Preventing Medication Errors

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Preventing medication errors has been a key target for improving safety since the 1990s. Despite error reduction strategies, implementing new technologies, and streamlining processes, medication errors remain a significant concern with error rates of 8%-25% during medication administration.[1] Furthermore, a substantial proportion of errors occur in hospitalized children due to the complexity of weight-based pediatric dosing.[2]

Several prevention initiatives have been developed to ensure safe medication administration such as the following strategies[3]:

- Routinely checking the rights of medication administration

- Standardizing communication such as “tall man lettering,” alerts to “look alike-sound alike” drug names, avoidance of abbreviations, and standards for expressing numerical dosages

- Focusing on high-alert medications that have a higher likelihood of resulting in patient harm if involved in an administration error, such as anticoagulants, insulins, opioids, and chemotherapy agents

- Standardizing labelling of medication using visual cues as safeguards

- Optimizing nursing workflow to minimize errors, such as minimizing interruptions and double checking high alert medications

- Implementing technology like barcode medication administration and smart infusion pumps

Read the article “Medication Administration Errors” on the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) website.[4]

The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals related to mediation administration were previously discussed in the “Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration” section of this chapter. This section will further discuss additional safety initiatives established by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), World Health Organization (WHO), Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), and Quality and Safe Education for Nurses (QSEN) to prevent medication errors.

Institute of Medicine

To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System Report

The national focus on reducing medical errors has been in place since the 1990s. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a historic report in 1999 titled To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The report stated that errors caused between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths every year in American hospitals and over one million injuries. The IOM report called for a 50% reduction in medical errors over five years. Its goal was to break the cycle of inaction regarding medical errors by advocating for a comprehensive approach to improving patient safety. The IOM 1999 report changed the focus of patient safety from dispensing blame to improving systems.[5]

Preventing Medication Errors Report

In 2007 the IOM published a follow-up report titled Preventing Medication Errors, reporting that more than 1.5 million Americans are injured every year in American hospitals, and the average hospitalized client experiences at least one medication error each day. This report emphasized actions that health care systems, providers, funders, and regulators could take to improve medication safety. These recommendations included actions such as having all U.S. prescriptions written and dispensed electronically, promoting widespread use of medication reconciliation, and performing additional research on drug errors and their prevention. The report also emphasized actions that client can take to prevent medication errors, such as maintaining active medication lists and bringing their medications to appointments for review.[6]

The Preventing Medication Errors report included specific actions for nurses to improve medication safety. The box below summarizes key actions.[7]

Improving Medication Safety: Actions for Nurses

- Establish safe work environments for medication preparation, administration, and documentation; for instance, reduce distractions and provide appropriate lighting.

- Maintain a culture of rigorous commitment to principles of safety in medication administration (for example, consistently checking the rights of medication administration and also performing double checks with colleagues as recommended).

- Remove barriers and facilitate the involvement of client surrogates in checking the administration and monitoring the medication effects.

- Foster a commitment to clients’ rights as co-consumers of their care.

- Develop aids for clients or their surrogates to support self-management of medications.

- Enhance communication skills and team training to be prepared and confident in questioning medication orders and evaluating client responses to drugs.

- Actively advocate for the development, testing, and safe implementation of electronic health records.

- Work to improve systems that address “near misses” in the work environment.

- Realize they are part of a system and do their part to evaluate the efficacy of new safety systems and technology.

- Contribute to the development and implementation of error reporting systems and support a culture that values accurate reporting of medication errors.

World Health Organization: Medication Without Harm

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified “Medication Without Harm” as the theme for the third Global Patient Safety Challenge with the goal of reducing severe, avoidable medication-related harm by 50% over the next five years. As part of the Global Patient Safety Challenge: Medication Without Harm, the WHO has prioritized three areas to protect clients from harm while maximizing the benefit from medication[8]:

- Medication safety in high-risk situations

- Medication safety in polypharmacy

- Medication safety in transitions of care

Read more information about the WHO initiative called Medication Without Harm.

View the follow YouTube video explaining how to avoid harm from medications.

Medication Without Harm[9]

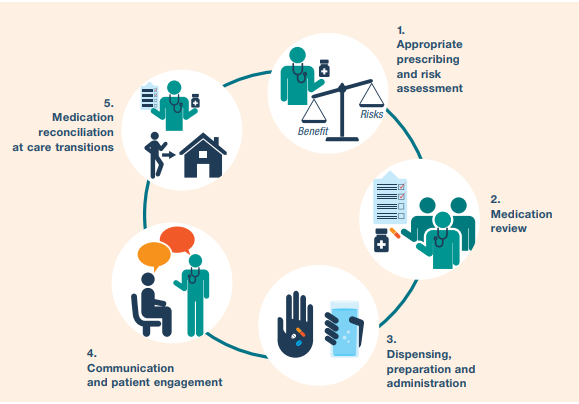

A summary of strategies to reduce harm and ensure medication safety is provided in Figure 2.3.[10]

Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations

The first priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative, medication safety in high-risk situations, includes the components of high-risk medications, provider-client relations, and systems factors.

High-Risk (High-Alert) Medications

High-risk medications are drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant client harm when they are used in error.[11]

High-risk medication can be remembered using the mnemonic “A PINCH.” The information in the box below describes these medications included with the “A PINCH” mnemonic.

High-Risk Medication Group Examples of Medication

A: Anti-infective Amphotericin, aminoglycosides

P: Potassium & other electrolytes Injections of potassium & other electrolytes

I: Insulin All types of insulin

N: Narcotics & other sedatives Opioids, such as morphine; Benzodiazepines

C: Chemotherapeutic agents Methotrexate and vincristine

H: Heparin & anticoagulants Warfarin and enoxaparin

Note: Based on research, the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has expanded this list of high-risk medications. The updated list can be viewed in the box below.

Strategies for safe administration of high-alert medication include the following:

- Standardizing the ordering, storage, preparation, and administration of these products

- Improving access to information about these drugs

- Employing clinical decision support and automated alerts

- Using redundancies such as automated or independent double-checks when necessary

Provider-Patient Relations

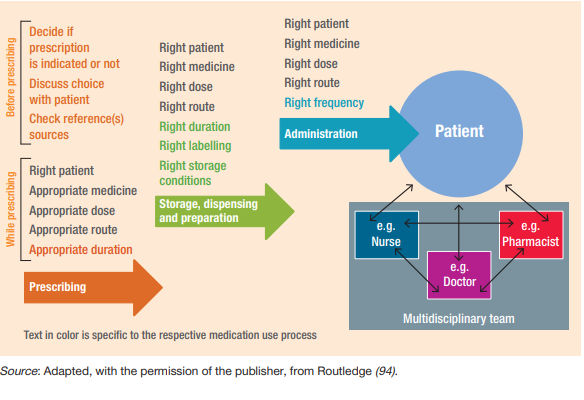

In addition to high-risk medications, a second component of medication safety in high-risk situations includes provider and client factors. This component relates to either the health care professional providing care or the client being treated. Even the most dedicated health care professional is fallible and can make errors. The act of prescribing, dispensing, and administering a medicine is complex and involves several health care professionals. The client should be the center of what should be a “prescribing partnership.”[12] See Figure 2.4 for an illustration of the prescribing partnership.[13]

Life Span Considerations

Other risk factors can exist in specific clients across the life span. For example, adverse drug events occur most often at the extremes of life (in the very young and very old). In the older adult population, frail clients are likely to receive several medications concurrently, which adds to the risk of adverse drug events. In addition, the harm of some of these medication combinations may be synergistic, meaning the risk is greater when medications are taken together than the sum of the risks of individual agents. In neonates (particularly premature neonates), elimination routes through the kidney or liver may not be fully developed. The very young and very old are also less likely to tolerate adverse drug reactions, either because their homeostatic mechanisms are not yet fully developed, or they may have deteriorated. Medication errors in children, where doses may have to be calculated in relation to body weight or age, are also a source of major concern. Additionally, certain medical conditions predispose clients to an increased risk of adverse drug reactions, particularly renal or hepatic dysfunction and cardiac failure. Interprofessional strategies to address these potential harms are based on a systems approach with a “prescribing partnership” between the client, the prescriber, the pharmacist, and the nurse that includes verifying orders when concerns exist.

Systems Factors

In addition to high-risk medications and provider-patient relations, systems factors also contribute to medication safety in high-risk situations. Systems factors can contribute to error-provoking conditions for several reasons. The unit may be busy or understaffed, which can contribute to inadequate supervision or failure to remember to check important information. Interruptions during critical processes (e.g., administration of medicines) can also occur, which can have significant implications for patient safety. Tiredness and the need to multitask when busy or flustered can also contribute to error and can be compounded by poor electronic medical record design. Preparing and administering intravenous medications are also particularly error prone. Strategies for reducing errors include checking at each step of the medication administration process; preventing interruptions; using electronic provider order entry; and utilizing prescribing assessment tools, such as the Beers Criteria, to evaluate for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults.[14] The Beers Criteria is a list of potentially harmful medications or medications with side effects that outweigh the benefit of taking the medication.

Read additional information about the updated Beers Criteria by the American Geriatrics Society.

Medication Safety in Polypharmacy

The second priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative relates to medication safety in polypharmacy. Polypharmacy is the concurrent use of multiple medications. Although there is no standard definition, polypharmacy is often defined as the routine use of five or more medications including over-the-counter, prescription, and complementary medicines.

As people age, they are more likely to suffer from multiple chronic illnesses and take multiple medications. It is essential to use a person-centered approach to ensure their medications are appropriate to gain the most benefits without harm and to ensure the client is part of the decision-making process. Appropriate polypharmacy is present when all medicines are prescribed for the purpose of achieving specific therapeutic objectives that have been agreed with the client; therapeutic objectives are actually being achieved or there is a reasonable chance they will be achieved in the future; medication therapy has been optimized to minimize the risk of adverse drug reactions; and the client is motivated and able to take all medicines as intended.

Inappropriate polypharmacy is present when one or more medications are prescribed that are no longer needed. One or more medications may no longer be needed because there is no evidence-based indication, the indication has expired or the dose is unnecessarily high, they fail to achieve the therapeutic objectives they were intended to achieve, one or the combination of several medications put the client at a high risk of adverse drug reactions, or the client is not willing or able to take the medications as intended.[15]

When clients transition across health care settings, medication review by nurses is essential to prevent harm caused by inappropriate polypharmacy. [16]

Review questions to address during a medication review in Chapter 2 of WHO’s Medication Safety in Polypharmacy Technical Report.[17]

Medication Safety in Transitions of Care

The third priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative relates to medication safety during transitions of care. View the interactive activity below to see how medications are reconciled during transitions of care from admission to discharge in a hospital setting.

Interactive Activity

“Medication Reconciliation Process” by E. Christman for Open RN is licensed under CC BY 4.0

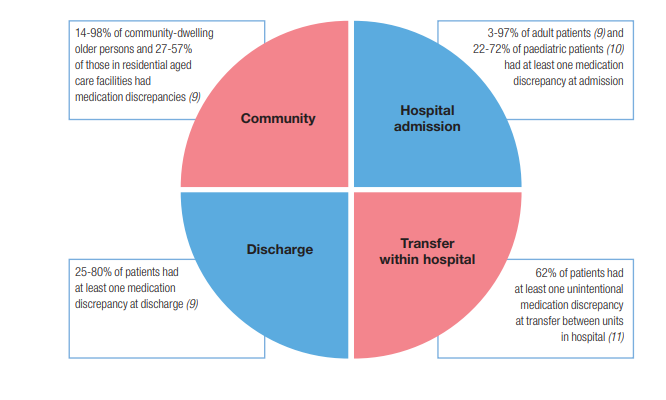

Medication errors can occur during transitions across settings. Figure 2.5[18] is an image from the World Health Organization showing ranges of percentage of errors that occur during common transitions of care.

Key strategies for improving medication safety during transitions of care include the following:

- Implementing formal structured processes for medication reconciliation at all transition points of care. Steps of effective medication reconciliation are to build the best possible medication history by interviewing the client and verifying with at least one reliable information source, reconciling and updating the medication list, and communicating with the client and future health care providers about changes in their medications.

- Partnering with clients, families, caregivers, and health care professionals to agree on treatment plans, ensuring clients are equipped to manage their medications safely, and ensuring clients have an up-to-date medication list.

- Where necessary, prioritizing clients at high risk of medication-related harm for enhanced support such as post-discharge contact by a nurse.[19]

Critical Thinking Activity 2.5a

A nurse is performing medication reconciliation for an elderly client admitted from home. The client does not have a medication list and cannot report the names, dosages, and frequencies of the medication taken at home.

What other sources can the nurse use to obtain medication information?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Institute for Safe Medication Practices

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) is respected as the gold standard for medication safety information. It is a nonprofit organization devoted entirely to preventing medication errors. ISMP collects and analyzes thousands of medication error and adverse event reports each year through its voluntary reporting program and then issues alerts regarding errors happening across the nation. The ISMP has established several prevention strategies for safe medication administration, including lists of high-alert medications, error-prone abbreviations to avoid, do not crush medications, look-alike and sound-alike drugs, and error-prone conditions that lead to error by nurses and student nurses. Each of these initiatives is further described below.[20]

Error-Prone Abbreviations

ISMP’s List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations contains abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations that have been reported through the ISMP National Medication Errors Reporting Program as being frequently misinterpreted and involved in harmful medication errors. These abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations should never be used when communicating medical information. Note that this list has additional abbreviations than those contained in The Joint Commission’s Do Not Use List of Abbreviations. Review the information below for the ISMP list of error-prone abbreviations to avoid. Some examples of abbreviations that were commonly used that should now be avoided are qd, qod, qhs, BID, QID, D/C, subq, and APAP.[21]

Strategies to avoid mistakes related to error-prone abbreviations include not using these abbreviations in medical documentation. Furthermore, if a nurse receives a prescription containing an error-prone abbreviation, it should be clarified with the provider and the order rewritten without the abbreviation.

Download the ISMP List of Error-Prone Abbreviations to Avoid PDF.

Do Not Crush List

The IMSP maintains a list of oral dosage medication that should not be crushed, commonly referred to as the “Do Not Crush” list. These medications are typically extended-release formulations.[22] Strategies for preventing harm related to oral medication that should not be crushed include requesting an order for a liquid form or a different route if the client cannot safely swallow the pill form.

Look-Alike and Sound-Alike (LASA) Drugs

ISMP maintains a list of drug names containing look-alike and sound-alike name pairs such as Adderall and Inderal. These medications require special safeguards to reduce the risk of errors and minimize harm.

Safeguards may include the following:

- Using both the brand and generic names on prescriptions and labels

- Including the purpose of the medication on prescriptions

- Changing the appearance of look-alike product names to draw attention to their dissimilarities

- Configuring computer selection screens to prevent look-alike names from appearing consecutively[23]

Download the ISMP’s List of Confused Drug Names PDF.

Error-Prone Conditions That Lead to Student Nurse Related Error

When analyzing errors involving student nurses reported to the USP-ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program and the PA Patient Safety Reporting System, it appears that many errors arise from a distinct set of error-prone conditions or medications. Some student-related errors are similar in origin to those that seasoned licensed health care professionals make, such as misinterpreting an abbreviation, misidentifying drugs due to look-alike labels and packages, misprogramming a pump due to a pump design flaw, or simply making a mental slip when distracted. Other errors stem from system problems and practice issues that are rather unique to environments where students and hospital staff are caring together for clients. View the list of error-prone conditions that should be avoided using the following box.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.5b

A nurse is preparing to administer insulin to a client. The nurse is aware that insulin is a medication on the ISMP list of high-alert medications.

What strategies should the nurse implement to ensure safe administration of this medication to the client?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project’s vision is to “inspire health care professionals to put quality and safety as core values to guide their work.” QSEN began in 2005 and is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Based on the Institute of Medicine (2003) competencies for nursing, QSEN further defined these quality and safety competencies for educating nursing students:

- Patient-Centered Care

- Teamwork & Collaboration

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Quality Improvement

- Safety

- Informatics[24]

View the QSEN website.

Below are supplementary QSEN learning resources related to patient safety and preventing errors during medication administration.

The Josie King Story and Medical Errors[25]

Summary of Nursing Considerations for Safe and Effective Medication Administration

Medication administration by nurses is not just a task on a daily task list; it is a system-wide process in collaboration with other health care team members to ensure safe and effective treatment. As part of the medication administration process, the nurse must consider ethics, laws, national guidelines, and cultural/social determinants before administering medication to a client. The nurse is the vital “last stop” for preventing errors and potential harm from medications before they reach the client. A list of nursing considerations whenever administering medications is outlined below.

Nursing Considerations for Safe and Effective Medication Administration

BEFORE Administering Medication

Ethics

- Will this medication do more good than harm for this client at this point in time?

- Has the client (or the client’s decision maker) had a voice in the decision-making process regarding use of this medication? Have they been informed about this medication and the potential risks/benefits to consider?

- If there are any ethical concerns, advocate for client rights and autonomy and contact the provider and/or pursue the proper chain of command.

Laws and National Guidelines

- Be sure the prescription/order contains the proper information according to CMS guidelines.

- Are there any FDA Boxed Warnings for this drug? If so, is the client aware of the risks and what to do if they occur? This discussion should be documented.

- Is this a controlled substance? If so, follow guidelines and agency policy for controlled substances in terms of counting, wasting, and disposal. For prescriptions for outpatient use, advocate that Prescription Drug Monitoring Program guidelines are followed.

- Be aware of signs of drug diversion in other health care team members and follow up appropriately in the chain of command. You can also directly submit an online tip to the DEA at Rx Abuse Online Reporting.

- Follow the Joint Commission “SPEAK UP” guidelines if you have any concerns about the safe use of this medication, including, but not limited to:

- Unclear or “do not use” abbreviations

- Strategies for look alike-sound alike medications

- Any other concerns for error

- Follow your state’s practice act regarding Scope of Practice and Rules of Conduct. Is administering this medication appropriate for your scope of practice and for this client? If not, protect your client from harm and your nursing license by notifying the appropriate contacts within your agency.

- Is this medication administration occurring during a transition of care from unit to unit, home to agency, or in preparation for discharge? If so, be sure proper medication reconciliation has been completed.

DURING Administration

- Use the nursing process as you ASSESS if this drug is appropriate to administer at this time and PLAN continued monitoring. Consider life span and disease process implications. If you NOTICE any findings that this medication may not be appropriate at this time for this client, withhold the medication and contact the provider.

- Assess if there are any cultural or social determinants that will impact the client’s ability to use these medications safely and effectively. IMPLEMENT appropriate accommodations as needed and notify the provider.

- Follow The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals as you correctly identify the client and follow guidelines to use medicines safely.

- If this is a high-alert medication, follow recommendations for safe administration (such as adding a second RN check, etc.).

- Reduce distractions in your environment as you prepare and administer medications.

- Do not crush medications unless safe to do so.

- Follow standards set by The Joint Commission and CMS:

- Checking rights of medication administration before administering any medication to a client

- Educate the client about their medication

- Dispose of unused controlled substances appropriately

- Document appropriately

AFTER Administration

- Continue to EVALUATE the client for potential side effects/adverse effects, as well as therapeutic effects of the medications.

- Document and verbally share your findings during handoff reports for safe continuity of care.

- If an error occurs, file an incident report and participate in root cause analysis to determine how to prevent it from happening again.

Media Attributions

- ORN-Icons_internet-copy_internet-copy-300×300

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9728 ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623 ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623 ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Medication without harm. https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm ↵

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017, October 17). WHO: Medication without harm [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/MWUM7LIXDeA ↵

- This image is a derivative of Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325131 page 7, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2018). ISMP List of High-Alert Medications for Acute Care Settings. https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018-08/highAlert2018-Acute-Final.pdf ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This image is a derivative of (2019) Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325131 page 24, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in Polypharmacy by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in Polypharmacy by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Medication Safety in Polypharmacy by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of (2019) Medication Safety in Transition of Care by World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325453/WHO-UHC-SDS-2019.9-eng.pdf?ua=1 page 15, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This image is a derivative of Medication Safety in Transition of Care by World Health Organization licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2007, October 18). Error-prone conditions that lead to student nurse-related errors. https://www.ismp.org/resources/error-prone-conditions-lead-student-nurse-related-errors ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2017, October 2). List of error-prone abbreviations. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/error-prone-abbreviations-list ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2020, February 21). Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/do-not-crush ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2019, February 28). List of confused drug names. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/confused-drug-names-list ↵

- QSEN Institute. (n.d.). Project overview. http://qsen.org/about-qsen/project-overview/ ↵

- Healthcare.gov. (2011, May 25). Introducing the partnerships for patients with Sorrel King [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ak_5X66V5Ms ↵

Accreditation: A review process to determine if an agency meets the defined standards of quality determined by the accrediting body.

ANA Standards of Professional Performance: Authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting are expected to perform competently.

Core measures: National standards of care and treatment processes for common conditions. These processes are proven to reduce complications and lead to better patient outcomes.

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP): A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and patient, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.[1]

Informatics: Using information and technology to communicate, manage knowledge, mitigate error, and support decision-making.[2] This allows members of the health care team to share, store, and analyze health-related information.

Meta-analysis: A type of nursing research (also referred to as a "systematic review") that compares the results of independent research studies asking similar research questions. This research often collects both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a well-rounded evaluation by providing both objective and subjective outcomes.

Nursing informatics: The science and practice integrating nursing, its information and knowledge, with information and communication technologies to promote the health of people, families, and communities worldwide.

Nursing research: The systematic inquiry designed to develop knowledge about issues of importance to the nursing profession.[3] The purpose of nursing research is to advance nursing practice through the discovery of new information. It is also used to provide scholarly evidence regarding improved patient outcomes resulting from nursing interventions.

Patient safety goals: Guidelines specific to organizations accredited by The Joint Commission that focus on problems in health care safety and ways to solve them.

Peer-reviewed: Scholarly journal articles that have been reviewed independently by at least two other academic experts in the same field as the author(s) to ensure accuracy and quality.

Primary source: An original study or report of an experiment or clinical problem. The evidence is typically written and published by the individual(s) conducting the research and includes a literature review, description of the research design, statistical analysis of the data, and discussion regarding the implications of the results.

Qualitative studies: A type of study that provides subjective data, often focusing on the perception or experience of the participants. Data is collected through observations and open-ended questions and often referred to as experimental data. Data is interpreted by developing themes in participants' views and observations.

Quality: The degree to which nursing services for health care consumers, families, groups, communities, and populations increase the likelihood of desirable outcomes and are consistent with evolving nursing knowledge.

Quality Improvement (QI): A systematic process using measurable data to improve health care services and the overall health status of patients. The QI process includes the steps of Plan, Do, Study, and Act.

Quantitative studies: A type of study that provides objective data by using number values to explain outcomes. Researchers can use statistical analysis to determine strength of the findings, as well as identify correlations.

Secondary source: Evidence is written by an author who gathers existing data provided from research completed by another individual. This type of source analyzes and reports on findings from other research projects and may interpret findings or draw conclusions. In nursing research these sources are typically published as a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Utilization review: An investigation by insurance agencies and other health care funders on services performed by doctors, nurses, and other health care team members to ensure money is not wasted covering things that are unnecessary for proper treatment or are inefficient. This review also allows organizations to objectively measure how effectively health care services and resources are being used to best meet their patients’ needs.

Accreditation: A review process to determine if an agency meets the defined standards of quality determined by the accrediting body.

ANA Standards of Professional Performance: Authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting are expected to perform competently.

Core measures: National standards of care and treatment processes for common conditions. These processes are proven to reduce complications and lead to better patient outcomes.

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP): A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and patient, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.[4]

Informatics: Using information and technology to communicate, manage knowledge, mitigate error, and support decision-making.[5] This allows members of the health care team to share, store, and analyze health-related information.

Meta-analysis: A type of nursing research (also referred to as a "systematic review") that compares the results of independent research studies asking similar research questions. This research often collects both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a well-rounded evaluation by providing both objective and subjective outcomes.

Nursing informatics: The science and practice integrating nursing, its information and knowledge, with information and communication technologies to promote the health of people, families, and communities worldwide.

Nursing research: The systematic inquiry designed to develop knowledge about issues of importance to the nursing profession.[6] The purpose of nursing research is to advance nursing practice through the discovery of new information. It is also used to provide scholarly evidence regarding improved patient outcomes resulting from nursing interventions.

Patient safety goals: Guidelines specific to organizations accredited by The Joint Commission that focus on problems in health care safety and ways to solve them.

Peer-reviewed: Scholarly journal articles that have been reviewed independently by at least two other academic experts in the same field as the author(s) to ensure accuracy and quality.

Primary source: An original study or report of an experiment or clinical problem. The evidence is typically written and published by the individual(s) conducting the research and includes a literature review, description of the research design, statistical analysis of the data, and discussion regarding the implications of the results.

Qualitative studies: A type of study that provides subjective data, often focusing on the perception or experience of the participants. Data is collected through observations and open-ended questions and often referred to as experimental data. Data is interpreted by developing themes in participants' views and observations.

Quality: The degree to which nursing services for health care consumers, families, groups, communities, and populations increase the likelihood of desirable outcomes and are consistent with evolving nursing knowledge.

Quality Improvement (QI): A systematic process using measurable data to improve health care services and the overall health status of patients. The QI process includes the steps of Plan, Do, Study, and Act.

Quantitative studies: A type of study that provides objective data by using number values to explain outcomes. Researchers can use statistical analysis to determine strength of the findings, as well as identify correlations.

Secondary source: Evidence is written by an author who gathers existing data provided from research completed by another individual. This type of source analyzes and reports on findings from other research projects and may interpret findings or draw conclusions. In nursing research these sources are typically published as a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Utilization review: An investigation by insurance agencies and other health care funders on services performed by doctors, nurses, and other health care team members to ensure money is not wasted covering things that are unnecessary for proper treatment or are inefficient. This review also allows organizations to objectively measure how effectively health care services and resources are being used to best meet their patients’ needs.