Basic Concepts of Enteral Tubes

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Gastrointestinal Function

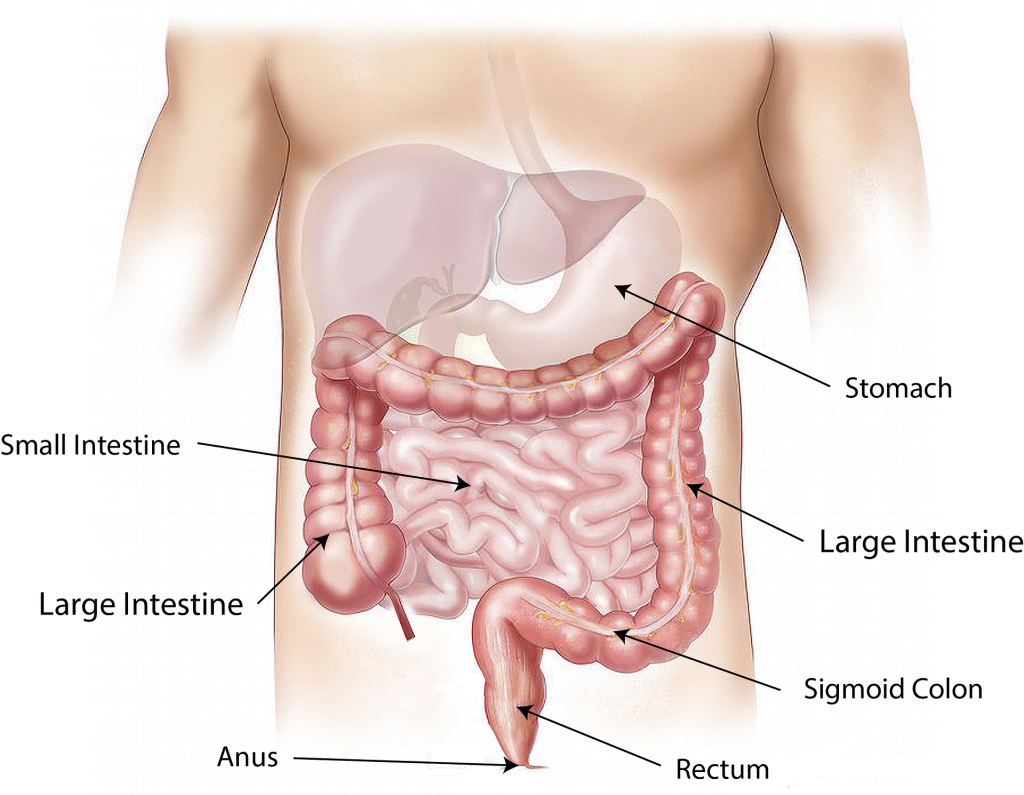

It is important to understand the anatomy and functioning of the gastrointestinal system before administering feedings or medications through an enteral tube. See Figure 17.1[1] for an illustration of the anatomy of the gastrointestinal system.

For more information about the digestive function of the gastrointestinal system, visit the “Gastrointestinal System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition is indicated for patients who need nutritional supplementation and have a functioning gastrointestinal tract, but cannot swallow food safely. Feedings can be administered via enteral tubes placed into the stomach or into the small intestine (usually the jejunum). For example, enteral feeding is commonly used for patients with the following conditions:

- Impaired swallowing (such as from a stroke or Parkinson’s disease)

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation

- Oropharyngeal or esophageal obstruction (such as in head or neck cancer)

- Hypercatabolic states (such as in severe burns)[2]

For short-term feeding, NG tubes are used. If the duration of feeding is longer than four weeks or if access through the nose is contraindicated, a surgery is performed to place the tube directly through the gastrointestinal wall (for example, PEG or PEJ tubes).

Patients who are not candidates for enteral nutrition are prescribed parenteral nutrition. Parenteral nutrition is a concentrated intravenous solution containing glucose, amino acids, minerals, electrolytes, and vitamins. A lipid solution is typically administered as a separate infusion. This combination of solutions is called total parenteral nutrition because it supplies complete nutritional support. Parenteral nutrition is administered via a large central intravenous line, typically the subclavian or internal jugular vein, because it is irritating to the blood vessels.

Types of Enteral Tubes

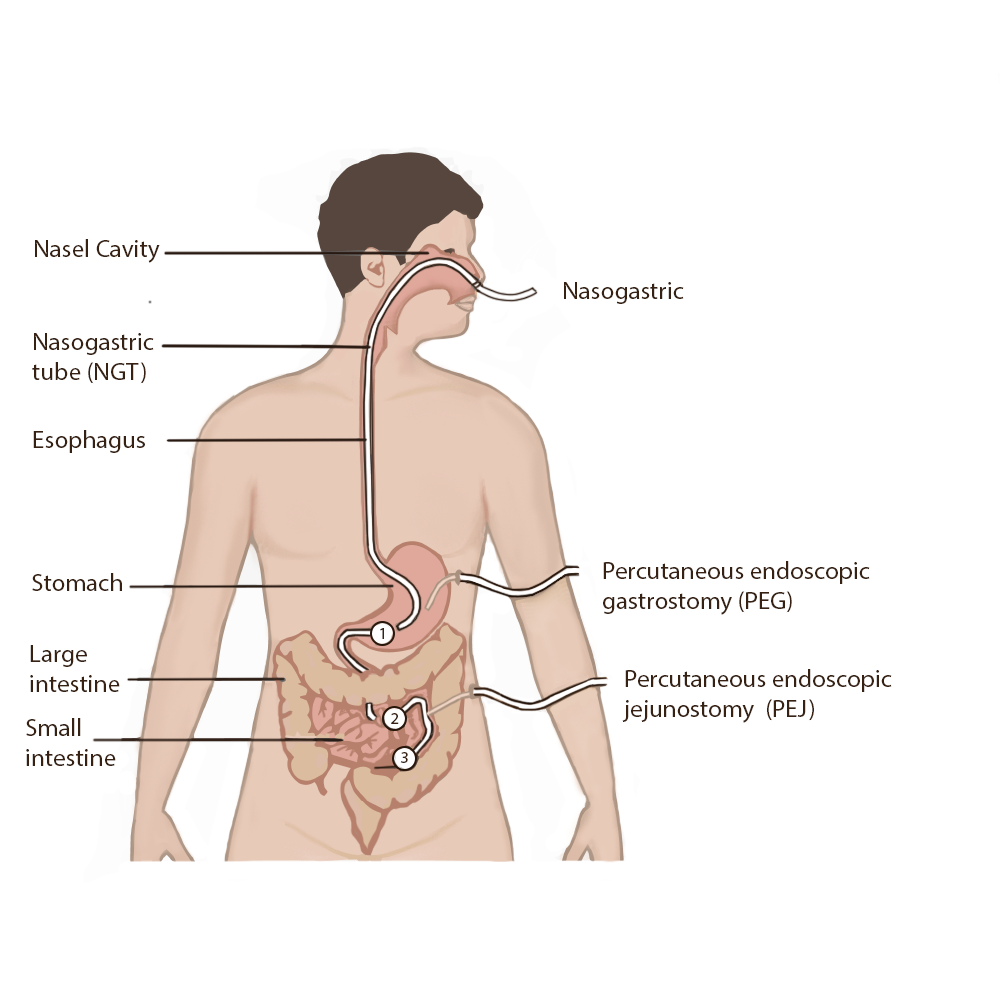

There are several different types of enteral tubes based on their location in the gastrointestinal system, as well as their function. Three commonly used enteral tubes are the nasogastric tube, the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, and the percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ) tube. See Figure 17.2[3] for an illustration of common enteral tubes. NG tubes are typically used for a short period of time (less than four weeks), whereas PEG and PEJ tubes are inserted for long-term enteral nutrition. Some institutions also place nasoduodenal (ND) tubes to provide long-term enteral nutrition.[4]

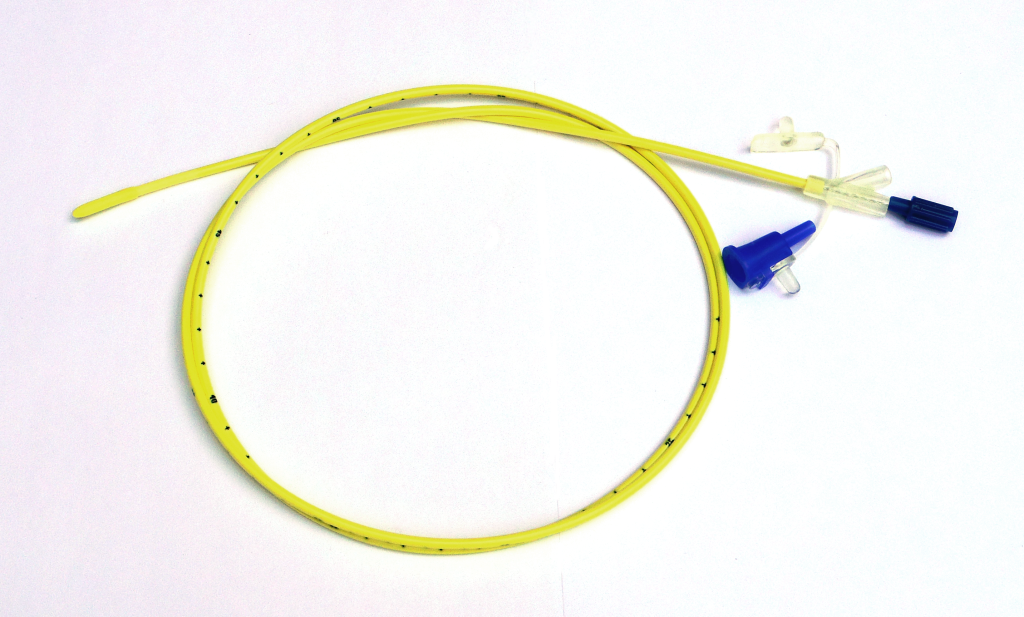

A nasogastric (NG) tube is a single- or double-lumen tube that is inserted into the nasopharynx through the esophagus and into the stomach. NG tubes can be used for feeding, medication administration, and suctioning. NG tubes used for feeding and medication administration are small and flexible, whereas NG tubes used for suctioning are larger and more rigid. NG tubes are secured externally on the patient’s nose or cheek by adhesive tape or a fixation device, so this area should be assessed daily for signs of pressure damage. See Figure 17.3[5] for an image of a small-bore feeding tube.

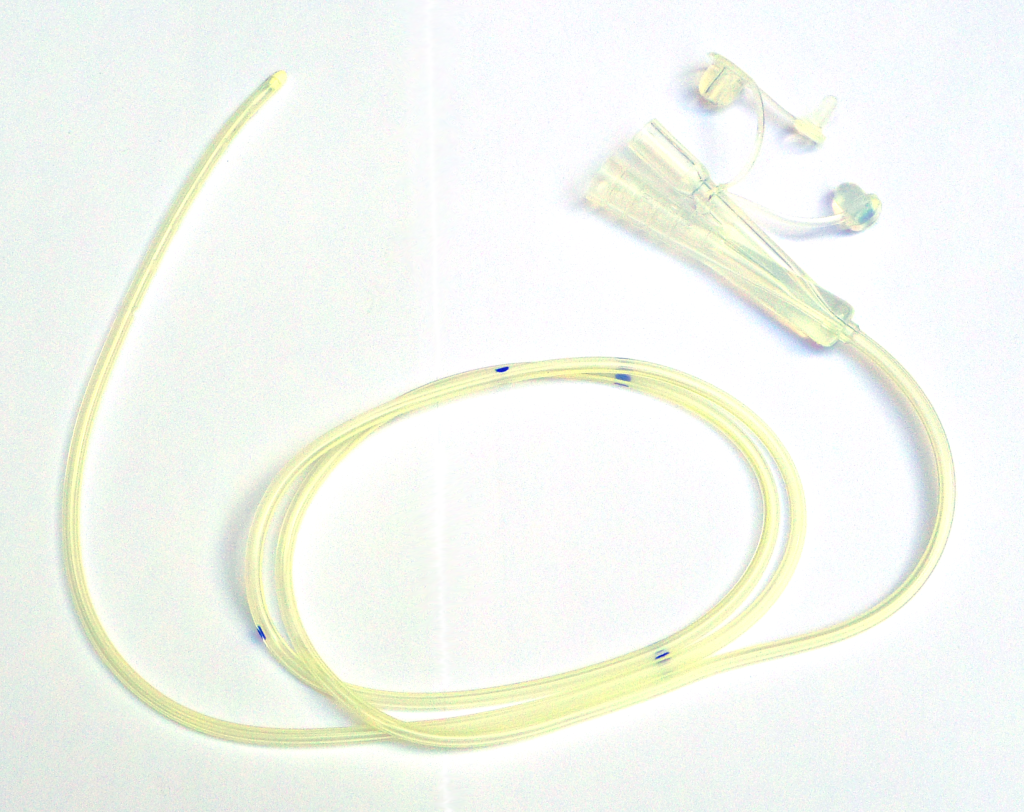

An example of a large-bore nasogastric tube is the Salem Sump. Large-bore nasogastric tubes, such as the Salem Sump, are used for gastric decompression. The Salem Sump has a double-lumen that includes a venting system. One lumen is used to empty the stomach, and the other lumen is used to provide a continuous flow of air. The continuous flow of air reduces negative pressure and prevents gastric mucosa from being drawn into the catheter, which causes mucosal damage. This terminal end also has an anti-reflux valve to prevent gastric secretions from traveling through the wrong lumen. See Figure 17.4[6] for an example of a double-lumen enteral tube.

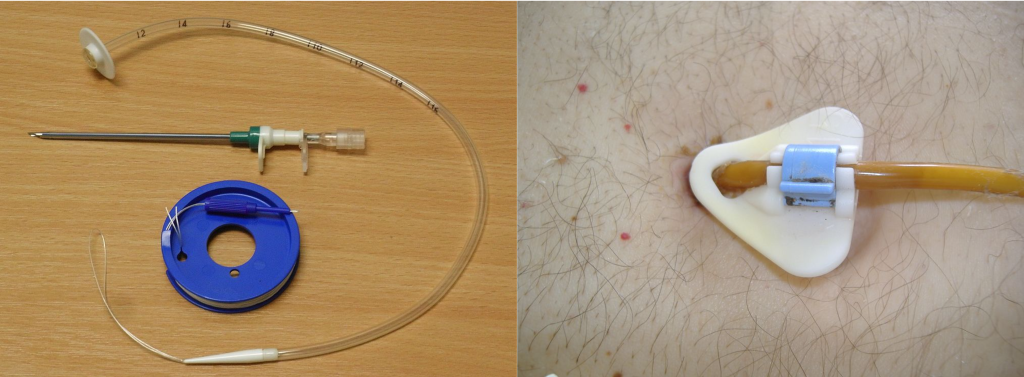

Other types of tubes are placed through the patient’s abdominal wall and are used for long-term enteral feeding. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is placed via an endoscopic procedure into the stomach. Alternatively, a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ) tube is placed in the jejunum of the small intestine for patients who cannot tolerate the administration of enteral formula or medications into the stomach due to medical conditions such as delayed gastric emptying. See Figure 17.5[7] for an image of a PEG tube insertion kit and the appearance of an enteral tube as it exits from a patient’s abdomen.

Assessing Tube Placement

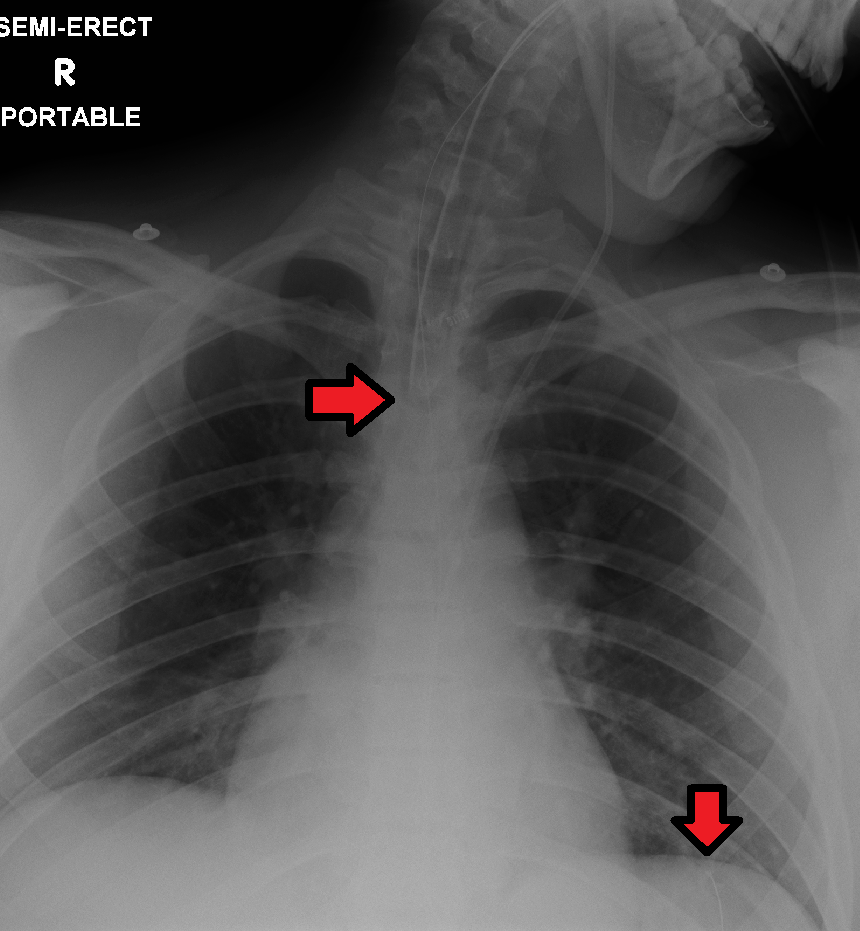

Feedings or medications administered into an incorrectly placed enteral tube result in life-threatening aspiration pneumonia. The placement of an enteral tube is immediately verified after insertion by an X-ray to ensure it has not been inadvertently placed into the trachea and down into the bronchi. See Figure 17.6[8] for an image of an X-ray demonstrating correct placement of an enteral tube in the stomach as indicated by the lower red arrow. (This X-ray also demonstrates an endotracheal tube correctly placed in the trachea as indicated by the top arrow.) After X-ray verification, the tube should be marked with adhesive tape and/or a permanent marker to indicate the point on the tube where the feeding tube enters the nares or penetrates the abdominal wall. This number on the tube at the entry point should be documented in the medical record and communicated during handoff reports. At the start of every shift, nurses evaluate if the incremental marking or external tube length has changed. If a change is observed, bedside tests such as visualization or pH testing of tube aspirate can help determine if the tube has become dislocated. If in doubt, a radiograph should be obtained to determine tube location.[9]

After the initial verification of tube placement by X-ray, it is possible for the tube to migrate out of position due to the patient coughing, vomiting, and moving. For this reason, the nurse must routinely check tube placement before every use. The American Association of Critical‐Care Nursing recommends that the position of a feeding tube should be checked and documented every four hours and prior to the administration of enteral feedings and medications by measuring the visible tube length and comparing it to the length documented during X-ray verification.[10],[11],[12]

Older methods of checking tube placement included observing aspirated GI contents or the administration of air with a syringe while auscultating (commonly referred to as the “whoosh test”). However, research has determined these methods are unreliable and should no longer be used to verify placement.[13],[14]

Checking the pH of aspirated gastric contents is an alternative method to verify placement that may be used in some agencies. Gastric aspirate should have a pH of less than or equal to 5.5 using pH indicator paper that is marked for use with human aspirate. However, caution should be used with this method because enteral formula and some medications alter the gastric pH.[15]

Follow agency policy for assessing and documenting tube placement. Additionally, if the patient develops respiratory symptoms that indicate potential aspiration, immediately notify the provider and withhold enteral feedings and medications until the placement is verified.

Assessing and Cleaning the Tube Insertion Site

The area of tube insertion should be assessed daily for signs of pressure damage. For NG tubes, the adhesive used to secure the tube can be irritating and cause skin breakdown. PEG and PEJ tubes may have fluid seepage around the insertion point that can cause skin breakdown if not cleaned regularly. Follow agency policy for cleansing the external insertion site for PEG and PEJ tubes. Cleansing is typically performed using gauze moistened with water or saline and then allowed to air dry before the fixation plate is repositioned. Because skin surrounding the insertion site is prone to breakdown, barrier cream or dressings may be prescribed to prevent breakdown.[16],[17]

Tube Feeding

Enteral nutrition (EN) refers to nutrition provided directly into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract through an enteral route that bypasses the oral cavity. Each year in the United States, over 250,000 hospitalized patients from infants to older adults receive EN. It is also used widely in rehabilitation, long‐term care, and home settings. EN requires a multidisciplinary team approach, including a registered dietician, health care provider, pharmacist, and bedside nurses. The registered dietician performs a nutrition assessment and determines what type of enteral nutrition is appropriate to promote improved patient outcomes. The health care provider writes the order for the enteral nutrition. Prescriptions for enteral nutrition should be reviewed by the nurse for the following components: type of enteral nutrition formula, amount and frequency of free water flushes, route of administration, administration method, and rate. Any concerns about the components of the prescription should be verified with the provider before tube feeding is administered.[18]

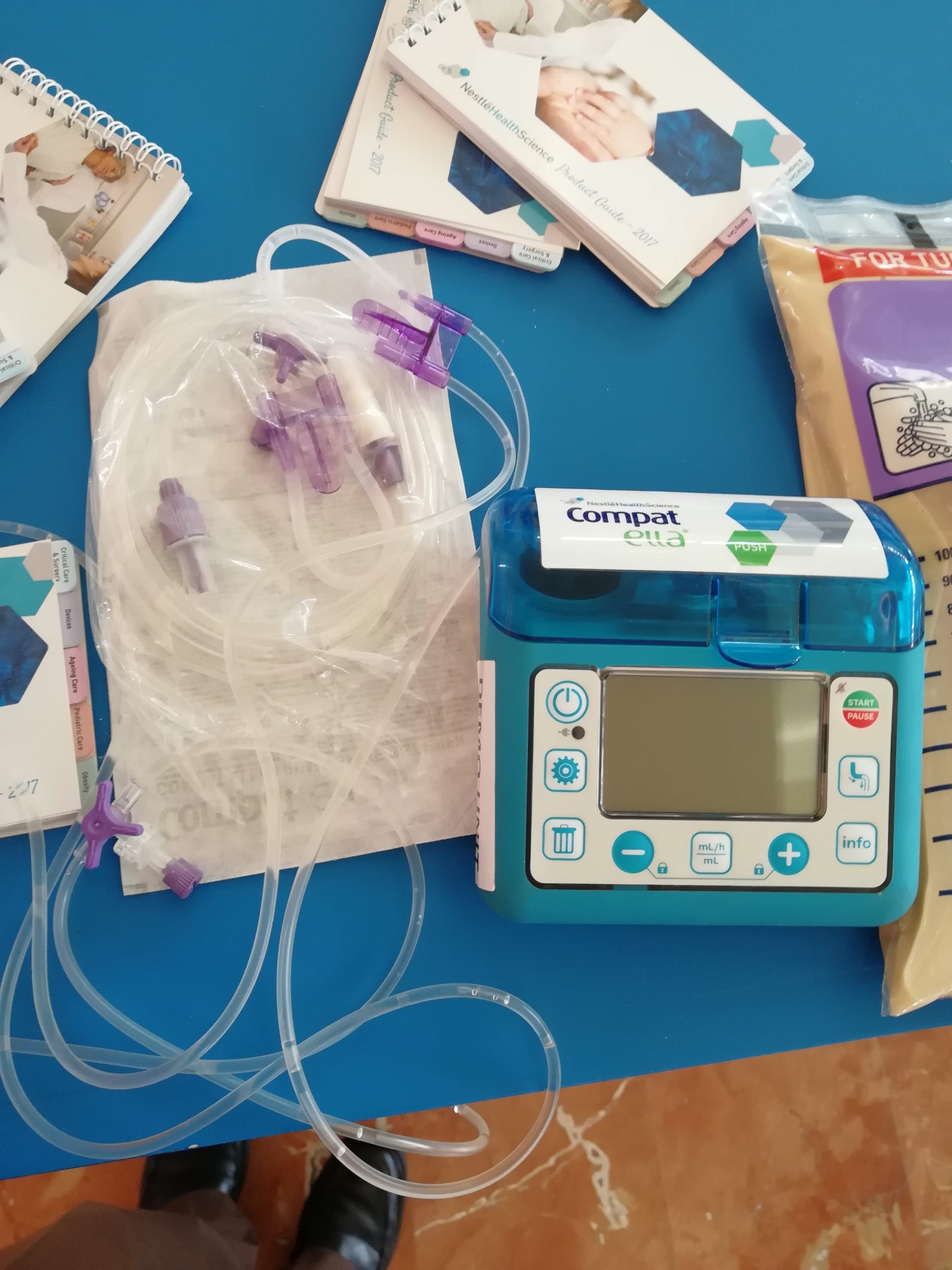

Tube feeding can be administered using gravity to provide a bolus feeding or via a pump to provide continuous or intermittent feeding. Feedings via a pump are set up in mL/hr, with the rate prescribed by the health care provider. See Figure 17.7[19] for an image of an enteral tube feeding pump and the associated tubing. Note that tubing used for enteral feeding is indicated by specific colors (such as purple in Figure 17.7). A global safety initiative, referred to as “EnFit,” is in progress to ensure all devices used with enteral feeding, such as extension sets, syringes, PEG tubes, and NG tubes have specific EnFit ends that can only be used with tube feeding sets. This new safety design will avoid inadvertent administration of enteral feeding into intravenous tubing that can cause life-threatening adverse effects.

Review the “Checklist for NG Tube Enteral Feeding by Gravity With Irrigation” section for additional information regarding administering bolus feedings by gravity.

Life Span Considerations

Enteral feeding is administered to infants and children via a syringe, gravity feeding set, or feeding pump. The method selected is dependent on the nature of the feeding and clinical status of the child.[20]

Complications of Enteral Feeding

The most serious complication of enteral feeding is inadvertent respiratory aspiration of gastric contents, causing life-threatening aspiration pneumonia. Other complications include tube clogging, tubing misconnections, and patient intolerance of enteral feeding.[21]

Reducing Risk of Aspiration

In addition to verifying tube placement as discussed in an earlier section, nurses perform additional interventions to prevent aspiration. The American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses recommends the following guidelines to reduce the risk for aspiration:

- Maintain the head of the bed at 30°-45° unless contraindicated

- Use sedatives as sparingly as possible

- Assess feeding tube placement at four‐hour intervals

- Observe for change in the amount of external length of the tube

- Assess for gastrointestinal intolerance at four‐hour intervals[22]

Measurement of gastric residual volume (GRV) is performed by using a 60-mL syringe to aspirate stomach contents through the tube. It has traditionally been used to assess aspiration risk with associated interventions such as slowing or stopping the enteral feeding. GRVs in the range of 200–500 mL cause interventions such as slowing or stopping the feeding to reduce risk of aspiration. However, according to recent research, it is not appropriate to stop enteral nutrition for GRVs less than 500 mL in the absence of other signs of intolerance because of the impact on the patient’s overall nutritional status. Additionally, the aspiration of gastric residual volumes can contribute to tube clogging.[23] Follow agency policy regarding measuring gastric residual volume and implementing interventions to prevent aspiration.

Managing Tube Clogging

Feeding tubes are prone to clogging for a variety of reasons. The risk of clogging may result from tube properties (such as narrow tube diameter), the tube tip location (stomach vs. small intestine), insufficient water flushes, aspiration for gastric residual volume (GRV), contaminated formula, and incorrect medication preparation and administration. A clogged feeding tube can result in decreased nutrient delivery or delayed administration of medication, and, if not corrected, the patient may require additional surgical intervention to replace the tube.[24]

Research supports using water as the best choice for initial declogging efforts. Instill warm water into the tube using a 60‐mL syringe and apply a gentle back‐and‐forth motion with the plunger of the syringe. Research shows that the use of cranberry juice and carbonated beverages to flush the tube can worsen tube occlusions because the acidic pH of these fluids can cause proteins in the enteral formula to precipitate within the tube. If water does not work, a pancreatic enzyme solution, an enzymatic declogging kit, or mechanical devices for clearing feeding tubes are the best second‐line options.[25]

To prevent enteral tubes from clogging, it is important to follow these guidelines:

- Flush feeding tubes at a minimum of once a shift.

- Flush feeding tubes immediately before and after intermittent feedings. During continuous feedings, flush at standardized, scheduled intervals.

- Flush feeding tubes before and after medication administration and follow appropriate medication administration practices.

- Limit gastric residual volume checks because the acidic gastric contents may cause protein in enteral formulas to precipitate within the lumen of the tube.[26]

Preventing Tubing Misconnections

In April 2006, The Joint Commission issued a Sentinel Event Alert on tubing misconnections due to enteral feedings being inadvertently infused into intravenous lines with life-threatening results. A color-coded enteral tubing connection design was developed to visually communicate the difference between enteral tubing and intravenous tubing. In addition to tubing design, follow these guidelines to prevent tubing misconnection errors:

- Make tubing connections under proper lighting.

- Do not modify or adapt IV or feeding devices because doing so may compromise the safety features incorporated into their design.

- When making a reconnection, routinely trace lines back to their origins and then ensure that they are secure.

- As part of a hand‐off process, recheck connections and trace all tubes back to their origins.[27]

Managing Intolerances and Imbalances

Patients should be monitored daily for signs of tube feeding intolerance, such as abdominal bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramping, and constipation. If cramping occurs during bolus feedings, it can be helpful to administer the enteral nutritional formula at room temperature to prevent symptoms.[28] Notify the provider of signs of intolerance with anticipated changes in the prescription regarding the type of formula or the rate of administration. Electrolytes and blood glucose levels should also be monitored, as ordered, for signs of imbalances.[29],[30]

Tube Irrigation

Enteral tubes are routinely flushed to maintain patency. Follow agency policy when flushing a tube. Typically, tap water and a 60-mL syringe are used to flush enteral tubes.[31] See Figure 17.8[32] for an image of a nurse irrigating an NG tube.

The steps for irrigating enteral tubes are typically the following:

- Draw the required amount of water into the 60-mL syringe and dispel excess air.

- If the tube has a clamp, close it.

- Open the distal end of the tube and connect the syringe.

- Open the clamp.

- Administer the water.

- Close the clamp.

- Remove the syringe and refill it with water if indicated.

- Repeat as needed to obtain the desired flushing volume.

- Once completed, remove the syringe, close the tube cap, and reopen the clamp.[33]

Tube Suctioning

NG tubes may be used to remove gastric content, referred to as gastric decompression. In these situations, the stomach is drained by gravity or by connection to a suction pump to prevent nausea, vomiting, gastric distension, or to wash the stomach of toxins. This procedure is commonly used for postoperative patients who have not yet regained peristalsis or for patients with a small bowel obstruction to remove the accumulation of stomach bile. It is also used in the emergency department for patients with some types of poisonings or overdoses and is commonly referred to as “pumping out the stomach.”

For patients receiving suctioning via enteral tubes, the drainage amount and color should be documented every shift.

View a supplementary YouTube video on Tube Feeding Calculations[34]

Media Attributions

- abdomen-1698565_1920

- Types and Placement of Enteral Tubes

- Enteral_feeding_tube_stylet_retracted

- Silicone_dual_lumen_stomach_tube_with_plug_removed

- tubes

- ETTubeandNGtubeMarked

- dav

- DSC_1667

- “abdomen-intestine-large-small-1698565” by bodymybody is licensed under CCO ↵

- Wireko, B. M., & Bowling, T. (2010). Enteral tube feeding. Clinical Medicine, 10(6), 616–619. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.10-6-616 ↵

- “Types and Placement of Enteral Tubes.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- “Enteral_feeding_tube_stylet_retracted.png” by Tenbergen is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Silicone_dual_lumen_stomach_tube_with_plug_removed.png” by Tenbergen is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “PEG_tube_kit.jpg” by Gilo1969 and “Percutaneous_endoscopic_gastrostomy-tube.jpg” by Pflegewiki-User HoRaMi are licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “ETTubeandNGtubeMarked.png” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Lemyze, M. (2010). The placement of nasogastric tubes. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(8), 802. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091099 ↵

- Simons, S. R., & Abdallah, L. M. (2012). Bedside assessment of enteral tube placement: Aligning practice with evidence. American Journal of Nursing, 112(2), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000411178.07179.68 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Simons, S. R., & Abdallah, L. M. (2012). Bedside assessment of enteral tube placement: Aligning practice with evidence. American Journal of Nursing, 112(2), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000411178.07179.68 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- Blumenstein, I., Shastri, Y. M., & Stein, J. (2014). Gastroenteric tube feeding: Techniques, problems and solutions. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(26), 8505–8524. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- “Open_system_enteral_feeding.jpg” by Ashashyou is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. (2017, December). Enteral feeding and medication administration. https://www.rch.org.au/rchcpg/hospital_clinical_guideline_index/Enteral_feeding_and_medication_administration/ ↵

- Blumenstein, I., Shastri, Y. M., & Stein, J. (2014). Gastroenteric tube feeding: Techniques, problems and solutions. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(26), 8505–8524. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. (2017, December). Enteral feeding and medication administration. https://www.rch.org.au/rchcpg/hospital_clinical_guideline_index/Enteral_feeding_and_medication_administration/ ↵

- Blumenstein, I., Shastri, Y. M., & Stein, J. (2014). Gastroenteric tube feeding: Techniques, problems and solutions. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(26), 8505–8524. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- “DSC_1667.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/10-2-nasogastric-tubes ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, May 18). Tube feeding nursing calculations problems dilution enteral [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/CwfJ-sQ-xOQ ↵

Overview

Asthma is a common chronic condition that affects the airways in the lungs. Individuals have different symptoms of asthma, with symptom severity ranging from “mild intermittent” symptoms to “severe persistent” symptoms. Asthma can be well-controlled by taking prescription medication and avoiding specific exposures that trigger an asthma attack.[1],[2]

Pathophysiology

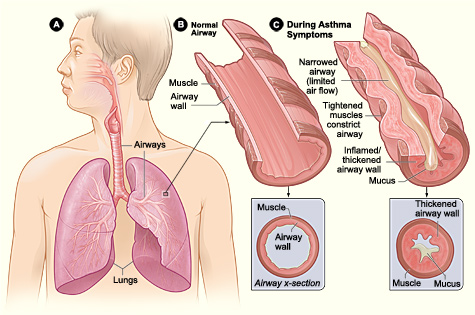

Asthma is caused by chronic inflammation in the airways, resulting in narrowed air passages. Individuals with asthma also experience bronchoconstriction that tightens the smooth muscle surrounding the airways, further limiting airflow.[3] When individuals with asthma are experiencing symptoms of bronchoconstriction and inflammation, they may also have increased mucus, further blocking their airways. See Figure 6.18[4] for an illustration of asthma symptoms.

Asthma causes repeated episodes of wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and nighttime or early morning coughing. Between these episodes, many individuals with asthma are asymptomatic.[5]

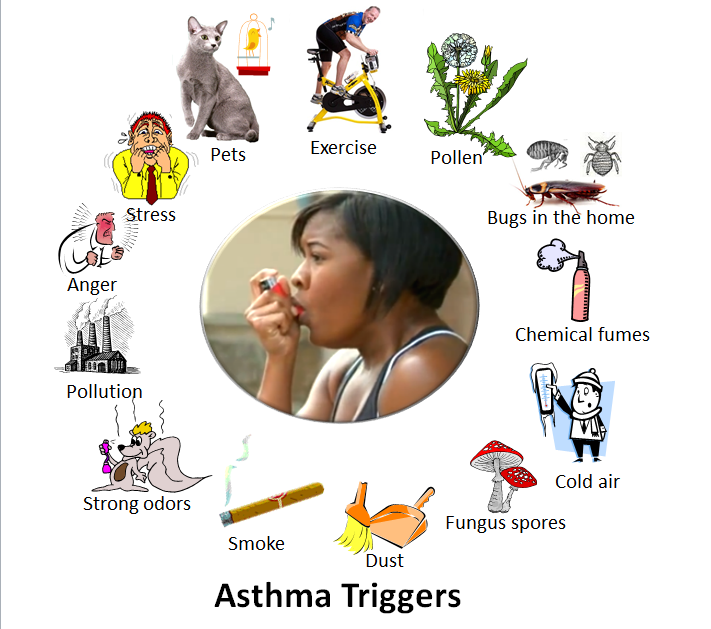

Asthma can occur at any age and can be triggered by a variety of causes such as allergens, exercise, tobacco smoke, air pollutants, gastroesophageal reflux disease, cold air, and extreme emotion.[6] See Figure 6.19[7] for an illustration of common asthma triggers. Nurses teach clients diagnosed with asthma to recognize their triggers and avoid them to prevent asthma attacks.

There are two major classes of medications used to control asthma, referred to as quick-relief and long-term control. Quick-relief inhalers like albuterol and ipratropium are used to control symptoms that occur during an asthma attack. Long-term control medicines help prevent asthma attacks, but they do not resolve symptoms that occur during an asthma attack.[8] Asthma medications are further discussed in the “Medical Interventions” subsection later in this section.

Health Disparities Related to Asthma

The burden of asthma in the United States falls disproportionately on Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native people. These groups have the highest asthma rates, deaths, and hospitalizations. For example, when compared to White Americans, Black Americans are three times more likely to die from asthma.[9]

Racial and ethnic disparities in asthma are caused by complex factors, including these factors[10]:

- Social determinants such as socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood environment, employment, social support networks, and access to health care

- Structural determinants such as insurance and health care policies

- Biological determinants such as genetics

- Behavioral determinants such as tobacco use and adherence to prescribed medications

These strategies have been developed to improve asthma care in at risk populations[11]:

- Improving implementation of evidence-based guidelines, care, and treatments by expanding specialist care coverage, lowering copays, expanding eligibility criteria, and reducing barriers to treatment.

- Reducing exposure to pollution by strengthening clean air policies, reducing transportation-related emissions, restricting zoning of polluting sources, and transitioning to a clean energy economy.

- Providing personalized, culturally appropriate asthma action plans using the client’s and caregivers’ preferred language and learning styles (i.e., visual, audio, or kinesthetic).

- Improving trust in health care by engaging diverse clients, families, and community partners as early as possible when developing asthma prevention and care programs.

Read additional information in the full Asthma Disparities in America Report by the Allergy and Asthma Foundation of America.

Assessment

Clinical manifestations of asthma are related to the inflammation and bronchoconstriction that occur in the airways. Individuals with well-controlled asthma may exhibit few or no symptoms. Signs and symptoms of individuals with asthma that is not well-controlled are as follows[12]:

- Wheezing

- Dyspnea

- Chest tightness

- Nighttime or early morning coughing

- Awakening at night with asthma symptoms

Severity of signs and symptoms during asthma attacks are further discussed in the “Asthma Action Plan” area under the "Medical Interventions" subsection.

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing for asthma involves several clinical assessment and lung function tests such as the following[13],[14],[15]:

- Peak flow monitoring: Peak flow monitoring is used by clients with moderate to severe asthma to monitor and manage their asthma symptoms. It involves a handheld device called a peak flow meter that measures the rate of air that can be forcefully breathed out of the lungs. This measurement is called a peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). A baseline PEFR is established for an individual diagnosed with asthma when their symptoms are well-controlled. Ranges of PEFRs are included on the client’s Asthma Action Plan to help determine if they are in the Green, Yellow, or Red Zone. See Figure 6.20[16] for an image of a peak flow meter. Additional information about teaching clients how to use a peak flow meter is discussed under “Health Teaching” in the “Nursing Interventions” subsection.

- Spirometry: Read more about spirometry in the “Diagnostic Testing” subsection of the “General Respiratory System Assessment and Interventions” section. Decreased FEV1 compared to normal reference ranges, as well as a significant increase in FEV1 after bronchodilator administration, indicates asthma.

- Methacholine Challenge: A methacholine challenge test is used when other tests are inconclusive for diagnosing asthma. Methacholine is a bronchoconstrictor that is inhaled to measure airway responsiveness.

- Allergen Testing: Allergen testing may be conducted to identify specific allergens that can trigger an individual’s asthma symptoms.

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing priorities for clients with asthma involve addressing dyspnea and inadequate oxygenation, promoting self-management and positive coping, and managing anxiety that is associated with asthma attacks.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with asthma are formulated based on the client's assessment data, medical history, and specific needs. These nursing diagnoses guide the development of individualized care plans and interventions. Common nursing diagnoses include the following[17]:

- Ineffective Airway Clearance

- Anxiety

- Readiness for Enhanced Health Self-Management

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes for individuals diagnosed with asthma are as follows:

- The client will demonstrate accurate use of their prescribed inhalers by the end of the teaching session.

- The client will demonstrate accurate measurement of their peak flow reading (PEFR) by the end of the teaching session.

- The client and/or family member will verbalize how to accurately use the asthma action plan to manage worsening symptoms of asthma by the end of the teaching session.

- The client will verbalize how to use relaxation techniques to help manage feelings of anxiety when feeling short of breath by the end of the teaching session.

- The client will verbalize at least two personal triggers that contribute to worsening asthma symptoms by the end of the teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions for asthma aim to achieve effective symptom control, improve lung function, prevent exacerbations, and enhance the client's quality of life. These interventions are prescribed by health care providers based on the individual’s asthma severity, current symptoms related to their baseline, their asthma action plan, and specific triggers.

Common medical interventions used to address chronic asthma include lifestyle modifications, medication management, immunizations, asthma action plans, and surgical treatment.

Lifestyle Modifications

Clients with asthma are advised to identify and minimize exposure to allergens or irritants that trigger their asthma, such as pollen, dust mites, or pet dander. They are also encouraged to receive flu, COVID, and pneumococcal vaccines to reduce the risk of respiratory infections that can trigger asthma exacerbations. For clients who smoke, quitting is strongly recommended to reduce exposure to irritants. For clients who don’t smoke, exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke should be avoided.

Medication Therapy

The goal of asthma therapy is to control asthma symptoms with the least amount of medication and minimal risk for adverse effects. A “stepwise approach to therapy” is used by health care providers in determining the type of medication(s) prescribed, their dosage(s), and frequency of administration. These medications are increased as necessary and decreased when possible. Because asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways with recurrent exacerbations, medication therapy focuses on long-term suppression of inflammation to prevent exacerbations. See Figure 6.21[18] for an illustration of the stepwise approach to asthma therapy.[19]

As illustrated in Figure 6.21, several types of medication are prescribed to control asthma symptoms and prevent asthma attacks, as well as additional medications like anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies and immunomodulators[20],[21],[22],[23]:

- Inhaled Bronchodilators

- Short-Acting Beta-Agonists (SABA): SABAs such as albuterol or ipratropium relax airway smooth muscles and rapidly relieve bronchoconstriction. SABAs are used as “rescue” medications during asthma attacks to quickly relieve acute symptoms.

- Long-Acting Beta-Agonists (LABA): LABAs such as salmeterol provide long-term bronchodilation.

- Inhaled Corticosteroids: Inhaled corticosteroids, such as fluticasone and budesonide, are anti-inflammatory medications that reduce airway inflammation. They are used for long-term prevention and management of asthma symptoms.

- Combination Inhalers With Inhaled Corticosteroid and Long-Acting Beta-Agonists (ICS-LABA): ICS-LABA combination inhalers such as fluticasone/salmeterol, commonly known by the brand name Advair, reduce airway inflammation and promote bronchodilation to prevent asthma symptoms.

- Oral or Intravenous Corticosteroids: A short course of an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisone, may be prescribed for clients in the “Yellow Zone” to reduce inflammation and swelling in the airways. Clients receiving emergency care for an acute asthma attack may receive intravenous administration of corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone, for rapid reduction of airway swelling and inflammation.

- Leukotriene Modifiers: Oral leukotriene modifiers such as montelukast are used for long-term prevention of asthma symptoms and reduction of inflammation and bronchoconstriction by targeting leukotrienes that are involved in an allergic response related to asthma.

- Cromolyn: Cromolyn reduces the release of inflammatory mediators, including histamine and leukotrienes that cause bronchoconstriction and allergic symptoms that can trigger asthma.

- Methylxanthine: Methylxanthine, commonly known as theophylline, is an older medication used to treat asthma that may be prescribed if other alternatives are not effective. It decreases inflammation and causes bronchodilation but requires close monitoring of serum levels because it has a narrow range between therapeutic and toxic levels.

- Anti-IgE Monoclonal Antibodies: Monoclonal antibodies that target IgE, such as omalizumab, can be effective in reducing acute asthma exacerbations and improving quality of life for clients with severe asthma who have an allergic response component.[24]

- Immunomodulators: Mepolizumab is a biologic therapy that regulates levels of eosinophils, blood cells that often trigger asthma in individuals with an allergic component.

- Oxygen Therapy: Oxygen therapy is not a standard treatment for asthma management, but it may be used during acute asthma exacerbations for clients in the "Red Zone."

To read additional information about common medication classes used to treat asthma, visit the “Respiratory” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Immunizations

Clients diagnosed with asthma are encouraged to remain up-to-date on recommended vaccinations, including influenza, pneumococcal (pneumonia), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), pertussis (Tdap), and COVID vaccines.

Review current information about "Recommended Vaccines by Age" from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Asthma Action Plans

An individual diagnosed with asthma should have a written “Asthma Action Plan” from their health care provider that advises them how to self-manage their asthma at home. Asthma action plans have three zones, referred to as green, yellow, and red.

Green Zone

Individuals whose asthma symptoms are well-controlled are considered to be in the "Green Zone." This means they don’t have a cough, wheeze, chest tightness, or shortness of breath during the day or night, and they can do their usual activities. If they use a peak flow meter to monitor and manage their asthma, their peak flow reading is at least 80% of their personal best.[25] Peak flow meters are further discussed under the “Diagnostic Testing” subsection.

Individuals in the "Green Zone" should continue taking their asthma medications as prescribed. If exercise is an asthma trigger for an individual, their asthma action plan may advise quick-relief medication before exercising to prevent an asthma attack (sometimes referred to as “pre-treatment”).

Yellow Zone

Individuals are considered to be in the "Yellow/Caution Zone" when their asthma symptoms are worsening, including one or more of the following[26]:

- Coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, or shortness of breath

- Waking at night due to asthma

- Able to do some, but not all of their usual activities

If a client uses a peak flow meter to monitor and manage their asthma, peak flow readings of 50 to 79% of their personal best indicate they are in the "Yellow Zone." Individuals in the "Yellow Zone" should take their prescribed asthma medications as listed in the "Green Zone" of their asthma action plan, plus additional medications as described in the "Yellow Zone," such as a quick-relief inhaler and possibly an oral corticosteroid. They should also call their doctor as instructed.[27] Individuals who experience "Yellow Zone" symptoms two or more times per week should contact their health care provider for a follow-up appointment because this frequency means their asthma is not considered “well-controlled,” and they are at risk for a severe asthma attack.[28]

Red Zone

Individuals are considered to be in the "Red/Medical Alert Zone" if they are experiencing asthma symptoms that are worsening without resolution. Severe asthma episodes can be life-threatening and require emergency care. Signs and symptoms of an asthma emergency that requires urgent medical care include one or more of the following criteria[29]:

- Feeling very short of breath

- Symptoms are not relieved by quick-relief medicines

- Unable to do usual activities

- Same or worsening symptoms after 24 hours in Yellow Zone

Infants, toddlers, and children may have different asthma emergency signs and symptoms than adults. Additional signs and symptoms of a severe asthma episode in infants, toddlers, and children include the following[30]:

- Nasal flaring (i.e., nostrils are opening widely)

- Exaggerated belly breathing

- Failing to recognize or respond to their parents

- Irritable, agitated, and/or sluggish

- Nasal grunting on expiration

Individuals in the "Red Zone" should immediately take a quick-relief medication and an oral corticosteroid and then call their health care provider. If they are still in the "Red Zone" after 15 minutes AND they have not reached their provider, they should go to the emergency room or call an ambulance. If at any time they experience trouble walking and talking due to shortness of breath or their lips or fingernails become cyanotic, they should take another dose of quick-relief medication and immediately call 911 or go to the emergency room.[31]

Status Asthmaticus

Status asthmaticus is a severe and life-threatening asthma attack that is unresponsive to standard treatments such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids. It is a medical emergency that requires immediate intervention, typically in an emergency department or by a medical response team.

Status asthmaticus is characterized by the following:

- Severe airway obstruction

- Rapid and labored breathing

- Worsening hypoxemia

- Decreased mental alertness

- Ineffective bronchodilator response

- Cyanosis

- Silent chest - minimal or no breath sounds heard on auscultation

- Exhaustion

Treatment for status asthmaticus typically involves the following[32],[33],[34]:

- Oxygen Therapy: Oxygen is administered to quickly resolve hypoxemia and improve oxygen levels in the blood.

- Systemic Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) are administered intravenously to quickly reduce airway inflammation and swelling.

- Continuous Nebulized Bronchodilators: High-dose bronchodilators are continuously administered, such as albuterol nebulizers.

- Magnesium Sulfate: Intravenous magnesium sulfate may be administered to relax bronchial smooth muscles.

- Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation: In severe cases when hypoxia and hypercapnia are present, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary. This procedure is typically performed by respiratory therapists, paramedics, physicians, or anesthesiologists.

- Continuous Monitoring of Vital Signs and ECG: Continuous monitoring of vital signs and oxygen saturation levels and an electrocardiogram (ECG) are performed to closely monitor the client's condition because the hypoxia can trigger arrhythmias.

View or download the most recent copy of an Asthma Action Plan document from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.[35]

Surgical Interventions

Clients with severe asthma for whom conventional treatment is not effective may undergo bronchial thermoplasty. This procedure is performed during a bronchoscopy and delivers heat to the muscles surrounding the airways to reduce smooth muscle mass and prevent them from narrowing.[36],[37],[38]

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for asthma are aimed at symptom management and facilitating overall respiratory health through medication management, health teaching, and psychosocial support.

Medication Management

Nurses safely administer prescribed medications, evaluate their effectiveness, and monitor for potential side effects. They provide teaching about the purpose and use of medications as further described under the “Health Teaching” subsection.

Dyspnea Management

Nurses implement and teach strategies for managing dyspnea during asthma attacks, in addition to administering medication. For example, sitting upright or using tripod positioning can help with lung expansion, and pursed-lip breathing reduces air trapping that can occur during an asthma attack. Review enhanced breathing techniques in the “General Nursing Interventions Related to Respiratory Alterations” subsection earlier in this chapter.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide comprehensive asthma education to clients and their family members, caregivers, or significant others. Teaching focuses on symptoms of asthma, triggers of their asthma attacks, how to use their prescribed medications according to their asthma action plan, and when to contact their provider with worsening symptoms. See teaching topics related to the asthma action plan in the following box.

A Closer Look: Health Teaching Regarding Asthma Action Plans[39]

Clients with asthma should have a written action plan developed in collaboration with their health provider. If the client does not have a written action plan, the nurse should advocate for one. Nurses provide education to the client and their family members regarding how to use the asthma action plan and check for understanding.

Green Zone (Good Control): Teaching topics include the following:

- Using long-term control medications as prescribed.

- Identifying and avoiding triggers.

- Monitoring peak flow readings.

- Premedicating before exercise, if exercise is a trigger.

Yellow Zone (Caution): Teaching topics include the following:

- Understanding the symptoms that indicate the Yellow Zone.

- Using quick-relief medications and oral corticosteroids.

- Monitoring peak flow readings.

- Notifying the health care provider.

Red Zone (Danger): Teaching topics include the following:

- Knowing the symptoms that indicate the Red Zone.

- Understanding the actions to take if in the Red Zone.

- Knowing when to call the health care provider and/or seek emergency medical care.

It is helpful for the client to have written materials during and after the teaching session. See information on free handouts in the following box.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute provides free resources that can be downloaded and printed for clients. Here are a few key handouts that can be used during health teaching sessions:

- Monitoring Your Asthma with instructions on how to use a peak flow meter

- How to Use a Metered-Dose Inhaler

- How to Use a Nebulizer

- How to Use a Dry Powder Inhaler

Psychosocial Support

Nurses offer psychosocial support to clients with chronic disease to help them cope with the challenges of managing their symptoms and achieving quality of life.

It is common for clients with asthma and their family members to experience anxiety when dyspnea occurs. Anxiety can worsen dyspnea because it stimulates rapid, shallow breathing. During an asthma attack, in addition to implementing interventions to promote oxygenation, the nurse maintains a calm environment, stays with the client, and encourages relaxation techniques to decrease anxiety. Nurses can demonstrate and encourage the use of focused breathing, guided imagery, and progressive relaxation. Music therapy, based on the client's preferences, may also be helpful to promote relaxation. After an asthma attack has resolved, nurses teach clients and their family members how to use relaxation techniques to help manage anxiety while also using their asthma action plan to manage their respiratory symptoms.[40]

Nurses also assess the coping skills, available resources, and social support for clients with asthma. By reinforcing the asthma action plan, nurses focus on positive coping strategies and self-monitoring techniques that reaffirm the client’s and the family’s ability to deal with the chronic illness. Effective resources and support can reduce asthma symptoms and result in fewer unscheduled health care visits, fewer activity limitations, and improved school/work attendance.[41],[42]

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

![]() RN Recap: Asthma

RN Recap: Asthma

View a brief YouTube video overview of asthma.[43]