Efficacy, Dose-Response, Onset, Peak, and Duration

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Dosing considerations play an important role in understanding the effect that a medication may have on a client. During administration, the nurse must pay close attention to the desired effect and therapeutic response, as well as the safe dose range for any medication.

The nurse should have an understanding of medication efficacy in order to ensure its appropriateness. If a nurse is provided a variety of medication choices according to a provider’s written protocol, the nurse should select the option with the anticipated desired therapeutic response.

Additionally, the nurse must be aware of the overall dose-response based on the dosage selected. Dose response is the dose of medication required to achieve the desired response to the medication. As the dose increases, the response of the drug may increase, as well as the potential for toxicity. This response helps determine the therapeutic index of a drug, or the effective dose range. The measured response and dose are often graphed perpendicular to each other, with the slope of the graph’s curve representing therapeutic index (or overall dose-effect). It is important to note that some medications have a very small therapeutic window, and even small increases in dosages can result in toxic effects. See Figure 1.8[1] for an illustration of a dose-response graph.

Onset, Peak, and Duration

Three additional principles related to the effect a medication has on a client are onset, peak, and duration.

Onset of medication refers to when the medication first begins to take effect. Time of onset is affected by the route of administration. For example, a diuretic given intravenously will begin to take effect much faster than a diuretic administered orally because the intravenous route delivers the drug directly to the systemic circulation and avoids the first-pass effect.

Peak refers to the maximum concentration of medication in the body, and the client shows evidence of greatest therapeutic effect. For example, a client taking ibuprofen can anticipate maximum pain relief in one to two hours when the medication reaches peak serum levels.

Duration refers to the length of time the medication produces its desired therapeutic effect. For example, the duration of oral acetaminophen is four to six hours, at which time the client will likely require an additional dose for pain.

Duration, Dosing, and Steady State

Now let’s consider the implication of duration and dosing. Remember the duration of medication is correlated with the elimination. Half-life is the amount of time that it takes for half of the drug to be eliminated from the body.

If a medication has a short half-life (and is therefore eliminated more quickly from the body), the therapeutic effect is shorter. These medications may require repeated dosing throughout the day in order to achieve steady blood levels of active free drug and a sustained therapeutic effect.

Other medications have a longer half-life (and therefore are eliminated more slowly from the body, resulting in longer therapeutic duration) and may only be administered once or twice per day. For example, oxycodone immediate release is prescribed every 4 to 6 hours for the therapeutic effect of immediate relief of severe pain, whereas oxycodone ER (extended release) is prescribed every 12 hours for the therapeutic effect of sustained relief of severe pain.

Steady state refers to the point at which the amount of drug entering the body is equal to the amount of drug being eliminated, resulting in a stable drug concentration.[2] When steady state is achieved, there is a state of equilibrium in the body and the concentration of the drug remains constant, resulting in optimal therapeutic effect.

Clinical Example

Consider this client care example and apply the principles of onset, peak, and duration: A 67-year-old female postoperative client rings the call light to request medication for pain related to the hip replacement procedure she had earlier that day. She notes her pain is “excruciating, a definite 9 out of 10.” Her brow is furrowed, and she is grimacing in obvious discomfort. As the nurse providing care for the client, you examine her postoperative medication orders and consider the pain medication options available to you. In reviewing the various options, it is important to consider how quickly a medication will work (onset), when the medication will reach maximum effectiveness (peak), and how long the pain relief will last (duration). Understanding these principles is important in effectively relieving the client’s pain and constructing an overall plan of care.

Critical Thinking Activity 1.9

- At 0500, your client who had a total knee replacement yesterday rates his pain while walking as 7 out of 10. Physical therapy is scheduled at 0900. The client has acetaminophen (Tylenol) 625 mg ordered every four hours as needed for discomfort. What should you consider in relation to the administration and timing of the client’s pain medication?

- Your client is prescribed NPH insulin to be given at breakfast and supper. As a student nurse, you know that insulin is used to decrease blood sugar levels in clients with diabetes mellitus. During report, you hear that the client has been ill with GI upset during the night, and the nursing assistant just informed you he refused his breakfast tray. While reviewing this medication order, you consider the purpose of the medication and information related to the medication’s onset, peak, and duration. When reviewing the drug reference, you find the NPH insulin has an onset of about 1 – 3 hours after medication administration. What should you consider in relation to the administration and timing of the client’s insulin?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Media Attributions

- Interactive_dose-response_curve

- ORN-Icons_internet-copy_internet-copy-300×300-1

- "Interactive_dose-response_curve.gif" by Egelberg is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Wadhwa and Cascella and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

To promote safety for clients of all ages, nurses should be knowledgeable about safety risks according to age and developmental stages because the types and frequencies of accidents vary among age groups. Information from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) regarding safety tips for each age group is summarized in the following subsections.[1]

Infants and Preschoolers

Drowning is the leading cause of death in children aged 1-3 years. Motor vehicle accidents, falls, choking, and accidental poisoning are also safety concerns for this age group. Infants and toddlers are curious, but they lack the judgement to recognize the dangers of their actions, so childproofing the home and providing adult supervision are essential for this developmental age group.[2] See Figure 5.7[3] for an image of an infant car seat used to protect infants in the event of a motor vehicle accident. Nurses help educate parents about the proper use, positioning, and installation of car seats.

School-Aged Children

In children aged 4-11, motor vehicle injuries are a major cause of unintentional injury, along with drowning and poisoning. This age group is more aware of dangers and limitations, but adult supervision is still important. The nurse should educate parents of school-aged children about safety seats, booster seats, or shoulder seat belts while riding in the car.[4]

Bicycle accidents are also a common concern in this age group. Many bike accidents involve the head or face because of the lack of helmet use. Nurses provide health teaching to school-aged children regarding bicycle safety and helmet use. See Figure 5.8[5] for an image of a girl wearing a bike helmet.

Because this age group is beginning to enjoy more independence, basic instructions and education on how to recognize and respond to potentially dangerous situations with strangers should also be provided. Parents should also be educated about the AMBER alert system that can be activated if a child is missing and believed to be kidnapped or in danger. This AMBER alert system uses the resources of law enforcement and the media to notify the public about a possible abduction or a missing child in danger.[6]

Nurses must also be aware of signs of maltreatment and child abuse because millions of children are affected each year. Child abuse includes physical, sexual, emotional abuse, and neglect. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), after abuse or violence, many children develop mental health problems, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. These children may also have serious medical problems, learning problems, and problems getting along with friends and family members. Every state has laws that require health care professionals to report suspected child abuse no matter what form this abuse takes.[7]

Adolescents

Motor vehicle accidents are the number one cause of death for adolescents. Teens aged 16-19 are three times more likely to be in a fatal crash than drivers older than age 20. Adolescent males are twice as likely to die in a motor vehicle accident than females of the same age. Texting while driving is a common cause of distracted driving and accidents in adolescents. Because much of an adolescent’s time is spent away from the home, it is difficult for parents to control many of the decisions that adolescents make. Nurses educate teenagers to use seat belts, obey speed limits, and never use a cell phone or text while driving.[8] See Figure 5.9[9] for an image reminding teenage drivers to not text and drive.

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) may occur in this age group due to participation in sports and recreation-related activities. TBI results from a blow, jolt, or hit to the head that causes a disruption in blood function or flow to the brain. Nurses should always be alert for indications of a concussion when a sports injury has occurred. Signs of a concussion requiring immediate medical attention include the following:

- Headache, vomiting, balance problems, fatigue, or drowsiness

- A dazed and confused appearance or difficulty concentrating or remembering; confusion

- Emotional irritability, nervousness, or a change in personality

The CDC has comprehensive information and education materials for parents, coaches, players, and health care providers as part of their “Heads Up” program.[10]

Substance abuse is another significant concern in the adolescent population and includes substances such as tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, prescription medication, over-the-counter medications, and bath salts. The National Institutes of Health provides many resources for educating teens and their parents about substance abuse.[11]

Adults

Intimate partner violence and substance abuse are common safety issues in the adult population.

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is widespread in the United States and is the most prevalent adult safety issue. Intimate partner violence includes physical or sexual violence, stalking, and psychological or coercive aggression by current or former intimate partners. Victims can be female or male, and sexual orientation can be heterosexual or LGBTQ+. The nurse is often the initial health care professional in contact with a victim of IPV. Prompt recognition of a potential or actual threat to client and staff safety is crucial. It is often the nurse’s assessment that plays an important role in identifying a client experiencing IPV. Compassion and understanding are important to show to this vulnerable population. Effective communication is necessary to help victims come forward and share their experiences of abuse. IPV is a complex issue, and the client may not initially consider leaving the abuser as an option. See Figure 5.10[12] for an image of a sign in a community demonstrating support against domestic violence.

See the following tools and resources to share with clients experiencing IPV. For example, the Danger Assessment Tool is a self-administered survey that is free to use and is available in several languages.[13] Nurses can refer clients experiencing IPV to the National Center on Domestic Violence, the Trauma and Mental Health database for resources,[14] and the National Domestic Violence Hotline for free, confidential support.[15] Most importantly, nurses should assist clients experiencing IPV to create a safety plan.

View the tools and resources available at these hyperlinks to share with individuals experiencing intimate partner violence:

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a maladaptive pattern of using alcohol and/or drugs despite it causing persistent social, occupational, psychological, or physical problems that can be physically hazardous. Substance abuse continues to be a safety issue that affects adults across all socioeconomic levels. In America over 450,000 people died between 1999 and 2018 as a result of an opioid overdose.[16] The abuse of prescription pain medication (such as oxycontin and fentanyl) and heroin is a national crisis that plagues social and economic welfare. Substance abuse not only affects an individual, but also causes harm to their family members. Early identification of substance abuse, rehabilitation interventions, and continued support are key for helping the individual, as well as their family members, in the recovery process. See Figure 5.11[17] for an image of a heroin needle found in a community setting.

Older Adults

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, falls and motor vehicle accidents are leading causes of injury in older adults. However, several other issues pose significant hazards for this population, such as fires, accidental overdosing on medications (due to poor eyesight and confusion), elder abuse, and financial exploitation.[18] In most reported cases of elder abuse, a caregiver or a person in trusted relationship is the perpetrator. For various reasons such as fear and disappointment, most of these cases go unreported. Abuse, including neglect and exploitation, is experienced by about 1 in 10 people aged 60 and older who live at home. From 2002 to 2016, more than 643,000 older adults were treated in the emergency department for nonfatal assaults and over 19,000 homicides occurred.[19] Read an example of an older adult experiencing financial exploitation in the following box.

Consider the story of John, a 92-year-old male who lost his wife over a year ago and has been lonely ever since. He lives alone in a large home in the country. John hired a repairman to fix his roof. The repairman befriended John, bringing him homemade cookies and pies and even running errands for him. The repairman often stayed for coffee, and the two of them spent time talking about fishing and gardening. The repairman convinced John to take out a reverse mortgage to pay for additional improvements on his home. Then, knowing John’s bank account numbers and login information, the repairman stole $250,000 that John received for his reverse mortgage.

Most victims of elder abuse are frequently seen in the emergency department several times before they are admitted to the hospital. Nurses must be alert to any indications of elder abuse, such as suspicious injuries or behaviors, and report suspected incidents to local adult protective services agencies. Commons signs of elder abuse or maltreatment include the following[20]:

- Bruises, cuts, burns, or broken bones that are unexplainable or suspiciously explained

- Malnourishment or weight loss

- Poor hygiene, an unkempt appearance, unclean clothing, or dirty, matted hair

- Foul odor from clothing or body

- Anxiety, depression, or confusion

- Unexplained transactions or loss of money

- Withdrawal from family members or friends

View additional resources related to elder abuse in the following box.

Additional resources for older adults suspected as being victims of elder abuse:

In addition to promoting safety for clients and their families, it is important for nurses to be aware of safety risks in the environments and to take measures to protect themselves. Common safety risks to nurses include sharps injuries, exposure to blood-borne pathogens, lifting injuries, and lack of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Workplace Safety

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a healthy environment as a place of physical, mental, and social well-being supporting optimal health and safety. The American Nurses Association (ANA) created the Nurses’ Bill of Rights, a document that sets forth seven basic principles concerning expectations for workplace environments. One of the ANA principles states, “Nurses have the right to a work environment that is safe for themselves and their patients.”[22] Environmental Health is also one of the ANA Standards of Professional Performance. This standard includes "creating a safe and healthy workplace and professional environment."[23]

Preventing Sharps Injuries and Blood-Borne Pathogen Exposure

Exposure to sharps and blood-borne pathogens is a critical safety issue that nurses face in the workplace.[24] Blood-borne pathogen exposure can cause life-threatening illnesses such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. Regulations and laws, such as the Blood-borne Pathogen Standard from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act of 2002, have been effective in significantly reducing sharps injuries and blood exposures among health care workers. Areas covered by these regulations include sharps disposal practices, evaluation and selection of safety-engineered sharps devices and personal protective equipment (PPE), training, record keeping for needlestick injuries, hepatitis B vaccination, and post exposure follow-up. Medical device manufacturers have also played an important role in reducing sharps injury risks to health care workers by developing innovative safety-engineered technology, such as needleless IV access devices.[25] While substantial progress has been made to reduce injuries, preventable sharps injuries and blood exposures continue to occur in health care settings. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), around 385,000 sharps-related injuries occur annually among health care workers in hospitals, but it has been estimated that as many as half of injuries go unreported.[26] See Figure 5.12[27] for an image of a sharps container used to prevent sharps-related injuries.

If you do experience a sharps injury or are exposed to the blood or other body fluid of a client, follow agency and school policy and immediately follow these steps according to the injury site[28]:

- Wash puncture and small wounds with soap and water for 15 minutes.

- Apply direct pressure to lacerations to control bleeding and seek medical attention.

- Flush mucous membranes with water.

- Report the incident to your instructor or supervisor.

- Seek medical care to determine your risk associated with the exposure.

Safe Client Handling

Back injuries and other musculoskeletal disorders can be caused by one bad client lift or from the daily wear and tear of manually lifting clients. At least 56% of nurses have reported pain from musculoskeletal disorders that were exacerbated by requirements of their job. Consequences of these injuries can be devastating to nurses and their careers; musculoskeletal injuries related to client handling are responsible for more lost work time, long-term medical care needs, and permanent disabilities than any other work-related injury. Even using proper body mechanics and the use of gait belts can result in client handling injuries in nurses and health care workers. The ANA has established safe patient handling and mobility initiatives with the goal of complete elimination of manual patient handling.[29] See Figure 5.13[30] for an example of safe client handling equipment.

View these videos on safe client handling and mobility from the ANA:

Personal Protective Equipment

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires employers to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) to their workers and ensure its proper use.[33] In health care settings, the use of PPE includes gloves, gowns, goggles, face shields, and N95 respirators according to a client’s condition. Health care workers rely on personal protective equipment to protect themselves and their clients from being infected and infecting others. It is vital to follow agency procedures regarding PPE and transmission precautions to avoid exposure to infectious disease. See Figure 5.14[34] for an image of health care team members wearing PPE. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic created global shortages of PPE, resulting in many nurses and health care workers being exposed to the fatal disease. The ANA continues to advocate for adequate PPE for nurses in their work environments. Review additional information about PPE using the hyperlink below.

Fire Safety

Health care workers are required to understand fire safety in terms of what to do in the event of a fire, where fire alarms and fire extinguishers are located and how to access them, and where fire doors and fire exits are located. Fire safety is such a crucial aspect of safe client care that The Joint Commission and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid have mandated that all health care facilities receiving Medicare or Medicaid reimbursement must have a fire response plan, fire safety training for staff members, and functioning fire response equipment, such as fire alarms, fire extinguishers, overhead sprinkler systems, and clearly identified fire exit doors. The Joint Commission requires that facilities routinely conduct fire alarm drills as a means of practicing what to do in the event of a fire. These drills must be audited and documented with areas for improvements noted and addressed.[35]

RACE and PASS

Fire safety revolves around the acronyms RACE and PASS. RACE is an acronym that tells people what to do in the event of a fire. PASS is an acronym that tells people how to use a fire extinguisher correctly. Both acronyms are described below.

RACE stands for Rescue, Activate, Confine, and Extinguish[36]:

- Rescue: Rescue anyone in immediate danger. This includes removing clients from the immediate vicinity of the fire, as well as yourself. Maintain your safety while rescuing clients so you do not become a fire victim. This becomes especially important to keep in mind if the fire is between you and the client.

- Activate: Activate the fire alarm. This allows others to realize there is a fire or potential fire so that safety measures can begin immediately. Sometimes the activate step is also stated as “Alarm.”

- Confine: Confine the fire by closing doors and windows. This includes closing fire doors to help prevent the fire from breaching one fire zone and encroaching on another.

- Extinguish or Evacuate: Extinguish small fires if possible. Again, maintain your safety before trying to extinguish a fire. If the fire cannot be easily extinguished, then evacuate the fire zone or the building if necessary.

PASS stands for Pull, Aim, Squeeze, and Sweep[37]:

- Pull: Pull the pin on the fire extinguisher handle. This action is necessary to allow the handle to be depressed and allow fire extinguisher contents to be released.

- Aim: Aim low towards the base of the fire with the fire extinguisher nozzle or hose. It is important to aim the fire extinguisher contents to the base of the fire because this is what will extinguish the fire through smothering. The top part of the fire will not be smothered by the fire extinguisher contents because it is too large and spread out

- Squeeze: Squeeze down on the handle of the fire extinguisher to depress it and allow contents to be released from the extinguisher.

- Sweep: Sweep the hose or nozzle from side to side as the fire extinguisher contents are being sprayed on the base of the fire. This helps to fully cover the base of the fire in the hope of extinguishing it. Continue sweeping the fire extinguisher nozzle, spraying contents at the base of the fire until the fire is extinguished, or the fire extinguisher is empty. If the fire reignites, begin the steps of RACE and PASS again.

Safety Data Sheets

Safety Data Sheets (SDS), formerly referred to as Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS), are hazardous communication sheets that let workers know certain information about chemicals they encounter in the workplace. OSHA requires that SDS’s are readily available and easily readable for each chemical in the workplace. SDS include the following mandatory information[38]:

- Section 1: Identification of the chemical and recommended uses, along with the contact information of the supplier.

- Section 2: Hazard(s) identification, classification of the chemical, and warning information about the hazards present.

- Section 3: Composition and information about ingredients contained in the product, including the chemical name, concentration, and impurities or stabilizing additives that may be present in the product.

- Section 4: First aid measures, including initial care for individuals who have been exposed to the chemical by varying routes.

- Section 5: Firefighting measures, including type of extinguishing equipment required and hazardous combustion products produced if the chemical burns.

- Section 6: Accidental release measures, including and appropriate response to spills or leaks and associated cleanup recommendations.

- Section 7: Handling and storage recommendations for the chemical.

- Section 8: Exposure controls and personal protection required for the chemical.

- Section 9: Physical and chemical properties of the substance.

- Section 10: Stability and reactivity hazards of the chemical.

- Section 11: Toxicological information, including health effects of exposure to the chemical and whether these are immediate, delayed, or chronic effects. Symptoms associated with exposure are also included.

Read more about SDS requirements in this OSHA Brief.

Explore the Healthy Work Environment web page by the American Nursing Association (ANA) for additional strategies that promote safe work environments for nurses, including the Nurses' Bill of Rights and ways to put this plan into action.

Safety strategies have been developed based on research to reduce the likelihood of errors and to create safe standards of care. Examples of safety initiatives include strategies to prevent medication errors, standardized checklists, and structured team communication tools.

Medication Errors

Several initiatives have been developed nationally to prevent medication errors, such as the establishment of a “Do Not Use List of Abbreviations," a “List of Error-Prone Abbreviations,” “Frequently Confused Medication List,” “High-Alert Medications List,” and the “Do Not Crush List.” Additionally, it is considered a standard of care for nurses to perform three checks of the rights of medication administration whenever administering medication. View more information about these safety initiatives to prevent medication errors in the box below. Specific strategies to prevent medication errors are discussed in the “Preventing Medication Errors” of the “Legal/Ethical” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e textbook. The rights of medication administration are discussed in the “Basic Concepts of Administering Medications” section of the “Administration of Enteral Medications” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e textbook.

Read more about safety initiatives implemented to prevent medication errors:

Checklists

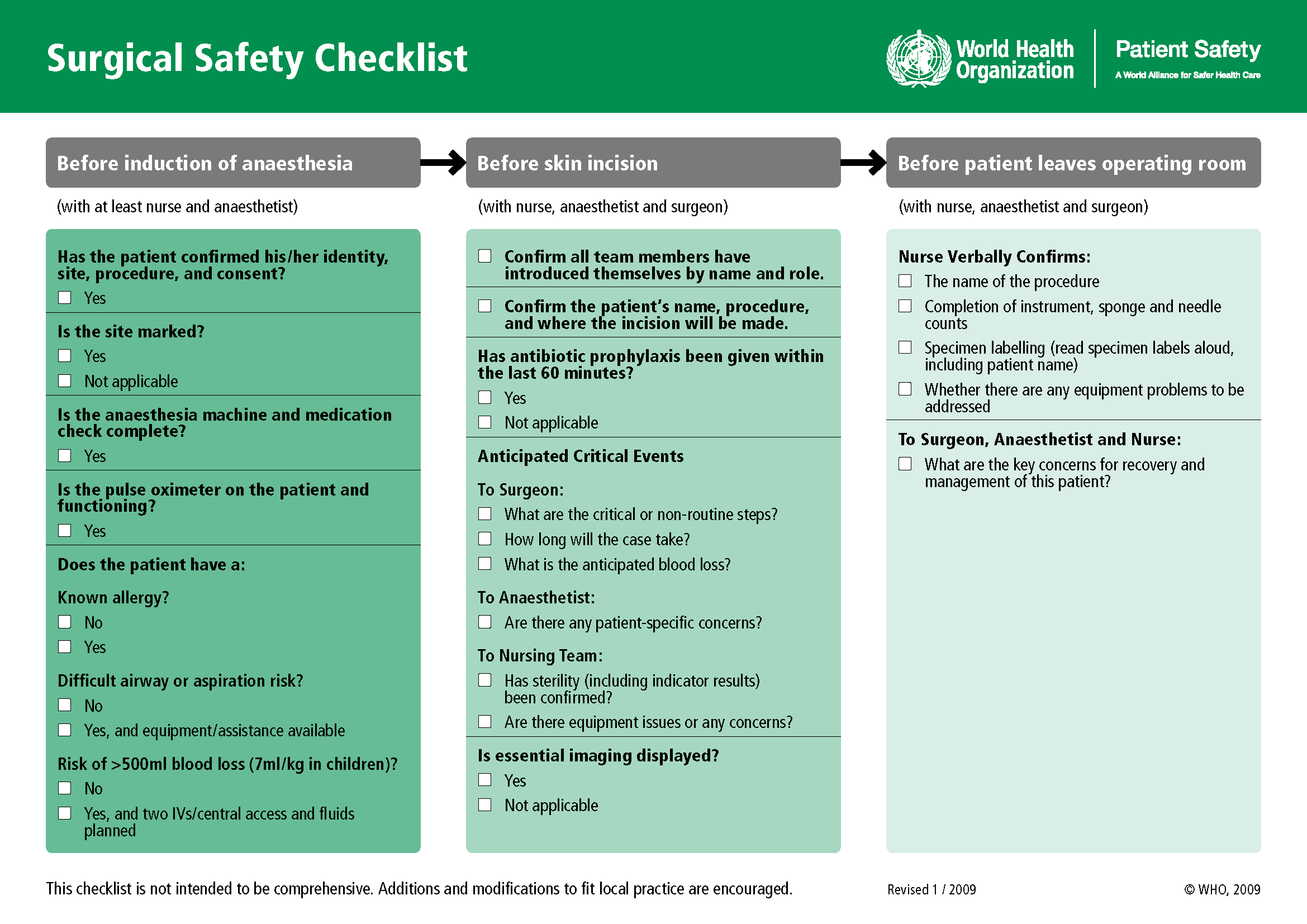

Performance of complex medical procedures is often based on memory, even though humans are prone to short-term memory loss, especially when we are multitasking or under stress. The point-of-care checklist is an example of a client care safety initiative that reduces this reliance on fallible memory. For example, a surgical checklist developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) has been adopted by most surgical providers around the world as a standard of care. It has significantly decreased injuries and deaths caused by surgeries by focusing on teamwork and communication. The Association of PeriOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) combined recommendations from The Joint Commission and the WHO to create a specific surgical checklist for nurses. See Figure 5.2[39] for an image of the WHO surgical checklist.

View an example of a Preop Checklist in the "Preoperative Care" section of the "Perioperative" chapter of Open RN Nursing Health Alterations.

Team Communication

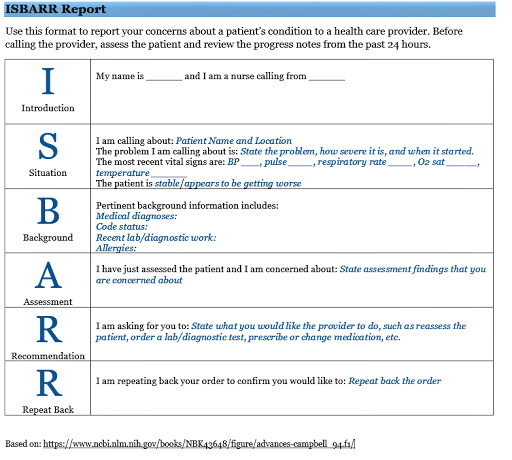

Nurses routinely communicate with multidisciplinary health care team members and contact health care providers to report changes in client status. Serious client harm can occur when client information is absent, incomplete, erroneous, or delayed during team communication. Standardized methods of communication are used to ensure that accurate information is exchanged among team members in a structured and concise manner, such as ISBARR reports and handoff reports.

ISBARR is a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back. See Figure 5.3[40] for an image of an ISBARR reference card.

Handoff reports are a specific type of team communication as client care is transferred. Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as, “A transfer and acceptance of client care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing client specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the client’s care.”[41]

Review information about ISBARR and handoff reports in Chapter 2.4.

In addition to implementing safety strategies to improve safe client care, leaders of a health care agency must also establish a culture of safety. A culture of safety reflects the behaviors, beliefs, and values within and across all levels of an organization as they relate to safety and clinical excellence, with a focus on people. In 2021 The Joint Commission released a sentinel event regarding the essential role of leadership in establishing a culture of safety. According to The Joint Commission, leadership has an obligation to be accountable for protecting the safety of all health care consumers, including clients, employees, and visitors. Without adequate leadership and an effective culture of safety, there is higher risk for adverse events. Inadequate leadership can contribute to adverse effects in a variety of ways, including, but not limited to, the following[42]:

- Insufficient support of client safety event reporting

- Lack of feedback or response to staff and others who report safety vulnerabilities

- Allowing intimidation of staff who report events

- Refusing to consistently prioritize and implement safety recommendations

- Not addressing staff burnout

Three components of a culture of safety are the following[43]:

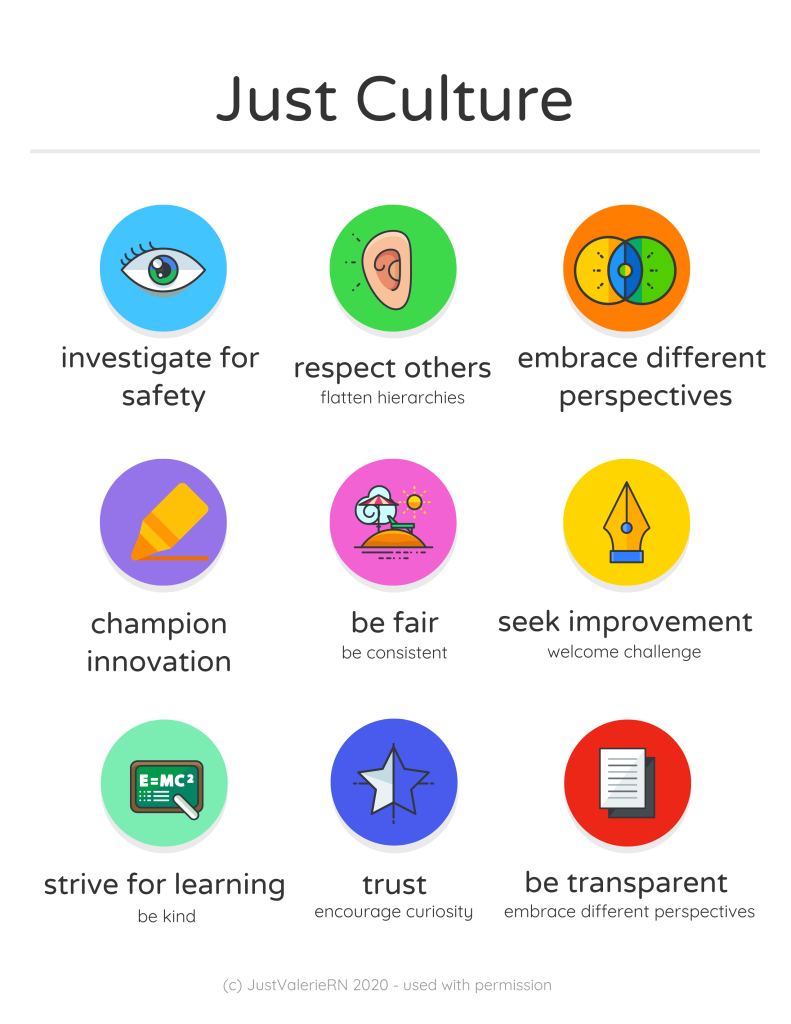

- Just Culture: People are encouraged, even rewarded, for providing essential safety-related information, but clear lines are drawn between human error and at-risk or reckless behaviors.

- Reporting Culture: People report errors and near-misses.

- Learning Culture: The willingness and the competence to draw the right conclusions from safety information systems, and the will to implement major reforms when their need is indicated.

The American Nurses Association further describes a culture of safety as one that includes openness and mutual respect when discussing safety concerns and solutions without shifting to individual blame, a learning environment with transparency and accountability, and reliable teams. In contrast, complexity, lack of clear measures, hierarchical authority, the “blame game,” and lack of leadership are examples of barriers that do not promote a culture of safety. If staff fear reprisal for mistakes and errors, they will be less likely to report errors, processes will not be improved, and client safety will continue to be impaired. See the following box for an example of safety themes established during a health care institution’s implementation of a culture of safety.

Safety Themes in a Culture of Safety[44]

Kaiser Permantente implemented a culture of safety in 2001 that focused on instituting the following six strategic themes:

- Safe culture: Creating and maintaining a strong safety culture, with client safety and error reduction embraced as shared organizational values.

- Safe care: Ensuring that the actual and potential hazards associated with high-risk procedures, processes, and client care populations are identified, assessed, and managed in a way that demonstrates continuous improvement and ultimately ensures that clients are free from accidental injury or illness.

- Safe staff: Ensuring that staff possess the knowledge and competence to perform required duties safely and contribute to improving system safety performance.

- Safe support systems: Identifying, implementing, and maintaining support systems—including knowledge-sharing networks and systems for responsible reporting—that provide the right information to the right people at the right time.

- Safe place: Designing, constructing, operating, and maintaining the environment of health care to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness.

- Safe clients: Engaging clients and their families in reducing medical errors, improving overall system safety performance, and maintaining trust and respect.

A strong safety culture encourages all members of the health care team to identify and reduce risks to client safety by reporting errors and near misses so that root cause analysis can be performed and identified risks are removed from the system. However, in a poorly defined and implemented culture of safety, staff often conceal errors due to fear or shame. Nurses have been traditionally trained to believe that clinical perfection is attainable, and that “good” nurses do not make errors. Errors are perceived as being caused by carelessness, inattention, indifference, or uninformed decisions. Although expecting high standards of performance is appropriate and desirable, it can become counterproductive if it creates an expectation of perfection that impacts the reporting of errors and near misses. If employees feel shame when they make an error, they may feel pressure to hide or cover up errors. Evidence indicates that approximately three of every four errors are detected by those committing them, as opposed to being detected by an environmental cue or another person. Therefore, employees need to be able to trust that they can fully report errors without fear of being wrongfully blamed. This provides the agency with the opportunity to learn how to further improve processes and prevent future errors from occurring. For many organizations, the largest barrier in establishing a culture of safety is the establishment of trust. A model called “Just Culture” has successfully been implemented in many agencies to decrease the “blame game,” promote trust, and improve the reporting of errors.

Just Culture

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture, stating, “Traditionally, healthcare’s culture has held individuals accountable for all errors or mishaps that befall clients under their care. By contrast, a Just Culture recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. A Just Culture also recognizes many individual or ‘active’ errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, in contrast to a culture that touts ‘no blame’ as its governing principle, a Just Culture does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to clients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).”

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three causes of errors. Consequences of errors are based on whether the error is a simple human error or caused by at-risk or reckless behavior.

- Simple human error: A simple human error occurs when an individual inadvertently does something other than what should have been done. Most medical errors are the result of human error due to poor processes, programs, education, environmental issues, or situations. These errors are managed by correcting the cause, looking at the process, and fixing the deviation. For example, a nurse appropriately checks the rights of medication administration three times, but due to the similar appearance and names of two different medications stored next to each other in the medication dispensing system, administers the incorrect medication to a client. In this example, a root cause analysis reveals a system issue that must be modified to prevent future errors (e.g., change the labelling and storage of look alike-sound alike medication).

- At-risk behavior: An error due to at-risk behavior occurs when a behavioral choice is made that increases risk where the risk is not recognized or is mistakenly believed to be justified. For example, a nurse scans a client’s medication with a barcode scanner prior to administration, but an error message appears on the scanner. The nurse mistakenly interprets the error to be a technology problem and proceeds to administer the medication instead of stopping the process and further investigating the error message, resulting in the wrong dosage of a medication being administered to the client. In this case, ignoring the error message on the scanner can be considered “at-risk behavior” because the behavioral choice was considered justified by the nurse at the time.

- Reckless behavior: Reckless behavior is an error that occurs when an action is taken with conscious disregard for a substantial and unjustifiable risk.[45] For example, a nurse arrives at work intoxicated and administers the wrong medication to the wrong client. This error is considered due to reckless behavior because the decision to arrive intoxicated was made with conscious disregard for substantial risk.

These examples show three different causes of medication errors that would result in different consequences to the employee based on the Just Culture model. Under the Just Culture model, after root cause analysis is completed, system-wide changes are made to decrease factors that contributed to the error. Managers appropriately hold individuals accountable for errors if they were due to simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behaviors.

If an individual commits a simple human error, managers console the individual and consider changes in training, procedures, and processes. In the “simple human error” above, system-wide changes would be made to change the label and location of the medication to prevent future errors from occurring with the same medication.

Individuals committing at-risk behavior are held accountable for their behavioral choice and often require coaching with incentives for less risky behaviors and situational awareness. In the “at-risk behavior” example above where the nurse ignored an error message on the barcode scanner, mandatory training on using a barcode scanner and responding to errors would be implemented, and the manager would track the employee’s correct usage of the barcode scanner for several months following training.

If an individual demonstrates reckless behavior, remedial action and/or punitive action is taken.[46] In the “reckless behavior” example above, the manager would report the nurse’s behavior to the state's Board of Nursing with mandatory substance abuse counseling to maintain their nursing license. Employment may be terminated with consideration of patterns of behavior.

A Just Culture in which employees aren't afraid to report errors is a highly successful way to enhance client safety, increase staff and client satisfaction, and improve outcomes. Success is achieved through good communication, effective management of resources, and an openness to changing processes to ensure the safety of clients and employees. The infographic in Figure 5.4[47] illustrates the components of a culture of safety and Just Culture.

The principles of culture of safety, including Just Culture, Reporting Culture, and Learning Culture are also being adopted in nursing education. It’s understood that mistakes are part of learning and that a shared accountability model promotes individual- and system-level learning for improved client safety. Under a shared accountability model, students are responsible for the following[48]:

- Being fully prepared for clinical experiences, including laboratory and simulation assignments

- Being rested and mentally ready for a challenging learning environment

- Accepting accountability for their part in contributing to a safe learning environment

- Behaving professionally

- Reporting their own errors and near mistakes

- Keeping up-to-date with current evidence-based practice

- Adhering to ethical and legal standards

Students know they will be held accountable for their actions, but will not be blamed for system faults that lie beyond their control. They can trust that a fair process will be used to determine what went wrong if a client care error or near miss occurs. Student errors and near misses are addressed based on an investigation determining if it was simple human error, an at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. For example, a simple human error by a student can be addressed with coaching and additional learning opportunities to remedy the knowledge deficit. However, if a student acts with recklessness (for example, repeatedly arrives to clinical unprepared despite previous faculty feedback or falsely documents an assessment or procedure), they are appropriately and fairly disciplined, which may include dismissal from the program.[49]

Every year, national safety goals are published by The Joint Commission to improve clientsafety. National Patient Safety Goals are goals and recommendations tailored to seven different types of health care agencies based on client safety data from experts and stakeholders. The seven health care areas include ambulatory health care settings, behavioral health care settings, critical access hospitals, home care, hospital settings, laboratories, nursing care centers, and office-based surgery settings. These goals are updated annually based on safety data and include evidence-based interventions. It is important for nurses and nursing students to be aware of the current National Patient Safety Goals for the settings in which they provide client care and use the associated recommendations.

The National Patient Safety Goals for nursing care settings (otherwise known as long-term care centers) are described in Table 5.5. (Note that the term “bedsore” is used in the last goal. This is a historic term for the current term “pressure injuries.”)

Table 5.5 National Patient Safety Goals for Nursing Care Centers[50]

| Goal | Recommendations and Rationale |

|---|---|

| Identify residents correctly | Use at least two ways to identify clients. For example, use the client’s or resident’s name and date of birth. This is done to make sure that each client gets the correct medication and treatment. |

| Use medicines safely | Take extra care with clients who take medications to thin their blood.

Record and pass along correct information about a client’s medications. Find out what medications the client is taking. Compare those medications to new medications prescribed for the client. Give the client written information about the medications they need to take. Tell the client it is important to bring their up-to-date list of medications every time they visit a doctor. |

| Prevent infection | Use the hand hygiene guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the World Health Organization. Set goals for improving hand cleaning. |

| Prevent residents from falling | Find out which clients are most likely to fall. For example, is the client taking any medications that might make them weak, dizzy, or sleepy? Implement fall precautions for these clients. |

| Prevent bed sores | Find out which clients are most likely to have bed sores (i.e., pressure injuries). Take action to prevent pressure injuries in these clients at risk. Per agency protocol, frequently assess clients for pressure injuries. |

Read more about National Patient Safety Goals established by The Joint Commission.

Read more details about how to identify clients correctly, administer medications safely, and prevent infection by visiting the following sections in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e:

- Initiating Patient Interaction

- Aseptic Technique Basic Concepts

- Basic Concepts of Administering Medications

Read more about "Pressure Injuries" (the current term used for "bed sores") in the "Integumentary" chapter of this book.

The part of the nervous system that includes the brain (the interpretation center) and the spinal cord (the transmission pathway).