2. Basic Communication Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) and Amy Ertwine

Effective communication is one of the Standards of Professional Performance established by the American Nurses Association. The standard states, “The registered nurse communicates effectively in all areas of practice.”[1] There are several concepts related to effective communication such as demonstrating appropriate verbal and nonverbal communication, using assertive communication, being aware of personal space, and overcoming common barriers to effective communication.

Types of Communication

Verbal Communication

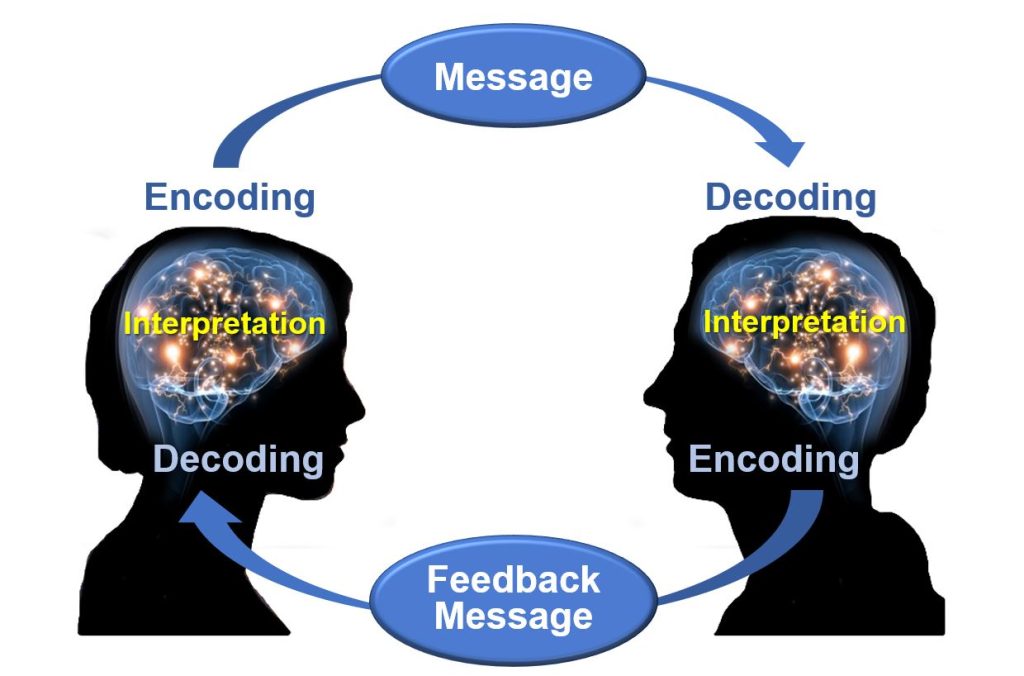

Effective communication requires each interaction to include a sender of the message, a clear and concise message, and a receiver who can decode and interpret that message. The receiver also provides a feedback message back to the sender in response to the received message. See Figure 2.1[2] for an image of effective communication between a sender and receiver.

Nurses assist clients and their family members to understand health care needs and treatments by using verbal, nonverbal, and written communication. Verbal communication is more than just talking. Effective verbal communication is defined as an exchange of information using words understood by the receiver in a way that conveys professional caring and respect.[3] Nurses who speak using extensive medical jargon or slang may create an unintended barrier to their own verbal communication processes. When communicating with others, it is important for the nurse to assess the receiver’s preferred method of communication and individual receiver characteristics that might influence communication, and subsequently adapt communication to meet the receiver’s needs. For example, the nurse may adapt postsurgical verbal instruction for a pediatric versus an adult client. Although the information requirements regarding signs of infection, pain management, etc., might be similar, the way in which information is provided may be quite different based on developmental level. Regardless of the individual adaptations that are made, the nurse must be sure to always verify client understanding.

Nonverbal Communication

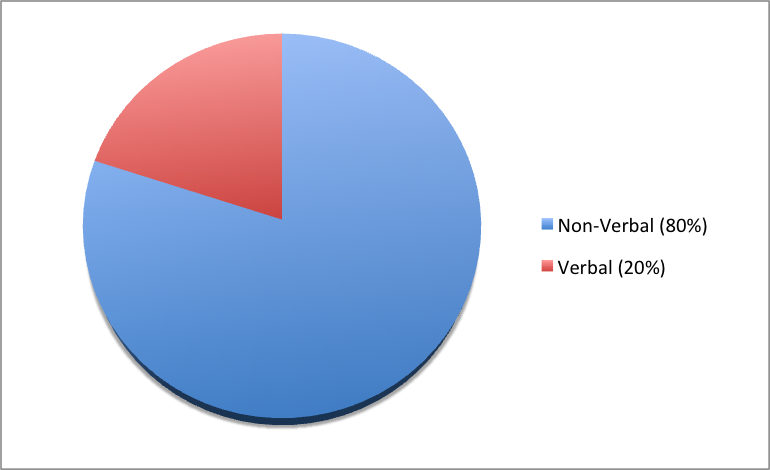

In addition to communicating verbally, the nurse must also be aware of messages sent by nonverbal communication. Nonverbal communication includes facial expressions, tone of voice, pace of the conversation, and body language. Nonverbal communication is more powerful than the verbal message and can have a tremendous impact on the communication experience, with up to 80% of communication being nonverbal communication (see Figure 2.2[4]). The importance of nonverbal communication during communication has also been described in percentages of 55, 38, and 7, meaning 55% of communication is body language, 38% is tone of voice, and 7% is the actual words spoken.[5]

Nonverbal communication includes body language and facial expressions, tone of voice, and pace of the conversation. For example, compare the nonverbal communication messages in Figures 2.3[6] and 2.4.[7] What nonverbal cues do you notice about both toddlers?

Nurses should be attentive to their nonverbal communication cues and the messages they provide to clients and their families. Nurses should be purposeful in their use of nonverbal communication that conveys a feeling of caring.[8] What nonverbal cues do you notice about the nurse in Figure 2.5[9] that provide a perception of professional caring?

Nurses use nonverbal communication such as directly facing clients at eye level, leaning slightly forward, and making eye contact to communicate they care about what the person is telling them and they have their full attention.[10]

![]()

It is common for health care team members in an acute care setting to enter a client’s room and begin interacting with a client who is seated or lying in bed. However, it is important to remember that initial or sensitive communication exchanges are best received by the client if the nurse and client are at eye level. Bringing a chair to the client’s bedside can help to facilitate engagement in the communication exchange. SOLER is common mnemonic used to facilitate nonverbal communication (sit with open posture and lean in with good eye contact in a relaxed manner).

Communication Styles

In addition to verbal and nonverbal communication, people communicate with others using one of three styles: passive, aggressive, or assertive. A passive communicator puts the rights of others before their own. Passive communicators tend to be apologetic or sound tentative when they speak and often do not speak up if they feel they are being wronged. Aggressive communicators, on the other hand, come across as advocating for their own rights despite possibly violating the rights of others. They tend to communicate in a way that tells others their feelings don’t matter. Assertive communicators, in contrast, respect the rights of others while also standing up for their own ideas and rights when communicating. An assertive person is direct, but not insulting or offensive.[11] Assertive communication refers to a way of conveying information that describes the facts and the sender’s feelings without disrespecting the receiver’s feelings. Using “I” messages such as, “I feel…,” “I understand…,” or “Help me to understand…” are strategies for assertive communication. This method of communicating is different from aggressive communication that uses “you” messages and can feel as if the sender is verbally attacking the receiver rather than dealing with the issue at hand. For example, instead of saying to a coworker, “Why is it always so messy in your clients’ rooms? I dread following you on the next shift!,” an assertive communicator would use “I” messages to say, “I feel frustrated spending the first part of my shift decluttering our clients’ rooms. Help me understand why it is a challenge to keep things organized during your shift?”

Using assertive communication is an effective way to solve problems with clients, coworkers, and health care team members.

View this supplementary YouTube video on How to Communicate Assertively.

Personal Space

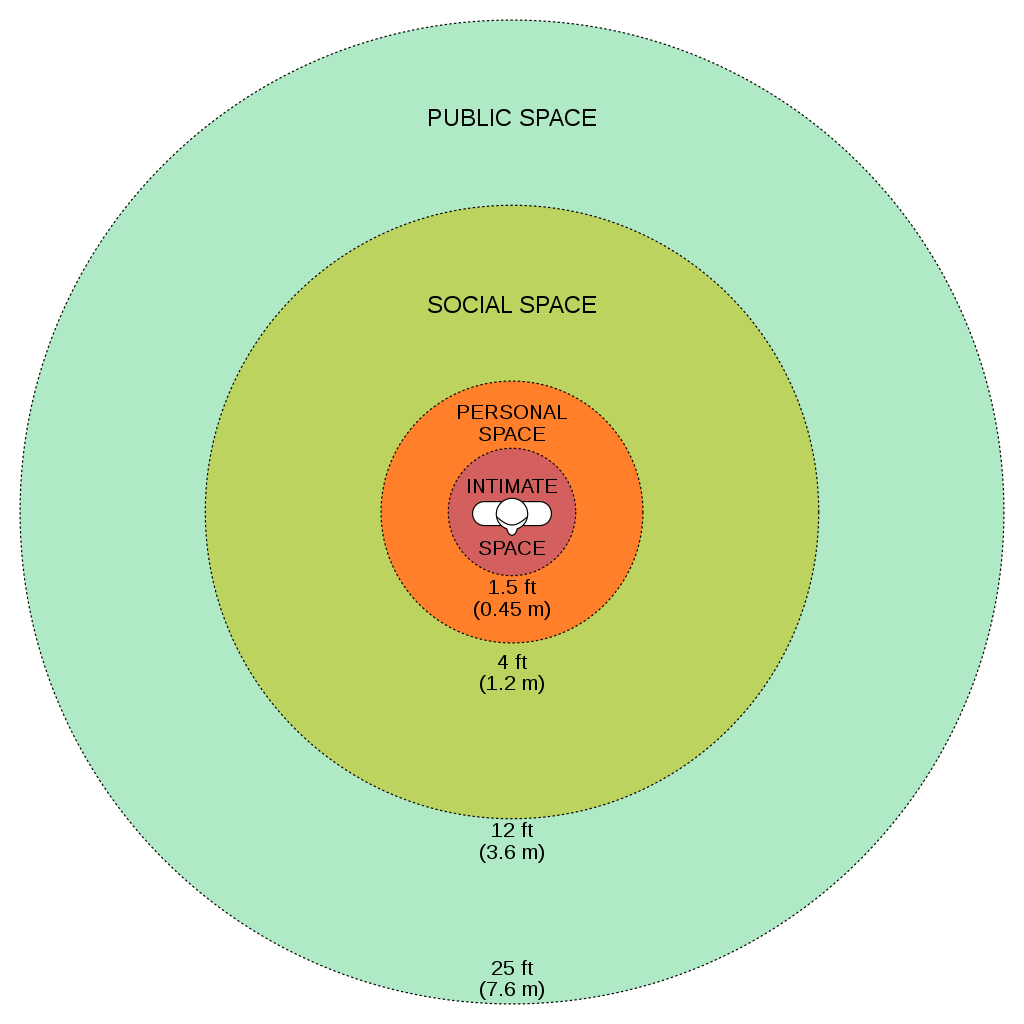

While being aware of verbal and nonverbal messages and communicating assertively, it is also important to be aware of others’ personal space. Proxemics is the study of personal space and provides guidelines for professional communication. The public zone is over 10 feet of distance between people and generally avoids physical contact. The social zone is four to 10 feet of distance between people. It is used during social interactions and business settings. The personal zone is 18 inches to four feet of space and is generally reserved for friends and family. Less than 18 inches is reserved for close relationships but may be invaded when in crowds or playing sports.[12] Nurses usually communicate within the social zone to maintain professional boundaries. However, when assessing clients and performing procedures, nurses often move into a client’s personal zone. Nurses must be aware of clients’ feelings of psychological discomfort that can occur when invading this zone. Additionally, cultural considerations may impact the appropriateness of personal space when providing client care. See Figure 2.6 for example of personal space zones.[13]

Overcoming Common Barriers to Communication

Nurses must reflect on personal factors that influence their ability to communicate effectively. There are many factors that can cause the message you are trying to communicate to become distorted and not perceived by the receiver in the way you intended. For this reason, is important to seek feedback that your message is clearly understood. Nurses must be aware of these potential barriers and try to reduce their impact by continually seeking feedback and checking understanding.[14]

Common barriers to communication in health care and strategies to overcome them are described in the following box.[15]

Common Barriers to Communication in Health Care

- Jargon: Avoid using medical terminology, complicated, or unfamiliar words. When communicating with clients, explain information in plain language that is easy to understand by those without a medical or nursing background.

- Lack of attention: Nurses are typically very busy with several tasks to complete for multiple clients. It is easy to become focused on the tasks instead of the client. When entering a client’s room, it is helpful to pause, take a deep breath, and mindfully focus on the client in front of you to give them your full attention. Clients should feel as if they are the center of your attention when you are with them, no matter how many other things you have going on.

- Noise and other distractions: Health care environments can be very noisy with people talking in the room or hallway, the TV playing, alarms beeping, and pages occurring overhead. Create a calm, quiet environment when communicating with clients by closing doors to the hallway, reducing the volume of the TV, or moving to a quieter area, if possible.

- Light: A room that is too dark or too light can create communication barriers. Ensure the lighting is appropriate according to the client’s preference.

- Hearing and speech problems: If your client has hearing or speech problems, implement strategies to enhance communication. See the “Adapting Your Communication” subsection below for strategies to address hearing and speech problems.

- Language differences: If English is not your client’s primary language, it is important to seek a medical interpreter and to also provide written handouts in the client’s preferred language when possible. Most agencies have access to an interpreter service available by phone if they are not available on-site.

- Differences in cultural beliefs: The norms of social interaction vary greatly in different cultures, as well as the ways that emotions are expressed. For example, the concept of personal space varies among cultures, and some clients are stoic about pain whereas others are more verbally expressive. Read more about caring for diverse clients in the “Diverse Patients” chapter.

- Psychological barriers: Psychological states of the sender and the receiver affect how the message is sent, received, and perceived. For example, if nurses are feeling stressed and overwhelmed with required tasks, the nonverbal communication associated with their messages such as lack of eye contact, a hurried pace, or a short tone can affect how the client perceives the message. If a client is feeling stressed, they may not be able to “hear” the message or they may perceive it differently than it was intended. It is important to be aware of signs of the stress response in ourselves and our clients and implement appropriate strategies to manage the stress response. See the box below for more information about strategies to manage the stress response.

- Physiological barriers: It is important to be aware of clients’ potential physiological barriers when communicating. For example, if a client is in pain, they are less likely to hear and remember what was said, so pain relief should be provided as needed before providing client education. However, it is also important to remember that sedatives and certain types of pain medications often impair the client’s ability to receive and perceive messages so health care documents cannot be signed by a client after receiving these types of medications.

- Physical barriers for nonverbal communication: Providing information via e-mail or text is often less effective than face-to-face communication. The inability to view the nonverbal communication associated with a message such as tone of voice, facial expressions, and general body language often causes misinterpretation of the message by the receiver. When possible, it is best to deliver important information to others using face-to-face communication so that nonverbal communication is included with the message.

- Differences in perception and viewpoints: Everyone has their own beliefs and perspectives and wants to feel “heard.” When clients feel their beliefs or perspectives are not valued, they often become disengaged from the conversation or the plan of care. Nurses should provide health care information in a nonjudgmental manner, even if the client’s perspectives, viewpoints, and beliefs are different from their own.

Managing the Stress Response[16]

The stress response is a common psychological barrier to effective communication. It can affect the message sent by the sender or how it is received by the receiver. The stress response is a common reaction to life events, such as a nurse feeling stressed by being overwhelmed with tasks to complete for multiple clients, or a client feeling stressed when admitted to a hospital or receiving a new diagnosis. Symptoms of the stress response include irritability, sweaty palms, a racing heart, difficulty concentrating, and impaired sleep. It is important to recognize symptoms of the stress response in ourselves and our clients and use strategies to manage the stress response when communicating. Strategies to manage the stress response include the following:

- Use relaxation breathing. Become aware of your breathing. Take a deep breath in your nose and blow it out through your mouth. Repeat this process at least three times in succession and then as often as needed throughout the day.

- Make healthy diet choices. Avoid caffeine, nicotine, and junk food because these items can increase feelings of anxiety or being on edge.

- Make time for exercise. Exercise stimulates the release of natural endorphins that reduce the body’s stress response and also helps to improve sleep.

- Get enough sleep. Set aside at least 30 minutes before going to bed to wind down from the busyness of the day. Avoid using electronic devices like cell phones before bedtime because the backlight can affect negatively impact sleep.

- Use progressive relaxation. There are several types of relaxation techniques that focus on reducing muscle tension and using mental imagery to induce calmness. Progressive relaxation generally includes the following steps:

- Start by lying down somewhere comfortable and firm, such as a rug or mat on the floor. Get yourself comfortable.

- Relax and try to let your mind go blank. Breathe slowly, deeply, and comfortably, while gradually and consciously relaxing all your muscles, one by one.

- Work around the body one main muscle area at a time, breathing deeply, calmly, and evenly. For each muscle group, clench the muscles tightly and hold for a few seconds, and then relax them completely. Repeat the process, noticing how it feels. Do this for each of your feet, calves, thighs, buttocks, stomach, arms, hands, shoulders, and face.

Media Attributions

- Osgood-Schramm-model-of-communication

- Constituents_of_Communication

- 425407359_b67fdf9b59_h

- 1024px-Personal_Space.svg

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Osgood-Schramm-model-of-communication.jpg“ by Jordan Smith at eCampus Ontario is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/communicationatwork/chapter/1-3-the-communication-process/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Relations by LibreTexts and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Constituents of Communication.png” by jb11ko, lb13an, ad14xz, jb12xu is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Thompson, J. (2011). Is nonverbal communication a numbers game? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/beyond-words/201109/is-nonverbal-communication-numbers-game ↵

- “I’m angry” by WiLPrZ is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ↵

- “Happy Toddler” by Chris Bloom is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Relations by LibreTexts and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “PIXNIO-42752-4542x3003.jpg” by James Gathany, Judy Schmidt, USCDCP is in the Public Domain ↵

- Stickley, T. (2011). From SOLER to SURETY for effective non-verbal communication. Nurse Education in Practice, 11(6), 395-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2011.03.021 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Relations by LibreTexts and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Psychology Today. (n.d.). Proxemics. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/proxemics ↵

- “Personal Space.svg” by WebHamster is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- SkillsYouNeed. (n.d.). Barriers to effective communication. https://www.skillsyouneed.com/ips/barriers-communication.html ↵

- SkillsYouNeed. (n.d.). Barriers to effective communication. https://www.skillsyouneed.com/ips/barriers-communication.html ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2019). Healthy ways to handle life's stressors. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/tips ↵

In addition to implementing safety strategies to improve safe client care, leaders of a health care agency must also establish a culture of safety. A culture of safety reflects the behaviors, beliefs, and values within and across all levels of an organization as they relate to safety and clinical excellence, with a focus on people. In 2021 The Joint Commission released a sentinel event regarding the essential role of leadership in establishing a culture of safety. According to The Joint Commission, leadership has an obligation to be accountable for protecting the safety of all health care consumers, including clients, employees, and visitors. Without adequate leadership and an effective culture of safety, there is higher risk for adverse events. Inadequate leadership can contribute to adverse effects in a variety of ways, including, but not limited to, the following[1]:

- Insufficient support of client safety event reporting

- Lack of feedback or response to staff and others who report safety vulnerabilities

- Allowing intimidation of staff who report events

- Refusing to consistently prioritize and implement safety recommendations

- Not addressing staff burnout

Three components of a culture of safety are the following[2]:

- Just Culture: People are encouraged, even rewarded, for providing essential safety-related information, but clear lines are drawn between human error and at-risk or reckless behaviors.

- Reporting Culture: People report errors and near-misses.

- Learning Culture: The willingness and the competence to draw the right conclusions from safety information systems, and the will to implement major reforms when their need is indicated.

The American Nurses Association further describes a culture of safety as one that includes openness and mutual respect when discussing safety concerns and solutions without shifting to individual blame, a learning environment with transparency and accountability, and reliable teams. In contrast, complexity, lack of clear measures, hierarchical authority, the “blame game,” and lack of leadership are examples of barriers that do not promote a culture of safety. If staff fear reprisal for mistakes and errors, they will be less likely to report errors, processes will not be improved, and client safety will continue to be impaired. See the following box for an example of safety themes established during a health care institution’s implementation of a culture of safety.

Safety Themes in a Culture of Safety[3]

Kaiser Permantente implemented a culture of safety in 2001 that focused on instituting the following six strategic themes:

- Safe culture: Creating and maintaining a strong safety culture, with client safety and error reduction embraced as shared organizational values.

- Safe care: Ensuring that the actual and potential hazards associated with high-risk procedures, processes, and client care populations are identified, assessed, and managed in a way that demonstrates continuous improvement and ultimately ensures that clients are free from accidental injury or illness.

- Safe staff: Ensuring that staff possess the knowledge and competence to perform required duties safely and contribute to improving system safety performance.

- Safe support systems: Identifying, implementing, and maintaining support systems—including knowledge-sharing networks and systems for responsible reporting—that provide the right information to the right people at the right time.

- Safe place: Designing, constructing, operating, and maintaining the environment of health care to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness.

- Safe clients: Engaging clients and their families in reducing medical errors, improving overall system safety performance, and maintaining trust and respect.

A strong safety culture encourages all members of the health care team to identify and reduce risks to client safety by reporting errors and near misses so that root cause analysis can be performed and identified risks are removed from the system. However, in a poorly defined and implemented culture of safety, staff often conceal errors due to fear or shame. Nurses have been traditionally trained to believe that clinical perfection is attainable, and that “good” nurses do not make errors. Errors are perceived as being caused by carelessness, inattention, indifference, or uninformed decisions. Although expecting high standards of performance is appropriate and desirable, it can become counterproductive if it creates an expectation of perfection that impacts the reporting of errors and near misses. If employees feel shame when they make an error, they may feel pressure to hide or cover up errors. Evidence indicates that approximately three of every four errors are detected by those committing them, as opposed to being detected by an environmental cue or another person. Therefore, employees need to be able to trust that they can fully report errors without fear of being wrongfully blamed. This provides the agency with the opportunity to learn how to further improve processes and prevent future errors from occurring. For many organizations, the largest barrier in establishing a culture of safety is the establishment of trust. A model called “Just Culture” has successfully been implemented in many agencies to decrease the “blame game,” promote trust, and improve the reporting of errors.

Just Culture

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture, stating, “Traditionally, healthcare’s culture has held individuals accountable for all errors or mishaps that befall clients under their care. By contrast, a Just Culture recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. A Just Culture also recognizes many individual or ‘active’ errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, in contrast to a culture that touts ‘no blame’ as its governing principle, a Just Culture does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to clients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).”

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three causes of errors. Consequences of errors are based on whether the error is a simple human error or caused by at-risk or reckless behavior.

- Simple human error: A simple human error occurs when an individual inadvertently does something other than what should have been done. Most medical errors are the result of human error due to poor processes, programs, education, environmental issues, or situations. These errors are managed by correcting the cause, looking at the process, and fixing the deviation. For example, a nurse appropriately checks the rights of medication administration three times, but due to the similar appearance and names of two different medications stored next to each other in the medication dispensing system, administers the incorrect medication to a client. In this example, a root cause analysis reveals a system issue that must be modified to prevent future errors (e.g., change the labelling and storage of look alike-sound alike medication).

- At-risk behavior: An error due to at-risk behavior occurs when a behavioral choice is made that increases risk where the risk is not recognized or is mistakenly believed to be justified. For example, a nurse scans a client’s medication with a barcode scanner prior to administration, but an error message appears on the scanner. The nurse mistakenly interprets the error to be a technology problem and proceeds to administer the medication instead of stopping the process and further investigating the error message, resulting in the wrong dosage of a medication being administered to the client. In this case, ignoring the error message on the scanner can be considered “at-risk behavior” because the behavioral choice was considered justified by the nurse at the time.

- Reckless behavior: Reckless behavior is an error that occurs when an action is taken with conscious disregard for a substantial and unjustifiable risk.[4] For example, a nurse arrives at work intoxicated and administers the wrong medication to the wrong client. This error is considered due to reckless behavior because the decision to arrive intoxicated was made with conscious disregard for substantial risk.

These examples show three different causes of medication errors that would result in different consequences to the employee based on the Just Culture model. Under the Just Culture model, after root cause analysis is completed, system-wide changes are made to decrease factors that contributed to the error. Managers appropriately hold individuals accountable for errors if they were due to simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behaviors.

If an individual commits a simple human error, managers console the individual and consider changes in training, procedures, and processes. In the “simple human error” above, system-wide changes would be made to change the label and location of the medication to prevent future errors from occurring with the same medication.

Individuals committing at-risk behavior are held accountable for their behavioral choice and often require coaching with incentives for less risky behaviors and situational awareness. In the “at-risk behavior” example above where the nurse ignored an error message on the barcode scanner, mandatory training on using a barcode scanner and responding to errors would be implemented, and the manager would track the employee’s correct usage of the barcode scanner for several months following training.

If an individual demonstrates reckless behavior, remedial action and/or punitive action is taken.[5] In the “reckless behavior” example above, the manager would report the nurse’s behavior to the state's Board of Nursing with mandatory substance abuse counseling to maintain their nursing license. Employment may be terminated with consideration of patterns of behavior.

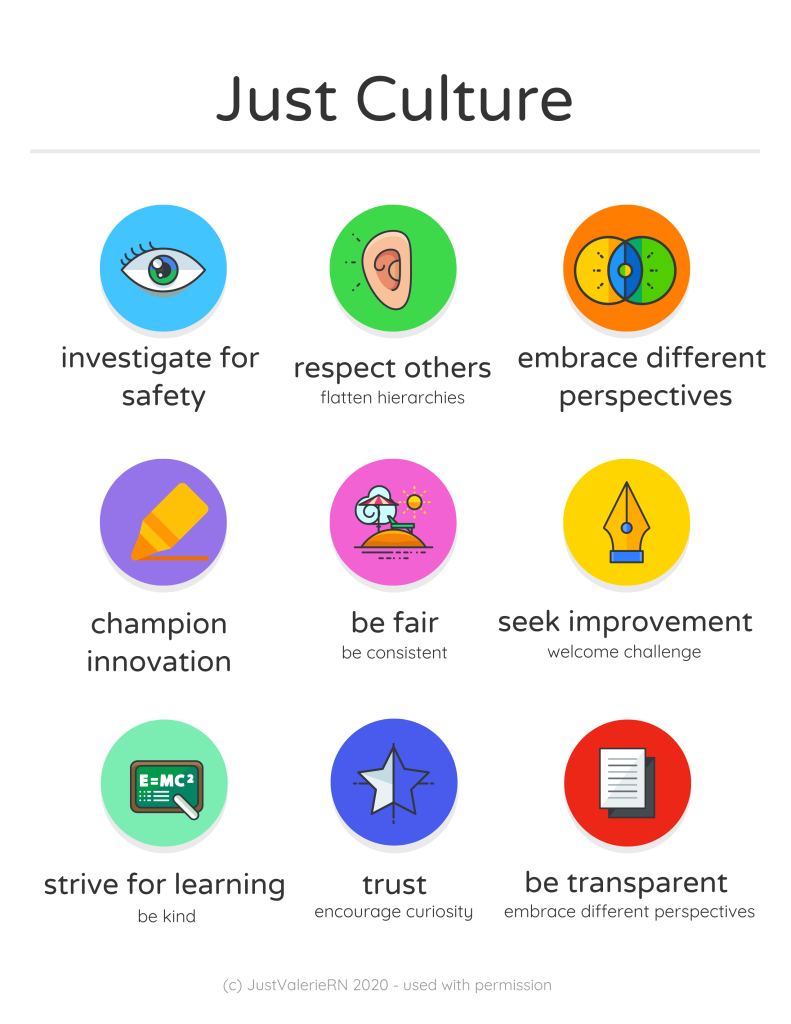

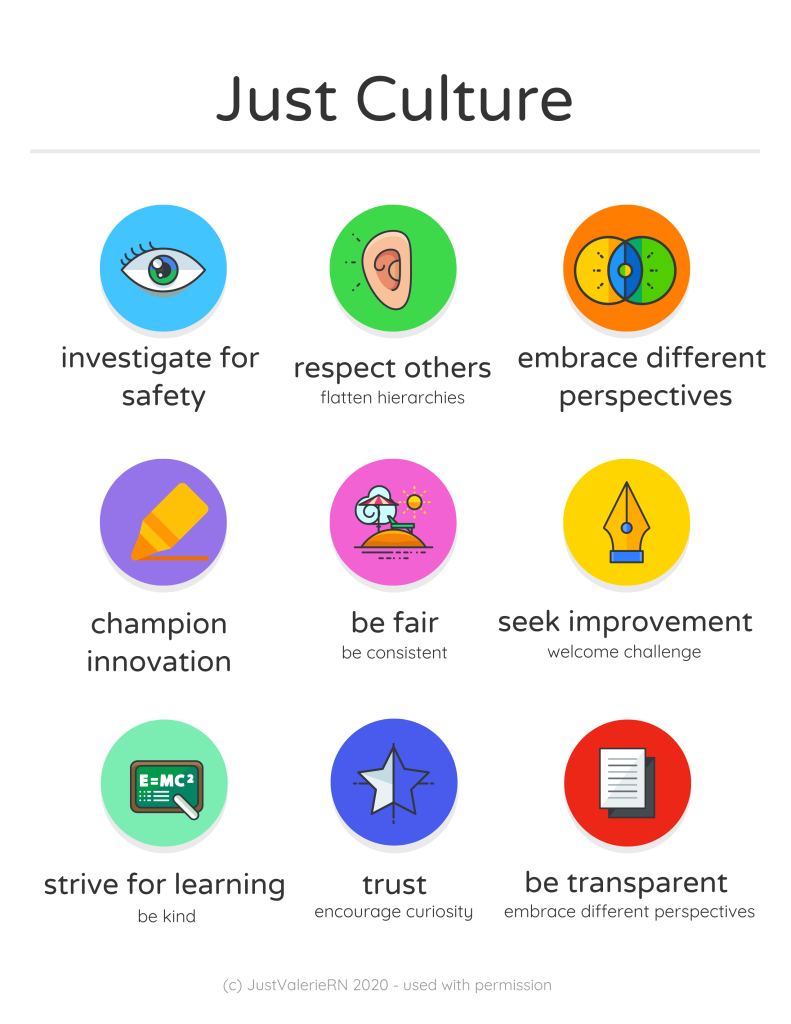

A Just Culture in which employees aren't afraid to report errors is a highly successful way to enhance client safety, increase staff and client satisfaction, and improve outcomes. Success is achieved through good communication, effective management of resources, and an openness to changing processes to ensure the safety of clients and employees. The infographic in Figure 5.4[6] illustrates the components of a culture of safety and Just Culture.

The principles of culture of safety, including Just Culture, Reporting Culture, and Learning Culture are also being adopted in nursing education. It’s understood that mistakes are part of learning and that a shared accountability model promotes individual- and system-level learning for improved client safety. Under a shared accountability model, students are responsible for the following[7]:

- Being fully prepared for clinical experiences, including laboratory and simulation assignments

- Being rested and mentally ready for a challenging learning environment

- Accepting accountability for their part in contributing to a safe learning environment

- Behaving professionally

- Reporting their own errors and near mistakes

- Keeping up-to-date with current evidence-based practice

- Adhering to ethical and legal standards

Students know they will be held accountable for their actions, but will not be blamed for system faults that lie beyond their control. They can trust that a fair process will be used to determine what went wrong if a client care error or near miss occurs. Student errors and near misses are addressed based on an investigation determining if it was simple human error, an at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. For example, a simple human error by a student can be addressed with coaching and additional learning opportunities to remedy the knowledge deficit. However, if a student acts with recklessness (for example, repeatedly arrives to clinical unprepared despite previous faculty feedback or falsely documents an assessment or procedure), they are appropriately and fairly disciplined, which may include dismissal from the program.[8]

In addition to implementing safety strategies to improve safe client care, leaders of a health care agency must also establish a culture of safety. A culture of safety reflects the behaviors, beliefs, and values within and across all levels of an organization as they relate to safety and clinical excellence, with a focus on people. In 2021 The Joint Commission released a sentinel event regarding the essential role of leadership in establishing a culture of safety. According to The Joint Commission, leadership has an obligation to be accountable for protecting the safety of all health care consumers, including clients, employees, and visitors. Without adequate leadership and an effective culture of safety, there is higher risk for adverse events. Inadequate leadership can contribute to adverse effects in a variety of ways, including, but not limited to, the following[9]:

- Insufficient support of client safety event reporting

- Lack of feedback or response to staff and others who report safety vulnerabilities

- Allowing intimidation of staff who report events

- Refusing to consistently prioritize and implement safety recommendations

- Not addressing staff burnout

Three components of a culture of safety are the following[10]:

- Just Culture: People are encouraged, even rewarded, for providing essential safety-related information, but clear lines are drawn between human error and at-risk or reckless behaviors.

- Reporting Culture: People report errors and near-misses.

- Learning Culture: The willingness and the competence to draw the right conclusions from safety information systems, and the will to implement major reforms when their need is indicated.

The American Nurses Association further describes a culture of safety as one that includes openness and mutual respect when discussing safety concerns and solutions without shifting to individual blame, a learning environment with transparency and accountability, and reliable teams. In contrast, complexity, lack of clear measures, hierarchical authority, the “blame game,” and lack of leadership are examples of barriers that do not promote a culture of safety. If staff fear reprisal for mistakes and errors, they will be less likely to report errors, processes will not be improved, and client safety will continue to be impaired. See the following box for an example of safety themes established during a health care institution’s implementation of a culture of safety.

Safety Themes in a Culture of Safety[11]

Kaiser Permantente implemented a culture of safety in 2001 that focused on instituting the following six strategic themes:

- Safe culture: Creating and maintaining a strong safety culture, with client safety and error reduction embraced as shared organizational values.

- Safe care: Ensuring that the actual and potential hazards associated with high-risk procedures, processes, and client care populations are identified, assessed, and managed in a way that demonstrates continuous improvement and ultimately ensures that clients are free from accidental injury or illness.

- Safe staff: Ensuring that staff possess the knowledge and competence to perform required duties safely and contribute to improving system safety performance.

- Safe support systems: Identifying, implementing, and maintaining support systems—including knowledge-sharing networks and systems for responsible reporting—that provide the right information to the right people at the right time.

- Safe place: Designing, constructing, operating, and maintaining the environment of health care to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness.

- Safe clients: Engaging clients and their families in reducing medical errors, improving overall system safety performance, and maintaining trust and respect.

A strong safety culture encourages all members of the health care team to identify and reduce risks to client safety by reporting errors and near misses so that root cause analysis can be performed and identified risks are removed from the system. However, in a poorly defined and implemented culture of safety, staff often conceal errors due to fear or shame. Nurses have been traditionally trained to believe that clinical perfection is attainable, and that “good” nurses do not make errors. Errors are perceived as being caused by carelessness, inattention, indifference, or uninformed decisions. Although expecting high standards of performance is appropriate and desirable, it can become counterproductive if it creates an expectation of perfection that impacts the reporting of errors and near misses. If employees feel shame when they make an error, they may feel pressure to hide or cover up errors. Evidence indicates that approximately three of every four errors are detected by those committing them, as opposed to being detected by an environmental cue or another person. Therefore, employees need to be able to trust that they can fully report errors without fear of being wrongfully blamed. This provides the agency with the opportunity to learn how to further improve processes and prevent future errors from occurring. For many organizations, the largest barrier in establishing a culture of safety is the establishment of trust. A model called “Just Culture” has successfully been implemented in many agencies to decrease the “blame game,” promote trust, and improve the reporting of errors.

Just Culture

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture, stating, “Traditionally, healthcare’s culture has held individuals accountable for all errors or mishaps that befall clients under their care. By contrast, a Just Culture recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. A Just Culture also recognizes many individual or ‘active’ errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, in contrast to a culture that touts ‘no blame’ as its governing principle, a Just Culture does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to clients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).”

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three causes of errors. Consequences of errors are based on whether the error is a simple human error or caused by at-risk or reckless behavior.

- Simple human error: A simple human error occurs when an individual inadvertently does something other than what should have been done. Most medical errors are the result of human error due to poor processes, programs, education, environmental issues, or situations. These errors are managed by correcting the cause, looking at the process, and fixing the deviation. For example, a nurse appropriately checks the rights of medication administration three times, but due to the similar appearance and names of two different medications stored next to each other in the medication dispensing system, administers the incorrect medication to a client. In this example, a root cause analysis reveals a system issue that must be modified to prevent future errors (e.g., change the labelling and storage of look alike-sound alike medication).

- At-risk behavior: An error due to at-risk behavior occurs when a behavioral choice is made that increases risk where the risk is not recognized or is mistakenly believed to be justified. For example, a nurse scans a client’s medication with a barcode scanner prior to administration, but an error message appears on the scanner. The nurse mistakenly interprets the error to be a technology problem and proceeds to administer the medication instead of stopping the process and further investigating the error message, resulting in the wrong dosage of a medication being administered to the client. In this case, ignoring the error message on the scanner can be considered “at-risk behavior” because the behavioral choice was considered justified by the nurse at the time.

- Reckless behavior: Reckless behavior is an error that occurs when an action is taken with conscious disregard for a substantial and unjustifiable risk.[12] For example, a nurse arrives at work intoxicated and administers the wrong medication to the wrong client. This error is considered due to reckless behavior because the decision to arrive intoxicated was made with conscious disregard for substantial risk.

These examples show three different causes of medication errors that would result in different consequences to the employee based on the Just Culture model. Under the Just Culture model, after root cause analysis is completed, system-wide changes are made to decrease factors that contributed to the error. Managers appropriately hold individuals accountable for errors if they were due to simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behaviors.

If an individual commits a simple human error, managers console the individual and consider changes in training, procedures, and processes. In the “simple human error” above, system-wide changes would be made to change the label and location of the medication to prevent future errors from occurring with the same medication.

Individuals committing at-risk behavior are held accountable for their behavioral choice and often require coaching with incentives for less risky behaviors and situational awareness. In the “at-risk behavior” example above where the nurse ignored an error message on the barcode scanner, mandatory training on using a barcode scanner and responding to errors would be implemented, and the manager would track the employee’s correct usage of the barcode scanner for several months following training.

If an individual demonstrates reckless behavior, remedial action and/or punitive action is taken.[13] In the “reckless behavior” example above, the manager would report the nurse’s behavior to the state's Board of Nursing with mandatory substance abuse counseling to maintain their nursing license. Employment may be terminated with consideration of patterns of behavior.

A Just Culture in which employees aren't afraid to report errors is a highly successful way to enhance client safety, increase staff and client satisfaction, and improve outcomes. Success is achieved through good communication, effective management of resources, and an openness to changing processes to ensure the safety of clients and employees. The infographic in Figure 5.4[14] illustrates the components of a culture of safety and Just Culture.

The principles of culture of safety, including Just Culture, Reporting Culture, and Learning Culture are also being adopted in nursing education. It’s understood that mistakes are part of learning and that a shared accountability model promotes individual- and system-level learning for improved client safety. Under a shared accountability model, students are responsible for the following[15]:

- Being fully prepared for clinical experiences, including laboratory and simulation assignments

- Being rested and mentally ready for a challenging learning environment

- Accepting accountability for their part in contributing to a safe learning environment

- Behaving professionally

- Reporting their own errors and near mistakes

- Keeping up-to-date with current evidence-based practice

- Adhering to ethical and legal standards

Students know they will be held accountable for their actions, but will not be blamed for system faults that lie beyond their control. They can trust that a fair process will be used to determine what went wrong if a client care error or near miss occurs. Student errors and near misses are addressed based on an investigation determining if it was simple human error, an at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. For example, a simple human error by a student can be addressed with coaching and additional learning opportunities to remedy the knowledge deficit. However, if a student acts with recklessness (for example, repeatedly arrives to clinical unprepared despite previous faculty feedback or falsely documents an assessment or procedure), they are appropriately and fairly disciplined, which may include dismissal from the program.[16]

“Prevent residents from falling” is one of the National Patient Safety Goals for nursing care centers. Client falls, whether in the nursing care center, home, or hospital, are very common and can cause serious injury and death. Older adults have the highest risk of falling. Each year, 3 million older people are treated in emergency departments for fall injuries, and over 800,000 clients a year are hospitalized because of a head injury or hip fracture resulting from a fall. Many older adults who fall, even if they’re not injured, become afraid of falling. This fear may cause them to limit their everyday activities. However, when a person is less active, they become weaker, which further increases their chances of falling.[17]

Many conditions contribute to client falls, including the following:[18]

- Lower body weakness

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Difficulties with walking and balance

- Medications, such as tranquilizers, sedatives, antihypertensives, or antidepressants

- Vision problems

- Foot pain or poor footwear

- Environmental hazards, such as throw rugs or clutter that can cause tripping

Most falls are caused by a combination of risk factors. The more risk factors a person has, the greater their chances of falling. Many risk factors can be changed or modified to help prevent falls.

The Centers for Disease Control has developed a program called “STEADI - Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries” to help reduce the risk of older adults from falling at home. Three screening questions to determine risk for falls are as follows:

- Do you feel unsteady when standing or walking?

- Do you have worries about falling?

- Have you fallen in the past year? If yes, how many times? Were you injured?

If the individual answers “Yes” to any of these questions, further assessment of risk factors is performed.[19]

Read more information about preventing falls in older adults at CDC's Older Adult Fall Prevention.

Fall Assessment Tools

By virtue of being ill, all hospitalized clients are at risk for falls, but some clients are at higher risk than others. Assessment is an ongoing process with the goal of identifying a client’s specific risk factors and implementing interventions in their care plan to decrease their risk of falling. Commonly used fall assessment tools used to identify clients at high risk for falls are the Morse Fall Scale, the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model, and the Hester Davis Scale for fall risk assessment. Read more about these fall risk assessment tools using the hyperlinks provided below. Key risk factors for falls in hospitalized clients are as follows:[20]

- History of falls: All clients with a recent history of falls, such as a fall in the past three months, should be considered at higher risk for future falls.

- Mobility problems and use of assistive devices: Clients who have problems with their gait or require an assistive device (such as a cane or a walker) for mobility are more likely to fall.

- Medications: Clients taking several prescription medications or those taking medications that could cause sedation, confusion, impaired balance, or orthostatic blood pressure changes are at higher risk for falls.

- Mental status: Clients with delirium, dementia, or psychosis may be agitated and confused, putting them at risk for falls.

- Incontinence: Clients who have urinary frequency or who have frequent toileting needs are at higher fall risk.

- Equipment: Clients who are tethered to equipment such as an IV pole or a Foley catheter are at higher risk of tripping.

- Impaired vision: Clients with impaired vision or those who require glasses but who are not wearing them are at a higher fall risk because of their decreased recognition of an environmental hazard.

- Orthostatic hypotension: Clients whose blood pressure drops upon standing often experience light-headedness or dizziness that can cause falls.[21]

View these common fall risk assessment tools:

Interventions to Prevent Falls

Universal fall precautions are established for all clients to reduce their risk for falling. In addition to universal fall precautions, a care plan is created based on the client's fall risk assessment findings to address their specific risks and needs.

Universal Fall Precautions

Falls are the most commonly reported client safety incidents in the acute care setting. Hospitals pose an inherent fall risk due to the unfamiliarity of the environment and various hazards in the hospital room that pose a risk. During inpatient care, nurses assess their clients’ risk for falling during every shift and implement interventions to reduce the risk of falling. Universal fall precautions have been developed that apply to all clients all the time. Universal fall precautions are called "universal" because they apply to all clients, regardless of fall risk, and revolve around keeping the client's environment safe and comfortable.[24]

Universal fall precautions include the following:

- Familiarize the client with the environment.

- Have the client demonstrate call light use.

- Maintain the call light within reach. See Figure 5.5[25] for an image of a call light.

- Keep the client's personal possessions within safe reach.

- Have sturdy handrails in client bathrooms, rooms, and hallways.

- Place the hospital bed in the low position when a client is resting. Raise the bed to a comfortable height when the client is transferring out of bed.

- Keep the hospital bed brakes locked.

- Keep wheelchair wheels in a "locked" position when stationary.

- Keep no-slip, comfortable, and well-fitting footwear on the client.

- Use night lights or supplemental lighting.

- Keep floor surfaces clean and dry. Clean up all spills promptly.

- Keep client care areas uncluttered.

- Follow safe client handling practices.[26]

Interventions Based on Risk Factors

Clients at elevated risk for falling require multiple, individualized interventions, in addition to universal fall precautions. There are many interventions available to prevent falls and fall-related injuries based on the client's specific risk factors. See Table 5.6a for interventions categorized by risk factor.[27]

Table 5.6a Interventions Based on Fall Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | Interventions |

|---|---|

| Altered Mental Status | Clients with new altered mental status should be assessed for delirium and treated by a trained nurse or physician. See a tool for assessing delirium below. For cognitively impaired clients who are agitated or trying to wander, more intense supervision (e.g., sitter or checks every 15 minutes) may be needed. Some hospitals implement designated safety zones that include low beds, mats for each side of the bed, nightlight, gait belt, and a "STOP" sign to remind clients not to get up. |

| Impaired Gait or Mobility | Clients with impaired gait or mobility will need assistance with mobility during their hospital stay. All clients should have any needed assistive devices, such as canes or walkers, in good repair at the bedside and within safe reach. If clients bring their assistive devices from home, staff should make sure these devices are safe for use in the hospital environment. Even with assistive devices, clients often need staff assistance when transferring out of bed or walking. Use a gait belt when assisting clients to transfer or ambulate per agency policy. |

| Frequent Toileting Needs | Clients with frequent toileting needs should be taken to the toilet on a regular basis via a scheduled rounding protocol. Read more about scheduled rounding in the following subsection. |

| Visual Impairment | Clients with visual impairment should have clean corrective lenses easily within reach and applied when walking. |

| High-Risk Medications (medicines that could cause sedation, confusion, impaired balance, orthostatic blood pressure changes, or cause frequent urination) | Clients on high-risk medications should have their medications reviewed by a pharmacist with fall risk in mind and recommendations made to the prescribing provider for discontinuation, substitution, or dose adjustment when possible. If a pharmacist is not immediately available, the prescribing provider should carry out a medication review. See Table 5.6b for a tool to review medications for fall risk. Clients on medications that cause orthostatic hypotension should have their orthostatic blood pressure routinely checked and reported. The client and their caregivers should be educated about fall risk and steps to prevent falls when the client is taking these medications. |

| Frequent Falls | Clients with a history of frequent falls should have their risk for injury assessed, including checking for a history of osteoporosis and use of aspirin and anticoagulants. |

Scheduled Hourly Rounding

Scheduled hourly rounds are scheduled hourly visits to each client’s room to integrate fall prevention activities with client care. Scheduled hourly rounds have been found to greatly decrease the incidence of falls because the client's needs are proactively met, reducing the motivation for the client to get out of bed unassisted. See the box below for a list of activities to complete during hourly rounds. These activities can be completed by unlicensed assistive personnel, nurses, or nurse managers.[28]

Hourly Rounding Protocol[29]

- Assess client pain levels using a pain-assessment scale. (If staff other than a nurse is doing the rounding and the client is in pain, contact the nurse immediately so the client does not have to use the call light for pain medication.)

- Put pain medication that is ordered “as needed” on an RN’s task list and offer the dose when it is due.

- Offer toileting assistance.

- Ensure the client is using correct footwear (e.g., specific shoes/slippers, no-skid socks).

- Check that the bed is in the locked position.

- Place the hospital bed in a low position when the client is resting; ask if the client needs to be repositioned and is comfortable.

- Make sure the call light/call bell button is within the client’s reach and the client can demonstrate accurate use.

- Put the telephone within the client’s reach.

- Put the TV remote control and bed light switch within the client’s reach.

- Put the bedside table next to the bed or across the bed.

- Put the tissue box and water within the client’s reach.

- Put the garbage can next to the bed.

- Prior to leaving the room, ask, “Is there anything I can do for you before I leave?"

- Tell the client that a member of the nursing staff (use names on whiteboard) will be back in the room in an hour to round again.

Medications Causing Elevated Risk for Falls

Evaluate medication-related fall risk for clients on admission and at regular intervals thereafter. Add up the point value (risk level) in Table 5.6b for every medication the client is taking. If the client is taking more than one medication in a particular risk category, the score should be calculated by (risk level score) x (number of medications in that risk level category). For a client at risk, a pharmacist should review the client’s list of medications and determine if medications may be tapered, discontinued, or changed to a safer alternative.[30]

Table 5.6b Medications Causing High Risk for Falls[31]

| Point Value (Risk Level) | Medication Class | Fall Risks |

|---|---|---|

| 3 (High) | Antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines | Sedation, dizziness, postural disturbances, altered gait and balance, and impaired cognition |

| 2 (Medium) | Antihypertensives, cardiac drugs, antiarrhythmics, and antidepressants | Induced orthostasis, impaired cerebral perfusion, and poor health status |

| 1 (Low) | Diuretics | Increased ambulation and induced orthostasis |

| Score ≥ 6 | Elevated risk for falls; ask pharmacist or prescribing provider to evaluate medications for possible modification to reduce risk |

View tools used to assess delirium and confusion in the Delirium Evaluation Bundle shared by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.