Pharmacodynamics

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Pharmacodynamics

So far in this chapter, we have learned the importance of pharmacokinetics in how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes a medication. Now let’s consider how drugs act on target sites of action in the body, referred to as pharmacodynamics.

Mechanism of action is a medical term that describes how a medication works in the body. For example, did you know that an osmotic laxative like magnesium citrate attracts and binds with water? The mechanism of action for this medication is it pulls water into the bowel, which softens stool and increases the likelihood of a bowel movement.

A drug’s mechanism of action may refer to how it affects a specific receptor. Many drugs bind to specific receptors on the surface of cells to cause an action. For example, morphine binds to a specific receptor that inhibits transmission of nerve impulses along the pain pathway and decreases a client’s feelings of pain.

Other medications inhibit specific enzymes for a desired effect. For example, earlier in this chapter we discussed how monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are prescribed as antidepressants because they block monoamine oxidase, the enzyme that breaks down serotonin and dopamine. This blockage increases the concentration of serotonin and dopamine in the central nervous system and increases a client’s feelings of pleasure.

Agonist and Antagonist Actions

Drugs have agonistic or antagonistic effects on receptor sites. An agonist binds tightly to a receptor to produce a desired effect. An antagonist competes with other molecules and blocks a specific action or response at a receptor site. See Figure 1.7[1] for an illustration of how a beta-blocker, an antagonist cardiac medication, blocks specific action on the beta receptors of a cardiac cell.

Agonistic and antagonistic effects on receptors for common classes of medications are further discussed in the “Autonomic Nervous System” chapter.

Critical Thinking Activity 1.7

Atenolol (Tenormin) is an antagonist medication. Does the nurse anticipate this will cause a specific action or block a specific action at a receptor site?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Media Attributions

- Mechanism of Action © Dominic Slauson

- ORN-Icons_internet-copy_internet-copy-300×300-1

- “Mechanism of Action” by Dominic Slausen at Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

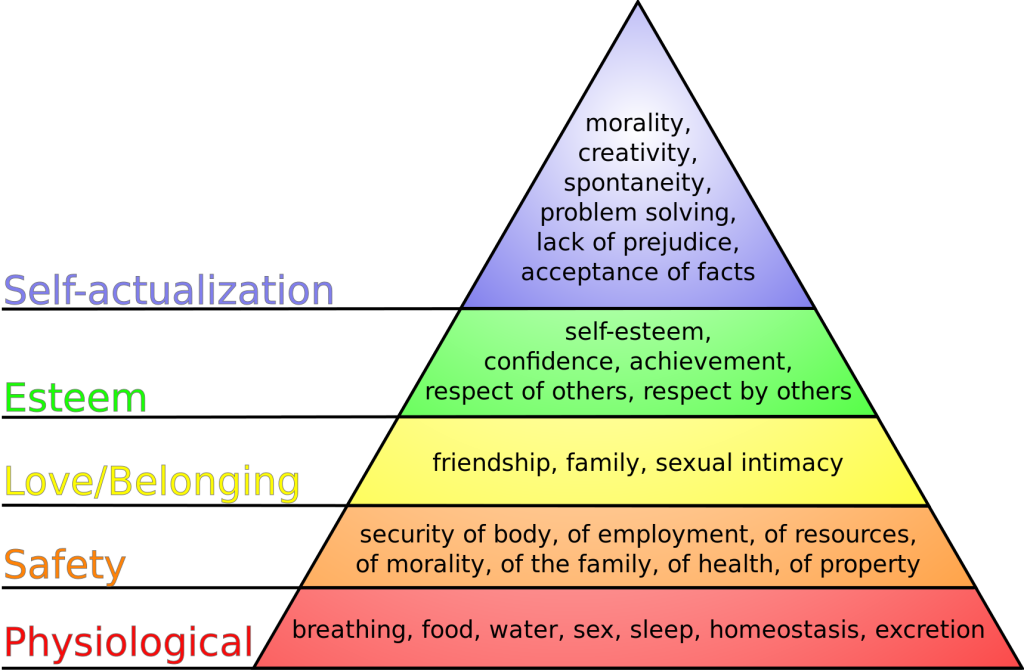

Safety: A Basic Need

Safety is a basic foundational human need and always receives priority in client care. Nurses typically use Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to prioritize urgent client needs, with the bottom two rows of the pyramid receiving top priority. See Figure 5.1[1] for an image of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Safety is intertwined with basic physiological needs.

Consider the following scenario: You are driving back from a relaxing weekend at the lake and come upon a fiery car crash. You run over to the car to help anyone inside. When you get to the scene, you notice that the lone person in the car is not breathing. Your first priority is not to initiate rescue breathing inside the burning car, but to move the person to a safe place where you can safely provide CPR.

In nursing, the concept of client safety is central to everything we do in all health care settings. As a nurse, you play a critical role in promoting client safety while providing care. You also teach clients and their caregivers how to prevent injuries and remain safe in their homes and in the community. Safe client care also includes measures to keep you safe in the health care environment; if you become ill or injured, you will not be able to effectively care for others.

Safe client care is a commitment to providing the best possible care to every client and their caregivers in every moment of every day. Clients come to health care facilities expecting to be kept safe while they are treated for illnesses and injuries. Unfortunately, you may have heard stories about situations when that did not happen. Medical errors can be devastating to clients and their families. Consider the true story in the following box that illustrates factors affecting client safety.

The Josie King Story

In 2001, 18-month-old Josie King died as a result of medical errors in a well-known hospital from a hospital-acquired infection and an incorrectly administered pain medication. How did this preventable death happen? Watch this video of her mother, Sorrel King, telling Josie’s story and explaining how Josie’s death spurred her work on improving client safety in hospitals everywhere.[2]

Reflective Questions:

- What factors contributed to Josie’s death?

- How could these factors be resolved?

Never Events

The event described in the Josie King story is considered a “never event.” Never events are adverse events that are clearly identifiable, measurable, serious (resulting in death or significant disability), and preventable. In 2007 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) discontinued payment for costs associated with never events, and this policy has been adopted by most private insurance companies. Never events are publicly reported, with the goal of increasing accountability by health care agencies and improving the quality of client care. The current list of never events includes seven categories of events:

- Surgical or procedural event, such as surgery performed on the wrong body part

- Product or device, such as injury or death from a contaminated drug or device

- Client protection, such as client suicide in a health care setting

- Care management, such as death or injury from a medication error

- Environmental, such as death or injury as the result of using restraints

- Radiologic, such as a metallic object in an MRI area

- Criminal, such as death or injury of a client or staff member resulting from physical assault on the grounds of a health care setting

Sentinel Events

Sentinel events are very similar to never events although they may not be entirely preventable. They are defined by The Joint Commission as an “A client safety event that reaches a client and results in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm requiring interventions to sustain life." Such events are called "sentinel" because they signal the need for immediate investigation and response. Each accredited organization is strongly encouraged, but not required, to report sentinel events to The Joint Commission.[3] It is helpful to facilities to self-report sentinel events so that other facilities can learn from these events and future sentinel events can be prevented through knowledge sharing and risk reduction. Investigations into sentinel events are typically achieved through a process called root cause analysis.

Root cause analysis is a structured method used to analyze serious adverse events to identify underlying problems that increase the likelihood of errors, while avoiding the trap of focusing on mistakes by individuals. A multidisciplinary team analyzes the sequence of events leading up to the error with the goal of identifying how and why the event occurred. The ultimate goal of root cause analysis is to prevent future harm by eliminating hidden problems within a health care system that contribute to adverse events. For example, when a medication error occurs, a root cause analysis goes beyond focusing on the mistake by the nurse and looks at other system factors that contributed to the error, such as similar-looking drug labels, placement of similar-looking medications next to each other in a medication dispensing machine, or vague instructions in a provider order.

Root cause analysis uses human factors science as part of the investigation. Human factors focus on the interrelationships among humans, the tools and equipment they use in the workplace, and the environment in which they work. Safety in health care is ultimately dependent on humans - the doctors, nurses, and health care professionals - providing the care.

Near Misses

In addition to investigating sentinel events and never events, agencies use root cause analysis to investigate near misses. Near misses are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as, “An error that has the potential to cause an adverse event (client harm) but fails to do so because of chance or because it is intercepted.” Errors and near misses are rarely the result of poor motivation or incompetence of the health care professional but are often caused by key contributing factors such as poor communication, less-than-optimal teamwork, memory overload, reliance on memory for complex procedures, and lack of standardization of policies and procedures. In an effort to prevent near misses, medical errors, sentinel events, and never events, several safety strategies have been developed and implemented in health care organizations across the country. These strategies will be discussed throughout the remainder of the chapter.

Incident Reports and Client Safety

Recall from the previous discussion in Chapter 2.5 that an incident report is a specific type of documentation performed when there is an error, near miss, or other unexpected occurrence that occurs during client care. Incident reports are used to identify process problems or other areas that could benefit from safety and quality improvement and are not included in the client's medical record. They are a component of an agency's culture of safety and are used during investigations like root cause analysis to help improve the safety and quality of client care.