeling very thirsty

- Dry mouth

- Headache

- Dry skin

- Urinating and sweating less than usual

- Dark, concentrated urine

- Feeling tired

- Changes in mental status

- Dizziness due to decreased blood pressure

- Elevated heart rate[17]

In infants and young children, additional symptoms of dehydration include the following:

- Crying without tears

- No wet diapers for three hours or more

- Being unusually sleepy or drowsy

- Irritability

- Eyes that look sunken

- Sunken fontanel[18]

Dehydration can be mild and treated with increased oral intake such as water or sports drinks. Severe cases can be life-threatening and require the administration of intravenous fluids.

For more information about water balance and fluid movement, review the following video.