Understanding the Legal System

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Understanding the Legal System

There are several types of laws and regulations that affect nursing practice. Laws are rules and regulations created by a society and enforced by courts and professional licensure boards. Nurses are responsible for being aware of public and private laws that affect client care, as well as legal actions that can result when these laws are broken.

Laws are generally classified as public or private law. Public law regulates relations of individuals with the government or institutions, whereas private law governs the relationships between private parties.

Public Law

There are several types of public law, including constitutional, statutory, administrative, and criminal law.

- Constitutional law refers to the rights, privileges, and responsibilities established by the U.S. Constitution.[1] The right to privacy is an example of a patient right based on constitutional law.

- Statutory law refers to written laws enacted by the federal or state legislature. For example, the Nurse Practice Act in each state is an example of statutory law enacted by that state’s legislature. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is an example of a federal statutory law. HIPAA required the creation of national standards to protect sensitive client health information from being disclosed without the client’s consent or knowledge.

- Administrative law is law created by government agencies that have been granted the authority to establish rules and regulations to protect the public.[2] An example of federal administrative law is the regulations set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). OSHA was established by Congress to ensure safe and healthy working conditions for employees by setting and enforcing federal standards. An example of administrative law at the state level is the State Board of Nursing (SBON). The SBON is a group of individuals in each state, established by that state’s legislature, to develop, review, and enforce the Nurse Practice Act. The SBON also issues nursing licenses to qualified candidates, investigates reports of nursing misconduct, and implements consequences for nurses who have violated the Nurse Practice Act.

- Criminal law is a system of laws concerned with punishment of individuals who commit crimes.[3] A crime is a behavior defined by Congress or state legislature as deserving of punishment. Crimes are classified as felonies, misdemeanors, and infractions. Conviction for a crime requires evidence to show the defendant is guilty beyond a shadow of doubt. This means the prosecution must convince a jury there is no reasonable explanation other than guilty that can come from the evidence presented at trial. In the United States, an individual is considered innocent until proven guilty. See Figure 5.1[4] for an illustration of a trial with a jury.

Serious crimes that can result in imprisonment for longer than one year are called felonies. Felony convictions can also result in the loss of voting rights, the ability to own or use guns, and the loss of one’s nursing license. An example of a felony committed by some nurses is drug diversion of controlled substances.

Misdemeanors are less serious crimes resulting in penalties of fines and/or imprisonment for less than one year. For example, in Wisconsin, misdemeanors are categorized as Class A, B, or C based on their sentencing. Class A misdemeanors are sentenced to a fine not to exceed $10,000 or imprisonment not to exceed nine months, or both. Class B misdemeanors are sentenced to a fine not to exceed $1,000 or imprisonment not to exceed 90 days, or both. Class C misdemeanors are sentenced to a fine not to exceed $500 or imprisonment not to exceed 30 days, or both.[5] Examples of misdemeanors include battery, possession of controlled substances, petty theft, disorderly conduct, and driving under the influence (DUI) charges. Although considered less serious crimes, misdemeanors can impact an individual’s ability to obtain or maintain a nursing license.

Nurses who are found guilty of misdemeanors or felonies, regardless if the violation is related to the practice of nursing, must typically report these violations to their state’s Board of Nursing.

Infractions are minor offenses, such as speeding tickets, that result in fines but not jail time. Infractions do not generally impact nursing licensure unless there is a significant quantity of them over a short period of time.

Sample Case

An LPN working for a hospice agency was accused of stealing a patient’s pain medications and substituting them with anti-seizure medication. The family asserted the actions of the LPN prolonged the patient’s suffering. The LPN served time in prison for diverting the patient’s medications.[6]

Private Law

Private law, also referred to as civil law, focuses on the rights, responsibilities, and legal relationships between private citizens. Civil law typically involves compensation to the injured party. Unlike criminal law that requires a jury to determine a defendant is guilty beyond reasonable doubt, civil law only requires a certainty of guilt of greater than 50 percent.[7] See Figure 5.2[8] illustrating balancing the evidence to determine the certainty of guilt. Any nurse can be impacted by civil law based on actions occurring in daily nursing practice.

Civil law includes contract law and tort law. Contracts are binding written, verbal, or implied agreements. A tort is an act of commission or omission that gives rise to injury or harm to another and amounts to a civil wrong for which courts impose liability. In the context of torts, “injury” describes the invasion of any legal right, whereas “harm” describes a loss or detriment that an individual suffers.[9]

Two categories of torts affect nursing practice: intentional torts, such as intentionally hitting a person, and unintentional torts (also referred to as negligent torts), such as making an error by failing to follow agency policy.

Intentional Torts

Intentional torts are wrongs that the defendant knew (or should have known) would be caused by their actions. Examples of intentional torts include assault, battery, false imprisonment, slander, libel, and breach of privacy or client confidentiality.

Unintentional Torts

Unintentional torts occur when the defendant’s actions or inactions were unreasonably unsafe. Unintentional torts can result from acts of commission (i.e., doing something a reasonable nurse would not have done) or omission (i.e., failing to do something a reasonable nurse would do).[10]

Negligence and malpractice are examples of unintentional torts. Tort law exists to compensate clients injured by negligent practice, provide corrective judgement, and deter negligence with visible consequences of action or inaction.[11],[12] Examples of common torts affecting nursing practice are discussed in further detail in the following subsections. See Table 5.2 for a comparison of public and private law.

Table 5.2 Comparison of Public and Private Law

| Type of Law | Subtypes of Law and Examples |

|---|---|

| Public Law |

|

| Private Law (Civil Law) |

|

Examples of Intentional and Unintentional Torts

Assault and Battery

Assault and battery are intentional torts. Assault is defined as intentionally putting another person in reasonable apprehension of an imminent harmful or offensive contact.[13] Battery is defined as intentional causation of harmful or offensive contact with another person without that person’s consent.[14] Physical harm does not need to occur to be charged with assault or battery. Battery convictions are often misdemeanors but can be felonies if serious bodily harm occurs. To avoid the risk of being charged with assault or battery, nurses must obtain consent from clients to provide hands-on care.

False Imprisonment

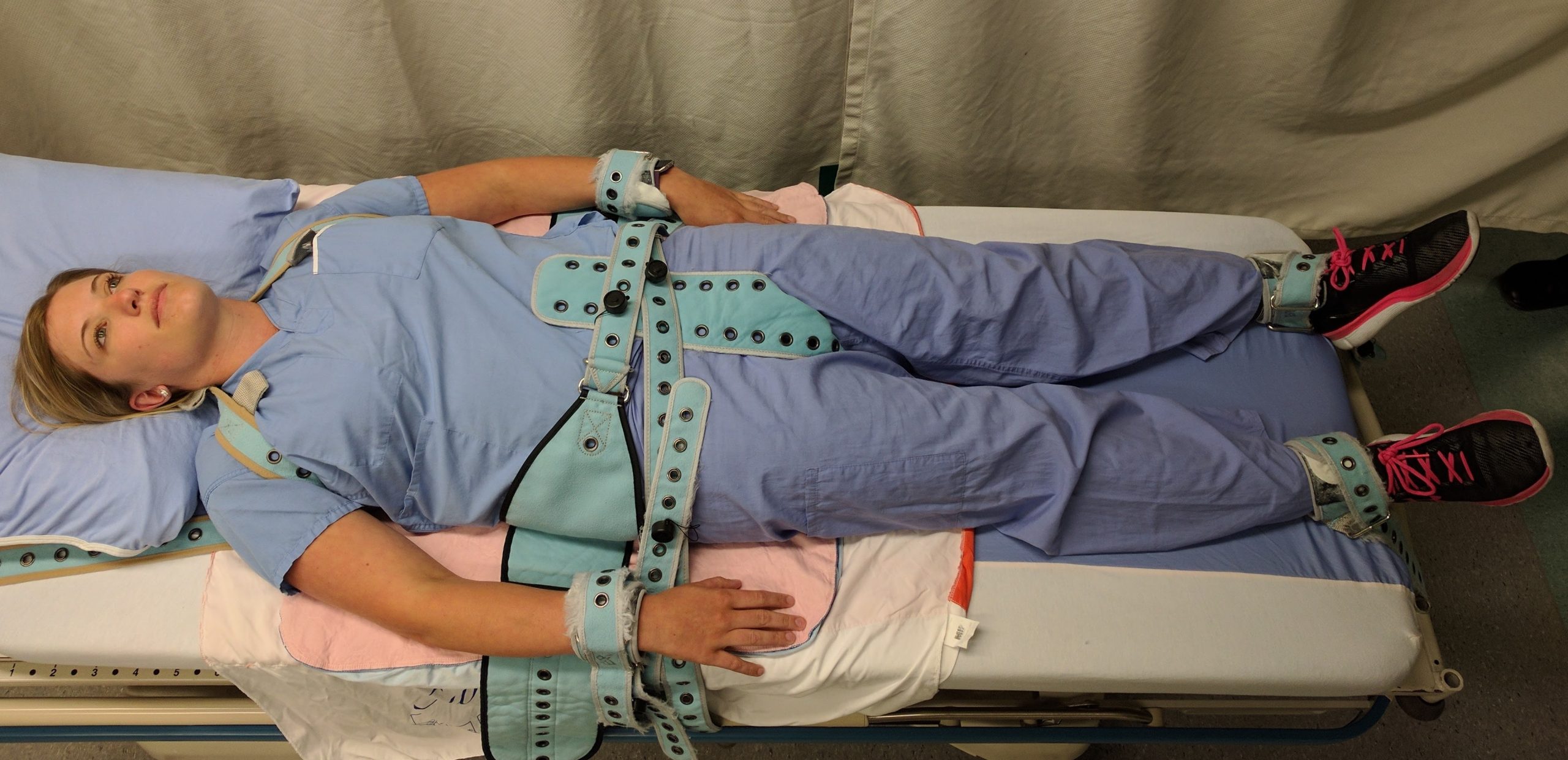

False imprisonment is an intentional tort. False imprisonment is defined as an act of restraining another person and causing that person to be confined in a bounded area.[15] In nursing practice, restraints can be physical, chemical, or verbal. Nurses must strictly follow agency policies related to the use of restraints. Physical restraints typically require a provider order and documentation according to strict guidelines within specific time frames. See Figure 5.3[16] for an image of a simulated client in full physical medical restraints.

Chemical restraints include administering medications such as benzodiazepines and require clear documentation supporting their use. Verbal threats to keep an individual in an inpatient environment can also qualify as false imprisonment and should be avoided.

Breach of Privacy and Confidentiality

Breaching privacy and confidentiality are intentional torts. Confidentiality is the right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information, referred to as protected health information (PHI), kept private. Protected Health Information (PHI) is defined as individually identifiable health information, including demographic data, that relates to the individual’s past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition[17]; the provision of health care to the individual; and the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual.

This right is protected by federal regulations called the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA was enacted in 1996 and was prompted by the need to ensure privacy and protection of personal health records and data in an environment of electronic medical records and third-party insurance payers. There are two main sections of HIPAA law: the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule. The Privacy Rule addresses the use and disclosure of individuals’ health information. The Security Rule sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information. HIPAA regulations extend beyond medical records and apply to client information shared with others. Therefore, all types of client information should be shared only with health care team members who are actively providing care to them.[18],[19]

HIPAA violations may result in fines from $100 for an individual violation to $1.5 million for organizational violations. Criminal penalties, including jail time of up to ten years, may be imposed for violations involving the use of PHI for personal gain or malicious intent. Nursing students are also required to adhere to HIPAA guidelines from the moment they enter the clinical setting or risk being disciplined or expelled by their nursing program.

Sample Case

An RN accessed a patient’s medical records, as well as the records of the newborn son, although she was not assigned to their care because she believed the newborn was her biological grandchild. Although the chart was accessed for less than five seconds, it was unauthorized. The nurse was publicly reprimanded by the state’s Board of Nursing, and her multistate licensure privileges were revoked. Expenses to defend the nurse exceeded $2,800.[20]

Read more about the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Slander and Libel

Slander and libel are intentional torts. Defamation of character occurs when an individual makes negative, malicious, and false remarks about another person to damage their reputation. Slander is spoken defamation and libel is written defamation. Nurses must take care to communicate and document facts regarding patient care without defamation in their oral and written communications with clients and coworkers.

Fraud

Fraud is an intentional tort occurring when an individual is deceived for personal gain. An example of fraud is financial exploitation perpetrated by individuals who are in positions of trust.[21],[22] A nurse may be charged with fraud for documenting interventions not performed or altering documentation to cover up an error. Fraud can result in civil and criminal charges and also suspension or revocation of a nurse’s license.

Negligence and Malpractice

Negligence and malpractice are types of unintentional torts. Negligence is the failure to exercise the ordinary care a reasonable person would use in similar circumstances. Wisconsin civil jury instruction states, “A person is not using ordinary care and is negligent, if the person, without intending to do harm, does something (or fails to do something) that a reasonable person would recognize as creating an unreasonable risk of injury or damage to a person or property.”[23] Malpractice is a specific term used for negligence committed by a professional with a license. See Figure 5.4[24] for an illustration related to malpractice.

Elements of Nursing Malpractice

Nurses and nursing students don’t often get sued for malpractice, but when they do, it is important to understand the elements required to prove malpractice. All the following elements must be established in a court of law to prove malpractice[25]:

- Duty: A nurse-client relationship exists.

- Breach: The standard of care was not met and harm was a foreseeable consequence of the action or inaction.

- Cause: Injury was caused by the nurse’s breach.

- Harm: Injury resulted in damages.

Parties bringing a lawsuit must be able to demonstrate their interests were harmed, providing a reason to stand before the court. The person bringing the lawsuit is called the plaintiff. The parties named in the lawsuit are called defendants. Most malpractice lawsuits name physicians or hospitals, although nurses can be individually named. Employers can be held liable for the actions of their employees.[26]

Malpractice lawsuits are concerned with the legal obligations nurses have to their patients to adhere to current standards of practice. These legal obligations are referred to as the duty of reasonable care. Nurses are required to adhere to standards of practice when providing care to patients they have been assigned. This includes following organizational policies and procedures, maintaining clinical competency, and confining their activities to the authorized scope of practice as defined by their state’s Nurse Practice Act. Nurses also have a legal duty to be physically, mentally, and morally fit for practice. When nurses do not meet these professional obligations, they are said to have breached their duties to patients.[27]

Duty

In the work environment, a duty is created when the nurse accepts responsibility for a patient and establishes a nurse-patient relationship. This generally occurs during inpatient care upon acceptance of a handoff report from another nurse. Outside the work environment, a nurse-patient relationship is created when the nurse volunteers services. Some states have statutes requiring notification of authorities (also referred to as mandatory reporting) or summoning assistance.[28]

Good Samaritan Law

The Good Samaritan Law provides protections against negligence claims to individuals who render aid to people experiencing medical emergencies outside of clinical environments. All 50 states in the United States have a version of a Good Samaritan Law. See Figure 5.5[29] for historical artwork depicting a Good Samaritan. Differences exist in state laws regarding protection of bystanders who provide aid. For example, in Wisconsin, the law states, “Any person who renders emergency care at the scene of any emergency or accident in good faith is immune from civil liability for the person’s acts or omissions in rendering such emergency care.”[30] There are a few states that require some emergency bystander action, so nurses should review the law in states they are visiting. It is also important to keep in mind that although anyone can file a lawsuit against someone who provides bystander aid, the Good Samaritan laws typically negate any penalty to the person rendering aid.

Although the majority of Good Samaritan laws are at the state level, the federal Aviation Medical Assistance Act (AMAA) provides liability protection for aid given on aircraft. The most common in-flight medical emergencies involve syncope, as well as gastrointestinal, respiratory, and cardiac events.[31] Note that consent for care by an unconscious person is implied, but consent must be obtained from alert individuals.

Mandatory Reporting

Nurses are legally responsible for reporting certain crimes. Mandatory reporting requirements vary based on the state of practice, but there are some commonalities. For example, nurses are mandated to report suspected abuse of children, the elderly, and the disabled (if they have been deemed as incompetent by a court of law or as incapacitated by qualified health care providers).

Nurses are also mandated to report gunshot wounds, dog bites, some communicable diseases, and unsafe or illegal practices of other health care team members. Reporting responsibility often begins at the organizational level. The nurse may also need to identify the appropriate local, state, or federal authorities to submit the report and pursue it to its resolution.

Sample Statute Regarding Duty to Assist

A Minnesota statute states that a person at the scene of an emergency who knows that another person is exposed to or has suffered grave physical harm shall, to the extent that the person can do so without danger or peril to self or others, give reasonable assistance to the exposed person. Reasonable assistance may include obtaining or attempting to obtain aid from law enforcement or medical personnel. A person who violates this is guilty of a petty misdemeanor.[32]

Implications for Nurses

Duty can be established in many ways. Nurses have a duty of reasonable care for a patient they have been assigned. They may also have a duty in other circumstances. Therefore, nurses should understand the following[33]:

- Recognize that a nurse-patient relationship is established upon acceptance of responsibility for a patient, whether after a handoff report in the workplace or during volunteered services.

- Assume that on-call or supervisory responsibilities create a duty to patients, even in the absence of an expressed nurse-patient relationship.

- Know if there is a duty to rescue statute in their state, and if so, what it demands.

Breach of Duty

The second element of malpractice is breach of duty. After a plaintiff has established the first element in a malpractice suit, that the nurse owed a duty to the plaintiff, the plaintiff must then demonstrate that the nurse breached that duty by failing to comply with the duty of reasonable care.[34]

To demonstrate that a nurse breached their duty to a patient, the plaintiff must prove the nurse departed from acceptable standards of practice. The plaintiff must establish how a reasonably prudent nurse in the same or similar circumstances would act and then show that the defendant nurse departed from that standard of practice. The plaintiff must claim the nurse did something a reasonably prudent nurse would not have done (an act of commission) or failed to do something a reasonable nurse would have done (an act of omission).[35]

Experts are needed during court hearings to explain things outside the knowledge of non-nurse jurors. In reaching their opinions, experts review many materials, including the state’s Nurse Practice Act and organizational policies, to determine whether the nurse adhered to them. To qualify as a nurse expert, the person testifying must have relevant experience, education, skill, and knowledge. They typically have advanced degrees, are published in nursing literature, have spoken at professional conferences, and belong to professional organizations. Medical malpractice trials take place primarily in state courts, so experts are deemed qualified based on state requirements.

Sample Case Regarding Breach of Duty[36]

Mary Jones was an 87-year-old woman who presented to the hospital with dizziness, nausea, intermittent slurred speech, an unsteady gait, and a history of four falls at home that day. Significant medical history included heart disease and multiple medications. The admitting nurse assessed her as being at risk for falls and placed her on universal fall precautions. The fall precautions included keeping the bed in the lowest position, instructing her on the use of the call light and ensuring the call light was within her reach, providing a bedside commode, and placing her in a room close to the nurses’ station where she could be observed. However, the nurse did not use a formal scoring system for fall risk assessment that was set forth in a nursing procedures textbook. Additionally, bed alarms had not been working at this agency for a year.

Five days later, a nurse responded to a sound coming from Mrs. Jones’s room and found her lying on the bathroom floor. She was conscious and able to move all extremities but complained of left knee and elbow pain. The physician was notified, and Mrs. Jones was sent for X-rays and a CT scan. When Mrs. Jones returned to her room, the nurse observed she was diaphoretic and deteriorating. The nurse took Mrs. Jones to the emergency department, where she lost consciousness. She was evaluated by a neurosurgeon, intubated, and airlifted to a different hospital for a higher level of care. She never regained consciousness and died the next day from intracranial bleeding that was aggravated by anticoagulant therapy.

Mrs. Jones’s estate brought a lawsuit alleging nursing malpractice. The estate’s nursing expert stated the universal fall precautions had been inadequate for a high-risk patient and additional measures should have been instituted. The expert testified that not only had the admitting nurse not adhered to the formal scoring system for fall risk assessment in the nursing procedures textbook, but also the standard of care required nurses to use bed alarms, institute 15-minute rounds, or place a sitter in the room.

A defense expert used The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals to define the standard of care and testified it was her opinion the nurse had met that standard. The organizational policy did not require bed alarms as part of its fall prevention plan. Although the nurses did not use the formal scoring system in a textbook to assess the patient’s risk, they clearly identified her as being at risk for falling; assessed her frequently; maintained her bed in the lowest position; kept the wheels of her bed locked and her side rails up; and kept the call light within her reach. They instructed her on the use of the call light and placed her in a room where she could be readily observed.

The court entered the judgment for the defendant hospital, noting that “under the circumstances, it is a close call on whether the hospital, by not having functioning bed alarms and staff not checking on Mary more frequently, breached the standard of care.”[37] In this case, the plaintiff’s expert had not demonstrated the standard of care was breached.

Implications for Nurses

Nurses defending themselves against allegations of professional malpractice must demonstrate their actions conformed with accepted standards of practice. They must convince a jury they acted as a reasonably prudent nurse would have in the same or similar circumstances. Nurses should always follow these practices[38]:

- Adhere to organizational policies and procedures. Work-arounds can create liability. The standard of practice is to adhere to agency policy. Failing to do so creates an assumption of departure from standards.

- Document in a manner that permits accurate reconstruction of patient assessments and the sequence of events, especially when notifying providers regarding clinical concerns.

- Maintain competence through continuing education, participation in professional conferences, membership in professional organizations, and subscriptions to professional journals.

- When using an interpreter, ensure that properly trained interpreters are used and document the name of the interpreter. The use of family, friends, or other untrained interpreters is unsafe practice and is not consistent with acceptable standards of practice.

- Maintain professional boundaries. Personal relationships with patients or their families can be red flags for juries and can be viewed as evidence of departure from professional standards.

Cause

The third element of malpractice is cause. After the plaintiff has established the nurse owed a duty to a patient and then breached that duty, they must then demonstrate that damages or harm were caused by that breach. Plaintiffs cannot prevail by only demonstrating the nurse departed from acceptable standards of practice but must also prove that such departures were the cause of any injuries.[39] Additionally, nurses are held accountable for foreseeability, meaning a nurse of ordinary skill, care, and diligence could anticipate the risk of harm of departing from standards of practice in similar circumstances.[40]

Plaintiffs must be able to link the defendant’s acts or omissions to the harm for which they are seeking compensation. This requires expert testimony from a physician because it requires a medical diagnosis. Unlike in criminal cases, in which the standard of proof is that elements of prosecution must be proven “beyond reasonable doubt,” the elements of a malpractice lawsuit must be proven by a “preponderance of evidence.” Expert testimony is required to demonstrate “medical certainty” that the nurse’s breach was the cause of an actual injury.

Sample Cases Regarding Causation

Case 1

Janusz Osiecki was admitted to a subacute nursing facility to recover from Guillain-Barre syndrome. The standard of nursing care for this client included respiratory assessments and tracheostomy care. One morning, three weeks into his stay, he was found unresponsive, without pulse or respirations. His wife brought a wrongful death lawsuit, and expert witnesses testified the nurses breached the standard of care in not performing respiratory and tracheostomy assessments every two hours. Their rationale was that the purpose of the assessments was to detect and report pulmonary congestion, and if the nurses had done so in a timely manner, Mr. Osiecki could have received medical care that would have saved his life. A jury awarded the widow $577,005 for wrongful death and $250,000 for harm to family relationships.[41]

Case 2

A psychiatric patient identified as “C” was locked in a seclusion room after presenting to a hospital with psychosis and continuing bizarre behavior, hallucinations, irrationality, lack of contact with reality, and agitation. She was in the seclusion room undergoing treatment for over a week when she suffered a grand mal seizure. A psychiatrist ordered antipsychotic medication. The medication order was not noted by nursing staff until the next day, at which point it was discovered the medication was unavailable at the pharmacy. The psychiatrist was not made aware the medication was unavailable, and the patient went without the prescribed medication for three days. The nurses also did not notify the psychiatrist during those three days that C was becoming increasingly more agitated and hallucinating. On the fourth day, C attempted to leave the unit and told staff she was hearing voices instructing her to harm herself. She was returned to seclusion and remained there without being assessed or treated. Four hours later, she was found unconscious with her head wedged between the side rail and the mattress. She suffered brain damage that left her in a permanent semicomatose state.

C’s estate brought a lawsuit alleging it was negligent to leave C in a steel bed in a seclusion room without constant observation. The jury awarded $3.6 million. The hospital appealed, but the appellate court upheld the jury verdict and explained that particular injuries do not need to be foreseen, only the general harm that can occur. The court stated, “It is not extraordinary that a psychotic patient who is delusional…might wedge herself between a mattress and side rail in an attempt to hurt herself.”[42]

Implications for Nurses

Nurses can reduce their liability by adhering to professional standards and documenting their observations and communications. Nurses should always follow these standards[43]:

- Follow the chain of command when there are concerns about unclear or potentially unsafe orders. Pursue concerns to resolution, documenting precisely who is notified and at what times.

- Document observations to justify clinical decisions. Variance charting (i.e., only charting things that vary from the norm) does not provide sufficient evidence of compliance with the standards of care.

- Adhere to organizational policies and procedures with an understanding that a failure to do so creates foreseeable harm to patients.

Harm

The fourth element of malpractice is harm. In a civil lawsuit, after a plaintiff has established the nurse owed a duty to the patient and breached that duty and injury was caused by the nurse’s breach, they must prove the injury resulted in damages. They request repayment for what they have lost.[44]

There are several types of injuries for which patients or their representatives seek compensation. Injuries can be physical, emotional, financial, professional, marital, or any combination of these. Physical injuries include loss of function, disfigurement, physical or mental impairment, exacerbation of prior medical problems, the need for additional medical care, and death. Economic injuries can include lost wages, additional medical expenses, rehabilitation, durable medical expenses, the need for architectural changes to one’s home, the loss of earning capacity, the need to hire people to do things the plaintiff can no longer do, and the loss of financial support. Emotional injuries can include psychological damage, emotional distress, or other forms of mental suffering.[45]

Determining the specific amount a plaintiff needs can require expert witness testimony from a person known as a life care planner who is trained in analyzing and evaluating medical costs, as well as the subjective determination of a jury. Damages fall into several categories, including compensatory (economic) damages, noneconomic damages, and punitive damages.[46] See Figure 5.6[47] for an illustration of damages.

Economic damages (also referred to as actual damages) can be quantified. They are intended to restore the plaintiff to the position they were in before being injured. Compensatory damages are objectively calculated to provide the plaintiff with the amount of money necessary to replace what was lost.[48]

Noneconomic damages are subjective and can include things such as emotional distress, pain and suffering, loss of enjoyment of life, reputation damage, loss of companionship, or loss of parental guidance. They are more difficult to quantify than economic damages.[49]

Punitive damages are awards not related to the actual injury but are intended to punish the defendant(s) and deter others from engaging in similar conduct. In professional malpractice cases, punitive damages are difficult for plaintiffs to obtain because they must be related to outrageous conduct, such as gross negligence, recklessness, willful actions, or fraud.[50]

Sample Case Related to Damages[51]

Betty Shiflett fell out of bed in the recovery room after undergoing knee surgery. Three days later, she reported a clicking sound and pain in her knee to one of the nurses. Although the nurse documented these symptoms, she did not convey the information to the physician. A physical therapist reported these symptoms to the physician a week later. The physician then identified a previously undiagnosed nondisplaced left tibial fracture that was now avulsed. Two additional surgeries were unsuccessful, and Betty remained disabled, confined to a wheelchair, and in chronic pain.

Betty and her husband filed a lawsuit alleging negligence for the fall and the nurse’s failure to report the symptoms to the physician. They also asserted a claim for a loss of consortium, meaning the spouse or family had also been harmed. The harm suffered is a loss of companionship, conjugal relations, support and services, or marital quality. The jury awarded total damages of $2,391,620 with the following breakdown:

- $791,620 for future medical expenses

- $800,000 for past noneconomic damages

- $500,000 for future noneconomic damages

- $300,000 for loss of consortium with spouse

Implications for Nurses

Nurses can reduce their liability exposure by following these principles[52]:

- Practicing according to current standards of practice.

- Maintaining professional liability insurance to provide coverage for events and licensure defense.

- Avoiding work-arounds or deviations from organizational policies and procedures.

- Maintaining clinical competency, including awareness of standard-of-practice changes.

- Engaging the chain of command with patient concerns and pursuing concerns to resolution.

- Documenting in a manner that permits accurate reconstruction of patient assessments, notification of others, and the sequence of events.

Media Attributions

- Courtroom Trial with Judge, Jury – Vector Image

- 8958807534_d2da00751a_k

- malpractice

- damages

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.) Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.) Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.) Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- “Courtroom Trial with Judge, Jury - Vector Image” designed by WannaPik is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Wisconsin State Legislature. (2021). 939.51 Classification of misdemeanors. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/statutes/statutes/939/iv/51 ↵

- Nurses Service Organization and CAN Financial. (2020, June). Nurse professional liability exposure claim report (4th ed.). https://www.nso.com/Learning/Artifacts/Claim-Reports/Minimizing-Risk-Achieving-Excellence ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.) Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- “Balance Scales (Ethics)” by The Open University (OU) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 2: Breach. American Journal of Nursing, 119(9), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000580256.10914.2e ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- Mello, M. M., Frakes, M. D., Blumenkranz, E., & Studdert, D. M. (2020). Malpractice liability and health care quality: A review. JAMA, 323(4), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.21411 ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu ↵

- “PinelRestaint.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2013, July 26). Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html ↵

- Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2013, July 26). Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html ↵

- Nurses Service Organization and CAN Financial. (2020, June). Nurse professional liability exposure claim report (4th ed.). https://www.nso.com/Learning/Artifacts/Claim-Reports/Minimizing-Risk-Achieving-Excellence ↵

- DeLiema, M. (2018). Elder fraud and financial exploitation: Application of routine activity theory. The Gerontologist, 58(4), 706–718. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw258 ↵

- DeLiema, M., Deevy, M., Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2020). Financial fraud among older Americans: Evidence and implications. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(4), 861–868. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby151 ↵

- Wis. JI—Civil 1005. (2016). https://wilawlibrary.gov/jury/civil/instruction.php?n=1005 ↵

- “malpractice.jpg” by Nick Youngson hosted by Pix4free is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 1: Duty. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569476.17357.f5 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 1: Duty. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569476.17357.f5 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 1: Duty. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569476.17357.f5 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 1: Duty. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569476.17357.f5 ↵

- “The_good_samaritan_helping_a_stranger_who_has_been_ignored_b_Wellcome_V0015249.jpg” by S. Smith after C. L. Eastlake is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Otis, A. (2017, May 2). Civil immunity under Wisconsin’s Good Samaritan Law [Memo]. Wisconsin Legislative Council. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lc/information_memos/2017/im_2017_03 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by West and Varacallo and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 1: Duty. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569476.17357.f5 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 1: Duty. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569476.17357.f5 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 2: Breach. American Journal of Nursing, 119(9), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000580256.10914.2e ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 2: Breach. American Journal of Nursing, 119(9), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000580256.10914.2e ↵

- Mello, M. M., Frakes, M. D., Blumenkranz, E., & Studdert, D. M. (2020). Malpractice liability and health care quality: A review. JAMA, 323(4), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.21411 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 2: Breach. American Journal of Nursing, 119(9), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000580256.10914.2e ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 2: Breach. American Journal of Nursing, 119(9), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000580256.10914.2e ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 3A: Causation: A plaintiff must prove not only that a provider departed from acceptable standards of practice--but that this departure caused an injury. American Journal of Nursing, 119(11), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000605380.52689.af ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 3B: Causation. American Journal of Nursing, 120(1), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000652128.66135.55 ↵

- Brous, E. (2019). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 3A: Causation: A plaintiff must prove not only that a provider departed from acceptable standards of practice--but that this departure caused an injury. American Journal of Nursing, 119(11), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000605380.52689.af ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 3B: Causation. American Journal of Nursing, 120(1), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000652128.66135.55 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 3B: Causation. American Journal of Nursing, 120(1), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000652128.66135.55 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

- “damages.jpg” by Nick Youngson hosted by Pix4free is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

- Brous, E. (2020). The elements of a nursing malpractice case, Part 4: Harm. American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656360.21284.50 ↵

James is nearing the end of his associate degree nursing program and is interested in pursuing his first nursing employment opportunity within his community. He has a professional goal of becoming a nurse anesthetist and would like to start as a new graduate in the intensive care unit. He has interviews at three acute care organizations for various ICU positions.

Reflective Questions

- Prior to the interview process, what employment elements should James consider in relation to each position?

- What should James research regarding potential employers before his interviews?

- List important questions for nurses to ask potential employers during the interview process?

- Considering Benner's Novice to Expert theory, what skills sets might be helpful for James to obtain before starting a position in the ICU and working towards becoming a nurse anesthetist?

As James considers the various positions in each organization, he should take time to learn about the populations served and size of the organizations. Certain patient populations may be more beneficial to James's professional development as he progresses in his goal of becoming a nurse anesthetist and, therefore, James should consider what background experience he will gain with each position. Additionally, James should ask potential employers regarding the orientation process within each organization. Intensive care positions can be challenging roles for new graduates, and it is important that James has an understanding of the method of orientation used in the ICU training process. James may also be interested in learning more about tuition reimbursement to facilitate his ongoing education and support from the organization for his continued education.

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[1]

Benner’s Novice to Expert Theory: A theory by Dr. Patricia Benner that explains how new hires develop skills and a holistic understanding of patient care over time, resulting from a combination of a strong educational foundation and thorough clinical experiences. Benner’s theory identifies five levels of nursing experience: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert.

Licensure: The process by which a State Board of Nursing (SBON) grants permission to an individual to engage in nursing practice after verifying the applicant has attained the competency necessary to perform the scope of practice of a registered nurse (RN). The SBON verifies three components:

- Verification of graduation from an approved prelicensure RN nursing education program

- Verification of successful completion of NCLEX-RN examination

- A criminal background check (in some states)[2]

NCLEX-RN: The exam that nursing graduates must pass successfully to obtain their nursing license and become a registered nurse.

NCLEX-RN Test Plan: A concise summary of the content and scope of the NCLEX that serves as an excellent guide for preparing for the exam. These plans are updated every three years based on surveys of newly licensed registered nurses to ensure the NCLEX questions reflect fair, comprehensive, current, and entry-level nursing competency.

Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC): State legislation that allows nurses to practice in other NLC states with their original state’s nursing license without having to obtain additional licenses, contingent upon remaining a resident of that state.

Nurse residency programs: A transition process that provides additional professional development for newly licensed nurses. These programs vary from institution to institution, but many start around the time the new graduate ends their orientation with a preceptor and continue to provide routine support throughout the year.

Orientation: A structured transition process when hired into a new position that may last from one to four months but can be longer depending on the specialty (e.g., Intensive Care or Labor and Delivery). Orientation is based on the new nurse’s demonstration and completion of competencies. During this time the novice RN will work with a preceptor to experience all the aspects of the role.

Portfolio: A compilation of materials showcasing examples of previous work demonstrating one’s skills, qualifications, education, training, and experience.

Preceptors: Experienced and competent RNs who serve as a role model and a resource to a newly hired nurse. These nurses have the knowledge, skills, and the ability to coach the new RN into the nursing role and answer questions while also evaluating a new hire’s performance and providing feedback for improvement.

Resume: A document that highlights one’s background, education, skills, and accomplishments to potential employers.

Temporary permit: A permit issued by the State Board of Nursing (SBON) that allows the applicant to practice practical nursing under the direct supervision of a registered nurse until their RN license is granted.

Benner’s Novice to Expert Theory: A theory by Dr. Patricia Benner that explains how new hires develop skills and a holistic understanding of patient care over time, resulting from a combination of a strong educational foundation and thorough clinical experiences. Benner’s theory identifies five levels of nursing experience: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert.

Licensure: The process by which a State Board of Nursing (SBON) grants permission to an individual to engage in nursing practice after verifying the applicant has attained the competency necessary to perform the scope of practice of a registered nurse (RN). The SBON verifies three components:

- Verification of graduation from an approved prelicensure RN nursing education program

- Verification of successful completion of NCLEX-RN examination

- A criminal background check (in some states)[3]

NCLEX-RN: The exam that nursing graduates must pass successfully to obtain their nursing license and become a registered nurse.

NCLEX-RN Test Plan: A concise summary of the content and scope of the NCLEX that serves as an excellent guide for preparing for the exam. These plans are updated every three years based on surveys of newly licensed registered nurses to ensure the NCLEX questions reflect fair, comprehensive, current, and entry-level nursing competency.

Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC): State legislation that allows nurses to practice in other NLC states with their original state’s nursing license without having to obtain additional licenses, contingent upon remaining a resident of that state.

Nurse residency programs: A transition process that provides additional professional development for newly licensed nurses. These programs vary from institution to institution, but many start around the time the new graduate ends their orientation with a preceptor and continue to provide routine support throughout the year.

Orientation: A structured transition process when hired into a new position that may last from one to four months but can be longer depending on the specialty (e.g., Intensive Care or Labor and Delivery). Orientation is based on the new nurse’s demonstration and completion of competencies. During this time the novice RN will work with a preceptor to experience all the aspects of the role.

Portfolio: A compilation of materials showcasing examples of previous work demonstrating one’s skills, qualifications, education, training, and experience.

Preceptors: Experienced and competent RNs who serve as a role model and a resource to a newly hired nurse. These nurses have the knowledge, skills, and the ability to coach the new RN into the nursing role and answer questions while also evaluating a new hire’s performance and providing feedback for improvement.

Resume: A document that highlights one’s background, education, skills, and accomplishments to potential employers.

Temporary permit: A permit issued by the State Board of Nursing (SBON) that allows the applicant to practice practical nursing under the direct supervision of a registered nurse until their RN license is granted.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the impact of situational stressors within the nursing profession

- Develop strategies to mitigate stress and burnout and maintain engagement in the profession

There is a continued demand for nurses due to complex health care issues facing our country and health care institutions across the world. Nursing is a challenging and demanding profession that requires rigorous educational preparation, clinical expertise, compassion, and the physical and mental capacity to meet a variety of health care needs. The complex demands of the profession can lead to professional burnout and workplace attrition as nurses struggle to balance the challenges of their daily work roles, manage personal and organizational stress, and maintain their health and well-being at home. Nurses are often accustomed to putting aside their own needs to provide care, yet a lack of attention to their personal needs can have significant negative professional consequences. In essence, care for others can easily become compromised when care for self is in jeopardy. Additionally, nurses who do not engage in self-care are more at risk for burnout and attrition from the profession, compounding issues associated with staffing shortages and personnel supply to meet health care demands.[4]

To fully consider the implications of stress management within the nursing profession, one must look no further than the challenges that have arisen as a result of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Each day, news reports highlight the exhaustion being experienced by nurses across the world resulting from health care demands in acute inpatient care, long-term care, school nursing, and public health.[5] With increased job stress, nurses may experience an increased desire to leave the profession and look for other career opportunities.[6] Personal ability to cope with stressors and workplace challenges have been further taxed by ongoing and ever-increasing health care demands. Busy health care systems have struggled to meet care demands as health care personnel have experienced waning professional engagement with decreased time for personal renewal and rejuvenation.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many stressors that previously existed within the nursing profession. This has challenged nurses to find creative methods aimed at increasing self-resilience as a means of meeting the burgeoning health care demands and challenges arising during these uncertain times. Novice nurses who are entering the profession may feel these stressors more acutely than experienced nurses who have already cultivated personal resilience skills. As a result, attention must be given to assisting novice nurses in developing skills to address occupational stress as they navigate their way into the profession. Many novice nurses are experiencing a new challenge of moral distress as they care for COVID patients in environments that are very different from the clinical experiences they had during their education.[7] The nursing profession must acknowledge this new challenge for novice nurses and foster strategies and resources to provide additional emotional support for the unique needs of this group. Professional mentorship and support are even more important in times when many nurses may question their career choice and personally experience waning engagement with the profession.

Finally, it is important for the nursing profession to acknowledge that even outside of the pandemic environment there are unique challenges for long-term engagement. Nurses entering the profession should acknowledge the inherent nature of the work of nursing that can create measurable highs and lows as individuals provide the care and support needed to facilitate the health and well-being of others. Hours are long and care demands are high. Client care needs revolve around a cycle of illness and do not coincide with holidays, summer vacations, and weekend sports. As a result, many new nurses soon realize that job stress related to the schedule burden can become a challenge. It is one of the inherent job stressors that nurses must seek to resolve and manage. Additionally, nurses must recognize that stress management and personal wellness remain important aspects of professional growth throughout the various phases of their career.

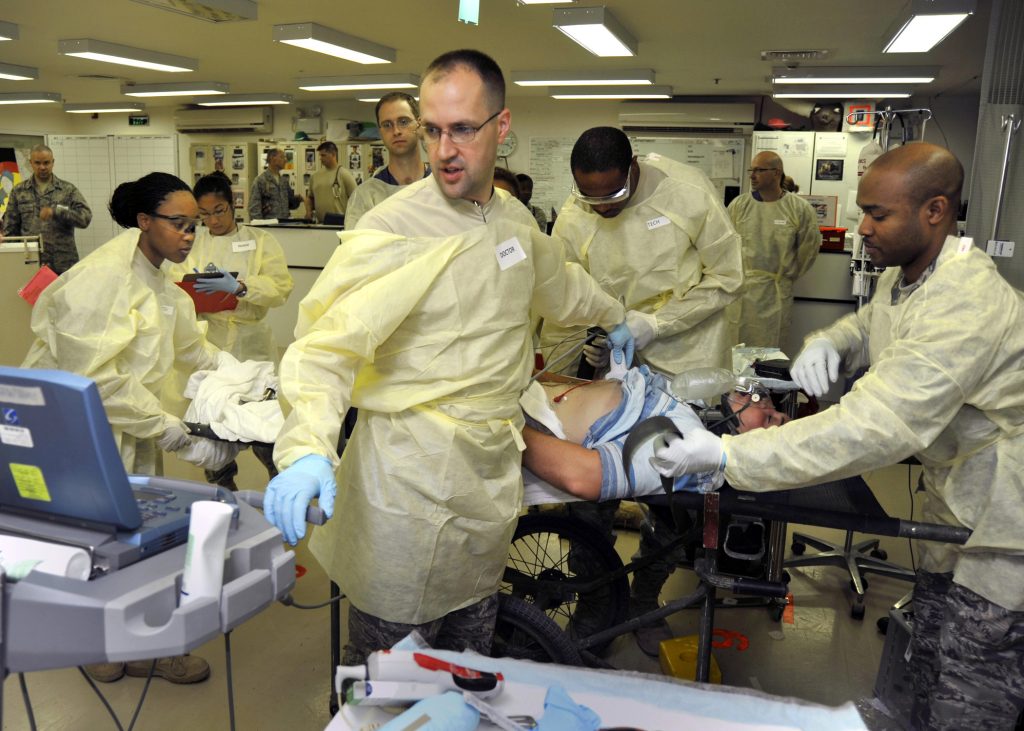

Stress within any health care profession occurs as a result of the challenging and dynamic conditions experienced in day-to-day work. See Figure 12.1[8] for an illustration of stress in a health care environment. Nurses and health care professionals are taxed with supporting clients and families in times of extensive life stress and change. Individuals who seek out care often experience rapid life changes as the result of a new diagnosis, altered body function, death of a family member, or significant mental distress. Nurses are frontline staff members who help clients and their families navigate these health stressors. It can be difficult to provide frontline support without taking on some of the stress encountered. As clients and families navigate their feelings of fear, frustration, anxiety, and anger, nurses are often the support members who first hear and react to these feelings. It is important to recognize the constant barrage of these emotions can take a toll, and it is challenging to not assume this emotional burden.

In addition to the emotional burden of providing support for multiple clients and their family members, nurses experience a variety of other stressors inherent to the health care environment itself. These stressors include issues such as environmental stress, increased workload, changing practice conditions, lack of resources, communication barriers, unfavorable working conditions, frequency of engagement with a variety of personnel, challenges in care coordination, workplace violence, alarm fatigue, and staff turnover. Research has identified that the variety of stressors experienced by nursing staff result in inherently greater levels of stress than that experienced in the wider working population.[9] Therefore, nurses must acknowledge the variety of stressors they encounter within the profession and identify strategies to mitigate these forces.

Nursing is charged with emotional situations and topics even on days when no other situational stressors have significant impact. One cannot participate in the significant conversations that accompany health care decision-making, provide patient education, and promote individual coping without acknowledging these conversations are more impactful than deciding, “What should we make for dinner?” By acknowledging this inherent job stress, nurses recognize that eliminating stress within the profession is not possible. There will always be a level of stress that accompanies the health care environment, and this underscores the importance of stress identification, mitigation, and incorporation of stress-reduction strategies.[10]

Health care professionals must recognize emerging signs of stress that may result from job demands and the nature of health care work. There are a variety of ways that stress can manifest itself. Taking action early can help to prevent workplace burnout. Burnout can be manifested physically and psychologically with a loss of motivation for one’s work. Nurses and other health care professionals must mitigate stress and burnout to sustain engagement with their profession. Failure to acknowledge the implications of professional burnout only exacerbates the cycle as stressors are transferred to remaining team members and colleagues, resulting in the potential for attrition and turnover.

Although the term “stress” often has negative connotations, it is important to remember that not all stress is considered harmful. Normal stress, also referred to as "eustress," does not have lasting consequences and is successfully managed by the individual who is experiencing it.[11] Normal stress, when successfully managed, can increase awareness and focus, resulting in feelings of motivation and competence in the individual who is experiencing it. For example, normal stress may be experienced by a nursing student as they organize their weekly planner specifying time for class, study time, work shifts, or meeting with friends. Although the calendar looks busy, the student can use the stress resulting from a “time-constrained schedule” to motivate oneself to be efficient in completing tasks. This student may feel great satisfaction as they cross off tasks on the “to-do” list. Hopefully, as task achievement occurs, the student transitions from feelings of stress to feelings of empowerment.

Conversely, harmful stress, also referred to as "distress," occurs when stress is not adequately self-managed. Harmful stress is reflected by physical, mental, and behavioral manifestations.[12] See Figure 12.2[13] for an illustration of an individual experiencing harmful stress. Harmful stress can lead to burnout and exhaustion, and if left unaddressed, it can have significant health implications for the individual experiencing it. Let’s return to the example of the nursing student reviewing their busy schedule. Harmful stress can be experienced by a student looking at their busy weekly schedule and feeling overwhelmed and exhausted. Rather than focusing on manageable tasks and crossing items off the list, this student is reluctant to take action and feels distress regarding where to begin. The student demonstrating harmful stress may struggle with overwhelming fatigue, irritability, and may feel overwhelmed with feelings of inadequacy at one’s ability to meet the task requirements.

Harmful stress can impact the employment setting as well. It can damage staff engagement, cause significant physical manifestations, and impede the ability of the employee to safely perform work. Harmful stress can quickly result in the breakdown of collegial relationships and also influence the overall practice environment. Potential signs of harmful stress are described in Table 12.3.

Table 12.3. Harmful Stress: Physical, Mental, & Behavioral Manifestations[14]

| Physical | Headache

Joint discomfort Sleep disturbance Cardiac abnormality (e.g., heart rate, rhythm changes) Increased blood pressure Dry mouth Indigestion Constipation or diarrhea Excessive sweating Dizziness Tremors |

|---|---|

| Mental | Anger

Irritability Mood changes Depression Conflict with friends, family members, coworkers Isolation of self from others Reduced self-confidence |

| Behavioral | Increased alcohol consumption

Smoking or drug use Overeating or loss of appetite Increased arguments with coworkers Increased errors in the workplace |

Nurses and health care professionals should be mindful of the physical, mental, and behavioral manifestations of harmful stress so prompt action can be taken when signs begin to occur. Harmful stress must be addressed early so it does not continue to evolve and lead to career burnout. Additionally, stress can have significant implications beyond one’s career. An individual's physical and emotional health and well-being are strongly aligned with positive stress management. Harmful stress that goes unaddressed can lead to unresolved physical ailments, deterioration in mental and physical well-being, and the breakdown of familial relationships. The negative impact of harmful stress can be difficult to overcome after it has taken hold of an individual.

It can be helpful to mindfully gauge how one is handling stress on a routine basis. See the link to the Perceived Stress Scale in the following box.

Gauge your current level of stress using the State of New Hampshire's Perceived Stress Scale.

Stressors Resulting From the COVID-19 Pandemic

In addition to the inherent stressors that can occur in health care settings as a result of normal job-related tasks and demands, unique challenges and stressors have occurred for nurses as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. See Figure 12.3[15] for an image of a COVID care provider. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 highlights the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the profession. The COVID pandemic has placed extraordinary demands on nurses as they try to meet ever-expanding health care challenges placed on them. Hospitals are continuously overcrowded and needed medical equipment can be sparse.[16] Nurses are asked to provide frontline care to infectious clients with transmission-based precautions in isolation rooms.[17] These nurses then return to their home environments, hoping that they do not spread infection to their families while supporting the needs of the family unit. These continuous job and life stressors compound the physical and psychological demands on nurses. With little respite care for themselves, nurses are at risk for the impact of compounding stressors on their own health.

Read a meta-analysis about interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline professionals during a pandemic.

Health care professionals must recognize emerging signs of stress that may result from job demands and the nature of health care work. There are a variety of ways that stress can manifest itself. Taking action early can help to prevent workplace burnout. Burnout can be manifested physically and psychologically with a loss of motivation for one’s work. Nurses and other health care professionals must mitigate stress and burnout to sustain engagement with their profession. Failure to acknowledge the implications of professional burnout only exacerbates the cycle as stressors are transferred to remaining team members and colleagues, resulting in the potential for attrition and turnover.

Although the term “stress” often has negative connotations, it is important to remember that not all stress is considered harmful. Normal stress, also referred to as "eustress," does not have lasting consequences and is successfully managed by the individual who is experiencing it.[18] Normal stress, when successfully managed, can increase awareness and focus, resulting in feelings of motivation and competence in the individual who is experiencing it. For example, normal stress may be experienced by a nursing student as they organize their weekly planner specifying time for class, study time, work shifts, or meeting with friends. Although the calendar looks busy, the student can use the stress resulting from a “time-constrained schedule” to motivate oneself to be efficient in completing tasks. This student may feel great satisfaction as they cross off tasks on the “to-do” list. Hopefully, as task achievement occurs, the student transitions from feelings of stress to feelings of empowerment.

Conversely, harmful stress, also referred to as "distress," occurs when stress is not adequately self-managed. Harmful stress is reflected by physical, mental, and behavioral manifestations.[19] See Figure 12.2[20] for an illustration of an individual experiencing harmful stress. Harmful stress can lead to burnout and exhaustion, and if left unaddressed, it can have significant health implications for the individual experiencing it. Let’s return to the example of the nursing student reviewing their busy schedule. Harmful stress can be experienced by a student looking at their busy weekly schedule and feeling overwhelmed and exhausted. Rather than focusing on manageable tasks and crossing items off the list, this student is reluctant to take action and feels distress regarding where to begin. The student demonstrating harmful stress may struggle with overwhelming fatigue, irritability, and may feel overwhelmed with feelings of inadequacy at one’s ability to meet the task requirements.

Harmful stress can impact the employment setting as well. It can damage staff engagement, cause significant physical manifestations, and impede the ability of the employee to safely perform work. Harmful stress can quickly result in the breakdown of collegial relationships and also influence the overall practice environment. Potential signs of harmful stress are described in Table 12.3.

Table 12.3. Harmful Stress: Physical, Mental, & Behavioral Manifestations[21]

| Physical | Headache

Joint discomfort Sleep disturbance Cardiac abnormality (e.g., heart rate, rhythm changes) Increased blood pressure Dry mouth Indigestion Constipation or diarrhea Excessive sweating Dizziness Tremors |

|---|---|

| Mental | Anger

Irritability Mood changes Depression Conflict with friends, family members, coworkers Isolation of self from others Reduced self-confidence |

| Behavioral | Increased alcohol consumption

Smoking or drug use Overeating or loss of appetite Increased arguments with coworkers Increased errors in the workplace |

Nurses and health care professionals should be mindful of the physical, mental, and behavioral manifestations of harmful stress so prompt action can be taken when signs begin to occur. Harmful stress must be addressed early so it does not continue to evolve and lead to career burnout. Additionally, stress can have significant implications beyond one’s career. An individual's physical and emotional health and well-being are strongly aligned with positive stress management. Harmful stress that goes unaddressed can lead to unresolved physical ailments, deterioration in mental and physical well-being, and the breakdown of familial relationships. The negative impact of harmful stress can be difficult to overcome after it has taken hold of an individual.

It can be helpful to mindfully gauge how one is handling stress on a routine basis. See the link to the Perceived Stress Scale in the following box.

Gauge your current level of stress using the State of New Hampshire's Perceived Stress Scale.

Stressors Resulting From the COVID-19 Pandemic

In addition to the inherent stressors that can occur in health care settings as a result of normal job-related tasks and demands, unique challenges and stressors have occurred for nurses as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. See Figure 12.3[22] for an image of a COVID care provider. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 highlights the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the profession. The COVID pandemic has placed extraordinary demands on nurses as they try to meet ever-expanding health care challenges placed on them. Hospitals are continuously overcrowded and needed medical equipment can be sparse.[23] Nurses are asked to provide frontline care to infectious clients with transmission-based precautions in isolation rooms.[24] These nurses then return to their home environments, hoping that they do not spread infection to their families while supporting the needs of the family unit. These continuous job and life stressors compound the physical and psychological demands on nurses. With little respite care for themselves, nurses are at risk for the impact of compounding stressors on their own health.

Read a meta-analysis about interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline professionals during a pandemic.

In addition to recognizing stress manifestations in oneself, health care professionals must identify signs of stress in others. All members of the health care team experience stress, and effective coping can quickly turn into ineffective coping when manageable, normal stress shifts to harmful stress. Nurses should understand how stress may manifest in a colleague and how one can help and intervene if signs of harmful stress occur.

The signs of harmful stress in a colleague often manifest in a similar manner to what is seen in oneself, but certain signs may be more readily identified by an external source. It is not unusual to identify the mental or behavioral signs of harmful stress in a colleague more rapidly than the physical manifestations. Individuals should be mindful of signs of harmful stress in others, such as changes in mood, irritability, signs of fatigue, increased errors, and absenteeism.[25] Individuals exhibiting these signs may be signaling they are struggling to manage harmful stress. It is important to promptly address these signs with the individual. The tendency to assume one can self-manage or will “get over it” can lead to feelings of isolation that will only perpetuate the stress.

When observing potential signs of harmful stress in a colleague, providing an opportunity to discuss the stressors can be a valuable avenue for promoting effective coping. It is important to remember that the individual exhibiting signs of harmful stress may not recognize they are impacted by stress, but having a colleague acknowledge one’s change in mood or attitude can open the opportunity for self-reflection. Although acknowledging signs of harmful stress in a colleague may feel awkward, asking if someone is okay and addressing signs of potential harmful stress can be a significant step in helping them cope. Acknowledgement can occur with statements such as, “I noticed that you seem more frustrated at work lately. Is everything okay?” or “You seem to be more quiet in the breakroom after our shifts. How are you feeling? I know the busy days can really add up.” Simple statements and questions open opportunities to share feelings and frustrations and also demonstrate caring for team members.[26] This approach creates dialogue about stressful experiences and provides support needed to positively address harmful stress.

In addition to demonstrating care for one’s colleague by inviting conversation about harmful stress, sharing resources is also helpful. It is important for nurses to know they are not alone in experiencing feelings of stress, and attention to these feelings can help one develop strategies to positively address them. Planning discussions with a trusted mentor or friend can be very helpful when exploring feelings related to stress. These discussions also provide an opportunity to share information regarding coping strategies such as mindfulness interventions, resiliency programs, or other formalized resources like employee assistance programs.[27] There are also routine workplace measures that significantly impact stress reduction. For example, many nurses do not take the time to ensure they are taking breaks, eating healthy meals, or simply removing themselves from the care environment for brief periods of time. Simple strategies that can dramatically reduce workplace stress include taking a brief walk outside during one’s lunch break or taking a few deep breaths prior to the beginning of a work shift. Other simple measures such as daily exercise and meditation can reduce stress and increase confidence to address the tasks at hand.[28] Although experienced nurses may already be incorporating these strategies, it is important for novice nurses to understand the value of these strategies.

In addition to recognizing stress manifestations in oneself, health care professionals must identify signs of stress in others. All members of the health care team experience stress, and effective coping can quickly turn into ineffective coping when manageable, normal stress shifts to harmful stress. Nurses should understand how stress may manifest in a colleague and how one can help and intervene if signs of harmful stress occur.

The signs of harmful stress in a colleague often manifest in a similar manner to what is seen in oneself, but certain signs may be more readily identified by an external source. It is not unusual to identify the mental or behavioral signs of harmful stress in a colleague more rapidly than the physical manifestations. Individuals should be mindful of signs of harmful stress in others, such as changes in mood, irritability, signs of fatigue, increased errors, and absenteeism.[29] Individuals exhibiting these signs may be signaling they are struggling to manage harmful stress. It is important to promptly address these signs with the individual. The tendency to assume one can self-manage or will “get over it” can lead to feelings of isolation that will only perpetuate the stress.

When observing potential signs of harmful stress in a colleague, providing an opportunity to discuss the stressors can be a valuable avenue for promoting effective coping. It is important to remember that the individual exhibiting signs of harmful stress may not recognize they are impacted by stress, but having a colleague acknowledge one’s change in mood or attitude can open the opportunity for self-reflection. Although acknowledging signs of harmful stress in a colleague may feel awkward, asking if someone is okay and addressing signs of potential harmful stress can be a significant step in helping them cope. Acknowledgement can occur with statements such as, “I noticed that you seem more frustrated at work lately. Is everything okay?” or “You seem to be more quiet in the breakroom after our shifts. How are you feeling? I know the busy days can really add up.” Simple statements and questions open opportunities to share feelings and frustrations and also demonstrate caring for team members.[30] This approach creates dialogue about stressful experiences and provides support needed to positively address harmful stress.

In addition to demonstrating care for one’s colleague by inviting conversation about harmful stress, sharing resources is also helpful. It is important for nurses to know they are not alone in experiencing feelings of stress, and attention to these feelings can help one develop strategies to positively address them. Planning discussions with a trusted mentor or friend can be very helpful when exploring feelings related to stress. These discussions also provide an opportunity to share information regarding coping strategies such as mindfulness interventions, resiliency programs, or other formalized resources like employee assistance programs.[31] There are also routine workplace measures that significantly impact stress reduction. For example, many nurses do not take the time to ensure they are taking breaks, eating healthy meals, or simply removing themselves from the care environment for brief periods of time. Simple strategies that can dramatically reduce workplace stress include taking a brief walk outside during one’s lunch break or taking a few deep breaths prior to the beginning of a work shift. Other simple measures such as daily exercise and meditation can reduce stress and increase confidence to address the tasks at hand.[32] Although experienced nurses may already be incorporating these strategies, it is important for novice nurses to understand the value of these strategies.

The impact of inadequate stress management for health care personnel can greatly impact health care organizations. When harmful stress is not adequately addressed, burnout can rapidly become a burgeoning problem resulting in absenteeism, decreased productivity, decline in care quality, staff dissatisfaction, and employee turnover. Work environment and lack of workplace support often contribute to feelings of burnout and job attrition.[33] Organizations must recognize the significance of stress in regard to the cyclical nature it plays in the retention of employees. For example, if one employee experiences harmful stress resulting in depression and anxiety, this may influence their timeliness and attendance at work. If the employee begins to struggle, they may be more inclined to phone in as “sick time” for shifts or even be a “no show” for a scheduled shift. When this occurs, the burden of their absence is passed on to other employees on the unit. Calls for overtime, mandated stay, or increased client care assignments quickly increase the burden on the other members of the health care team. As a result, the team members experiencing increased workload feel an impact on their own job-related stress. The compounded stress can quickly overtax an individual who has been managing normal work-related stress. Many individuals who were previously self-managing stress may struggle under these increased role demands. When there is a decrease in an individual’s “downtime,” there is even less reprieve from the stressful work environment. As a result, the organization and health care system become even more overtaxed, and the cycle perpetuates itself among other staff.[34] Managers and directors often struggle with rehiring and orienting staff at a rate that is suitable to offset the stress cycle and decreased retention within the organization.

Promoting Nurse Retention

Nurse leaders must be proactive in finding solutions to address clinical nurse and nursing faculty shortages and high nurse turnover rates. The 2018 National Healthcare Retention and RN Staffing Report states the following data[35]:

- The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 233,000 new RN jobs will be created annually.

- Forty-five percent of hospitals anticipate increasing their RN staff.

- Hospital turnover is at 18.2%, an increase from previous years.