Sensory Impairments Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) and Amy Ertwine

Interpreting Sensations

Before learning about sensory function, it is important to understand how the nervous system works. An intact nervous system is necessary for information to be delivered from the environment to the brain to trigger responses from the body. For neurons to transmit these messages, they are in the form of an action potential. Sensory receptors perceive a stimulus and then change the sensation to an electrical signal so that it can be transmitted to the brain and then out to the body. For example, a pain receptor perceives pain as your hand touches a hot tray. The signal is transmitted to the brain where it is interpreted, and then signals are quickly sent to the hand to pull away from the hot stimuli.[1]

Our bodies interpret sensations through a process using reception, perception, and reaction. Reception is the first part of the sensory process when a nerve cell or sensory receptor is stimulated by a sensation. Sensory receptors are activated by mechanical, chemical, or temperature stimuli. In addition to our five senses, we also have somatosensation. Somatosensation refers to sensory receptors that respond to stimuli such as pain, pressure, temperature, and vibration. It also includes vestibular sensation, a sense of spatial orientation and balance, and proprioception, the sense of the position of our bones, joints, and muscles. Although these sensory systems are all very different, they share a common purpose. They change a stimulus into an electrical signal that is transmitted in the nervous system.[2]

The sensory receptors for each of our senses work differently from one another. Light receptors, sound receptors, and touch receptors are each activated by different stimuli with specialized receptor specificity. For example, touch receptors are sensitive to pressure but do not have sensitivity to sound or light. Nerve impulses from sensory receptors travel along pathways to the spinal cord or directly to the brain. Some stimuli are also combined in the brain, such as our sense of smell that can affect our sense of taste.[3]

As an individual becomes aware of a stimulus and it is transmitted to the brain, perception occurs. Perception is the interpretation of a sensation. All sensory signals, except olfactory system input, are transmitted to the thalamus and to the appropriate region of the cortex of the brain. The thalamus, which is in the forebrain, acts as a relay station for sensory and motor signals. When a sensory signal leaves the thalamus, it is sent to the specific area of the cortex that processes that sense.[4] However, conditions that affect a person’s consciousness also affect the ability to perceive and interpret stimuli.

Reaction is the response that individuals have to a perception of a received stimulus. The brain determines what sensations are significant because it is impossible to react to all stimuli that are constantly received from our environment. A healthy brain maintains a balance between sensory stimuli received and those reaching awareness. However, sensory overload can occur if the amount of stimuli the brain is receiving is overwhelming to an individual. Sensory deprivation can also occur if there are insufficient sensations from the environment.[5]

Sensory Impairment

Alterations in sensory function include sensory impairment, sensory overload, and sensory deprivation. Sensory impairment includes any type of difficulty that an individual has with one of their five senses. When an individual experiences loss of a sensory function, such as vision, the way they interact with the environment is affected. For example, when an individual gradually loses their vision, their reliance on other senses to receive information from the environment is often enhanced.

Safety is always a nursing consideration for a client with a sensory impairment. Intact senses are required to make decisions about functioning safely within the environment. For example, an individual who has impaired hearing may not be able to hear a smoke alarm and requires visual indicators when the alarm is triggered.

Sensory impairments are very common in older adults. Most older adults develop impaired near vision called presbyopia, resulting in the need for reading glasses. See Figure 7.2[6] for an image of simulated presbyopia.

Deficits in taste and smell are also prevalent in this age group. Additionally, kinesthetic impairment (an altered sense of touch) can occur in adults as young as 55. Kinesthetic impairment can cause difficulty in daily functioning, such as buttoning one’s shirt or performing other fine motor tasks. These sensory losses can greatly impact how older adults live and function.[7]

Vision Impairments

Several types of visual impairments commonly occur in older adults, including macular degeneration, cataracts, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and presbyopia. See Table 7.2 for more information about each of these visual conditions.

Table 7.2 Common Visual Conditions

| Macular Degeneration | Macular degeneration is the leading cause of legal blindness in individuals over 60 years of age. Risk factors include advancing age, a positive family history, hypertension, and smoking. In macular degeneration, there is loss of central vision with classic symptoms such as blurred central vision, distorted vision that causes difficulty driving and reading, and the requirement for brighter lights and magnification for close-up visual activities.[8] |

|---|---|

| Cataracts | Cataracts are the opacity of the lens of the eye that causes clouded, blurred, or dimmed vision. About half of individuals ages 65 to 75 will develop cataracts, with further incidence occurring after age 75. Cataracts can be removed with surgery that replaces the lens with an artificial lens.[9] |

| Glaucoma | Glaucoma is caused by elevated intraocular pressure that leads to progressive damage to the optic nerve, resulting in gradual loss of peripheral vision. It affects about 4% of individuals over age 70.[10] |

| Diabetic Retinopathy | Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness in adults diagnosed with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic retinopathy is a complication of diabetes mellitus due to damaged blood vessels in the retina causing vision loss.[11] Clients with diabetes are encouraged to receive annual eye exams so that retinopathy can be discovered and treated early. Treatments, such as laser treatment that can help shrink blood vessels, injections that can reduce swelling, or surgery, can prevent permanent vision loss.[12] |

| Presbyopia | As a person ages, the lens of the eye gradually becomes thicker and loses flexibility. It stops focusing light on the retina correctly, causing impaired near vision and accommodation at all distances. Presbyopia starts in the early to mid-forties and worsens with aging. It can lead to significant visual impairment but does not usually cause blindness.[13] |

Hearing Loss and Ear Problems

Approximately one third of individuals aged 70 and older have hearing loss. Good hearing depends on a series of events that change sound waves in the air into electrical signals. The auditory nerve conducts these electrical signals from the ear to the brain through a series of steps. The structures of the ear, such as the tympanic membrane and cochlea, must be intact and functioning appropriately for conduction of sound to occur. Age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) gradually occurs in most individuals as they age.[14] Typically, low-pitched sounds are easiest to hear, but it often becomes increasingly difficult to hear normal conversation, especially over loud background noise. Hearing aids are commonly used to enhance hearing. See Figure 7.3[15] for an image of common hearing aids used to treat hearing loss.

Hearing loss can be caused by other factors in addition to aging. A build-up of ear wax in the ear canal can cause temporary hearing loss. Sounds that are too loud or long-term exposure to loud noises can cause noise-induced hearing loss. For example, a loud explosion or employment using loud machinery without ear protection can damage the sensory hair cells in the ear. After these hair cells are damaged, the ability to hear is permanently diminished. Tinnitus, a medical term for ringing in the ears, can also occur. Some medications, such as high doses of aspirin or loop diuretics, can cause toxic effects to the sensory cells in the ear and lead to hearing loss or tinnitus.[16],[17] In addition to hearing loss, ear problems can also cause problems with balance, dizziness, and vertigo due to vestibular dysfunction.

Kinesthetic Impairments

Kinesthetic impairments, such as peripheral neuropathy, affect the ability to feel sensations. Symptoms of peripheral neuropathy include sensations of pain, burning, tingling, and numbness in the extremities that decrease a person’s ability to feel touch, pressure, and vibration. Position sense can also be affected and makes it difficult to coordinate complex movements, such as walking, fastening buttons, or maintaining balance when one’s eyes are closed. Peripheral neuropathy is caused by nerve damage that commonly occurs in clients with diabetes mellitus or peripheral vascular disease. It can also be caused by physical injuries, infections, autoimmune diseases, vitamin deficiencies, kidney diseases, liver diseases, and certain medications like chemotherapy medications.[18]

Life Span Considerations

Impaired sensory functioning increases the risk for social isolation in older adults. For example, when individuals are not able to hear well, they may pretend to hear in an attempt to avoid embarrassment when asking for the information to be repeated. They may begin to avoid noisy environments or stop participating socially in conversations around them.

Infants and children are also at risk for vision and hearing impairments related to genetic or prenatal conditions. Early determination of sensory impairments is crucial so that problems can be addressed with accommodations to minimize the impact on a child’s development. For example, a screening hearing test is completed on all newborns before discharge to evaluate for hearing impairments that can affect their speech development.

Sensory Overload and Sensory Deprivation

Stimuli are continually received from a variety of sources in our environment and from within our bodies. When an individual receives too many stimuli or cannot selectively filter out meaningful stimuli, sensory overload can occur. Symptoms of sensory overload include irritability, restlessness, covering ears or eyes to shield them from sensory input, and increased sensitivity to tactile input (i.e., scratchy fabric or sensations of medical equipment).[19] Sensory overload affects an individual’s ability to interpret stimuli from their environment and can lead to confusion and agitation. See Figure 7.4[20] of an image of a client reacting to sensory overload.

The health care environment with its frequent noisy alarms, treatments, staff interruptions, and noisy hallway conversations can cause sensory overload for clients. Additionally, the amount of information provided to a client experiencing a health crisis can contribute to sensory overload, such as teaching about procedural and diagnostic testing. Clients may only be able to process small chunks of information provided at a time and may need this information repeated to ensure they understand their situation and retain the information.

Individuals have different tolerances for the amount of stimuli that will affect them adversely. Tolerance to stimuli is impacted by factors such as pain, stress levels, sleep patterns, physical health, and emotional health. When sensory overload occurs in a hospitalized client, it can lead to delirium and acute confusion. It is important for the nurse to limit unnecessary awakenings and interactions with the health care team members when a client is experiencing sensory overload.

Conversely, symptoms of sensory deprivation may occur when there is a lack of sensations due to sensory impairments or few quality stimuli in the client environment. This may include hearing or vision impairments, brain or spinal injuries resulting in lack of tactile sensations, having few or no visitors, or having transmission-based precautions resulting in decreased staff interaction. Interventions such as opening window curtains, providing a clock and calendar for orientation to the time and the day of the week, encouraging visitors, and spending additional time with the client can help prevent sensory deprivation.

Clients with sensory deprivation may experience excessive tiredness or lethargy, disorientation, depression or apathy. People experiencing sensory deprivation often report perceptual disturbances such as hallucinations. Symptoms of sensory deprivation can mimic delirium, so it is important for a nurse to further investigate new perceptual disturbances.[21]

Review information on delirium in Chapter 6.2.

Media Attributions

- Pesto ingredients – blurred

- Traditional_hearing_aids

- Sensory_Overload

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Gadhvi & Waseem and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Sensory Processes by Lumen Learning and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Sensory Processes by Lumen Learning and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Sensory Processes by Lumen Learning and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Sensory Processes by Lumen Learning and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Pesto ingredients - blurred.jpg” by Colin is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Correia, C., Lopez, K. J., Wroblewski, K. E., Huisingh-Scheetz, M., Kern, D. W., Chen, R. C., Schumm, L. P., Dale, W., McClintock, M. K., & Pinto, J. M. (2016). Global sensory impairment in older adults in the United States. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(2), 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13955 ↵

- Loh, K. Y., & Ogle, J. (2004). Age related visual impairment in the elderly. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 59(4), 562–569. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15779599/ ↵

- Loh, K. Y., & Ogle, J. (2004). Age related visual impairment in the elderly. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 59(4), 562–569. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15779599/ ↵

- Loh, K. Y., & Ogle, J. (2004). Age related visual impairment in the elderly. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 59(4), 562–569. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15779599/ ↵

- Loh, K. Y., & Ogle, J. (2004). Age related visual impairment in the elderly. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 59(4), 562–569. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15779599/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Vision loss and diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/diabetes-complications/diabetes-and-vision-loss.html ↵

- Loh, K. Y., & Ogle, J. (2004). Age related visual impairment in the elderly. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 59(4), 562–569. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15779599/ ↵

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2024). Age-related hearing loss (Presbycusis). https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/age-related-hearing-loss ↵

- “Traditional_hearing_aids.jpg” by ikesters is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2018, July 17). Age-related hearing loss. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/age-related-hearing-loss ↵

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Causes of hearing loss in adults. https://www.asha.org/public/hearing/causes-of-hearing-loss-in-adults/ ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Peripheral neuropathy. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/peripheral-neuropathy ↵

- Watson, K. (2018, September 27). What is sensory overload? https://www.healthline.com/health/sensory-overload#causes ↵

- “Sensory_Overload.jpg” by Stewart Black is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Mason, O., & Brady, F. (2009). The psychotomimetic effects of short-term sensory deprivation. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(10), 783-785. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0b013e3181b9760b ↵

The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines morality as “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals or groups within communities and societies,” whereas ethics is the formal study of morality from a wide range of perspectives.[1] Ethical behavior is considered to be such an important aspect of nursing the ANA has designated Ethics as the first Standard of Professional Performance. The ANA Standards of Professional Performance are "authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently." See the following box for the competencies associated with the ANA Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[2]:

Competencies of ANA's Ethics Standard of Professional Performance[3]

- Uses the Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements as a moral foundation to guide nursing practice and decision-making.

- Demonstrates that every person is worthy of nursing care through the provision of respectful, person-centered, compassionate care, regardless of personal history or characteristics (Beneficence).

- Advocates for health care consumer perspectives, preferences, and rights to informed decision-making and self-determination (Respect for autonomy).

- Demonstrates a primary commitment to the recipients of nursing and health care services in all settings and situations (Fidelity).

- Maintains therapeutic relationships and professional boundaries.

- Safeguards sensitive information within ethical, legal, and regulatory parameters (Nonmaleficence).

- Identifies ethics resources within the practice setting to assist and collaborate in addressing ethical issues.

- Integrates principles of social justice in all aspects of nursing practice (Justice).

- Refines ethical competence through continued professional education and personal self-development activities.

- Depicts one's professional nursing identity through demonstrated values and ethics, knowledge, leadership, and professional comportment.

- Engages in self-care and self-reflection practices to support and preserve personal health, well-being, and integrity.

- Contributes to the establishment and maintenance of an ethical environment that is conducive to safe, quality health care.

- Collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, enhance cultural sensitivity and congruence, and reduce health disparities.

- Represents the nursing perspective in clinic, institutional, community, or professional association ethics discussions.

Reflective Questions

- What Ethics competencies have you already demonstrated during your nursing education?

- What Ethics competencies are you most interested in mastering?

- What questions do you have about the ANA’s Ethics competencies?

The ANA's Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements is an ethical standard that guides nursing practice and ethical decision-making.[4] This section will review several basic ethical concepts related to the ANA's Ethics Standard of Professional Performance, such as values, morals, ethical theories, ethical principles, and the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses.

Values

Values are individual beliefs that motivate people to act one way or another and serve as guides for behavior considered “right” and “wrong.” People tend to adopt the values with which they were raised and believe those values are “right” because they are the values of their culture. Some personal values are considered sacred and moral imperatives based on an individual’s religious beliefs.[5] See Figure 6.1[6] for an image depicting choosing right from wrong actions.

In addition to personal values, organizations also establish values. The American Nurses Association (ANA) Professional Nursing Model states that nursing is based on values such as caring, compassion, presence, trustworthiness, diversity, acceptance, and accountability. These values emerge from nursing practice beliefs, such as the importance of relationships, service, respect, willingness to bear witness, self-determination, and the pursuit of health.[7] As a result of these traditional values and beliefs by nurses, Americans have ranked nursing as the most ethical and honest profession in Gallup polls since 1999, with the exception of 2001, when firefighters earned the honor after the attacks on September 11.[8]

The National League of Nursing (NLN) has also established four core values for nursing education: caring, integrity, diversity, and excellence[9]:

- Caring: Promoting health, healing, and hope in response to the human condition.

- Integrity: Respecting the dignity and moral wholeness of every person without conditions or limitations.

- Diversity: Affirming the uniqueness of and differences among persons, ideas, values, and ethnicities.

- Excellence: Cocreating and implementing transformative strategies with daring ingenuity.

Morals

Morals are the prevailing standards of behavior of a society that enable people to live cooperatively in groups. “Moral” refers to what societies sanction as right and acceptable. Most people tend to act morally and follow societal guidelines, and most laws are based on the morals of a society. Morality often requires that people sacrifice their own short-term interests for the benefit of society. People or entities that are indifferent to right and wrong are considered “amoral,” while those who do evil acts are considered “immoral.”[11]

Ethical Theories

There are two major types of ethical theories that guide values and moral behavior referred to as deontology and consequentialism.

Deontology is an ethical theory based on rules that distinguish right from wrong. See Figure 6.2[12] for a word cloud illustration of deontology. Deontology is based on the word deon that refers to “duty.” It is associated with philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant believed that ethical actions follow universal moral laws, such as, “Don’t lie. Don’t steal. Don’t cheat.”[13] Deontology is simple to apply because it just requires people to follow the rules and do their duty. It doesn’t require weighing the costs and benefits of a situation, thus avoiding subjectivity and uncertainty.[14],[15],[16]

The nurse-patient relationship is deontological in nature because it is based on the ethical principles of beneficence and maleficence that drive clinicians to “do good” and “avoid harm.”[17] Ethical principles will be discussed further in this chapter.

Consequentialism is an ethical theory used to determine whether or not an action is right by the consequences of the action. See Figure 6.3[19] for an illustration of weighing the consequences of an action in consequentialism. For example, most people agree that lying is wrong, but if telling a lie would help save a person’s life, consequentialism says it’s the right thing to do. One type of consequentialism is utilitarianism. Utilitarianism determines whether or not actions are right based on their consequences with the standard being achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people.[20],[21],[22] For this reason, utilitarianism tends to be society-centered. When applying utilitarian ethics to health care resources, money, time, and clinician energy are considered finite resources that should be appropriately allocated to achieve the best health care for society.[23]

Utilitarianism can be complicated when accounting for values such as justice and individual rights. For example, assume a hospital has four patients whose lives depend upon receiving four organ transplant surgeries for a heart, lung, kidney, and liver. If a healthy person without health insurance or family support experiences a life-threatening accident and is considered brain dead but is kept alive on life-sustaining equipment in the ICU, the utilitarian framework might suggest the organs be harvested to save four lives at the expense of one life.[24] This action could arguably produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people, but the deontological approach could argue this action would be unethical because it does not follow the rule of “do no harm.”

Read more about Decision making on organ donation: The dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors.

Interestingly, deontological and utilitarian approaches to ethical issues may result in the same outcome, but the rationale for the outcome or decision is different because it is focused on duty (deontologic) versus consequences (utilitarian).

Societies and cultures have unique ethical frameworks that may be based upon either deontological or consequentialist ethical theory. Culturally derived deontological rules may apply to ethical issues in health care. For example, a traditional Chinese philosophy based on Confucianism results in a culturally acceptable practice of family members (rather than the client) receiving information from health care providers about life-threatening medical conditions and making treatment decisions. As a result, cancer diagnoses and end-of-life treatment options may not be disclosed to the client in an effort to alleviate the suffering that may arise from knowledge of their diagnosis. In this manner, a client’s family and the health care provider may ethically prioritize a client’s psychological well-being over their autonomy and self-determination.[26] However, in the United States, this ethical decision may conflict with HIPAA Privacy Rules and the ethical principle of patient autonomy. As a result, a nurse providing patient care in this type of situation may experience an ethical dilemma. Ethical dilemmas are further discussed in the "Ethical Dilemmas" section of this chapter.

See Table 6.2 comparing common ethical issues in health care viewed through the lens of deontological and consequential ethical frameworks.

Table 6.2. Ethical Issues Through the Lens of Deontological or Consequential Ethical Frameworks

| Ethical Issue | Deontological View | Consequential View |

|---|---|---|

| Abortion | Abortion is unacceptable based on the rule of preserving life. | Abortion may be acceptable in cases of an unwanted pregnancy, rape, incest, or risk to the mother. |

| Bombing an area with known civilians | Killing civilians is not acceptable due to the loss of innocent lives. | The loss of innocent lives may be acceptable if the bombing stops a war that could result in significantly more deaths than the civilian casualties. |

| Stealing | Taking something that is not yours is wrong. | Taking something to redistribute resources to others in need may be acceptable. |

| Killing | It is never acceptable to take another human being’s life. | It may be acceptable to take another human life in self-defense or to prevent additional harm they could cause others. |

| Euthanasia/physician- assisted suicide | It is never acceptable to assist another human to end their life prematurely. | End-of-life care can be expensive and emotionally upsetting for family members. If a competent, capable adult wishes to end their life, medically supported options should be available. |

| Vaccines | Vaccination is a personal choice based on religious practices or other beliefs. | Recommended vaccines should be mandatory for everyone (without a medical contraindication) because of its greater good for all of society. |

Ethical Principles and Obligations

Ethical principles are used to define nurses’ moral duties and aid in ethical analysis and decision-making.[27] Although there are many ethical principles that guide nursing practice, foundational ethical principles include autonomy (self-determination), beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), justice (fairness), fidelity (keep promises), and veracity (tell the truth).

Autonomy

The ethical principle of autonomy recognizes each individual’s right to self-determination and decision-making based on their unique values, beliefs, and preferences. See Figure 6.4[28] for an illustration of autonomy. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines autonomy as the “capacity to determine one’s own actions through independent choice, including demonstration of competence.”[29] The nurse’s primary ethical obligation is client autonomy.[30] Based on autonomy, clients have the right to refuse nursing care and medical treatment. An example of autonomy in health care is advance directives. Advance directives allow clients to specify health care decisions if they become incapacitated and unable to do so.

Read more about advance directives and determining capacity and competency in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

Nurses as Advocates: Supporting Autonomy

Nurses have a responsibility to act in the interest of those under their care, referred to as advocacy. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines advocacy as “the act or process of pleading for, supporting, or recommending a cause or course of action. Advocacy may be for persons (whether an individual, group, population, or society) or for an issue, such as potable water or global health.”[31] See Figure 6.5[32] for an illustration of advocacy.

Advocacy includes providing education regarding client rights, supporting autonomy and self-determination, and advocating for client preferences to health care team members and family members. Nurses do not make decisions for clients, but instead support them in making their own informed choices. At the core of making informed decisions is knowledge. Nurses serve an integral role in patient education. Clarifying unclear information, translating medical terminology, and making referrals to other health care team members (within their scope of practice) ensures that clients have the information needed to make treatment decisions aligned with their personal values.

At times, nurses may find themselves in a position of supporting a client’s decision they do not agree with and would not make for themselves or for the people they love. However, self-determination is a human right that honors the dignity and well-being of individuals. The nursing profession, rooted in caring relationships, demands that nurses have nonjudgmental attitudes and reflect “unconditional positive regard” for every client. Nurses must suspend personal judgement and beliefs when advocating for their clients’ preferences and decision-making.[33]

Beneficence

Beneficence is defined by the ANA as “the bioethical principle of benefiting others by preventing harm, removing harmful conditions, or affirmatively acting to benefit another or others, often going beyond what is required by law.”[34] See Figure 6.6[35] for an illustration of beneficence. Put simply, beneficence is acting for the good and welfare of others, guided by compassion. An example of beneficence in daily nursing care is when a nurse sits with a dying patient and holds their hand to provide presence.

Nursing advocacy extends beyond direct patient care to advocating for beneficence in communities. Vulnerable populations such as children, older adults, cultural minorities, and the homeless often benefit from nurse advocacy in promoting health equity. Cultural humility is a humble and respectful attitude towards individuals of other cultures and an approach to learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.[36] Nurses, the largest segment of the health care community, have a powerful voice when addressing community beneficence issues, such as health disparities and social determinants of health, and can serve as the conduit for advocating for change.

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence is defined by the ANA as “the bioethical principle that specifies a duty to do no harm and balances avoidable harm with benefits of good achieved.”[37] An example of doing no harm in nursing practice is reflected by nurses checking medication rights three times before administering medications. In this manner, medication errors can be avoided, and the duty to do no harm is met. Another example of nonmaleficence is when a nurse assists a client with a serious, life-threatening condition to participate in decision-making regarding their treatment plan. By balancing the potential harm with potential benefits of various treatment options, while also considering quality of life and comfort, the client can effectively make decisions based on their values and preferences.

Justice

Justice is defined by the ANA as “a moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity and a standard linked to fairness for all in society.”[38] The principle of justice requires health care to be provided in a fair and equitable way. Nurses provide quality care for all individuals with the same level of fairness despite many characteristics, such as the individual's financial status, culture, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Nurses have a social contract to “provide compassionate care that addresses the individual’s needs for protection, advocacy, empowerment, optimization of health, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering, comfort, and well-being.”[39] An example of a nurse using the principle of justice in daily nursing practice is effective prioritization based on client needs.

Read more about prioritization models in the “Prioritization” chapter.

Other Ethical Principles

Additional ethical principles commonly applied to health care include fidelity (keeping promises) and veracity (telling the truth). An example of fidelity in daily nursing practice is when a nurse tells a client, “I will be back in an hour to check on your pain level.” This promise is kept. An example of veracity in nursing practice is when a nurse honestly explains potentially uncomfortable side effects of prescribed medications. Determining how truthfulness will benefit the client and support their autonomy is dependent on a nurse’s clinical judgment, self-reflection, knowledge of the patient and their cultural beliefs, and other factors.[40]

A principle historically associated with health care is paternalism. Paternalism is defined as the interference by the state or an individual with another person, defended by the claim that the person interfered with will be better off or protected from harm.[41] Paternalism is the basis for legislation related to drug enforcement and compulsory wearing of seatbelts.

In health care, paternalism has been used as rationale for performing treatment based on what the provider believes is in the client’s best interest. In some situations, paternalism may be appropriate for individuals who are unable to comprehend information in a way that supports their informed decision-making, but it must be used cautiously to ensure vulnerable individuals are not misused and their autonomy is not violated.

Nurses may find themselves acting paternalistically when performing nursing care to ensure client health and safety. For example, repositioning clients to prevent skin breakdown is a preventative intervention commonly declined by clients when they prefer a specific position for comfort. In this situation, the nurse should explain the benefits of the preventative intervention and the risks if the intervention is not completed. If the client continues to decline the intervention despite receiving this information, the nurse should document the education provided and the client’s decision to decline the intervention. The process of reeducating the client and reminding them of the importance of the preventative intervention should be continued at regular intervals and documented.

Care-Based Ethics

Nurses use a client-centered, care-based ethical approach to patient care that focuses on the specific circumstances of each situation. This approach aligns with nursing concepts such as caring, holism, and a nurse-client relationship rooted in dignity and respect through virtues such as kindness and compassion.[42],[43] This care-based approach to ethics uses a holistic, individualized analysis of situations rather than the prescriptive application of ethical principles to define ethical nursing practice. This care-based approach asserts that ethical issues cannot be handled deductively by applying concrete and prefabricated rules, but instead require social processes that respect the multidimensionality of problems.[44] Frameworks for resolving ethical situations are discussed in the “Ethical Dilemmas” section of this chapter.

Nursing Code of Ethics

Many professions and institutions have their own set of ethical principles, referred to as a code of ethics, designed to govern decision-making and assist individuals to distinguish right from wrong. The American Nurses Association (ANA) provides a framework for ethical nursing care and guides nurses during decision-making in its formal document titled Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements (Nursing Code of Ethics). The Nursing Code of Ethics serves the following purposes[45]:

- It is a succinct statement of the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively.

- It is the profession’s nonnegotiable ethical standard.

- It is an expression of nursing’s own understanding of its commitment to society.

The preface of the ANA’s Nursing Code of Ethics states, “Individuals who become nurses are expected to adhere to the ideals and moral norms of the profession and also to embrace them as a part of what it means to be a nurse. The ethical tradition of nursing is self-reflective, enduring, and distinctive. A code of ethics makes explicit the primary goals, values, and obligations of the profession.”[46]

The Nursing Code of Ethics contains nine provisions. Each provision contains several clarifying or “interpretive” statements. Read a summary of the nine provisions in the following box.

Nine Provisions of the ANA Nursing Code of Ethics

- Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

- Provision 2: The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

- Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

- Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.

- Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

- Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

- Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

- Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

- Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

Read the free, online full version of the ANA's Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements.

In addition to the Nursing Code of Ethics, the ANA established the Center for Ethics and Human Rights to help nurses navigate ethical conflicts and life-and-death decisions common to everyday nursing practice.

Read more about the ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights.

Specialty Organization Code of Ethics

Many specialty nursing organizations have additional codes of ethics to guide nurses practicing in settings such as the emergency department, home care, or hospice care. These documents are unique to the specialty discipline but mirror the statements from the ANA’s Nursing Code of Ethics. View ethical statements of various specialty nursing organizations using the information in the following box.

Ethical Statements of Selected Specialty Nursing Organizations

Nurses frequently find themselves involved in conflicts during patient care related to opposing values and ethical principles. These conflicts are referred to as ethical dilemmas. An ethical dilemma results from conflict of competing values and requires a decision to be made from equally desirable or undesirable options.

An ethical dilemma can involve conflicting patient’s values, nurse values, health care provider’s values, organizational values, and societal values associated with unique facts of a specific situation. For this reason, it can be challenging to arrive at a clearly superior solution for all stakeholders involved in an ethical dilemma. Nurses may also encounter moral dilemmas where the right course of action is known but the nurse is limited by forces outside their control. See Table 6.3a for an example of ethical dilemmas a nurse may experience in their nursing practice.

Table 6.3a. Examples of Ethical Issues Involving Nurses

| Workplace | Organizational Processes | Client Care |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Read more about Ethics Topics and Articles on the ANA website.

According to the American Nurses Association (ANA), a nurse’s ethical competence depends on several factors[47]:

- Continuous appraisal of personal and professional values and how they may impact interpretation of an issue and decision-making

- An awareness of ethical obligations as mandated in the Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements[48]

- Knowledge of ethical principles and their application to ethical decision-making

- Motivation and skills to implement an ethical decision

Nurses and nursing students must have moral courage to address the conflicts involved in ethical dilemmas with “the willingness to speak out and do what is right in the face of forces that would lead us to act in some other way.”[49] See Figure 6.7[50] for an illustration of nurses’ moral courage.

Nurse leaders and organizations can support moral courage by creating environments where nurses feel safe and supported to speak up.[51] Nurses may experience moral conflict when they are uncertain about what values or principles should be applied to an ethical issue that arises during patient care. Moral conflict can progress to moral distress when the nurse identifies the correct ethical action but feels constrained by competing values of an organization or other individuals. Nurses may also feel moral outrage when witnessing immoral acts or practices they feel powerless to change. For this reason, it is essential for nurses and nursing students to be aware of frameworks for solving ethical dilemmas that consider ethical theories, ethical principles, personal values, societal values, and professionally sanctioned guidelines such as the ANA Nursing Code of Ethics.

Moral injury felt by nurses and other health care workers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has gained recent public attention. Moral injury refers to the distressing psychological, behavioral, social, and sometimes spiritual aftermath of exposure to events that contradict deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.[52] Health care workers may not have the time or resources to process their feelings of moral injury caused by the pandemic, which can result in burnout. Organizations can assist employees in processing these feelings of moral injury with expanded employee assistance programs or other structured support programs.[53] Read more about self-care strategies to address feelings of burnout in the "Burnout and Self-Care" chapter.

Frameworks for Solving Ethical Dilemmas

Systematically working through an ethical dilemma is key to identifying a solution. Many frameworks exist for solving an ethical dilemma, including the nursing process, four-quadrant approach, the MORAL model, and the organization-focused PLUS Ethical Decision-Making model.[54] When nurses use a structured, systematic approach to resolving ethical dilemmas with appropriate data collection, identification and analysis of options, and inclusion of stakeholders, they have met their legal, ethical, and moral responsibilities, even if the outcome is less than ideal.

Nursing Process Model

The nursing process is a structured problem-solving approach that nurses may apply in ethical decision-making to guide data collection and analysis. See Table 6.3b for suggestions on how to use the nursing process model during an ethical dilemma.[55]

Table 6.3b. Using the Nursing Process in Ethical Situations[56]

| Nursing Process Stage | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Assessment/Data Collection |

|

| Assessment/Analysis |

|

| Diagnosis |

|

| Outcome Identification |

|

| Planning |

|

| Implementation |

|

| Evaluation |

|

Four-Quadrant Approach

The four-quadrant approach integrates ethical principles (e.g., beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice) in conjunction with health care indications, individual and family preferences, quality of life, and contextual features.[57] See Table 6.3c for sample questions used during the four-quadrant approach.

Table 6.3c. Four-Quadrant Approach[58]

| Health Care Indications

(Beneficence and Nonmaleficence)

|

Individual and Family Preferences

(Respect for Autonomy)

|

| Quality of Life

(Beneficence, Nonmaleficence, and Respect for Autonomy)

|

Contextual Features

(Justice and Fairness)

|

MORAL Model

The MORAL model is a nurse-generated, decision-making model originating from research on nursing-specific moral dilemmas involving client autonomy, quality of life, distributing resources, and maintaining professional standards. The model provides guidance for nurses to systematically analyze and address real-life ethical dilemmas. The steps in the process may be remembered by using the mnemonic MORAL. See Table 6.3d for a description of each step of the MORAL model.[59],[60]

Table 6.3d. MORAL Model

| M: Massage the dilemma | Collect data by identifying the interests and perceptions of those involved, defining the dilemma, and describing conflicts. Establish a goal. |

|---|---|

| O: Outline options | Generate several effective alternatives to reach the goal. |

| R: Review criteria and resolve | Identify moral criteria and select the course of action. |

| A: Affirm position and act | Implement action based on knowledge from the previous steps (M-O-R). |

| L: Look back | Evaluate each step and the decision made. |

PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model

The PLUS Ethical Decision-Making model was created by the Ethics and Compliance Initiative to help organizations empower employees to make ethical decisions in the workplace. This model uses four filters throughout the ethical decision-making process, referred to by the mnemonic PLUS:

- P: Policies, procedures, and guidelines of an organization

- L: Laws and regulations

- U: Universal values and principles of an organization

- S: Self-identification of what is good, right, fair, and equitable[61]

The seven steps of the PLUS Ethical Decision-Making model are as follows[62]:

- Define the problem using PLUS filters

- Seek relevant assistance, guidance, and support

- Identify available alternatives

- Evaluate the alternatives using PLUS to identify their impact

- Make the decision

- Implement the decision

- Evaluate the decision using PLUS filters

In addition to using established frameworks to resolve ethical dilemmas, nurses can also consult their organization’s ethics committee for ethical guidance in the workplace. Ethics committees are typically composed of interdisciplinary team members such as physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, administrators, social workers, and clergy to problem-solve ethical dilemmas. See Figure 6.8[63] for an illustration of an ethics committee. Hospital ethics committees were created in response to legal controversies regarding the refusal of life-sustaining treatment, such as the Karen Quinlan case.[64] Read more about the Karen Quinlan case and controversies surrounding life-sustaining treatment in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

After the passage of the Patient Self-Determination Act in 1991, all health care institutions receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding are required to form ethics committees. The Joint Commission (TJC) also requires organizations to have a formalized mechanism of dealing with ethical issues. Nurses should be aware of the process for requesting guidance and support from ethics committees at their workplace for ethical issues affecting patients or staff.[65]

Institutional Review Boards and Ethical Research

Other types of ethics committees have been formed to address the ethics of medical research on patients. Historically, there are examples of medical research causing harm to patients. For example, an infamous research study called the “Tuskegee Study” raised concern regarding ethical issues in research such as informed consent, paternalism, maleficence, truth-telling, and justice.

In 1932 the Tuskegee Study began a 40-year study looking at the long-term progression of syphilis. Over 600 Black men were told they were receiving free medical care, but researchers only treated men diagnosed with syphilis with aspirin, even after it was discovered that penicillin was a highly effective treatment for the disease. The institute allowed the study to go on, even when men developed long-stage neurological symptoms of the disease and some wives and children became infected with syphilis. In 1972 these consequences of the Tuskegee Study were leaked to the media and public outrage caused the study to shut down.[66]

Potential harm to patients participating in research studies like the Tuskegee Study was rationalized based on the utilitarian view that potential harm to individuals was outweighed by the benefit of new scientific knowledge resulting in greater good for society. As a result of public outrage over ethical concerns related to medical research, Congress recognized that an independent mechanism was needed to protect research subjects. In 1974 regulations were established requiring research with human subjects to undergo review by an institutional review board (IRB) to ensure it meets ethical criteria. An IRB is group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects.[67] The IRB review ensures the following criteria are met when research is performed:

- The benefits of the research study outweigh the potential risks.

- Individuals’ participation in the research is voluntary.

- Informed consent is obtained from research participants who have the ability to decline participation.

- Participants are aware of the potential risks of participating in the research.[68]

In addition to using established frameworks to resolve ethical dilemmas, nurses can also consult their organization’s ethics committee for ethical guidance in the workplace. Ethics committees are typically composed of interdisciplinary team members such as physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, administrators, social workers, and clergy to problem-solve ethical dilemmas. See Figure 6.8[70] for an illustration of an ethics committee. Hospital ethics committees were created in response to legal controversies regarding the refusal of life-sustaining treatment, such as the Karen Quinlan case.[71] Read more about the Karen Quinlan case and controversies surrounding life-sustaining treatment in the “Legal Implications” chapter.

After the passage of the Patient Self-Determination Act in 1991, all health care institutions receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding are required to form ethics committees. The Joint Commission (TJC) also requires organizations to have a formalized mechanism of dealing with ethical issues. Nurses should be aware of the process for requesting guidance and support from ethics committees at their workplace for ethical issues affecting patients or staff.[72]

Institutional Review Boards and Ethical Research

Other types of ethics committees have been formed to address the ethics of medical research on patients. Historically, there are examples of medical research causing harm to patients. For example, an infamous research study called the “Tuskegee Study” raised concern regarding ethical issues in research such as informed consent, paternalism, maleficence, truth-telling, and justice.

In 1932 the Tuskegee Study began a 40-year study looking at the long-term progression of syphilis. Over 600 Black men were told they were receiving free medical care, but researchers only treated men diagnosed with syphilis with aspirin, even after it was discovered that penicillin was a highly effective treatment for the disease. The institute allowed the study to go on, even when men developed long-stage neurological symptoms of the disease and some wives and children became infected with syphilis. In 1972 these consequences of the Tuskegee Study were leaked to the media and public outrage caused the study to shut down.[73]

Potential harm to patients participating in research studies like the Tuskegee Study was rationalized based on the utilitarian view that potential harm to individuals was outweighed by the benefit of new scientific knowledge resulting in greater good for society. As a result of public outrage over ethical concerns related to medical research, Congress recognized that an independent mechanism was needed to protect research subjects. In 1974 regulations were established requiring research with human subjects to undergo review by an institutional review board (IRB) to ensure it meets ethical criteria. An IRB is group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects.[74] The IRB review ensures the following criteria are met when research is performed:

- The benefits of the research study outweigh the potential risks.

- Individuals’ participation in the research is voluntary.

- Informed consent is obtained from research participants who have the ability to decline participation.

- Participants are aware of the potential risks of participating in the research.[75]

Nursing students may encounter ethical dilemmas when in clinical practice settings. Read more about research regarding ethical dilemmas experienced by students as described in the box.

Nursing Students and Ethical Dilemmas[77]

An integrative literature review performed by Albert, Younas, and Sana in 2020 identified ethical dilemmas encountered by nursing students in clinical practice settings. Three themes were identified:

1. Applying learned ethical values vs. accepting unethical practice

Students observed unethical practices of nurses and physicians, such as breach of patient privacy, confidentiality, respect, rights, duty to provide information, and physical and psychological mistreatment, that opposed the ethical values learned in nursing school. Students experienced ethical conflict due to their sense of powerlessness, low status as students, dependence on staff nurses for learning experiences, and fear of offending health care providers.

2. Desiring to provide ethical care but lacking autonomous decision-making

Students reported a lack of moral courage in questioning unethical practices. The hierarchy of health care environments left students feeling disregarded, humiliated, and intimidated by professional nurses and managers. Students also reported a sense of loss of identity in feeling forced to conform their personal identity to that of the clinical environment.

3. Whistleblowing vs. silence regarding patient care and neglect

Students observed nurses performing unethical nursing practices, such as ignoring client needs, disregarding pain, being verbally abusive, talking inappropriately about clients, and not providing a safe or competent level of care. Most students reported remaining silent regarding these observations due to a lack of confidence, feeling it was not their place to report, or the fear of negative consequences. Organizational power dynamics influenced student confidence in reporting unethical practices to faculty or nurse managers.

The researchers concluded that nursing students feel moral distress when experiencing these kinds of conflicts:

- Providing ethical care as learned in their program of study or accepting unethical practices

- Staying silent about patient care neglect or confronting it and reporting it

- Providing quality, ethical care or adapting to organizational culture due to lack of autonomous decision-making

These ethical conflicts can be detrimental to students' professional learning and mental health. Researchers recommended that nurse educators should develop educational programs to support students as they develop ethical competence and moral courage to confront ethical dilemmas.[78]

Read more about ethics education in nursing in the ANA’s Online Journal of Issues in Nursing article.

COVID-19 and the Nursing Profession

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of nurses’ foundational knowledge of ethical principles and the Nursing Code of Ethics. Scarce resources in an overwhelmed health care system resulted in ethical dilemmas and moral injury for nurses involved in balancing conflicting values, rights, and ethical principles. Many nurses were forced to weigh their duty to patients and society against their duty to themselves and their families. Challenging ethical issues occurred related to the ethical principle of justice, such as fair distribution of limited ICU beds and ventilators, and ethical dilemmas related to end-of-life issues such as withdrawing or withholding life-prolonging treatment became common.[79]

Regardless of their practice setting or personal contact with clients affected by COVID-19, nurses have been forced to reflect on the essence of ethical professional nursing practice through the lens of personal values and morals. Nursing students must be knowledgeable about ethical theories, ethical principles, and strategies for resolving ethical dilemmas as they enter the nursing profession that will continue to experience long-term consequences as a result of COVID-19.[80]

A True Story of a New Nurse’s Introduction to Ethical Dilemmas

A new nurse graduate meets Mary, a 70-year-old woman who was living alone at home with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or also referred to as “Lou Gehrig’s disease”). Mary’s husband died many years ago and they did not have children. She had a small support system, including relatives who lived out of state and friends with whom she had lost touch since her diagnosis. Mary was fiercely independent and maintained her nutrition and hydration through a gastrostomy tube to avoid aspiration.

As Mary’s disease progressed, the new nurse discussed several safety issues related to Mary living alone. As the new nurse shared several alternative options related to skilled nursing care with Mary, Mary shared her own plan. Mary said her plan included a combination of opioids, benzodiazepines, and a plastic bag to suffocate herself and be found by a nurse during a scheduled visit. In addition to safety issues and possible suicide ideation, the new nurse recognized she was in the midst of an ethical dilemma in terms of the treatment plan, her values and what she felt was best for Mary, and Mary’s preferences.

Applying the MORAL Ethical Decision-Making Model to Mary’s Case

| Massage the Dilemma | Data: Mary lives alone and does not want to go to a nursing home. She lacks social support. She has a progressive and incurable disease that affects her ability to swallow, talk, walk, and eventually breathe. She has made statements to staff indicating she prefers to die rather than leave her home to receive total care in a long-term care setting.

Ethical Conflicts: According to the deontological theory, suicide is always wrong. According to the consequentialism ethical theory, an action's morality depends on the consequences of that action. Mary has a progressive, incurable illness that requires total care that will force her to leave the home. She wishes to stay in her home until she dies. Ethical Goals: To honor Mary’s dignity and respect her autonomy in making treatment decisions. For Mary to experience a “good” death as she defines it, and neither hasten nor prolong her dying process through illegal or amoral interventions. |

|---|---|

| Outline the Options |

|

| Review Criteria and Resolve | Mary was assessed to be rational and capable of decision-making by a psychiatrist. Mary defined a “good” death as one occurring in her home and not in a hospital or long-term care setting. Mary did not want her life to be prolonged through the use of technology such as a ventilator.

Resolution: Mary elected to discontinue tube feeding and limit hydration to only that necessary for medication to provide comfort care and symptom management. |

| Affirm Position and Act | Although some health care members did not personally believe in discontinuing food and fluids through the g-tube based on their interpretation of the deontological ethical theory, Mary’s decision was acceptable both legally and ethically, based on the consequentialism ethical theory that the decision best supported Mary’s goals and respected her autonomy.

Daily visits were scheduled with hospice staff, including the nurse, nursing assistant, social worker, chaplain, and volunteers. Hired caregivers supplemented visits and in the last couple of days were scheduled around the clock. Mary died comfortably in her bed seven days after implementation of the agreed-upon plan. |

| Look Back | The health care team evaluated what happened during Mary’s situation and what could be learned from this ethical dilemma and applied to future patient-care scenarios. |

The third IPEC competency focuses on interprofessional communication and states, “Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease.”[81] See Figure 7.1[82] for an image of interprofessional communication supporting a team approach. This competency also aligns with The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal for improving staff communication.[83] See the following box for the components associated with the Interprofessional Communication competency.

Components of IPEC’s Interprofessional Communication Competency[84]

- Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

- Communicate information with patients, families, community members, and health team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible.

- Express one’s knowledge and opinions to team members involved in patient care and population health improvement with confidence, clarity, and respect, working to ensure common understanding of information, treatment, care decisions, and population health programs and policies.

- Listen actively and encourage ideas and opinions of other team members.

- Give timely, sensitive, constructive feedback to others about their performance on the team, responding respectfully as a team member to feedback from others.

- Use respectful language appropriate for a given difficult situation, crucial conversation, or conflict.

- Recognize how one’s uniqueness (experience level, expertise, culture, power, and hierarchy within the health care team) contributes to effective communication, conflict resolution, and positive interprofessional working relationships.

- Communicate the importance of teamwork in patient-centered care and population health programs and policies.

Transmission of information among members of the health care team and facilities is ongoing and critical to quality care. However, information that is delayed, inefficient, or inadequate creates barriers for providing quality of care. Communication barriers continue to exist in health care environments due to interprofessional team members’ lack of experience when interacting with other disciplines. For instance, many novice nurses enter the workforce without experiencing communication with other members of the health care team (e.g., providers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, surgical staff, dieticians, physical therapists, etc.). Additionally, health care professionals tend to develop a professional identity based on their educational program with a distinction made between groups. This distinction can cause tension between professional groups due to diverse training and perspectives on providing quality patient care. In addition, a health care organization’s environment may not be conducive to effectively sharing information with multiple staff members across multiple units.

In addition to potential educational, psychological, and organizational barriers to sharing information, there can also be general barriers that impact interprofessional communication and collaboration. See the following box for a list of these general barriers.[85]

General Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[86]

- Personal values and expectations

- Personality differences

- Organizational hierarchy

- Lack of cultural humility

- Generational differences

- Historical interprofessional and intraprofessional rivalries

- Differences in language and medical jargon

- Differences in schedules and professional routines

- Varying levels of preparation, qualifications, and status

- Differences in requirements, regulations, and norms of professional education

- Fears of diluted professional identity

- Differences in accountability and reimbursement models

- Diverse clinical responsibilities

- Increased complexity of patient care

- Emphasis on rapid decision-making

There are several national initiatives that have been developed to overcome barriers to communication among interprofessional team members. These initiatives are summarized in Table 7.5a.[87]

Table 7.5a. Initiatives to Overcome Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[88]

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Teach structured interprofessional communication strategies | Structured communication strategies, such as ISBARR, handoff reports, I-PASS reports, and closed-loop communication should be taught to all health professionals. |

| Train interprofessional teams together | Teams that work together should train together. |

| Train teams using simulation | Simulation creates a safe environment to practice communication strategies and increase interdisciplinary understanding. |

| Define cohesive interprofessional teams | Interprofessional health care teams should be defined within organizations as a cohesive whole with common goals and not just a collection of disciplines. |

| Create democratic teams | All members of the health care team should feel valued. Creating democratic teams (instead of establishing hierarchies) encourages open team communication. |

| Support teamwork with protocols and procedures | Protocols and procedures encouraging information sharing across the whole team include checklists, briefings, huddles, and debriefing. Technology and informatics should also be used to promote information sharing among team members. |

| Develop an organizational culture supporting health care teams | Agency leaders must establish a safety culture and emphasize the importance of effective interprofessional collaboration for achieving good patient outcomes. |

Communication Strategies

Several communication strategies have been implemented nationally to ensure information is exchanged among health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to promote safe patient care. Examples of these initiatives are ISBARR, handoff reports, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS. Documentation that promotes sharing information interprofessionally to promote continuity of care is also essential. These strategies are discussed in the following subsections.

ISBARR

A common format used by health care team members to exchange client information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[89],[90]

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the client’s name and location, the reason you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the client.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the client such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your evaluation of the current client situation.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the client, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the client’s chart.

Nursing Considerations

Before using ISBARR to call a provider regarding a changing client condition or concern, it is important for nurses to prepare and gather appropriate information. See the following box for considerations when calling the provider.

Communication Guidelines for Nurses[91]

- Have I assessed this client before I call?

- Have I reviewed the current orders?

- Are there related standing orders or protocols?

- Have I read the most recent provider and nursing progress notes?

- Have I discussed concerns with my charge nurse, if necessary?

- When ready to call, have the following information on hand:

- Admitting diagnosis and date of admission

- Code status

- Allergies

- Most recent vital signs

- Most recent lab results

- Current meds and IV fluids

- If receiving oxygen therapy, current device and L/min

- Before calling, reflect on what you expect to happen as a result of this call and if you have any recommendations or specific requests.

- Repeat back any new orders to confirm them.

- Immediately after the call, document with whom you spoke, the exact time of the call, and a summary of the information shared and received.

Read an example of an ISBARR report in the following box.

Sample ISBARR Report From a Nurse to a Health Care Provider

I: “Hello Dr. Smith, this is Jane Smith, RN from the Med-Surg unit.”

S: “I am calling to tell you about Ms. White in Room 210, who is experiencing an increase in pain, as well as redness at her incision site. Her recent vital signs were BP 160/95, heart rate 90, respiratory rate 22, O2 sat 96% on room air, and temperature 38 degrees Celsius. She is stable but her pain is worsening.”

B: “Ms. White is a 65-year-old female, admitted yesterday post hip surgical replacement. She has been rating her pain at 3 or 4 out of 10 since surgery with her scheduled medication, but now she is rating the pain as a 7, with no relief from her scheduled medication of Vicodin 5/325 mg administered an hour ago. She is scheduled for physical therapy later this morning and is stating she won’t be able to participate because of the pain this morning.”

A: “I just assessed the surgical site, and her dressing was clean, dry, and intact, but there is 4 cm redness surrounding the incision, and it is warm and tender to the touch. There is moderate serosanguinous drainage. Her lungs are clear, and her heart rate is regular. She has no allergies. I think she has developed a wound infection.”

R: “I am calling to request an order for a CBC and increased dose of pain medication.”

R: “I am repeating back the order to confirm that you are ordering a STAT CBC and an increase of her Vicodin to 10/325 mg.”

View or print an ISBARR reference card.

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as “a transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care.”[92] In 2017 The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication that has resulted in patient harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors.[93]

The Joint Commission encourages the standardization of critical content to be communicated by interprofessional team members during a handoff report both verbally (preferably face to face) and in written form. Critical content to communicate to the receiver in a handoff report includes the following components[94]:

- Sender contact information

- Illness assessment, including severity

- Patient summary, including events leading up to illness or admission, hospital course, ongoing assessment, and plan of care

- To-do action list

- Contingency plans

- Allergy list

- Code status

- Medication list

- Recent laboratory tests

- Recent vital signs

Several strategies for improving handoff communication have been implemented nationally, such as the Bedside Handoff Report Checklist, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS.

Bedside Handoff Report Checklist

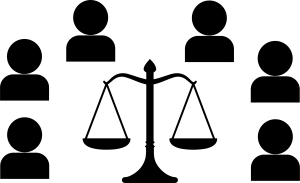

See Figure 7.2[95] for an example of a Bedside Handoff Report Checklist to improve nursing handoff reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[96] Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts.

Print a copy of the AHRQ Bedside Shift Report Checklist.[97]

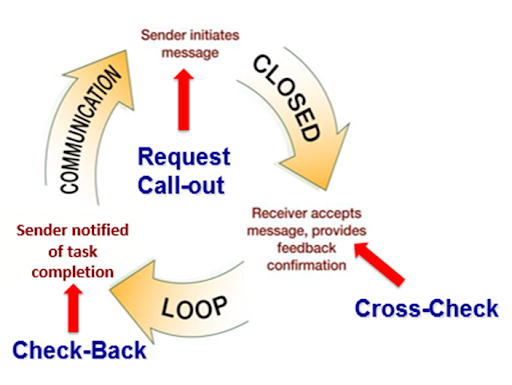

Closed-Loop Communication

The closed-loop communication strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed. Closed-loop communication is especially important during emergency situations when verbal orders are being provided as treatments are immediately implemented. See Figure 7.3[98] for an illustration of closed-loop communication.

- The sender initiates the message.

- The receiver accepts the message and repeats back the message to confirm it (i.e., “Cross-Check”).

- The sender confirms the message.

- The receiver notified the sender the task was completed (i.e., “Check-Back”).

See an example of closed-loop communication during an emergent situation in the following box.

Closed-Loop Communication Example

Doctor: "Administer 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT."

Nurse: "Give 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT?"

Doctor: "That's correct."

Nurse: "Benadryl 25 mg IV push given at 1125."

I-PASS

I-PASS is a mnemonic used to provide structured communication among interprofessional team members. I-PASS stands for the following components[99]:

I: Illness severity

P: Patient summary

A: Action list

S: Situation awareness and contingency plans

S: Synthesis by receiver (i.e., closed-loop communication)

See a sample I-PASS Handoff in Table 7.5b.[100]

Table 7.5b. Sample I-PASS Verbal Handoff[101]

| I | Illness Severity | This is our sickest patient on the unit, and he's a full code. |

|---|---|---|

| P | Patient Summary | AJ is a 4-year-old boy admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to left lower lobe pneumonia. He presented with cough and high fevers for two days before admission, and on the day of admission to the emergency department, he had worsening respiratory distress. In the emergency department, he was found to have a sodium level of 130 mg/dL likely due to volume depletion. He received a fluid bolus, and oxygen administration was started at 2.5 L/min per nasal cannula. He is on ceftriaxone. |

| A | Action List | Assess him at midnight to ensure his vital signs are stable. Check to determine if his blood culture is positive tonight. |

| S | Situations Awareness & Contingency Planning | If his respiratory distress worsens, get another chest radiograph to determine if he is developing an effusion. |

| S | Synthesis by Receiver | Ok, so AJ is a 4-year-old admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to a left lower lobe pneumonia receiving ceftriaxone, oxygen, and fluids. I will assess him at midnight to ensure he is stable and check on his blood culture. If his respiratory status worsens, I will repeat a radiograph to look for an effusion. |

Listening Skills

Effective team communication includes both the delivery and receipt of the message. Listening skills are a fundamental element of the communication loop. For nursing staff, this involves listening to clients, families, and coworkers. Active listening involves not just hearing the individual words that someone states, but also understanding the emotions and concerns behind the words. Employing active listening reflects an empathetic approach and can improve client outcomes and foster teamwork.