5.8 Heart Failure

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Overview

The heart is a hard-working muscle that pumps about 1.5 gallons of blood per minute and over 2,000 gallons of blood per day. Heart failure (HF) occurs when the heart loses its effectiveness in pumping blood and is referred to as decreased cardiac output. When the heart is not pumping effectively, classic symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, edema, or lung congestion can occur.

Chronic HF is a progressive disorder that can be represented on a continuum. The continuum ranges from individuals who are at risk for HF but are asymptomatic, to individuals who have end-stage heart failure and require hospice care. Therapeutic goals and medical treatment are based on where the individual falls on this continuum.[1]

Causes of HF

There are many common causes of HF, including CAD, myocardial infarction (MI), hypertension, valve disorders, and cardiomyopathy.[2] CAD that causes ischemia weakens the cardiac muscle tissue. If an MI occurs, depending on the location of the infarct, muscle tissue dies. If the infarct affects the left ventricle, the heart’s ability to pump is severely affected.

Hypertension is another common cause of HF. Hypertension causes vascular resistance that the heart must overcome to pump blood throughout the body. This increased force causes the ventricles to become thickened and lose their pumping effectiveness.

Heart valve conditions and cardiomyopathy are also common causes of heart failure. Cardiomyopathy has many causes, either acquired or hereditary, that weaken the heart’s muscle tissue. Valve conditions cause narrowing and/or backflow of blood through the valves. Ineffective value function may be identified through the presence of a heart murmur. Both conditions impair the heart’s ability to pump blood.

In addition to these disease processes, various risk factors impacting cardiac health can also lead to the emergence of HF. Smoking, obesity, alcohol, and substance abuse can weaken heart tissue and increase the risk of heart failure. As individuals age, the heart experiences age-related strain on the valves and muscle tissues. Finally, family history of heart disease and ethnicity may can also contribute to increased risk for HF.[3] Non-hispanic Black individuals have the highest death rate per capita.[4]

Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Heart Failure

HF is characterized by symptoms of fatigue, fluid retention, and shortness of breath, depending on which side of the heart is not pumping effectively. Left-sided and right-sided heart failure are two distinct but interrelated conditions that affect the heart’s ability to pump blood effectively. Some clients develop symptoms of both left- and right-sided heart failure. Causes, symptoms, and potential complications of right- and left-sided heart failure differ, but treatment is often similar and often includes diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, vasodilators, and oxygen therapy. See Table 5.8 for a comparison of the signs, symptoms, and potential complications of left- and right-sided heart failure.

Table 5.8. Left- and Right-Sided Heart Failure[5],[6]

| Characteristic | Left-Sided Heart Failure (LHF) | Right-Sided Heart Failure (RHF) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Ventricle Affected | – Left ventricle (LV) | – Right ventricle (RV) |

| Causes | – Hypertension

– Coronary artery disease (CAD) – Myocardial Infarction (MI) – Valvular heart disease |

– Pulmonary hypertension

– Left-sided heart failure – Pulmonary valve disease |

| Signs/Symptoms | – Dyspnea (especially on exertion)

– Orthopnea (shortness of breath when lying flat) – Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) – S3 gallop (ventricular gallop) – Crackles in lungs – Venous stasis (slow blood flow in the veins, usually in the legs) – Decreased ejection fraction on echocardiogram – Decreased pulses, pale/cool extremities |

– Peripheral edema (legs, ankles)

– Ascites (abdominal edema) – Anorexia – Hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) – Jugular venous distension |

| Complications | – Pulmonary edema

– Left atrial enlargement – Cardiogenic shock from decreased cardiac output – Kidney failure |

– Liver failure

– Kidney failure – Venous stasis ulcers |

Functional Classifications of Heart Failure

Because HF is a progressive disease, clients are classified into four categories based on their limitations of physical activity based on the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification. The NYHA Functional Classification categories include the following[7]:

- Class I: No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, palpitation, or shortness of breath.

- Class II: Slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, shortness of breath, or chest pain.

- Class III: Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary activity causes fatigue, palpitation, shortness of breath, or chest pain. Palliative care may be prescribed to enhance the client’s quality of life.

- Class IV: Symptoms of heart failure at rest. Any physical activity causes further discomfort. This stage is also commonly referred to as “end-stage heart failure” that qualifies for hospice care.

As clients undergo treatment, the care team can evaluate the effectiveness of treatment based on the client’s current category of NYHA Functional Classification. It is helpful for nurses to know a client’s baseline NYHA Functional Classification to know what assessment findings to expect and what findings indicate worsening clinical status.

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is the sudden or gradual onset of worsening signs or symptoms of heart failure requiring unplanned office visits, emergency room visits, or hospitalization. It occurs when the heart’s ability to pump a sufficient amount of oxygenated blood to the body’s tissue is no longer sufficient.

Up to 50% of cases of ADHF have no known cause. Potential causes include nonadherence to medications or salt restrictions, side effects of medications, uncontrolled hypertension, arrhythmias, and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Other contributing factors include noncardiac conditions such as kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and anemia.

Signs and symptoms of ADHF include worsening dyspnea, edema, lung sounds, and mental status. The client may also have decreased urine output (oliguria). Nurses must rapidly recognize these unexpected findings in clients with heart failure and promptly report them to the health care provider. Clients with ADHF often require hospitalization and treatment with intravenous diuretics, oxygen therapy, and other medications to maintain adequate cardiac output and perfusion of the kidneys, brain, and heart tissue.

Assessment

When assessing a client with chronic heart failure, it is important to understand the differences between expected findings for that client and signs of an acute exacerbation. Expected findings are based on New York Heart Association Functional Classification, as well as recently documented and communicated status from other members of the health care team. In order to recognize potential clinical deterioration, the nurse caring for a client who has been diagnosed with heart failure must know their baseline status in terms of edema, lung sounds, mental status, and kidney function.

Diagnostic Testing

Common tests used to diagnose heart failure, as well as acute decompensated heart failure, include brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), chest X-ray (CXR), echocardiogram, and electrocardiogram (ECG)[8],[9]:

- Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a laboratory test that measures protein created by the heart and blood vessels. Elevated levels commonly indicate heart failure.

- A chest X-ray examines the size and shape of the heart and identifies fluid accumulation in the lungs.

- An echocardiogram evaluates the structure and function of the heart chambers and valves, as well as blood flow throughout the heart. The ejection fraction measures the amount of blood the left ventricle of the heart pumps out to the body with each heartbeat. A normal heart’s ejection fraction is between 55 and 70 percent. Clients with left-sided heart failure have ejection fraction measurements less than 55 percent. Clients with right-sided heart failure often have a normal ejection fraction.

- An ECG identifies irregular cardiac rhythms that could be contributing to decreased cardiac output associated with HF.

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing priorities for clients with heart failure include addressing respiratory status, fluid retention, fatigue, activity intolerance, and self-management of chronic disease to promote quality of life. Common nursing diagnoses include the following[10]:

- Decreased Cardiac Output

- Decreased Activity Intolerance

- Fatigue

- Impaired Gas Exchange

- Excess Fluid Volume

- Readiness for Enhanced Health Management

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification involves setting short and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements tailored to the client’s specific needs. These outcomes should be measurable and responsive to nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes for common nursing diagnoses related to HF are as follows:

- The client will maintain oxygenation saturation readings above 92%.

- The client will demonstrate a reduction of pitting edema in the lower extremities within one week.

- The client will exhibit improved exercise tolerance by walking on a flat surface for at least ten minutes without chest pain or excessive shortness of breath within two weeks.

- The client will demonstrate the use of relaxation techniques to manage anxiety before discharge, such as deep breathing exercises.

- The client will verbalize an understanding of the importance of a low-sodium diet and will list three specific dietary changes they plan to make at home.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions play an important role in managing the signs and symptoms of heart failure (HF), preventing acute exacerbations, and improving quality of life for individuals with HF. Common medical interventions used to treat HF include medication therapy, lifestyle modifications, cardiac rehabilitation, and surgical interventions.

Medication Therapy

Several classes of medications are used to treat heart failure:

- Diuretics: Reduce fluid retention and edema by increasing urine production. However, diuretics can cause hypokalemia and other electrolyte imbalances, so electrolytes must be monitored carefully. Potassium supplementation may be required.

- ACE Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs): Relax systemic blood vessels, thus reducing systemic resistance and increasing cardiac output.

- Beta-Blockers: Slow the heart rate and allow for increased ventricular filling before each contraction. However, beta-blockers can worsen HF, so they must be monitored carefully.

- Aldosterone Antagonists: Reduce fluid retention.

- Inotropes: Strengthen the heart’s contractions.

Read more information about these classes of medications in “Cardiovascular & Renal System Medications” in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications focus on reducing fluid retention and fatigue, while maximizing heart function:

- Dietary Changes: Reducing sodium intake is crucial for managing fluid retention. Recommended sodium intake is less than two to three grams daily.[11]

- Fluid Restriction: In advanced stages of HF or in acute exacerbations with pulmonary edema, fluid intake is often restricted to less than 1.5 to 2 liters/day.

- Exercise: A structured exercise program can improve heart function and reduce fatigue.

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight reduces strain on the heart.

- Smoking Cessation: If the client smokes, quitting smoking improves overall cardiovascular health.

Cardiac Rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation programs offer supervised exercise, health teaching, and counseling to help clients with HF regain strength, manage their conditions effectively at home, and reduce hospitalizations.

Surgical Interventions

Clients with advanced heart failure may have surgical interventions and/or devices implanted to assist with cardiac output[12],[13]:

- Left Ventricular Assist Device (LVAD): A mechanical pump is implanted to assist the heart’s pumping function. LVADs are commonly used when a client is awaiting heart transplantation.

- Heart Transplantation: For clients with end-stage HF, a heart transplant may be considered, based on the client’s overall health and other chronic conditions.

- Heart Valve Surgery: If a client is experiencing heart failure due to damaged heart valves, repair or replacement of valves be performed to alleviate symptoms.

- Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG): For clients where coronary artery disease is a contributing factor, CABG surgery may be necessary to improve blood flow to the heart muscle.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for heart failure (HF) focus on medication management, health teaching, and psychosocial support to promote quality of life while the client copes with a chronic disease.

Medication Management

Prescribed medications are safely administered, and teaching is provided about medications and their role in improving heart function. In hospitalized clients, therapeutic effects of medications are evaluated, and monitoring is performed for common side effects, such as electrolyte imbalances.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide health teaching to clients about self-management of HF to avoid acute exacerbations and hospitalization. Clients are taught to promptly report the following symptoms to their health care provider[14]:

- Increased shortness of breath or fatigue during their regular daily routine.

- Feelings like their heart rate is racing or throbbing.

- Weight gain of more than two or three pounds in a 24-hour period or more than five pounds in a week, indicating worsening fluid retention. Clients are encouraged to track daily weights in a journal and bring the journal to follow-up appointments.

- Worsening edema in the ankles, feet, and lower legs.

- Increased home blood pressure readings. Clients are taught to track blood pressure readings in a journal and bring the journal to follow-up appointments.

- Confusion or impaired thinking. These symptoms might be first noticed by family members.

- Trouble sleeping due to dyspnea.

- Decreased appetite or swelling in the abdomen making their waistband feel tight.

View or download a PDF Self-Check Plan for Heart Failure Management by the American Heart Association.[15]

Health teaching is also provided about heart-healthy food choices and sodium restrictions to prevent fluid retention. Smoking cessation is encouraged, and information about relaxation techniques to manage anxiety is provided.

Clients with orthopnea are instructed to sleep with their head elevated on pillows or in a recliner to promote lung expansion. Clients experiencing fatigue are encouraged to balance periods of activity with periods of rest to conserve energy.

Psychosocial Support

Nurses address the emotional and psychological impact of HF by providing emotional support and encouraging positive coping strategies. Referrals to mental health professionals are provided for additional support, if needed. Clients are encouraged to participate in support groups and cardiac rehabilitation programs.

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

![]() RN Recap: Heart Failure

RN Recap: Heart Failure

View a brief YouTube video overview of HF[16]:

Media Attributions

- RN Recap Icon

- Heidenreich, P. A., Bozkurt, B., Aguilar, D., Allen, L. A., Byun, J. J., Colvin, M. M., Deswal, A., Drazner, M. H., Dunlay, S. M., Evers, L. R., Fang, J. C., Fedson, S. E., Fonarow, G. C., Hayek, S. S., Hernandez, A. F., Khazanie, P., Kittleson, M. M., Lee, C. S., Link, M. S., et. al. (2022). 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 145(18), e895–e1032. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063 ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Borlaug, B. A. (2022). Heart failure: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Borlaug, B. A. (2022). Heart failure: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Heidenreich, P. A., Bozkurt, B., Aguilar, D., Allen, L. A., Byun, J. J., Colvin, M. M., Deswal, A., Drazner, M. H., Dunlay, S. M., Evers, L. R., Fang, J. C., Fedson, S. E., Fonarow, G. C., Hayek, S. S., Hernandez, A. F., Khazanie, P., Kittleson, M. M., Lee, C. S., Link, M. S., et. al. (2022). 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 145(18), e895–e1032. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063 ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Borlaug, B. A. (2022). Heart failure: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Dunlay, S. M. (2022). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of advanced heart failure. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- American Heart Association. (2023, June 7). Classes and stages of heart failure. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-failure/what-is-heart-failure/classes-of-heart-failure ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Borlaug, B. A. (2022). Heart failure: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Dunlay, S. M. (2022). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of advanced heart failure. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Flynn Makic, M. B., & Martinez-Kratz, M. R. (2023). Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (13th ed.). ↵

- American College of Cardiology. (2023, February 23). Too little sodium can be harmful to heart failure patients. https://www.acc.org/About-ACC/Press-Releases/2023/02/22/20/42/Too-Little-Sodium-Can-be-Harmful-to-Heart-Failure-Patients ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Borlaug, B. A. (2022). Heart failure: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Dunlay, S. M. (2022). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of advanced heart failure. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- American Heart Association. (2023, June 13). Managing heart failure symptoms. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-failure/warning-signs-of-heart-failure/managing-heart-failure-symptoms ↵

- American Heart Association. (2023, June 13). Managing heart failure symptoms. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-failure/warning-signs-of-heart-failure/managing-heart-failure-symptoms ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, April 4). Health Alterations - Chapter 5 Cardiovascular - Heart failure [Video]. YouTube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=unEnPZAlpk0 ↵

In addition to using standard precautions and transmission-based precautions, aseptic technique (also called medical asepsis) is the purposeful reduction of pathogens to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another during a medical procedure. For example, a nurse administering parenteral medication or performing urinary catheterization uses aseptic technique. When performed properly, aseptic technique prevents contamination and transfer of pathogens to the patient from caregiver hands, surfaces, and equipment during routine care or procedures. The word “aseptic” literally means an absence of disease-causing microbes and pathogens. In the clinical setting, aseptic technique refers to the purposeful prevention of microbe contamination from one person or object to another. These potentially infectious, microscopic organisms can be present in the environment, on an instrument, in liquids, on skin surfaces, or within a wound.

There is often misunderstanding between the terms aseptic technique and sterile technique in the health care setting. Both asepsis and sterility are closely related, and the shared concept between the two terms is removal of harmful microorganisms that can cause infection. In the most simplistic terms, asepsis is creating a protective barrier from pathogens, whereas sterile technique is a purposeful attack on microorganisms. Sterile technique (also called surgical asepsis) seeks to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while also maintaining objects as free from microorganisms as possible. It is the standard of care for surgical procedures, invasive wound management, and central line care. Sterile technique requires a combination of meticulous hand washing, creation of a sterile field, using long-lasting antimicrobial cleansing agents such as betadine, donning sterile gloves, and using sterile devices and instruments.

Principles of Aseptic Non-Touch Technique

Aseptic non-touch technique (ANTT) is the most commonly used aseptic technique framework in the health care setting and is considered a global standard. There are two types of ANTT: surgical-ANTT (sterile technique) and standard-ANTT.

Aseptic non-touch technique starts with a few concepts that must be understood before it can be applied. For all invasive procedures, the “ANTT-approach” identifies key parts and key sites throughout the preparation and implementation of the procedure. A key part is any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs, syringe tips, needles, and dressings. A key site is any nonintact skin, potential insertion site, or access site used for medical devices connected to the patients. Examples of key sites include open wounds and insertion sites for intravenous (IV) devices and urinary catheters.

ANTT includes four underlying principles to keep in mind while performing invasive procedures:

- Always wash hands effectively.

- Never contaminate key parts.

- Touch non-key parts with confidence.

- Take appropriate infective precautions.

Preparing and Preventing Infections Using Aseptic Technique

When planning for any procedure, careful thought and preparation of many infection control factors must be considered beforehand. While keeping standard precautions in mind, identify anticipated key sites and key parts to the procedure. Consider the degree to which the environment must be managed to reduce the risk of infection, including the expected degree of contamination and hazardous exposure to the clinician. Finally, review the expected equipment needed to perform the procedure and the level of key part or key site handling. See Table 4.3 for an outline of infection control measures when performing a procedure.

Table 4.3 Infection Control Measures When Performing Procedures

| Infection Control Measure | Key Considerations | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental control |

|

|

| Hand hygiene |

|

|

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) |

|

|

| Aseptic field management | Determine level of aseptic field needed and how it will be managed before the procedure begins:

|

General aseptic field:

IV irrigation Dry dressing changes Critical aseptic field: Urinary catheter placement Central line dressing change Sterile dressing change |

| Non-touch technique |

|

|

| Sequencing |

|

|

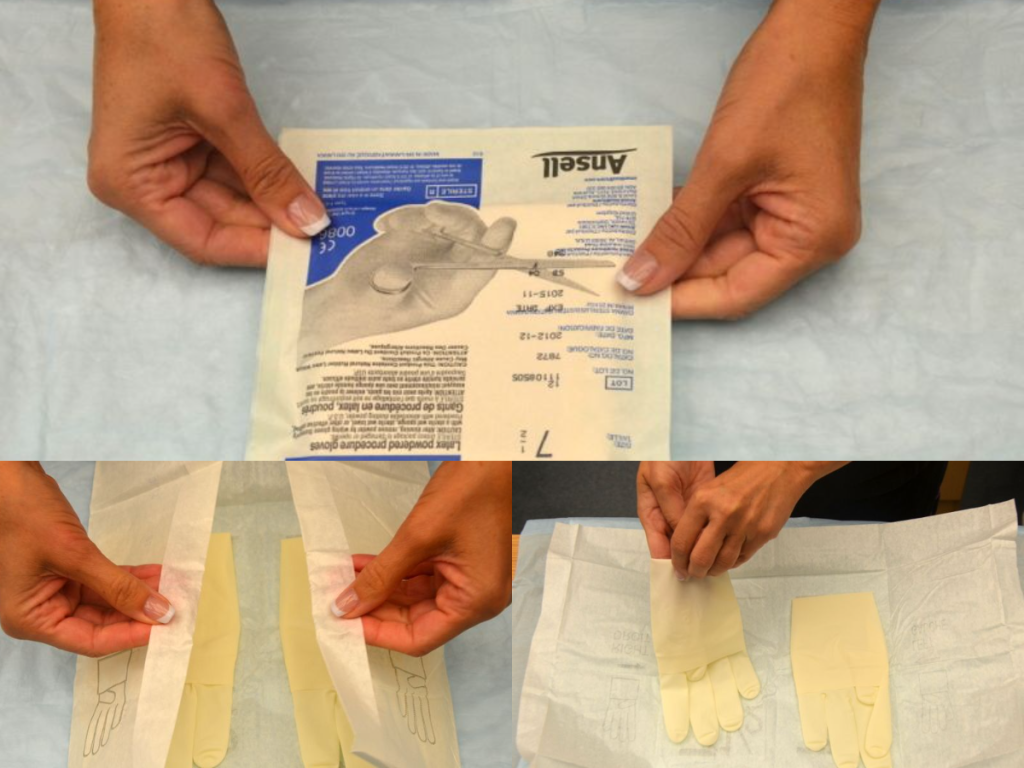

Use of Gloves and Sterile Gloves

There are two different levels of medical-grade gloves available to health care providers: clean (exam) gloves and sterile (surgical) gloves. Generally speaking, clean gloves are used whenever there is a risk of contact with body fluids or contaminated surfaces or objects. Examples include starting an intravenous access device or emptying a urinary catheter collection bag. Alternatively, sterile gloves meet FDA requirements for sterilization and are used for invasive procedures or when contact with a sterile site, tissue, or body cavity is anticipated. Sterile gloves are used in these instances to prevent transient flora and reduce resident flora contamination during a procedure, thus preventing the introduction of pathogens. For example, sterile gloves are required when performing central line dressing changes, insertion of urinary catheters, and during invasive surgical procedures. See Figure 4.15[1] for images of a nurse opening and removing sterile gloves from packaging.

See the “Checklist for Applying and Removing Sterile Gloves” for details on how to apply sterile gloves.

Applying Sterile Gloves on YouTube[2]

Use this checklist to perform a "General Survey." Checklists for hand washing, using hand sanitizer, and obtaining vital signs are included in Appendix A.

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Knock, enter the room, greet the patient, and provide for privacy.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Ask the patient their legal name and date of birth to establish two unique identifiers. Verify the information provided in their chart or wristband, if present. Use one of the following for the second verification:

- Scan wristband

- Compare name/DOB to MAR

- Ask staff to verify patient (in settings where wristbands are not worn)

- Compare picture on MAR to patient

- Address patient needs (pain, toileting, glasses/hearing aids) prior to starting assessment. Note if the patient has signs of distress such as difficulty breathing or chest pain. If signs are present, defer general survey and obtain emergency assistance per agency policy.

- Explain the procedure to the patient; ask if they have any questions. Obtain an interpreter as needed if English is not the patient’s primary language.

- Pause and explain to the instructor what you would purposefully observe and assess during a general survey assessment.

- Upon completion of the survey, thank the patient and ask if anything is needed.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene and clean stethoscope.

- Follow agency policy for reporting findings outside of normal range.

- Document the assessment.

A sterile field is established whenever a patient’s skin is intentionally punctured or incised, during procedures involving entry into a body cavity, or when contact with nonintact skin is possible (e.g., surgery or trauma). Surgical asepsis requires adherence to strict principles and intentional actions to prevent contamination and to maintain the sterility of specific parts of a sterile field during invasive procedures. Creating and maintaining a sterile field is foundational to aseptic technique and encompasses practice standards that are performed immediately prior to and during a procedure to reduce the risk of infection, including the following:

- Handwashing

- Using sterile barriers, including drapes and appropriate personal protective equipment

- Preparing the patient using an approved antimicrobial product

- Maintaining a sterile field

- Using aseptically safe techniques

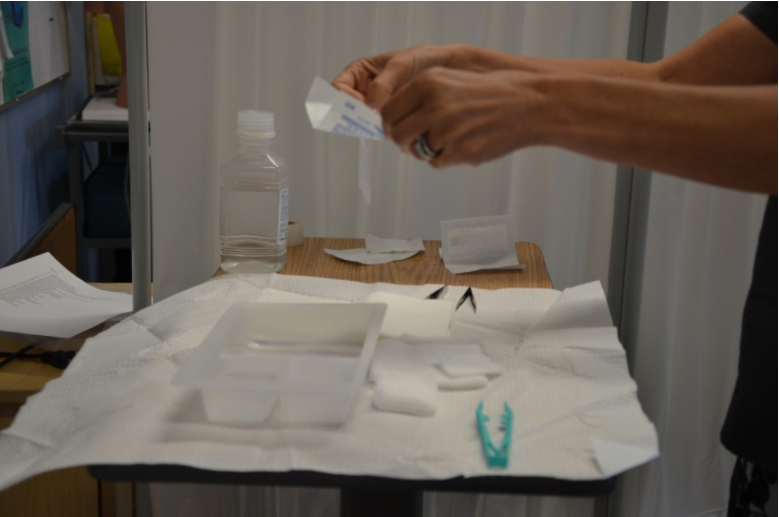

There are basic principles of asepsis that are critical to understand and follow when creating and maintaining a sterile field. The most basic principle is to allow only sterile supplies within the sterile field once it is established. This means that prior to using any supplies, exterior packaging must be checked for any signs of damage, such as previous exposure to moisture, holes, or tears. Packages should not be used if they are expired or if sterilization indicators are not the appropriate color. Sterile contents inside packages are dispensed onto the sterile field using the methods outlined below. See Figure 4.16[3] for an image of a nurse dispensing sterile supplies from packaging onto an established sterile field.

When establishing and maintaining a sterile field, there are other important principles to strictly follow:

- Disinfect any work surfaces and allow to them thoroughly dry before placing any sterile supplies on the surface.

- Be aware of areas of sterile fields that are considered contaminated:

- Any part of the field within 1 inch from the edge.

- Any part of the field that extends below the planar surface (i.e., a drape hanging down below the tray tabletop).

- Any part of the field below waist level or above shoulder level.

- Any supplies or field that you have not directly monitored (i.e., turned away from the sterile field or walked out of the room).

- Within 1 inch of any visible holes, tears, or moisture wicked from an unsterile area.

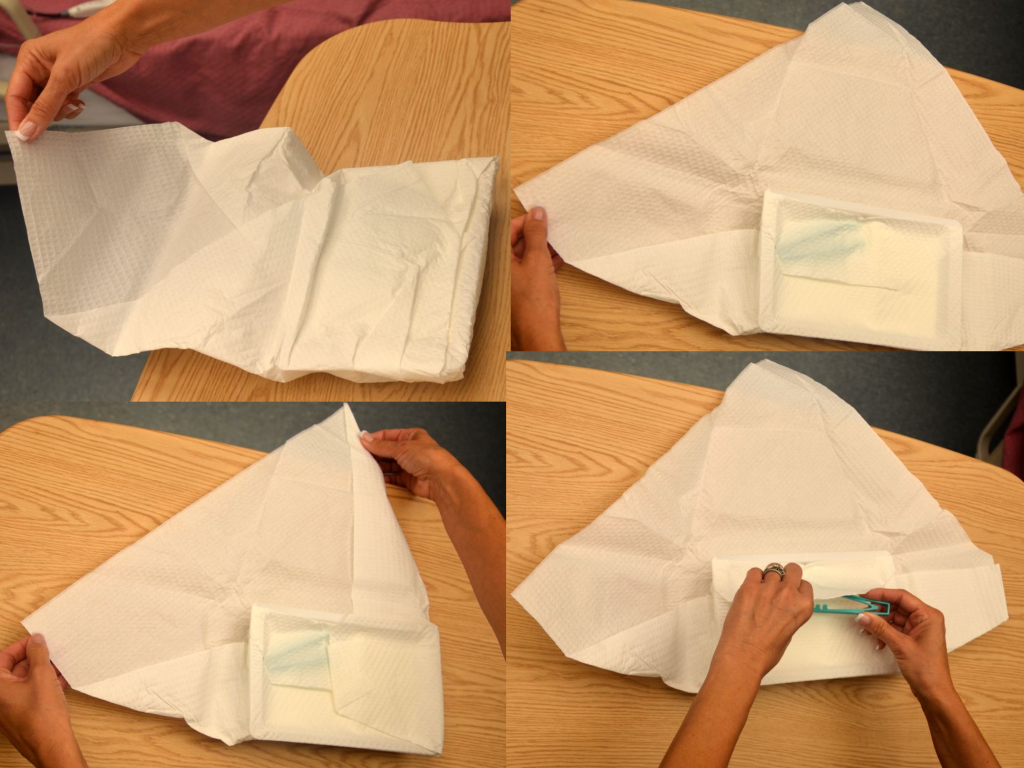

- When handling sterile kits and trays:

- Sterile kits and trays generally have an outer protective wrapper and four inner flaps that must be opened aseptically.

- Open sterile kits away from your body first, touching only the very edge of the opening flap.

- Using the same technique, open each of the side flaps one at a time using only one hand, being careful not to allow your body or arms to be directly above the opened drape. Take care not to allow already-opened corners to flip back into the sterile area again.

- Open the final flap toward you, being careful to not allow any part of your body to be directly over the field. See Figure 4.17[4] for images of opening the flaps of a sterile kit.

- If you must remove parts of the sterile kit (i.e., sterile gloves), reach into the sterile field with the elbow raised, using only the tips of the fingers before extracting. Pay close attention to where your body and clothing are in relationship to the sterile field to avoid inadvertent contamination.

- When dispensing sterile supplies onto a sterile field:

- Before dispensing sterile supplies to a sterile field, do not allow sterile items to touch any part of the outer packaging once it is opened, including the former package seal.

- Heavy or irregular items should be opened and held, allowing a second person with sterile gloves to transfer them to the sterile field.

- Wrapped sterile items should be opened similarly to a sterile kit. Tuck each flap securely within your palm, and then open the flap away from your body first. Then open each side flap; secure the flap in the palm one at a time and open. Finally, open the flap (closest to you) toward you, while also protecting the other opened flaps from springing back onto the wrapped item.

- Peel pouches (i.e., gloves, gauze, syringes, etc.) can be opened by firmly grasping each side of the sealed edge with the thumb side of each hand parallel to the seal and pulling carefully apart.

- Drop items from six inches away from the sterile field.

- Sterile solutions should be poured into a sterile bowl or tray from the side of the sterile field and not directly over it. Use only sealed, sterile, unexpired solutions when pouring onto a sterile field. Solution should be held six inches away from the field as it is being poured. Avoid splashing solutions because this allows wicking and transfer of microbes. After pouring of solution stops, it should not be restarted because the edge is considered contaminated. See Figure 4.18[5] of an image of a nurse pouring sterile solution into a receptacle in a sterile field before the procedure begins.

- Don sterile gloves away from the sterile field to avoid contaminating the sterile field.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Maria is working on a medical surgical unit and receives a direct admission from the internal medicine clinic. She arrives at the patient’s room to complete the initial admission assessment. All of the following conditions are found. Of these conditions, which of the following should be reported immediately to the health care provider.

- Patient ambulates with assistance of wheeled walker.

- Patient’s BMI is outside of the normal range.

- Patient appears unkempt and has strong body odor.

- Patient is experiencing increased difficulty breathing.

"Vital Signs Case Study” by Susan Jepsen for Lansing Community College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 1.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 2.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 3.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 4.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 5.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 6.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 7.