8.4 Health Care Reimbursement Models

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

As discussed in the previous section, hospitals and health care providers are paid for services provided to individuals by government insurance programs (such as Medicare and Medicaid), private insurance companies, or people using their out-of-pocket funds. Traditionally, health care institutions were paid based on a “fee-for-service” model. For example, if a patient was admitted to a hospital with pneumonia, the hospital billed that individual’s insurance program for the cost of care.

However, as part of a recent national strategy to reduce health care costs, insurance providers have transitioned to “Pay for Performance” reimbursement models that are based on overall agency performance and patient outcomes.

Pay for Performance

Pay for Performance, also known as value-based payment, refers to reimbursement models that attach financial incentives to the performance of health care agencies and providers. Pay for Performance models tie higher reimbursement payments to positive patient outcomes, best practices, and patient satisfaction, thus aligning payment with value and quality.[1] Nurses support higher reimbursement levels to their employers based on their documentation related to nursing care plans and achievement of expected patient outcomes.

There are two Pay for Performance models. The first model rewards hospitals and providers with higher reimbursement payments based on how well they perform on process, quality, and efficiency measures. The second model penalizes hospitals and providers for subpar performance by reducing reimbursement amounts.[2] For example, Medicare no longer reimburses hospitals to treat patients who acquire certain preventable conditions during their hospital stay, such as pressure injuries or urinary tract infections associated with use of catheters.[3]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), spurred by the Affordable Care Act, has led the way in value-based payment with a variety of payment models. CMS is the largest health care funder in the United States with almost 40% of overall health care spending for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS developed three Pay for Performance models that impact hospitals’ reimbursement by Medicare. These models are called the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. Private insurers are also committed to performance-based payment models. In 2017 Forbes reported that almost 50% of insurers’ reimbursements were in the form of value-based care models.[4]

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program

The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (VBP) was designed to improve health care quality and patient experience by using financial incentives that encourage hospitals to follow established best clinical practices and improve patient satisfaction scores via patient satisfaction surveys. Reimbursement is based on hospital performance on measures divided into four quality domains: safety, clinical care, efficiency and cost reduction, and patient and caregiver-centered experience.[5] The VBP program rewards hospitals based on the quality of care provided to Medicare patients and not just the quantity of services that are provided. Hospitals may have their Medicaid payments reduced by up to 2% if not meeting the quality metrics.

Read more about patient satisfaction surveys.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) penalizes hospitals with higher rates of patient readmissions compared to other hospitals. HRRP was established by the Affordable Care Act and applies to patients with specific conditions, such as heart attacks, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hip or knee replacements, and coronary bypass surgery. Hospitals with poor performance receive a 3% reduction of their Medicare payments. However, it was discovered that hospitals with higher proportions of low-income patients were penalized the most, so Congress passed legislation in 2019 that divided hospitals into groups for comparison based on the socioeconomic status of their patient populations.[6]

Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program

The Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP) was established by the Affordable Care Act. This Pay for Performance model reduces payments to hospitals based on poor performance regarding patient safety and hospital-acquired conditions, such as surgical site infections, hip fractures resulting from falls, and pressure injuries. This model has saved Medicare approximately $350 million per year.[7]

The HACRP model measures the incidence of hospital-acquired conditions, including central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), surgical site infections (SSI), Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA), and Clostridium Difficile (C. diff).[8] As a result, nurses have seen changes in daily practices based on evidence-based practices related to these conditions. For example, stringent documentation is now required for clients with Foley catheters that indicates continued need and associated infection control measures.

Other CMS Pay for Performance Models

CMS has created other value-based payment programs for agencies other than hospitals, including the End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Quality Initiative Program, the Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Program (SNFVBP), the Home Health Value-Based Program (HHVBP), and the Value Modifier (VM) Program. The VM program is aimed at Medicare Part B providers who receive high, average, or low ratings based on quality and cost measurements as compared to peer agencies.

Impacts of Value-Based Payment

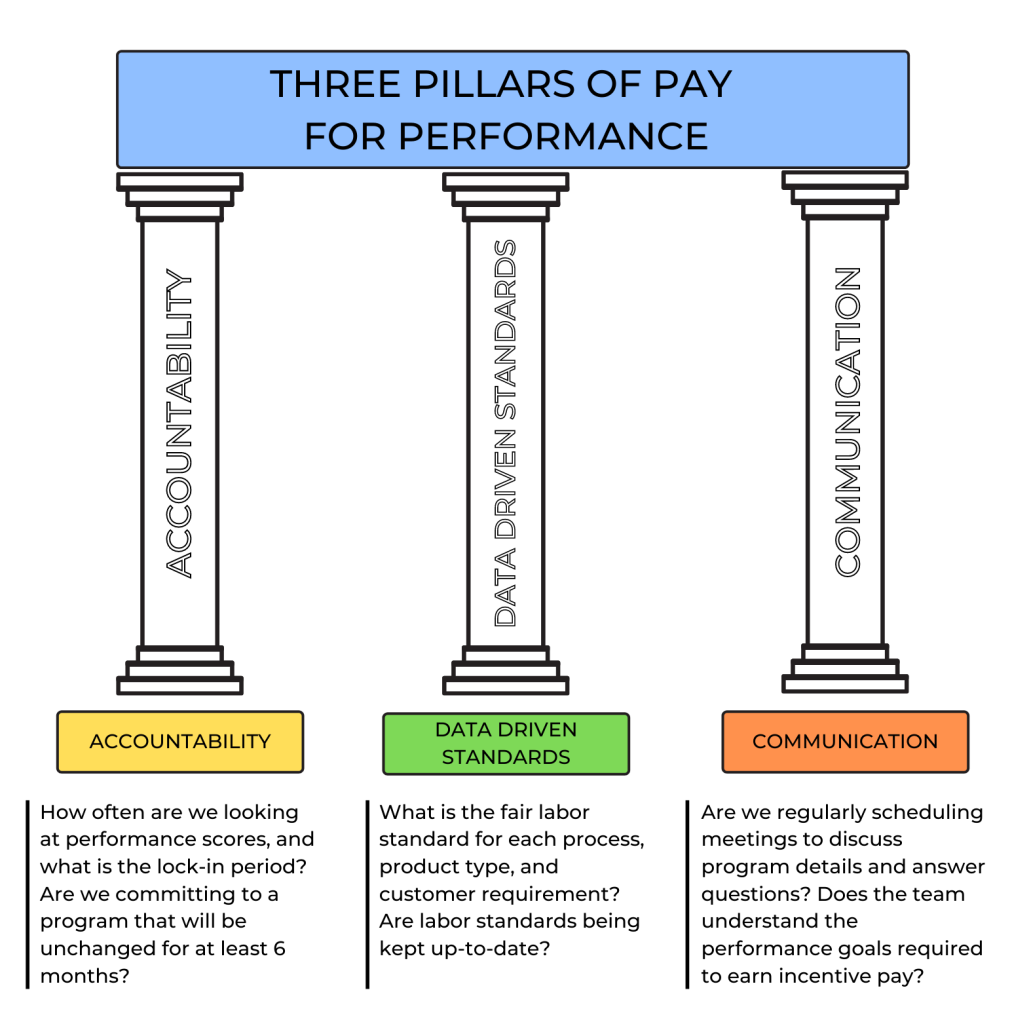

Pay for Performance (i.e., value-based payment) stresses quality over quantity of care and allows health care payers to use reimbursement to encourage best clinical practices and promote positive health outcomes. It focuses on transparency by using metrics that are publicly reported, thus incentivizing organizations to protect and strengthen their reputations. In this manner, Pay for Performance models encourage accountability and consumer-informed choice.[9] See Figure 8.8[10] for an illustration of Pay for Performance.

Pay for Performance models have reduced health care costs and decreased the incidence of poor patient outcomes. For example, 30-day hospital readmission rates have been falling since 2012, indicating HRRP and HACRP are having an impact.[11]

However, there are also disadvantages to value-based payment. As previously discussed, initial research indicated hospitals with higher proportions of low-income patients were being penalized the most, resulting in additional legislation to compare hospital performance in groups based on their clients’ socioeconomic status. Nursing leaders continue to emphasize strategies that further address social determinants of health and promote health equity.[12] Read more about equity and social determinants of health in the following subsection.

Nursing Considerations

Nurses have a direct impact on activities related to quality care and reimbursement rates received by their employer. There are several categories of actions nurses can take to improve quality patient care, reduce costs, and improve reimbursement. By incorporating these actions into their daily care, nurses can help ensure the funding they need to provide quality patient care is received by their employer and resources are allocated appropriately to their patients.

The following categories of actions to improve quality of care are based on the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System and Crossing the Quality Chasm[13]:

- Effectiveness and Efficiency: Nurses support their institution’s effectiveness and efficiency with individualized nursing care planning, good documentation, and care coordination. With accurate and timely documentation and care coordination, there is reduced care duplication and waste. Coordinating care also helps to reduce the risk of hospital readmissions.

- Timeliness: Nurses positively impact timeliness by prioritizing and delegating care. This helps reduce patient wait times and delays in care.

Read more about these concepts in the “Delegation and Supervision” and “Prioritization” chapters in this book.

- Safety: Nurses pay attention to their patients’ changing conditions and effectively communicate these changes with appropriate health care team members. They take any concerns about client care up the chain of command until their concerns are resolved.

- Patient-Centered Care: Nurses support this quality measure by ensuring nursing care plans are individualized for each patient. Effective care plans can improve patient compliance, resulting in improved patient outcomes.

- Evidence-Based Practice: Nurses provide care based on evidence-based practice. Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is defined by the American Nurses Association as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and patient, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[14] EBP is a component of Scholarly Inquiry, one of the ANA’s Standards of Professional Practice. Nurses’ implementation of EBP ensures proper resources are allocated to the appropriate clients. EBP promotes safe, efficient, and effective health care.[15],[16]

Read more information about EBP in the “Quality and Evidence-Based Practice” chapter of this book.

- Equity: Health care institutions care for all members of their community regardless of client demographics and their associated social determinants of health (SDOH). SDOH are conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes. Health disparities in communities with poor SDOH have been consistently documented in reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[17]

Nurses address negative determinants of health by advocating for interventions that reduce health disparities and promote the delivery of equitable health care resources. The term health disparities describes the differences in health outcomes that result from SDOH. Advocating for resources that enhance quality of life can significantly influence a community’s health outcomes. Examples of resources that promote health include safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free of life-threatening toxins.

A related term is health care disparity that refers to differences in access to health care and insurance coverage. Health disparities and health care disparities can lead to decreased quality of life, increased personal costs, and lower life expectancy. More broadly, these disparities also translate to greater societal costs, such as the financial burden of uncontrolled chronic illnesses. An example of nurses addressing health care disparities are nurse practitioners providing health care according to their scope of practice to underserved populations in rural communities.

The ANA promotes nurse advocacy in workplaces and local communities. There are many ways nurses can promote health and wellness within their communities through a variety of advocacy programs at the federal, state, and community level.[18] Read more about advocacy and reducing health disparities in the following boxes.

Read more about ANA Policy and Advocacy.

Read more information in the “Advocacy” chapter of this book.

Read more about addressing health disparities in the “Diverse Patients” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Media Attributions

- Pillars of Pay Performance

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- James, J. (2012, October 11). Pay-for-performance. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20121011.90233/full/ ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- “Pillars of Pay Performance.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Pay for Performance. (2018). NEJM catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0245 ↵

- Avalere Health LLC. (2015). Optimal nurse staffing to improve quality of care and patient outcomes: Executive summary [White paper]. https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/4850206/ANA/NurseStaffingWhitePaper_Final.pdf?__hstc=53609399.b25284991e95c5d4f1c55a49e826489f.1612299494138.1628353446072.1628356381954.16&__hssc=53609399.3.1628356381954&__hsfp=1865500357 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Stevens, K. (2013, May 31). The impact of evidence-based practice in nursing and the next big ideas. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 18(2). https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-18-2013/No2-May-2013/Impact-of-Evidence-Based-Practice.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, May 6). Social determinants of health: Know what affects health. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm ↵

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2021, June). 2019 national healthcare quality and disparities report. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr19/index.html ↵

Legal Considerations

As discussed earlier in this chapter, nurses can be reprimanded or have their licenses revoked for not appropriately following the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are practicing. Nurses can also be held legally liable for negligence, malpractice, or breach of client confidentiality when providing client care.

Negligence and Malpractice

Negligence is a general term that denotes conduct lacking in due care, carelessness, and a deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would use in a particular set of circumstances.[1] Malpractice is a more specific term that looks at a standard of care, as well as the professional status of the caregiver. [2]

To prove negligence or malpractice, the following elements must be established in a court of law[3]:

- Duty owed the client

- Breach of duty owed the client

- Foreseeability

- Causation

- Injury

- Damages

To avoid being sued for negligence or malpractice, it is essential for nurses and nursing students to follow the scope and standards of practice care set forth by their state’s Nurse Practice Act; the American Nurses Association; and employer policies, procedures, and protocols to avoid the risk of losing their nursing license. Examples of a nurse's breach of duty that can be viewed as negligence includes the following:[4]

- Failure to Assess: Nurses should assess for all potential nursing problems/diagnoses, not just those directly affected by the medical disease. For example, all clients should be assessed for fall risk and appropriate fall precautions implemented.

- Insufficient monitoring: Some conditions require frequent monitoring by the nurse, such as risk for falls, suicide risk, confusion, and self-injury.

- Failure to Communicate:

- Lack of documentation: A basic rule of thumb in a court of law is that if an assessment or action was not documented, it is considered not done. Nurses must document all assessments and interventions, in addition to the specific type of client documentation called a nursing care plan.

- Lack of provider notification: Changes in client condition should be urgently communicated to the health care provider based on client status. Documentation of provider notification should include the date, time, and person notified and follow-up actions taken by the nurse.

- Failure to Follow Protocols: Agencies and states have rules for reporting certain behaviors or concerns. For example, a nurse is considered a mandatory reporter by law and required to report suspicion of abuse or neglect of a child based on data gathered during an assessment.

Patient Self Determination Act

The Patient Self Determination Act (PSDA) of 1990 is an amendment made to the Social Security Act that requires health care facilities to inform clients of their right to be involved in their medical care decisions. This law specifically applies to facilities accepting Medicare or Medicaid funding but is considered a right of all clients regardless of their method of reimbursement.

Under the PSDA, clients must also be asked about their advance directives and care wishes. Clients must be provided with teaching about advance directives, appointment of an agent or surrogate in the event they become incapacitated, and their right to self-determination. Conversations about these topics and clients wishes must be documented in the medical record. It is considered an ethical duty of nurses and other health care professionals to ensure clients are aware and understand these healthcare-associated rights.[5]

Informed Consent

Informed consent is written consent voluntarily signed by a client who is competent and understands the terms of the consent without any form of coercion. In the event the client is a minor or deemed incompetent to make their own decisions, a parent or legal guardian signs the informed consent.[6]

Informed consent is crucial for upholding the client's right for self-determination. Informed consent provides documentation signed by the client of their understanding of health care being provided; its benefits, risks, potential complications; reasonable alternatives to treatment; and the right to withdraw consent. It is the health care provider's responsibility to fully discuss the treatment, procedure, or other health care action being proposed that requires consent. The nurse often signs as a witness to the client's signature on the form, affirming that person signed the form. However, it is not the nurse's responsibility or role to provide information. If the client (or their parent/legal guardian) expresses questions, concerns, or lack of understanding, the nurse has an ethical responsibility to notify the provider and advocate for further discussion before signing the form.[7]

In emergency situations where the delay to obtain consent would cause undue harm to the client, verbal or telephone consent may be temporarily obtained that is valid for no more than ten days. Verbal consent and the reason for verbal consent must be documented in the medical record by the provider.[8]

See the following box for examples of situations requiring informed consent in the state of Wisconsin according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Examples of Situations Requiring Informed Consent[9]

- Receipt of medications and/or treatment, including psychotropic medications (unless court-ordered)

- Undergoing customary treatment techniques and procedures

- Participation in experimental research

- Undergoing psychosurgery or other psychological treatment procedures

- Release of treatment records

- Videorecording

- Performance of labor beneficial to the facility

Confidentiality

In addition to negligence and malpractice, confidentiality is a major legal consideration for nurses and nursing students. Patient confidentiality is the right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information, referred to as their protected health information (PHI), protected and known only by those health care team members directly providing care to them. This right is protected by federal regulations called the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA was enacted in 1996 and was prompted by the need to ensure privacy and protection of personal health records and data in an environment of electronic medical records and third-party insurance payers. There are two main sections of HIPAA law, the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule. The Privacy Rule addresses the use and disclosure of individuals' health information. The Security Rule sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information. HIPAA regulations extend beyond medical records and apply to client information shared with others. Therefore, all types of client information should only be shared with health care team members who are actively providing care to them.

How do HIPAA regulations affect you as a student nurse? You are required to adhere to HIPAA guidelines from the moment you begin to provide client care. Nursing students may be disciplined or expelled by their nursing program for violating HIPAA. Nurses who violate HIPAA rules may be fired from their jobs or face lawsuits. See the following box for common types of HIPAA violations and ways to avoid them.

Common HIPAA Violations and Ways to Avoid Them[10]

- Gossiping in the hallways or otherwise talking about clients where other people can hear you. It is understandable that you will be excited about what is happening when you begin working with clients and your desire to discuss interesting things that occur. As a student, you will be able to discuss client care in a confidential manner behind closed doors with your instructor. However, as a health care professional, do not talk about clients in the hallways, elevator, breakroom, or with others who are not directly involved with that client’s care because it is too easy for others to overhear what you are saying.

- Mishandling medical records or leaving medical records unsecured. You can breach HIPAA rules by leaving your computer unlocked for anyone to access or by leaving written client charts in unsecured locations. You should never share your password with anyone else. Make sure that computers are always locked with a password when you step away from them and paper charts are closed and secured in an area where unauthorized people don’t have easy access to them. NEVER take records from a facility or include a client's name on paperwork that leaves the facility.

- Illegally or unauthorized accessing of client files. If someone you know, like a neighbor, coworker, or family member is admitted to the unit you are working on, do not access their medical record unless you are directly caring for them. Facilities have the capability of tracing everything you access within the electronic medical record and holding you accountable. This rule holds true for employees who previously cared for a client as a student; once your shift is over as a student, you should no longer access that client’s medical records.

- Sharing information with unauthorized people. Anytime you share medical information with anyone but the client themselves, you must have written permission to do so. For instance, if a husband comes to you and wants to know his spouse’s lab results, you must have permission from his spouse before you can share that information with him. Just confirming or denying that a client has been admitted to a unit or agency can be considered a breach of confidentiality. Furthermore, voicemails should not be left regarding protected client information.

- Information can generally be shared with the parents of children until they turn 18, although there are exceptions to this rule if the minor child seeks birth control, an abortion, or becomes pregnant. After a child turns 18, information can no longer be shared with the parent unless written permission is provided, even if the minor is living at home and/or the parents are paying for their insurance or health care. As a general rule, any time you are asked for client information, check first to see if the client has granted permission.

- Texting or e-mailing regarding client information on an unencrypted device. Only use properly encrypted devices that have been approved by your health care facility for e-mailing or faxing protected client information. Also, ensure that the information is being sent to the correct person, address, or phone number.

- Sharing information on social media. Never post anything on social media that has anything to do with your clients, the facility where you are working or have clinical, or even how your day went at the agency. Nurses and other professionals have been fired for violating HIPAA rules on social media.[11],[12],[13]

Social Media Guidelines

Nursing students, nurses, and other health care team members must use extreme caution when posting to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and other social media sites. Information related to clients, client care, and/or health care agencies should never be posted on social media; health care team members who violate this guideline can lose their jobs and may face legal action and students can be disciplined or expelled from their nursing program. Be aware that even if you think you are posting in a private group, the information can become public.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) has established the following principles for nurses using social media:[14]

- Nurses must not transmit or place online individually identifiable client information.

- Nurses must observe ethically prescribed professional client-nurse boundaries.

- Nurses should understand that clients, colleagues, organizations, and employers may view postings.

- Nurses should take advantage of privacy settings and seek to separate personal and professional information online.

- Nurses should bring content that could harm a client’s privacy, rights, or welfare to the attention of appropriate authorities.

- Nurses should participate in developing organizational policies governing online conduct.

In addition to these principles, the ANA has also provided these tips for nurses and nursing students using social media:[15]

- Remember that standards of professionalism are the same online as in any other circumstance.

- Do not share or post information or photos gained through the nurse-client relationship.

- Maintain professional boundaries in the use of electronic media. Online contact with clients blurs this boundary.

- Do not make disparaging remarks about clients, employers, or coworkers, even if they are not identified.

- Do not take photos or videos of clients on personal devices, including cell phones.

- Promptly report a breach of confidentiality or privacy.

Read more about the ANA's Social Media Principles.

Code of Ethics

In addition to legal considerations, there are also several ethical guidelines for nursing care.

There is a difference between morality, ethical principles, and a code of ethics. Morality refers to “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals within communities and societies.”[16] An ethical principle is a general guide, basic truth, or assumption that can be used with clinical judgment to determine a course of action. Four common ethical principles are beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), autonomy (control by the individual), and justice (fairness). A code of ethics is set for a profession and makes their primary obligations, values, and ideals explicit.

The American Nursing Association (ANA) guides nursing practice with the Code of Ethics for Nurses.[17] This code provides a framework for ethical nursing care and a guide for decision-making. The Code of Ethics for Nurses serves the following purposes:

- It is a succinct statement of the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively.

- It is the profession’s nonnegotiable ethical standard.

- It is an expression of nursing’s own understanding of its commitment to society.[18]

The ANA Code of Ethics contains nine provisions. See a brief description of each provision in the following box.

Provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics[19]

The nine provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics are briefly described below. The full code is available to read for free at Nursingworld.org.

Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

Provision 2: The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.

Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

The ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights

In addition to publishing the Code of Ethics, the ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights was established to help nurses navigate ethical and value conflicts and life-and-death decisions, many of which are common to everyday practice.

Check your knowledge with the following questions:

Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN): An RN who has a graduate degree and advanced knowledge. There are four categories of APRNs: certified nurse-midwife (CNM), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), certified nurse practitioner (CNP), or certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). These nurses can diagnose illnesses and prescribe treatments and medications.[20] (Chapter 1.4)

ANA Standards of Professional Nursing Practice: Authoritative statements of the duties that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, or specialty, are expected to perform competently. The Standards of Professional Nursing Practice describe a competent level of nursing practice as demonstrated by the critical thinking model known as the nursing process. The nursing process includes the components of assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation.[21] (Chapter 1.3)

ANA Standards of Professional Performance: Standards that describe a competent level of behavior in the professional role of the nurse, including activities related to ethics, advocacy, respectful and equitable practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, scholarly inquiry, quality of practice, professional practice evaluation, resource stewardship, and environmental health.[22] (Chapter 1.3)

Basic nursing care: Care that can be performed following a defined nursing procedure with minimal modification in which the responses of the patient to the nursing care are predictable.[23] (Chapter 1.4)

Board of Nursing: The state-specific licensing and regulatory body that sets the standards for safe nursing care, decides the scope of practice for nurses within its jurisdiction, and issues licenses to qualified candidates. (Chapter 1.3)

Certification: The formal recognition of specialized knowledge, skills, and experience demonstrated by the achievement of standards identified by a nursing specialty. (Chapter 1.4)

Chain of command: A hierarchy of reporting relationships in an agency that establishes accountability and lays out lines of authority and decision-making power. (Chapter 1.4)

Code of ethics: A code that applies normative, moral guidance for nurses in terms of what they ought to do, be, and seek. A code of ethics makes the primary obligations, values, and ideals of a profession explicit. (Chapter 1.6)

Dysphagia: Impaired swallowing. (Chapter 1.4)

Ethical principle: An ethical principle is a general guide, basic truth, or assumption that can be used with clinical judgment to determine a course of action. Four common ethical principles are beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), autonomy (control by the individual), and justice (fairness). (Chapter 1.6)

Evidence-based practice: A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and client, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.[24] (Chapter 1.8)

Expressive aphasia: The impaired ability to form words and speak. (Chapter 1.4)

Licensed Practical Nurse/Vocational Nurse (LPN/LVN): An individual who has completed a state-approved practical or vocational nursing program, passed the NCLEX-PN examination, and is licensed by their state Board of Nursing to provide client care.[25] (Chapter 1.4, Chapter 1.5)

Malpractice: A specific term that looks at a standard of care, as well as the professional status of the caregiver.[26] (Chapter 1.6)

Morality: Personal values, character, or conduct of individuals within communities and societies.[27] (Chapter 1.6)

Negligence: A “general term that denotes conduct lacking in due care, carelessness, and a deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would use in a particular set of circumstances.”[28] (Chapter 1.6)

Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC): Allows a nurse to have one multistate license with the ability to practice in the home state and other compact states. (Chapter 1.5)

Nursing: Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focused on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.[29] (Chapter 1.3)

Nurse Practice Act (NPA): Legislation enacted by each state that establishes regulations for nursing practice within that state by defining the requirements for licensure, as well as the scope of nursing practice. (Chapter 1.3)

Patient confidentiality: Keeping your client’s Protected Health Information (PHI) protected and known only by those health care team members directly providing care for the client. (Chapter 1.6)

Primary care: Care that is provided to clients to promote wellness and prevent disease from occurring. This includes health promotion, education, protection (such as immunizations), early disease screening, and environmental considerations. (Chapter 1.4)

Protocol: A precise and detailed written plan for a regimen of therapy.[30] (Chapter 1.3)

Provider: A physician, podiatrist, dentist, optometrist, or advanced practice nurse provider.[31] (Chapter 1.4)

Quality: The degree to which nursing services for health care consumers, families, groups, communities, and populations increase the likelihood of desirable outcomes and are consistent with evolving nursing knowledge.”[32] (Chapter 1.8)

Quality improvement: Combined and unceasing efforts of everyone–healthcare professionals, clients and their families, researchers, payers, planners and educators–to make the changes that will lead to better client outcomes (health), better system performance (care) and better professional development (learning). (Chapter 1.8)

Registered Nurse (RN): An individual who has graduated from a state-approved school of nursing, passed the NCLEX-RN examination, and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide client care.[33] (Chapter 1.4, Chapter 1.5)

Safety culture: A culture established within health care agencies that empowers nurses, nursing students, and other staff members to speak up about risks to clients and to report errors and near misses, all of which drive improvement in client care and reduce the incident of client harm. (Chapter 1.3)

Scope of practice: Services that a qualified health professional is deemed competent to perform and permitted to undertake – in keeping with the terms of their professional license. (Chapter 1.1)

Secondary care: Care that occurs when a person has contracted an illness or injury and is in need of medical care. (Chapter 1.4)

Tertiary care: A type of care that deals with the long-term effects from chronic illness or condition, with the purpose to restore physical and mental function that may have been lost. The goal is to achieve the highest level of functioning possible with this chronic illness. (Chapter 1.4)

Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP): Any unlicensed person, regardless of title, who performs tasks delegated by a nurse. This includes certified nursing aides/assistants (CNAs), patient care assistants (PCAs), patient care technicians (PCTs), state tested nursing assistants (STNAs), nursing assistants-registered (NA/Rs) or certified medication aides/assistants (MA-Cs). Certification of UAPs varies between jurisdictions.[34] (Chapter 1.4)

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Secondary IV Solution Administration.” This checklist is used when fluids are already being administered via the primary IV tubing and a second IV solution is administered.

View an instructor demonstration of Secondary IV Solution Administration[35]:

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: secondary IV fluid/medication, secondary IV tubing, alcohol wipe/scrub hubs, and tubing labels.

- Verify the provider order with the medication administration record (eMAR/MAR).

- Perform the first check of the rights of medication administration while withdrawing the IV solution and tubing from the medication dispensing unit. Check expiration dates on the fluid and the tubing and verify allergies.

- Verify compatibility of the secondary IV solution with the other IV fluids the patient is currently receiving.

- Remove the IV solution from the packaging and gently apply pressure to the bag while inspecting for tears or leaks. Check the color and clarity of the solution.

- Perform the second check of the rights of medication administration.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation).

- Perform the third check of the rights of medication administration at the patient's bedside.

- If the patient is receiving the medication for the first time, teach the patient and family (if appropriate) about the potential adverse reactions and other concerns related to the medication.

- Remove the secondary IV tubing from the packaging.

- Place the roller clamp to the “off” position.

- Remove the protective sheath from the IV spike and the cover from the tubing port of the IV solution.

- Insert the spike into the IV bag while maintaining sterility.

- Prime the secondary IV tubing. Back priming is considered best practice and is performed using an infusion pump or gravity with primary fluids attached:

- Vigorously cleanse the Y port closest to the drip chamber with an alcohol pad/scrub hub (or the agency required cleansing agent) for at least five seconds and allow it to dry.

- Connect the secondary tubing to the port closest to the drip chamber. Lower the secondary bag below the primary bag and allow the fluid from the primary bag to fill the secondary tubing. Fill the secondary tubing until it reaches the drip chamber, and then raise the secondary bag above the primary line.

- Hang the secondary IV solution on the IV pole with the primary bag lower than the secondary bag.

- Label the secondary tubing near the drip chamber.

- Set the infusion rate:

- For infusion pump: Set the volume to be infused and the rate (mL/hr) to be administered based on the provider order.

- For gravity: The roller clamp on the secondary tubing will be opened completely, and the roller clamp on the primary tubing will be adjusted to deliver the prescribed rate.

Take time to watch the IV fluid or medication to drip into the drip chamber to ensure the medication or fluid is flowing to the patient.

Take time to watch the IV fluid or medication to drip into the drip chamber to ensure the medication or fluid is flowing to the patient. - Assess the patient’s IV site for signs and symptoms of vein irritation or infiltration after infusion begins. Do not proceed with administering secondary fluids if there are any concerns about the site.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

IV catheter on right hand discontinued with catheter tip intact. Site free from redness, warmth, tenderness, or swelling. Gauze applied with pressure for one minute with no bleeding noted. Dressing applied to site.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

IV catheter on right hand discontinued with IV catheter tip intact. Site free from redness, warmth, tenderness, or swelling. Gauze applied with pressure for one minute. Bleeding noted to continue around gauze dressing. Pressure held for five minutes, and hemostasis achieved. Dressing applied to site.