Assessment

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

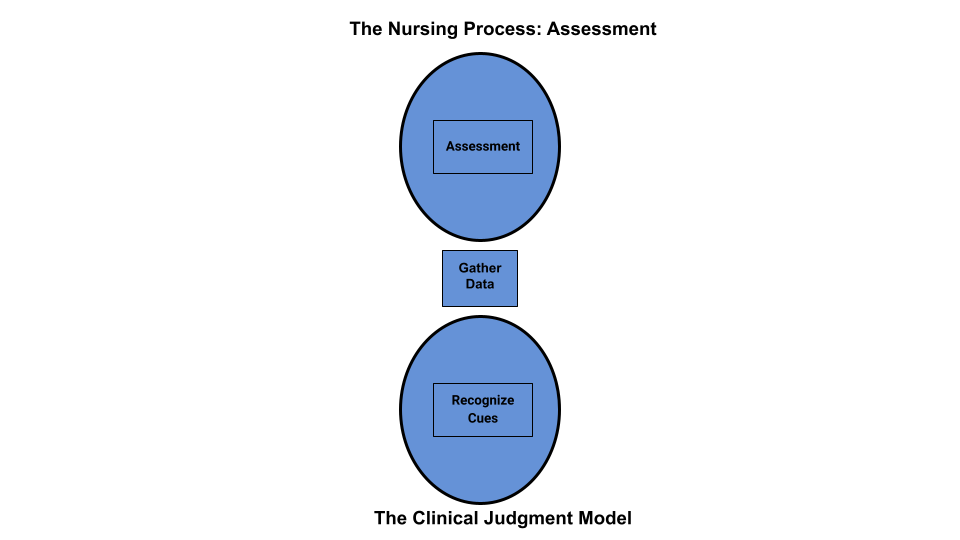

Assessment is the first step of the nursing process (and the first Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.” This includes collecting “pertinent data related to the health and quality of life in a systematic, ongoing manner, with compassion and respect for the wholeness, inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person, including, but not limited to, demographics, environmental and occupational exposures, social determinants of health, health disparities, physical, functional, psychosocial, emotional, cognitive, spiritual/transpersonal, sexual, sociocultural, age-related, environmental, and lifestyle/economic assessments.”[1] See Figure 4.5a for an illustration of how the Assessment phase of the nursing process corresponds to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM).[2]

Figure 4.5a Comparison of the Assessment Phase of the Nursing Process to the NCJMM

Nurses assess clients to gather information, then use critical thinking to analyze the data and recognized cues. Data is considered subjective or objective and can be collected from multiple sources.

Subjective Assessment Data

Subjective data is information obtained from the client and/or family members and offers important cues from their perspectives. When documenting subjective data stated by a client, it should be in quotation marks and start with verbiage such as, “The client reports…” It is vital for the nurse to establish rapport with a client to obtain accurate, valuable subjective data regarding the mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of their condition.

There are two types of subjective information, primary and secondary. Primary data is information provided directly by the client. Clients are the best source of information about their bodies and feelings, and the nurse who actively listens to a client will often learn valuable information while also promoting a sense of well-being. Information collected from a family member, chart, or other sources is known as secondary data. Family members can provide important information, especially for individuals with memory impairments, infants, children, or when clients are unable to speak for themselves.

See Figure 4.5b[3] for an illustration of a nurse obtaining subjective data and establishing rapport after obtaining permission from the client to sit on the bed.

Example of Subjective Data

An example of how to document subjective data obtained during a client assessment is, “The client reports, ‘My pain is a level 2 on a 1-10 scale.’”

Objective Assessment Data

Objective data is anything that you can observe through your sense of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the client. Objective data is reproducible, meaning another person can easily obtain the same data. Examples of objective data are vital signs, physical examination findings, and laboratory results. See Figure 4.6[4] for an image of a nurse performing a physical examination.

Example of Objective Data

An example of documented objective data obtained during a client assessment is, “The client’s radial pulse is 58 and regular, and their skin feels warm and dry.”

Sources of Assessment Data

There are three sources of assessment data: interview, physical examination, and review of laboratory or diagnostic test results.

Interviewing

Interviewing includes asking the client and their family members questions, listening, and observing verbal and nonverbal communication. Reviewing the chart prior to interviewing the client may eliminate redundancy in the interview process and allows the nurse to hone in on the most significant areas of concern or need for clarification. However, if information in the chart does not make sense or is incomplete, the nurse should use the interview process to verify data with the client.

After performing client identification, the best way to initiate a caring relationship is to introduce yourself to the client and explain your role. Share the purpose of your interview and the approximate time it will take. When beginning an interview, it may be helpful to start with questions related to the client’s medical diagnoses. Medical diagnoses are diseases, disorders, or injuries diagnosed by a physician or advanced health care provider, such as a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant. Reviewing the medical diagnoses allows the nurse to gather information about how they have affected the client’s functioning, relationships, and lifestyle. Listen carefully and ask for clarification when something isn’t clear to you. Clients may not volunteer important information because they don’t realize it is important for their care. By using critical thinking and active listening, you may discover valuable cues that are important to provide safe, quality nursing care. Sometimes nursing students can feel uncomfortable having difficult conversations or asking personal questions due to generational or other cultural differences. Don’t shy away from asking about information that is important to know for safe client care. Most clients will be grateful that you cared enough to ask and listen.

Be alert and attentive to how the client answers questions, as well as when they do not answer a question. Nonverbal communication and body language can be cues to important information that requires further investigation. A keen sense of observation is important. To avoid making inappropriate inferences, the nurse should validate cues for accuracy. For example, a nurse may make an inference that a client appears depressed when the client avoids making eye contact during an interview. However, upon further questioning, the nurse may discover that the client’s cultural background believes direct eye contact to be disrespectful and this is why they are avoiding eye contact. To read more information about communicating with clients, review the “Communication” chapter of this book.

Physical Examination

A physical examination is a systematic data collection method of the body that uses the techniques of inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion. Inspection is the observation of a client’s anatomical structures. Auscultation is listening to sounds, such as heart, lung, and bowel sounds, created by organs using a stethoscope. Palpation is the use of touch to evaluate organs for size, location, or tenderness. Percussion is an advanced physical examination technique typically performed by providers where body parts are tapped with fingers to determine their size and if fluid or air are present. Detailed physical examination procedures of various body systems can be found in the Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e textbook with a head-to-toe checklist in Appendix C. Physical examination also includes the collection and analysis of vital signs.

Registered nurses (RNs) complete the initial physical examination and analyze the findings as part of the nursing process. Collection of follow-up physical examination data can be delegated to licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs), or measurements such as vital signs and weight may be delegated to trained unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) when appropriate to do so. However, the RN remains responsible for supervising these tasks, analyzing the findings, and ensuring they are documented.

A physical examination can be performed as a comprehensive head-to-toe assessment or as a focused assessment related to a particular condition or problem. Assessment data is documented in the client’s medical record, either in their electronic medical record (EMR) or their paper chart, depending upon agency policies and procedures.

Reviewing Laboratory and Diagnostic Test Results

Reviewing laboratory and diagnostic test results provides relevant and useful information related to the needs of the client. Understanding how normal and abnormal results affect client care is important when implementing the nursing care plan and administering provider prescriptions. If results cause concern, it is the nurse’s responsibility to notify the provider and verify the appropriateness of prescriptions based on the client’s current status before implementing them.

Types of Assessments

Several types of nursing assessment are used in clinical practice:

- Primary Survey: Used during every client encounter to briefly evaluate level of consciousness, airway, breathing, and circulation and implement emergency care if needed.

- Admission Assessment: A comprehensive assessment completed when a client is admitted to a facility that involves assessing a large amount of information using an organized approach.

- Ongoing Assessment: In acute care agencies such as hospitals, a head-to-toe assessment is completed and documented at least once every shift. Any changes in client condition are reported to the health care provider.

- Focused Assessment: Focused assessments are used to reevaluate the status of a previously diagnosed problem.

- Time-lapsed Reassessment: Time-lapsed reassessments are used in long-term care facilities when three or more months have elapsed since the previous assessment to evaluate progress on previously identified outcomes.[5]

Putting It Together

Review Scenario C in the following box to apply concepts of assessment to a client scenario.

Scenario C[6]

Ms. J. is a 74-year-old woman who is admitted directly to the medical unit after visiting her physician because of shortness of breath, increased swelling in her ankles and calves, and fatigue. Her medical history includes hypertension (30 years), coronary artery disease (18 years), heart failure (2 years), and type 2 diabetes (14 years). She takes 81 mg of aspirin every day, metoprolol 50 mg twice a day, furosemide 40 mg every day, and metformin 2,000 mg every day.

Ms. J.’s vital sign values on admission were as follows:

- Blood Pressure: 162/96 mm Hg

- Heart Rate: 88 beats/min

- Oxygen Saturation: 91% on room air

- Respiratory Rate: 28 breaths/minute

- Temperature: 97.8 degrees F orally

Her weight is up 10 pounds since the last office visit three weeks prior. The client states, “I am so short of breath” and “My ankles are so swollen I have to wear my house slippers.” Ms. J. also shares, “I am so tired and weak that I can’t get out of the house to shop for groceries,” and “Sometimes I’m afraid to get out of bed because I get so dizzy.” She confides, “I would like to learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.”

The physical assessment findings of Ms. J. are bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs and bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet. Laboratory results indicate a decreased serum potassium level of 3.4 mEq/L.

As the nurse completes the physical assessment, the client’s daughter enters the room. She confides, “We are so worried about mom living at home by herself when she is so tired all the time!”

Critical Thinking Questions

- Identify relevant subjective data.

- Identify relevant objective data.

- Provide an example of secondary data.

Answers are located in the Answer Key at the end of the book.

Media Attributions

- Assessment in the Nursing Process Compared to NCJMM

- 13394660711603

- grandmother-1546855_1920

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Assessment in the Nursing Process Compared to the NCJMM” by Tami Davis is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “361341143-huge.jpg” by Monkey Business Images is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- “13394660711603.jpg” by CDC/Amanda Mills is in the Public Domain ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- “grandmother-1546855_960_720.jpg” by vendie4u is licensed under CC0 ↵

As discussed previously, the American Nurses Association (ANA) defines advocacy at the individual level as educating health care consumers so they can consider actions, interventions, or choices related to their own personal beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge to achieve the desired outcome. In this way, the health care consumer learns self-management and decision-making.[1] Advocacy at the interpersonal level is defined as empowering health care consumers by providing emotional support, assistance in obtaining resources, and necessary help through interactions with families and significant others in their social support network.[2]

What does advocacy look like in a nurse’s daily practice? The following are some examples provided by an oncology nurse[3]:

- Ensure Safety. Ensure the client is safe when being treated in a health care facility and when they are discharged by communicating with case managers or social workers about the client’s need for home health or assistance after discharge so it is arranged before they go home.

- Give Clients a Voice. Give clients a voice when they are vulnerable by staying in the room with them while the doctor explains their diagnosis and treatment options to help them ask questions, get answers, and translate information from medical jargon.

- Educate. Educate clients on how to manage their current or chronic conditions to improve the quality of their everyday life. For example, clients undergoing chemotherapy can benefit from the nurse teaching them how to take their anti-nausea medication in a way that will be most effective for them and will allow them to feel better between treatments.

- Protect Patient Rights. Know clients’ wishes for their care. Advocacy may include therapeutically communicating a client’s wishes to an upset family member who disagrees with their choices. In this manner, the client’s rights are protected and a healing environment is established.

- Double-Check for Errors. Know that everyone makes mistakes. Nurses often identify, stop, and fix errors made by interprofessional team members. They flag conflicting orders from multiple providers and notice oversights. Nurses should read provider orders and carefully compare new orders to previous documentation. If an order is unclear or raises concerns, a nurse should discuss their concerns with another nurse, a charge nurse, a pharmacist, or the provider before implementing it to ensure patient safety.

- Connect Clients to Resources. Help clients find resources inside and outside the hospital to support their well-being. Know resources in your agency, such as case managers or social workers who can assist with financial concerns, advance directives, health insurance, or transportation concerns. Request assistance from agency chaplains to support spiritual concerns. Promote community resources, such as patient or caregiver support networks, Meals on Wheels, or other resources to meet their needs.

Nurses must recognize their unique position in client advocacy to empower individuals to provide them with the support and resources to make their best judgment. The intimate and continuous nature of the nurse-patient relationship places nurses in a prime position to identify and address the needs and concerns of their patients. This relationship is built on trust, empathy, and consistent interaction, which allows nurses to gain a deep understanding of their patients' values, preferences, and personal circumstances. By leveraging this close proximity and strong rapport, nurses can effectively advocate for their patients, ensuring that their voices are heard, and their wishes are respected in all aspects of care.[4]

The power of the nurse-patient relationship extends beyond the immediate clinical environment. Nurses often act as liaisons between patients and the broader health care team, facilitating communication and ensuring that patient preferences are integrated into care plans. This advocacy role is crucial in navigating complex health care systems where patients may feel overwhelmed or marginalized. Nurses can help demystify medical jargon, explain treatment options, and support patients in making informed decisions that align with their values and goals. Through education and emotional support, nurses empower patients to take an active role in their own care, enhancing patient autonomy and satisfaction.[5]

In addition to direct patient care, nurses play a pivotal role in identifying systemic issues that affect patient outcomes. Their frontline perspective provides valuable insights into the barriers patients face in accessing quality care, such as socioeconomic challenges, cultural barriers, and institutional policies. By advocating for policy changes and improvements in health care delivery, nurses contribute to creating a more equitable and patient-centered health care system. Their advocacy efforts can lead to the implementation of practices and policies that better address the needs of diverse patient populations, ultimately improving health outcomes on a broader scale.[6]

Nurses' advocacy is also essential in situations where patients are unable to speak for themselves, such as in cases of severe illness, disability, or end-of-life care. In these instances, nurses must be vigilant in recognizing and addressing the needs of vulnerable patients, ensuring that their rights and dignity are upheld. This may involve working closely with families and caregivers, coordinating with interdisciplinary teams, and navigating ethical dilemmas to provide the best possible care for the patient.

As discussed previously, the American Nurses Association (ANA) defines advocacy at the individual level as educating health care consumers so they can consider actions, interventions, or choices related to their own personal beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge to achieve the desired outcome. In this way, the health care consumer learns self-management and decision-making.[7] Advocacy at the interpersonal level is defined as empowering health care consumers by providing emotional support, assistance in obtaining resources, and necessary help through interactions with families and significant others in their social support network.[8]

What does advocacy look like in a nurse’s daily practice? The following are some examples provided by an oncology nurse[9]:

- Ensure Safety. Ensure the client is safe when being treated in a health care facility and when they are discharged by communicating with case managers or social workers about the client’s need for home health or assistance after discharge so it is arranged before they go home.

- Give Clients a Voice. Give clients a voice when they are vulnerable by staying in the room with them while the doctor explains their diagnosis and treatment options to help them ask questions, get answers, and translate information from medical jargon.

- Educate. Educate clients on how to manage their current or chronic conditions to improve the quality of their everyday life. For example, clients undergoing chemotherapy can benefit from the nurse teaching them how to take their anti-nausea medication in a way that will be most effective for them and will allow them to feel better between treatments.

- Protect Patient Rights. Know clients’ wishes for their care. Advocacy may include therapeutically communicating a client’s wishes to an upset family member who disagrees with their choices. In this manner, the client’s rights are protected and a healing environment is established.

- Double-Check for Errors. Know that everyone makes mistakes. Nurses often identify, stop, and fix errors made by interprofessional team members. They flag conflicting orders from multiple providers and notice oversights. Nurses should read provider orders and carefully compare new orders to previous documentation. If an order is unclear or raises concerns, a nurse should discuss their concerns with another nurse, a charge nurse, a pharmacist, or the provider before implementing it to ensure patient safety.

- Connect Clients to Resources. Help clients find resources inside and outside the hospital to support their well-being. Know resources in your agency, such as case managers or social workers who can assist with financial concerns, advance directives, health insurance, or transportation concerns. Request assistance from agency chaplains to support spiritual concerns. Promote community resources, such as patient or caregiver support networks, Meals on Wheels, or other resources to meet their needs.

Nurses must recognize their unique position in client advocacy to empower individuals to provide them with the support and resources to make their best judgment. The intimate and continuous nature of the nurse-patient relationship places nurses in a prime position to identify and address the needs and concerns of their patients. This relationship is built on trust, empathy, and consistent interaction, which allows nurses to gain a deep understanding of their patients' values, preferences, and personal circumstances. By leveraging this close proximity and strong rapport, nurses can effectively advocate for their patients, ensuring that their voices are heard, and their wishes are respected in all aspects of care.[10]

The power of the nurse-patient relationship extends beyond the immediate clinical environment. Nurses often act as liaisons between patients and the broader health care team, facilitating communication and ensuring that patient preferences are integrated into care plans. This advocacy role is crucial in navigating complex health care systems where patients may feel overwhelmed or marginalized. Nurses can help demystify medical jargon, explain treatment options, and support patients in making informed decisions that align with their values and goals. Through education and emotional support, nurses empower patients to take an active role in their own care, enhancing patient autonomy and satisfaction.[11]

In addition to direct patient care, nurses play a pivotal role in identifying systemic issues that affect patient outcomes. Their frontline perspective provides valuable insights into the barriers patients face in accessing quality care, such as socioeconomic challenges, cultural barriers, and institutional policies. By advocating for policy changes and improvements in health care delivery, nurses contribute to creating a more equitable and patient-centered health care system. Their advocacy efforts can lead to the implementation of practices and policies that better address the needs of diverse patient populations, ultimately improving health outcomes on a broader scale.[12]

Nurses' advocacy is also essential in situations where patients are unable to speak for themselves, such as in cases of severe illness, disability, or end-of-life care. In these instances, nurses must be vigilant in recognizing and addressing the needs of vulnerable patients, ensuring that their rights and dignity are upheld. This may involve working closely with families and caregivers, coordinating with interdisciplinary teams, and navigating ethical dilemmas to provide the best possible care for the patient.

National, state, and local policies impact nurses at all levels of care, from nurse administrators to bedside nurses, making it essential for nurses to take an active role in advocating for their clients, their profession, and their community. Nurses advocate for improved access to basic health care, enhanced funding of health care services, and safe practice environments by participating in policy discussions. Nurses also participate in state and national policy discussions affecting nursing practice. For example, nurses advocate for the removal of practice barriers so nurses can practice according to the full extent of their education, certification, and licensure; address reimbursement based on the value of nursing care; and expand funding for nursing education.[13]

When advocating, nurses must view themselves as knowledgeable professionals who have the power to influence policy and decision-makers. A nurse can advocate for improved policies through a variety of pathways. Each method provides a unique opportunity for the nurse to impact the health of individuals and communities, the profession of nursing, and the overall health care provided to clients. These are few easy ways for nurses to get involved:

- Becoming involved in professional nursing organizations

- Engaging in conversations with local, state, and federal policymakers on health care related issues

- Participating in shared governance committees regarding workplace policies

Health Care Legislative Policies

Legislative policies are external rules and regulations that impact health care practice and policy at the national, state, and local levels. These regulations seek to protect clients and nurses by defining safe practices, quality standards, and requirements for health care organizations and insurance companies. Nurses have been involved in the adoption of these rules and regulations and continue to advocate for new and updated legislation affecting health care.

Examples of federal legislation addressing health care include advocating for the Patient’s Bill of Rights, patient privacy and confidentiality, improved access to health care, and protections for individuals who report unethical or illegal activities in the health care environment (i.e., whistleblower legislation). Examples of legislation at the state level includes topics such as right-to-die and physician-assisted suicide, medicinal marijuana use, and nurse-to-patient staffing ratios.

Review how patient rights are defined by policies at the federal, state, and organizational levels in the following box.

Patient’s Rights Defined at Multiple Levels

In 1973 the American Hospital Association (AHA) adopted the Patient’s Bill of Rights. The bill has since been updated and adapted for use throughout the world in all health care settings, but, in general, it safeguards a patient’s right to accurate and complete information, fair treatment, and self-determination when making health care decisions. In 2010 the Affordable Care Act was passed at the federal level. It included additional patient rights and protections for health care consumers in the areas of preexisting conditions, choice of providers, and limited lifetime coverage limits imposed by insurance companies.

States further define patient rights beyond federal regulations and provide specific rights of health care consumers in their state. For example, Wisconsin’s Department of Health Services defines treatment rights, protections for records privacy and access, communication rights, personal rights, and privacy rights.

Read more about Patient Rights in the American Healthcare System.

Visit the CMS web page to read more about the Affordable Care Act and the revised Patient’s Bill of Rights.

Research advocacy policies in your state. Here is Wisconsin’s law regarding client rights.

Nurses’ Roles in Legislative Policies

With over four million registered nurses in the United States, nursing has a powerful voice that can significantly influence health care legislation. Nurses have been recognized as a major influence on health care policies related to client safety and quality care. They can become involved in policy making at the state and federal level by joining a professional nursing organization, communicating with their state representatives, or running for political office to take an active role in policy creation.

Most professional nursing organizations have a legislative policy committee that reviews proposed federal and state legislation and makes recommendations for change, endorses the legislation, or leads opposition. For example, organizations such as the American Nurses Association (ANA), National League of Nursing (NLN), and state nursing associations inform members of current legislative initiatives, provide comprehensive reviews, and encourage members to contact their representatives about pending legislation.

Read more about current advocacy efforts by the Wisconsin Nurses Association.

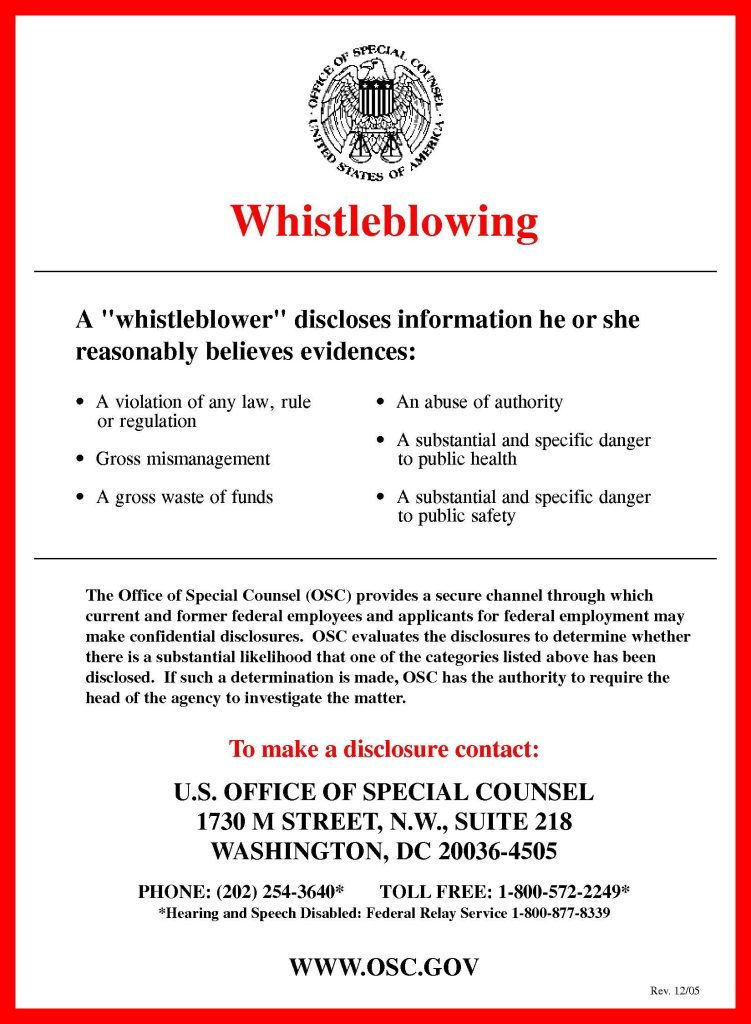

Whistleblowing

Nurses are expected to follow federal, state, and agency policies and regulations, be proactive in policy development, and speak up when policies are not being followed. When regulations and policies are not being followed, nurses must advocate for public safety by reporting the problem to a higher authority. Whistleblowing refers to reporting a significant concern to your supervisor, the federal or state agency responsible for the regulation, or in the case of criminal activity, to law enforcement agencies. A whistleblower is a person who exposes any kind of information or activity that is deemed illegal, unethical, or not correct within an organization. See Figure 10.5[14] for federal instructions regarding whistleblowing.

Whistleblowing typically begins with reporting the wrongdoing to a supervisor and following the internal chain of command. This first step of reporting allows the organization to correct the issue internally. However, there may be situations where an individual may need to directly report to an external authority, such as a State Board of Nursing or another regulatory agency. For example, any person who has knowledge of conduct by a licensed nurse violating state or federal law may report the alleged violation to the State Board of Nursing where the conduct occurred.

Acting as a whistleblower can be a difficult decision because the individual may be labelled “disloyal” or potentially face retaliatory actions by the accused individual or organization. Although there are legal protections for whistleblowers, these types of actions may occur. Read important information from the ANA regarding whistleblowing in the following box.

ANA Information Regarding Whistleblowing[15]

- If you identify an illegal or unethical practice, reserve judgment until you have adequate documentation to establish wrongdoing.

- Do not expect those who are engaged in unethical or illegal conduct to welcome your questions or concerns about this practice.

- Seek the counsel of someone you trust outside of the situation to provide you with an objective perspective.

- Consult with your state nurses’ association or legal counsel if possible before taking action to determine how best to document your concerns.

- Remember, you are not protected in a whistleblower situation from retaliation by your employer until you blow the whistle.

- Blowing the whistle means that you report your concern to the national and/or state agency responsible for regulation of the organization for which you work or, in the case of criminal activity, to law enforcement agencies as well.

- Private groups, such as The Joint Commission or the National Committee for Quality Assurance, do not confer protection. You must report to a state or national regulator.

- Although it is not required by every regulatory agency, it is a good rule of thumb to put your complaint in writing.

- Document all interactions related to the whistleblowing situation and keep copies for your personal file.

- Keep documentation and interactions objective.

- Remain calm and do not lose your temper, even if those who learn of your actions attempt to provoke you.

- Remember that blowing the whistle is a very serious matter. Do not blow the whistle frivolously. Make sure you have the facts straight before taking action.

To become a nursing advocate, identify causes, issues, or needs where YOU can exert influence.

Steps to becoming an advocate include the following[16]:

- Identify a problem that interests you: Start by pinpointing a specific issue or area within nursing that you are passionate about. This could range from patient safety and quality of care to workplace conditions and professional development opportunities.

- Research the subject and select an evidence-based intervention: Conduct thorough research on the identified issue. Look for evidence-based practices and interventions that have been proven to address or mitigate the problem effectively. Gathering robust data will help you build a solid case for your advocacy efforts.

- Network with experts who are, or could be, involved in making the change: Connect with professionals and experts who are either already involved in addressing the issue or who could play a crucial role in implementing changes. Building a network of like-minded individuals can provide support, resources, and additional perspectives.

- Work hard for change: Advocacy requires dedication and persistence. Actively participate in efforts to bring about the desired change. This might include engaging in public speaking, writing articles or blogs, meeting with policymakers, or organizing community events to raise awareness.

Once you have identified a topic of interest, it's crucial to get involved in activities that can amplify your advocacy efforts:

- Committees: Volunteer to participate in committees that review and develop practice policies within your health care institution.

- Professional Nursing Organizations: Become a member of state and national nursing organizations. These groups often provide valuable resources, including access to current legislative and policy initiatives, public policy agendas, and ways to get involved.

- Research and Review: Stay informed by researching best practices and reviewing the health policy agendas of elected officials. Understanding the current landscape will help you identify opportunities to influence policy and practice.

Nurses hold a powerful position to be effective advocates due to their frontline role in health care delivery. Their unique insights into patient care, the work environment, and health care systems make them valuable voices in policy discussions. As the largest sector of the health care workforce, nurses have significant potential to influence decisions at every level.

Advocating for change can lead to improved quality of care, better patient outcomes, and safe work environments. By pushing for evidence-based practices and policies, nurses can help ensure that patients receive the best possible care. Advocacy efforts focused on patient safety and quality can directly impact patient health and recovery. Additionally, nurses can advocate for better working conditions, which can lead to a safer and more supportive environment for all healthcare workers.

Imagine the impact if every nurse actively engaged in advocacy. The collective efforts could drive substantial improvements in health care delivery and policy, leading to positive changes across the profession.

Review information about a new professional nursing association called the Nurse Advocacy Association.

To become a nursing advocate, identify causes, issues, or needs where YOU can exert influence.

Steps to becoming an advocate include the following[17]:

- Identify a problem that interests you: Start by pinpointing a specific issue or area within nursing that you are passionate about. This could range from patient safety and quality of care to workplace conditions and professional development opportunities.

- Research the subject and select an evidence-based intervention: Conduct thorough research on the identified issue. Look for evidence-based practices and interventions that have been proven to address or mitigate the problem effectively. Gathering robust data will help you build a solid case for your advocacy efforts.

- Network with experts who are, or could be, involved in making the change: Connect with professionals and experts who are either already involved in addressing the issue or who could play a crucial role in implementing changes. Building a network of like-minded individuals can provide support, resources, and additional perspectives.

- Work hard for change: Advocacy requires dedication and persistence. Actively participate in efforts to bring about the desired change. This might include engaging in public speaking, writing articles or blogs, meeting with policymakers, or organizing community events to raise awareness.

Once you have identified a topic of interest, it's crucial to get involved in activities that can amplify your advocacy efforts:

- Committees: Volunteer to participate in committees that review and develop practice policies within your health care institution.

- Professional Nursing Organizations: Become a member of state and national nursing organizations. These groups often provide valuable resources, including access to current legislative and policy initiatives, public policy agendas, and ways to get involved.

- Research and Review: Stay informed by researching best practices and reviewing the health policy agendas of elected officials. Understanding the current landscape will help you identify opportunities to influence policy and practice.

Nurses hold a powerful position to be effective advocates due to their frontline role in health care delivery. Their unique insights into patient care, the work environment, and health care systems make them valuable voices in policy discussions. As the largest sector of the health care workforce, nurses have significant potential to influence decisions at every level.

Advocating for change can lead to improved quality of care, better patient outcomes, and safe work environments. By pushing for evidence-based practices and policies, nurses can help ensure that patients receive the best possible care. Advocacy efforts focused on patient safety and quality can directly impact patient health and recovery. Additionally, nurses can advocate for better working conditions, which can lead to a safer and more supportive environment for all healthcare workers.

Imagine the impact if every nurse actively engaged in advocacy. The collective efforts could drive substantial improvements in health care delivery and policy, leading to positive changes across the profession.

Review information about a new professional nursing association called the Nurse Advocacy Association.

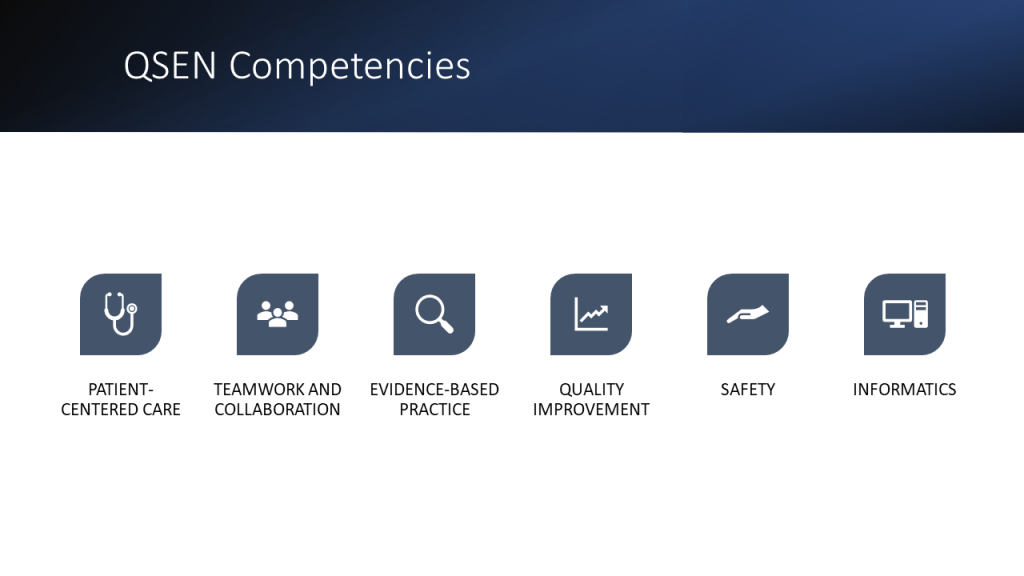

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project began advocating for safe, quality patient care in 2005 by defining six competencies for nursing graduates. This initiative was created after a decade of review and investigation into the high number and high cost of medical errors in the United States. The goal of the QSEN initiative was to prepare future nurses with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to improve the quality and safety of the health care system. Historically, nursing education focused on knowledge and skill acquisition, but did not address the attitudes and values of the nurse. The QSEN competencies are designed to train nursing students in prelicensure nursing programs. The six QSEN competencies, as shown in Figure 10.6,[18] are Patient-Centered Care, Teamwork and Collaboration, Evidence-Based Practice, Quality Improvement, Safety, and Informatics.[19]

Read the QSEN Prelicensure Table of Competencies.

Patient-Centered Care

The Patient-Centered Care QSEN competency advocates for the client as “the source of control and full partner in providing compassionate and coordinated care based on respect for patient’s preferences, values, and needs.”[20] This competency encourages nurses to consider clients’ cultural traditions and personal beliefs while providing compassionate care. Patient-centered care also includes the family in the care team. The goal of patient-centered care is to improve the individual’s health outcomes. Integration of this competency has led to improved patient satisfaction scores, reduced expenses, and a positive care environment.[21]

Teamwork and Collaboration

The Teamwork and Collaboration QSEN competency focuses on functioning effectively within nursing and interprofessional teams and fostering open communication, mutual respect, and shared decision-making to achieve quality patient care.[22] Effective communication has been proven to reduce errors and improve client safety.[23] The Joint Commission also includes improved communication as one of the National Patient Safety Goals, aligning with this QSEN competency. Collaboration requires information sharing across disciplines with respect for the knowledge, skills, and experience of each team member. Two examples of tools used to promote effective teamwork and collaboration are ISBARR and TeamSTEPPS®. Additionally, “principles of collaboration” have been established by the ANA.

ISBARR

Several communication tools have been developed to improve communication in various health care settings. ISBARR is an example of a well-established communication tool. As previously discussed in the "Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team" chapter, ISBARR is a mnemonic for the components to include when communicating with other health care team members: Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[24]

TeamSTEPPS®

As previously discussed in the "Collaboration Within the Interprofessional Team" chapter, TeamSTEPPS® (Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety) is a well-established framework to improve client safety through effective communication in health care environments. It consists of four core competencies: communication, leadership, situation monitoring, and mutual support.

Principles of Collaboration

The American Nurses Association (ANA) and the American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE) jointly created the “Principles of Collaboration” to guide nurses in creating, enhancing, and sustaining collaborative relationships. These principles include effective communication, authentic relationships, and a learning environment and culture. The principle of authentic relationships includes the following guidelines[25]:

- Be true to yourself - be sure your actions match your words and those around you are confident that what they see is what they get.

- Empower others to have ideas, to share those ideas, and to participate in projects that leverage or enact those ideas.

- Recognize and leverage each other’s strengths.

- Be honest 100% of the time - with yourself and with others.

- Respect others’ personalities, needs, and wants.

- Ask for what you want but stay open to negotiating the difference.

- Assume good intent from others’ words and actions, and assume they are doing their best.

Read more about the “Principles of Collaboration” by the ANA and AONE.

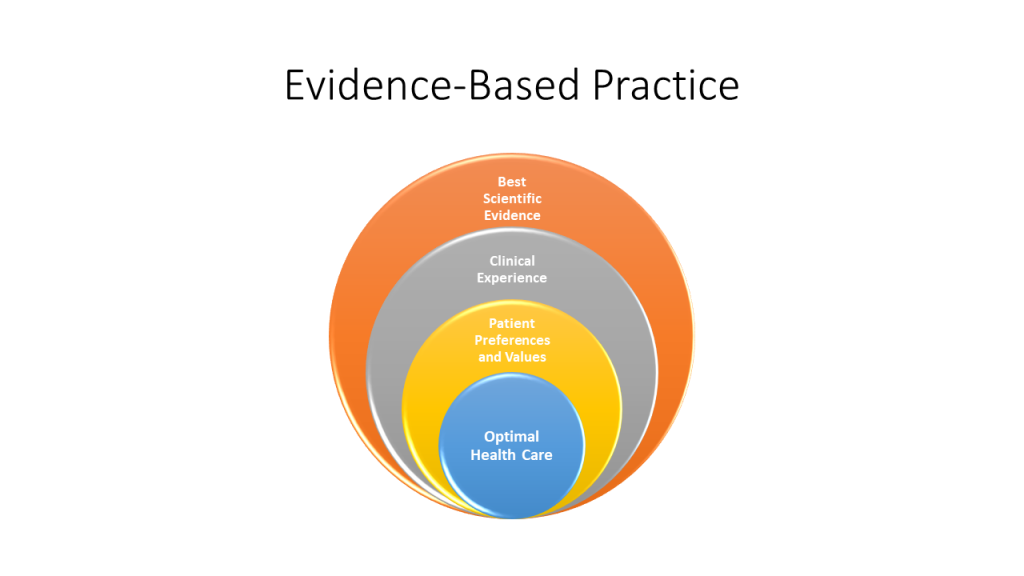

Evidence-Based Practice

The Evidence-Based Practice QSEN competency focuses on integrating scientific evidence with clinical expertise and client/family preferences and values for delivery of optimal health care.[26] See Figure 10.7[27] for an illustration of Evidence-Based Practices (EBP). Read more about EPB in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter. Read examples of evidence-based improvements in the following box.

Read these examples of evidence-based practice improvements:

Quality Improvement

The Quality Improvement QSEN competency focuses on using data to monitor the outcomes of care processes and using improvement methods to design and test changes to continuously improve the quality and safety of health care systems.[28] The goal of this competency is to improve processes, policies, and clinical decisions to improve client outcomes and system performance. As the pool of nursing literature grows and nursing practices have been updated to reflect current evidence, health care organizations have seen improvements in quality, safety, and experienced cost savings.[29]

Read more about the quality improvement processes in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter.

Safety

The Safety QSEN competency focuses on minimizing “risk of harm to patients and providers through both system effectiveness and individual performance.”[30] Although safety is embedded in all of the QSEN competencies, this competency specifically advocates for preventing client harm. Despite the health care industry’s continued focus on process improvement and improving client outcomes, errors continue to occur, and nurses are often involved in these events as frontline caregivers. Safe nursing practice starts with an awareness of the potential risks for client harm in every situation.

Several initiatives have been adopted to reduce risk for client harm, such as double-checking high-risk medications and verifying a patient’s name and date of birth prior to every intervention. However, client safety is compromised when there are gaps in quality measures such as inadequate staff training, broken equipment, or an organizational culture that doesn’t support best practices.

The “Safety” competency is best addressed by organizations establishing a safety culture where every worker commits to keeping client safety at the center of decision-making. An organization that has a culture of safety encourages reporting of unusual incidents, process failures, or other issues that could cause client harm, allowing the organization to investigate the event and take action to prevent the event from occurring in the future. Improvements are made as a result of a culture that questions attitudes, actions, and decisions in client care and recognizes threats to safety. Read more about safety culture in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

Informatics

The Informatics QSEN competency focuses on using information and technology to communicate, manage knowledge, mitigate error, and support decision-making.[31] Health care is filled with various technologies used to promote a safe care environment, such as electronic medical records (EMRs), bedside medication administration devices, smart IV pumps, and medication distribution systems. These technologies provide safeguards and reminders to help prevent client harm, but the nurse must be knowledgeable in using technology, as well as understand how information obtained from technologies is used to improve client patient outcomes. As information related to technology continues to evolve, it is the responsibility of every nurse to participate in continued professional development related to informatics.

Case Study

An 85-year-old woman was admitted with sudden onset of dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and right upper arm edema. She had a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placed three weeks previously for treatment of osteomyelitis of the left hand. A caretaker had been infusing her antibiotics and managing her PICC with the oversight of a home care nurse. A chest computerized tomography scan confirmed the presence of a pulmonary embolism. She was admitted to the inpatient floor at change of shift, and orders were received for a weight-based heparin bolus and infusion. The bolus was administered, and the infusion was initiated. During handoff report to the next shift, the pump alarm sounded. In responding to the alarm, the oncoming nurse discovered that the entire bag of heparin (25,000 units) had infused in less than 30 minutes. She discovered the rate on the pump was set by the previous nurse at 600 mL/hour rather than the weight-adjusted 600 units/hour.

The oncoming nurse who discovered the heparin error immediately disconnected the infusion, assessed the client for signs of bleeding, and notified the physician of the error. Appropriate precautions were initiated and an incident report was submitted. Subsequently, an investigation was conducted by the unit supervisor and the risk manager by interviewing involved staff. They found that the client's admitting nurse, who administered the heparin bolus and infusion, was a traveling nurse who had been in the organization for three weeks and had been floated to the telemetry unit for the first time. While the traveling nurse had been trained on an orthopedic unit, she had not initiated a heparin infusion at this facility. The facility used an infusion pump that included a drug library with medication-specific infusion limits for client safety. The nurse had been trained to use the infusion pump drug library in a brief orientation, but she had witnessed several nurses bypass this safety measure. In addition, although she had her heparin bolus and infusion calculations double-checked by another nurse, she was not aware that this double-check should include a review of pump settings. Finally, because the change of shift handoff report was hurried, it did not include a bedside report to review infusions and client status with the oncoming nurse. What appeared to be a serious individual error was, in fact, a complex series of failures in the facility's safety culture that placed a nurse in the very difficult position of making an error that placed a client at risk of harm. Fortunately, no significant bleeding events occurred as a result of the error.[32]

Reflective Questions

- Create a list of safety failures in this example and categorize them based on the QSEN competencies.

- Outline communication tools and best practices that could have prevented this error from occurring.