5. Tools for Prioritizing

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) and Amy Ertwine

Prioritization of care for multiple patients while also performing daily nursing tasks can feel overwhelming in today’s fast-paced health care system. Because of the rapid and ever-changing conditions of patients and the structure of one’s workday, nurses must use organizational frameworks to prioritize actions and interventions. These frameworks can help ease anxiety, enhance personal organization and confidence, and ensure patient safety.

Acuity

Acuity and intensity are foundational concepts for prioritizing nursing care and interventions. Acuity refers to the level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. For example, acuity may include characteristics such as unstable vital signs, oxygenation therapy, high-risk IV medications, multiple drainage devices, or uncontrolled pain. A “high-acuity” patient requires several nursing interventions and frequent nursing assessments.

Intensity addresses the time needed to complete nursing care and interventions such as providing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), performing wound care, or administering several medication passes. For example, a “high-intensity” patient generally requires frequent or long periods of psychosocial, educational, or hygiene care from nursing staff members. High-intensity patients may also have increased needs for safety monitoring, familial support, or other needs.[1]

Many health care organizations structure their staffing assignments based on acuity and intensity ratings to help provide equity in staff assignments. Acuity helps to ensure that nursing care is strategically divided among nursing staff. An equitable assignment of patients benefits both the nurse and patient by helping to ensure that patient care needs do not overwhelm individual staff and safe care is provided.

Organizations use a variety of systems when determining patient acuity with rating scales based on nursing care delivery, patient stability, and care needs. See an example of a patient acuity tool published in the American Nurse in Table 2.3.[2] In this example, ratings range from 1 to 4, with a rating of 1 indicating a relatively stable patient requiring minimal individualized nursing care and intervention. A rating of 2 reflects a patient with a moderate risk who may require more frequent intervention or assessment. A rating of 3 is attributed to a complex patient who requires frequent intervention and assessment. This patient might also be a new admission or someone who is confused and requires more direct observation. A rating of 4 reflects a high-risk patient. For example, this individual may be experiencing frequent changes in vital signs, may require complex interventions such as the administration of blood transfusions, or may be experiencing significant uncontrolled pain. An individual with a rating of 4 requires more direct nursing care and intervention than a patient with a rating of 1 or 2.[3]

Table 2.3. Example of a Patient Acuity Tool[4]

| 1: Stable Patient | 2: Moderate-Risk Patient | 3: Complex Patient | 4: High-Risk Patient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

|

|

| Cardiac |

|

|

|

|

| Medications |

|

|

|

|

| Drainage Devices |

|

|

|

|

| Pain Management |

|

|

|

|

| Admit/Transfer/Discharge |

|

|

|

|

| ADLs and Isolation |

|

|

|

|

| Patient Score | Most = 1 | Two or > = 2 | Any = 3 | Any = 4 |

Read more about using a patient acuity tool on a medical-surgical unit.

Rating scales may vary among institutions, but the principles of the rating system remain the same. Organizations include various patient care elements when constructing their staffing plans for each unit. Read more information about staffing models and acuity in the following box.

Staffing Models and Acuity

Organizations that base staffing on acuity systems attempt to evenly staff patient assignments according to their acuity ratings. This means that when comparing patient assignments across nurses on a unit, similar acuity team scores should be seen with the goal of achieving equitable and safe division of workload across the nursing team. For example, one nurse should not have a total acuity score of 6 for their patient assignments while another nurse has a score of 15. If this situation occurred, the variation in scoring reflects a discrepancy in workload balance and would likely be perceived by nursing peers as unfair. Using acuity-rating staffing models is helpful to reflect the individualized nursing care required by different patients.

Alternatively, nurse staffing models may be determined by staffing ratio. Ratio-based staffing models are more straightforward in nature, where each nurse is assigned care for a set number of patients during their shift. Ratio-based staffing models may be useful for administrators creating budget requests based on the number of staff required for patient care, but can lead to an inequitable division of work across the nursing team when patient acuity is not considered. Increasingly complex patients require more time and interventions than others, so a blend of both ratio and acuity-based staffing is helpful when determining staffing assignments.[5]

As a practicing nurse, you will be oriented to the elements of acuity ratings within your health care organization, but it is also important to understand how you can use these acuity ratings for your own prioritization and task delineation. Let’s consider the Scenario B in the following box to better understand how acuity ratings can be useful for prioritizing nursing care.

Scenario B

You report to work at 6 a.m. for your nursing shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. Prior to receiving the handoff report from your night shift nursing colleagues, you review the unit staffing grid and see that you have been assigned to four patients to start your day. The patients have the following acuity ratings:

Patient A: 45-year-old patient with paraplegia admitted for an infected sacral wound, with an acuity rating of 4.

Patient B: 87-year-old patient with pneumonia with a low-grade fever of 99.7 F and receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute via nasal cannula, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient C: 63-year-old patient who is postoperative Day 1 from a right total hip replacement and is receiving pain management via a PCA pump, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient D: 83-year-old patient admitted with a UTI who is finishing an IV antibiotic cycle and will be discharged home today, with an acuity rating of 1.

Based on the acuity rating system, your patient assignment load receives an overall acuity score of 9. Consider how you might use their acuity ratings to help you prioritize your care. Based on what is known about the patients related to their acuity rating, whom might you identify as your care priority? Although this can feel like a challenging question to answer because of the many unknown elements in the situation using acuity numbers alone, Patient A with an acuity rating of 4 would be identified as the care priority requiring assessment early in your shift.

Although acuity can a useful tool for determining care priorities, it is important to recognize the limitations of this tool and consider how other patient needs impact prioritization.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

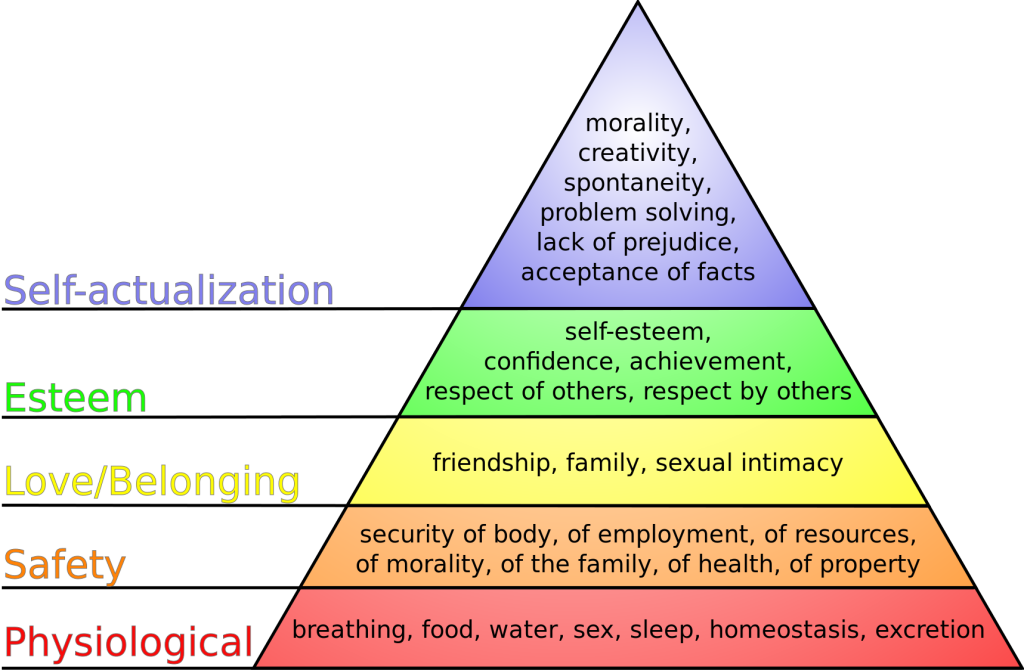

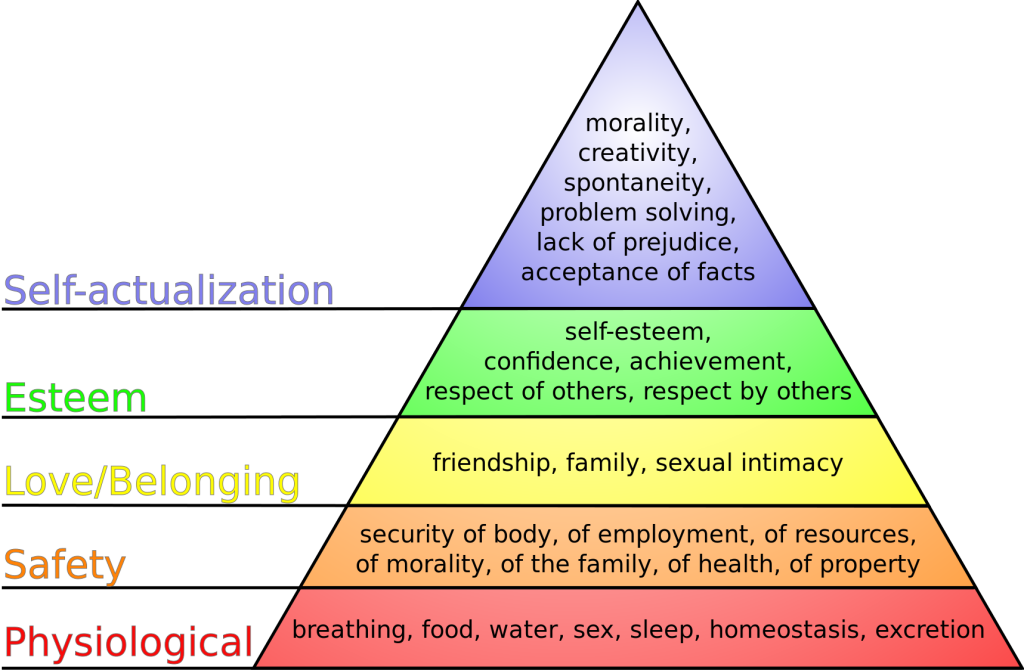

When thinking back to your first nursing or psychology course, you may recall a historical theory of human motivation based on various levels of human needs called Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs reflects foundational human needs with progressive steps moving towards higher levels of achievement. This hierarchy of needs is traditionally represented as a pyramid with the base of the pyramid serving as essential needs that must be addressed before one can progress to another area of need.[6] See Figure 2.1[7] for an illustration of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs places physiological needs as the foundational base of the pyramid.[8] Physiological needs include oxygen, food, water, sex, sleep, homeostasis, and excretion. The second level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects safety needs. Safety needs include elements that keep individuals safe from harm. Examples of safety needs in health care include fall precautions. The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects emotional needs such as love and a sense of belonging. These needs are often reflected in an individual’s relationships with family members and friends. The top two levels of Maslow’s hierarchy include esteem and self-actualization. An example of addressing these needs in a health care setting is helping an individual build self-confidence in performing blood glucose checks that leads to improved self-management of their diabetes.

So how does Maslow’s theory impact prioritization? To better understand the application of Maslow’s theory to prioritization, consider Scenario C in the following box.

Scenario C

You are an emergency response nurse working at a local shelter in a community that has suffered a devastating hurricane. Many individuals have relocated to the shelter for safety in the aftermath of the hurricane. Much of the community is still without electricity and clean water, and many homes have been destroyed. You approach a young woman who has a laceration on her scalp that is bleeding through her gauze dressing. The woman is weeping as she describes the loss of her home stating, “I have lost everything! I just don’t know what I am going to do now. It has been a day since I have had water or anything to drink. I don’t know where my sister is, and I can’t reach any of my family to find out if they are okay!”

Despite this relatively brief interaction, this woman has shared with you a variety of needs. She has demonstrated a need for food, water, shelter, homeostasis, and family. As the nurse caring for her, it might be challenging to think about where to begin her care. These thoughts could be racing through your mind:

Should I begin to make phone calls to try and find her family? Maybe then she would be able to calm down.

Should I get her on the list for the homeless shelter so she wouldn’t have to worry about where she will sleep tonight?

She hasn’t eaten in a while; I should probably find her something to eat.

All these needs are important and should be addressed at some point, but Maslow’s hierarchy provides guidance on what needs must be addressed first. Use the foundational level of Maslow’s pyramid of physiological needs as the top priority for care. The woman is bleeding heavily from a head wound and has had limited fluid intake. As the nurse caring for this patient, it is important to immediately intervene to stop the bleeding and restore fluid volume. Stabilizing the patient by addressing her physiological needs is required before undertaking additional measures such as contacting her family. Imagine if instead you made phone calls to find the patient’s family and didn’t address the bleeding or dehydration – you might return to a severely hypovolemic patient who has deteriorated and may be near death. In this example, prioritizing emotional needs above physiological needs can lead to significant harm to the patient.

Although this is a relatively straightforward example, the principles behind the application of Maslow’s hierarchy are essential. Addressing physiological needs before progressing toward additional need categories concentrates efforts on the most vital elements to enhance patient well-being. Maslow’s hierarchy provides the nurse with a helpful framework for identifying and prioritizing critical patient care needs.

ABCs

Airway, breathing, and circulation, otherwise known by the mnemonic “ABCs,” are another foundational element to assist the nurse in prioritization. Like Maslow’s hierarchy, using the ABCs to guide decision-making concentrates on the most critical needs for preserving human life. If a patient does not have a patent airway, is unable to breathe, or has inadequate circulation, very little of what else we do matters. The patient’s ABCs are reflected in Maslow’s foundational level of physiological needs and direct critical nursing actions and timely interventions. Let’s consider Scenario D in the following box regarding prioritization using the ABCs and the physiological base of Maslow’s hierarchy.

Scenario D

You are a nurse on a busy cardiac floor charting your morning assessments on a computer at the nurses’ station. Down the hall from where you are charting, two of your assigned patients are resting comfortably in Room 504 and Room 506. Suddenly, both call lights ring from the rooms, and you answer them via the intercom at the nurses’ station.

Room 504 has an 87-year-old male who has been admitted with heart failure, weakness, and confusion. He has a bed alarm for safety and has been ringing his call bell for assistance appropriately throughout the shift. He requires assistance to get out of bed to use the bathroom. He received his morning medications, which included a diuretic about 30 minutes previously, and now reports significant urge to void and needs assistance to the bathroom.

Room 506 has a 47-year-old woman who was hospitalized with new onset atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. The patient underwent a cardioversion procedure yesterday that resulted in successful conversion of her heart back into normal sinus rhythm. She is reporting via the intercom that her “heart feels like it is doing that fluttering thing again” and she is having chest pain with breathlessness.

Based upon these two patient scenarios, it might be difficult to determine whom you should see first. Both patients are demonstrating needs in the foundational physiological level of Maslow’s hierarchy and require assistance. To prioritize between these patients’ physiological needs, the nurse can apply the principles of the ABCs to determine intervention. The patient in Room 506 reports both breathing and circulation issues, warning indicators that action is needed immediately. Although the patient in Room 504 also has an urgent physiological elimination need, it does not overtake the critical one experienced by the patient in Room 506. The nurse should immediately assess the patient in Room 506 while also calling for assistance from a team member to assist the patient in Room 504.

CURE

Prioritizing what should be done and when it can be done can be a challenging task when several patients all have physiological needs. Recently, there has been professional acknowledgement of the cognitive challenge for novice nurses in differentiating physiological needs. To expand on the principles of prioritizing using the ABCs, the CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras.[9]

“Critical” patient needs require immediate action. Examples of critical needs align with the ABCs and Maslow’s physiological needs, such as symptoms of respiratory distress, chest pain, and airway compromise. No matter the complexity of their shift, nurses can be assured that addressing patients’ critical needs is the correct prioritization of their time and energies.

After critical patient care needs have been addressed, nurses can then address “urgent” needs. Urgent needs are characterized as needs that cause patient discomfort or place the patient at a significant safety risk.[10]

The third part of the CURE hierarchy reflects “routine” patient needs. Routine patient needs can also be characterized as “typical daily nursing care” because the majority of a standard nursing shift is spent addressing routine patient needs. Examples of routine daily nursing care include actions such as administering medication and performing physical assessments.[11] Although a nurse’s typical shift in a hospital setting includes these routine patient needs, they do not supersede critical or urgent patient needs.

The final component of the CURE hierarchy is known as “extras.” Extras refer to activities performed in the care setting to facilitate patient comfort but are not essential.[12] Examples of extra activities include providing a massage for comfort or washing a patient’s hair. If a nurse has sufficient time to perform extra activities, they contribute to a patient’s feeling of satisfaction regarding their care, but these activities are not essential to achieve patient outcomes.

Let’s apply the CURE mnemonic to patient care in the following box.

If we return to Scenario D regarding patients in Room 504 and 506, we can see the patient in Room 504 is having urgent needs. He is experiencing a physiological need to urgently use the restroom and may also have safety concerns if he does not receive assistance and attempts to get up on his own because of weakness. He is on a bed alarm, which reflects safety considerations related to his potential to get out of bed without assistance. Despite these urgent indicators, the patient in Room 506 is experiencing a critical need and takes priority. Recall that critical needs require immediate nursing action to prevent patient deterioration. The patient in Room 506 with a rapid, fluttering heartbeat and shortness of breath has a critical need because without prompt assessment and intervention, their condition could rapidly decline and become fatal.

Data Cues

In addition to using the identified frameworks and tools to assist with priority setting, nurses must also look at their patients’ data cues to help them identify care priorities. Data cues are pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition. For example, have the patient’s vital signs worsened over the last few hours? Is there a new laboratory result that is concerning? Data cues are used in conjunction with prioritization frameworks to help the nurse holistically understand the patient’s current status and where nursing interventions should be directed. Common categories of data clues include acute versus chronic conditions, actual versus potential problems, unexpected versus expected conditions, information obtained from the review of a patient’s chart, and diagnostic information.

Acute Versus Chronic Conditions

A common data cue that nurses use to prioritize care is considering if a condition or symptom is acute or chronic. Acute conditions have a sudden and severe onset. These conditions occur due to a sudden illness or injury, and the body often has a significant response as it attempts to adapt. Chronic conditions have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time. The difference between an acute versus a chronic condition relates to the body’s adaptation response. Individuals with chronic conditions often experience less symptom exacerbation because their body has had time to adjust to the illness or injury. Let’s consider an example of two patients admitted to the medical-surgical unit complaining of pain in Scenario E in the following box.

Scenario E

As part of your patient assignment on a medical-surgical unit, you are caring for two patients who both ring the call light and report pain at the start of the shift. Patient A was recently admitted with acute appendicitis, and Patient B was admitted for observation due to weakness. Not knowing any additional details about the patients’ conditions or current symptoms, which patient would receive priority in your assessment? Based on using the data cue of acute versus chronic conditions, Patient A with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis would receive top priority for assessment over a patient with chronic pain due to osteoarthritis. Patients experiencing acute pain require immediate nursing assessment and intervention because it can indicate a change in condition. Acute pain also elicits physiological effects related to the stress response, such as elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate, and should be addressed quickly.

Actual Versus Potential Problems

Nursing diagnoses and the nursing care plan have significant roles in directing prioritization when interpreting assessment data cues. Actual problems refer to a clinical problem that is actively occurring with the patient. A risk problem indicates the patient may potentially experience a problem but they do not have current signs or symptoms of the problem actively occurring.

Consider an example of prioritizing actual and potential problems in Scenario F in the following box.

Scenario F

A 74-year-old woman with a previous history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is admitted to the hospital for pneumonia. She has generalized weakness, a weak cough, and crackles in the bases of her lungs. She is receiving IV antibiotics, fluids, and oxygen therapy. The patient can sit at the side of the bed and ambulate with the assistance of staff, although she requires significant encouragement to ambulate.

Nursing diagnoses are established for this patient as part of the care planning process. One nursing diagnosis for this patient is Ineffective Airway Clearance. This nursing diagnosis is an actual problem because the patient is currently exhibiting signs of poor airway clearance with an ineffective cough and crackles in the lungs. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include coughing and deep breathing, administering nebulizer treatment, and evaluating the effectiveness of oxygen therapy. The patient also has the nursing diagnosis Risk for Skin Breakdown based on her weakness and lack of motivation to ambulate. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include repositioning every two hours and assisting with ambulation twice daily.

The established nursing diagnoses provide cues for prioritizing care. For example, if the nurse enters the patient’s room and discovers the patient is experiencing increased shortness of breath, nursing interventions to improve the patient’s respiratory status receive top priority before attempting to get the patient to ambulate.

Although there may be times when risk problems may supersede actual problems, looking to the “actual” nursing problems can provide clues to assist with prioritization.

Unexpected Versus Expected Conditions

In a similar manner to using acute versus chronic conditions as a cue for prioritization, it is also important to consider if a client’s signs and symptoms are “expected” or “unexpected” based on their overall condition. Unexpected conditions are findings that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury. Expected conditions are findings that are likely to occur or are anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury. Unexpected findings often require immediate action by the nurse.

Let’s apply this tool to the two patients previously discussed in Scenario E. As you recall, both Patient A (with acute appendicitis) and Patient B (with weakness and diagnosed with osteoarthritis) are reporting pain. Acute pain typically receives priority over chronic pain. But what if both patients are also reporting nausea and have an elevated temperature? Although these symptoms must be addressed in both patients, they are “expected” symptoms with acute appendicitis (and typically addressed in the treatment plan) but are “unexpected” for the patient with osteoarthritis. Critical thinking alerts you to the unexpected nature of these symptoms in Patient B, so they receive priority for assessment and nursing interventions.

Handoff Report/Chart Review

Additional data cues that are helpful in guiding prioritization come from information obtained during a handoff nursing report and review of the patient chart. These data cues can be used to establish a patient’s baseline status and prioritize new clinical concerns based on abnormal assessment findings. Let’s consider Scenario G in the following box based on cues from a handoff report and how it might be used to help prioritize nursing care.

Scenario G

Imagine you are receiving the following handoff report from the night shift nurse for a patient admitted to the medical-surgical unit with pneumonia:

At the beginning of my shift, the patient was on room air with an oxygen saturation of 93%. She had slight crackles in both bases of her posterior lungs. At 0530, the patient rang the call light to go to the bathroom. As I escorted her to the bathroom, she appeared slightly short of breath. Upon returning the patient to bed, I rechecked her vital signs and found her oxygen saturation at 88% on room air and respiratory rate of 20. I listened to her lung sounds and noticed more persistent crackles and coarseness than at bedtime. I placed the patient on 2 L/minute of oxygen via nasal cannula. Within five minutes, her oxygen saturation increased to 92%, and she reported increased ease in respiration.

Based on the handoff report, the night shift nurse provided substantial clinical evidence that the patient may be experiencing a change in condition. Although these changes could be attributed to lack of lung expansion that occurred while the patient was sleeping, there is enough information to indicate to the oncoming nurse that follow-up assessment and interventions should be prioritized for this patient because of potentially worsening respiratory status. In this manner, identifying data cues from a handoff report can assist with prioritization.

Now imagine the night shift nurse had not reported this information during the handoff report. Is there another method for identifying potential changes in patient condition? Many nurses develop a habit of reviewing their patients’ charts at the start of every shift to identify trends and “baselines” in patient condition. For example, a chart review reveals a patient’s heart rate on admission was 105 beats per minute. If the patient continues to have a heart rate in the low 100s, the nurse is not likely to be concerned if today’s vital signs reveal a heart rate in the low 100s. Conversely, if a patient’s heart rate on admission was in the 60s and has remained in the 60s throughout their hospitalization, but it is now in the 100s, this finding is an important cue requiring prioritized assessment and intervention.

Diagnostic Information

Diagnostic results are also important when prioritizing care. In fact, the National Patient Safety Goals from The Joint Commission include prompt reporting of important test results. New abnormal laboratory results are typically flagged in a patient’s chart or are reported directly by phone to the nurse by the laboratory as they become available. Newly reported abnormal results, such as elevated blood levels or changes on a chest X-ray, may indicate a patient’s change in condition and require additional interventions. For example, consider Scenario H in which you are the nurse providing care for five medical-surgical patients.

Scenario H

You completed morning assessments on your assigned five patients. Patient A previously underwent a total right knee replacement and will be discharged home today. You are about to enter Patient A’s room to begin discharge teaching when you receive a phone call from the laboratory department, reporting a critical hemoglobin of 6.9 gm/dL on Patient B. Rather than enter Patient A’s room to perform discharge teaching, you immediately reprioritize your care. You call the primary provider to report Patient B’s critical hemoglobin level and determine if additional intervention, such as a blood transfusion, is required.

Prioritization Principles & Staffing Considerations[13]

With the complexity of different staffing variables in health care settings, it can be challenging to identify a method and solution that will offer a resolution to every challenge. The American Nurses Association has identified five critical principles that should be considered for nurse staffing. These principles are as follows:

- Health Care Consumer: Nurse staffing decisions are influenced by the specific number and needs of the health care consumer. The health care consumer includes not only the client, but also families, groups, and populations served. Staffing guidelines must always consider the patient safety indicators, clinical, and operational outcomes that are specific to a practice setting. What is appropriate for the consumer in one setting, may be quite different in another. Additionally, it is important to ensure that there is resource allocation for care coordination and health education in each setting.

- Interprofessional Teams: As organizations identify what constitutes appropriate staffing in various settings, they must also consider the appropriate credentials and qualifications of the nursing staff within a specific setting. This involves utilizing an interprofessional care team that allows each individual to practice to the full extent of their educational, training, scope of practice as defined by their state Nurse Practice Act, and licensure. Staffing plans must include an appropriate skill mix and acknowledge the impact of more experienced nurses to help serve in mentoring and precepting roles.

- Workplace culture: Staffing considerations must also account for the importance of balance between costs associated with best practice and the optimization of care outcomes. Health care leaders and organizations must strive to ensure a balance between quality, safety, and health care cost. Organizations are responsible for creating work environments, which develop policies allowing for nurses to practice to the full extent of their licensure in accordance with their documented competence. Leaders must foster a culture of trust, collaboration, and respect among all members of the health care team, which will create environments that engage and retain health care staff.

- Practice environment: Staffing structures must be founded in a culture of safety where appropriate staffing is integral to achieve patient safety and quality goals. An optimal practice environment encourages nurses to report unsafe conditions or poor staffing that may impact safe care. Organizations should ensure that nurses have autonomy in reporting and concerns and may do so without threat of retaliation. The ANA has also taken the position to state that mandatory overtime is an unacceptable solution to achieve appropriate staffing. Organizations must ensure that they have clear policies delineating length of shifts, meal breaks, and rest period to help ensure safety in patient care.

- Evaluation: Staffing plans should be consistently evaluated and changed based upon evidence and client outcomes. Environmental factors and issues such as work-related illness, injury, and turnover are important elements of determining the success of need for modification within a staffing plan.[14]

Media Attributions

- Maslow’s_hierarchy_of_needs.svg

- Oregon Health Authority. (2021, April 29). Hospital nurse staffing interpretive guidance on staffing for acuity & intensity. Public Health Division, Center for Health Protection. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/providerpartnerresources/healthcareprovidersfacilities/healthcarehealthcareregulationqualityimprovement/pages/nursestaffing.aspx ↵

- Ingram, A., & Powell, J. (2018). Patient acuity tool on a medical surgical unit. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/patient-acuity-medical-surgical-unit/ ↵

- Kidd, M., Grove, K., Kaiser, M., Swoboda, B., & Taylor, A. (2014). A new patient-acuity tool promotes equitable nurse-patient assignments. American Nurse Today, 9(3), 1-4. https://www.myamericannurse.com/a-new-patient-acuity-tool-promotes-equitable-nurse-patient-assignments/ ↵

- Ingram, A., & Powell, J. (2018). Patient acuity tool on a medical surgical unit. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/patient-acuity-medical-surgical-unit/ ↵

- Welton, J. M. (2017). Measuring patient acuity. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 47(10), 471. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000516 ↵

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346 ↵

- “Maslow's_hierarchy_of_needs.svg” by J. Finkelstein is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Stoyanov, S. (2017). An analysis of Abraham Maslow's A Theory of Human Motivation (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781912282517 ↵

- Kohtz, C., Gowda, C., & Guede, P. (2017). Cognitive stacking: Strategies for the busy RN. Nursing2021, 47(1), 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000510758.31326.92 ↵

- Kohtz, C., Gowda, C., & Guede, P. (2017). Cognitive stacking: Strategies for the busy RN. Nursing2021, 47(1), 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000510758.31326.92 ↵

- Kohtz, C., Gowda, C., & Guede, P. (2017). Cognitive stacking: Strategies for the busy RN. Nursing2021, 47(1), 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000510758.31326.92 ↵

- Kohtz, C., Gowda, C., & Guede, P. (2017). Cognitive stacking: Strategies for the busy RN. Nursing2021, 47(1), 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000510758.31326.92 ↵

- ANA. (2024). Principles for nurse staffing. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nurse-staffing/staffing-principles/ ↵

- ANA. (2024). Principles for nurse staffing. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nurse-staffing/staffing-principles/ ↵

Using Technology to Access Information

Most client information in acute care, long-term care, and other clinical settings is now electronic and uses intranet technology for secure access by providers, nurses, and other health care team members to maintain client confidentiality. Intranet refers to a private computer network within an institution. An electronic health record (EHR) is a real-time, client-centered record that makes information available instantly and securely to authorized users.[1] Computers used to access an EHR can be found in client rooms, on wheeled carts, in workstations, or even on handheld devices. See Figure 2.11[2] for an image of a nurse documenting in an EHR.

The EHR for each client contains a great deal of information. The most frequent pieces of information that nurses access include the following:

- History and Physical (H&P): A history and physical (H&P) is a specific type of documentation created by the health care provider when the client is admitted to the facility. An H&P includes important information about the client’s current status, medical history, and the treatment plan in a concise format that is helpful for the nurse to review. Information typically includes the reason for admission, health history, surgical history, allergies, current medications, physical examination findings, medical diagnoses, and the treatment plan.

- Provider orders: This section includes the prescriptions, or medical orders, that the nurse must legally implement or appropriately communicate according to agency policy if not implemented.

- Medication Administration Records (MARs): Medications are charted through electronic medication administration records (MARs). These records interface the medication orders from providers with pharmacists and are also the location where nurses document medications administered.

- Treatment Administration Records (TARs): In many facilities, treatments such as wound care are documented on a treatment administration record.

- Laboratory results: This section includes results from blood work and other tests performed in the lab.

- Diagnostic test results: This section includes results from diagnostic tests ordered by the provider such as X-rays, ultrasounds, etc.

- Progress notes: This section contains notes created by nurses and other health care providers regarding clientcare. It is helpful for the nurse to review daily progress notes by all team members to ensure continuity of care.

View a video of how to read a client's chart.[3]

Legal Documentation

Nurses and health care team members are legally required to document care provided to clients. Any type of documentation in the EHR is considered a legal document. In a court of law, it is generally viewed that, “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Other documentation guidelines include the following:

- Documentation should be objective, factual, and professional. Only document what you personally assessed, observed, or performed.

- Proper medical terminology, grammar, and spelling should be used.

- All types of documentation must include the date, time, and signature of the person documenting.

- Abbreviations should be avoided in legal documentation.

- Documentation must be completed in an accurate and timely manner after the task is performed. Do not document in advance of completing a task.

- Assessments, interventions, medications, or treatments that were not completed should never be charted as completed. This is considered falsification and can present serious legal ramifications for the nurse and the health care facility.

- When using paper documentation, avoid leaving blank lines to prevent others from adding to your documentation. In the event of a charting error, draw a single line through the error and write, "mistaken entry" above the line with your initials. Errors should never be erased, scribbled out, or covered with white-out.

- If electronic documentation is charted in error, it should be corrected with the details of the error and the correction noted in the background should the need arise to review the documentation.

Documentation is used for many purposes. It is used to ensure continuity of care across health care team members and across shifts; monitor standards of care for quality assurance activities; and provide information for reimbursement purposes by insurance companies, Medicare, and Medicaid. Documentation may also be used for research purposes or, in some instances, for legal concerns in a court of law.

Documentation by nurses includes recording client assessments, writing progress notes, and creating or addressing information included in nursing care plans. Nursing care plans are further discussed in the "Planning" section of the “Nursing Process” chapter.

Common Types of Documentation

Common formats used to document client care include charting by exception, focused DAR notes, narrative notes, SOAPIE progress notes, client discharge summaries, and Minimum Data Set (MDS) charting.

Charting by Exception

Charting by exception (CBE) documentation was designed to decrease the amount of time required to document care. CBE contains a list of normal findings. After performing an assessment, nurses confirm normal findings on the list found on assessment and write only brief progress notes for abnormal findings or to document communication with other team members.

Focused DAR Notes

Focused DAR notes are a type of progress note that are commonly used in combination with charting by exception documentation. DAR stands for Data, Action, and Response. Focused DAR notes are brief. Each note is focused on one client problem for efficiency in documenting and reading.

- Data: This section contains information collected during the client assessment, including vital signs and physical examination findings found during the “Assessment” phase of the nursing process. The Assessment phase is further discussed in the “Nursing Process” chapter. Think of the "Data" section as describing the main problem.

- Action: This section contains the nursing actions that are planned and implemented for the client’s focused problem. This section correlates to the “Planning” and “Implementation” phases of the nursing process and are further discussed in the “Nursing Process” chapter. Think of the "Action" section as describing what was done about the problem.

- Response: This section contains information about the client’s response to the nursing actions and evaluates if the planned care was effective. This section correlates to the “Evaluation” phase of the nursing process that is further discussed in the “Nursing Process” chapter. Think of the "Response" section as describing the result of what happened after performing the actions.

Sample DAR Note

Refer back to the "ISBARR" example provided in a box in Chapter 2.4. The nurse would document the associated provider notification in the EHR using a DAR note:

D: Client reports increasing pain at the incisional site, rated as 7/10, increased from 4/10 despite receiving oral Vicodin 5/325 at 1030. Vital Signs: BP 160/95, HR 90, RR 22, O2 sat 96%, and temperature 38 degrees C. There is 4 cm of redness surrounding the incision that is warm and tender to touch with moderate serosanguinous drainage. Lung sounds are clear, and HR is regular.

A: Dr. Smith was notified at 1210 and orders received for CBC STAT and increased Vicodin dose to 10/325 mg.

R: Lab results pending. Additional Vicodin administered per order at 1215. At 1315, client reported decreased pain level of 3/10. Will notify provider of results when they become available. -J. White, RN

View sample charting by exception paper documentation with associated DAR notes for abnormal findings.

For more information about writing DAR notes, visit What is F-DAR Charting?

View a video explaining F-DAR charting.[4]

Narrative Notes

Narrative notes, also called summary notes, are a type of progress note that chronicles assessment findings and nursing activities for the client that occurred throughout the entire shift or visit. View sample narrative note documentation for body system assessments in the Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e textbook.

Sample Cardiac Narrative Note

Client denies chest pain or shortness of breath. Vital signs are within normal limits. Point of maximum impulse palpable at the fifth intercostal space of the midclavicular line. No lifts, heaves, or thrills identified on inspection or palpation. JVD absent. S1 and S2 heart sounds in regular rhythm with no murmurs or extra sounds. Skin is warm, pink, and dry. Capillary refill is less than two seconds. Color, movement, and sensation are intact in upper and lower extremities. Peripheral pulses are present (+2) and equal bilaterally. No peripheral edema is noted. Hair is distributed evenly on lower extremities.

SOAPIE Notes

SOAPIE is a mnemonic for a type of progress note that is organized by six categories: Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan, Interventions, and Evaluation. SOAPIE progress notes are written by nurses, as well as other members of the health care team.

- Subjective: This section includes what the client said, such as, “I have a headache.” It can also contain information related to pertinent medical history and why the client is in need of care.

- Objective: This section contains the observable and measurable data collected during a client assessment, such as the vital signs, physical examination findings, and lab/diagnostic test results.

- Assessment: This section contains the interpretation of what was noted in the Subjective and Objective sections, such as a nursing diagnosis in a nursing progress note or the medical diagnosis in a progress note written by a health care provider.

- Plan: This section outlines the plan of care based on the Assessment section, including goals and planned interventions.

- Interventions: This section describes the actions implemented.

- Evaluation: This section describes the client response to interventions and if the planned outcomes were met.

Sample SOAPIE Note

Here is an example of SOAPIE note with the same information previously discussed in the box describing a sample DAR note.

S: Client reports having incisional pain of 6/10, increased from 4/10 despite receiving oral Vicodin 5/325 at 1030.

O: Vital Signs: BP 160/95, HR 90, RR 22, O2 sat 96%, and temperature 38 degrees C. There is 4 cm of redness surrounding the incision that is warm and tender to touch with moderate serosanguinous drainage. Lung sounds are clear, and HR is regular.

A: Dr. Smith was notified at 1210.

P: New orders received for CBC STAT to check for infection and increased Vicodin dose to 10/325 mg for pain management.

I: Additional Vicodin administered per order at 1215.

E: At 1315, client reported decreased pain level of 3/10. Will notify provider of results when they become available. -J. White, RN

Discharge Summary

When a client is discharged from an agency, a discharge summary is documented in the client record, along with clear verbal and written client education and instructions provided to the client. Discharge summary information is frequently provided in a checklist format to ensure accuracy and includes the following:

- Time of departure and method of transportation out of the hospital (e.g., wheelchair)

- Name and relationship of person accompanying the client at discharge

- Condition of the client at discharge

- Client education completed and associated educational materials or other information provided to the client

- Discharge instructions on medications, treatments, diet, and activity

- Follow-up appointments or referrals given

See Figure 2.12[5] for an image of a nurse providing discharge instructions to a client. Discharge teaching typically starts at admission and continues throughout the client's stay because this allows for reinforcement of teaching topics.

Sample Discharge Summary Note

Client discharged home at 1645 with Sarah Jones, his wife, in a wheelchair to their car. Client was in stable condition with the following vital signs: BP 124/76, HR 76, RR 16, O2 sat 98%. Dressing over surgical incision site was dry and intact. Client education was provided on wound care at home and the "Caring for Your Incision" handout was provided. The Discharge Instructions sheet was reviewed with orders for a regular diet and no heavy lifting until follow-up appointment with Dr. Singer on 8/26/2024. Referral completed with ACME Home Health for wound care with the initial home visit scheduled for tomorrow.

Minimum Data Set (MDS) Charting

In long-term care settings, additional documentation is used to provide information for reimbursement by private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. The Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set (MDS) is a federally mandated assessment tool created by registered nurses in skilled nursing facilities to track a client’s goal achievement, as well as to coordinate the efforts of the health care team to optimize the resident’s quality of care and quality of life.[6] This tool also guides nursing care plan development.

Incident Reports

Incident reports, also called variance reports, are a specific type of documentation that is completed when there is an unexpected occurrence, such as a medication error, client injury, client fall, or a near miss, where an error did not actually occur, but was prevented from occurring. Refer to agency policies for specific events requiring incident reports.

Incident reports are completed by the staff member involved in the occurrence. Documentation includes the date and time of the event, client involved (if applicable), what occurred, what was done in response to the event, what else was happening at the time the incident occurred, as well as other facility specific required data. Abbreviations, assumptions, or interpretations should be avoided.

Incident reports are intended to be used as a safety tool to identify system issues and process problems that could benefit from quality and safety improvements. Incident reports should be used as component of a safety culture, not punitively. If used punitively, staff become reluctant to report errors or suggest process improvements for fear of “getting in trouble.”

Incident reports are not a part of the medical record and should not be mentioned in the medical record. However, the specific event should be documented in the medical record, along with health care provider notification and interventions provided.[7]

Read additional information about Incident Reports on the NSO website.

Client Scenario

Mr. Hernandez is a 47-year-old client admitted to the neurological trauma floor as the result of a motor vehicle accident two days ago. The client sustained significant facial trauma in the accident and his jaw is wired shut. His left eye is currently swollen, and he has significant bruising to the left side of his face. The nurse completes a visual assessment and notes that the client has normal extraocular movement, peripheral vision, and pupillary constriction bilaterally. Additional assessment reveals that Mr. Hernandez also sustained a fracture of the left arm and wrist during the accident. His left arm is currently in a cast and sling. He has normal movement and sensation with his right hand. Mrs. Hernandez is present at the client’s bedside and has provided additional information about the client. She reports that Mr. Hernandez’s primary language is Spanish but that he understands English well. He has a bachelor’s degree in accounting and owns his own accounting firm. He has a history of elevated blood pressure but is otherwise healthy.

The nurse notes that the client’s jaw is wired, and he is unable to offer a verbal response. He does understand English well, has appropriate visual acuity, and is able to move his right hand and arm.

Based on the assessment information that has been gathered, the nurse plans several actions to enhance communication. Adaptive communication devices such as communication boards, symbol cards, or electronic messaging systems will be provided. The nurse will eliminate distractions such as television and hallway noise to decrease sources of additional stimuli in the communication experience.

Sample Documentation Using a Summary Note:

6/01/2024, 1615: Mr. Hernandez has impaired verbal communication due to facial fracture and inability to enunciate words around his wired jaw. He understands both verbal and written communication. Mr. Hernandez has left sided facial swelling, but no visual impairment. He has a left arm fracture but is able to move and write with his right hand. The client is supplied with communication cards and marker board. He responds appropriately with written communication and is able to signal his needs. - J. Smith, RN

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Practice what you have learned in this chapter by completing these learning activities. When accessing the online activities that contain videos, it is best to use Google Chrome or Firefox browsers.

1. To test your understanding of therapeutic and nontherapeutic terms, complete this online quiz:

Therapeutic Communication Techniques vs. Non-therapeutic Communication Techniques Quizlet

2. Consider the following scenario and describe actions that you might take to facilitate the communication experience.

You are caring for Mr. Curtis, an 87-year-old client newly admitted to the medical surgical floor with a hip fracture. You are preparing to complete his admission history and need to collect relevant health information and complete a physical exam. You approach the room, knock at the door, complete hand hygiene, and enter. Upon entry, you see Mr. Curtis is in bed surrounded by multiple family members. The television is on in the background, and you also note the sound of meal trays being delivered in the hallway.

Based on the described scenario, what actions might be implemented to aid in your communication with Mr. Curtis?

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[8]

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[9]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Practice what you have learned in this chapter by completing these learning activities. When accessing the online activities that contain videos, it is best to use Google Chrome or Firefox browsers.

1. To test your understanding of therapeutic and nontherapeutic terms, complete this online quiz:

Therapeutic Communication Techniques vs. Non-therapeutic Communication Techniques Quizlet

2. Consider the following scenario and describe actions that you might take to facilitate the communication experience.

You are caring for Mr. Curtis, an 87-year-old client newly admitted to the medical surgical floor with a hip fracture. You are preparing to complete his admission history and need to collect relevant health information and complete a physical exam. You approach the room, knock at the door, complete hand hygiene, and enter. Upon entry, you see Mr. Curtis is in bed surrounded by multiple family members. The television is on in the background, and you also note the sound of meal trays being delivered in the hallway.

Based on the described scenario, what actions might be implemented to aid in your communication with Mr. Curtis?

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[10]

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[11]

Active listening: Process by which we are communicating verbally and nonverbally that we are interested in what the other person is saying while also actively verifying our understanding with the speaker. (Chapter 2.3)

Aphasia: A communication disorder that results from damage to portions of the brain that are responsible for language. (Chapter 2.3)

Assertive communication: A way to convey information that describes the facts, the sender’s feelings, and explanations without disrespecting the receiver’s feelings. This communication is often described as using “I” messages: “I feel…,” “I understand…,” or “Help me to understand…” (Chapter 2.2)

Bedside handoff report: A handoff report in hospitals that involves clients, their family members, and both the off-going and the incoming nurses. The report is performed face to face and conducted at the client's bedside. (Chapter 2.4)

Broca's aphasia: A type of aphasia where clients understand speech and know what they want to say, but frequently speak in short phrases that are produced with great effort. People with Broca's aphasia typically understand the speech of others fairly well. Because of this, they are often aware of their difficulties and can become easily frustrated. (Chapter 2.3)

Charting by exception (CBE): A type of documentation where a list of “normal findings” is provided and nurses document assessment findings by confirming normal findings and writing brief documentation notes for any abnormal findings. (Chapter 2.5)

DAR: A type of documentation often used in combination with charting by exception. DAR stands for Data, Action, and Response. Focused DAR notes are brief, and each note is focused on one client problem for efficiency in documenting, as well as for reading. (Chapter 2.5)

Electronic Health Record (EHR): A digital version of a client’s paper chart. EHRs are real-time, client-centered records that make information available instantly and securely to authorized users. (Chapter 2.5)

Expressive aphasia: A type of aphasia where the client has difficulty putting thoughts into words. The client may cognitively know what they want to say but are unable to express their thoughts. (Chapter 1.4, Chapter 2.3)

Global aphasia: A type of aphasia that results from damage to extensive portions of the language areas of the brain. Individuals with global aphasia have severe communication difficulties and may be extremely limited in their ability to speak or comprehend language. They may be unable to say even a few words or may repeat the same words or phrases over and over again. They may have trouble understanding even simple words and sentences. (Chapter 2.3)

Handoff report: A process of exchanging vital client information, responsibility, and accountability between the off-going and incoming nurses in an effort to ensure safe continuity of care and the delivery of best clinical practices. (Chapter 2.4)

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA): Standards for ensuring privacy of client information that are enforceable by law. (Chapter 2.3)

Incident reports: Also called variance reports, incident reports are a specific type of documentation that is completed when there is an unexpected occurrence, such as a medication error, client injury, or client fall, or a near miss, where an error did not actually occur, but was prevented from occurring. (Chapter 2.5)

ISBARR: A mnemonic for the format of professional communication among health care team members that includes Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back. (Chapter 2.4)

Minimum Data Set (MDS): A federally mandated assessment tool used in skilled nursing facilities to track a client’s goal achievement, as well as to coordinate the efforts of the health care team to optimize the resident’s quality of care and quality of life. (Chapter 2.5)

Narrative note: A type of documentation that chronicles all of the client’s assessment findings and nursing activities that occurred throughout the shift. (Chapter 2.5)

Nontherapeutic responses: Responses to clients that block communication, expression of emotion, or problem-solving. (Chapter 2.3)

Nonverbal communication: Facial expressions, tone of voice, pace of the conversation, and body language. (Chapter 2.2)

Progressive relaxation: Types of relaxation techniques that focus on reducing muscle tension and using mental imagery to induce calmness. (Chapter 2.2)

Receptive aphasia: A type of aphasia where the client has difficulty in understanding what is being communicated to them. The client may be able to verbalize their thoughts and feelings but does not understand what is spoken to them. (Chapter 2.3)

Relaxation breathing: A breathing technique used to reduce anxiety and control the stress response. (Chapter 2.2)

SOAPIE: A mnemonic for a type of documentation that is organized by six categories: Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan, Interventions, and Evaluation. (Chapter 2.5)

Therapeutic communication: The purposeful, interpersonal information transmitting process through words and behaviors based on both parties’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills, which leads to client understanding and participation. (Chapter 2.3)

Therapeutic communication techniques: Techniques that encourage clients to explore feelings, problem solve, and cope with responses to medical conditions and life events. (Chapter 2.3)

Verbal communication: Exchange of information using words understood by the receiver. (Chapter 2.2)

Learning Objectives

- Prioritize nursing care based on patient acuity

- Use principles of time management to organize work

- Analyze effectiveness of time management strategies

- Use critical thinking to prioritize nursing care for patients

- Apply a framework for prioritization (e.g., Maslow, ABCs)

“So much to do, so little time.” This is a common mantra of today’s practicing nurse in various health care settings. Whether practicing in acute inpatient care, long-term care, clinics, home care, or other agencies, nurses may feel there is "not enough of them to go around.”

The health care system faces a significant challenge in balancing the ever-expanding task of meeting patient care needs with scarce nursing resources that has even worsened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many health care organizations have seen exacerbation in nurse turnover post-pandemic as nurses struggle with increasing stress, burnout, and feeling of uncertainty within the profession.[12] A recent nursing survey done by the American Nurses Foundation found that 60% of nurses reported extremely stressful, violent, and traumatic events as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[13] Additionally, a staggering 89% of nurses reported that their organizations experience significant staffing shortages.[14]

With a limited supply of registered nurses, nurse managers are often challenged to implement creative staffing practices such as sending staff to units where they do not normally work (i.e., floating), implementing mandatory staffing and/or overtime, utilizing travel nurses, or using other practices to meet patient care demands.[15] Staffing strategies can result in nurses experiencing increased patient assignments and workloads, extended shifts, or temporary suspension of paid time off. Nurses may receive a barrage of calls and text messages offering “extra shifts” and bonus pay, and although the extra pay may be welcomed, they often eventually feel burnt out trying to meet the ever-expanding demands of the patient-care environment.

A novice nurse who is still learning how to navigate the complex health care environment and provide optimal patient care may feel overwhelmed by these conditions. Novice nurses frequently report increased levels of stress and disillusionment as they transition to the reality of the nursing role.[16] How can we address this professional dilemma and enhance the novice nurse's successful role transition to practice? The novice nurse must enter the profession with purposeful tools and strategies to help prioritize tasks and manage time so they can confidently address patient care needs, balance role demands, and manage day-to-day nursing activities.

Let’s take a closer look at the foundational concepts related to prioritization and time management in the nursing profession.

Learning Objectives

- Prioritize nursing care based on patient acuity

- Use principles of time management to organize work

- Analyze effectiveness of time management strategies

- Use critical thinking to prioritize nursing care for patients

- Apply a framework for prioritization (e.g., Maslow, ABCs)

“So much to do, so little time.” This is a common mantra of today’s practicing nurse in various health care settings. Whether practicing in acute inpatient care, long-term care, clinics, home care, or other agencies, nurses may feel there is "not enough of them to go around.”

The health care system faces a significant challenge in balancing the ever-expanding task of meeting patient care needs with scarce nursing resources that has even worsened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many health care organizations have seen exacerbation in nurse turnover post-pandemic as nurses struggle with increasing stress, burnout, and feeling of uncertainty within the profession.[17] A recent nursing survey done by the American Nurses Foundation found that 60% of nurses reported extremely stressful, violent, and traumatic events as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[18] Additionally, a staggering 89% of nurses reported that their organizations experience significant staffing shortages.[19]

With a limited supply of registered nurses, nurse managers are often challenged to implement creative staffing practices such as sending staff to units where they do not normally work (i.e., floating), implementing mandatory staffing and/or overtime, utilizing travel nurses, or using other practices to meet patient care demands.[20] Staffing strategies can result in nurses experiencing increased patient assignments and workloads, extended shifts, or temporary suspension of paid time off. Nurses may receive a barrage of calls and text messages offering “extra shifts” and bonus pay, and although the extra pay may be welcomed, they often eventually feel burnt out trying to meet the ever-expanding demands of the patient-care environment.

A novice nurse who is still learning how to navigate the complex health care environment and provide optimal patient care may feel overwhelmed by these conditions. Novice nurses frequently report increased levels of stress and disillusionment as they transition to the reality of the nursing role.[21] How can we address this professional dilemma and enhance the novice nurse's successful role transition to practice? The novice nurse must enter the profession with purposeful tools and strategies to help prioritize tasks and manage time so they can confidently address patient care needs, balance role demands, and manage day-to-day nursing activities.

Let’s take a closer look at the foundational concepts related to prioritization and time management in the nursing profession.

Prioritization

As new nurses begin their career, they look forward to caring for others, promoting health, and saving lives. However, when entering the health care environment, they often discover there are numerous and competing demands for their time and attention. Patient care is often interrupted by call lights, rounding physicians, and phone calls from the laboratory department or other interprofessional team members. Even individuals who are strategic and energized in their planning can feel frustrated as their task lists and planned patient-care activities build into a long collection of “to dos.”

Without utilization of appropriate prioritization strategies, nurses can experience time scarcity, a feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against them. Functioning under the burden of time scarcity can cause feelings of frustration, inadequacy, and eventually burnout. Time scarcity can also impact patient safety, resulting in adverse events and increased mortality.[22] Additionally, missed or rushed nursing activities can negatively impact patient satisfaction scores that ultimately affect an institution's reimbursement levels.

It is vital for nurses to plan patient care and implement their task lists while ensuring that critical interventions are safely implemented first. Identifying priority patient problems and implementing priority interventions are skills that require ongoing cultivation as one gains experience in the practice environment.[23] To develop these skills, students must develop an understanding of organizing frameworks and prioritization processes for delineating care needs. These frameworks provide structure and guidance for meeting the multiple and ever-changing demands in the complex health care environment.

Let’s consider a clinical scenario in the following box to better understand the implications of prioritization and outcomes.

Scenario A

Imagine you are beginning your shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. You receive a handoff report on four medical-surgical patients from the night shift nurse:

- Patient A is a 34-year-old total knee replacement patient, post-op Day 1, who had an uneventful night. It is anticipated that she will be discharged today and needs patient education for self-care at home.

- Patient B is a 67-year-old male admitted with weakness, confusion, and a suspected urinary tract infection. He has been restless and attempting to get out of bed throughout the night. He has a bed alarm in place.

- Patient C is a 49-year-old male, post-op Day 1 for a total hip replacement. He has been frequently using his patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump and last rated his pain as a "6."

- Patient D is a 73-year-old male admitted for pneumonia. He has been hospitalized for three days and receiving intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His next dose is due in an hour. His oxygen requirements have decreased from 4 L/minute of oxygen by nasal cannula to 2 L/minute by nasal cannula.

Based on the handoff report you received, you ask the nursing assistant to check on Patient B while you do an initial assessment on Patient D. As you are assessing Patient D's oxygenation status, you receive a phone call from the laboratory department relating a critical lab value on Patient C, indicating his hemoglobin is low. The provider calls and orders a STAT blood transfusion for Patient C. Patient A rings the call light and states she and her husband have questions about her discharge and are ready to go home. The nursing assistant finds you and reports that Patient B got out of bed and experienced a fall during the handoff reports.

It is common for nurses to manage multiple and ever-changing tasks and activities like this scenario, illustrating the importance of self-organization and priority setting. This chapter will further discuss the tools nurses can use for prioritization.

Prioritization

As new nurses begin their career, they look forward to caring for others, promoting health, and saving lives. However, when entering the health care environment, they often discover there are numerous and competing demands for their time and attention. Patient care is often interrupted by call lights, rounding physicians, and phone calls from the laboratory department or other interprofessional team members. Even individuals who are strategic and energized in their planning can feel frustrated as their task lists and planned patient-care activities build into a long collection of “to dos.”

Without utilization of appropriate prioritization strategies, nurses can experience time scarcity, a feeling of racing against a clock that is continually working against them. Functioning under the burden of time scarcity can cause feelings of frustration, inadequacy, and eventually burnout. Time scarcity can also impact patient safety, resulting in adverse events and increased mortality.[24] Additionally, missed or rushed nursing activities can negatively impact patient satisfaction scores that ultimately affect an institution's reimbursement levels.

It is vital for nurses to plan patient care and implement their task lists while ensuring that critical interventions are safely implemented first. Identifying priority patient problems and implementing priority interventions are skills that require ongoing cultivation as one gains experience in the practice environment.[25] To develop these skills, students must develop an understanding of organizing frameworks and prioritization processes for delineating care needs. These frameworks provide structure and guidance for meeting the multiple and ever-changing demands in the complex health care environment.

Let’s consider a clinical scenario in the following box to better understand the implications of prioritization and outcomes.

Scenario A

Imagine you are beginning your shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. You receive a handoff report on four medical-surgical patients from the night shift nurse:

- Patient A is a 34-year-old total knee replacement patient, post-op Day 1, who had an uneventful night. It is anticipated that she will be discharged today and needs patient education for self-care at home.

- Patient B is a 67-year-old male admitted with weakness, confusion, and a suspected urinary tract infection. He has been restless and attempting to get out of bed throughout the night. He has a bed alarm in place.

- Patient C is a 49-year-old male, post-op Day 1 for a total hip replacement. He has been frequently using his patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump and last rated his pain as a "6."

- Patient D is a 73-year-old male admitted for pneumonia. He has been hospitalized for three days and receiving intravenous (IV) antibiotics. His next dose is due in an hour. His oxygen requirements have decreased from 4 L/minute of oxygen by nasal cannula to 2 L/minute by nasal cannula.

Based on the handoff report you received, you ask the nursing assistant to check on Patient B while you do an initial assessment on Patient D. As you are assessing Patient D's oxygenation status, you receive a phone call from the laboratory department relating a critical lab value on Patient C, indicating his hemoglobin is low. The provider calls and orders a STAT blood transfusion for Patient C. Patient A rings the call light and states she and her husband have questions about her discharge and are ready to go home. The nursing assistant finds you and reports that Patient B got out of bed and experienced a fall during the handoff reports.

It is common for nurses to manage multiple and ever-changing tasks and activities like this scenario, illustrating the importance of self-organization and priority setting. This chapter will further discuss the tools nurses can use for prioritization.

Prioritization of care for multiple patients while also performing daily nursing tasks can feel overwhelming in today’s fast-paced health care system. Because of the rapid and ever-changing conditions of patients and the structure of one’s workday, nurses must use organizational frameworks to prioritize actions and interventions. These frameworks can help ease anxiety, enhance personal organization and confidence, and ensure patient safety.

Acuity

Acuity and intensity are foundational concepts for prioritizing nursing care and interventions. Acuity refers to the level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. For example, acuity may include characteristics such as unstable vital signs, oxygenation therapy, high-risk IV medications, multiple drainage devices, or uncontrolled pain. A "high-acuity" patient requires several nursing interventions and frequent nursing assessments.

Intensity addresses the time needed to complete nursing care and interventions such as providing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), performing wound care, or administering several medication passes. For example, a "high-intensity" patient generally requires frequent or long periods of psychosocial, educational, or hygiene care from nursing staff members. High-intensity patients may also have increased needs for safety monitoring, familial support, or other needs.[26]

Many health care organizations structure their staffing assignments based on acuity and intensity ratings to help provide equity in staff assignments. Acuity helps to ensure that nursing care is strategically divided among nursing staff. An equitable assignment of patients benefits both the nurse and patient by helping to ensure that patient care needs do not overwhelm individual staff and safe care is provided.

Organizations use a variety of systems when determining patient acuity with rating scales based on nursing care delivery, patient stability, and care needs. See an example of a patient acuity tool published in the American Nurse in Table 2.3.[27] In this example, ratings range from 1 to 4, with a rating of 1 indicating a relatively stable patient requiring minimal individualized nursing care and intervention. A rating of 2 reflects a patient with a moderate risk who may require more frequent intervention or assessment. A rating of 3 is attributed to a complex patient who requires frequent intervention and assessment. This patient might also be a new admission or someone who is confused and requires more direct observation. A rating of 4 reflects a high-risk patient. For example, this individual may be experiencing frequent changes in vital signs, may require complex interventions such as the administration of blood transfusions, or may be experiencing significant uncontrolled pain. An individual with a rating of 4 requires more direct nursing care and intervention than a patient with a rating of 1 or 2.[28]

Table 2.3. Example of a Patient Acuity Tool[29]

| 1: Stable Patient | 2: Moderate-Risk Patient | 3: Complex Patient | 4: High-Risk Patient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

|

|

| Cardiac |

|

|

|

|

| Medications |

|

|

|

|

| Drainage Devices |

|

|

|

|

| Pain Management |

|

|

|

|

| Admit/Transfer/Discharge |

|

|

|

|

| ADLs and Isolation |

|

|

|

|

| Patient Score | Most = 1 | Two or > = 2 | Any = 3 | Any = 4 |

Read more about using a patient acuity tool on a medical-surgical unit.

Rating scales may vary among institutions, but the principles of the rating system remain the same. Organizations include various patient care elements when constructing their staffing plans for each unit. Read more information about staffing models and acuity in the following box.

Staffing Models and Acuity

Organizations that base staffing on acuity systems attempt to evenly staff patient assignments according to their acuity ratings. This means that when comparing patient assignments across nurses on a unit, similar acuity team scores should be seen with the goal of achieving equitable and safe division of workload across the nursing team. For example, one nurse should not have a total acuity score of 6 for their patient assignments while another nurse has a score of 15. If this situation occurred, the variation in scoring reflects a discrepancy in workload balance and would likely be perceived by nursing peers as unfair. Using acuity-rating staffing models is helpful to reflect the individualized nursing care required by different patients.

Alternatively, nurse staffing models may be determined by staffing ratio. Ratio-based staffing models are more straightforward in nature, where each nurse is assigned care for a set number of patients during their shift. Ratio-based staffing models may be useful for administrators creating budget requests based on the number of staff required for patient care, but can lead to an inequitable division of work across the nursing team when patient acuity is not considered. Increasingly complex patients require more time and interventions than others, so a blend of both ratio and acuity-based staffing is helpful when determining staffing assignments.[30]