6.2 Basic Ethical Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines morality as “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals or groups within communities and societies,” whereas ethics is the formal study of morality from a wide range of perspectives.[1] Ethical behavior is considered to be such an important aspect of nursing the ANA has designated Ethics as the first Standard of Professional Performance. The ANA Standards of Professional Performance are “authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.” See the following box for the competencies associated with the ANA Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[2]:

Competencies of ANA’s Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[3]

- Uses the Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements as a moral foundation to guide nursing practice and decision-making.

- Demonstrates that every person is worthy of nursing care through the provision of respectful, person-centered, compassionate care, regardless of personal history or characteristics (Beneficence).

- Advocates for health care consumer perspectives, preferences, and rights to informed decision-making and self-determination (Respect for autonomy).

- Demonstrates a primary commitment to the recipients of nursing and health care services in all settings and situations (Fidelity).

- Maintains therapeutic relationships and professional boundaries.

- Safeguards sensitive information within ethical, legal, and regulatory parameters (Nonmaleficence).

- Identifies ethics resources within the practice setting to assist and collaborate in addressing ethical issues.

- Integrates principles of social justice in all aspects of nursing practice (Justice).

- Refines ethical competence through continued professional education and personal self-development activities.

- Depicts one’s professional nursing identity through demonstrated values and ethics, knowledge, leadership, and professional comportment.

- Engages in self-care and self-reflection practices to support and preserve personal health, well-being, and integrity.

- Contributes to the establishment and maintenance of an ethical environment that is conducive to safe, quality health care.

- Collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, enhance cultural sensitivity and congruence, and reduce health disparities.

- Represents the nursing perspective in clinic, institutional, community, or professional association ethics discussions.

Reflective Questions

- What Ethics competencies have you already demonstrated during your nursing education?

- What Ethics competencies are you most interested in mastering?

- What questions do you have about the ANA’s Ethics competencies?

The ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements is an ethical standard that guides nursing practice and ethical decision-making.[4] This section will review several basic ethical concepts related to the ANA’s Ethics Standard of Professional Performance, such as values, morals, ethical theories, ethical principles, and the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses.

Values

Values are individual beliefs that motivate people to act one way or another and serve as guides for behavior considered “right” and “wrong.” People tend to adopt the values with which they were raised and believe those values are “right” because they are the values of their culture. Some personal values are considered sacred and moral imperatives based on an individual’s religious beliefs.[5] See Figure 6.1[6] for an image depicting choosing right from wrong actions.

In addition to personal values, organizations also establish values. The American Nurses Association (ANA) Professional Nursing Model states that nursing is based on values such as caring, compassion, presence, trustworthiness, diversity, acceptance, and accountability. These values emerge from nursing practice beliefs, such as the importance of relationships, service, respect, willingness to bear witness, self-determination, and the pursuit of health.[7] As a result of these traditional values and beliefs by nurses, Americans have ranked nursing as the most ethical and honest profession in Gallup polls since 1999, with the exception of 2001, when firefighters earned the honor after the attacks on September 11.[8]

The National League of Nursing (NLN) has also established four core values for nursing education: caring, integrity, diversity, and excellence[9]:

- Caring: Promoting health, healing, and hope in response to the human condition.

- Integrity: Respecting the dignity and moral wholeness of every person without conditions or limitations.

- Diversity: Affirming the uniqueness of and differences among persons, ideas, values, and ethnicities.

- Excellence: Cocreating and implementing transformative strategies with daring ingenuity.

Morals

Morals are the prevailing standards of behavior of a society that enable people to live cooperatively in groups. “Moral” refers to what societies sanction as right and acceptable. Most people tend to act morally and follow societal guidelines, and most laws are based on the morals of a society. Morality often requires that people sacrifice their own short-term interests for the benefit of society. People or entities that are indifferent to right and wrong are considered “amoral,” while those who do evil acts are considered “immoral.”[11]

Ethical Theories

There are two major types of ethical theories that guide values and moral behavior referred to as deontology and consequentialism.

Deontology is an ethical theory based on rules that distinguish right from wrong. See Figure 6.2[12] for a word cloud illustration of deontology. Deontology is based on the word deon that refers to “duty.” It is associated with philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant believed that ethical actions follow universal moral laws, such as, “Don’t lie. Don’t steal. Don’t cheat.”[13] Deontology is simple to apply because it just requires people to follow the rules and do their duty. It doesn’t require weighing the costs and benefits of a situation, thus avoiding subjectivity and uncertainty.[14],[15],[16]

The nurse-patient relationship is deontological in nature because it is based on the ethical principles of beneficence and maleficence that drive clinicians to “do good” and “avoid harm.”[17] Ethical principles will be discussed further in this chapter.

Consequentialism is an ethical theory used to determine whether or not an action is right by the consequences of the action. See Figure 6.3[19] for an illustration of weighing the consequences of an action in consequentialism. For example, most people agree that lying is wrong, but if telling a lie would help save a person’s life, consequentialism says it’s the right thing to do. One type of consequentialism is utilitarianism. Utilitarianism determines whether or not actions are right based on their consequences with the standard being achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people.[20],[21],[22] For this reason, utilitarianism tends to be society-centered. When applying utilitarian ethics to health care resources, money, time, and clinician energy are considered finite resources that should be appropriately allocated to achieve the best health care for society.[23]

Utilitarianism can be complicated when accounting for values such as justice and individual rights. For example, assume a hospital has four patients whose lives depend upon receiving four organ transplant surgeries for a heart, lung, kidney, and liver. If a healthy person without health insurance or family support experiences a life-threatening accident and is considered brain dead but is kept alive on life-sustaining equipment in the ICU, the utilitarian framework might suggest the organs be harvested to save four lives at the expense of one life.[24] This action could arguably produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people, but the deontological approach could argue this action would be unethical because it does not follow the rule of “do no harm.”

Read more about Decision making on organ donation: The dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors.

Interestingly, deontological and utilitarian approaches to ethical issues may result in the same outcome, but the rationale for the outcome or decision is different because it is focused on duty (deontologic) versus consequences (utilitarian).

Societies and cultures have unique ethical frameworks that may be based upon either deontological or consequentialist ethical theory. Culturally derived deontological rules may apply to ethical issues in health care. For example, a traditional Chinese philosophy based on Confucianism results in a culturally acceptable practice of family members (rather than the client) receiving information from health care providers about life-threatening medical conditions and making treatment decisions. As a result, cancer diagnoses and end-of-life treatment options may not be disclosed to the client in an effort to alleviate the suffering that may arise from knowledge of their diagnosis. In this manner, a client’s family and the health care provider may ethically prioritize a client’s psychological well-being over their autonomy and self-determination.[26] However, in the United States, this ethical decision may conflict with HIPAA Privacy Rules and the ethical principle of patient autonomy. As a result, a nurse providing patient care in this type of situation may experience an ethical dilemma. Ethical dilemmas are further discussed in the “Ethical Dilemmas” section of this chapter.

See Table 6.2 comparing common ethical issues in health care viewed through the lens of deontological and consequential ethical frameworks.

Table 6.2. Ethical Issues Through the Lens of Deontological or Consequential Ethical Frameworks

| Ethical Issue | Deontological View | Consequential View |

|---|---|---|

| Abortion | Abortion is unacceptable based on the rule of preserving life. | Abortion may be acceptable in cases of an unwanted pregnancy, rape, incest, or risk to the mother. |

| Bombing an area with known civilians | Killing civilians is not acceptable due to the loss of innocent lives. | The loss of innocent lives may be acceptable if the bombing stops a war that could result in significantly more deaths than the civilian casualties. |

| Stealing | Taking something that is not yours is wrong. | Taking something to redistribute resources to others in need may be acceptable. |

| Killing | It is never acceptable to take another human being’s life. | It may be acceptable to take another human life in self-defense or to prevent additional harm they could cause others. |

| Euthanasia/physician- assisted suicide | It is never acceptable to assist another human to end their life prematurely. | End-of-life care can be expensive and emotionally upsetting for family members. If a competent, capable adult wishes to end their life, medically supported options should be available. |

| Vaccines | Vaccination is a personal choice based on religious practices or other beliefs. | Recommended vaccines should be mandatory for everyone (without a medical contraindication) because of its greater good for all of society. |

Ethical Principles and Obligations

Ethical principles are used to define nurses’ moral duties and aid in ethical analysis and decision-making.[27] Although there are many ethical principles that guide nursing practice, foundational ethical principles include autonomy (self-determination), beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), justice (fairness), fidelity (keep promises), and veracity (tell the truth).

Autonomy

The ethical principle of autonomy recognizes each individual’s right to self-determination and decision-making based on their unique values, beliefs, and preferences. See Figure 6.4[28] for an illustration of autonomy. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines autonomy as the “capacity to determine one’s own actions through independent choice, including demonstration of competence.”[29] The nurse’s primary ethical obligation is client autonomy.[30] Based on autonomy, clients have the right to refuse nursing care and medical treatment. An example of autonomy in health care is advance directives. Advance directives allow clients to specify health care decisions if they become incapacitated and unable to do so.

Read more about advance directives and determining capacity and competency in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

Nurses as Advocates: Supporting Autonomy

Nurses have a responsibility to act in the interest of those under their care, referred to as advocacy. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines advocacy as “the act or process of pleading for, supporting, or recommending a cause or course of action. Advocacy may be for persons (whether an individual, group, population, or society) or for an issue, such as potable water or global health.”[31] See Figure 6.5[32] for an illustration of advocacy.

Advocacy includes providing education regarding client rights, supporting autonomy and self-determination, and advocating for client preferences to health care team members and family members. Nurses do not make decisions for clients, but instead support them in making their own informed choices. At the core of making informed decisions is knowledge. Nurses serve an integral role in patient education. Clarifying unclear information, translating medical terminology, and making referrals to other health care team members (within their scope of practice) ensures that clients have the information needed to make treatment decisions aligned with their personal values.

At times, nurses may find themselves in a position of supporting a client’s decision they do not agree with and would not make for themselves or for the people they love. However, self-determination is a human right that honors the dignity and well-being of individuals. The nursing profession, rooted in caring relationships, demands that nurses have nonjudgmental attitudes and reflect “unconditional positive regard” for every client. Nurses must suspend personal judgement and beliefs when advocating for their clients’ preferences and decision-making.[33]

Beneficence

Beneficence is defined by the ANA as “the bioethical principle of benefiting others by preventing harm, removing harmful conditions, or affirmatively acting to benefit another or others, often going beyond what is required by law.”[34] See Figure 6.6[35] for an illustration of beneficence. Put simply, beneficence is acting for the good and welfare of others, guided by compassion. An example of beneficence in daily nursing care is when a nurse sits with a dying patient and holds their hand to provide presence.

Nursing advocacy extends beyond direct patient care to advocating for beneficence in communities. Vulnerable populations such as children, older adults, cultural minorities, and the homeless often benefit from nurse advocacy in promoting health equity. Cultural humility is a humble and respectful attitude towards individuals of other cultures and an approach to learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.[36] Nurses, the largest segment of the health care community, have a powerful voice when addressing community beneficence issues, such as health disparities and social determinants of health, and can serve as the conduit for advocating for change.

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence is defined by the ANA as “the bioethical principle that specifies a duty to do no harm and balances avoidable harm with benefits of good achieved.”[37] An example of doing no harm in nursing practice is reflected by nurses checking medication rights three times before administering medications. In this manner, medication errors can be avoided, and the duty to do no harm is met. Another example of nonmaleficence is when a nurse assists a client with a serious, life-threatening condition to participate in decision-making regarding their treatment plan. By balancing the potential harm with potential benefits of various treatment options, while also considering quality of life and comfort, the client can effectively make decisions based on their values and preferences.

Justice

Justice is defined by the ANA as “a moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity and a standard linked to fairness for all in society.”[38] The principle of justice requires health care to be provided in a fair and equitable way. Nurses provide quality care for all individuals with the same level of fairness despite many characteristics, such as the individual’s financial status, culture, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Nurses have a social contract to “provide compassionate care that addresses the individual’s needs for protection, advocacy, empowerment, optimization of health, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering, comfort, and well-being.”[39] An example of a nurse using the principle of justice in daily nursing practice is effective prioritization based on client needs.

Read more about prioritization models in the “Prioritization” chapter.

Other Ethical Principles

Additional ethical principles commonly applied to health care include fidelity (keeping promises) and veracity (telling the truth). An example of fidelity in daily nursing practice is when a nurse tells a client, “I will be back in an hour to check on your pain level.” This promise is kept. An example of veracity in nursing practice is when a nurse honestly explains potentially uncomfortable side effects of prescribed medications. Determining how truthfulness will benefit the client and support their autonomy is dependent on a nurse’s clinical judgment, self-reflection, knowledge of the patient and their cultural beliefs, and other factors.[40]

A principle historically associated with health care is paternalism. Paternalism is defined as the interference by the state or an individual with another person, defended by the claim that the person interfered with will be better off or protected from harm.[41] Paternalism is the basis for legislation related to drug enforcement and compulsory wearing of seatbelts.

In health care, paternalism has been used as rationale for performing treatment based on what the provider believes is in the client’s best interest. In some situations, paternalism may be appropriate for individuals who are unable to comprehend information in a way that supports their informed decision-making, but it must be used cautiously to ensure vulnerable individuals are not misused and their autonomy is not violated.

Nurses may find themselves acting paternalistically when performing nursing care to ensure client health and safety. For example, repositioning clients to prevent skin breakdown is a preventative intervention commonly declined by clients when they prefer a specific position for comfort. In this situation, the nurse should explain the benefits of the preventative intervention and the risks if the intervention is not completed. If the client continues to decline the intervention despite receiving this information, the nurse should document the education provided and the client’s decision to decline the intervention. The process of reeducating the client and reminding them of the importance of the preventative intervention should be continued at regular intervals and documented.

Care-Based Ethics

Nurses use a client-centered, care-based ethical approach to patient care that focuses on the specific circumstances of each situation. This approach aligns with nursing concepts such as caring, holism, and a nurse-client relationship rooted in dignity and respect through virtues such as kindness and compassion.[42],[43] This care-based approach to ethics uses a holistic, individualized analysis of situations rather than the prescriptive application of ethical principles to define ethical nursing practice. This care-based approach asserts that ethical issues cannot be handled deductively by applying concrete and prefabricated rules, but instead require social processes that respect the multidimensionality of problems.[44] Frameworks for resolving ethical situations are discussed in the “Ethical Dilemmas” section of this chapter.

Nursing Code of Ethics

Many professions and institutions have their own set of ethical principles, referred to as a code of ethics, designed to govern decision-making and assist individuals to distinguish right from wrong. The American Nurses Association (ANA) provides a framework for ethical nursing care and guides nurses during decision-making in its formal document titled Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements (Nursing Code of Ethics). The Nursing Code of Ethics serves the following purposes[45]:

- It is a succinct statement of the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively.

- It is the profession’s nonnegotiable ethical standard.

- It is an expression of nursing’s own understanding of its commitment to society.

The preface of the ANA’s Nursing Code of Ethics states, “Individuals who become nurses are expected to adhere to the ideals and moral norms of the profession and also to embrace them as a part of what it means to be a nurse. The ethical tradition of nursing is self-reflective, enduring, and distinctive. A code of ethics makes explicit the primary goals, values, and obligations of the profession.”[46]

The Nursing Code of Ethics contains nine provisions. Each provision contains several clarifying or “interpretive” statements. Read a summary of the nine provisions in the following box.

Nine Provisions of the ANA Nursing Code of Ethics

- Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

- Provision 2: The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

- Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

- Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.

- Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

- Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

- Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

- Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

- Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

Read the free, online full version of the ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements.

In addition to the Nursing Code of Ethics, the ANA established the Center for Ethics and Human Rights to help nurses navigate ethical conflicts and life-and-death decisions common to everyday nursing practice.

Read more about the ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights.

Specialty Organization Code of Ethics

Many specialty nursing organizations have additional codes of ethics to guide nurses practicing in settings such as the emergency department, home care, or hospice care. These documents are unique to the specialty discipline but mirror the statements from the ANA’s Nursing Code of Ethics. View ethical statements of various specialty nursing organizations using the information in the following box.

Ethical Statements of Selected Specialty Nursing Organizations

Media Attributions

- ethics-2991600_1920

- ethics-947572_1920

- balance-6097898

- Autonomy and Self-Determination

- Advocacy

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- Ethics Unwrapped - McCombs School of Business. (n.d.). Ethics defined (a glossary). University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary ↵

- “ethics-2991600_1920” by Tumisu is licensed under CC0 1.0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Gaines, K. (2021, January 19). Nurses ranked most trusted profession 19 years in a row. Nurse.org. https://nurse.org/articles/nursing-ranked-most-honest-profession/ ↵

- National League for Nursing. Core values. https://www.nln.org/about/about/core-values ↵

- McCombs School of Business. (2018, December 18). Values | Ethics defined [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/SCjYaatMJuY ↵

- Ethics Unwrapped - McCombs School of Business. (n.d.). Ethics defined (a glossary). University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary ↵

- “ethics-947572_1920” by rdaconnect at Pixabay.com is licensed under CC0 1.0 ↵

- Ethics Unwrapped - McCombs School of Business. (n.d.). Ethics defined (a glossary). University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary ↵

- Alexander, L., & Moore, M. (2020, October 30). Deontological ethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-deontological/ ↵

- Ethics Unwrapped - McCombs School of Business. (n.d.). Ethics defined (a glossary). University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Mandal, J., Ponnambath, D. K., & Parija, S. C. (2016). Utilitarian and deontological ethics in medicine. Tropical Parasitology, 6(1), 5–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5070.175024 ↵

- McCombs School of Business. (2018, December 18). Deontology | Ethics defined [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/wWZi-8Wji7M ↵

- “balance-6097898_1280” by mohamed_hassan is licensed under CC0 1.0 ↵

- Alexander, L., & Moore, M. (2020, October 30). Deontological ethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-deontological/ ↵

- Ethics Unwrapped - McCombs School of Business. (n.d.). Ethics defined (a glossary). University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Mandal, J., Ponnambath, D. K., & Parija, S. C. (2016). Utilitarian and deontological ethics in medicine. Tropical Parasitology, 6(1), 5–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5070.175024 ↵

- Ethics Unwrapped - McCombs School of Business. (n.d.). Ethics defined (a glossary). University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary ↵

- McCombs School of Business. (2018, December 18). Consequentialism | Ethics defined [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/51DZteag74A ↵

- Wang, H., Zhao, F., Wang, X., & Chen, X. (2018). To tell or not: The Chinese doctors' dilemma on disclosure of a cancer diagnosis to the patient. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 47(11), 1773–1774. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30581799 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Autonomy and Self-Determination.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- “Advocacy” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- “Air_Force_special_operations_medical_team_saves_lives,_helps_shape_future_of_Afghan_medicine_111010-F-QW942-082.jpg” by Senior Airman Tyler Placie is in the Public Domain ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Dworkin, G. (2020, September 9). Paternalism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/paternalism/ ↵

- Fry, S. T. (1989). The role of caring in a theory of nursing ethics. Hypatia, 4(2), 87-103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1989.tb00575.x ↵

- Taylor, C. (1993). Nursing ethics: The role of caring. Awhonn's Clinical Issues in Perinatal and Women's Health Nursing, 4(4), 552-560. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8220369/ ↵

- Schuchter, P., & Heller, A. (2018). The care dialog: The "ethics of care" approach and its importance for clinical ethics consultation. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 21(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-017-9784-z ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- ABCs: Airway, breathing, and circulation.

- Accountability: Being answerable to oneself and others for one’s own choices, decisions, and actions as measured against a standard.

- Actual problems: Nursing problems currently occurring with the patient.

- Acuity: The level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition.

- Acuity-rating staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments that reflects the individualized nursing care required for different types of patients.

- Acute conditions: Conditions having a sudden onset.

- Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN): An RN who has a graduate degree and advanced knowledge. There are four categories of APRNs: certified nurse-midwife (CNM), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), certified nurse practitioner (CNP), or certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). These nurses can diagnose illnesses and prescribe treatments and medications.[1] (Chapter 1.4)ANA Standards of Professional Nursing Practice: Authoritative statements of the duties that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, or specialty, are expected to perform competently. The Standards of Professional Nursing Practice describe a competent level of nursing practice as demonstrated by the critical thinking model known as the nursing process. The nursing process includes the components of assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation.[2] (Chapter 1.3)

ANA Standards of Professional Performance: Standards that describe a competent level of behavior in the professional role of the nurse, including activities related to ethics, advocacy, respectful and equitable practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, scholarly inquiry, quality of practice, professional practice evaluation, resource stewardship, and environmental health.[3] (Chapter 1.3)

Assignment: Routine care, activities, and procedures that are within the authorized scope of practice of the RN, LPN/VN, or routine functions of the assistive personnel.

Assistive Personnel (AP): Any assistive personnel (formerly referred to as ‘‘unlicensed” assistive personnel [UAP]) trained to function in a supportive role, regardless of title, to whom a nursing responsibility may be delegated. This includes, but is not limited to, certified nursing assistants or aides (CNAs), patient-care technicians (PCTs), certified medical assistants (CMAs), certified medication aides, and home health aides.[4] - Basic nursing care: Care that can be performed following a defined nursing procedure with minimal modification in which the responses of the patient to the nursing care are predictable.[5] (Chapter 1.4)

- Board of Nursing: The state-specific licensing and regulatory body that sets the standards for safe nursing care, decides the scope of practice for nurses within its jurisdiction, and issues licenses to qualified candidates. (Chapter 1.3)

- Certification: The formal recognition of specialized knowledge, skills, and experience demonstrated by the achievement of standards identified by a nursing specialty. (Chapter 1.4)

- Chain of command: A hierarchy of reporting relationships in an agency that establishes accountability and lays out lines of authority and decision-making power. (Chapter 1.4)

- Chronic conditions: Conditions that have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time.

- Clinical reasoning: “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[6]

- Closed-loop communication: A process that enables the person giving the instructions to hear what they said reflected back and to confirm that their message was, in fact, received correctly.

- Code of ethics: A code that applies normative, moral guidance for nurses in terms of what they ought to do, be, and seek. A code of ethics makes the primary obligations, values, and ideals of a profession explicit. (Chapter 1.6)

- Constructive feedback: Supportive feedback that offers solutions to areas of weakness.

- Critical thinking: A broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”[7]

- CURE hierarchy: A strategy for prioritization based on identifying “critical” needs, “urgent” needs, “routine” needs, and “extras.”

- Data cues: Pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition.

- Delegated responsibility: A nursing activity, skill, or procedure that is transferred from a license nurse to a delegatee.

- Delegatee: An RN, LPN/VN, or AP who is delegated a nursing responsibility by either an APRN, RN, or LPN/VN who is competent to perform the task and verbally accepts the responsibility.

- Delegation: Allowing a delegatee to perform a specific nursing activity, skill, or procedure that is beyond the delegatee’s traditional role but in which they have received additional training.

- Delegator: An APRN, RN, or LPN/VN who requests a specially trained delegatee to perform a specific nursing activity, skill, or procedure that is beyond the delegatee’s traditional role.

- Dysphagia: Impaired swallowing. (Chapter 1.4)

- Ethical principle: An ethical principle is a general guide, basic truth, or assumption that can be used with clinical judgment to determine a course of action. Four common ethical principles are beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), autonomy (control by the individual), and justice (fairness). (Chapter 1.6)

- Evidence-based practice: A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and client, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.[8] (Chapter 1.8)

- Expected conditions: Conditions that are likely to occur or anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury.

- Expressive aphasia: The impaired ability to form words and speak. (Chapter 1.4)

- Five rights of delegation: Right task, right circumstance, right person, right directions and communication, and right supervision and evaluation.

- Licensed Practical Nurse/Vocational Nurse (LPN/LVN): An individual who has completed a state-approved practical or vocational nursing program, passed the NCLEX-PN examination, and is licensed by their state Board of Nursing to provide client care.[9] (Chapter 1.4, Chapter 1.5)

- Malpractice: A specific term that looks at a standard of care, as well as the professional status of the caregiver.[10] (Chapter 1.6)

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Prioritization strategies often reflect the foundational elements of physiological needs and safety and progress toward higher levels.

- Morality: Personal values, character, or conduct of individuals within communities and societies.[11] (Chapter 1.6)

- Negligence: A “general term that denotes conduct lacking in due care, carelessness, and a deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would use in a particular set of circumstances.”[12] (Chapter 1.6)

- Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC): Allows a nurse to have one multistate license with the ability to practice in the home state and other compact states. (Chapter 1.5)

- Nurse Practice Act (NPA): Legislation enacted by each state that establishes regulations for nursing practice within that state by defining the requirements for licensure, as well as the scope of nursing practice. (Chapter 1.3)

- Nursing team members: Advanced practice registered nurses (APRN), registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VN), and assistive personnel (AP).

- Nursing: Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focused on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.[13] (Chapter 1.3)

- Patient confidentiality: Keeping your client’s Protected Health Information (PHI) protected and known only by those health care team members directly providing care for the client. (Chapter 1.6)

- Primary care: Care that is provided to clients to promote wellness and prevent disease from occurring. This includes health promotion, education, protection (such as immunizations), early disease screening, and environmental considerations. (Chapter 1.4)

- Protocol: A precise and detailed written plan for a regimen of therapy.[14] (Chapter 1.3)

- Provider: A physician, podiatrist, dentist, optometrist, or advanced practice nurse provider.[15] (Chapter 1.4)

- Quality improvement: Combined and unceasing efforts of everyone–healthcare professionals, clients and their families, researchers, payers, planners and educators–to make the changes that will lead to better client outcomes (health), better system performance (care) and better professional development (learning). (Chapter 1.8)

- Quality: The degree to which nursing services for health care consumers, families, groups, communities, and populations increase the likelihood of desirable outcomes and are consistent with evolving nursing knowledge.”[16] (Chapter 1.8)

- Ratio-based staffing models: A staffing model used to make patient assignments in terms of one nurse caring for a set number of patients.

- Registered Nurse (RN): An individual who has graduated from a state-approved school of nursing, passed the NCLEX-RN examination, and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide client care.[17] (Chapter 1.4, Chapter 1.5)

- Risk problem: A nursing problem that reflects that a patient may experience a problem but does not currently have signs reflecting the problem is actively occurring.

- Safety culture: A culture established within health care agencies that empowers nurses, nursing students, and other staff members to speak up about risks to clients and to report errors and near misses, all of which drive improvement in client care and reduce the incident of client harm. (Chapter 1.3)

- Scope of practice: Procedures, actions, and processes that a health care practitioner is permitted to undertake in keeping with the terms of their professional license.

- Scope of practice: Services that a qualified health professional is deemed competent to perform and permitted to undertake – in keeping with the terms of their professional license. (Chapter 1.1)

- Secondary care: Care that occurs when a person has contracted an illness or injury and is in need of medical care. (Chapter 1.4)

- Tertiary care: A type of care that deals with the long-term effects from chronic illness or condition, with the purpose to restore physical and mental function that may have been lost. The goal is to achieve the highest level of functioning possible with this chronic illness. (Chapter 1.4)

- Time estimation: A prioritization strategy including the review of planned tasks and allocation of time believed to be required to complete each task.

- Time scarcity: A feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against you.

- Unexpected conditions: Conditions that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury.

- Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP): Any unlicensed person, regardless of title, who performs tasks delegated by a nurse. This includes certified nursing aides/assistants (CNAs), patient care assistants (PCAs), patient care technicians (PCTs), state tested nursing assistants (STNAs), nursing assistants-registered (NA/Rs) or certified medication aides/assistants (MA-Cs). Certification of UAPs varies between jurisdictions.[18] (Chapter 1.4)

Change is constant in the health care environment. Change is defined as the process of altering or replacing existing knowledge, skills, attitudes, systems, policies, or procedures.[19] The outcomes of change must be consistent with an organization’s mission, vision, and values. Although change is a dynamic process that requires alterations in behavior and can cause conflict and resistance, change can also stimulate positive behaviors and attitudes and improve organizational outcomes and employee performance. Change can result from identified problems or from the incorporation of new knowledge, technology, management, or leadership. Problems may be identified from many sources, such as quality improvement initiatives, employee performance evaluations, or accreditation survey results.[20]

Nurse managers must deal with the fears and concerns triggered by change. They should recognize that change may not be easy and may be met with enthusiasm by some and resistance by others. Leaders should identify individuals who will be enthusiastic about the change (referred to as “early adopters”), as well as those who will be resisters (referred to as "laggers"). Early adopters should be involved to build momentum, and the concerns of resisters should be considered to identify barriers. Data should be collected, analyzed, and communicated so the need for change (and its projected consequences) can be clearly articulated. Managers should articulate the reasons for change, the way(s) the change will affect employees, the way(s) the change will benefit the organization, and the desired outcomes of the change process.[21] See Figure 4.5[22] for an illustration of communicating upcoming change.

Change Theories

There are several change theories that nurse leaders may adopt when implementing change. Two traditional change theories are known as Lewin’s Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze Model and Lippitt’s Seven-Step Change Theory.[23]

Lewin’s Change Model

Kurt Lewin, the father of social psychology, introduced the classic three-step model of change known as Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze Model that requires prior learning to be rejected and replaced. Lewin’s model has three major concepts: driving forces, restraining forces, and equilibrium. Driving forces are those that push in a direction and cause change to occur. They facilitate change because they push the person in a desired direction. They cause a shift in the equilibrium towards change. Restraining forces are those forces that counter the driving forces. They hinder change because they push the person in the opposite direction. They cause a shift in the equilibrium that opposes change. Equilibrium is a state of being where driving forces equal restraining forces, and no change occurs. It can be raised or lowered by changes that occur between the driving and restraining forces.[24],[25]

- Step 1: Unfreeze the status quo. Unfreezing is the process of altering behavior to agitate the equilibrium of the current state. This step is necessary if resistance is to be overcome and conformity achieved. Unfreezing can be achieved by increasing the driving forces that direct behavior away from the existing situation or status quo while decreasing the restraining forces that negatively affect the movement from the existing equilibrium. Nurse leaders can initiate activities that can assist in the unfreezing step, such as motivating participants by preparing them for change, building trust and recognition for the need to change, and encouraging active participation in recognizing problems and brainstorming solutions within a group.[26]

- Step 2: Change. Change is the process of moving to a new equilibrium. Nurse leaders can implement actions that assist in movement to a new equilibrium by persuading employees to agree that the status quo is not beneficial to them; encouraging them to view the problem from a fresh perspective; working together to search for new, relevant information; and connecting the views of the group to well-respected, powerful leaders who also support the change.[27]

- Step 3: Refreeze. Refreezing refers to attaining equilibrium with the newly desired behaviors. This step must take place after the change has been implemented for it to be sustained over time. If this step does not occur, it is very likely the change will be short-lived and employees will revert to the old equilibrium. Refreezing integrates new values into community values and traditions. Nursing leaders can reinforce new patterns of behavior and institutionalize them by adopting new policies and procedures.[28]

Example Using Lewin’s Change Theory

A new nurse working in a rural medical-surgical unit identifies that bedside handoff reports are not currently being used during shift reports.

Step 1: Unfreeze: The new nurse recognizes a change is needed for improved patient safety and discusses the concern with the nurse manager. Current evidence-based practice is shared regarding bedside handoff reports between shifts for patient safety.[29] The nurse manager initiates activities such as scheduling unit meetings to discuss evidence-based practice and the need to incorporate bedside handoff reports.

Step 2: Change: The nurse manager gains support from the director of nursing to implement organizational change and plans staff education about bedside report checklists and the manner in which they are performed.

Step 3: Refreeze: The nurse manager adopts bedside handoff reports in a new unit policy and monitors staff for effectiveness.

Lippitt’s Seven-Step Change Theory

Lippitt’s Seven-Step Change Theory expands on Lewin’s change theory by focusing on the role of the change agent. A change agent is anyone who has the skill and power to stimulate, facilitate, and coordinate the change effort. Change agents can be internal, such as nurse managers or employees appointed to oversee the change process, or external, such as an outside consulting firm. External change agents are not bound by organizational culture, politics, or traditions, so they bring a different perspective to the situation and challenge the status quo. However, this can also be a disadvantage because external change agents lack an understanding of the agency's history, operating procedures, and personnel.[30] The seven-step model includes the following steps[31]:

- Step 1: Diagnose the problem. Examine possible consequences, determine who will be affected by the change, identify essential management personnel who will be responsible for fixing the problem, collect data from those who will be affected by the change, and ensure those affected by the change will be committed to its success.

- Step 2: Evaluate motivation and capability for change. Identify financial and human resources capacity and organizational structure.

- Step 3: Assess the change agent’s motivation and resources, experience, stamina, and dedication.

- Step 4: Select progressive change objectives. Define the change process and develop action plans and accompanying strategies.

- Step 5: Explain the role of the change agent to all employees and ensure the expectations are clear.

- Step 6: Maintain change. Facilitate feedback, enhance communication, and coordinate the effects of change.

- Step 7: Gradually terminate the helping relationship of the change agent.

Example Using Lippitt’s Seven-Step Change Theory

Refer to the previous example of using Lewin’s change theory on a medical-surgical unit to implement bedside handoff reporting. The nurse manager expands on the Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze Model by implementing additional steps based on Lippitt’s Seven-Step Change Theory:

- The nurse manager collects data from team members affected by the changes and ensures their commitment to success.

- Early adopters are identified as change agents on the unit who are committed to improving patient safety by implementing evidence-based practices such as bedside handoff reporting.

- Action plans (including staff education and mentoring), timelines, and expectations are clearly communicated to team members as progressive change objectives. Early adopters are trained as “super-users” to provide staff education and mentor other nurses in using bedside handoff checklists across all shifts.

- The nurse manager facilitates feedback and encourages two-way communication about challenges as change is implemented on the unit. Positive reinforcement is provided as team members effectively incorporate change.

- Bedside handoff reporting is implemented as a unit policy, and all team members are held accountable for performing accurate bedside handoff reporting.

Read more about additional change theories in the Current Theories of Change Management pdf.

Change Management

Change management is the process of making changes in a deliberate, planned, and systematic manner.[32] It is important for nurse leaders and nurse managers to remember a few key points about change management[33]:

- Employees will react differently to change, no matter how important or advantageous the change is purported to be. Recognizing this variability is crucial for effectively managing the transition process.

- Basic needs will influence reaction to change, such as the need to be part of the change process, the need to be able to express oneself openly and honestly, and the need to feel that one has some control over the impact of change. Ensuring these needs are met can significantly reduce resistance.

- Change often results in a feeling of loss due to changes in established routines. Employees may react with shock, anger, and resistance, but ideally will eventually accept and adopt change. Acknowledging these feelings and providing support can facilitate smoother transitions.

- Change must be managed realistically, without false hopes and expectations, yet with enthusiasm for the future. Employees should be provided information honestly and allowed to ask questions and express concerns. This transparency builds trust and helps in aligning everyone towards common goals.

Strategies for Effective Change Management

- Engage Stakeholders Early: Involve key stakeholders in the planning stages of the change process. Their input can provide valuable insights and help in identifying potential challenges early on.

- Communicate Clearly and Frequently: Clear and frequent communication is essential. Use multiple channels to disseminate information and ensure that the message is consistent and comprehensible to all staff members.

- Provide Training and Resources: Equip employees with the necessary skills and resources to adapt to the change. This might include training sessions, informational materials, or access to support personnel.

- Build a Supportive Culture: Create an environment where change is viewed positively. Encourage collaboration and create opportunities for employees to share their experiences and strategies for adapting to change.

- Monitor and Adjust: Continuously monitor the progress of the change initiative and be prepared to make adjustments as needed. Solicit feedback from employees and be responsive to their concerns.

There are multiple strategies that can employed to overcome resistance to change. First, it is important to understand the underlying reasons for resistance. Resistance is commonly aligned to feelings of fear, lack of trust in leadership, or logistical concerns regarding workload, seniority, etc. To implement change effectively, a leader should empower staff by making sure they feel that their voice is respected and valued. When individuals feel valued and hear, they are more likely to support change, even if they do not personally agree with all elements associated with the change. Leaders also must understand that change is stressful for individuals. Depending on the significance of change, a leader may take actions to ensure that employee assistance programs, support groups, or additional counseling services or resources are available. These additional resources can be beneficial for individuals as they work through the emotions associated with the proposed change. Additionally, the benefits for any change should be clearly described. It is important to highlight how the proposed change will help improve work processes and patient care quality. It is also helpful to acknowledge and demonstrate appreciation for early adopters of the change. This can provide motivation and encouragement for others to follow suit and fosters a positive attitude toward future changes.

Jamie has recently completed his orientation to the emergency department at a busy Level 1 trauma center. The environment is fast-paced, and there are typically a multitude of patients who require care. Jamie appreciates his colleagues and the collaboration that is reflected among members of the health care team, especially in times of stress. Jamie is providing care for an 8-year-old patient who has broken her arm when there is a call that there are three Level 1 trauma patients approximately five minutes from the ER. The trauma surgeon reports to the ER, and multiple members of the trauma team report to the ER intake bays. If you were Jamie, what leadership style would you hope the trauma surgeon uses with the team?

In a stressful clinical care situation, where rapid action and direction are needed, an autocratic leadership style is most effective. There is no time for debating different approaches to care in a situation where immediate intervention may be required. Concise commands, direction, and responsive action from the team are needed to ensure that patient care interventions are delivered quickly to enhance chance of survival and recovery.

To become a nursing advocate, identify causes, issues, or needs where YOU can exert influence.

Steps to becoming an advocate include the following[34]:

- Identify a problem that interests you: Start by pinpointing a specific issue or area within nursing that you are passionate about. This could range from patient safety and quality of care to workplace conditions and professional development opportunities.

- Research the subject and select an evidence-based intervention: Conduct thorough research on the identified issue. Look for evidence-based practices and interventions that have been proven to address or mitigate the problem effectively. Gathering robust data will help you build a solid case for your advocacy efforts.

- Network with experts who are, or could be, involved in making the change: Connect with professionals and experts who are either already involved in addressing the issue or who could play a crucial role in implementing changes. Building a network of like-minded individuals can provide support, resources, and additional perspectives.

- Work hard for change: Advocacy requires dedication and persistence. Actively participate in efforts to bring about the desired change. This might include engaging in public speaking, writing articles or blogs, meeting with policymakers, or organizing community events to raise awareness.

Once you have identified a topic of interest, it's crucial to get involved in activities that can amplify your advocacy efforts:

- Committees: Volunteer to participate in committees that review and develop practice policies within your health care institution.

- Professional Nursing Organizations: Become a member of state and national nursing organizations. These groups often provide valuable resources, including access to current legislative and policy initiatives, public policy agendas, and ways to get involved.

- Research and Review: Stay informed by researching best practices and reviewing the health policy agendas of elected officials. Understanding the current landscape will help you identify opportunities to influence policy and practice.

Nurses hold a powerful position to be effective advocates due to their frontline role in health care delivery. Their unique insights into patient care, the work environment, and health care systems make them valuable voices in policy discussions. As the largest sector of the health care workforce, nurses have significant potential to influence decisions at every level.

Advocating for change can lead to improved quality of care, better patient outcomes, and safe work environments. By pushing for evidence-based practices and policies, nurses can help ensure that patients receive the best possible care. Advocacy efforts focused on patient safety and quality can directly impact patient health and recovery. Additionally, nurses can advocate for better working conditions, which can lead to a safer and more supportive environment for all healthcare workers.

Imagine the impact if every nurse actively engaged in advocacy. The collective efforts could drive substantial improvements in health care delivery and policy, leading to positive changes across the profession.

Review information about a new professional nursing association called the Nurse Advocacy Association.

Case Study

An 85-year-old woman was admitted with sudden onset of dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and right upper arm edema. She had a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placed three weeks previously for treatment of osteomyelitis of the left hand. A caretaker had been infusing her antibiotics and managing her PICC with the oversight of a home care nurse. A chest computerized tomography scan confirmed the presence of a pulmonary embolism. She was admitted to the inpatient floor at change of shift, and orders were received for a weight-based heparin bolus and infusion. The bolus was administered, and the infusion was initiated. During handoff report to the next shift, the pump alarm sounded. In responding to the alarm, the oncoming nurse discovered that the entire bag of heparin (25,000 units) had infused in less than 30 minutes. She discovered the rate on the pump was set by the previous nurse at 600 mL/hour rather than the weight-adjusted 600 units/hour.

The oncoming nurse who discovered the heparin error immediately disconnected the infusion, assessed the client for signs of bleeding, and notified the physician of the error. Appropriate precautions were initiated and an incident report was submitted. Subsequently, an investigation was conducted by the unit supervisor and the risk manager by interviewing involved staff. They found that the client's admitting nurse, who administered the heparin bolus and infusion, was a traveling nurse who had been in the organization for three weeks and had been floated to the telemetry unit for the first time. While the traveling nurse had been trained on an orthopedic unit, she had not initiated a heparin infusion at this facility. The facility used an infusion pump that included a drug library with medication-specific infusion limits for client safety. The nurse had been trained to use the infusion pump drug library in a brief orientation, but she had witnessed several nurses bypass this safety measure. In addition, although she had her heparin bolus and infusion calculations double-checked by another nurse, she was not aware that this double-check should include a review of pump settings. Finally, because the change of shift handoff report was hurried, it did not include a bedside report to review infusions and client status with the oncoming nurse. What appeared to be a serious individual error was, in fact, a complex series of failures in the facility's safety culture that placed a nurse in the very difficult position of making an error that placed a client at risk of harm. Fortunately, no significant bleeding events occurred as a result of the error.[35]

Reflective Questions

- Create a list of safety failures in this example and categorize them based on the QSEN competencies.

- Outline communication tools and best practices that could have prevented this error from occurring.

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[36]

Learning Objectives

- Develop a current professional resume or portfolio

- Identify steps for preparing for the NCLEX-RN examination

- Identify actions for obtaining nursing credentials

- Identify strategies for successful nursing interviews

- Identify goals for lifelong learning and professional development

Preparing to enter the workforce as a registered nurse (RN) can be a challenging but exciting time. Being aware of available resources to help navigate this process will decrease stress and make the process more manageable. This chapter will discuss how to prepare for the NCLEX-RN examination, obtain a nursing license, create a resume and portfolio, effectively participate in an interview, transition into the RN role, and become a lifelong learner.

Licensure is the process by which a State Board of Nursing (SBON) grants permission to an individual to engage in nursing practice after verifying the applicant has attained the competency necessary to perform the scope of practice of a registered nurse (RN).[37] The SBON verifies these three components:

- Verification of graduation from an approved prelicensure RN nursing education program

- Verification of successful completion of NCLEX-RN examination

- A criminal background check (in some states)[38]

In the United States there are three common types of prelicensure educational programs that prepare a student to become an RN, including a two-year associate degree of nursing (ADN), a hospital-based diploma program, or a four-year baccalaureate degree (BSN). Some universities offer an "Entry Level Master of Science in Nursing Track" for non-nurses holding a baccalaureate or master's degree in another field who wish to become a nurse. All graduates must pass the same NCLEX-RN to obtain their RN license from their SBON (or other nursing regulatory body).

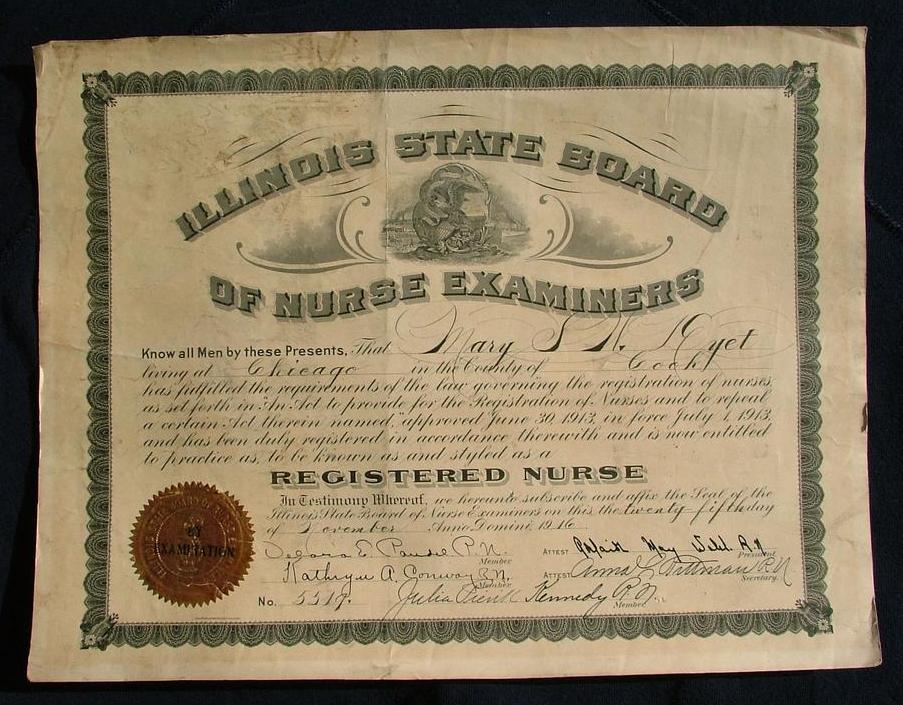

Requirements for licensure renewal vary from state to state. Some states require continued education credits (CEUs), along with the payment of fees. In Wisconsin the nursing license is renewed every two years. See Figure 11.2[39] for an image of a simulated nursing license.

- Use this map for contact information for the State Boards of Nursing.

- Read more details on obtaining a Wisconsin RN license at https://dsps.wi.gov/Pages/Professions/RN/Default.aspx.

Nurse Licensure Compact

When applying for your nursing license from your State Board of Nursing (SBON), you may also be eligible to apply for a multistate license. The Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) allows nurses to practice in other NLC states with their original state’s nursing license without having to obtain additional licenses, contingent upon remaining a resident of that state. Currently, 38 states have enacted the NLC. Read more information about the NLC using the information in the following box.

View the current Nurse Licensure Compact Map.

Read this algorithm on how to Navigate the Nurse Licensure Compact.

Read more information about the Nurse Licensure Compact Rules.

Watch a video for nursing students on the Nurse Licensure Compact.

Temporary Permit

In some states before taking the NCLEX, an applicant may apply to receive a temporary permit from their State Board of Nursing (SBON). A temporary permit allows the applicant to practice practical nursing under the direct supervision of a registered nurse until the RN license is granted. A temporary permit is typically valid for a period of three months or until the holder receives failing NCLEX results, whichever is shorter.

Read about the temporary permit available in Wisconsin.

Licensure is the process by which a State Board of Nursing (SBON) grants permission to an individual to engage in nursing practice after verifying the applicant has attained the competency necessary to perform the scope of practice of a registered nurse (RN).[40] The SBON verifies these three components:

- Verification of graduation from an approved prelicensure RN nursing education program

- Verification of successful completion of NCLEX-RN examination

- A criminal background check (in some states)[41]

In the United States there are three common types of prelicensure educational programs that prepare a student to become an RN, including a two-year associate degree of nursing (ADN), a hospital-based diploma program, or a four-year baccalaureate degree (BSN). Some universities offer an "Entry Level Master of Science in Nursing Track" for non-nurses holding a baccalaureate or master's degree in another field who wish to become a nurse. All graduates must pass the same NCLEX-RN to obtain their RN license from their SBON (or other nursing regulatory body).

Requirements for licensure renewal vary from state to state. Some states require continued education credits (CEUs), along with the payment of fees. In Wisconsin the nursing license is renewed every two years.

- Use this map for contact information for the State Boards of Nursing.

- Read more details on obtaining a Wisconsin RN license at https://dsps.wi.gov/Pages/Professions/RN/Default.aspx.

Nurse Licensure Compact

When applying for your nursing license from your State Board of Nursing (SBON), you may also be eligible to apply for a multistate license. The Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) allows nurses to practice in other NLC states with their original state’s nursing license without having to obtain additional licenses, contingent upon remaining a resident of that state. Currently, 38 states have enacted the NLC. Read more information about the NLC using the information in the following box.

View the current Nurse Licensure Compact Map.

Read this algorithm on how to Navigate the Nurse Licensure Compact.

Read more information about the Nurse Licensure Compact Rules.

Watch a video for nursing students on the Nurse Licensure Compact.

Temporary Permit

In some states before taking the NCLEX, an applicant may apply to receive a temporary permit from their State Board of Nursing (SBON). A temporary permit allows the applicant to practice practical nursing under the direct supervision of a registered nurse until the RN license is granted. A temporary permit is typically valid for a period of three months or until the holder receives failing NCLEX results, whichever is shorter.

Read about the temporary permit available in Wisconsin.

Many students begin applying for their first nursing position before they graduate or take the NCLEX-RN. Read tips for employment in the following box.

| Tips for Employment |

|---|

|

During your job-search process, it is helpful to begin by reviewing Medicare’s quality ratings of health care agencies and providers. The “overall star rating” is based on how well the agency performs on various quality indicators and patient satisfaction surveys.

Review Medicare ratings of hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, and providers at www.medicare.gov/care-compare.

When applying for a job position, a resume and/or portfolio is typically included as part of the application process.

Resume

A resume is a document that highlights one’s background, education, skills, and accomplishments to potential employers. There are many types of resume formats, and some individuals elect to use online services to create a professional resume.

A resume typically includes the following components:

- Personal contact information

- Professional objective statement/Goals

- Education

- Work experience

- Awards and achievements

- Community service

- Languages, hobbies, volunteer experiences (optional)

When creating a resume, it is helpful to highlight skills and experience that separate you from the other candidates applying for the position. It is also helpful to tailor your resume to the skills and experience expressed in the job description.

- Read more details about what to put in a resume and nursing resumes and cover letters.

- View a sample resume.

- View a sample Online Resume Service.

Portfolio

A portfolio is a compilation of materials showcasing examples of previous work demonstrating one’s skills, qualifications, education, training, and experience. They can be submitted in electronic or paper form. See Figure 11.3[42] for an image of a sample electronic portfolio.

Some schools of nursing require portfolios to be completed throughout the program. These portfolios are a representation of work demonstrating the student's accomplishments.

Portfolios typically include the following:

- Personal contact information

- Resume

- Professional goals

- Skilled work with examples (e.g., a nursing care plan, process recording, teaching plan, etc.)

- Accomplishments (e.g., dean’s list)

- Degrees

- Certifications (e.g., CPR)

- Professional memberships (e.g., Student Nurse Association)

- Community service activities

- References (if requested)

- Read more about what to include in a portfolio.

- Visit an online portfolio service.

Interviewing

After applying for a position and submitting your resume and/or portfolio, you may be contacted to set up an interview. When you're interviewing for an RN position, you will be asked about your skills, experience, and your education. Some questions may be basic, such as, “Why did you become a nurse?” Other questions may be more difficult to answer, such as “Explain your strengths and weaknesses as an RN.” See Figure 11.4[43] for a simulated interview.

Interviewing for a new position can cause anxiety because you are required to answer questions and provide examples. A strategy to make the interview process easier and reduce anxiety is to prepare answers for commonly asked questions prior to the interview. Completing this task will help you prepare and increase your confidence. See common interview questions in the following box. It is helpful to tailor your answers to the skills and experience provided in the position description of the job you are seeking.

| Common Questions During an Interview |

|---|

|

Prior to your interview, research the organization's website. Be aware of their mission and vision statements and any “current events” in the news. Interviewers are impressed when an applicant has taken the time to learn about the organization and demonstrates interest.

Interviews may take place face-to-face, virtually on a computer, or over the phone. If you are interviewing face-to-face or virtually, dress for success in professional attire. If interviewing virtually, be sure to decrease distractions at home by turning off your phone and conducting the interview in a quiet space. Establish good eye contact with the interviewer and speak in a confident manner. Remember, this is the time to “sell your nursing self,” so highlight your achievements and what you are proud of accomplishing. See additional tips for interviews in the following box.

| Tips for Interviews |

|---|

|

The interview process is also an opportunity for you to determine if this position and agency is a good fit for you. Remember that it is important to select an agency that has good ratings for providing safe patient care and patient satisfaction. It is not worth taking a position that may place your nursing license at risk. Ask questions of the interviewer to clarify your understanding of the job position and expectations, agency policies, and workplace culture. Suggested interview questions are listed in the following box.

| Questions for Interviewer |

|---|

|

Reality Shock

As a new graduate transitions into the role of being a registered nurse (RN), it is very common to experience something called “reality shock.” Although Kramer’s “Reality Shock” theory is several decades old, it continues to apply to new nurses transitioning to their new role through a process of learning and growing. Kramer’s Reality Shock theory characterizes four phases of transitioning into a new role referred to as the honeymoon, shock, recovery, and resolution phases[44]:

- Honeymoon phase: The first phase occurs when the newly graduated RN is excited to join the nursing profession and it is everything they imagined. During this phase, the new nurse is typically paired up with a preceptor RN to orient them to the new role.

- Shock phase: The second phase is when the new RN is the most vulnerable. They are moved off orientation and independently perform tasks without the guidance of their preceptor. The RN role is often more difficult than the new nurse previously imagined. The new RN realizes their expectations associated with the nursing role may be inconsistent with the actual responsibilities. During this phase, negative feelings regarding their new profession may arise, and the new RN is at greatest risk for leaving the unit or quitting.

- Recovery phase: The third phase is when new RNs begin to have positive feelings towards their profession again. During this phase, the new RN is able to reflect on their experiences and develop a clear understanding of their responsibilities and role expectations. The novice RN typically experiences decreased tension and anxiety and begins to assist other RNs as needed.

- Resolution phase: The fourth and final phase is usually at the end of the first year of the new position. The new RN can visualize how the role contributes to the profession, and work expectations are easily met.

Transitioning Into Practice

Over the years, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) has researched the complex issue of retaining new nursing graduates and found the inability of new nurses to properly transition into practice can have grave consequences. New nurses care for sicker patients in increasingly complex health settings and feel increased stress levels. As a result, new nurses are involved in more patient safety and practice errors than experienced nurses. It has been reported by the NCSBN that within the first year of employment, 25% of novice RNs leave their nursing positions.[45]