Identifying Stress in Self

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) and Amy Ertwine

Health care professionals must recognize emerging signs of stress that may result from job demands and the nature of health care work. There are a variety of ways that stress can manifest itself. Taking action early can help to prevent workplace burnout. Burnout can be manifested physically and psychologically with a loss of motivation for one’s work. Nurses and other health care professionals must mitigate stress and burnout to sustain engagement with their profession. Failure to acknowledge the implications of professional burnout only exacerbates the cycle as stressors are transferred to remaining team members and colleagues, resulting in the potential for attrition and turnover.

Although the term “stress” often has negative connotations, it is important to remember that not all stress is considered harmful. Normal stress, also referred to as “eustress,” does not have lasting consequences and is successfully managed by the individual who is experiencing it.[1] Normal stress, when successfully managed, can increase awareness and focus, resulting in feelings of motivation and competence in the individual who is experiencing it. For example, normal stress may be experienced by a nursing student as they organize their weekly planner specifying time for class, study time, work shifts, or meeting with friends. Although the calendar looks busy, the student can use the stress resulting from a “time-constrained schedule” to motivate oneself to be efficient in completing tasks. This student may feel great satisfaction as they cross off tasks on the “to-do” list. Hopefully, as task achievement occurs, the student transitions from feelings of stress to feelings of empowerment.

Conversely, harmful stress, also referred to as “distress,” occurs when stress is not adequately self-managed. Harmful stress is reflected by physical, mental, and behavioral manifestations.[2] See Figure 12.2[3] for an illustration of an individual experiencing harmful stress. Harmful stress can lead to burnout and exhaustion, and if left unaddressed, it can have significant health implications for the individual experiencing it. Let’s return to the example of the nursing student reviewing their busy schedule. Harmful stress can be experienced by a student looking at their busy weekly schedule and feeling overwhelmed and exhausted. Rather than focusing on manageable tasks and crossing items off the list, this student is reluctant to take action and feels distress regarding where to begin. The student demonstrating harmful stress may struggle with overwhelming fatigue, irritability, and may feel overwhelmed with feelings of inadequacy at one’s ability to meet the task requirements.

Harmful stress can impact the employment setting as well. It can damage staff engagement, cause significant physical manifestations, and impede the ability of the employee to safely perform work. Harmful stress can quickly result in the breakdown of collegial relationships and also influence the overall practice environment. Potential signs of harmful stress are described in Table 12.3.

Table 12.3. Harmful Stress: Physical, Mental, & Behavioral Manifestations[4]

| Physical | Headache

Joint discomfort Sleep disturbance Cardiac abnormality (e.g., heart rate, rhythm changes) Increased blood pressure Dry mouth Indigestion Constipation or diarrhea Excessive sweating Dizziness Tremors |

|---|---|

| Mental | Anger

Irritability Mood changes Depression Conflict with friends, family members, coworkers Isolation of self from others Reduced self-confidence |

| Behavioral | Increased alcohol consumption

Smoking or drug use Overeating or loss of appetite Increased arguments with coworkers Increased errors in the workplace |

Nurses and health care professionals should be mindful of the physical, mental, and behavioral manifestations of harmful stress so prompt action can be taken when signs begin to occur. Harmful stress must be addressed early so it does not continue to evolve and lead to career burnout. Additionally, stress can have significant implications beyond one’s career. An individual’s physical and emotional health and well-being are strongly aligned with positive stress management. Harmful stress that goes unaddressed can lead to unresolved physical ailments, deterioration in mental and physical well-being, and the breakdown of familial relationships. The negative impact of harmful stress can be difficult to overcome after it has taken hold of an individual.

It can be helpful to mindfully gauge how one is handling stress on a routine basis. See the link to the Perceived Stress Scale in the following box.

Gauge your current level of stress using the State of New Hampshire’s Perceived Stress Scale.

Stressors Resulting From the COVID-19 Pandemic

In addition to the inherent stressors that can occur in health care settings as a result of normal job-related tasks and demands, unique challenges and stressors have occurred for nurses as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. See Figure 12.3[5] for an image of a COVID care provider. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 highlights the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the profession. The COVID pandemic has placed extraordinary demands on nurses as they try to meet ever-expanding health care challenges placed on them. Hospitals are continuously overcrowded and needed medical equipment can be sparse.[6] Nurses are asked to provide frontline care to infectious clients with transmission-based precautions in isolation rooms.[7] These nurses then return to their home environments, hoping that they do not spread infection to their families while supporting the needs of the family unit. These continuous job and life stressors compound the physical and psychological demands on nurses. With little respite care for themselves, nurses are at risk for the impact of compounding stressors on their own health.

Read a meta-analysis about interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline professionals during a pandemic.

Media Attributions

- 4347213145_a5b4a6ac40_k (2)

- unnamed (2)

- Bamber, M. R. (2011). Overcoming your workplace stress: A CBT-based self-help guide. Routledge. ↵

- Bamber, M. R. (2011). Overcoming your workplace stress: A CBT-based self-help guide. Routledge. ↵

- “4347213145_bec129a6ae.jpg” by Michael Clesle is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 ↵

- Bamber, M. R. (2011). Overcoming your workplace stress: A CBT-based self-help guide. Routledge. ↵

- “49855067292_d521d20931_o-e1626806176568.jpg” by Ted Eytan is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982 ↵

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982 ↵

Answer Key to Learning Activities

- C - Heart Failure (Rationale: The patient's symptoms indicate fluid volume overload and reflect a clinical diagnosis of heart failure.)

- B - Stay with the patient and notify the HCP of the ECG results (Rationale: The patient's cardiac rhythm change is reflective of an abnormality. This change should be communicated to the health care provider.)

Answers to H5P interactive elements are given within the interactive element.

Answer Key to Critical Thinking Activities

1. Correct Order: 2 - Stop the IV infusion, 1 - Discontinue the IV, 3 - Elevate the affected side, 4 - Document the findings

Answers to interactive elements are given within the interactive element.

Blood glucose monitoring is performed on patients with diabetes mellitus and other conditions that cause elevated blood sugar levels. Diabetes mellitus is a common medical condition that affects the body’s ability to produce insulin in the pancreas and use insulin at the cellular level. There are two types of diabetes mellitus, type 1 and type 2. Type 1 diabetes mellitus is an autoimmune disease that damages the beta cells of the pancreas so they do not produce insulin; thus, synthetic insulin must be administered by injection or infusion. It typically begins in childhood or adolescence. Type 2 diabetes mellitus accounts for approximately 95 percent of all cases and is highly correlated with obesity and inactivity. During type 2 diabetes, the cells of the body become resistant to the effects of insulin, and the pancreas increases its production of insulin. However, over time, the pancreas may no longer be able to produce insulin. In many cases, type 2 diabetes can be managed by moderate weight loss, regular physical activity, and a healthy diet. However, if blood glucose levels cannot be controlled with healthy lifestyle choices, oral diabetic medication is prescribed and eventually, the administration of insulin may be required.[1] Prediabetes is a medical condition where blood sugar levels are higher than normal, but not high enough yet to be diagnosed as type 2 diabetes. Approximately one in three American adults have prediabetes. Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes that occurs during pregnancy in women who did not have diabetes before they were pregnant.

Diabetic patients require frequent blood glucose monitoring to administer customized medication therapy to prevent long-term complications from occurring. Hospitalized patients who do not have diabetes may also require frequent blood glucose monitoring due to elevations that can occur as a result of the stress of hospitalization, surgical procedures, and side effects of medications. Additionally, patients receiving enteral feedings typically have their blood glucose monitored every six hours. Health care providers prescribe the frequency of blood glucose monitoring; testing is typically performed before meals and at bedtime. For some patients, a standardized sliding-scale insulin protocol may be prescribed with instructions on the medication administration record (MAR) for administration of insulin based on their blood glucose results.[2],[3] See Table 19.2 for an example of a sliding-scale insulin protocol.

Table 19.2 Sample Sliding-Scale Insulin Protocol

Instructions: Check patient’s blood sugar before meals, at bedtime, and as needed for symptoms of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Use the following table to administer insulin lispro PRN.

| Blood Sugar Range | Lispro Insulin Instructions |

|---|---|

| Less than 70 | Hold all insulin and initiate hypoglycemia protocol. |

| 70-150 | 0 units |

| 151-174 | 2 units |

| 175-199 | 4 units |

| 200-224 | 6 units |

| 225-249 | 8 units |

| 250-274 | 10 units |

| 275-299 | 12 units |

| Greater than 300 | Administer 14 units and call the provider. |

Hypoglycemia

When caring for patients with diabetes mellitus and monitoring their blood glucose readings, it is important to continually monitor for signs of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia is defined as blood sugar readings less than 70 and signs and symptoms such as the following:

- Shakiness

- Feeling nervous or anxious

- Sweating, chills, and clamminess

- Irritability or impatience

- Confusion

- Fast heartbeat

- Feeling light-headed or dizzy

- Hunger

- Nausea

- Color draining from the skin (pallor)

- Feeling sleepy

- Feeling weak or having no energy

- Blurred/impaired vision

- Tingling or numbness in the lips, tongue, or cheeks

- Headaches

- Coordination problems or clumsiness

- Nightmares or crying out during sleep

- Seizures[4]

A low blood sugar level triggers the release of epinephrine (adrenaline), the “fight-or-flight” hormone. Epinephrine causes the symptoms of hypoglycemia such as a rapid heartbeat, sweating, and anxiety. If a patient’s blood sugar level continues to drop, the brain has impaired functioning. This may lead to seizures and a coma.[5]

If a nurse suspects hypoglycemia is occurring, a blood sugar reading should be obtained, and appropriate actions taken. Most agencies have a hypoglycemia protocol based on the “15-15 Rule.” The 15-15 Rule is to provide 15 grams of carbohydrate and recheck the blood glucose after 15 minutes. If the reading is still below 70 mg/dL, another serving of 15 grams of carbohydrate should be provided and the process continued until the blood sugar is above 70 mg/dL. Fifteen grams of carbohydrate includes options like 4 ounces of juice or regular soda, hard candy, or glucose tablets. If a patient is experiencing severe hypoglycemia and cannot swallow, a glucagon injection or intravenous administration of dextrose may be required.[6]

Hyperglycemia

Hyperglycemia is defined as elevated blood glucose and often causes signs and symptoms such as frequent urination and increased thirst. Hyperglycemia occurs when the patient’s body does not produce enough insulin or cannot use the insulin properly at the cellular level. There are many potential causes of hyperglycemia, such as not receiving enough medication to effectively control blood glucose, eating more than planned, exercising less than planned, or increased stress from an illness, surgery, hospitalization, or other life events.

If a patient's blood glucose is greater than 240 mg/dL, their urine is typically checked for ketones. Ketones indicate a condition called ketoacidosis may be occurring. Ketoacidosis occurs in patients whose pancreas is no longer creating insulin, so fats are broken down for energy and waste products called ketones are produced. If the kidneys cannot effectively eliminate ketones in the urine, they build up in the blood and cause ketoacidosis. Ketoacidosis is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate notification of the provider for treatment. Symptoms of ketoacidosis include fruity-smelling breath, nausea, vomiting, very dry mouth, and shortness of breath. Treatment of ketoacidosis often requires the administration of intravenous insulin while the patient is closely monitored in a critical care inpatient unit.[7]

For more information about diabetes mellitus, measuring blood sugar levels, and diabetic medications, visit the "Endocrine" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Glucometer Use

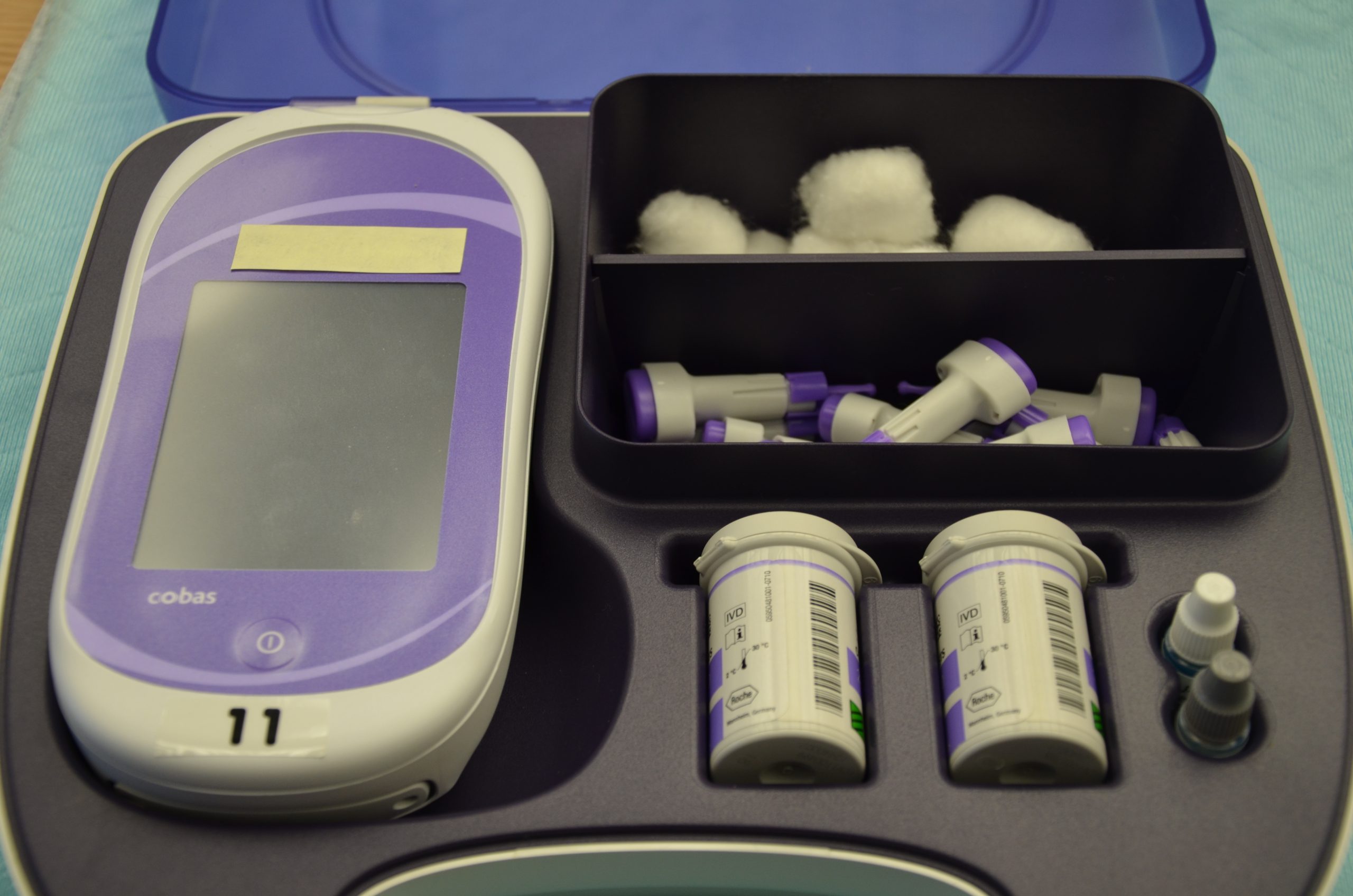

It is typically the responsibility of a nurse to perform bedside blood glucose readings, but in some agencies, this procedure may be delegated to trained nursing assistants or medical assistants. See Figure 19.1[8] for an image of a standard bedside glucometer kit that contains a glucometer, lancets, reagent strips, and calibration drops. Prior to performing a blood glucose test, read the manufacturer’s instructions and agency policy because they may vary across devices and sites. Ensure the glucometer has been calibrated per agency policy.[9]

Before beginning the procedure, determine if there are any conditions present that could affect the reading. For example, is the patient fasting? Has the patient already begun eating? Is the patient demonstrating any symptoms of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia? Keep your patient safe by applying your knowledge of diabetes, the medication being administered, and the uniqueness of the patient to make appropriate clinical judgments regarding the procedure and associated medication administration.[10]

See the “Checklist for Blood Glucose Monitoring” for details regarding the procedure. It is often important to keep the patient’s hand warm and in a dependent position to promote vasodilation and obtain a good blood sample. If necessary, warm compresses can be applied for 10 minutes prior to the procedure to promote vasodilation. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions to prepare the glucometer for measurement. After applying clean gloves, clean the patient's skin with an alcohol wipe for 30 seconds, allow the site to dry, and then puncture the skin using the lancet. See Figure 19.2[11] for an image of performing a skin puncture using a lancet.

If needed, gently squeeze above the site to obtain a large drop of blood. Do not milk or massage the finger because it may introduce excess tissue fluid and hemolyze the specimen. Wipe away the first drop of blood and use the second drop for the blood sample. Follow agency policy and manufacturer instructions regarding placement of the drop of blood for absorption on the reagent strip. See Figure 19.3[12] for an image of a nurse absorbing the patient’s drop of blood on the reagent strip. Timeliness is essential in gathering an appropriate specimen before clotting occurs or the glucometer times out.

Cleanse the glucometer and document the blood glucose results according to agency policy. Report any concerns about patient symptoms or blood sugar results according to agency policy.

Life Span Considerations

Blood glucose samples should be taken from the heel of newborns and infants up to the age of six months. When obtaining a sample from the heel, the sample is taken from the medial or lateral plantar surface.