9.4 Evidence-Based Practice and Research

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

There are many ties between safe, quality patient-centered care; evidence-based practice; research; and quality improvement. These concepts fall under the umbrella term “scholarly inquiry.” All nurses should be involved in scholarly inquiry related to their nursing practice, no matter what agency they work. The American Nursing Association (ANA) Standard of Professional Performance called Scholarly Inquiry lists competencies related to incorporating evidence-based practice and research for all nurses. See the following box for a list of these competencies.[1]

Competencies of ANA’s Scholarly Inquiry Standard of Professional Performance[2]

- Identifies questions in the health care or practice setting that can be answered by scholarly inquiry.

- Uses current evidence-based knowledge, combined with clinical expertise and health care consumer values and preferences, to guide practice in all settings.

- Participates in the formulation of evidence-based practice.

- Uses evidence to expand knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgement; to enhance role performance; and to increase knowledge of professional issues for themselves and others.

- Shares peer-reviewed, evidence-based findings with colleagues to integrate knowledge into nursing practice.

- Incorporates evidence and nursing research when initiating changes and improving quality in nursing practice.

- Articulates the value of research and scholarly inquiry and their application to one’s practice and health care setting.

- Promotes ethical principles of research in practice and the health care setting.

- Reviews nursing research for application in practice and the health care setting.

Reflective Questions

- What Scholarly Inquiry competencies have you already demonstrated during your nursing education?

- What Scholarly Inquiry competencies are you most interested in mastering?

- What questions do you have about the ANA’s Scholarly Inquiry competencies?

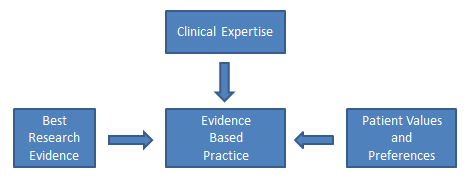

Nursing practice should be based on solid evidence that guides care and ensures quality. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the foundation for providing effective and efficient health care that promotes improved patient outcomes. Evidence-based practice is defined by the American Nurses Association as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and patient, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[3] See Figure 9.7[4] for an illustration of evidence-based practice.

Evidence-based practice is the foundation nurses rely on to ensure their interventions, policies, and procedures are based on data supporting positive patient outcomes. EBP relies on scholarly research that generates new nursing knowledge, as well as quality improvement processes that review patient outcomes resulting from current nursing practice, to continually improve quality care. EBP encourages health care team members to incorporate new research findings into their practice, referred to as translating evidence into practice. Nurses must recognize the partnership between EBP and research; EBP cannot exist without continual scholarly research, and research requires nurses to evaluate research findings and incorporate them into their practice.[5]

Read examples of nursing evidence-based projects from Johns Hopkins.

Newly graduated nurses may become immediately involved with evidence-based practice and quality improvement processes. The Quality and Safety Education (QSEN) project further elaborates on evidence-based practice for entry-level nurses with the definition of EBP as, “integrating best current evidence with clinical expertise and patient/family preferences and values for delivery of optimal health care.” See Table 9.4 for the knowledge, skills, and attitudes associated with the QSEN competency of evidence-based practice for entry-level nurses.

Table 9.4. QSEN: Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Associated With Evidence-Based Practice

| Knowledge | Skills | Attitudes |

|---|---|---|

| Demonstrate knowledge of basic scientific methods and processes.

Describe EBP to include the components of research evidence, clinical expertise, and patient/family values. |

Participate effectively in appropriate data collection and other research activities.

Adhere to Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines. Base individualized care plan on patient values, clinical expertise, and evidence. |

Appreciate strengths and weaknesses of scientific bases for practice.

Value the need for ethical conduct of research and quality improvement. Value the concept of EBP as integral to determining best clinical practice. |

| Differentiate clinical opinion from research and evidence summaries.

Describe reliable sources for locating evidence reports and clinical practice guidelines. |

Read original research and evidence reports related to area of practice.

Locate evidence reports related to clinical practice topics and guidelines. |

Appreciate the importance of regularly reading relevant professional journals. |

| Explain the role of evidence in determining best clinical practice.

Describe how the strength and relevance of available evidence influences the choice of interventions in provision of patient-centered care. |

Participate in structuring the work environment to facilitate integration of new evidence into standards of practice.

Question rationale for routine approaches to care that result in less-than-desired outcomes or adverse events. |

Value the need for continuous improvement in clinical practice based on new knowledge. |

| Discriminate between valid and invalid reasons for modifying evidence-based clinical practice based on clinical expertise or patient/family preferences. | Consult with clinical experts before deciding to deviate from evidence-based protocols. | Acknowledge own limitations in knowledge and clinical expertise before determining when to deviate from evidence-based best practices. |

Reflective Questions: Read through the knowledge, skills, and attitudes in Table 9.4.

- How are you currently integrating evidence-based practice when providing patient care?

- Where do you find information on current evidence-based practice?

- Have you witnessed any routine approaches to care that resulted in less-than-desired outcomes or adverse events?

- What else would you like to learn about evidence-based nursing practice?

Keeping Current on Evidence-Based Practices

Health care is constantly evolving with new technologies and new evidence-based practices. Nurses must dedicate themselves to being lifelong learners. After graduating from nursing school, it is important to remain current on evidence-based practices. Many employers subscribe to electronic evidence-based clinical tools that nurses and other health care team members can access at the bedside. Nurses also independently stay up-to-date on current evidence-based practice by reading nursing journals; attending national, state, and local nursing conferences; and completing continuing education courses. See the box below for examples of ways to remain current on evidence-based practices.

Examples of Evidence-Based Clinical Supports, Nursing Journals, and Conferences

Research

Earlier in this chapter we discussed the process of quality improvement and the manner in which it is used to evaluate current nursing practice by determining where gaps exist and what improvements can be made. Nursing research is a different process than QI. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines nursing research as, “Systematic inquiry designed to develop knowledge about issues of importance to the nursing professions.”[6] The purpose of nursing research is to advance nursing practice through the discovery of new information. It is also used to provide scholarly evidence regarding improved patient outcomes resulting from evidence-based nursing interventions.

Nursing research is guided by a systematic, scientific approach. Research consists of reviewing current literature for recurring themes and evidence, defining terms and current concepts, defining the population of interest for the research study, developing or identifying tools for collecting data, collecting and analyzing the data, and making recommendations for nursing practice. As you can see, the scholarly process of nursing research is more complex than the Plan, Do, Study, Act process of QI and typically requires more time and resources to complete.[7]

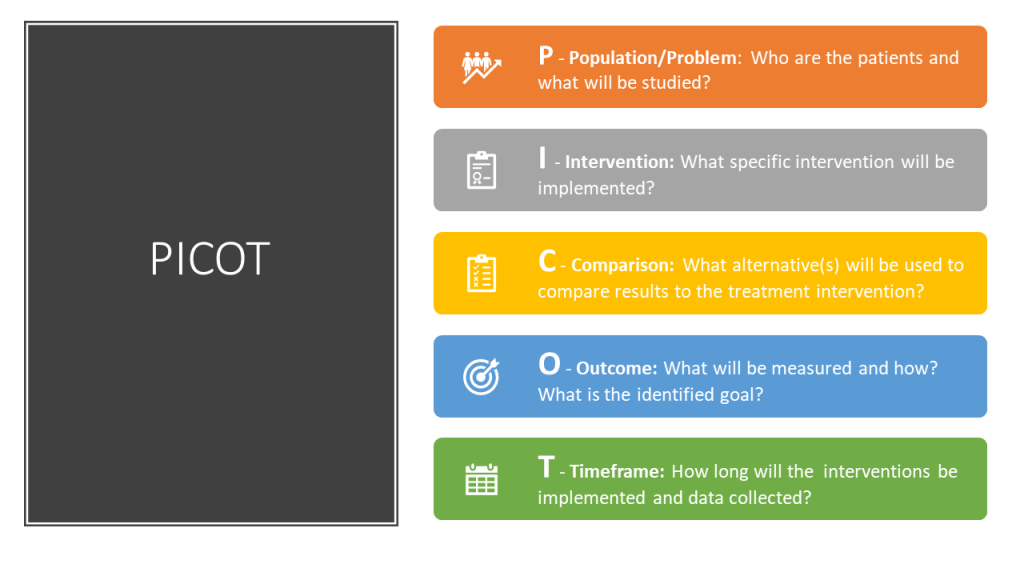

Nurse researchers often use the PICOT format to organize the overall goals of the research project. The PICOT mnemonic assists nurses in answering the clinical question to be studied.[8] See Figure 9.8[9] for an image of PICOT.

P: Population/Problem: Who are the patients that will be studied (e.g., age, race, gender, disease, or health status, etc.) and what problem is being addressed (e.g., mortality, morbidity, compliance, satisfaction, etc.)?

I: Intervention: What is the specific intervention to be implemented with the research population (e.g., therapy, education, medication, etc.)?

C: Comparison: What is the alternative intervention that will be used to compare to the treatment intervention (e.g., placebo, no intervention, different medication, etc.)?

O: Outcome: What will be measured and how will it be measured and with what identified goal (e.g., fewer symptoms, increased satisfaction, reduced mortality, etc.)?

T: Time Frame: How long will the interventions be implemented and data collected for this research?

After the researcher has completed the PICOT question, these additional questions should also be considered to protect patients’ rights and reduce the potential for ethical conflicts:

- Was the study approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB)? The IRB, also known as an independent ethics committee, reviews research studies to protect the rights and welfare of participants.[10] Read more about ethics related to research in the “Ethical Practice” chapter.

- Were the participants protected? Researchers have the responsibility to protect human rights, uphold HIPAA, and respect the personal values of the participants.

- Did the benefits of the intervention outweigh the risk(s)? Researchers have the responsibility to identify if there is a possibility for increased harm to the patients because of the research project.

- Were informed consents obtained? All research participants must provide written informed consent before a study can begin. Researchers must ensure the participants were fully informed of the study, provided risks and benefits, and allowed to exit the study at any time.

- Were vulnerable populations protected? Populations of study that include infants, minorities, children, elderly, socioeconomically disadvantaged, prisoners, etc., are considered vulnerable populations, and researchers must ensure their rights and safety are accounted for.

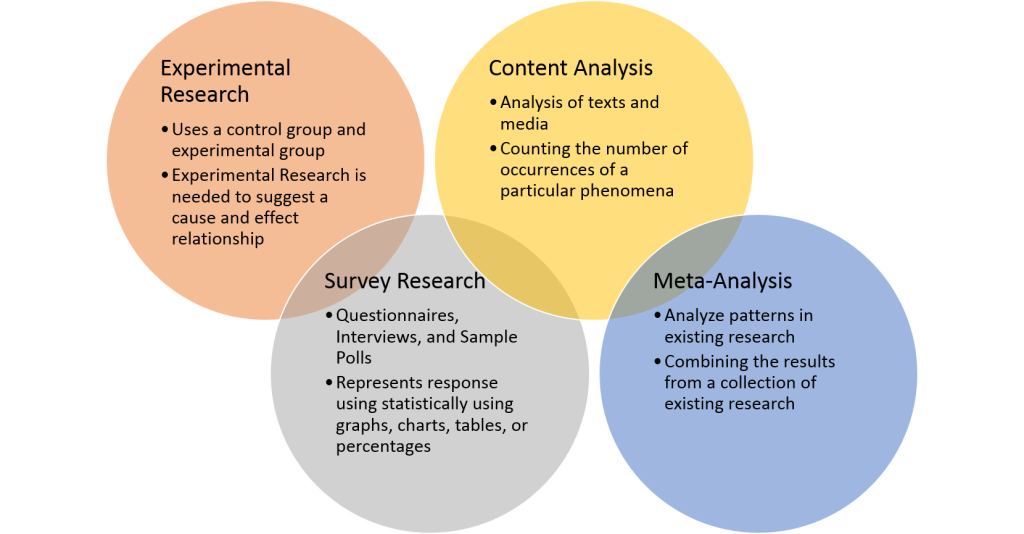

After the nurse researcher confirms participants’ rights are protected and has established a PICOT question, the next step is to design the research study and review existing research. Research designs are categorized by the type of data that is collected and reviewed. See Figure 9.9[11] for an illustration of different types of research. The three basic types of nursing research are quantitative studies, qualitative studies, and meta-analyses.

- Quantitative Studies: These studies provide objective data by using number values to explain outcomes. Researchers can use statistical analysis to determine the strength of the findings, as well as identify correlations.

- View an example of an quantitative research study.

- Qualitative Studies: These studies provide subjective data, often focusing on the perception or experience of the participants. Data is collected through observations and open-ended questions and is often referred to as experimental data. Data is interpreted by recurring themes in participants’ views and observations.

- View an example of a qualitative research study.

- Meta-Analyses: A meta-analysis, also referred to as a “systematic review,” compares the results of independent research studies asking similar research questions. A meta-analysis often collects both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a well-rounded evaluation by providing both objective and subjective outcomes. This research design often requires more time and resources, but it also promotes consistency and reliability through the identification of common themes.

- View an example of a meta-analysis/systematic review.

Nurses must understand the types of research designs to accurately understand and apply the research findings. Additionally, only research from peer-reviewed scholarly journals should be used. Scholarly journals use a process called “peer review” to ensure high quality. An article that is peer reviewed has been reviewed independently by at least two other academic experts in the same field as the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Nurses must also be aware of the difference between primary and secondary sources of scholarly evidence. A primary source is the original study or report of an experiment or clinical problem. The evidence is typically written and published by the individual(s) conducting the research and includes a literature review, description of the research design, statistical analysis of the data, and discussion regarding the implications of the results.

A secondary source is written by an author who gathers existing data provided from research completed by another individual. A secondary source analyzes and reports on findings from other research projects and may interpret findings or draw conclusions. In nursing research secondary sources of evidence are typically published as a systematic review and meta-analysis.

View QUT Library’s Primary vs. secondary sources YouTube video.[12]

By understanding these basic research concepts, nurses can accurately implement current evidence-based practice based on continually evolving nursing research.

Media Attributions

- Flowchart-sm

- PICOT by Kim Ernstmeyer PNG

- Quantitative_methods

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Flowchart-sm.png” by Bates98 is licensed under CC BY_SA 4.0 ↵

- Chien, L. Y. (2019). Evidence-based practice and nursing research. The Journal of Nursing Research: JNR, 27(4), e29. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000346 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2006). Nursing research. https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Position-Statements-White-Papers/Nursing-Research ↵

- Lansing Community College Library. (2021, August 27). Nursing: PICOT. https://libguides.lcc.edu/c.php?g=167860&p=6198388 ↵

- “PICOT.png” by Kim Ernstmeyer for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- U. S. Food & Drug Administration. (2019, April 18). Institutional review boards frequently asked questions: Guidance for institutional review boards and clinical investigators. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/institutional-review-boards-frequently-asked-questions ↵

- “Quantitative_methods.png” by Remydiligent1 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- QUT Library. (2020, November 22). Primary vs. secondary sources [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/FZRxYfWYEBI ↵

Economics and health care reimbursement models impact health care institutional budgets that ultimately impact nurse staffing. A budget is an estimate of revenue and expenses over a specified period of time, usually over a year. There are two basic types of health care budgets that affect nursing: capital and operating budgets. Capital budgets are used to plan investments and upgrades to tangible assets that lose or gain value over time. Capital is something that can be touched, such as buildings or computers. Operating budgets include personnel costs and annual facility operating costs.[1] Typically 40% of the operating budgets of health care agencies are dedicated to nursing staffing. As a result, nursing is often targeted for reduced hours and other cutbacks.[2]

What is the value of a nurse? Nurses are priceless to the clients, families, and communities they serve, but health care organizations are tasked with calculating the cost of delivering safe, high-quality nursing care using affordable staffing models. All members of the health care team must understand the relationship between economics, resources, budgeting, and staffing, and how these issues affect their ability to provide safe, quality care to their patients.

As health care agencies continue to adapt to meet “Pay for Performance” reimbursement models and deliver cost-effective care to an aging population with complex health needs, many nurses are experiencing changes in staffing models.[3] Strategies implemented by agencies to facilitate cost-effective nurse staffing include acuity-based staffing, team nursing, mandatory overtime, floating, on call, and off with benefits. Agencies may also use agency nurses when nurse shortages occur.

Acuity-Based Staffing

Historically, inpatient staffing patterns focused on “nurse-to-patient ratios” where a specific number of patients were assigned to each registered nurse during a shift. Acuity-based staffing is a patient assignment model that takes into account the level of patient care required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. As a result of acuity-based staffing, the number of clients a nurse cares for often varies from shift to shift as the needs of the patients change. Acuity-based staffing promotes efficient use of resources by ensuring nurses have adequate time to care for complex patients.

Read more information about acuity-based staffing in the “Prioritization” chapter.

Team Nursing

Team nursing is a common staffing pattern that uses a combination of Registered Nurses (RNs), Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses (LPN/VNs), and Assistive Personnel (AP) to care for a group of patients. The RN is the leader of a nursing team, making assignments and delegating nursing care to other members of the team with appropriate supervision. Team nursing is an example of allocating human resources wisely to provide quality and cost-effective care. In order for team nursing to be successful, team members must use effective communication and organize their shift as a team.

Read more about team nursing in the “Delegation and Supervision” chapter of this book.

Mandatory Overtime

When client numbers and acuity levels exceed the number of staff scheduled for a shift, nurses may experience mandatory overtime as an agency staffing tool. Mandatory overtime requires a nurse to stay and care for patients beyond their scheduled shift when there is a lack of nursing staff (often referred to as short staffing). The American Nurses Association recognizes mandatory overtime as a dangerous staffing practice because of patient safety concerns related to overtired staff. Depending on state laws, nurses can be held liable for patient abandonment or neglect charges for refusing to stay when mandated. Nurses should be aware of state and organizational policies related to mandatory overtime.[4]

Read more about ANA’s advocacy for adequate nurse staffing.

Floating

Floating is a common agency staffing strategy that asks nurses to temporarily work on a different unit to help cover a short-staffed shift. Floating can reduce personnel costs by reducing overtime payments for staff. It can also reduce nurse burnout occurring from working in an environment without enough personnel.

Nurses must be aware of their rights and responsibilities when asked to float because they are still held accountable for providing safe patient care according to their state's Nurse Practice Act and professional standards of care. Before accepting a floating assignment, nurses should ensure the assignment is aligned with their skill set and they receive orientation to the new environment before caring for patients. If an error occurs and the nurse is held liable, the fact they received a floating assignment does not justify the error. As the ANA states, nurses don’t just have the right to refuse a floating patient assignment; they have the obligation to do so if it is unsafe.[5] The ANA has developed several questions to guide nurses through the decision process of accepting patient assignments. Review these questions in the following box.

ANA’s Suggested Questions When Deciding on Accepting a Patient Assignment[6]

- What is the assignment? Clarify what is expected; do not assume. Be certain about the details.

- What are the characteristics of the patients being assigned? Don’t just respond to the number of patients assigned. Make a critical assessment of the needs of each client and their complexity and stability. Be aware of the resources available to meet those needs.

- Do you have the expertise to care for the patients? Always ask yourself if you are familiar with caring for the types of patients assigned? If this is a “float assignment,” are you cross-trained to care for these patients? Is there a “buddy system” in place with staff who are familiar with the unit? If there is no cross-training or “buddy system,” has the patient load been modified accordingly?

- Do you have the experience and knowledge to manage the patients for whom you are being assigned care? If the answer to the question is “No,” you have an obligation to articulate your limitations. Limitations in experience and knowledge may not require refusal of the assignment, but rather an agreement regarding supervision or a modification of the assignment to ensure patient safety. If no accommodation for limitations is considered, the nurse has an obligation to refuse an assignment for which they lack education or experience.

- What is the geography of the assignment? Are you being asked to care for patients who are in close proximity for efficient management, or are the patients at opposite ends of the hall or in different units? If there are geographic difficulties, what resources are available to manage the situation? If the patients are in more than one unit and you must go to another unit to provide care, who will monitor patients out of your immediate attention?

- Is this a temporary assignment? When other staff are located for assistance, will you be relieved? If the assignment is temporary, it may be possible to accept a difficult assignment knowing that there will soon be reinforcements. Is there a pattern of short staffing at this agency, or is this truly an emergency?

- Is this a crisis or an ongoing staffing pattern? If the assignment is being made because of an immediate need or crisis in the unit, the decision to accept the assignment may be based on that immediate need. However, if the staffing pattern is an ongoing problem, you have the obligation to identify unmet standards of care that are occurring as a result of ongoing staffing inadequacies. This may result in a formal request for peer review using the appropriate channels.

- Can you take the assignment in good faith? If not, you will need to have the assignment modified or refuse the assignment. Consult your state’s Nurse Practice Act regarding clarification of accepting an assignment in good faith.

On Call and Off With Benefits

When staffing projected for a shift exceeds the number of clients admitted and their acuity, agencies often decrease staffing due to operating budget limitations. Two common approaches that agencies use to reduce staffing on a shift-to-shift basis are placing nurses “on call” or “off with benefits.”

On Call

On call is an agency staffing strategy when a nurse is not immediately needed for their scheduled shift. The nurse may have the options to report to work and do work-related education or stay home. When a nurse is on call, they typically receive a reduced hourly wage and have a required response time. A required response time means if a nurse who is on call is needed later in the shift, they need to be able to report and assume patient care in a designated amount of time.

Off With Benefits

A nurse may be placed “off with benefits” when not needed for their scheduled shift. When a nurse is placed off with benefits, they typically do not receive an hourly wage and are not expected to report to work or be on call, but still accrue benefits such as insurance and paid time off.

Agency Nursing

Agency nursing is an industry in health care that provides nurses to hospitals and health care facilities in need of staff. Nurse agencies employ nurses to work on an as-needed basis and place them in facilities that have staffing shortages.

Advocacy by the ANA for Appropriate Nurse Staffing

According to the ANA, there is significant evidence showing appropriate nurse staffing contributes to improved client outcomes and greater satisfaction for both clients and staff. Appropriate staffing levels have multiple client benefits, including the following[7]:

- Reduced mortality rates

- Reduced length of client stays

- Reduced number of preventable events, such as falls and infections

Nurses also benefit from appropriate staffing. Appropriate workload allows nurses to utilize their full expertise, without the pressure of fatigue. A recent report suggested that staff levels should depend on the following factors[8]:

- Patient complexity, acuity, or stability

- Number of admissions, discharges, and transfers

- Professional nurses’ and other staff members’ skill level and expertise

- Physical space and layout of the nursing unit

- Availability of technical support and other resources

Visit ANA's interactive Principles of Nurse Staffing infographic.

Read more information about patient acuity tools in the "Prioritization" chapter.

Cost-Effective Nursing Care

One of ANA's Standards of Professional Performance is Resource Stewardship. The Resource Stewardship standard states, “The registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan, provide, and sustain evidence-based nursing services that are safe, effective, financially responsible, and used judiciously.”[9] Nurses have a fiscal responsibility to demonstrate resource stewardship to the employing organization and payer of care. This responsibility extends beyond direct patient care and encompasses a broader role in health care sustainability. By effectively managing resources, nurses help reduce unnecessary expenditures and ensure that funds are allocated where they are most needed. This can include everything from minimizing waste in the use of medical supplies to optimizing staffing levels to avoid both overworking and underutilizing nursing staff.

Nurses can help contain health care costs by advocating for patients and ensuring their care is received on time, the plan of care is appropriate and individualized to them, and clear documentation has been completed. These steps reduce waste, avoid repeated tests, and ensure timely treatments that promote positive patient outcomes and reduce unnecessary spending. Nurses routinely incorporate these practices to provide cost-effective nursing care in their daily practice:

- Keeping supplies near the client's room

- Preventing waste by only bringing needed supplies into a client’s room

- Avoiding prepackaged kits with unnecessary supplies

- Avoiding “Admission Bags” with unnecessary supplies

- Using financially-sound thinking

- Understanding health care costs and reimbursement models

- Charging out supplies and equipment according to agency policy

- Being Productive

- Organizing and prioritizing

- Using effective time management

- Grouping tasks when entering client rooms (i.e., clustering cares)

- Assigning and delegating nursing care to the nursing team according to the state Nurse Practice Act and agency policy

- Using effective team communication to avoid duplication of tasks and request assistance when needed

- Updating and individualizing clients’ nursing care plans according to their current needs

- Documenting for continuity of client care that avoids duplication and focuses on effective interventions based on identified outcomes and goals

Health care costs impact both macroeconomics (affecting the entire country and society as a whole) and microeconomics (affecting the financial decisions of businesses and individuals). Health care services are funded by several payment models, including federal government programs (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid), private health insurance (typically provided by employers), and self-pay. Payment models also impact services provided by health care agencies, as well as the services and medications available to consumers. Nurses must be aware of these payment models because of the impact on the allocation of resources they need to provide patient care.

Government Funding

Medicare and Medicaid were signed into law in 1965. These programs provide eligible Americans support for their health care needs with taxpayer funding.

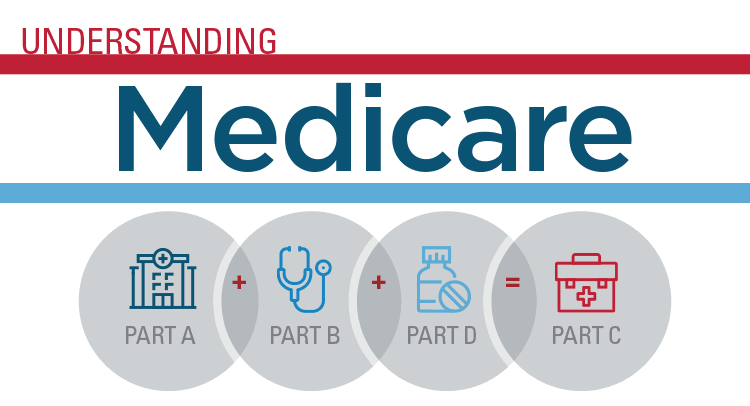

Medicare

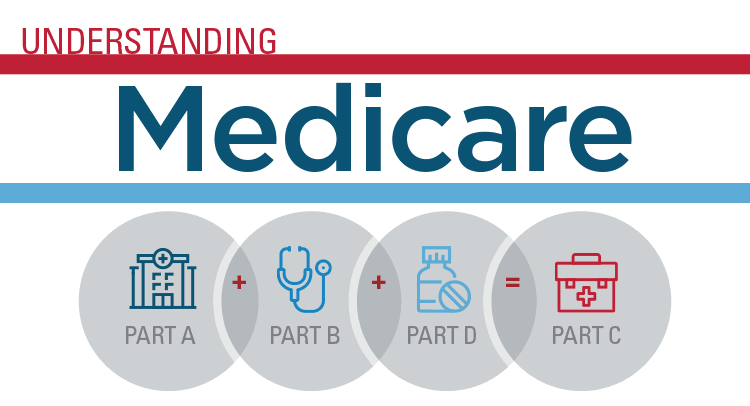

Medicare is a federal health insurance program used by people aged 65 and older, younger individuals with permanent disabilities, and people with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. Medicare coverage has four possible components: Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D.[10] See Figure 8.5[11] for an infographic illustrating Medicare Parts A, B, C, and D.

- Part A (Hospital Insurance): Part A covers patients’ hospital stays, skilled nursing facility care, hospice care, and some home health care. Part A is free for clients if they or their spouse paid Medicare taxes for a specific amount of time while working. If clients are not eligible for free coverage, they can buy it with premiums based on the number of months they paid Medicare taxes.

- Part B (Medical Insurance): Part B covers doctors’ services, outpatient care, medical supplies, and preventative care services. Most people pay a standard premium for Part B.

- Part C (Medicare Advantage Plan): A Medicare Advantage Plan is a health plan choice offered by private companies approved by Medicare, also referred to as "Part C." These plans provide Part A and Part B coverage, and most also include Part D coverage. Medicare Advantage Plans may offer extra coverage, such as vision, hearing, dental, and/or health and wellness programs.

- Part D (Prescription Drug Coverage): Part D helps cover the cost of prescription drugs and vaccinations. To get Medicare drug coverage, clients must enroll in a Medicare-approved plan that offers drug coverage. Different plans vary in cost and what prescription medications they cover, also referred to as a formulary.

Read more about Medicare at medicare.gov.

Medicaid

Medicaid is the largest source of health coverage in the United States. It is a joint federal and state program covering eligible individuals with taxpayer funding. To participate in Medicaid, federal law requires states to cover certain groups of individuals, such as low-income families, qualified pregnant women and children, and individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI). States may choose to cover additional groups, such as individuals receiving home and community-based services and children in foster care who are not otherwise eligible.[12]

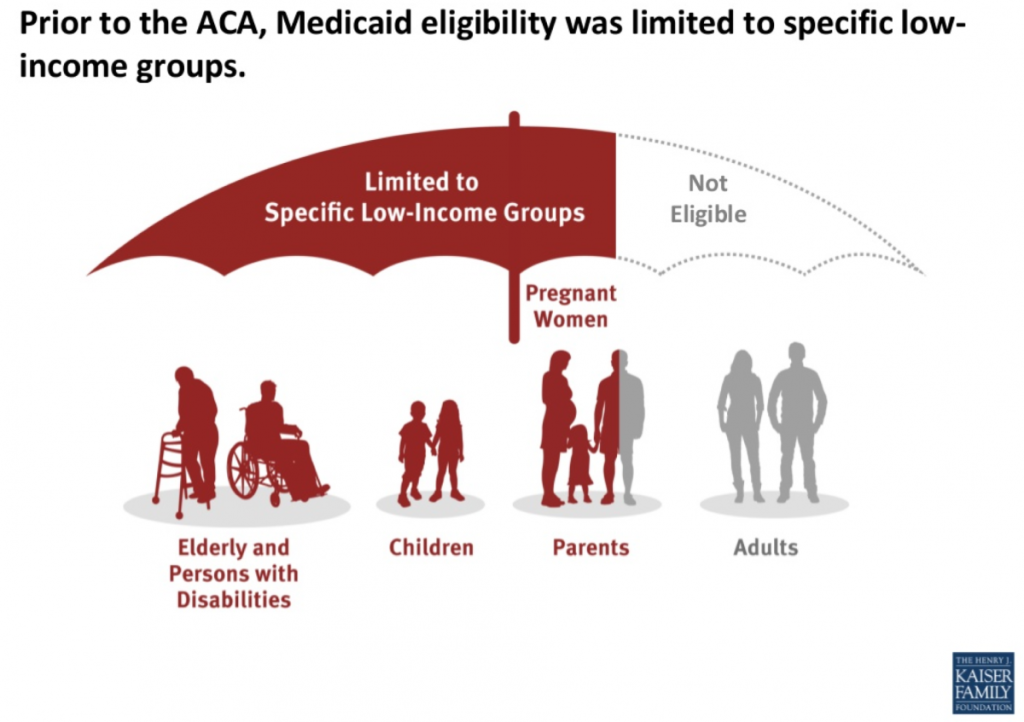

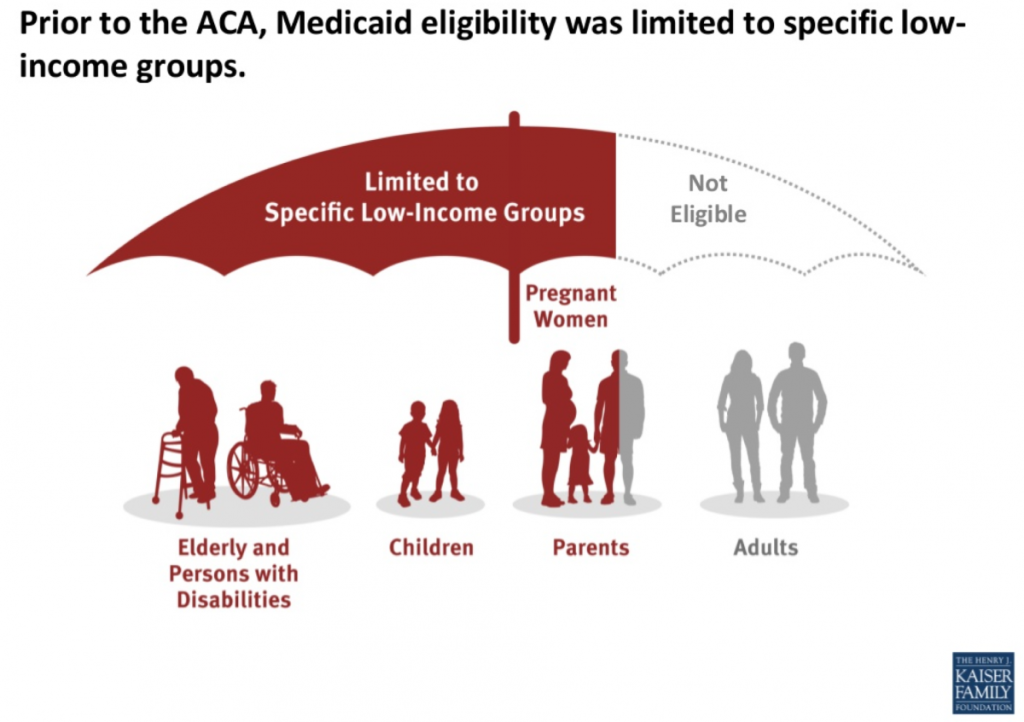

In 2014 the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid to cover all low-income Americans under the age of 65 years and also expanded coverage for children. Due to the individual states’ involvement in Medicaid, coverage of services varies from state to state.[13] See Figure 8.6[14] for an illustration of Medicaid-eligible populations.

Individuals with Medicaid plans have support in paying for a variety of health services, including hospital care, laboratory and diagnostic testing, skilled nursing care, home health services, preventative care, and regular outpatient provider visits.

Other Government Health Funding

There are several other types of health coverage provided by federal and state programs. Read more about these programs in the following box.

Other Federal and State Health Care Funding Programs[15]

- State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): A program designed to help provide coverage for uninsured children whose family income is below average but too high to qualify for Medicaid. The federal government provides matching funds to states for health insurance for these families.

Read more details at InsuredKidsNow.gov.

- Children and Youth With Special Health Care Needs: This program coordinates funding and resources to provide care to people with special health needs.

Read more details at Children With Special Health Care Needs.

- Tricare: This program covers about 9 million active duty and retired military personnel and their families.

Read more details at TRICARE.

- Veterans Health Administration (VHA): This government-operated health care system provides comprehensive health services to eligible military veterans. About 9 million veterans are enrolled.

Read more details at Veterans Health Administration.

- Indian Health Service: This system of government hospitals and clinics provides health services to about 2 million Native Americans living on or near a reservation.

Read more details at Indian Health Service.

- Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) Program: This program allows private insurers to offer insurance plans within guidelines set by the government for the benefit of active and retired federal employees and their survivors.

Read more details at The Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program.

- Refugee Health Promotion Program: This program provides short-term health insurance to newly arrived refugees.

Read more details at Refugee Health Promotion Program (RHP).

Private Insurance

Individuals who are not eligible for government-funded health programs like Medicare or Medicaid can purchase private health insurance. Many individuals with private insurance obtain coverage through their employers’ benefit packages, where the costs for coverage are shared between the employer and the employee. If an individual does not receive health insurance through their employer, they may purchase it from the Marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act.

Read more about obtaining health insurance through the ACA Marketplace at healthcare.gov.

Self-Pay

Some individuals do not have health care coverage provided by their employer, do not qualify for Medicare or Medicaid, and do not elect to purchase health insurance coverage. Instead, these individuals go without coverage and pay health care costs as they arise. See Figure 8.7[16] for a graph illustrating the decreasing numbers of uninsured consumers in the United States over the past several decades. Unfortunately, due to the skyrocketing cost of health care services, significant bills can accrue from a single serious illness or traumatic injury that can put consumers without health care coverage in jeopardy of bankruptcy. Nurses can assist uninsured individuals to better understand coverage options by referring them to a case manager or social worker.

Types of Insurance Coverage

Health insurance plans have different types of coverage. Common types of health insurance plans are HMO, PPO, POS, HDHP, or HSA.

- Health Maintenance Organization (HMO): HMO plans usually have the lowest monthly cost for coverage (i.e., premium) but also have a smaller network of providers and hospitals where the consumer may receive insured care. This means the consumer is restricted to receive care only from specific providers and health facilities. Many HMOs also require the consumer to see their primary care provider to request a referral to see a specialist, which may or may not be approved by the HMO. Additionally, many tests, procedures, surgeries, and medications require “preauthorization” by the HMO, which may or may not be approved. Due to these restrictions, consumers may find they sacrifice flexibility and choice for lower cost of coverage.[17]

- Preferred Provider Organization (PPO): PPO plans are typically less restrictive than HMOs. PPOs typically include “in-network” providers and hospitals where costs are lower if care is received in-network, but consumers also have a choice to receive “out-of-network” care at a higher cost. Referrals from a primary care provider are not generally required in a PPO. The monthly premium for a PPO plan is typically higher than an HMO plan, but PPOs allow more consumer flexibility in choosing their health care providers.[18]

- Point of Service (POS): POS plans are a combination of HMO and PPO plans, where the insured consumer has a preferred provider network to receive health care services at a lower cost, but also has the flexibility to receive care outside of their network. When consumers venture outside of the network, they often have to pay a significant share of the cost.[19]

- High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP): HDHP plans are often popular for younger individuals without chronic health care needs who spend little on health care but require coverage in the event a high-cost injury or illness occurs. HDHPs typically have lower monthly premiums but require the individual to pay more upfront for health care services before the coverage kicks in (referred to as a “deductible”). Individuals with an HDHP often have an associated Health Savings Account (HSA). HDHPs have grown in popularity as more employers offer these plans in an attempt to contain health care costs by shifting more cost-sharing to the consumer.

- Health Savings Account (HSA): An HSA is a special account reserved for eligible medical expenses with strict usage rules. Money placed in an HSA can often be deducted from a consumer’s pretaxed pay, resulting in tax savings. In addition to purchasing items like glasses, contacts, and over-the-counter medications, HSAs can often be used to pay for deductibles. Some employers deposit a specified amount of money into an employee’s HSA every year to help reimburse high deductibles.

Deductible and Copays

Costs paid by an insured individual are commonly referred to as “out-of-pocket expenses.” Out-of-pocket expenses include deductibles and co-pays. A deductible is the amount of money a consumer pays before the health care plan pays anything. Deductibles generally apply per person per calendar year. Typically, a PPO has higher premiums but lower deductibles than a HDHP.

A co-pay is a flat fee the consumer pays at the time of the health care service. For example, when visiting a primary provider, the consumer may pay $20 to the provider at each visit as a co-pay. Some health care plans require co-pays in addition to deductibles.

Nursing Considerations

Understanding a client’s health insurance coverage is important because it may impact their choice of health services and their ability to purchase medications and other supplies. Additionally, if a client is self-pay, it is helpful to refer them to resources such as case managers, social workers, or the financial department of the agency. These resources can assist them in obtaining affordable health care coverage through the ACA Marketplace or other government programs.

Health care costs impact both macroeconomics (affecting the entire country and society as a whole) and microeconomics (affecting the financial decisions of businesses and individuals). Health care services are funded by several payment models, including federal government programs (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid), private health insurance (typically provided by employers), and self-pay. Payment models also impact services provided by health care agencies, as well as the services and medications available to consumers. Nurses must be aware of these payment models because of the impact on the allocation of resources they need to provide patient care.

Government Funding

Medicare and Medicaid were signed into law in 1965. These programs provide eligible Americans support for their health care needs with taxpayer funding.

Medicare

Medicare is a federal health insurance program used by people aged 65 and older, younger individuals with permanent disabilities, and people with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. Medicare coverage has four possible components: Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D.[20] See Figure 8.5[21] for an infographic illustrating Medicare Parts A, B, C, and D.

- Part A (Hospital Insurance): Part A covers patients’ hospital stays, skilled nursing facility care, hospice care, and some home health care. Part A is free for clients if they or their spouse paid Medicare taxes for a specific amount of time while working. If clients are not eligible for free coverage, they can buy it with premiums based on the number of months they paid Medicare taxes.

- Part B (Medical Insurance): Part B covers doctors’ services, outpatient care, medical supplies, and preventative care services. Most people pay a standard premium for Part B.

- Part C (Medicare Advantage Plan): A Medicare Advantage Plan is a health plan choice offered by private companies approved by Medicare, also referred to as "Part C." These plans provide Part A and Part B coverage, and most also include Part D coverage. Medicare Advantage Plans may offer extra coverage, such as vision, hearing, dental, and/or health and wellness programs.

- Part D (Prescription Drug Coverage): Part D helps cover the cost of prescription drugs and vaccinations. To get Medicare drug coverage, clients must enroll in a Medicare-approved plan that offers drug coverage. Different plans vary in cost and what prescription medications they cover, also referred to as a formulary.

Read more about Medicare at medicare.gov.

Medicaid

Medicaid is the largest source of health coverage in the United States. It is a joint federal and state program covering eligible individuals with taxpayer funding. To participate in Medicaid, federal law requires states to cover certain groups of individuals, such as low-income families, qualified pregnant women and children, and individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI). States may choose to cover additional groups, such as individuals receiving home and community-based services and children in foster care who are not otherwise eligible.[22]

In 2014 the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid to cover all low-income Americans under the age of 65 years and also expanded coverage for children. Due to the individual states’ involvement in Medicaid, coverage of services varies from state to state.[23] See Figure 8.6[24] for an illustration of Medicaid-eligible populations.

Individuals with Medicaid plans have support in paying for a variety of health services, including hospital care, laboratory and diagnostic testing, skilled nursing care, home health services, preventative care, and regular outpatient provider visits.

Other Government Health Funding

There are several other types of health coverage provided by federal and state programs. Read more about these programs in the following box.

Other Federal and State Health Care Funding Programs[25]

- State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): A program designed to help provide coverage for uninsured children whose family income is below average but too high to qualify for Medicaid. The federal government provides matching funds to states for health insurance for these families.

Read more details at InsuredKidsNow.gov.

- Children and Youth With Special Health Care Needs: This program coordinates funding and resources to provide care to people with special health needs.

Read more details at Children With Special Health Care Needs.

- Tricare: This program covers about 9 million active duty and retired military personnel and their families.

Read more details at TRICARE.

- Veterans Health Administration (VHA): This government-operated health care system provides comprehensive health services to eligible military veterans. About 9 million veterans are enrolled.

Read more details at Veterans Health Administration.

- Indian Health Service: This system of government hospitals and clinics provides health services to about 2 million Native Americans living on or near a reservation.

Read more details at Indian Health Service.

- Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) Program: This program allows private insurers to offer insurance plans within guidelines set by the government for the benefit of active and retired federal employees and their survivors.

Read more details at The Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Program.

- Refugee Health Promotion Program: This program provides short-term health insurance to newly arrived refugees.

Read more details at Refugee Health Promotion Program (RHP).

Private Insurance

Individuals who are not eligible for government-funded health programs like Medicare or Medicaid can purchase private health insurance. Many individuals with private insurance obtain coverage through their employers’ benefit packages, where the costs for coverage are shared between the employer and the employee. If an individual does not receive health insurance through their employer, they may purchase it from the Marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act.

Read more about obtaining health insurance through the ACA Marketplace at healthcare.gov.

Self-Pay

Some individuals do not have health care coverage provided by their employer, do not qualify for Medicare or Medicaid, and do not elect to purchase health insurance coverage. Instead, these individuals go without coverage and pay health care costs as they arise. See Figure 8.7[26] for a graph illustrating the decreasing numbers of uninsured consumers in the United States over the past several decades. Unfortunately, due to the skyrocketing cost of health care services, significant bills can accrue from a single serious illness or traumatic injury that can put consumers without health care coverage in jeopardy of bankruptcy. Nurses can assist uninsured individuals to better understand coverage options by referring them to a case manager or social worker.

Types of Insurance Coverage

Health insurance plans have different types of coverage. Common types of health insurance plans are HMO, PPO, POS, HDHP, or HSA.

- Health Maintenance Organization (HMO): HMO plans usually have the lowest monthly cost for coverage (i.e., premium) but also have a smaller network of providers and hospitals where the consumer may receive insured care. This means the consumer is restricted to receive care only from specific providers and health facilities. Many HMOs also require the consumer to see their primary care provider to request a referral to see a specialist, which may or may not be approved by the HMO. Additionally, many tests, procedures, surgeries, and medications require “preauthorization” by the HMO, which may or may not be approved. Due to these restrictions, consumers may find they sacrifice flexibility and choice for lower cost of coverage.[27]

- Preferred Provider Organization (PPO): PPO plans are typically less restrictive than HMOs. PPOs typically include “in-network” providers and hospitals where costs are lower if care is received in-network, but consumers also have a choice to receive “out-of-network” care at a higher cost. Referrals from a primary care provider are not generally required in a PPO. The monthly premium for a PPO plan is typically higher than an HMO plan, but PPOs allow more consumer flexibility in choosing their health care providers.[28]

- Point of Service (POS): POS plans are a combination of HMO and PPO plans, where the insured consumer has a preferred provider network to receive health care services at a lower cost, but also has the flexibility to receive care outside of their network. When consumers venture outside of the network, they often have to pay a significant share of the cost.[29]

- High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP): HDHP plans are often popular for younger individuals without chronic health care needs who spend little on health care but require coverage in the event a high-cost injury or illness occurs. HDHPs typically have lower monthly premiums but require the individual to pay more upfront for health care services before the coverage kicks in (referred to as a “deductible”). Individuals with an HDHP often have an associated Health Savings Account (HSA). HDHPs have grown in popularity as more employers offer these plans in an attempt to contain health care costs by shifting more cost-sharing to the consumer.

- Health Savings Account (HSA): An HSA is a special account reserved for eligible medical expenses with strict usage rules. Money placed in an HSA can often be deducted from a consumer’s pretaxed pay, resulting in tax savings. In addition to purchasing items like glasses, contacts, and over-the-counter medications, HSAs can often be used to pay for deductibles. Some employers deposit a specified amount of money into an employee’s HSA every year to help reimburse high deductibles.

Deductible and Copays

Costs paid by an insured individual are commonly referred to as “out-of-pocket expenses.” Out-of-pocket expenses include deductibles and co-pays. A deductible is the amount of money a consumer pays before the health care plan pays anything. Deductibles generally apply per person per calendar year. Typically, a PPO has higher premiums but lower deductibles than a HDHP.

A co-pay is a flat fee the consumer pays at the time of the health care service. For example, when visiting a primary provider, the consumer may pay $20 to the provider at each visit as a co-pay. Some health care plans require co-pays in addition to deductibles.

Nursing Considerations

Understanding a client’s health insurance coverage is important because it may impact their choice of health services and their ability to purchase medications and other supplies. Additionally, if a client is self-pay, it is helpful to refer them to resources such as case managers, social workers, or the financial department of the agency. These resources can assist them in obtaining affordable health care coverage through the ACA Marketplace or other government programs.

Economics and health care reimbursement models impact health care institutional budgets that ultimately impact nurse staffing. A budget is an estimate of revenue and expenses over a specified period of time, usually over a year. There are two basic types of health care budgets that affect nursing: capital and operating budgets. Capital budgets are used to plan investments and upgrades to tangible assets that lose or gain value over time. Capital is something that can be touched, such as buildings or computers. Operating budgets include personnel costs and annual facility operating costs.[30] Typically 40% of the operating budgets of health care agencies are dedicated to nursing staffing. As a result, nursing is often targeted for reduced hours and other cutbacks.[31]

What is the value of a nurse? Nurses are priceless to the clients, families, and communities they serve, but health care organizations are tasked with calculating the cost of delivering safe, high-quality nursing care using affordable staffing models. All members of the health care team must understand the relationship between economics, resources, budgeting, and staffing, and how these issues affect their ability to provide safe, quality care to their patients.

As health care agencies continue to adapt to meet “Pay for Performance” reimbursement models and deliver cost-effective care to an aging population with complex health needs, many nurses are experiencing changes in staffing models.[32] Strategies implemented by agencies to facilitate cost-effective nurse staffing include acuity-based staffing, team nursing, mandatory overtime, floating, on call, and off with benefits. Agencies may also use agency nurses when nurse shortages occur.

Acuity-Based Staffing

Historically, inpatient staffing patterns focused on “nurse-to-patient ratios” where a specific number of patients were assigned to each registered nurse during a shift. Acuity-based staffing is a patient assignment model that takes into account the level of patient care required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. As a result of acuity-based staffing, the number of clients a nurse cares for often varies from shift to shift as the needs of the patients change. Acuity-based staffing promotes efficient use of resources by ensuring nurses have adequate time to care for complex patients.

Read more information about acuity-based staffing in the “Prioritization” chapter.

Team Nursing

Team nursing is a common staffing pattern that uses a combination of Registered Nurses (RNs), Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses (LPN/VNs), and Assistive Personnel (AP) to care for a group of patients. The RN is the leader of a nursing team, making assignments and delegating nursing care to other members of the team with appropriate supervision. Team nursing is an example of allocating human resources wisely to provide quality and cost-effective care. In order for team nursing to be successful, team members must use effective communication and organize their shift as a team.

Read more about team nursing in the “Delegation and Supervision” chapter of this book.

Mandatory Overtime

When client numbers and acuity levels exceed the number of staff scheduled for a shift, nurses may experience mandatory overtime as an agency staffing tool. Mandatory overtime requires a nurse to stay and care for patients beyond their scheduled shift when there is a lack of nursing staff (often referred to as short staffing). The American Nurses Association recognizes mandatory overtime as a dangerous staffing practice because of patient safety concerns related to overtired staff. Depending on state laws, nurses can be held liable for patient abandonment or neglect charges for refusing to stay when mandated. Nurses should be aware of state and organizational policies related to mandatory overtime.[33]

Read more about ANA’s advocacy for adequate nurse staffing.

Floating

Floating is a common agency staffing strategy that asks nurses to temporarily work on a different unit to help cover a short-staffed shift. Floating can reduce personnel costs by reducing overtime payments for staff. It can also reduce nurse burnout occurring from working in an environment without enough personnel.

Nurses must be aware of their rights and responsibilities when asked to float because they are still held accountable for providing safe patient care according to their state's Nurse Practice Act and professional standards of care. Before accepting a floating assignment, nurses should ensure the assignment is aligned with their skill set and they receive orientation to the new environment before caring for patients. If an error occurs and the nurse is held liable, the fact they received a floating assignment does not justify the error. As the ANA states, nurses don’t just have the right to refuse a floating patient assignment; they have the obligation to do so if it is unsafe.[34] The ANA has developed several questions to guide nurses through the decision process of accepting patient assignments. Review these questions in the following box.

ANA’s Suggested Questions When Deciding on Accepting a Patient Assignment[35]

- What is the assignment? Clarify what is expected; do not assume. Be certain about the details.

- What are the characteristics of the patients being assigned? Don’t just respond to the number of patients assigned. Make a critical assessment of the needs of each client and their complexity and stability. Be aware of the resources available to meet those needs.

- Do you have the expertise to care for the patients? Always ask yourself if you are familiar with caring for the types of patients assigned? If this is a “float assignment,” are you cross-trained to care for these patients? Is there a “buddy system” in place with staff who are familiar with the unit? If there is no cross-training or “buddy system,” has the patient load been modified accordingly?

- Do you have the experience and knowledge to manage the patients for whom you are being assigned care? If the answer to the question is “No,” you have an obligation to articulate your limitations. Limitations in experience and knowledge may not require refusal of the assignment, but rather an agreement regarding supervision or a modification of the assignment to ensure patient safety. If no accommodation for limitations is considered, the nurse has an obligation to refuse an assignment for which they lack education or experience.

- What is the geography of the assignment? Are you being asked to care for patients who are in close proximity for efficient management, or are the patients at opposite ends of the hall or in different units? If there are geographic difficulties, what resources are available to manage the situation? If the patients are in more than one unit and you must go to another unit to provide care, who will monitor patients out of your immediate attention?

- Is this a temporary assignment? When other staff are located for assistance, will you be relieved? If the assignment is temporary, it may be possible to accept a difficult assignment knowing that there will soon be reinforcements. Is there a pattern of short staffing at this agency, or is this truly an emergency?

- Is this a crisis or an ongoing staffing pattern? If the assignment is being made because of an immediate need or crisis in the unit, the decision to accept the assignment may be based on that immediate need. However, if the staffing pattern is an ongoing problem, you have the obligation to identify unmet standards of care that are occurring as a result of ongoing staffing inadequacies. This may result in a formal request for peer review using the appropriate channels.

- Can you take the assignment in good faith? If not, you will need to have the assignment modified or refuse the assignment. Consult your state’s Nurse Practice Act regarding clarification of accepting an assignment in good faith.

On Call and Off With Benefits

When staffing projected for a shift exceeds the number of clients admitted and their acuity, agencies often decrease staffing due to operating budget limitations. Two common approaches that agencies use to reduce staffing on a shift-to-shift basis are placing nurses “on call” or “off with benefits.”

On Call

On call is an agency staffing strategy when a nurse is not immediately needed for their scheduled shift. The nurse may have the options to report to work and do work-related education or stay home. When a nurse is on call, they typically receive a reduced hourly wage and have a required response time. A required response time means if a nurse who is on call is needed later in the shift, they need to be able to report and assume patient care in a designated amount of time.

Off With Benefits

A nurse may be placed “off with benefits” when not needed for their scheduled shift. When a nurse is placed off with benefits, they typically do not receive an hourly wage and are not expected to report to work or be on call, but still accrue benefits such as insurance and paid time off.

Agency Nursing

Agency nursing is an industry in health care that provides nurses to hospitals and health care facilities in need of staff. Nurse agencies employ nurses to work on an as-needed basis and place them in facilities that have staffing shortages.

Advocacy by the ANA for Appropriate Nurse Staffing

According to the ANA, there is significant evidence showing appropriate nurse staffing contributes to improved client outcomes and greater satisfaction for both clients and staff. Appropriate staffing levels have multiple client benefits, including the following[36]:

- Reduced mortality rates

- Reduced length of client stays

- Reduced number of preventable events, such as falls and infections

Nurses also benefit from appropriate staffing. Appropriate workload allows nurses to utilize their full expertise, without the pressure of fatigue. A recent report suggested that staff levels should depend on the following factors[37]:

- Patient complexity, acuity, or stability

- Number of admissions, discharges, and transfers

- Professional nurses’ and other staff members’ skill level and expertise

- Physical space and layout of the nursing unit

- Availability of technical support and other resources

Visit ANA's interactive Principles of Nurse Staffing infographic.

Read more information about patient acuity tools in the "Prioritization" chapter.

Cost-Effective Nursing Care

One of ANA's Standards of Professional Performance is Resource Stewardship. The Resource Stewardship standard states, “The registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan, provide, and sustain evidence-based nursing services that are safe, effective, financially responsible, and used judiciously.”[38] Nurses have a fiscal responsibility to demonstrate resource stewardship to the employing organization and payer of care. This responsibility extends beyond direct patient care and encompasses a broader role in health care sustainability. By effectively managing resources, nurses help reduce unnecessary expenditures and ensure that funds are allocated where they are most needed. This can include everything from minimizing waste in the use of medical supplies to optimizing staffing levels to avoid both overworking and underutilizing nursing staff.

Nurses can help contain health care costs by advocating for patients and ensuring their care is received on time, the plan of care is appropriate and individualized to them, and clear documentation has been completed. These steps reduce waste, avoid repeated tests, and ensure timely treatments that promote positive patient outcomes and reduce unnecessary spending. Nurses routinely incorporate these practices to provide cost-effective nursing care in their daily practice:

- Keeping supplies near the client's room

- Preventing waste by only bringing needed supplies into a client’s room

- Avoiding prepackaged kits with unnecessary supplies

- Avoiding “Admission Bags” with unnecessary supplies

- Using financially-sound thinking

- Understanding health care costs and reimbursement models

- Charging out supplies and equipment according to agency policy

- Being Productive

- Organizing and prioritizing

- Using effective time management

- Grouping tasks when entering client rooms (i.e., clustering cares)

- Assigning and delegating nursing care to the nursing team according to the state Nurse Practice Act and agency policy

- Using effective team communication to avoid duplication of tasks and request assistance when needed

- Updating and individualizing clients’ nursing care plans according to their current needs

- Documenting for continuity of client care that avoids duplication and focuses on effective interventions based on identified outcomes and goals

As discussed in the previous section, hospitals and health care providers are paid for services provided to individuals by government insurance programs (such as Medicare and Medicaid), private insurance companies, or people using their out-of-pocket funds. Traditionally, health care institutions were paid based on a “fee-for-service” model. For example, if a patient was admitted to a hospital with pneumonia, the hospital billed that individual's insurance program for the cost of care.

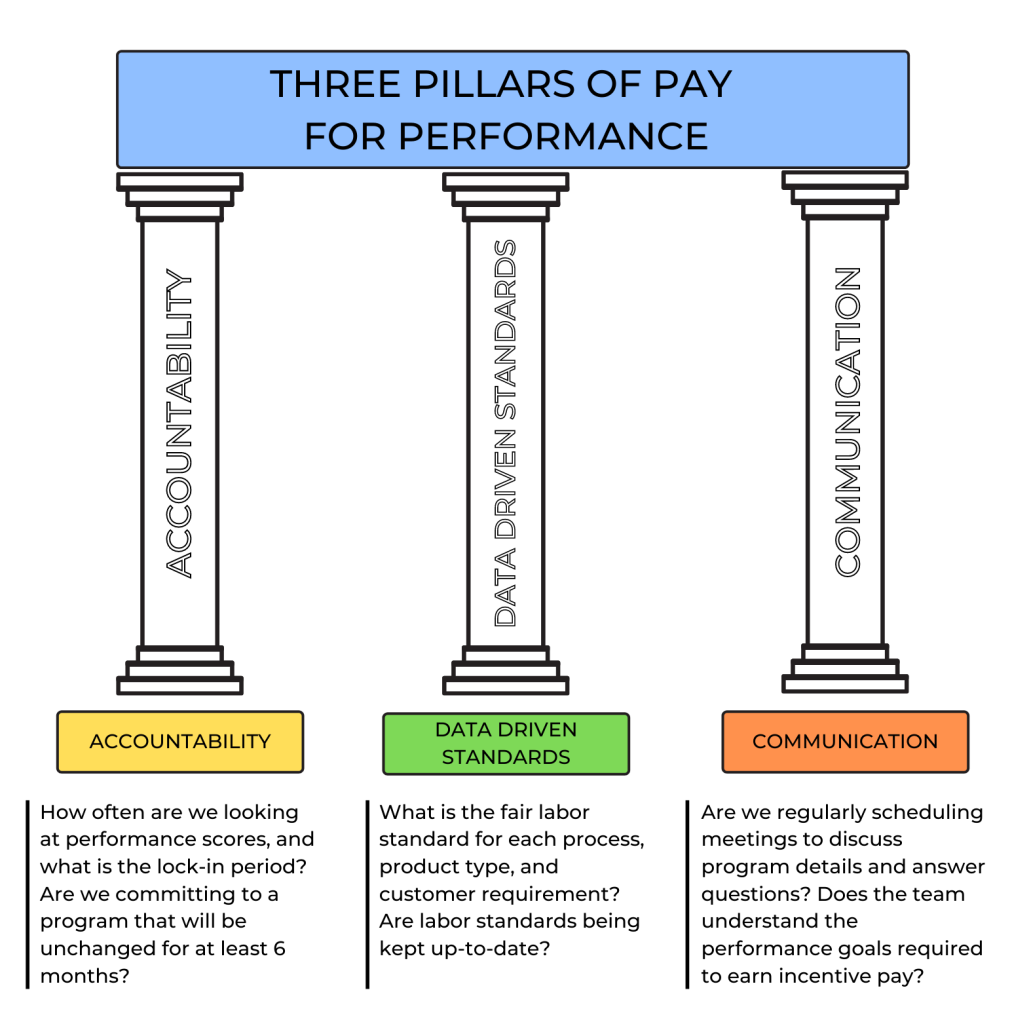

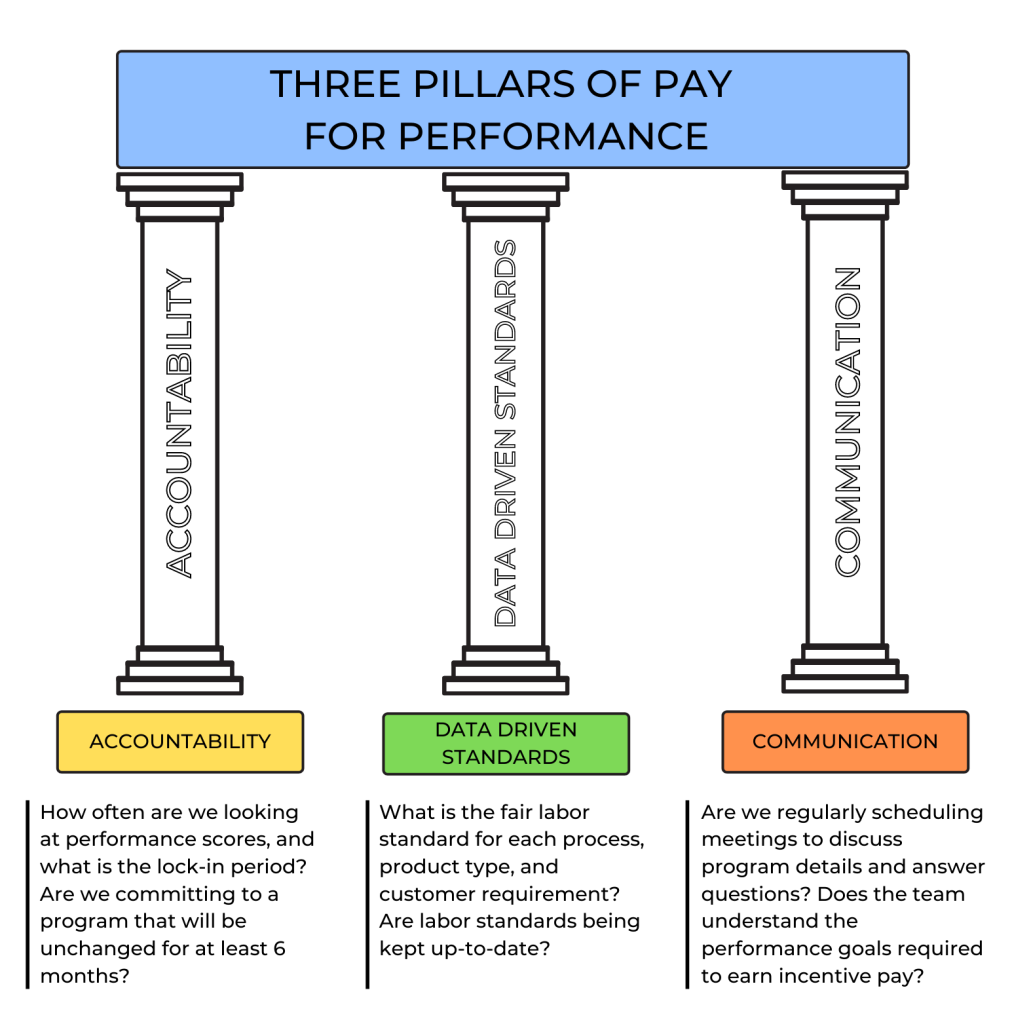

However, as part of a recent national strategy to reduce health care costs, insurance providers have transitioned to "Pay for Performance" reimbursement models that are based on overall agency performance and patient outcomes.

Pay for Performance

Pay for Performance, also known as value-based payment, refers to reimbursement models that attach financial incentives to the performance of health care agencies and providers. Pay for Performance models tie higher reimbursement payments to positive patient outcomes, best practices, and patient satisfaction, thus aligning payment with value and quality.[39] Nurses support higher reimbursement levels to their employers based on their documentation related to nursing care plans and achievement of expected patient outcomes.

There are two Pay for Performance models. The first model rewards hospitals and providers with higher reimbursement payments based on how well they perform on process, quality, and efficiency measures. The second model penalizes hospitals and providers for subpar performance by reducing reimbursement amounts.[40] For example, Medicare no longer reimburses hospitals to treat patients who acquire certain preventable conditions during their hospital stay, such as pressure injuries or urinary tract infections associated with use of catheters.[41]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), spurred by the Affordable Care Act, has led the way in value-based payment with a variety of payment models. CMS is the largest health care funder in the United States with almost 40% of overall health care spending for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS developed three Pay for Performance models that impact hospitals’ reimbursement by Medicare. These models are called the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. Private insurers are also committed to performance-based payment models. In 2017 Forbes reported that almost 50% of insurers’ reimbursements were in the form of value-based care models.[42]

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program

The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (VBP) was designed to improve health care quality and patient experience by using financial incentives that encourage hospitals to follow established best clinical practices and improve patient satisfaction scores via patient satisfaction surveys. Reimbursement is based on hospital performance on measures divided into four quality domains: safety, clinical care, efficiency and cost reduction, and patient and caregiver-centered experience.[43] The VBP program rewards hospitals based on the quality of care provided to Medicare patients and not just the quantity of services that are provided. Hospitals may have their Medicaid payments reduced by up to 2% if not meeting the quality metrics.

Read more about patient satisfaction surveys.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) penalizes hospitals with higher rates of patient readmissions compared to other hospitals. HRRP was established by the Affordable Care Act and applies to patients with specific conditions, such as heart attacks, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hip or knee replacements, and coronary bypass surgery. Hospitals with poor performance receive a 3% reduction of their Medicare payments. However, it was discovered that hospitals with higher proportions of low-income patients were penalized the most, so Congress passed legislation in 2019 that divided hospitals into groups for comparison based on the socioeconomic status of their patient populations.[44]

Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program

The Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP) was established by the Affordable Care Act. This Pay for Performance model reduces payments to hospitals based on poor performance regarding patient safety and hospital-acquired conditions, such as surgical site infections, hip fractures resulting from falls, and pressure injuries. This model has saved Medicare approximately $350 million per year.[45]

The HACRP model measures the incidence of hospital-acquired conditions, including central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), surgical site infections (SSI), Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA), and Clostridium Difficile (C. diff).[46] As a result, nurses have seen changes in daily practices based on evidence-based practices related to these conditions. For example, stringent documentation is now required for clients with Foley catheters that indicates continued need and associated infection control measures.

Other CMS Pay for Performance Models

CMS has created other value-based payment programs for agencies other than hospitals, including the End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Quality Initiative Program, the Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Program (SNFVBP), the Home Health Value-Based Program (HHVBP), and the Value Modifier (VM) Program. The VM program is aimed at Medicare Part B providers who receive high, average, or low ratings based on quality and cost measurements as compared to peer agencies.

Impacts of Value-Based Payment

Pay for Performance (i.e., value-based payment) stresses quality over quantity of care and allows health care payers to use reimbursement to encourage best clinical practices and promote positive health outcomes. It focuses on transparency by using metrics that are publicly reported, thus incentivizing organizations to protect and strengthen their reputations. In this manner, Pay for Performance models encourage accountability and consumer-informed choice.[47] See Figure 8.8[48] for an illustration of Pay for Performance.

Pay for Performance models have reduced health care costs and decreased the incidence of poor patient outcomes. For example, 30-day hospital readmission rates have been falling since 2012, indicating HRRP and HACRP are having an impact.[49]

However, there are also disadvantages to value-based payment. As previously discussed, initial research indicated hospitals with higher proportions of low-income patients were being penalized the most, resulting in additional legislation to compare hospital performance in groups based on their clients’ socioeconomic status. Nursing leaders continue to emphasize strategies that further address social determinants of health and promote health equity.[50] Read more about equity and social determinants of health in the following subsection.

Nursing Considerations

Nurses have a direct impact on activities related to quality care and reimbursement rates received by their employer. There are several categories of actions nurses can take to improve quality patient care, reduce costs, and improve reimbursement. By incorporating these actions into their daily care, nurses can help ensure the funding they need to provide quality patient care is received by their employer and resources are allocated appropriately to their patients.

The following categories of actions to improve quality of care are based on the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System and Crossing the Quality Chasm[51]:

- Effectiveness and Efficiency: Nurses support their institution's effectiveness and efficiency with individualized nursing care planning, good documentation, and care coordination. With accurate and timely documentation and care coordination, there is reduced care duplication and waste. Coordinating care also helps to reduce the risk of hospital readmissions.

- Timeliness: Nurses positively impact timeliness by prioritizing and delegating care. This helps reduce patient wait times and delays in care.

Read more about these concepts in the “Delegation and Supervision” and “Prioritization” chapters in this book.

- Safety: Nurses pay attention to their patients’ changing conditions and effectively communicate these changes with appropriate health care team members. They take any concerns about client care up the chain of command until their concerns are resolved.

- Patient-Centered Care: Nurses support this quality measure by ensuring nursing care plans are individualized for each patient. Effective care plans can improve patient compliance, resulting in improved patient outcomes.

- Evidence-Based Practice: Nurses provide care based on evidence-based practice. Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is defined by the American Nurses Association as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and patient, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[52] EBP is a component of Scholarly Inquiry, one of the ANA’s Standards of Professional Practice. Nurses’ implementation of EBP ensures proper resources are allocated to the appropriate clients. EBP promotes safe, efficient, and effective health care.[53],[54]

Read more information about EBP in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter of this book.

- Equity: Health care institutions care for all members of their community regardless of client demographics and their associated social determinants of health (SDOH). SDOH are conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes. Health disparities in communities with poor SDOH have been consistently documented in reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[55]

Nurses address negative determinants of health by advocating for interventions that reduce health disparities and promote the delivery of equitable health care resources. The term health disparities describes the differences in health outcomes that result from SDOH. Advocating for resources that enhance quality of life can significantly influence a community's health outcomes. Examples of resources that promote health include safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free of life-threatening toxins.

A related term is health care disparity that refers to differences in access to health care and insurance coverage. Health disparities and health care disparities can lead to decreased quality of life, increased personal costs, and lower life expectancy. More broadly, these disparities also translate to greater societal costs, such as the financial burden of uncontrolled chronic illnesses. An example of nurses addressing health care disparities are nurse practitioners providing health care according to their scope of practice to underserved populations in rural communities.

The ANA promotes nurse advocacy in workplaces and local communities. There are many ways nurses can promote health and wellness within their communities through a variety of advocacy programs at the federal, state, and community level.[56] Read more about advocacy and reducing health disparities in the following boxes.

Read more about ANA Policy and Advocacy.

Read more information in the “Advocacy” chapter of this book.

Read more about addressing health disparities in the “Diverse Patients” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

As discussed in the previous section, hospitals and health care providers are paid for services provided to individuals by government insurance programs (such as Medicare and Medicaid), private insurance companies, or people using their out-of-pocket funds. Traditionally, health care institutions were paid based on a “fee-for-service” model. For example, if a patient was admitted to a hospital with pneumonia, the hospital billed that individual's insurance program for the cost of care.

However, as part of a recent national strategy to reduce health care costs, insurance providers have transitioned to "Pay for Performance" reimbursement models that are based on overall agency performance and patient outcomes.

Pay for Performance

Pay for Performance, also known as value-based payment, refers to reimbursement models that attach financial incentives to the performance of health care agencies and providers. Pay for Performance models tie higher reimbursement payments to positive patient outcomes, best practices, and patient satisfaction, thus aligning payment with value and quality.[57] Nurses support higher reimbursement levels to their employers based on their documentation related to nursing care plans and achievement of expected patient outcomes.

There are two Pay for Performance models. The first model rewards hospitals and providers with higher reimbursement payments based on how well they perform on process, quality, and efficiency measures. The second model penalizes hospitals and providers for subpar performance by reducing reimbursement amounts.[58] For example, Medicare no longer reimburses hospitals to treat patients who acquire certain preventable conditions during their hospital stay, such as pressure injuries or urinary tract infections associated with use of catheters.[59]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), spurred by the Affordable Care Act, has led the way in value-based payment with a variety of payment models. CMS is the largest health care funder in the United States with almost 40% of overall health care spending for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS developed three Pay for Performance models that impact hospitals’ reimbursement by Medicare. These models are called the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. Private insurers are also committed to performance-based payment models. In 2017 Forbes reported that almost 50% of insurers’ reimbursements were in the form of value-based care models.[60]