8.2 Oxygenation Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Review of Anatomy and Physiology

Several body systems contribute to a person’s oxygenation status, including the respiratory, cardiovascular, and hematological systems. The anatomy and physiology of these systems are reviewed in the following sections.

Respiratory System

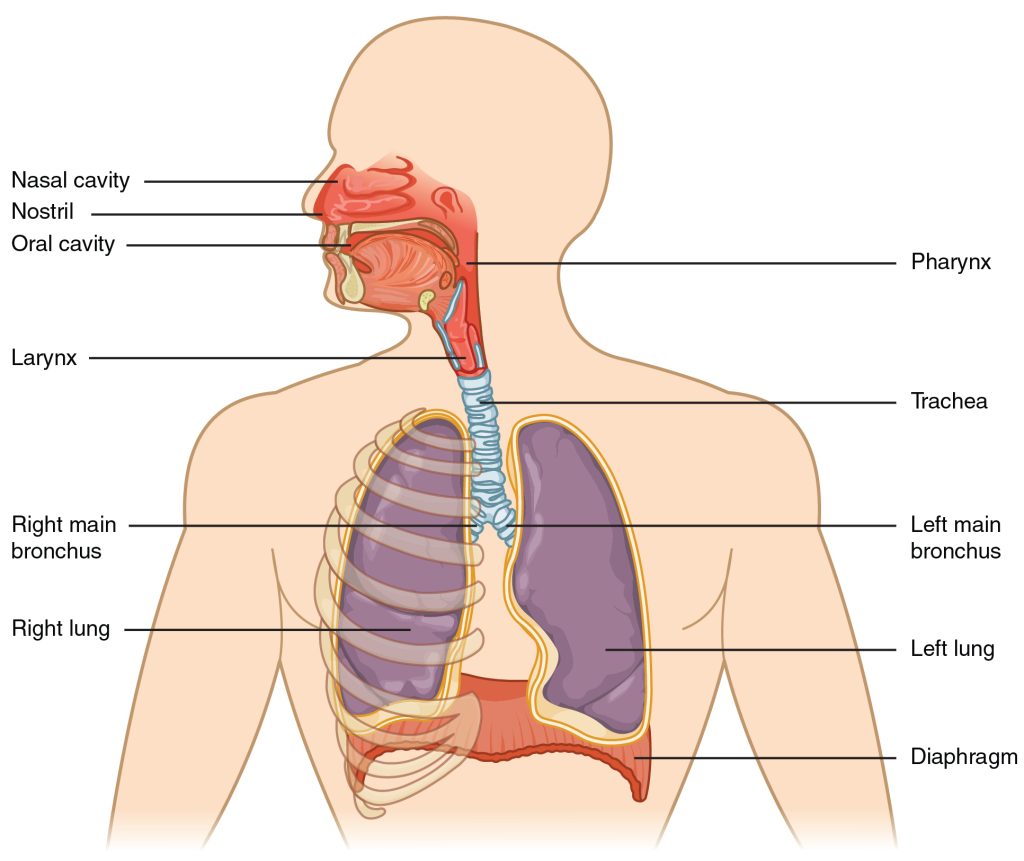

The major organs of the respiratory system function primarily to provide oxygen to body tissues for cellular respiration, remove the waste product carbon dioxide, and help maintain acid-base balance.[1] See Figure 8.1 for an illustration of the major structures of the respiratory system.[2]

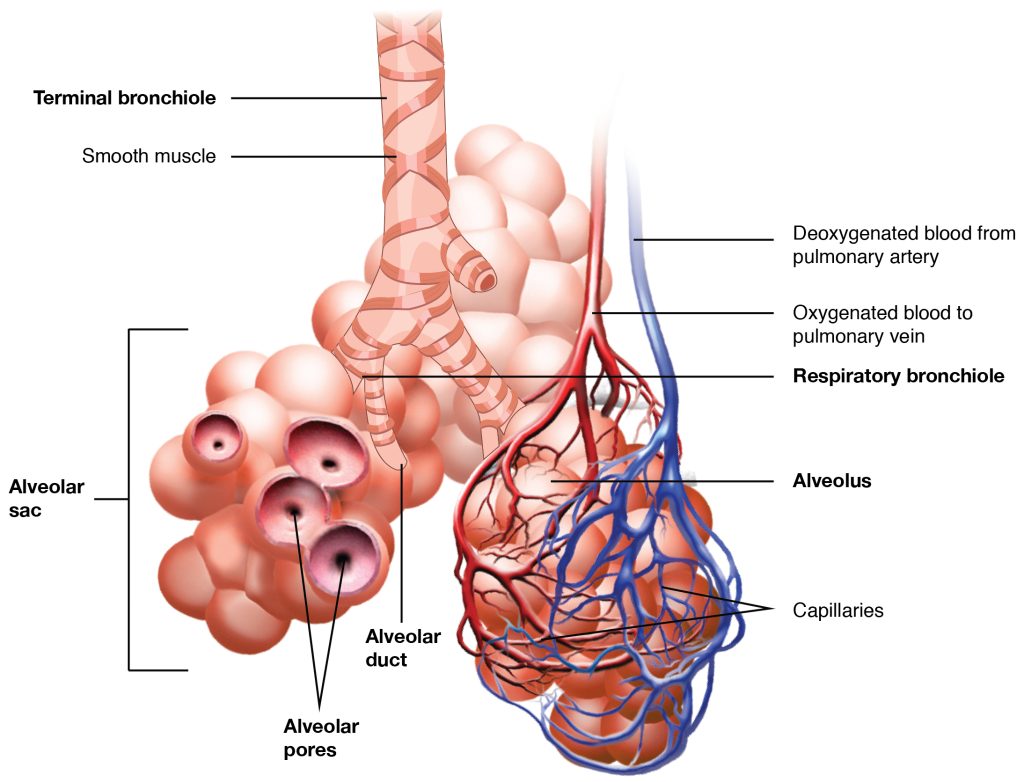

The purpose of the respiratory system is to perform gas exchange. Gas exchange refers to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the alveoli and the pulmonary capillaries, also called respiration. During external respiration, at the alveolar level, oxygen from the air we breathe diffuses into the blood, and carbon dioxide diffuses out of the blood where it can be exhaled. Throughout the rest of the body, gas exchange also occurs between the systemic capillaries and body cells/tissues, called internal respiration. During internal respiration, oxygen diffuses out of the systemic capillaries and into body cells/tissues, and carbon dioxide diffuses from the cells/tissues into the systemic capillaries where it is carried to the lungs. It is through this process that cells in the body are oxygenated and carbon dioxide, the waste product of cellular respiration, is removed from the body.[3] See Figure 8.2a[4] for an illustration of alveoli.

To achieve gas exchange, the structures of the respiratory system create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation. Pulmonary ventilation provides air to the alveoli for this gas exchange process.

Lung sounds are caused by the movement of air from the trachea to the bronchioles to the alveoli and can be impacted by the presence of sputum, bronchoconstriction, or fluid in the alveoli. Examples of adventitious sounds are rhonchi (coarse crackles), rales (fine crackles), wheezes, stridor, and pleural rub[5]:

- Rhonchi, also referred to as coarse crackles, are low-pitched, continuous sounds heard on expiration that are a sign of turbulent airflow through mucus in the large airways.

- Rales, also called fine crackles, are popping or crackling sounds heard on inspiration. They are associated with medical conditions that cause fluid accumulation within the alveolar and interstitial spaces, such as heart failure or pneumonia. The sound is similar to that produced by rubbing strands of hair together close to your ear.

- Wheezes are whistling noises produced when air is forced through airways narrowed by bronchoconstriction or mucosal edema. For example, clients with asthma commonly have wheezing.

- Stridor is heard only on inspiration. It is associated with obstruction of the trachea/upper airway.

- Pleural rub sounds like the rubbing together of leather and can be heard on inspiration and expiration. It is caused by inflammation of the pleura membranes that results in friction as the surfaces rub against each other.

Several respiratory conditions can affect a client’s ability to maintain adequate ventilation and respiration, and there are several medications used to enhance a client’s oxygenation status.

Review common respiratory disorders and common respiratory medications in the “Respiratory” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Review how to perform a respiratory assessment in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Cardiovascular System

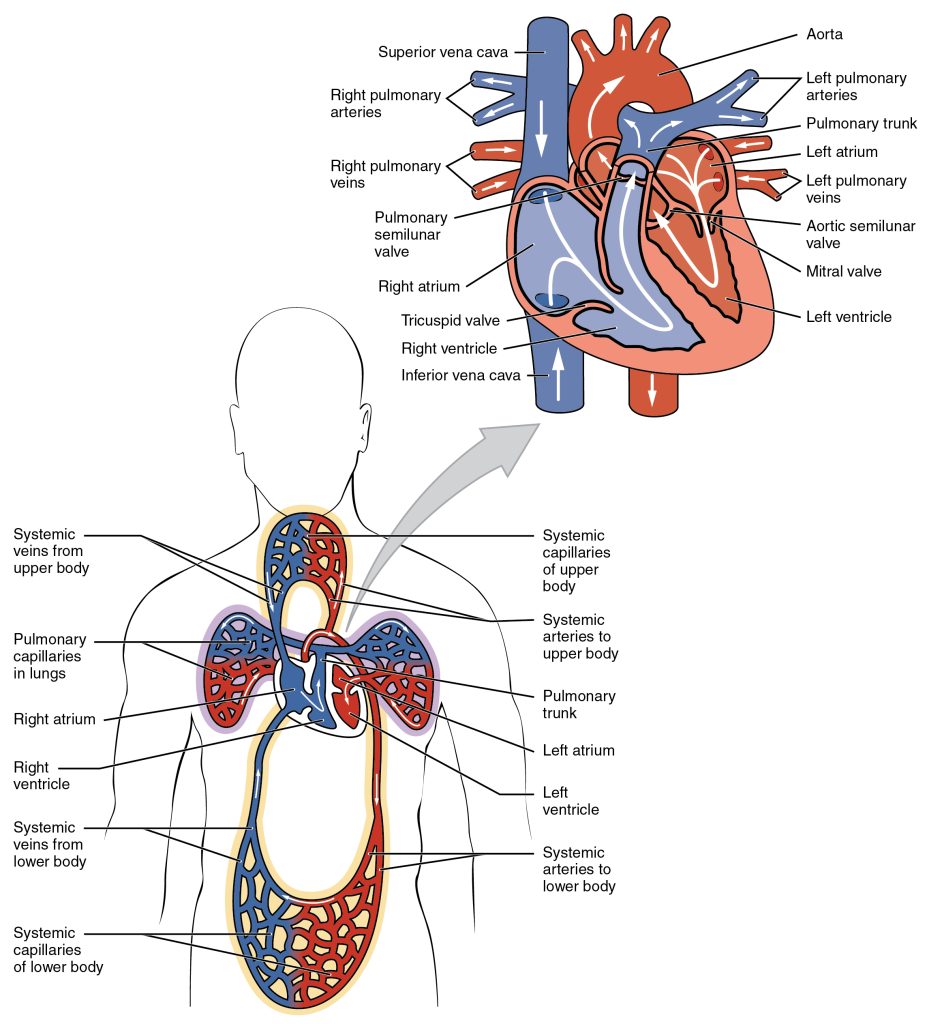

The heart consists of four chambers, including two atria and two ventricles. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation, and the left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs. The atria contract to push blood into the lower chambers, the right ventricle and the left ventricle. The right ventricle contracts to push blood into the lungs, and the left ventricle is the primary pump that propels blood to the rest of the body.

There are two distinct but linked circuits in the cardiovascular system called the pulmonary and systemic circuits. The pulmonary circuit transports blood to and from the lungs, where it picks up oxygen and delivers carbon dioxide for exhalation. The systemic circuit transports oxygenated blood to body tissues and returns deoxygenated blood and carbon dioxide to the heart to be sent back to the pulmonary circulation.[6] See Figure 8.2b[7] for an illustration of heart structures and blood flow through the heart and body. The blue areas indicate deoxygenated blood flow, and the red areas indicate oxygenated blood flow.

In order for oxygenated blood to move from the alveoli in the lungs to the various organs and tissues of the body, the heart must adequately pump blood through the systemic arteries. The amount of blood that the heart pumps in one minute is referred to as cardiac output. The passage of blood through arteries to an organ or tissue is referred to as perfusion. Several cardiac conditions can adversely affect cardiac output and perfusion in the body. There are several medications used to enhance cardiac output and maintain adequate perfusion to organs and tissues throughout the body.

Review common cardiac disorders and common cardiovascular system medications in the “Cardiovascular & Renal” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Review how to perform a cardiovascular assessment in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Hematological System

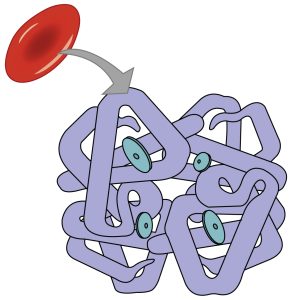

Although the bloodstream carries small amounts of dissolved oxygen, the majority of oxygen molecules are transported throughout the body by attaching to hemoglobin within red blood cells. Each hemoglobin protein is capable of carrying four oxygen molecules. When all four hemoglobin structures contain an oxygen molecule, it is referred to as “saturated.”[8] See Figure 8.2c[9] for an image of hemoglobin protein within a red blood cell with four sites for carrying oxygen molecules.

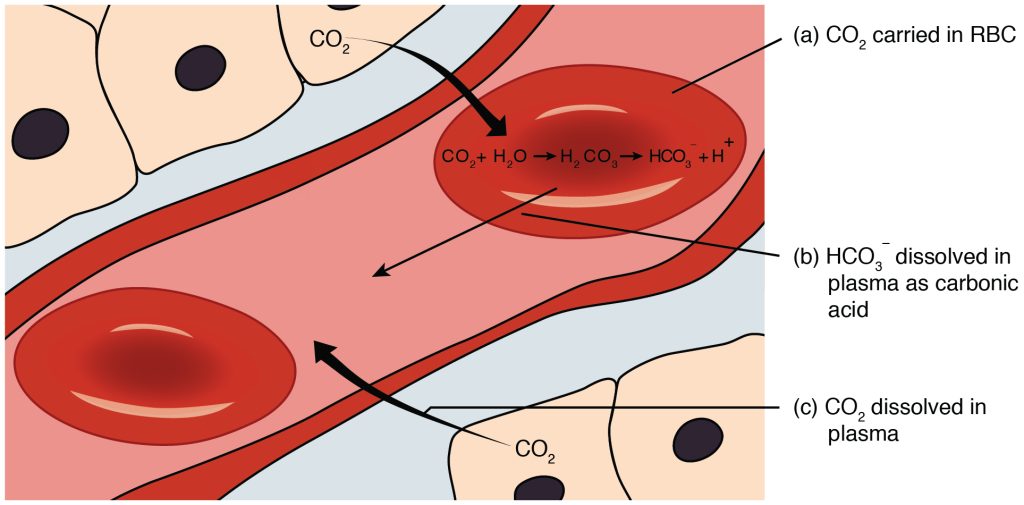

When oxygenated blood reaches tissues within the body, oxygen is released from the hemoglobin, and carbon dioxide is picked up and transported to the lungs for release on exhalation. Carbon dioxide is transported throughout the body by three major mechanisms: dissolved carbon dioxide, attachment to water as HCO3-, and attachment to the hemoglobin in red blood cells.[10] See Figure 8.2d[11] for an illustration of carbon dioxide transport.[12]

Measuring Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide, and Acid Base Levels

Because the majority of oxygen transported in the blood is attached to hemoglobin, a client’s oxygenation status is easily assessed using pulse oximetry, referred to as saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2). See Figure 8.3[13] for an image of a pulse oximeter. This reading refers to the amount of hemoglobin that is saturated. The target range of SpO2 for an adult is 94-98%.[14]

For clients with chronic oxygenation conditions such as COPD, the target range for SpO2 is often lower at 88% to 92%, although the acceptable SpO2 range should be specified by the provider. Although SpO2 is an efficient, noninvasive method for assessing a client’s oxygenation status, it is not always accurate, and data should be validated with other assessments. For example, if a client is severely anemic, the client has a decreased amount of hemoglobin in the blood available to carry the oxygen, which subsequently affects the SpO2 reading. Decreased perfusion of the extremities can also cause inaccurate SpO2 levels because less blood being delivered to the tissues can result in a false low SpO2. Similarly, cool extremities can also cause a false low reading. Additionally, other substances can attach to hemoglobin such as carbon monoxide, causing a falsely elevated SpO2.

A more specific and accurate measurement of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is obtained using an arterial blood gas (ABG). ABG results are often used for clients who have a deteriorating or unstable respiratory status requiring emergency treatment. An ABG is a specific type of blood sample drawn from an artery, typically the radial artery, by a respiratory therapist, physician, lab technician, or specially trained RN. ABG results indicate oxygen, carbon dioxide, pH, and bicarbonate levels in the arterial blood and are a more accurate measure of oxygenation status than SpO2[15]:

- PaO2: PaO2 is the partial pressure of oxygen dissolved in the arterial blood and is a measure of how well oxygen is able to move from the lungs into the bloodstream. The normal PaO2 level of a healthy adult is 80 to 100 mmHg. The PaO2 reading is more accurate than a SpO2 reading because it is not affected by hemoglobin levels.

- PaCO2: PaCO2 is the partial pressure of carbon dioxide dissolved in the arterial blood and measures how well carbon dioxide is able to move out of the body. It is typically used to determine if sufficient ventilation is occurring at the alveolar level. PaCO2 levels are affected by the rate and depth of ventilation. Decreased ventilation causes increased PaCO2 levels as gas exchange decreases and carbon dioxide is “retained.” The normal PaCO2 level of a healthy adult is 35-45 mmHg.

- pH level: Ph level is a measurement of acidity or alkalinity of the blood. The normal range of pH level for arterial blood is 7.35-7.45. A pH level below 7.35 is considered acidic, causing a condition called acidosis, and a pH level above 7.45 is considered alkaline, causing a condition known as alkalosis. Hydrogen ions are acids that affect the acidity of the blood and are regulated by respiratory rate and depth. Increased hydrogen ions cause increased acidity, and decreased hydrogen ions mean there is less acidity in the blood. Bicarbonate levels affect the alkalinity of the blood.

- HCO3: HCO3- is a measurement of bicarbonate levels in the blood. Bicarbonate is considered a buffer and is regulated by the kidneys. The kidneys retain HCO3- to make the blood more alkaline, and they excrete HCO3- to make the blood less alkaline. The normal range of HCO3- is 22-26.

- SaO2: SaO2 is the calculated arterial oxygen saturation level. SaO2 is similar to SpO2 in that it measures oxygen levels in the blood, but the SaO2 level is more accurate because it is not affected by poor perfusion, cool extremities, or carbon monoxide binding to hemoglobin. The normal SaO2 range for a healthy adult is 95-100%.

Read more information about ABG values and ABG interpretation in the “Acid-Base Balance” section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter.

Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia is defined as a reduced level of tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia has many causes, ranging from respiratory and cardiac conditions to anemia. Hypoxemia is a specific type of hypoxia that is defined as decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2) indicated in an arterial blood gas (ABG) result.

Early signs of hypoxia are related to the brain becoming starved of oxygen and include anxiety, confusion, and restlessness. As hypoxia worsens, the client’s level of consciousness and vital signs will worsen with an increased respiratory rate and heart rate and decreased pulse oximetry readings. Late signs of hypoxia include bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes called cyanosis. See Figure 8.4[16] for an image of cyanosis.

Hypercapnia, also referred to as hypercarbia, is an elevated level of carbon dioxide in the blood. This level is measured by the PaCO2 level in an ABG test and is indicated when the PaCO2 level is greater than 45. Hypercapnia is caused by hypoventilation or when the alveoli are ventilated but not perfused. In a state of hypercapnia, the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood causes the pH of the blood to decrease, leading to a state of respiratory acidosis. You can read more about respiratory acidosis in the “Acid-Base Balance” section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter.

It is important to note that some clients with hypercapnia may not initially exhibit changes in their vital signs. Instead, they may present with increased sedation or somnolence and decreased respiratory depth or rate. In these clients, SpO2 may be normal, but this should not provide false reassurance that their condition is stable. As hypercapnia worsens, the client will become increasingly unstable and may experience respiratory arrest.

Clients with hypercapnia have symptoms such as tachycardia, dyspnea, flushed skin, confusion, headaches, and dizziness. In cases of opioid or narcotic overdose, clients may have increased sedation with shallow respirations. If the hypercapnia develops gradually over time, symptoms may be mild or may not be present at all.[17]

Hypercapnia is managed by the health care team by addressing its underlying cause. A noninvasive positive pressure device such as a BiPAP may be used to help eliminate the excess carbon dioxide. If noninvasive devices are not sufficient, intubation with an endotracheal tube and mechanical ventilation may be required.[18]

Read more about BiPAP devices and intubation in the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Nurses must recognize early signs of respiratory distress and promptly report changes in client condition to prevent respiratory failure. See Table 8.2a for symptoms and signs of respiratory distress.[19]

Table 8.2a Symptoms and Signs of Respiratory Distress

| Signs and Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Shortness of breath (Dyspnea) | Dyspnea is a subjective feeling of not getting enough air. Depending on its severity, dyspnea can cause increased levels of anxiety. |

| Restlessness | An early sign of hypoxia resulting in increased movement and the inability to stay still. |

| Tachycardia | An elevated heart rate (above 100 beats per minute in adults) at rest can be an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachypnea | An increased respiration rate (above 20 breaths per minute in adults) at rest can be an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Oxygen saturation level (SpO2) | Oxygen saturation levels should be above 94% for adults who do not have an underlying respiratory condition. New SpO2 reading less than 92% may indicate hypoxia and require notification of the provider. SpO2 less than 88% may indicate severe hypoxia and require medical intervention.[20] |

| Use of accessory muscles | Use of neck or intercostal muscles when breathing is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Noisy breathing | Audible noises with breathing are an indication of respiratory conditions. Further assess lung sounds with a stethoscope for adventitious sounds such as wheezing, rales, or crackles. Secretions can plug the airway, thereby decreasing the amount of oxygen available for gas exchange in the lungs. |

| Flaring of nostrils | Nasal flaring is a sign of respiratory distress, especially in infants. |

| Skin color (Cyanosis) |

Bluish changes in skin color and mucus membranes is a late sign of hypoxia. |

| Position of client | Clients in respiratory distress often automatically sit up and lean over by resting arms on their legs, referred to as the tripod position. The tripod position enhances lung expansion. Conversely, clients who are hypoxic often feel worse dyspnea when lying flat in bed and avoid the supine position. |

| Ability of client to speak in full sentences | Clients in respiratory distress may be unable to speak in full sentences or may need to catch their breath between sentences. |

| New confusion or change in level of consciousness (LOC) | New confusion or changing level of consciousness can be an early sign of hypoxia resulting from lack of oxygen to the brain. |

Treating Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia and/or hypercapnia are medical emergencies and should be treated promptly by calling for assistance as indicated by agency policy.

Failure to initiate oxygen therapy when needed can result in serious harm or death of the client. Although oxygen is considered a medication that requires a prescription, oxygen therapy may be initiated without a physician’s order in emergency situations as part of the nurse’s response to the “ABCs,” a common abbreviation for airway, breathing, and circulation. Most agencies have a protocol in place that allows nurses to apply oxygen in emergency situations and obtain the necessary order at a later time.[21] Be aware of your specific agency policy.

In addition to administering oxygen therapy, there are several other interventions a nurse can implement to assist an hypoxic client. Additional interventions used to treat hypoxia in conjunction with oxygen therapy are outlined in Table 8.2b.

Table 8.2b Interventions to Manage Hypoxia

| Interventions | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Raise the head of the bed. | Raising the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position promotes effective chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, maximizes inhalation, and decreases the work of breathing. |

| Use tripod positioning. | Situate the client in a tripod position. Clients who are short of breath may gain relief by sitting upright and leaning over a bedside table while in bed, which is called a three-point or tripod position. The tripod position allows for increased lung expansion as gravity helps open the chest during inspiration. |

| Encourage enhanced breathing and coughing techniques. | Enhanced breathing and coughing include techniques such as pursed-lip breathing, coughing and deep breathing, huffing technique, and use of incentive spirometry and flutter valves. These techniques may assist clients to clear their airway, open alveoli to prevent atelectasis, and maintain good oxygen saturation levels. See the “Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques” section below for additional information regarding these techniques. |

| Manage oxygen therapy and equipment. | If the client is already on supplemental oxygen, ensure the equipment is turned on, set at the required flow rate, and is properly connected to an oxygen supply source. If a portable tank is being used, check the oxygen level in the tank. Ensure the connecting oxygen tubing is not kinked, which could obstruct the flow of oxygen. Feel for the flow of oxygen from the exit ports on the oxygen equipment and ensure the oxygen device is applied correctly on the client. In hospitals where medical air and oxygen are used, ensure the client is connected to the oxygen flow port.

Various types of oxygenation equipment are prescribed for clients requiring oxygen therapy. Oxygenation equipment is typically managed in collaboration with a respiratory therapist in hospital settings. Equipment includes devices such as nasal cannula, masks, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP), Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP), and mechanical ventilators. For more information, see the “Oxygenation Equipment” section of the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e. |

| Assess the need for respiratory medications. | Pharmacological management is essential for clients with respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, or severe allergic response. Bronchodilators effectively relax smooth muscles and open airways. Glucocorticoids relieve inflammation and also assist in opening air passages. Mucolytics decrease the thickness of pulmonary secretions so that they can be expectorated more easily. See the “Respiratory System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e for additional information on respiratory medications. |

| Provide suctioning, if needed. | Some clients may have a weakened cough that inhibits their ability to clear secretions from the mouth and throat. Clients with muscle disorders or those who have experienced a stroke (i.e., cerebral vascular accident) are at risk for aspiration, which could lead to pneumonia and hypoxia. Provide oral suction if the client is unable to clear secretions from the mouth and pharynx. See the “Tracheostomy Care and Suctioning” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e for additional details on suctioning. |

| Provide pain relief, if needed. | Provide adequate pain relief if the client is reporting pain. Pain increases anxiety and metabolic demands, which, in turn, increases the need for more oxygen supply. Pain medications such as morphine can also be used to decrease the work of breathing in clients experiencing air hunger, a severe form of dyspnea. |

| Consider side effects of pain medication. | A common side effect of pain medication is respiratory depression. For more information about managing respiratory depression, see the “Pain Management” section of the “Comfort” chapter. |

| Consider other devices to enhance clearance of secretions. | Chest physiotherapy and specialized devices assist with secretion clearance, such as handheld flutter valves or vests that inflate and vibrate the chest wall. These techniques are helpful to mobilize secretions and stimulate coughing to clear secretions out of the airway. Consult with a respiratory therapist as needed based on the client’s situation. |

| Plan frequent rest periods between activities. | Plan interventions for clients with dyspnea so they can rest frequently and decrease oxygen demand. |

| Consider other potential causes of dyspnea. | If a client’s level of dyspnea is worsening, assess for other underlying causes in addition to the primary diagnosis. For example, are there other respiratory, cardiovascular, or hematological conditions occurring? Start by reviewing the client’s most recent hemoglobin and hematocrit lab results, as well as any other diagnostic tests such as chest X-rays and ABG results. Completing a thorough assessment may reveal abnormalities in these systems to report to the health care provider. |

| Consider obstructive sleep apnea. | Clients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are often not previously diagnosed prior to hospitalization. OSA refers to cessation of breathing while sleeping and is caused by the partial or full collapse of the airway as muscles relax during sleep. This obstructs the airway and prevents air from moving in and out of the lungs during sleep. The nurse may notice the client snores, has pauses in breathing while snoring, has decreased oxygen saturation levels while sleeping, or awakens feeling not rested. These signs may indicate the client is unable to maintain an open airway while sleeping, resulting in periods of apnea and hypoxia. If these apneic periods are noticed but have not been previously documented, the nurse should report these findings to the health care provider for further testing and follow-up. A prescription for a CPAP or BiPAP device while sleeping may be needed to keep the airway open during sleep and to prevent adverse outcomes. |

| Monitor client’s anxiety. | Assess client’s anxiety. Anxiety often accompanies the feeling of dyspnea and can worsen dyspnea. Anxiety in clients with COPD is chronically undertreated. It is important for the nurse to address the feelings of anxiety in addition to the feelings of dyspnea. Anxiety can be relieved by teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques, encouraging relaxation techniques, or administering prescribed antianxiety medications like benzodiazepines. Read additional information about benzodiazepines in the “CNS Depressant” section of the “CNS System” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e. |

Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques

In addition to oxygen therapy and the interventions listed in Table 8.2b, there are several techniques a nurse can teach a client to use to enhance their breathing and coughing. These techniques include pursed-lip breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing and deep breathing, and the huffing technique. Additionally, vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy can be incorporated in collaboration with a respiratory therapist.

Pursed-lip Breathing

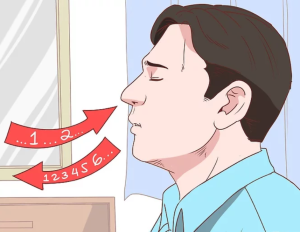

Pursed-lip breathing is a technique that decreases dyspnea by teaching people to control their oxygenation and ventilation. See Figure 8.5[22] for an illustration of pursed-lip breathing. The technique teaches a person to inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth at a slow, controlled flow. This type of exhalation gives the person a puckered or pursed-lip appearance. By prolonging the expiratory phase of respiration, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. This subsequently reduces air trapping that commonly occurs in conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Pursed-lip breathing relieves the feeling of shortness of breath, decreases the work of breathing, and improves gas exchange. People also regain a sense of control over their breathing while simultaneously increasing their relaxation.[23]

Incentive Spirometry

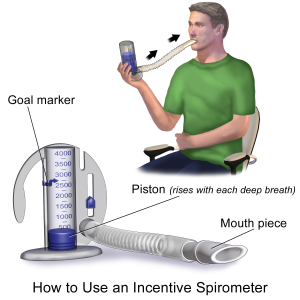

An incentive spirometer is a medical device commonly prescribed after surgery to expand the lungs to keep alveoli open, reduce the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and prevent pneumonia. See Figure 8.6[24] for an image of a client using an incentive spirometer. While sitting upright, if possible, the client should exhale fully, place the mouthpiece in their mouth and create a tight seal with their lips around it. They should breathe in slowly and as deeply as possible through the tubing with the goal of raising the piston to their prescribed level. The resistance indicator on the right side should be monitored to ensure they are not breathing in too quickly. The client should attempt to hold their breath for as long as possible (at least five seconds) and then exhale and rest for a few seconds. Coughing is expected due to alveoli stretching to open more fully. Encourage the client to expel any mucus produced and not swallow it. This technique should be repeated by the client ten times every hour while awake.[25] The nurse may delegate this intervention to unlicensed assistive personnel, but the frequency in which it is completed, and the volume achieved should be documented and monitored by the nurse.

Coughing and Deep Breathing

Coughing and deep breathing is a breathing technique similar to incentive spirometry but no device is required. The client is encouraged to take deep, slow breaths and then exhale slowly. After each set of breaths, the client should cough. This technique is repeated three to five times every hour. Similar to an incentive spirometer, the purpose of coughing and deep breathing is to keep the airways open and clear of mucus to prevent atelectasis and pneumonia.

Huffing Technique

The huffing technique is helpful to teach clients who have difficulty coughing. Teach the client to inhale with a medium-sized breath and then make a sound like “ha” to push the air out quickly with the mouth slightly open.

Vibratory PEP Therapy

Vibratory Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) Therapy uses handheld devices such as flutter valves or Acapella devices for clients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. These devices require a prescription and are used in collaboration with a respiratory therapist or advanced health care provider. To use vibratory PEP therapy, the client should sit up, take a deep breath, and blow into the device. A flutter valve within the device creates vibrations that help break up the mucus so the client can cough and spit it out. Additionally, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. See the supplementary video below regarding how to use the flutter valve device.

View this video on Using a Flutter Valve Device (Acapella).[26]

Media Attributions

- 2301_Major_Respiratory_Organs

- 2309_The_Respiratory_Zone

- 2003_Dual_System_of_Human_Circulation

- 2322_Fig_23.22-a

- 2325_Carbon_Dioxide_Transport

- OxyWatch_C20_Pulse_Oximeter

- pl

- Incentive_Spirometer

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2301 Major Respiratory Organs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-1-organs-and-structures-of-the-respiratory-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2309 The Respiratory Zone.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-1-organs-and-structures-of-the-respiratory-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Open RN Nursing Skills 2e by Chippewa Valley Technical College with CC BY 4.0 licensing. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Dual System of the Human Blood Circulation” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC By 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/19-1-heart-anatomy ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2322_Fig_23.33-a.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2325_Carbon_Dioxide_Transport.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “OxyWatch_C20_Pulse_Oximeter.png” by Thinkpaul is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Patel, Miao, Yetiskul, and Majmundar and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Castro and Keenaghan and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cynosis.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Patel, Miao, Yetiskul, and Majmundar and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Patel, Miao, Yetiskul, and Majmundar and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Yale Medicine. (2024). Pulse oximetry. https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/pulse-oximetry ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "v4-460px-Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease-Step-8.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Access for free at https://www.wikihow.com/Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Nguyen and Duong and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Incentive Spirometer.png” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2018, May 2). Incentive spirometer. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/4302-incentive-spirometer ↵

- NHS University Hospitals Plymouth Physiotherapy. (2015, May 12). Acapella [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/XOvonQVCE6Y ↵

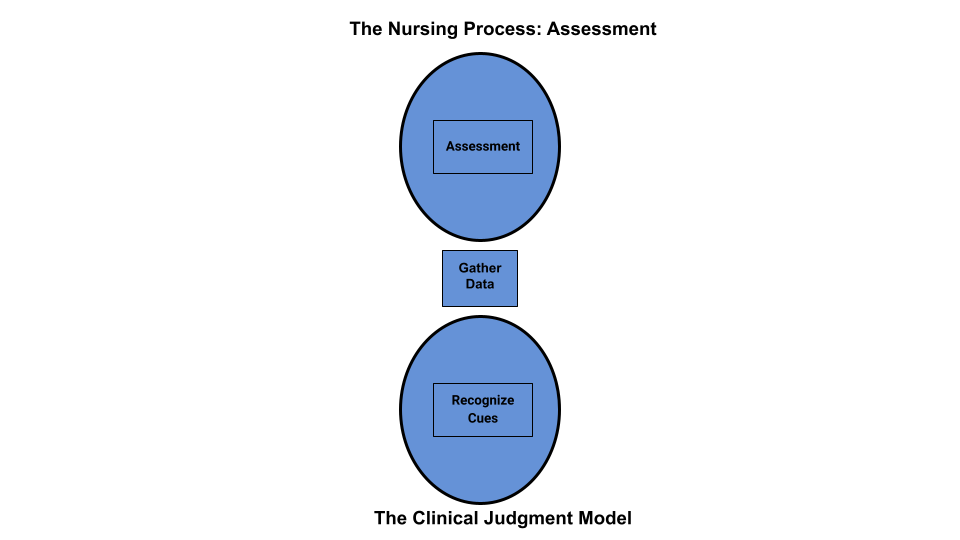

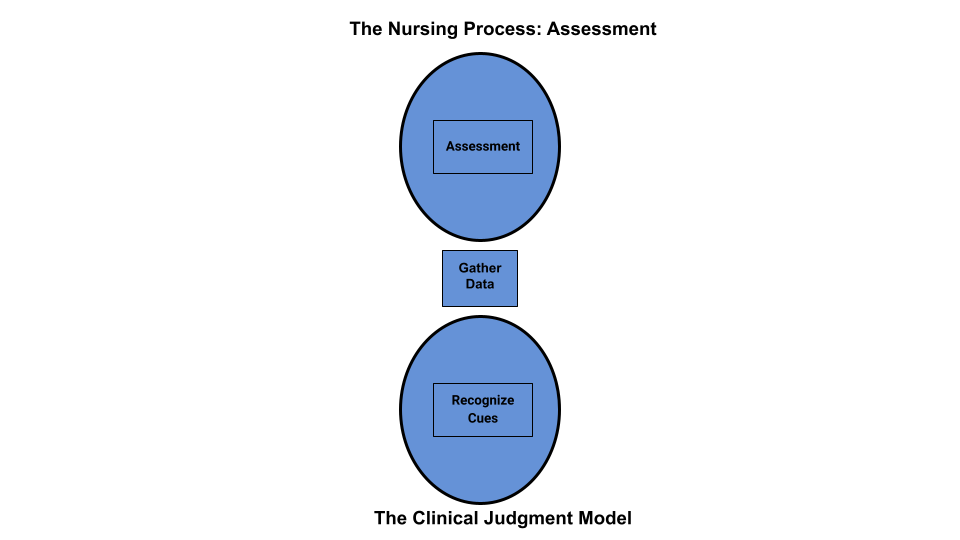

Assessment is the first step of the nursing process (and the first Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, "The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer's health or the situation." This includes collecting “pertinent data related to the health and quality of life in a systematic, ongoing manner, with compassion and respect for the wholeness, inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person, including, but not limited to, demographics, environmental and occupational exposures, social determinants of health, health disparities, physical, functional, psychosocial, emotional, cognitive, spiritual/transpersonal, sexual, sociocultural, age-related, environmental, and lifestyle/economic assessments.”[1] See Figure 4.5a for an illustration of how the Assessment phase of the nursing process corresponds to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM).[2]

Figure 4.5a Comparison of the Assessment Phase of the Nursing Process to the NCJMM

Nurses assess clients to gather information, then use critical thinking to analyze the data and recognized cues. Data is considered subjective or objective and can be collected from multiple sources.

Subjective Assessment Data

Subjective data is information obtained from the client and/or family members and offers important cues from their perspectives. When documenting subjective data stated by a client, it should be in quotation marks and start with verbiage such as, "The client reports..." It is vital for the nurse to establish rapport with a client to obtain accurate, valuable subjective data regarding the mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of their condition.

There are two types of subjective information, primary and secondary. Primary data is information provided directly by the client. Clients are the best source of information about their bodies and feelings, and the nurse who actively listens to a client will often learn valuable information while also promoting a sense of well-being. Information collected from a family member, chart, or other sources is known as secondary data. Family members can provide important information, especially for individuals with memory impairments, infants, children, or when clients are unable to speak for themselves.

See Figure 4.5b[3] for an illustration of a nurse obtaining subjective data and establishing rapport after obtaining permission from the client to sit on the bed.

Example of Subjective Data

An example of how to document subjective data obtained during a client assessment is, "The client reports, 'My pain is a level 2 on a 1-10 scale.'”

Objective Assessment Data

Objective data is anything that you can observe through your sense of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the client. Objective data is reproducible, meaning another person can easily obtain the same data. Examples of objective data are vital signs, physical examination findings, and laboratory results. See Figure 4.6[4] for an image of a nurse performing a physical examination.

Example of Objective Data

An example of documented objective data obtained during a client assessment is, "The client’s radial pulse is 58 and regular, and their skin feels warm and dry."

Sources of Assessment Data

There are three sources of assessment data: interview, physical examination, and review of laboratory or diagnostic test results.

Interviewing

Interviewing includes asking the client and their family members questions, listening, and observing verbal and nonverbal communication. Reviewing the chart prior to interviewing the client may eliminate redundancy in the interview process and allows the nurse to hone in on the most significant areas of concern or need for clarification. However, if information in the chart does not make sense or is incomplete, the nurse should use the interview process to verify data with the client.

After performing client identification, the best way to initiate a caring relationship is to introduce yourself to the client and explain your role. Share the purpose of your interview and the approximate time it will take. When beginning an interview, it may be helpful to start with questions related to the client’s medical diagnoses. Medical diagnoses are diseases, disorders, or injuries diagnosed by a physician or advanced health care provider, such as a nurse practitioner or physician's assistant. Reviewing the medical diagnoses allows the nurse to gather information about how they have affected the client's functioning, relationships, and lifestyle. Listen carefully and ask for clarification when something isn’t clear to you. Clients may not volunteer important information because they don’t realize it is important for their care. By using critical thinking and active listening, you may discover valuable cues that are important to provide safe, quality nursing care. Sometimes nursing students can feel uncomfortable having difficult conversations or asking personal questions due to generational or other cultural differences. Don’t shy away from asking about information that is important to know for safe client care. Most clients will be grateful that you cared enough to ask and listen.

Be alert and attentive to how the client answers questions, as well as when they do not answer a question. Nonverbal communication and body language can be cues to important information that requires further investigation. A keen sense of observation is important. To avoid making inappropriate inferences, the nurse should validate cues for accuracy. For example, a nurse may make an inference that a client appears depressed when the client avoids making eye contact during an interview. However, upon further questioning, the nurse may discover that the client’s cultural background believes direct eye contact to be disrespectful and this is why they are avoiding eye contact. To read more information about communicating with clients, review the “Communication” chapter of this book.

Physical Examination

A physical examination is a systematic data collection method of the body that uses the techniques of inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion. Inspection is the observation of a client’s anatomical structures. Auscultation is listening to sounds, such as heart, lung, and bowel sounds, created by organs using a stethoscope. Palpation is the use of touch to evaluate organs for size, location, or tenderness. Percussion is an advanced physical examination technique typically performed by providers where body parts are tapped with fingers to determine their size and if fluid or air are present. Detailed physical examination procedures of various body systems can be found in the Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e textbook with a head-to-toe checklist in Appendix C. Physical examination also includes the collection and analysis of vital signs.

Registered nurses (RNs) complete the initial physical examination and analyze the findings as part of the nursing process. Collection of follow-up physical examination data can be delegated to licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs), or measurements such as vital signs and weight may be delegated to trained unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) when appropriate to do so. However, the RN remains responsible for supervising these tasks, analyzing the findings, and ensuring they are documented.

A physical examination can be performed as a comprehensive head-to-toe assessment or as a focused assessment related to a particular condition or problem. Assessment data is documented in the client’s medical record, either in their electronic medical record (EMR) or their paper chart, depending upon agency policies and procedures.

Reviewing Laboratory and Diagnostic Test Results

Reviewing laboratory and diagnostic test results provides relevant and useful information related to the needs of the client. Understanding how normal and abnormal results affect client care is important when implementing the nursing care plan and administering provider prescriptions. If results cause concern, it is the nurse’s responsibility to notify the provider and verify the appropriateness of prescriptions based on the client’s current status before implementing them.

Types of Assessments

Several types of nursing assessment are used in clinical practice:

- Primary Survey: Used during every client encounter to briefly evaluate level of consciousness, airway, breathing, and circulation and implement emergency care if needed.

- Admission Assessment: A comprehensive assessment completed when a client is admitted to a facility that involves assessing a large amount of information using an organized approach.

- Ongoing Assessment: In acute care agencies such as hospitals, a head-to-toe assessment is completed and documented at least once every shift. Any changes in client condition are reported to the health care provider.

- Focused Assessment: Focused assessments are used to reevaluate the status of a previously diagnosed problem.

- Time-lapsed Reassessment: Time-lapsed reassessments are used in long-term care facilities when three or more months have elapsed since the previous assessment to evaluate progress on previously identified outcomes.[5]

Putting It Together

Review Scenario C in the following box to apply concepts of assessment to a client scenario.

Scenario C[6]

Ms. J. is a 74-year-old woman who is admitted directly to the medical unit after visiting her physician because of shortness of breath, increased swelling in her ankles and calves, and fatigue. Her medical history includes hypertension (30 years), coronary artery disease (18 years), heart failure (2 years), and type 2 diabetes (14 years). She takes 81 mg of aspirin every day, metoprolol 50 mg twice a day, furosemide 40 mg every day, and metformin 2,000 mg every day.

Ms. J.’s vital sign values on admission were as follows:

- Blood Pressure: 162/96 mm Hg

- Heart Rate: 88 beats/min

- Oxygen Saturation: 91% on room air

- Respiratory Rate: 28 breaths/minute

- Temperature: 97.8 degrees F orally

Her weight is up 10 pounds since the last office visit three weeks prior. The client states, “I am so short of breath” and “My ankles are so swollen I have to wear my house slippers.” Ms. J. also shares, “I am so tired and weak that I can’t get out of the house to shop for groceries,” and “Sometimes I’m afraid to get out of bed because I get so dizzy.” She confides, “I would like to learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.”

The physical assessment findings of Ms. J. are bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs and bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet. Laboratory results indicate a decreased serum potassium level of 3.4 mEq/L.

As the nurse completes the physical assessment, the client’s daughter enters the room. She confides, “We are so worried about mom living at home by herself when she is so tired all the time!”

Critical Thinking Questions

- Identify relevant subjective data.

- Identify relevant objective data.

- Provide an example of secondary data.

Answers are located in the Answer Key at the end of the book.

Assessment is the first step of the nursing process (and the first Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, "The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer's health or the situation." This includes collecting “pertinent data related to the health and quality of life in a systematic, ongoing manner, with compassion and respect for the wholeness, inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person, including, but not limited to, demographics, environmental and occupational exposures, social determinants of health, health disparities, physical, functional, psychosocial, emotional, cognitive, spiritual/transpersonal, sexual, sociocultural, age-related, environmental, and lifestyle/economic assessments.”[7] See Figure 4.5a for an illustration of how the Assessment phase of the nursing process corresponds to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM).[8]

Figure 4.5a Comparison of the Assessment Phase of the Nursing Process to the NCJMM

Nurses assess clients to gather information, then use critical thinking to analyze the data and recognized cues. Data is considered subjective or objective and can be collected from multiple sources.

Subjective Assessment Data

Subjective data is information obtained from the client and/or family members and offers important cues from their perspectives. When documenting subjective data stated by a client, it should be in quotation marks and start with verbiage such as, "The client reports..." It is vital for the nurse to establish rapport with a client to obtain accurate, valuable subjective data regarding the mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of their condition.

There are two types of subjective information, primary and secondary. Primary data is information provided directly by the client. Clients are the best source of information about their bodies and feelings, and the nurse who actively listens to a client will often learn valuable information while also promoting a sense of well-being. Information collected from a family member, chart, or other sources is known as secondary data. Family members can provide important information, especially for individuals with memory impairments, infants, children, or when clients are unable to speak for themselves.

See Figure 4.5b[9] for an illustration of a nurse obtaining subjective data and establishing rapport after obtaining permission from the client to sit on the bed.

Example of Subjective Data

An example of how to document subjective data obtained during a client assessment is, "The client reports, 'My pain is a level 2 on a 1-10 scale.'”

Objective Assessment Data

Objective data is anything that you can observe through your sense of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the client. Objective data is reproducible, meaning another person can easily obtain the same data. Examples of objective data are vital signs, physical examination findings, and laboratory results. See Figure 4.6[10] for an image of a nurse performing a physical examination.

Example of Objective Data

An example of documented objective data obtained during a client assessment is, "The client’s radial pulse is 58 and regular, and their skin feels warm and dry."

Sources of Assessment Data

There are three sources of assessment data: interview, physical examination, and review of laboratory or diagnostic test results.

Interviewing

Interviewing includes asking the client and their family members questions, listening, and observing verbal and nonverbal communication. Reviewing the chart prior to interviewing the client may eliminate redundancy in the interview process and allows the nurse to hone in on the most significant areas of concern or need for clarification. However, if information in the chart does not make sense or is incomplete, the nurse should use the interview process to verify data with the client.

After performing client identification, the best way to initiate a caring relationship is to introduce yourself to the client and explain your role. Share the purpose of your interview and the approximate time it will take. When beginning an interview, it may be helpful to start with questions related to the client’s medical diagnoses. Medical diagnoses are diseases, disorders, or injuries diagnosed by a physician or advanced health care provider, such as a nurse practitioner or physician's assistant. Reviewing the medical diagnoses allows the nurse to gather information about how they have affected the client's functioning, relationships, and lifestyle. Listen carefully and ask for clarification when something isn’t clear to you. Clients may not volunteer important information because they don’t realize it is important for their care. By using critical thinking and active listening, you may discover valuable cues that are important to provide safe, quality nursing care. Sometimes nursing students can feel uncomfortable having difficult conversations or asking personal questions due to generational or other cultural differences. Don’t shy away from asking about information that is important to know for safe client care. Most clients will be grateful that you cared enough to ask and listen.

Be alert and attentive to how the client answers questions, as well as when they do not answer a question. Nonverbal communication and body language can be cues to important information that requires further investigation. A keen sense of observation is important. To avoid making inappropriate inferences, the nurse should validate cues for accuracy. For example, a nurse may make an inference that a client appears depressed when the client avoids making eye contact during an interview. However, upon further questioning, the nurse may discover that the client’s cultural background believes direct eye contact to be disrespectful and this is why they are avoiding eye contact. To read more information about communicating with clients, review the “Communication” chapter of this book.

Physical Examination

A physical examination is a systematic data collection method of the body that uses the techniques of inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion. Inspection is the observation of a client’s anatomical structures. Auscultation is listening to sounds, such as heart, lung, and bowel sounds, created by organs using a stethoscope. Palpation is the use of touch to evaluate organs for size, location, or tenderness. Percussion is an advanced physical examination technique typically performed by providers where body parts are tapped with fingers to determine their size and if fluid or air are present. Detailed physical examination procedures of various body systems can be found in the Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e textbook with a head-to-toe checklist in Appendix C. Physical examination also includes the collection and analysis of vital signs.

Registered nurses (RNs) complete the initial physical examination and analyze the findings as part of the nursing process. Collection of follow-up physical examination data can be delegated to licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs), or measurements such as vital signs and weight may be delegated to trained unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) when appropriate to do so. However, the RN remains responsible for supervising these tasks, analyzing the findings, and ensuring they are documented.

A physical examination can be performed as a comprehensive head-to-toe assessment or as a focused assessment related to a particular condition or problem. Assessment data is documented in the client’s medical record, either in their electronic medical record (EMR) or their paper chart, depending upon agency policies and procedures.

Reviewing Laboratory and Diagnostic Test Results

Reviewing laboratory and diagnostic test results provides relevant and useful information related to the needs of the client. Understanding how normal and abnormal results affect client care is important when implementing the nursing care plan and administering provider prescriptions. If results cause concern, it is the nurse’s responsibility to notify the provider and verify the appropriateness of prescriptions based on the client’s current status before implementing them.

Types of Assessments

Several types of nursing assessment are used in clinical practice:

- Primary Survey: Used during every client encounter to briefly evaluate level of consciousness, airway, breathing, and circulation and implement emergency care if needed.

- Admission Assessment: A comprehensive assessment completed when a client is admitted to a facility that involves assessing a large amount of information using an organized approach.

- Ongoing Assessment: In acute care agencies such as hospitals, a head-to-toe assessment is completed and documented at least once every shift. Any changes in client condition are reported to the health care provider.

- Focused Assessment: Focused assessments are used to reevaluate the status of a previously diagnosed problem.

- Time-lapsed Reassessment: Time-lapsed reassessments are used in long-term care facilities when three or more months have elapsed since the previous assessment to evaluate progress on previously identified outcomes.[11]

Putting It Together

Review Scenario C in the following box to apply concepts of assessment to a client scenario.

Scenario C[12]

Ms. J. is a 74-year-old woman who is admitted directly to the medical unit after visiting her physician because of shortness of breath, increased swelling in her ankles and calves, and fatigue. Her medical history includes hypertension (30 years), coronary artery disease (18 years), heart failure (2 years), and type 2 diabetes (14 years). She takes 81 mg of aspirin every day, metoprolol 50 mg twice a day, furosemide 40 mg every day, and metformin 2,000 mg every day.

Ms. J.’s vital sign values on admission were as follows:

- Blood Pressure: 162/96 mm Hg

- Heart Rate: 88 beats/min

- Oxygen Saturation: 91% on room air

- Respiratory Rate: 28 breaths/minute

- Temperature: 97.8 degrees F orally

Her weight is up 10 pounds since the last office visit three weeks prior. The client states, “I am so short of breath” and “My ankles are so swollen I have to wear my house slippers.” Ms. J. also shares, “I am so tired and weak that I can’t get out of the house to shop for groceries,” and “Sometimes I’m afraid to get out of bed because I get so dizzy.” She confides, “I would like to learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.”

The physical assessment findings of Ms. J. are bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs and bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet. Laboratory results indicate a decreased serum potassium level of 3.4 mEq/L.

As the nurse completes the physical assessment, the client’s daughter enters the room. She confides, “We are so worried about mom living at home by herself when she is so tired all the time!”

Critical Thinking Questions

- Identify relevant subjective data.

- Identify relevant objective data.

- Provide an example of secondary data.

Answers are located in the Answer Key at the end of the book.

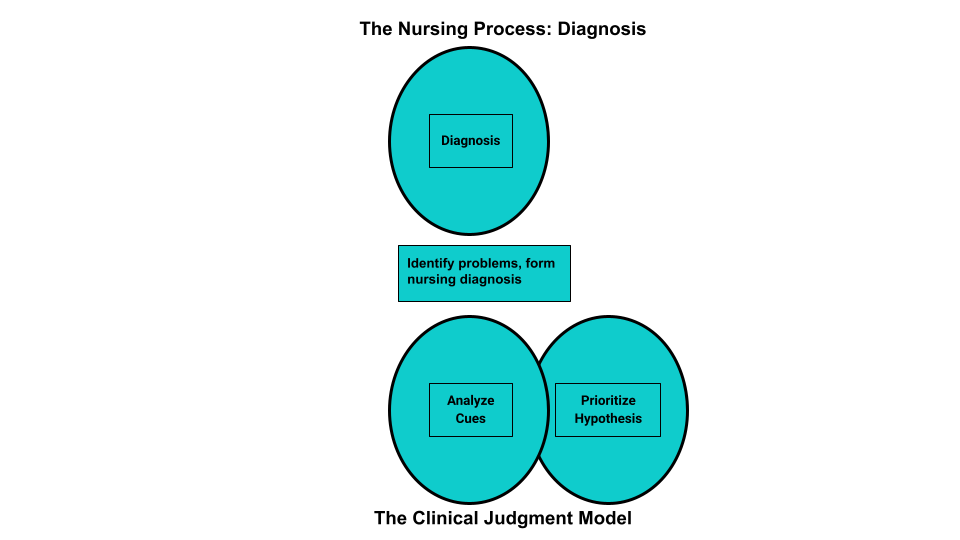

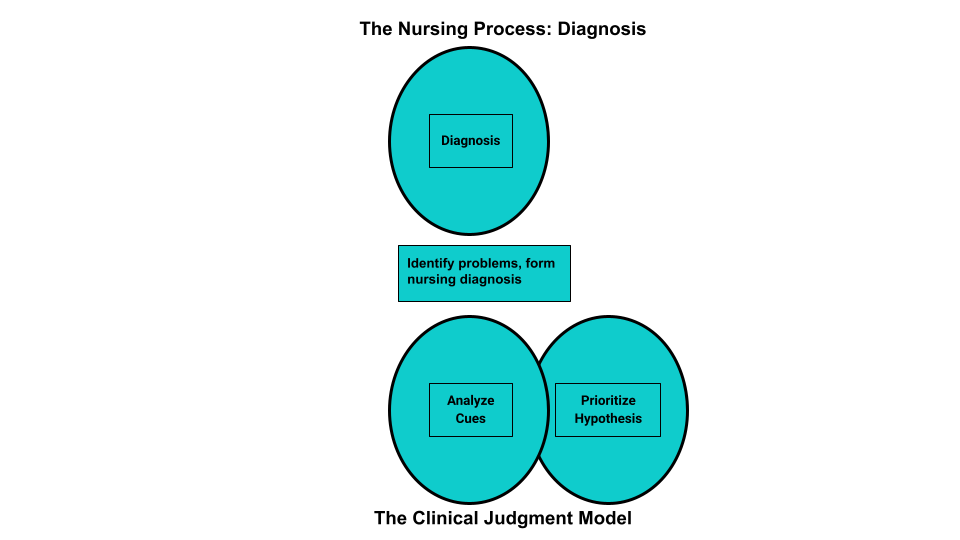

Diagnosis is the second step of the nursing process (and the second Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, "The registered nurse analyzes assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues." The RN “prioritizes diagnoses, problems, and issues based on mutually established goals to meet the needs of the health care consumer across the health–illness continuum and the care continuum.” Diagnoses, problems, strengths, and issues are documented in a manner that facilitates the development of expected outcomes and a collaborative plan.[13] See Figure 4.7a for an illustration of how the Diagnosis phase of the nursing process corresponds to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM).[14]

Analyzing Assessment Data

After collection of assessment data, the RN analyzes the data to form generalizations and create and prioritize hypotheses for nursing diagnoses. Steps for analyzing assessment data include performing data analysis, clustering information, identifying hypotheses for potential nursing diagnosis, performing additional in-depth assessment as needed, and establishing nursing diagnosis statements. The nursing diagnoses are then prioritized and the nursing care plan is developed based on them.[15] Analyzing assessment data is completed by an RN and falls outside of the scope of practice of the LPN/VN. However, LPN/VNs must understand data analysis so that new, concerning data is promptly reported to the RN for follow-up.

Performing Data Analysis

After nurses collect assessment data from a client, they use their nursing knowledge to analyze that data to determine if it is “expected” or “unexpected” or “normal” or “abnormal” for that client according to their age, development, and baseline status. From there, nurses determine what data is “clinically relevant” as they prioritize their nursing care.[16]

Example of Analyzing Cues

In Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter, the nurse analyzes the vital signs data and determines the blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate are elevated, and the oxygen saturation is decreased for this client. These findings are considered “relevant cues" because they are abnormal compared to this client's baseline and may indicate a new health problem or complication is occurring.

Clustering Information/Seeing Patterns/Making Hypotheses

After analyzing the data and determining relevant cues, the nurse begins clustering data into similar domains or patterns. Evidence-based assessment frameworks, such as Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns, assist nurses in clustering data based on patterns of human responses. See the box below for an outline of Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns.[17] Concepts related to many of these patterns will be discussed in chapters later in this book.

Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns[18]

Health Perception-Health Management: A client’s perception of their health and well-being and how it is managed

Nutritional-Metabolic: Food and fluid consumption relative to metabolic need

Elimination: Excretory function, including bowel, bladder, and skin

Activity-Exercise: Exercise and daily activities

Sleep-Rest: Sleep, rest, and daily activities

Cognitive-Perceptual: Perception and cognition

Self-perception and Self-concept: Self-concept and perception of self-worth, self-competency, body image, and mood state

Role-Relationship: Role engagements and relationships

Sexuality-Reproductive: Reproduction and satisfaction or dissatisfaction with sexuality

Coping-Stress Tolerance: Coping and effectiveness in terms of stress tolerance

Value-Belief: Values, beliefs (including spiritual beliefs), and goals that guide choices and decisions

Example of Using Gordon's Health Patterns to Cluster Data

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. The nurse clusters the following relevant cues: elevated blood pressure, elevated respiratory rate, crackles in the lungs, weight gain, worsening edema, shortness of breath, medical history of heart failure, and currently prescribed a diuretic medication into a pattern of fluid balance, which can be classified under Gordon’s Nutritional-Metabolic Functional Health Pattern. Based on the related data in this cluster, the nurse makes a hypothesis that the client has excess fluid volume present.

Identifying Nursing Diagnoses

After the nurse has analyzed and clustered the data from the client assessment, the next step is to begin to answer the question, “What are my client’s human responses to their health condition(s) (i.e., their nursing diagnoses)?” A nursing diagnosis is defined as, "A clinical judgment concerning a human response to health conditions/life processes, or a vulnerability for that response, by an individual, family, group, or community."[19] Nursing diagnoses are customized to each client and drive the development of the nursing care plan. The nurse should refer to a care planning resource and review the definitions and defining characteristics of the hypothesized nursing diagnoses to determine if additional in-depth assessment is needed before selecting the most accurate nursing diagnosis. Formulation of nursing diagnoses is completed by an RN and is outside the scope of practice of LPN/VNs.

Nursing diagnoses are developed by nurses, for use by nurses. For example, NANDA International (NANDA-I) is a global professional nursing organization that develops nursing terminology that names actual or potential human responses to health problems and life processes based on research findings.[20] Currently, there are over 220 NANDA-I nursing diagnoses developed by nurses around the world. This list is continuously updated, with new nursing diagnoses added and old nursing diagnoses retired that no longer have supporting evidence. A list of commonly used NANDA-I diagnoses is listed in Appendix A. For a full list of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, refer to a current nursing care plan reference.

NANDA-I nursing diagnoses are grouped into 13 domains that assist the nurse in selecting diagnoses based on the patterns of clustered data. These domains are similar to Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns and include health promotion, nutrition, elimination and exchange, activity/rest, perception/cognition, self-perception, role relationship, sexuality, coping/stress tolerance, life principles, safety/protection, comfort, and growth/development.

NANDA Diagnoses and the NCLEX

Knowledge regarding specific NANDA-I nursing diagnoses is not assessed on the NCLEX. However, analyzing cues, clustering data, forming appropriate hypotheses, and prioritizing hypotheses are components of clinical judgment assessed on the NCLEX and used in nursing practice. Read more about the Next Generation NCLEX in the "Scope of Practice" chapter.

Nursing Diagnoses vs. Medical Diagnoses

You may be asking yourself, “How are nursing diagnoses different from medical diagnoses?” Medical diagnoses focus on diseases or other medical problems that have been identified by the physician, physician’s assistant, or advanced nurse practitioner. Nursing diagnoses focus on the human response to health conditions and life processes and are made independently by RNs. Clients with the same medical diagnosis will often respond differently to that diagnosis and thus have different nursing diagnoses. For example, two clients have the same medical diagnosis of heart failure. However, one client may be interested in learning more information about the condition and the medications used to treat it, whereas another client may be experiencing anxiety when thinking about the effects this medical diagnosis will have on their family. The nurse must consider these different responses when creating the nursing care plan. Nursing diagnoses consider the client’s and family’s needs, attitudes, strengths, challenges, and resources as a customized nursing care plan is created to provide holistic and individualized care for each client.

Example of a Medical Diagnosis

A medical diagnosis identified for Ms. J. in Scenario C in the "Assessment" section is heart failure. This cannot be used as a nursing diagnosis because it is outside the nurse's scope of practice to make a medical diagnosis, but it is considered as an “associated condition” when creating hypotheses for nursing diagnoses. Associated conditions are medical diagnoses, injuries, procedures, medical devices, or pharmacological agents that are not independently modifiable by the nurse, but support accuracy in nursing diagnosis. The nursing diagnosis in Scenario C will relate to the client’s responses to her medical diagnosis of heart failure, such as "Excess Fluid Volume."

Additional Definitions Used in NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses

The following definitions are used in association with NANDA-I nursing diagnoses.

Patient

The NANDA-I definition of a “patient” includes the following:

- Individual: a single human being distinct from others (i.e., a person).

- Caregiver: a family member or helper who regularly looks after a child or a sick, elderly, or disabled person.

- Family: two or more people having continuous or sustained relationships, perceiving reciprocal obligations, sensing common meaning, and sharing certain obligations toward others; related by blood and/or choice.

- Group: a number of people with shared characteristics, such as an ethnic group.

- Community: a group of people living in the same locale under the same governance. Examples include neighborhoods and cities.[21]

Age

The age of the person who is the subject of the diagnosis is defined by the following terms[22]:

- Fetus: an unborn human more than eight weeks after conception, until birth.

- Neonate: a person less than 28 days of age.

- Infant: a person greater than 28 days and less than 1 year of age.

- Child: a person aged 1 to 9 years.

- Adolescent: a person aged 10 to 19 years.

- Adult: a person older than 19 years of age unless national law defines a person as being an adult at an earlier age.

- Older adult: a person greater than 65 years of age.

Time

The duration of the diagnosis is defined by the following terms[23]:

- Acute: lasting less than three months.

- Chronic: lasting greater than three months.

- Intermittent: stopping or starting again at intervals.

- Continuous: uninterrupted, going on without stop.

Two terms used to assist in creating nursing diagnoses are at-risk populations and associated conditions[24]:

- At-risk populations are groups of people who share a characteristic that causes each member to be susceptible to a particular human response, such as demographics, health/family history, stages of growth/development, or exposure to certain events/experiences.

- Associated conditions are medical diagnoses, injuries, procedures, medical devices, or pharmacological agents. These conditions are not independently modifiable by the nurse, but support accuracy in nursing diagnosis.[25]

Types of Nursing Diagnoses

There are four types of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses:[26]

- Problem-Focused

- Health Promotion - Wellness

- Risk

- Syndrome

A problem-focused nursing diagnosis is a “clinical judgment concerning an undesirable human response to health condition/life processes that exist in an individual, family, group, or community.”[27] To make an accurate problem-focused diagnosis, related factors and defining characteristics must be present. Related factors (also called etiology) are causes that contribute to the diagnosis. Defining characteristics are cues, signs, and symptoms that cluster into patterns.[28] Defining characteristics are the signs and symptoms that a nurse can observe, hear, feel, or smell and cluster into patterns underlying nursing diagnoses.

A health promotion-wellness nursing diagnosis is “a clinical judgment concerning motivation and desire to increase well-being and to actualize human health potential.” These responses are expressed by the client’s readiness to enhance specific health behaviors.[29] A health promotion-wellness diagnosis is used when the client is willing to improve a lack of knowledge, coping, or other identified need.

A risk nursing diagnosis is “a clinical judgment concerning the vulnerability of an individual, family, group, or community for developing an undesirable human response to health conditions/life processes.”[30] A risk nursing diagnosis must be supported by risk factors that contribute to the increased vulnerability. A risk nursing diagnosis is different from the problem-focused diagnosis in that the problem has not yet actually occurred. Problem diagnoses should not be automatically viewed as more important than risk diagnoses because sometimes a risk diagnosis can have the highest priority for a client.[31]

A syndrome nursing diagnosis is a “clinical judgment concerning a specific cluster of nursing diagnoses that occur together and are best addressed together and through similar interventions.”[32]

Establishing Nursing Diagnosis Statements

NANDA-I recommends creating statements for nursing diagnosis that include the nursing diagnosis and related factors as exhibited by defining characteristics. The accuracy of the nursing diagnosis is validated when a nurse is able to clearly link the defining characteristics, related factors, and/or risk factors found during the client’s assessment.[33]

To create a nursing diagnosis statement, the RN analyzes the client’s subjective and objective data and clusters the data into patterns. Based on these patterns, the RN generates hypotheses for nursing diagnoses based on how the patterns meet defining characteristics of a nursing diagnosis. Recall that "defining characteristics" are the signs and symptoms related to a nursing diagnosis.[34] Defining characteristics are included in care planning resources for each nursing diagnosis, along with a definition of that diagnosis, so the nurse can select the most accurate diagnosis.

Example

An RN clusters objective and subjective data such as weight, height, and dietary intake as a pattern related to nutritional status and then compares these signs and symptoms to the defining characteristics for the NANDA nursing diagnosis, "Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirement."

When creating a nursing diagnosis statement, the nurse also identifies the cause, or etiology, of the problem for that specific client. Recall that the term "related factors" refers to the underlying causes (etiology) of a client’s problem or situation. Related factors should not refer to medical diagnoses, but instead should be causes that the nurse can treat. When possible, the nursing interventions planned for nursing diagnoses should attempt to modify or remove these underlying causes of the nursing diagnosis.[35]

Creating nursing diagnosis statements is also called “using PES format.” The PES mnemonic no longer applies to the current terminology used by NANDA-I, but the components of a nursing diagnosis statement remain the same. A nursing diagnosis statement should contain the problem, related factors, and defining characteristics. These terms fit under the former PES format in this manner:

Problem (P): The problem (i.e., the nursing diagnosis)

Etiology (E): The related factors (i.e., the etiology/cause) of the nursing diagnosis; phrased as “related to” or “R/T”

Signs and Symptoms (S): The defining characteristics manifested by the client (i.e., the signs and symptoms/subjective and objective data/clinical cues) that led to the identification of that nursing diagnosis/hypothesis for the client; phrased with “as manifested by" (AMB) or "as evidenced by" (AEB).

Examples of different types of nursing diagnoses are further explained in the following sections.

Problem-Focused Nursing Diagnosis

A problem-focused nursing diagnosis contains all three components of the PES format:

Problem (P): Client problem (nursing diagnosis)

Etiology (E): Related factors causing the nursing diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms (S): Defining characteristics/cues manifested by that client (i.e., the signs and symptoms demonstrating there is a problem)

Example of a Problem-Focused Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C of the "Assessment" section of this chapter. The cluster of data for Ms. J. (elevated blood pressure, elevated respiratory rate, crackles in the lungs, weight gain, worsening edema, and shortness of breath) are defining characteristics for the NANDA-I Nursing Diagnosis Excess Fluid Volume. The NANDA-I definition of Excess Fluid Volume is “surplus intake and/or retention of fluid.” The related factor (etiology) of the problem is that the client has excessive fluid intake.[36]

The components of a problem-focused nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Excess Fluid Volume

Etiology (E): Related to excessive fluid intake

Signs and Symptoms (S): As manifested by bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet, increased weight of 1ten pounds, and the client reports, “My ankles are so swollen.”

A correctly written problem-focused nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Excess Fluid Volume related to excessive fluid intake as manifested by bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet, an increase weight of 1ten pounds, and the client reports, “My ankles are so swollen.”

Health-Promotion Nursing Diagnosis

A health-promotion nursing diagnosis statement contains the problem (P) and the defining characteristics (S). The defining characteristics component of a health-promotion nursing diagnosis statement should begin with the phrase “expresses desire to enhance,” followed by what the client states in relation to improving their health status:[37]

A health-promotion diagnosis statement consists of the following:

Problem (P): Client problem (nursing diagnosis)

Signs and Symptoms (S): The client’s expressed desire to enhance

Example of a Health-Promotion Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. Ms. J. demonstrates a readiness to improve her health status when she told the nurse that she would like to “learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.” This statement is a defining characteristic of the NANDA-I nursing diagnosis Readiness for Enhanced Health Management, which is defined as “a pattern of regulating and integrating into daily living a therapeutic regimen for the treatment of illness and its sequelae, which can be strengthened.”[38]

The components of a health-promotion nursing diagnosis for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Readiness for Enhanced Health Management

Symptoms (S): Expressed desire to “learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.”

A correctly written health-promotion nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Enhanced Readiness for Health Promotion as manifested by expressed desire to “learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.”

Risk Nursing Diagnosis

A risk nursing diagnosis should be supported by evidence of the client’s risk factors for developing that problem. Different experts recommend different phrasing. NANDA-I 2018-2020 recommends using the phrase “as evidenced by” to refer to the risk factors for developing that problem.[39]

A risk diagnosis consists of the following:

Problem (P): Client problem (nursing diagnosis)

As Evidenced By: Risk factors for developing the problem

Example of a Risk Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. Ms. J. has an increased risk of falling due to vulnerability from the dizziness and weakness she is experiencing. The NANDA-I definition of Risk for Falls is “increased susceptibility to falling, which may cause physical harm and compromise health.”[40]

The components of a risk nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Risk for Falls

As Evidenced By: Dizziness and decreased lower extremity strength

A correctly written risk nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Risk for Falls as evidenced by dizziness and decreased lower extremity strength.

Syndrome Nursing Diagnosis

A syndrome nursing diagnosis statement is a cluster of nursing diagnoses that occur together and are best addressed together and through similar interventions. To create a syndrome diagnosis, two or more nursing diagnoses must be used as defining characteristics (S) that create a syndrome. Related factors may be used if they add clarity to the definition but are not required.[41]

A syndrome statement consists of these items:

Problem (P): The syndrome

Signs and Symptoms (S): The defining characteristics are two or more similar nursing diagnoses

Example of a Syndrome Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. Clustering the data for Ms. J. identifies several similar NANDA-I nursing diagnoses that can be categorized as a syndrome. For example, Activity Intolerance is defined as “insufficient physiological or psychological energy to endure or complete required or desired daily activities.” Social Isolation is defined as “aloneness experienced by the individual and perceived as imposed by others and as a negative or threatening state.” These diagnoses can be included under the NANDA-I syndrome named Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome. This syndrome is defined as a “dynamic state of unstable equilibrium that affects the older individual experiencing deterioration in one or more domains of health (physical, functional, psychological, or social) and leads to increased susceptibility to adverse health effects, in particular disability.”[42]

Example

The components of a syndrome nursing diagnosis for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome

Signs and Symptoms (S): The nursing diagnoses of Activity Intolerance and Social Isolation

Additional related factor: Fear of falling

A correctly written syndrome diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome related to activity intolerance, social isolation, and fear of falling

See Table 4.4a for a summary of the types of nursing diagnoses.

Table 4.4a. Types of Nursing Diagnoses

| Diagnosis | What Is It? | Example of Nursing Diagnosis Statement |

| Problem-Focused (Actual) | Problem is present at the time of assessment | (PES) Fluid Volume Excess R/T excessive fluid intake AEB bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema in the ankles and feet, an increased weight of 10 pounds over 1 week, and the client reports, "My ankles feel swollen." |

| Health-Promotion | A motivation/desire to increase well-being or a client's strength | Enhanced Readiness for Health Promotion AEB expressed desire to "learn more about health so I can take better care of myself." |

| Risk | Problem is likely to develop | Risk for Falls AEB dizziness and decreased lower extremity strength |

| Syndrome | Cluster of nursing diagnoses that occur together and are best addressed together | Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome R/T activity intolerance, social isolation, and fear of falling |

Clinical Tip: It can feel overwhelming for nursing students to determine which nursing diagnoses to use for their clients due to the complexity of nursing diagnoses. Rest assured, use of nursing diagnoses becomes easier with practice and exposure to client care plans. Refer to trustworthy sources, such as a nursing diagnosis handbook or reputable care-planning resources to become aware of current NANDA-I nursing diagnoses.

Nursing diagnoses can be viewed to establish familiarity with them on the nandadiagnoses.com website, but but be aware this is not an official NANDA nursing diagnosis site. Evidence-based care planning resources should be used when planning clientcare.

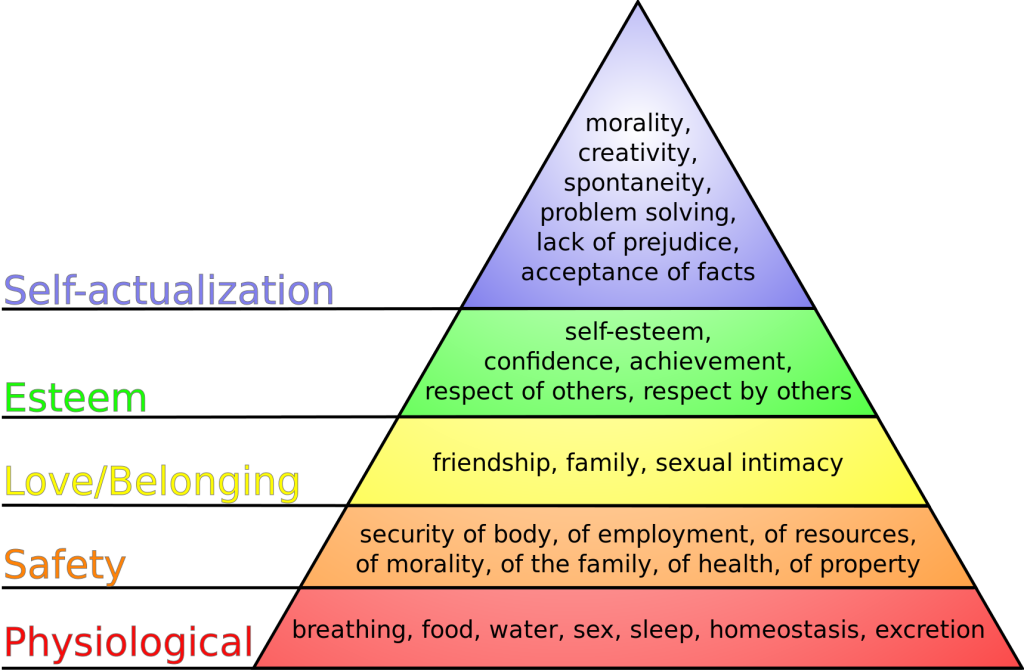

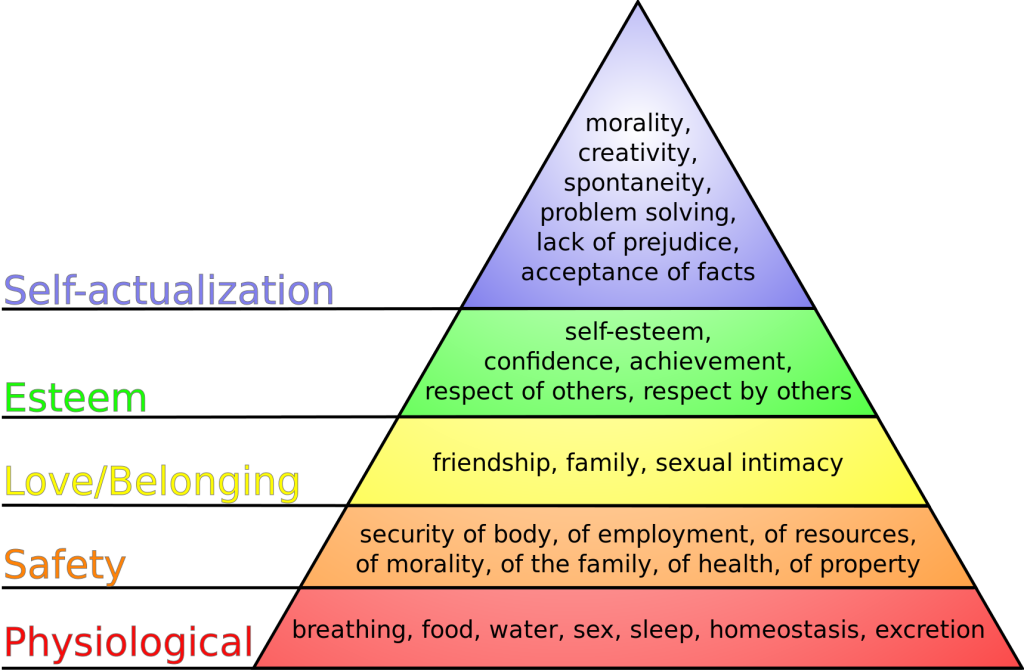

Prioritization