Therapeutic Levels

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Now that the concepts of dose-response, onset, peak, and duration have been discussed, it is important to understand the therapeutic window and therapeutic index.

Therapeutic Window

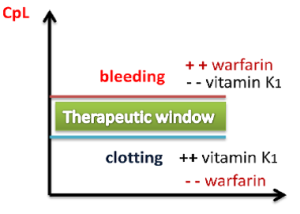

For every drug, there exists a dose that is minimally effective (the Effective Concentration) and another dose that is toxic (the Toxic Concentration). Between these doses is the therapeutic window, where the safest and most effective treatment will occur. For example, see Figure 1.9[1] for an illustration of the therapeutic window for warfarin, a medication used to prevent blood clotting. Too much warfarin administered causes bleeding and vitamin K is required as an antidote. Conversely, not enough warfarin administered for a client’s condition can cause clotting. Think of the therapeutic window (the green area on the graph) as the “perfect dose,” where clotting is prevented and yet bleeding does not occur.

The effect of warfarin is monitored using a blood test called international normalized ration (INR). For clients receiving warfarin, nurses vigilantly monitor their INR levels to ensure the dosage appropriately reaches their therapeutic window and does not place them at risk for bleeding or clotting.

Peak and Trough Levels

Now let’s apply the idea of therapeutic window to the administration of medications requiring the monitoring of peak and trough levels, which is commonly required in the administration of specific IV antibiotics. The dosage of these medications is titrated, meaning adjusted for safety, to achieve a desired therapeutic effect for the client. Titration is accomplished by closely monitoring the peak and trough levels of the medication. A drug is said to be within the “therapeutic window” when the serum blood levels of an active drug remain consistently above the level of effective concentration (so that the medication is achieving its desired therapeutic effect) and consistently below the toxic level (so that no toxic effects are occurring).

A peak drug level is drawn after the medication is administered and is known to be at the highest level in the bloodstream. A trough level is drawn when the drug is at its lowest in the bloodstream, right before the next scheduled dose is given. Medications have a predicted reference range of normal values for peak and trough levels. These numbers assist the pharmacist and provider in gauging how the body is metabolizing, protein-binding, and excreting the drug and are used to adjust the prescribed dose to keep the medication within the therapeutic window. When administering IV medications that require peak or trough levels, it is vital for the nurse to plan the administration of the medication according to the timing of these blood draws.[2]

Therapeutic Index

The therapeutic index is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug. It is a comparison of the amount of drug that produces a therapeutic effect versus the amount of drug that produces a toxic effect.

- A large (or high) therapeutic index number means there is a wide therapeutic window between the effective concentration and the toxic concentration of a medication, so the drug is relatively safe.

- A small (or low) therapeutic index number means there is a narrow therapeutic window between the effective concentration and the toxic concentration. A drug with a narrow therapeutic range (i.e., having little difference between toxic and therapeutic doses) often has the dosage titrated according to measurements of the actual blood levels achieved in the person taking it.

For example, phenytoin has a narrow therapeutic index between the effective and toxic concentrations. Clients who start taking phenytoin to control seizures have frequent peak and trough drug levels to ensure they achieve steady state with a therapeutic dose to prevent seizures without reaching toxic levels.

Critical Thinking Activity 1.10

Mr. Parker has been receiving gentamicin 80 mg IV three times daily to treat his infective endocarditis. He has his gentamicin level checked one hour after the end of his previous gentamicin infusion was completed. The result is 30 mcg/mL. Access the information below to determine the nurse’s course of action.

View information on therapeutic drug levels.

(After accessing the information, be sure to select “click to keep reading” in order to view drugs that are commonly checked, their target levels, and what abnormal results mean.)

Based on the results in the above client scenario, what action will the nurse take based on the result of the gentamicin level of 30 mcg/mL?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Media Attributions

- Therapeutic Window © Shefaa Alasfoor is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- ORN-Icons_internet-copy_internet-copy-300×300-1

- “Therapeutic Window” by Shefaa Alasfoor is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Principles of Pharmacology by LibreTexts and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

“Prevent residents from falling” is one of the National Patient Safety Goals for nursing care centers. Client falls, whether in the nursing care center, home, or hospital, are very common and can cause serious injury and death. Older adults have the highest risk of falling. Each year, 3 million older people are treated in emergency departments for fall injuries, and over 800,000 clients a year are hospitalized because of a head injury or hip fracture resulting from a fall. Many older adults who fall, even if they’re not injured, become afraid of falling. This fear may cause them to limit their everyday activities. However, when a person is less active, they become weaker, which further increases their chances of falling.[1]

Many conditions contribute to client falls, including the following:[2]

- Lower body weakness

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Difficulties with walking and balance

- Medications, such as tranquilizers, sedatives, antihypertensives, or antidepressants

- Vision problems

- Foot pain or poor footwear

- Environmental hazards, such as throw rugs or clutter that can cause tripping

Most falls are caused by a combination of risk factors. The more risk factors a person has, the greater their chances of falling. Many risk factors can be changed or modified to help prevent falls.

The Centers for Disease Control has developed a program called “STEADI - Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries” to help reduce the risk of older adults from falling at home. Three screening questions to determine risk for falls are as follows:

- Do you feel unsteady when standing or walking?

- Do you have worries about falling?

- Have you fallen in the past year? If yes, how many times? Were you injured?

If the individual answers “Yes” to any of these questions, further assessment of risk factors is performed.[3]

Read more information about preventing falls in older adults at CDC's Older Adult Fall Prevention.

Fall Assessment Tools

By virtue of being ill, all hospitalized clients are at risk for falls, but some clients are at higher risk than others. Assessment is an ongoing process with the goal of identifying a client’s specific risk factors and implementing interventions in their care plan to decrease their risk of falling. Commonly used fall assessment tools used to identify clients at high risk for falls are the Morse Fall Scale, the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model, and the Hester Davis Scale for fall risk assessment. Read more about these fall risk assessment tools using the hyperlinks provided below. Key risk factors for falls in hospitalized clients are as follows:[4]

- History of falls: All clients with a recent history of falls, such as a fall in the past three months, should be considered at higher risk for future falls.

- Mobility problems and use of assistive devices: Clients who have problems with their gait or require an assistive device (such as a cane or a walker) for mobility are more likely to fall.

- Medications: Clients taking several prescription medications or those taking medications that could cause sedation, confusion, impaired balance, or orthostatic blood pressure changes are at higher risk for falls.

- Mental status: Clients with delirium, dementia, or psychosis may be agitated and confused, putting them at risk for falls.

- Incontinence: Clients who have urinary frequency or who have frequent toileting needs are at higher fall risk.

- Equipment: Clients who are tethered to equipment such as an IV pole or a Foley catheter are at higher risk of tripping.

- Impaired vision: Clients with impaired vision or those who require glasses but who are not wearing them are at a higher fall risk because of their decreased recognition of an environmental hazard.

- Orthostatic hypotension: Clients whose blood pressure drops upon standing often experience light-headedness or dizziness that can cause falls.[5]

View these common fall risk assessment tools:

Interventions to Prevent Falls

Universal fall precautions are established for all clients to reduce their risk for falling. In addition to universal fall precautions, a care plan is created based on the client's fall risk assessment findings to address their specific risks and needs.

Universal Fall Precautions

Falls are the most commonly reported client safety incidents in the acute care setting. Hospitals pose an inherent fall risk due to the unfamiliarity of the environment and various hazards in the hospital room that pose a risk. During inpatient care, nurses assess their clients’ risk for falling during every shift and implement interventions to reduce the risk of falling. Universal fall precautions have been developed that apply to all clients all the time. Universal fall precautions are called "universal" because they apply to all clients, regardless of fall risk, and revolve around keeping the client's environment safe and comfortable.[8]

Universal fall precautions include the following:

- Familiarize the client with the environment.

- Have the client demonstrate call light use.

- Maintain the call light within reach. See Figure 5.5[9] for an image of a call light.

- Keep the client's personal possessions within safe reach.

- Have sturdy handrails in client bathrooms, rooms, and hallways.

- Place the hospital bed in the low position when a client is resting. Raise the bed to a comfortable height when the client is transferring out of bed.

- Keep the hospital bed brakes locked.

- Keep wheelchair wheels in a "locked" position when stationary.

- Keep no-slip, comfortable, and well-fitting footwear on the client.

- Use night lights or supplemental lighting.

- Keep floor surfaces clean and dry. Clean up all spills promptly.

- Keep client care areas uncluttered.

- Follow safe client handling practices.[10]

Interventions Based on Risk Factors

Clients at elevated risk for falling require multiple, individualized interventions, in addition to universal fall precautions. There are many interventions available to prevent falls and fall-related injuries based on the client's specific risk factors. See Table 5.6a for interventions categorized by risk factor.[11]

Table 5.6a Interventions Based on Fall Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | Interventions |

|---|---|

| Altered Mental Status | Clients with new altered mental status should be assessed for delirium and treated by a trained nurse or physician. See a tool for assessing delirium below. For cognitively impaired clients who are agitated or trying to wander, more intense supervision (e.g., sitter or checks every 15 minutes) may be needed. Some hospitals implement designated safety zones that include low beds, mats for each side of the bed, nightlight, gait belt, and a "STOP" sign to remind clients not to get up. |

| Impaired Gait or Mobility | Clients with impaired gait or mobility will need assistance with mobility during their hospital stay. All clients should have any needed assistive devices, such as canes or walkers, in good repair at the bedside and within safe reach. If clients bring their assistive devices from home, staff should make sure these devices are safe for use in the hospital environment. Even with assistive devices, clients often need staff assistance when transferring out of bed or walking. Use a gait belt when assisting clients to transfer or ambulate per agency policy. |

| Frequent Toileting Needs | Clients with frequent toileting needs should be taken to the toilet on a regular basis via a scheduled rounding protocol. Read more about scheduled rounding in the following subsection. |

| Visual Impairment | Clients with visual impairment should have clean corrective lenses easily within reach and applied when walking. |

| High-Risk Medications (medicines that could cause sedation, confusion, impaired balance, orthostatic blood pressure changes, or cause frequent urination) | Clients on high-risk medications should have their medications reviewed by a pharmacist with fall risk in mind and recommendations made to the prescribing provider for discontinuation, substitution, or dose adjustment when possible. If a pharmacist is not immediately available, the prescribing provider should carry out a medication review. See Table 5.6b for a tool to review medications for fall risk. Clients on medications that cause orthostatic hypotension should have their orthostatic blood pressure routinely checked and reported. The client and their caregivers should be educated about fall risk and steps to prevent falls when the client is taking these medications. |

| Frequent Falls | Clients with a history of frequent falls should have their risk for injury assessed, including checking for a history of osteoporosis and use of aspirin and anticoagulants. |

Scheduled Hourly Rounding

Scheduled hourly rounds are scheduled hourly visits to each client’s room to integrate fall prevention activities with client care. Scheduled hourly rounds have been found to greatly decrease the incidence of falls because the client's needs are proactively met, reducing the motivation for the client to get out of bed unassisted. See the box below for a list of activities to complete during hourly rounds. These activities can be completed by unlicensed assistive personnel, nurses, or nurse managers.[12]

Hourly Rounding Protocol[13]

- Assess client pain levels using a pain-assessment scale. (If staff other than a nurse is doing the rounding and the client is in pain, contact the nurse immediately so the client does not have to use the call light for pain medication.)

- Put pain medication that is ordered “as needed” on an RN’s task list and offer the dose when it is due.

- Offer toileting assistance.

- Ensure the client is using correct footwear (e.g., specific shoes/slippers, no-skid socks).

- Check that the bed is in the locked position.

- Place the hospital bed in a low position when the client is resting; ask if the client needs to be repositioned and is comfortable.

- Make sure the call light/call bell button is within the client’s reach and the client can demonstrate accurate use.

- Put the telephone within the client’s reach.

- Put the TV remote control and bed light switch within the client’s reach.

- Put the bedside table next to the bed or across the bed.

- Put the tissue box and water within the client’s reach.

- Put the garbage can next to the bed.

- Prior to leaving the room, ask, “Is there anything I can do for you before I leave?"

- Tell the client that a member of the nursing staff (use names on whiteboard) will be back in the room in an hour to round again.

Medications Causing Elevated Risk for Falls

Evaluate medication-related fall risk for clients on admission and at regular intervals thereafter. Add up the point value (risk level) in Table 5.6b for every medication the client is taking. If the client is taking more than one medication in a particular risk category, the score should be calculated by (risk level score) x (number of medications in that risk level category). For a client at risk, a pharmacist should review the client’s list of medications and determine if medications may be tapered, discontinued, or changed to a safer alternative.[14]

Table 5.6b Medications Causing High Risk for Falls[15]

| Point Value (Risk Level) | Medication Class | Fall Risks |

|---|---|---|

| 3 (High) | Antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines | Sedation, dizziness, postural disturbances, altered gait and balance, and impaired cognition |

| 2 (Medium) | Antihypertensives, cardiac drugs, antiarrhythmics, and antidepressants | Induced orthostasis, impaired cerebral perfusion, and poor health status |

| 1 (Low) | Diuretics | Increased ambulation and induced orthostasis |

| Score ≥ 6 | Elevated risk for falls; ask pharmacist or prescribing provider to evaluate medications for possible modification to reduce risk |

View tools used to assess delirium and confusion in the Delirium Evaluation Bundle shared by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Answer Key to Chapter 11 Learning Activities

-

Priority Actions First Assess pulse oximetry Second Assess lung sounds Third Apply oxygen as ordered Four Reassess pulse oximetry Fifth Institute actions to improve oxygenation Sixth Teach oxygen safety (Rationale: Priority of actions includes the gathering of assessment information to reflect the patient’s respiratory condition. Once you have collected information, intervention can be initiated with application of oxygen if needed and subsequent reassessment of the pulse oximetry reading. Additional actions to improve patient oxygenation and lung capacity can then be implemented with coughing, deep breathing, and use of incentive spirometry. Finally, once the patient experiences improvement in oxygenation and breathing status, reinforcement of oxygen education and safety measures would be appropriate.)

Answers to interactive elements are given within the interactive element.

In addition to implementing safety strategies to improve safe client care, leaders of a health care agency must also establish a culture of safety. A culture of safety reflects the behaviors, beliefs, and values within and across all levels of an organization as they relate to safety and clinical excellence, with a focus on people. In 2021 The Joint Commission released a sentinel event regarding the essential role of leadership in establishing a culture of safety. According to The Joint Commission, leadership has an obligation to be accountable for protecting the safety of all health care consumers, including clients, employees, and visitors. Without adequate leadership and an effective culture of safety, there is higher risk for adverse events. Inadequate leadership can contribute to adverse effects in a variety of ways, including, but not limited to, the following[16]:

- Insufficient support of client safety event reporting

- Lack of feedback or response to staff and others who report safety vulnerabilities

- Allowing intimidation of staff who report events

- Refusing to consistently prioritize and implement safety recommendations

- Not addressing staff burnout

Three components of a culture of safety are the following[17]:

- Just Culture: People are encouraged, even rewarded, for providing essential safety-related information, but clear lines are drawn between human error and at-risk or reckless behaviors.

- Reporting Culture: People report errors and near-misses.

- Learning Culture: The willingness and the competence to draw the right conclusions from safety information systems, and the will to implement major reforms when their need is indicated.

The American Nurses Association further describes a culture of safety as one that includes openness and mutual respect when discussing safety concerns and solutions without shifting to individual blame, a learning environment with transparency and accountability, and reliable teams. In contrast, complexity, lack of clear measures, hierarchical authority, the “blame game,” and lack of leadership are examples of barriers that do not promote a culture of safety. If staff fear reprisal for mistakes and errors, they will be less likely to report errors, processes will not be improved, and client safety will continue to be impaired. See the following box for an example of safety themes established during a health care institution’s implementation of a culture of safety.

Safety Themes in a Culture of Safety[18]

Kaiser Permantente implemented a culture of safety in 2001 that focused on instituting the following six strategic themes:

- Safe culture: Creating and maintaining a strong safety culture, with client safety and error reduction embraced as shared organizational values.

- Safe care: Ensuring that the actual and potential hazards associated with high-risk procedures, processes, and client care populations are identified, assessed, and managed in a way that demonstrates continuous improvement and ultimately ensures that clients are free from accidental injury or illness.

- Safe staff: Ensuring that staff possess the knowledge and competence to perform required duties safely and contribute to improving system safety performance.

- Safe support systems: Identifying, implementing, and maintaining support systems—including knowledge-sharing networks and systems for responsible reporting—that provide the right information to the right people at the right time.

- Safe place: Designing, constructing, operating, and maintaining the environment of health care to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness.

- Safe clients: Engaging clients and their families in reducing medical errors, improving overall system safety performance, and maintaining trust and respect.

A strong safety culture encourages all members of the health care team to identify and reduce risks to client safety by reporting errors and near misses so that root cause analysis can be performed and identified risks are removed from the system. However, in a poorly defined and implemented culture of safety, staff often conceal errors due to fear or shame. Nurses have been traditionally trained to believe that clinical perfection is attainable, and that “good” nurses do not make errors. Errors are perceived as being caused by carelessness, inattention, indifference, or uninformed decisions. Although expecting high standards of performance is appropriate and desirable, it can become counterproductive if it creates an expectation of perfection that impacts the reporting of errors and near misses. If employees feel shame when they make an error, they may feel pressure to hide or cover up errors. Evidence indicates that approximately three of every four errors are detected by those committing them, as opposed to being detected by an environmental cue or another person. Therefore, employees need to be able to trust that they can fully report errors without fear of being wrongfully blamed. This provides the agency with the opportunity to learn how to further improve processes and prevent future errors from occurring. For many organizations, the largest barrier in establishing a culture of safety is the establishment of trust. A model called “Just Culture” has successfully been implemented in many agencies to decrease the “blame game,” promote trust, and improve the reporting of errors.

Just Culture

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture, stating, “Traditionally, healthcare’s culture has held individuals accountable for all errors or mishaps that befall clients under their care. By contrast, a Just Culture recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. A Just Culture also recognizes many individual or ‘active’ errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, in contrast to a culture that touts ‘no blame’ as its governing principle, a Just Culture does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to clients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).”

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three causes of errors. Consequences of errors are based on whether the error is a simple human error or caused by at-risk or reckless behavior.

- Simple human error: A simple human error occurs when an individual inadvertently does something other than what should have been done. Most medical errors are the result of human error due to poor processes, programs, education, environmental issues, or situations. These errors are managed by correcting the cause, looking at the process, and fixing the deviation. For example, a nurse appropriately checks the rights of medication administration three times, but due to the similar appearance and names of two different medications stored next to each other in the medication dispensing system, administers the incorrect medication to a client. In this example, a root cause analysis reveals a system issue that must be modified to prevent future errors (e.g., change the labelling and storage of look alike-sound alike medication).

- At-risk behavior: An error due to at-risk behavior occurs when a behavioral choice is made that increases risk where the risk is not recognized or is mistakenly believed to be justified. For example, a nurse scans a client’s medication with a barcode scanner prior to administration, but an error message appears on the scanner. The nurse mistakenly interprets the error to be a technology problem and proceeds to administer the medication instead of stopping the process and further investigating the error message, resulting in the wrong dosage of a medication being administered to the client. In this case, ignoring the error message on the scanner can be considered “at-risk behavior” because the behavioral choice was considered justified by the nurse at the time.

- Reckless behavior: Reckless behavior is an error that occurs when an action is taken with conscious disregard for a substantial and unjustifiable risk.[19] For example, a nurse arrives at work intoxicated and administers the wrong medication to the wrong client. This error is considered due to reckless behavior because the decision to arrive intoxicated was made with conscious disregard for substantial risk.

These examples show three different causes of medication errors that would result in different consequences to the employee based on the Just Culture model. Under the Just Culture model, after root cause analysis is completed, system-wide changes are made to decrease factors that contributed to the error. Managers appropriately hold individuals accountable for errors if they were due to simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behaviors.

If an individual commits a simple human error, managers console the individual and consider changes in training, procedures, and processes. In the “simple human error” above, system-wide changes would be made to change the label and location of the medication to prevent future errors from occurring with the same medication.

Individuals committing at-risk behavior are held accountable for their behavioral choice and often require coaching with incentives for less risky behaviors and situational awareness. In the “at-risk behavior” example above where the nurse ignored an error message on the barcode scanner, mandatory training on using a barcode scanner and responding to errors would be implemented, and the manager would track the employee’s correct usage of the barcode scanner for several months following training.

If an individual demonstrates reckless behavior, remedial action and/or punitive action is taken.[20] In the “reckless behavior” example above, the manager would report the nurse’s behavior to the state's Board of Nursing with mandatory substance abuse counseling to maintain their nursing license. Employment may be terminated with consideration of patterns of behavior.

A Just Culture in which employees aren't afraid to report errors is a highly successful way to enhance client safety, increase staff and client satisfaction, and improve outcomes. Success is achieved through good communication, effective management of resources, and an openness to changing processes to ensure the safety of clients and employees. The infographic in Figure 5.4[21] illustrates the components of a culture of safety and Just Culture.

The principles of culture of safety, including Just Culture, Reporting Culture, and Learning Culture are also being adopted in nursing education. It’s understood that mistakes are part of learning and that a shared accountability model promotes individual- and system-level learning for improved client safety. Under a shared accountability model, students are responsible for the following[22]:

- Being fully prepared for clinical experiences, including laboratory and simulation assignments

- Being rested and mentally ready for a challenging learning environment

- Accepting accountability for their part in contributing to a safe learning environment

- Behaving professionally

- Reporting their own errors and near mistakes

- Keeping up-to-date with current evidence-based practice

- Adhering to ethical and legal standards

Students know they will be held accountable for their actions, but will not be blamed for system faults that lie beyond their control. They can trust that a fair process will be used to determine what went wrong if a client care error or near miss occurs. Student errors and near misses are addressed based on an investigation determining if it was simple human error, an at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. For example, a simple human error by a student can be addressed with coaching and additional learning opportunities to remedy the knowledge deficit. However, if a student acts with recklessness (for example, repeatedly arrives to clinical unprepared despite previous faculty feedback or falsely documents an assessment or procedure), they are appropriately and fairly disciplined, which may include dismissal from the program.[23]

Answer Key to Chapter 11 Learning Activities

-

Priority Actions First Assess pulse oximetry Second Assess lung sounds Third Apply oxygen as ordered Four Reassess pulse oximetry Fifth Institute actions to improve oxygenation Sixth Teach oxygen safety (Rationale: Priority of actions includes the gathering of assessment information to reflect the patient’s respiratory condition. Once you have collected information, intervention can be initiated with application of oxygen if needed and subsequent reassessment of the pulse oximetry reading. Additional actions to improve patient oxygenation and lung capacity can then be implemented with coughing, deep breathing, and use of incentive spirometry. Finally, once the patient experiences improvement in oxygenation and breathing status, reinforcement of oxygen education and safety measures would be appropriate.)

Answers to interactive elements are given within the interactive element.

Definition of Restraints

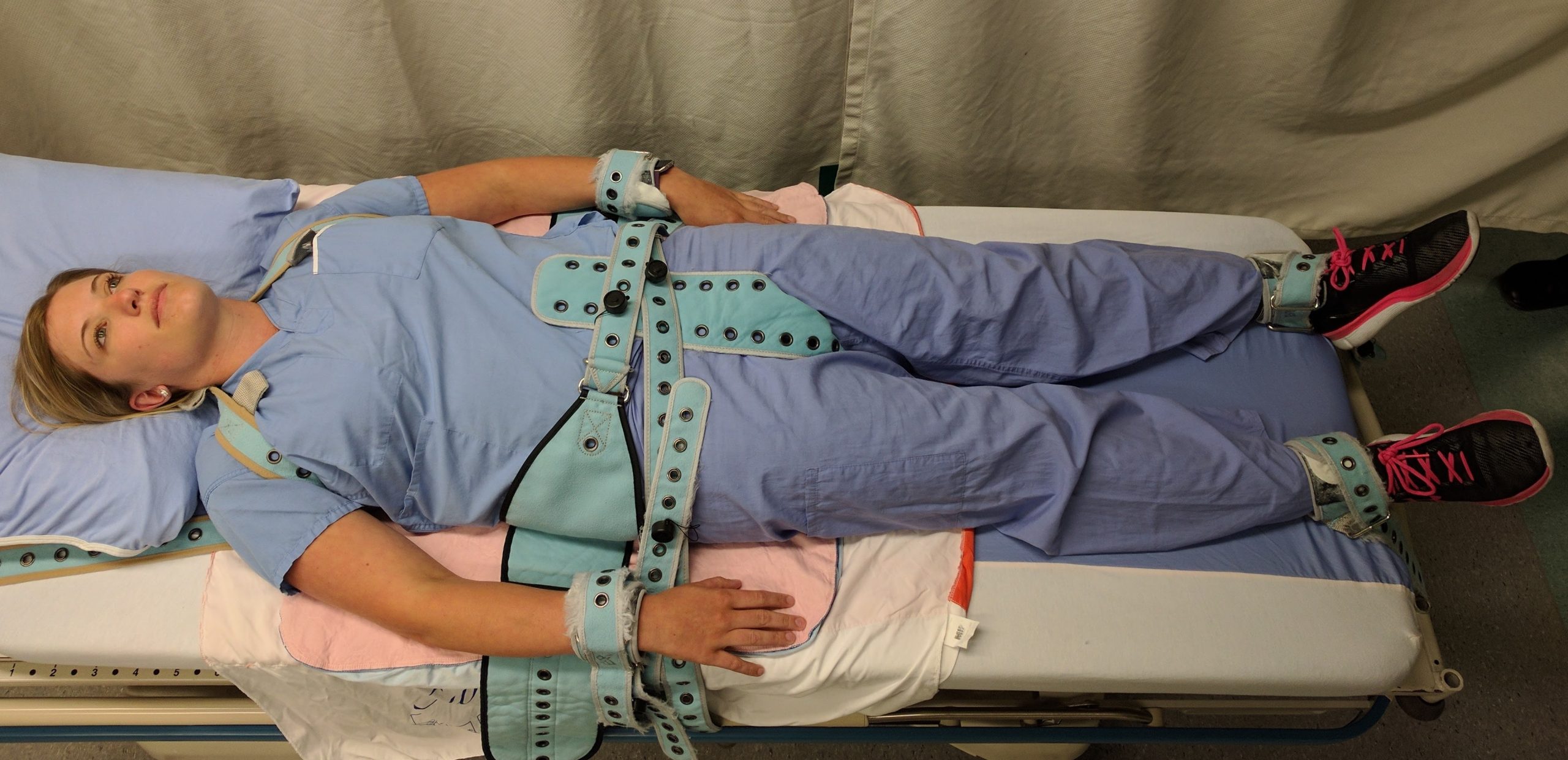

Restraints are devices used in health care settings to prevent clients from causing harm to themselves or others when alternative interventions are not effective. A restraint is a device, method, or process that is used for the specific purpose of restricting a client’s freedom of movement without the permission of the person. See Figure 5.6[24] for an image of a simulated client with restraints applied.

Restraints include mechanical devices such as a tie wrist device, chemical restraints, or seclusion. The Joint Commission defines chemical restraint as a drug used to manage a client’s behavior, restrict the client’s freedom of movement, or impair the client’s ability to appropriately interact with their surroundings that is not standard treatment or dosage for the client’s condition. It is important to note that the definition states the medication “is not standard treatment or dosage for the client’s condition.”[25] Seclusion is defined as the confinement of a client in a locked room from which they cannot exit on their own. It is generally used as a method of discipline for behavior that can cause harm to themselves or others, or as a method of decreasing environmental stimulation. Seclusion limits freedom of movement because, although the client is not mechanically restrained, they cannot leave the area.

Although restraints are used with the intention to keep a client safe, they impact a client’s psychological safety and dignity and can cause additional safety issues and death. A restrained person has a natural tendency to struggle and try to remove the restraint and can fall or become fatally entangled in the restraint. Furthermore, immobility that results from the use of restraints can cause pressure injuries, contractures, and muscle loss. Restraints take a large emotional toll on the client’s self-esteem and may cause humiliation, fear, and anger.

Restraint Guidelines

The American Nurses Association (ANA) has established evidence-based guidelines that state a restraint-free environment is the standard of care. The ANA encourages the participation of nurses to reduce client restraints and seclusion in all health care settings. Restraining or secluding clients is viewed as contrary to the goals and ethical traditions of nursing because it violates the fundamental client rights of autonomy and dignity. However, the ANA also recognizes there are times when there is no viable option other than restraints to keep a client safe, such as during an acute psychotic episode when client and staff safety are in jeopardy due to aggression or assault. The ANA also states that restraints may be justified in some clients with severe dementia or delirium when they are at risk for serious injuries such as a hip fracture due to falling.

The ANA provides the following guidelines: “When restraint is necessary, documentation should be done by more than one witness. Once restrained, the client should be treated with humane care that preserves human dignity. In those instances where restraint, seclusion, or therapeutic holding is determined to be clinically appropriate and adequately justified, registered nurses who possess the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively manage the situation must be actively involved in the assessment, implementation, and evaluation of the selected emergency measure, adhering to federal regulations and the standards of The Joint Commission (2009) regarding appropriate use of restraints and seclusion.”[26] Nursing documentation typically includes information such as client behavior necessitating the restraint, alternatives to restraints that were attempted, the type of restraint used, the time it was applied, the location of the restraint, and client education regarding the restraint.

Medical Restraints

Restraints used to manage nonviolent, non-self-destructive behaviors are referred to as medical restraints. Medical restraints may be appropriate to manage behavior such as the client attempting to remove life-sustaining tubes, drains, IV catheters, urinary catheters, or endotracheal tubes. These types of restraints often include hand mitts or soft wrist restraints. Medical restraints may also be used for clients attempting to get out of bed and as such are a high risk for falls. These types of restraints include siderails, vest restraints, and roll belts. Each facility is required to have a policy in place for the use of medical restraints. Policies typically include requirements for documentation of the reason for the restraint, alternative measures tried, type of restraint applied, behavioral criteria for removal of restraint, range of motion and cares while in restraints, and the date and time the restraint is applied or removed. A medical restraint requires a registered nurse to apply or supervise application of the restraint, a new order every 24 hours, and may never be issued as an as needed order. If the primary care provider did not order the restraint, they should be notified as soon as possible. Medical restraints are more commonly encountered in the general hospital setting rather than behavioral restraints.[27],[28]

Behavioral Restraints

Restraints used to manage violent, self-destructive behaviors are referred to as behavioral restraints. Behavioral restraints are used when clients exhibit behaviors such as hitting or kicking staff or other clients, physically harming themselves or others, or threatening to do so. Behavioral restraints are used in emergency situations where safety concerns need to be immediately addressed to prevent harm. [29]

RNs need special training to apply behavioral restraints, including safe application of the restraint, maintaining personal safety, and techniques to de-escalate the violent or aggressive behavior. Behavioral restraints are typically used in mental health units, emergency departments, or critical care units. Similar to medical restraints, each agency must have a policy in place for the use of behavioral restraints. Health care facilities that accept Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement must also follow federal guidelines for the use of behavioral restraints that include the following:

Guidelines for the use of behavioral restraints include the following:

- When a restraint is the only viable option, it must be discontinued at the earliest possible time.

- Orders for the use of seclusion or restraint can never be written as a standing order or PRN (as needed).

- The treating physician must be consulted as soon as possible if the restraint or seclusion is not ordered by the client’s treating physician.

- A physician or licensed independent practitioner must see and evaluate the need for the restraint or seclusion within one hour after the initiation.

- After restraints have been applied, the nurse should follow agency policy for frequent monitoring and regularly changing the client's position to prevent complications. Nurses must also ensure the client's basic needs (i.e., hydration, nutrition, and toileting) are met. Some agencies require a 1:1 client sitter when restraints are applied.[30]

- Each written order for a physical restraint or seclusion is limited to 4 hours for adults, 2 hours for children and adolescents ages 9 to 17, or 1 hour for clients under 9. The original order may only be renewed in accordance with these limits for up to a total of 24 hours. After the original order expires, a physician or licensed independent practitioner (if allowed under state law) must see and assess the client before issuing a new order.[31]

Side Rails and Enclosed Beds

Side rails and enclosed beds may also be considered a restraint, depending on the purpose of the device. Recall the definition of a restraint as “a device, method, or process that is used for the specific purpose of restricting a clients freedom of movement or access to movement without the permission of the person.” If the purpose of raising the side rails is to prevent a client from voluntarily getting out of bed or attempting to exit the bed, then use of the side rails would be considered a restraint. On the other hand, if the purpose of raising the side rails is to prevent the client from inadvertently falling out of bed, or to help the client with repositioning, then it is not considered a restraint. If a client does not have the physical capacity to get out of bed, regardless if side rails are raised or not, then the use of side rails is not considered a restraint.[32]

Hand Mitts, Soft Limb Restraints, and Vest Restraints

A hand mitt is a large, soft glove that covers a confused client’s hand to prevent them from inadvertently dislodging medical equipment. Hand mitts are considered a restraint by The Joint Commission if used under these circumstances[33]:

- Are pinned or otherwise attached to the bed or bedding

- Are applied so tightly that the client's hands or finger are immobilized

- Are so bulky that the client's ability to use their hands is significantly reduced

- Cannot be easily removed intentionally by the client in the same manner it was applied by staff, considering the client's physical condition and ability to accomplish the objective

Soft limb restraints are a type of medical restraint that is designed to immobilize either one or both arms or legs through application around the wrist(s) or ankle(s). The restraint is made of a soft material designed to minimize the risk of pressure injuries or other injuries. Soft limb restraints are implemented to prevent inadvertent removal of tubes, drains, catheters, or other medical equipment by the client.[34]

Vest restraints are a type of mesh or cloth vest applied over the client's chest and tied to an immovable part of each side of the bed. The purpose of vest restraints is to prevent a client from getting out of bed and injuring themselves. As with any restraint, vest restraints should only be used for impulsive or confused clients when other alternatives are not effective, and not as a means of convenience.[35]

It is important for the nurse to be aware of current best practices and guidelines for restraint use because they are continuously changing. For example, meal trays on chairs were previously used in long-term care facilities to prevent residents from getting out of the chair and falling. However, by the definition of a restraint, this action is now considered a restraint and is no longer used. Instead, several alternative interventions to restraints are now being used.

Alternatives to Restraints

Many alternatives to using restraints in long-term care centers have been developed. Most interventions focus on the individualization of client care and elimination of medications with side effects that cause aggression and the need for restraints. Common interventions used as alternatives to restraints include routine daily schedules, regular feeding times, intentional rounding, frequent toileting, and effective pain management.[36]

Diversionary techniques such as television, music, games, or looking out a window can also be used to help to calm a restless client. Encouraging restless clients to spend time in a supervised area, such as a dining room, lounge, or near the nurses’ station, helps to prevent their desire to get up and move around. If these techniques are not successful, bed and chair alarms or the use of a sitter at the bedside are also considered alternatives to restraints.